Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

JUDICIAL REVIEW OF ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEEDINGS

Загружено:

vijaya choudharyОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

JUDICIAL REVIEW OF ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEEDINGS

Загружено:

vijaya choudharyАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

JUDICIAL REVIEW OF ADMINISTRATIVE

PROCEEDINGS *

PROF. LAWRENCE F. EBB

My remarks on the problem of judicial review of administra-

tive proceedings are intended to be purely introductory, and to lead

up to the fuller comments that will be made on this topic by Professor

Byse.

First, I would like to make some preliminary comments on the

relationship between our present discussions on administrative law

and the discussions held at Stanford last summer by the group of 9

Indian and American lawyers that assembled there for 5 weeks of in-

tensive work. As I see it, the discussions of last summer accomplished

some of the spade work of digging out, outlining and analyzing in

a preliminary fashion some of the problems of public law—particu-

larly administrative law, and also constitutional law—that are current-

ly of vital concern to India, as well as to other democratic countries.

The results of those weeks of intensive group discussions and preli-

minary research are embodied in the book, "Public Law Problems in

India—A Survey Report."

Our objective is to carry on a working group to determine prio-

rities to be accorded to the different types of research projects that are

possible in the public law field ; determine just what the various re-

search projects embarked upon during the first year of the Indian Law

Institute's operations should cover—what precise topics should be studi-

ed, what types of legal and non-legal materials should be used, how the

research groups should be organized and what research techniques

should be utilized. Our first topic concerning judicial review of ad-

ministrative proceedings may give us a good opportunity to work out

these problems with respect to a particular project.

As I have mentioned, administrative law problems were covered

intensively during the survey by the working group at Stanford last

summer. During the survey, it was repeatedly recognized by the parti-

cipants that the problems of administrative law were related to those

of constitutional law. Whether or not a hearing is required in a parti-

cular case before a tribunal, whether or not a hearing has to contain

certain ingredients that comprise fair play, might, on the one hand, be

questions of statutory construction, but might also, on the other hand,

involve ultimate constitutional questions. In the United States, these

* A talk given on 14th December, 1957, at the Seminar in the Indian Law

Institute.

74 JUDICIAL REVIEW OF ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEEDINGS

constitutional questions would be considered largely under the head-

ing of the concept of due process of law, imbedded in the 5th and 14th

Amendments to the American Constitution. In India, I understand

that these questions would arise either in connection with the general

legal concept of "Natural Justice" or with specific reference to the

14th and 19th Articles of the Constitution. The role of the courts

in reviewing administrative proceedings to determine compliance with

statutory procedures of constitutional principles is a role that is partly

explicit, and partly implicit in the American Constitution. To the

extent that the court supervises administrative proceedings by its con-

struction of statutes, this is a role that the federal courts exercise under

the explicit terms of Article III, Section 2 of the American Constitu-

tion with respect to federal administrative tribunals.

To the extent that review of administrative action by the federal

courts is based on a federal constitutional question, the review of the

constitutional validity of the statute under which the administrative

agency operates, or the review of the constitutional validity of the ad-

ministrative action itself, is undertaken under a doctrine of the role of

the Supreme Court which is not spelled out in our Constitution. This

doctrine was laid down as implicit in our Constitution by Chief Justice

Marshall in the famous case of Marbury v. Madison.1 The Indian

Constitution is more explicit with respect to judicial review of the cons-

titutional validity of either the statute governing the administrative

agency's action or the validity of the administrative action itself. Arti-

cle 13 makes clear that the courts do have the power of judicial review

of the constitutionality of statutes and administrative rules and regu-

lations.

The historical background of judicial review is well presented in

pages 715-722 of Gellhorn and Byse *'Administrative Law, Cases

and Comments" (1954). Our courts in the United States tend to view

current problems of administrative law in the main in terms of judicial

construction of statutory requirements. Thus, the federal courts

would, at least overtly, handle as a matter of statutory inter-

pretation rather than as a matter of constitutional law the question of

whether an administrative body must give notice and an opportunity

to be heard to interested individuals. But, underlying the statutory

construction problem, the ''ultimate legal problem is whether the

procedure utilized satisfies the guarantee of due process of law" 2 .

One may hazard the guess that the same situation prevails in Indian

courts—that the constantly reiterated question as to whether certain

1. 1 Cranch 137 (1803)

2. Gellhorn & Byse—Supra p. 715.

LAWRENCE F. EBB 75

procedures must be followed by administrative tribunals in order to

conform to the requirements of "natural justice" really refers, ultima-

tely, to a constitutional question which is embodied in the written Cons-

titution itself, as well as existing implicitly in the general constitutional

doctrines of the country. In the United States, the constitutional pro-

visions that are especially relevant, though they are by no means the

only ones that are relevant, are the due process clause of the Fifth

Amendment as against the Federal Government and the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment as against the States—i.e., the

right of a person not to be deprived by Governmental action "of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law."

Most Indian lawyers seem well aware of the fact that the fight

waged by Dr. Munshi and others^ at the Constituent Assembly to

have the due process clause incorporated in the Indian Constitution

was defeated.3 Thus, Article 21 merely says that: "No person shall

be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to proce-

dure established by law" (emphasis added), whatever that latter term may

mean. But note that Article 21 is not the only provision in the Funda-

mental Rights portion of the Indian Constitution that may be relevant

to judicial review of administrative action. Article 14 contains a

guarantee of equal protection of the law and, what is more significant,

Article 19 contains guarantees of various personal rights—-civil rights

and property rights—subject only to "reasonable restrictions." To

an American, Article 19 seems in substance to convey the same impli-

cations as the due process clause in the American Constitution with

respect to judicial review of administrative action. Thus, the frequent

references to "natural justice" in Indian judicial opinions concerning

the propriety of procedures used by administrative tribunals and de-

partments of government would seem ultimately to refer to constitu-

tional guarantees to the individual under Article 19 in much the same

way as American judicial discussion of the meaning of statutes govern-

ing administrative action may refer ultimately, though tacitly, to the

due process guarantees under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.

In sum, the old natural law concepts of what is ethically right

became embodied in Lord Coke's doctrine of the "due process of the

common law." Lord Coke's doctrine in turn has become applicable

to test the soundness of administrative procedures in the United States,

ultimately, through the due process language of the Fifth and Four-

teenth Amendments (and through other constitutional provisions such

as the First Amendment guarantee of the right of free speech). The

same doctrine has become applicable in India, ultimately, through

3. Constituent Assembly Debates, III, 426 and VII, 1001.

76 JUDICIAL REVIEW OF ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEEDINGS

Article 19. And this is so, even though American courts today may tend

to refrain from explicit discussion of constitutional limitations in many

cases and dwell instead on questions of statutory construction. The

same proposition seems to hold true of India even though Indian courts

may similarly tend to shy away from reference to Article 19 in admi-

nistrative law cases and may dwell on the requirements of the more

generalized doctrine of "natural justice."

Just what the precise requirements of Due Process or Natural

Justice are in particular cases involving administrative action remain

for consideration. The foregoing preliminary remarks merely describe

the general constitutional framework within which these questions are

settled and suggest that there is a parallel that may be drawn between

the ultimate constitutional standards for judicial review of adminis-

trative action in India and the United States. In looking ahead to

the forthcoming discussion of the particular doctrines laid down by

the courts in their review of administrative action, it may be useful to

note that constitutional questions may be involved in such matters as

the right to hearing, the right to notice, the right to appear with

counsel, the right of an interested person to obtain a full disclosure

of testimony, the right to confront witnesses—all of these being ques-

tions relating to the administrative hearing ; and, apart from the hear-

ing questions, there may be constitutional questions concerning the

delegation of legislative power—the sufficiency of legislative standards

laid down for the administrator to follow. It may also be useful at

this point to invite your attention to materials contained in the book

on "Public Law Problems in India" that bear on these questions:

See, for example, the paper on Proposed Topics for Administrative

Law Research, with its discussion of the problems of delegation of

power on page 2, and its discussion of the right to a hearing and the in-

gredients of a fair hearing, on pages 4—5, and 14—15. See also the

paper on "Administrative Law—The Right to a Fair Hearing"

pages 38-52, noting among other things the reliance placed on Arti-

cle 19(1) (g) by the Indian Supreme Court in declaring void licensing

order under the Essential Supplies Act in the Dwarka Prasad case in

1954>

4. A.I.R. 1954 S.C. 224.

Вам также может понравиться

- Introduction to the Legal Process School and its Central TenetsДокумент14 страницIntroduction to the Legal Process School and its Central TenetsFalalaОценок пока нет

- File PDFДокумент4 страницыFile PDFFAYAJ DADEKHAN PATHANОценок пока нет

- Legal Realism's Impact on Indian Constitutional InterpretationДокумент25 страницLegal Realism's Impact on Indian Constitutional InterpretationRakesh SahuОценок пока нет

- 2000 Fall 3Документ4 страницы2000 Fall 3Catherine MerillenoОценок пока нет

- Legislation and The Interpretation of Statutes: Binky 4Документ5 страницLegislation and The Interpretation of Statutes: Binky 4blimjucoОценок пока нет

- Judicial Review in Common Law and its DevelopmentДокумент2 страницыJudicial Review in Common Law and its Developmentadonis teamОценок пока нет

- Weak Courts, Strong Rights: Judicial Review and Social Welfare Rights in Comparative Constitutional LawОт EverandWeak Courts, Strong Rights: Judicial Review and Social Welfare Rights in Comparative Constitutional LawРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (2)

- Rule of LawДокумент7 страницRule of LawAddyAdityaLadhaОценок пока нет

- J B Etcheverry Rule of Law and Judicial Discretion ARSPДокумент18 страницJ B Etcheverry Rule of Law and Judicial Discretion ARSPClari PollitzerОценок пока нет

- Research Material ForДокумент17 страницResearch Material ForYns2011Оценок пока нет

- NATURAL LAW & JUDICIAL ACTIVISMДокумент15 страницNATURAL LAW & JUDICIAL ACTIVISMAshish ChandaheОценок пока нет

- The Concept of Due Process As Embodied in US Constitutional Law and in India's Constitutional LawДокумент12 страницThe Concept of Due Process As Embodied in US Constitutional Law and in India's Constitutional LawDivya PandeyОценок пока нет

- LegalДокумент15 страницLegalv.pandian Pandian100% (1)

- Administrative Law PDFДокумент118 страницAdministrative Law PDFRobin SinghОценок пока нет

- Administrative Tribunals in IndiaДокумент21 страницаAdministrative Tribunals in IndiaVinod Thomas EfiОценок пока нет

- Comparative Law Study Legal Systems DifferencesДокумент6 страницComparative Law Study Legal Systems DifferencesAkshay BhasinОценок пока нет

- Intro To Law ManualДокумент58 страницIntro To Law ManualArchie ArticuloОценок пока нет

- Due Orocess of LawДокумент18 страницDue Orocess of LawvkОценок пока нет

- Equality Legislative Review Under ArticlДокумент35 страницEquality Legislative Review Under ArticlSaharsh ChitranshОценок пока нет

- Administrative Law NotesДокумент115 страницAdministrative Law NotesAmiya Bhushan SharmaОценок пока нет

- Strict Scrutiny' Test in Constitutional Adjudication: Indian ExperienceДокумент22 страницыStrict Scrutiny' Test in Constitutional Adjudication: Indian ExperienceChiranjeev RoutrayОценок пока нет

- Judicial Review and Schedule 9Документ37 страницJudicial Review and Schedule 9Akash Deep PandeyОценок пока нет

- Vol 14 No 12 09.tushnetДокумент16 страницVol 14 No 12 09.tushnetNatalia Torres ZunigaОценок пока нет

- Consti - IIДокумент3 страницыConsti - IIprakhar bhattОценок пока нет

- Revival of Doctrine of Manifest ArbitrarinessДокумент17 страницRevival of Doctrine of Manifest ArbitrarinessTC 15 SPEAKER 2Оценок пока нет

- Natural JusticeДокумент10 страницNatural Justicehumble bee100% (1)

- Judicial Review:: ST THДокумент4 страницыJudicial Review:: ST THshreekumar_scdlОценок пока нет

- BUSINESS LAW AndargachewДокумент39 страницBUSINESS LAW AndargachewdavidОценок пока нет

- Administrative Procedure ActДокумент13 страницAdministrative Procedure ActRam100% (2)

- SSRN Working 2LR ReДокумент154 страницыSSRN Working 2LR ReManikandan ManikandanОценок пока нет

- Principles in LegislationДокумент25 страницPrinciples in LegislationAASUGEОценок пока нет

- Judicial ActivismДокумент9 страницJudicial ActivismJakeОценок пока нет

- Doctrine of Judicial Review ExplainedДокумент8 страницDoctrine of Judicial Review Explainedabhijeet sharmaОценок пока нет

- Legal Positivism Rule of RecognitionДокумент3 страницыLegal Positivism Rule of RecognitiontotoОценок пока нет

- Judicial LawДокумент25 страницJudicial LawUjjwal JoshiОценок пока нет

- Administrative Law - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaДокумент8 страницAdministrative Law - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediahgkgkgkgkgОценок пока нет

- BP Polsc JR 2017DUCTIONДокумент12 страницBP Polsc JR 2017DUCTIONBhanuОценок пока нет

- Balakrishnan SpeechДокумент27 страницBalakrishnan SpeechAakash NarangОценок пока нет

- Rule of Law EssayДокумент10 страницRule of Law Essaymonki1331Оценок пока нет

- Liberty After Freedom: A History of Article 21, Due Process and the Constitution of IndiaОт EverandLiberty After Freedom: A History of Article 21, Due Process and the Constitution of IndiaОценок пока нет

- 07 - Chapter 1Документ16 страниц07 - Chapter 1Harsh SharmaОценок пока нет

- Unit-I Meaning and DefinitionДокумент23 страницыUnit-I Meaning and DefinitionSLV LEARNINGОценок пока нет

- Relation Between Adminstrative Law and Constitutional LawДокумент18 страницRelation Between Adminstrative Law and Constitutional LawAjay Lakra67% (3)

- Indian Federalism Project WorkДокумент17 страницIndian Federalism Project WorkAditya SinghОценок пока нет

- Torts AssignmentДокумент8 страницTorts AssignmentAnushka AgarwalОценок пока нет

- Fatima Jinnah Women University RawalpindiДокумент7 страницFatima Jinnah Women University RawalpindiFaiza ateqОценок пока нет

- 052 - Comparative Constitutional Law (1984) (368-374)Документ7 страниц052 - Comparative Constitutional Law (1984) (368-374)raorane.swati27Оценок пока нет

- Judicial Review in the US and IndiaДокумент22 страницыJudicial Review in the US and Indiashivam mishraОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Law: Rule of Law, ZimbabweДокумент9 страницConstitutional Law: Rule of Law, ZimbabwetatendaОценок пока нет

- Dynamic Statutory InterpretationДокумент78 страницDynamic Statutory InterpretationAdv.Seenath P SОценок пока нет

- Haase - What Does It Mean To Codify LawДокумент6 страницHaase - What Does It Mean To Codify LawChristopher ReynoldsОценок пока нет

- Access to Justice in India: Rule of Law and the Indian JudiciaryДокумент11 страницAccess to Justice in India: Rule of Law and the Indian JudiciaryGaurav HoodaОценок пока нет

- Interpretation of Constitutional Provisions: Case Law Development in IndiaДокумент20 страницInterpretation of Constitutional Provisions: Case Law Development in IndiaRachit MunjalОценок пока нет

- Project Report of Administrative Law: Topic: Meaning and Nature of Administrative Law W.R.T. Droit AdministratifДокумент7 страницProject Report of Administrative Law: Topic: Meaning and Nature of Administrative Law W.R.T. Droit AdministratifChandan KashyapОценок пока нет

- Q4 JurisprudenceДокумент3 страницыQ4 Jurisprudencefaisal awaisОценок пока нет

- DR Rajendra Pra-Wps OfficeДокумент20 страницDR Rajendra Pra-Wps OfficeSaaim SiddiquiОценок пока нет

- Weekly GS test covers history of Khilji Dynasty, soil geography and ParliamentДокумент10 страницWeekly GS test covers history of Khilji Dynasty, soil geography and Parliamentvijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- Satyamev Jayate Institute Articles: Class Notes SMJ InstituteДокумент3 страницыSatyamev Jayate Institute Articles: Class Notes SMJ Institutevijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- Allahabad HC Order HathrasДокумент11 страницAllahabad HC Order Hathrasvijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- High Court of Chhattisgarh Bilaspur: Request LetterДокумент3 страницыHigh Court of Chhattisgarh Bilaspur: Request Lettervijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorДокумент15 страниц6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- University Grants Commission Net BureauДокумент4 страницыUniversity Grants Commission Net Bureaumnb11augОценок пока нет

- CRPC Case LawsДокумент10 страницCRPC Case Lawsvijaya choudhary100% (1)

- Subscribe Our Youtube Channel: National ParksДокумент6 страницSubscribe Our Youtube Channel: National Parksvijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- Satyamev Jayate Institute Articles: Class Notes SMJ InstituteДокумент3 страницыSatyamev Jayate Institute Articles: Class Notes SMJ Institutevijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- CPC FlowChartsДокумент7 страницCPC FlowChartsvijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- Contribution of InsuranceДокумент11 страницContribution of InsuranceSyed M Basit RazaОценок пока нет

- OPC Word PDFДокумент77 страницOPC Word PDFrekha vasanthОценок пока нет

- Consortium of National Law Universities: Provisional 1st List - CLAT 2020 - PGДокумент2 страницыConsortium of National Law Universities: Provisional 1st List - CLAT 2020 - PGvijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- One Person Company: An Analytical StudyДокумент9 страницOne Person Company: An Analytical Studyvijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- Eligibility:: One-Year Post-Graduate Program (Ll. M.)Документ2 страницыEligibility:: One-Year Post-Graduate Program (Ll. M.)vijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- Hidayatullah National Law University: Admission FormДокумент2 страницыHidayatullah National Law University: Admission Formvijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- PG Calendar - 2020 2021Документ1 страницаPG Calendar - 2020 2021vijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- CLAT 2020 - PG - Invite List: Name Admit Card NoДокумент86 страницCLAT 2020 - PG - Invite List: Name Admit Card NoShalini SonkarОценок пока нет

- Corporate Law-I Project Sem VДокумент24 страницыCorporate Law-I Project Sem Vvijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- Revised - TIME TABLE-LLM-FIRST SEMESTER-2020Документ6 страницRevised - TIME TABLE-LLM-FIRST SEMESTER-2020vijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- 76 B 37 FDMC MQG Hzy JDoez Zoa HJRM4 Njpo 3 HK0 B EyqДокумент3 страницы76 B 37 FDMC MQG Hzy JDoez Zoa HJRM4 Njpo 3 HK0 B Eyqvijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- Revised - TIME TABLE-LLM-FIRST SEMESTER-2020Документ6 страницRevised - TIME TABLE-LLM-FIRST SEMESTER-2020vijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- Lock Down Extension Notification by Gov of INDIA (MHRD)Документ1 страницаLock Down Extension Notification by Gov of INDIA (MHRD)vijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Law Project List (Responses) - Form Responses 1Документ2 страницыConstitutional Law Project List (Responses) - Form Responses 1vijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- Section 164: Aps Judicial AcademyДокумент5 страницSection 164: Aps Judicial Academyvijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- CG Oct To Nov2018Документ6 страницCG Oct To Nov2018vijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- 249547rajasthan Syllabus PDFДокумент5 страниц249547rajasthan Syllabus PDFPrasenjit TripathiОценок пока нет

- Section 164: Aps Judicial AcademyДокумент5 страницSection 164: Aps Judicial Academyvijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc. and The Availability of Laches in Copyright Infringement Claims Brought Within The Statute of Limitations PDFДокумент57 страницPetrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc. and The Availability of Laches in Copyright Infringement Claims Brought Within The Statute of Limitations PDFvijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- 10 1 1 816 4171Документ13 страниц10 1 1 816 4171vijaya choudharyОценок пока нет

- Contract of Sale - SaysonДокумент2 страницыContract of Sale - SaysonDence Cris RondonОценок пока нет

- Motion For Withdraw: Attorney Edward T. Fenno (Righthaven v. Dana Eiser)Документ5 страницMotion For Withdraw: Attorney Edward T. Fenno (Righthaven v. Dana Eiser)rhvictimsОценок пока нет

- Form 27CДокумент2 страницыForm 27CrajdeeppawarОценок пока нет

- Democracy: Culture Mandala, Bulletin of The Centre For East-West Cultural and Economic Studies.: "Although Han FeiДокумент6 страницDemocracy: Culture Mandala, Bulletin of The Centre For East-West Cultural and Economic Studies.: "Although Han FeiMark LeiserОценок пока нет

- Victim Law Bulletin: Abatement Ab Initio and a Crime Victim’s Right to RestitutionДокумент4 страницыVictim Law Bulletin: Abatement Ab Initio and a Crime Victim’s Right to RestitutionMista Man100% (1)

- Juvenile Justice Welfare ActДокумент9 страницJuvenile Justice Welfare ActКатрина ШараповаОценок пока нет

- Motion To Quash - Ramon Picardal (Illegal Possession of Firearmsrobbery)Документ11 страницMotion To Quash - Ramon Picardal (Illegal Possession of Firearmsrobbery)JMОценок пока нет

- Fair DealingДокумент46 страницFair DealingIshtmeet SinghОценок пока нет

- Chapter 2 Taxes Tax Laws and Tax AdministrationДокумент29 страницChapter 2 Taxes Tax Laws and Tax Administrationdexter padayaoОценок пока нет

- Philippine Citizenship Case Analyzes Constitutional RequirementsДокумент3 страницыPhilippine Citizenship Case Analyzes Constitutional RequirementsBeverly De la CruzОценок пока нет

- Motion For Release of Brendan Dassey Pending Appeal of Wrongful Conviction RulingДокумент48 страницMotion For Release of Brendan Dassey Pending Appeal of Wrongful Conviction RulingMichael Lowe, Attorney at Law100% (1)

- Alejandro C. Almendras, JR., Petitioner, vs. Alexis C. Almendras, RespondentДокумент4 страницыAlejandro C. Almendras, JR., Petitioner, vs. Alexis C. Almendras, RespondentMarianne Shen PetillaОценок пока нет

- 119 - Motion For Stay Pending AppealДокумент20 страниц119 - Motion For Stay Pending AppealAnonymous qyOjaKukОценок пока нет

- Real Estate Principles Real Estate: An Introduction To The ProfessionДокумент28 страницReal Estate Principles Real Estate: An Introduction To The Professiondenden007Оценок пока нет

- R V WAKEFIELD (2019) NZHC 1629 (12 July 2019)Документ14 страницR V WAKEFIELD (2019) NZHC 1629 (12 July 2019)Stuff NewsroomОценок пока нет

- Introduction of ContractДокумент2 страницыIntroduction of ContractNicole AgostoОценок пока нет

- Craig B Hulet - Obama White PaperДокумент15 страницCraig B Hulet - Obama White PaperMike Esposito100% (1)

- Rental Agreement Shop@TempleДокумент7 страницRental Agreement Shop@TempleVirat VermaОценок пока нет

- Pil Jamon TipsДокумент8 страницPil Jamon TipsReyan RohОценок пока нет

- Ajla Vricic, A071 727 572 (BIA June 22, 2016)Документ7 страницAjla Vricic, A071 727 572 (BIA June 22, 2016)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLC50% (2)

- Valenzuela vs. CAДокумент8 страницValenzuela vs. CARomy Ian LimОценок пока нет

- Evidence NotesДокумент8 страницEvidence Noteskhariharasudhan8Оценок пока нет

- Articles of IncorporationДокумент4 страницыArticles of IncorporationDenis StevensОценок пока нет

- Supreme Court Rules on Tax Exemption CaseДокумент88 страницSupreme Court Rules on Tax Exemption CaseCeline Maria B. JanoloОценок пока нет

- Canon 3 CasesДокумент18 страницCanon 3 CasesgesalmariearnozaОценок пока нет

- Law of Equity & Trusts - 2019Документ4 страницыLaw of Equity & Trusts - 2019Ruvindi FernandoОценок пока нет

- CRIM 1 CASE DIGEST - CORPIN - CRL1 - JDNT-1B1 - Felonies - Part1Документ11 страницCRIM 1 CASE DIGEST - CORPIN - CRL1 - JDNT-1B1 - Felonies - Part1JemОценок пока нет

- Prisma Construction & Development Corp vs. Menchavez GR No. 160545 March 9, 2010Документ6 страницPrisma Construction & Development Corp vs. Menchavez GR No. 160545 March 9, 2010morningmindsetОценок пока нет

- Florida's Construction Lien Law: Protect Yourself and Your InvestmentДокумент2 страницыFlorida's Construction Lien Law: Protect Yourself and Your InvestmentpeterОценок пока нет

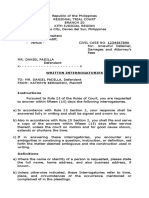

- Republic of the Philippines Regional Trial Court Written InterrogatoriesДокумент3 страницыRepublic of the Philippines Regional Trial Court Written InterrogatoriesKobe Bullmastiff100% (10)