Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Cme Reviewarticle: Uterine Inversion: A Review of A Life-Threatening Obstetrical Emergency

Загружено:

MochHabibEl-HuseinyОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Cme Reviewarticle: Uterine Inversion: A Review of A Life-Threatening Obstetrical Emergency

Загружено:

MochHabibEl-HuseinyАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Volume 73, Number 7

OBSTETRICAL AND GYNECOLOGICAL SURVEY

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health,

Inc. All rights reserved. CME REVIEW ARTICLE

CHIEF EDITOR'S NOTE: This article is part of a series of continuing education activities in this Journal through which a total of

17

36 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ can be earned in 2018. Instructions for how CME credits can be earned appear on the last page

of the Table of Contents.

Uterine Inversion: A Review of a

Life-Threatening Obstetrical Emergency

Michael P. Wendel, MD,* Kelsey L. Shnaekel, MD,* and Everett F. Magann, MD†

*Resident and †Professor, Maternal-Fetal Medicine Fellowship Director, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology,

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/obgynsurvey by BhDMf5ePHKbH4TTImqenVBhf5K8zlU/3yukil0BNYXW3AtoC9CwHguh1VodSy19u on 08/09/2018

Importance: Uterine inversion is frequently accompanied by postpartum hemorrhage and hypovolemic shock. Mor-

bidity and mortality occur in as many as 41% of cases. Prompt recognition and management are of utmost importance.

Objective: The aim of this review is to describe risk factors, clinical and radiographic diagnostic criteria, and

management of this rare but potentially life-threatening complication of pregnancy.

Evidence Acquisition: A PubMed, Web of Science, and CINAHL search was undertaken with no limitations on

the number of years searched.

Results: There were 86 articles identified, with 25 being the basis of review. Multiple risk factors for a uterine

inversion have been suggested including a morbidly adherent placenta, short umbilical cord, congenital weak-

ness of the uterine wall or cervix, weakening of the uterine wall at the placental implantation site, fundal implan-

tation of the placenta, uterine tumors, uterine atony, sudden uterine emptying, fetal macrosomia, manual removal

of the placenta, inappropriate fundal pressure, excessive cord traction, and the use of uterotonic agents prior to

placental removal. The diagnosis is almost exclusively clinical, and successful treatment depends on prompt rec-

ognition of the uterine inversion. Treatment options include manual and surgical replacement of the inverted

uterus. There is no consensus regarding mode of delivery in subsequent pregnancies as reinversion in a subse-

quent pregnancy is unpredictable. However, if surgical replacement was required in the index pregnancy and in-

volved an incision into the contractile portion of the uterus, cesarean delivery is a reasonable management option

similar to that offered for a prior classic cesarean section.

Conclusions: Successful treatment is dependent on prompt recognition. Management should include resus-

citation of maternal hypovolemic shock, as well as repositioning of the inverted uterine fundus.

Relevance: Uterine inversion is a rare but potentially life-threatening obstetrical emergency.

Target Audience: Obstetricians and gynecologists, family physicians.

Learning Objectives: After completing this activity, the learner should be better able to evaluate published

literature regarding puerperal uterine inversion, assess its associated comorbidities and risk factors, define clinical

and radiographic diagnostic criteria to assist in prompt recognition and management of this obstetrical emergency,

and propose management options for future pregnancies.

Uterine inversion is an obstetrical complication in in the literature from 1887 to 2006.1 The condition is

which the uterine fundus collapses into the endometrial frequently accompanied by postpartum hemorrhage

cavity. Overwhelmingly, inversion is a puerperal event, and hypovolemic shock. Prompt recognition and man-

with only 150 cases of nonpuerperal inversion reported agement are of utmost importance as morbidity and

mortality of an acute uterine inversion occur in as many

All authors, faculty, and staff in a position to control the content of as 41% of cases. Prompt management has all but elim-

this CME activity and their spouses/life partners (if any) have disclosed inated maternal mortality.2

that they have no financial relationships with, or financial interests in,

Inversion is a rare puerperal complication, with a re-

any commercial organizations pertaining to this educational activity.

Correspondence requests to: Everett F. Magann, MD, University of

ported incidence ranging from 1 in 20,312 to 1 in

Arkansas for the Medical Sciences, 4301 W Markham St, #518, Little 1739 deliveries.3,4 A recent 10-year study in the United

Rock, AR 72205. E-mail: efmagann@uams.edu. States found 2427 cases in 8,294,279 deliveries from

www.obgynsurvey.com | 411

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

412 Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey

2004 to 2013, or approximately 1 in 3448 deliveries.5 inversion” OR “inverted” and “uterus” and “puerperal.”

Despite the rarity of a uterine inversion, it remains a The search was limited to the English language, and

true obstetrical emergency. Early reports estimated the there were no limitations on the years searched. Two

maternal mortality rates as high as 15%,5 but in more authors (M.P.W. and K.L.S.) independently reviewed

recent studies, no maternal deaths have been reported all of the abstracts and the full articles that discussed

in “high-resource countries” in some time. In contrast, uterine inversion or inverted uterus. In addition, the ref-

in “low-income countries,” mortality due to cases of erences of the articles were reviewed for any additional

acute uterine inversion is still a reality.4 Significant relevant articles. Inclusion criteria included any arti-

morbidity, however, remains a very real concern. Pa- cle that discussed risk factors, diagnosis, management,

tients whose uteri invert following delivery are more or complications of the inverted uterus in pregnancy.

likely to have postpartum hemorrhage and maternal hy- Eighty-six abstracts were reviewed, and 25 full-text ar-

povolemic shock and require a blood transfusion. In ad- ticles were used as the basis of this review (Fig. 2).

dition, these patients are at greater risk of requiring

surgical management and/or a hysterectomy, although RISK FACTORS

fewer than 10% of all cases from 2004 to 2013 required

surgical intervention.5 The etiology of uterine inversion is not well under-

Uterine inversion is classified both by the timing and stood, and in as many as 50% of cases, no precipitating

degree of inversion. Inversion can be acute, subacute, factor can be identified.7 However, several factors have

or chronic. If the diagnosis is made within 24 hours, been proposed that may increase the risk of inversion;

the inversion is acute. If the diagnosis is made after placenta accreta, short umbilical cord, congenital weak-

4 weeks, it is a chronic inversion, and diagnosis at more ness of the uterine wall or cervix, weakening of the

than 24 hours and less than 4 weeks is subacute. Degree uterine wall at the placental implantation site, fundal

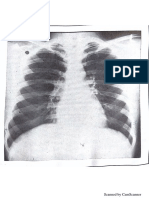

of inversion can be classified from first to fourth (Fig. 1). implantation of the placenta, uterine tumors, uterine

First-degree inversion occurs when the corpus or wall of atony, sudden uterine emptying, fetal macrosomia,

the uterus extends to the cervix but does not protrude be- manual removal of the placenta, inappropriate fundal

yond the cervical ring. In second-degree inversion, the pressure, excessive cord traction, and use of uterotonic

corpus passes through the cervical ring but does not agents prior to placental removal have all been associ-

reach the perineum. In third-degree inversion, the fundus ated with uterine inversion.2 Coad et al5 also found that

extends to the perineum, and finally, if the vagina inverts a prolonged labor can also lead to an increased risk of

along with the uterus past the perineum, the inversion is uterine inversion. In particular, uterine tumors are asso-

deemed to be a fourth-degree inversion.6 ciated with nonpuerperal inversion1; however, this is

beyond the scope of this review.

More recently, some studies have challenged whether

METHODS

some traditional risk factors really play a role in uterine

PubMed, Web of Science, and CINAHL were searched inversion. Earlier case reports attributed up to 50% of

using the search terms “inverted uterus” OR “uterine cases of uterine inversion to mismanagement of the

FIG. 1. Inverted uterus—degrees of inversion.

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Uterine Inversion • CME Review Article 413

FIG. 2. Flow diagram of literature review.

third stage of labor with Credé fundal pressure, exces- 37.7% of the 2427 inversion cases, and 22.4% of all

sive cord traction, or both, leading to an inverted uterus. cases required a blood transfusion. Maternal hypovole-

More recent studies have hypothesized this is not a mic shock was reported in 39% of cases in Watson and

true risk factor but merely an event that may precipitate colleagues'4 study and in 32% in a study by Brar et al.9

inversion in a uterus prone to do so.5 The paucity of Similarly, Coad and colleagues'5 nationwide cohort

cases despite widespread acceptance of active third-

stage labor management lends credence to this theory.

Primiparity has also long been proposed as a risk factor,

primarily due to the increased incidence of placenta TABLE 1

Risk Factors

fundal implantation in this population.8 However, even

in studies where primiparas represent a large proportion Maternal

• Uterine structural anomalies

of uterine inversions, the percentage of primiparous pa-

• Uterine tumors

tients in the population studied is roughly equivalent to • Connective tissue disorder

multiparas.3,4 In the national cohort by Coad et al,5 fetal • Congenital weakness of uterine wall or cervix

macrosomia was not found to be a statistically signifi- • Weakening of the uterine wall at placenta implantation

cant risk factor despite its historical place among the Placenta

• Fundal placenta

risk factors for uterine inversion (Table 1).

• Morbidly adherent placenta

• Umbilical cord

• Short umbilical cord

DIAGNOSIS Fetus

The diagnosis of uterine inversion is almost exclu- • Fetal macrosomia

Labor

sively a clinical diagnosis. The most common features

• Uterine atony

of inversion are postpartum hemorrhage, hypovolemic • Precipitous labor

shock, and abdominopelvic pain.2 Watson et al4 observed Iatrogenic

that hemorrhage was seen in 94% of cases with an 18- • Inappropriate fundal pressure

case study published in 1980. In Coad and colleagues'5 • Poor management of the third stage of labor

• Manual removal of the placenta

nationwide study, maternal hemorrhage occurred in

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

414 Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey

reported a much lower incidence, with only 32 total study. Magnetic resonance imaging is especially useful

cases of shock, which was only 1.3% of all inversion in operative planning in cases of inversion caused by

cases. Despite this small percentage, patients experienc- mass lesions. In addition to diagnosis of inversion, MRI

ing an inverted uterus were found to be 76.9 times more can help to evaluate morphologic changes in the uterus,

likely to experience shock compared with patients with origin of potential mass lesions, signal, and contrast

deliveries not complicated by inversion.6 Early reports enhancement of potential lesions. Contrast-enhanced

frequently describe shock out of proportion to blood studies are preferred to help fully evaluate masses for

loss. This was most likely due to either gross underesti- lesions. There are characteristic appearances on both

mation of blood loss or increased vagal tone caused by axial and sagittal views. Axial images will show a sim-

stretching of the broad ligament and peritoneal nerves, ilar “bull's-eye” or target configuration as on ultrasound

as well as pressure on the ovaries as they are pulled into views created by a hyperintense endometrium surrounded

the inverted uterus.2 However, rapid recognition along by a second hyperintense rim. Sagittal views will show

with fluid resuscitation and proper management seems a characteristic V-shaped uterine cavity surrounded by

to have limited the amount of cases that have postpartum the inverted fundus. Again, MRI is rarely used for ini-

hemorrhage or progress to hypovolemic shock.2,6 tial diagnosis but is useful for confirmation and delin-

In addition to common signs and symptoms, phys- eating the mass lesion from surrounding structures.12,13

ical examination findings are key in diagnosing uterine

inversion. The bimanual examination is probably the

TREATMENT

most useful physical examination in a situation when

a clinician suspects uterine inversion. Abdominally, Successful treatment hinges on the ability to quickly

the fundus will not be palpable in the correct anatomic recognize this morbid pregnancy complication. As stated

position, and in patients with a thin abdominal wall, previously within this article, clinical symptoms such as

a cuplike depression indicating the collapsed fundus hypovolemia and shock, which may seem out of propor-

may be noted.2 A soft, congested, bleeding mass found tion to the actual blood loss, are often the first signs.2,10

in the vagina is virtually diagnostic, and “if the placenta Prompt treatment with aggressive fluid resuscitation

is still attached, an error in the diagnosis is impossi- and blood transfusion should be initiated. Two large-

ble.”2,10 Diagnosis during cesarean section is largely bore intravenous lines should be placed, and anesthesia

made by direct visualization of inversion of the fundus should be notified to aid in pain control if transition

through the uterine incision with either a partially or to the operating room becomes necessary. Additional

completely attached placenta.3 staff to assist in the resuscitation should be mobilized.

In cases of subacute or chronic inversion or even first- Uterotonic agents should be stopped, and attempt should

degree inversions, diagnosis may not be as quickly be made to manually replace the uterus. Tocolytic agents

apparent. The uterine fundus may be mistaken for a such as terbutaline and magnesium should be availa-

uterine polyp or prolapsed fibroid.2 In these situations, ble but are not required in all cases of inversion.14 There

ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been controversy regarding management of the pla-

have proven to be effective means of diagnosis. Ultra- centa when it is still in place attached to the uterus. Some

sound can be used both transabdominally or vaginally. authors advocate removal prior to replacement as this de-

Transabdominally, in the transverse plane, a character- creases the bulk of the uterus and may allow for easier

istic “target sign” can be seen. A hyperechoic fundus repositioning. Other investigators advocate leaving the

surrounded by a hypoechoic rim created by the space placenta attached in situ with the theory that the attached

between the endometrium and vaginal walls creates this placenta may prevent excessive hemorrhage and pre-

characteristic appearance. In the sagittal plane, a first- vent further exacerbation of maternal shock.2,5,9

degree inversion may have a Y-shaped endometrium Repositioning of the uterus can be accomplished in a

as the fundus collapses toward the cervix. In second- number of ways. Johnson15 was the first to describe

degree inversions, the uterus appears as a mirror image manual replacement of the inverted uterus (Fig. 3). With

of itself with the 2 serosal edges creating a pseudo en- the Johnson maneuver, the surgeon's entire hand is posi-

dometrial stripe as the entire uterus has inverted into tioned within the vagina, with the tips of the fingers at

the vagina through the cervix. Transvaginally, when the the uterocervical junction and the fundus held in the

transducer is in contact with the fundus, a similar mir- palm. The uterus is then lifted out of the pelvis and ele-

rored uterus is seen.11–13 vated above the level of the umbilicus. This maneuver

While ultrasonography is the first-line imaging mo- causes the uterine ligaments to stretch, which causes the

dality for suspected inversion in either puerperal or non- cervical ring to widen and allows the fundus to move back

puerperal cases, MRI can be a useful adjunctive imaging through the cervical ring and to its anatomical position.

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Uterine Inversion • CME Review Article 415

FIG. 3. Inverted uterus—manual method of repair.

Once repositioned, the uterus is held in position for 3 to clamps are placed on the uterus at the round ligaments,

5 minutes.2,4,5,10 Henderson and Alles16 described a and gentle upward traction is applied. The Allis clamps

slight modification on this by applying ringed forceps are replaced and advanced sequentially below the pre-

to the cervical ring to allow for countertraction. Another vious clamps, and this process is repeated until fundus

nonsurgical method includes the O'Sullivan maneuver, is replaced (Fig. 4). If this procedure fails to reduce the

described in 1945, which involves the use of hydro- inversion, another abdominal surgical approach is the

static pressure to replace the uterus. The surgeon uses Haultain procedure, in which a horizontal hysterotomy,

normal saline hung to gravity with a catheter placed 5 to 6 cm in length, is made in the posterior portion of

within the vagina, with the operator's hand used to the lower uterine wall through the cervical ring. The

block the introitus to prevent escape of fluid. As the posterior wall is incised in order to avoid the bladder,

vaginal walls distend, the hydrostatic pressure forces which is usually drawn into the inverted uterine cavity.

the fundus upward into its original position. Another im- By making this incision in the posterior uterine wall

portant aspect of management for replacement, whether and cervical ring, this increases the size of the opening

conservative and manual or surgical, includes the choice and allows easier facilitation of the Huntington proce-

of anesthesia to maximize both pain control and uterine dure. The hysterotomy is closed in usual fashion.2,4,10

and cervical relaxation.2 A vaginal surgical approach has also been described,

Attempts at conservative approaches should be the the Spinelli procedure. With this procedure, a trans-

first and foremost; however, surgeons should not hesi- verse incision is made in the anterior vaginal wall above

tate to pursue surgical management options when con- the anterior cervical lip and includes the anterior uterine

servative measures fail. If nonoperative replacement is wall. With this, the split uterus is repositioned by apply-

not successful, surgical approaches should be utilized. ing upward pressure in the fundus. The anterior uterine

Surgical approaches for replacement can be categorized wall is closed in 2 layers from the vaginal approach and

into abdominal versus vaginal approaches. Huntington results in a vertical incision similar to that with a classic

et al17 described abdominal replacement of the uterus in cesarean section.8 A few authors have suggested lapa-

which, after laparotomy, the inversion is identified, Allis roscopic reduction because of benefits such as smaller

FIG. 4. Inverted uterus—surgical method of repair.

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

416 Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey

incision, less pain, and early recovery; however, this theorized that placement of balloon conforms to the

has been highly scrutinized because of the emergent contours of the uterus to maintain position.22–26 Many

nature of inversion. The consensus still remains that, authors agree regarding management of uterine atony

in the setting of hemodynamic instability, laparotomy and continued postpartum hemorrhage. Hysterectomy

is preferred.1,18 may be required if other methods of repositioning and

Following replacement, the uterus may become atonic, control of hemorrhage are unsuccessful.

especially if tocolytics were used to aid in replacement;

therefore, uterotonics should be used. Historically, oxy-

MANAGEMENT OF SUBSEQUENT

tocin (Pitocin), ergots, prostaglandins, and fundal mas-

PREGNANCIES

sage have been administered and performed to promote

tonicity. Administration of prophylactic antibiotics after Management for subsequent pregnancies is described

uterine inversion and replacement remains controver- throughout the literature. Many sources recommend

sial. A prevailing belief is that the inverted uterus ex- delivery in the hospital. Some authors recommended

poses the endometrial surfaces to the vaginal flora and surgical delivery, whereas others discourage this be-

increases the risk of infection. Two small studies, how- cause there is no guarantee against recurrence. Regard-

ever, did not find any benefit to the use of prophylactic less, most agree that delivery should occur in a facility

antibiotic administration. Regardless of method of re- with resources for general anesthesia and blood transfu-

placement, it is important to explore the uterus to rule sion as necessary.

out any possibility of uterine rupture, which is a rare An additional literature search was performed regard-

and devastating complication2,4,5,10 (Table 2). ing management of subsequent pregnancies in which

surgical replacement was performed without consen-

sus. It is reasonable to offer cesarean section for those

COMPLICATIONS who required surgical intervention with Haultain or

Several case series have discussed complications as- Spinelli maneuver because of incision into the con-

sociated with uterine inversion and subsequent uterine tractile portion of the uterus similar to classic uterine

atony resulting in significant postpartum hemorrhage incision.27 In addition, this should be performed in the

and shock. Multiple authors describe uterine inversion elective setting with planned delivery. However, no

during cesarean section.11,19 Several authors have de- studies have been done that support this theory, most

scribed management of subsequent uterine atony with likely because of low incidence of uterine inversion as

variations of uterine suturing techniques.20,21 Recurrent well as the low incidence of those requiring surgical

acute reinversion was noted in multiple case reports. intervention.

Multiple authors described successful treatment of re-

inversion with intrauterine tamponade balloon to aid CONCLUSIONS

in preservation in position of uterine fundus. It has been

Uterine inversion is a rare and potentially life-threatening

complication of pregnancy that occurs during or after

TABLE 2 the third stage of labor. There are many suggested risk

Management factors; however, the predictability of these is un-

Supportive known. Uterine inversion is a clinical diagnosis and

• Call for help, ie, anesthesia, additional staff, experienced physician should be considered in any patient with symptoms of

• Aggressive fluid resuscitation—2 large-bore intravenous hemorrhage, hypovolemic shock, and abdominopelvic

access lines pain, with the physical findings of a soft, congested,

• Blood replacement

bleeding mass within the vagina on bimanual examina-

• Foley placement

• Pain control tion. Treatment should be prompt and almost intuitive,

• Stop uterotonic medications with emphasis placed on management of resuscitation

Uterine Replacement of hypovolemia and replacement of uterine fundus to

• Anesthesia—general its appropriate anatomical position. Recurrence in sub-

• Tocolytics—magnesium or terbutaline

sequent pregnancies is unpredictable, and there are no

• Nonsurgical techniques—Johnson, O'Sullivan

• Surgical techniques—Huntington, Haultain, Spinelli recommendations regarding the need for surgical deliv-

Subsequent Management ery outside routine obstetrical indications. However, if

• Uterine massage replacement required surgical correction with incision

• Uterotonic medications—Pitocin, methergine (Methergine), within the contractile portion of the uterus, subsequent

carboprost tromethamine (Hemabate)

delivery with scheduled cesarean section is reasonable,

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Uterine Inversion • CME Review Article 417

similar to management of those with previous classic 13. Ward H. O'Sullivan's hydrostatic reduction of an inverted uterus:

sonar sequence recorded. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;12:

cesarean section. 283–286.

14. Achanna S, Mohamed Z, Krishnan M. Puerperal uterine inver-

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS sion: a report of four cases. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2006;32:

The authors thank Shelia Thomas, MA (LS), Medical 341–345.

15. Johnson AB. A new concept in the replacement of the inverted

Research and Clinical Search Services coordinator, uterus and a report of nine cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences 1949;57:557–562.

Library for her assistance in their literature search. 16. Henderson H, Alles RW. Puerperal inversion of the uterus. Am J

Obstet Gynecol. 1948;56:133–142.

The authors also thank Donna Eastham, BA, CRS, for 17. Huntington JL, Irving FC, Kellog FS. Abdominal reposition in

her help in editing and submitting the manuscript. acute inversion of the puerperal uterus. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

1928;15:34–40.

18. Vijayaraghavan R, Sujatha Y. Acute postpartum uterine inversion

REFERENCES with haemorrhagic shock: laparoscopic reduction: a new method

1. Auber M, Darwish B, Lefebure A, et al. Management of of management. BJOG. 2006;113:1100–1102.

nonpuerperal uterine inversion using a combined laparoscopic 19. Nag DS, Datta MR, Samaddar DP, et al. Cardiac arrest following

and vaginal approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:e7–e9. acute puerperal uterine inversion. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:

2. Wendel PJ, Cox SM. Emergent obstetric management of uterine bcr2014207175.

inversion. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1995;22:261–274. 20. Mondal PC, Ghosh D, Santra D, et al. Role of Hayman technique

3. Witteveen T, Van Stralen G, Zwart J, et al. Puerperal uterine inver- and its modification in recurrent puerperal uterine inversion.

sion in the Netherlands: a nationwide cohort study. Acta Obstet J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38:438–441.

Gynecol Scand. 2013;92:334–337. 21. Matsubara S, Yano H, Taneichi A, et al. Uterine compression su-

4. Watson P, Besch N, Bowes WA Jr. Management of acute and ture against impending recurrence of uterine inversion immedi-

subacute puerperal inversion of the uterus. Obstet Gynecol. ately after laparotomy repositioning. J Obstet Gynaecol Res.

1980;55:12–16. 2009;35:819–823.

5. Coad SL, Dahlgren LS, Hutcheon JA. Risks and consequences of 22. Kaya B, Tüten A, Çelik H, et al. Non-invasive management of

puerperal uterine inversion in the United States, 2004 through acute recurrent puerperal uterine inversion with Bakri postpartum

2013. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:377.e1–377.e6. balloon. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:695–696.

6. Rana K, Patel P. Complete uterine inversion an unusual yet crucial 23. Soleymani M, Pilsniak A, Reginald P. Recurrent uterine inversion:

sonographic diagnosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:1719–1722. a novel treatment approach using SOS Bakri balloon. BJOG.

7. Adesiyun A. Septic postpartum uterine inversion. Singapore Med 2009;116:999–1001.

J. 2007;48:943–945. 24. Haeri S, Rais S, Monks B. Intrauterine tamponade balloon use in

8. Opaneye AA. Acute uterine inversion: a report of two cases. Int J the treatment of uterine inversion. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:

Gynaecol Obstet. 1980;18:251–254. bcr2014206705.

9. Brar HS, Greenspoon JS, Platt LD, et al. Acute puerperal uterine 25. Thiam M, Niang MM, Gueye L, et al. Puerperal uterine inversion

inversion. New approaches to management. J Reprod Med. managed by the uterine balloon tamponade. Pan Afr Med J.

1989;34:173–177. 2015;22:331.

10. Das P. Inversion of the uterus. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1940;47: 525–547. 26. Keriakos R, Chaudhuri SR. Managing major postpartum haemor-

11. Rudloff U, Joels LA, Marshall N. Inversion of the uterus at caesar- rhage following acute uterine inversion with Rusch balloon cath-

ean section. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2004;296:224–226. eter. Case Rep Crit Care. 2011;2011:541479.

12. Mihmanli V, Kilic F, Pul S, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 27. Parikshit D, Niranjan M, Nandanwar YS. Pregnancy outcome

of Non-Puerperal Complete Uterine Inversion. Iran J Radiol. after operative correction of puerperal uterine inversion. Arch

2015;12:e9878. Gynecol Obstet. 2004;296:214–216.

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Вам также может понравиться

- EDiR Notebook (For European Diploma in Radiology)Документ250 страницEDiR Notebook (For European Diploma in Radiology)Parthiban Bala100% (4)

- NCRP Report No. 177 PDFДокумент245 страницNCRP Report No. 177 PDFVivien FerradaОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Inggris PDFДокумент4 страницыJurnal Inggris PDFTom PrasОценок пока нет

- Oncology Nursing Care Plans PDFДокумент444 страницыOncology Nursing Care Plans PDFLuluk Nafisah100% (4)

- SHDJDJДокумент5 страницSHDJDJkhusnulОценок пока нет

- Cme Reviewarticle: Tocolysis: A Review of The LiteratureДокумент6 страницCme Reviewarticle: Tocolysis: A Review of The Literatureeset5Оценок пока нет

- An Uncommon Cause of Antepartum Haemorrhage: A Case Study: January 2019Документ7 страницAn Uncommon Cause of Antepartum Haemorrhage: A Case Study: January 2019SriMathi Kasi Malini ArmugamОценок пока нет

- Enerzad - L Arginine & Endometrium ThicknessДокумент12 страницEnerzad - L Arginine & Endometrium ThicknessOs MohamedОценок пока нет

- Shinohara 2020Документ5 страницShinohara 2020Huệ MinhОценок пока нет

- Myers 2015Документ13 страницMyers 2015ERIKA ANDREINA RAMADANIОценок пока нет

- Total and Acute Uterine Inversion After Delivery: A Case ReportДокумент5 страницTotal and Acute Uterine Inversion After Delivery: A Case ReportMuhammad AzkaОценок пока нет

- Matsuzaki 2018Документ28 страницMatsuzaki 2018terry mutiaОценок пока нет

- Maternal and FДокумент3 страницыMaternal and FNununkОценок пока нет

- Motherhood After Breast Cancer: Searching For La Dolce Vita - Azim Et Al., 2011Документ12 страницMotherhood After Breast Cancer: Searching For La Dolce Vita - Azim Et Al., 2011CSОценок пока нет

- The International Academy of Cytology Yokohama System For Reporting Breast Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy CytopathologyДокумент17 страницThe International Academy of Cytology Yokohama System For Reporting Breast Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy Cytopathologyunimo.prgОценок пока нет

- Gynecologic Cancer in PregnancyДокумент11 страницGynecologic Cancer in PregnancyCarlos GabrielОценок пока нет

- Reviewon Cervical CancerДокумент7 страницReviewon Cervical CancerAlmas TОценок пока нет

- Reccmiss CzEvalTrtДокумент13 страницReccmiss CzEvalTrtGian Alodia RisamasuОценок пока нет

- Ijgc 2020 001996Документ8 страницIjgc 2020 001996Sulaeman Andrianto SusiloОценок пока нет

- Dafpus Abortus 1Документ13 страницDafpus Abortus 1ShintungОценок пока нет

- Kista OvariumДокумент8 страницKista OvariumIntan PermataОценок пока нет

- Jurnal FertilitasДокумент2 страницыJurnal FertilitasPutri MahacakriОценок пока нет

- Vesicovaginal FistulaДокумент54 страницыVesicovaginal FistuladanielОценок пока нет

- Amniotomy For Shortening Spontaneous Labour: Cochrane UpdateДокумент2 страницыAmniotomy For Shortening Spontaneous Labour: Cochrane UpdatesuderiОценок пока нет

- Breast Carcinoma in Axillary Tail of Spence: A Rare Case ReportДокумент4 страницыBreast Carcinoma in Axillary Tail of Spence: A Rare Case Reportrajesh domakuntiОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S2468900918300161 MainДокумент4 страницы1 s2.0 S2468900918300161 MainayissiОценок пока нет

- New Insights Into Mechanisms Behind MiscarriageДокумент11 страницNew Insights Into Mechanisms Behind MiscarriageBiansay AguñasОценок пока нет

- Practice Bulletin: Management of Adnexal MassesДокумент14 страницPractice Bulletin: Management of Adnexal MassesDasha VeeОценок пока нет

- Resuscitative HysterotomyДокумент5 страницResuscitative HysterotomySunil DasanОценок пока нет

- Chapter 018Документ12 страницChapter 018Need Help Call NowОценок пока нет

- No. 223-Content of A Complete Routine Second Trimester Obstetrical Ultrasound Examination and ReportДокумент6 страницNo. 223-Content of A Complete Routine Second Trimester Obstetrical Ultrasound Examination and ReportYolpa Figueroa PorrasОценок пока нет

- Sadeq Saad Abd El Moghny, Ahmed Kaid Allow, Belqees Ahmed and Bracamonte MaryamДокумент7 страницSadeq Saad Abd El Moghny, Ahmed Kaid Allow, Belqees Ahmed and Bracamonte Maryamgamal attamОценок пока нет

- European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive BiologyДокумент5 страницEuropean Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive BiologyMariana González DíazОценок пока нет

- European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive BiologyДокумент5 страницEuropean Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive BiologyMariana González DíazОценок пока нет

- Endometrial Hyperplasia and The Risk of Progression To CarcinomaДокумент6 страницEndometrial Hyperplasia and The Risk of Progression To Carcinomaimmanuel dioОценок пока нет

- Breast Cancer Genetic Counseling A Surgeons PerspДокумент7 страницBreast Cancer Genetic Counseling A Surgeons PerspAbdul HaiОценок пока нет

- Intl J Gynecology Obste - 2023 - Henry - FIGO Statement Fertility PreservationДокумент5 страницIntl J Gynecology Obste - 2023 - Henry - FIGO Statement Fertility Preservationcesarillo85Оценок пока нет

- Postoperative Outcomes of Breast Reconstruction AfДокумент6 страницPostoperative Outcomes of Breast Reconstruction AfDiana AlexandraОценок пока нет

- SDP Vs AFIДокумент5 страницSDP Vs AFINuzma AnbiaОценок пока нет

- Ectopic Pregnancy: A ReviewДокумент13 страницEctopic Pregnancy: A ReviewDinorah MarcelaОценок пока нет

- Expectatant Management of Cesarean Scar Ectopic PregnancyДокумент5 страницExpectatant Management of Cesarean Scar Ectopic PregnancyEricОценок пока нет

- Manejo Ca Cervical BMJДокумент5 страницManejo Ca Cervical BMJNathalia M.Оценок пока нет

- Metanalisis Carbetocina Vs OxiДокумент7 страницMetanalisis Carbetocina Vs OxiSergio ZhinaОценок пока нет

- To Salvage (Routinely) or Not To Salvage: That Is The QuestionДокумент4 страницыTo Salvage (Routinely) or Not To Salvage: That Is The QuestionEmman AmborОценок пока нет

- Examining Indicators of Early Menopause FollowingДокумент11 страницExamining Indicators of Early Menopause FollowingDanielle VОценок пока нет

- Documento PDFДокумент6 страницDocumento PDFJose Miguel CastellonОценок пока нет

- Study of Cases of Rupture Uterus in A Tertiary InsДокумент6 страницStudy of Cases of Rupture Uterus in A Tertiary InsErena HairunisaОценок пока нет

- Icu MaternalДокумент9 страницIcu Maternalobgynunand2012Оценок пока нет

- Congenital and Acquired Malformations in Vulva and Vagina - Pediatric AgeДокумент2 страницыCongenital and Acquired Malformations in Vulva and Vagina - Pediatric AgePramedicaPerdanaPutraОценок пока нет

- Anestesia FetalДокумент13 страницAnestesia FetalPauPatiñoОценок пока нет

- Safety of The Balloon Catheter For Cervical Ripening in Outpatient Care Complicatios M DiederenДокумент10 страницSafety of The Balloon Catheter For Cervical Ripening in Outpatient Care Complicatios M DiederenMitsury Jacqueline Flores C.Оценок пока нет

- Alsamaraee 2019Документ7 страницAlsamaraee 2019Dinorah MarcelaОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S0093691X20303538 MainДокумент11 страниц1 s2.0 S0093691X20303538 MainRo BellingeriОценок пока нет

- IndianJAnaesth629717-5020005 012340 PDFДокумент7 страницIndianJAnaesth629717-5020005 012340 PDFIsha ParveenОценок пока нет

- Kista Terpluntir 222Документ5 страницKista Terpluntir 222FatimahОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Internasional 1Документ5 страницJurnal Internasional 1Ifni AngraeniОценок пока нет

- Gynaecomastia: BMJ Clinical Research September 2016Документ10 страницGynaecomastia: BMJ Clinical Research September 2016kintan utamiОценок пока нет

- Non Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer JUДокумент9 страницNon Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer JUita maghfirah IlhamjayaОценок пока нет

- Overview of EP Diagnosis Management and Innovation - 231218 - 072807Документ13 страницOverview of EP Diagnosis Management and Innovation - 231218 - 072807Putu Gede WidyatamaОценок пока нет

- JPM 12 01098 v2Документ11 страницJPM 12 01098 v2Rizki FebriyaniОценок пока нет

- Tumor Staging of Endocervical Adenocarcinoma .8Документ10 страницTumor Staging of Endocervical Adenocarcinoma .8elisasitohangОценок пока нет

- Cancer Treatment and the Ovary: Clinical and Laboratory Analysis of Ovarian ToxicityОт EverandCancer Treatment and the Ovary: Clinical and Laboratory Analysis of Ovarian ToxicityОценок пока нет

- No. Nama MR Jenis Kelamin LK PRДокумент8 страницNo. Nama MR Jenis Kelamin LK PRMochHabibEl-HuseinyОценок пока нет

- Flat Medical Icon Medical History On A White Background PowerPoint Templates WidescreenДокумент3 страницыFlat Medical Icon Medical History On A White Background PowerPoint Templates WidescreenMochHabibEl-HuseinyОценок пока нет

- Usui 2017Документ6 страницUsui 2017MochHabibEl-HuseinyОценок пока нет

- The Normal Frontal Chest Radiograph The Normal Lateral Chest RadiographДокумент2 страницыThe Normal Frontal Chest Radiograph The Normal Lateral Chest RadiographMochHabibEl-HuseinyОценок пока нет

- New Doc 2019-01-03 12.18.38Документ4 страницыNew Doc 2019-01-03 12.18.38MochHabibEl-HuseinyОценок пока нет

- Forensic Science International: Minna Joki-Erkkilä, Juha Rainio, Heini Huhtala, Aki Salonen, Pekka J. KarhunenДокумент7 страницForensic Science International: Minna Joki-Erkkilä, Juha Rainio, Heini Huhtala, Aki Salonen, Pekka J. KarhunenMochHabibEl-HuseinyОценок пока нет

- New Doc 2018-11-13 10.36.03Документ12 страницNew Doc 2018-11-13 10.36.03MochHabibEl-HuseinyОценок пока нет

- Modul PODДокумент13 страницModul PODMochHabibEl-HuseinyОценок пока нет

- New Doc 2018-11-28 21.56.52Документ5 страницNew Doc 2018-11-28 21.56.52MochHabibEl-HuseinyОценок пока нет

- Fisiologi OlahragaДокумент128 страницFisiologi OlahragaFanny Chungafarmodjo100% (1)

- New Doc 2018-12-09 08.16.21Документ3 страницыNew Doc 2018-12-09 08.16.21MochHabibEl-HuseinyОценок пока нет

- Proposal MABITДокумент6 страницProposal MABITMochHabibEl-HuseinyОценок пока нет

- Temephos in Drinking-Water: Use For Vector Control in Drinking-Water Sources and ContainersДокумент14 страницTemephos in Drinking-Water: Use For Vector Control in Drinking-Water Sources and ContainersMochHabibEl-HuseinyОценок пока нет

- Temephos WHOДокумент24 страницыTemephos WHOMochHabibEl-Huseiny0% (1)

- Charpak: New Evidences On The Kangaroo Mother Care MethodДокумент51 страницаCharpak: New Evidences On The Kangaroo Mother Care MethodNewborn2013Оценок пока нет

- The British Journal of Cardiology May-June 2010, Volume 17 Supplement 2Документ16 страницThe British Journal of Cardiology May-June 2010, Volume 17 Supplement 2mbarrales_4Оценок пока нет

- Borax - The Inexpensive Detox, Arthritis, Osteoporosis and Mycoplasma CureДокумент14 страницBorax - The Inexpensive Detox, Arthritis, Osteoporosis and Mycoplasma Curebammer189% (9)

- Assessment of ADHD and ComorbidityДокумент3 страницыAssessment of ADHD and ComorbidityFelipe CafureОценок пока нет

- Electroconvulsive TherapyДокумент2 страницыElectroconvulsive TherapyRiz BorbonОценок пока нет

- Drug InteractionДокумент151 страницаDrug Interactionapi-3724213100% (1)

- Grade 9 Biology - Lesson Note April 8,2020Документ10 страницGrade 9 Biology - Lesson Note April 8,2020micahxОценок пока нет

- MEAL (Psychiatric Nursing 2)Документ4 страницыMEAL (Psychiatric Nursing 2)Yucef Bahian-AbangОценок пока нет

- One Lung Ventilation: General Principles - UpToDateДокумент26 страницOne Lung Ventilation: General Principles - UpToDateAna Belén Artero CastañoОценок пока нет

- Jemds Title PДокумент1 страницаJemds Title PKriti KumariОценок пока нет

- PSM LMRP 2019Документ25 страницPSM LMRP 2019skОценок пока нет

- DAFTAR PUSTAKA HydrocephalusДокумент2 страницыDAFTAR PUSTAKA HydrocephalusRahma darisОценок пока нет

- Final ThesisДокумент47 страницFinal ThesisMohammed AhmedОценок пока нет

- Approach To Delay PubertyДокумент33 страницыApproach To Delay PubertyRaja Iqbal Mulya HarahapОценок пока нет

- National Pharmaceutical Council 2003 Member Forum HighlightsДокумент7 страницNational Pharmaceutical Council 2003 Member Forum HighlightsNational Pharmaceutical CouncilОценок пока нет

- Fdar Cabg 3nesurgicalДокумент5 страницFdar Cabg 3nesurgicalMary Margareth GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Vein Artery Capillary: Thin Wall Wide Lumen Valve Thick Wall Narrow Lumen One Cell Thick WallДокумент1 страницаVein Artery Capillary: Thin Wall Wide Lumen Valve Thick Wall Narrow Lumen One Cell Thick WallHuiso RohОценок пока нет

- State of The ArtДокумент3 страницыState of The ArtArne HeyerickОценок пока нет

- The Body Nutrition PortionДокумент35 страницThe Body Nutrition PortionHerditya putri rahmaОценок пока нет

- Effects and Costs of Real-Time Cardiac Telerehabilitation - Randomised Controlled Non - Inferiority TrialДокумент8 страницEffects and Costs of Real-Time Cardiac Telerehabilitation - Randomised Controlled Non - Inferiority TrialarwitarahayuОценок пока нет

- Osce, BaselДокумент302 страницыOsce, Baselbpjavi78% (9)

- Mckenzie Exercises: Exercise OneДокумент6 страницMckenzie Exercises: Exercise OneJansen ChОценок пока нет

- Perinatology Clinics 2008, Vol.35, Issues 4, Neuroprotection in The NewbornДокумент210 страницPerinatology Clinics 2008, Vol.35, Issues 4, Neuroprotection in The NewbornJhonny MarquezОценок пока нет

- Idiopathic Linear Leukoplakia of Gingiva: A Rare Case ReportДокумент3 страницыIdiopathic Linear Leukoplakia of Gingiva: A Rare Case ReportDeasireeОценок пока нет

- Psychiatry 101Документ17 страницPsychiatry 101Vaso Talakvadze0% (1)

- Facial TicsДокумент2 страницыFacial TicsNdhe PoetryОценок пока нет

- Nhis Drug Price List Final (2013 Ed)Документ32 страницыNhis Drug Price List Final (2013 Ed)holuwadamilare935Оценок пока нет

- 03 Cutaneous MycosesДокумент30 страниц03 Cutaneous MycosesFelix AyornuОценок пока нет