Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Nature and Definition of Criminal Procedure and The Sources of The Law of Criminal Procedure PDF

Загружено:

ABDOULIEОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Nature and Definition of Criminal Procedure and The Sources of The Law of Criminal Procedure PDF

Загружено:

ABDOULIEАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

ABDOU A.

MANNEH, GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE NOTES

BARRISTER AT LAW CANDIDATE

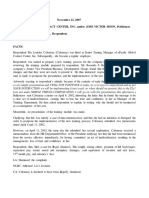

THE NATURE AND DEFINITION OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE

It’s important from the word go to define the limits or the perimeters of the subject Criminal

Procedure. It is therefore important to start by defining the words ‘Criminal’ and ‘Procedure’.

The word ‘criminal’ is derived from crime which is synonymous with the word ‘offence’. Offence

is the word used in our criminal code and it is defined under s. 2 of the Criminal Code as: “An act,

attempt, omission punishable by Law”. Thus to constitute a crime, the act or omission complained

of has to be designated by law to be a crime.

The word ‘procedure’ means the prescribed method governing certain processes. For example, the

method governing the process of admission to the Gambia Law School is primarily governed by

making an application to the effect and paying the prescribed fees. Students who do not follow

this procedure are not usually admitted. This is the stipulated procedure for admission to the

Gambia Law School as a student.

Criminal procedure, therefore, is the method laid down by law for bringing a person who is accused

of committing an offence before a court of law for trial. It also deals with the method to be adopted

by the court of trial, the powers of the court of trial, the right of appeal of a person convicted of a

crime and the right of the initiator of the proceedings – the prosecutor. Finally, it deals with the

rules governing procedure in appellate courts.

Assume, for example, that John went to the Albert Market in Banjul. He took a CD from Kerewan

Sounds Shop, concealed it in his pocket and walked away without paying for it. Outside the shop,

he was accosted by a private security man and taken to Banjul Police Station. The security man

and John made statements to the police at the police station. The police decide to charge John with

the offence of stealing the CD. He is given bail by the police and allowed to go home. He is to

report to Banjul Magistrates’ Court the following morning at 9 a. m. Certain points emerged from

this hypothetical illustration.

- Firstly, that a person found committing an offence can be arrested by a private person. In

this case, the security man (a private person) arrested John.

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 1

- Secondly, that a private person must take an arrested suspect to a police station and deliver

him to a police officer. This was what the security man did.

- Thirdly, that it is the duty of the police to enforce all laws. The owner of Kerewan sounds

did not enforce the law directly, but handed over John to the police to enforce the law.

- Fourthly, that the police have the power to give bail to a person accused of committing

certain offences. In this case, John was not detained but granted bail by the police.

- Finally, that the police prefer charges at the Magistrates’ Court. In the instance case, John

was charged with the offence of stealing at the Magistrates’ Court.

The issues that arose in this hypothetical illustration – those of arrest, enforcement of law,

investigation of crime and the interrogation of suspects, charge and bail are few examples of

matters that are exclusively procedural within the domain of criminal procedure. It is obvious that

criminal procedure is unlike substantive criminal law, which deals mainly with specific offences

known to law e.g. murder, stealing, rape, etc., the ingredients of such offences, and the defences

to such offences (e.g. bonafide claim of right, self-defence, insanity, mistake of fact etc).

Thus while knowledge of criminal law is essential for easier understanding of criminal procedure,

the two subjects are separate and distinct, the former dealing with substantive and the latter dealing

with the procedure.

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 2

SOURCES OF THE LAW OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE

The law dealing with the procedure to be followed when a person is alleged to have committed an

offence is found in several enactments. These laws range from the time such a person is arrested,

charged, tried, convicted or acquitted, sentenced, and if aggrieved files an appeal. We will

categorize these enactments into two: principal and secondary enactments. Apart from these

enactments there exist the practice and procedure applicable in criminal trials in the High Court in

England and the judicial interpretations of Gambian courts of the enactments and of common law1

courts with similar enactments. We will now consider the sources of criminal procedure.

1. PRINCIPAL ENACTMENT

The Criminal Procedure Code was enacted for the Gambia by Act 26 of 1933. Kenya’s 1930

Criminal Procedure Code was used as model. It should be noted that the Criminal Procedure Code

has from time to time been amended, consolidated and revised but the changes are not very

substantial. It is the principal enactment governing criminal procedure in The Gambia.

All offences under the Criminal Code are to be “inquired into, tried, and otherwise dealt with”

according to the provisions of the CPC.2 All other offences under any other law (for example the

Drug Control Act, Tourism Offences Act, Economic Crimes (Specified Offences) Act) are also to

be “inquired into, tried and otherwise dealt with” according to the provisions of the CPC subject

to any enactment for the time being in force regulating the manner and place of inquiring into,

trying, or otherwise dealing with such offences.3 Thus, subject to the provisions of section 3 (2) of

the CPC all offences in The Gambia must be inquired into, tried and dealt with in accordance with

the provisions of the CPC, irrespective of whether the offence is found in the Criminal Code or

any other enactment.

1

Note that common laws crimes continue to apply in The Gambia by virtue of section 2 (a) of the Criminal Code.

2

Section 3 (1) of the CPC. 3

Section 3 (2) of the CPC. Note the provisions of the District Tribunal Act and Rules on customary crimes and the

provisions on the Children’s Act and Rules on child offenders.

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 3

The provisions of the CPC apply to trials before the Supreme Court, Court of Appeal, High Court,

Magistrates’ Court. These provisions, however, do not apply to trials before a District Tribunal.3

The provisions of the Children’s Act and Children’s Court Rules also apply to trials before the

Children’s Court.

2. SECONDARY ENACTMENTS

Chapter IV of the Gambian Constitution deals exclusively with the fundamental human rights of a

person and these include the right to personal liberty guaranteed in section 19 and the right to fair

trial guaranteed in section 24. These rights, particularly the right to fair trial are a very important

feature of every criminal trial. A violation of the right to fair trial, for example, could need to a

conviction being set aside on appeal or a whole trial being declared null and void, and of no effect.

Searches are also dealt with in the Constitution.4 The Constitution also deals with the power of the

Director of Public

Prosecutions, subject to the control of the Attorney General, to initiate, takeover and discontinue

all public prosecutions.5 The Constitution further gives the President the power to grant a pardon,

after consulting with the Committee on the exercise of the prerogative of mercy. 6 Chapter VIII of

the Constitution also deal with the superior courts of record. The criminal jurisdiction of the

Supreme Court, Court of Appeal, High Court, and Special Criminal Court is dealt with in this

chapter. Their original and appellate jurisdiction with respect to criminal matters is dealt with as

well as their composition.

The Courts’ Act, the Supreme Court Act and Supreme Court Rules, and the Court of Appeal Act

and Court of Appeal Rules contain provisions regulating the composition, jurisdiction and powers

of courts created under these laws. When dealing with criminal cases, these courts must be guided

by the provisions of the laws creating them. These laws spell out the procedure to be followed by

an aggrieved party appealing from a decision of a lower court to a higher court. They therefore

also regulate criminal procedure.

The High Court Rules also to some extent regulate criminal procedure in that the rules, inter alia,

spell out the procedure to be followed on appeals from a subordinate court to the High Court

Some enactments make provisions relating to certain offences. These include the Economic

Crimes (Specified Offences) Act and the Drug Control Act both of which have specific provisions

on bail, a very important component of criminal procedure law.

3

See the definition of court in section 2 of the CPC

4

Section 23 of the Constitution

5

See section 85 of the Constitution

6

See section 81 of the Constitution

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 4

Other enactments have provisions relating to certain offenders and the procedure to be followed

by designated courts as contained in these laws for the trial and punishment of offenders. The

Children’s Act and the Children’s Court Rules, for example, regulate the trial of children. The

Coroner’s Act also regulates the powers and duties of the Coroner, the Gambia Armed Forces Act

and the Armed Forces (Regulations for Discipline) create offences and prescribe the procedure for

trial of offenders while the

Gambia National Army (Gambia National Guard Unit) Police Duties Regulations give the Gambia

National Guard police powers. The Police Act also lays down the powers and duties of the Gambia

Police Force.

The above-mentioned secondary enactments and a host of others, too many to be listed, constitute

a good source of the law governing criminal procedure.

3. ENGLISH HIGH COURT PROCEDURE AND PRACTICE IN CRIMINAL

MATTERS

Section 3 (3) of the CPC provides:

The procedure and practice to be observed in the High Court in the exercise of its criminal

jurisdiction shall, subject to the express provisions of this Code and any law for the time

being in force in The Gambia, be assimilated as nearly as circumstances admit to the course

of procedure and practice of Her Majesty’s High Court of Justice and the Courts of Oyer

and Terminer and General Gaol Delivery in England at the date of the coming into

operation of this Code.7

The procedure and practice of the English High Court of Justice and the Courts of Oyer and

Terminer and General Gaol Delivery therefore remain a very important source of criminal

procedure. A very good example of when our High Court can resort to the practice and procedure

of these courts is when the CPC and other applicable laws are silent on the procedure to be adopted

in a matter or where there are no express local laws on a matter.8

It should also be noted that section 3 (3) of the CPC contains a cut-off date. Section 3 (3) of the

CPC only applies to the practice and procedure of the said English Courts at the date of the coming

into operation of the CPC which is 1st October, 1934. Thus our High Court cannot rely on section

7

Cf s.363 of the Criminal Procedure Act of Nigeria which provides for the application of “the procedure and

practice for the time being in force in the High Court of Justice in England in criminal trials in the High Court in so

far as this Act has not specifically made provision therefor.”

8

Nigerian courts (their decisions are persuasive) have done so in the following cases: Board of Customs and Excise

v. Hassan [1978] 2 LRN 56, Simidele v. Commissioner of Police (1966) NMLR 116, Olugbusi & Ors. v. Commissioner

of Police [1970] 2 ALL nlr 1, Achadu v. The State 1981 91) NCR 16 10 (1891) AC 107 at 144 to 145. 11 (1892) AC 481

at 487 (PC).

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 5

3 (3) of the CPC to resort to the practice and procedure of the said English Courts after the said

date.

4. JUDICIAL INTERPRETATION OF ENACTMENTS

The courts interpret the said principal and secondary enactments to give effect to them. This means

the rules of interpretation of statutes must be adhered to when interpreting any of the above-named

enactments.

The current approach to the interpretation of a Code is found in the classic passage in the Judgment

of Lord Hershell in Bank of England v. Vagliano Brothers10. This passage was approved by the

Privy Council in the case of Robinson v. Canadian Pacific Railway Company11. Even though

Lord Hershell was discussing the 1882 Bills of Exchange Act, his remarks are equally applicable

to Criminal Procedure Codes. He stated:

I think the proper course is in the first instance to examine the language of the statute and

to ask what is its natural meaning, uninfluenced by any considerations derived from the

previous state of the law, and not to start with inquiring how the law previously stood and

then assuming that it was probably intended to leave it unaltered to see if the words of the

enactment will bear an interpretation in conformity with this view. If a statute, intended to

embody in a code a particular branch of the law, is to be treated in this fashion, it appears

to me that the utility will be almost entirely destroyed and the very object with which it

was enacted will be frustrated. The purpose of such statute surely was that on any point

specifically dealt with by it, the law should be ascertained by interpreting the language

used, instead of as before, by roaming over a vast number of authorities in order to discover

what the law was, examining it by minute critical examination of the prior discussions. I

am of course far from asserting that resort may never be had to the previous state of the

law for the purpose of aiding in the construction of the provisions of the code. If, for

example, a provision of doubtful import, such resort would be perfectly legitimate. Or

again if in a code on the law of negotiable instruments words to be found have previously

acquired a technical meaning or been used in a sense other than their ordinary one, in

relation to such instruments the same interpretation might well be put upon them in the

code. The first step to be taken should be to interpret the language of the statute and that

an appeal to earlier decisions can only be justified on some special ground.”

We can therefore deduce the following from Lord Herschell’s judgment:

a. That when interpretation the provisions of a code all pre-existing case law ceases to be

of authority as regards stating the law.

b. That the law is to be deduced from an examination of the language of the code, in its

natural meaning. It is therefore wrong to inquire as to the state of the preexisting law

in order to attempt to construe the provisions of the code in such a way as to make the

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 6

latter comply. Thus the resumption of statutory interpretation that an enactment does

not alter the pre-existing law does not apply to codes.

c. That under special circumstances, it is permissible to refer to the pre-existing law in

order to ascertain the meaning of a provision in a code. These special circumstances

are:

i. Where a provision of a code is of doubtful import. A provision is of doubtful

import where it is capable of two or more meanings and also where it is vague,

that is, where it is impossible to attribute any definite meaning to it.

ii. That the words used had acquired a technical meaning.

In interpreting provisions of the CPC therefore, the starting point should be interpreting them in

their ordinary and natural sense. Unwarranted references should never be made to the preexisting

law, except where a special ground or special circumstance exits. It is therefore wrong to ignore

the provisions of the CPC in favour of the common law or a foreign law. This does not mean that

in interpreting provisions of the CPC our courts cannot invoke in aid the interpretation given to

provisions in identical enactments in other jurisdictions. The CPC is very similar to the Criminal

Procedure Act of Nigeria and the criminal procedure code of many other common law countries.

This means interpretations given to the code by the courts in such countries can be invoked by

Gambian courts when interpreting provisions of the Code. It should however be noted that such

foreign decisions are of persuasive and not binding effect.

The courts may also use the opinions of acknowledged and distinguished jurists to help in

interpreting the provisions of the code or any other secondary enactment discussed above.

It should also be noted that the interpretation given to the said enactments, including the CPC, by

the Supreme Court, Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (before the Supreme Court was

created), Court of Appeal and West Africa Court of Appeal is binding on the High Court. The

interpretation given to the said enactments by the High Court is also binding on subordinate courts.

It follows therefore that the judicial interpretation of the said enactments constitutes a very

important source of criminal procedure.

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 7

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 8

COURTS VESTED WITH CRIMINAL JURISDUCTION

INTRODUCTION

The Courts of the Gambia are:

1. The Supreme Court

2. The Court of Appeal

3. The High Court

4. The Special Criminal Court

5. The Cadi Appeals Panel

6. Court Martial

7. The Industrial Tribunals

8. The Magistrates’ Court

9. The Cadi Court

10. The District Tribunals

11. The Rent Tribunals

12. The Children’s Court

The judicial power of The Gambia is vested in these courts and is exercised by them in accordance

with the respective jurisdictions conferred on them by law. The Chief Justice is the head of the

judiciary and is therefore responsible for the administration and supervision of the courts.

In the exercise of their judicial functions, the courts, the judges and other holders of judicial office

shall be independent and shall be subject only to the Constitution and the law, and, shall not be

subject to the control or direction of any other person or authority. The Government of The

Gambia and all government departments are also required to give assistance to the courts as the

courts may reasonably require to protect their independence, dignity and effectiveness. Note that

a judge or any other person exercising power shall not be liable for any act or omission by him or

her in good faith in the exercise of his or her judicial function.

Not all the courts stated above are vested with criminal jurisdictions. The Courts vested with

criminal jurisdiction (our concern for the purposes of this topic) are:

1. The Supreme Court

2. The Court of Appeal

3. The High Court

4. The Special Criminal Court

5. The Court Martial

6. The Magistrates’ Court

7. The Children’s Court

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 9

One of the most fundamental questions of law is whether a given court has jurisdiction to preside

over a given case. In any given case, a court of law must first of all bear in mind whether it has

jurisdiction over the persons appearing before him (in personam), whether it has jurisdiction over

the subject matter, or res, and whether it has jurisdiction to render the particular judgment sought.

The term jurisdiction is really synonymous with the word ‘power’ and is loosely understood in two

broad senses:

a. In the constitutive sense i.e., in the sense of the inherent power and competence of a court

of law to determine an issue. In this sense, it is the enabling Act creating a court that creates the

scope of its power over certain disputes and delimits it.

b. Secondly, jurisdiction may refer to the territory over which a particular court adjudicates.

This is called a court’s territorial jurisdiction.

We shall now consider all the courts in The Gambia that are vested with criminal jurisdiction.

1. THE SUPREME COURT

Before the Supreme Court of The Gambia was established under the 1997 Constitution, the highest

court for the Gambia was the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Section 125 (1) of the 1997

Constitution establishes the Supreme Court which shall consist of

a. the Chief Justice;

b. not less than four other Justices of the Supreme Court;

c. any judge of the Court of Appeal who is appointed to act as a Justice of the

Supreme Court. Such a judge must however be qualified to be appointed as a Justice of the

Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court is constituted by an uneven number of not less than five judges of the court. A

single judge of the Court may however exercise the powers of the court in any interlocutory matter.

See also UDP (No. 2) v. Attorney General (No. 2) 8where it was held that where the Supreme

Court is not sitting or in session, all interlocutory applications come before a single judge who

under s. 125 (2) of the Constitution may exercise the powers of the court in respect of that matter.

Even where the Supreme Court is in session or sitting, it may decide to hear and determine all such

applications or refer them to a single judge for determination. The Chief Justice presides over its

sittings and in his absence, the most senior of the judges of the Supreme Court presides. It can also

sit at any place in the Gambia appointed by the Chief Justice.

CRIMINAL JURISDICTION OF THE SUPREME COURT

The Supreme Court is the final court of appeal for the Gambia and its jurisdiction is as stated in

sections 126 to128 of the Constitution and sections 4 to 6 of the Supreme Court Act.

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 10

It has no original criminal jurisdiction. It hears appeals in criminal causes and matters from the

Court of Appeal. It is the court of last resort and its decisions are binding on all courts in The

Gambia. It t may also depart from its previous decision when it appears right to do so.

Criminal appeals to the Supreme Court could take any of the following forms:

APPEALS AS OF RIGHT

As stated in section 128 (1) of the Constitution, an appeal to the Supreme Court shall lie as of right

in any of the following instances:

a. From any judgment of the Court of Appeal in any civil or criminal matter from a judgment

of the High Court in the exercise of its original jurisdiction.

b. From any judgment of the Court of Appeal dismissing an appeal from a sentence of death

imposed by any other court.

c. In any matter as may be prescribed by an Act of the National Assembly.

APPEALS WITH THE LEAVE OF THE COURT OF APPEAL

An Appeal to the Supreme Court shall lie with leave of the Court of Appeal from a judgment of

the Court of Appeal in any matter commenced in a Court other than the High Court where the

Court of Appeal is satisfied that the case involves a substantive question of law or it is in the public

interest that the matter should be heard by the Supreme Court.

APPEALS WITH LEAVE OF THE SUPREME COURT

An appeal shall lie to the Supreme Court with its leave from any judgment of the Court of Appeal

other than the instances stated above.

All appeals to the Supreme Court are filed at the instance of a party to the proceedings at the Court

of Appeal or, with leave of the Supreme Court or the Court of Appeal, at the instance of any other

person having an interest in the matter or, in a criminal matter, at the instance of the Attorney

General acting in the interest of justice. Note that in any appeal at the instance of the Attorney

General, the Supreme Court shall have no power to reverse any acquittal at the court of first

instance or reverse a judgment allowing an appeal against conviction of a criminal offence.

SPECIAL LEAVE

The Supreme Court may entertain an application for special leave to appeal to the Supreme Court

in any criminal case and may grant leave accordingly.

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 11

REVIEW

The Supreme Court may also review any decision made or given by it on such grounds and subject

to such conditions as may be prescribed by the rules of court. The procedure for such a review is

provided for in rules 54 to 60 of the Supreme Court Rules. When exercising its power of review

under this section, the Supreme Court shall be constituted by not less than seven Justices of the

Supreme Court.

APPEALS PROCEDURE

The procedure for criminal appeals is as set out in rules 31 to 44 (Part III) of the Supreme Court

Rules. Matters dealt with under this part relate to:

- Time for, and manner of, appealing in criminal cases

- Notice of criminal appeal

- Grounds of appeal

- Notice of application for extension of time to appeal

- Notice of application for leave to appeal

- Forwarding of proceedings to the Court

- Copies of records for parties

- Action on decision on application to a single Justice

- Abandonment of appeal

- Withdrawal of notice of abandonment of appeal

- Temporary suspension orders

- Grant of bail

- Notification of final determination of appeal - Return of exhibits.

2. THE COURT OF APPEAL

The Court of Appeal is the second highest court for the Gambia. It consists of the President of the

Court of Appeal, not less than three justices of the Court of Appeal and such judge of the High

Court as the Chief Justice may by writing under his/her hand, select to sit in the Court of Appeal

for the determination of a particular matter. Such a judge selected from the High Court must

however be qualified to be appointed as a Judge of the Court of Appeal. The Court of Appeal is

constituted by three justices of the court but a single judge of the Court may exercise the powers

of the Court in any interlocutory matter, subject to an appeal from his or her decision to a bench

of three judges of the Court. The President of the Court of Appeal presides over the sittings of the

court and in his absence, the most senior of the other justices presides.

The President of the Court of Appeal in consultation with the Chief Justice may establish such

divisions of the Court of Appeal and in such place in the Gambia as he deems fit.

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 12

CRIMINAL JURISDICTION OF THE COURT OF APPEAL

The Court of appeal has no original jurisdiction. It only has appellate jurisdiction which is spelt

out in section 130 of the Constitution. It has jurisdiction to hear and determine appeals from

judgments, decrees and orders of the High Court and such other appellate jurisdiction as may be

conferred on it by an Act of the National Assembly. Appeals from any judgment, decree or order

of the High Court shall lie as of right. The Court of Appeal also hears appeals from a Court

Martial.

Furthermore, by virtue of section 14 of the Court of Appeal Act of The Gambia Act (Cap 6:02)

(hereinafter called the Court of Appeal Act), an appeal shall lie to the Court of Appeal from any

Disciplinary Committee of the General Legal Council suspending a legal practitioner of the

Supreme Court from practice or striking out his or her name off the Roll, and for the purposes of

the appeal the order shall be deemed to be an order of the High Court. In exercising its powers

under section 14 above, the Court of Appeal shall have full power to vary or discharge an order

made by the Disciplinary Committee. In particular, it may substitute an order of suspension for an

order striking an appellant off the Roll in any case in which it may think fit to do so.29

In addition to its jurisdiction to hear appeals, a Judge may reserve for consideration of the Court

of Appeal, on a case to be stated by him or her, any question of law which may arise on the trial

before the Judge of any person charged on information, and if a verdict of guilty be returned, may

postpone judgment, or may direct judgment be entered provisionally, subject to the opinion of the

Court of Appeal, respiting execution of the judgment, and the Court of Appeal shall have power

to hear and determine every such question.

In hearing and determining any appeal within its jurisdiction, the Court of Appeal shall all the

powers vested in the court from which the appeal is brought.

RIGHT OF APPEAL IN CRIMINAL CASES

By virtue of section 5 of the Gambia Court of Appeal Act, a person convicted in the High Court in

the exercise of its original jurisdiction may appeal to the Court of Appeal:

c. Against his or her conviction on any ground of appeal which involves a question of law

alone;

d. With the leave of the Court of Appeal or on the certificate of the Judge who tried him or

her that it is a fit case for appeal against his or her conviction on any ground of appeal which

involves a question of fact alone, or a question of mixed law and ground of appeal; and

e. With the leave of the Court of Appeal against the sentence passed on his or her conviction,

unless the sentence is one fixed by law.

DETERMINATION OF APPEALS IN ORDINARY CRIMINAL CASES

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 13

The Court of Appeal shall, on any appeal in ordinary criminal cases, allow the appeal if it thinks

that the verdict should be set aside on the ground that it is unreasonable or cannot be supported

having regard to the evidence, or that the judgment should be set aside on the ground of a wrong

decision of any law or that on any ground there was miscarriage of justice and in any other case

shall dismiss the appeal.

Where the Court of Appeal is of the opinion that a point raised on appeal might be decided in

favour of the appellant, it may nonetheless dismiss the appeal if it considers that no substantial

miscarriage of justice has actually occurred.

If the Court of Appeal allows an appeal against conviction, it shall, subject to the special provisions

of the Court of Appeal Act, quash the conviction and direct that a judgment and verdict of acquittal

be entered.

On appeal against sentence the Court of Appeal shall, if it thinks that a different sentence should

have been passed, quash the sentence passed at the trial, and pass such other sentence warranted

in law by the verdict (whether more or less severe) in substitution therefor as it ought to have been

passed, and in any other case shall dismiss the appeal.

POWERS OF THE COURT OF APPEAL IN SPECIAL CRIMINAL CASES

If it appears to the Court of Appeal that the appellant, though not properly convicted on some count

or some part of the information, has been properly convicted on some other count or part of the

information, the Court may either affirm the sentence passed on the appellant on the trial, or pass

such sentence in substitution therefor as it thinks proper, and as may be warranted in law by the

verdict on the count or part of the information on which the Court considers that the appellant has

been properly convicted.

Where an appellant has been convicted for an offence and the judge could, on the information,

have found him or her guilty of some other offence, then if it appears to the Court of Appeal that

the Judge must have been satisfied of facts which proved him or her guilty of that offence, the

Court of Appeal may, instead of allowing or dismissing the appeal, substitute for the verdict found

a verdict of guilty of that other offence, and pass such sentence in substitution for the sentence

passed at the trial as may be warranted in law for the other offence, not being a sentence of greater

severity.

If on any appeals it appears to the Court of Appeal that although the appellant was guilty of the act

or omission charged against him or her, he or she was insane at the time the act was done or

omission made so as not to be responsible according to law for his actions, the Court of Appeal

may quash the sentence passed by the trial court and order the appellant to be kept in custody as a

criminal lunatic in the same manner as if a special verdict had been found to that effect.

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 14

RE-VESTING AND RESTITUTION OF PROPERTY ON CONVICTION

The operation of any order for the restitution of any property to any person made on conviction on

information and the re-vesting, in case of any such conviction, in the original owner or his or her

representative of the property in stolen goods, shall (unless the trial judges direct to the contrary

in any case in which, in his or her opinion, the title to the property is not in dispute) be suspended

until the expiration of ten days after the date of the conviction but where leave to appeal is given

within ten days after the date of conviction, until the determination of the appeal. In cases where

the operation of an order, or a re-vesting, is suspended until the determination of the appeal, the

order or the re-vesting, as the case may be, shall not take effect as to the property in question if the

conviction is quashed on appeal.

Note that Court of Appeal may order, annul or vary any order made on a trial for restitution of any

property to any persons, although the conviction is not quashed. Note further that if such an order

is annulled, it shall not take effect and if varied, it shall take effect as varied.

TIME FOR APPEALING

Where a convict desires to appeal to the Court of Appeal, or to obtain the leave of the Court of

Appeal to appeal, he or she shall give notice of appeal or notice of his or her application for leave

to appeal in such a manner as may be directed by the rules of the court within ten days of the date

of conviction.

It should be noted that except in cases where an appellant is sentenced to death, the time within

which notice of appeal or notice on application may be given may be extended at any time by the

Court of Appeal or by the Court that convicted the appellant. Where the appellant is sentenced to

death or corporal punishment, the sentence shall not in any case be executed until after the expiry

of the time within which notice of appeal or an application for leave to appeal may be given under

section 9. Where notice to appeal is given, a death sentence or corporal punishment shall not be

executed until after the appeal is determined. Where an application for leave is refused, a sentence

of death or life imprisonment shall also not be executed until the determination of the application.

SUPPLEMENTARY POWERS OF THE COURT OF APPEAL

Section 10 of the Court of Appeal Act gives the court the following supplementary powers:

a. The power to order the production of any document, exhibit, or other thing connected with

the proceedings, the production of which it appears to be necessary for the determination of the

case.

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 15

b. The power, where the Court of Appeal deems it fit, to order any witnesses who have been

compellable witnesses at the trial to attend and be examined before the Court of Appeal, whether

they were or were not called at the trial, or order the examination of any such witnesses to be

conducted in a manner provided by the rules of court, or, in the absence of rules of court making

provision in that behalf, as it may direct, before any Judge of the Court of Appeal or other persons

appointed by the Court of Appeal for that purpose, and allow the admission of any deposition so

taken as evidence before the Court of Appeal.

c. The power, if it deems fit, to receive the evidence, if tendered, of any witness (including

the appellant) who is competent but not compellable witness, and, if the appellant makes an

application for the purpose, of the husband or wife of the appellant, in cases where the evidence of

the husband or wife could not have been given at the trial except of such application.

d. The power to order reference of any question arising on appeal and involving prolonged

examination of documents or accounts, or any scientific or local investigation, which in the Court’s

opinion cannot be conveniently conducted before it in a manner provided by the rules of court, or,

in the absence of such rules, the Court may order an inquiry and a report to a Special Commissioner

appointed by the Court. The Court then, where it deems fit, acts on any report issued by such

Commissioner.

e. The power to exercise in relation to the proceedings of the Court of Appeal any such powers

which may for the time being be exercised by the Court of Appeal in civil matters, and issue any

such warrants necessary for enforcing its orders or sentences.

It should be noted, however, that the Court of Appeal can’t increase any sentence by reason or in

consideration of any evidence that was not given at the trial.

RIGHT OF APPELLANT TO BE PRESENT

An appellant, notwithstanding that he or she is in custody, shall be entitled to be present, if he or

she desires it, on the hearing of his or her appeal. However, where the appeal is on some ground

involving a question of law alone or where the Court is considering an application for leave to

appeal or it is considering any matter preliminary or incidental to the appeal, the appellant does

not have to be present, except where the rules of court provide that he or she shall have the right

to be present or where the Court of Appeal gives him or her leave to be present. Where an

application for extension of time within which notice of appeal or notice of application for leave

is granted by the court that convicted the appellant, that court may give the appellant leave to be

present.

Note that the power of the Court of Appeal to pass any sentence under the Court of Appeal Act

may be exercised even where the appellant is absent for any reason.

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 16

ADMISSION OF APPELLANT TO BAIL

A Judge may, if he or she thinks fit, admit an appellant to bail pending the determination of his or

her appeal. An appellant who is not admitted to bail shall, pending the determination of his or her

appeal, be treated in such a manner as may be directed by the rules made under the Prisons Act.

The time during which the appellant, pending the determination of the appeal, is admitted to bail,

and subject to any directions which the Court of Appeal may give to the contrary on any appeal,

the time during which the appellant, if in custody, is specially treated as an appellant under this

section, shall not count as part of any term of imprisonment under his or her sentence.

In the case of an appeal under the Act, any imprisonment under the sentence of the appellant,

whether it is the sentence passed by the High Court or the sentence passed by the Court of Appeal,

shall, subject to any direction which may be given by the Court of Appeal, be deemed to be

resumed or to begin to run, as the case requires, if the appellant is in custody, as from the day on

which the appeal is determined, and if he or she is not in custody, as from the day on which he or

she is received into prison under the sentence.

APPEALS PROCEDURE

The procedure for criminal appeals before the Court of Appeal is as set out in rules 43-45, 47-54

and 56-70 to 44 of the Court of Appeal Rules (Part III). Matters dealt with under this part are:

- Method of appealing

- Judge’s Certificate

- Notices of Appeal

- Forwarding of proceedings in court below to Registrar

- Procedure on decision of application by single judge

- Notice of application for leave of appeal

- Abandonment of appeal

- Notice of abandonment of appeal may be withdrawn

- Person in custody in default of payment of fine

- Varying order of restitution or property

- Temporary suspension of orders made on conviction as to money, rewards, costs etc.

- Report of Judge of Court of trial

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 17

- Furnishing Judge of Court of trial with materials for report

- Procedure where question of law reserved

- Appellant and surety’s recognisances; before whom to be taken

- Notification of final determination of appeals - Notification of result of appeal -

Enforcement of orders, etc.

- Copies of record, etc., for appellant

- Attendance of witness before the Court

- Proceedings on reference

- Waiver of non-compliance with rules

- Costs of appeal

- Judgment of the Court

THE HIGH COURT

The High Court of the Gambia consists of the Chief Justice, not less than seven other justices of

the High Court and any judge of a superior court whom the Chief Justice may, by writing, request

to sit as a judge of the High Court. It is duly constituted by a single judge and may sit at such

places as the Chief Justice may determine. The Chief Justice may also establish permanent

divisions of the Court to sit at various places throughout the Gambia and appoint judges of the

Court to any such division.

ORIGINAL JURISDICTION OF THE HIGH COURT

Section 132 of the Constitution gives the High Court original jurisdiction to hear and determine all

civil and criminal proceedings. Thus the High Court of The Gambia has unlimited jurisdiction in

respect of criminal matters. This means it can try any offence under any law and pass any sentence

authorised by law.

APPELLATE JURISDICTION OF THE HIGH COURT

Section 132 (2) of the Constitution further gives the High Court jurisdiction to hear appeals from

Subordinate Courts, except the Cadi Court. Thus the High Court hears appeals from the

Magistrates’ Courts, the Children’s Court and District Tribunals in respect of criminal matters.

SUPERVISORY JURISDICTION OF THE HIGH COURT

The High Court also has supervisory jurisdiction over all lower courts and adjudicatory authorities

in The Gambia and in the exercise of its supervisory jurisdiction shall have powers to issue

directions, order or writs, including writs of habeas corpus, orders of certiorari, mandamus and

prohibition as it may consider appropriate for the purpose of enforcing its supervisory powers.

This is further buttressed by section 23 of the Courts Act which provides:

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 18

“The High Court shall exercise general powers of supervision over all subordinate courts and may,

at any time, call for and inspect or direct the inspection of all records of such courts, and may give

any directions which in any case the High Court may consider to be necessary in the interests of

justice.”

It follows therefore that any lower court or adjudicatory authority exercising its criminal

jurisdiction is subject to the supervisory jurisdiction of the High Court.

3. THE SPECIAL CRIMINAL COURT

This court is established by Section 134 of the Constitution. It is not yet constituted. It should be

constituted by a panel consisting of a Chairperson and not less than two other panel members and

has jurisdiction to hear and determine all criminal matters relating to theft, misappropriation and

other similar offences in which the public funds and public property are affected. The National

Assembly is mandated under section 136 of the Constitution to pass a law to give effect to the

provisions of the Constitution on the Special Criminal Court.

4. COURTS MARTIAL

These are courts convened under The Gambia Armed Forces Act (Cap 19:01) to try persons subject

to the Act. Sections 35-81 of the Act contain military offences (service offences) for which officers

and soldiers of the Gambia Armed Forces can be tried by a Court Martial. The offences range

from the serious offence of aiding the enemy (section 36 of the Act) which attracts the punishment

of death to the less serious offences of malingering (Section 61 of the Act) which attracts a sentence

of a term of imprisonment. Section 94 of the Act establishes a General Court Martial and

Disciplinary Court Martial and they are both convened by the President or such other authority as

may be authorized in that behalf by him.

A General Court Martial consists of not less than five (5) officers. Its President shall be an officer

of or above the rank of Lieutenant Colonel or an officer of corresponding rank with the Navy or

Air Force. Where the accused person is above the rank of Brigadier, the President of the General

Court Martial shall be an officer of or above the rank of the accused person. Members of the Court

Martial shall be of or above the rank of a Captain, or of or above the rank of Colonel or an officer

of corresponding rank.

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 19

Where the accused is of the rank Lieutenant Colonel or officer of corresponding rank, all members

of the court martial other than the President shall be of or above the rank of Major or an officer of

corresponding rank.

A General Court Martial may try any person subject to the Act who is alleged to have committed

an offence under the Act and the Chief Justice appoints a person to officiate as a Judge Advocate

at a General Court Martial. For persons disqualified to serve on a General Court Martial, see s.

98 of the Act.

A Disciplinary Court Martial is constituted by not less than three officers of or above the rank of

Captain or an officer with corresponding rank in the Navy or Air Force.

A Disciplinary Court Martial may try any person subject to the Act who is alleged to have

committed an offence under the Act or any regulations thereunder. However, a Disciplinary Court

Martial shall not pass a sentence including punishment higher in a scale of punishment than

dismissal with disgrace from the Armed Forces.

The Chief Justice may appoint a person to officiate as a Judge Advocate of a Disciplinary Court

Martial. For persons disqualified to serve as a Disciplinary Court Martial, see section 103 of the

Act. See also sections 104, 105, and 108 of the Act dealing with place of sitting of a Court Martial,

offences in respect of a Court Martial and decisions of a Court Martial respectively. Subject to the

exception mentioned in section 109 of the Act, a Court martial shall sit in open court and in the

presence of the accused person.

Please note that under section 90 of the Act, a Commanding Officer may try an accused person by

summary trial. The conditions stated in section 90 of the Act must, however, be satisfied. Superior

officers also have similar powers under section 90 of the Act.

5. MAGISTRATE’S COURTS

S. 14 (1) of the Courts Act (Cap: 6.01) provides:

”There is here by established in the City of Banjul and in every Division of the Gambia, a court

subordinate to the High Court which shall be presided over by a magistrate and which shall, subject

to any law for the time being in force, exercise jurisdiction within the City of Banjul or such

Division as the case may be. The style of such court shall be, in respect of Banjul, the Banjul

Magistrate’s Court and in respect of a Division, the divisional Court of the Division in respect of

which it has jurisdiction.’’

A Magistrates’ Court is duly constituted by one Magistrate lawfully empowered to adjudicate

therein. Magistrate’s Courts have both civil and criminal jurisdiction and the powers and

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 20

jurisdictions of magistrates are limited and determined by the powers and jurisdiction of the Class

of Magistrate presiding over a court.

Magistrates in The Gambia are of three classes:

- First Class Magistrates

- Second Class Magistrates

- Third Class Magistrates

-

Despite the above classification, it should be noted, however, that subject to express provisions of

any other law and to any directions of the High Court given under section 23 of the Courts Act to

the contrary, it is lawful for any Second or Third Class Magistrate to take cognizance of and make

orders in relation to any preliminary or interlocutory proceeds in any matter which would otherwise

be within the jurisdiction only of a First Class Magistrate.

Note further that a Governor in charge of a Region and every Administrative Officer in a Region

other than a Governor could serve as Second Class and Third Class Magistrates respectively. Any

two Justices of the Peace also have the powers of a Third Class Magistrate.

CRIMINAL JURISDICTION OF MAGISTRATES

The criminal jurisdiction of a magistrate is as spelt out in the CPC. Note that the jurisdiction to

try an offence is different from the jurisdiction to impose punishment.

JURIDICTION OVER OFFENCES

By virtue of section 5 of the CPC, a Magistrates’ Court may try any offence under any law, except

the offence of treason. Nothing in this section, however, shall:

“(a) derogate from any law which provides that a particular offence shall be triable only by a

subordinate court of a particular class or classes or by a court other than a subordinate court; or

(b) be deemed to prohibit the exercise of the power of the High Court to transfer any case for trial

by itself or by any other subordinate court, or of the Attorney General to require that a case triable

by a subordinate court be tried by the High Court.”

Before this amendment was introduced, a Magistrates’ Court could only try offences for which the

maximum sentence for imprisonment was ten years or less. Thus Magistrates’ Courts did not have

the jurisdiction to try offences such as murder, rape, manslaughter, arson etc. At the moment

magistrate can try all offences, except treason, irrespective of the magistrate’s class.

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 21

JURISDICTION TO IMPOSE PUNISHMENT

By virtue of section 5 (2), a First Class Magistrate may pass any sentence authorized by law. Thus

a First Class magistrate can pass a death sentence or impose life imprisonment or impose any fine.

A Second Class Magistrate may impose any of the following sentences or both:

a. Imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten (10) years.

b. Fine not exceeding five hundred thousand dalasis (D500, 000).

A Third Class Magistrate may impose any of the following sentences or both of them:

a. Imprisonment for a period not exceeding five years and

b. Fine not exceeding two hundred and fifty thousand dalasis (D250, 000).

Before the said amendment a First Class magistrate could not pass a sentence of imprisonment

exceeding seven years. A Second Class Magistrate could not pass a sentence of imprisonment

exceeding five years and a fine exceeding five thousand dalasis while a Third Class Magistrate

could not pass a sentence of imprisonment exceeding one year and a fine of more than one thousand

dalasis.

8. DISTRICT TRIBUNALS

Section 9 of the District Tribunal Act (Cap 6:03) provides:

“The criminal jurisdiction of a District Tribunal shall extend, subject to the provisions of this Act,

to the hearing, trial and determination of all criminal charges or matters in which any person is

accused of having wholly or in part within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal committed or been

accessory to the committing of an offence.”

On its face, this section seems to give District Tribunals jurisdiction over all criminal matters

coming from their respective jurisdictions, including murder, treason, rape, etc. Section 12 of the

District Tribunal Act saves the situation and it provides:

“The President may, by Order, confer upon all or any District Tribunals jurisdiction to enforce

within the local limits of their jurisdiction, all or any of the provisions of any act specified in such

Order and to impose penalties on such persons subject to the jurisdiction of the Tribunal who

offend such against provisions, subject to such restrictions and limitations, if any, as may be

specified in the Order”.

The District Tribunals (Jurisdiction under certain Acts) Order was made under this section (section

12). This order restricts the criminal jurisdiction of District Tribunals and the penalties they might

impose. For offences under the Criminal Code, this order provides that all District Tribunals have

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 22

jurisdiction over any offence, which in accordance with the Criminal Procedure Code, can be tried

by a Subordinate Court of the Second Class.

For offences under the Public Health Act, (Cap 40:02) only the Tribunals in the following districts

are given the jurisdiction to enforce its provisions:

1. Lower Nuimi District.

2. Foni Bondali District

3. Foni Kansala District

4. Foni Bintang Karenai District

5. Kombo East District

6. Kombo Central District

7. Kombo South District

8. Kombo North District

9. Lower Baddibu District

10. Upper Baddibu District

11. Lower Saloum District

12. Niani District

13. Janjanbureh District

14. Fulladu East District

15. Fulladu West District

16. Eastern Niamina District

17. Niamina Dankuku District

18. Kantora District

All District Tribunals can enforce regulations made under the Land (Regions) Act (Cap 57:03),

Farmers Trading Act (Cap 59:04) and the Bicycles Act (Cap 70:06).

Rule 6 (e) of the District Tribunal Rules gives Group District Tribunals full jurisdiction in causes

concerning offences against customary law. Single Tribunals have similar jurisdiction under Rule

6 (m).

It is submitted that these provisions (rule 6 (e) and (m) of the rules and s.13 of the Act) giving

District Tribunals jurisdiction over customary offences should be revisited because they breed

uncertainty. One of the main features of customary law is its flexibility. Customary law has always

shown unquestionable adaptability to altered circumstances. This means something permissible

today might be forbidden tomorrow and vice versa. Bearing in mind the fact that customary law is

largely unwritten and the fact that criminal law regulates our behaviour and its application might

border on an individual’s liberty and freedom, its provisions must be easily ascertainable. The

best way this can be done is by codification. This guarantees certainty, easy reference and access.

It is therefore submitted that the criminal jurisdiction of our District Tribunals should be restricted

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 23

to offences under our written laws. A person should not be convicted of a criminal offence unless

the penalty therefor is prescribed under a written law. This is in line with the law in many common

law jurisdictions. In Nigeria, for example, the Nigerian Constitution and s. 3 (2) Penal Code, which

is applicable in the North, prohibits the punishment of any offender under any native law or

custom.

Please note that in some instances, District Tribunals do not have jurisdictions over parties resident

in their Districts. The Minister for Local government is authorized under section 8 of the District

Tribunal Act to direct that any person or class of persons, who would otherwise be subject to the

jurisdiction of a District Tribunal, shall not be subject to the jurisdiction of a District Tribunal

except with their consent. Under a direction called “Persons not subject to the jurisdiction of

District Tribunals except with their consent”, the following classes of people are not subject to the

jurisdiction of District Tribunals, except with their consent.

1. Members of the Armed forces of the Gambia

2. Members of the Gambia Police Force

3. Members of the House of Representatives (now National Assembly)

These persons must therefore consent before they can be subject to the jurisdiction of District

Tribunals. It must be emphasized that nothing stops the Minister from further directing that the

said list be extended to include other classes of persons.

POWER TO SUMMON WITNESSES

Every District Tribunal has the power to summon any person before it for The purpose of giving

evidence. Any person who fails without reasonable excuse to obey a summons lawfully issued by

a District Tribunal shall be liable to a fine not exceeding fifty dalasis or in default of payment, to

imprisonment with or without hard labour for a term not exceeding one month. PROCEDURE IN

CRIMINAL CASES

It is important to note the procedure in criminal matters before the District Tribunals. Section 20

of the District Tribunal Act provides that subject to such rules as may be prescribed, the practice

and procedure of District Tribunals shall be regulated in accordance with customary law.

Therefore, customary law and rules 9-15 of the District Tribunal Rules apply in criminal matters

before District Tribunals.

By virtue of these rules, proceedings before a District Tribunal are commenced by a complaint or

information made to the tribunal during the sittings of the court, or if the court is not sitting to the

president of the tribunal, who then decides, after hearing the complaint or information, whether it

shall be entertained. If the tribunal or the president decides to entertain the complaint, a summons

is issued against the offender. By Virtue of rule 20 of the District Tribunal Rules, such a summons

may either be in writing or verbal. An offender who disobeys the summons or who is charged with

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 24

a serious offence, may be arrested and brought before the tribunal that made the order. However,

such an offender must not be detained for no longer than is reasonably necessary. This provision

in the District Tribunal Rules is overridden by section 19 (b) of the Constitution which requires an

arrested person to be taken without delay before a court within 72 hrs.

Legal practitioners are also not allowed to appear or act for any party before a District Tribunal by

virtue of section 33 of the District Tribunal Act. Lawyers cannot therefore appear on behalf of an

accused person charged with a criminal offence before a District Tribunal. The popular belief,

especially with District Tribunal members, seems to be that since none of them is legally trained,

lawyers should not appear before them and confuse them with the inherited English legal system

and its intricacies.

It is submitted that section 33 of the District Tribunal Act contradicts section 24 (3) (d) of the 1997

Constitution which provides:

“Every person who is charged with a criminal offence shall be permitted to defend himself/herself

before the court in person or, at his or her own expense by a legal representative of his or her

choice.”

Section 4 of the Constitution emphasizes the supremacy of our Constitution and consequently

section 33 of the District Tribunal Act is void to the extent of the inconsistency with the

constitution.

CONTEMPT OF COURT

Any person subject to the jurisdiction of a District Tribunal who shall omit to produce or deliver

up a document on the lawful order of such Tribunal or who shall contumaciously refuse of neglect

to comply with the lawful order of such Tribunal, or who shall refuse to answer any question

lawfully asked by the Tribunal or to sign any statement lawfully required by the Tribunal, or who

intentionally insults the Tribunal or any member thereof, or who intentionally interrupts the

proceedings thereof at any stage shall be guilty of contempt of court and shall be liable to a fine

not exceeding fifty dalasis and in default of payment to imprisonment with or without hard labour

not exceeding one month.

PUNISHMENTS, FINES AND COMPENSATION

Section 13 of the District Tribunal Act provides that for offences against customary law, a District

Tribunal may, subject to the provisions of the Act, impose a fine or may order imprisonment with

or without hard labour or both fine and imprisonment, or may inflict any punishment authorised

by customary law. However, such imprisonment must not be repugnant to natural justice and

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 25

humanity and must not be excessive but shall always be proportioned to the nature and

circumstances of the offence. Where corporal punishment is ordered, it shall not be inflicted upon

a person aged sixteen years or upwards. This provision is now overridden by section 220 (9) of

the Children’s Act which bars the imposition of capital punishment under children. In all other

instances in which corporal punishment is permissible, section 21 (3) of the District Tribunal

(discussed below) must be complied with.

Persons sentenced by a District Tribunal to imprisonment may be detained in a place authorised

by the Minister as a local prison or in a prison established under the Prisons Act.

Where a fine is imposed by a District Tribunal, the tribunal may order that such a fine be paid at

such time or times and by such instalments as it shall deem fit. If the fine is not paid, the District

Tribunal may order that it be levied by the sale of any property belonging to the offender or that

the offender undergoes imprisonment in default of the payment of the fine. See section 15 of the

District Tribunal Act.

A District Tribunal can also direct that a fine or any part thereof be paid to the victim of the

offender. If the victim accepts such payments, he cannot maintain any suit for the recovery of

damages or the loss or injuries sustained. The law here is different from the law as it applies to

other courts. At the Magistrates’ Courts, fines are paid to the government coffers and not to the

victim.

REPORT OF CASES TO BE SUBMITTED TO THE GOVERNOR

All District Tribunals are required to submit to the Governor in writing, or if so directed, orally, a

report of all cases tried in the Tribunal, and if the report is made orally, a record of all cases so

reported shall be made by the officer to whom the report was made.

Where a District Tribunal imposes a sentence of corporal punishment , or of more than fourteen

days’ imprisonment, it shall report the case to the Governor forthwith. A sentence of corporal

punishment shall not be executed unless and until the sentence has been confirmed by the Governor

and the High Court and any sentence shall be so executed in accordance with the provisions of

section 30 of the Criminal Code.

REVISIONARY POWERS OF GOVERNORS

By virtue of section 23 of the District Tribunal Act, all Governors shall at all times have access to

any District Tribunal in their regions and to the records of such Tribunals and may:

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 26

a. Revise any of the proceedings of a Tribunal, whether civil or criminal, and may make such

order or pass such sentence therein as the District Tribunal could have made or passed. No sentence

of fine of imprisonment can, however, be increased by such Governor without the accused being

given the opportunity to be heard;

b. Order any case to be re-tried either before the same Tribunal or before any other District

Tribunal of competent jurisdiction;

c. Transfer any cause or matter to the subordinate court established by the Courts Act for the

Division concerned. This power given to Governors is exercisable either before trial or at any stage

of the proceedings for trial or after sentence passed or judgment given for the re-trial.

It should be noted that the powers conferred upon a Governor under section 23 (1) cannot be

exercised after an appeal is made to the High Court under section 26 of the District Tribunal Act.

These powers cannot also be exercised by a District Tribunal after the expiration of three months

from the termination of proceedings in the District Tribunal. A review commenced before a

Governor before the expiration of the said three months may however be completed thereafter.

Note finally that in every case where a Governor exercises such power of review, he or she shall

record any reasons for exercising it and place a date of his doing so in writing in the record of the

District Tribunal.

APPEALS

Any party who feels aggrieved by a judgment, order or decision of a District Tribunal in the

exercise of its criminal jurisdiction or of a Governor in the exercise of his or her powers under

section 23 of the District Tribunal Act may appeal to the High Court. The powers of the High

Court on appeal are spelt out in section 28 of the District Tribunal Act

DISTRICT TRIBUNALS

CRIMINAL JURISDICTION

Section 9 of the District Tribunal Act (Cap 6:03) provides:

“The criminal jurisdiction of a District Tribunal shall extend, subject to the provisions of this Act,

to the hearing, trial and determination of all criminal charges or matters in which any person is

accused of having wholly or in part within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal committed or been

accessory to the committing of an offence.”

On its face, this section seems to give District Tribunals jurisdiction over all criminal matters

coming from their respective jurisdictions, including murder, treason, rape, etc. Section 12 of the

District Tribunal Act saves the situation and it provides:

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 27

“The President may, by Order, confer upon all or any District Tribunals jurisdiction to enforce

within the local limits of their jurisdiction, all or any of the provisions of any act specified in such

Order and to impose penalties on such persons subject to the jurisdiction of the Tribunal who

offend such against provisions, subject to such restrictions and limitations, if any, as may be

specified in the Order”.

The District Tribunals (Jurisdiction under certain Acts) Order was made under this section (section

12). This order restricts the criminal jurisdiction of District Tribunals and the penalties they might

impose. For offences under the Criminal Code, this order provides that all District Tribunals have

jurisdiction over any offence, which in accordance with the Criminal Procedure Code, can be tried

by a Subordinate Court of the Second Class.

For offences under the Public Health Act only the Tribunals in the following districts are given the

jurisdiction to enforce its provisions:

1. Lower Nuimi District.

2. Foni Bondali District

3. Foni Kansala District

4. Foni Bintang Karenai District

5. Kombo East District

6. Kombo Central District

7. Kombo South District

8. Kombo North District

9. Lower Baddibu District

10. Upper Baddibu District

11. Lower Saloum District

12. Niani District

13. Janjanbureh District

14. Fulladu East District

15. Fulladu West District

16. Eastern Niamina District

17. Niamina Dankuku District

18. Kantora District

All District Tribunals can enforce regulations made under the Land (Regions) Act (Cap 57:03),

Farmers Trading Act (Cap 59:04). All District Tribunal can enforce sections 3 and 4 of the Bicycles

Act (Cap. 70:06) and regulations 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 21 of the Bicycle Regulations made under

the Bicycles Act.

Rule 6 (e) of the District Tribunal Rules gives Group District Tribunals full jurisdiction in causes

concerning offences against customary law. Single Tribunals have similar jurisdiction under Rule

6 (m).

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 28

It is submitted that these provisions (rule 6 (e) and (m) of the rules and s.13 of the Act) giving

District Tribunals jurisdiction over customary offences should be revisited because they breed

uncertainty. One of the main features of customary law is its flexibility. Customary law has always

shown unquestionable adaptability to altered circumstances. This means something permissible

today might be forbidden tomorrow and vice versa. Bearing in mind the fact that customary law is

largely unwritten and the fact that criminal law regulates our behaviour and its application might

border on an individual’s liberty and freedom, its provisions must be easily ascertainable. The

best way this can be done is by codification. This guarantees certainty, easy reference and access.

It is therefore submitted that the criminal jurisdiction of our District Tribunals should be restricted

to offences under our written laws. A person should not be convicted of a criminal offence unless

the penalty therefor is prescribed under a written law. This is in line with the law in many common

law jurisdictions. In Nigeria, for example, the Nigerian Constitution and s. 3 (2) Penal Code, which

is applicable in the North, prohibits the punishment of any offender under any native law or

custom.

Please note that in some instances, District Tribunals do not have jurisdictions over parties resident

in their Districts. The Minister for Local government is authorized under section 8 of the District

Tribunal Act to direct that any person or class of persons, who would otherwise be subject to the

jurisdiction of a District Tribunal, shall not be subject to the jurisdiction of a District Tribunal

except with their consent. Under a direction called “Persons not subject to the jurisdiction of

District Tribunals except with their consent”, the following classes of people are not subject to the

jurisdiction of District Tribunals, except with their consent.

1. Members of the Armed forces of the Gambia

2. Members of the Gambia Police Force

3. Members of the House of Representatives (now National Assembly)

These persons must therefore consent before they can be subject to the jurisdiction of District

Tribunals. It must be emphasized that nothing stops the Minister from further directing that the

said list be extended to include other classes of persons.

QUORUM

For the purpose of hearing any case in a District Tribunal, it shall be sufficient if there is present

at the hearing the President, or the Vice President, and at least two other members. The decision

of the majority shall be the decision of the tribunal and where there is an equality of votes, the

President or other presiding member shall have a casting vote.

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 29

POWER TO SUMMON WITNESSES

Every District Tribunal has the power to summon any person before it for The purpose of giving

evidence. Any person who fails without reasonable excuse to obey a summons lawfully issued by

a District Tribunal shall be liable to a fine not exceeding fifty dalasis or in default of payment, to

imprisonment with or without hard labour for a term not exceeding one month.2

PROCEDURE IN CRIMINAL CASES

It is important to note the procedure in criminal matters before the District Tribunals. Section 20

of the District Tribunal Act provides that subject to such rules as may be prescribed, the practice

and procedure of District Tribunals shall be regulated in accordance with customary law.

Therefore, customary law and rules 9-15 of the District Tribunal Rules apply in criminal matters

before District Tribunals.

By virtue of these rules, proceedings before a District Tribunal are commenced by a complaint or

information made to the tribunal during the sittings of the court, or if the court is not sitting to the

president of the tribunal, who then decides, after hearing the complaint or information, whether it

shall be entertained. If the tribunal or the president decides to entertain the complaint, a summons

is issued against the offender. By Virtue of rule 20 of the District Tribunal Rules, such a summons

may either be in writing or verbal. An offender who disobeys the summons or who is charged with

a serious offence, may be arrested and brought before the tribunal that made the order. However,

such an offender must not be detained for no longer than is reasonably necessary. This provision

in the District Tribunal Rules is overridden by section 19 (b) of the Constitution which requires an

arrested person to be taken without delay before a court within 72 hrs.

Legal practitioners are also not allowed to appear or act for any party before a District Tribunal by

virtue of section 33 of the District Tribunal Act. Lawyers cannot therefore appear on behalf of an

accused person charged with a criminal offence before a District Tribunal. The popular belief,

especially with District Tribunal members, seems to be that since none of them is legally trained,

lawyers should not appear before them and confuse them with the inherited English legal system

and its intricacies.

It is submitted that section 33 of the District Tribunal Act contradicts section 24 (3) (d) of the 1997

Constitution which provides:

“Every person who is charged with a criminal offence shall be permitted to defend himself/herself

before the court in person or, at his or her own expense by a legal representative of his or her

choice.”

GAYE SOWE - LECTURER – THE GAMBIA LAW SCHOOL Page 30

Section 4 of the Constitution emphasizes the supremacy of our Constitution and consequently

section 33 of the District Tribunal Act is void to the extent of the inconsistency with the

constitution.

CONTEMPT OF COURT

Any person subject to the jurisdiction of a District Tribunal who shall omit to produce or deliver

up a document on the lawful order of such Tribunal or who shall contumaciously refuse of neglect

to comply with the lawful order of such Tribunal, or who shall refuse to answer any question

lawfully asked by the Tribunal or to sign any statement lawfully required by the Tribunal, or who

intentionally insults the Tribunal or any member thereof, or who intentionally interrupts the

proceedings thereof at any stage shall be guilty of contempt of court and shall be liable to a fine

not exceeding fifty dalasis and in default of payment to imprisonment with or without hard labour

not exceeding one month.

PUNISHMENTS, FINES AND COMPENSATION

Section 13 of the District Tribunal Act provides that for offences against customary law, a District

Tribunal may, subject to the provisions of the Act, impose a fine or may order imprisonment with

or without hard labour or both fine and imprisonment, or may inflict any punishment authorised

by customary law. However, such imprisonment must not be repugnant to natural justice and

humanity and must not be excessive but shall always be proportioned to the nature and

circumstances of the offence. Where corporal punishment is ordered, it shall not be inflicted upon

a person aged sixteen years or upwards. This provision is now overridden by section 220 (9) of

the Children’s Act which bars the imposition of capital punishment under children. In all other

instances in which corporal punishment is permissible, section 21 (3) of the District Tribunal

(discussed below) must be complied with.

Persons sentenced by a District Tribunal to imprisonment may be detained in a place authorised

by the Minister as a local prison or in a prison established under the Prisons Act.