Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

ARI Etio&Epio PDF

Загружено:

Rizki Agung PrasetyoОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

ARI Etio&Epio PDF

Загружено:

Rizki Agung PrasetyoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Acute Respiratory Infections in

. Children: Etiology and Epidemiology

Floyd W. Denny, MD*

Acute respiratory infections are the Likewise, emphasis will be placed on

most common affliction of humans, respiratory illnesses as they are en-

EDUCATiONAL OBJECTIVES

and their tendency to occur with countered in the practice of pediat-

much greater frequency in children rics, only a small proportion of which 98. Appropriate recognition of the

makes them especially important to require hospitalization. risks of indoor air pollution (Recent

the pediatrician. A host of microbial Advances, 87/88).

agents can cause acute respiratory CLASSIFICATION OF ACUTE 99. Appropriate knowledge of the

infections but only a few are respon- RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS multiple factors involving suscep-

sive to antimicrobial agents. Because tibility to respiratory diseases in

of the paucity of definitive laboratory Acute respiratory infections can be

children (Recent Advances, 87/

tools that allow the easy recognition classified conveniently by separating

88).

of the cause of acute respiratory in- the upper from the lower tracts at the

fections, it is important for the prac- epiglottis, although it is recognized

ticing pediatrician to have other meth- that infection involves both areas in

ods that aid in the clinical manage- some children (Fig 1).

ment of children with these infections.

It is the purpose of this review to Upper Respiratory Tract Infections Lower Respiratory Tract Infections

discuss the etiology and epidemiol- The majority of upper respiratory The majority of lower respiratory

ogy of acute respiratory infections tract infections are not complicated tract infections are not complicated

with emphasis on how this knowl- by any of the entities listed in Fig 1 . and can be classified by the anatomic

edge can guide the clinician in their The most common complication is area of the respiratory tract that is

management. The groundwork for otitis media. The proportion of pi primarily affected. The findings that

the major emphasis of the paper will

be laid by suggesting a classification

tients with upper respiratory tract in- /

characterize the clinical lower respi-

fection in whom otitis media develops ratory tract infection syndromes are

S of upper and lower respiratory

infections. Causative

tract

agents will be

depends on several factors, including

age of the child and the agent causing

given in Table 1 Infection may involve

.

>more than one site of the lower tract,

enumerated and put into perspective.

The major factors associated with the

the upper respiratory tract infection, (

but most infected children have a sin-

and vanes from 15% to 25% in chil- gle site of major involvement. This

occurrence of acute respiratory infec- dren younger than 1 year of age and \ciassification of lower respiratory

tions will be discussed in some detail 2% to 5% in those of early school)tract infections has been especially

and several risk factors will be eval- age.1 Our present knowledge of the useful because there is close associ-

uated. etiology of upper respiratory tract in- ation between syndrome and other

It is important for the reader to fections suggests that among un- associated factors, including causa-

understand that the field of acute res- complicated cases it is important only tive agent.

piratory tract infections is so exten- to identify those children infected with

sive and complex that a complete the group A streptococcus. Although

discussion of the entire field is not ETIOLOGY OF ACUTE

the upper respiratory tract infection

possible in this review. Emphasis will RESPIRATORY TRACT

clinical syndromes of herpetic gin- INFECTIONS

be placed primarily on uncomplicated givostomatitis, pharyngoconjunctival

acute respiratory infections with only fever, herpangina, lymphonodular The causative agents associated

mention of the role of complications. pharyngitis, and hand, foot, and with acute respiratory infections are

mouth disease may suggest specific relatively well understood and are

causative agents, the specific orga- similar everywhere in the world where

* Dr Denny received his medical and pediatric nism is usually not clear. Many terms studies have been done. All classes

housestaff training at Vanderbilt University.

have been used to classify infections of microorganisms, including viruses,

After holding faculty positions at the University of the upper respiratory tract includ- bacteria, fungi, parasites, and proto-

of Minnesota, Vanderbilt University, and Case ing common cold; upper respiratory zoa are capable of infecting the res-

Western Reserve University, he was Chairman tract infection, either afebnle or fe- piratory tract. Only certain viruses

of Pediatrics at the University of North Carolina

from 1960 to 1981. He is now director of the

brile; pharyngitis; tonsillitis; and phar- and bacteria are common causes, es-

University of North Carolina School of Medicine yngotonsillitis. Because of the vague- pecially in nonhospitalized children,

Program on Health Promotion and Disease Pre- ness of most of these terms, it is and this review will be restricted to

vention. He has had an interest for many years probably best to concentrate primar- these agents. The isolations of vi-

ily on differentiating group A strepto- ruses and bacteria in children in day-

S aspects

in

dress:

the laboratory,

Medicine,

Department

of childhood clinical,

University

of

respiratory

Pediatrics,

and infections.

epidemiologic

of North Carolina,

School Ad-of

Chapel

coccal upper respiratory tract infec-

tions from all others that do not re-

care and a pediatric

Chapel Hill, NC are shown in Tables

practice in

Hill, NC 27514. quire antimicrobial therapy. 2 and 3, respectively, and are repre-

pediatrics in review #{149} vol. 9 no. 5 november 1987 PIR 135

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

Respiratory Infections

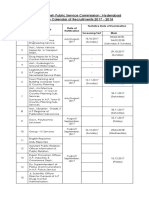

Upper Respiratory Infections TABLE 1. Clinical Syndromes in

Childhood Infections of Lower

Respiratory Tract

Uncomplicated Complicated Infection Signs of Illness

Adenitis

Croup Hoarseness,

cough, inspira-

Epiglottitis

tory stridor with

1 Lower respiratory infection

Mastoiditis

laryngeal 01>

StreptococcalNonstreptococcal struction

Otitis medle

Peritonsillar abscess

Tracheo- Cough and rhonchi;

Retropharyngeal abscess

bronchitis no laryngeal 01>

Sinusitis

struction or

wheezing

Bronchiolitis Expiratory wheez-

ing with or with-

Lower Respiratory Infections out tachypnea,

air trapping, and

substemal re-

tractions

Uncomplicated

Pneumonia Rales or evidence

Complicated

or pulmonary

Croup Atelectasis

consolidation on

Tracheobronchitis physical exami-

Bacterial tracheltis

Bronchiolitis Empyema

nation or radi-

Pneumonia Lung abscess

ograph

Mediastinitis

Pencarditis

Pneumothorax

Fig 1. Classification of acute upper and lower respiratory tract infections.

discussed in further detail. Chiamydia

trachomatis has been described re-

cently as a cause of pneumonia in

hospitalized children, but its role in

sentative of other similar studies.2’3 acute respiratory infections are nonhospltalized thildren is unknown4;

In the day-care center fewer than shown in Table 4. Corynebacterium it has also been described in one

1 0% of infections involved the lower diphtheriae, Bordetella pertussis, study as a cause of pharyngitis in

respiratory tract; therefore figures in and Mycobacterium tuberculosis are adults,5 but results of other studies

Table 2 represent the causes primar- listed as unusual causes because have not confirmed this.6 Data are

ily of upper respiratory tract infec- they are not common causes of acute beginning to accumulate that suggest

tions, whereas figures in Table 3 are respiratory infections in the United that non-group A streptococci, es-

exclusively from children with lower States today, although there is some pecially group C and G, may cause

respiratory tract infections. A com- fear (supported by some data) that pharyngitis, but their precise role is

parison of the tables shows that the pertussis may be increasing in fre- unclear.7 C trachomatis and non-

same agents are involved generally in quency. Legionella pneumophlla group A streptococci will not be con-

infertions in both sites but vary in does not cause frequent disease sidered further.

their relative roles. The group A strep- in children. Staphylococcus aureus, The roles of S pneumoniae and

tococcus is a common cause of up- group B streptococcus, Enterobac- Haemophllus influenzae cannot be

per respiratory tract infections but teriaceae, and nckettsiae cause dispatched so easily. Both are rec-

rarely of lower respiratory tract infec- acute respiratory infections but only ognized causes of lower respiratory

tions. Other examples are the ade- in certain special circumstances, an tract infections but pose special prob-

noviruses, enteroviruses, and rhino- example being in the newborn. The lems in diagnosis. Although type b H

viruses which are more commonly agents that cause infections unusu- influenzae is associated commonly

found in infections of the upper res- ally or only in special circumstances with acute epiglottitis, and S pneu-

piratory tract and MyCoplasma pneu- are of less concern in the daily prac- moniae with lobar pneumonia in the

moniae in infections of the lower res- tice of pediatrics and will not be con- older child, these two bacteria have

piratory tract. With the exceptions of sidered further. not been associated closely with any

the group A streptococcus and M Group A streptococcus is the prime of the syndromes listed in Table 1,

pneumoniae, bacterial causes of bacterial cause of upper respiratory and they are not recognized causes

acute respiratory infections are less tract infections and M pneumoniae is of uncomplicated upper respiratory

well-defined. The author’s perception a common cause of lower respiratory tract infections. This makes the clini-

of the role of bacteria as causes of tract infections; these agents will be cal diagnosis of lower respiratory

PIR 136 pediatrics in review #{149} vol. 9 no. 5 november 1987

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

INFECTIOUS DISEASE

S tract infections caused by these

agents difficult. This problem is com- TABLE 2. Viral and Bacterial TABLE 3. Viral and

pounded by the carnage of H influ- Causes of Acute Respiratory Mycoplasmal Causes of Acute

enzae and S pneumoniae in the upper Infections of Children in Day Care, Lower Respiratory Tract Infections

respiratory tract in a high percentage Chapel Hill, North Carolina in Children, Chapel Hill, North

(up to 20% and 50%, respectively) of Relative Carolina*

normal children at certain ages and Cause Role Relative

during seasons.8 The failure

certain (%) Cause Role

of anticapsular polysaccharide anti- Viruses (%)

bodies to develop in young children Adenoviruses 22.0 Viruses

has also hampered etiologic studies. Type 1 3.7 Adenoviruses, 7

At the present, in the absence of Type 2 7.5 all types

epiglottitis or lobar pneumonia in the Types 9.8 Influenza 12

older child, the only way to associate Not typed 10 TypeA 4

H influenzae or S pneumoniae with Enteroviruses 13.6 TypeB 6

lower respiratory tract infection is to Influenza 4.7 Not typed 2

Type A 2.0 Parainfluenza 35

isolate the bacterium from the blood Type B 2.7 Typel 19

or pleural space or directly from the Parainfluenza 24.1 Type2 3

lung by percutaneous aspiration. Be- Type 1 4.1 Type3 13

cause of these problems, the roles of Type 2 8.5 Respiratory syn- 22

these two bacteria as causes of lower Type 3 11.5 cytial virus

respiratory tract infections in children Respiratory syn- 9.5 Miscellaneous 9

are largely unknown. Although stud- cytial virus

9.5 Enteroviruses 3

ies suggest that the organisms are Rhinoviruses Rhinoviruses 3

infrequent causes in the United Other 6.1 Other viruses 3

States, especially when compared Bacteria Mycoplasma pneumo- 15

Group A strepto- 8.8 niae

with viruses and M pneumoniae,

cocci

there is widespread belief, and some Mycoplasma pneu- 1.7 * Roles of other agents, especially

evidence, that they play a major role

S in the increased morbidity and mor-

moniae

Streptococcus pneumoniae and

Haemophllus influenzae, not listed

tality associated with lower respira-

tory tract infections in developing because they are unknown.

countnes.9

The occurrence of acute respira-

tory infections is associated with 5ev-

ROLE OF GROUP A eral important factors: the age of the important and, at least in part, may

STREPTOCOCCUS, M patient, season of the year, clinical explain the decrease in incidence as

PNEUMONIAE, AND syndrome, infecting agent, and the the child gets older.

RESPIRATORY VIRUSES AS extent of contact (crowding). The relative roles by age of viruses,

CAUSES OF ACUTE group A streptococci, and M pneu-

RESPIRATORY TRACT moniae as causes of pharyngitis in

INFECTIONS Upper Respiratory Tract children are shown in Fig 3#{149}11Children

The incidences of total acute re\ younger

infected than

with 2 group

years ofAage are rarely

Much is known of the roles of

group A streptococci,

piratory in two different re

infections which infect primarily-) streptococci

school-aged

M pneumoniae, ports, the Cleveland Family Study1#{176} j children, as does M pneumoniae, but

and viruses as causes of childhood and Chapel Hill day-care studies, are ,/ at a slightly older age. There are also

acute respiratory infections. In most compared in Fig 2.8 It is recognized ( seasonal variations in upper respira-

instances, the isolation of these that there is risk in comparing data tory tract infections caused by var-

agents from the upper respiratory collected under such diverse circum agents. Group A streptococci

tract can be correlated with active stances, but carefully controlled com cause infections in all seasons but

infections; with few exceptions, the parative data are not available. R are generally most common in the

most notable being the group A suIts of both studies show that a#{235}utewinter and spring. The seasonal oc-

streptococcus, they are not isolated respiratory infections are common in currence of viral and M pneumoniae

from the throats of well children. Fur- children, occurring at a rate of four to( acute respiratory infections will be

thermore, specific clinical syndromes nine per year, depending on age anq discussed in more detail.

are associated frequently with spe- contact. Results of both studies indi(.

S cific agents. These associations

been confirmed

have

by accurate serologic

cate that increased contact, either Lower Respiratory Tract

from siblings or in day care, increase

tests that demonstrate specific anti- the incidence. Findings from the day-k The various factors that have been

body responses. care study suggest that seasoning i) associated most commonly with the

pediatrics in review #{149} vol. 9 no. 5 november 1987 PIR 137

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

Respiratory Infections

occurrence of childhood lower respi-

TABLE 4. Bacterial Causes of Acute Respiratory Infections in Children ratory tract infections will be dis-

cussed in more detail. The data and

Agent

illustrations are taken from the

Unusual causes in United States Corynebacterium diphtheriae Chapel Hill studies and are consid-

Bordetella pertussis

ered representative of similar studies

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

reported by others.1214

Legionella pneumophlla

Found only in special circumstances Staphylococcus aureus Age and Gender Incidence. The

Group B Streptococcus age -and gender-specific attack rates

Enterobactenaceae for total lower respiratory tract infec-

Rickettsiae tions and four respiratory syndromes

Common causes are shown in Fig 4 and several im-

Defined role Hemolytic streptococci, group A and portant aspects of lower respiratory

possibly groups C and G tract infections are demonstrated.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae Lower respiratory tract infections are

Undefined role Chiamydia trachomatis common and in this study one of

Haemophllus influenzae

every four or five children younger

Streptococcus pneumoniae

than 1 year of age, on the average,

was taken to the pediatrician be-

cause of a lower respiratory tract in-

fection each year. This rate declined

with age until the late elementary

school ages. Lower respiratory tract

infections occur in more young boys

10 than girls, and this persists through

the lower elementary school ages

both for total lower respiratory tract

4 HOME CARE* infections and the specific syn-

LU Sibs in School dromes. Of the syndromes, croup is

>-

the most likely to occur in boys with 5

a male to female ratio of 1 .73 in 6- to

-I 1 2-month-old infants. As shown in

I the four lower frames of Fig 4, with

07-

the exception of bronchiolitis, the

age-specific attack rates for the din-

LU ical syndromes were different from

Q_ 6- those of total lower respiratory tract

(I) infections and also different from

LU

U)

CARE each other. All syndromes occurred

(I.) 5- less frequently during the first 6

LU months of life. The incidence of bron-

z

chiolitis most nearly resembled the

_J 4- overall incidence of lower respiratory

tract infections, peaking in 6- to 12-

>-.

a: month-old infants and declining

sharply thereafter. Croup peaked in

the second year and pneumonia in

a: the third year. Of all the syndromes,

0. 2- tracheobronchitis was most likely to

U) be found in children after the first few

LU years of life.

a: Association of Respiratory Agents

and Syndromes. The association be-

0 tween respiratory syndromes and in-

fecting agents is well established and

0 I 2 3 4 5 is demonstrated in Fig 5. These data

show associations across all age

AGE (YEARS) groups; with corrections for age,

these associations become more dra-

Fig 2. Comparative incidences of respiratory illnesses in different child care settings. Asterisks matic. Croup was caused most fre-

refer to data from Dingle et al.1#{176}

From Denny et a!.8 quently by the parainfluenza viruses,

PIR 138 pediatrics in review #{149} vol. 9 no. 5 november 1987

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

INFECTIOUS DISEASE

S especially

was associated

type 1 Tracheobronchitis

.

with respiratory syn- 50- VIRUSES

cytial virus, M pneumoniae, and the

influenzae viruses. The cause of

bronchiolitis was most frequently res- 40-

piratory syncytial virus. Respiratory

syncytial virus and M pneumoniae 30

were common causes of pneumonia. L&i

In our studies, the influenza viruses >

20

were not prominent causes of pneu-

monia, as reported by Glezen.15 Influ-

(1) I0-

enza A virus was not isolated as fre-

0

quently by us, probably because of

the relatively insensitive isolation sys- U U U U

tem used. U)

Age Distribution of Lower Respira- I-,

tory Tract Infections Caused by Spe- z GROUP A PTOCOCCI

cific Infecting Agents. As has been ‘Ii 50-

shown, the respiratory infecting

agents are associated to some de-

gree with all respiratory syndromes.

The age-specific incidence of lower

IL 30-

respiratory tract infections caused by

specific agents differs, at times to a

0

marked degree, and is shown in Fig I- 20-

6. In all instances, with the exception z

of the adenoviruses, rates during the Iii I0-

first 3 months of life were lower than 0

in later months. The patterns of the

5 curves for respiratory syncytial virus

Iii

and parainfluenza type 3 were similar

except that respiratory syncytial virus 20’ MYCOPL ASAVA PNEUMONIA (

rates were higher in the first few

years. By comparison, parainfluenza

virus type 1 occurred in slightly older

children, and adenovirus infections U I U U I j

occurred almost exclusively in the <2 25 6-8 9lI 12-141519 20

first 5 years of life. The influenza vi-

ruses occurred commonly in all age

groups. The rates for M pneumoniae

AGE IN YEARS

infections show an entirely different

age distribution; no isolates were Fig 3. Frequency by age of recovery of microbial agents from children with pharyngitis in

made in children younger than 3 Chapel Hill, NC. From Glezen et al.11

months of age and the peak rates

occurred in school-aged children.

Seasonal Occurrence of Syn- background of infections by other winter. As observed earlier, the most

dromes and Agents. The respiratory agents. The tendency of viral agents common causes of pneumonia are

agents, and consequently the asso- not to cause simultaneous epidemics respiratory syncytial virus and M

ciated syndromes, frequently have in a community, as demonstrated pneumoniae but, because these

characteristic seasonal patterns. An here, has been shown by others as agents occur usually in different sea-

example of this (Fig 7) shows the well.15 The general aspects of sea- sons and in different age groups, the

monthly occurrence of various agents sonal occurrence are as follows. seasonal occurrence of pneumonia

in relationship to occurrence of total There is a close association between can differ markedly. Tracheobronchi-

lower respiratory tract infections. the seasonal incidence of bronchioli- tis also occurs in seasonal patterns

Parainfluenza virus type 1 caused a tis and the isolation of respiratory according to the causative agent but

large outbreak in the fall, primarily of syncytial virus, both occurring in the is most closely associated with the

croup. This was followed by a winter winter to early spring. The occur- influenzae viruses which occur in win-

S epidemic of respiratory syncytial virus

disease and a spring outbreak

rence of croup, which is closely as- ter and spring.

sociated with the isolation of the par- Combined Roles of Agents, Age,

caused by influenza virus type b. All ainfluenza viruses, especially type 1, and Season on Attack Rates of Total

of this occurred against a low level is predominantly in the fall and early Lower Respiratory Tract Infections

pediatrics in review #{149} vol. 9 no. 5 november 1987 PIR 139

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

Respiratory Infections

ruses, however, were isolated rarely

in school-aged children, whereas par-

ainfluenza virus type 3 continued to

S

cause some illness in this group. The

fall/winter occurrence of M pneumo-

niae in school-aged children is also

shown, as is the impact in all age

groups of the winter/spring occur-

rence of the influenza viruses.

MALES

FEMALES

ROLE OF VARIOUS RISK

FACTORS ON THE

OCCURRENCE OF ACUTE

RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS

‘U

Risk factors that cause increased

z

incidences and/or severity of respi-

cRo

ratory infections have been identified.

Crowding

Respiratory infections, for the most

part, are spread by direct contact or

large droplets from the respiratory

tract and are thus more likely to occur

during conditions that foster close

contact. This has been demonstrated

for all forms of crowding-number of

siblings, room occupancy, population

density, and probably day-care at-

tendance. The role of day care has

S

not been defined as clearly as is de-

sirable but presently available data

5.

suggest higher incidence figures for

day-care attendees.8 Most crowding

- 16-121-2 2-3 3-5 5-9 would be expected to increase mci-

0-6 YEARS dence primarily but might play a role

AGE

in increasing severity as well in situ-

ations in which crowding is so intense

Fig 4. Age- and gender-specific attack rates for total lower respiratory illnesses and four that the infecting dose of microorga-

respiratory syndromes, 1964 to 1975. Rate for boys is represented by entire column; that for

girls is represented by stippled portion. From Denny and Clyde.

nisms is large. It is speculated that

this might play a role in the increase

in severity of acute respiratory infec-

tions in developing countries.

and Four Respiratory Syndromes. the same to allow comparison of the

The separate effects of the infecting rates of illness and agent isolation

Gender

agent, age and gender of the host, among age groups. Total lower res-

relationship of agents and syn- piratory tract infections and the syn- The role of gender as a risk factor

dromes, and season on the ex- dromes are more common in younger has received little attention. Data sug-

pression of lower respiratory tract children, and the rates of all decline gest only slight and probably mnsignif-

infections in children have been dis- with age. The association of the win- icant differences in incidences be-

cussed. The interactions of these var- ter/spring occurrence of respiratory tween boys and girls for upper res-

ious factors are shown in Figs 8 to syncytial virus with bronchiolitis in piratory tract infections.16 There are

10; data from all 11 years of the younger children is shown clearly, as clear-cut gender differences for acute

Chapel Hill study are presented by is the association of croup and para- lower respiratory tract infections,

month. The impact of yearly and sea- influenza virus type 1 in early fall. with a preponderance of disease oc-

sonal variations in occurrence of Parainfluenza virus type 3 and the curnng in boys, suggesting that the

agents is blunted by presenting the

data in this manner. The scales of the

adenoviruses are the most ubiquitous

of the agents, occurring in most

risk is to increased seventy.2 These

differences may have pathogenetic

5

vertical axis of the three figures are months of the year. The adenovi- significance but are of little help to

PIR 140 pediatrics in review #{149} vol. 9 no. 5 november 1987

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

INFECTIOUS DISEASE

the pediatrician in managing children

with acute respiratory infections. 50 Croup

40

Inhaled Pollutants

Inhaled pollutants have received

much attention in the past few years.

Although studies vary somewhat in

l-

Oz

30

20

10

0

________ Th

‘

_______

Tracheobronchitis

the degree of risk caused by passive

tobacco smoking, both for increased

incidence and for increased severity, Ow

there is increasingly strong evidence z>- 40

that passive smoking is an important O W30 Bronchiolitis

risk factor.17’18 The impact of passive 20

smoking appears to be greatest in 0(1) 10

the child younger than 1 year of age

0< 0

and is related most closely with ma- cr0 Pneumonia

a-

ternal smoking. There is also evi-

dence that wood-burning stoves19

and possibly the use of gas for

cooking2#{176}

are responsible for increas-

ing the risk of acute respiratory infec- RS Para 1 Para 3 M. neu- Adeno- Influenza Other

Virus Virus virus moniae viruses Viruses Viruses

tions.

Fig 5. Associations between principal agents and four respiratory syndromes. Note that almost

Anatomic Abnormalities, Metabolic 50% of croup is caused by parainfluenza type 1 but that all agents share fairly equally in

and Genetic Disease, and tracheobronchitis. RS virus, respiratory syncytial virus; para 1 virus, parainfluenza virus type 1,

Immunologic Deficiencies21 para 3 virus, parainfluenza virus type 3. From Denny and Clyde.2

It is clear that abnormalities such

as tracheoesophageal fistulas, cystic

fibrosis, congenital heart disease,

and immunodeficiency syndromes ing and inhaled pollutants, it has not Social and Economic Factors

are associated to varying degrees been possible to define clearly its

It is difficult, if not impossible, to

with increased risk for respiratory in- role. The recent report of the role of

vitamin A deficiency in increasing risk separate the various social and eco-

fections, both in incidence and sever- nomic factors that may have an im-

ity. It is beyond the scope of this for acute respiratory infections is of

pact on the occurrence of acute res-

review to consider these further. The interest but needs further study to

assess its importance.22 Breast-feed- piratory infections, but low social

role of atopy and/or reactive airways class is linked clearly with increased

in increasing the risk for respiratory ing appears to be important in devel-

nsk.25 Crowding, malnutrition, and in-

infection is controversial. There oping countries in reducing the risk

haled pollutants, all found in low so-

seems to be a relationship between for acute respiratory infections,9 but

cioeconomic classes, especially in

respiratory infections and asthma, the data relating to a protective effect

but the “chicken and egg” relation- of breast-feeding in developed coun-

ship is unclear. The same is true for tries is contradictory. Results of stud-

the relationship between atopy and ies show only small or no reductions To manage uncomplicated

bronchiolitis. It is commonly believed in the incidence of all respiratory in- upper respiratory tract

that the atopic child has more fre- fections but do suggest that the se- infections it is necessary

quent bouts of otitis media and sinu- verity of infections might be de- only to differentiate

sitis, but prospective studies to prove creased in young breast-fed infants.23 streptococcal from

this point have not been reported. The role of “prop feeding” is contro- nonstreptococcal infections.

versial. Early reports indicated that

this was important as a contributing

Nutrition, Including Breast-Feeding factor in otitis media and more severe

lower respiratory tract infections, but developing countries, are contribut-

It seems probable that malnutrition recent data are more conflicting.24 It ing factors. The role of stress, re-

is important in increasing the risk for is clear that the effect of nutrition on ported by Meyer and Haggerty,26 and

the risk for acute respiratory infec- now receiving greater attention,

S acute respiratory

cially in developing

infections,

countnes.9

espe-

Be- tions, including breast and other could be a contributing factor, partic-

cause malnutrition is often associated forms of feeding, needs increased at- ularly with the stress that is associ-

with other risk factors such as crowd- tention. ated with being poor.27

pediatrics in review #{149} vol. 9 no. 5 november 1987 PIR 141

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

Respiratory Infections

If the clinical syndrome, the age and

gender of the patient, and the season

of the year are considered, a good S

estimation of cause can be made; this

Rsspatory Syncytlal virus.. could lead to more precise and effec-

tive use of antibiotics. Suggested

guidelines for the practitioner follow.

These guidelines are designed for the

practice of pediatrics in the United

States and for the “average” patient

seen by most pediatricians. Patients

4

“I . suffering from one or more of the risk

‘U factors described, especially those in

z developing countries, should be man-

‘U

aged accordingly.

0

-J

I

U

0 I!I

0 Croup

0 Par#{252}Wluenza Virus Typ 3

IC

‘I) Most croup is caused by viruses,

5 especially the parainfluenza viruses.

U . Mpneumoniae is an infrequent cause;

‘U 0

Mycopls.ms pnsumonlae other bacteria such as C diphtheriae

I

5 are involved rarely. Because parain-

fluenza virus type 1 the most com-

,

mon cause of croup, is isolated most

I0

frequently in the fall, this is the croup

season. Croup occurs rarely in the

01 1.. Vfruss

. first few months of life and reaches

its peak occurrence in the second

S

lnflusnza

year; it occurs preponderantly in

boys. Most cases of croup are mild

6I2 1-2 2-3 3-5 5-9 9-IS and require only supportive treat-

0-3

3-6 Ys.rs ment, but an occasional child has

AGE findings, although consistent with Ia-

ryngeal obstruction, that require dif-

ferent management. The child with

Fig 6. Age-specific attack rates of lower respiratory tract infections caused by certain agents.

From Denny and Clyde.2

epiglottitis probably is infected with II

influenzae type b and should be

treated accordingly. A rare patient

with laryngeal obstruction suggestive

IMPLICATIONS2 cision when the illness involves the of croup or epiglottitis may have bad-

lower respiratory tract is more com- tenal laryngotracheobronchitis. This

A large proportion of ill children

plex. Because of the lack of quick, clinical syndrome, caused by S au-

seen by the primary care physician

have acute respiratory ailments. reus, S pneumoniae, H influenzae, or

Many of these involve only the upper group A streptococci, was apparently

respiratory tract, and a throat swab common before the advent of anti-

If the clinical syndrome, the microbial agents; our attention was

processed by a rapid technique to age and gender of the

detect group A streptococcal antigen called to it again in 1979, but it has

patient, and the season of been recognized infrequently since

and/or cultured on sheep blood agar the year are considered, a

for the isolation and identification of then. Thus, with few exceptions, the

good estimation of the cause clinician can diagnose croup with din-

group A streptococci is the most im- of acute lower respiratory

portant guide for antibiotic therapy.28 ical and epidemiologic tools and be

tract infections can be made.

reasonably confident that the deci-

At the present time, we recommend

that a rapid diagnostic test be per- sion to withhold antibiotics is correct.

formed first. If the result of this test

is positive, a culture is not done; if easy, and inexpensive methods for Tracheobronchitis

the results are negative, a culture is identifying causative agents in these

done. The decision to treat is made patients, the clinician has only clinical Physicians have long recognized

that a productive cough and rhonchi

5

on clinical grounds with help from and epidemiological tools to aid in the

these laboratory aids. Making this de- decision of whether to use antibiotics. can be present without other findings

PIR 142 pediatrics in review #{149} vol. 9 no. 5 november 1987

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

INFECTIOUS DISEASE

of lower respiratory tract involve-

S ment,

has beenbut clarified

the entityonlytracheobronchitis

recentIy.#{176}The

30

agents involved are viruses and M

pneumoniae. All of the agents we dis-

cuss can cause tracheobronchitis, I0J

20 RESPIRATORY

but respiratory syncytial virus, M

pneumoniae, and the influenza vi-

ruses are most commonly isolated. 40

These agents have definite age and

seasonal patterns, thus dictating the

age of patients with tracheobronchitis

and the seasons when these infec-

tions occur. Respiratory syncytial in-

fection occurs in young children in

winter and spring, the influenza vi-

ruses in all age groups in the winter

and spring, and M pneumoniae in

school-aged

though erythromycin

children in the fall. Al-

and the tetra-

30

20

TJ__

ZNFLUENZAVIRUSTjrn

PARAINFLUENZA

VIRUS

TYPE I

__

So

40

30

20

I0-I&.

0Iii

cydlines are effective against M pneu- INFLUENZA VIRUS TYPE z

moniae infections, supportive treat-

ment is all that is required for most 0 10

children with tracheobronchitis. I OTHER PICORNAVIRUSES ,ADENOVIRUSES

I - - - -

01

. M Diltumorno M horn/n/s

L -

In office practice, of the

common causes of croup,

tracheobronchftis, and

bronchiolitis-

viruses and M pneumonlae-

the only ones requiring

antimicrobial treatment are

those due to

M pneumoniae.

JUL AUG S OCT NOV DEC JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN

1970 1971

Bronchiolitis

Bronchiolitis is the most common

Fig 7. Number of agents isolated by month from children with lower respiratory tract illnesses

lower respiratory tract infection syn- seen in office practice, 1970 to 1971. Note propensity of some agents to cause rather discreet

drome in small children. It is caused outbreaks at time when other agents were present in only small numbers. From Denny and

usually by respiratory syncytial virus, Clyde.2

although all other respiratory agents

can cause wheezing. Bronchiolitis oc-

curs in the winter and spring during vitro and has been reported to ame- with an uncomplicated infection, the

respiratory syncytial virus epidemics liorate illnesses caused by this clinician is justified in withholding an-

in young children. Lower respiratory agent.31 It is not recommended for tibiotics. The role of bacteria in pneu-

tract infections with wheezing in general use at this time. monia, other than M pneumoniae, is

school-aged children in the fall are much less clear, presenting the clini-

frequently related to M pneumoniae. cian with a somewhat different chal-

Pneumonia

This syndrome does not appear to be lenge. Several circumstances that

caused by other bacteria. Manage- Bacteria other than M pneumoniae may suggest methods of manage-

ment of bronchiolitis is supportive in are unusual causes of croup, tra- ment follow. Respiratory syncytial vi-

S most cases; data to support the use

of bronchodilators are lacking. Riba-

cheobronchitis,

children

and bronchiolitis.

with one of these syn-

In rus and the influenza viruses are the

most common causes of pneumonia

virin, a new antiviral agent, is effective dromes, when all other clinical and in young children. The older child with

against respiratory syncytial virus in epidemiologic data are compatible lobar pneumonia probably is infected

pediatrics in review #{149} vol. 9 no. 5 november 1987 PIR 143

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

Respiratory Infections

crobial treatment until recovery or un-

til studies

necessary.

indicate that this

The child with mild pneu-

is not

S

monia, at a time when a respiratory

Virus 5 causing disease common in

other children in the community, can

be safely observed without antibiotic

therapy.

Pneumonia is more difficult

to manage. S pneumoniae

and H influenzae are not

thought to be common

Respiratory Syncytial Viruses

causes in the United States.

Because no diagnostic tests

are available for recognizing

those that do occur unless

the organisms are isolated

from the blood or directly

from the lung or pleural

space, patients with severe

4- pneumonia should receive

antibiotics.

3

o

2 Parainfluenza Virus Type 3

In determining the general applica-

c1 bility of the guidelines, the physician

should keep in mind that most of the

S

2 j Mycoplasma pneumorae

observations discussed were made

in a small city in North Carolina. Cer-

tam correlations, however, have been

constant regardless of where studies

have been performed. Respiratory

2 Influenza Viruses syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus

)1

%J July Aug. Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec. Jon. Feb. Mar. Apr. May June

types 1 and 3, M pneumoniae,

adenoviruses, and the influenza

the

vi-

ruses have consistently been the

MONTH most common infecting agents. The

Fig 8. Monthly attack rates of total lower respiratory tract illnesses, four syndromes, and

infections caused by certain agents in children 0 to 2 years of age. From Denny and 32

S pneumoniae and

H influenzae appear to be

common and important

with S pneumoniae. The presence of suggests the diagnosis. The simulta-

causes of pneumonia in the

significant amounts of pleural fluid neous presence of several children

developing world.

suggests a causative agent other with similar findings in a community

than M pneumoniae or a virus. M usually indicates the community oc-

pneumoniae infections occur in currence of M pneumoniae disease

school-aged children and are usually and simplifies management in similar

characterized by the gradual onset of patients for the duration of the epi- age-related attack rate of agents and

symptoms, notably cough. Pulmo- demic. In the absence of clinical and age-related syndromes and the as-

nary infiltrates are usually of intersti- epidemiologic data suggesting viral sociation of certain agents and partic-

tial or bronchopneumonic character, or M pneumoniae pneumonia, the se- ular syndromes also have been con-

involving

demonstration

one of the lower lobes. The

of high (>1 :1 28) or in-

verity of illness is probably

guide to management;

the best

the child who

sistent, as has the preponderance

lower respiratory tract infections

of

in

5

creasing titers of cold hemagglutinins is severely ill should receive antimi- boys. The epidemiologic aspect most

PIR 144 pediatrics in review #{149} vol. 9 no. 5 november 1987

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

INFECTIOUS DISEASE

variable and most likely to differ

Total Lowsr Ristory ssis

among geographic locations is the

seasonal occurrence of infections

with specific agents. In general,

trends reported here are similar to

those reported by other investigators

in the United States but may differ in

other parts of the world. In the trop-

ics, for example, lower respiratory

I tract infections tend to be more fre-

quent during the rainy season. The

presence of regional laboratories ca-

I pable of identifying the agents caus-

ing current respiratory

in various geographic areas might be

tract

of help to the practicing pediatrician.

infections

I u

1

I Pvslnflusnz.

-

Virus Typ. 3

The Centers for Disease Control has

performed this task for many years

for the United States and reports the

isolation of influenza viruses in Mor-

bidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

. Several laboratories in various parts

of the country report the isolation of

I I Adsnovlru...

: respiratory disease agents in local

01 -

2 klfkmnza Virus.s

communities.

In seems likely that S pneumoniae

1 -

and H influenzae are not major

July A44 SSpt Oct. No Dec. Jan. Fe Apr. May kits

MONTH causes of lower respiratory tract in-

fections in developed countries. This

Fig 9. Monthly attack rates of total lower respiratory tract illnesses, four syndromes, and may not be true in developing coun-

infections caused by certain agents in children 2 to 5 years of age. From Denny and 2 tries, and clinicians caring for children

in these areas should be aware of the

role these two bacteria may play in

the excessive morbidity and mortality

among children with lower respiratory

11

tract infections, especially pneu-

monia.

I

2 Rss*ty Syncyti& Virus

1

0

REFERENCES

V

...%

I 2 P&alnfkjsnzs VIrus Type 1

‘U 1 . Henderson FW, Collier AM, Sanyal MA, et

al: A longitudinal study of respiratory vi-

-I 0 --

ruses and bacteria in the etiology of acute

I 2 P&ainfkisnz* Virus Type 3

C.) otitis media with effusion. N EngI J Med

1 982;306:1 377

80 0 - - -

Cl)

‘U

2L

3, Mycoplssins pnwnonla

2. Denny FW, Clyde WA Jr: Acute lower

respiratory tract infections in nonhospital-

ized children. J Pediatr 1986;1O8:635

U) 3. Loda FW, Glezen WP, Clyde WA Jr: Res-

4

U Ano*uss I piratory disease in group day care. Pedi-

atrics 1972;49:428

L I

1 4. Brasfield DM, Stagno S, Whitley RJ, et al:

I Infant pneumonitis associated with cyto-

megalovirus, chlamydia, Pneumocystis,

i and Ureaplasma: Follow-up. Pediatrics

!iy __. I 1987;79:76

Au Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec. Jait Feb Mar. Apr. May June .: . Komaroff AL, Aronsen MD, Pass TM, et

MONTH al: SerOlOgiC evidence of chlamydial and

i mycoplasmal pharyngitis in adults. Sci-

ence 1983;222:927

Fig 10. Monthly attack rates of total lower respiratory tract illnesses, four syndromes, and 6. Gerber MA, Ryan RW, Tilton RC, et al:

infections caused by certain agents in children 5 to 9 years of age. From Denny and Clyde.2 Role of Chlamydia trachomatis in acute

pediatrics in review #{149} vol. 9 no. 5 november 1987 PIR 145

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

Respiratory Infections

pharyngitis in young adults. J Clln Micro- 1981144:433 risk of respiratory disease and diarrhea in

biol 1984;20:993

7. Schwartz RH, Shulman ST: Group C and

group G streptococd: In-office isolation

15. Glezen WP: Viral pneumonia

and result of hospitalization.

1983;147:765

as a cause

J Infect Dis

23.

children with mild vitamin A deficiency.

J Clin Nutr 1 984;40:1090

Frank AL, Taber LH, Glezen WP, et al:

Am

S

from children and adolescents with phar- 1 6. Monto AS, lilman BM: Acute respiratory Breast-feeding and respiratory virus infec-

yngitis. Clin Pediatr 1986;25:496 illness in an American community: The tion. Pediatrics 1982;70:239

8. Denny FW, Collier AM, Henderson FW: Tecumseh study. JAMA 1974;227:164 24. Gordon AG: Respiratory and gastrointes-

Acute respiratory infections in day care. 1 7. Health effects of environmental tobacco final infections and prop feeding. Int J Ep-

Rev Infect Dis 1986;8:527 smoke exposure, in The Health Conse- idemiol 1986;15:138

9. Pio A, Leowski J, ten Dam HG: The mag- quences oflnvoluntary Smoking: A Report 25. Gardner G, Frank AL, Tabor LH: Effects

nitude of the problem of acute respiratory of the Surgeon General, US Department of social and family factors on viral respi-

infections, in Douglas RM, Kerby-Easton of Health and Human Services. Rockville, ratory infection and illness in the first year

E (eds): Acute Respiratory Infections in Maryland, Pub1c Health Service, 1986, pp of life. J Epidemiol Community Health

Childhood. Adelaide, Australia, 1kiversity 17-118 1984;38:42

ofAdelaide, 1985, pp3.-16 1 8. Committee on Passive Smoking, Board of 26. Meyer RJ, Haggerty RJ: Streptococcal in-

10. Dingle JH, Badger GF, Jordan WS Jr: Ill- Environmental Studies and Toxicology, faction in families: Factors affecting mdi-

ness in the Home. Cleveland, Press of National Research Council: Effects of Ex- vidual susceptibility. Pediatrics 1962;

Western Reserve University, 1964, pp 33- posure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke 29:539

96 on Lung Function and Respiratory Symp- 27. Graham JMH, Douglas AM, Ryan P:

1 1 . Glezen WP, Clyde WA Jr, Senior RJ, et al: toms in Environmental Tobacco Smoke: Stress and acute respiratory infection. Am

Group A streptococci, mycoplasmas, and Measuring Exposures and Assessing J Epidemiol 1986;124:389

viruses associated with pharyngitis. JAMA Health Effects. Washington, DC, National 28. Hamnck RI: The throat culture reconsid-

1967;202:1 19 Academy Press, 1 986, pp 202-209 ered. J Pediatr 1986;108:416

12. Foy HM, Cooney MK, Maletzky M, et al: 19. Honicky RE, Osborne JS III, Akpom CA: 29. Jones A, Santos JI, Overall JC: Bacterial

Incidence and etiology of pneumonia, Symptoms of respiratory illness in young tracheitis. JAMA 1979;242:721

croup and bronchiolitis in preschool chil- children and the use of wood-burning 30. Chapman RS, Henderson FW, Clyde WA

dren belonging to a prepaid medical care stovesfor indoor heating. Pediatrics 1985; Jr, et ai: The epidemiology of tracheobron-

group over a four-year period. Am J Epi- 75:587 chitis in pediatric practice. Am J Epidemiol

demiol 1983;97:80 20. Melia RJW, Florey CV, Altman DG, et ai: 1981 ;1 14:786

13. Monto AS, Cavallaro JJ: The Tecumseb ASSOcIatIOn between gas cooking and 31. Hall CB, McBride JT, Walsh EE, et al:

study of respiratory illness: II. Patterns of respiratory disease in children. Br Med J Aerosolized nbavirin treatment of infants

occurrence of infection with respiratory 1977;2:149 with respiratory syncytial virus infection: A

pathogens, 1965-1969. Am J Epidemiol 21 Strope

. GL, Stempel DA: Risk factors as- randomized double-blind study. N EngI J

197194:280 sociated with the development of chronic Med 1983;308:1443

14. Frank AL, Taber LH, Wells CR, et al: Pat- lung disease in children. Pediatr Clln North 32. Denny FW, Clyde WA Jr: Acute respiratory

tems of shedding of myxoviruses and par- Am 1 984;31 :757 tract infections: An overview. Pediatr Res

amyxoviruses in children. J Infect Dis 22. Sommer A, Katz J, Tarwatjo I: Increased 1983;17:1 026

S

Advances in Pediatrics

A number of advances in behavioral and development pediatrics have occurred

during the last 20 years that have changed pediatric practice. They should be added

to the list of major advances by Dr Rapkin published last year(Pediatr Rev 1987;8:248).

Infant Temperament

The concept of infant temperament was formalized by Chess, Birch, and Thomas

and popularized for pediatrics by Dr Carey. There are nine categories of temperament

(activity level, rhythmicity or regularity of bodily functions, approach or withdrawal,

adaptability, intensity of reaction, threshold of responsiveness, quality of mood,

distractibility, and attention span and persistence). From this there has been a

characterization of the difficult child: one who shows irregularity of bodily functions,

intensity of reaction (of the negative kind), tendency to withdraw from new stimuli,

and nonadaptability. The recognition that these characteristics were not the mother’s

fault but were the result of an innate temperament has led to an understanding among

parents that they are not to blame for the difficult child and has led to better

understanding of how to adapt child-rearing practices to such children. (A. Zisman,

MD, Spring Valley, NY)

PIR 146 pediatrics in review #{149} vol. 9 no. 5 november 1987

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

Acute Respiratory Infections in Children: Etiology and Epidemiology

Floyd W. Denny

Pediatrics in Review 1987;9;135

DOI: 10.1542/pir.9-5-135

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/9/5/135

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or in its

entirety can be found online at:

https://shop.aap.org/licensing-permissions/

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://classic.pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/reprints

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

Acute Respiratory Infections in Children: Etiology and Epidemiology

Floyd W. Denny

Pediatrics in Review 1987;9;135

DOI: 10.1542/pir.9-5-135

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on

the World Wide Web at:

http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/9/5/135

Pediatrics in Review is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1979. Pediatrics in Review is owned, published, and

trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca, Illinois, 60143.

Copyright © 1987 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0191-9601.

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ by guest on October 22, 2018

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- OpenStax - Psychology - CH15 PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERSДокумент42 страницыOpenStax - Psychology - CH15 PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERSAngelaОценок пока нет

- Leadership PresentationДокумент10 страницLeadership Presentationapi-404415990Оценок пока нет

- NSTP1 MODULE 3 Disaster Awareness Preparedness and ManagementДокумент16 страницNSTP1 MODULE 3 Disaster Awareness Preparedness and Managementrenz dave100% (2)

- Wa0016Документ3 страницыWa0016Vinay DahiyaОценок пока нет

- Grain Silo Storage SizesДокумент8 страницGrain Silo Storage SizesTyler HallОценок пока нет

- Technology For Teaching and Learning 2 OBE SyllabusДокумент9 страницTechnology For Teaching and Learning 2 OBE Syllabusjesreel canalОценок пока нет

- SRV SLB222 en - 05062020Документ2 страницыSRV SLB222 en - 05062020Nguyen ThuongОценок пока нет

- Injection MouldingДокумент241 страницаInjection MouldingRAJESH TIWARIОценок пока нет

- Guidelines For Forensic Report Writing: Helping Trainees Understand Common PitfallsДокумент54 страницыGuidelines For Forensic Report Writing: Helping Trainees Understand Common PitfallsNorfolk Journal100% (1)

- TFALL CaseStudy-Chandni+Chopra 072020+Документ5 страницTFALL CaseStudy-Chandni+Chopra 072020+Luis Gustavo Heredia VasquezОценок пока нет

- Power of AttorneyДокумент10 страницPower of AttorneyRocketLawyer82% (17)

- Refrigerator: Service ManualДокумент119 страницRefrigerator: Service ManualMihaela CaciumarciucОценок пока нет

- INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY NotesДокумент6 страницINTELLECTUAL DISABILITY Notesshai gestОценок пока нет

- UM-1D User ManualДокумент30 страницUM-1D User ManualAhmedBalaoutaОценок пока нет

- Equine Anesthesia Course NotesДокумент15 страницEquine Anesthesia Course NotesSam Bot100% (1)

- Pakeha (Maori For European New Zealanders) Thinking, in That They Tend To Go OutwardsДокумент11 страницPakeha (Maori For European New Zealanders) Thinking, in That They Tend To Go OutwardsDwi RahayuОценок пока нет

- ScienceДокумент17 страницScienceTambong HailyОценок пока нет

- APPSC Calender Year Final-2017Документ3 страницыAPPSC Calender Year Final-2017Krishna MurthyОценок пока нет

- S:/admin/mpi/MP1169 - Amaia Skies Samat/000 - ACTIVE DOCUMENTS/09 - SPECS/2013-07-23 - Design Development/04-Plumbing/15050Документ19 страницS:/admin/mpi/MP1169 - Amaia Skies Samat/000 - ACTIVE DOCUMENTS/09 - SPECS/2013-07-23 - Design Development/04-Plumbing/15050Lui TCC BariaОценок пока нет

- Mbs KatalogДокумент68 страницMbs KatalogDobroslav SoskicОценок пока нет

- Ifm Product Innovations PDFДокумент109 страницIfm Product Innovations PDFJC InquillayОценок пока нет

- Afforestation Powerpoint For NandniДокумент9 страницAfforestation Powerpoint For NandniFagun Sahni100% (1)

- SET 2022 Gstr1Документ1 страницаSET 2022 Gstr1birpal singhОценок пока нет

- Medical Representative Healthcare Sales in Fort Myers FL Resume Greg HejlikДокумент2 страницыMedical Representative Healthcare Sales in Fort Myers FL Resume Greg HejlikGregHejlikОценок пока нет

- 2017 THE BLUE WAY Visual PDFДокумент54 страницы2017 THE BLUE WAY Visual PDFAlex KappelОценок пока нет

- Assignment 2 - CE 669A - 22-23Документ1 страницаAssignment 2 - CE 669A - 22-23Sonam MeenaОценок пока нет

- Toaz - Info Fermentation of Carrot Juice Wheat Flour Gram Flour Etc PRДокумент17 страницToaz - Info Fermentation of Carrot Juice Wheat Flour Gram Flour Etc PRBhumika SahuОценок пока нет

- Pentacam Four Maps RefractiveДокумент4 страницыPentacam Four Maps RefractiveSoma AlshokriОценок пока нет

- API 614-Chapter 4 DATA SHEET Dry Gas Seal Module Si Units: System Responsibility: (2.1.2)Документ10 страницAPI 614-Chapter 4 DATA SHEET Dry Gas Seal Module Si Units: System Responsibility: (2.1.2)tutuionutОценок пока нет

- WT Chapter 5Документ34 страницыWT Chapter 5Wariyo GalgaloОценок пока нет