Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

2010 G.petty - Teaching Today A Practical Guide 4th Ed p411-427

Загружено:

James FarnhamОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

2010 G.petty - Teaching Today A Practical Guide 4th Ed p411-427

Загружено:

James FarnhamАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

37

Part 4 Putting it all together

Aims and objectives

A large insurance firm in New York was having trouble with its 20-storey skyscraper.

The managing director wrote to engineering firms, telling them of the repeated

complaints he had received from his employees. They were complaining about

the length of time they had to wait for the lift, so he was asking for quotes for the

installation of a new lift shaft.

The managing director received a number of quotes for tens of millions of dollars,

along with one from an engineer who said he could solve the problem for $9,000.

This quote was rejected out of hand at first, but the director was intrigued. Finally,

he telephoned and asked, ‘How can you fit a lift shaft for $9,000?’ The engineer

pointed out that the real aim was not to fit a lift shaft, but to reduce employee

frustration. His plan was to create comfortable places for employees to wait for

the lift, with easy chairs, potted plants, mirrors, fish tanks, magazines and piped

music. This solution still works well to this day. Moral: think very carefully about

your aims before starting your plans.

Almost any purposeful human activity can be said to fall into the pattern shown in

the diagram above – everything from arranging your holidays or cooking fish pie

to setting up a business or going shopping.

Teaching falls into the same pattern. Teachers first decide what they hope to achieve

(aims and objectives), then plan the lesson, then teach the lesson – i.e. carry the

plan out. Then they need to evaluate the lesson, asking themselves whether they

did indeed achieve the aims set. Assessing what the students have learned helps

answer this question. This evaluation may lead to a change in the aims for the next

lesson, or for the next time this same lesson is taught, so the process is cyclic.

409

P04.indd 409 2/3/09 16:45:26

Putting it all together

What are aims and objectives?

‘Aims’ or ‘educational goals’ are clear and concise statements that describe what

the teacher hopes to achieve. These statements of intent are usually expressed in

a rather broad and generalised way – for example:

• To improve the students’ ability to communicate effectively in formal written

English.

• To develop an understanding and appreciation of the world’s major religions.

• To create opportunities for students to engage in creative self-expression.

• To develop a knowledge and understanding of scientific investigative

procedures.

Some people advocate expressing aims from the point of view of the teacher or the

course, rather than from the students’ point of view. For example:

• The aim of the course is to consider the basic principles of retailing.

• The training package will introduce the basic elements of computer program-

ming.

It is usually impossible to achieve aims absolutely. Students could work on achiev-

ing most of the above aims for a lifetime, and still have plenty to do! Aims are so

general and all-embracing that there can be as few as four or five for a full-time

one-year course.

Aims are like compass directions, indicating the general direction in which the

teacher wishes to travel. As such, they are vital; but they are not specific enough to

help the teacher pick learning activities, or assess whether learning has taken place.

There is no general agreement about how to decide aims and objectives, or precisely

how they should be written. But there is agreement that aims are vitally important.

Where do aims come from?

Aims may be provided by an examination syllabus, by a programme

of study, or by the awarding body for a qualification. Later we will see

that they may in some circumstances be provided by a ‘needs analysis’,

by ‘task analysis’ or by negotiation with the students on the course.

However, teachers decide most of their own aims, even if they are not

written down formally.

What are you are trying to achieve by your teaching? Do you take an

entirely functional view that education provides students with the means

to earn a living and to cope in our society? Or do your aims go beyond

this? Some aims will come from your own values (see Chapter 45).

Learning outcomes

Aims may point you in the right direction, but they don’t tell you how to get there,

or when you have arrived. So intentions must be described in a more detailed

way with what are variously called ‘specific objectives’, ‘behaviourist objectives’,

410

410 ‘competencies’ and/or ‘specific learning outcomes’. In this book, I shall call them

P04.indd 410 2/3/09 16:45:27

Aims and objectives

‘learning outcomes’. They are testable statements describing what you intend your

students to learn – for example:

• The student should be able to use inverted commas correctly.

• The student should be able to solder electronic components on to a circuit

board.

This is much better than teacher-centred aims such as ‘to describe how to punctu-

ate correctly’ or ‘to show students how to solder’. If you examine the latter care-

fully, you will see that these statements can be satisfactorily met whether or not the

student has learned anything! We must shift the focus from teaching to learning.

Doing so has a number of advantages. It makes clear what students have to practise,

and avoids a lesson dominated by teacher talk, where little real learning takes place.

It makes lesson planning easier by suggesting learning activities (e.g. corrected

practice of soldering or dialogue writing). Moreover, if you know precisely what

students should be able to do, it is much easier to assess whether or not they can

do it. This enables you to evaluate how successful your lessons have been.

The crucial point is that the outcomes precisely describe observable learner perfor-

mance, shifting the focus on to what the students will be able to do as a result of

their learning, and away from what the teacher will do. For example:

The student should be able to:

• State three advantages of the diesel engine over the petrol engine.

• List the main methods of pest management in Indonesia.

• Distinguish between fog, smog, mist and cloud.

Most people have difficulty in writing objectives at first, tending to think in terms of

what the teacher will do rather than what the student will learn. Are these specific

learning outcomes?

• To introduce the idea of percentages.

• The Peasants’ Revolt.

The answer is no – they aren’t. Could you change them so that they were? Have a

try before reading further.

Specific learning outcomes or specific objectives should:

• specify precisely and in concrete terms what the student should be able

to do

• be written in such a way that it is possible to determine whether or not the

objective has been achieved

• usually be short-term

• be drawn up by the teacher to suit the resources, the teacher and the

students

• optionally, define the circumstances under which the objective is to be demon-

strated and/or what constitutes an achievement, e.g. ‘Translate passage 6d

in less than five minutes, making fewer than four minor mistakes’.

Some like the mnemonic SMART, standing for specific, measurable, agreed,

realistic and timebound.

411

P04.indd 411 2/3/09 16:45:27

Putting it all together

Here are some legitimate objectives for the topics mentioned above. Notice that

they identify skills or abilities, and so suggest ‘use’, ‘check and correct’ and the

other elements of learning.

Students should be able to:

• express one number as a percentage of another

• calculate a given percentage of a given amount.

Students should be able to:

• state and explain the main events running up to the Peasants’ Revolt

• explain three economic consequences of the Peasants’ Revolt.

Ineffective teachers say they will ‘cover percentages’ or ‘talk about the Peasants’

Revolt’, or ‘do fractions’. But effective teachers always focus on what the student

should be able to do. Writing ‘specific learning outcomes’ or ‘specific objectives’

is an intellectually demanding task, and it requires a great deal of time and effort.

But outcomes are vital; they are the stepping stones which take the learners in the

direction of our aims.

Classification of objectives or outcomes

B. S. Bloom’s ‘Taxonomy of Educational Objectives’ attempts to classify all learning

into three domains, and, within each domain, into skills or abilities of different types

or difficulty. We also met it in Chapter 1. It is written from a learning objectives point

of view, and describes ‘how the learners are expected to be changed by the educative

process’. It was first developed in 1951 and has had an enormous influence.

The three domains and some of their subsections are described briefly below in a

simplified version. Typical verbs used to write objectives are given for each section

of the taxonomy.

412

P04.indd 412 2/3/09 16:45:27

Aims and objectives

The cognitive domain (intellectual skills and abilities)

Bloom arranged the categories which follow in order of difficulty, with the easiest

first. However, easy, high-order tasks are possible, indeed vital, as we saw in Chapter

1. Without higher-order objectives in your teaching, these skills will not be devel-

oped, and neither will fully functional knowledge or full comprehension.

Knowledge. To be able to:

state; recall; list; recognise; select; reproduce; draw …

e.g. to recall Newton’s Laws of Motion.

Comprehension. To be able to:

explain; describe reasons for; identify causes of; illustrate …

e.g. to give reasons for seat belts by referring to Newton’s Laws of Motion.

Application. To be able to:

use; apply; construct; solve; select …

e.g. to use Newton’s Laws of Motion to solve simple problems.

Analysis. To be able to:

break down; list component parts of; compare and contrast; differentiate between

…

Synthesis (this involves choosing, using and putting together diverse skills, abilities

and knowledge to accomplish a particular new task). To be able to:

summarise; generalise; argue; organise; design; explain the reason for …

Evaluation. To be able to:

judge; evaluate; give arguments for and against; criticise …

The affective domain

This domain concerns itself with attention, interest, awareness, aesthetic appre-

ciation, moral, aesthetic and other attitudes, opinions, feelings or values. For

example:

to listen to … to appreciate the importance of …

to have an awareness of … to respond with personal feelings …

to have an aesthetic appreciation of … to have a commitment towards …

to recognise the moral dilemmas involved in … to believe in your own ability

to …

The psychomotor domain

This includes motor skills or physical skills, including sense perception, hand-and-

eye coordination, etc. For example:

to plane; to draw; to throw; to weld …

413

P04.indd 413 2/3/09 16:45:27

Putting it all together

Note that ‘to know …’ or ‘to understand …’ are not acceptable beginnings for

specific objectives, which should describe abilities that are directly observable and

testable. What does it mean to say that a student ‘knows’, say, the story of Lazarus?

Does it mean that the student is able to recognise the story and name it? Or recall

it in outline? Or recall it in detail? Or describe its significance? The objective needs

to state what the student should be able to do in an easily testable form; it could

become, for example:

To recount in outline the story of Lazarus.

Unlike ‘To know the story of Lazarus’, this is clear, it is testable, and it suggests

what the student needs to practise.

Similarly, what does it mean to ‘understand’ osmosis? Does it mean to be able to

describe its significance? To explain how and why it takes place? To be able to use

the idea to explain novel occurrences of the phenomenon? Or some combination of

these abilities? Often what is required is for the student to be able to answer exam-

ination-style questions on the topic; if so, what abilities do such questions demand?

Examining textbook and examination questions in the topic you are teaching can

help you to see what students should be able to do with the material you are teaching.

To say that they should ‘know’ or ‘understand’ the material is too vague.

General objectives

Many teachers describe their intentions partly in a form which is somewhere

between an aim and a specific learning outcome. Such intentions are variously

described as short-term aims, general instructional objectives, or non-behaviourist

objectives. Examples might be:

• To introduce students to some aspects of modern telecommunications.

• To outline modern stock-control methods.

If you choose to describe your intentions in such a way, make sure that you include

in each statement both the content itself and what will be done with such content.

Make your statements clear and simple. For example:

• To develop an appreciation of Handel’s Messiah.

• To recognise the importance of safety checks on building sites.

These general objectives are then used to generate specific learning outcomes. For

example, the safety objective above could be broken down as follows:

General objective:

To recognise the importance of frequent safety inspections.

Specific learning outcomes:

To list the main checks made during a safety inspection.

To state the main dangers to health and safety on a building site.

To recognise and correct the improper use of a ladder.

An aim may encompass many general objectives, and, in turn, each general objec-

tive will generate a number of specific learning outcomes.

414

P04.indd 414 2/3/09 16:45:28

Вам также может понравиться

- Lesson Objectives PPT Group3-1Документ19 страницLesson Objectives PPT Group3-1Silva Noridha SitompulОценок пока нет

- Unit Two - Educational Goals and ObjectivesДокумент20 страницUnit Two - Educational Goals and Objectiveskhadar Abdi BuuxОценок пока нет

- 1129 Section 6 Monitoring and Evaluation - tcm143-661776Документ11 страниц1129 Section 6 Monitoring and Evaluation - tcm143-661776Eunita KorankyeОценок пока нет

- Developing Internship Learning GoalsДокумент5 страницDeveloping Internship Learning GoalsAbhinavTikuОценок пока нет

- Setting Goals Lesson PlanДокумент8 страницSetting Goals Lesson PlanАнастасія Маріанівна КосенкоОценок пока нет

- Stages of A Training CycleДокумент9 страницStages of A Training CycleriungumartinОценок пока нет

- SS301 - Learning OutcomeДокумент31 страницаSS301 - Learning OutcomeEVELYN GRACE TADEOОценок пока нет

- Chapter FourДокумент7 страницChapter FourIduhoze JeanpaulОценок пока нет

- Bus205 The Nature of ObjectivesДокумент24 страницыBus205 The Nature of ObjectivesKai BrightОценок пока нет

- Applied DidacticsДокумент61 страницаApplied DidacticsnankenkmОценок пока нет

- EDUC202 Unit 1Документ15 страницEDUC202 Unit 1markytagasaОценок пока нет

- A Detailed Lesson Plan-Developmental ReadingДокумент4 страницыA Detailed Lesson Plan-Developmental ReadingBlair RhienОценок пока нет

- What Is Constructive AlignmentДокумент8 страницWhat Is Constructive AlignmentRoboCopyОценок пока нет

- Writing Learning Objectives PDFДокумент9 страницWriting Learning Objectives PDFrinku100% (1)

- Assessment in the Critical Skills Classroom: The Critical Skills ClassroomОт EverandAssessment in the Critical Skills Classroom: The Critical Skills ClassroomОценок пока нет

- Writing Outstanding McqsДокумент6 страницWriting Outstanding McqsAurangzebОценок пока нет

- Six Common Mistakes in Writing Lesson PlansДокумент5 страницSix Common Mistakes in Writing Lesson PlansKristijanSaОценок пока нет

- Writing Aims and ObjectivesДокумент3 страницыWriting Aims and ObjectivesMohd Hanis 'Ady' IzdiharОценок пока нет

- TIG 4 Learning ObjectivesДокумент8 страницTIG 4 Learning ObjectivesShivraj ShettyОценок пока нет

- Noyd - Writing Good Learning GoalsДокумент8 страницNoyd - Writing Good Learning GoalsRob HuberОценок пока нет

- Unpacking Learning CompetenciesДокумент5 страницUnpacking Learning CompetenciesThis is a GarbageОценок пока нет

- Accelerated Learning Techniques: Unlimited Photographic Memory Mastery and Memory ImprovementОт EverandAccelerated Learning Techniques: Unlimited Photographic Memory Mastery and Memory ImprovementОценок пока нет

- Learning ObjectivesДокумент38 страницLearning ObjectivesBAWASKAR GANESH PUNDLIKОценок пока нет

- Bloom'S Revised TaxonomyДокумент29 страницBloom'S Revised Taxonomyapi-514282949Оценок пока нет

- A 10 minute intro to Business English Teacher DevelopmentОт EverandA 10 minute intro to Business English Teacher DevelopmentРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (2)

- Setting: Curriculum Goals and ObjectivesДокумент19 страницSetting: Curriculum Goals and ObjectivesFuad AzmiОценок пока нет

- 4 Teaching Approaches: 4.1 Active LearningДокумент2 страницы4 Teaching Approaches: 4.1 Active LearningJelenaAVОценок пока нет

- Activity 2 - Written Discourse - Learning OutcomeДокумент6 страницActivity 2 - Written Discourse - Learning OutcomeLyn Arcete100% (1)

- Explain The Importance o Evaluating Teachers' PerformanceДокумент6 страницExplain The Importance o Evaluating Teachers' PerformanceShitty headОценок пока нет

- Defining Intended Learning OutcomesДокумент14 страницDefining Intended Learning OutcomesTamer Farouk KhalifaОценок пока нет

- Lesson 7 MaterialДокумент12 страницLesson 7 MaterialgelaОценок пока нет

- Learning Intentions and Success CriteriaДокумент5 страницLearning Intentions and Success Criteria286221Оценок пока нет

- Prof. Ed. 9 MODULE 3Документ8 страницProf. Ed. 9 MODULE 3Sarah B. MaramagОценок пока нет

- Session 8A - Formulating Behavioral ObjectivesДокумент48 страницSession 8A - Formulating Behavioral Objectiveselizabeth.dingal001Оценок пока нет

- Outcomes-Based Education: Reporters: Abas, Kent Rayzard Aveguetero, Khetmelo Badaran, Mocha Alexa de Eyoy, Merlyn MaeДокумент20 страницOutcomes-Based Education: Reporters: Abas, Kent Rayzard Aveguetero, Khetmelo Badaran, Mocha Alexa de Eyoy, Merlyn MaeCAROLINE ORDO�AОценок пока нет

- Format of A Lesson PlanДокумент3 страницыFormat of A Lesson PlanNathalia Robles OrtizОценок пока нет

- 2 2creating Success Criteria PDFДокумент2 страницы2 2creating Success Criteria PDFmon pereОценок пока нет

- Curriculum Notes - Module 4Документ10 страницCurriculum Notes - Module 4Dayang DayangОценок пока нет

- 4.2 Developing Success Criteria: 4 Teaching ApproachesДокумент1 страница4.2 Developing Success Criteria: 4 Teaching ApproachesYuni IsmawatiОценок пока нет

- Pedagogical Grammar Dr. Lazgeen Mohammed Raouf Aims, Objectives and OutcomesДокумент22 страницыPedagogical Grammar Dr. Lazgeen Mohammed Raouf Aims, Objectives and OutcomesMohammed DoskiОценок пока нет

- Module 2Документ7 страницModule 2Cassie HowardОценок пока нет

- What Should Be Observe in Making and Use of Scoring RubricsДокумент23 страницыWhat Should Be Observe in Making and Use of Scoring RubricsCezLuzarraga100% (2)

- Intended Learning Outcomes (ILO)Документ17 страницIntended Learning Outcomes (ILO)Marco mancioОценок пока нет

- Planning, by Harry Dodds and Lorna Smith: Why Is A Lesson Plan Important?Документ3 страницыPlanning, by Harry Dodds and Lorna Smith: Why Is A Lesson Plan Important?Issa VandanaОценок пока нет

- Effective Lesson PlanningДокумент16 страницEffective Lesson PlanningMs.Muriel MorongОценок пока нет

- Group D - Career DevelopmentДокумент34 страницыGroup D - Career DevelopmentoeaОценок пока нет

- Test Bank For Keys To Nursing Success Revised Edition 3 e 3rd Edition 0137036841Документ38 страницTest Bank For Keys To Nursing Success Revised Edition 3 e 3rd Edition 0137036841gabsankhya7vc7100% (13)

- Instructional Planning (PDF - Io)Документ4 страницыInstructional Planning (PDF - Io)CliffordОценок пока нет

- Roadmap 2 Success 2017 R 1Документ11 страницRoadmap 2 Success 2017 R 1Ioana OrzeaОценок пока нет

- Six Common Mistakes in Writing Lesson PlansДокумент6 страницSix Common Mistakes in Writing Lesson Planswaqarali78692Оценок пока нет

- Educ 6Документ15 страницEduc 6Joyce crisosto100% (2)

- Module 23Документ9 страницModule 23Kel LumawanОценок пока нет

- Unit Three: The Curriculum Development ProcessДокумент32 страницыUnit Three: The Curriculum Development ProcessRicardo Sage2 HarrisОценок пока нет

- Instructional Module in PED 109module 4Документ31 страницаInstructional Module in PED 109module 4Hepshebah De Dios SantuyoОценок пока нет

- Project Management Skills for Coursework: A Practical Guide to Completing Bgcse Exam CourseworkОт EverandProject Management Skills for Coursework: A Practical Guide to Completing Bgcse Exam CourseworkОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan: Version - 002 Ed. From 01/01/2019 Page 1 of 2Документ15 страницLesson Plan: Version - 002 Ed. From 01/01/2019 Page 1 of 2James FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Save Water WorksheetДокумент4 страницыSave Water WorksheetCintiaОценок пока нет

- Int Actual Schedule 4 DaysДокумент84 страницыInt Actual Schedule 4 DaysJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Speaking: Al Zaeem Mohammed Bin Abdullah Al Attiyah Air AcademyДокумент3 страницыSpeaking: Al Zaeem Mohammed Bin Abdullah Al Attiyah Air AcademyJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Leave Request ApplicationДокумент1 страницаLeave Request ApplicationJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

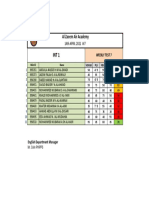

- Al Zaeem Air Academy: Weekly Test 7Документ1 страницаAl Zaeem Air Academy: Weekly Test 7James FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Exam Week Jobs - Sheet1Документ1 страницаExam Week Jobs - Sheet1James FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Wired UK - 01 2020 PDFДокумент151 страницаWired UK - 01 2020 PDFJames Farnham50% (2)

- Water and Desalination in QatarДокумент1 страницаWater and Desalination in QatarJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Map of The Book: Unit UnitДокумент1 страницаMap of The Book: Unit UnitJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Grand Theft Auto - San Andreas ManualДокумент17 страницGrand Theft Auto - San Andreas ManualSergio Daniel ViteОценок пока нет

- How To Teach Different Levels Like A ProДокумент57 страницHow To Teach Different Levels Like A ProNicolás100% (2)

- Water Is Very Important For LifeДокумент2 страницыWater Is Very Important For LifeJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Are Our Students Motivated?Документ3 страницыAre Our Students Motivated?James FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Aim: To Practice PTE Question Type REPEAT QUESTION Using Falling Intonation With Initial Adverbs and Lists. Aim: Cover Page 59Документ1 страницаAim: To Practice PTE Question Type REPEAT QUESTION Using Falling Intonation With Initial Adverbs and Lists. Aim: Cover Page 59James FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Wallace Chapters 2 and 3Документ17 страницWallace Chapters 2 and 3James FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Harmer, Jeremy - The Practice of English Language Teaching p364-378Документ3 страницыHarmer, Jeremy - The Practice of English Language Teaching p364-378James FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Phonetic Chart Landscape British English PDFДокумент1 страницаPhonetic Chart Landscape British English PDFJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- GMT20181106 205540 - Jamie KeddДокумент2 страницыGMT20181106 205540 - Jamie KeddJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- The Effectiveness of Cooperative Learning Strategy Through English Village For Teaching Speaking SkillДокумент7 страницThe Effectiveness of Cooperative Learning Strategy Through English Village For Teaching Speaking SkillJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Learning Coach 2Документ2 страницыLearning Coach 2James FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Interview With Steven McDonoughДокумент8 страницInterview With Steven McDonoughJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Big Questions in ELT - Scott ThornburyДокумент7 страницBig Questions in ELT - Scott ThornburyJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Globalization and Language Education: English Village in South KoreaДокумент27 страницGlobalization and Language Education: English Village in South KoreaJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- WNL Want To Lose Weight Eat Off A Crinkly Plate UppДокумент5 страницWNL Want To Lose Weight Eat Off A Crinkly Plate UppJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Opposition and AccommodationДокумент36 страницOpposition and AccommodationJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Classroom Performance Assessment RubricДокумент2 страницыClassroom Performance Assessment RubricJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Vacancy Information: Section AДокумент11 страницVacancy Information: Section AJames FarnhamОценок пока нет

- Aim: To Practice PTE Question Type REPEAT QUESTION Using Falling Intonation With Initial Adverbs and Lists. Aim: Cover Page 59Документ1 страницаAim: To Practice PTE Question Type REPEAT QUESTION Using Falling Intonation With Initial Adverbs and Lists. Aim: Cover Page 59James FarnhamОценок пока нет

- english for (1к)Документ7 страницenglish for (1к)Anonymous bCbsifxuОценок пока нет

- Syllabus African ArtДокумент5 страницSyllabus African ArtjuguerrОценок пока нет

- Mil Pointers 2ND QuarterДокумент6 страницMil Pointers 2ND QuarterStephanie Gail P. SimonОценок пока нет

- Public Speaking: Presented By: Chanchal.V.SДокумент15 страницPublic Speaking: Presented By: Chanchal.V.Ssimona nelson100% (1)

- Cartoon Analysis GuideДокумент11 страницCartoon Analysis GuideNakyung KimОценок пока нет

- 129Документ7 страниц129TuanyОценок пока нет

- No Borders!!! No Nations!!Документ2 страницыNo Borders!!! No Nations!!David Fotis CheungОценок пока нет

- 02 SejongFacultyProfiles 20131209Документ143 страницы02 SejongFacultyProfiles 20131209Luong Tam Thinh0% (2)

- Czech Republic Communication TableДокумент4 страницыCzech Republic Communication Tableapi-270353850Оценок пока нет

- Homonyms DLPДокумент5 страницHomonyms DLPGabrielle Ortega100% (1)

- Abra Elementary School: Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region 02 Schools Division of Santiago CityДокумент3 страницыAbra Elementary School: Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region 02 Schools Division of Santiago CityMarjorie Delrosario PilonОценок пока нет

- Gender & Human SexualityДокумент20 страницGender & Human Sexualitymaria luz0% (1)

- Sociology: Sciences or of Bodies of KnowledgeДокумент13 страницSociology: Sciences or of Bodies of KnowledgeElvia RajuОценок пока нет

- Hopper BrochureДокумент12 страницHopper BrochureWalter SanchezОценок пока нет

- Strategy Assignment: Sir Shafqat HameedДокумент9 страницStrategy Assignment: Sir Shafqat HameedMaria IftikharОценок пока нет

- Understanding Culture, Society and Politics Midterm ExamДокумент2 страницыUnderstanding Culture, Society and Politics Midterm Examrouen bosquillos100% (4)

- Voices of Early Modern JapanДокумент306 страницVoices of Early Modern JapanAnonymous 1MoCAsR3100% (5)

- Edid 6501 Assignment 3 - Learning Theories Instructional Design - Kara Lord 406003336Документ17 страницEdid 6501 Assignment 3 - Learning Theories Instructional Design - Kara Lord 406003336api-310042469Оценок пока нет

- History of Arts IntegrationДокумент6 страницHistory of Arts Integrationapi-275829732Оценок пока нет

- Pali GrammarДокумент2 страницыPali GrammarLong Shi100% (1)

- Grade 10 Mock PCUPДокумент3 страницыGrade 10 Mock PCUPNishka NananiОценок пока нет

- Difference Between Morals and Ethics: Value View Result Sales Price Comparable Properties Afford SameДокумент5 страницDifference Between Morals and Ethics: Value View Result Sales Price Comparable Properties Afford SameDina Grace MagnayeОценок пока нет

- HDF 219 SyllabusДокумент8 страницHDF 219 Syllabusapi-338660702Оценок пока нет

- Pomerantz & Bell (2011) Humor As Safe House in The FL ClassroomДокумент14 страницPomerantz & Bell (2011) Humor As Safe House in The FL ClassroomJoel RianОценок пока нет

- MusicДокумент213 страницMusicjorge etayo100% (1)

- 1995-WENDT A-Constructing International PoliticsДокумент12 страниц1995-WENDT A-Constructing International PoliticsBárbara NevesОценок пока нет

- The Symbolic Art of Charles Rennie MacKintoshДокумент7 страницThe Symbolic Art of Charles Rennie MacKintoshbde_gnasОценок пока нет

- Chapter 5&6 John MIlton and Restoration Drama and ProseДокумент9 страницChapter 5&6 John MIlton and Restoration Drama and ProseRangothri Sreenivasa SubramanyamОценок пока нет

- Intervention ArchitectureДокумент195 страницIntervention ArchitectureCostin Ciungulet100% (1)

- 889125Документ9 страниц889125Pencils of PromiseОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Business Issues SyllabusДокумент6 страницContemporary Business Issues Syllabusgeenius8515Оценок пока нет