Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Tambiah - The Magical Power of Words

Загружено:

Eu mesmoИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Tambiah - The Magical Power of Words

Загружено:

Eu mesmoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Magical Power of Words

Author(s): S. J. Tambiah

Source: Man, New Series, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Jun., 1968), pp. 175-208

Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2798500 .

Accessed: 29/07/2013 13:40

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to Man.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE MAGICAL POWER OF WORDS*

S. J.TAMBIAH

ofCambridge

University

Wordsin ritual

Contemporary anthropology hasin recentyearsbecomeawareoftherelevanceof

linguistics foritstheoretical advance,anditis remarkable thatMalinowski,perhaps

morefar-sighted thanmanyof hissuccessors, not onlysaw thisrelevancebut also

putforwardan ethnographical theoryof languagewhichsprangdirectly fromhis

fieldwork, particularly fromhisimmersion in Trobriandmagic.'

Malinowskiarguedthatthepotencyof Trobriandmagicwas feltby theTro-

brianders to lie inwords(spells).In manyofhisworks,particularly in Volume2 of

Coralgardensand theirmagic,he providedan unusualamount of supporting

linguisticdata. This evidencehas had some influence on linguists,notablyJ. R.

Firth,but it has never been criticallyexaminedby anthropologists. Can an

anthropologist getmoreout of theevidencethanMalinowskihimself managedto

do,eitherby resortto comparative materialfromothercultures or by closeratten-

tionto Malinowski'sown material?

AlthoughMalinowski'simmediate successors who workedin thesameornearby

regionsconfirmed thatthe verbal componentin ritualwas important(Fortune

I963; R. FirthI967), theorthodoxanthropological approachdevaluedtheroleof

wordsin ritualwhichwas seenas stereotyped behaviourconsisting ofa sequenceof

non-verbalacts and manipulation of objects. However, recent literaturehas again

shownappreciation of the roleof words 2 and no-one today I thinkwill dispute this

statement by Leach (I966: 407): 'Ritual as one observesit in primitive communi-

tiesis a complexofwordsandactions... itis notthecasethatwordsareone thing

and theriteanother.The uttering of thewordsitselfis a ritual.'

One virtueat leastofdefining ritualas consisting ofthewordandthedeedis that

thisformulasolvesthedilemmaposed by Goethe'sFaust-whetherin thebegin-

ningtherewas thewordor thedeed.Freudconcludedhis Totemandtaboowiththe

rhetoricalstatement thatin the beginningwas the deed. Accordingto Gellner

(I959: 22), linguistic philosophyhas unsuccessfully triedto solve the puzzle by

sayingthat'the word is a deed'. What I findinteresting about Faustis thathe

progressed fromtheword,to thought,thento thenotionof power,and ended

withthedeed.Thesefourtermsarein facttheingredients ofmostritualsystems in

whichthereis a reciprocal relationbetweenthewordand thedeed,withtheother

two termsintervening. The formularaisesone questionthatis quantitative in

nature:theratioofwordsto actionsmayvarybetweenritualsin thesamesociety

* The MalinowskiMemorialLecture,deliveredat theLondonSchoolof Economicsand

PoliticalScienceon 2o FebruaryI968. Extra materialhas been added to the textof the

lecture:futureMalinowskilectureswill,however,be publishedas delivered.

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I76 S. J. TAMBIAH

(or evenbetweensocieties).At one extremeis thecase of ritualsperformed with

words alone and at the otherthe case whereactionsdominatethoughperhaps

wordsare not excluded.Most ritualsfallin betweenbut yet may show distinct

differences in theproportion ofwordsto acts.Thusa healingritualor an initiation

ritemayemphasisewordswhilea collectiveritein whichthereis massparticipa-

tionmay relylesson auditorycommunication and moreon the displayof con-

spicuousvisiblematerialsymbols.

In mostcasesit would appearthatritualwordsareat leastas important as other

kindsofritualact; butbesidesthat,and thisis an intriguing point,veryoften(but

not always) if the ethnographer questionshis informants 'Why is this ritual

effective?' thereplytakestheformofa formally expressedbeliefthatthepoweris

in the'words' even thoughthewordsonlybecomeeffective if utteredin a very

specialcontextof otheraction.

In attempting to solve thispuzzle thefirstpointI want to make is thatritual

wordscannotbe treatedas an undifferentiated category.Ritualsexploita number

of verbalformswhich we looselyreferto as prayers,songs,spells,addresses,

blessings, etc.It is necessary to studywhethera ritualis composedof suchrecog-

nisedcategoriesand to analysetheirdistinctive featuresin termsof theirinternal

formand theirsequence.The factthatsucha battery ofverbaldevicesmayappear

in a singleriteshouldnotonlygiveus insights intotheartofritualbutalso dispel

any lingering tracesof a Frazerianhangover.Some of us have operatedwiththe

conceptof 'magic' as somethingdifferent from'religion'; we have thoughtof

spell' as actingmechanically and as beingintrinsically associatedwithmagic;we

haveopposed'spell' to 'prayer'whichwas thoughtto connotea different kindof

communication with the divine.Frazercarriedthisthinkingto an extremeby

asserting thatmagic was thoroughly opposed to religionand in the interestof

preserving thisdistinction dismissed halftheglobe as victimsof the'confusionof

magicwithreligion'.

It is possibleto questionthe generalvalidityof thisdichotomyby demon-

strating thatin a singleclassofritualspractised in Ceylonthereareuseda varietyof

verbalformsin a particular sequenceand thattheverylogic of theritualdepends

on thisorderand distinction. A Sinhalesehealingritualor exorcismceremony

exploitsthreemainkindsofverbalform3whichaccompanyotherritualacts(such

as dancing,miming,food offerings and manipulation of objects).They are called

mantra, kannalavvaand kaviya,and theyare arrangedin a progressionof four

sequencesbeginningand endingwiththemantra.4 The mantra corresponds to our

stereotype notionof 'spell'. It is in prose,ithasno poeticstructure, ithasa charac-

teristic openingand ending(e.g. 'omnamo'and 'hring').The mantra is muttered

by theexorcistand it is notmeantto be heardforit constitutes secretknowledge.

The ceremonybeginswiththe recitation of mantrawhichsummonthe demons

responsible forthe disease.This summoningis phrasedin Sinhaleseas 'hitting

withsound' (andagahanava),butthelanguageofcommandis also accompaniedby

the languageof entreatyand persuasion.These spellsalso containabbreviated

allusionsto mythsand thuspreparethegroundforthenextsequence.

This sequenceis thekannalavva whichis chantedaloud in rhythmic prosecom-

posed of ordinaryintelligible languageand is meantto be heardand understood

by theparticipants. The ritualas a publicceremonymaybe saidto beginwiththe

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE MAGICAL POWER OF WORDS 177

kannalavva. It stateswhy the ceremonyis beingheld,describesthenatureof the

and makesa plea to thegods to come and blesstheceremony

patient'saffliction,

and to the demonsto act benevolentlyand removethe disease.Typicallythe

pleasareaccompaniedbyfoodofferings.

The nextin sequencearethekaviya(verses)whichtakeup themajorpartofthe

ceremony.Kaviya are composed in quatrainswith end (and sometimesalso

beginning)rhymes.Sinhalesekaviyaare highlylyricaland framedin literary

Sinhalese(of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries),perfectlyintelligiblebut yet

distinctfromcontemporary everydaylanguage.They are normallyrecordedin

texts.Fromthepointof view of thedramaticpresentation of theritualit is im-

portantthattheyare sungloudlyto theaccompaniment of musicand mime.The

semanticcontentof theversesis a long and highlyredundant recitalof theorigin

mythsof gods and demonsand theirencounters, in which the demonsfinally

subjectthemselves to the practiceof conditionalevil, sanctionedby the deities

(varam),providedthathumansreciprocate by appropriate giftgiving.In therite

in

the mythsare sung orderthatevil and diseasecan be defined,objectifiedor

personified andpresented realisticallyon thestageso thattheappropriate actionof

changingtheundesirable to thedesirable, in otherwords,theactoftransfer which

changestheconditionof thepatient,withhisunequivocalparticipation, can take

place. The redundancy, lengthyrecitaland stagingare contrivedto achievethat

crucialunderstanding by thepatientof hisillnesswhichis a necessary preludeto

and a conditionof thecure.

The ceremonylogicallyenoughconcludeswitha mantra whichenactsthe ex-

pulsionofthedemonitself.Typicallythisspellconcludesthus:'Justas god so and

so, by a certainactionsubduedsuchand sucha demon,by thatpower may the

patientovercomethediseaseand thedemonbe subdued'.The lexicalandsemantic

contentsof thespellspresenta specialproblemwhen comparedto theothertwo

forms(invocationand praisesongs)whicharereadilyintelligible and heardby the

audience.Indologistswill be familiarwiththe literature on the long historyof

charmsandspells-mantra, dharanT,andparitta-inHinduismandBuddhism.I shall

digressfrommymainthemeifI enterthatterritory andshalltherefore limitmyself

to theSinhalesesituation.

A prevailingmisconception is thatSinhalesemantra are unintelligible or even

nonsensical.5 Credibility is lentto thisnotionby thefactthatmantra arereferred to

as the'languageof thedemons'(yaksabasava)as opposedto humanlanguage.A

linguisticanalysisofsomerecordedandpublishedSinhalesemantra madebyWimal

Dissanayakeof King's College, Cambridge,shows thattheyembodya subtle

designwhichusesthenotionof a hierarchy of languages.When Hindu gods are

invokedand theiroriginmythsreferred to,thespellscontainSanskrit expressions,

no doubtdistorted fromthepointof view of thepurist.When theBuddha and

Buddhistmythological eventsarealludedto,Pali wordsareemployed,once again

portraying syntactical When howeverthe spell actuallynarratesan

infelicities.

originmyth,thelanguageusedis thatof theclassicalSinhaleseliterary formspre-

valentin thesixteenth andseventeenth centuries. Finally,whendemonsaredirectly

addressedand commanded,thewordsare a polyglotmixtureand therefore un-

intelligible,

being compoundedof Sinhalese,Tamil, Pali, Sanskrit,Malayalam,

Telugu, Bengali and even Persian.This exotic and powerfulmixtureis the

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

178 S. J. TAMBIAH

'demonlanguage'.Somepointscanbe briefly madeconcerning thedesignof

thesespells:thelanguagestratification is indicative of thehierarchical positions

ofgodsanddemons:the'demonlanguage'is consciously constructed to connote

power,andthoughlargelyunintelligible is nevertheless basedon thetheory of

languagethatthedemonscan understand. Thus,farfrombeingnonsensical and

indiscriminatelyconcocted, thespellsshowa sophisticated logic.The logicof

constructionmustofcourse beseparated fromtheproblem ofwhether theexorcist

actually

understands all thewordscontained in thespell.Fromhis,as wellas the

audience's,pointof view,thespellshavepowerby virtueof secrecy and their

capacityto communicate withdemons andthereby influence theiractions. How-

ever,mantra do notfalloutside therequirements oflanguage as a system ofcom-

munication, andtheirliteralintelligibility to humans is notthecritical factor in

understanding theirlogic.

WhatI haveindicated inthisexample is thata singleSinhalese ritual progresses

fromspellswhichsummon thedemons toinvocation andsupplication ofthegods

and demons, thento sungand dramatised myths in verseform,and concludes

witha spellwhichusesthelanguage ofcommand andexorcism. Eachtypehasa

characteristic

formand content (thoughthisshowsredundancy), and thisstruc-

turedsequence is fundamental to thelogicwhichhasdictated theconstruction of

theritual.

Theverbalforms andtheirsequence haveatleasttwodimensions. On

theonehandtheydirectly correspond to thepantheon, thetheology itembodies,

including man'sinteraction withthegodsand spirits; and on theother,they

suggestanother logicwhichrelates tothecraft ofcommunication whereby patient

andparticipants successfully experience thepassagefromillnessto thepromised

cure.Furthermore, in thisexample, it is difficult to see wheremagicendsand

religionbegins.

I am of coursenotsuggesting thatthisSinhalese exampleprovidesa cross-

culturalrepresentative scheme, butI am certain thattheexploitation ofdifferent

verbalforms arranged inordered sequence istrueofmanycomplex rituals.Letme

verybriefly referto someexamples. The Stratherns report (personal communi-

cation)thattheMountHagenersdistinguish betweenprayer(atenga) and spell

(m0n);bothmayon occasions be combined in different patterns as forexample

whena spellmaybe saidto removea sickness, andthena prayer is madeto the

ancestral

ghosts accompanied bya sacrifice. Whilea prayer isanaudibleinvocation

and a supplication, thespellsaremuttered, use thelanguageof commandand

employ a seriesofmetaphorical images(seeStrathern & Strathern I968 fordetails).

Dr Audrey Richards (personal communication) statesthatBembarituals combine

prayersandspellswhicharedistinguished as arepraisesongsandother formal uses

of language.AgainVictorTurnerreports (I964) thatin theNdembuihamba

performance thereis massparticipation in hunters' cultsongswhicharesungto

'pleaseihamba', followed by a spateof confessions andtheairingof grievances,

thenbythereverent orhortatory prayers madebythedoctorandtheelders. He

comments thatall theseelements constitute a dialectical anddialogical pattern of

buthedoesnotfocushisattention

activity, onthisparticular problem ofalternating

verbalforms and theirstructured progression. It thusseemsto me thatthereis

scopeforusingthisframe ofanalysis toprovide additional illumination inthestudy

ofritual.

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE MAGICAL POWER OF WORDS 179

Sacredandprofane language

I wantnow to pursuefurther thequestionof theintelligibility of sacredwords

to bothofficiant and congregation. Ifsacredwordsarethoughtto possessa special

kindof powernotnormallyassociatedwithordinary language,to whatextentis

thisdue to thefactthatthesacredlanguageas suchmaybe exclusiveand different

fromthesecularor profanelanguage?

The role of languagein ritualimmediatelyconfronts problemsif placed in

relationto a primary function oflanguagewhichisthatitisa vehicleofcommunica-

tionbetweenpersons.By definition, thepersonsin communication mustunder-

standone another.In ritual,languageappearsto be usedin waysthatviolatethe

communication function. For instance,it is possibleto distinguish threedifferent

usesoflanguagein theritualsof a villagein northeast Thailand.

I. Firstly,thereare ritualsconductedby Buddhistmonksin whichthesacred

wordsarechantedaloud,i.e. theyaremeantto be heard,butparadoxically theyare

notunderstood by themajority ofthecongregation (andsomeofthemonksthem-

selves)becausethesacredlanguageis thedeadPali language.In thiscasethewords

are broadcastbutnot understood.

2. There is a secondset of ritualswhereagain the major feature is the loud

recitationof texts,but here the words are understoodbecause the local Lao

languageis used. The ritualsin questionare calledsikhwanor callingthe spirit

essence.They are used by villageelderswhen installing membersof thejunior

generation in villagestatuses,or as inauguralor threshold ritesbeforeindividuals

startnew enterprises. In thisinstance,then,wordsare broadcastand understood.

3. In a thirdsetof ritesrelatingto theexorcismof demonswhichpossessand

causementaldisorders, theinterrogation of thepatientis in thelocal languagebut

spellsaresecretly muttered bytheexorcistoversubstances likewaterwhichareused

to cleanseand purifythepatient.Here thevirtueof thespellsresidesin thefact

thatit is secretknowledgesimilarto theSinhalesemantra. The languageis private

andis notmeantto be heard.The spellswhicharecalledgatha (verses)aresaidto be

portionsof Buddhistsutra(sacredtexts)whicharein thiscontextusedin a special

manner,and thereis someevidenceforsayingthattheexorcistis an inversionof

theBuddhistmonk.

It is not necessary forme to give detaileddescriptions of thesecondand third

typesof ritualbecausetheyrepresent formswellknownto you. The spiritessence

ritesharesthecharacter ofthatclassofhealingritualswhichareconstructed on the

therapeutic theorythatmessagesare to be transmitted to and understood by the

celebrant orpatient.The wordsrecitedinvokeandinvitethedivineangels(thewada),

painttheritualsituationas a grandmythological eventin whichtheparticipants

becomegodsthemselves, definestatusrequirements, binda personto hisnew role

commitments, evokepastexperience (especiallyofearlychildhoodanddependence

on parents), andanticipate futureevents.By contrast, theexorcismritualusesshock

therapyin whichthepatientis made to confront, formulate and give objective

formto hisillnessin termsofa demonicagentwhichis culturally defined. Herethe

exorcistas protagonist mustappearmoreterribleand powerfulthanthe demon

insidethepatient,and thesecretly muttered spellsnotonlyconstitute thelanguage

thedemonscan understand, butmoreimportantly, contribute to theimageof the

exorcist's own power.

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I80 S. J. TAMBIAH

It is thefirstset,theBuddhistrituals, thatI wantto takeup becauseit represents

a generalbutbaffling The majorityof villagemonksin northeast

situation. Thai-

land(as in manyotherpartsofthecountry)areyoungmen who onlytemporarily

occupythestatusofmonk,and theirmostimportant roleis to conductcalendrical

templerituals for thecommunity as a whole, and mortuary ritesand certainother

threshold and protection-giving ceremonies for individual familiesand groupsof

kin.Therearesomeconspicuousparadoxesin thecommunication systemofBud-

dhistritual.The view is emphaticthatthePali chantsshouldbe recitedaloud and

thatthroughlisteningto themthe congregation gainsmerit,blessingsand pro-

tection.Yet thesacredPali wordsas suchare not understood.6 The chantsare of

coursenot nonsensical-theyexpoundmattersof Buddhistdoctrine,the noble

truths of detachment and conquestoflife,victoriousepisodesin theBuddha'slife,

whichhaveno directrelationto theeverydayconcernsof villagelife.Yet at the

conclusionof the chants,especiallythosedesignatedas paritta(chantsof blessing

and protection), theblessingstransferred by themonkto thelaymanarelonglife,

good healthand faircomplexion.The intriguing paradoxis thattheconquestsof

theBuddha whichrelateto thewithdrawalfromlifeare in theprocessof trans-

ferencetransmuted to an affirmation of life.Betweentherecitation of thesacred

words (suitra) and the final'pay off' to the laymanintervenes a mechanismof

transfer whichis not farremovedfromthatimpliedin theSinhalesemantra. For

instance,the chayamangalagdtha, the victoryblessingso oftenheardin Buddhist

rites,statesin eachof thestanzasa victorywon by theBuddhaand concludes'By

thispower,mayyou be endowedwithconquestsand blessings'.The mechanism

of transfer dependsnot onlyon thesemanticstructure of thewordsand theritual

actsthataccompanythem(e.g. transmission of gracethrougha sacredcordor by

sprinkling lustralwater)butalso on a particular socialrelationbetweenmonkand

layman,whichconnotesan inter-generational reciprocity. Villagesonstemporarily

renouncetheirvirilityand sexualityand transfer to elderlyhouseholders long life

and ethicalmerit;thelatterin turnsponsortheirordination, maintainthemin the

templeand afterwards, whentheygiveup theirrobes,installthemas theirsucces-

sors(TambiahI968).

The factthattheBuddhistchantsarecouchedin Pali is representative ofa more

generalfeatureof mostoftheso-calledworldreligions, whichalso showthesame

remarkabledisjunctionbetweenreligiousand profanelanguage: Latin in the

occidentalCatholicChurch,Hebrew forJews,Vedic Sanskritfor Hindus and

ArabicforMuslims,are sacredlanguagesthatare different fromthelanguageof

ordinaryuse. But thenatureof theauthority attachedto thesacredlanguageand

its rangeof exclusiveness shows complexvariations.The Muslimstake up the

extremepositionthattheKoranis efficacious onlyin itsoriginalArabicand thatit

will ceaseto be theBook by beingtranslated. The Jewishattitudeto theBiblical

textsis thesame-the wordofGod is in Hebrew.On theotherhandtheCatholics

have nevermaintained thatanypartof theBible was originally writtenin Latin,

but it is thecasethattheofficial version,theVulgate,was authorised by thePope

as Vicarof God in I546 at theCouncilof Trent.This textwentthroughcertain

revisionsin thesecond'halfof thesixteenth centuryto reacha definitive version.

But moreinterestingly, Latinhad by 250 A.D. supplantedGreekand becomethe

language of church governmentand worshipin Rome and for the entire

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE MAGICAL POWER OF WORDS

westernworld,andwas explicitly consideredtheholylanguageof theoccidental

church.

In Islam,Hinduism,BuddhismandJudaismtheview hasbeenstrictly heldthat

in religiousceremoniesthesacredwordsrecitedshouldbe in thelanguageof the

authorised sacredtexts.The problemwhethertheircongregations understood the

wordsor not was not a major consideration affecting eitherthe efficacy of the

ritualor the changein the moral conditionof the worshippers. The Catholic

Churchmaintainedthesameview in respectof Latinliturgyuntillastyear.It is

interesting thatmanyreformist movements whichattackedtheextreme formalism

andritualism oftheestablished to

churchattempted destroy the exclusivenessofthe

sacredlanguageinan attempt and

to increaseaccessibility understanding amongthe

faithful; Lutherans, Calvinists,Waldensians are cases in point.But note thatthey

also attackedthe Latin Bible on the groundsthattherewere older and more

genuineGreekversions.Thereis an important lessonto be learnedhere.Evan-

gelical Protestant Englishmenoftenget passionatelycommittedto the precise

wordingof theBiblicaltext,as it appearsin theEnglishof theauthorised version

of i6ii, even thoughit was authorised, illogicallyperhaps,by the King. The

Buddhauseda local dialectin contrast to theSanskritof theBrahmansto preach

hismessage,butPali itself was laterto becometheenshrined languageofTheravada

Buddhism.And breakawaychurches in turncome to have theirtrueversionsand

firsteditionsof doctrinearoundwhichproblemsof orthodoxycentreand which

generatethefamiliaractivitiesof textualcriticism and commentary thatprovide

thebreadand butterfortheologians andscholars. Thusin all thesecasesitcould be

said thattextstendto acquireauthority becausetheyare ancient,but thatit is

authority thatmatters morethanantiquity.

The questionthenis: how importantis it in unravelling the problemof the

power of sacredwordsthatthe sacredlanguagebe different fromthe ordinary

language?Is therea vitaldifference in thefactthattheKoranis in Arabicand the

Trobriandsacredwordsare in Trobriand?I thinkthe distinction is not absolute

but only relative.It is truethatin many of thesehigherreligionsthe sacred

languageis thoughtto be thatlanguagein whichthe saviour,or prophetor

saintfirstrevealedthemessage(or in the case of Catholicismto be thelanguage

authorised by thePapacy).But thisargument in termsofrevelationor authority is

justas applicableto theTrobrianders who believedthattheirspellscamewiththeir

firstancestors, providesno distinguishing

and therefore criterionbetweenhigher

and primitive religion.Tylor'sdistinction betweenrevealedand naturalreligion

is false.

A moreconvincing reasonmaybe thatthesacredwordsofIslam,Buddhism,and

theJewishand Christianfaithsat somepointcame to be writtendown,and that

writingis a revolutionary technologythatfixesand freezesreligiousdogma in a

mannerthatis different fromthe dogma of oral traditionwhich is inevitably

flexibleand adaptive,even thoughit believesin an unchangingtradition.But

again is thisa fundamental or a relativedifference? For the problemthatI am

dealingwith-whencethemagicalpowerof sacredwords-this distinction again

is by itselfinsufficient.

The sharpdisjunction betweenthecase of a writtenholy

languageand a secularlanguagein higherreligionis paralleledin theTrobriands

by a weakerdisjunction, nevertheless of thesamekind,betweentheelementsof

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I 82 S. J. TAMBIAH

archaicor esotericlanguagein theorallytransmitted spellsand thelanguageof

ordinaryuse. Many 'primitive'peopleswho recitetheirreligiousmythology in

saga formdo so in an 'archaic'formof speechwhichis onlybarelycomprehen-

sibleto contemporary speakers, e.g. thisis thecaseamongtheKachin.The pointis

thatas long as religionbothin literateor pre-literate societiesharksback to a

periodofrevelation and insistson theauthority ofproperlytransmitted truetexts

eitherorallyor in writtenform,itssacredlanguagewill containan archaiccom-

ponent,whetherthisis represented by a totallydifferent languageor olderelements

of thesamelanguage.

It is perhapsrelevantto note,wheneverwe meetsuchformalised oralor written

texts,thattheir'archaicness'mayalsobe related to the fact thatthey arecomposed

in a specialstyle, which uses highly symbolic devices, speciallycoined words,and

words without meaning to fillin gaps(Vansina I965). Furthermore writing perse,

madepossibleby thealphabet,by givinga physicalexistenceto words,maylend

added veneration to writtentexts.Thus it is not at all accidentalthatthepresent

day term for the major alphabetin Indiais Devanagari(theabode of theGods).

Another criterion-thatof the degree of specialisationand trainingand

differentiation of religiouspersonnel-isagain of littlevalue in accountingfor

thebeliefin thepower of sacredwords.It is frequently truethatthesocietiesin

whichthehigherreligionsexistare stratified, thatliteracyitselfis specialisedand

thevastbulkofthepopulationdependson speciallytrainedintermediaries, andthat

theprofessional priesthoodis separatedfromlay occupationsand modes of life.

But specialised skills,subjectionto taboos,and exclusiveknowledgeof sacredlore

are in varyingdegreecharacteristic of thereligiousexpertsof simplernon-literate

societiesas well.

FinallythefactthatthePali chantsofBuddhismarenormally notstrictly under-

stood by thelaitybut thatthelanguageof Trobriandspellsis largelyintelligible

to theTrobrianders hasnotproducedanysignificant differencein theattitudeto-

wardssacredwords.Thisis so becausefortheBuddhistlaymanthefactthathe does

not understand does not mean forhim thatthe chantsare mumbo-jumbo.He

believesquite rightlythatfor thosewho know Pali the words containgreat

wisdomandsense;hisignorance isa reflectionofhisunworthiness andinvolvement

in an inferior modeoflifecomparedwiththatofthemonk.I havethuscometo the

negativeconclusionthattheremarkable disjunction betweensacredand profane

languagewhichexistsas a generalfactis not necessarily linkedto the need to

embodysacredwordsin an exclusivelanguage7or in writingand,secondly,that

both higherand lower religionsportrayno qualitativedifferences in respectof

theirbeliefsin revelation and trueknowledge,specialisation ofreligiousoffice,and

attitudes to sacredlanguageswhetherthoselanguagesare understoodor not.

It therefore appearsnecessary to tryto formulate a generalstatement aboutthe

widespread beliefinthemagicalpowerofsacredwords.No book on religionorthe

originsof languagefailsto referto thisancientbeliefin thecreativepowerof the

word. It would be possibleto confirmthisbeliefin the classicalliterature. The

Vedic hymnsspeculatedon vac (theword) and assertedthatthe gods ruledthe

worldthrough magicalformulae;theParsireligionstatesthatinthebattlebetween

good and evil it was throughthespokenword thatchaoswas transformed into

cosmos; ancientEgypt believedin a God of the Word; the Semitesand the

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE MAGICAL POWER OF WORDS I 83

Sumerianshave held thattheworld and itsobjectswere createdby theword of

God; and theGreekdoctrineof logospostulatedthatthesoul or essenceof things

residedin theirnames.But commentators haveentangledthemselves in thesome-

whatbarrendebateaboutwhethersuchideasasserted thatthewordinitsown right

was powerful,or whetherit actedthroughtheparticipation ofthesupernaturalor

throughtheagencyoftheLord'sanointed.What has not beenseenis thatwithin

anysinglereligioussystemmultiplevaluesaregivento thecharacter androleofthe

sacredlanguage,and thatthesevaluestakentogether forma setofthreepostulates

in mutualtension.

The Bible can conveniently thistrinity

serveto illustrate ofideas:

i. The firstidea is thatGod createdtheworldby assigningnames.'And God

calledthelightDay, and the darknesshe calledNight' (GenesisI.5). (Together

withthisgoes theidea in certainreligionsthattheCreatorGod createdhimself by

uttering hisown name.)

2. The Bible also asserts the directlyoppositeidea thatafterGod had created

heavenand earth,man assumed thenamingfunction throughspeech.'And out of

thegroundthe Lord God formedeverybeast of thefield,and everyfowlof the

air; and broughtthemuntothemanto seewhathe would callthem:and whatso-

everthemancalledeverylivingcreature, thatwas thenamethereof.. .' (Genesis

2. I9-20).

3. Thereisyeta thirdcharacter whichis

assignedto theword: thatitis an entity

able to act and produceeffectsin its own right.Thus we readin Isaiah(55.II):

'. . . So shallmy word be thatgoethforthout of my mouth:it shallnot return

untome void,butitshallaccomplishthatwhichI please,anditshallprosperin the

thingwheretoI sentit.'

TheseBiblicalnotionsexpressHebrewconceptsandI thinkcometogether in the

firstlinesof the Gospelaccordingto St Johnwhichalso explicitlyrefersto the

Greeknotionof logos:theword was in thebeginningwithGod, theword was

madefleshinJesusChrist,and thosewho receivedChristbecamethesonsof God

and theword dweltwiththem.

in Buddhismwhichconstantly

It is thesethreenotionsthatare also reflected

affirms itsthreegems:theBuddha,theall-enlightened one,was thesourceof the

sacredwords;theDhamma,thedoctrines preachedby theBuddha,and inscribed

in thetextsarethemselves holyobjectsin theirown right,and can transmit

virtue

and dispelevil; and the Sangha,the monasticorderwhose ordainedmembers

practisegood conduct,is the mostappropriate agentfora recitalof the sacred

words.

Thesenotionsarealsorepresented in Trobriandthought.Considerthefollowing

Trobriandpropositions:

i. Magic appearedwiththefirst ancestors

and cultureheroes,togetherwiththe

gardensandnaturalphenomenatheycreated.'Magic is a thingneverinventedand

nevertampered with,bymanor anyotheragency'(MalinowskiI960: 402). Itwas

handedoverto manwhose descendants it in unbrokensuccession.

have inherited

2. At thesametimetheTrobriands human

conceivedof magicas an essentially

possessionespeciallyof theaccredited

magicians.Malinowskiassertedthatforthe

nativemagic was 'not a forceof nature,capturedby man . . . and put to his

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

184 S. J. TAMBIAH

service;it is essentially

theassertionof man'sintrinsic

powerovernature'.It was

the humanbellythatwas thetabernacleof magicalknowledgeand theforceof

magicresidedin manand could 'escape onlythroughhisvoice' (I960: 409).

3. Finally,the Trobrianders also had the notionthatmagicalformulae,once

voiced,actedand influenced thecourseof events.Hence theirinsistence

thatthe

spellwas themostimportant componentof magic,a view also heldfirmlyby the

Dobuans (FortuneI963: IOI).

Thus it is clearthatwe aredealingwiththreenotionswhichforman interrelated

set: deitiesor firstancestorsor theirequivalentsinstituted

speechand the classi-

fyingactivity;man himselfis the creatorand user of thispropensity;finally,

language as such has an independent existenceand has the power to influence

reality.

I would suggestthatit is theperception of thesecharacteristics

of languagethat

has perhapsbroughtabouttheelevationof theword as supremely endowedwith

mysticalpower. Let me explain.Thereis a sensein whichit is trueto say that

languageis outsideus and givento us as a partof our culturaland historical

heritage;at thesametimelanguageis withinus,it movesus and we generateit as

activeagents.Since words existand are in a senseagentsin themselves which

establishconnexionsand relations betweenbothman and man,and man and the

world,and are capableof 'acting' upon them,theyare one of themostrealistic

representations we have of the conceptof forcewhich is eithernot directly

observableor is a metaphysical notionwhichwe findnecessary to use.

In respectof religionand ritual,the threenotionsin theirwidestextension

correspondto thefollowinglevelsofbehaviourwhichwe meettimeand againin

manysocieties:

i. The domainof mythwhichrelatesstoriesabout the doingsof savioursor

prophetsor ancestors and thearrivalof themessage,be it doctrineor magic.

2. The ritualor magicalsystemitself, i.e. thelinguistic structure of thesacred

wordsand thegrammarof thenon-verbalactsthatgo withthem.

3. The presentday humanpriestsor magicians,theirsacredstatus,theirlinks

withthesavioursor ancestors and theirspecialbehaviourand preparations which

make theirritualpracticeseffective.

Anyexhaustivestudyof religionand ritualneedsto studynot onlythoselevels

but also thefunctional relationsbetweenthem.But thereis againanothermajor

relationshipto be unravelled,

a relationshipthatis difficult

to establish

ina meaning-

ful sense,and is leastwell-established

in anthropology. This is thelinkbetween

religionand ritualand thedomainsof socialand practicalactivities intowhichit

penetrates and whichit influences but is also at thesametimeseparatedfromin

somefashion.8

To returnto my majorthemewhichis the basisforthebeliefin the magical

power of words: I have takentheinquiryup to a certainpoint,but thehardest

partoftheexerciseisyetto come.Ifourdefinition ofritualis thatitis a complexof

words and actions(includingthe manipulation of objects)thenit remainsto be

shownwhatpreciselyis theinterconnexion between thewordsandtheactions. This I

shallattempt to showin respectoftheTrobriandmagicalsystem, payingparticular

attention to theverbalcomponent.BeforeI can do this,it is necessary to clearthe

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE MAGICAL POWER OF WORDS

reviewingboththetheoryoflanguagewhichMalinowskihim-

decksby critically

selfpropoundedto explainTrobriandmagic,and also certainotherattempts

by

philosophers

andlinguiststo accountforthebeliefin verbalmagic.

Theoriesofmagical language

Malinowski'sviews on languagecan be roughlydividedinto two related

theories,one pertainingto whathe calledan 'ethnographic theoryoflanguage'in

general,and theotherto thelanguageofmagicin particular.

The chieffeature ofhisgeneraltheorywas thepragmatic character oflanguage.

Languagewas notso mucha vehicleforexpressing ideas,conceptsor categories, as

forachievingpracticaleffects. We recognise in thisstanda self-conscious attackon

the mentalistic theoriesof languagecurrentin his time,such as thoseheld by

Sweet and Sapir(I92I). Malinowski'sapproachto languagecorresponded with

his approachto mythand magic: anti-intellectualistic, non-explanatory, seeing

themsimplyas hard-worked toolsforpracticalliving.

Malinowskimade no distinction between'langue' and 'parole',languageand

speech.His analysiswas specificallyrelatedto thespeechcontext.Speechwas a part

of concertedactivity,like gestureand motion,'an adjunctto bodilyactivities'.

Wordswerea partof actionand wereequivalents to actions(i965b: 9). It is from

thisperspective thathe developedhis 'contextualtheoryof meaning'and the

notionofthe'pragmaticsetting ofutterances'. The roleoflanguagecouldonlybe

understoodin relationto otheractivities;languageregulatedconcertedwork,

transmitted knowledgeand set in motiona seriesof tribalactivities, and 'the

effectiveforceof suchverbalactsliesin directly reproducing theirconsequences'

(i965b: 49).

His definitionof 'meaning' was a logical derivative fromhis pragmaticpers-

pective:'Meaningis theeffect ofwordson humanmindsandbodiesand through

theseon the environmental realityas createdor conceivedin a given culture'

(i965b: 53). Comparethisformulation withthatofstructural linguisticsforwhich

the speakerand thelistenerare contingentand belong to 'la parole', whereas

meaningis therelationbetweensignand thethingsignified, between'significant'

and 'signifie',whichbelongto theengraphicsystemof 'la langue'.9,

Linguists Malinowskiforconfusing

havecriticised thecontextof situation with

otherlevelsofanalysis pertainingto languagequalanguage(J.R. FirthI957). It was

hispassionforviewingwordsas a partofactionthatmadeMalinowskiarguewith

excessiveflourish thatwordshadno existence andthattextsdivorcedfromcontext

weremeaningless. Thesearguments weredirectly contravened by himbecausehis

expositionin Coralgardens andtheir magicwas in termsofa wordforwordtransla-

tionanda commentary on recordedtexts.It was thesamehistrionic talentthatled

himto dwellon theproblemof meaningless wordsand the'coefficient of weird-

ness' in magicallanguage.In facthis translation was excellentand he concluded

thatthe'coefficient in thespellswas high.His strategy

ofintelligibility' ofteasing

thecredulousreaderand takinghim on a circuitous and repetitious route,strewn

withhis sinsof commission and omission, was adoptedso thata dramaticanswer

could be producedin theend,whichwas thatmagicallanguagewas eminently

intelligible.And he graciouslyconcededthatthe untranslatable wordswere un-

translatablebecausehe failedto gettheservicesof a 'competentcommentator'.

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

i86 S. J. TAMBIAH

Malinowskichose not to followthe perspectives offeredby thisfindingand

maintained thatmagicallanguageworkeddifferently fromordinary speech.The

difference was thatmagicalutterances were believedby the nativesto produce

supernatural effectswhichtheydid not expectordinaryspeechto produce.The

verybasisofverbalmagicwas the'creativemetaphorofmagic',whichsuggestive

phrasehe interpreted as 'the beliefthattherepetitive statement of certainwordsis

believedto producethe realitystated'(I965b: 238). This beliefagain,thatthe

knowledgeof a name or the correctrepetition of a formulaproducedmystical

effects, Malinowskitracedto mythological associations

or,as he putit, 'some other

aspectof Frazer'sprincipleof sympathy'(i965b: 232). The implication is thatthe

laws of associationthatapplyto ordinaryspeechdo nothold formagicalspeech,

an inference thatinevitably led Malinowskito thebarrenconclusionthatmagical

languageis objectively a delusionand 'irrational in nature'.'The essenceofverbal

magic,then,consistsin a statement whichis untrueand whichstandsin direct

oppositionto thecontextofreality.. .' (i965b: 235). He thussearchedforanother

kindofrationalreasongroundedin individualpsychology fortheobjectively false

use ofmagicallanguage.

Therewas howeveranotherstrandin Malinowski'sthoughtwhichled him to

posit a ratherdifferent relationbetweenmagicaland ordinarylanguage.The

questionwas,how did mancometo believein thefirst placein themystical power

ofwords?He arguedfromhispragmatist andbehaviourist premissesthattherewas

a realbasistothehumanbeliefinthemystic and bindingpowerofwords.Language

gave man thesenseof poweroverhisenvironment. 'The beliefthatto know the

nameof a thingis to geta hold on it is thusempirically true'(I965b: 233). Thus

althoughhe saw in magicallanguageobviousdistortions of ordinary languagein

the directionof mysticism, bothengenderedthe beliefin the creativeforceand

pragmaticpower of words which he tracedto childhoodexperience.A baby

reactsto bodilydiscomfort withcrieswhichattractthe mother'sattention, and

laterthechild learns that the utteranceis theessenceofwelfareandthatitactsupon

theenvironment to satisfy itsneeds.Here liestheearlymagicalattitude to words,

thata name sufficiently repeatedcan mraterialise

often thething.

Now thisbiographical theoryis subjectto thesamecriticisms whichhavebeen

directedagainstMalinowski'sattempt to accountfortheclassificatory categoriesof

kinshipin termsof ego-centred extensions. Furthermore, thistheoryis question-

beggingbecausethe notionof languageis priorto a child'scomprehension of

language.It is becauseadultsrespondto thecriesas meaningful, anddirecta child's

efforts at communication, thata child learnsthe conceptand use of language.

Finally, the random acts of a babyare susceptible of diametrically opposedinter-

pretations:Malinowskisaw the child's physicalgraspingmovementsas the

beginnings of itsbeliefin thepower to controltheenvironment, whileCassirer

(I966: i8i) saw thedisplacement of thegraspto a pointingor indicativegesture

as thegenesisof symbolicbehaviour.

I tumnow to certainothertheorists of languagewho havetriedto accountfor

the primitive's'magical attitudeto words'. I shallbrieflymentionthe ideas of

Ogden & Richards (I923), Izutsu (I956) and Cassirer(I953). Ogden and

Richards'slinguistic and philosophical arguments in The meaning ofmeaning (for

whichMalinowskiwrotehis classicsupplement) happilyconvergedwithMalin-

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE MAGICAL POWER OF WORDS 187

owski's argumentsbased on anthropologicalfield experience.Unlike those

theoristsof todaywho hold theelevatedview of languagethatit is thebasisof

categoricalknowledge,Ogden and Richardswere impressedwiththe delusions

producedin manby language,'a mediumdevelopedto meettheneedsofarboreal

man' and therefore a cumbersome instrument forcontemporary needs.Theysaw

therootsofthemistaken beliefin themagicalpowersof wordsin thesuperstition

thattherewas a direct,even causal,relationbetweentheword and thethingit

referredto,betweensymbolanditsreferent. The denotative fallacyexplainedman's

logophobia.

Thereis one simpleretortto thistheory.It is perfectly conceivablethatspeakers

of a language,especiallythosewho are unawarethatthereare otherlanguagesin

existence,may thinkthatwords are not arbitrary and conventionalbut truly

represent theobjectstheystandfor.But surely,ifmanycontemporary Westerners

who maybe victimsofthisfallacydo notthereby thinkthatby sayinga wordthey

can conjureup a thinginto existence,it is amazingthatwe can contemplate

attributingthismagicaloutlookto theprimitive. Thiscavalierattitude ofinvesting

is

the savage with linguisticpathology portrayedby another writer who has

advanceda connotativetheoryof the originsof verbal magic. Izutsu (I956)

describes withgreatperceptiveness thecapacityof wordsas symbolsto evoke in

our mindsreferences and images.Extra-verbally, wordsenableusto re-experience

past events,intra-verbally theyevoke the associativenetworksbetweenwords

withinthelanguagesystem.All thisis impeccable,but whatwarrantis thereto

speculatethatprimitive manbelievesthatwordsproduceimagesas concrete reality?

Cassirer(1953) propoundeda philosophical cumlinguistic theoryto accountfor

thebasisand originof theword veneration reflectedwidelyin religiousthought.

He opposedmythicthoughtto theoretical discursivelogicalthought, thetwopoles

in an evolutionary continuum, and directlylinkedtheevolutionof religiousideas

to theevolutionof linguistic notions.Sinceit was languagewhichactuallypro-

duced theorganisation of realityand shapedtheformsof predication, the con-

trastingcharacters of mythicthoughtand logicalthought,he argued,would be

reflectedin man's attitudeto language.Cassirerrelatedthe phenomenonof the

hypostatisation oftheword(whichimpliedthenotionthatthenameofa thingand

its essencebear a necessaryand internalrelationto each other)to the mythic

consciousness andimagination ofearlymanwho first graspedhisexperience ofthe

world throughseparatemythicalimages. Mythicimagination'tends towards

concentration, telescoping, separatecharacterization' of images.In the sphereof

languageit resultsin thebeliefin word magic,in attributing a physico-magical

powerto theword,andin a relationofidentity andsubstantial unitybetweenname

and thing.Logical thoughtwhichis a laterdevelopmentin man has an entirely

differentattitudeto theword,whichis seenas a symbolandvehiclewhichmediates

betweentheimmediatedata of senseimpressions and ideation.Being theoretical

and discursive, logicalthought'tendstowardsexpansion,implicationand syste-

maticconnection',and towardstheestablishment of relations betweenphenomena

whichare 'alike' accordingto someco-ordinating law.

Cassirer'stheory,whichappealsto shakyethnography, is in factan imaginary

and speculativeevolutionary schemeof religiousideasand language.In so faras

Levi-Strausshas demonstrated the logical and relationalcharacterof mythic

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

i 88 S. J. TAMBIAH

thought,Cassirer'sbasicdichotomyof modesof thoughtdisappears. And ifit can

be demonstrated thatprimitivemagic is based on truerelationalmetaphorical

thinking we shallexplodetheclassicaltheorywhichpostulates thatmagicis based

on the beliefin a real identitybetweenword and thing.The basic fallacyof

linguistsand philosophers who searchfortheoriginsof the magicalattitudeto

wordsis theirpriorassumption and accceptancethattheprimitive hasin factsuch

an attitude.This axiom theyhave derivedprincipallyfromFrazer,and indeed

fromMalinowskiwho had affirmed thetruthof thisclassicalassertionon thebasis

of his fieldwork.It would perhapshave been saferforthelinguists to have held

fastto theirknowledgeof how languageworksand to have questionedwhether

anthropologists had correctly reportedprimitivethought.

BeforeI concludethissurveyI shouldreferto anotherfeatureof thetheoryof

languageformulated by Ogden and Richardswhich did not appeal to man's

evolutionbutto a synchronic schemewhichfittedbeautifully withMalinowski's

assertions. They postulatedtwo usesof speech:thescientific use in whichwords

symbolised a reference

whichcouldbe verified in relationto externalreality;and

theevocativeor emotiveusein whichwordssimplybecamesignsforemotionsor

attitudes,theirreferentialpowerbeingsecondary. I. A. Richards(1938) arguedthat

poetrymade itsimpactthroughthe emotiveuse of language.Malinowski,too,

assertedthatmagicallanguagewas an emotiveuse of language,thatmagicwas

bornoftheemotionaltensionofparticular situationsand thatthespells,ritualacts

and gestures expresseda spontaneous flowofemotions.When carriedawayby his

own emotiveuse of language,he even arguedthattheparaphernalia and ritual

substances ofTrobriandmagicwereusedas theyhappenedto bearon thepurpose

of theact throughemotionalassociation(MalinowskiI948: 53). Thesestatements

do not do justiceto thehighlyformalised natureof Trobriandrituals.And as for

emotiveuse of words,Richards'sviewsfindtheirmatchand corrective in Leach

(I964) who hasdemonstrated thateven the mostemotivewordsof abusehavea

referential and structuralbasis.

A re-analysisofTrobriand ritual

If I am criticalof thesetheoriesI shouldtryand providean alternative view of

how thelanguageofritualworks.I shallattempt ofsomeaspects

a briefre-analysis

of Trobriandmagicin orderto demonstrate mypointof view. But firstI should

outlinetheschemeand assumptions thatguidemyanalysis.

Trobriandmagicallanguageis intelligiblelanguage,not mumbo-jumboshot

throughwith mysticalideas not amenableto rationalexamination.It is not

qualitatively'different'fromordinary language,butis a heighteneduse ofit.The

samelawsofassociation thatapplyto ordinarylanguageapplyto magicallanguage.

Trobriandmagicis a clearcase of a systemthatcombines,moreoftenthannot,

word and deed, languageand action.Thereforeratherthananalysethe words

separatelyfromtheactionswe shouldfinda way oflinkingthem.

This difficultinquiryI call the 'innerframe'of Trobriandmagic,and it deals

withthetechniqueoftransfer, themannerin whichspellsareconstructed, thelogic

of choice of the substances used,and the mode of synchronisation of linguistic

deviceswiththoseofnon-verbalactionin a structured sequence.We maycallthis

perspectivethe 'semantics'of Trobriandritual.

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE MAGICAL POWER OF WORDS I89

I use the term'outer frame'to referto anotherlevel of meaning.Here the

ritualcomplexas a whole is regardedas an activityengagedin by individualsor

groupsin pursuitof theirinstitutional aims.This perspective we may call 'prag-

matics',and it corresponds in somewaysto whatMalinowskicalledthe'context

of situation'.It investigates how ritualrelatesto otheractivities, in whatcontexts

and situations it is practisedand what consequencesit may produceforvarious

segments of thesociety.

At thecostof oversimplifying one could saythatthereare two perspectives for

viewingthisrelationship betweenritualand otheractivities: ritualcan be seenas a

stimulus or signalforactivities thatfollowin time,e.g. in thecase of prospective

magicexemplified by Trobriandagricultural and canoe magic,and as a response

to precedingevents,e.g. in thecase of 'retrospective' ritual,a good exampleof

whichis witchcraft.

In investigating how languageand actionare synchronised in Trobriandmagic

I havefoundit usefulto elaboratea suggestion madebyJakobson(I956). Having

discussedtwo devicesor operations in language,themetaphoric and metonymic,

whicharebasedon theprinciples ofsimilarity andcontiguity, he indicateda formal

correspondence betweenthemand Frazer'sdivisionof magicinto'imitative'and

'contagious' kinds also based on the principlesof similarityand contiguity.

Frazer,youwillrecall,usedtheseprinciples not in relationto thewordsbutto the

objectsusedand actionsenactedin magicalrites.

In respectoflinguistic operations theconceptof metaphor presents no problem.

The dictionary meaningis thatit is a figureof speechin whicha name or des-

criptivetermis transferred to some objectto whichit is not properlyapplicable.

The implications of metaphor(whichis a shorthand expressionI use to include

simileand analogy)are thatit is a surrogatewhichhas a dual reference to the

originalobject and to the object forwhichit now stands.Every metaphoror

symbolcontainsbothtruthand fiction:ifit is takenliterally it misrepresents,but

it is more than a conventionalsign because it highlightsa resemblance.The

metaphoris a mode of reflection and enablesabstractthoughton the basis of

analogicalpredication (Urban1939). In termsofJakobson's formulation,themeta-

phoricuse of languageexploitsthe proceduresof selectionand substitution by

whichwordsor ideasreplaceone anotherin termsofsemanticsimilarity.

Contemplate whatimplications thisdevicemayhaveforritual,whichhasforits

aim theactualtransfer of an attributeto therecipient.The spellcan exploitthe

metaphorical use of language,whichverballyand in thoughtmakesthetransfer.

Thereis no trickhere; it is a normaluse of language.The verbaltransfer is an

exampleof whatwas calledin traditional theologytheanalogyof attribution.

The dictionary meaningof metonymy is a 'figureof speechwhichconsistsin

substituting forthename of a thingthename of an attribute or partof it', e.g.

when'sceptre'standsfor'authority'. Thisisa caseofthepartstanding forthewhole

based on the contiguity principle.If a metaphoris a substitute, a metonymis a

complement;bothinvolveverbaltransfer. Jakobsonexpandsthenotionof meto-

nymyto discusslinguisticoperations, based on the principlesof contiguity and

contexture, whichenable the formulation of complexformsof linguisticunits

accordingto syntactic rules:therulesby whichwordsare combinedand strung

togetherto formsentences and sentences combinedto formutterances.

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

190 S. J. TAMBIAH

Now metonymy as traditionally understoodand expandedbyJakobsonsheds

lighton thestructure of Trobriandspells.Frequentlythe variouspartsor con-

stituentunitsoftherecipient ofthemagic,whetheritbe a canoeor a humanbeing,

are enumerated and the magicaltransfer made to each of them.Thus we get a

realisticpictureofthewholebuiltup fromtheparts,andthismetonymic technique

has severalimplications forlendingrealismto therite,fortransmitting a message

throughredundancy, forstoringvitaltechnological knowledgein an oralculture,

and fortheconstruction of thespellitselfas a lengthyverbalform.

Both linguisticprocedures,metaphoricalthroughsubstitutionpermitting

abstractions, and metonymic throughbuildingan organicwholethroughdetails,

areaccompaniedin Trobriandmagicby action.

Objects and substancesare used as agentsand vehiclesof transfer through

contagiousaction.In thesevehiclesof transfer we findexpressedFrazer'ssub-

stitution (or similarity)and contiguity imitative

principles, and contagiousmagic,

but neverin an exclusivemanner.A close analysisof Trobriandritualshows

that it activelyexploits the expressivepropertiesof language, the sensory

qualitiesof objects,and the instrumental propertiesof action simultaneously

in a numberof ways. The semanticsof ritualare more complex than sug-

gestedby Frazer'sprinciples whichlead to absurdinferences about the logic of

magic.

Now we are in a positionto see how thesepropositions hold in detailin the

Trobriandcase.

Malinowskiconsideredthe spell (yopa)as the most importantconstituent of

Trobriandmagic.The magicalritestook two forms.In one, spellswere uttered

withouta concomitant rite(i.e. manipulation ofobjects),butthisabbreviated form

was notpractised in themajorrituals.In theother,whichwas themoreimportant,

thespellswere accompaniedby simpleritesof 'impregnation'or 'transference',

which shareda commongrammar.I'Typically,certainsubstances(e.g. leaves)

werebroughtintocontactwithan objectsuchas an adze,or a lashingcreeper,or a

pregnancy cloak,andspellswereuttered closeto themso thattheybecamecharged;

theseobjectsin turntransferred theirvirtueto thefinalrecipient

ofthemagic.Thus

thewayugocreeper,whichwas usedforlashingtogether theparts,impartedspeed

to thefinished canoe,andthecharmedmedications of kulabeautymagicconveyed

beautyand attractiveness to thevoyager.

The mostelaborateTrobriandspellshad threeconsecutive parts:theu'ula,the

tapwanaand the dogina.The meaningsassociatedwith u'ula are 'foundation',

' cause','beginning','firstpossessor','reason'; thetapwanahad a similarcoherent

rangeof meanings:'surface','skin', 'body', 'trunk','middle part', and 'main

part'; thedoginameant'tip', 'end', 'tail', or 'finalpart'.The threepartsappearto

presentthe followingprogression. The u'ula,whichis brief,statesthe basison

whichthespellis constructed, firstly themajorthemeor metaphorical idea which

is elaboratedin the spell and secondlythe mythicalheroesand ancestorswho

wielded the magicalpowersin questionand withwhom the magicianhimself

becomesidentified. This secondfeatureis theportionof thespellthatrelatesthe

to

magic myth, which I do not discuss.The tapwanais thelongestand mainpart

on whichwe have to concentrate in orderto seehow thespellis constructedandto

the

unravel logic and techniqueof therite.The dogina,whichis also brief,is a

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE MAGICAL POWER OF WORDS I9t

statement thattheintendedeffect has beenachieved.It is clearthattheTrobriand

spellis constructed as an orderedprogression.

Malinowskidescribedthe tapwana as a 'continuousstreamof utterance'and,

important forus,he statedthatthismainpartoftheformulawas easierto translate

thanthe u'ula becauseit was expressedin a less condensedformand in words

approximating ordinary language.We are thusfacedherewithdescriptive refer-

entiallanguageratherthanuntranslatable language.

In thesimplerkindofspella listofwordsis repeatedin sequencewithchangesin

keyexpressions. The listis an enumeration oftheconstituentpartsof a canoe,or a

of

yam house,or theanatomy theperformer. These wordswe may looselycall

' substance words'.The keyexpression is an actionwordor a verb.The logicofthe

is

recitation thateachpartenumerated undergoesan eventor processby whichit

acquiresthedesiredattribute quality.(Examples2 and 3 in diagrami illustrate

or

thisconstruction.) Alternatively a singlesubstance word or nounmaybe attached

to a

in succession series verbsof which represent rangeof relatedstatesor pro-

a

cesses(seeexample ia in diagrami).

A morecomplexstructure consistsof theuse of two seriesof key expressions,

one consisting of thebodypartsof therecipient, to eachof whicharetransferred

energiesrepresented by anotherseriesofverbs(seeexampleib).

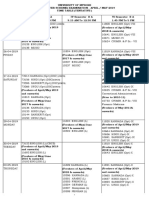

DIAGRAM I. The structureof Trobriandspells(withspecialreference

to thetapwana)

ExampleI. The striking

of thesoil.Formula2 in Coralgardensandtheir

magic.

a. The bellyof mygarden - leavens

rises

reclines

growsto thesizeofa bushhen'snest

growslikean anthill

risesand is boweddown

risesliketheironwoodpalm

liesdown

swells

swellsas witha child

b. Listi (gardenpests) List2

thegrubs -->I sweepaway

theinsects I blow

thebeetlewiththesharptooth I driveoff

thebeetlethatbores I sendoff

thebeetlethatdestroysthetarounderground I chaseaway

thewhiteblighton taroleaves

themarking blight

theblightthatshines

Example 2. Anchoringthegarden(after anderecting

planting posts).FormulaIOinCoralgarden

andtheir magic.

Partsof thegardennamed:

soil 'shallbe anchored'

magicalprism(kamkokola)

yampole (kavatam)

branching pole (kaysalu)

stemsavedfromthecutting (kamtuya)

trainingstick(kaybudi)

uncharmed prism(kaynutatala)

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I92 S. J. TAMBIAH

partition

stock(tula)

slendersupport(yeye'i)

boundaryline(tuklumwala)

boundarytriangle(karivisi)

lightyampole (tamkwaluma)

tabooingstick(kaytuvatova)

greatyampole (kayvalituwa)

Example3. Post-harvest magicofprosperity-the

secondactofvilamatia magic (anchoring

the

yamhouseand village).Formula29 in Coralgardens

andtheirmagic.

Partsof theyamhousenamed:

cornerstone(ulilaguva) 'slhallbe anchored'

floor(bubukwa)

log house(liku)

compartments (kabisivisi)

youngsproutof taytuyam(sobula)

sticksthatdividethelog cabin(teta)

decorated frontboard(bisiya'i)

gableboards(kavalapu)

supports of thatch(kiluma)

roofbatten(kavala)

rafters(kaliguvasi)

thatchbattens (kivi)

lowerridgepole (kakulumwala)

thatch(katuva)

upperridgepole (vataulo)

ornamented endofridgepole (mwamwala)

Other examples, which show the same regularityof structure,are:

i. The kayikuna sulumwoya spellin kulabeauty(mwasila)magic(I960: 439).

In thisspellfirsta man'skulaobjectsareenumerated and eachis saidto 'boil'; nextthe

performer's own headparts are enumerated and eachin turn'boils' ('to boil', 'to foam',

'to stir'are frequentlyusedto represent activation):

Inventory ofkula objects

My mintplant(boils); myherbornament, mylimespatula,mylimepot,mycomb,

mymat,mypresentation goods,mypersonalblanket,mymagicalbundle.

Headpartsenumerated

My head (boils); mynose,myocciput,mytongue,mylarynx,myspeakingorgan,

mymouth.

2. The renownedwayugo(lashingcreeper)spell used in canoe buildingmagictransfers

speedto thecanoeunderconstruction (I960: 43I). We shouldnotethattechnically the

lashingcreepermaintains the cohesionof the variouspartsof the canoe. Here is an

enumeration of the canoe,each of whichis followedby the verb

of the constituents

'mightheel over' (i.e. overtake):

Inventory ofcanoeparts

I (mightheelover); mykeel,mycanoebottom,myprow,my rib,my threading

stick,myprowboard, my transverse board,mycanoeside.

Therearesomereadilycomprehensible featuresin thespellsconstructed

on such

simpleprinciples."Such permutations with words allow for a great deal of

repetitivenesswhichMalinowskireferred to as theprosaicpedantryof Trobriand

magic. Today in the lightof communication theorywe would say thatthe

redundancy is a deviceusedin ritualto transmititsmessage(CherryI96I), a point

thathas alreadybeenarguedby Leach (I966).

Anotherimplication oftherepetitive pattern,whichin contemporaryjargon we

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE MAGICAL POWER OF WORDS I93

would call 'storeof information' or 'memorybank' in the absenceof written

language,was noted casuallyby Malinowski.Commentingupon theKudayuri

canoe mythwhichcontaineda detailedaccountof canoe partsand theirbuilding

sequence,Malinowskiwrote:'lHe [thenative]is quiteusedto reciteone afterthe

otherthevariousstagesofcustomary proceedings inhisownnarratives, andhe does

itwithan almost pedantic accuracy and completeness, and it is an easy taskforhim

to transferthese qualitiesto theaccounts which he is called upon to make in the

service of ethnography' (I960: 3I8). It is clear that the spells and myths contain

information, whichis not theremainsof archaicbeliefs,but a livingknowledge

relatedto technological and socialactivities.

Furthermore, and thisI would emphasise,the spellsI have cited portraya

metonymic use oflanguage,i.e. linguistic operations in termsof combination and

context,basedon contiguity principles. All thepartsof a canoe,or a humanhead

or a yamhouse,comprisea configuration or a setby virtueofcontiguousassocia-

tionwhichwhensystematically variedwithactionwordscreatesa long utterance.

Metonymyso used lendsa 'realistic'colouringto thedescription.

Now each utterance soundsas if it statesan imperative transference, e.g. 'The

bellyof my gardenswells'or 'The floorof myyam houseshallbe anchored'.It

is a commonview,also sharedby Malinowski,thata magicalspellis identifiable

by itsinsistentuse of imperatives and thatthisprovidesthe evidenceforsaying

thatprimitives believethatwordscreatetheireffects by theirveryutterance. This

howeveris notthecase.The verbalassertion is mediatedby a middletermwhichis

thesubstance(or materia medica)intowhichthespellsare uttered;and thesesub-

stancesin turnconveytheattribute to thefinalrecipient. It is therefore necessary

to investigatetheroleofthesemediatingsubstances.

Let us takeas our examplethe substances used in two contrasting ritesin the

gardeningcycle.The inauguralriteof thefirstcuttingof thesoil,thefirstin the

cycle,hasforitspurposetheconferring of fertilityon thesoil; thevilamalia which

comes at the end is enactedafterthe storingof the yams,and seeksto confer

durability and permanence on theyamstocks.

DIAGRAM 2. The metaphorical

associations usedin tworitesin Omarakana

of substances

gardenmagic

(compiledfromCoralgardens andtheirmagic, vols. i and 2 and

ThesexuallIfeofsavages).

Substancesusedintheinaugural rite(first ofthesoil).

cutting

A. Leaves,plantsand creepers.

i. Yoyu:coconutleaves; 'theyare of the darkgreencolourwhichthe taytu (small yam)

leavesshouldhaveiftheyareto be strongandhealthy'.

2. Arecanut leaves:sameassociation as I).

3. Ubwara:wildplantwithlongtuberswhicharewhiteandbeautiful; usedso that'the taytu

in thegardenwillalsoproducebeautiful whitetubers'.(The whitecolouris associated

withfertilityandpurityin thepregnancy ritual.)

4. Kaybwibwi: whitepetalsof thefragrant pandanus;used so thatthe 'taytushouldhave a

pleasantsmell. . .' (Hereagainthesymbolism of 'whiteness'usedin pregnancy ritualis

relevant.)

5. Kubila:a plantwithscentedflowers;sameassociation as 4).

6. Sasoka:treewithbig roundbulkyfruit;usedto influence thesizeofthetaytu yam.

7. Wakaya:largestvarietyof banana;it has a massivetrunkswellingout neartheground;

sameassociation as 6).

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I94 S. J. TAMBIAH

8. Youla'ula:creeperwithwhiteflowersand luxuriant foliageresembling taytu foliage;used

so thatthetaytuwillhavethesameluxuriant foliage;also'whiteness'is associated

with

'pregnancy'.

9. a) Ipikwanada creeperwithluxuriant foliage,

b) Yokunukwanada J sameassociationas 8).

B. Earthysubstances.

IO. Ge'u: enormous moundsscrapedtogether by thebushhenforbreedingpurposes;'used

so thatthetaytumaygrowand swellup,likeone ofthesemounds'.

ii. Kaybu'a:chalkfromlargeboulders;association sameas io). Also notethesymbolism of

'whiteness'.

I2. Kabwabu: largeroundnestswhichhornetsmakein theground;'the taytushouldbe as

bulgingandlargeas one ofthesenests'.

Substances usedinVilamalia(prosperity

ofthevillagemagic).

A. Treesandplants;thematerials I-5 figurein thetwoactsofvilamalia magicwhich'anchor'

theyamhouseand thevillage.The metaphorical associationof theobjectsas regards

'anchoring'is clear.

i. Kakema:dwarf treewithpowerful rootsusedin thefirst actof vilamalia.

2. Lewo: stunted treereachingto veryold age,usedin thesecondact.

3. Setagava:toughweedwithstrongrootsusedin thefirst act.

4. Kayaulo:an extremely toughtreewhosewood cannotbe brokenbutcanbe cutwithan axe

or knife.

5. Leya:wildgingerusedin thesecondact; associated withfierceness andtoughness.

B. Othersubstances.

Binabina:stoneor volcanicrockimported fromthesouth;it is heavier,hardier andless

thanthelocaldeadcoral;thetwo stonesusedin theritualarecalled'thepressers

brittle

of thefloor'whichimparttheirqualitiesto thestoredfood.

The contrastin the meaningsof the materialsymbolsused is clear-cut(see

diagram2). In theinauguralritethesubstances broughtintocontactwithan adze

or rituallyplantedwhilethespellis recitedareluxuriant greenleaves,wildplants

whichproducelargetubers, plantswhichproducescentedwhiteflowers andtubers

(thewhiteconnotingfertility and sexualpurity),soil scrapedfromtheenormous

moundsmade by thebushhen,etc. In thevilamaliathesubstances usedconnote

hardnessand durability;toughweedswithstrongroots,wood of stuntedlong-

lived trees,hard volcanic rock, etc. The logic guidingthe selectionof these

is notsomemysterious

articles magicalforcethatinheresin them;theyareselected

on thebasisoftheirspatio-temporal characterslikesizeandshapeandtheirsensible

properties likecolourandhardness whichareabstract conceptsandwhicharegiven

metaphorical valuesin theTrobriandschemeofsymbolicclassification.

What thenis thegardenmagicianup to whenhe scrapessome soil froma bush

hen'snest,bringsitintocontactwithan adze,and recites'The bellyofmygarden

growsto thesizeofa bushhen'snest'?Is thisa caseofmystical contagionbetween

bushhenmoundand thesizeoftheyam,orisitsimplya metaphorical equivalence

setup verballybetweentheproperty of sizeportrayed by thebushhen'snestwith

thedesiredsameproperty in theyam,and lendingthementalcomparisonan air

of operationalrealityby usingthe soil of the bush hen's nestas a mediumof

transfer? The rite of transfer portraysa metaphoricaluse of language(verbal

substitution) wherebyan attributeis transferred to therecipientvia a material

symbolwhichis usedmetonymically as a transformer.Frazerwould simplyhave

describedtheprocedureas contagiousmagic.The techniquegainsitsrealismby

clothinga metaphorical procedurein the operationalor manipulative mode of

practicalaction;it unitesbothconceptand action,word and deed.

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE MAGICAL POWER OP WORDS 195

Confirmation is lentto thisargument whenwe scrutinise thespellsusedwithout

the mediationof materialsubstances, spellswhichthe Trobrianders call 'mouth

magic' (o wadola).A good exampleof thiscategoryis the magic of growth

performed in the middlephaseof gardening.The nativesare aware thatnature

mustdo itsworkand thatthecropshaveto sproutand growby themselves. The

magician'sfunctionis describedby Malinowskithus: 'In a rapidsuccessionof

rites,he hasto anticipate eachstagein thegrowthof thegardens, andstimulate the

variouscrucialphasesin thedevelopment of theplant. . .' (I96Sa: I39).

In thefollowingexamples,takenfromformulaeI3, I7 and I8 in 'The magicof

growth'(I96Sa: ch. 4), I statesome suggestivelinesand thenin parenthesis the

nativecommentary upon them.

FormulaI 3. 'O dadedatreethatsproutsagainand again'. (The nativecommentary

is thatthe'dadedais a plantof extremely rankgrowth;we cutit,alreadyit has

sprouted'.)The same formulacontainsothermetaphorssuggestingspeed of

growth:

'Thy shootsareas quickas theeyesofthekapapita, thequickbird,

Thy shootsareas quickas thekababasi'a, thequickblackants'.

FormulaI7. 'Thy head, 0 taytu,shootsalong as the millipedeshootsalong'.

(The nativessaythatthemillipedeis notedforitsrapidityof movement.)

Formulai8. 'Thy openspace,theopen spacebetweenthybranches, 0 taytu,the

spidercoversup'. ('The nativestoldme' reportsMalinowski'thatas thespider

spinshisweb, so slhouldthetaytuplantproducemanybranches'.)

It is obviousthatthemouthmagicdependsentirely on suggestive metaphors and

simileswhichtheTrobrianders themselves recogniseas such.It is puzzlingindeed

whyMalinowskiwho compilednoteson nativeexegesisshouldhaveinsisted on the

'pragmaticfunctionof words' and in thesamebreath'the mysticalassociations'

of magic.Thus, when in the wind-blowngardensthe Trobrianders invokethe

image of a dolphinplayingin thewater,Malinowskiinterprets the act as por-

traying'the mysticalassociationbetweentheundulatingmovementsof the dol-

phinand thewindingsand weavingsof thevine . . .' (I96Sa: I70).I2

Becauseof his commitment to his emotionaland pragmaticview of language,

Malinowskifailedto connectthesymbolism of theinauguralgardenmagicwith

thepregnancy ritualwhichhe described in The sexuallifeofsavages(I929). The

gardening magicconstantly refersto 'the bellyof mygarden'.Malinowskidenied

thatthisimpliedany metaphorical allusionto animalor humanfertility, but he

disarmingly wenton to say: 'My informants, as a matterof fact,commentedon

itin thissense. . . " taytu

is thechildofthegarden"' (I96Sb: 262-3).

Let me considerthepregnancy illuminates

ritual,forit succinctly theinnerform

of Trobriandmagicand also someof thebehaviourof thegardenmagician.

When a womanachievesherfirstconceptionthetabugu (womenof thefather's

matrilineage, chiefof whom is the father'sown sister)are chargedwith the

conductof thepregnancyritual.They preparetwo fibreskirtsand two mantles,

whitein colour;one setis wornby thepregnant womanat thecelebration ofher

firstpregnancy (aboutthefifth month)andthesecondsetafterchildbirth whenshe

emergesfromseclusionand returns to her conjugalhousehold.The mantlesare

thegarments ofspecialimportance on whichthesaykeulo magicisperformed. They

are placedon a mat,thefleshy lowerpartsof thecreamywhiteleavesof thelily

This content downloaded from 143.107.8.30 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:40:37 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I96 S. J. TAMBIAH

plant(whichbearsa snowywhiteflower) arecutandstrewn overthemandthe

tabugu thrust theirfacescloseandsayspells.

Thesymbolism oftheseobjects andoperations, aswellasthoseofthesubsequent

rituals, cannotbe understood without payingcloseattention to thewordsofthe

spell(seeI929: i8i). Theu'ula,thestemofthespell,refers tothebwaytuva, a bird

ofwhiteplumage(similar to thereefheron)whichis invited to hoveroverthe

bathing placeandtheprincipal locations ofwaterin thevillage.The whitebird

is themajorsymbol andthereisno doubtthatthepregnancy cloakstands forthe

bird'splumage.The tapwana, themainpartof thespell,showsthefollowing

patterni: thewhitebirdis saidto makeresplendent thedifferent partsoftherobe

(thetop, fringe, etc.) whichare namedin turn;nextthe birdmakesres-

plendent thevarious partsofthebodyofthepregnant womanfromheadtofoot

(head,nose,cheeks, chest, belly,groins, buttocks, thighs, knees,calvesandfeet).

The dogina, theconclusion ofthespell,states thatthepregnant womanhasbeen

whitened; a metaphorical equivalence isstated between theheadofthewomanand

thepallorbefore dawn,herfaceandthewhitesprouts ofthearecaplant(I929: I82).

It is clearthattherobe(whichmaterially represents thebird)anditscharming

havefortheirobjective thetransference of'whiteness' to thepregnant woman.

Thisis alsotheemphasis in theceremony at whicha womanis actually invested

bythetabugu withtherobeafter fivemonths ofpregnancy. Sheis carried intothe