Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Pithoprakta

Загружено:

Eduardo AguadoОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Pithoprakta

Загружено:

Eduardo AguadoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

XENAKIS Pithoprakta

In Metastasis (1953-4) and Pithoprakta (1955-6) Xenakis turned the traditional orchestral medium on its

head. He had grown up in Greece, studied civil engineering at the Athens Polytechnic, been active in

the demonstrations against Nazi deportations, and escaped after the post-war Junta issued a death

sentence. A refugee in Paris, he joined the office of Le Corbusier as an engineer; and it was this

experience, as well as the mass phenomena, chaos and violence he had witnessed in Greece, that

informed his first compositions. ‘I shall never forget the transformation of the regular, rhythmic noise

[marching] of a hundred thousand people into some fantastic disorder’ he later recalled.

Xenakis worked for Le Corbusier at a time when the latter was moving from rectangular slab

architecture to the flowing curvilinear asymmetry of the chapel at Ronchamp, arguably his

masterpiece. Le Corbusier’s first designs for Ronchamp date from 1950 and the building was

completed in 1955. How far Xenakis was involved is unclear, but he was a key assistant in Le

Corbusier’s next project, the Couvent de la Tourette, and principal architect of the iconic Philips

Pavilion built for the 1958 Brussels World Exhibition. It seems that his skill as a structural engineer

enabled Le Corbusier to realise a long obsession with non-orthogonal geometry stemming from an

admiration for Gaudi. Xenakis’s brilliant execution of the pavilion’s hyperbolic paraboloids (curved

concrete) is difficult to describe, but ‘a three-peaked nomadic tent’, ‘the interior of a cow’s stomach’,

have been two attempts.

Turning increasingly to composition, in Metastasis Xenakis transferred the radiating lines on his

drawing board into criss-cross glissandi for the strings. Superimposed string slides, each with a

different gradient, create huge sweeps of sound that expand and contract asymmetrically. The

plasticity and primal energy of the music was disturbingly new, and the first performance of Metastasis

was controversial. Pithoprakta was more daringly radical, more brilliantly intuitive, yet quickly hailed as

a masterpiece. The title means ‘actions through probabilities’. The work is scored for forty-six strings

(each with its own line), two trombones, a xylophone and a woodblock; and the many separate sounds

spread over a wide spectrum produce a granular effect, in which individual sounds lose their

importance to the benefit of the whole and their behaviour is governed by mathematical laws.

The piece opens with an insect-like cloud of unpitched tapping, punctuated by a single stroke on the

woodblock: the first of its startling interjections throughout the score. Pitches enter, angular and

forceful played with short bow strokes. The texture grows wilder and more chaotic, eventually settling

in a sustained, 46-note cluster illuminated by a single pitch repeated on the xylophone. Into this dense

mass is injected a frenzied plucking at different speeds. (Both the cluster and pizzicati are uncannily

prescient of Ligeti). After a moment of silence, criss-cross glissandi ensue, punctuated by ever longer

gaps, before an extended section of disparate activity delivers enormous energy, although within a

basically static cloud. The only entry of the trombones (also with glissandi) is thrillingly timed, and

heralds the single instance in the score where the strings pluck in rhythmic unison. It is a powerful

conjunction, gradually fragmenting in brief after-shocks separated by silence. The final silence is

broken into by a mass of swooping glissandi that gradually settle in a dense cluster like a swarm of

bees, before evaporating in the upper reaches of the violins.

© Richard Steinitz

Вам также может понравиться

- XenakisДокумент11 страницXenakisscribd222youОценок пока нет

- Electroacousticmusic of XenakisДокумент26 страницElectroacousticmusic of Xenakisrhyscorr100% (1)

- Xenakis-English PagesДокумент3 страницыXenakis-English PagesnicholasakersОценок пока нет

- Analysis of Xenakis JonchaiesДокумент14 страницAnalysis of Xenakis JonchaiesKenny KwanОценок пока нет

- Becoming The Synthifoustockhausen and The New KeyboardismДокумент8 страницBecoming The Synthifoustockhausen and The New Keyboardismwei wuОценок пока нет

- Xenakis Electronic MusicДокумент1 страницаXenakis Electronic MusicCharlex López100% (1)

- Gilles Deleuze - The Fold - Leibniz and The BaroqueДокумент96 страницGilles Deleuze - The Fold - Leibniz and The Baroqueevrim_devrim100% (4)

- London, Proms 2012 (2) - Olga Neuwirth, Kaija SaariahoДокумент4 страницыLondon, Proms 2012 (2) - Olga Neuwirth, Kaija Saariahostis73Оценок пока нет

- Piranesi and The Infinite Prisons: Spatial VisionДокумент16 страницPiranesi and The Infinite Prisons: Spatial VisionAli AhmedОценок пока нет

- Bloch 2006 Ombook VuzacanonsДокумент13 страницBloch 2006 Ombook VuzacanonsNicola MonopoliОценок пока нет

- Iannis Xenakis' Contributions To 20 Century Atonal Harmony and To The History of Equal TemperamentДокумент12 страницIannis Xenakis' Contributions To 20 Century Atonal Harmony and To The History of Equal TemperamentAglaias100% (1)

- Iannis Xenakis's Polytopes: (Textes Et Dessin Pour Ronchamp, Le Corbusier, Swiss 1965)Документ10 страницIannis Xenakis's Polytopes: (Textes Et Dessin Pour Ronchamp, Le Corbusier, Swiss 1965)Philipp OswaltОценок пока нет

- Kotz 2009 Dia Neuhaus ProofДокумент10 страницKotz 2009 Dia Neuhaus Proofvincent216Оценок пока нет

- Microtonality A Selective Overview PDFДокумент32 страницыMicrotonality A Selective Overview PDFMagritt100% (1)

- Music of Sound and LightДокумент12 страницMusic of Sound and LightrhyscorrОценок пока нет

- Electroacoustic Music of Iannis XenakisДокумент25 страницElectroacoustic Music of Iannis XenakisipiresОценок пока нет

- Choreographic Objects: Stifters DingeДокумент14 страницChoreographic Objects: Stifters DingeamrОценок пока нет

- Review Author(s) : Caroline Rae Review By: Caroline Rae Source: Tempo, New Series, No. 216 (Apr., 2001), Pp. 55-58 Published By: Cambridge University Press Accessed: 04-08-2016 07:15 UTCДокумент5 страницReview Author(s) : Caroline Rae Review By: Caroline Rae Source: Tempo, New Series, No. 216 (Apr., 2001), Pp. 55-58 Published By: Cambridge University Press Accessed: 04-08-2016 07:15 UTCFrancesco DominiciОценок пока нет

- Xenakis - Iannis - Formalized Music. Thought and Mathematics in CompositionДокумент399 страницXenakis - Iannis - Formalized Music. Thought and Mathematics in CompositionLuis Javier Rodriguez100% (14)

- The Opening Section of Mozart's FantasyДокумент15 страницThe Opening Section of Mozart's FantasyAdriano Moreira VilelaОценок пока нет

- Art of Projection-GunningДокумент7 страницArt of Projection-GunningvisualgrooveОценок пока нет

- 2004 - Sharpe - A Little Piece of The Real PDFДокумент281 страница2004 - Sharpe - A Little Piece of The Real PDFAna SilvaОценок пока нет

- Edgar Varese PDFДокумент16 страницEdgar Varese PDFGilson BarbozaОценок пока нет

- Tom Gunning - Illusions Past and Future (Phantasmagoria)Документ17 страницTom Gunning - Illusions Past and Future (Phantasmagoria)lapaupierenoireОценок пока нет

- RadulescuДокумент4 страницыRadulescubigbigbig90003270100% (1)

- Eisenstein - The Psychology of Composition PDFДокумент69 страницEisenstein - The Psychology of Composition PDFRadu CrăciunОценок пока нет

- Introduction: Spectral Thinking: Jonathan CrossДокумент7 страницIntroduction: Spectral Thinking: Jonathan Crossmarcus motaОценок пока нет

- Catacoustic Enchantment The Romantic Con PDFДокумент30 страницCatacoustic Enchantment The Romantic Con PDFdj_salinger6212Оценок пока нет

- Daniel Birnbaum 02 PDFДокумент5 страницDaniel Birnbaum 02 PDFaleОценок пока нет

- Scelsi and MessiaenДокумент5 страницScelsi and MessiaenmozartsecondОценок пока нет

- Iii Heliostásion MmxiiДокумент9 страницIii Heliostásion MmxiiGustave GusОценок пока нет

- Jean Jacques Nattiez The Battle of Chronos and Orpheus Essays in Applied Musical Semiology Trans Jonathan Dunsby Oxford Oxford University Press 2003 Isbn 0 19 816610 9 HBДокумент3 страницыJean Jacques Nattiez The Battle of Chronos and Orpheus Essays in Applied Musical Semiology Trans Jonathan Dunsby Oxford Oxford University Press 2003 Isbn 0 19 816610 9 HBDeise ElenОценок пока нет

- Exegesis:When We Build Let Us Think That We Build ForeverДокумент6 страницExegesis:When We Build Let Us Think That We Build Forevertemporarysite_orgОценок пока нет

- Xenakis - Formalized Music Thought and Mathematics in CompositionДокумент201 страницаXenakis - Formalized Music Thought and Mathematics in CompositionConstantinos MiltiadisОценок пока нет

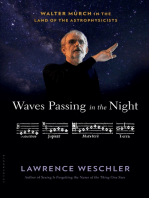

- Waves Passing in the Night: Walter Murch in the Land of the AstrophysicistsОт EverandWaves Passing in the Night: Walter Murch in the Land of the AstrophysicistsРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (1)

- Concentrationary Art: Jean Cayrol, the Lazarean and the Everyday in Post-war Film, Literature, Music and the Visual ArtsОт EverandConcentrationary Art: Jean Cayrol, the Lazarean and the Everyday in Post-war Film, Literature, Music and the Visual ArtsОценок пока нет

- Intervention2 Xenakis ElectroacoustiqueДокумент12 страницIntervention2 Xenakis ElectroacoustiqueOlga JankovicОценок пока нет

- The Art of Noise Futurist Manifesto 1913Документ16 страницThe Art of Noise Futurist Manifesto 1913Onur DülgerОценок пока нет

- CMR-LACHENMANN-Composing in The Shadow of DarmstadtДокумент12 страницCMR-LACHENMANN-Composing in The Shadow of DarmstadtmluisabalОценок пока нет

- The Concept of 'Alea' in Boulez's 'Constellation-Miroir'Документ11 страницThe Concept of 'Alea' in Boulez's 'Constellation-Miroir'ssiiuullLLОценок пока нет

- Paper, Xenakis Composer Architect VisionaryДокумент5 страницPaper, Xenakis Composer Architect VisionarymusimathicsОценок пока нет

- The History of Avantgarde Music2Документ9 страницThe History of Avantgarde Music2Giorgio MagnanensiОценок пока нет

- The Five Senses in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art - Carl NordenfalkДокумент32 страницыThe Five Senses in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art - Carl NordenfalkAntonietta BiagiОценок пока нет

- Steinjtz - Music Maths ChaosДокумент8 страницSteinjtz - Music Maths ChaosFiammettaОценок пока нет

- The Tempest, ThemeДокумент11 страницThe Tempest, ThemeMalik NawazОценок пока нет

- The Ancients and the Postmoderns: On the Historicity of FormsОт EverandThe Ancients and the Postmoderns: On the Historicity of FormsРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (6)

- Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche: After the Old Roguish Manner - in Rondo Form - Tone Poem Op. 28От EverandTill Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche: After the Old Roguish Manner - in Rondo Form - Tone Poem Op. 28Оценок пока нет

- A Photographic Guide to the History of the Shadow Puppet Theatre in the WestОт EverandA Photographic Guide to the History of the Shadow Puppet Theatre in the WestОценок пока нет

- Astonish Me!: First Nights That Changed the WorldОт EverandAstonish Me!: First Nights That Changed the WorldРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Troublant Bolero - ChordsДокумент1 страницаTroublant Bolero - ChordsLuc BartoliОценок пока нет

- Now o Now I Needs Must PartsДокумент2 страницыNow o Now I Needs Must PartsEduardo AguadoОценок пока нет

- Gradual Process Music 2 PDFДокумент63 страницыGradual Process Music 2 PDFEduardo Aguado100% (1)

- Psicologia de La Musica y Educacion Musical PDFДокумент161 страницаPsicologia de La Musica y Educacion Musical PDFEduardo AguadoОценок пока нет

- Seven English Songs: by Rosseter, Johnson and DowlandДокумент10 страницSeven English Songs: by Rosseter, Johnson and DowlandEduardo Aguado100% (1)

- Seven English Songs: by Rosseter, Johnson and DowlandДокумент10 страницSeven English Songs: by Rosseter, Johnson and DowlandEduardo Aguado100% (1)

- Guthrie Govan Waves (v0.15)Документ12 страницGuthrie Govan Waves (v0.15)goorguerОценок пока нет

- Want A Parrot TabДокумент17 страницWant A Parrot TabJavier Tonatiuh Carbajal100% (5)

- Erotic Cakes - Guthrie Govan - Transcriptions PrintableДокумент59 страницErotic Cakes - Guthrie Govan - Transcriptions Printablefranferraris97% (61)

- Guthrie Govan Waves (v0.15)Документ12 страницGuthrie Govan Waves (v0.15)goorguerОценок пока нет

- Fish50 Write UpДокумент3 страницыFish50 Write UpSophia ManzanoОценок пока нет

- Security Gap Analysis Template: in Place? RatingДокумент6 страницSecurity Gap Analysis Template: in Place? RatingVIbhishan0% (1)

- Right To Freedom From Torture in NepalДокумент323 страницыRight To Freedom From Torture in NepalAnanta ChaliseОценок пока нет

- Checklist of Requirements of Special Land Use PermitДокумент1 страницаChecklist of Requirements of Special Land Use PermitAnghelita ManaloОценок пока нет

- Ips Rev 9.8 (Arabic)Документ73 страницыIps Rev 9.8 (Arabic)ahmed morsyОценок пока нет

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentДокумент6 страницNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentJasmine KumariОценок пока нет

- Geotech Report, ZHB010Документ17 страницGeotech Report, ZHB010A.K.M Shafiq MondolОценок пока нет

- United States Court of Appeals Fifth CircuitДокумент4 страницыUnited States Court of Appeals Fifth CircuitScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Communication Systems: James Flynn Sharlene KatzДокумент15 страницIntroduction To Communication Systems: James Flynn Sharlene KatzAnisari MeiОценок пока нет

- 17-05-MAR-037-01 凱銳FCC Part15B v1Документ43 страницы17-05-MAR-037-01 凱銳FCC Part15B v1Nisar AliОценок пока нет

- Due Date: 29-12-2021: Fall 2021 MTH104: Sets and Logic Assignment No. 1 (Lectures # 16 To 18) Total Marks: 10Документ3 страницыDue Date: 29-12-2021: Fall 2021 MTH104: Sets and Logic Assignment No. 1 (Lectures # 16 To 18) Total Marks: 10manzoor ahmadОценок пока нет

- HARRISON 1993 - The Soviet Economy and Relations With The United States and Britain, 1941-45Документ49 страницHARRISON 1993 - The Soviet Economy and Relations With The United States and Britain, 1941-45Floripondio19Оценок пока нет

- ERP ConceptsДокумент27 страницERP ConceptsPranav JainОценок пока нет

- Draft DAO SAPA Provisional AgreementДокумент6 страницDraft DAO SAPA Provisional AgreementStaff of Gov Victor J YuОценок пока нет

- Klarna: Klarna A Company Valued To Be 5.5 Billion and 8 Most Valued Fintech Company in The WorldДокумент1 страницаKlarna: Klarna A Company Valued To Be 5.5 Billion and 8 Most Valued Fintech Company in The WorldChetan NarasannavarОценок пока нет

- State Public Defender's Office InvestigationДокумент349 страницState Public Defender's Office InvestigationwhohdОценок пока нет

- Arthropods: Surviving The Frost: Charmayne Roanna L. GalangДокумент2 страницыArthropods: Surviving The Frost: Charmayne Roanna L. GalangBabes-Rose GalangОценок пока нет

- Planning and Design of A Cricket StadiumДокумент14 страницPlanning and Design of A Cricket StadiumTenu Sara Thomas50% (6)

- 2beloved Lizzo PDFДокумент1 страница2beloved Lizzo PDFAntwerpQueerChoir AQCОценок пока нет

- ISCOM5508-GP (A) Configuration Guide (Rel - 02)Документ323 страницыISCOM5508-GP (A) Configuration Guide (Rel - 02)J SofariОценок пока нет

- Order of Nine Angles: RealityДокумент20 страницOrder of Nine Angles: RealityBrett StevensОценок пока нет

- MoMA Learning Design OverviewДокумент28 страницMoMA Learning Design OverviewPenka VasilevaОценок пока нет

- Roger Dean Kiser Butterflies)Документ4 страницыRoger Dean Kiser Butterflies)joitangОценок пока нет

- JLPT N2 Vocab - 04Документ345 страницJLPT N2 Vocab - 04raj_kumartОценок пока нет

- Snap Fasteners For Clothes-Snap Fasteners For Clothes Manufacturers, Suppliers and Exporters On Alibaba - ComapparelДокумент7 страницSnap Fasteners For Clothes-Snap Fasteners For Clothes Manufacturers, Suppliers and Exporters On Alibaba - ComapparelLucky ParasharОценок пока нет

- 5 L&D Challenges in 2024Документ7 страниц5 L&D Challenges in 2024vishuОценок пока нет

- CBDCs For Dummies Everything You Need ToДокумент18 страницCBDCs For Dummies Everything You Need Tolati.training7Оценок пока нет

- Windows Kernel Exploitation Tutorial Part 5: NULL Pointer DereferenceДокумент7 страницWindows Kernel Exploitation Tutorial Part 5: NULL Pointer DereferenceRonaldMartinezОценок пока нет

- Lipid Metabolism Quize PDFДокумент5 страницLipid Metabolism Quize PDFMadani TawfeeqОценок пока нет

- Child Health Services-1Документ44 страницыChild Health Services-1francisОценок пока нет