Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Assessment of Social Adjustment: A Review of Techniques: Archives of General Psychiatry April 1975

Загружено:

Anonymous 8HCovBzERDОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Assessment of Social Adjustment: A Review of Techniques: Archives of General Psychiatry April 1975

Загружено:

Anonymous 8HCovBzERDАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/22039208

The assessment of social adjustment: A review of techniques

Article in Archives of General Psychiatry · April 1975

Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

119 661

1 author:

Myrna M Weissman

Columbia University

878 PUBLICATIONS 76,207 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

WHO. Interpersonal psychotherapy View project

EMBARC View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Myrna M Weissman on 18 May 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

The Assessment of Social Adjustment

A Review of Techniques

Myrna M. Weissman, PhD

Interest in the community adjustment of psychiatric patients has ACNP) task force to develop guidelines for the evaluation

led to the development of rating techniques for its evaluation. Selec- of psychotropic medications.

tion of an appropriate scale for the task should include a review of its Given these interests, the trends for improvement of re¬

item content, anchor points, coverage, method of obtaining informa-

search techniques, and the availability of several social ad¬

tion, informant, psychometric properties, precision, cost, scoring,

and instructional material. justment scales, a review seems timely. This report will

While no scale is without limitations, this report describes 15 cur- describe current techniques for assessing social adjust¬

rently available scales that meet many of the important criteria for ment in adults and criteria for evaluating them. The core

assessing social adjustment and are sufficiently developed to be use- of the report will be a description of 15 scales that meet

ful in evaluative research. This review also contains a list of pertinent many of the important criteria. The content, adminis¬

references to the scales and a guide to the literature on behavioral tration, psychometric properties, feasibility, advantages,

rating scales. limitations, and references for each scale will be described

briefly. References 1-12 list reports that can be used as a

Therepast has been an unprecedented interest over the

two decades in community and social adjust¬

ment of psychiatric patients. It is reflected in community

guide to other behavioral rating

SOCIAL ADJUSTMENT

scales.

psychiatry training programs, studies of the posthospital Definition and Components

adjustment of psychiatric patients, epidemiologie commu¬ Social adjustment, broadly defined, is the interplay be¬

nity surveys, and, more recently, in prophylactic trials of tween the individual and the social environment. Specific

drugs and psychotherapy. A natural growth of the shift in ways of behaving, referred to as roles, are commonly ac¬

psychiatry from custodial care to therapy and prevention, cepted as and the individual is perceived in

appropriate

the trend gained momentum with the opening of the com¬ terms of the way his role performance conforms to the

munity mental health centers in the 1960s and the in¬ norms of his referrant group.

crease in outpatient care. This trend has both mandated

The major roles any individual assumes are a function

and been a consequence of an increased awareness that of age and may be a function of psychopathology. Nor¬

mental disorders occur in a social system and that the pa¬

tient's family life, friendships, and work patterns may

mally, an adult will function in most of the following

roles: occupational; marital, as a spouse and parent; within

have an impact on treatment and course. an extended family (parents, siblings, and close relatives);

The expansion into the social world of the patient in¬ and in the community. While there is overlap between

volved the addition of new measures of disturbance—that

of social adjustment—that were distinct from the abnor¬ symptoms and social adjustment, they may also be rela¬

malities of thoughts or symptoms. A number of scales

tively independent, eg, some persons can function reason¬

were developed for the assessment of social adjustment.

ably well although symptomatic, and others may function

The first ones were used for evaluating the posthospital poorly although asymptomatic. Symptoms are primarily a

reflection of internal psychological or physical states that

adjustment of schizophrenic patients who had been dis¬ may have consequence in social relations. Social adjust¬

charged on a regimen of the new tranquilizers. Others ment is a reflection of the patient's interactions with oth¬

were developed primarily to assess psychotherapy out¬

ers, satisfactions and performance in roles, which are

come in selected outpatient populations. more likely modified by previous personality, cultural,

In the last few years especially, evaluation of treat¬ and family expectation. There is debate about the inde¬

ment effectiveness and utilization has become an impor¬

tant issue in mental health. In a parallel development,

pendence of symptoms and social functioning. A resolu¬

tion requires that they be measured separately and as ac¬

there has been concern about refining study methods and

curately as possible. In this way subgroups of patients in

standardizing evaluative techniques. These interests are whom the relationship may differ can be identified. These

reflected in the development of utilization review proce¬ different subgroups may require different therapeutic in¬

dures in community mental health centers, and in the terventions.

establishment of a joint Food and Drug Administration-

American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (FDA- Evaluating Social Adjustment Scales

Criteria for

In choosing a social adjustment instrument, there are

certain criteria that an investigator should consider, while

Accepted for publication Sept 20, 1974.

From the Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine,

recognizing that no scale will fulfill all of them. These cri¬

and the Depression Research Unit, Connecticut Mental Health Center, New teria are as follows:

Haven. Content.—The content of an instrument should be eval¬

Read in part before the 11th annual meeting of the American College of uated in terms of the areas assessed and the anchor points

Neuropsychopharmacology, San Juan, Puerto Rico, Dec 5, 1974. for making the assessments. The areas assessed should be

Reprint requests to the Depression Research Unit, Connecticut Mental

Health Center, 100 Park St, New Haven, CT 06511 (Dr. Weissman). extensive and have broad coverage. To evaluate what this

Downloaded from www.archgenpsychiatry.com at Columbia University, on May 24, 2010

coverage might be, the components of social adjustment otherwise be lost.

Should be considered. Social adjustment is not unitary or

a In-Person Interview.—The in-person interview is the

a global concept. The concept includes functioning in dif¬ most costly method, requiring the most skilled staff. The

ferent roles. Within each role, functions can be further actual degree of skill varies with the nature of the assess¬

subdivided into instrumental and affective tasks, or be¬ ment. Structured interviews with precoded descriptive

havior and attitudes in roles. Certain behaviors may not items require the least trained interviewer. Unstructured

be role-dependent and may be common to all roles, such as interviews or global items, which necessitate clinical judg¬

involvement, reticence in relationships, satisfaction, ments, require the most training and experience. The

and hostility with others. A rating instrument that as¬ semistructured interviews lie somewhere between. In a

sesses many of these discrete components of social adjust¬ semistructured interview, lead questions are provided and

ment offers more precision and may have greater utility in the interviewer asks additional questions to elicit infor¬

classifying or in differentiating treatment effects. mation necessary to make the final rating. Training is re¬

Discretely defined rather than global anchor points for quired to insure that the interviewer asks sufficiently ap¬

making these assessments further contribute to pre- propriate questions so that reliable informant response

ciseness. Global response ratings disclose only a few facets can be obtained.

of the complex changes that can occur in patients and are The disadvantages of this method are the cost, inter¬

less desirable. Operationalizing both the discrete compo¬ viewer preparation and training, and the potential inter¬

nents of the behaviors assessed and the anchor points is viewer bias. The advantage is that the most complete in¬

inherently difficult, due to the value judgments implicit in formation can be obtained, since the patient's own

their definitions and the questions then raised about what responses as well as an evaluation of these responses can

should be defined as normal. A number of scales have dealt be rated. The interviewer may be able to calm the dis¬

with these issues by measuring adjustment in terms of turbed patient who might otherwise be unable to partici¬

amount of dysfunction, or by using broad dimensions of pate, can detect the tendency to underreport or falsify,

behavior and global ratings. and can make efforts to have the subject give accurate in¬

Method of Obtaining Information.—There are a number formation.14

of options in the method and source of information. De¬ Given the initial cost and time investment of most re¬

pending on cost, intent, and feasibility, each has its ad¬ search studies, the in-person interview method is prefer¬

vantages and limitations. able for completeness. However, there is much to be said

Self-Report Inventories.—Self-report inventories contain for the self-report inventory or use of both methods to¬

a list of straightforward items that the informant is asked gether, and neither method compensates for a poorly de¬

to rate in order to describe himself or the patient, in the signed or inadequately tested questionnaire.

case of relative ratings. The response points are usually

Informant

global (eg, "not at all" to "extremely"). Such inventories

have the advantage of economy, as a skilled interviewer Information about the patient's social adjustment gen¬

and a training program are not required. A research as¬ erally is obtained by one of three sources: the patient, a

sistant may remain with the informant during the rating significant other, or clinical records.

in order to assure completeness. Illiterate informants re¬ The Patient as Informant—The patient is the most direct

quire that the assistant read the inventory. The removal and available source of information in outpatient studies.

of interviewer bias and cost are important advantages of Nonpsychotic outpatients, especially depressives, can be

this method. reasonably reliable informants. The use of other infor¬

It has disadvantages with psychotic and delusional pa¬ mants may be unfeasible in studies in which the patient

tients who tend to underreport their impairments,13 or has never been hospitalized, since the family may not be

with patients too disturbed to complete the task, under¬ involved.17 The disadvantage of this method is that only

stand the intent of the questions, or who desire to falsify the bias of the patient is rated. Whether this is more or

their response.14 less valid than the bias of other informants is an open

Mail Questionnaires and Telephone Interviews.—The mail question, and additional work is needed in comparing data

questionnaire is the least expensive method because it from patient and significant other informants.

does not require staff time to administer. However, as Ho- Significant Others as Informants.—In this method a per¬

garty15 points out, reliability is questionable, completeness son knowledgeable about the patient, usually a close rela¬

often inadequate, and sensitive material cannot be elic¬ tive, is asked to rate the patient's adjustment. It is an im¬

ited. Illiteracy, position preference, and underresponse to portant source of information in studies of schizophrenics

emotionally laden material also limit its use.16 Telephone discharged from the hospital, because these patients tend

interviews present similar problems and advantages with to underreport and misrepresent impairments. In addi¬

the exception that interview completeness and response tion, the families of schizophrenics are usually involved

rate are easier to control by telephone. during the treatment course and are more apt to be avail¬

Mail and telephone interviews have definite value in able.

large-scale follow-up evaluations, in which brief and ob¬ The disadvantages are that a patient must have a rela¬

jective assessments are useful, when the patient refuses tive or close friend who is willing to cooperate. Problems

an in-person interview, or where geographic mobility in the choice of relative and agreement between relatives

makes interviewing impractical. Relatively straight¬ have been well reviewed by Hogarty15 and by Clausen.18

forward factual information can be obtained that would Records.—The use of records for information is the least

Downloaded from www.archgenpsychiatry.com at Columbia University, on May 24, 2010

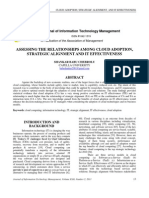

Table 1.—Detailed Characteristics of 15 Scales Assessing Social Adjustment

Instruments

Normative Social Inef¬ Mandel Social Personal Ad¬ Katz Personality

Social Adjust¬ fectiveness Adjustment Adjustment justment and Adjustment Social Net-

Characteristics ment Scale Scale Scale Inventory Role Skills Scale work Scale

Content

Occupational

Community

Marital Family Family Family

Parental

Extended family

Economic

Instrumental (I), affective (A) I, A I, A

Items—defined (D), global (G)

Ratings—D, G

Number of items 27 15 37 33 118 205 17

Number of ratings 4

Time period assessed Varies Varies Past 3 mos Past mo 3 weeks Present

Method

Self-report

Mail questionnaire Optional

In-person interview

Structured

Semistructured

Unstructured

Informant

Patient

Significant other Optical

Records

Psychometric Properties

Reliability No Yes No Yes Yest Yes Yes

Validity Yes Yes No No Yest Yes Yes

Sensitivity No Yes No No Yes Yes Yes

Scoring system No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Other

Completion time 1 hr 1 hr 25-45 min.

Forms—precoded (P), uncoded (U) U

Training manual No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No

(Continuedon page 360)

expensive or reliable method. Unless records are specifi¬ a few minutes and is comprehensive is unattainable. As

cally set up for research purposes, they tend to be variable Spitzer and Endicott note, a comprehensive evaluation re¬

and incomplete. quires about an hour. A more lengthy one results in inter¬

A combination of information sources is the most ex¬ viewer and subject fatigue and annoyance.

pensive and variable. If uniform sources of information Scoring.—A well-developed, quantitative scoring system

are not available on all patients, then comparisons be¬ and precoded score sheets are important in processing and

tween patients are difficult to make. analyzing data.

Psychometric Properties.—An instrument should possess Training.—Results may differ between research teams

demonstrated reliability, validity, norms, and sensitivity because of divergent interpretation of the rating instru¬

to change. The various kinds of reliability and validity ments. A developed training program and instructional

have been well described.18 Spitzer and Endicott14 have material are highly desirable.

made an excellent point in discussing validity. As they

SCALES

note, the investigator should have evidence for concurrent

validity of the instrument as a measure of the dimension There are innumerable scales that include assessments

in which he is interested. of social functioning. Many of them are limited in scope,

Other Factors Contributing to a Scale's Value undeveloped, or developed for one particular study. These

have not been included.

Time Period Assessed.—The time period under assess¬ Of the scales reviewed, 15 sufficiently met the criteria to

ment should be explicitly stated. This insures preciseness be potentially useful. Among these are several of the

and enables the investigator to differentiate long-stand¬ earliest scales developed during the 1950s. These have

ing patterns of adjustment from short-term effects that been included for their historical interest, since many of

may be treatment-related. It reduces confusion for the in¬ the later scales were derived from them. Each scale will be

formant and helps to focus the questions. described briefly, according to the criteria previously set

Length of Time to Administer.—An assessment that takes forth. Table 1 describes the 15 scales by these criteria.

Downloaded from www.archgenpsychiatry.com at Columbia University, on May 24, 2010

Table 1.—Detailed Characteristics of 15 Scales Assessing Social Adjustment (Continued)

instruments

Social Current & Structured &

Community Social Dysfunction Psychiatric Psychiatric Past Psycho- Scaled Inter- Social

Adaptation Disability Rating Status Evaluation pathology view to Assess Adjustment

Schedule Scale Scale Schedule Form Scales Maladjustment Scale

Content

Occupational

Community

Marital

Parental

Extended family

Economic

Instrumental (I), af¬

fective (A) I, A I, A I, A Not differentiated I, A I, A

Items—defined (D),

global (G)

Ratings—D, G Usually D

Number of items 217 49 21 321 27 171 60 48

Number of ratings Varies 11

Time period assessed Present Present Today or Past week Past week Past mo; age Past mo Past 2

past week &mo &mo 12yron mo

Method

Self-report

Mail questionnaire

In-person interview Optional Optional

Structured

Semistructured

Unstructured

Informant

Patient

Significant other

Records

Psychometric Properties

Reliability Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Validity Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Sensitivity Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Scoring system Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Other

Completion time 30-60 min 45-90 min 30-45 min 30-50 min 30-50 min 1-2 hr 1 hr 45-60 min

Forms—precoded (P),

uncoded (U)

Training manual Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

* Informant includes patient and two observers.

t Available on earlier version only.

Early Scales unstructured, in-person interviews, one with the patient

and one with a relative. A total of four ratings are ob¬

1. Normative Social Adjustment Scale.202-—This scale as¬ tained from the two interviews and a final rating com¬

sesses employment, economics, family life (marital, paren¬ bines the judgment of all four ratings. The time period is

tal, and extended), and community. Twenty-seven items unspecified. Interrater reliability is acceptable and valid¬

are rated on a 5-point scale with defined response points. ity, as sensitivity to change under different treatments, is

Information is collected by an hour-long semistructured presented. There is a scoring system and instructional ma¬

interview with the patient. The time period assessed terial is available. This scale is important because it laid

varies from four weeks to one year. Reliability, scoring, the groundwork for the development of later scales. The

sensitivity, and norms are not reported, and validity data authors do not recommend its use currently because of the

are limited. One of the earliest scales, it has broad cov¬ cumbersome interview method and the reliance on clinical

erage of the major role areas and includes instrumental impressions for ratings (B. Lieberman, PhD, and M. Par-

and affective role assessments. loff, PhD, written communication, 1972).

2. Social Ineffectiveness Scale.-3 2ß—This scale assesses 3. Mandel Social Adjustment Rating Scale.27 :,°—This scale

the patient's ineffectiveness in important relationships in¬ assesses the extent to which a person adapts to societal

cluding own and marital family, occupational and social norms in the areas of occupation (as a worker, student,

associations, and with the interviewer. Fifteen defined and retired person); family life (including marital, paren¬

categories are rated on a 5-point global scale by a psychia¬ tal, and extended); economic situations; and health, re¬

trist and a concealed rater. The psychiatrist conducts two ligious, residence, and community adjustment. Thirty-

Downloaded from www.archgenpsychiatry.com at Columbia University, on May 24, 2010

seven operationally defined items are rated on a 5-point using the earlier scale. This earlier version has been used

scale with discretely defined response points. Information to evaluate the effectiveness of a veteran's hospital psy¬

is collected from the subject in an unstructured interview. chiatric program and the PARS III has been used with

The time period assessed is unspecified on most items and outpatients attending a community mental health center

varies from weekly to monthly on others. Data on reliabil¬ and receiving counseling.

ity, validity, norms, and sensitivity to treatment are not The precoded mail questionnaire form is economical.

published. There is a scoring system and manual. The earlier versions have undergone more development

This scale has excellent coverage of the major roles and than this later version. Coverage of role performance is

includes a section for retired persons, so that it is useful limited to instrumental performance and management

for the elderly. It is comprehensive, covers both instru¬ skills. Community and occupational adjustment are well-

mental and affective performance, and has well-defined assessed and a substantial portion of the scale deals with

response points. The unstructured interview method and symptoms. The authors note some problem with missing

variable time periods assessed may present problems in data and response rate with the mail questionnaire.

interrater reliability. 6. The Katz Adjustment Scale-Relative's Form (KASR).4045

The Significant Other as Informant —Symptomatic behavior and life-situation adjustment of

patients in the community are assessed. A self-report in¬

The significant other as informant has been comprehen¬ ventory, 205 items are rated on a 4-point global scale by a

sively reviewed in reports by Fiske and Hogarty, from a close family member who has recently interacted with the

monograph prepared by Waskow and Parloff.12 The mate¬ patient. Items are clearly stated and require only a sixth

rial on Katz has been derived from that report. grade reading level. Twenty-five to 45 minutes are re¬

4. Social Adjustment Inventory Method.3135—The pa¬ quired for completion. A three-week time period is as¬

tient's adaptation in social and family relations, work, sessed.

self-care practices, and antisocial behavior is assessed. A The scale contains the following five sections: a 127-item

mail questionnaire, 33 global items are rated on a 6-point rating of symptoms and social behavior; a 16-item rating

defined scale by a significant other. A home visit is made of performance at socially expected tasks; a 16-item rat¬

to nonresponders. There are separate forms for women ing of the relative's expectation for the performance of

and men. The method was developed for measuring the these tasks; a 23-item rating of free time activities; and a

impact of a veteran's hospital treatment program on the 23-item rating of the relative's satisfaction with perform¬

adaptation of patients returned to the community and has ance of free time activities. This scale has been widely

been used primarily with this population. Instrumental used over the past decade in a variety of settings, and

performance in community and work roles is assessed. In¬ with heterogeneous diagnostic and nonpatient popula¬

formation is obtained on the patient's prehospital adjust¬ tions. There are considerable data available on reliability,

ment during the past two years, which serves as a base validity, sensitivity, and norms, as well as instructional

line, and on posthospital adjustment in the past three material and a color movie film for training purposes.

months. Data are available on reliability, but not on valid¬ This scale is excellent as an assessment of the patient's

ity. The method for collecting available information was instrumental performance in the family and recreational

tested by examining the enrollment of patients, recruit¬ participation. Marital, parental, and extended family rela¬

ment of informants, and transmission of information, and tions have less coverage and may require supplementa¬

was considered efficient by these criteria. There is a scor¬ tion. Relative cooperation is reported to be good. The ex¬

ing system but the form is not precoded. Considerable in¬ tensive development and use of this scale makes it an

formation is available on the recruitment of informants, attractive relative informant inventory.

timing of assessments, and patterns of informant cooper¬ The Patient as Informant

ation.

5. Personal Adjustment and Role Skills (PARS III).36 39- 7. Personality and Social Network Adjustment Scale.46-48—

Symptoms and adjustment in household management, Broad areas of the patient's adjustment in society, work,

parenthood, employment, social participation, and use of associational and family groups, and within himself are

alcohol and drugs are assessed. This is the third revision of assessed. A self-report inventory, 17 globally defined

a scale designed to measure community behavior and ad¬ items are rated on a 5-point global scale by the patient.

justment of former adult psychiatric patients. All three The form has been used as a mail questionnaire. Earlier

versions were developed on veteran's hospital psychiatric work using a mail questionnaire with a relative informant

patients. The PARS III consists of a 120-item form for proved unfeasible due to insufficient relative cooperation.

men and a 115-item form for women. A self-report inven¬ Moderate repeat reliability data and evidence for validity

tory, it is completed by the patient's relative and has been are presented. The scale has been used primarily to eval¬

designed for use as a mail questionnaire. Ratings are uate the treatment effects of a therapeutic community or

made on a 5-point global scale. The time period assessed is with hospitalized psychiatric patients. The time period as¬

"the last month." Reliability and validity has been estab¬ sessed is "at present." The scale is simple and quick to

lished on an earlier version of the scale, which was shorter complete and requires no training. There is a scoring sys¬

and was not administered as a mail questionnaire. tem. The form is not precoded.

A scoring system, results of factor analysis, and an in¬ This scale is brief and economical. However, the data

strumental manual are available. The form is precoded. obtained may be limited in complexity. Role coverage is

Norms are being prepared for state hospital patients, limited and there is no specific assessment of marital or

Downloaded from www.archgenpsychiatry.com at Columbia University, on May 24, 2010

Table 2.—Comparison of Three Adjustment Scales*

Current & Past

Psychiatric Status Psychiatric Evaluation Psychopathology

Schedule (PSS) Form (PEF) Scales (CAPPS)

Coverage Symptoms & impairment in daily Same as PSS plus characteristics Similar to PEF plus history relevant

routine, leisure time, alcohol & of present illness & major reason to severity, prognosis, & diag¬

drug use & role functioning as for admission nosis

wage earner, housekeeper, stu¬

dent, mate, & parent

Items 321 discrete descriptions of be¬ 27 broad dimensions of behavior 171 global items with guiding defi¬

havior rated on dichotomous with guiding definitions on 6- nitions rated on 6-point scale

scale point scale

Time period Past week & past mo for role func¬ Same as PSS Past mo & age 12 yr to past mo

assessed tioning, alcohol, & drug use

Source of informa¬ Patient informant Multiple sources (patient, family, Same as PEF

tion & case records)

Method Structured interview Interview guide optional Same as PEF

Time to complete 30-40 min 30-50 min with interview guide 1-2 hr with interview guide

Instrument 21-page step-down booklet & score 9-page step-down booklet & score 13-page protocol with 26-page in¬

sheets sheets terview schedule

Administration Training guides available; requires Training guides available; requires Training guides available; same as

less clinical experience for ad¬ more clinical experience for ad¬ PEF

ministration ministration

Data processing Computer programs available for Same as PSS Same as PSS

scoring_

* R. L. Spitzer and J. Endicott, unpublished data, 1972.

parental role. Individual assessments and response points Items are precoded and designed for computer analysis.

are global. It is currently being used as an outcome assess¬ This scale is designed for the assessment of social dis¬

ment in psychotherapy. ability in chronic patients in order to plan rehabilitation

8. Community Adaptation Schedule (CAS).4"-52—This scale programs. As such, it includes excellent coverage of physi¬

assesses behavior, affect, and cognition in work, family cal disability, psychopathology, occupational and recrea¬

(marital and parental), and social: larger commercial and tional limitations, and environmental modifiers of per¬

professional communities. It is a 217-item self-report in¬ formance. Role performance covers a small portion of the

ventory, completed by the patient and rated on a 6-point scale. Marital and parental roles are absent, as are affec¬

scale, which includes measures of intensity, attitude, and tive tasks.

frequency. The time period assessed is "at the present It has been used with medical patients, for which it is

time." Data on reliability, validity, internal consistency, well-designed. It is less suitable in psychiatric studies be¬

and instructional material are available. The scale takes cause of its emphasis on physical impairments.

30 to 60 minutes to complete and requires sixth grade level 10. Social Dysfunction Rating Scale (SDRS).56-eo-Subjéc¬

reading ability. Norms for various patient and nonpatient rive and objective performance in the self, interpersonal,

groups are published in a manual. A scoring system and and performance systems are assessed. Twenty items are

templates are available. rated on a 6-point ordered-rating scale. A semistructured

The most definitive application of the scale has been interview conducted by a trained professional social

in multitreatment studies of aftercare, including psy¬ worker with the patient, and taking 30 to 45 minutes, is

chotherapy. The scale has broad coverage of roles and in¬ used. The rater is required to make judgment of the pa¬

cludes both instrumental and affective performance. tient's performance in relation to the patient's peer group

Items included present a mixture of lifelong character- and the general population. The time period assessed is

iological behavior and measures of current behavior dur¬ "today" or "the past week." Reliability and validity data,

ing the past year, making it potentially less sensitive for a scoring system, results of factor analysis, a manual, and

evaluative research. instructional material are available.

9. The Social Disability Scale.53-55—This scale assesses The scale is currently being used in studies involving

the patient's physical and behavioral impairments, social schizophrenic, alcoholic, and drug-addicted patients, and

modifiers, qualifications and performances demanded has been used with older subjects. It is brief and well-

from others, and the tolerance limits of the social system. suited to aged populations for whom major role function¬

Forty-nine areas are assessed, including 37 areas of physi¬ ing may be absent. Marital, parental, or extended family

cal and seven areas of behavioral impairments, and five role functioning are not covered individually. Recreational

areas of social modification. The number of response and occupational roles are covered under the performance

points vary and are well-defined. Information is collected system. The self and interpersonal items include symptom

by semistructured interview with the patient, lasting 45 assessments. Response points are global and the questions

to 90 minutes, and conducted by a trained professional or require a skilled interviewer.

paraprofessional. Data on reliability, validity, sensitivity 11. Psychiatric Status Schedule (PSS):

to change, a scoring system, and instructional material for 12. Psychiatric Evaluation Form (PEF):

training are available. The time period assessed is "now." 13. Current and Past Psychopathology Scales (CAPPS).61"70

Downloaded from www.archgenpsychiatry.com at Columbia University, on May 24, 2010

—These three scales will be discussed together, since they reliability and validity are available.

were developed by the same research group and overlap in .As a social adjustment assessment, per se, the scales

conceptualization and item content. See Table 2 for a com¬ have minor limitations. The role areas comprise only a

parison of their content and administration. portion of the scale. The PSS does assess discrete aspects

The PSS assesses symptoms and impairments in daily of role performance and includes both instrumental and

routine, leisure time, alcohol and drug use, and role func¬ affective functioning within roles. However, the PEF and

tioning as wage earner, housekeeper, student, mate, and CAPPS do not differentiate instrumental and affective

parent. Three hundred twenty-one discrete descriptions of performance.

behavior are rated on a dichotomous scale. Information is These three scales commendable. The work is de¬

are

collected from the patient during a structured interview tailed, highly developed, and widely used. Each scale com¬

administered by a trained research assistant, taking 30 to bines in one instrument measures of psychopathology and

50 minutes to complete. The time period assessed is the social adjustment. The choice of one over the other de¬

last week, except for items dealing with role functioning, pends on the time available and amount of precision re¬

and alcohol and drug use, for which the last month is as¬ quired. The PSS is more precise, structured, and reliable.

sessed. A 21-page booklet includes the interview guide, The PEF generally takes less time to administer, but is

and score sheets are used. Computer programs and train¬ suitable for experienced clinicians. It might be used in

ing guides are available. Data on reliability, validity, and situations in which the information is already available

results of factor analysis are available. The instrument is because the rater knows the patient or has extensive

sensitive to clinical changes and has been widely used in a records. The CAPPS has the unique feature of providing

variety of settings and diagnostic groups. historical information.

The PEF includes assessments of the same symptoms, 14. Structured and Scaled Interview to Assess Malad¬

impairments, and role functioning as the PSS. However, justment (SSIAM).71-74—This scale assesses subjective dis¬

the areas are assessed as broad dimensions of behavior tress, deviant behavior, and friction with others in five

rather than as individually defined components. Defini¬ roles: work (worker, housewife, or student), social, family,

tions of the dimensions are included to assist the rater. marital, and sex. Objective behavior in a given social con¬

Twenty-seven items are rated on a 6-point global scale, text and subjective reactions in that context are included.

ranging from "none" to "extreme." The time period as¬ Raters' global assessments and a general prognostic mea¬

sessed is the same as the PSS. Information is usually lim¬ surement are made. Sixty items are rated on an 11-point

ited to that obtained during a structured interview with scale with anchoring definitions for five of the 11 points.

the patient, although other sources, such as informants or Information is collected during a structured interview

case records, can be used. An optional interview guide is with the patient, conducted by a trained professional with

provided; however, the interview can be altered. The in¬ clinical experience, taking about 30 minutes to administer.

terview takes 30 to 50 minutes. The flexible source of Specific instructions for the structuring of the interview

information and optional interview methods require a are printed on the interview schedule. The time period as¬

skilled rater with a range of clinical experience, as com¬ sessed varies, but "the past month" is the most usual. Reli¬

pared with the PSS. A nine-page step-down booklet and ability, validity, scoring, results of factor analysis, and in¬

precoded score sheet, training guide, and computer pro¬ structional material are available. The current form is not

gram are available. As with the PSS, extensive reliability precoded. The scale has been used in an outpatient psycho¬

and validity data are available. Factor scores have been therapy study.

calculated and the form currently is being widely used. This is one of the few structured social adjustment in¬

Both the PSS and the PEF take the occupational, mate, terviews. The interview structuring, anchoring defini¬

and parent role scales and derive a summary index of role tions, and guiding explanations reduce ambiguity and

functioning that has been found reliable and useful. This provide precision. The items are well thought out, and op-

index permits a comparison of individuals who perform erationalize aspects of behavior in a detailed fashion. The

different roles. coverage is broad and areas are tapped that are partic¬

The CAPPS is similar to the PEF in item content and ularly relevant to outpatient populations. The specificity

coverage and includes additional historical items relèvent of maladjustment into five fields, and further into three

to severity, prognosis, and diagnosis. It was developed as areas, allows examination of different aspects of function¬

a basis for a computerized diagnosis, including dimensions ing.

of disturbance. One hundred seventy-one broadly defined The scale was designed as an outcome measure for psy¬

items with guiding definitions are rated on a 6-point glo¬ chotherapy and, as such, the quantitative or instrumental

bal scale. The time period assessed is the past month for aspects of behavior have less coverage and may require

the current scales, and age 12 years to the last month for supplementation. These limitations are minor and this

the past scales. As in the PEF, the information is usually scale has much to recommend it.

limited to that obtained during a structured interview of 15. The Social Adjustment Scale (SAS).75-79-Instrumen-

the patient, but other sources may be used. Similar to the tal and affective performance in work (worker, housewife,

PEF, there is an optional interview guide. The interview or student), social and leisure activities, relationships with

takes one to two hours if the guide is used. A clinically ex¬ extended family, marriage (as a parent), economic inde¬

perienced rater, as with the PEF, is required. A 13-page pendence, and rater global evaluations are assessed. Each

protocol with a 26-page interview schedule, precoded score role area includes assessments of performance at tasks,

sheets, computer program, a training manual, and data on interpersonal relations, friction, and satisfaction in roles.

Downloaded from www.archgenpsychiatry.com at Columbia University, on May 24, 2010

The scale is modified from the SSIAM previously de¬ References

scribed. The core of items has been revised and anchor

points for scoring have been changed. However, many of 1. Bonjean CM, Jill RJ, McLemore SD (eds): Sociological Mea-

the items are directly comparable. surement: An Inventory of Scales and Indices. San Francisco,

Chandler Publishing Co, 1967.

Forty-eight operationally defined items are rated on a 2. Buros OK (ed): Mental Measurements Yearbook. Highland

5-point scale. Information is obtained through a semi- Park, NJ, Gryphon Press, 1965.

structured interview with the patient, taking 45 to 60 3. Chun KT, Cobb S, French JRP: Measures for Psychological

Assessment: A Guide to 3,000 Original Sources and Their Appli-

minutes and conducted by a trained bachelor's degree- cations. Ann Arbor, Mich, Institute for Social Research, Univer-

level rater. Initial questions are specified on the interview sity of Michigan, 1973.

4. Comrey AL, Backer TE, Glaser E: A Source Book for Mental

format. A two-month period is assessed. Data on reliabil¬ Health Measures. Los Angeles, Human Interactions Research In-

ity, validity, sensitivity, scoring, results of factor analysis, stitute, 1973.

5. Dent JK (ed): A Bibliographic Index of Evaluation in Mental

instructional material, and a manual are available. The Health, No. 1545. Washington, DC, National Institutes of Health,

scoring sheet is precoded. Public Health Services, 1966.

The scale was designed for a prophylactic trial of anti¬ 6. Hargreaves WA, McIntyre MH, Attkisson CC, et al: Outcome

measurement instruments for use in community mental health

depressants and psychotherapy in outpatient women. It program evaluation, in Hargreaves WA, Attkisson CC, Siegel LM,

has been used with nonpsychiatric populations and suicide et al (eds): Resource Materials for Community Mental Health

attempters, and is currently being used with methadone- Program Evaluation: Part IV. Evaluating the Effectiveness of

Services. San Francisco, National Institute of Mental Health,

maintained patients. A self-report version is being tested. 1974.

Coverage is broad, both in roles and in instrumental and 7. Lyerly SB: Handbook of Psychiatric Rating Scales, ed 2.

affective performance. The scale has not been used with a Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1973.

8. National Institute of Mental Health: Pharmacotherapy of

variety of psychiatric diagnoses and its use with male pa¬ children. Psychopharmacol Bull (special issue), 1973.

tients is not available yet, so that its value in a range of 9. Readings: Tests and Reviews\p=m-\Includinga Classified Index

circumstances has not been tested. of Mental Measurements Yearbook. Highland Park, NJ, Gryphon

Press, 1965.

10. Salzman C, Kochansky GE, Shader RI: Rating scales for

COMMENT geriatric psychopharmacology\p=m-\Areview. Psychopharmacol Bull

8:3-50, 1972.

Fifteen social adjustment scales, which met certain cri¬ 11. Strauss MA (ed): Family Measurement Techniques: Ab-

stracts of Published Instruments 1935-1965. Minneapolis, Univer-

teria, have been described. Others that are quite promis¬ sity of Minnesota Press, 1969.

ing are under development. For example, J. R. Witten- 12. Waskow IE, Parloff MB (eds): Psychotherapy Change Mea-

born, PhD, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, will sures: Report of the Clinical Research Branch, N.I.M.H. Outcome

soon be reporting results of a new social adjustment scale

Measures Project. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Of-

fice, 1974.

he developed and used to investigate the status of de¬ 13. Prusoff BA, Klerman GL, Paykel ES: Pitfalls in the self re-

pressed patients after treatment. Cohler et al8" have re¬ port assessment of depression. Can Psychiatr Assoc J 17:101-107,

1972.

cently reported results of role adjustment in mothers hos¬ 14. Spitzer RL, Endicott JE: The value of the interview for the

pitalized for psychiatric illnesses, using a measure of evaluation of psychopathology, in Hammer J, Salzinger K, Sutton

social relationships, the Social Role Performance Instru¬ S (eds): Psychopathology: Contributions in the Biological, Behav-

ioral and Social Sciences. New York, John Wiley & Sons Inc, 1973,

ment (SRPI) that was developed by their group. More new pp 397-408.

techniques can be expected as interest in this area grows. 15. Hogarty G: Informant rating of community adjustment, in

Waskow IE, Parloff MB (eds): Psychotherapy Change Measures:

Of the 15 scales reported here, three have been presented

for their historical import rather than their current use,

Report of Clinical Research Branch, N.I.M.H. Outcome Measures

Project. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1974.

leaving the researcher with 12 scales from which to make 16. Berger DG, Rice CE, Sewall LG, et al: Factors affecting the

a selection. This selection for a particular study can be adequacy of patients' community adjustment information ob-

tained. Ment Hyg 47:452-460, 1963.

narrowed down further after decisions are made about in¬ 17. Deykin EY, Weissman MM, Klerman GL: Treatment of de-

formant, source of information, cost, and content. No deci¬ pressed women: Therapeutic issues with hospitalized patients and

sion will be without compromise. Although there is consid¬ outpatients. Br J Soc Work 1:277-291, 1971.

18. Clausen GT: Some problems of design and inference in stud-

erable room for scale development, and none of the scales ies of community tenure. J Nerv Ment Dis 155:22-35, 1972.

19. Lyerly SB, Abbot PS (eds): Handbook of Psychiatric Rating

presented will stand as the final instrument, there is also a Scales, 1950-1964. Bethesda, Md, National Institute of Mental

strong need for standardization of methods between stud¬ Health, Public Health Services, 1965.

ies. A compromise should be reached between the toler¬ 20. Barrabee R, Barrabee EL, Finesinger JEF: A normative so-

ance of those evaluated, the creative instincts of those

cial adjustment scale. Am J Psychiatry 112:252-259, 1955.

21. Miles HHW, Barrabee EL, Finesinger JEF: Evaluation of

evaluating, and the need for standardization. It might be psychotherapy. Psychosom Med 13:83-105, 1951.

best to include intact a standard and widely used scale 22. Miles HHW, Waldfogel S, Barrabee EL, et al: Psychoso-

matic study of 46 young men with coronary artery disease.

and to supplement with innovations. In this way the art of Psychosom Med 16:455-477, 1954.

assessments will not atrophy but information based on 23. Frank JD: Problems of controls in psychotherapy as exem-

comparative data from a number of studies can accumu¬ plified by the psychotherapy research project of the Phillips Psy-

chiatric Clinic, in Rubenstein E, Parloff ME (eds): Research in

late. Psychotherapy. Washington, DC, American Psychological Associa-

tion 1958.

24. Frank JD, Gliedman LH, Imber SD, et al: Patients' expect-

This investigation was supported in part by contract FDA 73-9 to the ancies and relearning as factors determining improvement in

American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry 115:961-968, 1959.

J. R. Wittenborn, PhD, was principal investigator and Gerald L. Kler¬ 25. Imber SD, Frank JD, Nash EH, et al: Improvement and

man, MD, was chairman for the committee on the evaluation of anti¬ amount of therapeutic contact: An alternative to the use of the no-

depressants. Elmer Gardner, MD, and Barrett Scoville, MD, of the FDA treatment controls in psychotherapy. J Consult Psychol 21:309-

supported this study and allowed the publishing of this report. 315, 1957.

Downloaded from www.archgenpsychiatry.com at Columbia University, on May 24, 2010

26. Parloff MB, Kelman HC, Frank JD: Comfort, effectiveness 54. Ruesch J: The assessment of social disability. Arch Gen

and self-awareness as criteria of improvement in psychotherapy. Psychiatry 21:655-664, 1969.

Am J Psychiatry 111:343-351, 1954. 55. Ruesch J, Sabine J, Peterson HW, et al: The measurement

27. Gilberstadt H, Aberwald R, Crosbie S, et al: Effect of sur- of social disability. Compr Psychiatry 13:507-518, 1972.

gery on psychological and social functioning in elderly patients. 56. Goodman SP, Schulthorpe WB, Evje M, et al: Social dys-

Arch Intern Med 122:109-115, 1968. function in psychiatric and medical outpatients. Abstract Gerontol

28. Gilberstadt H: Relationships among scores of tests suitable 8:39, 1968.

for the assessment of adjustment and intellectual functioning. J 57. Goodman SP, Schulthorpe WB, Evje M, et al: Social dys-

Gerontology 23:483-487, 1968. function among psychiatric and nonpsychiatric outpatients. J Am

29. Mandel NG: Mandel Social Adjustment Scale. Minneapolis, Geriatr Soc 17:697-700, 1969.

University of Minnesota, 1959. 58. Greenwald SR, Carter JS: Differences between the back-

30. Mandel NG: An Evaluation of the Sociological, Psychological ground, mood, attitude and functioning of drug addicts, alcoholics

and Physiological Post-Hospital Adjustment of Mental Patients and orthopedic patients. Read before the second International

Treated With Intensive Electric Shock Therapy, doctoral dis- Symposium on Drug Abuse, Jerusalem, Israel, 1972.

sertation. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota, 1960. 59. Linn MW, Schulthorpe WB, Evje M, et al: A social dysfunc-

31. Berger DG, Rice CE, Sewall LG, et al: Factors affecting the tion rating scale. J Psychiatr Res 6:299-316, 1969.

adequacy of patients' community adjustment information ob- 60. Linn MW: Perceptions of childhood and social dysfunction

tained from the community. Ment Hyg 47:452-460, 1963. in aging. Read before the annual meeting of the American Socio-

32. Berger DG, Rice CE, Sewall LG, et al: The post-hospital logical Association, New Orleans, 1972.

evaluation of psychiatric patients: The social adjustment inven- 61. Spitzer RL, Cohen G, Miller J, et al: The psychiatric status

tory method. Psychiatr Stud Proj 2:1-30, 1964. of 100 men on Skid Row. Int J Soc Psychiatry 15:230-234, 1967.

33. Berger DG, Rice CE, Sewall LG, et al: The impact of psy- 62. Spitzer RL, Endicott J: DIAGNO: A computer program for

chiatric hospital experience on the community adjustment of pa- psychiatric diagnosis utilizing the differential diagnostic proce-

tients. Mental Hyg 49:83-92, 1965. dure. Arch Gen Psychiatry 18:746-756, 1968.

34. Langsley DG, Pittman FS, Machotka P, et al: Family crisis 63. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Fleiss JL, et al: The psychiatric

therapy-Results and implications. Family Proc 7:145-158, 1968. status schedule: A technique for evaluating psychopathology and

35. Rice CE, Berger DG, Sewall LG, et al: Measuring social res- impairment in role functioning. Arch Gen Psychiatry 23:41-55,

toration performance of public psychiatric hospitals. Pub Health 1970.

Rep 76:437-446, 1961. 64. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: What! Another rating scale? The

36. Ellsworth RB, Clayton W: Measurement of improvement in psychiatric evaluation form. J Nerv Ment Dis 154:88-104, 1972.

mental illness. J Consult Psychol 23:15-20, 1959. 65. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: Current and past psychopathology

37. Ellsworth RB, Foster L, Childres B, et al: Hospital and com- scales (CAPPS): Rationale, reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psy-

munity adjustment as perceived by psychiatric patients, their chiatry 27:678-687, 1972.

family and staff. J Consult Clin Psychol 32:(pt 2):1-41, 1968. 66. Fleiss JL, Spitzer RL, Burdock EI: Estimating accuracy of

38. Ellsworth RB: Evaluating and applying information about judgment using recorded interviews. Arch Gen Psychiatry 12:562-

treatment outcome. Hosp Comm Psychiatry 21:115-117, 1970. 567, 1965.

39. Ellsworth RB: Consumer feedback in measuring the effec- 67. Melrose JP: Diagnosis of psychopathology using stepwise

tiveness of mental health programs, in Guttenlay P, Struening M multiple discriminant analysis: I. Compr Psychiatry 11:43-50,

(eds): Handbook of Evaluation Research, to be published. 1970.

40. Hogarty GE, Katz MM, Lowery HA: Identifying candidates 68. Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Burdock EI, et al: The mental status

from a normal population for a community mental health pro- schedule: Rationale, reliability, validity. Compr Psychiatry 5:384-

gram, in Monroe RR, Klee GD, Brody EB (eds): Psychiatric Re- 395, 1964.

search Report No. 22. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric As- 69. Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Endicott J, et al: Mental status sched-

sociation, 1967, pp 219-234. ule: Properties of factor-analytically derived scales. Arch Gen

41. Hogarty GE, Katz MM: Norms of adjustment and social be- Psychiatry 16:479-493, 1967.

havior. Arch Gen Psychiatry 25:470-480, 1971. 70. Spitzer RL, Endicott J: DIAGNO II: Further developments

42. Katz MM, Lyerly SB: Methods of measuring adjustment in a computer program for psychiatric diagnosis. Am J Psychia-

and social behavior in the community: I. Rationale, description, try 125:12-21, 1969.

discriminative validity and scale development. Psychol Rep 13:503- 71. Candy J, Balfour FHG, Cawley RH, et al: A feasibility

535, 1963. study for a controlled trial for formal psychotherapy. Psychol Med

43. Katz MM: A typological approach to the problem of pre- 2:345-362, 1972.

dicting response to treatment, in Wittenborn JR, May PRA (eds): 72. Gurland BJ, Yorkston NJ, Stone AR, et al: The structured

Prediction of Response to Pharmacotherapy. Springfield, Ill, and scaled interview to assess maladjustment (SSIAM): I. De-

Charles C Thomas Publisher, 1966, pp 85-101. scription, rationale, and development. Arch Gen Psychiatry

44. Katz MM, Lowery HA, Cole JO: Behavior patterns of schiz- 27:259-264, 1972.

ophrenia in the community, in Lorr M (ed): Explorations in Typ- 73. Gurland BJ, Yorkston NJ, Goldberg K, et al: The structured

ing Psychotics. New York, Pergamon Press Inc, 1966, pp 209-230. and scaled interview to assess maladjustment (SSIAM): II. Factor

45. Katz MM, Gudeman H, Sanborn K: Characterizing differ- analysis, reliability, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 27:264-267,

ences in psychopathology among ethnic groups: A preliminary re- 1972.

port on Hawaiian-Japanese and mainland-American schizophrenics, 74. Hoehn-Saric R, Liberman B, Imber S, et al: Arousal and at-

in Caudill W, Lin T (eds): Mental Health Research in Asia and titude change in neurotic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 26:51-56,

the Pacific. Honolulu, East-West Center Press, 1969, pp 103-115. 1972.

46. Clark AW: Conditions influencing patient response to treat- 75. Paykel ES, Weissman MM, Prusoff BA, et al: Dimensions of

ment in a therapeutic community. Soc Sci Med 1:309-319, 1967. social adjustment. J Nerv Ment Dis 152:158-172, 1971.

47. Clark AW: The personality and social network adjustment 76. Paykel ES, Klerman GL, DiMascio A, et al: Maintenance an-

scale. Hum Rel 21:85-96, 1968. tidepressants, psychotherapy, symptoms and social function, in

48. Clark AW, Yeomans NT: Fraser House: Theory, Practice Cole JO, Friedhoff A, Freedman A (eds): Psychopathology and

and Evaluation of a Therapeutic Community. New York, Springer Psychopharmacology. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press,

Publishing Co, 1969, pp 275-276. 1973, pp 205-218.

49. Burnes AJ, Rosen SR: Social roles and adaptation to the 77. Weissman MM, Paykel ES, Siegel R, et al: The social role

community. Community Ment Health J 3:153-158, 1967. performance of depressed women: Comparisons with a normal

50. Cook P, Josephs P: The community adaptation schedule and group. Am J Orthopsychiatry 41:390-405, 1971.

the California psychological inventory: A validational study with 78. Weissman MM, Klerman GL, Paykel ES, et al: Treatment

college students. Community Ment Health J 6:366-370, 1970. effects on the social adjustment of depressed patients. Arch Gen

51. Roen SR, Ottenstein D, Cooper S, et al: Community adapta- Psychiatry 30:771-778, 1974.

tion as an evaluative concept in community mental health. Arch 79. Weissman MM, Paykel ES: The Depressed Woman: A Study

Gen Psychiatry 15:36-44, 1966. of Social Relationships. Chicago, University of Chicago Press,

52. Roen SR, Burnes AJ: Community Adaptation Schedule Pre- 1974.

liminary Manual. New York, Behavioral Publications Inc, 1968. 80. Cohler BJ, Grunebaum HU, Weiss JL, et al: Social relations,

53. Ruesch J, Brodsky CM: The concept of social disability. stress and psychiatric hospitalization among mothers of young

Arch Gen Psychiatry 19:394-403, 1968. children. Soc Psychiatry 9:7-12, 1974.

Downloaded from www.archgenpsychiatry.com at Columbia University, on May 24, 2010

View publication stats

Вам также может понравиться

- The Assessment of Social Adjustment: A Review of Techniques: Archives of General Psychiatry April 1975Документ10 страницThe Assessment of Social Adjustment: A Review of Techniques: Archives of General Psychiatry April 1975THAKKAR NISHI HITESH SHEETAL 21MPS037Оценок пока нет

- Using Psychology to Promote Human Welfare: A Conceptual Analysis of Community Psychology ApproachesДокумент11 страницUsing Psychology to Promote Human Welfare: A Conceptual Analysis of Community Psychology ApproachesFernando BarraОценок пока нет

- Clinical Psych Specialization IntroductionДокумент7 страницClinical Psych Specialization IntroductionAlmira BartolomeОценок пока нет

- Mind Magic: Building a Foundation for Emotional Well-BeingОт EverandMind Magic: Building a Foundation for Emotional Well-BeingОценок пока нет

- 507 - Clinical Assessment and Diagnosis - Spg19 - Master Syllabus Gina S Otg 0Документ38 страниц507 - Clinical Assessment and Diagnosis - Spg19 - Master Syllabus Gina S Otg 0Ririf NoviyantoОценок пока нет

- TrabajoДокумент14 страницTrabajoOsmely PiñaОценок пока нет

- Spiritual Assessment in Social Work and Mental Health PracticeОт EverandSpiritual Assessment in Social Work and Mental Health PracticeОценок пока нет

- Nock Prinstein JCCP2004Документ6 страницNock Prinstein JCCP2004ICGusonОценок пока нет

- Ccoryn, Journal Editor, AllerДокумент17 страницCcoryn, Journal Editor, AllerKayu LowОценок пока нет

- Myers 2002Документ9 страницMyers 2002Umi KulsumОценок пока нет

- Assessing Child Behavior with Focal AssessmentДокумент18 страницAssessing Child Behavior with Focal AssessmentFaten SalahОценок пока нет

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Overview of Behavioral and Mental Disorders in PsychologyОт EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Overview of Behavioral and Mental Disorders in PsychologyОценок пока нет

- PSW Psychosocial Assessment MainДокумент4 страницыPSW Psychosocial Assessment MaintintuОценок пока нет

- Tests SsДокумент14 страницTests SsjvtoselaОценок пока нет

- Development and Psychometric Properties of The Mental Health Knowledge ScheduleДокумент9 страницDevelopment and Psychometric Properties of The Mental Health Knowledge ScheduleJovana AntonijevićОценок пока нет

- A Scientific Approach To Your Research: Sample Chapter From Conducting Your Pharmacy Practice Research ProjectДокумент18 страницA Scientific Approach To Your Research: Sample Chapter From Conducting Your Pharmacy Practice Research ProjectKrisel IbanezОценок пока нет

- Art - Depression and Somatization A Review - Part II.1982Документ7 страницArt - Depression and Somatization A Review - Part II.1982Shadia NaLaОценок пока нет

- Precision mental health advances through "third-waveДокумент13 страницPrecision mental health advances through "third-waveKhaled AbdelNaserОценок пока нет

- lau2021Документ12 страницlau2021Kevin LunaОценок пока нет

- A Review On Ethical Issues and Rules in Psychological AssessmentДокумент14 страницA Review On Ethical Issues and Rules in Psychological AssessmentJoshua MendezОценок пока нет

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Mental Disorders: An IntroductionОт EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Mental Disorders: An IntroductionОценок пока нет

- Measuring Social Inclusion in Global Mental HealthДокумент11 страницMeasuring Social Inclusion in Global Mental HealthBernadette TaripeОценок пока нет

- Sociocultural PerspectiveДокумент11 страницSociocultural PerspectiveadeshОценок пока нет

- Foundations of Professional Psychology: The End of Theoretical Orientations and the Emergence of the Biopsychosocial ApproachОт EverandFoundations of Professional Psychology: The End of Theoretical Orientations and the Emergence of the Biopsychosocial ApproachОценок пока нет

- The Psychosocial Adjustment To Illness Scale (Pais) : DerogatisДокумент15 страницThe Psychosocial Adjustment To Illness Scale (Pais) : DerogatisM.Fakhrul KurniaОценок пока нет

- Conducting 2e SampleДокумент18 страницConducting 2e SampleIbn Hamz El-SalamyОценок пока нет

- Dimensional PsychopathologyОт EverandDimensional PsychopathologyMassimo BiondiОценок пока нет

- Abraham & Sheeran - The Health Belief ModelДокумент45 страницAbraham & Sheeran - The Health Belief ModelAmalia Dwi AryantiОценок пока нет

- Time For A Paradigm ShiftДокумент6 страницTime For A Paradigm ShiftDavid GarcíaОценок пока нет

- Cognitive BehavioralTherapyДокумент12 страницCognitive BehavioralTherapyJulian PintosОценок пока нет

- Effect of Psychosocial Interventions On Social Functioning in Depression and Schizophrenia: Meta-AnalysisДокумент37 страницEffect of Psychosocial Interventions On Social Functioning in Depression and Schizophrenia: Meta-AnalysiswardahОценок пока нет

- Fpsyt 14 1148170Документ10 страницFpsyt 14 1148170Alexa Ramírez ContrerasОценок пока нет

- Managing Madness in the Community: The Challenge of Contemporary Mental Health CareОт EverandManaging Madness in the Community: The Challenge of Contemporary Mental Health CareОценок пока нет

- An Object-Relations Based Model For The Assessment of Borderline PsychopathologyДокумент17 страницAn Object-Relations Based Model For The Assessment of Borderline Psychopathologyracm89Оценок пока нет

- Construction of Mental IllnessДокумент7 страницConstruction of Mental IllnessKristin OnetoОценок пока нет

- Original Article Psychological Status And: Coping Strategy of Somatization DisordersДокумент5 страницOriginal Article Psychological Status And: Coping Strategy of Somatization DisordersityОценок пока нет

- Annual Review of Addictions and Offender Counseling II: Best PracticesОт EverandAnnual Review of Addictions and Offender Counseling II: Best PracticesОценок пока нет

- Interpersonal Mechanisms Linking Close Relationships To HealthДокумент12 страницInterpersonal Mechanisms Linking Close Relationships To HealthFrancisco MartinezОценок пока нет

- 006 Chapter 4 Clinical AssessmentДокумент12 страниц006 Chapter 4 Clinical AssessmentMary Ann Bautista PerladoОценок пока нет

- Psychological Perspectives Poverty Full - 0Документ46 страницPsychological Perspectives Poverty Full - 0Parthiban S. GopalОценок пока нет

- Running Head: Effectiveness of Dementia Inteventions 1Документ12 страницRunning Head: Effectiveness of Dementia Inteventions 1John Mureithi NjugunaОценок пока нет

- Lay Beliefs About Treatments For People With Mental Illness and Their Implications For Antistigma StrategiesДокумент8 страницLay Beliefs About Treatments For People With Mental Illness and Their Implications For Antistigma Strategiesshah khalidОценок пока нет

- Recovery From Schizophrenia in Community-Based Psychosocial Rehabilitation Settings Rates and PredictorsДокумент15 страницRecovery From Schizophrenia in Community-Based Psychosocial Rehabilitation Settings Rates and Predictorstitik dyahОценок пока нет

- The Role of Positive Emotion and Contributions of Positive Psychology inДокумент17 страницThe Role of Positive Emotion and Contributions of Positive Psychology ine orlando mocaОценок пока нет

- C9a1 PDFДокумент12 страницC9a1 PDFfujfrОценок пока нет

- Teaching FCC To Psych - FullДокумент9 страницTeaching FCC To Psych - FullStgo NdОценок пока нет

- Running Head: Effectiveness of Dementia Inteventions 1Документ17 страницRunning Head: Effectiveness of Dementia Inteventions 1John Mureithi NjugunaОценок пока нет

- 2 - Methodical Guidelines For StudentsДокумент7 страниц2 - Methodical Guidelines For StudentsUkraineОценок пока нет

- Community Mental Health 2239411Документ8 страницCommunity Mental Health 2239411Arshia RoyОценок пока нет

- 1 Clinical InterviewДокумент14 страниц1 Clinical InterviewClara Del Castillo ParísОценок пока нет

- Exploring The Complexities of Personality Disorders Unravelling The Inner Workings of The MindДокумент11 страницExploring The Complexities of Personality Disorders Unravelling The Inner Workings of The Mindrosedragomir200727Оценок пока нет

- Testing The Short and Screener Versions of The Social Adjustment Scale - Self-Report (SAS-SR)Документ22 страницыTesting The Short and Screener Versions of The Social Adjustment Scale - Self-Report (SAS-SR)Swagata DeyОценок пока нет

- Comer 2013Документ11 страницComer 2013somya mathurОценок пока нет

- Mental HealthДокумент11 страницMental Healthmahmoodosman91Оценок пока нет

- 243 1403 1 PBДокумент8 страниц243 1403 1 PBRirin SriHandayaniОценок пока нет

- Data Collection Sem OldДокумент62 страницыData Collection Sem OldAmy Lalringhluani ChhakchhuakОценок пока нет

- HR PLANNING KEY STEPSДокумент20 страницHR PLANNING KEY STEPSNrityam NundlallОценок пока нет

- Marketing Strategies of Furniture Shops in Angeles CityДокумент18 страницMarketing Strategies of Furniture Shops in Angeles CityCARL JAMESОценок пока нет

- A Validation Study of The Thinking Styles InventoryДокумент17 страницA Validation Study of The Thinking Styles InventorybuccomanОценок пока нет

- Reasoning Tests Technical ManualДокумент78 страницReasoning Tests Technical Manualm.roseОценок пока нет

- Sampling Design, Sample Size, and Their Importance Prof Bhisma Murti PDFДокумент23 страницыSampling Design, Sample Size, and Their Importance Prof Bhisma Murti PDFevifebrikaОценок пока нет

- MA 210 ReviewerДокумент11 страницMA 210 ReviewerMARY JOSEPH E. OCOОценок пока нет

- CORE104 W10S1 CriticalReviewWorkshopДокумент47 страницCORE104 W10S1 CriticalReviewWorkshopKoha TrầnОценок пока нет

- A Self Image Questionnare For Young AdolecentsДокумент19 страницA Self Image Questionnare For Young AdolecentsLeonny MadelineОценок пока нет

- A Profile and Training Framework of Vip ProtectorДокумент18 страницA Profile and Training Framework of Vip ProtectorGatot Teguh Imanto100% (2)

- Prin of High-Q Classroom Assess ModuleДокумент4 страницыPrin of High-Q Classroom Assess ModuleRellan YbanezОценок пока нет

- ignou Guru: AssignmentДокумент13 страницignou Guru: AssignmentAshwini Tyagi100% (1)

- Cloud HypothesisДокумент17 страницCloud HypothesisrahulbwОценок пока нет

- Rammstedt Et Al 2022 Measuring Growth MindsetДокумент12 страницRammstedt Et Al 2022 Measuring Growth Mindsetwakijo wakijoОценок пока нет

- 04 ROLE OF READ FOUNDATION IN PROMOTION VikyДокумент7 страниц04 ROLE OF READ FOUNDATION IN PROMOTION VikyMuhammad EhsaanОценок пока нет

- Ajzen - Fishbein - Attitude Handbook 2005Документ50 страницAjzen - Fishbein - Attitude Handbook 2005Gabriellla022Оценок пока нет

- Development and Initial Standardization of Ayurveda Child Personality InventoryДокумент4 страницыDevelopment and Initial Standardization of Ayurveda Child Personality InventoryJaqueline TodescatoОценок пока нет

- Psychometric Properties of A Structured Diagnostic Interview For DSM-5 Anxiety, Mood, and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related DisordersДокумент11 страницPsychometric Properties of A Structured Diagnostic Interview For DSM-5 Anxiety, Mood, and Obsessive-Compulsive and Related DisordersFeras ZidiОценок пока нет

- CBRC ANALYTICAL FINAL COACHINGДокумент24 страницыCBRC ANALYTICAL FINAL COACHINGJoy Navales100% (3)

- Science+Education+Students+Perceptions+of+Single-Parenting+Impacts+on+Science+Learning+-+AJHCER March 2022 Vol3 No2Документ11 страницScience+Education+Students+Perceptions+of+Single-Parenting+Impacts+on+Science+Learning+-+AJHCER March 2022 Vol3 No2Ellaissa Hanna AlbarracinОценок пока нет

- Commitment To Independence by Internal Auditors The Effects of Role Ambiguity and Role ConflictДокумент27 страницCommitment To Independence by Internal Auditors The Effects of Role Ambiguity and Role ConflictArfiraОценок пока нет

- Implementation of Total Quality Management in HospitalsДокумент6 страницImplementation of Total Quality Management in HospitalsAhmed Mashaly100% (1)

- Reynolds Adolescent Depression ScaleДокумент7 страницReynolds Adolescent Depression Scalecoco chanelОценок пока нет

- Astm E125Документ3 страницыAstm E125Ronald PacayaОценок пока нет

- 2015-Kock-Common Method Bias in Smart PLSДокумент10 страниц2015-Kock-Common Method Bias in Smart PLSAzmatIslamОценок пока нет

- Alternative Assessment EDU533Документ11 страницAlternative Assessment EDU533stephen talaman100% (2)

- ED 208 Assessment 1Документ41 страницаED 208 Assessment 1Allysa Marie Silbol100% (1)

- Defining Key Terms in Science Learning AssessmentДокумент10 страницDefining Key Terms in Science Learning AssessmentIzzuddin AzzmiОценок пока нет

- Psych ? Pre-Board Exam - 1Документ19 страницPsych ? Pre-Board Exam - 1sdfghОценок пока нет