Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Limping Child

Загружено:

lybzia1Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Limping Child

Загружено:

lybzia1Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Limping Child: Evaluation and Diagnosis

John M. Flynn, MD, and Roger F. Widmann, MD

Abstract

A limp is a common reason for a child to present to the orthopaedist. Because of cally between 12 and 16 months of

the long list of potential diagnoses, some of which demand urgent treatment, an age), they have a short stride

organized approach to evaluation is required. With an understanding of normal length, a relatively fast cadence

and abnormal gait, a directed history and physical examination, and the devel- and slow velocity, and a widened

opment of a differential diagnosis based on the type of limp, the patient’s age, base of support in double stance.

and the anatomic site that is most likely affected, the orthopaedist can take a Their hips, knees, and ankles move

selective approach to diagnostic testing. Laboratory tests are indicated when through a small arc of motion. 2

infection, inflammatory arthritis, or a malignant condition is in the differential Until 30 to 36 months of age, chil-

diagnosis. The C-reactive protein assay is the most sensitive early test for mus- dren have neither the balance nor

culoskeletal infections; an abnormal value rapidly returns to normal with effec- the abductor strength to maintain

tive treatment. Imaging should begin with plain radiography. Ultra- single-limb stance for very long.

sonography is particularly valuable in assessing the irritable hip and guiding By 7 years of age, children exhibit a

aspiration, if necessary. mature gait.2

J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001;9:89-98 The mature gait cycle is com-

posed of the stance phase (initial

contact, loading response, mid-

stance, terminal stance, preswing)

A limp is a common reason for a child sient synovitis) to conditions in and the swing phase, during which

to present to the orthopaedist, often which early diagnosis may be life- the limb is advanced in space to

after first being seen by a primary- saving (e.g., acute leukemia).1 The position the foot for the next heel-

care physician or in an emergency long differential diagnosis (Tables 1 strike. The abductors stabilize the

department. Most parents are keen and 2) may seem daunting, particu- pelvis during stance phase, pre-

observers; they are quick to detect larly when the site of origin is un- venting significant side-to-side

even subtle gait abnormalities and known. However, after obtaining a motion as the opposite limb swings

generally will not wait long to have thorough history and performing a

a limp evaluated. The orthopaedist careful physical examination, the site

is expected to recognize the gait of origin can often be localized and

Dr. Flynn is Assistant Professor of Orthopaedic

abnormality, determine the proba- the differential diagnosis narrowed, Surgery, Unviersity of Pennsylvania School of

ble site of origin, and then develop a thus permitting a well-organized Medicine, Philadelphia; and Attending

good working diagnosis before approach to obtaining additional Surgeon, Division of Orthopaedic Surgery,

ordering selective diagnostic tests. data with selective diagnostic tests. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr.

Widmann is Assistant Professor of Orthopaedic

These tests should provide the data Appropriate treatment can then be

Surgery, Weill Medical College of Cornell

for confirming the diagnosis and instituted. University, New York, NY; and Assistant

developing a treatment plan while Attending Surgeon, Hospital for Special

decreasing costs to the health-care Surgery, New York.

system, as well as minimizing pain Normal Gait

and anxiety for the child and parent. Reprint requests: Dr. Flynn, Division of

Orthopaedic Surgery, Children’s Hospital of

Pain, weakness, and mechanical Normal gait is a smooth, rhythmic,

Philadelphia, 34th and Civic Center Blvd,

factors are the primary causes of mechanical process that advances Philadelphia, PA 19104-4399.

limp in children. The etiology of a the center of gravity with a mini-

limp ranges from benign, self-limited mum expenditure of energy. Many Copyright 2001 by the American Academy of

conditions that call for only a diag- aspects of gait change with age. 2 Orthopaedic Surgeons.

nosis and reassurance (e.g., tran- When children begin to walk (typi-

Vol 9, No 2, March/April 2001 89

The Limping Child

Table 1

Differential Diagnosis of Antalgic Gait

<4 yr 4 to 10 yr >10 yr

Toddler’s fracture (tibia or foot) Fracture (especially physeal) Stress fracture (femur, tibia, foot, pars

Osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, Osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, diskitis intra-articularis)

diskitis Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease Osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, diskitis

Arthritis (juvenile rheumatoid Transient synovitis Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

arthritis, Lyme disease) Osteochondritis dissecans (knee or ankle) Osgood-Schlatter disease or Sindig-

Discoid lateral meniscus Discoid lateral meniscus Larsen-Johanssen syndrome

Foreign body in the foot Sever’s apophysitis Osteochondritis dissecans (knee or

Benign or malignant tumor Accessory tarsal navicular ankle)

Foreign body in the foot Chondromalacia patellae

Arthritis (juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, Arthritis (Lyme disease, gonococcal)

Lyme disease) Accessory tarsal navicular

Benign or malignant tumor Tarsal coalition

Benign or malignant tumor

through. During normal walking Abnormal Gait lumbar spine, as demonstrated

motion, one foot is always on the when bending to pick up objects off

ground. The kinematics of normal Normal gait can be altered by pain, the floor.5 Another variant of the

gait has been studied in detail,2,3 a mechanical problem, or a neuro- antalgic gait is the complete refusal

establishing normal ranges of joint muscular problem. A child will to walk. This pattern is seen most

motion during different phases of adopt an antalgic gait in an effort to often in toddlers and may indicate

the gait cycle. The ankle dorsiflexes prevent pain in the affected limb. a condition causing pain that can-

at heel-strike, then plantar-flexes to The single-limb-support phase of not be avoided by any of the possi-

foot-flat, and then dorsiflexes again stance is shortened on the painful ble gait alterations.

as the tibia moves forward. The extremity, as is the stride length of Circumduction—excessive hip

knee is flexed at heel-strike, extends the normal opposite limb (to get abduction, pelvic rotation, and hik-

until toe-off, and then flexes during back to bearing weight on the well ing—functionally shortens a limb,

swing, allowing clearance of the leg as quickly as possible). A vari- thus enhancing foot clearance dur-

foot as it positions for the next heel- ant of the classic antalgic gait is the ing swing when there is joint stiff-

strike. The hip follows a similar “cautious” gait of a child with back ness, particularly in the ankle. 6

pattern, with slight flexion at heel- pain.4 For example, a child with Children with a significant limb-

strike, extension through stance, diskitis will lose the normal rhyth- length inequality may “vault” with

and then flexion in swing. mic flexion and extension of the the short leg (or toe-walk) to clear

Table 2

Differential Diagnosis of a Nonantalgic Limp

Circumduction Gait/

Equinus Gait (Toe-Walking) Trendelenburg Gait Vaulting Gait Steppage Gait

Idiopathic tight Achilles tendon Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease Limb-length discrepancy Cerebral palsy

Clubfoot (residual or untreated) Developmental dysplasia of the hip Cerebral palsy Myelodysplasia

Cerebral palsy Slipped capital femoral epiphysis Any cause of ankle or Charcot-Marie-Tooth

Limb-length discrepancy Muscular dystrophy knee stiffness disease

Hemiplegic cerebral palsy Friedreich’s ataxia

90 Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

John M. Flynn, MD, and Roger F. Widmann, MD

the long leg, rather than circumduct and some children should be ques- tory joint disorders.8 Pain after activ-

it. An equinus gait (toe-walking) tioned privately, as they may pro- ity may suggest an overuse injury,

occurs when ankle dorsiflexion is vide important details regarding such as a stress fracture, or an inter-

limited. This may result from gas- exposure to sexually transmitted nal articular derangement, such as

trocnemius-soleus spasticity, short- diseases, such as gonococcal infec- an osteochondral lesion, a meniscal

ening of the Achilles tendon, or tion, which may not be obtained in tear, or an anterior cruciate ligament

both. Thus, stance phase will be the presence of parents.7 Once the tear. Night pain that wakes a child

initiated with toe-strike rather than parent and patient have had an from sleep may represent benign

heel-strike. opportunity to describe the pain “growing pains,” but the concern is

Several abnormal gait patterns and/or limp in their own terms, the that it may derive from osteoid oste-

result from muscle weakness or a physician is best prepared to com- oma or a malignant condition.

neurologic abnormality. A Trendel- plete the history. Pain relief with nonsteroidal anti-

enburg gait results from altered The history should focus on the inflammatory medications may be

hip mechanics, particularly abduc- character of the limp: the presence characteristic of osteoid osteoma but

tor weakness. During stance on the or absence of pain or other localiz- is not diagnostic. Referred pain must

involved side, the contralateral side ing symptoms, the frequency and also be considered, particularly thigh

of the pelvis drops. To preserve duration of symptoms, and the or medial knee pain referred from

balance, the child may lean the mechanism of injury, when appro- painful conditions of the hip (e.g.,

trunk toward the affected side. A priate. A history of ceasing athletic slipped capital femoral epiphysis).

variation of the Trendelenburg gait participation or social play with Buttock or lateral thigh pain may be

is the waddling gait of a child with friends should raise concern.4 The referred from the back. Pain in multi-

bilateral hip dislocation. A “step- absence of pain suggests either neu- ple joints suggests an arthritic process.

page gait” develops when the ankle romuscular or metabolic disease or A past medical history including

dorsiflexors are weak (e.g., as in a congenital or developmental ab- recent trauma or exposure to infec-

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease). To normality, such as hip dysplasia or tious diseases and use of antibiotics

compensate for the weakness, the limb-length discrepancy. In a tod- is helpful in diagnosis. Recent vari-

child increases knee flexion in the dler, the absence of pain complaints cella infection may lower systemic

swing phase to clear the foot. The may not be particularly helpful, immunity, rendering the child sus-

foot will slap to the ground because and the physical examination takes ceptible to opportunistic bone or

the ankle dorsiflexors are unable to on greater importance. joint infections.9 Failure to achieve

decelerate the foot between heel- The pattern, onset, and duration appropriate developmental mile-

strike and foot-flat. An unsteady of pain may suggest the origin. 4 stones or, more ominously, deterio-

gait may result from conditions that Acute onset of severe pain over a ration of motor ability warrants fur-

affect balance, such as Friedreich’s few days focuses the evaluation on ther neuromuscular or metabolic

ataxia. Careful initial analysis of trauma, infection, or malignancy, evaluation. The review of systems

the gait can enhance the specificity whereas gradual worsening over should seek a history of recent fever,

of the remainder of the physical months suggests inflammatory or weight loss, or malaise suggestive of

examination and facilitate localiza- mechanical symptoms.8 It is helpful infection or malignancy. A history

tion of the origin of the limp. to characterize the quality of the of prior medical evaluation for the

pain as constant, intermittent, or same problem should be sought, and

transient. Constant pain is of partic- the pertinent records should be ob-

History ular concern, suggesting an intra- tained when possible. A complete

medullary process, such as expand- history should include questioning

An accurate history may be difficult ing tumor or infection. A history of about the family history of neuro-

to obtain from a young child, and trauma is readily established in most muscular disease, metabolic disease,

some or all of the history must be ob- circumstances, with some notable inflammatory arthritis, or infectious

tained from the parents or primary exceptions: pathologic fracture and disease exposure.

caregivers. A brief discussion with child abuse.

the child, followed by a parental It is important to characterize the

description of pain complaints and timing of pain (e.g., morning pain, Physical Examination

changes in gait pattern, is invalu- pain after activity, or pain that wakes

able in guiding the subsequent the child from sleep). Morning pain The physical examination of the

physician-directed evaluation. In or pain and stiffness after inactivity limping child has three essential

certain circumstances, adolescents are more characteristic of inflamma- components: the gait exam, the

Vol 9, No 2, March/April 2001 91

The Limping Child

standing/floor exam, and the table- A unilateral shortened stance phase If muscular dystrophy is a possi-

top exam. The child should be is characteristic of an antalgic gait. bility, a Gower test is performed by

dressed in as little clothing as is prac- The range of motion of each joint having the child sit on the floor and

tical; gym shorts and bare feet are should also be evaluated. Limited then rise quickly, observing to see if

ideal. Much can be missed watching ankle dorsiflexion is seen in chil- he uses his hands to substitute for

a small child walk in an oversized dren with a short Achilles tendon weak hip extensor muscles. Repeti-

gown that extends to the floor. or a spastic gastrocnemius-soleus. tive single-leg heel raises and toe

At the knee, motion should be ob- raises can be utilized to accentuate

Gait Examination served through several gait cycles. subtle weakness in the foot plantar-

The examination area should Contracture or spasticity in the flexors or dorsiflexors.

offer sufficient space to see multiple quadriceps or hamstrings or intra-

gait cycles. It is important not to be articular derangement will limit Tabletop Examination

fooled by an artificial “doctor walk”; knee motion. Any frontal-plane ab- With the child on the examining

the best chance to see the true limp normalities should be noted as well table, one should thoroughly in-

is by observing gait when the child (e.g., a varus thrust of the proximal spect for asymmetry, deformity,

does not know she is being watched, tibia in Blount’s disease). Hip mo- erythema, rashes, and swelling.

such as when the child is walking to tion may be abnormal, exhibiting Puncture wounds or foreign bodies

the examination room.10 Running circumduction, persistent flexion, should be sought on the plantar

may accentuate the limp or abnor- or excessive pelvic or trunk motion. surface of the foot in walkers and

mal gait. Subtle weakness or the Upper-extremity posturing as well on the anterior aspect of the knee in

upper-extremity posturing of cere- as difficulty with balance and coor- crawlers. The resting position of

bral palsy might not be seen until dination may suggest a neurovas- the limb should be noted; for exam-

the child runs. Shoes may provide cular origin of the limp. ple, a child with septic arthritis of

valuable clues to gait problems; for the hip will hold the hip flexed and

example, a child having trouble Standing/Floor Examination externally rotated. Note also any

clearing his foot in swing phase may After the history and vital signs muscle hypertrophy (e.g., calf hy-

have excessive toe wear. have been taken and the physician pertrophy in muscular dystrophy)

It is best to adopt a systematic has thoroughly studied the child’s or atrophy (e.g., global unilateral

approach to the gait examination, gait, there are several tests to con- atrophy in hemiplegia or quadri-

working from the ground up and sider before the tabletop examina- ceps atrophy in a child with a pain-

watching each limb segment and tion. The spine should be examined ful hip or knee).

joint through several gait cycles. with the child standing, taking care Palpation of the lower extremity

Trying to simultaneously analyze to note balance in the coronal and to find the point of maximum ten-

every facet of gait is difficult for sagittal planes, scoliosis, lumbo- derness is often the most valuable

even the most experienced clinician, sacral step-off, pelvic obliquity, and part of the physical examination of a

considering that a typical toddler any cutaneous findings (e.g., café- limping child. Knowing the exact

takes 180 steps per minute. Note au-lait spots, hairy patches, or sacral site of pain dramatically limits the

how the foot strikes the floor—is dimples). On the forward bend, the differential diagnosis and may elim-

there heel-strike, foot-flat, or toe- examiner should note a thoracic or inate the need for a bone scan or

strike? A child may walk on the lumbar prominence due to scoliosis. other diagnostic test (Fig. 1). Every

medial or lateral border of the foot The Trendelenburg test is per- joint of the lower extremity should

to protect a sore bone or the site of a formed by having the child stand be taken through its range of mo-

puncture wound or foreign body. on the affected leg with the knee tion, noting pain, contractures, or

Abnormal limb rotation may be flexed and the hip extended. The muscle spasticity. The patellofemo-

observed. Metatarsus adductus, child may need to rest his hands ral joint, a common source of pain

internal tibial torsion, or femoral against the wall for balance. If the in adolescents, should be tested for

anteversion will result in an internal Trendelenburg test is performed signs of apprehension or pain with

foot-progression angle. An adoles- with hip flexion, the hip flexors can patellar compression during flexion

cent with a slipped capital femoral elevate the pelvis and mask a mild and extension. The sacroiliac joint is

epiphysis or a young child with an deficiency of the gluteus medius.4 tested by direct percussion posteri-

occult fracture may walk with an It may take 20 seconds or more of orly and by stressing the joint with

external foot-progression angle. continuous testing on the affected the hip positioned in flexion, abduc-

The next feature to consider is limb before abductor weakness tion, and external rotation (FABER

the symmetry of the stance phase. causes the opposite pelvis to drop. test). The rotational profile should

92 Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

John M. Flynn, MD, and Roger F. Widmann, MD

tional oblique views may reveal

more subtle osseous changes, such

as a minimally displaced tibial frac-

ture (toddler’s fracture) or the peri-

osteal elevation of a stress fracture.

In children who present with a limp

or refusal to bear weight but are too

young to localize pain, plain radio-

graphs of the entire lower extremity

should be obtained (Fig. 2).

Plain radiographs are not particu-

larly helpful in identifying early

bone or joint infections. The early ra-

diographic findings of acute hema-

togenous osteomyelitis include a nor-

mal osseous appearance with subtle

displacement and swelling of the soft

tissues.13 Comparison views may

depict subtle soft-tissue swelling, but

radiographic sensitivity for the early

changes of osteomyelitis is less than

50%.14 The radiographic appearance

of early soft-tissue changes due to

septic arthritis is difficult to interpret

A B and unreliable.15 Early bone or joint

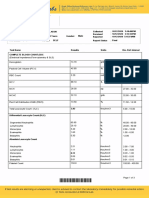

Figure 1 A, A healthy limping toddler presented with reproducible tenderness to palpa-

changes are not typically seen radio-

tion over the midportion of the tibia. Rotational stress to the tibia was also painful. graphically until 10 to 12 days after

Although the radiographs were read as normal, an occult fracture was suspected. B, At 4 the onset of bone or joint infection,13

weeks, radiographs showed periosteal elevation along the medial cortex of the tibia

(arrows), confirming the clinical suspicion of a toddler’s fracture. The child’s symptoms

and the presence of these changes

resolved after 4 weeks in a cast. suggests a significant delay in diag-

nosis.

The triphasic technetium-99m

bone scan is an excellent test for

be documented in children with in- limp, plain radiography should evaluating a limping child when

toeing or out-toeing.11 Appropriate always be performed first, because the history and physical examina-

neurologic testing should also be radiographs are inexpensive, can be tion fail to localize the anatomic site

performed. easily obtained at any hour, and are of pathologic changes (Fig. 3). Bone

Limb lengths should be assessed. both sensitive and specific for a scanning has been demonstrated to

If an inequality is noted, the differ- wide variety of disorders.12 In chil- be superior to the other standard

ence is most accurately determined dren who can localize tenderness, screening tests for infection (tem-

by leveling the pelvis with blocks initial plain radiographs should perature, white blood cell [WBC]

under the short leg. Although a sig- include orthogonal images of the count, erythrocyte sedimentation

nificant limb-length inequality may affected limb that visualize the joint rate [ESR], and plain radiography)

itself alter gait, it also suggests other both above and below the point of in the limping toddler.14 The tech-

potential causes of limping, such as maximum tenderness. A third ob- netium accumulates at the site of in-

hemiplegia and developmental dis- lique view is included when imag- creased blood flow and osteoblastic

location of the hip. ing the ankle or foot if an area of activity in osteomyelitis, stress frac-

suspected pathologic change may tures, occult fractures, neoplasm,

be obscured by bone overlap, mini- and metastases. In suspected early

Radiographic Evaluation mal displacement of fracture frag- bone infection, bone scans have high

ments, or minimal physeal widen- sensitivity (84% to 100%) and speci-

Although the various imaging ing. 12 If the patient can localize ficity (70% to 96%).12,14,16

modalities may each have a role in pain but the initial radiographs of Although the diagnosis of many

the assessment of the child with a the long bones are negative, addi- long-bone infections can be made

Vol 9, No 2, March/April 2001 93

The Limping Child

in clinical practice.17 Other advan-

tages of bone scanning over cross-

sectional imaging modalities include

decreased expense, less need for se-

dation, and the ability to image the

whole body.

Limitations of bone scintigraphy

include difficulty in distinguishing

between bone infarct and osteomy-

elitis in hemoglobinopathies and the

occurrence of false-negative bone

scans in cases of Langerhans cell his-

tiocytosis and some other aggressive

tumors in children.17 Bone scanning

has low sensitivity for septic arthri-

tis, especially when there is adjacent

osteomyelitis, and is therefore not

indicated in this circumstance.

Leukemia may result in increased,

decreased, or no change in tech-

A B netium uptake.14 A “cold” scan (i.e.,

one showing low uptake) in the set-

Figure 2 A, Anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the hips and pelvis of a 2-year-old girl

with a 2-week history of limping, fever, malaise, and difficulty sleeping through the night.

ting of suspected osteomyelitis is

Periosteal changes (arrow) were noted in the right femur. B, A full-length AP radiograph not necessarily negative; instead, it

of the femur demonstrates the extent of periosteal elevation and geographic medullary may represent bone rendered avas-

canal erosion of the lesion, which on biopsy proved to be eosinophilic granuloma.

cular due to a subperiosteal or end-

osteal abscess. A study of cold bone

scans in pediatric patients with

without scintigraphy, bone scans Prior bone drilling and periosteal osteomyelitis revealed that they had

are particularly helpful in localiz- elevation have been demonstrated more severe bone infections requir-

ing sepsis around the pelvis and experimentally to have no effect on ing more aggressive medical and

the spine—areas that are difficult a subsequent bone scan performed surgical treatment compared with

to examine and where soft-tissue within 24 hours,18 and prior aspira- control children with “hot” bone

changes are difficult to identify.17 tion has not interfered with results scans and osteomyelitis.19

A B

Figure 3 A, AP radiograph of an 8-year-old girl who presented with a limp and the sudden, nontraumatic onset of severe left groin and

thigh pain. The film was read as normal. B, The history, physical examination, and plain radiographs did not allow precise localization of

the process. A bone scan showed decreased uptake in the left femoral head, suggesting Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease.

94 Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

John M. Flynn, MD, and Roger F. Widmann, MD

Ultrasonography is a valuable

diagnostic tool in the evaluation of

a limping child with an irritable hip

Femoral

(Fig. 4). Ultrasonography is nonin-

head

vasive, requires no sedation, and is Hip capsule

typically more accessible and less

expensive than other secondary Effusion

radiologic tests. 20 However, if

infection is highly probable, ultra-

sonography should not delay urgent

operative irrigation and debride-

ment. If a hip effusion is noted, the

ultrasonographer can assist with a

guided aspiration and can docu-

ment the intra-articular positioning

of the needle. If ultrasonography is A B

not available, a possibly infected

hip can be aspirated with fluoro- Figure 4 A, A 12-year-old girl presented with an antalgic limp on the right and thigh

scopic guidance. pain. She had pain with internal rotation of the hip, suggesting an effusion. The plain radio-

graph was normal. B, Sonogram of the right hip shows an effusion. Ultrasound-guided

In one series of 44 patients with aspiration yielded purulent fluid. Drainage of the septic hip was performed immediately.

a limp or hip pain and negative

plain radiographs, ultrasonog-

raphy was 100% accurate in pre-

dicting the presence of aspiration- bulging of the iliofemoral ligament, proved to be the most effective im-

documented hip effusion.21 Another so that the joint capsule appears aging modality for bone marrow,

larger prospective study of 111 chil- convex; the normal opposite capsule joints, cartilage, and soft tissues

dren with irritable hips confirmed will be concave.22 (Fig. 6, C). It is extremely useful in

that the plain radiograph was of lit- Ultrasonography can help con- cases of suspected tumor and stress

tle value in the detection of early firm the diagnosis of osteomyelitis fractures.

hip effusion; in that study, there on the basis of characteristic early

was radiographic evidence of effu- and late ultrasonographic clinical

sion in 15% of hips, compared with features.24 Early changes, such as Laboratory Testing

sonographic evidence of effusion in deep soft-tissue swelling, are fol-

71% of hips.15 Furthermore, Zawin lowed by periosteal thickening. Infection, inflammatory disease, and

et al 22 showed that ultrasound- Subperiosteal fluid or abscess is seen malignancy all demand rapid diag-

guided hip aspiration in the radiol- as a later finding 1 to 2 weeks after nosis and treatment, and laboratory

ogy suite decreased the subsequent the onset of symptoms. The main testing may assist both in making

operative time for septic hips by value of ultrasound imaging of the the appropriate diagnosis and in

50%. However, a large prospective extremity in cases of suspected in- monitoring the efficacy of treatment.

study of 500 painful hips in chil- fection is to rule out subperiosteal Laboratory testing is indicated when

dren demonstrated that ultrasound abscess.20 a child presents with an acute non-

cannot effectively differentiate Cross-sectional imaging, includ- traumatic limp and signs and symp-

among sterile, purulent, and hem- ing computed tomography (CT) and toms of fever, malaise, night pain, or

orrhagic effusions.23 The authors of magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, localized complaints. Appropriate

that study concluded that ultra- is rarely necessary as an initial tests include a complete blood cell

sonography of the hip should be study in the evaluation of a limping count with differential and determi-

reserved for select cases in which child. Computed tomography is in- nation of the ESR, the C-reactive

sepsis is suspected. dicated specifically for imaging of protein (CRP) and antinuclear anti-

Ultrasound evaluation of the irri- suspected localized abnormalities of body levels, and the rheumatoid fac-

table hip is performed with the cortical bone (Fig. 5). It may also tor and Lyme titers.

transducer oriented in an oblique confirm the presence of either a cen- In the setting of bone or joint

sagittal plane parallel to the long tral nidus in cases of osteoid osteoma infection, the WBC count is neither

axis of the femoral neck with the hip or the occurrence of a tarsal coalition. sensitive nor specific. Although the

in extension.12 An effusion causes Magnetic resonance imaging has WBC count is elevated in 25% to

Vol 9, No 2, March/April 2001 95

The Limping Child

joints, the hip is the most technically

difficult to aspirate. Sedation and

local anesthesia are helpful, and

aspiration under fluoroscopic guid-

ance with arthrography at the com-

pletion of the procedure is recom-

mended to confirm appropriate

spinal needle placement within the

joint.30 Ultrasound-guided aspira-

tion provides similar confirmation of

needle placement. Culture and cell

counts should be obtained in all

cases. A WBC count greater than

A B 80,000/mm3 with a percentage of

polymorphonuclear cells greater

Figure 5 A, A 10-year-old soccer player presented with a limp and thigh pain of 4 weeks’ than 75% is highly suggestive of

duration. AP radiograph shows a radiodense area in the medial subtrochanteric region. joint sepsis, although early sepsis

B, CT scan obtained to better characterize the sclerotic area shows a pattern typical of a

femoral-neck stress fracture. A biopsy was avoided. The pain and limp resolved after 2 may present with a much lower cell

months of protected weight bearing. count.30

The rheumatoid factor and anti-

nuclear antibody levels are deter-

mined when inflammatory arthritis

31% of children with osteomyeli- of infection and is elevated in 90% is a possibility. In practice, JRA is

tis, 25 normal values for the WBC of patients with osteomyelitis.16,25 the most frequently diagnosed pedi-

count are seen frequently in osteo- However, early in the course of in- atric arthritis.31 It must be noted

myelitis.26 The differential is more fection, the ESR may be normal. Ex- that the rheumatoid factor test is

sensitive and may be abnormal in as treme elevation of ESR in what ap- positive in only 15% to 20% of chil-

many as 65% of children with osteo- pears to be isolated osteomyelitis dren with JRA, and is more fre-

myelitis and 70% with septic arthri- should raise the question of associ- quently positive in older children

tis. The complete blood cell count ated septic arthritis. and children in a poor functional

may reveal moderate to severe ane- C-reactive protein is an acute- class. 8 The finding of a positive

mia in cases of systemic juvenile phase protein synthesized by the antinuclear antibody test is impor-

rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), as well liver in response to inflammation. tant in the identification of children

as leukocytosis with active disease.8 Unlike the ESR, the CRP level rises most at risk for the development of

Patients with systemic-onset JRA within 6 hours of onset of symp- chronic uveitis, which may result in

may present with WBC counts in the toms and returns to normal within 6 blindness if untreated.

range of 30,000 to 50,000/mm3. The to 10 days with appropriate treat- Testing for Lyme disease should

platelet count may rise considerably ment. The CRP level is more sensi- be performed on any patient who

as well. tive than the WBC count or the ESR presents with acute arthritis and

The ESR is a sensitive indicator in assessing the effectiveness of who lives in or has recently traveled

of inflammation and is most helpful therapy and predicting recovery to an endemic area.32 The presenta-

in the diagnosis and follow-up of from osteomyelitis and septic arthri- tion of acute Lyme arthritis may

bone or joint infection. The ESR tis.27,29 The CRP value is not influ- have considerable overlap with that

reflects changes in the concentration enced by prior aspiration or drilling of septic arthritis, including fever,

of fibrinogen synthesized by the of the cortex, and a secondary rise local swelling, pain with range of

liver, which increases after 24 to 48 suggests relapse.29 The CRP level joint motion, and an elevated WBC

hours and may not return to normal should be determined on the initial count in joint aspirate. Serologic

for 3 weeks with appropriate treat- screening examination if musculo- confirmation of Lyme disease is

ment.27 In one study of previously skeletal infection is in the differen- based on a two-test approach con-

well children with new-onset limp, tial diagnosis. sisting of a preliminary enzyme-

an ESR elevated to over 50 mm/hr Aspiration and evaluation of joint linked immunosorbent assay and a

was associated with a clinically im- fluid should be performed when confirmatory Western immunoblot

portant diagnosis in 77% of cases.28 joint sepsis is considered in the dif- assay, which specifically examines

The ESR is also a sensitive indicator ferential diagnosis. Of the large the reactivity of antibodies.32

96 Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

John M. Flynn, MD, and Roger F. Widmann, MD

A B C

Figure 6 An 11-year-old girl sustained a suspected distal fibular physeal fracture. AP (A) and lateral (B) plain radiographs of the ankle

taken 10 days after the injury. C, Because of persistent pain and an ESR of 35 mm/hr, an MR imaging study of the distal portion of the leg

was obtained. The appearance of this transverse section at the distal fibula is consistent with fibular osteomyelitis and soft-tissue swelling

with an abscess, which were successfully treated with surgical drainage and antibiotic therapy. Cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus.

Making the Diagnosis narrow the differential diagnosis suspected. If septic arthritis of the

and establish the pace of evalua- hip is a possibility, ultrasound-

When a limping child is brought for tion. 33 Determining whether the guided aspiration may be indicated.

musculoskeletal evaluation, some gait is antalgic is the first step in Unfortunately, the presentations

potential diagnoses require urgent developing a differential diagnosis are usually not this straightforward.

treatment to ensure the best possible (Tables 1 and 2). The most common challenge is de-

outcome. Some conditions affect all The answers to these five essen- termining whether an acute limp is

age groups, but many conditions tial questions direct the evaluation due to trauma. A typical case is illus-

have a peak age of onset. Although of different clinical scenarios. For trated in Figure 6. The 11-year-old

there is increasing interest in prac- example, a healthy 4-year-old pre- patient had ankle pain after falling.

tice standardization with use of sents with the gradual onset of a Her pain persisted after casting of a

algorithms for many musculoskele- painless Trendelenburg gait. Exami- suspected fibular physeal fracture.

tal conditions, there are so many nation shows that there is unilateral The plain-radiographic appearance

exceptions in the evaluation of the limitation of hip motion. The work- remained normal. Her limp was

limping child that any single algo- up of this limp requires only a plain clearly due to pain, which was wors-

rithm will be unreliable for all pre- radiograph to establish the diagnosis ening with time. Because this was un-

sentations. Despite this complexity, of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease or de- characteristic for trauma, laboratory

there are five essential questions velopmental dysplasia of the hip. tests were obtained, which revealed

that the orthopaedist must answer In a very different scenario, an ill an ESR of 35 mm/hr. Because the

to direct the evaluation of a limping child presents with the sudden process could be localized by pain

child: (1) Is the limp due to pain? onset of an antalgic gait. Samples and swelling around the distal fibula,

(2) Did the limp develop suddenly for screening laboratory studies a bone scan was not needed. An MR

or gradually, or has it always been should be drawn, and plain radio- imaging study obtained to simultane-

there? (3) Is the child systemically graphs should be obtained for ana- ously evaluate the soft tissues, the

ill? (4) What type of limp does the tomic localization. If the site cannot bone, and the ankle joint revealed

child exhibit? (5) Can the problem be localized, a bone scan is valu- osteomyelitis with a soft-tissue ab-

be localized (specifically, is there a able. An MR imaging study may scess. The patient was successfully

point of maximum tenderness)? add important information, espe- treated with surgical drainage and

The answers to these questions will cially if a malignant condition is antibiotics.

Vol 9, No 2, March/April 2001 97

The Limping Child

Summary anatomic origin, and develop a good standing of normal and abnormal

working diagnosis on which to base gait, the orthopaedist can use the

Limping children commonly present a cost-effective strategy for ordering child’s age and the answers to five

to the orthopaedic surgeon, who is diagnostic tests. Armed with the essential questions to develop a dif-

expected to recognize the gait abnor- results of an appropriate history and ferential diagnosis and plan a selec-

mality, determine the probable physical examination and an under- tive approach to diagnostic testing.

References

1. Tuten HR, Gabos PG, Kumar SJ, 13. Capitanio MA, Kirkpatrick JA: Early Paterson DC: Ultrasonic features of

Harter GD: The limping child: A man- roentgen observations in acute osteo- acute osteomyelitis in children. J Bone

ifestation of acute leukemia. J Pediatr myelitis. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Joint Surg Br 1994;76:969-974.

Orthop 1998;18:625-629. Nucl Med 1970;108:488-496. 25. Faden H, Grossi M: Acute osteomye-

2. Sutherland DH, Olshen R, Cooper L, 14. Aronson J, Garvin K, Seibert J, Glasier litis in children: Reassessment of etio-

Woo SLY: The development of mature C, Tursky EA: Efficiency of the bone logic agents and their clinical charac-

gait. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980;62: scan for occult limping toddlers. J teristics. Am J Dis Child 1991;145:65-69.

336-353. Pediatr Orthop 1992;12:38-44. 26. Fink CW, Nelson JD: Septic arthritis

3. Ounpuu S, Gage JR, Davis RB: Three- 15. Bickerstaff DR, Neal LM, Booth AJ, and osteomyelitis in children. Clin

dimensional lower extremity joint Brennan PO, Bell MJ: Ultrasound Rheum Dis 1986;12:423-435.

kinetics in normal pediatric gait. J examination of the irritable hip. J Bone 27. Unkila-Kallio L, Kallio MJT, Peltola H:

Pediatr Orthop 1991;11:341-349. Joint Surg Br 1990;72:549-553. The usefulness of C-reactive protein

4. Phillips WA: The child with a limp. 16. Scott RJ, Christofersen MR, Robertson levels in the identification of concur-

Orthop Clin North Am 1987;18:489-501. WW Jr, Davidson RS, Rankin L, Drum- rent septic arthritis in children who

5. Wenger DR, Davids JR, Ring D: Disci- mond DS: Acute osteomyelitis in chil- have acute hematogenous osteomye-

tis and osteomyelitis, in Weinstein SL dren: A review of 116 cases. J Pediatr litis: A comparison with the usefulness

(ed): The Pediatric Spine: Principles and Orthop 1990;10:649-652. of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Practice. New York: Raven Press, 1994, 17. McCoy JR, Morrissy RT, Seibert J: Clin- and the white blood-cell count. J Bone

vol 1, pp 813-835. ical experience with the technetium-99 Joint Surg Am 1994;76:848-853.

6. Davids JR: Normal gait and assess- scan in children. Clin Orthop 1981;154: 28. Huttenlocher A, Newman TB: Evalua-

ment of gait disorders, in Morrissy RT, 175-180. tion of the erythrocyte sedimentation

Weinstein SL (eds): Lovell and Winter's 18. Canale ST, Harkness RM, Thomas PA, rate in children presenting with limp,

Pediatric Orthopaedics, 4th ed. Phila- Massie JD: Does aspiration of bones fever, or abdominal pain. Clin Pediatr

delphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996, vol 1, and joints affect results of later bone (Phila) 1997;36:339-344.

pp 93-116. scanning? J Pediatr Orthop 1985;5:23-26. 29. Unkila-Kallio L, Kallio MJT, Eskola J,

7. Morrissy RT: Bone and joint sepsis, in 19. Pennington WT, Mott MP, Thometz Peltola H: Serum C-reactive protein,

Morrissy RT, Weinstein SL (eds): Lovell JG, Sty JR, Metz D: Photopenic bone erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and

& Winter's Pediatric Orthopaedics, 4th ed. scan osteomyelitis: A clinical perspec- white blood cell count in acute hema-

Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996, tive. J Pediatr Orthop 1999;19:695-698. togenous osteomyelitis of children.

vol 1, pp 579-624. 20. Abernethy LJ, Lee YCP, Cole WG: Pediatrics 1994;93:59-62.

8. Cassidy JT, Petty RE: Textbook of Pedi- Ultrasound localization of subperi- 30. Morrissy RT, Shore SL: Septic arthritis

atric Rheumatology, 3rd ed. Philadel- osteal abscesses in children with late- in children, in Gustilo RB, Gruninger

phia: WB Saunders, 1995, pp 133-223. acute osteomyelitis. J Pediatr Orthop RP, Tsukayama DT (eds): Orthopaedic

9. Schreck P, Schreck P, Bradley J, Cham- 1993;13:766-768. Infection: Diagnosis and Treatment.

bers H: Musculoskeletal complica- 21. Alexander JE, Seibert JJ, Glasier CM, et Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1989, pp

tions of varicella. J Bone Joint Surg Am al: High-resolution hip ultrasound in 261-270.

1996;78:1713-1719. the limping child. J Clin Ultrasound 31. Cassidy JT, Nelson AM: The frequen-

10. MacEwen GD, Dehne R: The limping 1989;17:19-24. cy of juvenile arthritis [editorial]. J

child. Pediatr Rev 1991;12:268-274. 22. Zawin JK, Hoffer FA, Rand FF, Teele Rheumatol 1988;15:535-536.

11. Staheli LT, Corbett M, Wyss C, King H: RL: Joint effusion in children with an 32. Rose CD, Fawcett PT, Eppes SC, Klein

Lower-extremity rotational problems irritable hip: US diagnosis and aspira- JD, Gibney K, Doughty RA: Pediatric

in children: Normal values to guide tion. Radiology 1993;187:459-463. Lyme arthritis: Clinical spectrum and

management. J Bone Joint Surg Am 23. Miralles M, Gonzalez G, Pulpeiro JR, outcome. J Pediatr Orthop 1994;14:

1985;67:39-47. et al: Sonography of the painful hip in 238-241.

12. Myers MT, Thompson GH: Imaging children: 500 consecutive cases. AJR 33. Choban S, Killian JT: Evaluation of

the child with a limp. Pediatr Clin North Am J Roentgenol 1989;152:579-582. acute gait abnormalities in preschool

Am 1997;44:637-658. 24. Mah ET, LeQuesne GW, Gent RJ, children. J Pediatr Orthop 1990;10:74-78.

98 Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Вам также может понравиться

- Hallux Varus, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsОт EverandHallux Varus, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsОценок пока нет

- Baker2017 2Документ6 страницBaker2017 2rizky rositaОценок пока нет

- Flatfoot Deformity An OverviewДокумент9 страницFlatfoot Deformity An OverviewpetcudanielОценок пока нет

- Examination of The Hip Joint - RP's Ortho NotesДокумент5 страницExamination of The Hip Joint - RP's Ortho NotesSabari NathОценок пока нет

- Congenital Talipes Equinovarus (Clubfoot)Документ4 страницыCongenital Talipes Equinovarus (Clubfoot)Julliza Joy PandiОценок пока нет

- Knock Kneed Children: Knee Alignment Can Be Categorized As Genu Valgum (Knock-Knee), Normal or Genu Varum (Bow Legged)Документ4 страницыKnock Kneed Children: Knee Alignment Can Be Categorized As Genu Valgum (Knock-Knee), Normal or Genu Varum (Bow Legged)Anna FaОценок пока нет

- Lower Extremity DisordersДокумент8 страницLower Extremity DisordersisauraОценок пока нет

- Anomalies of Skeletal System-1Документ44 страницыAnomalies of Skeletal System-1Meena KoushalОценок пока нет

- Harris Et Al. (2004) - Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric FlatfootДокумент33 страницыHarris Et Al. (2004) - Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric FlatfootxtraqrkyОценок пока нет

- 239 1078 4 PBДокумент5 страниц239 1078 4 PBEmiel AwadОценок пока нет

- Anomalies of Skeletal System-1Документ44 страницыAnomalies of Skeletal System-1Meena Koushal100% (1)

- Pearls and Tricks in Adolescent Flat FootДокумент14 страницPearls and Tricks in Adolescent Flat FootVijay KumarОценок пока нет

- Pes Planus - Synopsis of CausationДокумент14 страницPes Planus - Synopsis of CausationSari HestiyariniОценок пока нет

- pGALS Examination OSCE GuideДокумент18 страницpGALS Examination OSCE GuideFanny PritaningrumОценок пока нет

- Ankle and FootДокумент31 страницаAnkle and FootmetoОценок пока нет

- The Pediatric Physical Examination - Back, Extremities, Nervous System, Skin, and Lymph Nodes - UpToDateДокумент12 страницThe Pediatric Physical Examination - Back, Extremities, Nervous System, Skin, and Lymph Nodes - UpToDateNedelcu MirunaОценок пока нет

- Dr. Andi Dwihantoro, SPB, Spba Sub Bagian Bedah Anak FK Ugm/Rsup DR Sardjito YkДокумент17 страницDr. Andi Dwihantoro, SPB, Spba Sub Bagian Bedah Anak FK Ugm/Rsup DR Sardjito Yknabilla sophianingtyas sofyanОценок пока нет

- Cerebral Palsy: and Its Sequelae.. (Consequences)Документ143 страницыCerebral Palsy: and Its Sequelae.. (Consequences)Agus SarjonoОценок пока нет

- Congenital Abnormalities MusculoSkeletal SystemДокумент116 страницCongenital Abnormalities MusculoSkeletal SystemVii syilsaОценок пока нет

- Pediatrics - OrthopedicsДокумент2 страницыPediatrics - OrthopedicsJasmine KangОценок пока нет

- Blount DiseaseДокумент21 страницаBlount DiseaseAidil NurshalОценок пока нет

- The Limping Child Pediatrics in Review 2015 Herman 184-97-0Документ16 страницThe Limping Child Pediatrics in Review 2015 Herman 184-97-0blume diaОценок пока нет

- Knee&Foot Part2Документ26 страницKnee&Foot Part2SarkawtОценок пока нет

- Evaluation of The Patient With Hip PainДокумент12 страницEvaluation of The Patient With Hip PainannisaОценок пока нет

- KneeДокумент24 страницыKneeMuhammad Fahmy100% (1)

- Pediatric Orthopaedics: Dr. Andreas Siagian SpotДокумент66 страницPediatric Orthopaedics: Dr. Andreas Siagian SpotFirdausi RiskiviawinandaОценок пока нет

- AnatomyДокумент11 страницAnatomyMON RUSSEL FRIASОценок пока нет

- Assessment of Gait Disorders in ChildrenДокумент3 страницыAssessment of Gait Disorders in ChildrenMadalina RarincaОценок пока нет

- Foot Deformities Infant: AssessmentДокумент5 страницFoot Deformities Infant: AssessmentAnup PednekarОценок пока нет

- Musculoskeletal Disorders: Carah Fe R. Bacus, RNДокумент40 страницMusculoskeletal Disorders: Carah Fe R. Bacus, RNcoosa liquorsОценок пока нет

- #8 Evaluation of The Child With A Limp - UpToDateДокумент45 страниц#8 Evaluation of The Child With A Limp - UpToDatedagmawiОценок пока нет

- Genu Varo PDFДокумент10 страницGenu Varo PDFazulqaidah95Оценок пока нет

- Genu ValgoДокумент9 страницGenu Valgoazulqaidah95Оценок пока нет

- Paediatric OrthopedicsДокумент5 страницPaediatric Orthopedicsamoody95Оценок пока нет

- Cavus Foot 2015 Foot and Ankle ClinicsДокумент13 страницCavus Foot 2015 Foot and Ankle ClinicsRadu StoenescuОценок пока нет

- Pediatric OrthopaedicДокумент66 страницPediatric OrthopaedicDhito RodriguezОценок пока нет

- The Prevalence of Four Common Pathomechanical Foot Deformities in Primary School Students in Taichung CountyДокумент9 страницThe Prevalence of Four Common Pathomechanical Foot Deformities in Primary School Students in Taichung Countyyayu latifahОценок пока нет

- Clinical Practice: The Spine From Birth To AdolescenceДокумент6 страницClinical Practice: The Spine From Birth To Adolescencechristian roblesОценок пока нет

- Lameness Examination in CattleДокумент13 страницLameness Examination in CattleguadialvarezОценок пока нет

- Case StudyДокумент11 страницCase StudyAnj TadxОценок пока нет

- Ortopedia Pediatrica en Recien Nacidos JAAOSДокумент11 страницOrtopedia Pediatrica en Recien Nacidos JAAOSjohnsam93Оценок пока нет

- Examinacion Fisica de La CaderaДокумент15 страницExaminacion Fisica de La CaderadanypauloОценок пока нет

- LimpДокумент7 страницLimpRakesh DudiОценок пока нет

- LUMBAR DISC NotesДокумент7 страницLUMBAR DISC NotesPrasadОценок пока нет

- Chapter 24Документ26 страницChapter 24Dr Uvarani Sp Care Rawang TinОценок пока нет

- Developmental Dysplasia of HipДокумент25 страницDevelopmental Dysplasia of HipKamran Khan Khalil100% (1)

- Williams2014Документ10 страницWilliams2014Eugeni Llorca BordesОценок пока нет

- Pediatric Pes Planus: A State - Of-The-Art Review James B. CarrДокумент12 страницPediatric Pes Planus: A State - Of-The-Art Review James B. CarrTyaAbdurachimОценок пока нет

- Cavus Foot: Monica Paschoal Nogueira,, Fernando Farcetta,, Alexandre ZucconДокумент12 страницCavus Foot: Monica Paschoal Nogueira,, Fernando Farcetta,, Alexandre ZucconCesar AlvaradoОценок пока нет

- Clinical ExaminationДокумент6 страницClinical Examinationarvind appОценок пока нет

- Sivaramakrishnan2015Документ5 страницSivaramakrishnan2015Eugeni Llorca BordesОценок пока нет

- Pediatricflatfoot: Pearls and PitfallsДокумент14 страницPediatricflatfoot: Pearls and PitfallsSuplementos Fit CarvajalОценок пока нет

- CTEVДокумент46 страницCTEVjhogie afitnandriОценок пока нет

- Pediatric Limbs DeformitiesДокумент139 страницPediatric Limbs DeformitiesrachmadyОценок пока нет

- DDHДокумент38 страницDDHSanjiv GoyalОценок пока нет

- Acute Fractures of The Pediatric Foot and AnkleДокумент7 страницAcute Fractures of The Pediatric Foot and AnkleAlejandro Godoy SaidОценок пока нет

- 01 Body Conformation of HorseДокумент32 страницы01 Body Conformation of HorseDrSagar Mahesh Sonwane100% (3)

- Screening Checklist: The Musculoskeletal Screening ExaminationДокумент36 страницScreening Checklist: The Musculoskeletal Screening ExaminationArden GabrielОценок пока нет

- CIRRHOSIS - Albumin in Decompensated Cirrhosis New Concepts and PerspectivesДокумент12 страницCIRRHOSIS - Albumin in Decompensated Cirrhosis New Concepts and PerspectivesntnquynhproОценок пока нет

- Cardiologia Croatica 2021 16 - 1-2 - 83Документ1 страницаCardiologia Croatica 2021 16 - 1-2 - 83daia4322746Оценок пока нет

- 3 Inflammation and RepairДокумент14 страниц3 Inflammation and RepaircedonuliОценок пока нет

- C-Reactive Protein (CRP)Документ9 страницC-Reactive Protein (CRP)Ibrahim Alturaiki100% (1)

- SDB Communication Guidance For IHE PCD-01 DEC (HL7) 1.3.0Документ27 страницSDB Communication Guidance For IHE PCD-01 DEC (HL7) 1.3.0Jose Perez PerezОценок пока нет

- Evms Critical Care Covid-19 Management ProtocolДокумент39 страницEvms Critical Care Covid-19 Management ProtocolUzletiszemОценок пока нет

- Quick ASDAS-CRP Calculation Form: Name: - DateДокумент2 страницыQuick ASDAS-CRP Calculation Form: Name: - DateHüseyin YelkenОценок пока нет

- s11255 019 02200 7Документ10 страницs11255 019 02200 7adri20121989Оценок пока нет

- Primary Sample Collection Manual FinalДокумент65 страницPrimary Sample Collection Manual FinalUnihealth-Quezon LaboratoryОценок пока нет

- Mitlis40 CRP 4+1 2019 PDFДокумент4 страницыMitlis40 CRP 4+1 2019 PDFTran Trong NghiaОценок пока нет

- S65 - PSC Haldwani Diagnostic Centre - Home Visit Sahukara Line, Opp. SS Jeena Base Hospital Nainital, HaldwaniДокумент3 страницыS65 - PSC Haldwani Diagnostic Centre - Home Visit Sahukara Line, Opp. SS Jeena Base Hospital Nainital, Haldwanirajasereddy1275Оценок пока нет

- TECO CRP Package InsertДокумент2 страницыTECO CRP Package InsertYosselyn Chilon VelasquezОценок пока нет

- 37 - Acute Rheumatic FeverДокумент1 страница37 - Acute Rheumatic FevernasibdinОценок пока нет

- EVMS Critical Care COVID-19 ProtocolДокумент17 страницEVMS Critical Care COVID-19 ProtocolInternos YopalОценок пока нет

- Blood Tests: Normal Values - Normal Laboratory Values - Merck Manual Professional VersionДокумент11 страницBlood Tests: Normal Values - Normal Laboratory Values - Merck Manual Professional VersionvitruvianxyzОценок пока нет

- Associations of Adiposity, Circulating Protein Biomarkers, and Risk of Major Vascular DiseasesДокумент11 страницAssociations of Adiposity, Circulating Protein Biomarkers, and Risk of Major Vascular DiseasesYuzhuo WangОценок пока нет

- Chemical Composition and Anti-Arthritic Activity of Anacyclus Valentinus Extract On Adjuvant-Induced Arthritis in RatsДокумент8 страницChemical Composition and Anti-Arthritic Activity of Anacyclus Valentinus Extract On Adjuvant-Induced Arthritis in RatsIJEAB JournalОценок пока нет

- اسئله شائعة ف مقابله المختبر 3 pdfДокумент6 страницاسئله شائعة ف مقابله المختبر 3 pdfAnas ShwbkОценок пока нет

- 1st Quarterly Progress Report of JEEViKAДокумент31 страница1st Quarterly Progress Report of JEEViKAJoe OgleОценок пока нет

- 2017 Article 531Документ7 страниц2017 Article 531dinimusmanОценок пока нет

- Cerebrovascular Diseases Risk Factors:: o o o o oДокумент4 страницыCerebrovascular Diseases Risk Factors:: o o o o otrinaОценок пока нет

- Reversing Type II Diabetes NaturallyДокумент3 страницыReversing Type II Diabetes NaturallyAnamaria Gheorghiu100% (2)

- 05.012.002.0045-2 Finecare IiДокумент2 страницы05.012.002.0045-2 Finecare IiAinun Jariah100% (1)

- Reumatoid ArthritisFDH2013Документ63 страницыReumatoid ArthritisFDH201395kodok85Оценок пока нет

- Faecal Calprotectin: Review ArticleДокумент14 страницFaecal Calprotectin: Review Articletrisna amijayaОценок пока нет

- Case Presentation OsteomylitisДокумент64 страницыCase Presentation OsteomylitisDemi Rose Bolivar100% (1)

- CommentsДокумент1 страницаCommentsHACK WITH PKОценок пока нет

- Systemic Lupous Erythematosus (SLE) Part 2Документ68 страницSystemic Lupous Erythematosus (SLE) Part 2Power La Victoria Floro100% (3)

- Inflammation Heart DiseaseДокумент4 страницыInflammation Heart DiseaseEvonneОценок пока нет

- Personalized Medicine of Monoclonal Antibodies in in Ammatory Bowel Disease: Pharmacogenetics, Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, and BeyondДокумент15 страницPersonalized Medicine of Monoclonal Antibodies in in Ammatory Bowel Disease: Pharmacogenetics, Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, and BeyondJessica Asitimbay ZuritaОценок пока нет