Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

International Security and Development

Загружено:

Adán De la CruzАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

International Security and Development

Загружено:

Adán De la CruzАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

International Security and Development

Oxford Handbooks Online

International Security and Development

Necla Tschirgi

The Oxford Handbook of International Security

Edited by Alexandra Gheciu and William C. Wohlforth

Print Publication Date: Mar 2018 Subject: Political Science, International Relations

Online Publication Date: Apr 2018 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198777854.013.37

Abstract and Keywords

This chapter examines two interrelated questions: How do challenges in the development

arena contribute to global insecurity today? What types of research, policies, and

strategies can best contribute to alleviating, mitigating, and preventing these threats?

The chapter argues that after a lengthy period during the Cold War when development

and security were artificially separated, these twin agendas gradually started to come

closer in the 1990s under a new era of liberal internationalism. However, the re-

emergence of hard security threats after 9/11 have interrupted efforts toward greater

alignment between development and security Many of the challenges that currently

confront the international system have their roots in the development arena and require

concerted efforts by development and security analysts and actors. The chapter analyzes

the perfect storm of developmental factors that are building up to threaten international

security and examines possible avenues for greater cooperation between the two fields

for preventive action.

Keywords: development–security nexus, Sustainable Development Goals, UN Security Council, peacebuilding,

violence prevention, hard security, poverty, climate change, demographic pressures, Global War on Terror

38.1 Introduction

DRAWING upon the rich body of theory, policy, and practice since the end of the Cold

War, this chapter examines two interrelated questions: How do challenges in the

development arena contribute to global insecurity today? What types of research,

policies, and strategies can best contribute to alleviating, mitigating, and preventing

these threats? The chapter argues that after a lengthy period during the Cold War when

development and security theories, institutions, and policies were artificially separated,

these twin agendas gradually started to come closer in the 1990s under a new era of

liberal internationalism. However, the re-emergence of hard security concerns

threatening the Westphalian international order after 9/11 seriously affected efforts

Page 1 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

toward greater alignment between the development and security agendas. With the

Global War on Terror (GWOT) and the military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq,

governments reverted to traditional political and military instruments while development

actors were increasingly called upon to address the pressing humanitarian consequences

of new security threats as part of their development programming. With the ongoing civil

wars in the Middle East after the Arab Spring and the rise of ISIS, the recent Countering

Violent Extremism (CVE) agenda is heavily driven by hard security concerns—leading to

further divergence between security and development. This is unfortunate since many of

the challenges that currently confront the international system have their roots in the

development arena and require concerted efforts by development and security analysts

and actors.

The chapter is organized as follows: Section 38.2 provides a quick overview of the

growing recognition of the interplay between security and development in the aftermath

of the Cold War by researchers and policy-makers and draws out key insights that were

gained on the so-called security–development nexus. Section 38.3 reviews the (p. 563)

responses to the re-emergence of hard security threats following 9/11 and the unraveling

of the regional order in the Middle East after the occupation of Iraq. Section 38.4

analyzes key developmental drivers of contemporary threats to international security.

Finally, Section 38.5 offers some concluding thoughts as to why current fragmented

approaches to international security and development are inadequate to address some of

the key challenges that lie ahead and what might be done about them.

38.2 The Security–Development Nexus after the

End of the Cold War

Recognition of the interplay between security and development is not particularly novel.

Socio-economic factors have always been considered an important dimension of national

power and international security. Conversely, the impact of war and conflict on socio-

economic progress has been recognized long before the recent aphorism of conflict as

“development in reverse” (Collier 2003). Indeed, starting with the Truman Doctrine and

the Marshall Plan, the entire infrastructure of international development as we know it

today has its origins during the Cold War when the two superpowers exported their

economic models and sought to win friends among the newly-emerging states through

foreign aid. Yet, what distinguished the Cold War era was its singular focus on avoiding

war between the two nuclear superpowers and their allies. Security was thus pursued

primarily through increased military power and a web of alliances. Other lower-level

security threats (including underdevelopment, anti-colonial wars, intra-state conflicts,

and insurgencies) were important to the extent they affected the precarious balance of

power between the two rival blocs.

Thus, throughout the Cold War there was a marked divide between security studies,

institutions, and policies, on the one hand, and development studies, institutions, and

policies, on the other. The former focused on interstate wars and threats to the bipolar

Page 2 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

international order while the latter focused on the macro-economic development of the

so-called Third World countries. The lion’s share of foreign aid went to prop up friendly

governments and client states and to strengthen their military and security institutions

rather than to address deep-rooted developmental problems. With the end of the Cold

War, protracted local conflicts, intra-state wars, and complex political emergencies in

developing countries were catapulted to the international stage, although the major

powers did not consider these as direct threats to their vital interests. Thus, there was an

unusual opportunity to re-think the concept of security and examine ways of addressing

new types of threats with deep developmental roots.

The security studies literature of the 1990s reflects both a deepening and widening of the

concept of security, and growing contestation of the state-centric, post-Westphalian

security paradigm (Buzan and Hansen 2007). Given the changing international context,

traditional security institutions assumed new roles as reflected in the rapid expansion

(p. 564) of UN peacekeeping and NATO’s engagement in the Balkans. Development actors,

who until the end of the Cold War worked “in” or “around” conflict, finally started

working “on” conflict—an area that was considered the domain of political and security

actors (Goodhand 2006). This allowed many non-state actors (including the growing

number of international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)) to work on the complex

socio-economic-political drivers of conflict as well as on issues of conflict resolution,

peacemaking, and peacebuilding—tasks that had hitherto been considered outside their

mandate (Tschirgi 2004; Goodhand 2006).

It is in this context that the concepts of peacebuilding and the security–development

nexus emerged and led to a growing industry of academic literature as well as myriad

innovations aiming to bridge the chasm between the security and development

institutions, policies, and practices that had taken shape during the Cold War. Largely

informed by a “human security” lens and focusing primarily on addressing the twin

challenges of security and development in conflict-affected countries, the new interest in

the security–development nexus generated increased understanding of the range of

developmental factors that contribute to the onset, duration, and ending of violent

conflicts. There was exciting new research on the links between conflict and poverty,

horizontal inequality, displacement, poor governance, environmental and demographic

pressures, the resource curse, and other socio-economic factors. Recognizing the

developmental dimensions of these new security challenges, policy-makers and

practitioners responded with new peacebuilding programs such as rule of law, security

sector reform, and disarmament, demobilization, reintegration which would have been

unthinkable only a few decades earlier. The UN Security Council was called upon to play

an active role in peacemaking, peacekeeping, and peacebuilding after having been in

paralysis for much of the Cold War. There was growing convergence at the intersection of

an expanded development and peace and security agenda as reflected in successive UN

reports, An Agenda for Peace, An Agenda for Development, and An Agenda for

Democratization (United Nations 1992, 1994, 1997).

Page 3 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

Throughout the 1990s the main question that motivated research, policy, and practice

was how to avert the outbreak or recurrence of low-level security threats in developing

countries through structural prevention by addressing long-standing problems in the

development domain (Carnegie Commission 1997). The new conflict and peacebuilding

agendas at the United Nations, the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) and

the bilateral and multilateral donor agencies involved a serious examination of

development policies and strategies through a conflict lens—leading to new insights and

tools such as Do No Harm, conflict sensitivity, peacebuilding, and Peace and Conflict

Impact Assessment (Anderson 1999; OECD DAC 2001).

The conceptual, policy, and practical innovations of the 1990s were part of liberal

internationalism of the post-Cold War era and seemed to herald paradigmatic changes on

the part of key international actors. Security was no longer conceived primarily in

military and state-centric terms while the developmental challenges of developing

countries became an international concern. Yet, many of these efforts were in fact mostly

at the level of policy pronouncements and aspirational commitments. There were hardly

(p. 565) any fundamental reforms in either the development or security domains. A closer

look at international priorities, resource allocations, and institutional reforms of the

1990s confirm that the security–development nexus was more rhetorical than real

(Tschirgi et al. 2010; Amer et al. 2012). In retrospect, it is evident that there were serious

obstacles to greater synergy between development and security after decades of

disconnect. The two fields had differing guiding paradigms, institutional cultures, policy

priorities, and instruments as well as vastly different time frames for anticipated results.

It would have required an extension of the favorable international environment to bring

about fundamental shifts in both fields to better align them conceptually and

operationally. This was not to be.

38.3 The Paradox of 9/11: Securing or

Securitizing Development

The terrorist attacks of 9/11 had a direct and profound impact on the burgeoning concept

and practice of the security–development nexus (Dannreuther 2007; Baranyi 2008;

Hintjens and Zarkov 2015). 9/11 elevated problems originating in zones of conflict,

especially through terrorism and state failure, to the level of direct threats to

international security (Tschirgi 2013). The United States and its key allies declared

terrorism an existential threat requiring military action—opening the door to the US-led

Global War on Terror, the US interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as the

doctrines of counter insurgency and counter-terrorism. The forceful military responses to

9/11 transformed the international security context—ushering in a new era of foreign

wars by the United States and its key allies. They also reshaped the discourse on the

security-development nexus.

Page 4 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

Initially, there were high hopes for a “great bargain” after 9/11 whereby the international

community would prioritize both development and security as twin goals requiring

strategic attention, collective action, pooled resources and sustained collaboration by all

relevant actors. As was the case after the the Second World War and the Cold War, at the

United Nations and various international fora the links between deep-rooted development

problems and international peace and security were affirmed and calls for integrated

strategies reiterated (United Nations 2004; Annan 2005). Even as they fought open wars

in Afghanistan and Iraq, many Western governments committed to greater collaboration

between their departments of diplomacy, development, and defense (the “3Ds”) to

synchronize their efforts for “whole-of-government” approaches (OECD 2007; Patrick and

Brown 2007). However, the real consequence of 9/11 was not to deepen the links between

security and development but to “securitize” development by subordinating it to a

militarized security agenda (Baranyi 2008; Newman 2010; Tschirgi 2013). The conflict

prevention and peacebuilding agendas of the 1990s had been motivated by the need to

address deep-rooted development problems to bring greater stability and (p. 566) security

in conflict-affected countries and to avoid their regional and international spillovers. After

9/11 the security–development nexus was co-opted and re-conceptualized as the

cornerstone of a new stabilization and state-building strategy as a new hard security

agenda took shape (Baranyi 2008; Tschirgi 2013).

State failure was already on the international agenda in the 1990s with the breakdown of

political order in various Balkan and African countries. However, it gained prominence

after 9/11 with al-Qaeda’s success in flourishing in “ungoverned” spaces in Somalia,

Sudan, and Afghanistan. The 2002 US National Security Strategy set the tone when it

declared that “America is now threatened less by conquering states than we are by failing

ones” (United States 2002). In the following years, other countries and institutions

followed suit in identifying state failure, and its antidote state-building, as key challenges

due to increased security threats—especially terrorism—resulting from state fragility

(United Kingdom, 2008; United States 2008).

Thus, state-building emerged as a central priority at the nexus of security and

development. Yet, there was no consensus on what state-building required. Instead,

security and development actors approached the new state-building agenda from

different perspectives and with different agendas. Recognizing that effective statehood

required legitimacy as well as the capacity to govern, development actors took a longer-

term approach rooted in the concept of sustainable peace (OECD 2005; OECD DAC 1997,

2001; World Bank 2009, 2011; UNDP 2012). Meanwhile, defense departments and

national security agencies tended to view conflict and state fragility primarily as a

security issue—approaching state-building instrumentally from a stabilization

perspective. They focused largely on a state’s capacity to maintain security, ignoring the

fact that many instances of state failure witnessed in the 1990s were in fact the result of

the security-oriented strategies promoted by external actors during the Cold War. The

new stabilization and security agenda was less concerned with the domestic foundations

of good governance than with governments’ ability to crack down on terrorism and

transnational security threats. In many instances development and security actors found

Page 5 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

themselves working at cross-purposes. As the OECD (2007) noted regarding the

Principles of Good International Engagement in Fragile States & Situations that had been

adopted by donor governments:

The challenge for governments involved in fragile states is to establish clarity on

and coherence in objectives. These objectives are likely to differ among the

departments involved. … Therefore, ministries may promote national interests

rather than the interests of a partner country, which, from the perspective of

development cooperation, is problematic. When dealing with the problems of

precarious statehood— and in particular the wide range of potential threats

emanating from them—the issue therefore is how governments determine their

priorities for engagement in fragile states. From the perspective of the OECD-

DAC, the question more specifically is where development outcomes should rank

vis-à-vis trade, counter-terrorism, national defence and other political objectives of

donor countries. (OECD 2007: 17)

(p. 567)

Despite competing agendas, interest in the security–development nexus flourished in the

decade after 9/11—leading to a small industry of books, policy statements, reports, and

documents. There was, however, little agreement on how to bring them together (Duffield

2001; Stern and Öjendal 2010; Tschirgi et al. 2010; Mavrotas 2011). As Spear and

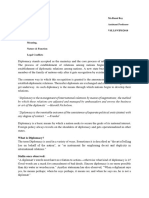

Williams (2012: 21) masterfully summarize—reproduced here in Table 38.1—there are at

least eight different ways in which the security–development relationship has been

conceptualized.

Different analysts and actors have taken entirely different approaches to explaining, as

well as responding to, the interplay between security and development, depending upon

their analytical perspectives, political agendas, institutional mandates, and the level at

which they work (Stern and Öjendal 2010; Spear and Williams 2012). Irrespective of their

differences, there is broad agreement that, unlike the dangerous clarity of the Cold War

or the heady optimism of the post-Cold War years, the second decade of the twenty-first

century is witnessing a shrinking world in constant turmoil; what happens in any part of

the world has almost instant repercussions globally. In such a context, the interplay

(p. 568) between security and development becomes even more complex. The two agendas

do not necessarily operate in synch—requiring continuous investigation of their interplay

at the domestic as well as the international level and crafting contextualized responses.

Table 38.1 Conceptualizing the security–development relationship

Zero-sum Security and development are framed in either–or terms where

allocating resources to one detracts from the potential to achieve the

other; e.g. the guns-versus-butter debate.

Page 6 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

Positive-sum Security and development are understood as mutually reinforcing;

the provision of one increases the likelihood of achieving the other.

Distinct Security and development are both viewed as important goals but

are understood as distinct enterprises best pursued using different

methods.

Synonymous Security and development are basically about the same thing:

ensuring that the referent object can pursue its cherished values

effectively.

Sequential Security and development are conceived as preconditions for the

other; e.g. development can only progress in a secure environment,

or genuine national security requires a certain level of economic

development.

Hierarchical Security priorities are said to structure the choice of development

projects undertaken. For some, this has produced a situation where

the development industry has become a project to support the peace

and stability of the North.

Selectively Security and development are interconnected but in complex and not

co- necessarily similar ways; e.g., only in certain contexts or with

constitutive respect to particular issues.

Sui generis Security and development issues are always entirely context

dependent; hence, it is impossible to draw meaningful conceptual

generalizations across different times and places.

Note: Table reproduced with permission from Joanna Spear and Paul D. Williams

(eds.), Security and Development in Global Politics: A Critical Comparison.

Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press 2012, p. 21.

38.4 The Security–Development Nexus in a

Turbulent World

There is increasing recognition that the contemporary scourge of terrorism and violent

extremism flourish in conditions of socio-economic deprivation and political exclusion

(United Nations 2006, 2015c). Similarly, analysts recognize that the Arab Spring and the

ongoing civil wars in Syria, Libya, and Yemen have been fueled by long-standing failures

of development in these countries (Al-Sumait et al. 2015; Sadiki, 2015). Meanwhile, the

UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have explicitly made the case for the

Page 7 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

interplay between developmental factors and security (United Nations 2015b). In other

words, there is strong evidence that neither approaching security and development as

separate areas of concern nor securitizing development has yielded positive results. The

challenge is in viewing developmental risks through a long-term, security and conflict-

prevention lens. That requires taking development seriously and committing the

necessary tools and resources to addressing structural development problems before they

become imminent security threats.

Based on a review of the extensive body of literature generated since the end of the Cold

War, Section 38.4.1 aims to illustrate what we have learned about how developmental

factors affect international security. Development is an all-encompassing concept,

evolving from its early equation with macro-economic growth to its expanded definition

embracing economic, social, political, and environmental dimensions of well-being. As a

result, the discussion in Section 38.4.1 is highly selective—focusing on several long-term

development trends that are steadily converging to threaten international security.

38.4.1 A Perfect Storm: Convergence of Demography, Poverty,

Inequality, and Environmental Degradation

In the words of former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, poverty, inequality,

demographic, and environmental pressures are “problems without passports” (Annan

2009). They are not only transnational in nature; they take place in a context of

heightened globalization whereby their scope and impacts are greatly magnified. The

security implications of each of these development problems have been investigated

extensively by experts. While these problems do not necessarily cause direct or

immediate security threats, they do pose particular risk factors which, combined with

other factors, can (p. 569) help to create a perfect storm. For example, several

demographic trends that have been developing over time (namely, the divergent age

structure of populations in developing and industrialized countries; the youth bulge in

developing countries; the mass movement of populations through urbanization,

migration, and refugee flows) seem to have reached a dangerous point today. The

statistics are telling.

It is projected that the global population of 7.3 billion in 2015 will continue to grow—

reaching 9.7 billion people by 2050 (United Nations 2015a). The growth will be

concentrated in only a few regions and countries—many of which are not only among the

world’s lowest income countries, but are also in regions of conflict in Africa and the

Islamic world (Goldstone 2012). Meanwhile, population growth will be slow, or negative,

in many industrialized countries. It is projected that by 2050, the population of the

developed countries will stagnate while the population of the rest of the world will grow

by 50 percent—from 5.3 billion people in 2005 to 8 billion in 2050 (Goldstone 2012).

Perhaps the most pressing issue is the so-called youth bulge. In countries where the

proportion of the population aged 15 or younger ranges from 30 to 40 percent, the

pressure for education, health, basic services, and jobs will increase in the coming

decades—creating heavy burdens on governments. Concurrent with the population

Page 8 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

increase and the youth bulge, massive migration from the countryside to cities is

expected to continue. For less-developed regions, the urban population is projected to

increase from 42.7 percent in 2005 to 67 percent by 2050 (Goldstone 2012; United

Nations 2015a), leading to competition for scarce resources in urban settings. Equally

importantly, migration and refugee flows from developing to developed countries are

expected to accelerate due to civil wars, domestic conflicts, natural disasters, and

economic pressures.

These demographic trends and the growing population discrepancies across the North–

South axis are sufficiently alarming. Yet, they are also accompanied by an equally

dramatic change in global incomes. It is expected that the share of income going to

developed countries with the richest billion people in the world is likely to fall from

roughly 60 percent in 2005 to less than 30 percent by 2050 (Goldstone 2012). This,

however, does not mean that the great divide in wealth between the global North and the

South—the haves and the have-nots—will disappear. On the contrary, as the 2017 Oxfam

briefing paper, An Economy for the 99%, argues, “the global inequality crisis continues

unabated.” According to Oxfam (2017), eight men now own the same amount of wealth as

the poorest half of the world. In 2010, that number was 388 individuals. “Since 2015, the

richest 1% has owned more wealth than the rest of the planet,” the report finds and “the

incomes of the poorest 10% of people increased by less than $3 a year between 1988 and

2011, while the incomes of the richest 1% increased 182 times as much.” Strikingly,

“Since 2015, the richest 1% has owned more wealth than the rest of the planet.”

The consequences of global inequality are manifold—undermining growth, perpetuating

poverty, fragility, and conflict. Researchers have shown that a country’s rate of growth is

inversely correlated with the risk of conflict (Collier 2001, 2008; Fukuda-Parr 2010). It is

estimated that the risk of war is three times greater for a country with a per capita

income of $1,000 than for a country with a per capita income of $4,000 (Humphreys

2003; Fukuda-Parr 2010). The countries at the bottom of the Human Development Index

are also the countries that face state fragility or conflict (World Bank 2011). (p. 570)

Nonetheless, researchers do not posit a direct causal link between poverty and

international insecurity. Instead, the links are intermediated through such factors as

horizontal inequalities, poor governance, urban pressures, heightened competition for

scarce resources, high unemployment, globalization, technological connectivity, greater

access by young men to criminal and terrorist networks, conflict, and state failure.

During most of the Cold War “mainstream security studies relegated poverty to the

category of low politics” (Williams 2012: 193). This is no longer the case as the complex

interplay between poverty, inequality, population growth, urbanization, and globalization

have become increasingly more evident. In a rapidly globalizing and interdependent

world, the persistence of an unequal world order that fails to address interlocking global

problems is a contributing factor to insecurity and conflict. These problems have been

exacerbated by environmental degradation which has emerged as a multi-faceted threat

(Dannreuther 2007; Matthew 2010).

Page 9 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

Until the end of the Cold War, “the notion of the environment as a significant source of

insecurity was not on the radar screen” (Dannreuther 2007). This has changed radically

even though researchers and analysts continue to differ on the nature and dynamics of

the interplay between the environment and security. Some scholars refer to an

“environmental crisis” whereby unrestrained human activity, intensified by a growing

population, is destroying the carrying capacity of the earth. They foresee heightened

competition over natural resources with grave consequences for security. There is a rich

body of literature on the links between natural resources and civil conflict—variably

explained in terms of resource scarcity or the resource curse. Others point to climate

change as a growing threat in light of mounting evidence of its adverse impacts on the

world economy, affecting economic growth in both the industrial and developing

countries. Climate change is also expected to lead to extreme weather conditions and a

significant loss of productive agricultural lands—fueling poverty as well as mass

migration (United Nations 2016). As with other developmental factors, environmental

problems have a direct impact on the poor and the vulnerable; they also have a North–

South equity dimension which adds to their complexity. It is generally accepted that the

relationship between security and the environment is indirect and multi-directional.

Researchers have identified various feedback loops through which environmental factors

generate conflicts and security threats and vice versa (Homer-Dixon 1999; Dannreuter

2007; Matthew 2010). It is, however, quite evident that mounting environmental problems

can no longer be ignored as a security issue—especially when coupled with changing

demographic and economic factors.

38.4.2 The Challenges of Governance in an Insecure World

The interlocking dynamics between the long-term trends identified in Section 8.4.1

demonstrate the gravity of the potential threats they pose to human security, political

stability, state failure and, indirectly, to international security. None of these problems

(p. 571) lend themselves to quick and easy solutions. Moreover, although anchored in

concrete contexts, they traverse the globe. From a prevention perspective, the challenge

is how best to manage their progression and mitigate their negative impacts through

more effective governance in a world where nation states and fragmented approaches

still dominate. Indeed, this is where security studies and developmental studies have a

common agenda: greater understanding of the challenges of governance both at the

domestic and international levels.

Development studies has—albeit belatedly—recognized the importance of good

governance as an essential element of socio-economic development. Security studies, on

the other hand, has traditionally taken a narrow view of the institutional underpinnings of

security—focusing primarily on the security institutions of the state. With development

trends posing long-term security challenges, there is need for a conceptualization of

governance beyond the security oriented state-building model discussed in this chapter.

Page 10 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

At the domestic level, governance is not about stronger states but about how power is

exercised to manage public affairs; it is increasingly understood in terms of state–society

relations based on legitimate and accountable institutions, norms, and processes within

an inclusive political framework. State-centric security approaches that are not based on

a social contract between the government and its citizenry are unlikely to provide either

development or security—as repeatedly demonstrated in weak, fragile, and failing states.

Good governance (variably defined as democratic participation, inclusive politics, or state

legitimacy) has to do with more than building state institutions and capacities. It is

correlated with citizens’ perceptions of their ability to shape the decisions that affect

their lives (World Bank 2011; UNDP 2012). In that light, governance deficits are not

exclusively confined to fragile or conflict-affected states. There is a serious crisis of

governance in many countries around the world. Economic and financial crises,

terrorism, unrestrained migration, and the negative impacts of globalization are creating

deep distrust in politics and established governance systems with serious implications for

their ability to ensure security. Perhaps one of the most telling examples of the crisis of

governance was the discordant responses of European governments to the 2015 Syrian

refugee crisis and the rise of populist, right-wing political movements contesting official

policies.

At the international level, the governance challenges are of a different order. There is

growing recognition that there have been fundamental changes in the world system

without corresponding changes in global governance. From the bipolar world of the Cold

War, to the unipolar world of the 1990s, we are living in an era of tectonic shifts in

economic and political power. As has been noted: “We have not any time since 1800 seen

a world in which the majority of economic growth occurs outside of the United States and

Europe, in which any countries had sixty-year-olds constitute 30–40% of their

populations, and in which large countries at relatively modest levels of income per capita

reached urbanization levels of 60%. Yet that is the world of the next half

century” (Goldstone 2012: 288–9). The impacts of these trends are compounded by

traditional as well as non-traditional security threats including violent extremism,

terrorism, (p. 572) cybersecurity, and organized crime. Largely created in the aftermath of

the Second World War, current global institutions are unable to deal with the number and

complexity of these challenges. Equally importantly, they do not represent the important

shifts of power in the international system ranging from the rise of China and India to the

growing role of non-state actors. Clearly, there is a pressing need for more representative

and effective institutions of governance at the international level that can deal with global

problems. Yet, paradoxically, even as the need for global governance grows, there is

public suspicion and lack of faith in multilateralism and the post-Second World War

international architecture as prominently reflected in the election of Donald Trump as US

President in November 2016. From both a security and development perspective,

addressing the deficits of governance emerges as a high priority.

Page 11 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

38.5 Implications and Possible Directions

What are the implications of the preceding analysis for future research and policy? It is

clear that security studies and development studies cannot continue on separate tracks as

they have done for much of the last 60 years. This chapter has shied away from claiming

any automatic causal connection between development and international security. Indeed,

both fields need to continue deepening their understanding of development and security

as distinct issue areas. Nonetheless, there is also need for multi-disciplinary research

focusing on issues at the intersection of international security and development. There is

already a rich body of literature on specific aspects of the nexus—poverty and civil

conflict, urbanization and criminal violence, terrorism and marginalization, climate

change and environmental migration. What is missing is a concerted and long-term

research agenda that brings researchers from both fields to apply the qualitative and

quantitative tools of their disciplines to map out and investigate the complex interplay of

development and security challenges that face us in the twenty-first century. Such a

research program requires a prevention mindset which goes beyond the “clear and

present danger” perspective of many security analysts without securitizing development.

The development challenges described above are long-term threats; nonetheless, in

combination they can cause a “perfect storm.” We need to understand the conditions that

can create such a perfect storm using both development and security frameworks and

tools while exploring new governance mechanisms to manage local, national, and global

challenges.

Yet, focusing only on structural factors or material conditions will not suffice. Guided by

insights from traditional security studies, threat perceptions by both policy-makers and

publics in a world in turmoil should be part of any research at the nexus of security and

development. Public perceptions of loss of national sovereignty, community, or identity

should be taken into account alongside deteriorating socio-economic (p. 573) conditions or

hard security threats. Rise of right-wing leaders and populist resistance to immigration

and refugee flows as security threats in the US and Europe demonstrates the challenges

policy-makers face in reconciling domestic pressures with the need for multilateral action

in a dangerous world. Thus, multi-disciplinary research needs to include disciplines that

can bring an understanding of both the objective conditions and subjective perceptions of

insecurity in a shrinking world.

Turning to policy implications, as the preceding analysis demonstrates, threats emanating

from the development arena are not sectoral in nature and do not lend themselves to

fragmented solutions. They are products of long-term historical and socio-economic

trends, exacerbated by far-reaching changes in the international system due to

globalization, technological advances, the end of the Cold War, and the rise of

transnational threats like global terrorism. Thus, policy responses should be informed by

historically grounded and contextually specific analysis. While useful, simply adding

band-aid solutions like security sector reform to the development toolbox is not enough.

Similarly, strategies of containment or stabilization promoted by security actors are not

viable over the long-haul. Meanwhile, including Goal 16 to “promote peaceful and

Page 12 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build

effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels” as part of the Sustainable

Development Goals is far from adequate (United Nations 2015c). Going beyond Goal 16,

there is need for a fundamental re-thinking of all the sustainable development goals from

a peace and security perspective.

However, a more coherent or comprehensive policy framework is not sufficient without

corresponding resources. According to the US Department of State (United States 2015)

which tracks military expenditures and arms transfers globally: “From 2002 through

2012, in constant 2012 U.S. dollar terms, the annual value of world military expenditures

appears—despite declining slightly after 2009—to have risen about 40–52%, from about

$1.28–.59 trillion in 2002 to about $1.79–2.42 trillion in 2012, and to have averaged

between $1.59 and $2.04 trillion for the 11-year period.” During this same 11-year

period, “the share of GDP to which military expenditure was equivalent—an indicator

sometimes called ‘the military burden’—appears to have averaged between 2.1% and

2.5%, peaking at between 2.2% and 2.8% in 2009” (United States 2015). According to

SIPRI, in 2015 global military expenditure was $1.67 trillion, equivalent to 2.3 per cent of

global gross domestic product (SIPRI, 2016). Meanwhile, in 2015 official development

assistance (ODA) by the 28 countries in the OECD Development Assistance Committee

(2015) stood at $131.6 billion, averaging 0.30% of gross national income.

The allocation of resources outlined in the previous paragraph is indicative of the

continuing gap between security and development priorities. It also reflects the

challenges of mobilizing resources for preventive purposes in a global system based on

sovereign states. Despite various waves of internal reforms, the United Nations is

straining to address the growing range of issues on its agenda. Moreover, it is highly

compartmentalized with different parts of the system dealing with climate change,

population, poverty, and security. The relations between the UN Security Council and

ECOSOC—the (p. 574) UN’s Economic and Social Council responsible for development—

remain shaky. The UN’s relations with the Bretton Woods Institutions have traditionally

been constrained due to member state policies and preferences even though there is

growing collaboration at least on the development front. The World Bank’s publication of

the 2011 World Development Report, Conflict, Development and Security, was a

breakthrough. However, the global system remains as siloed as ever. Beyond the UN,

there are no global institutions with the mandate to address security and development

challenges in a coherent manner.

The imperative for conflict prevention and peacebuilding, as a joint agenda for security

and development analysts and actors, rests on the viability of the idea of global

interdependence and global governance. There are numerous institutional, political, and

procedural obstacles to the realization of this agenda. However, perhaps the most serious

is the increasing push-back against globalization and the idea of a liberal one-world

system that seemed on the ascendancy in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War. This

push-back manifests itself in different ways in different parts of the world (Barber 1995;

Page 13 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

Ikenberry 2011; Haidt 2016). It is found in the ideology of political Islam which, in its

extreme form, has led to the scourge of global terrorism.

However, there are other forces at work which were further accelerated with

globalization that also challenge the post-Second World War liberal international world

order. The economic rise of China, the resurgence of a nationalist Russia, the British vote

to exit the European Union, President Trump’s America First policies in the United

States, and populist, isolationist movements in Europe seem to signify a return to a more

fragmented, inward-looking worldview across the globe. Thus, it is particularly ironic that

while the range of threats and challenges discussed in this chapter require greater global

collaboration for effective preventive action, we might in fact witness the strengthening

of the Westphalian state system based on traditional concepts of nationalism and national

security in an increasingly globalized world.

References

Al-Sumait, F. N. Lenze, and M. C. Hudson, M.C. (eds.). 2015. The Arab Uprisings:

Catalysts, Dynamics, and Trajectories. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Amer, R. A. Swain, and J. Öjendal. 2012. The Security–Development Nexus: Peace,

Conflict and Development. London: Anthem Press.

Annan, K. 2005. In Larger Freedom: Towards Security, Development and Human Rights

for All. New York; United Nations.

Annan, K. 2009. Problems without Passports. Foreign Policy, Special Report.

Anderson, M. 1999. Do No Harm. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Baranyi, S. 2008. The Paradoxes of Peacebuilding Post-9/11. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Barber, B. 1995. Jihad vs. McWorld: How Globalism and Tribalism Are Reshaping the

World. London: Ties Books, Random House.

Buzan, B. and L. Hansen. 2007. Debating Security and Strategy and the Impact of 9-11.

Reader on International Security. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications especially Vol 4.

Buzan, B., O. Wæver, and J. de Wilde, J. 1998. Security: A New Framework for

(p. 575)

Analysis. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Carnegie Commission. 1997. Preventing Deadly Conflict. New York: Carnegie

Commission.

Collier, P. 2001. Economic Causes of Civil Conflict and Their Implications for Policy. In C.

Crocker, F. Hampson, and P. Aall (eds.), Turbulent Peace: The Challenges of Managing

International Conflict, pp. 143–61. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace.

Page 14 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

Collier, P. 2003. Breaking the Conflict Trap: Civil War and Development Policy.

Washington, DC: World Bank.

Collier, P. 2007. The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can

Be Done About It. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dannreuther, R. 2007. International Security: The Contemporary Agenda. Cambridge:

Polity Press.

Duffield, M. 2001. Global Governance and the New Wars: The Merging of Development

and Security. London: Zed Books.

Fukuda-Parr, S. 2010. Poverty and Violent Conflict: Rethinking Development. In N.

Tschirgi, M. Lund, and F. Mancini (eds.), Security and Development: Searching for Critical

Connections. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Goldstone, A. 2012. Demography: A Security Perspective. In J. Spear, and P. Williams

(eds.), Security and Development in Global Politics: A Critical Comparison. Washington,

DC: Georgetown University Press.

Goodhand, J. 2006. Aiding Peace? The Role of NGOs in Armed Conflict. Boulder, CO:

Lynne Rienner.

Haidt, J. 2016. When and Why Nationalism Beats Globalism. The National Interest. 12(1).

Hintjens, H. and D. Zarkov. 2015. Conflict, Peace, Security and Development: Theories

and Methodologies. Abingdon: Routledge.

Homer-Dixon, T. 1999. Environment, Scarcity and Violence. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press.

Humphreys, M. 2003. Economics and Violent Conflict. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Ikenberry, John G. 2011. Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the

American World Order. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Matthew, A. 2010. Environment, Conflict, and Sustainable Development. In N. Tschirgi,

M. Lund, and F. Mancini (eds.), Security and Development: Searching for Critical

Connections. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Mavrotas, G. (ed.). 2011. Security and Development. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar

Publishers.

Newman, E. 2010. Peacebuilding as Security in “Failing” and Conflict-Prone States.

Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 4: 305–22.

OECD. 2005. Principles for Good International Engagement in Fragile States. OECD

document DCD, 11/REV.2.

Page 15 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

OECD. 2007. Whole of Government Approaches in Fragile States. Available at:

www.oecd.dac/dataoecd/15/24/37826256pdf, accessed December 8, 2016.

OECD. 2008. 3rd High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness, 2–4 September, Accra, Ghana,

Roundtable Summary. Paris: OECD.

OECD DAC. 1997. DAC Guidelines on Conflict, Peace and Development Co-operation.

Paris: OECD.

OECD DAC. 2001. DAC Guidelines: Helping Prevent Violent Conflict. Available at: http://

www.gtz.de/security-sector/download/DAC_Guidelines.pdf, accessed December 8,

2016.

OECD DAC. 2015. Development aid rises again in 2015, spending on refugees

(p. 576)

doubles. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/dac/development-aid-rises-again-

in-2015-spending-onrefugees-doubles.htm, accessed December 8, 2016.

Oxfam. 2017. An Economy for the 99%. Available at: https://www.oxfam.org/en/

research/economy-99, accessed on May 15, 2017.

Patrick, S. and K. Brown. 2007. Greater than the Sum of Its Parts? Assessing “Whole of

Government Approaches” to Fragile States.Washington, DC: Center for Global

Development.

Sadiki, L. 2015. Routledge Handbook of the Arab Spring: Rethinking Democratization,

London: Routledge.

SIPRI. 2016. Yearbook 2016, Armaments, Disarmament and International Security.

Available at: https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/YB16-Summary-ENG.pdf,

accessed December 8, 2016.

Spear, J. and P. Williams (eds.). (2012). Security and Development in Global Politics: A

Critical Comparison. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Stern, M. and J. Öjendal. 2010. Mapping the Security–Development Nexus: Conflict,

Complexity, Cacophony, Convergence? Security Dialogue, 41(1); 5–31.

Stern, M. and J. Öjendal. 2012. Exploring the Security-Development Nexus. In A. Swain,

and J. Öjendal, The Security–Development Nexus: Peace, Conflict and Development.

London: Anthem Press.

Tschirgi, N. 2004. Post-Conflict Peacebuilding Revisited: Achievements, Limitations,

Challenges. International Peace Academy, IPA Policy Paper.

Tschirgi, N. 2013. Securitization and Peacebuilding. In Roger Mac Ginty (ed.), Routledge

Handbook of Peacebuilding. London: Routledge.

Tschirgi, N., M. Lund, and F. Mancini (eds.). 2010 Security and Development: Searching

for Critical Connections, Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Page 16 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

United Kingdom. 2008. National Security Strategy. Norwich: Her Majesty’s Stationery

Office.

United Nations. 1992. An Agenda for Peace: Preventive Diplomacy, Peacemaking and

Peacekeeping. Report of the Secretary-General pursuant to the statement adopted at the

Summit Meeting of the security Council on January 31, 1992. UN Doc A/47/277-S/2411

United Nations. 1994. An Agenda for Development: Report of the Secretary-General. UN

Doc A/48/935.

United Nations. 1997. An Agenda for Democratization, Report of the Secretary-General.

UN Doc S/1997/712.

United Nations. 2004. A More Secure World: Our Shared Responsibility. Report of the

High Level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change. New York: United Nations.

United Nations. 2006. The United Nations Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy. UN Doc A/

Res?60/288.

United Nations. 2015a. World Population Prospects, 2015 Revisions. Available at: https://

esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/publications/files/key_findings_wpp_2015.pdf, accessed on

December 8, 2016.

United Nations. 2015b. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable

Development. UN Doc A/69/L.85.

United Nations. 2015c. Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism. UN Doc A/70/674.

United Nations. 2016. Framework Convention on Climate Change. Available at: http://

unfccc.int/paris_agreement/items/9485.php, accessed December 8, 2016.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) 2012. Governance for Peace: Securing

the Social Contract. Available at: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/

librarypage/ (p. 577) crisis-prevention-and-recovery/

governance_for_peacesecuringthesocialcontract.html, accessed September 12, 2017.

United States. 2002. The National Security Strategy of the United States of America.

Available at: http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/63562.pdf, accessed

December 9, 2016.

United States. 2008. National Defense Strategy. Washington, DC: Department of Defense.

United States. 2015. World Military Expenditures and Arms Transfers. Available at:

http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/251075.pdf, accessed on December 8,

2016.

Williams, Paul D. 2012. Poverty: A Security Perspective. In J. Spear and P. Williams (eds.),

Security and Development in Global Politics: A Critical Comparison. Washington, DC:

Georgetown University Press.

Page 17 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

International Security and Development

World Bank. 2004. The Role of the World Bank in Conflict and Development: An Evolving

Agenda. Washington, DC: World Bank: Conflict Prevention and Reconstruction Unit.

World Bank. 2009. Securing Development by World Bank President Robert B. Zoellick, a

presentation at USIP. Available at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/NEWS/

Resources/RBZUSIPSpeech010809.pdf, accessed September 12, 2017.

World Bank. 2011. World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security and Development.

Washington, DC: World Bank.

Necla Tschirgi

Necla Tschirgi is Professor of Practice, Human Security and Peacebuilding at the

Joan B. Kroc School of Peace Studies, the University of San Diego.

Page 18 of 18

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com). © Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: CENTRO DE INVESTIGACION Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C.; date: 18 February 2019

Вам также может понравиться

- Introduction To Security StudiesДокумент334 страницыIntroduction To Security StudiesPaulina Anguiano Díaz de la VegaОценок пока нет

- Tir MarxismДокумент4 страницыTir MarxismVarja DiОценок пока нет

- Developing A Human Security Index For The PhilippinesДокумент218 страницDeveloping A Human Security Index For The PhilippinesUP Third World Studies Center100% (2)

- Economic Diplomacy and StatecraftДокумент10 страницEconomic Diplomacy and StatecraftMd Ashfaq HussainОценок пока нет

- Heywood Global Politics Chapter 01-21 SlidesДокумент136 страницHeywood Global Politics Chapter 01-21 SlidesBo100% (3)

- Dynamics of Expanding Concepts of International SecurityДокумент5 страницDynamics of Expanding Concepts of International SecurityHumaОценок пока нет

- Defence DiplomacyДокумент3 страницыDefence DiplomacyAchmad Reza PutraОценок пока нет

- Concepts of Comprehensive SecurityДокумент8 страницConcepts of Comprehensive SecurityferОценок пока нет

- Strategies for Peace: Contributions of International Organizations, States, and Non-State ActorsОт EverandStrategies for Peace: Contributions of International Organizations, States, and Non-State ActorsОценок пока нет

- Major Theories of International RelationsДокумент36 страницMajor Theories of International RelationsPaula Bianca Cedillo CorsigaОценок пока нет

- RealismДокумент4 страницыRealismloserkid520Оценок пока нет

- Neorealism Addresses The Limitations of Classical RealismДокумент3 страницыNeorealism Addresses The Limitations of Classical RealismSaed KakeiОценок пока нет

- Understanding The 2003 United States-Iraq Invasion: A Study of Level AnalysisДокумент17 страницUnderstanding The 2003 United States-Iraq Invasion: A Study of Level AnalysisNofia Fitri Azriel67% (3)

- Term 1, Week 2: PLEASE NOTE This Is A 2013 Reading List-The Precise Content May Change in Future YearsДокумент5 страницTerm 1, Week 2: PLEASE NOTE This Is A 2013 Reading List-The Precise Content May Change in Future YearsNur Ulfa Alifah100% (1)

- International Relations TheoryДокумент20 страницInternational Relations Theoryvonne6550% (2)

- Essentials of International Relations Chapter SummaryДокумент65 страницEssentials of International Relations Chapter SummaryMukhtiar AliОценок пока нет

- Approaches of International RelationsДокумент10 страницApproaches of International RelationsHash SinghОценок пока нет

- CMR Theories on Civilian Control of Armed ForcesДокумент33 страницыCMR Theories on Civilian Control of Armed ForcesMohd AzrinОценок пока нет

- Approaches To International SecurityДокумент66 страницApproaches To International SecurityCEBRI - Brazilian Center for International Relations100% (1)

- Regional Security Complex Theory ExplainedДокумент37 страницRegional Security Complex Theory ExplainedRhisma Eka Ranata100% (1)

- Why Realist Theory Remains Relevant After the Cold WarДокумент4 страницыWhy Realist Theory Remains Relevant After the Cold WarElaineMarçalОценок пока нет

- Collective Security SystemДокумент18 страницCollective Security SystemPrashant MeenaОценок пока нет

- The Security Dilemma in Alliance PoliticsДокумент11 страницThe Security Dilemma in Alliance PoliticsGagu LaurОценок пока нет

- Thinking Beyond Politics PDFДокумент234 страницыThinking Beyond Politics PDFAminodin SaripОценок пока нет

- International Politics Meaning Nature and ScopeДокумент12 страницInternational Politics Meaning Nature and ScopeMohammed Arif KhanОценок пока нет

- Violent Non State ActorsДокумент21 страницаViolent Non State Actorsp.haspra3760Оценок пока нет

- Six Principles of Political RealismДокумент2 страницыSix Principles of Political RealismGuilherme Cruz86% (7)

- International RelationsДокумент18 страницInternational RelationsahtishamОценок пока нет

- Meaning, Nature & Function of DiplomacyДокумент15 страницMeaning, Nature & Function of DiplomacySatyam PathakОценок пока нет

- MTD PDFДокумент5 страницMTD PDFfinesukmaОценок пока нет

- On Security: Chapter 3 explores securitization and desecuritizationДокумент31 страницаOn Security: Chapter 3 explores securitization and desecuritizationDiana Jessica Ramos LopezОценок пока нет

- Traditional Vs New DiplomacyДокумент19 страницTraditional Vs New DiplomacyFazzillah Noordin29% (7)

- Global Security - International SecurityДокумент9 страницGlobal Security - International SecuritySpin WatchОценок пока нет

- Thayer Regional Security and Defence DiplomacyДокумент16 страницThayer Regional Security and Defence DiplomacyCarlyle Alan Thayer100% (1)

- Foreign Policy AnalysisДокумент5 страницForeign Policy AnalysisPatricia Guerra100% (1)

- What is Diplomacy? Political Science EssayДокумент4 страницыWhat is Diplomacy? Political Science EssayapperdapperОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 Andrew Heywood GlobalizationДокумент25 страницChapter 1 Andrew Heywood GlobalizationTanay shah100% (1)

- ROTBERG - Robert I.the New Nature of Nation-State FailureДокумент12 страницROTBERG - Robert I.the New Nature of Nation-State FailureCamilla RcОценок пока нет

- Geopolitics: To Cite This Article: Virginie Mamadouh & Gertjan Dijkink (2006) : Geopolitics, International RelationsДокумент19 страницGeopolitics: To Cite This Article: Virginie Mamadouh & Gertjan Dijkink (2006) : Geopolitics, International RelationsmarianneОценок пока нет

- Actors Arnold WolfersДокумент16 страницActors Arnold Wolferssashikumar1984Оценок пока нет

- Securitization Theory and Securitization StudiesДокумент9 страницSecuritization Theory and Securitization Studiesanumania100% (1)

- 1 An Introduction To International RelationДокумент12 страниц1 An Introduction To International RelationShaksham ShahiОценок пока нет

- Curs 5 Diplomatic Consular Law Establishing, Breaking and Suspension of Diplomatic RelationsДокумент13 страницCurs 5 Diplomatic Consular Law Establishing, Breaking and Suspension of Diplomatic RelationsLucian-Andrei DespaОценок пока нет

- Penguin Dictionary - IR, International Politcs, World PoliticsДокумент3 страницыPenguin Dictionary - IR, International Politcs, World PoliticsBartłomiej OrłowiczОценок пока нет

- Outline International Relations TheoryДокумент34 страницыOutline International Relations TheorySarah Saeed75% (4)

- InternationalRelations (The First Great Debate)Документ14 страницInternationalRelations (The First Great Debate)Anonymous 03oWuP4xОценок пока нет

- International Relations and Diplomacy (ISSN2328-2134) Volume 7, Number 11,2019Документ55 страницInternational Relations and Diplomacy (ISSN2328-2134) Volume 7, Number 11,2019International Relations and Diplomacy100% (1)

- Globalization: The Paradox of Organizational Behavior: Terrorism, Foreign Policy, and GovernanceОт EverandGlobalization: The Paradox of Organizational Behavior: Terrorism, Foreign Policy, and GovernanceОценок пока нет

- Nuclear Deterrence and Hybrid WarfareДокумент25 страницNuclear Deterrence and Hybrid WarfareFaizan JunejoОценок пока нет

- Wolfers 1952, 'National Security' As An AmbiguДокумент23 страницыWolfers 1952, 'National Security' As An AmbiguMarcОценок пока нет

- Duterte Appeasement Policy PDFДокумент24 страницыDuterte Appeasement Policy PDFErielle SibayanОценок пока нет

- Summary On Neo-Neo DebateДокумент4 страницыSummary On Neo-Neo Debatehoneymione100% (1)

- International RelationsДокумент58 страницInternational Relationsrenoirscribd100% (1)

- Girotra Vinay Civil-Military RelationsДокумент11 страницGirotra Vinay Civil-Military Relationsvkgirotra100% (5)

- PS2237 Theory SummariesДокумент41 страницаPS2237 Theory SummariesLiew Yu KunОценок пока нет

- Changing Conceptions of Security in The 21st CenturyДокумент12 страницChanging Conceptions of Security in The 21st CenturyAdnan Rafique100% (1)

- AIR742 Week 6 ConstructivismДокумент25 страницAIR742 Week 6 ConstructivismHaiderrehmanОценок пока нет

- The Role of States in Global Citizen Diplomacy RoundtableДокумент30 страницThe Role of States in Global Citizen Diplomacy RoundtableCenterForCitizenDiplomacy100% (2)

- Rothschild What Is SecurityДокумент47 страницRothschild What Is Securityintlconflict100% (2)

- Dalby 2014 Climate Security G PolДокумент9 страницDalby 2014 Climate Security G PolAdán De la CruzОценок пока нет

- Environmental Security Article Nordas Gleditsch PDFДокумент14 страницEnvironmental Security Article Nordas Gleditsch PDFAdán De la CruzОценок пока нет

- Role of G20 in The Global Financial ArchitectureДокумент17 страницRole of G20 in The Global Financial ArchitectureAdán De la CruzОценок пока нет

- National Integration in PakistanДокумент8 страницNational Integration in PakistanMuhammadMansoorGohar100% (2)

- Contemporary Global Governance Indicators and Challenges to the Nation-StateДокумент4 страницыContemporary Global Governance Indicators and Challenges to the Nation-StateTan AdonnisОценок пока нет

- 2.good GovernanceДокумент10 страниц2.good Governancedawoodabdullah56Оценок пока нет

- Africa Risk-Reward IndexДокумент22 страницыAfrica Risk-Reward Indexcardona acuñaОценок пока нет

- The Concepts of State Building, Nation Building and Society BuildingДокумент13 страницThe Concepts of State Building, Nation Building and Society BuildingLani CardenioОценок пока нет

- Authorized Crime in Mexico PDFДокумент12 страницAuthorized Crime in Mexico PDFveckstОценок пока нет

- Van Schendelen. (1989) - Consociational Democracy The Views of Lijphart and Collected CritismДокумент41 страницаVan Schendelen. (1989) - Consociational Democracy The Views of Lijphart and Collected CritismBoОценок пока нет

- Between Development and Destruction An Enquiry Into The Causes of Conflict in Post-Colonial States by Luc Van de Goor, Kumar Rupesinghe, Paul Sciarone (Eds.)Документ385 страницBetween Development and Destruction An Enquiry Into The Causes of Conflict in Post-Colonial States by Luc Van de Goor, Kumar Rupesinghe, Paul Sciarone (Eds.)Dylan HerreraОценок пока нет

- Crisis of Good Governance in PakistanДокумент2 страницыCrisis of Good Governance in Pakistanahsanmansoor78% (9)

- Medellín Laboratory - An Exhibit of Ten Ongoing PracticesДокумент224 страницыMedellín Laboratory - An Exhibit of Ten Ongoing PracticesAci Medellín100% (1)

- Buzan B. (2018) - Great PowersДокумент16 страницBuzan B. (2018) - Great PowersRadek RadОценок пока нет

- GOOD GOVERNANCE BOOSTS ECONOMIC GROWTHДокумент19 страницGOOD GOVERNANCE BOOSTS ECONOMIC GROWTHPritam AnantaОценок пока нет

- Hybrid Governance As A Dynamic Hub For VДокумент21 страницаHybrid Governance As A Dynamic Hub For VANDREA FERNANDA SEGOVIA MARINОценок пока нет

- MMJ 2009 Spring Vol19 Issue1 Kouznetsov Jones Pp84 95Документ12 страницMMJ 2009 Spring Vol19 Issue1 Kouznetsov Jones Pp84 95Natala WillzОценок пока нет

- Dabur ChinaДокумент31 страницаDabur ChinaMustafa AhmedОценок пока нет

- Future of Democracy in PakistanДокумент12 страницFuture of Democracy in PakistanummeaimanОценок пока нет

- Democracy in Pakistan: Present Challenges and Future ProspectsДокумент5 страницDemocracy in Pakistan: Present Challenges and Future ProspectsParvez RaeesОценок пока нет

- Influence of Channels TV'S Politics Today On Abia Residents'Документ69 страницInfluence of Channels TV'S Politics Today On Abia Residents'jamessabraham2Оценок пока нет

- Barriers For International Automobile Industry To Enter in PakistanДокумент23 страницыBarriers For International Automobile Industry To Enter in PakistanWaqas AhmedОценок пока нет

- Comparing Transnational Crime in the US and IraqДокумент5 страницComparing Transnational Crime in the US and IraqJanah PagayОценок пока нет

- How and Why Has Multiparty Democracy Spread Over The Past 100 Years, and What Difference Has It Made To The Lives of The Poor?Документ17 страницHow and Why Has Multiparty Democracy Spread Over The Past 100 Years, and What Difference Has It Made To The Lives of The Poor?OxfamОценок пока нет

- Africa CoreДокумент171 страницаAfrica CoremdrjohnsonОценок пока нет

- Title Defense Chapter 1 and 2Документ10 страницTitle Defense Chapter 1 and 2jenny cerezoОценок пока нет

- Ashraf Ghani, Clare Lockhart Fixing Failed States A Framework ForДокумент1 страницаAshraf Ghani, Clare Lockhart Fixing Failed States A Framework ForDamoon Kavosh Aghebat BekheirОценок пока нет

- Pakis Army - Doctrne PDFДокумент69 страницPakis Army - Doctrne PDFRida0% (1)

- Huzaifa Majeed (Fa18-Bee-025) Assignment 4Документ4 страницыHuzaifa Majeed (Fa18-Bee-025) Assignment 4Israr Ul HassanОценок пока нет

- Governance CrisisДокумент2 страницыGovernance CrisisAzeem ChaudharyОценок пока нет

- Political Instability in Pakistan: Factors AnalysisДокумент32 страницыPolitical Instability in Pakistan: Factors Analysisshamk55j5sa kanwalOОценок пока нет

- The State and International RelationsДокумент16 страницThe State and International RelationsRodrigo Arenas CatalánОценок пока нет

- Poverty in Haiti - FinalДокумент7 страницPoverty in Haiti - Finalapi-439442790Оценок пока нет