Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Ecosoc:: Regulation of Cryptocurrency and The Fight Against Terrorism & Money Laundering

Загружено:

safaafОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Ecosoc:: Regulation of Cryptocurrency and The Fight Against Terrorism & Money Laundering

Загружено:

safaafАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

ECOSOC:

Regulation of Cryptocurrency

and the fight against Terrorism

& Money Laundering

United Nations Economic & Social Council #1

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

Index

1. Introduction to the Study Guide

2. Committee introduction

3. Topic one: The Regulation of Cryptocurrency

1. Introduction to the topic

2. History

3. The potential of cryptocurrencies

4. New challenges

5. Challenges for States

6. Regulation efforts

7. Questions a resolution must answer (QARMA)

8. Recommended reading

9. Bibliography

4. Topic two: The fight against Money Laundering and the Funding of Terrorism

1. Introduction

2. Focusing on the matter

3. Where do terrorist organisations get their money from?

4. How do terrorist transfer funds?

5. How much does a terrorist operation cost?

6. What are governments doing to stop terrorist financing?

7. What are some of the difficulties with tracking down terrorist financiers?

8. How can governments more effectively combat terrorist financing?

9. International legal instruments

10. Questions a resolution must answer (QARMA)

11. Bibliography

United Nations Economic & Social Council #2

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

1. Introduction to the Study Guide

Dear Delegates,

It is a pleasure to welcome you to the 2018 AUMUN Conference.

The following pages intend to guide you in the research of the topics that will be debated at AUMUN

2018 in committee sessions. Please note this guide only provides the basis for your investigation. It

is your responsibility to find as much information necessary on the topics and how they relate to the

country you represent. Such information should help you write your Position Paper and to stay in

character at all times.

The more information and understanding you acquire on the two topics, the more you will be able to

influence the Resolution writing process through debates (formal and informal caucuses), and the

AUMUN experience as a whole. Please feel free to contact us if and when you face challenges in

your research or formatting your Position Papers.

We encourage you to learn all you can about your topics first and then study your country with

regard to the two selected topics:

Topic 1: The regulation of cryptocurrencies.

Topic 2: The fight against money laundering and the Funding of Terrorism.

Please remember that all committee’s members need to be well versed and ready to debate both

topics.

We strongly believe that this new approach at treating international urgent topics, directly studying

and reading from the very first and most reliable sources will bring a completely different preparation

from our delegates. Having the possibility of working on official documents will give you the

opportunity to immediately recognize authoritative sources, giving you a great heads-up on how to

further research matters that interest you for your own personal gain or for a commitment-based

work.

Enjoy researching and writing your Position Papers.

We look forward to seeing you at the Conference!

Your chairs Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

United Nations Economic & Social Council #3

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

2. Committee introduction

The Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) is one of the six main organs of the United Nations

established in Chapter X of the United Nations in General Assembly in 1945. ECOSOC is the

principal body for coordination, policy review, policy dialogue and recommendations on economic,

social and environmental issues. It is also for implementation of the internationally agreed

development goals. ECOSOC consists of 54 Members of the United Nations elected by General

Assembly, out of which eighteen members of ECOSOC shall be elected each year for a term of three

years. A retiring member shall be eligible for immediate re-election. Each member of ECOSOC shall

have one representative. Partnership with more than 3,900 non-governmental Organisations play as

the status of the observers resolved related economic and social issues (Article 61). ECOSOC meets

for four weeks sessions each July and hold several regular meetings with professionals, experts, and

NGOs. ECOSOC engages a wide variety of stakeholders in the dialogue on sustainable development

through a programmatic cycle of meetings. It also provides a forum on a range of issues outlined in

the United Nations Charter X especially from Articles 62 to 66 in which detail the functions and

powers of ECOSOC as following:

1. ECOSOC may make or initiate studies and reports with respect to international

economic, social, cultural, educational, health, and related matters and may make

recommendations to any such matters to the General Assembly, to the Members of

the United Nations and to the specialised agencies concerned (Article 62).

2. ECOSOC may furnish information to the Security Council and shall assist the Security

Council upon its request (Article 65).

3. ECOSOC may perform services at the request of Members of the United Nations and

at the request of specialised agencies with the approval of the General Assembly

(Article 66).

Mandate:

ECOSOC serves as the central mechanism for the activities of the UN system and its

specialised agencies, supervises the subsidiary and export bodies in the economic, social

and environmental fields. At the 2005 Word Summit, the ECOSOC mandated a biennial

Development Cooperation Forum (DCF). It has been tasked to promote the integration of

the economic, social and environmental aspects of sustainable development. Since 2014,

ECOSOC focused on the sustainable urbanisation. The agenda of 2014 also focuses on

United Nations Economic & Social Council #4

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

youth employment and expanding the voice of youth that further achieve the Millennium

Development Goals and shape the post-2015 development agenda. In the meantime of

strengthening funding methods from increasing investment and reforming taxation, still

committed to sustainable development, gender equality and health issues.

United Nations Economic & Social Council #5

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

3. Topic one: The Regulation of Cryptocurrency

1. Introduction to the topic

Cryptocurrency is commonly defined as “any form of currency that only exists digitally, that usually

has no central issuing or regulating authority but instead uses a decentralised system to record

transactions and manage the issuance of new units” (Merriam-Webster, 2018).

The trick about cryptocurrencies is the blockchain technology. It allows for a system where every

user has access to the ledger of transactions. This means that the account is verified among the

users, without the need for an authority to keep track of the transactions and create trust in the

system. At the same time, it allows users to remain in relative anonymity, as even though there is an

accessible record of all transactions, it often requires vast resources and determination to track the

transaction to a real life person (Hałaburda and Sarvary, 2016). Both the decentralised character and

anonymity of the system carry some advantages but also some risks for individual states and the

international community. The controversy surrounding cryptocurrencies leads states to adopt

different strategies in approaching them. While some states such as the US allow cryptocurrencies

to flourish, other states such as Algeria ban them altogether.

Given that cryptocurrencies defy national borders, this discrepancy presents a challenge for the

international community. How to find a reasonable compromise, which would balance the

advantages and disadvantages? The following pages should provide you with some basic

information needed to eventually answer this question.

2. History

The first one to envision ledgers verified by users was the sci-fi writer H. G. Wells in the 1930’s. As

the Internet started developing in the late twentieth century, the idea was popularised among the

online community. Eventually, in 2008 someone under pseudonym Sakashi Nakamoto published a

paper outlining the blockchain technology (Campbell-Verduyn, 2018). It was proposed as a means

to solve the problem of high transaction costs and the need for anonymity connected to trading on

the Internet. Although it is not clear who Sakashi Nakamoto is or was, the paper started circulating

and in 2009, Bitcoin was created based on this idea. To this day, Bitcoin largely remains the most

popular cryptocurrency and it is this paper’s main focus, except where otherwise provided.

United Nations Economic & Social Council #6

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

The blockchain technology slowly started gaining attention and other also cryptocurrencies were

created. The first main public event is connected to the WikiLeaks affair of 2011. After revealing

classified information relating to the US involvement in Afghanistan, many banks and financial service

providers refused to process donation payments to WikiLeaks. In reaction, Julian Assange,

WikiLeaks founder, announced that the platform would start accepting donations in Bitcoin

(Campbell-Verduyn, 2018). Despite the media attention, cryptocurrencies remained restricted to the

online geek community. This started changing in 2013 as Bitcoin began to be mentioned in the

media in relation to the Silk Road, an online market for illegal services. At the same time, also

positive features of cryptocurrencies surfaced, such as the alternative means to controversial

quantitative easing of central banks after the financial crisis of 2008 (Campbell-Verduyn, 2018).

Thanks to the media attention, it started to be an interesting speculative investment opportunity

(Hałaburda and Sarvary, 2016). The exchange value of Bitcoin kept rising and falling but at the end

of 2013 it reached 1200 USD. In relation to the initial value of below 15 USD in the beginning of

2013, it is indeed astonishing (Hałaburda and Sarvary, 2016).

With the rise of public awareness, cryptocurrencies began to be incorporated to the global

economy. More service providers, such as AirBnB or eBay started accepting Bitcoin as a possible

means of payment (Campbell-Verduyn, 2018). Alongside this development, policy makers became

interested in regulating cryptocurrencies. In 2013, the US Senate held a hearing on Bitcoin. The

potential risks were stressed but overall, the positive side prevailed, and the hearing was not

followed by any regulation. Other countries took a different approach. China banned its banks and

other financial institutions from using cryptocurrencies. Vietnam made use of cryptocurrencies illegal.

(Hałaburda and Sarvary, 2016). In this context, it is worth reviewing the potential advantages and

disadvantages of cryptocurrencies.

3. The potential of cryptocurrencies

There are some obvious advantages of cryptocurrencies. They are resistant to counterfeit and

represent a solution to the double spending problem - it is clear where each Bitcoin is and it cannot

be spent twice. Other advantages relate to its accessibility and the role that cryptocurrencies could

play in elevation from poverty. Providing people with cheap and accessible basic financial services is

one of the ways. Having a Bitcoin wallet instead of an expensive credit card could provide an

alternative to small businesses and individuals in less developed economies. In addition, Bitcoin can

provide a cheap way to send remittances, on which the economies of some developing countries

are relatively dependent. This is important as remittances are generally correlated to economic

development in the receiving countries. Currently, the high costs of processing remittance payments

is attributed to underdeveloped financial systems, lack of access to banking services and insufficient

United Nations Economic & Social Council #7

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

market transparency. These problems could be addressed through an increased use of

cryptocurrencies.. Nowadays, the massive spread of smartphones has already made mobile

payments very attractive, with cryptocurrencies possibly following the same development (Trautman

and Harrell, 2017).

4. New challenges

Naturally, there are also some drawbacks in the Bitcoin system. The ledger is updated by the so

called miners and in the process a considerable amount of computational power is necessary, which

relates to high energy consumption. Some cities start to voice concerns, with New York State

Department of Public Service reporting that “these companies [miners] are using extraordinary

amounts of electricity – typically thousands of times more electricity than an average residential

customer would use” (Armstrong, 2018). The Department is also linking Bitcoin mining to rising cost

of energy for regular residents (Armstrong, 2018). With Bitcoin’s energy bill exceeding that of Austria,

a part of the Bitcoin community is also worried about the sustainability and carbon footprint of the

system and is trying to think of alternative solutions (Digiconomist, 2018).

Another concern for the Bitcoin community is the potential for a monopoly. When miners compete

for the reward, only the first miner to validate the transaction receives it. This means that all others

incur a cost but do not get the reward, which is why being a lone miner is risky. Instead, miners have

the incentive to join a so called mining pool to share the costs and rewards with each other. In case

such a mining pool reached a share of 51% of the validation operations in the whole market, the

whole system would be at mercy of a single entity capable of influencing the whole ledger and

everybody’s money. This risk is called the “51% attack”. In 2014, GHash.io, one of the leading

mining pools, was reported to have reached over the 51% of the mining power in the network. The

Bitcoin community became worried. Even though all actors had the incentive to upkeep the system,

the element of independent control was suddenly gone and a summit of key Bitcoin figures, mining

hardware manufacturers and biggest mining pools was organised to address the problem. GHash.io

made a voluntary pledge not to exceed a 40% limit and encouraged others to do the same. The

summit resulted in the creation of a committee run by GHash.io to address the problem more

permanently (Coindesk, 2014). Some see this example as a verification of the self-regulatory

potential of cryptocurrencies. Others point out instances of other cryptocurrencies which are facing

problems as well. In May 2018, Bitcoin Gold, the 26th largest cryptocurrency, was under a 51%

attack and a worth of 18,6 million USD was stolen (CCN, 2018).

There are also challenges relating more to the economic nature of the system. Bitcoin creators

wanted to install a scarcity element into the system and ensured a finite supply of Bitcoins. As the

United Nations Economic & Social Council #8

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

amount of transactions rises, a deflationary pressure might be created and prices could be pushed

down. Other cryptocurrencies tried to address this issue by regularly emitting a quantity of the

currency. However, it is challenging to manage the supply exactly right to prevent both inflation and

deflation. (Hałaburda and Sarvary, 2016). In addition, it starts to resemble the activities of the central

bank which defeats the main characteristic of a cryptocurrency.

Finally, cryptocurrencies are often considered to be a very risky financial investment. Not being

backed by any central authority or any underlying fundamentals to guide the price, they can be quite

volatile, making them into a candidate for the next financial bubble (UN, 2017) A case in point is

Bitcoin by the end of 2017, when it lost almost half of its value (Business Insider, 2017). If

cryptocurrencies become more embedded in global economy, the risk that individual holders face

could spread into the broader financial sector. Given the increasing interconnectedness of the world,

this could be a matter of concern to the international community. This leads us to consider the risks

of cryptocurrencies from the point of view of states.

FIG. 1: BITCOIN ENERGY CONSUMPTION INDEX, DIGICONOMIST, 2018

Czech Republic Chile Austria Bitcoin Philippines Venezuela

Finland

United Nations Economic & Social Council #9

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

5. Challenges for States

While some risks present an immediate challenge, some are more remote. One of the purely

theoretical risks at this point is the threat that cryptocurrencies present to the financial stability and

monetary policy of the state. If cryptocurrencies become more popular, they could start to compete

with the traditional banking system, threatening with the loss of control over money supply and the

lender-of-last-resort capability (Sotiropoulou and Guégan, 2017). Again, the volume of

cryptocurrency transactions so far is nowhere near the level where it could present a systemic threat

(He et al., 2016).

A more imminent problem often mentioned in relation to cryptocurrencies is the funding of illegal

activity. Although, it is true that all transactions are recorded, Bitcoin wallets, through which

transactions are made, can be created without the supervision of any financial institution. Thus,

users are able to create their own financial products which makes any supervision or tracing quite

complicated (Doles Silva, 2017). This limits the ability of state authorities to prevent funding illegal

activities such as drug trafficking or organised crime, creating also a transboundary problem. This

risk is not hypothetical. As mentioned earlier, Bitcoin was chosen for its anonymity as a preferred

means of payment on the dark web server, Silk Road. Estimates from early 2018 say that a quarter

of Bitcoin users and a half of all Bitcoin transactions are related to illegal activities (Foley et al. 2018).

Another challenge is that cryptocurrencies can be used to circumvent international economic

instruments such as sanctions or capital controls. By bypassing the traditional payment system,

people were able to purchase Bitcoins and then obtain otherwise heavily regulated or unavailable

foreign exchange online. Such cases were reported in China, Venezuela, Cyprus and Greece (He et

al., 2016).

Cryptocurrencies are also problematic when in comes to taxation. Transactions taking place across

borders and without the need to reveal one’s identity involve the temptation not to be reported and

the states lack effective means of enforcement of tax evasion rules (He et al., 2016). Some say that

cryptocurrencies should be taxed just like investment into other financial assets (Dabrowski and

Janikovski, 2018)

6. Regulation efforts

Keeping in mind the growing popularity of cryptocurrencies in the market and the amount of

resources necessary to dismantle the system, there are benefits to be gained from international

cooperation. Why are international/global standards so necessary? In case of national differences,

given the transboundary nature of cryptocurrencies, there is a risk of “regulatory arbitrage or flight to

United Nations Economic & Social Council #10

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

unregulated safe havens” (FATF, 2018b). For any measures to be effective, they need to be applied

universally. The table below shows that this is not the case at this point in time.

FIG 2: G20 REPORT, FATF, 2018B:

Measures currently applied Countries

Prohibition (on issue/use/dealing/settling of virtual

China, India, Indonesia

currencies/crypto-assets)

Regulation of intermediaries/exchanges and others Australia, France, Germany, Italy,

(using of existing AML/CFT regulation) Japan, Switzerland, US

Suspicious Transaction Reporting Only Argentina, South Africa

Brazil, Canada, EU, Mexico, Netherlands, Russia,

Preparing laws of regulations

Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Spain, Turkey, UK

To address the issue, the first step would be to solve the definitional problem. Is Bitcoin a currency

or an asset? Clarifying this is important for subjecting cryptocurrencies to the right regulatory

framework. The approaches that individual countries take differ significantly. While the French Central

Bank considers cryptocurrencies rather as an asset, Japan created a special new legislative

category and the Financial Action Task Force uses the phrase “virtual currencies/crypto-assets”.

Another challenge is asserting jurisdiction over a particular transaction or a wallet owner. Given that

the transactions cross borders within a split second, it might get complicated. Even when jurisdiction

is determined, a barrier of receiving information from abroad might have to be dealt with

(Sotiropoulou and Guégan, 2017).

Once these challenges are solved, it is worth considering what part of the system should be

regulated. Looking at Bitcoin, in theory, there are three options: the Bitcoin system, the uses of

Bitcoin and the participants. The Bitcoin system itself is difficult to regulate as there is no institution

to address the regulation to. Instead, there are miners and developers, mostly of unknown identity.

The possibilities of the state are therefore mostly limited to monitoring the system and providing

warnings of potential problems with the blockchain technology. Getting back to the “51% attack”, it

seems that the Bitcoin community is trying to build up its own resilience to problems and it is hard to

imagine the role of the state or intergovernmental institution in this environment.

United Nations Economic & Social Council #11

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

FIG 3: VIRTUAL CURRENCIES/CRYPTO-ASSETS REGULATION IN G20 PARTICIPANTS (G20

REPORT, FATF, 2018B):

Preparing laws or regulations

Regulation on intermediaries /excharges

Prohibition (on issue /use/dealing/settling)

Suspicious Transactions Reporting only

The state could be more active when it comes to the uses of Bitcoin. This relates back to funding of

illicit activities. So far, one of the most active entities in standard-setting in this area was the Financial

Action Task Force (FATF). This intergovernmental organisation is tasked with developing

recommendations to combat money laundering and terrorism funding (FATF, 2018a). Their

recommendations relating to cryptocurrencies mostly consists of the regulation of “gatekeepers”,

namely entities providing the exchange services from traditional-to crypto-currencies. The FATF

recommends that they should be covered by the same anti-money laundering rules and that the

“gatekeepers” should be responsible for preventive measures and reporting suspicious money flows

(He et al., 2016). The list of recommendation also includes customer due diligence (verifying

customers) when entering into business and exchanging larger amounts of cryptocurrencies. The

FATF recommends tracking IPs’ or national identity number, always in accordance with national

privacy standards (FATF, 2015). At the same time, the FATF did not advise for regulating the users

and the transactions serving for purchase of goods and services (He et al., 2016). The problem with

that is that if cryptocurrencies gain more popularity, the need to exchange money will lower and for

United Nations Economic & Social Council #12

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

the regulation to remain effective it will need to target participants entirely within the system, such as

wallet providers.

The European Banking Authority (EBA) has also been quite active in issuing recommendations. To

face the immediate risk, the EBA recommended for countries to discourage its financial institutions

from buying or holding cryptocurrencies. In addition, it recommended for the EU Anti Money

Laundering Directive to cover also cryptocurrency transactions (He et al., 2016). Last May some of

these recommendations were included in the 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive which passed

through the European Parliament. It now subjects two types of actors to regulation: cryptocurrency

exchanges and wallet providers (EU, 2018).

The last option is to regulate the participants in the system. Such regulation could relate to customer

protection with rules such as a disclosure of irreversibility of transactions, even in case of an error or

theft, thereby making sure that the participants are aware of the risks. Some countries are also

experimenting with licensing cryptocurrency exchange platforms in order to improve customer

protection. Either they are subjecting them to existing licensing standards for financial service

providers or creating new licensing regimes specific for cryptocurrencies.

What is certain is that cryptocurrencies are an issue worth addressing on the ECOSOC forum, as it

provides an opportunity to coordinate activities among states. This leads to a more effective

approach whether in harnessing the benefits of cryptocurrencies for the benefit of humanity or

combating the risks in order to protect it. To open the debate on possible recommendations, at least

the following questions need to be addressed in a resolution.

7. Questions a resolution must answer (QARMA)

1. Should cryptocurrencies be treated as an asset, a currency or should they have their own

special category?

2. What is the consensus on the existence and severity of risks connected to cryptocurrencies?

3. What should be the common standards of use of cryptocurrencies and what is the best way to

address the risks?

8. Recommended reading

FATF (2015): Guidance For a Risk-based Approach To Virtual Currencies. Available at:

http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Guidance-RBA-Virtual-Currencies.pdf

United Nations Economic & Social Council #13

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

- More detailed information about the FATF recommendations, including the policies of

selected states.

Dabrowski M and Janikowski L (2018): Virtual currencies and central banks monetary policy:

challenges ahead. EU, Directorate-General for Internal Policies. Available at:

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/149900/CASE_FINAL%20publication.pdf

- An extensive analysis requested by the European Parliament, detailing the opportunities

and risks of cryptocurrencies.

Digiconomist (2018): Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index. Available at:

https://digiconomist.net/bitcoin-energy-consumption

- Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index, a good source for estimates on energy consumption

and carbon footprint of mining, and possible alternatives

9. Bibliography

1. Armstrong S (2018) The fightback against the bitcoin energy guzzlers has begun. Wired UK, 31 July.

Available at: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/bitcoin-mining-energy-consumption-new-york

(accessed 1 September 2018).

2. Campbell-Verduyn M (2018) Bitcoin and Beyond: Cryptocurrencies, Blockchains, and Global

Governance. Routledge, New York, USA.

3. CCN (2018) Bitcoin Gold Hit by Double Spend Attack, Exchanges Lose Millions. Available at:

https://www.ccn.com/bitcoin-gold-hit-by-double-spend-attack-exchanges-lose-millions/ (accessed 3

September 2018).

4. Corcoran K (2017) Bitcoin heads into Christmas on a slump. Business Insider UK. Available at:

http://uk.businessinsider.com/bitcoin-price-value-slumping-on-christmas-morning-2017-12 (accessed

16 August 2018).

5. Dabrowski M and Janikowski L (2018) Virtual currencies and central banks monetary policy:

challenges ahead. EU, Directorate-General for Internal Policies. Available at: http://

www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/149900/CASE_FINAL%20publication.pdf

United Nations Economic & Social Council #14

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

6. Digiconomist (2018) Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index. Available at: https://digiconomist.net/

bitcoin-energy-consumption (accessed 3 September 2018).

7. Doles Silva (2017) Cryptocurrencies and International Regulation. UNCITRAL 50th Anniversary

Congress Papers. Available at: https://www.uncitral.org/pdf/english/congress/Papers_for_Congress/

29-DOLES_SILVA-Cryptocurrencies_and_International_Regulation.pdf (accessed 13 August 2018).

8. EU (2018) Factsheet, 5th AML Directive, available at http://europa.eu/rapid/press-

release_STATEMENT-18-3429_en.html

9. Financial Action Task Force (FATF) (2018a). About. Available at: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/about/

(accessed 16 August 2018).

10. FATF (2018b) G20 Report. Available at: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/

FATF-Report-G20-FM-CBG-July-2018.pdf (accessed 16 August 2018).

11. FATF (2015) Guidance For a Risk-based Approach To Virtual Currencies. Available at: http://

www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Guidance-RBA-Virtual-Currencies.pdf (accessed

16 August 2018).

12. Foley S, Karlsen JR and Putniņš TJ (2018) Sex, Drugs, and Bitcoin: How Much Illegal Activity Is

Financed Through Cryptocurrencies? ID 3102645, SSRN Scholarly Paper, 15 January. Rochester,

NY: Social Science Research Network. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3102645

(accessed 1 September 2018).

13. Hałaburda H and Sarvary M (2016) Beyond bitcoin: the economics of digital currencies. Palgrave,

UK.

14. He D, Habermeier K, et al. (2016) Virtual Currencies and Beyond: Initial Considerations. Staff

Discussion Notes IMF 16(03): 1. DOI: 10.5089/9781498363273.006.

15. Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2018) Definition of Cryptocurrency. Available at: https://

www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cryptocurrency (accessed 1 September 2018).

16. Sotiropoulou A and Guégan D (2017) Bitcoin and the challenges for financial regulation. Capital

Markets Law Journal 12(4): 466–479. DOI: 10.1093/cmlj/kmx037.

United Nations Economic & Social Council #15

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

17. Trautman LJ and Harrell AC (2016) Bitcoin versus Regulated Payment Systems: What Gives.

Cardozo Law Review 38: 1041–1098.

18. United Nations (2017) November 2017 Briefing on the World Economic Situation & Prospects.

Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/world-economic-situation-

and-prospects-november-2017-briefing-no-108/ (accessed 17 August 2018).

19. UN DESA (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs) (2017) Regulating the no

man’s coin - the rapid rise of cryptocurrencies has regulators scratching their heads. Available at:

https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/policy/cryptocurrencies.html (accessed 17 August

2018).

United Nations Economic & Social Council #16

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

4. Topic two: The fight against Money Laundering and

the Funding of Terrorism

1. Introduction

"Money laundering" is not a legal term in international law but is used to loosely describe the "turning

of dirty money into clean money". The act by which illicit funds are made to appear legitimate (which

the term refers to) is defined in key international instruments, most notably the UN Convention

Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances and the UN Convention Against

Transnational Organized Crime. The latter defines money laundering as: “The conversion or transfer

of property, knowing that such property is the proceeds of crime, for the purpose of concealing or

disguising the illicit origin of the property or of helping any person who is involved in the commission

of the predicate offence to evade the legal consequences of his or her action; or the concealment or

disguise of the true nature, source, location, disposition, movement or ownership of or rights with

respect to property, knowing that such property is the proceeds of crime”1.

The act of conversion and concealment is crucial to the laundering process, but it is important to

note that “laundered funds” never become legitimate. They only ever have the appearance of

legitimacy, not the reality, even though the so-called money trail may be complicated and obscure

the original criminal source of the funds. This is important because in jurisdictions where there is a

criminal asset confiscation scheme (proceeds of crime legislation), legitimate looking laundered

funds may still be forfeited to the State as criminal proceeds.

National strategies to combat money laundering must take into account the global nature of the

problem and therefore include not only effective criminal laws prohibiting money laundering and

persuasive penalties for those convicted, but also efficient and effective confiscation or forfeiture

mechanisms as well as effective laws to permit international cooperation around information sharing,

extradition and mutual legal assistance.

2. Focusing on the matter

The fifth edition of the 2017 Global Terrorism Index has recorded a total of 25,673 deaths due to

terrorism around the world last year. As grim as that figure is, it represents a 13 percent decrease in

deaths between 2015 and 2016. Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria, Syria and Pakistan accounted for three

1 Article 6, UN Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime

United Nations Economic & Social Council #17

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

quarters of the death toll, even though five of those countries (Iraq is the exception) recorded a

reduction in deaths since 2015 2.

Nigeria is notable as having the biggest

reduction in deaths with 3,100 fewer

people killed in 2016 than 2015. That's

primarily due to a an 80 percent fall in

the number of people killed by terror

group Boko Haram. The following

infographic shows the 10 countries

worst affected by terrorism in 2016,

according to the Global Terrorism

Index3 .

Amid the fight-back against the so-

called Islamic State group, Iraq had the

most deaths of any country by far in 2016 with 9,765. Afghanistan came second with 4,574 while

Syria rounded off the top three with 2,102.

The economic cost of terrorism equated to a

crippling 24 percent of Iraq's GDP last year. This is

according to the new Global Terrorism Index from the

Institute of Economics & Peace. Relatively speaking,

no other country is impacted more, with the second

most affected nation Afghanistan with 13 percent of

GDP.

The largest costs are caused by the loss of life. On

average, 81 percent of the economic impact is

accounted for by death. Not considered in the

calculations are the costs associated with

intelligence agencies budgets’ for which are likely to

have increased significantly in recent years.

2 Statista on terrorism: https://www.statista.com/topics/2267/terrorism/ : The Countries Worst Affected By Terrorism

3 Vision of humanity, measuring and understanding global terrorism: Global terrorism index

United Nations Economic & Social Council #18

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

3. Where do terrorist organisations get their money from?

1. Charities:

Donations were once the largest source of terrorist funding, coming mostly from charities

and wealthy individuals. For years, individuals and charities based in Saudi Arabia were the

most important source of funds for al-Qaeda, according to a 2002 CFR Task Force Report4.

A 2004 update to that report shows Saudi officials have taken steps to disrupt terrorist

financing in their country, yet charities continue to play a role in the sponsorship of terrorist

groups. "In the Islamic world, there are tens of thousands of charities," says Robert O.

Collins, coauthor of the new book Alms for Jihad5 . While as few as a hundred may sponsor

terrorism, "these are some of the wealthiest charities," Collins says. Experts say some of

these organisations raise funds with the express intent of supporting terrorists; others seek

to promote Islam through legitimate programs, but can be coopted by Jihadists who then

use the funds to promote their own radical cause.

2. Illegal activities:

Loretta Napoleoni, an expert on terrorist financing, says the largest source of terrorists’

income is the illicit drug trade6 . Many terrorist groups have supported themselves through

other illegal commerce as well. In his book, Illicit, Moisés Naím explains that the terrorists

behind the 1993 World Trade Centre bombing raised money by selling counterfeit t-shirts on

New York City’s Broadway, and the perpetrators of the 2004 Madrid train bombings sold

counterfeited CDs and trafficked drugs to support their activities. Hezbollah, the Irish

Republican Army, and the Basque ETA are also believed to have generated revenue through

counterfeiting scams. In 2002, federal agents broke up a methamphetamine ring in a dozen

U.S. cities that, according to officials, funnelled proceeds to Hezbollah. The Revolutionary

Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) has long used the cocaine trade to finance its

operations. Afghanistan’s flourishing poppy crops, which the United Nations says are

responsible for as much as 86 percent of the world opium supply, are widely believed to be

a major source of terrorist funding. Al-Qaeda reportedly profited from the Afghan poppy

trade before fleeing the country when the Taliban-led government was ousted in 2001.

3. Front companies:

4 Council on foreign relations: Terrorist financing

5 Robert O. Collins on the book Alms for Jihad

6 Loretta anapoeleoni on “Tracking Down Terrorist Financing”, Apr 16, 2006

United Nations Economic & Social Council #19

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

Many terrorist organisations attempt to operate legitimate businesses, which generate their

own profits and can also be used as a front for money laundering. Ties to terrorism have

been found amid the trade of livestock, fish, and leather. Businesses involved in agriculture

and construction have also been found to support terrorism. In 2001, the New York Times

reported that Osama bin Laden owned and operated a string of retail honey shops

throughout the Middle East and Pakistan7 . In addition to generating revenue, the honey was

used to conceal shipments of money and weapons.

4. How do terrorists transfer funds?

Quite often, terrorists transfer money in plain sight: "If it isn’t done through the ordinary banking

system, it’s done through shell companies”, says Bill Tupman, a senior lecturer at the University of

Exeter who specialises in transnational crime. In their book, Chasing Dirty Money, Peter Reuter and

Edwin M. Truman say financial crime is so widespread that as much as 10 percent of the global GDP

is estimated to be laundered funds. Despite heightened efforts to track terrorist financiers, the

vastness of the modern financial system means government officials often find themselves looking

for the proverbial needle in the haystack.

Another, more traditional means of transfer is also widely used by terrorists. Hawalas are time-

honoured, trust-based remittance agencies popular across Asia and found throughout the world,

particularly in Muslim communities. Hawala is a method of transferring money without any money

actually moving. Interpol's definition of hawala is "money transfer without money movement”.

Another definition is simply “trust". Hawala is an alternative remittance channel that exists outside of

traditional banking systems. Transactions between hawala brokers are made without promissory

notes because the system is heavily based on trust and the balancing of hawala brokers' books8.

Hawala, also known as Hundi, means transfer or remittance. With no more than a handshake and a

password, individuals are able to transfer money across the world.

5. How much does a terrorist operation cost?

Though the 9/11 attacks are believed to have cost as much as a half million dollars 9, most terrorist

operations have much more modest budgets. The UN estimates the 2002 bombing of a Bali

7 The New York Times: “A NATION CHALLENGED: AL QAEDA; Honey Trade Said to Provide Funds and Cover to bin Laden”, Oct 11, 2011

8 Investopedia: “what is Hawala?”

9 Council on foreign relations: Terrorist financing

United Nations Economic & Social Council #20

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

nightclub cost about $50,000. By comparison, the 2004 Madrid train bombing is believed to have

cost between $10,000 and $15,000. The 2005 attacks on London’s mass transit system cost about

$2,000, says Napoleoni.

6. What are governments doing to stop terrorist financing?

The 9/11 attacks brought an international sense of urgency to disrupting terrorists’ financial

networks. Within a few weeks, the UN Security Council adopted a wide-ranging resolution10

demanding countries take action to suppress terrorist financing. The following month, the Financial

Action Task Force, an intergovernmental body, issued a list of recommendations that became the

basis for many governments’ efforts. These included passing legislation specifically criminalising

terrorist financing, requiring financial institutions to report suspicious transactions, creating a greater

degree of international cooperation in tracking down terrorist financiers, and ratifying the UN

convention on financing terrorism, a step that has been taken by 150 countries. Like several other

nations, the United States created a special agency (the Office of Terrorism and Financial

Intelligence) to coordinate these efforts. The Patriot Act, along with subsequent legislation, created

tough legal measures to combat terrorist financing. While these measures have been fairly effective

within the United States, Napoleoni says terrorists have simply “shifted all the money to Europe”11.

7. What are some of the difficulties with tracking down terrorist

financiers?

The greatest difficulty is that terrorist networks have stayed aware of governments’ efforts to stymie

their activities and adjust their operations accordingly. Napoleoni says "terrorist financing mutates

continuously," which generally keeps terrorists a step ahead of the authorities. Terrorists have

increasingly relied on illegal activities, like smuggling or counterfeiting, to generate revenue that is

difficult to track through the financial system. Terrorists have also begun to rely more on cash,

leaving less of a paper trail. According to Napoleoni12, much of the funding for Abu Musab al-

Zarqawi’s al-Qaeda organization in Iraq is brought into the country by couriers carrying cash. The

July 2005 attacks in London were also funded entirely by cash, which Napoleoni says is

untraceable. The London attacks highlight another development in terrorist finance: the use of

domestic sources in planning and funding attacks. The bombings were planned inside Britain by

British citizens who raised all the money locally for the attacks. Because the plotters only used cash

10 Security council resolution on financing terrorism, resolution No.1373, 2001

11 Loretta Napoeleoni on her article “Tracking Down Terrorist Financing”, April 16, 2006

12 EADEM

United Nations Economic & Social Council #21

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

and didn’t cross any national borders, it was difficult to track their financial activities. Enforcement of

new financial laws has also proven difficult. According to the British Bankers’ Association, UK banks

spend about $430 million each year to comply with anti-terror and anti-money laundering laws.

Experts say the U.S. Department of Treasury is overwhelmed by the number of suspicious activity

reports it receives, which have risen some 350 percent since 2001.

8. How can governments more effectively combat terrorist

financing?

Because terrorist networks transcend national boundaries, improving international cooperation is

essential. "One of the problems of coordination," Wolosky says, "is reaching common ground on

’what is a terrorist organisation’”. The UN General Assembly has tried for more than a decade to

agree on a definition for terrorism, which would help underpin a comprehensive treaty banning the

practice. Beyond that, Napoleoni calls for an international body dedicated to information-sharing and

an international court to oversee the terrorism blacklist of individuals and organisations.

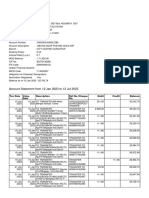

FIG 4: ESTIMATED TOTAL INCOME OF THE ISLAMIC STATE FROM 2014 TO 2016 IN

MILLION US DOLLARS (STATISTA INDEX ON INTERNATIONAL TERRORISM)

Minimum Maximum

Terrorists use techniques like those of money launderers to evade authorities' attention and to

protect the identity of their sponsors and of the ultimate beneficiaries of the funds. However, financial

United Nations Economic & Social Council #22

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

transactions associated with terrorist financing tend to be in smaller amounts than is the case with

money laundering, and when terrorists raise funds from legitimate sources, the detection and

tracking of these funds becomes more difficult.

To move their funds, terrorists use the formal banking system, informal value-transfer systems,

Hawalas and Hundis and, the oldest method of asset-transfer, the physical transportation of cash,

gold and other valuables through smuggling routes.

*http://calert.info/details.php?id=725

9. International legal instruments

1. INSTRUMENT REGARDING THE TAKING OF HOSTAGES:

A. 1979 International Convention against the Taking of Hostages13:

Provides that “any person who seizes or detains and threatens to kill, to injure, or to

continue to detain another person in order to compel a third party, namely, a State, an

international intergovernmental organisation, a natural or juridical person, or a group of

persons, to do or abstain from doing any act as an explicit or implicit condition for the

release of the hostage commits the offence of taking of hostage within the meaning of this

Convention”.

13 International Convention against the taking of hostages, 1979

United Nations Economic & Social Council #23

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

2. INSTRUMENT REGARDING TERRORIST BOMBINGS:

A. 1997 International Convention for the Suppression of Terrorist Bombings14:

Creates a regime of universal jurisdiction over the unlawful and intentional use of explosives

and other lethal devices in, into, or against various defined public places with intent to kill or

cause serious bodily injury, or with intent to cause extensive destruction of the public place.

3. INSTRUMENT REGARDING THE FINANCING OF TERRORISM:

A. 1999 International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism15:

Requires parties to take steps to prevent and counteract the financing of terrorists, whether

direct or indirect, through groups claiming to have charitable, social or cultural goals or

which also engage in illicit activities such as drug trafficking or gun running;

“Commits States to hold those who finance terrorism criminally, civilly or administratively

liable for such acts”;

“Provides for the identification, freezing and seizure of funds allocated for terrorist activities,

as well as for the sharing of the forfeited funds with other States on a case-by-case basis.

Bank secrecy is no longer adequate justification for refusing to cooperate”.

B. 2000 United Nations convention against organised crime16:

The Convention represents a major step forward in the fight against transnational organised

crime and signifies the recognition by Member States of the seriousness of the problems

posed by it, as well as the need to foster and enhance close international cooperation in

order to tackle those problems. States that ratify this instrument commit themselves to

taking a series of measures against transnational organised crime, including the creation of

domestic criminal offences (participation in an organised criminal group, money laundering,

corruption and obstruction of justice).

14 International Convention for the suppression of Terrorist Bombings, 1997

15 International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism, 1999

16 United convention against organised crime, 2000

United Nations Economic & Social Council #24

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

10. Questions a resolution must answer (QARMA)

Is a deeper and more specific regulation about money’s origins necessary?

How can the international community involve world financial institutions in this new regulation?

Is there a common legal framework that establishes which means are legal and which are not when

it comes to laundering?

How can national banks provide more security concerning illegal money laundering?

11. Bibliography

1. What is 'Hawala, Investopedia, n.d. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/h/

hawala.asp

2. The New York Times: “a Nation challenged: Al Qaeda; honey Trade said to provide funds and cover

to Bin Laden”, 11 October 2001. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2001/10/11/world/nation-

challenged-al-qaeda-honey-trade-said-provide-funds-cover-bin-laden.html

3. Maurice R. Greenb, Maurice R. Greenberg: “Terrorist Financing Report of an Independent Task

Force Sponsored by the Council on Foreign Relations”, n.d.

4. Statista: “Documents and graphics about terrorism financing”, n.d. Available at: https://

www.statista.com/statistics/202864/number-of-terrorist-attacks-worldwide/

5. Niall McCarthy, “The Countries Worst Affected By Terrorism”, Nov 15, 2017. Available at: https://

www.statista.com/chart/11849/the-countries-worst-affected-by-terrorism-in-2016/

6. International monetary fund official page: “Anti-Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of

Terrorism”, n.d. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/leg/amlcft/eng/

7. Niall McCarthy, “The Global Economic Impact Of Terrorism”, Nov 17, 2017. Available at: https://

www.statista.com/chart/11875/the-global-economic-impact-of-terrorism/

8. The International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, n.d. Available at: https://icsr.info/

United Nations Economic & Social Council #25

Anna Książczak & Simone Mostratisi

AUMUN 2018

9. International monetary fund official website, n.d. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/leg/

amlcft/eng/

10. UNITED NATIONS office on counter terrorism, n.d. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/

counterterrorism/legal-instruments.shtml

11. US department of state, n.d. Available at: https://www.state.gov/j/inl/c/crime/c44634.htm

12. UNODC official website, n.d. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/organized-crime/intro/

UNTOC.html

13. Compliance alert blog, n,d. Available at: http://calert.info/details.php?id=725

United Nations Economic & Social Council #26

Вам также может понравиться

- IMF Study Guide SMUN2030Документ15 страницIMF Study Guide SMUN2030kimaОценок пока нет

- Futuristic United Nations General Assembly Background GuideДокумент33 страницыFuturistic United Nations General Assembly Background GuideazharОценок пока нет

- Ecofin BG PDFДокумент12 страницEcofin BG PDFBarathy KolappanОценок пока нет

- Beyond the Developmental State: Industrial Policy into the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandBeyond the Developmental State: Industrial Policy into the Twenty-first CenturyОценок пока нет

- Ecosoc Guide 2Документ6 страницEcosoc Guide 2Pepe RamirezОценок пока нет

- Midterm Contemporary Global GovernanceДокумент14 страницMidterm Contemporary Global GovernanceBINIBINING KOLEHIYALAОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Global GovernanceДокумент7 страницContemporary Global GovernanceNiorun Aruna QuinnОценок пока нет

- BGG EcoosocДокумент16 страницBGG EcoosocPAOLA EDITH RODRIGUEZ TARINОценок пока нет

- UNHRCДокумент17 страницUNHRCAshhab KhanОценок пока нет

- Structure of GlobalizationДокумент23 страницыStructure of GlobalizationLea HaberОценок пока нет

- Sismun Ecofin Study GuideДокумент14 страницSismun Ecofin Study GuideShivank MenonОценок пока нет

- 2023 IMUNC ProspectusДокумент10 страниц2023 IMUNC Prospectusjanice sugiОценок пока нет

- Jmcmun'20 InviteДокумент12 страницJmcmun'20 InviteAnubha GuptaОценок пока нет

- Background Guide - UNHRC - UMUN'22Документ13 страницBackground Guide - UNHRC - UMUN'22Karan JainОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Global GovernanceДокумент12 страницContemporary Global Governancejonalyn alsadoОценок пока нет

- Hon M Kirby AC CMG "International Symposium On The Public Voice and The Development of International Cryptography Policy"Документ11 страницHon M Kirby AC CMG "International Symposium On The Public Voice and The Development of International Cryptography Policy"Journal of Law, Information & ScienceОценок пока нет

- Economic & Social Council - Background GuideДокумент17 страницEconomic & Social Council - Background GuideAkshat Jain EfiОценок пока нет

- A United Nations Renaissance: What the UN is, and what it could beОт EverandA United Nations Renaissance: What the UN is, and what it could beОценок пока нет

- The Contemporary World ReviewerДокумент14 страницThe Contemporary World ReviewerArabella Consulta BrugadaОценок пока нет

- Combating Cyber ThreatОт EverandCombating Cyber ThreatP K SinghОценок пока нет

- C2d Contemporary Global GovernanceДокумент7 страницC2d Contemporary Global GovernanceBeautiful LifeОценок пока нет

- UNHCR Background Guide Rotaract MUN Change The World New YorkДокумент10 страницUNHCR Background Guide Rotaract MUN Change The World New YorkAdrian Dan PopОценок пока нет

- Slspmun 24 BrochureДокумент12 страницSlspmun 24 Brochurerani.ishwar1986Оценок пока нет

- Licensed larceny: Infrastructure, financial extraction and the global SouthОт EverandLicensed larceny: Infrastructure, financial extraction and the global SouthРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (2)

- The Amounts and The Effects of Money LaunderingДокумент187 страницThe Amounts and The Effects of Money LaunderingPetros ArvanitisОценок пока нет

- Ecosoc Brochure enДокумент2 страницыEcosoc Brochure enAnkit AnandОценок пока нет

- A Voice For Global Citizens. A UN World Citizens InitiativeДокумент80 страницA Voice For Global Citizens. A UN World Citizens InitiativeRavana KaifОценок пока нет

- A4. Geo3-Global Interstate SystemДокумент16 страницA4. Geo3-Global Interstate SystemMENONG, SHARA AMORОценок пока нет

- Structures of Globalization: Module DescriptionДокумент8 страницStructures of Globalization: Module DescriptionyowОценок пока нет

- Diplomacy and International Relations - Sample Questions and AnswersДокумент4 страницыDiplomacy and International Relations - Sample Questions and AnswersLumina Hazellyn100% (1)

- Administrative HandbookДокумент11 страницAdministrative Handbookapi-246792700Оценок пока нет

- Lesson 4 Global Interstate System PDFДокумент15 страницLesson 4 Global Interstate System PDFJervyn Guianan33% (3)

- UNGA Background GuideДокумент20 страницUNGA Background GuideFascinating FactОценок пока нет

- Sponsor HandbookДокумент377 страницSponsor Handbookapi-238639222Оценок пока нет

- Principality of Monaco: Combined Delegation of TheДокумент2 страницыPrincipality of Monaco: Combined Delegation of TheHELEN SHARPEОценок пока нет

- CBITMUN'24 UNGA-SOCHUM Background GuideДокумент25 страницCBITMUN'24 UNGA-SOCHUM Background Guideaditihaasini13Оценок пока нет

- Human Rights in The Global Economy - Colloquium Report 2010Документ28 страницHuman Rights in The Global Economy - Colloquium Report 2010International Council on Human Rights PolicyОценок пока нет

- ECOSOCДокумент24 страницыECOSOCAyushmaan SharmaОценок пока нет

- Political Science Project 1Документ12 страницPolitical Science Project 1Aadhitya100% (2)

- Chimni 2004 PDFДокумент37 страницChimni 2004 PDF王储Оценок пока нет

- Edited Biscmun 2017 Conference HandbookДокумент26 страницEdited Biscmun 2017 Conference Handbookapi-302308551Оценок пока нет

- Mun Guide FinalДокумент35 страницMun Guide FinalAnusha Mahtani100% (2)

- Contemporary Module 2 PDFДокумент15 страницContemporary Module 2 PDFCharleen RomeroОценок пока нет

- Unga-Plenary Study GuideДокумент14 страницUnga-Plenary Study Guidejyotiarko1122Оценок пока нет

- ContemporaryДокумент10 страницContemporaryDan Jezreel EsguerraОценок пока нет

- Kenya Affidavit Website VersionДокумент25 страницKenya Affidavit Website Versionmosadsd.saОценок пока нет

- NeCon BrochureДокумент27 страницNeCon BrochureAditya MОценок пока нет

- UNIT I: Human Rights & UN Module 3: Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC)Документ12 страницUNIT I: Human Rights & UN Module 3: Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC)Zeeshan AhmadОценок пока нет

- G8 CountriesДокумент29 страницG8 CountriesDaranОценок пока нет

- The Globalizers: The IMF, the World Bank, and Their BorrowersОт EverandThe Globalizers: The IMF, the World Bank, and Their BorrowersРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (2)

- The Ideal Within: A Discourse and Hegemony Theoretical Analysis of the International Anticorruption DiscourseОт EverandThe Ideal Within: A Discourse and Hegemony Theoretical Analysis of the International Anticorruption DiscourseОценок пока нет

- Redesigning the World Trade Organization for the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandRedesigning the World Trade Organization for the Twenty-first CenturyОценок пока нет

- OIC and Its RelevanceДокумент6 страницOIC and Its RelevanceQasim Javaid BokhariОценок пока нет

- OIC EssayДокумент6 страницOIC EssayQasim Javaid BokhariОценок пока нет

- Cfmun Position Paper: NAME: Juanita Galvis Vélez. COMMISSION: Security Council (SC) COUNTRY: KenyaДокумент5 страницCfmun Position Paper: NAME: Juanita Galvis Vélez. COMMISSION: Security Council (SC) COUNTRY: KenyaFr4nc0288Оценок пока нет

- IDCMUN 1.0 Delegate InvitationДокумент10 страницIDCMUN 1.0 Delegate InvitationSameer VishwakarmaОценок пока нет

- A Critical History of Poverty Finance: Colonial Roots and Neoliberal FailuresОт EverandA Critical History of Poverty Finance: Colonial Roots and Neoliberal FailuresОценок пока нет

- Counter-Terrorism, Policy Laundering' and The FATF: Legalising Surveillance, Regulating Civil SocietyДокумент68 страницCounter-Terrorism, Policy Laundering' and The FATF: Legalising Surveillance, Regulating Civil SocietyIndian Social Action Forum - INSAFОценок пока нет

- Globalization and PoliticsДокумент10 страницGlobalization and PoliticsMuzaffar Abbas SipraОценок пока нет

- Balikbayan Box Companies Accredited by DTI in 2016 - NewsДокумент15 страницBalikbayan Box Companies Accredited by DTI in 2016 - NewsEdward OropezaОценок пока нет

- ITIL MALC Case Study 1 v1.1 PDFДокумент7 страницITIL MALC Case Study 1 v1.1 PDFGrzegorz Urbanowicz100% (2)

- Semester: B. Com - V Semester Name of The Subject: Financial Market & Institutions Unit-1Документ61 страницаSemester: B. Com - V Semester Name of The Subject: Financial Market & Institutions Unit-1Sparsh JainОценок пока нет

- Membership Application FormДокумент1 страницаMembership Application FormProutist Universal MaltaОценок пока нет

- 2nd Mate OOW For Ratings STC UKДокумент5 страниц2nd Mate OOW For Ratings STC UKFabian MascarenhasОценок пока нет

- Insurance Broking BusinessДокумент56 страницInsurance Broking Businesshardikpawar100% (4)

- PB 2019-035 Noodregeling Banco Del Orinoco ENG BDO 20190906Документ1 страницаPB 2019-035 Noodregeling Banco Del Orinoco ENG BDO 20190906Knipselkrant CuracaoОценок пока нет

- Mortgages 2019Документ60 страницMortgages 2019Ivana JayОценок пока нет

- AsdadasДокумент13 страницAsdadasSwindlerОценок пока нет

- CA Short Form Deed of TrustДокумент3 страницыCA Short Form Deed of TrustAxisvipОценок пока нет

- ShipRocket ProposalДокумент7 страницShipRocket ProposalShashi Bhushan SinghОценок пока нет

- Easypaisa Money Transfer To Any Mobile NumberДокумент2 страницыEasypaisa Money Transfer To Any Mobile NumberBryan WalkerОценок пока нет

- Nmims Final Report123 PDFДокумент46 страницNmims Final Report123 PDFHimanshu KhandelwalОценок пока нет

- Accounting NotesДокумент23 страницыAccounting NotesboiroyОценок пока нет

- SF 8.10A Audit Certificate For The Month of - (1st Month), 2020Документ1 страницаSF 8.10A Audit Certificate For The Month of - (1st Month), 2020praveenitplОценок пока нет

- Barings CaseДокумент3 страницыBarings CaseAnonymous LC5kFdtcОценок пока нет

- TRAIN Law BriefingДокумент30 страницTRAIN Law BriefingJoselito PabatangОценок пока нет

- MULTIPLE CHOICE. Choose The One Alternative That Best Completes The Statement or Answers The QuestionДокумент3 страницыMULTIPLE CHOICE. Choose The One Alternative That Best Completes The Statement or Answers The QuestionMohammad Abu LailОценок пока нет

- OidhvohsДокумент10 страницOidhvohsDeepak ShastriОценок пока нет

- A111actuarial Mathematics #1 - Single Premium Life InsuranceДокумент13 страницA111actuarial Mathematics #1 - Single Premium Life Insuranceolim275Оценок пока нет

- Comparative Financial Statement Analysis of The Big Three Banks Operating in Finland 2015-2016Документ49 страницComparative Financial Statement Analysis of The Big Three Banks Operating in Finland 2015-2016Eugene Rugo AОценок пока нет

- Account Statement From 12 Jan 2023 To 12 Jul 2023Документ10 страницAccount Statement From 12 Jan 2023 To 12 Jul 2023SouravDeyОценок пока нет

- Aehbl Shae1705167Документ2 страницыAehbl Shae1705167idris_ali_7Оценок пока нет

- PDFДокумент3 страницыPDFArchanaNitinОценок пока нет

- Bank Reconciliation StatementДокумент40 страницBank Reconciliation StatementPrashant100% (1)

- MACN-A018 Universal Affidavit of Termination of All CORPORATEДокумент4 страницыMACN-A018 Universal Affidavit of Termination of All CORPORATEJabir Habib Bey33% (3)

- Annual Rep Eng 09Документ214 страницAnnual Rep Eng 09amitgoyal1972Оценок пока нет

- FIN036 AssignmentДокумент25 страницFIN036 AssignmentSandeep BholahОценок пока нет

- Working of Post Offices and Measures To Improve ItДокумент17 страницWorking of Post Offices and Measures To Improve ItsuchethatiaОценок пока нет

- A Cheque Is A DocumentДокумент15 страницA Cheque Is A Documentmi06bba030Оценок пока нет