Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

HN 06-2005 Botulinum Toxin Physiology

Загружено:

Khilyatul MufidaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

HN 06-2005 Botulinum Toxin Physiology

Загружено:

Khilyatul MufidaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

BOTULINUM TOXIN—PHYSIOLOGY AND APPLICATIONS IN

HEAD AND NECK DISORDERS

James Keir, MBChB

14 Stonelea Court, Meanwood, Leeds, Yorkshire LS7 2UH, United Kingdom.

E-mail: jameskeir@hotmail.com

Accepted 1 December 2004

Published online 16 May 2005 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/hed.20247

Abstract: This article is structured around a literature review Its use in facial dystonias improves the disfigure-

that was carried out using Ovid and Medline with the key words ment and the discomfort and disability associated

‘‘botulinum,’’ ‘‘toxin,’’ and ‘‘ENT.’’ Botulinum toxin has been used with the condition.3

safely in humans for more than 20 years. The effects are tran- The word ‘‘botulism,’’ which is the clinical syn-

sient, such that treatments are required to be repeated at

drome of botulinum toxin poisoning, comes from

intervals. Its application to ENT provides a useful tool to treat

dystonia, autonomic dysfunction, facial nerve paresis, and hy- the Greek word for sausage, botulus, because for a

perfunctional lines. It may also be of benefit in laryngeal re- long time it was used to refer to a particular ill-

balancing and the treatment of headaches. Further research is ness caused by the ingestion of spoiled sausages.

being carried out and new indications for treatment with Clostridium botulinum was first identified as a

botulinum toxin may include sialorrhea and rhinorrhea. A 2005

causative agent in food poisoning in 1895 by

Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Head Neck 27: 525 – 535, 2005

Professor Emile Pierre van Ermengem.4 He was

Keywords: Botulinum; toxin; ENT asked to investigate an episode of lethal food poi-

soning that arose because of the consumption of

A HISTORY OF BOTULINUM TOXIN uncooked ham at a wake. The symptoms demon-

The use of botulinum toxin for aesthetic purposes strated were of autonomous dysfunction (dryness

has become one of the most common cosmetic pro- of the mouth, nausea, paralytic ileus, postural

cedures performed today, and its use is a com- hypotension) and flaccid paralysis, all in the ab-

monly discussed topic in the media.1 It was first sence of fever. van Ermengem examined autopsy

developed as therapeutic agent for the treatment specimens, the spoiled meat, and its effect when

of disorders characterized by localized muscle fed to a series of animals.

hyperactivity, especially around the eyes. Botu- It was discovered in 1919 by Professor Burke

linum toxin is now widely used to treat many of Stanford University that there were different

conditions including most types of focal dystonia.2 strains of the bacterium and that they produced

serologically different types of botulinum toxin.5

He proposed an alphabetical classification and

Correspondence to: J. Keir identified two serotypes, types A and B, in his ex-

B 2005 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. periments. Further studies demonstrated another

Botulinum Toxin HEAD & NECK June 2005 525

five serotypes so that, to date, seven serotypes of

botulinum neurotoxin have been identified and

named A to G.2

A crude form of botulinum toxin type A was

isolated in the 1920s, and later the first attempts

at purification were made.6,7 During World War

II, the US government assigned a number of

scientists at Fort Detrick in Maryland to develop

protection against such agents. It was isolated by

this group in crystalline form in 1946, and initial

insights into the mechanism of action came when

it was shown to block the release of acetylcholine

from motor nerve endings.8,9

Botulinum toxin was first tested in animals in

the 1960s and 1970s by Dr. Alan Scott, who was

an ophthalmologist seeking an alternative or

adjunct to surgery for strabismus. He had come

into contact with Dr. Edward Schantz, a toxicol-

ogist who had participated in the work at Fort

Detrick. Its safety was shown in humans in 1980,

when the selective weakening of specific extra-

ocular muscles with intramuscular injections of

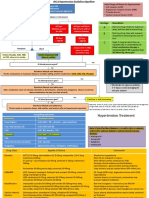

FIGURE 1. (A) Neurospecific binding of the toxin to its receptor

botulinum toxin type A could correct gaze mis- on the presynaptic membrane takes place. The toxin – receptor

alignment in strabismus.10,11 complex is then internalized by endocytosis. (B) Acidification of

Botulinum toxin type B is now commer- the vesicle by proton pumping ATPase leads to membrane

cially available, with research into the other sub- translocation of the light chain into the cytoplasm. Heavy chain is

shown in black, and the light chain in grey.

types awaited.

PHARMACOLOGY AND MECHANISM OF ACTION translocation is triggered by acidification of the

Botulinum neurotoxins are primarily inactive, vesicle lumen by a proton pumping ATPase,

polypeptide di chains of 150 kDa that are re- which leads to conformational change of the toxin.

leased during bacterial lysis and are cleaved by In its acid conformation, the toxin inserts into the

tissue proteases into heavy (100 kDa) and light lipid bilayer, and translocation of the light chain

(50 kDa) chains with different roles in nerve cell is promoted. The light chain is set free by

intoxication. After lysis, this generates an active reduction of the interchain disulfide bond and

di-chain neurotoxin composed of a heavy chain acts as a zinc-dependent metalloproteinase in-

and a light chain bridged by an interchain side the cell to prevent the release of vesicle-

disulfide bond.12 They are bound with nontoxic bound acetylcholine.12,14 The neurotoxins are

proteins to form a complex giving a total able to prevent release by disrupting peptides

molecular weight of approximately 900 kDa for necessary for docking and ultimately exocytosis

type A and 700 kDa for type B.13 of the acetylcholine-containing vesicle. In type

The intoxication occurs in four distinct steps A, the light chain cleaves SNAP-25, a 25-kDa

(which are shown in Figure 1): cell binding, inter- synaptosomal-associated protein, whereas the

nalization by means of endocytosis, membrane light chain of type B cleaves vesicle-associated

translocation, and catalyzation of the hydrolysis membrane protein (VAMP).15,16

of peptides. Little is known of the intracellular events af-

In types A and B, the heavy chain is re- ter type B use. However, the clinical effects of

sponsible for selective binding of the neurotoxin type A subside because of collateral sprouting

to receptors on the surface of the presynaptic of new nerve terminals occurring with time. With

membrane of cholinergic nerve cells. This is fol- time, the original functional endplate is re-

lowed by internalization inside vesicles by means established, and the sprouts regress.17

of endocytosis and membrane translocation of These differences in mechanism of action may

the light chain into the nerve cell cytoplasm. The explain variations in clinical performance. Type B

526 Botulinum Toxin HEAD & NECK June 2005

studies have shown that doses many times procedure. The toxin is drawn up in syringe and

greater than that of type A are required to treat injected with a 30-gauge needle at an angle of

those with the same indications. There are also 30 degrees. Anatomy is essential in choosing the

differences in the complication profile.18 – 23 site for injection, although some clinicians favor

the use of the electromyographic (EMG) needle.

This is connected to the EMG machine and

BOTULINUM TOXIN PRODUCTS ground and reference leads placed on the face or

Botulinum toxin type A is commercially available supraclavicular area. If the needle is in the ac-

as either Botox or Dysport, both of which are sold tive part of the muscle and the patient now

in a lyophilized form that must be reconstituted accentuates the specific facial expression that

with physiologic saline. Botox, which is manufac- produces the unwanted line, a burst of activity

tured by Allergan Inc. (Irvine, CA), is available will be heard on the speaker of the EMG. A dis-

internationally in 100 U per vial. It is shipped on tant signal (ie, one in which there is a low fre-

dry ice and should be stored in a freezer at 5jC. quency, dull sound) should provoke the needle

Dysport is manufactured by Ipsen Limited (Berk- being moved until the signal is maximal and the

shire, UK) and is primarily used in Europe, toxin then injected. After the injections, the pa-

because it is not licensed in the United States. tient should be asked not to massage the in-

It is distributed in 500-U vials and needs to be jected area for several hours to avoid diffusion to

stored at 2 to 8jC. Type B toxin is sold as Neu- adjacent muscles.26

robloc (or Myobloc in the United States), which is The clinical effect of botulinum toxin is dose

a premanufactured aqueous solution. It is dis- related. This allows treatment to be modified

tributed in 2500, 5000, or 10,000 U and is licensed according to the requirements of individual pa-

in the Unites States and several European tients. The dose required to produce a given

countries in the treatment of cervical dystonia. degree of denervation is related to the mass of the

For all the preceding products, doses are targeted muscle. There is no way to determine

determined by in vitro mouse assays in units of in advance the dose of botulinum toxin required

biologic activity (U). One unit is defined as the for therapeutic effect in a patient never treated

amount of neurotoxin complex protein that is before. The dose used also obviously is deter-

lethal in 50% of female, Swiss-Webster mice after mined by the particular clinical application it is

an intraperitoneal injection (mouse LD50). How- used for. The range of effective doses between

ever, differences in serotype, formulation, and patients for a given disorder may differ by several

the way lethality tests are performed between orders of magnitude.27

manufacturers means results in units that vary Improvement in symptoms usually occurs

greatly in their potency between the products. within 3 to 5 days, with clinical efficacy generally

This leads to marked differences in dosing. Doses seen within the first 7 to 10 days. The effect of

of Dysport can therefore be three to six times botulinum toxin begins to wear off 10 to 12 weeks

higher than the doses of Botox typically used to after injection.28

treat the same condition.24,25

COMPLICATIONS AND ADVERSE REACTIONS

ADMINISTERING BOTULINUM TOXIN Contraindications to the use of botulinum toxin

When administering the toxin, the physician include pregnancy or active breastfeeding, and it

should evaluate the patients with a thorough is relative contraindicated in pre-existing neu-

history and examination. A discussion of the romuscular conditions. Some medications, such

nature of the problem and the expected effect as aminoglycosides, penicillamine, quinine, and

should take place with informed consent ob- calcium channel blockers, can potentiate their

tained. If a cosmetic change is anticipated, pho- effect by interfering with neuromuscular trans-

tographs of the patient’s face at rest and activity mission and should not be used concomitantly

should be taken. The skin should be prepared with the treatment.29

and marked at the site for injection, which should The therapeutic use of botulinum toxin gen-

be recorded on a diagram in the patient’s medi- erally has been safe and well tolerated. Formation

cal records. A topical anaesthetic such as eutec- of antibodies may occur if the neurotoxins elicit an

tic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA) cream immune response. Although this is not a safety

may be used to decrease the discomfort of the concern, it may lead to a nonresponse of subse-

Botulinum Toxin HEAD & NECK June 2005 527

quent botulinum toxin injection by blocking the Autonomic Dysfunction. Frey’s syndrome and

therapeutic effects. Neutralizing antibodies de- hyperhydrosis (gustatory sweating and flushing

veloped against one serotype have not been re- on the cheek) is a well-described complication

ported to block the biologic activity of another of parotid gland surgery. It was first reported in

serotype.30 Prevalence of resistance is <5%31 and 1757 by Duphenix in a case secondary to trauma

is associated with dose and frequency of treat- but is most commonly seen after parotid gland

ments. To minimize the chance of resistance, the surgery. It has also been described after radical

smallest effective dose is used, and the interval neck dissection43 or submaxillary gland sur-

between treatments is extended for as long as pos- gery and may also occur after infection. The

sible to minimize exposure.32 This research, how- incidence of Frey’s syndrome after parotidectomy

ever, was based on old preparations that had an has been reported to be as high as 100% when a

increased protein load compared with the newer Minor’s starch test was used for diagnosis.44

toxin, which has reportedly less antigenicity. However, many of these are asymptomatic, with

Botulinum toxin may diffuse to nearby or only 30% being severely embarrassed by sweating

adjacent muscle, leading to adverse effects such after parotidectomy.43

as ptosis or drooling after facial injections.33 It The cause of the syndrome is thought to be

may also affect muscles distant from the site of misdirected regeneration of damaged axons.45

injection; a recent report documented three cases When the skin is raised during parotidectomy,

of generalized muscular weakness associated the postganglionic sympathetic fibers to the

with its use.34 Long-term use of botulinum toxin sweat glands in the flap are severed. Postgan-

causes reversible denervation atrophy in the glionic parasympathetic fibers from the auriculo-

muscles injected.35 Further research has demon- temporal branch of the mandibular nerve supply-

strated diminished size of type IIB fibers in ing the parotid gland are also severed when the

muscles distant from the injection site36 and salivary gland is removed. This allows cross-

abnormalities on EMG.37,38 innervation of the sweat glands by branches of

Generalized reactions that have idiosyncrati- the auriculotemporal nerve and consequently

cally occurred include nausea, fatigue, malaise, gustatory stimulation.46

flu-like symptoms, and rashes at sites distant Botulinum toxin, in addition to acting on

from the injection. Single-fiber electromyographic muscle, has an effect on cholinergic autonomic

weakness and changes in neuromuscular trans- nerve terminals.47 Both the parasympathetic

mission have been found in muscles distant to the nerves stimulating salivary gland secretion and

injection site. This is possibly due to a small the sympathetic fibers that cause sweating are

amount of toxin diffusing into the circulation.39,40 cholinergic autonomic fibers. Hence, the regener-

Untoward sequelae that may occur at any in- ation of axons may be misdirected, and botulinum

jection site include pain, edema, erythema, ecchy- toxin inhibits both salivation and sweating.

mosis, headache, and short-term hyperesthesia.41 Drobik and Laskawi48 first proposed treat-

In the 23 years that botulinum toxin has been ment of Frey’s syndrome with botulinum toxin

used in humans, there have been no reported injection in 1994 and presented a case with

deaths from an overdose. The estimated lethal 12 months’ follow-up in the following year. The

dose for a 70-kg human, based on primates, is methods described include identification of the

approximately 2800 U (40 U/kg).42 area for injection using Minor’s starch test. This

involves the application of a solution containing

iodine, ricine oil, and alcohol painted onto the

CLINICAL USES FOR BOTULINUM TOXIN affected cheek.49 The identified area is then

IN OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY marked and divided into small squares of approx-

In otorhinolaryngology, the use of botulinum imately 4 cm2. In each square, 2.5 U of botulinum

toxin is rapidly expanding. This includes the toxin type A (Botox) are injected intracutane-

treatment of autonomic dysfunction; spasmodic ously. Patient self-assessment and a repeated

dysphonia, vocal tics, stuttering and voice tremor, Minor’s test after treatment demonstrate excel-

oromandibular and cervical dystonia, and bleph- lent results.50 Indeed, intracutaneous injections

arospasm; hemifacial spasm and facial nerve in the area of sweating seem to have the potential

paresis; cricopharyngeal dysfunction, laryngeal to be curative in the treatment of Frey’s syn-

rebalancing, and tension headache, as well as drome, perhaps through sweat gland atrophy

use in cosmetic applications. from chronic denervation. Some patients may re-

528 Botulinum Toxin HEAD & NECK June 2005

quire more than one treatment, but the extent of of patients with spasmodic dysphonia. Its treat-

sweating decreases with each successive set of ment is essentially the same with injection of

injections until it is no longer troublesome.51 – 53 botulinum toxin into thyroarytenoid muscles

Experience with intracutaneous injection in cases and in some cases into the cricothyroid or thyro-

of Frey’s syndrome among some clinicians sug- hyoid muscles.59

gest it is a technically difficult procedure that In a series of patients with primary laryngeal

may be unnecessary. Furthermore, its proposed involvement, 16% had spread of dystonia to

immediate subcutaneous injection may allow a another part of the body.60

greater diffusion of drug and has lasting clinical All patients considered for treatment should

effects in treating gustatory sweating. have a full history and head and neck examina-

tion. Fiberoptic laryngoscopy is performed in

Spasmodic Dysphonia and Voice Tremor. ‘‘Spas- all patients to observe glottal function with

modic dysphonia’’ and ‘‘laryngeal dystonia’’ are particular reference to disruptions, spasms,

clinical terms used to describe an action-induced, breathy breaks, and tremor while the patient

laryngeal motion disorder. Patients with dystonia speaks with connected speech segments. Diagno-

may have primary (idiopathic) or secondary (eg, sis may be aided by video recording and analyzing

neurologic) disease. Dystonia may be generalized, with slow speed and stop action. Additional

multifocal, or focal. Spasmodic dysphonia is a speciality examinations include acoustic and

form of focal dystonia in which the action is that aerodynamic measurements to evaluate for trem-

of speaking. It was first described in 1871 by or, fundamental frequency, pitch and amplitude

Traube55 using the term ‘‘spastic dysphonia’’ pertubation, harshness, fluency breaks, breath-

when describing a patient with nervous hoarse- iness during sustained phonation and speech, and

ness. In 1899, Gowers56 described functional percutaneous EMG to evaluate tremor and areas

laryngeal spasm in which the vocal cords were of hyperactivity.

brought together too forcibly in speech. Aronson For the treatment of adductor dystonia, the

formally distinguished between two types of injection of botulinum toxin into the thyroaryte-

spasmodic dysphonia: an adductor type caused noid complex is achieved with an EMG needle.

by irregular hyperabduction of the vocal cords The patient is placed in the supine position with a

and an abductor type caused by intermittent pillow underneath the upper back and the neck

abduction of the vocal cords. Some patients dis- extended. The thyroid and cricoid cartilages are

play a combination of mixed adductor and abduc- palpated, and the midline of the cricothyroid

tor dysphonia. The first injection of botulinum membrane is identified. The needle is placed into

toxin into the human larynx took place in 1984, the thyroarytenoid vocalis complex by impaling

with significant relief of symptoms.57 the muscle through the cricothyroid membrane.

Patients with the adductor type exhibit a The needle is advanced at an approximately

choked, strained strangled voice quality with 30-degree angle up and 30-degree angle laterally.

abrupt initiation and termination of voice, result- The laryngologist listens for the muscle interfer-

ing in short breaks in phonation. The voice is ence pattern on the EMG. Patients are instructed

generally reduced in loudness and is monotone. not to cough or swallow while the needle is in the

Voice tremor is frequently observed, as are a slow airway. If there is difficulty tolerating the

speech rate and decreased smoothness of speech, procedure, 0.3 cm3 of 1% lidocaine may be injected

which reduces intelligibility.58 into the airway through the cricothyroid mem-

Patients with the abductor type have a brane. In the treatment of abductor dystonia, the

breathy, effortful voice quality, with abrupt ter- same preparation is used, although in this case,

mination of voicing resulting in aphonic, whis- the needle is placed posterior to the posterior edge

pered segments of speech. The voice is reduced of the thyroid lamina. The needle is advanced

in loudness, and vocal tremor related to inter- through the inferior constrictor muscle to the

mittent spasm or hypertonia of the posterior cricoid cartilage and then moved under EMG

cricoarytenoid muscles is frequently observed. guidance to the optimum position. The patient is

Vocal tremor is a common feature of neuro- asked to sniff to yield maximum abduction; 2.5 U/

logic disorders and is a sign of neurologic dis- 0.1 cm3 is used per thyroarytenoid muscle in each

turbance. Some disorders may demonstrate voice case, and repeated treatments are usually re-

tremor in combination with dysarthric speech (eg, quired. One side at a time is injected, and further

Parkinson’s disease). It is present in 25% to 65% doses may be into the same muscle or contralat-

Botulinum Toxin HEAD & NECK June 2005 529

eral muscle, depending on response. Side effects involvement of the masseter, temporalis, and ex-

of this treatment include breathy hypophonia and ternal pterygoid muscles.

clinically insignificant aspiration. In the abductor Its use in this condition has led to its appli-

patient, treatment is associated with greater risk, cation in the treatment of temporomandibular

including mild to severe stridor caused by disorders. These are described as a group of con-

paralysis of the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle. ditions affecting the temporomandibular joint,

There have been anecdotal reports requiring masticatory muscles, and associated structures.

tracheostomies. Results of treatment of adductor It often is seen as pain and dysfunction specific

spasmodic dysphonia with botulinum toxin in- to the jaw.67,68

jection are excellent, with an average benefit of Botulinum toxin has also been used in the

90% of normal function achieved. Treatment treatment of the tensor veli palatine muscle to

of the abductor type leads to an average benefit relieve the clicking tinnitus of palatal myoclo-

of 66.7% of normal voice.61 nus.69,70 Localizing the muscle may be difficult,

because mouth opening may suppress the my-

oclonus. EMG is particularly useful in placing

Vocal Tics and Stuttering. The success of botu-

the injection.71

linum toxin in the treatment of spasmodic dys-

phonia has led to its use in other conditions in

which there is inappropriate or excessive muscu- Cervical Dystonia. Cervical dystonia or torticollis

lar contraction in the larynx. Stuttering blocks, is a common form of focal dystonia.72 The use of

similar to dystonic spasms, are action-induced, botulinum toxin was first described by Tsui in

task-specific movement abnormalities. They may 1986, and since that time, its injection into the

involve respiratory, phonatory, and/or articula- various neck muscles has become the first-line

tory mechanisms of speech. When the glottis is therapeutic approach.73

affected, treatment with botulinum toxin may The treatment of cervical dystonia, as in other

result in an increased fluency by both subjective cases, relies on a thorough knowledge of anat-

and objective measures.62 The effectiveness of omy. This may include the sternocleidomastoid,

behavioral therapy has meant it is not used as a the trapezius, semispinalis capitis, the splenius

long-term treatment. capitis, the levator scapulae, and all of the lesser

Botulinum toxin has been used successfully in paraspinal muscles. Botulinum toxin type A

controlling vocal tics of Gilles de la Tourette (Botox) is injected into the affected muscles

syndrome, including coprolalia.63 – 65 Its success using total doses of 100 U per neck.73 It must be

in this context suggests an effect on the central remembered that weakening one muscle will

nervous system, possible mediated through affer- lead to the unopposed pull of its antagonist, and

ent pathways. this may lead to a change in direction of the

neck deviation.

Most patients report subjective improvement

Oromandibular Dystonia. Oromandibular dysto-

in the pain caused by muscle spasm. The most

nia is classified according to the clinical effects

common adverse events are dysphagia, neck

of the predominant muscular forces. It may,

muscle weakness, and voice changes.74

therefore, be jaw opening, jaw closing, jaw devia-

tion, or tongue protrusion dystonia or a combi-

nation of these. Some of these will be less Blepharospasm. Blepharospasm is the involun-

amenable to treatment because of difficulties in tary eye closure produced by spasmodic contrac-

compromising function during treatment. For tions of the orbicularis oculi.75 It is termed

example, tongue muscle treatment may lead to ‘‘essential blepharospasm’’ when only the orbital

dysarthria and dysphagia.66 Injection of the di- and periorbital muscles are involved. However in

gastric muscles in jaw opening may cause swal- most patients with blepharospasm, other facial,

lowing to be affected by diffusion of toxin to pharyngeal, laryngeal, oromandibular, and cer-

intrinsic tongue muscles, and it may be necessary vical muscles are affected. Idiopathic cervicocra-

to manage this complication with the insertion of nial dystonia characterized by blepharospasm

a nasogastric tube. These problems have led to a and by oromandibular involuntary movements is

limitation of what may be achieved intraorally referred to as Meige’s syndrome.

with this treatment. The types of oromandibular In blepharospasm, the lateral and medial

dystonia treated most successfully are limited to parts of the eyelid are injected subcutaneously

530 Botulinum Toxin HEAD & NECK June 2005

with botulinum toxin. One study describes the The principal disadvantages of this method

use of botulinum A toxin with an initial dosage of are the necessity for chronic treatment, the po-

12.5 U per eyelid in two separate injections, a tential for ophthalmic complications similar to

total of four injections or 25 U per eye. 76 those of blepharospasm, and facial asymmetry

Published reports document that in approxi- secondary to muscle weakening.88

mately two thirds of patients, the condition was

improved, with many regaining nearly normal Facial Nerve Paresis. During the acute phase of

function.76 – 78 In addition to the reduction of facial nerve paresis, botulinum toxin may be used

spasms, patients also report a decrease in asso- to effect a therapeutic ptosis for corneal protec-

ciated sensory complaints such as foreign body tion.89 In the recovery phase, facial nerve paresis

sensations in the eyes and photophobia. may be accompanied by synkinesis. When this is

Treatment is directed to minimize the chance troublesome, as in the case of involuntary eyelid

of ptosis, diplopia, midface weakness, and epi- closure, botulinum toxin may be useful.90

phora. This is achieved by injecting no closer to Botulinum toxin has also been used to improve

the eye than the orbital margin to minimize in- the facial symmetry of patients with facial

traorbital diffusion, avoiding the medial lower lid paralysis by decreasing the excessive pull of the

to spare the lacrimal pumping apparatus, and contralateral facial muscles during emotional

injecting no lower than the malar eminence to expression. Injections of 2.5 to 5 U into each of

prevent midface effects.27 the contralateral zygomaticus major, levators labii

superioris, and anguli oris or risorius muscles

Hemifacial Spasm. Hemifacial spasm is charac- leads to increased symmetry of the smile of

terized by initially progressive, involuntary, ir- moderate or marked benefit in most cases.91

regular, clonic or tonic movements of muscles

innervated by the seventh cranial nerve unilat-

erally. It often initially affects the orbicularis Cricopharyngeal Dysfunction. The cricopharyn-

oculi muscle, followed by gradual spread to other geus muscle is the major component of the upper

parts of the face. esophageal sphincter. The ring-shaped structure

This disorder arises when the nerve is com- maintains a constant basal tone and luminal

pressed at the root exit zone by an ectopic occlusion at rest but allows rapid relaxation and

anatomic or pathologic structure, resulting in contraction on swallowing. Dysfunction of this

emphatic transmission.79 – 82 The most common muscle is a well-known cause of dysphagia that is

cause of hemifacial spasm is compression by an most effectively treated in persistent cases by

atherosclerotic aberrant or intracranial artery cricopharyngeal myotomy. In unclear cases or

as first described by Cambell and Keedy in 1974.83 where there are temporary problems, botulinum

Microvascular decompression of the facial toxin may be used.

nerve root through a retrosigmoid craniotomy The cricopharyngeus, as stated, is activated

has proven to be very successful in controlling this at rest, which permits the use of EMG guidance

disorder,84 so that botulinum toxin remains a in percutaneous injection.92,93 An alternative is

nonsurgical alternative. The facial muscles for by directly injecting the muscle at endoscopy

injection are identified with a thorough knowl- with the patient under general anaesthesia.94

edge of anatomy and the aid of EMG. These may Patients demonstrate a 70% to 100% improve-

include orbicularis oculi, orbicularis oris, the zy- ment when undertaking this treatment.92,95,96

gomatic muscles, frontalis, corrugator, paranasal Some cricopharyngeal spasm is caused or aggra-

region, mentalis, submental area, and platysma. vated by reflux of gastric acid, which must be

Doses of botulinum toxin type A (Botox) used treated before relaxing the sphincter. Heartburn

vary, but one publication gives an average of has been reported as a complication of this

approximately 30 U per muscle in this appli- procedure.95

cation.85 The treatment gives excellent results, Cricopharyngeal spasm may rarely prevent

with 95% of patients having a marked to moder- the successful use of tracheoesophageal speech

ate improvement, and it may be used to manage after laryngectomy, and botulinum toxin has been

the condition in the long term by repeated used in its treatment.97 – 99

injection.85 – 88 Temporary facial weakness is the

most common side effect, followed by lid weakness Laryngeal Rebalancing. Rontal and Rontal100

and ptosis.85 coined the term ‘‘laryngeal rebalancing’’ to refer

Botulinum Toxin HEAD & NECK June 2005 531

to the chemodenervation of the interarytenoid CONCLUSION

muscle and the ipsilateral thyroarytenoid and Botulinum toxin has been used safely in humans

lateral cricoarytenoid muscle in the treatment for more than 20 years. The effects are transient,

of anteromedial cricoarytenoid dislocation. This such that treatments are required to be repeated

term may be appropriately applied to an array at intervals. Its application to ENT provides a

of uses. Botulinum toxin has been used to weaken useful tool to treat dystonia, autonomic dysfunc-

adductors as an adjunct to the treatment of tion, facial nerve paresis, and hyperfunctional

vocal fold granuloma,101,102 posterior glottic lines. It may also be of benefit in laryngeal

synechiae,103 and dysphonia plica ventricu- rebalancing and the treatment of headaches.

laris.104 The underlying principle is manipula- Further research is being carried out, and new

tion of the neural input to the larynx to improve indications for treatment with botulinum toxin

healing or resolution of existing disease. It has may include sialorrhea and rhinorrhea.

been proposed that botulinum toxin be used to

lateralize the vocal folds to maintain the air-

way in cases of bilateral paralysis, but, as yet,

it has only been reported in an animal model.105 REFERENCES

1. Carruthers A. Botulinum toxin type A: history and cur-

rent cosmetic use in the upper face. Dis Mon 2002;

Tension Headache. Binder first noted that pa- 48:299 – 322.

tients receiving botulinum toxin for cosmetic 2. Jankovic J, Hallett M. Therapy with botulinum toxin.

New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1994.

reasons reported an improvement or cessation 3. Carruthers J, Stubbs HA. Botulinum toxin for benign

of migraine symptoms. This was confirmed in essential blepharospasm hemifacial spasm and age re-

a double-blind, controlled trial.106 This treat- lated lower eye lid entropion. Can J Neurol Sci 1987;14:

42 – 45.

ment has also been promising in the treatment 4. Van Ermengem E. Ueber einen neuen anaeroben Bacillus

of chronic treatment of chronic tension head- und seine Beizehungen zum Botulismus. Zeitschrift

ache.107,108 Hygiene Infektionkrankheiten 1897;26:1 – 56.

5. Burke GS. Notes on the Bacillus botulinus. J Bacteriol

1919;4:555 – 565.

6. Schantz EJ, Johnson EA. Preparation and character-

Cosmetic Applications. Hyperfunctional facial ization of botulinum toxin type A for human treatment. In:

lines that run perpendicular to underling mus- Jankovic J, Hallet M, editors. Therapy with botulinum

toxin. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker Inc; 1994. p 41.

cle forces are caused by skin pleating with muscle 7. Snipe PT, Sommer H. Studies on botulinus toxin. 3. Acid

contraction. Weakening the underlying mus- precipitation of botulinus toxin. J Infect Dis 1928;43:

cle with botulinum toxin reduces or eliminates 152 – 160.

8. Schantz EJ, Johnson EA. Botulinum toxin: the story of its

these lines, which has been shown in a placebo- development for the treatment of human disease. Persp

controlled, double-blind study.109 It is effective in Biol Med 1997;40:317 – 327.

improvement of lines of the forehead, glabella, 9. Schantz EJ. Historical perspective. In: Jankovic J, Hallet

M, editors. Therapy with botulinum toxin. New York, NY:

lateral orbits, and the nasolabial region.110,111 Marcel Dekker Inc; 1994. p xxii – xxvi.

Botulinum toxin has also been used to reduce 10. Scott AB, Rosenbaum A, Collins CC. Pharmacologic

platysmal bands and adjust brow position.112 – 114 weakening of extraocular muscles. Invest Ophthalmol

1973;12:924 – 927.

With glabellar hyperkinetic lines as an exam- 11. Scott AB. Botulinum toxin injection into extraocular

ple of technique, 10 U of botulinum toxin type A muscles as an alternative to strabismus surgery.

(Botox) may be injected into each corrugator Ophthalmology 1980;87:1044 – 1049.

12. Montecucco C, Shiavo G. Mechanism of action of tetanus

muscle either with or without EMG guidance. and botulinum neurotoxins. Mol Microbiol 1994;13:1 – 8.

This treatment gives excellent results, and 75% of 13. Sakaguchi G. Clostridium botulinum toxins. Pharmacol

patients are satisfied with the improvement in Ther 1983;19:165 – 194.

14. Das Gupta BR, Sugiyama H. A common subunit

their appearance.115 structure in Clostridium botulinum type A, B and E toxins.

Biochem Biophys Res Comm 1972;48:108 – 112.

15. Binz T, Blasi J, Yamasaki S, et al. Proteolysis of SNAP-

Future Research Areas. Further research in the 25 by types E and A botulinum neurotoxins. J Biol Chem

use of botulinum toxin in the treatment of 1994;269:1617 – 1620.

16. Schiavo G, Benefenati F, Poulain B, et al. Tetanus and

sialorrhea is awaited; however, there are no botulinum-B neurotoxins block transmitter release by

current documented studies of its use in humans proteolytic cleavage of synaptobrevin. Nature 1992;359:

at present. There is also potential for the treat- 832 – 835.

17. DePaiva A, Meunier FA, Molgo J, et al. Functional repair

ment of rhinorrhea, with work currently under- of motor endplates after botulinum neurotoxin type A

way on a suitable delivery vehicle for the toxin.54 poisoning: biphasic switch of synaptic activity between

532 Botulinum Toxin HEAD & NECK June 2005

nerve sprouts and their parent terminals. Proc Natl Acad 38. Lange DJ, Rubin M, Greene PE, et al. Distant effects

Sci U S A 1999;53:1439 – 1446. of locally injected botulinum toxin: a double blind study

18. Brashear A, Lew MF, Dykstra DD, et al. Safety and of single fiber EMG changes. Muscle Nerve 1991;14:

efficacy of NeuroBloc (botulinum toxin type B) in type 672 – 675.

A responsive cervical dystonia. Neurology 1999;53: 39. Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Cosmetic use of botulinum A

1439 – 1446. exotoxin. Adv Dermatol 1997;12:325 – 347.

19. Brin MF, Lew MF, Adler CH, et al. Safety and efficacy of 40. Report of the Therapeutics in Technology Assessment

NeuroBloc (botulinum toxin type B) in type A resistant Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology:

cervical dystonia. Neurology 1999;53:1431 – 2438. Assessment: the clinical usefulness of botulinum toxin

20. Borodic GE, Mills L, Joseph M. Botulinum A toxin for the A in treating neurologic disorders. Neurology 1990;40:

treatment of adult onset spasmodic torticollis. Plast Re- 1132 – 1335.

constr Surg 1991;87:285 – 289. 41. Klein AW. Complications and adverse reactions with the

21. Brans JW, Lindeboom R, Snoek JW, et al. Botulinum use of botulinum toxin. Diso Mon 2002;5:336 – 356.

toxin versus trihexyphenidyl in cervical dystonia: a 42. Scott AH, Suzuki D. Systemic toxicity of botulinum toxin

prospective, randomised, double-blind controlled trial. by intramuscular injection in the monkey. Mov Disord

Neurology 1996;46:1066 – 1072. 1988;3:333 – 335.

22. Nussgens Z, Roggenkamper P. Comparison of two 43. Spiro RH, Martin H. Gustatory sweating following

botulinum-toxin preparations in the treatment of essen- parotid surgery and radical neck dissection. Ann Surg

tial blepharospasm. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1967;165:118 – 127.

1997;235:197 – 199. 44. Laage-Hellman JE. Treatment of gustatory sweating and

23. Odergren T, Hjaltason H, Kaakkola S, et al. A double flushing. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 1958;49:132.

blind, randomised, parallel group study, to investigate 45. Ford FR, Woodhall R. Phenomena due to misdirection of

the dose equivalence of Dysport and Botox in the regenerating fibres of cranial, spinal and automatic

treatment of cervical dystonia. J Neurol Neurosurg nerves, clinical observations. Arch Surg 1938;69:54.

Psychiatry 1998;64:6 – 12. 46. Bjerkhoel A, Trobbe O. Frey’s syndrome: treatment with

24. Nussgens Z, Roggenkamper P. Comparison of two botulinum toxin. J Laryngol Otol 1997;111:839 – 844.

botulinum-toxin preparations in the treatment of essen- 47. Selin LC. The action of botulinum toxin at the neuro-

tial blepharospasm. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol muscular junction. Med Biol 1981;59:11 – 20.

1997;235:197 – 199. 48. Drobik C, Laskawi R. Frey’s syndrome treatment

25. Odergren T, Hjalston H, Kaakkola S, et al. A double with botulinum toxin. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 1995;115:

blind, randomised, parallel group study to investigate the 459 – 461.

dose equivalence of Dysport and Botox in the treatment 49. Ein neues Verfahren zu der klinischen Untersuchung der

of cervical dystonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry Schweibadbondersung. Deutsche Zeitschrift fur Nerven-

1998;64:6 – 12. heilkunde 1927;101:302 – 306.

26. Blitzer A, Binder WJ. Cosmetic uses of botulinum 50. Laskawi R, Rohrbach S. Treatment of gustatory sweating

neurotoxin type A. Arch Fascial Plast Surg 2002;4: with botulinum toxin: special aspects. ORL 2001;63:

214 – 220. 294 – 297.

27. Blitzer A, Sulica L. Botulinum toxin: basic science and 51. Laccourreye O, Aki E, Gutierrez-Fonseca R, Garcia D,

clinical uses in otolaryngology. Laryngoscope 2001;111: Brasnu D, Bonan B. Recurrent gustatory sweating (Frey

218 – 226. syndrome) after intracutaneous injection of botulinum

28. Tsui JKC. Botulinum as a therapeutic agent. Pharmacol toxin type A: incidence, management, and outcome. Arch

Ther 1996;72:13 – 24. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;125:283 – 286.

29. Brin MF. Botulinum toxin therapy: basic science over- 52. Laskawi R, Drobik C, Schonebeck C. Up-to-date report of

view of other therapeutic applications. In: Blitzer A, botulinum toxin type A in patients with gustatory

Binder WJ, Boyd JB, Carruthers A, editors. Management sweating (Frey’s syndrome). Laryngoscope 1998;108:

of facial lines and wrinkles. Philadelphia: Lippincott 381 – 384.

Williams & Wilkins; 2000. p 279 – 302. 53. Arad-Cohen A, Blitzer A. Botulinum toxin treatment for

30. Dertzbaugh MT, West MW. Mapping of protective and symptomatic Frey’s syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck

cross-reactive domains of the type A neurotoxin of Surg 2000;122:237 – 240.

Clostridium botulinum. Vaccine 1996;16:1538 – 1544. 54. Shaari CM, Sanders I, Wu BL, Biller HF. Rhinorrhea is

31. Jankovic J, Schwartz K. Response and immunoresis- decreased in dogs after nasal application of botulinum

tance to botulinum toxin injections. Neurology 1995;45: toxin. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;112:566 – 571.

1743 – 1746. 55. Traube L. Zur Lehre von den Lerynxaffectionen beim

32. Greene P, Fahn S, Diamond B. Development of resistance Ileotyphus. Berlin: Verlag Von August Hisschwald; 1871.

to botulinum toxin A in patients with torticollis. Mov p 647 – 678.

Disord 1994;9:213 – 217. 56. Gowers WR. Manual of diseases of the nervous system.

33. Lange DI, Brin MF, Warner CL, et al. Distant effects of London: Churchill; 1899.

local injection of botulinum toxin. Muscle Nerve 1987;10: 57. Blitzer A, Brin MF, Fahn S, Lange D, Lovelace RE.

552 – 555. Botulinum toxin (BOTOX) for the treatment of ‘spastic

34. Bhatia KP, Munchau A, Thompson PD, et al. Generalised dysphonia’ as part of a trial of toxin injections for the

muscular weakness after botulinum toxin injections for treatment of other cranial dystonias. Laryngoscope 1986;

dystonia: a report of three cases. J Neurol Neurosurg 96:1300 – 1301.

Psychiatry 1999;67:90 – 93. 58. Blitzer A, Lovelace RE, Brin MF, et al. Electromyo-

35. Borodic GE, Ferrante R. Effects of repeated botulinum graphic findings in focal laryngeal dystonia (spasmodic

toxin injections on the orbicularis oculi muscle. J Clin dysphonia). Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1985;94:591 – 594.

Neuroopthalmol 1992;12:121 – 127. 59. Hertegard S, Granqvist S, Lindestad P. Botulinum toxin

36. Ansved T, Odergen T, Brog K. Muscle fibre atrophy in leg injections for essential voice tremor. Ann Otol Rhinol

muscles after botulinum toxin type A treatment of Laryngol 2000;109:204 – 209.

cervical dystonia. Neurology 1997;48:1440 – 1442. 60. Brin MF, Fahn S, Blitzer A, et al: Movement disorders of

37. Sanders DB, Massey EW, Buckley EG. Botulinum toxin the larynx. In: Blitzer A, Brin MF, Sasake CT, editors.

for blepharospasm: single-fiber EMG studies. Neurology Neurological disorders of the larynx. New York: Thieme;

1986;36:545 – 547. 1992. p 240 – 810.

Botulinum Toxin HEAD & NECK June 2005 533

61. Gibbs SR, Blitzer A. Botulinum toxin for the treatment of spasm: a single fibre EMG study. Muscle Nerve 1989;

spasmodic dysphonia. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2000; 12:690 – 694.

4:879 – 894. 83. Cambell E, Keedy C. Hemifacial spasm: a note on the

62. Brin MF, Stewart C, Blitzer A, Diamond B. Laryngeal etiology in two cases. J Neurosurg 1974;4:342 – 347.

botulinum toxin injections for disabling stuttering in 84. Janetta PJ, Abbasy M, Maroon JC, Ramos FM, Albin MS.

adults. Neurology 1994;44:2262 – 2266. Etiology and definitive microsurgical treatment of hemi-

63. Salloway S, Stewart CF, Israeli L, et al. Botulinum toxin facial spasm: operative techniques and results in 47 pa-

for refractory vocal tics. Mov Disord 1996;11:746 – 748. tients. J Neurosurg 1987;47:321 – 328.

64. Scott BL, Jankovic J, Donovan DT. Botulinum toxin 85. Wang A, Jankovic J. Hemifacial spasm: Clinical findings

injected into the vocal cord in the treatment of malignant and treatment. Muscle Nerve 1998;21:1740 – 1747.

coprolalia associated with Tourette’s syndrome. Mov 86. Savino PJ, Sergott RC, Bosley TM, Schatz NT. Hemi-

Disord 1996;11:431 – 433. facial spasm treated with botulinum toxin injections.

65. Trimble MR, Whurr R, Brookes G, Robertson MM. Vocal Arch Opthalmol 1985;103:1305 – 1306.

tics in Gilles de la Tourette syndrome treated with 87. Brin MF, Fahn S, Moskowitz C, et al. Localised injections

botulinum toxin injections. Mov Disord 1998;13:617 – 619. of botulinum toxin for the treatment of focal dystonia and

66. Brin MF, Blitzer A, Herman S, Stewart C. Oromandib- hemifacial spasm. Mov Disord 1987;2:237 – 254.

ular and lingual dystonia (Meige syndrome). In: Moore P, 88. Borodic GE. Hemifacial spasm: evaluation and man-

editor. Handbook of botulinum toxin treatment. London: agement, with emphasis on botulinum toxin therapy.

Blackwell Science; 1995. p 151 – 163. In: Jankovic J, Hallett M, editors. Therapy with bot-

67. Moore AP, Wood GD. Medical treatment of recurrent ulinum toxin. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1994.

temporomandibular joint dislocation using botulinum A. p 331 – 351.

Br Dent J 1997;183:415 – 417. 89. Elston JS. Idiopathic blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm

68. Freund B, Schwartz M, Symington JM. The use of and therapeutic ptosis induction. In: Moore P, editor.

botulinum toxin for the treatment of temporomandibular Handbook of botulinum toxin treatment. London: Black-

disorders: preliminary findings. J Oral Maxillofac Surg well Science; 1995. p 90 – 100.

1999;57:916 – 921. 90. Borodic GE, Pearce LB, Cheney M. Botulinum toxin A for

69. Saeed SR, Brooks GB. The use of clostridium botulinum treatment of aberrant facial nerve regeneration. Plast

toxin in palatal myoclonus: a preliminary report. J Lar- Reconstr Surg 1993;91:1042 – 1045.

yngol Otol 1993;107:208 – 210. 91. Bikhazi NB, Maas CS. Refinement in the rehabilitation

70. Bryce GE, Morrison MD. Botulinum toxin treatment of of the paralysed face using botulinum toxin. Otolaryngol

essential palatal myoclonus tinnitus. J Otolaryngol 1998; Head Neck Surg 1997;117:303 – 307.

27:213 – 216. 92. Blitzer A, Brin M. Use of botulinum toxin for diagnosis

71. Deuschl G, Lohle E, Toro C, Hallett M, Lebovics RS. and management of cricopharyngeal achalasia. Otolar-

Botulinum treatment of palatal tremor (myoclonus). In: yngol Head Neck Surg 1997;116:328 – 330.

Jankovic J, Hallett M, editors. Therapy with botulinum 93. Crary MA, Glowasky AL. Using botulinum toxin A to

toxin. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1994. p 567 – 576. improve speech swallowing function following total

72. Nutt JG, et al. Epidemiology of focal and generalised laryngectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg

dystonia in Rochester, Minnesota. Mov Disord 1988;3: 1996;122:760 – 763.

188 – 194. 94. Haapenieni JJ, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of

73. Tsui JKC, Eisen A, Stoessel AJ, Calne S. Double blind cricopharyngeal dysphagia. Dysphagia 2001;16:171 – 175.

study of botulinum toxin in spasmodic torticollis. Lancet 95. Schneider I, Thumfart WF, Potoschnig C, Eckel HE.

1986;11:245 – 246. Treatment of dysfunction of the cricopharyngeal muscle

74. Poewe W, Deuschl G, Nebe A, et al. What is the optimal with botulinum A toxin: introduction of a new, non-

dose of botulinum toxin A in the treatment of cervical invasive method. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1994;103:

dystonia? Results of a double blind, placebo controlled, 31 – 35.

dose ranging study using Dysport. J Neurol Neurosurg 96. Ahsan SF, Meleca RJ, Dworkin JP. Botulinum toxin

Psychiatry 1998;64:13 – 17. injection of the cricopharyngeus muscle for the treat-

75. Jankovic J. Clinical features, differential diagnosis and ment of dysphagia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;

pathogenesis of blepharospasm and cranial-cervical 122:691 – 695.

dystonia. In: Bosniak SL, editor. Blepharospasm, ad- 97. Blitzer A, Komisar A, Baredes S, Brin MF, Stewart C.

vanced ophthalmology plastic reconstructive surgery, vol Voice failure after tracheoesophageal puncture: manage-

4. New York: Pergamon Press; 1985. p 67 – 82. ment with botulinum toxin. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg

76. Jankovic J. Blepharospasm and oromandibular-laryng- 1995;113:668 – 670.

eal-cervical dystonia: a controlled trial of botulinum a 98. Hoffman HT, Fischer H, VanDenmark D, et al. Botu-

toxin therapy. Adv Neurol 1988;50:583 – 591. linum toxin injection after total laryngectomy. Head

77. Elston JS. Botulinum toxin for blepharospasm. In: Neck 1997;17:92 – 97.

Jankovic J, Hallett M, editors. Therapy with botulinum 99. Zormeier MM, Meleca RJ, Simpson ML, et al. Botulinum

toxin. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1994. p 191 – 197. toxin to improve tracheoesophageal speech after total

78. Scott AB, Kennedy RA, Stubbs HA. Botulinum toxin A laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;120:

injection as a treatment for blepharospasm. Arch Op- 314 – 319.

thalmol 1985;103:350 – 374. 100. Rontal E, Rontal M. Laryngeal rebalancing for the treat-

79. Auger RG, Piepgas DG, Laws ER, Miller RH. Micro- ment of arytenoid dislocation. J Voice 1998;12:383 – 388.

vascular decompression of the facial nerve for hemifacial 101. Nasri S, Sercaz JA, McAlpin T, Berke GS. Treatment of

spasm: clinical and electrophysiologic observations. Neu- vocal fold granuloma using botulinum toxin type A.

rology 1981;31:346 – 350. Laryngoscope 1995;105:585 – 588.

80. Nielson VK. Pathophysiology of hemifacial spasm: I. 102. Orloff LA, Goldman SN. Vocal fold granuloma: success-

Ephaptic transmission and ectopic excitation. Neurology ful treatment with botulinum toxin. Otolaryngol Head

1984;34:418 – 426. Neck Surg 1999;121:410 – 413.

81. Nielson VK. Electrophysiology of the facial nerve in 103. Nathan CO, Yin S, Stucker FJ. Botulinum toxin: ad-

hemifacial spasm: ectopic/ephaptic excitation. Muscle junctive treatment for posterior glottic synechiae. La-

Nerve 1985;8:545 – 555. ryngoscope 1999;109:855 – 857.

82. Sanders DB. Ephaptic transmission in hemifacial 104. Kendall KA, Leonard RJ. Treatment of ventricular

534 Botulinum Toxin HEAD & NECK June 2005

dysphonia with botulinum toxin. Laryngoscope 1997; 110. Blitzer AB, Binder WJ, Aviv JE, Keen MS, Brin MF. The

107:948 – 953. management of hyperfunctional lines with botulinum

105. Cohen SR, Thompson JW, Camilon FS. Botulinum toxin toxin. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:

for relief of bilateral abductor paralysis of the larynx: 389 – 392.

histologic study in an animal model. Ann Otol Rhinol 111. Blitzer A, Binder WJ, Brin MF. Botulinum toxin injec-

Laryngol 1989;98:213 – 216. tion for facial lines and wrinkles: technique. In: Blitzer A,

106. Mathew NT, Saper JR, Silberstein SD, et al. A multicen- Binder WJ, Boyd JB, Carrruthers A, editors. Manage-

ter, double blind, placebo controlled trial of two dosages ment of facial lines and wrinkles. Philadelphia: Lippin-

of botulinum toxin type A (BOTOX) in the prophylactic cott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. p 303 – 313.

treatment of migraine. Neurology 1999;52:A256. 112. Frankel AS, Kamer FM. Chemical browlift. Arch Otolar-

107. Zwart JA, Bovim G, Sand T, Sjaastad O. Tension head- yngol Head Neck Surg 1998;124:321 – 323.

ache: botulinum toxin paralysis of temporal muscles. 113. Matarsso A, Matarasso SL, Brandt FS, Bellman B.

Headache 1994;34:458 – 462. Botulinum A exotoxin for the management of platysma

108. Schulte-Mtter WJ, Weiser T, Zierz S. Treatment of bands. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;103:645 – 652.

tension type headache with botulinum toxin: a pilot 114. Kane MA. Nonsurgical treatment of platysma bands with

study. Eur J Med Res 1999;26:183 – 186. injection of botulinum toxin A. Plast Reconstr Surg

109. Keen MS, Blitzer A, Aviv JE, et al. Botulinum toxin A 1999;103:656 – 663.

for hyperkinetic facial lines: results of a double blind, 115. Edmund A. et al. Patient selection in the treatment of

placebo controlled study. Plast Reconstr Surg 1994;94: glabellar wrinkles with botulinum toxin type A injection.

94 – 99. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:321 – 326.

Botulinum Toxin HEAD & NECK June 2005 535

Вам также может понравиться

- Botulinum Toxin Type A - History and Current Cosmetic Use in The Upper Face - CarruthersДокумент14 страницBotulinum Toxin Type A - History and Current Cosmetic Use in The Upper Face - CarruthersRafael Autran Cavalcante AraújoОценок пока нет

- SAENI - Medicina Estética Facial - Clase 2 - Aesthetic Uses of The Botulinum ToxinДокумент14 страницSAENI - Medicina Estética Facial - Clase 2 - Aesthetic Uses of The Botulinum ToxinAgustin GiraudoОценок пока нет

- The History of Botulinum Toxin From Poison To BeautyДокумент3 страницыThe History of Botulinum Toxin From Poison To BeautyElaine MedeirosОценок пока нет

- 276 BotoxДокумент4 страницы276 BotoxSerban RosuОценок пока нет

- Assaignment On Clostridium BotulinumДокумент11 страницAssaignment On Clostridium BotulinumRifath AhmedОценок пока нет

- BotulinumДокумент151 страницаBotulinumisabel90% (10)

- Bacterial Toxins and Its ApplicationДокумент10 страницBacterial Toxins and Its Applicationlamps42Оценок пока нет

- 2002 Uses of Botulinum Toxin Injection in Medicine TodayДокумент5 страниц2002 Uses of Botulinum Toxin Injection in Medicine TodayAtac SonmezОценок пока нет

- Sheen 2020Документ15 страницSheen 2020Şükriye AngaОценок пока нет

- Jocd 18 1215Документ9 страницJocd 18 1215vanessa_werbickyОценок пока нет

- Toxin Botulinum For StrabismusДокумент8 страницToxin Botulinum For StrabismusRay MaudyОценок пока нет

- Botulinum Toxin: B. Zane Horowitz, MD, FACMTДокумент15 страницBotulinum Toxin: B. Zane Horowitz, MD, FACMTŞükriye AngaОценок пока нет

- Complications Bot ToxДокумент9 страницComplications Bot ToxSGОценок пока нет

- Botulinum Toxin in Pediatric Neurology: Switching Lanes From Death To LifeДокумент9 страницBotulinum Toxin in Pediatric Neurology: Switching Lanes From Death To LifeAnonymous QOCn5dОценок пока нет

- The Wonderful Story of Monoclonal Antibodies: Marie C BénéДокумент7 страницThe Wonderful Story of Monoclonal Antibodies: Marie C BénéNurkhalis BintangОценок пока нет

- Friedman JM 2021Документ5 страницFriedman JM 2021Vlad VochituОценок пока нет

- BotoxДокумент7 страницBotoxSanjaya FaisalОценок пока нет

- Bacteria With Toxin-Dr AnceДокумент32 страницыBacteria With Toxin-Dr AnceSuita Allemina Gloria SitepuОценок пока нет

- Sialoree BotoxДокумент5 страницSialoree BotoxJocul DivinОценок пока нет

- Botulinum Neurotoxins: Mechanism of Action: O. Rossetto, M. Pirazzini, F. Fabris, and C. MontecuccoДокумент13 страницBotulinum Neurotoxins: Mechanism of Action: O. Rossetto, M. Pirazzini, F. Fabris, and C. Montecuccofmmw6qdgzvОценок пока нет

- Toxina Botulinica PDFДокумент24 страницыToxina Botulinica PDFReynaldo Miranda AlarcónОценок пока нет

- Comparison of Botulinum Toxin Types A and BДокумент7 страницComparison of Botulinum Toxin Types A and Balinutza_childОценок пока нет

- Kumar 2017Документ31 страницаKumar 2017anggaririnОценок пока нет

- Biochemical Aspects: Clostridium Botulinum, An Anaerobic, Gram-Positive, Spore-Forming Rod CommonlyДокумент13 страницBiochemical Aspects: Clostridium Botulinum, An Anaerobic, Gram-Positive, Spore-Forming Rod CommonlyRangga Patria LazuardiОценок пока нет

- Botulinum Toxin As A Biological Weapon Norad-Usnorthcom/SgДокумент3 страницыBotulinum Toxin As A Biological Weapon Norad-Usnorthcom/Sgsohailahmad76Оценок пока нет

- Kwon2019 Article ApplicationOfBotulinumToxinInMДокумент13 страницKwon2019 Article ApplicationOfBotulinumToxinInMFelipe LazoОценок пока нет

- Eosinophils in Health and DiseaseОт EverandEosinophils in Health and DiseaseJames J. LeeОценок пока нет

- 2004, Vol.22, Issues 2, The Clinical Use of Botulinum ToxinДокумент90 страниц2004, Vol.22, Issues 2, The Clinical Use of Botulinum ToxinRizweta Destin100% (1)

- Botulinum Toxin Type B For The Treatment of A Sialocele After ParotidectomyДокумент3 страницыBotulinum Toxin Type B For The Treatment of A Sialocele After ParotidectomyElianaОценок пока нет

- Overview of Neuromuscular Junction ToxinsДокумент36 страницOverview of Neuromuscular Junction Toxinsmayteveronica1000Оценок пока нет

- Botox G Art 2016Документ13 страницBotox G Art 2016Anamaria ZaccoloОценок пока нет

- Botulinum Toxin Therapeutic Mechanisms of Action.Документ7 страницBotulinum Toxin Therapeutic Mechanisms of Action.javierapobletevergaraОценок пока нет

- Antimicrobials 1: DR Sushela DeviДокумент57 страницAntimicrobials 1: DR Sushela DevilimОценок пока нет

- Https:watermark Silverchair Com:41-8-1167Документ7 страницHttps:watermark Silverchair Com:41-8-1167Doni SaragihОценок пока нет

- Kuliah 2 Bahan Biologi (Mikroba) Penyebab Keracunan PanganДокумент21 страницаKuliah 2 Bahan Biologi (Mikroba) Penyebab Keracunan PanganAchmad HilmyОценок пока нет

- BotulismДокумент29 страницBotulismRohan TejaОценок пока нет

- The Cell Cycle Inhibitor P21 Promotes The Development of - 2022 - Acta PharmaceДокумент12 страницThe Cell Cycle Inhibitor P21 Promotes The Development of - 2022 - Acta PharmaceMohammed Shuaib AhmedОценок пока нет

- Biogenesis of Antibiotic SubstancesОт EverandBiogenesis of Antibiotic SubstancesZdenko VanekОценок пока нет

- Cell InjuryДокумент4 страницыCell Injuryمحمد نزار غياث الدينОценок пока нет

- Messengers From The MicrobiotaДокумент3 страницыMessengers From The MicrobiotaDra. Ianna CarmoОценок пока нет

- Fibrocytes at 20 Years-BucalaДокумент3 страницыFibrocytes at 20 Years-BucalaCiro GuerraОценок пока нет

- Extracellular Superoxide Dismutase in Macrophages Augments Bacterial Killing by Promoting PhagocytosisДокумент8 страницExtracellular Superoxide Dismutase in Macrophages Augments Bacterial Killing by Promoting PhagocytosisRezdy Tofan BhaskaraОценок пока нет

- Extrinsic and Intrinsic Apoptosis Signal Pathway Review: Zhao HongmeiДокумент20 страницExtrinsic and Intrinsic Apoptosis Signal Pathway Review: Zhao HongmeiAgustina PramudianingtiasОценок пока нет

- Bakteri Penghasil Toksin: DR Ance Roslina, M.Kes Departemen Mikrobiologi FK - UMSU 2017Документ26 страницBakteri Penghasil Toksin: DR Ance Roslina, M.Kes Departemen Mikrobiologi FK - UMSU 2017wiraОценок пока нет

- Introducing The Sorush Cancer Treatment Protocol (SCTP)Документ18 страницIntroducing The Sorush Cancer Treatment Protocol (SCTP)SorushОценок пока нет

- Biophotons and Bone Growth FactorДокумент7 страницBiophotons and Bone Growth FactorAntonis TzambazakisОценок пока нет

- BBB & EpilepsyДокумент14 страницBBB & EpilepsyBujoreanu IulianОценок пока нет

- Antifungal AgentsДокумент5 страницAntifungal AgentsNutan Desai RaoОценок пока нет

- Bourne 1952 LancetДокумент5 страницBourne 1952 LancetFábioОценок пока нет

- Glucocorticoids 2014Документ6 страницGlucocorticoids 2014NELLY LOPEZОценок пока нет

- Toxicna e InglesДокумент26 страницToxicna e InglesIngrid Allazo BejarОценок пока нет

- Myo Inositol and D Chiro Inositol As Modulators of Ovary SteroidogenesisДокумент14 страницMyo Inositol and D Chiro Inositol As Modulators of Ovary SteroidogenesisTanyaОценок пока нет

- Biochemical Lesions and Lethal Synthesis: International Series of Monographs on Pure and Applied Biology: Modern Trends in Physiological SciencesОт EverandBiochemical Lesions and Lethal Synthesis: International Series of Monographs on Pure and Applied Biology: Modern Trends in Physiological SciencesОценок пока нет

- Effects of Phycocyanin On Pulmonary and Gut Microbiota in A Radiation-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis ModelДокумент9 страницEffects of Phycocyanin On Pulmonary and Gut Microbiota in A Radiation-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis ModelChawki MokademОценок пока нет

- Statins: in The Beginning: PaperДокумент3 страницыStatins: in The Beginning: PaperErisa MawaddahОценок пока нет

- Addisu TGF BetadermatologyДокумент7 страницAddisu TGF Betadermatologyطارق المتوليОценок пока нет

- The Effffect of Nitric o Ide On Mitochondrial RespirationДокумент23 страницыThe Effffect of Nitric o Ide On Mitochondrial RespirationDaniel Amaro VillajulcaОценок пока нет

- Hypertensionaha 118 PDFДокумент8 страницHypertensionaha 118 PDFKhilyatul MufidaОценок пока нет

- JNC8 HTNДокумент2 страницыJNC8 HTNTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- Jurnal Tentang Refluks VesikovaginalДокумент4 страницыJurnal Tentang Refluks VesikovaginalKhilyatul MufidaОценок пока нет

- Mechanis All DonepezilДокумент18 страницMechanis All DonepezilKhilyatul MufidaОценок пока нет

- A Study On Psoriasis of Nails Severity Scoring SystemДокумент4 страницыA Study On Psoriasis of Nails Severity Scoring SystemKhilyatul MufidaОценок пока нет

- SPF 100+ Sunscreen Is More ProtectiveДокумент17 страницSPF 100+ Sunscreen Is More ProtectiveKhilyatul MufidaОценок пока нет

- Causes and Treatment TonsilitisДокумент6 страницCauses and Treatment TonsilitisKhilyatul MufidaОценок пока нет

- ATS Guidelines CAP ManagementДокумент25 страницATS Guidelines CAP ManagementMae Matira AbeladorОценок пока нет

- JNC8 HTNДокумент2 страницыJNC8 HTNTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- JNC8 HTNДокумент2 страницыJNC8 HTNTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- Answer Set 5 - Fall 2009Документ38 страницAnswer Set 5 - Fall 2009zachОценок пока нет

- Installation Manual of FirmwareДокумент6 страницInstallation Manual of FirmwareOmar Stalin Lucio RonОценок пока нет

- Kibera Mirror JULYДокумент8 страницKibera Mirror JULYvincent achuka maisibaОценок пока нет

- Neonatal Resuscitation ProgramДокумент6 страницNeonatal Resuscitation ProgramRick Frea100% (5)

- Helena HelsenДокумент2 страницыHelena HelsenragastrmaОценок пока нет

- Dania - 22 - 12363 - 1-Lecture 2 Coordinate System-Fall 2015Документ34 страницыDania - 22 - 12363 - 1-Lecture 2 Coordinate System-Fall 2015erwin100% (1)

- Examples Week1 CompressДокумент6 страницExamples Week1 CompressAngel HuitradoОценок пока нет

- TSM 101 Course Outline (2022)Документ2 страницыTSM 101 Course Outline (2022)ChryseanjОценок пока нет

- PGT Computer Science Kendriya Vidyalaya Entrance Exam Question PapersДокумент117 страницPGT Computer Science Kendriya Vidyalaya Entrance Exam Question PapersimshwezОценок пока нет

- Marketing Research Completed RevisedДокумент70 страницMarketing Research Completed RevisedJodel DagoroОценок пока нет

- Body LanguageДокумент17 страницBody LanguageAR PiZaОценок пока нет

- Baltrushes2006 PDFДокумент46 страницBaltrushes2006 PDFsilikondioksidaОценок пока нет

- Structure of An Atom Revision PaperДокумент5 страницStructure of An Atom Revision PaperZoe Kim ChinguwaОценок пока нет

- A Seventh-Day Adventist Philosophy of MusicДокумент5 страницA Seventh-Day Adventist Philosophy of MusicEddy IsworoОценок пока нет

- Method For Determination of Iron Folic Acid & Vitamin B12 in FRK - 07.11.2023Документ17 страницMethod For Determination of Iron Folic Acid & Vitamin B12 in FRK - 07.11.2023jonesbennetteОценок пока нет

- Gunnar Fischer's Work On Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal and Wild StrawberriesДокумент6 страницGunnar Fischer's Work On Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal and Wild StrawberriesSaso Dimoski100% (1)

- Doyennés Et Granges de L'abbaye de Cluny (A. Guerreau)Документ45 страницDoyennés Et Granges de L'abbaye de Cluny (A. Guerreau)theseus11Оценок пока нет

- ACI 318M-11 RC Bracket and Corbel Design - v0.03 - 2017-04-10Документ5 страницACI 318M-11 RC Bracket and Corbel Design - v0.03 - 2017-04-10arken123Оценок пока нет

- 8 - Packed Tower Design-1Документ65 страниц8 - Packed Tower Design-1M.H vafaeiОценок пока нет

- Lecture 4 EMAДокумент36 страницLecture 4 EMAYai IbrahimОценок пока нет

- Jim 1000 RC 3Документ33 страницыJim 1000 RC 3singingblueeОценок пока нет

- Folktales Stories For Kids: Two Brothers StoryДокумент1 страницаFolktales Stories For Kids: Two Brothers StoryljОценок пока нет

- Norman Gulley: A Christ-Centered Approach To Last-Day EventsДокумент35 страницNorman Gulley: A Christ-Centered Approach To Last-Day EventsJorge Luis Echeverry González100% (1)

- Format Mini Lesson Plan: What Is Narrative Text?Документ3 страницыFormat Mini Lesson Plan: What Is Narrative Text?Muhammad FahrurajiОценок пока нет

- CV - en - Hamdaoui Mohamed AmineДокумент2 страницыCV - en - Hamdaoui Mohamed AmineHAMDAOUI Mohamed Amine100% (1)

- Epri Guide For Transmission Line Groundingpdf PDF FreeДокумент188 страницEpri Guide For Transmission Line Groundingpdf PDF FreeHolman Wbeimar Suarez Niño100% (1)

- K. Subramanya - Engineering Hy-Hill Education (India) (2009) 76Документ1 страницаK. Subramanya - Engineering Hy-Hill Education (India) (2009) 76ramsinghmahatОценок пока нет

- Comparative Analysis of State Bank of India With Other Credit SchemesДокумент97 страницComparative Analysis of State Bank of India With Other Credit SchemesVKM2013Оценок пока нет

- UKAYUNIK Chapter 1 To 12Документ31 страницаUKAYUNIK Chapter 1 To 12Chiesa ArellanoОценок пока нет

- A320 Abnormal Notes: Last UpdatedДокумент13 страницA320 Abnormal Notes: Last UpdatedDevdatt SondeОценок пока нет