Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Salinan Terjemahan Salinan Terjemahan Main KE 9 UUL PDF

Загружено:

Eko Nevriansyah0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

47 просмотров25 страницОригинальное название

Salinan terjemahan Salinan terjemahan main KE 9 UUL.pdf

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

47 просмотров25 страницSalinan Terjemahan Salinan Terjemahan Main KE 9 UUL PDF

Загружено:

Eko NevriansyahАвторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 25

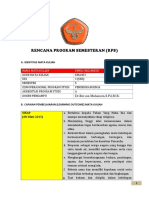

Bioteknologi dan transformasi inovasi vaksin: Kasus vaksin hepatitis B 1968e2000

Farah Huzair, Steve Sturdy *

Sains, Teknologi dan Studi Inovasi, Universitas Edinburgh, Old Surgeons 'Hall, High School Yards, Edinburgh EH1 1LZ,

Skotlandia, Inggris

articleinfo

Riwayat artikel: Diterima 31 Agustus 2016 Diterima dalam formulir revisi 4 Mei 2017 Tersedia secara online 13 Mei 2017

abstrak

Persetujuan, dari 1986, serangkaian vaksin hepatitis B rekombinan menjadi tonggak baik dalam pertumbuhan bioteknologi dan

dalam pengembangan vaksin sistem inovasi. Dalam tulisan ini, kami menunjukkan bagaimana perkembangan awal vaksin

hepatitis B dibentuk oleh konteks politik dan ekonomi yang baru komersialisasi komersial penelitian akademis, termasuk

perampasan dan manajemen kekayaan intelektual; kami menguraikan kepentingan dan motivasi kontingen yang menyebabkan

perusahaan bioteknologi baru dan mendirikan bisnis farmasi untuk berinvestasi dalam mengembangkan vaksin rekombinan

khusus terhadap hepatitis B; dan kami menunjukkan bagaimana faktor-faktor ini dan faktor-faktor lain digabungkan untuk

menjadikan vaksin-vaksin tersebut sebagai kesuksesan komersial yang tak terduga. Memperluas cakupan analisis kami untuk

tidak hanya mencakup Amerika Utara dan Eropa tetapi juga negara-negara berpenghasilan rendah dan menengah, kami

menunjukkan bagaimana perkembangan vaksin hepatitis B memfasilitasi munculnya sistem inovasi dua tingkat yang tersusun

oleh ketegangan antara tuntutan untuk keuntungan komersial di satu sisi, dan harapan manfaat kesehatan masyarakat bagi

negara-negara berpenghasilan rendah dan menengah di sisi lain.

© 2017 Para Penulis. Diterbitkan oleh Elsevier Ltd. Ini adalah artikel akses terbuka di bawah lisensi CC BY

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. Pendahuluan

Pada bulan Mei 1986, vaksin Recombivax HB, yang melindungi terhadap infeksi hepatitis B, disetujui untuk dipasarkan di

Jerman Barat; persetujuan oleh Administrasi Makanan dan Obat-obatan Amerika Serikat diikuti dua bulan kemudian.

Recombivax HB menandai tonggak dalam pengembangan bioteknologi medis. Diproduksi oleh Merck Sharp & Dohme, itu

adalah vaksin pertama yang diproduksi menggunakan teknologi DNA rekombinan, dan hanya produk rekombinan ketiga yang

dilisensikan untuk digunakan manusia (mengikuti insulin manusia pada tahun 1982 dan hormon pertumbuhan manusia pada

tahun 1985 dan hanya sebelum interferon alfa di Juni 1986). Dua vaksin hepatitis B rekombinan serupa segera diikuti: Engerix-B,

dipasarkan oleh SmithKline Biografi, disetujui di Belgia pada bulan Desember 1986 dan di AS pada September 1989; sementara

GenHevac-B oleh Pasteur Vaccins disetujui di Perancis pada bulan Mei 1989.

Para sejarawan kurang memperhatikan perkembangan vaksin hepatitis B e mungkin karena perusahaan-perusahaan

bioteknologi awal sendiri cenderung melihat mereka secara ilmiah dan komersial kurang menarik daripada yang lain- gelombang

obat rekombinan seperti insulin manusia dan interferon. SepertiNicholas

catatanRasmussen dalam Gene Jockeys, ini adalah molekul medis profil tinggi e insulin untuk posisi ikon dalam sejarah fisiologi

manusia dan obat-obatan, dan interferon karena secara luas dilihat sebagai obat potensial untuk kanker. Dengan demikian,

mereka adalah pihak yang kuat yang dapat mendemonstrasikan kemungkinan teknis dan komersial dari bioteknologi rekombinan

baru (Rasmussen, 2014). Sebaliknya, vaksin hepatitis B menargetkan penyakit yang pada waktu itu menarik sedikit perhatian di

Amerika Utara dan Eropa. Dengan demikian, vaksin peringkat rendah di antara prioritas perusahaan biotek muda.

Terlihat dalam perspektif sejarah yang lebih luas, bagaimanapun, vaksin hepatitis B rekombinan menjadi lebih penting

daripada bioteknologi awal dan mitra bisnis mereka pada awalnya. Stuart Blume berpendapat bahwa, antara tahun 1960-an dan

tahun 1990-an, “sistem inovasi vaksin” mengalami perubahan besar, dari sebuah perusahaan yang berorientasi publik, yang

berorientasi pada kesehatan publik pada tahun-tahun setelah Perang Dunia Kedua, menjadi satu didominasi oleh industri swasta,

termasuk sektor bioteknologi baru, pada akhir abad ini (Blume, 2008). Blume dan Ingrid Geesink melihat munculnya vaksin

hepatitis B rekombinan sebagai simbol pergeseran itu (Blume & Geesink, 2000, pp. 50e51, 55e57). Dalam tulisan ini, kami

menunjukkan bahwa itu tidak hanya simbolis; itu instrumental.

Menggambar pada campuran sumber-sumber sejarah termasuk literatur ilmiah yang diterbitkan, dokumen hukum dan kebijakan,

arsip dan lisan * Penulis yang sesuai.

Alamat e-mail: s.sturdy@ed.ac.uk (S. Sturdy).

wawancara sejarah, kami membangun narasi penjelasan dari

Studi dalam Sejarah dan Filsafat Ilmu Biologi dan Biomedis 64 (2017)11e21

daftar Isitersedia di ScienceDirect Studies dalam Sejarah dan Filosofi dariBiologis

dan Biomedical Science

jurnalhomepage: www.elsevier.com/locate / shpsc

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2017.05.004 1369-8486 / © 2017 Para Penulis. Diterbitkan oleh Elsevier Ltd. Ini adalah artikel

akses terbuka di bawah lisensi CC BY (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Dengan pengembangan dan komersialisasihepatitis B rekombinan

definisi, antigen adalah zat yang memicu

imunisasi dan vaksin plasma yang mendahuluinya. Kami menunjukkan

respon mune, dan Blumberg cepat menyadari bahwa

HBsAg mungkin bagaimana perkembangan awal vaksin dibentuk oleh po-

digunakan untuk memberi kekebalan terhadap

hepatitis B. Pada tahun 1968, dia dan konteks litikal dan ekonomi yang sangat disukai komersial-

Irving Millman mulai mengembangkan metode

pemurnian HBsAg untuk sation penelitian akademis, termasuk apropriasi dan

penggunaan sebagai vaksin. Pendekatan mereka

adalah novel. Vaksin sebelumnya memiliki manajemen kekayaan intelektual (IP); kami menjelaskan bahwa

telah diproduksi dari patogen yang mati atau tidak

aktif yang, kepentingan dan motivasi kontingen yang menyebabkan bioteknologi baru

ketika dimasukkan ke dalam tubuh, akan memancing

perusahaan kekebalan dan mendirikan usaha farmasi untuk berinvestasi sebagai

respons tanpa menyebabkan penyakit. Karena virus

hepatitis B mengembangkan vaksin rekombinan khusus terhadap hepatitis B;

telah terbukti mustahil untuk berkultivasi di luar

manusia dan kami menunjukkan bagaimana faktor-faktor ini dan faktor lain bertindak bersama untuk membentuk

tubuh, tidak mungkin untuk menghasilkan vaksin

dengan cara ini. Sebaliknya, vaksin-vaksin itu menjadi kesuksesan komersial yang tak terduga.

Blumberg dan Millman merancang metode untuk

memurnikan HBsAg dari Kami melanjutkan dengan berpendapat bahwa keberhasilan ini berfungsi untuk menanamkan vaksin

plasma pembawa hepatitis B, sementara

mengecualikan atau menghancurkan setiap perkembangan dalam sistem inovasi biofarmasi yang lebih besar yang

berpotensi menjadi bahan infeksius oleh proses rumit

dari sentri. - Yang semakin terlibat kolaborasi antara akademisi,baru

fugasidan perawatan kimia (Blumberg, 1977, hal. 20).

Ini adalah start up biotek dan mendirikan perusahaan farmasi,

upaya pertama untuk mengembangkan vaksin yang

melibatkan hanya subunit yang dimediasi oleh kontrol ketat dan lisensi IP. Akhirnya, memperluas

agen infeksi. Pada bulan Oktober 1969 Blumberg dan

Millman mengajukan ruang lingkup analisis kami untuk tidak hanya mencakup Amerika Utara dan

permohonan paten dengan Kantor Paten AS e yang

diberikan lebih dari dua Eropa tetapi juga negara-negara berpenghasilan rendah dan menengah, kami mencatat berapa

tahun kemudian e meliputi vaksin dan proses

produksinya, pengembangan vaksin hepatitis B akhirnya menghasilkan

(Blumberg & Millman, 1972). Proses inovasi dua

tingkat yang jelas, dengan tier pertama, di mana

Langkah-langkah pertama menuju pembuatan

vaksin melawan hepatitis B, fokus makalah ini, diarahkan untuk memproduksi vaksin karena

banyak sekali dipengaruhi oleh kebijakan. Pada akhir

1960-an, Penjualan Nasional AS menghasilkan keuntungan besar bagi pasar-pasar negara kaya, sementara sangat kuat

Health (NIH), yang mendanai berbagai institusi

Blumberg dan Millman yang berbeda yang dikembangkan untuk memproduksilebih murah

pekerjaan yang, sedang menghadapi pertumbuhan

politik. tekanan untuk menunjukkan bahwa vaksinnya digunakan di negara-negara miskin.

pengeluaran besar-besaran dana publik untuk penelitian

adalah penyampaian. Dalam menceritakan kisah ini, kami berkontribusi pada sejarahbioteknologi

manfaatpraktis (Berman, 2008, pp. 841e848; Yi, 2015,

pp. 141e nology serta sistem inovasi vaksin. Seperti sejumlah

146). Millman secara langsung mengaitkan

keputusannya dan Blumberg terhadap para analis telah menekankan, pertumbuhan bioteknologi yang terlibat

mengembangkan dan mematenkan vaksin mereka

terhadap tekanan dari NIH (Millman, rekonfigurasi hubungan universitas-industri yang signifikan, seperti

2013, h. 140). Minat yang lebih luas dalam

mengembangkan vaksin dibungkam, para ilmuwan universitas dan sumber daya semakin terlibat

. Hepatitis B bukan merupakan prioritas medis di

Amerika Utara atau menyediakan keahlian penelitian yang diperlukan untuk mewujudkan possi-

Eropa pada saat itu. Meskipun diakui sebagai pusat

kesehatan masyarakat (misalnya Kenney 1986, Orsenigo, 1989; Vallas & Kleinman, 2008;

masalah dalam apa yang kemudian disebut "Dunia

Ketiga", di Rasmussen yang lebih kaya, 2014). Kisah vaksin hepatitis B menyediakan sebuah

negara yang secara umum dianggap sebagai "penyakit

orang luar" studi kasus seks tentang bagaimana rekonfigurasi terjadi di sekitar satu

pekerja, pria gay dan pengguna narkoba suntikan e

menjamin sedikit di set produk tertentu, menyoroti interaksi lokal

cara perhatian atau sumber daya (Muraskin, 1988;

Stanton, 1994). Kontingensi dengan faktor sosio-teknis yang lebih luas yang mengarah pada-

Satusatunya dalam satu pengaturan apakah hepatitis B

memprovokasi alarm tertentu. Selama pelembagaan suatu bidang bioteknologi tertentu

di akhir 1960-an dan awal 1970-an, sejumlah wabah

hepatitis Basi. Tetapi fokus pada vaksin juga memberi tahu kita tentang kerusakan global yang

terjadi di unit dialisis ginjal, tidak hanya

mempengaruhi pasien tetapi juga mensions inovasi, menyoroti bagaimana, dalam hal ini setidaknya,

praktisi. Namun, wabah seperti itu terbukti dapat

dikelola pertumbuhan bioteknologi cenderung keistimewaan kepentingan

oleh peningkatan pengawasan dan praktek

pengendalian infeksi (Stanton, negara-negara kaya dan bisnis internasional atas publik

1995, hlm 118e126). kebutuhan kesehatan negara

berpenghasilan rendah dan menengah.

2. Hepatitis B dan vaksin plasma

Pada tahun 1965 Baruch Blumberg, variasi penelitian genetika dalam kerentanan dan kekebalan penyakit manusia di Institute

for Cancer Research di Fox Chase, Philadelphia, menerbitkan makalah yang mendetailkan identifikasi antigen yang sebelumnya

tidak diketahui dalam darah. diambil dari Australia Aborigin (Blumberg, Harvey, Alter, dan Visnich 1965). Blumberg dan

lain-lain melanjutkan untuk menunjukkan bahwa antigen ini dikaitkan dengan infeksi hepatitis B, dan kemudian bahwa itu adalah

bagian dari virus itu sendiri, protein kecil yang akhirnya dikenal sebagai antigen permukaan hepatitis B (HBsAg) (Blumberg,

1977, 2003, pp. 72e118). Ini adalah penelitian mutakhir ke dalam patogen yang sebelumnya tidak diketahui, yang Blumberg

dianugerahi Hadiah Nobel pada tahun 1976.

2

Sebagai perbandingan, praktisi medis dan pembuat kebijakan cenderung menganggap vaksinasi sebagai

solusi biaya rendah, permintaan rendah untuk masalah kepentingan marginal (Stanton, 1994, hal. 430e434).

Pada saat yang sama, produsen semakin enggan untuk berinvestasi dalam memproduksi vaksin baru. Sejak tahun 1950-an,

pengembangan vaksin sebagian besar disponsori oleh sektor publik atau pemberi dana amal yang dimotivasi oleh masalah

kesehatan masyarakat. Pekerjaan semacam itu biasanya dianggap sebagai barang publik, dan jarang tunduk pada perlindungan

paten. Akibatnya, perusahaan-perusahaan farmasi yang umumnya bertanggung jawab untuk membuat dan mendistribusikan

vaksin hanya menghasilkan keuntungan terbatas dari mereka. Pada akhir 1960-an, perusahaan juga menghadapi disinsentif

tambahan untuk berinvestasi dalam vaksin. Peningkatan kontrol regulasi yang ketat pada keamanan dan kemanjuran obat-obatan,

yang diperkenalkan oleh Badan Pengawasan Obat dan Makanan AS (FDA) mengikuti Amandemen Harris-Kefauver tahun 1962,

telah menambah secara signifikan biaya untuk membawa produk baru ke pasar; sementara perusahaan juga semakin sadar akan

risiko

1

Hadiah diberikan secara bersama-sama kepada Blumberg dan Carleton Gajdusek “atas penemuan mereka mengenai

mekanisme baru untuk asal dan penyebaran penyakit menular”. Gajdusek dimasukkan untuk penelitiannya ke penyakit kuru

prion. “Penghargaan Nobel dalam Fisiologi atau Kedokteran 1976”, Nobelprize.org, Nobel Media AB 2014,

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1976/, diakses 7 Desember 2015.

1

Hal ini juga menyadarkan Blumberg sebagai nyata berlaku.

2

Dua bulan sebelum mengajukan paten vaksin mereka, Blumberg dan Millman telah mengajukan permohonan paten AS untuk

tes untuk hepatitis B (Coller, Millman, & Blumberg, 1975). Tes serologi ini dan lainnya untuk HBsAg terbukti menjadi alat

pengendalian infeksi yang efektif dalam pengaturan perawatan kesehatan, terutama di negara-negara dengan jaringan kesehatan

masyarakat yang kuat (Blumberg, 2003, hlm. 119e133; Stanton, 1995, hlm 126e137; Gerlich, 2013).

F. Huzair, S. Kokoh / Studi dalam Sejarah dan Filsafat Ilmu Biologi dan Biomedis 64 (2017) 11e21 12

litigasi terkait dengan vaksin yang terkontaminasi. Pada akhir 1960-an, banyak perusahaan farmasi utama telah mengundurkan

diri dari pengembangan vaksin (Kongres AS, Office of Technology Assessment 1979; Peretz, 1983; Blume, 2008, hlm.

258e260). Akibatnya, ketika Blumberg dan Millman mulai mencari perusahaan untuk mengembangkan vaksin mereka dan

membawanya ke pasar, mereka mendapati diri mereka dalam posisi tawar yang lemah. Mereka lebih lanjut terhambat oleh

kendala yang NIH ditempatkan pada pembuangan IP yang timbul dari penelitian yang didanai.

Kebijakan IP NIH diinformasikan oleh harapan bahwa produk penelitian yang didanai publik harus dikembangkan dengan

cara yang terbaik melayani kepentingan publik. NIH menarik dua implikasi utama dari ini. Pertama, daripada memungkinkan

peneliti atau lembaga untuk mempertahankan hak atas paten yang timbul dari penelitian yang didanainya, paten tersebut

umumnya harus diberikan kepada NIH sebagai penjaga kepentingan publik. Dan kedua, ketika datang untuk melisensikan

paten-paten itu, kapan pun mereka mungkin harus dilisensikan hanya secara non-eksklusif, karena kontrol monopoli dari produk

yang berpotensi menyelamatkan jiwa akan memberdayakan para produsen untuk mengeksploitasi pasien yang membutuhkan

dengan membebankan harga yang terlalu tinggi (Berman, 2008). , hal 843; Eisenberg, 1996, hlm 1671e1677; Metlay, 2006, hlm

568e 581). Kondisi terakhir ini, khususnya, dibenci oleh industri farmasi, yang telah merespon dengan apa yang dipatenkan oleh

pengacara paten NIH sebagai "boikot virtual" dari paten yang dipegang NIH (Kongres AS, 1976, hlm. 723), dengan alasan bahwa

tanpa insentif lisensi eksklusif, tidak ada gunanya menginvestasikan dana yang diperlukan untuk membawa produk ke pasar.

3

Pada akhir 1960-an, NIH menghadapi tekanan politik yang meningkat untuk melonggarkan kebijakan IP-nya. Pada tahun

1968, lembaga ini memperkenalkan sistem perjanjian paten institusional (IPAs) dengan universitas yang kebijakan patennya

disetujui NIH. Universitas-universitas yang diizinkan ini tidak hanya memegang hak paten atas penelitian yang didanai NIH,

tetapi juga untuk mengeluarkan lisensi eksklusif di mana ini diperlukan untuk mengamankan komersialisasi meskipun NIH pada

umumnya mempertahankan hak untuk memveto lisensi tersebut jika berpikir bahwa kontrol monopoli atas penemuan tertentu

bertentangan untuk kepentingan umum (Eisenberg, 1996, hal. 1682e1684; Mowery, Nelson, Sampat, & Ziedonis, 2004, hlm

87e88; Yi, 2015, hlm 145e146, 157). The Institute for Cancer Research bukanlah salah satu institusi yang akan diberikan IPA,

namun, dan Blumberg dan Millman harus bernegosiasi langsung dengan NIH mengenai hak atas vaksin hepatitis B. NIH

akhirnya memberi mereka hak asing tetapi tetap memiliki hak domestik, yang NIH bersikeras hanya boleh dilisensikan secara

non-eksklusif (Millman, 2013, pp. 141e142).

4

Akibatnya, ketika pada tahun 1971 mereka memulai negosiasi dengan Merck e salah satu dari beberapa perusahaan farmasi

yang berbasis di AS yang tetap aktif dalam pengembangan vaksin, yang sudah mempertimbangkan hepatitis B sebagai target

yang mungkin e Blumberg dan Millman tidak dapat menawarkan lisensi untuk pasar AS. Tidak mengherankan, mengingat sikap

industri farmasi terhadap lisensi non-eksklusif, Merck menolaknya. Negosiasi dengan Merck tidak akan dibuka kembali hingga

awal 1975, pada saat itu Institut Penelitian Kanker telah memperoleh paten asing di sejumlah negara Eropa dan Asia dan sedang

berdiskusi dengan Glaxo di Inggris dan Institut Mérieux di Perancis mengenai mengawasi produksi. Pada bulan Agustus tahun

itu, Merck akhirnya menyetujui kesepakatan yang memberi mereka semua hak asing untuk vaksin serta non-

F. Huzair, S. Kokoh / Studi dalam Sejarah dan Filsafat Ilmu Biologi dan Biomedis 64 (2017) 11e21 13

eksklusif hak di Amerika Serikat (Galambos, 1995, pp. 188e190; Millman, 2013, pp. 141e144; Muraskin, 1995, hal 7).

Setelah terlibat, bagaimanapun, Merck bergerak cepat untuk mengkomersilkan vaksin. Pekerjaan itu dikelola oleh Maurice

Hilleman, yang secara luas dianggap sebagai salah satu ahli vaksinologi industri yang paling berhasil di dunia. Karir Hilleman

dalam pengembangan vaksin kembali ke tahun 1944 ketika ia bergabung dengan laboratorium virus ER Squibb & Sons sebagai

peneliti postdoctoral. Dia bergabung dengan Merck pada akhir tahun 1957 sebagai direktur departemen baru penelitian virus dan

biologi sel, dan pada tahun 1975 telah mengamankan posisi perusahaan sebagai pemimpin internasional dalam pengembangan

dan pembuatan vaksin (Offit, 2007). Hilleman telah selama beberapa waktu mengejar penyelidikan sendiri ke dalam

kemungkinan vaksin hepatitis B (Hilleman et al., 1975), dan dengan cepat memperoleh beberapa paten tambahan untuk

perbaikan pada metode Blumberg dan Millman untuk memurnikan HBsAg (misalnya Bertland, Tytell, Lampson , & Buynak,

1977; McAleer & Wasmuth, 1977), dengan demikian mengkonsolidasikan kendali Merck atas produk akhir. Uji klinis skala

penuh dimulai pada tahun 1978, dan vaksin telah disetujui di AS pada tahun 1981 dan diluncurkan dengan nama dagang

Heptavax-B pada tahun 1982 (Galambos, 1995, pp. 190e194).

Harga vaksin baru datang sebagai kejutan bagi juru kampanye kesehatan masyarakat. Kebanyakan vaksin dijual dengan harga

di bawah $ 2 per imunisasi, harga yang dianggap terjangkau oleh Organisasi Kesehatan Dunia untuk negara-negara

berpenghasilan rendah dan menengah (LMICs). Sebaliknya, Heptavax-B dipasarkan di AS sekitar $ 90 hingga $ 100 untuk

program imunisasi tiga dosis, menjadikannya vaksin paling mahal yang diproduksi hingga saat itu, dan menempatkannya jauh di

luar jangkauan sebagian besar dari mereka yang paling berisiko dari hepatitis B (Galambos, 1995, hal. 194; Muraskin, 1995, hal.

21). Hilleman membela harga dengan alasan bahwa vaksin itu tidak dapat diproduksi kurang. “Secara teknologi, pengembangan

vaksin adalah tantangan yang paling sulit yang pernah kami hadapi,” dia mengamati, sementara proses pembuatannya sendiri

membutuhkan waktu lima puluh enam minggu untuk setiap kelompok dari pengumpulan plasma pembawa hingga pelepasan

produk yang dimurnikan dan teruji keamanannya ( Galambos, 1995, hal 193). Tetapi kebijakan harga Merck juga konsisten

dengan pendekatan yang ditargetkan untuk pemasaran, yang ditujukan untuk konsumen yang melakukan dengan baik di

negara-negara kaya e khususnya pekerja perawatan kesehatan dan orang lain yang berisiko terkena paparan pekerjaan terhadap

darah yang terinfeksi, tetapi juga laki-laki gay yang mereka antisipasi dapat membayar vaksin baik dari kantong mereka sendiri

atau melalui asuransi mereka (Muraskin, 1988, pp. 287e 288; Mamo & Epstein, 2014, p. 159; Stanton, 1994, hlm 435e439).

Akibatnya, upaya Merck untuk mengamankan dan mengendalikan kekayaan intelektual, dan keputusannya untuk menargetkan

konsumen kaya daripada LMIC, menandai pergeseran jauh dari harapan bahwa tujuan kesehatan masyarakat harus menjadi

prioritas di atas kepentingan komersial dalam inovasi vaksin, dan menuju perhatian dengan laba yang lebih sesuai dengan jenis

produk farmasi lainnya.

Dalam acara tersebut, pengambilan Heptavax-B rendah bahkan di antara kelompok-kelompok sasaran ini. Banyak yang

khawatir bahwa produk turunan plasma menimbulkan risiko infeksi silang dengan patogen lain yang ketakutan, yang meskipun

tidak didukung oleh bukti, memperoleh arti penting dengan munculnya HIV / AIDS dan skandal seputar infeksi hemofilia Prancis

oleh produk darah yang terkontaminasi ( Muraskin, 1988, hal. 285; Conis, 2011, hlm 159e160; Stanton, 1994, hlm 439e440).

Perusahaan asuransi juga tidak mendapat manfaat dari vaksinasi hepatitis B, dan menolak membayar Heptavax-B (Galambos,

1995, pp. 195e196). Upaya Merck untuk menciptakan vaksin berbiaya tinggi telah kandas, mengonfirmasi pandangan industri

tentang ketidakmampuan sektor ini.

3. Langkah pertama menuju vaksin hepatitis B rekombinan, 1977e1979

Pada saat vaksin plasma Merck disetujui untuk pemasaran pada tahun 1981, tiga tim ilmuwan yang berbeda berlokasi di

3

Perlawanan industri didorong terutama oleh keputusan NIH pada tahun 1962 untuk mengakhiri pengaturan. dimana produk

penyaringan perusahaan yang dikembangkan di bawah Program Kimia NIH, kadang-kadang diizinkan untuk memegang paten

atau lisensi eksklusif pada bahan kimia yang ingin mereka kembangkan secara komersial.

4

Kami tidak dapat menentukan alasan NIH untuk menahan hak domestik. Namun, mungkin karena NIH menganggap vaksin

sebagai tindakan kesehatan masyarakat, yang karenanya harus tetap berada di tangan publik, dan tidak boleh dikenai monopoli

pribadi.

Edinburgh, San Francisco dan Paris masing-masing baik dalam mengembangkan vaksin alternatif hepatitis B menggunakan

teknologi DNA yang dominan. Pekerjaan mereka memperkenalkan teknologi produksi baru ke dalam sistem inovasi vaksin.

Tetapi lebih dari itu, ia juga mengasimilasi vaksin ke model bisnis bioteknologi baru yang mulai membangun dirinya dalam

ekonomi yang lebih luas dari inovasi farmasi. Model bisnis itu telah dimungkinkan oleh pergeseran ekspektasi yang sama

mengenai komersialisasi penelitian yang didanai publik sebagaimana telah mendorong Blumberg dan Millman mematenkan

vaksin plasma mereka. Secara khusus, itu adalah produk dari perubahan sikap terhadap paten yang telah mendorong liberalisasi

kebijakan IP NIH dari akhir 1960-an, dan itu memuncak dalam bagian dari Undang-Undang Bayh-Dole tahun 1980 (Kevles,

1994; Berman, 2008; Yi, 2015, hlm. 138e172).

Antara 1972 dan 1974, Herbert Boyer, seorang ahli biologi molekuler yang berbasis di University of California di San

Francisco (UCSF), dan rekan Stanford Stanley Cohen telah mengembangkan teknik baru yang kuat untuk memproduksi protein

menggunakan mikroorganisme rekombinan. Mengambil keuntungan dari kebijakan IP baru dan lebih liberal dari NIH, Stanford

dan University of California segera mengajukan permohonan paten. Aplikasi ini dengan cepat menjadi perdebatan yang lebih

luas tentang kepatutan mengklaim hak kepemilikan dalam organisme hidup, dan paten DNA rekombinan pertama tidak akan

diberikan sampai tahun 1980. Meskipun demikian, keputusan universitas untuk mencari hak paten yang terkait dengan Boyer,

antara lain, untuk kemungkinan komersial teknologi baru, dan peran yang dapat dimainkan oleh IP dalam mengeksploitasi

peluang-peluang itu. Pada tahun 1976, Boyer dan kapitalis ventura, Robert A. Swanson mendirikan perusahaan start-up

bioteknologi Genentech (Berman, 2008; Hughes, 2001a, 2011). Model bisnis mereka melibatkan mendanai para peneliti berbasis

universitas untuk mengembangkan dan mematenkan metode-metode baru yang menghasilkan biofarmasi. Dalam jangka panjang,

mereka berharap untuk membangun perusahaan ke titik di mana ia akan mampu memproduksi produk akhir itu sendiri; tetapi

dalam waktu yang berarti, Boyer dan Swanson berencana untuk melisensikan paten mereka untuk pengembangan oleh

perusahaan-perusahaan farmasi yang lebih besar. Akibatnya, Gen- entech mengubah penelitian biomedis yang berorientasi paten

dan akumulasi IP bioteknologi menjadi proposisi nilai komersial dalam dirinya sendiri (Doganova & Muniesa, 2015). Model

bisnis itu akan ditiru oleh sejumlah perusahaan start-up bioteknologi yang didirikan di Genentech. Ini juga akan

menginformasikan pengembangan vaksin hepatitis B rekombinan pertama.

3.1. Biogen

Dibuat pada tahun 1978, Biogen dimodelkan langsung pada pendekatan Genentech untuk mematenkan penelitian DNA

rekombinan berbasis universitas. Di bawah kepemimpinan kapitalis ventura Ray Schaefer dan Daniel Adams serta ahli biologi

molekuler dari Harvard, Walter Gilbert, Biogen melihat melampaui AS untuk merekrut biolog evolusioner Eropa ke dewan

ilmiahnya. Pada serangkaian pertemuan di Jenewa dan Paris pada awal 1978, para ilmuwan Biogen mengidentifikasi sejumlah

garis penelitian DNA rekombinan yang mereka pikir akan mengarah pada produk yang dapat dipatenkan. Di antara mereka

adalah proposal oleh Peter Hans Hofschneider dari Institut Max Planck untuk Biokimia di Martinsried dekat Munich, dan

Kenneth Murray dari Departemen Biologi Molekuler di Universitas Edinburgh, untuk mengembangkan vaksin rekombinan

melawan hepatitis B (Hofschneider & Murray, 2001). ; Weissmann, 2001).

Para pendukung teknologi DNA rekombinan baru berasal dari vaksin awal tahun 1970-an di antara produk-produk yang

mungkin diproduksi menggunakan metode rekombinan. Tetapi Hofschneider dan Murray juga memiliki alasan pribadi untuk

mengejar vaksin hepatitis B. Hofschneider untuk beberapa waktu telah tertarik pada peran virus

F. Huzair, S. Kokoh / Studi dalam Sejarah dan Filsafat Ilmu Biologi dan Biomedis 64 (2017) 11e21 14

sebagai kemungkinan penyebab kanker hati (Hofschneider & Murray, 2001; Neubert & Werner, 2004, hlm. 43). Murray,

sementara itu, memiliki pengalaman langsung dari penyakit itu sendiri. Pada tahun 1969, dua tahun setelah ia tiba di Edinburgh,

terjangkit wabah hepatitis B yang sangat parah telah terjadi di unit dialisis di Royal Infirmary (Stanton, 1995, hlm. 125). Pada

saat wabah itu terkandung pada tahun 1971, empat anggota staf dan tujuh pasien telah meninggal. Meskipun departemen Murbas

tidak terlibat dalam wabah itu, ia akan tetap menyadari dampaknya pada komunitas medis dan ilmiah setempat.

5

Penelitian awal Hofschneider dan Murray terhadap vaksin berjalan dengan cepat, dengan pendanaan yang murah hati

(menurut standar akademik) dari Biogen untuk fasilitas dan staf (Hofschneider & Murray, 2001, hlm. 46e47). Awalnya,

Hofschneider telah mengatur untuk berkolaborasi dengan sekelompok peneliti klinis di Munich, yang akan memasok serum dari

pasien yang terinfeksi hepatitis yang menjadi sumber virus. Ketika kolaborasi itu tiba-tiba runtuh, Murray berpaling kepada

rekan-rekan di departemen bakteriologi Universitas Edinburgh, yang sejak pecahnya 1969 telah menjadi pusat utama penelitian

hepatitis B di Inggris (Hofschneider & Murray, 2001, hlm. 45). Semakin, Murray sekarang mengambil alih tugas vaksin. Dengan

menggunakan teknik-teknik biologi molekuler mutakhir, dia dan timnya tidak hanya mengkloning dan mengekspresikan fragmen

DNA hepatitis B dalam E. coli, tetapi juga dengan susah payah menyusun bagian besar dari DNA virus. Pada bulan Februari

1979 mereka menyerahkan sebuah makalah kepada Nature mengumumkan bahwa mereka telah mencapai ekspresi bagian-bagian

kunci dari kedua HBsAg dan antigen kedua, yang disebut antigen inti, dalam E. coli (Burrell, Mackay, Greenaway, Hofschneider,

& Murray, 1979). ). Enam bulan kemudian mereka menyerahkan kertas kedua yang mendokumentasikan urutan nukleotida 87%

genom virus, termasuk sekuens DNA yang mereka yakini sebagai kode untuk gen inti dan permukaan (Pasek et al., 1979).

Sementara itu, pada Desember 1978 Murray telah mengajukan permohonan paten awal dengan Kantor Paten Inggris; dan segera

setelah kertas Nature kedua muncul pada bulan Desember 1979, Biogen mengajukan permohonan paten penuh dengan Kantor

Paten Eropa, mengklaim hak yang luas atas “molekul DNA rekombinan dan host yang ditransformasikan dengan mereka yang

menghasilkan polipeptida yang menampilkan antigenicity HBV dan gen yang mengkodekan dan metode dari membuat dan

menggunakan molekul-molekul ini, inang, gen dan polipeptida ”(Murray & Schaller, 1987). Akhirnya diberikan pada tahun 1987,

paten memberikan hak kepemilikan Biogen atas urutan DNA virus yang dikodekan untuk antigen permukaan dan inti, serta atas

pembuatan antigen tersebut dengan metode rekombinan.

3.2. Merck dan UCSF

Sementara itu, proyek kedua untuk mengembangkan vaksin hepatitis B rekombinan sedang berlangsung di pantai barat

Amerika Serikat. Seperti proyek Biogen, ini dilakukan di lingkungan akademik dengan pendanaan dari perusahaan komersial.

Namun, dalam kasus ini, perusahaan bukanlah perusahaan bioteknologi seperti Genentech, tetapi raksasa farmasi Merck.

Kekuatan pendorong dalam Merck adalah dokter dan ahli biokimia P. Roy Vagelos, yang pada tahun 1976 telah direkrut dari pos

akademik untuk memimpin Laboratorium Penelitian Merck Sharpe & Dohme. Vagelos ingin memastikan bahwa perusahaan

tetap di garis depan ilmu pengetahuan dan teknologi farmasi, dan khususnya untuk mengeksplorasi kemungkinan komersial dari

teknik DNA rekombinan baru. Dengan Hilleman bekerja pada vaksin plasma terhadap hepatitis B sudah di bawah

5

Wawancara dengan Sandra Bruce dan John Pugh, 2015; catatan kuliah "Hepatitis B e Melihat Inti Masalah": keduanya dalam

makalah Kenneth Murray (Coll-1527), Koleksi Khusus Perpustakaan Universitas Edinburgh.

dalam perusahaan, dan keahlian internal yang signifikan dalam menangani virus dan molekul penyusunnya, Vagelos

mengidentifikasi antigen permukaan hepatitis sebagai molekul target yang mudah digunakan untuk menyelidiki teknologi

produksi baru (Galambos, 1995, hal 197e199).

Kadang-kadang di musim gugur 1977 Vagelos melakukan percakapan dengan William Rutter ea ahli biologi molekuler dan

ketua departemen biokimia di UCSF tempat Herbert Boyer bekerja. Seperti Boyer, Rutter tertarik untuk mengeksploitasi potensi

komersial dari teknologi rekombinan baru. Dia keberatan tentang pendekatan Boyer terhadap komersialisasi. Sebagai ketua

departemen, Rutter mengabdikan dirinya untuk membangun program penelitian multikisipliner yang khas dan kolaboratif ke

dalam genetika molekuler (Jong, 2006).

Sementara ia mendukung inisiatif Boyer untuk mendapatkan pendanaan pribadi untuk penelitian DNA rekombinan, ia

khawatir bahwa Genentech tidak cukup menghargai UCSF untuk manfaat yang diperolehnya dari memiliki akses ke fasilitas

universitas dan program kerja yang lebih luas sedang berlangsung di sana. Akibatnya, Rutter menolak sebuah inviasi untuk

bergabung dengan Genentech, dan malah mencoba membujuk Universitas untuk membentuk perusahaan transfer teknologinya

sendiri untuk memastikan bahwa keuntungan komersialisasi dibajak kembali ke lembaga itu sendiri (Hughes, 2011, pp. 80e82;

Rutter, 1998, hlm 103e 106, 175e176). Pandangan Rutter tentang komersialisasi memiliki lebih banyak kesamaan dengan model

sebelumnya dari organisasi nirlaba yang berbasis universitas, seperti The Research Corporation dan Wisconsin Alumni Research

Foundation, yang didirikan pada paruh pertama abad kedua puluh untuk mengawasi komersialisasi. penelitian yang didanai

publik dengan cara yang disukai kepentingan ilmu pengetahuan universitas atas para peneliti individu (Apple, 1989; Mowery &

Sampat, 2001).

In the absence of such an organisation at UCSF, in 1977 Rutter accepted funding from pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly to

un- dertake research on recombinant insulin and growth hormone, in return for exclusive rights to any patents that might be

generated (Rasmussen, 2014, pp. 62e63, 80, 83; Rutter, 1998, pp. 188e198). At the same time, aware of public concern about the

possible risks associated with the new technology, Rutter had become “quite interested in developing a vaccine as a

demonstration of benefit over risk” (Rutter, 1998, p. 159). His meeting with Vagelos in the autumn of 1977 revealed their

common interest in hepatitis B, and led to an agreement between UCSF and Merck to develop a re- combinant vaccine (Rutter,

1998, pp. 159e160, 188). As well as funding, Merck provided Rutter with hepatitis B DNA from Hille- man's laboratory, which

Rutter passed to his colleague Pablo Valenzuela. By early 1979 Valenzuela had not only succeeded in cloning and expressing

HBsAg in E. coli, but had also sequenced the section of the viral genome that coded for the antigen. The paper announcing these

results appeared in Nature a week after Murray submitted his second paper to that journal (Valenzuela et al., 1979).

3.3. The Institut Pasteur

The third line of research into a recombinant hepatitis B vaccine took shape in the Institut Pasteur in France. The Institut

differed, in organisation and orientation, both from the model of private-sector biotechnology represented by Biogen, and from

the privately funded but academically based model of research and development represented by Rutter's programme at UCSF. A

non-profit foundation, from its establishment in 1887 the Institut had combined commercial production of vaccines with high-

quality microbiological and immunological research, often sub- sidised by substantial government funding (Liebenau & Robson,

F. Huzair, S. Sturdy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 64 (2017) 11e21 15

1991). Work on a vaccine against hepatitis B fitted squarely into this programme.

Like Merck, the Institut Pasteur had a prior interest in devel- oping a plasma vaccine against hepatitis B. From 1975,

researchers at the Institut had been working with scientists and clinicians at the Faculty of Medicine in Tours to develop their

own method of pur- ifying HBsAg from the blood of hepatitis B carriers, using frac- tionation rather than the system of

centrifugation and chemical treatment patented by Blumberg and Millman. In July 1980 the French researchers filed a US patent

application for their new method (Maupas & Goudeau, 1980). By that time, clinical trials were under way, and the vaccine was

licensed in France in 1981 under the proprietary name Hevac-B, manufactured and distrib- uted by the Institut's own in-house

company, Vaccins Pasteur (Chiron, Coursaget, & Yvonnet, 1998; Maugh, 1980; Maupas, Coursaget, Goudeau, Drucker, &

Bagros, 1976, 1978).

As at Merck, researchers at the Institut Pasteur were conscious of the need to keep abreast of the latest in research and pro-

duction technology. A key figure in this regard was Pierre Tiollais, a molecular biologist based at the Institut. Like Vagelos at

Merck, Tiollais saw access to an in-house source of hepatitis B virus, and expertise in working with it, as invaluable resources to

explore the productive possibilities of the new recombinant DNA tech- nology. By mid-1979 he and his team had succeeded not

only in cloning hepatitis B DNA in E. coli but also in sequencing the entire viral genome, as well as identifying those parts of the

sequence that coded specifically for the surface antigen. The re- sults were published in Nature just two months after Rutter and

Valenzuela's paper appeared there (Galibert, Mandart, Fitoussi, Tiollais, & Charnay, 1979; also Charnay, Pourcel, Louise,

Fritsch, & Tiollais, 1979a, 1979b).

4. Bringing the recombinant hepatitis B vaccines to market

Nicolas Rasmussen has argued that, for the biologists who formed the first generation of biotechnology companies, the op-

portunity to pursue interesting scientific research was as important as the as-yet-unproven possibility of a commercial pay-off

(Rasmussen, 2014). This was clearly true of the early research into sequencing, cloning and expressing the hepatitis B surface

antigen, which represented a substantial scientific achievement in its own right, resulting in four publications in Nature in the

course of 1979 alone. But achieving expression of the surface antigen under lab- oratory conditions was one thing; achieving

commercial produc- tion of an effective vaccine was another. Bringing the recombinant hepatitis B vaccines to market would

require considerably more research and development, involving a good deal of trial and error, as well as skills in clinical research

and marketing which went well beyond those of academic molecular biologists. Consequently, the subsequent development of

the three recombinant hepatitis B vaccines depended heavily on the relationships the three groups of scientists were able to

establish with commercial pharmaceutical manufacturers.

4.1. Merck and Chiron

The first major problem to confront all three teams was that the surface antigen produced by recombinant E. coli cultures did

not stimulate a big enough immune response in experimental animals. Rutter and his team at UCSF were the first to identify a

viable so- lution, though it took almost two years. Suspecting that recombi- nant bacteria produced the antigen in a different

physical conformation from infected human cells, Rutter and his colleagues explored an alternative production method using a

strain of human

4.2. liver cancer cells that had been found to possess multiple copies of

Biogen, Wellcome and SmithKline the hepatitis B

genome. The UCSF scientists were able to culture these cells and induce them to secrete significant quantities of

In comparison to Merck's recombinant vaccine,

commerciali- surface antigen, but subsequently dropped this line of development

sation of the Biogen vaccine followed a rather more

tortuous for fear that consumers would be suspicious of a vaccine produced

course. Like Rutter and the UCSF scientists, Murray

and the Biogen from cancer cells (Galambos, 1995, pp. 196e197; Edman, Gray,

team initially ran into problems with the limited

immunogenicity Valenzuela, Rall, & Rutter, 1980). However, in 1981 Rutter and his

of bacterially-produced surface antigen, and for a

while they too team began collaborating with yeast geneticist Benjamin Hall of the

looked into the expression of antigen in transformed

mammalian University of Washington. They found not only that yeast could be

liver cells, including human liver cancer cells (Gough

& Murray, induced to express the antigen in substantial quantities, but that

1982; Koshy et al., 1983; MacKay et al., 1981). The

UCSF team's the antigen was produced in a form that proved immunogenic

announcement that a strongly immunogenic form of

HBsAg could when injected into rabbits. Their findings were announced at the

be expressed in yeast provided the way forward for

Murray as for International Congress of Virology in Strasbourg in August 1981

the Americans. Teaming up with Albert Hinnen, one

of the sci- (Galambos, 1995, pp. 199e200; UCSF 1981; Valenzuela, Medina,

entists who had first demonstrated expression of

recombinant Rutter, Ammerer, & Hall, 1982).

DNA in yeast (Hinnen et al., 1978), Murray experimented

with Shortly before making their findings public, Rutter and his

different DNA constructs to see which was most

effective at team had filed an application for a US patent to cover the synthesis

expressing HBsAg. By early 1983 his team had

developed a strain of hepatitis B surface antigen in recombinant yeast. The patents

of yeast which produced acceptable levels of

immunogenically- were to be assigned to the University of California (Rutter,

active surface antigen (Hofschneider & Murray, 2001,

p. 52); and Valenzuela, Hall, & Ammerer, 1988).

6

By that time, however, Rut-

by August of that year, working now with

experimental pharma- ter was losing patience with the University and its failure to

cologist Huub Schellekens at the not-for-profit TNO

Primate Cen- establish a technology transfer company to handle IP arising from

ter in the Netherlands, had demonstrated that the

antigen research by its employees. With the commercial aspects of the

prevented hepatitis B infection in chimpanzees

(Hofschneider & hepatitis B work becoming increasingly onerous, and potential

Murray, 2001; Murray et al., 1984, p. 53). Announcing

the find- collaborators being offered positions in competitor companies,

ings, the British magazine New Scientist hailed “the

first report of a Rutter, Valenzuela and another collaborator, Edward Penhoet from

successful test with the genetically engineered product

in higher Berkeley, formed their own biotechnology company, Chiron, in

primates” (Anon, 1983). 1981 (Hughes, 2001b, pp.

100, 104e106; Hughes 2011, pp. 80e81).

The ability to produce a vaccine in the laboratory

meant little if In keeping with Rutter's views on using private funding to support

production could not be scaled up to a commercially

viable level, university research, they earmarked some of their stock “to be

however, and Biogen did not have the resources to

take this forward given back to the university, to recognize the general contribution

on its own. Nor did the company see a hepatitis B

vaccine as a priority the universities had made to the founding of Chiron. We . sort of

in its portfolio of potential products. Despite the

successful animal recognized the parentage, if you will, of this whole thing” (Pen-

trials, the documentation produced for the company's

initial public hoet, in Hughes, 2001b, p. 108).

offering in 1983 made only passing mention of the

vaccine, focusing Meanwhile, with production of an effective recombinant

instead on medicines such as insulin and interferon

(Rasmussen, vaccine now appearing increasingly likely, Merck moved on from

2014). It was left to Murray himself to champion the

vaccine proj- simply funding Rutter's research at UCSF, and now began to bring

ect. In November 1983 he approached John Beale at

Wellcome the work in-house. In 1982 they recruited the molecular biologist

Biotechnology Ltd. in Kent, to propose a development

deal. Beale and oncogene researcher Edward M. Scolnick to lead the com-

was a leading expert in commercial vaccine

development, who had pany's programme in virus and cell biology, and specifically to

led Glaxo's effort to commercialise the Salk polio

vaccine during the develop new capacity in recombinant DNA technology. Following

1960s. When Glaxo began to withdraw from vaccine

research to- Vagelos's strategy of using the hepatitis B vaccine as a vehicle to

wards the end of the decade, Beale had moved to

Wellcome explore the possibilities of the new technology, Scolnick focused

Biotechnology (Day, 2006). Like Merck, Wellcome

was one of the few first on the collaboration with Chiron, assuming personal over-

large pharmaceutical companies that continued to

pursue an in- sight of the vaccine development work and bringing in additional

terest in vaccines. Even so, Beale's initial response was

cautious, scientists to help scale up production (Galambos, 1995, pp. 182,

noting that “We are attracted by this product

opportunity but are 200e203). Driven now by the resources of a major pharmaceu-

keenly aware of the highly competitive nature of

research and tical company, production and clinical testing of the vaccine

development in this area .”

7

On the positive side,

while the po- developed quickly. By mid-1984, the system of mass-producing

tential profits might be small, there were other

strategic reasons for surface antigen in yeast cultures was taking shape, and Merck

developing a hepatitis B vaccine, which the company

“considered were able to report that their first trials of the vaccine in humans

however to be the'entry ticket' to newer markets eg the

US”. had proved effective. Larger clinical trials quickly followed, and the vaccine e now branded as Recombivax e was approved

for release, first in West Germany in May 1986, and then in the USA in July (McAleer et al., 1984; Schmeck, 1984; Jilg et al.,

1984; Zajac, West, McAleer, & Scolnick, 1986; Galambos, 1995, pp. 203e204).

8

Still, it was not until October 1984 that Wellcome and Biogen

announced a formal agreement to develop the vaccine (Anon, 1984).

Once the deal had been struck, Beale moved quickly. Biogen had been conducting preliminary clinical studies as early as

February

6

Rutter's claim to priority in achieving expression of HBsAg in yeast was contested by Ronald Hitzeman of Genentech.

Hitzeman was working on expressing interferon, but had realised that a yeast expression system might also solve the

immunogenicity problems confronting the vaccine researchers. The courts decided in Rutter's favour, on the grounds that he had

been first to achieve rather than just conceive of producing a vaccine in this way (Hitzeman v. Rutter, 2001).

7

Letter from John Beale (Wellcome Biotech, Kent) to I.Buchanan (Biogen, Geneva), 7 November 1983, Kenneth Murray

papers (Coll-1527), Edinburgh Uni- versity Library Special Collections.

8

Internal communication to multiple Biogen members from Iain Buchanan (Biogen) reporting on a meeting with John Beale

(Wellcome Biotech), 17 November 1983, Kenneth Murray papers (Coll-1527), Edinburgh University Library Special

Collections.

F. Huzair, S. Sturdy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 64 (2017) 11e21 16

9 1984,

and by June 1985 Beale was preparing registration batches of the vaccine and compiling the documentation necessary for

full- scale clinical trials.

10

The results of these trials were positive, and approval of the vaccine appeared imminent. But in the

meantime circumstances at Wellcome had changed. By 1986, the Wellcome Trust, which owned Wellcome Biotechnology, was

planning to sell off large parts of the company to raise funds for other activities, and was keen to maximise the value of shares in

the company. In that context, the hepatitis B vaccine project looked more like a liability than an asset, and Wellcome withdrew

from its agreement with Biogen.

11

In the end, Biogen signed a new manufacturing agreement with SmithKline Biologicals, a Belgian subsidiary of the American

company SmithKline Beckman, and one of the largest vaccine manufacturers in the world. The reasons for SmithKline's will-

ingness to invest in the vaccine remain unclear, given the wide- spread doubts about its likely profitability e but the company may

have decided to follow Merck and the Institut Pasteur in seeking to keep abreast of the latest production technology. In early

December 1986 the Belgian authorities granted marketing approval for the SmithKline vaccine under the trade name Engerix-B

(Ward, 1986). Approval of the vaccine for the US market would take longer: though a license application was submitted to the

FDA late the following year, approval would not be granted until September 1989, by which time SmithKline was already

marketing Engerix-B in more than sixty countries (Anon, 1988; Galambos, 1995, p. 204 n. 62).

4.3. Institut Pasteur

Third to market with a recombinant hepatitis B vaccine was the French team led by Tiollais. Following their sequencing of the

viral genome, Tiollais and his team initially focused on developing methods of producing HBsAg in E. coli. By April 1981 their

research had advanced sufficiently to file a US patent application specifying DNA sequences which coded for immunogenic

fragments of HBsAg, and describing how the expression of those fragments could be improved by combining the viral DNA with

certain vectors and promoter sequences (Charnay, Galibert, & Tiollais, 1984; Charnay, Gervais, Louise, Galibert, & Tiollais,

1980). Tiollais too soon ran into the problem of the weak immunogenicity of bacterially- produced antigen, but unlike his

competitors at Biogen and UCSF, he decided that mammalian cells rather than yeast offered a viable production system.

Experimenting first with recombinant mouse cells, by 1982 he had shown that such cells not only produced HBsAg in significant

quantities, but also that the antigen was effective in stimulating an immune response in rabbits (Dubois, Pourcel, Rousset, Chany,

& Tiollais, 1980; Pourcel, Dubois, Gervais, Drouet, & Tiollais, 1982). A year later, Tiollais filed a second US patent application

to cover this method of producing HBsAg; and two years after that he filed a third application detailing a particular combination

of HBsAg with a human receptor molecule that further enhanced immunogenicity (Tiollais, Chany, Dubois, Pourcel, & Louise,

1994).

9

Engerix-B, Summary for Basis of Approval, nd, available online at http://www.

fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ ucm110155.pdf, accessed 28 December 2015.

10

Letter from Michael Winter (Wellcome Biotech) to Kenneth Murray, 12 June 1985, Kenneth Murray papers (Coll-1527),

Edinburgh University Library Special Collections. An in-house volunteer study was underway at the Wellcome labora- tories in

Kent by September 1986: Progress report from M. Winter (Wellcome) to Biogen, 18 September 1986, Kenneth Murray papers

(Coll-1527), Edinburgh Uni- versity Library Special Collections.

11

Interview with Michael Winter, January 2015.

F. Huzair, S. Sturdy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 64 (2017) 11e21 17

Over the next two years, Tiollais and his colleagues continued to experiment to determine which parts of the viral DNA

should be included in the recombinant cells to produce the most effective vaccine (Milich et al., 1985), and what kinds of cells

offered the most convenient and productive culture medium, settling eventu- ally on Chinese hamster ovary cells. Not until April

1987 would the vaccine begin human trials (Anon, 1987). Manufactured by the Institut's own company Pasteur Vaccins under the

trade name GenHevac-B, the vaccine was licensed in France in May 1989 (Girard, 1988, p. 758). For reasons that remain unclear,

but may have to do with wider concerns about the safety of vaccines pro- duced from mammalian cells, the company judged that

GenHevac- B was unlikely to be approved outside France, so decided not to seek licenses elsewhere (Commission of the

European Communities, 1994, p. 6).

5. The impact of the recombinant hepatitis B vaccines

Given industry perceptions that vaccines were generally un- profitable, and the limited uptake of Merck's plasma vaccine,

initial expectations regarding the commercial performance of the re- combinant hepatitis B vaccines were decidedly modest. As

one of the Biogen scientists recalled: “[M]any people felt that the vaccines were not going to have the commercial value that

some of the other [recombinant] products would do. They were somewhat de-pri- oritised.”

12

This was reflected in the conservative way the new vaccines were marketed. Merck e the first company to bring its

recombinant vaccine to market e simply pitched Recombivax as a replacement for its earlier plasma vaccine, targeting the same

high- risk groups in rich countries and charging a “comparable” high price (Anon, 1986). SmithKline and Pasteur, as we shall

see, took a broader view, including low- and middle-income countries in their marketing efforts. But their principal markets still

lay in Europe and North America, where they followed closely on the pricing strategy set by Merck (Mowery & Mitchell, 1995,

p. 984).

In the event, the new vaccines were far more commercially successful than anticipated. In part this was due to public percep-

tions of their safety. As early as 1979, in his original patent appli- cation for a recombinant method of producing hepatitis B

antigens, Murray had declared that “the use of human sources for these antigens is disfavored because of the well recognized

contamina- tion problems in using human isolates” (Murray & Schaller, 1987, p. 4). In fact, experience would show that the

plasma vaccine was generally very safe. Nonetheless, similar statements about the plasma vaccine were recycled in the press

from 1983 onwards, as the recombinant vaccines entered first animal then human trials, then were introduced into practice. The

very artificiality of the new vaccines now appeared as an advantage, offering a reassuring im- age of purity and safety (Conis,

2011, pp. 160e161).

At the same time, shifts in perceptions of the risks posed by hepatitis B infection helped drive the uptake of the vaccine. As

evidence grew that the virus was a significant cause of liver cancer (Beasley, Lin, Hwang, & Chien, 1981), hepatitis B came

increasingly to be seen, not just as a sexually-transmitted disease of outsiders, but as a significant public health risk affecting

populations in wealthy as well as low- and middle-income countries. When, following a 1990 epidemic of measles, American

public health of- ficials launched a new programme of childhood vaccination to address a range of infectious diseases, hepatitis B

was included in that programme (Mowery & Mitchell, 1995, pp. 987e988; Mamo & Epstein, 2014, pp. 159e160; Conis, 2011, pp.

162e164). With

12

Interview with Michael Winter, January 2015.

increasing numbers of American schoolchildren now expected to undergo hepatitis B vaccination, the market for the recombinant

vaccines, and the profits they generated, far exceeded the manu- facturers' early expectations.

The unexpected commercial success of the recombinant hepa- titis B vaccines marked a turning point in the fortunes of the

nascent biotechnology industry. From their creation in the mid-to late 1970s, the first wave of biotech start-ups had survived

largely on the promise that they would eventually deliver profitable products. With the approval of Recombivax in 1986,

however, Chiron became “one of the few biotech enterprises with a product to sell” (Fisher, 1986), and by 1991 was the first

biotechnology company to turn an operating profit (Rasmussen, 2014, p. 122). In the case of Biogen, the success of Engerix-B

helped to rescue the company from almost a decade of financial difficulties (Rasmussen, 2014, p. 181; Eccles, Nohria, &

Berkley, 1992, pp. 104e106); ac- cording to one source, worldwide sales of Engerix-B approached $100 million in 1989 (Anon,

1990). For the big pharmaceutical companies, meanwhile, the success of the recombinant hepatitis B vaccines helped to

rehabilitate the idea that vaccines could be worth investing in, paving the way for the development of other highly profitable

vaccines, including the first “blockbuster” vac- cines against human papilloma virus (Wailoo, Livingston, Epstein, & Aronowitz,

2010).

In boosting both biotech and big pharma interest in vaccines, the recombinant hepatitis B vaccines also effected a more

general shift in the vaccine innovation system. Previously, vaccine research and development had been dominated by public and

charitable fund- ing, while the price of the resulting vaccines was determined in large part by the need to make them available to

populations in low- and middle-income countries as well as the global North. By the 1970s, however, the diminishing profit

margins associated with commercial manufacture and distribution of vaccines had led to all but a handful of companies

withdrawing from the market. By contrast, the recombinant hepatitis B vaccines were predominantly a private-sector initiative,

taking shape within and helping to articulate the developing network of interactions between academia, new biotech start-ups and

established pharmaceutical companies that was coming to dominate pharmaceutical innova- tion more generally. They also

displayed other features of the developing pharmaceutical innovation system e in particular the patterns of strict ownership and

control of intellectual property that were crucial for mediating the increasingly complex network of institutional interactions that

characterised it.

IP issues had been marginal to the earlier, predominantly public-sector vaccine innovation system. By contrast, as we have

seen, all the teams involved in developing the recombinant hepa- titis B vaccines applied for patents to protect their various in-

ventions, leading to complex licensing arrangements when it came to manufacturing the vaccines. Merck and SmithKline, for

instance, had to obtain licenses to three key recombinant hepatitis B patents assigned to the Pasteur Institute, the University of

California and Biogen respectively, as well as patents on a range of other biotechnological and manufacturing processes

(Mahoney, 2007, p. CS23) ea total of fourteen different patents in the case of SmithKline (Homma & Knouss, 1994, p. 52). To

reduce transaction costs, Merck, Pasteur and SmithKline entered into a series of joint venture agreements covering not only

cross-licensing of their respective patents, but also distribution of their vaccines in Europe and the USA. These agreements also

had the effect of minimising competition between the three companies, while preventing other companies from entering the

market (Commission of the European Communities, 1994). Consequently, despite the enormous growth in demand for the

vaccine, the price fell only slowly: according to one report, by 1990 Merck was offering the vaccine to US public-

F. Huzair, S. Sturdy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 64 (2017) 11e21 18

sector providers at a price of around seven or eight dollars per shot, but continued to charge private-sector providers nearly

double that amount (Asian Development Bank, 2001, p. 45). In ef- fect, the recombinant hepatitis B vaccines conformed more

closely to a pharmaceutical system increasingly characterised by the use of intellectual property to maximise profits than to an

older, pre- dominantly public-health-oriented system of vaccine development and distribution.

The high price of the recombinant hepatitis B vaccines also signalled a clear divergence between vaccine development for sale

in wealthy countries and for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). As Muraskin (1995) has shown, in many LMICs it was

a plasma vaccine rather than one of the recombinant vaccines that first achieved wide distribution. As early as 1984, shocked at

the price of the Blumberg-Merck vaccine, Alfred Prince, an expert in blood transfusion at the New York Blood Center, developed

an alternative flash-heat method of purifying the surface antigen from plasma. Prince's method was simpler, faster and more

resource-efficient than either Merck's or the Institut Pasteur's methods, producing larger quantities of vaccine from the same

amount of plasma. Patenting his method but waiving royalties, Prince made it available to anyone who wished to produce a

vaccine (Prince and Kwang, 1987; Muraskin, 1995, pp. 21e26, 60). In the absence of patent protection and faced with public

anxiety about the safety of plasma vaccines, manufacturers in the USA and Europe were uninterested in marketing Prince's

vaccine. In Asia, however, with support from an international task force of public health advocates, by the early 1990s a growing

number of man- ufacturers were producing and distributing the plasma vaccine, prices had fallen below $1 per dose, and

universal childhood immunisation against hepatitis B had become a realisable goal, at least for better-off Asian countries

(Muraskin, 1995, passim; Maynard, Kane, & Hadler, 1989).

The new recombinant vaccines were much slower to enter that market. Both SmithKline and Pasteur certainly made efforts in

that direction. Rather than reduce the price of their recombinant vac- cines for sale in poorer countries, SmithKline, in particular,

sought instead to represent the plasma vaccine as unsafe (Muraskin, 1995, pp. 202e210). Only with the emergence of local

producers e particularly in India, where an intellectual property system that privileged process over product patents made it easier

to circum- vent European and American patent restrictions e did prices fall to more accessible levels; by 2001 at least ten

producers, including three Indian companies, were supplying recombinant hepatitis B vaccines to domestic and export markets, at

prices approaching those of the plasma vaccines (Asian Development Bank, 2001, p. 45; Chakma, Masum, Perampaladas, Heys,

& Singer, 2011). In effect, the development and commercialisation of the hepatitis B vaccines was instrumental in the emergence

of a distinctly two-tier vaccine innovation system: the first tier geared towards producing vaccines for sale at a substantial profit

to rich-country markets; the second oriented toward producing cheaper vaccines for use in LMICs.

6. Conclusions

The development of the hepatitis B vaccines was instrumental in catalysing a major reconfiguration of the vaccine innovation

sys- tem, first in the US and Europe and subsequently in LMICs. That transformation was largely unanticipated e an accidental

conse- quence of local initiatives and innovations that only came together in the 1990s to create a coherent system. Seen in wider

perspective, it was facilitated by a series of policy decisions that deliberately aimed to harness biological research to the

commercial interests of the pharmaceutical industry. Our story is thus one of opportunistic innovation within a broader, enabling

policy environment.

From the late 1960s, as we have seen, government-funded medical researchers came under mounting pressure to demon- strate

that their work led to public benefit. At the same time, the very idea of public benefit was increasingly articulated in terms of the

appropriation and commercial exploitation of intellectual property, especially by the pharmaceutical industry. The develop- ment

of the Blumberg-Merck plasma vaccine represented an early, albeit ambivalent and ultimately unsuccessful attempt to realise this

idea in the realm of vaccine innovation. The new vision of pharmaceutical commercialisation as a proxy for public benefit began

to acquire greater solidity with the establishment of the biotechnology sector as an entrepreneurial intermediary between

academic bioscience and the pharmaceutical industry. Bolstered by the Bayh-Dole Act and other relaxations in patent law, the

biotechnology sector effectively incorporated intellectual property into a new asset-based business model for extracting

commercial value from scientific research. In this setting, however, attention focused primarily on developing new

biotechnological means of producing treatments such as insulin and interferon, which were expected to deliver substantial profits,

rather than on vaccines, which were no longer regarded as profitable.

Consequently, efforts to develop recombinant vaccines against hepatitis B were initially motivated more by contingent local

sci- entific and technical interests, including a desire among pharma- ceutical manufacturers to keep abreast of the latest

production technologies, than by any expectation of commercial success. In the event, the new vaccines confounded expectations

by proving very profitable, alerting pharmaceutical manufacturers to the commer- cial possibilities that other such vaccines might

offer. At the same time, the fact that a vaccine was among the first novel medical products to emerge from the new biotechnology

sector did much to reinforce the perception among policy makers that commerciali- sation did indeed offer an effective means to

deliver public health benefits, and that companies should be supported in this endeavour. Thus in 1994, the European

Commission decided that while a joint venture between Pasteur Mérieux (successor to Pas- teur Vaccins) and Merck to distribute

the hepatitis B and other vaccines was anti-competitive and excluded other companies from the market, this was outweighed by

the expectation that the Pasteur-Merck collaboration would accelerate innovation in an area of “genuine public health concern”,

and so should be allowed to go ahead (Commission of the European Communities, 1994, p. 18). In effect, the successful

commercialisation of the hepatitis B vaccines served to vindicate the expectations and interests that had informed policy on

biomedicine and biotechnology since the late 1960s.

Finally, the development of the hepatitis B vaccines also throws light on the global relations of the emerging vaccine

innovation system. Increasingly, this developed into a two-tier system. In North America and Europe, the latest biotechnologies

were har- nessed to produce new high-cost recombinant vaccines which served the demands of commercial profit as much as

public health. Meanwhile, the public health needs of less wealthy countries were relegated to a second tier of institutions and

initiatives which depended, at least initially, on cheaper plasma-based production technologies. Over time, a combination of

philanthropic effort by non-profit organisations and the growth of local manufacturing capability resulted in a substantial transfer

of recombinant hepa- titis B vaccine technology from rich to poorer countries. Yet the relationship between the two tiers of the

vaccine innovation sys- tem remains problematic.

As a number of critics have observed, international efforts to promote the roll-out of hepatitis B and other vaccination pro-

grammes, including expansion of indigenous vaccine production capacity, often proceed in the absence of demonstrated need or

F. Huzair, S. Sturdy / Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 64 (2017) 11e21 19

utility, and typically tend to favour the introduction of high-cost, high technology products over cheaper and more appropriate

vaccines (eg Graham, 2016; Hardon & Blume, 2005; Madhavi, 2003, 2005). At the same time, IP regimes in LMICs are in many

instances shifting to more closely resemble those in the global North, through enforcement of the Agreement on Trade-Related

Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS) of 1994, and as countries such as India seek to become global suppliers of

pharmaceuticals in their own right (Greene, 2014, pp. 253e257; Sunder Rajan, 2011). As a result, not only is vaccine technology

transfer becoming more difficult, but it is increasingly likely to favour the commercial in- terests of private corporations over

public health concerns (eg Hendriks, 2012; Mahoney, Pablos-Mendez, & Ramachandran, 2004; Milstien & Kaddar, 2006). In

effect, the commercial orientation that drove the emergence of a high-cost vaccine system in the USA and Europe is itself being

transferred to LMICs at the expense of the kind of low-cost vaccines that might better serve the needs of local populations.

The development of the hepatitis B vaccines was pivotal in the assimilation of vaccine innovation to an emerging

biopharmaceu- tical innovation system, including the creation of new global mar- kets for recombinant pharmaceuticals. As such,

it also exemplifies the tensions inherent in the new innovation system, particularly between the demands for commercial

profitability on the one hand, and the expectation of public health benefit, especially in LMICs, on the other.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Edinburgh University Special Collections for providing access to the Ken Murray papers, and especially to

Clare Button for guidance and assistance. We thank all those who kindly consented to be interviewed for this project. Stuart

Blume, Stuart Hogarth and Lara Marks provided generous and constructive feedback on an earlier draft of this paper, as did two

anonymous reviewers for this journal. This study was supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award in Medical

Humanities, “Making Genomic Medicine”, award number WT100597MA.

References

Anon. (1983). New hepatitis vaccine developed. New Scientist, 99(1370), 409. Anon. (1984). Biogen's rDNA hepatitis B

vaccine. The Pink Sheet 15 October https:// www.pharmamedtechbi.com/publications/the-pink-sheet/46/042/biogens-

rdna-hepatitis-b-vaccine Accessed 28 December 2015. Anon. (1986). Merck's Recombivax HB DNA-derived hepatitis vaccine

approved June 23 after five-month review. The Pink Sheet 28 July https://www.pharmamedtechbi.

com/publications/the-pink-sheet/48/030/mercks-recombivax-hb-dnaderived-

hepatitis-vaccine-approved-june-23-after-fivemonth-review-merck Accessed 29 March 2016. Anon. (1987). Parisians put new

hepatitis B vaccine to the test. New Scientist,

114(1558), 24. Anon. (1988). Biogen/SmithKline hepatitis B licensing agreement. The Pink Sheet 11 April

https://www.pharmamedtechbi.com/Publications/The-Pink-Sheet/50/

015/BIOGENSMITHKLINE-HEPATITIS-B-LICENSING-AGREEMENT Accessed 28 December 2015. Anon. (1990). Biogen

first quarter revenues up 50% to $10.3 Mil. The Pink Sheet 16 April

https://www.pharmamedtechbi.com/publications/the-pink-sheet/52/016/

biogen-first-quarter-revenues-up-50-to-103-mil-merck-sublicenses-hepatitis- b-patents-licensing Accessed 16 September 2015.

Apple, RD (1989). Patenting university research: Harry Steenbock and the Wis-

consin Alumni Research Foundation. Isis, 80(3), 374e394. Bank Pembangunan Asia. (2001). Immunization financing in

developing countries and the international vaccine market: Trends and issues. Manila: Asian Devel- opment Bank.

http://vaccine-safety-training.org/tl_files/vs/pdf/ADB.pdf Accessed 8 August 2016. Beasley, RP, Lin, C., Hwang, L., & Chien, C.

(1981). Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus: A prospective study of 22,707 men in Taiwan. Lancet, 2(8256),

1129e1133. Berman, EP (2008). Why did universities start patenting? Institution-building and

the road to the Bayh-Dole Act. Social Studies of Science, 38(6), 835e871.

Bertland, AU, Tytell, AA, Lampson, GP, & Buynak, E. (12 April 1977). Method for

purifying hepatitis B antigen. US Patent 4017360. Filed 14 May 1975. Blumberg, BS (1977). Australia antigen and the biology of

hepatitis B. Science,

197(4298), 17e25. Blumberg, BS (2003). Hepatitis B: The hunt for a killer virus. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press. Blumberg, BS, Harvey, J., Alter, HJ, & Visnich, S. (1965). A 'new' antigen in leu-

kemia sera. Journal of the American Medical Association, 191(7), 541e546. Blumberg, BS, & Millman, I. (18 January 1972).

Vaccine against viral hepatitis and

process. US Patent 3636191. Filed 8 October 1969. Blume, S. (2008). Towards a history of 'the vaccine innovation system,'

1950e2000. In C. Hannaway (Ed.), Biomedicine in the twentieth century: Practices, policies, and politics (pp. 255e286).

Amsterdam: IOS Press. Blume, S., & Geesink, I. (2000). Vaccinology: An industrial science. Science As Cul-

ture, 9(1), 41e72. Burrell, CJ, Mackay, P., Greenaway, PJ, Hofschneider, PH, & Murray, K. (1979). Expression in Escherichia

coli of hepatitis B virus DNA sequences cloned in plasmid pBR322. Nature, 279(5708), 43e47. Chakma, J., Masum, H.,

Perampaladas, K., Heys, J., & Singer, PA (2011). Indian vaccine innovation: The case of Shantha Biotechnics. Globalization and

Health, 7, 9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-7-9. Available at:. Charnay, P., Galibert, F., & Tiollais, P. (31 January 1984).

Nucleotidic sequence coding the surface antigen of the hepatitis B virus, vector containing said nucleotidic sequence, process

allowing the obtention thereof and antigen obtained thereby. US Patent 4428941. Filed 30 April 1981. Charnay, P., Gervais, M.,

Louise, A., Galibert, F., & Tiollais, P. (1980). Biosynthesis of hepatitis B virus surface antigen in Escherichia coli. Nature,

286(5776), 893e895. Charnay, P., Mandart, E., Hampe, A., Fitoussi, F., Tiollais, P., & Galibert, F. (1979b). Localization on the

viral genome and nucleotide sequence of the gene coding for the two major polypeptides of the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBs

Ag). Nucleic Acids Research, 7(2), 335e346. Charnay, P., Pourcel, C., Louise, A., Fritsch, A., & Tiollais, P. (1979a). Cloning in

Escherichia coli and physical structure of hepatitis B virion DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United

States of America, 76(5), 2222e 2226. Chiron, JP, Coursaget, P., & Yvonnet, B. (1998). Philippe Maupas: Inventeur du vaccin

contre l'hépatite B. Revue d'histoire de la pharmacie, 86(319), 279e292. Coller, JA, Millman, I., & Blumberg, BS (18 March

1975). Process of viral diagnosis

and reagent. US Patent 3872225. Filed 12 July 1972. Commission of the European Communities. (1994). Commission

decision 94/770/EC of 6 October 1994 relating to a proceeding pursuant to article 85 of the EC treaty and article 53 of the EEA

agreement (IV/34.776-Pasteur Mérieux-Merck). Official Journal of the European Communities, L 309, 1e23. Conis, E. (2011).

'Do we really need hepatitis B on the second day of life?' Vacci- nation mandates and shifting representations of hepatitis B.

Journal of Medical Humanities, 32(2), 155e166. Day, M. (2006). Obituary: John Beale. British Medical Journal, 332(7534), 181.

Doganova, L., & Muniesa, F. (2015). Capitalization devices: Business models and the renewal of markets. In M. Kornberger, L.

Justesen, J. Mouritsen, & AK Madsen (Eds.), Making things valuable (pp. 109e125). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Dubois,

MF, Pourcel, C., Rousset, S., Chany, C., & Tiollais, P. (1980). Excretion of hepatitis B surface antigen particles from mouse cells

transformed with cloned viral DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 77(8), 4549e4553. Eccles,

RG, Nohria, N., & Berkley, JD (1992). Beyond the hype: Rediscovering the

essence of management. Washington DC: Beard Books. Edman, JC, Gray, P., Valenzuela, P., Rall, LB, & Rutter, WJ (1980).

Integration of hepatitis B virus sequences and their expression in a human hepatoma cell. Nature, 286(5772), 535e538. Eisenberg,

RS (1996). Public research and private development: Patents and technology transfer in government-sponsored research. Virginia

Law Review, 82(8), 1663e1727. Fisher, LM (1986). Biotechnology light now shines on Chiron. New York Times, 13 October

http://www.nytimes.com/1986/10/13/business/biotechnology- spotlight-now-shines-on-chiron.html Accessed 24 December 2015.

Galambos, L. with Sewell, J. (1995). Networks of innovation: Vaccine development at Merck, Sharp & Dohme, and Mulford,

1895-1995. Cambridge: Cambridge Uni- versity Press. Galibert, F., Mandart, E., Fitoussi, F., Tiollais, P., & Charnay, P. (1979).