Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Family Caregiver Contribution To Self-Care

Загружено:

Velicia MargarethaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Family Caregiver Contribution To Self-Care

Загружено:

Velicia MargarethaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing

Vol. 32, No. 6, pp 576Y583 x Copyright B 2017 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Family Caregiver Contribution to Self-care

of Heart Failure

An Application of the

Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model

Yuxia Chen, BM, RN, MSN(c); Huijing Zou, BM, RN, MSN(c); Yanting Zhang, BSN, RN, MSN(c);

Wenjie Fang, BM, RN, MSN(c); Xiuzhen Fan, PhD, RN

Background: Adherence to self-care behaviors improves outcomes of patients with heart failure (HF). Caregivers

play an important role in contributing to self-care. Objective: We aimed to explore the relationships among HF

knowledge, perceived control, social support, and family caregiver contribution to self-care of HF, based on the

Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model. Methods: Two hundred forty-seven dyads of eligible patients

with HF and family caregivers were recruited from a general hospital in China. Structural equation modeling was

used to analyze the data obtained with the Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of Heart Failure Index, the Heart

Failure Knowledge Test, the Control Attitudes Scale, and the Social Support Rating Scale. Results: In this model,

caregiver contribution to self-care maintenance was positively affected by perceived control (" = .148, P = .015)

and caregiver confidence in contribution to self-care (" = .293, P G .001). Caregiver contribution to self-care

management was positively affected by HF knowledge (" = .270, P G .001), perceived control (" = .140, P = .007),

social support (" = .123, P = .019), caregiver confidence in contribution to self-care (" = .328, P G .001), and

caregiver contribution to self-care maintenance (" = .148, P = .006). Caregiver confidence in contribution to

self-care was positively affected by HF knowledge (" = .334, P G .001). Conclusions: Heart failure knowledge,

perceived control, and social support facilitated family caregiver contribution to self-care of HF. Targeted

interventions that consider these variables may effectively improve family caregiver contributions to self-care.

KEY WORDS: caregivers, heart failure knowledge, perceived control, self-care, self-efficacy, social support

H eart failure (HF) is a particularly common syn-

drome worldwide, increasing in prevalence and

incidence because of the aging of the population.1 It

is anticipated that, by 2030, more than 8 million people

will have HF in the United States.2 Moreover, between

2012 and 2030, the total direct medical costs of HF

are estimated to increase from $21 to $53 billion.2

Yuxia Chen, BM, RN, MSN(c) The trajectory of HF is unpredictable, with a gradual

MSN Candidate, School of Nursing, Shandong University, Jinan, decline in physical function that is accompanied by

PR China. heavy symptom burden, a high hospitalization rate,

Huijing Zou, BM, RN, MSN(c)

MSN Candidate, School of Nursing, Shandong University, Jinan,

and poor quality of life.3,4 Previous studies have found

PR China. that adherence to self-care behaviors can prevent exacer-

Yanting Zhang, BSN, RN, MSN(c) bation and progression of HF and reduce the risk of

MSN Candidate, School of Nursing, Shandong University, Jinan, hospitalization and death.5,6 Nevertheless, self-care in

PR China.

patients with HF is inadequate because of physiolog-

Wenjie Fang, BM, RN, MSN(c)

MSN Candidate, School of Nursing, Shandong University, Jinan, ical and psychological factors, such as high comorbid

PR China. burden, sleep disturbances, impaired cognition, and

Xiuzhen Fan, PhD, RN depression.7Y9

Professor, School of Nursing, Shandong University, Jinan, PR China.

Given the previously mentioned situation, the ad-

This study was supported by Key Research and Development

Program of Shandong province (2016GSF201046).

herence behaviors of complex medication, dietary, and

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

self-care regimens require the assistance of family care-

Correspondence

givers.10 Family caregivers were defined as laypersons

Xiuzhen Fan, PhD, RN, School of Nursing, Shandong University, who provide unpaid care to a relative or friend to help

44 Wenhua Xi Rd, Jinan, Shandong 250012, PR China him/her take care of himself/herself.11 Family care-

(fxiuzhen@sdu.edu.cn).

givers as the proxy seem to be a fairly consistent substi-

DOI: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000398

tute for HF symptom assessment and management.12

576

Copyright © 2017 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Family Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of HF 577

Their decision making also contributed to self-care patients and informal caregivers.21,22 (2) Motivation:

maintenance and self-care confidence of patients with Perceived control and social support were regarded as

HF.13 Therefore, family caregivers are now considered personal motivation and social motivation, respectively,

as the members of healthcare team to assist patients in the hypothesized model. Perceived control was the

with health-promoting behaviors, medication adherence, self-generated belief or perception of control over

and symptom monitoring.14 Subsequently, Vellone et al11 cardiovascular-related health.23 It was found to be an

proposed that caregiver contribution to self-care of heart important contributing factor to lower caregiver burden

failure index (CC-SCHFI) was the extent to which a care- and better psychological status.24,25 Hence, perceived

giver contributed to a patient’s self-care maintenance and control might motivate family caregivers to make

management, as well as the caregiver’s confidence (self- contribution to self-care of HF. Social support was

efficacy) in his/her ability to contribute to the patient’s defined as ‘‘an exchange of resources between at least

self-care. The CC-SCHFI contains 3 dimensions: (1) care- two individuals perceived by the provider or the

giver contribution to self-care maintenance of HF index recipient to be intended to enhance the well-being of

(CC-SCHFI-maintenance), which included monitoring the recipient.’’26 It was reported that family caregivers

patient’s symptoms and adhering to treatment; (2) required social support from families, communities,

caregiver contribution to self-care management of HF and healthcare professionals.27 In addition, social sup-

index (CC-SCHFI-management), which included recog- port perceived by caregivers was significantly associ-

nizing patient’s signs and symptoms of HF exacerbation, ated with CC-SCHFI-management and caregiving

implementing actions, and evaluating implemented treat- burden.28,29 (3) Behavioral skills: Caregiver confidence

ment; and (3) caregiver confidence in contribution to self- in CC-SCHFI was viewed as self-efficacy, and CC-SCHFI-

care of HF index (caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI), maintenance was viewed as an objective skill in the hypo-

which evaluated caregivers’ confidence in their abilities to thesized model. In a previous study, caregiver confidence

assist patients to engage in each phase of the self-care in CC-SCHFI was the primary determinant of CC-

process. However, there are few studies that have explored SCHFI-maintenance and CC-SCHFI-management.30 (4)

CC-SCHFI with psychometrically sound instruments.15 Behavior: The CC-SCHFI-management represented as

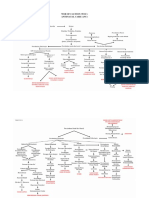

The Information-Motivation-Behavioral (IMB) skills behavior in the ditto model because the self-management of

model is a behavior-specific theoretical framework devel- HF was vital for disease management and prognosis.31

oped by Fisher et al.16 The Information-Motivation- Accordingly, this study aimed to explore the effects

Behavioral model emphasizes that the performance of a of HF knowledge (information), perceived control (per-

behavior requires information, motivation, and behav- sonal motivation), and social support (social motiva-

ioral skills. Information is accurate behavior-specific tion) on CC-SCHFI (behavioral skills and behavior).

knowledge. Motivation is an integrated function of The ditto model is presented in Figure 1.

personal motivation and social motivation. Personal

motivation reflects an individual’s attitude or belief, Methods

and social motivation rests on one’s perception of

Sample and Procedure

social support. Behavioral skills include one’s self-

efficacy and objective skills for performing the behav- A cross-sectional design was used in this study. The

ior. Individuals are more inclined to build behavior convenience sample of 247 dyads of eligible patients

skills with sufficient behavior-specific information and and their family caregivers were recruited from 3

motivation and then to engage in the targeted health cardiovascular units of a general university hospital in

behavior.17 The Information-Motivation-Behavioral China from October 2015 to May 2016. Permission to

model has been applied to predicting health-promoting conduct this study was obtained from the Medical

behaviors, such as diabetes medication adherence, Ethics Committee of the participating site. Each en-

healthy behaviors for metabolic syndrome, and preven- rolled patient and family caregiver received verbal

tion behaviors for sexually transmitted diseases.18Y20 information about the study and signed an informed

Because information, motivation, and behavioral skills are consent form.

also important factors in HF caregiving, the Information- All enrolled patients met the inclusion criteria: (1)

Motivation-Behavioral model could help to explain 18 years or older, (2) had a primary diagnosis of HF,

CC-SCHFI. and (3) had at least 1 primary family caregiver. Patients

According to the Information-Motivation-Behavioral were excluded if they had an acute coronary event in

model, we hypothesized that CC-SCHFI was explained 3 months before enrolment, a life-threatening disease,

by the following: (1) information: HF knowledge served or clear evidence of dementia. Each eligible patient

as information in the hypothesized model. It includes who agreed to participate in this study was asked to

accurate knowledge about HF (eg, pathogen, symptoms, appoint a primary family caregiver. The inclusion

medication, and diet selection), which was reported as a criteria of family caregivers were (1) 18 years or older,

determinant of self-care behavior in the perspective of (2) designated as a primary caregiver, (3) an unpaid

Copyright © 2017 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

578 Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing x November/December 2017

FIGURE 1. Hypothesized model of HF knowledge, perceived control, social support, and CC-SCHFI based on the Information-

Motivation-Behavioral model. Caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI, caregiver confidence in contribution to self-care of HF

index; CC-SCHFI, caregiver contribution to self-care of HF index; CC-SCHFI-maintenance, caregiver contribution to self-

care maintenance of HF index; CC-SCHFI-management, caregiver contribution to self-care management of HF index; HF,

heart failure.

person who provided the most informal care to the CC-SCHFI showed good internal consistency (9.80) and

patient, and (4) able to provide informed consent. test-retest reliability (9.90).14

All data were collected by a face-to-face interview

during the investigation. Among 247 dyads of eligible Heart Failure Knowledge

patients and family caregivers, 241 dyads completed Family caregivers’ HF knowledge was measured by

valid questionnaires, and 6 dyads were excluded the Chinese version of Heart Failure Knowledge Test.

because of missing data. The response rate was 96.8%. It was developed to assess the understanding of the

etiology of HF, symptoms of worsening HF, low-sodium

Measurements diet selection, medications, and self-management related

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics to weight monitoring, physical activity, and worsening

The demographic information of patients and family symptoms, for example, ‘‘Which of the following was

caregivers (age, gender, marital status, residence, edu- not the symptoms of HF?’’ 32 It consists of 10 single-

cational level, patient’s relationship with family care- choice questions, 2 multiple-choice questions, and 2 fill-

giver, and family caregiver living with the patient or in-the-blank items. One point is given for the correct

not) was obtained from the interview. Clinical charac- answer of each question. The number of correct answers is

teristics of the patients (New York Heart Association the total score. A higher score indicates a higher level of

class and duration of diagnosis) were obtained from HF knowledge, with a range from 0 to 14. In this study,

medical records. the Cronbach’s ! was .63.

Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of Heart Failure Perceived Control

The CC-SCHFI was measured using the Chinese Family caregivers’ perceived control was measured by

version of Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of Heart the Chinese version of Control Attitudes Scale-

Failure Index (CC-SCHFI) developed from the SCHFI Caregiver Version. The Control Attitudes Scale con-

v6.2.11 It is composed of 3 subscales with 22 items: CC- sists of 4 items: two about perceived control and two

SCHFI-maintenance (10 items, eg, ‘‘How often do you about helplessness, for example, ‘‘Regarding your

recommend to the person you care for to check weight?’’), family member’s heart problems, how much control

CC-SCHFI-management (6 items, eg, ‘‘If the person you or how helpless do you feel?’’33 The items for care-

care for has trouble breathing or ankle swelling, how likely givers are directed at the levels of control and help-

are you to recommend or do to reduce fluid intake?’’), lessness they perceive and how much control and

and caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI (6 items, eg, ‘‘In helplessness they think patients have. Response state-

reference to the person you care for, how confident are ments are scored from 1 (none) to 7 (very much). The

you that you can follow the given treatment advice?’’). The total score ranges from 4 to 28, with a higher score

standardized score for each subscale ranges from 0 to 100, reflecting greater perceived control. In this study, the

with a higher score indicating greater CC-SCHFI. The Cronbach’s ! was .74.

Copyright © 2017 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Family Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of HF 579

Social Support with patients. Most family caregivers (211, 87.5%)

Family caregivers’ social support was measured by the were spouses or adult children of patients.

Social Support Rating Scale, which has shown high

reliability and validity on a wide range of Chinese Mean Scores and Correlations of Construct

populations, including family caregivers of patients Variables

with chronic diseases.34,35 It contains 10 items and

measures 3 types of social supportVsubjective sup- As Table 2 presented, the mean scores for CC-SCHFI-

port (4 items; eg, I can ask my friends for help when maintenance, CC-SCHFI-management, and caregiver

things go wrong), objective support (3 items; eg, I can confidence in CC-SCHFI were 52.41 (9.96), 55.62

get economic assistance from family members, rela- (15.36), and 55.27 (16.38). The mean scores for HF

tives, friends, neighbors, or others when facing with knowledge, perceived control, and social support of

severe economic difficulties), and support availability family caregivers were 4.71 (2.11), 14.52 (4.62), and

(3 items; eg, I can communicate with others about my 41.84 (6.70). All scores for the previously mentioned

distress)Vto assess the various aspects of social support construct variables were significantly correlated with

individuals receive. These item scores are simply added each other (all Ps G .001), except the relationship between

up, with the total score ranging from 12 to 66. A higher HF knowledge and perceived control (r = 0.091, P 9 .05)

score indicates stronger social support received by the and the relationship between perceived control and

family caregiver. The Cronbach’s ! for this sample was .78. caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI (r = 0.115, P 9 .05).

Statistical Analyses Path Analysis of the Hypothesized Model

The SPSS version 20.0 for Windows (IBM Corp, The pathway of the final model was depicted in Figure 2.

Armonk, New York) was used to perform statistical After modification, the fit indices were acceptable:

analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize # 2 = 8.175, df = 4, # 2/df = 2.044 (P = .085); GFI, 0.989;

the demographics and clinical characteristics. The bi- AGFI, 0.942; TLI, 0.917; CFI, 0.978; and RMSEA, 0.066.

variate analysis provided the preliminary relationships

among construct variables of the hypothesis model. TABLE 1 Characteristics of Patients and Family

Subsequently, structural equation modeling was used Caregivers (N = 241 dyads)

to conduct path analyses of the hypothesis model using

Characteristics Patients Caregivers

SPSS Amos version 21.0. The # 2 test, goodness of fit

index (GFI), adjusted GFI (AGFI), Tucker-Lewis Index Age, mean (SD), y 62.71 (11.04) 48.40 (14.25)

Gender, n (%)

(TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square Male 126 (52.3) 108 (44.8)

error of approximation (RMSEA) were calculated as Female 115 (47.7) 133 (55.2)

the fit indices of the final model. A structural model Partnered, n (%)

had good data fit if the # 2 was nonsignificant (P 9 .05); Yes 213 (88.4) 227 (94.2)

the GFI, AGFI, TLI, and CFI approached 1.0; and No 28 (11.6) 14 (5.8)

Education, n (%)

RMSEA was less than 0.08.36 The significance level QHigh school 65 (27.0) 125 (51.9)

was set at .05 with a 2-tailed test. GHigh school 176 (73.0) 116 (48.1)

Residence, n (%)

Rural 114 (47.3) 85 (35.3)

Results Urban 127 (52.7) 156 (64.7)

Sample Characteristics Patient characteristics

NYHA class, n (%)

As shown in Table 1, on average, family caregivers II 148 (61.4)

were approximately 14.3 years younger than patients III 72 (29.9)

IV 21 (8.7)

with HF, and there was a slightly smaller proportion Duration of diagnosis, n (%), y

of men (108, 44.8%) as family caregivers as opposed G0.5 149 (61.8)

to patients (126, 52.3%). Most family caregivers (227, 0.5Y3 44 (18.3)

94.2%) and patients (213, 88.4%) had a partner. 93 48 (19.9)

Family caregivers were more educated than patients, Caregiver characteristics

Living with patient, n (%)

with 51.9% of them having at least high school edu- Yes 154 (63.9)

cation. A higher proportion of family caregivers lived No 87 (36.1)

in urban areas (156, 64.7%), when compared with Relationship with patient, n (%)

patients (127, 52.7%). Most patients (220, 91.3%) Spouse 102 (42.3)

had NYHA class II or III, and 149 patients (61.8%) Adult child 109 (45.2)

Other relationship 30 (12.5)

were given a diagnosis of HF within half a year. More

than half of family caregivers (154, 63.9%) were living Abbreviation: NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Copyright © 2017 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

580 Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing x November/December 2017

TABLE 2 Mean Scores and Correlations of Construct Variables (N = 241)

Variable Mean (SD) 1 2 3 4 5

1. HF knowledge 4.71 (2.11)

2. Perceived control 14.52 (4.62) 0.091

3. Social support 41.84 (6.70) 0.218b 0.149a

4. CC-SCHFI-maintenance 52.41 (9.96) 0.194b 0.181b 0.165b

5. CC-SCHFI-management 55.62 (15.36) 0.441b 0.244b 0.280b 0.343b

6. Caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI 55.27 (16.38) 0.334b 0.115 0.171a 0.309b 0.494b

Abbreviations: Caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI, caregiver confidence in contribution to self-care of HF index; CC-SCHFI, caregiver contribution to

self-care of HF index; CC-SCHFI-maintenance, caregiver contribution to self-care maintenance of HF index; CC-SCHFI-management, caregiver

contribution to self-care management of HF index; HF, heart failure.

a

P G .05.

b

P G .01.

The path coefficients were shown in Table 3. As ex- and social support on CC-SCHFI with psychometri-

pected, CC-SCHFI-maintenance was positively influ- cally sound instruments.

enced by perceived control (" = .148, P = .015) and In this study, family caregivers’ HF knowledge had

caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI (" = .293, P G indirect effects on CC-SCHFI-maintenance, both di-

.001). The CC-SCHFI-management was positively rect and indirect effects on CC-SCHFI-management,

influenced by HF knowledge (" = .270, P G .001), and direct effects on caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI.

perceived control (" = .140, P = .007), social support A previous study found that HF knowledge was

(" = .123, P = .019), caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI necessary but insufficient for effective self-care behav-

(" = .328, P G .001), and CC-SCHFI-maintenance (" = iors in patients and caregivers.37 Most patients and

.148, P = .006). Caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI caregivers expressed that healthcare providers

was positively influenced by HF knowledge (" = .334, explained inadequate knowledge about HF, such as

P G .001). The final model accounted for 24.6% of the its causes, symptoms, and medications, which was one

variance in CC-SCHFI-maintenance, 67.6% of the var- of the barriers to performing HF care.38 Although

iance in CC-SCHFI-management, and 33.4% of the patients could often recall healthcare providers’ self-

variance in caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI. care information, they were unable to integrate the

practices into their daily lives.39 Therefore, theme-

Discussion based transitional care should include providing patients

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to and family caregivers with practical skills and services

find the effects of HF knowledge, perceived control, to promote knowledge and engagement in self-care and

FIGURE 2. The final model of HF knowledge, perceived control, social support, and CC-SCHFI based on the Information-

Motivation-Behavioral model. Caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI, caregiver confidence in contribution to self-care of HF

index; CC-SCHFI, caregiver contribution to self-care of HF index; CC-SCHFI-maintenance, caregiver contribution to self-

care maintenance of HF index; CC-SCHFI-management, caregiver contribution to self-care management of HF index; HF,

heart failure. Bold lines indicate significant regression paths. Dotted lines indicate nonsignificant regression paths. aP G .05.

b

P G .01. cP G .001.

Copyright © 2017 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Family Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of HF 581

TABLE 3 The Path Coefficients of the Final Model (N = 241)

Path b " SE P

CC-SCHFI-maintenance @ perceived control 0.128 .148 0.052 .015

CC-SCHFI-maintenance @ caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI 0.296 .293 0.062 G.001

CC-SCHFI-management @ HF knowledge 0.494 .270 0.101 G.001

CC-SCHFI-management @ perceived control 0.117 .140 0.044 .007

CC-SCHFI-management @ social support 0.071 .123 0.030 .019

CC-SCHFI-management @ caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI 0.323 .328 0.055 G.001

CC-SCHFI-management @ CC-SCHFI-maintenance 0.144 .148 .053 .006

Caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI @ HF knowledge 0.621 .334 0.113 G.001

Abbreviations: b, regression coefficient; ", standard regression coefficient; Caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI, caregiver confidence in contribution to

self-care of HF index; CC-SCHFI, caregiver contribution to self-care of HF index; CC-SCHFI-maintenance, caregiver contribution to self-care

maintenance of HF index; CC-SCHFI-management, caregiver contribution to self-care management of HF index; HF, heart failure; SE, standard error.

stimulate active communication with healthcare In this study, there was no direct relationship

providers.40 between HF knowledge and CC-SCHFI-maintenance.

Perceived control of family caregivers directly affected However, we found that the relationship was totally

CC-SCHFI-maintenance and both directly and indirectly mediated by caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI. This

affected CC-SCHFI-management. Caregivers’ perceived finding is of importance because it suggests that inter-

control about their family member’s heart problem was ventions on increasing family caregivers’ HF knowl-

a positive and important factor in the impact of care- edge may improve CC-SCHFI-maintenance through

giving.41 In the previous studies, HF spouses or other strengthening caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI. To

family members with higher perceived control had our knowledge, this mediating effect of caregiver con-

less caregiver burden, higher emotional well-being, and fidence in CC-SCHFI has not been reported among

less emotional stress (eg, anxiety, depression, and family caregivers of patients with HF.

hostility).24,25,42,43 Therefore, interventions designed We also found that perceived control of family

specifically to increase the degree of perceived control caregivers had no direct effect on caregiver confidence

related to their caregiving tasks, caregiving burden, and in CC-SCHFI. It is not in accordance with a previous

emotional status might improve CC-SCHFI-maintenance study on patients with HF, which reported that the

and CC-SCHFI-management. stronger perception of internal health control, the

Social support of family caregivers only directly higher confidence in the process of the management

influenced CC-SCHFI-management. This was con- of HF.45 It may result from the incongruence in

sistent with that better perceived social support for confidence of patient and caregiver contributions to

caregivers was significantly associated with greater HF self-care.46 Furthermore, the determinants of con-

CC-SCHFI-management.29 Although social support tribution to self-care of HF were not completely

from relatives, friends, and colleagues improved the identical in patient-caregiver dyadic.29,47 In our study,

prognosis of patients with heart disease, their family family caregivers’ social support did not directly influ-

caregivers who experienced mental distress (eg, ence CC-SCHFI-maintenance. It is in line with the

caregiving stress, depression) also need emotional finding that social support was not the significant

support from others.44 In addition, the perceived social determinant of CC-SCHFI-maintenance in family

support of family caregivers effectively reduced the caregivers of patients with HF.29 Family caregivers’

caregiving burden.28 A qualitative study reported that social support was also found to have no direct

family caregivers with lower social support perceived influence on caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI in the

their caregiver role as more burdensome and boring or current study. It is comparable with the finding that

less rewarding than caregivers with higher social there was no effect of social support on confidence

support.41 for physical activity in family caregivers of cancer

In this study, the caregiver confidence in CC-SCHFI survivors.48 Given the less evidence on CC-SCHFI,

had direct effects on caregiver CC-SCHFI-maintenance further investigation is warranted.

and both direct and indirect effects on CC-SCHFI-

management. This was consistent with that caregiver

Limitations

confidence in CC-SCHFI was the primary determinant of

CC-SCHFI-maintenance and CC-SCHFI-management.30 This study also has limitations. This was an analysis of

In addition, the CC-SCHFI-maintenance had direct ef- cross-sectional data, which allowed only the identifi-

fects on CC-SCHFI-management. These findings indi- cation of correlates or determinants of CC-SCHFI.

cated that the CC-SCHFI-management might be Future studies should use a longitudinal design to

improved through interventions targeted at caregiver identify true predictors of CC-SCHFI. In addition,

confidence and CC-SCHFI-maintenance. the findings are generalized to other countries with

Copyright © 2017 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

582 Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing x November/December 2017

4. Foebel AD, Heckman GA, Ji K, et al. Heart failureYrelated

What’s New and Important mortality and hospitalization in the year following admis-

sion to a long-term care facility: the Geriatric Outcomes

h Family caregivers’ HF knowledge, perceived and Longitudinal Decline in Heart Failure (GOLD-HF)

control, and social support were positively associated Study. J Card Fail. 2013;19(7):468Y477.

with caregiver contribution to self-care of HF index 5. Riegel B, Dickson VV. A situation-specific theory of heart

(CC-SCHFI). failure self-care. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23(3):190Y196.

h Both caregiver confidence in contribution to self-care 6. Moser DK, Dickson V, Jaarsma T, et al. Role of self-care in

and CC-SCHFI-maintenance positively influenced the patient with heart failure. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2012;14(3):

CC-SCHFI-management. 265Y275.

h The Information-Motivation-Behavioral modelYbased 7. Riegel B, Moelter ST, Ratcliffe SJ, et al. Excessive daytime

interventions strengthening HF knowledge, perceived sleepiness is associated with poor medication adherence in

control, and social support might improve family adults with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2011;17(4):340Y348.

CC-SCHFI. 8. Harkness K, Heckman GA, Akhtar-Danesh N, et al. Cog-

nitive function and self-care management in older patients

with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;13(3):

caution because our sample only included Chinese 277Y284.

family caregivers of patients with HF. Sociocultural 9. Dickson VV, Buck H, Riegel B. A qualitative meta-analysis

aspects might influence how family caregivers take care of heart failure self-care practices among individuals with

of their loved ones. multiple comorbid conditions. J Card Fail. 2011;17(5):413Y419.

10. Berg CA, Upchurch R. A developmental-contextual model

of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life

Conclusions span. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(6):920Y954.

11. Vellone E, Riegel B, Cocchieri A, et al. Validity and reli-

The Information-Motivation-Behavioral model was ability of the caregiver contribution to self-care of heart failure

used as a framework to evaluate critical prerequisites index. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;28(3):245Y255.

to promote CC-SCHFI in this study. Heart failure 12. Quinn C, Dunbar SB, Higgins M. Heart failure symptom

assessment and management: can caregivers serve as proxy?

knowledge, perceived control, and social support were J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25(2):142Y148.

contributors to CC-SCHFI. The higher caregiver confi- 13. Sebern M, Riegel B. Contributions of supportive relation-

dence in CC-SCHFI and better CC-SCHFI-maintenance ships to heart failure self-care. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;

were linked to greater CC-SCHFI-management. There- 8(2):97Y104.

fore, Information-Motivation-Behavioral modelYbased 14. Ahmad FS, Barg FK, Bowles KH, et al. Comparing per-

spectives of patients, caregivers, and clinicians on heart failure

interventions or tailored educational programs might management. J Card Fail. 2015;22(3):210Y217.

include strategies to ensure that family caregivers pos- 15. Buck HG, Harkness K, Wion R, et al. Caregivers’ contri-

sess appropriate knowledge of HF. Motivation might be butions to heart failure self-care: a systematic review. Eur

enhanced by targeting family caregivers’ perceived J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;14(1):79Y89.

control of HF and social support from family members 16. Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Misovich SJ, et al. Changing AIDS

risk behavior: effects of an intervention emphasizing AIDS

and healthcare services. These interventions would risk reduction information, motivation, and behavioral

effectively improve the behavioral skills and behavior skills in a college student population. Health Psychol. 1996;

in CC-SCHFI. 15(2):114Y123.

17. Suls J, Wallston KA. Chapter 4. The Information-Motivation-

Behavioral Skills Model: A General Social Psychological

Acknowledgments Approach to Understanding and Promoting Health Behavior.

Social Psychological Foundations of Health and Illness.

The authors thank the staff of cardiovascular units of Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2009.

the hospital who gave them permission to recruit pa- 18. Mayberry LS, Osborn CY. Empirical validation of the

tients and family caregivers for the study and patients information-motivation-behavioral skills model of diabe-

tes medication adherence: a framework for intervention.

and family caregivers who willingly agreed to partic- Diabetes Care. 2014;37(5):1246Y1253.

ipate in this study. 19. Mohsen B, Stein JA, Shahrzad BH, et al. Using the

information-motivation-behavioral model to predict sexual

behavior among underserved minority youth. J Sch Health.

REFERENCES 2010;80(6):287Y295.

1. Farid N, Konrad J, Dobson AJ. Understanding the ‘‘epi- 20. Lee G, Yang SJ, Chee YK. Assessment of healthy behaviors

demic of heart failure’’: a systematic review of trends in deter- for metabolic syndrome among Korean adults: a modified

minants of heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11(5): information-motivation-behavioral skills with psychologi-

472Y479. cal distress. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:518.

2. Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Forecasting the 21. Browne S, Macdonald S, May CR, et al. Patient, carer and

impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy state- professional perspectives on barriers and facilitators to qual-

ment from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart ity care in advanced heart failure. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):

Fail. 2013;6(3):606Y619. e93288.

3. Graven LJ, Grant JS. Coping and health-related quality of 22. Collins S. Statutory social workers: stress, job satisfaction,

life in individuals with heart failure: an integrative review. coping, social support and individual differences. Br J Soc

Heart Lung. 2013;42(3):183Y194. Work. 2008;38(6):1173Y1193.

Copyright © 2017 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Family Caregiver Contribution to Self-care of HF 583

23. Wallston KA, Wallston BS, Smith S, et al. Perceived control 36. Bagozzi RP, Yi Y. On the evaluation of structural equation

and health. Curr Psychol. 1987;6(1):5Y25. models. J Acad Mark Sci. 1988;16(1):74Y94.

24. Agren S, Evangelista L, StrPmberg A. Do partners of pa- 37. Clark AM, Freydberg CN, McAlister FA, et al. Patient and

tients with chronic heart failure experience caregiver bur- informal caregivers’ knowledge of heart failure: necessary

den? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;9(4):254Y262. but insufficient for effective self-care. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;

25. Chung ML, Pressler SJ, Dunbar SB, et al. Predictors of 11(6):617Y621.

depressive symptoms in caregivers of patients with heart 38. Kaholokula JK, Saito E, Mau MK, et al. Pacific Islanders’

failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25(5):411Y419. perspectives on heart failure management. Patient Educ

26. Shumaker SA, Brownell A. Toward a theory of social sup- Couns. 2008;70(2):281Y291.

port: closing conceptual gaps. J Soc Issues. 2010;40(40): 39. Spaling MA, Currie K, Strachan PH, Harkness K, Clark AM.

11Y36. Improving support for heart failure patients: a systematic

27. Cameron J, Rhodes KL, Ski CF, et al. Carers’ views on pa- review to understand patients’ perspectives on self-care.

tient self-care in chronic heart failure. J Clin Nurs. 2016; J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(11):2478Y2489.

25(1Y2):144Y152. 40. Albert NM. A systematic review of transitional-care

28. Lee CC, Czaja SJ, Schulz R. The moderating influence of strategies to reduce rehospitalization in patients with heart

demographic characteristics, social support, and religious failure. Heart Lung. 2016;45(2):100Y113.

coping on the effectiveness of a multicomponent psycho- 41. Hwang B, Fleischmann KE, Howie-Esquivel J, et al.

social caregiver intervention in three racial ethnic groups. Caregiving for patients with heart failure: impact on

J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65B(2):185Y194. patients’ families. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20(6):431Y441.

29. Bidwell JT, Vellone E, Lyons KS, et al. Determinants of heart 42. Dracup K, Evangelista LS, Doering L, et al. Emotional

failure self-care maintenance and management in patients well-being in spouses of patients with advanced heart

and caregivers: a dyadic analysis. Res Nurs Health. 2015; failure. Heart Lung. 2004;33(6):354Y361.

38(5):392Y402. 43. Dracup K, Westlake C, Erickson VS, et al. Perceived con-

30. Vellone E, D’Agostino F, Buck HG, et al. The key role of trol reduces emotional stress in patients with heart failure.

caregiver confidence in the caregiver’s contribution to self- J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22(1):90Y93.

care in adults with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 44. Barth J, Schneider S, von K.nel R. Lack of social support in

2014;14(5):372Y381. the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: a

31. Ditewig JB, Blok H, Havers J, et al. Effectiveness of self- systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2010;

management interventions on mortality, hospital read- 72(3):229Y238.

missions, chronic heart failure hospitalization rate and quality 45. Siennicka AE, Govcicska-Bis K, Wilczek J, et al. Percep-

of life in patients with chronic heart failure: a systematic tion of health control and self-efficacy in heart failure.

review. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(3):297Y315. Kardiol Pol. 2016;74(2):168Y178.

32. Artinian NT, Magnan M, Sloan M, et al. Self-care behav- 46. Lee CS, Vellone E, Lyons KS, et al. Patterns and predic-

iors among patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2002; tors of patient and caregiver engagement in heart failure

31(31):161Y172. care: a multi-level dyadic study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(2):

33. )restedt K, )gren S, Flemme I, et al. A psychometric 588Y597.

evaluation of the four-item version of the Control Attitudes 47. Vellone E, Bidwell JT, Lyons KS, et al. Patient-caregiver

Scale for patients with cardiac disease and their partners. dyadic determinants of self-care maintenance and self-care

Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;14(4):317Y325. management in heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;

34. Yin Shaohua, Wan Lihong, Yang W. The relationship be- 14:S73YS74.

tween anticipated needs and social support in caregivers 48. Barber FD. Effects of social support on physical activity,

of stroke survivors. Int J Nurs. 2012;31(5):781Y783. self-efficacy, and quality of life in adult cancer survivors

35. Liu J, Li F, Lian Y. Investigation of reliability and val idity of and their caregivers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(5):

the social support scale. J Xinjiang Med Univ. 2008;31(1):1Y3. 481Y489.

Copyright © 2017 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Вам также может понравиться

- Hls 11 s1 11179Документ4 страницыHls 11 s1 11179mutiaОценок пока нет

- JHPN 24 E151Документ8 страницJHPN 24 E151MentiEndah dwi SeptianiОценок пока нет

- Fredriksen 2011Документ8 страницFredriksen 2011Yusshy HerlianiОценок пока нет

- Finding the Path in Alzheimer’s Disease: Early Diagnosis to Ongoing Collaborative CareОт EverandFinding the Path in Alzheimer’s Disease: Early Diagnosis to Ongoing Collaborative CareОценок пока нет

- Mathew 2017Документ6 страницMathew 2017GodlipОценок пока нет

- Drivers of Moral Distress in Surgical Intensive Care Providers: A Mixed Methods StudyДокумент8 страницDrivers of Moral Distress in Surgical Intensive Care Providers: A Mixed Methods StudyLisbeth Gaete CórdovaОценок пока нет

- Inpatient Geriatric Psychiatry: Optimum Care, Emerging Limitations, and Realistic GoalsОт EverandInpatient Geriatric Psychiatry: Optimum Care, Emerging Limitations, and Realistic GoalsHoward H. FennОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S2352013217303046 MainДокумент6 страниц1 s2.0 S2352013217303046 Mainsuparna singhОценок пока нет

- Hudson2010 Article ASystematicReviewOfPsychosociaДокумент6 страницHudson2010 Article ASystematicReviewOfPsychosociaDian Oktaria SafitriОценок пока нет

- Social Support and DepressionДокумент6 страницSocial Support and Depressionarifrahman.fikОценок пока нет

- Integrative Medicine for Vulnerable Populations: A Clinical Guide to Working with Chronic and Comorbid Medical Disease, Mental Illness, and AddictionОт EverandIntegrative Medicine for Vulnerable Populations: A Clinical Guide to Working with Chronic and Comorbid Medical Disease, Mental Illness, and AddictionОценок пока нет

- PIIS2347562522002268Документ9 страницPIIS2347562522002268Maria FreitasОценок пока нет

- Research: Burden of Care Amongst Caregivers Who Are First Degree Relatives of Patients With SchizophreniaДокумент10 страницResearch: Burden of Care Amongst Caregivers Who Are First Degree Relatives of Patients With SchizophreniaLusiaОценок пока нет

- Implementation of Perinatal Collaborative Care A Health Services Approach To Perinatal Depression CareДокумент9 страницImplementation of Perinatal Collaborative Care A Health Services Approach To Perinatal Depression CaresalamahОценок пока нет

- HHS Public AccessДокумент29 страницHHS Public AccessTrisna SariОценок пока нет

- Zhou 2016 Comparison of Burden Among FamilyДокумент10 страницZhou 2016 Comparison of Burden Among FamilyVuong NgОценок пока нет

- Factors Affecting The Attitudes of Nurses Towards Palliative Care in The Acute and Long Term Care Setting: A Systematic ReviewДокумент69 страницFactors Affecting The Attitudes of Nurses Towards Palliative Care in The Acute and Long Term Care Setting: A Systematic ReviewfiennesrnОценок пока нет

- Family Dynamics and Psychological Well-Being in Caregivers To Those With Mild Cognitive ImpairmentДокумент1 страницаFamily Dynamics and Psychological Well-Being in Caregivers To Those With Mild Cognitive ImpairmentCristina MPОценок пока нет

- Enhancing Patient Engagement in Pulmonary Healthcare - The Art and Science-Springer International Publishing - Humana (2020)Документ299 страницEnhancing Patient Engagement in Pulmonary Healthcare - The Art and Science-Springer International Publishing - Humana (2020)Frederico PóvoaОценок пока нет

- Nursing Care (Palliative Medicine) in Patients With Neuropsychiatric DisordersДокумент6 страницNursing Care (Palliative Medicine) in Patients With Neuropsychiatric Disordersdedi kurniawanОценок пока нет

- Improving Attitudes and Perceptions About End-of-Life Nursing On A Hospital-Based Palliative Care UnitДокумент8 страницImproving Attitudes and Perceptions About End-of-Life Nursing On A Hospital-Based Palliative Care UnitSERGIO ANDRES CESPEDES GUERREROОценок пока нет

- Mediation Role of Perceived Social Support Between Recurrence Risk Perception and Health Behaviour Among Patients With Stroke in China: A Cross-Sectional StudyДокумент8 страницMediation Role of Perceived Social Support Between Recurrence Risk Perception and Health Behaviour Among Patients With Stroke in China: A Cross-Sectional Studystardust.m002Оценок пока нет

- Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice in Management of Patients With Mental Health Disorders in Emergency Departments in Makkah Region of Saudi ArabiaДокумент8 страницKnowledge, Attitude, and Practice in Management of Patients With Mental Health Disorders in Emergency Departments in Makkah Region of Saudi ArabiaIJAR JOURNALОценок пока нет

- A Qualitative Investigation of The ImpactДокумент5 страницA Qualitative Investigation of The ImpactFelipe Fernández PérezОценок пока нет

- The Effectiveness of Psych interventions-CHF 2018Документ10 страницThe Effectiveness of Psych interventions-CHF 2018Bob JoeОценок пока нет

- Multimodal Treatment of Acute Psychiatric Illness: A Guide for Hospital DiversionОт EverandMultimodal Treatment of Acute Psychiatric Illness: A Guide for Hospital DiversionОценок пока нет

- Measures of Psychological Stress and Physical Health in Family Caregivers of Stroke Survivors A Literature ReviewДокумент11 страницMeasures of Psychological Stress and Physical Health in Family Caregivers of Stroke Survivors A Literature ReviewaОценок пока нет

- Lau 2021Документ12 страницLau 2021Kevin LunaОценок пока нет

- Meaning in Life and Its Relationship With Family Cohesion: A Survey of Palliative Care Patients in ChinaДокумент15 страницMeaning in Life and Its Relationship With Family Cohesion: A Survey of Palliative Care Patients in Chinacheatingw995Оценок пока нет

- Family Practice 2006 Sayers 317 24Документ8 страницFamily Practice 2006 Sayers 317 24Giffari AnugrahОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S1836955319300578 MainДокумент12 страниц1 s2.0 S1836955319300578 MainSairam PhysioОценок пока нет

- Accepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.02.014Документ19 страницAccepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.02.014Rezky PradessetyaОценок пока нет

- Inm 12433Документ14 страницInm 12433leticiaОценок пока нет

- Article 6Документ4 страницыArticle 6Rumela Ganguly ChakrabortyОценок пока нет

- Cuidados PaliativosДокумент11 страницCuidados PaliativosALEJANDRAОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Guided Care TeamsДокумент7 страницThe Effect of Guided Care TeamsHuzi SidОценок пока нет

- Guide to Intellectual Disabilities: A Clinical HandbookОт EverandGuide to Intellectual Disabilities: A Clinical HandbookJulie P. GentileОценок пока нет

- Home Health Nurses' Perspectives and Care Processes Related To Older Persons With Frailty and Depression: A Mixed Method Pilot StudyДокумент20 страницHome Health Nurses' Perspectives and Care Processes Related To Older Persons With Frailty and Depression: A Mixed Method Pilot StudyFitriani WidyastantiОценок пока нет

- Research ArticleДокумент7 страницResearch ArticleleticiaОценок пока нет

- Tugas 1Документ10 страницTugas 1Siti QomariaОценок пока нет

- Supporting and Empowering People With Epilepsy Contribution of The Epilepsy Specialist NursesДокумент8 страницSupporting and Empowering People With Epilepsy Contribution of The Epilepsy Specialist Nursescelia.longuetОценок пока нет

- Brief Analysis On Perspective of Cancer Patients and Healthcare Professionals Towards Home-Based Care - A Systematic ReviewДокумент27 страницBrief Analysis On Perspective of Cancer Patients and Healthcare Professionals Towards Home-Based Care - A Systematic ReviewAaron LeeОценок пока нет

- Dan - Patinet ReluctanceДокумент6 страницDan - Patinet Reluctanceamandeep khuranaОценок пока нет

- The Factors Associated With Depression in Schizophrenia Patients: The Role of Self-Efficacy, Self-Esteem, Hope and ResilienceДокумент14 страницThe Factors Associated With Depression in Schizophrenia Patients: The Role of Self-Efficacy, Self-Esteem, Hope and ResilienceArif IrpanОценок пока нет

- Attitudes of Nursing Home Staff 2013Документ15 страницAttitudes of Nursing Home Staff 2013fiennesrnОценок пока нет

- Psychological Care of The FamiДокумент16 страницPsychological Care of The FamiZafar Imam KhanОценок пока нет

- Family Meetings at End of Life: A Systematic ReviewДокумент10 страницFamily Meetings at End of Life: A Systematic ReviewSERGIO ANDRES CESPEDES GUERREROОценок пока нет

- Anticipated Stigma and Healthcare UtilizationДокумент6 страницAnticipated Stigma and Healthcare UtilizationAbraham RumayaraОценок пока нет

- Psychosocial Interventions For Informal Caregivers of Palliative Cancer PatientsДокумент6 страницPsychosocial Interventions For Informal Caregivers of Palliative Cancer PatientsMaria VasquezОценок пока нет

- HIV Prevention in Primary Care Practice: A PrEP PrimerОт EverandHIV Prevention in Primary Care Practice: A PrEP PrimerОценок пока нет

- Fertiliy in Cancer Model of CareДокумент9 страницFertiliy in Cancer Model of CareFlorinaОценок пока нет

- Prevalence and Correlates of Psychiatric Morbidity in Egyptian Sample of Dementia Patients ' Caregivers: A Comparative Descriptive StudyДокумент11 страницPrevalence and Correlates of Psychiatric Morbidity in Egyptian Sample of Dementia Patients ' Caregivers: A Comparative Descriptive Studywishfairy67Оценок пока нет

- Patterns of Psychologists Interprofessional Collaboration AcrossДокумент26 страницPatterns of Psychologists Interprofessional Collaboration AcrossLNNGAОценок пока нет

- Epilepsy & Behavior: Shanna M. Guilfoyle, Sally Monahan, Cindy Wesolowski, Avani C. ModiДокумент6 страницEpilepsy & Behavior: Shanna M. Guilfoyle, Sally Monahan, Cindy Wesolowski, Avani C. ModiJhonny BatongОценок пока нет

- Igx004 2993Документ1 страницаIgx004 2993Arifah Budiarti NurfitriОценок пока нет

- Self CareДокумент10 страницSelf CareperisaОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Family Appraisal On Caregiver Burden in Family Caregiver of Female Cancer PatientsДокумент8 страницThe Effect of Family Appraisal On Caregiver Burden in Family Caregiver of Female Cancer PatientsIJPHSОценок пока нет

- International Journal of Nursing Studies: Qi Lu, Jan Mårtensson, Yue Zhao, Linda JohanssonДокумент8 страницInternational Journal of Nursing Studies: Qi Lu, Jan Mårtensson, Yue Zhao, Linda JohanssonAbdul HadiОценок пока нет

- Appi Ajp 2009 09050691Документ9 страницAppi Ajp 2009 09050691Dilfera HermiatiОценок пока нет

- Warta 17 - 4 - 2022 (Hari Raya Paskah)Документ2 страницыWarta 17 - 4 - 2022 (Hari Raya Paskah)Velicia MargarethaОценок пока нет

- Matriks Perencanaan Program Panitia Perta Pelindung Paroki Yang Ke - 33Документ4 страницыMatriks Perencanaan Program Panitia Perta Pelindung Paroki Yang Ke - 33Velicia MargarethaОценок пока нет

- A Modified Supine Position Facilitates Bladder Function in Patient Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary InterventionДокумент8 страницA Modified Supine Position Facilitates Bladder Function in Patient Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary InterventionVelicia MargarethaОценок пока нет

- Effects of Static Stretching Exercise On Lumbar Flexibility and Central Arterial StiffnessДокумент7 страницEffects of Static Stretching Exercise On Lumbar Flexibility and Central Arterial StiffnessVelicia MargarethaОценок пока нет

- Web of Caution (Woc) Antenatal Care (Anc)Документ3 страницыWeb of Caution (Woc) Antenatal Care (Anc)Velicia MargarethaОценок пока нет

- Changes in Hospital Competitive StrategyДокумент23 страницыChanges in Hospital Competitive Strategyanantomi100% (1)

- Continuing Competency Log PrintДокумент2 страницыContinuing Competency Log PrintBobОценок пока нет

- ArthritisДокумент5 страницArthritismeenuОценок пока нет

- Doctor of Medicine - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaДокумент9 страницDoctor of Medicine - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaAlexis SinghОценок пока нет

- Nhs FPX 4000 Assessment 1 Applying Ethical PrinciplesДокумент5 страницNhs FPX 4000 Assessment 1 Applying Ethical Principleszadem5266Оценок пока нет

- Capa Plan 2018Документ3 страницыCapa Plan 2018Cha Gabriel100% (2)

- MDR 010256550690Документ1 страницаMDR 010256550690mathhew bepplerОценок пока нет

- CMS DRGДокумент14 страницCMS DRGSean RОценок пока нет

- Mary - Letter of RecommendationДокумент1 страницаMary - Letter of Recommendationapi-315592452Оценок пока нет

- Indian Diagnostic Market AnalysisДокумент2 страницыIndian Diagnostic Market Analysisradheshyam08Оценок пока нет

- NYS Office of Professional Conduct Opens Investigation of Controversial Psychiatrist Kelly Brogan (11/24/20) + My Complaint Re: Her License (3/22/20)Документ5 страницNYS Office of Professional Conduct Opens Investigation of Controversial Psychiatrist Kelly Brogan (11/24/20) + My Complaint Re: Her License (3/22/20)Peter M. Heimlich100% (1)

- Reducing Restrictive Practices To Control Aggressive Behaviors in Young Novel Psychoactive Substance UsersДокумент25 страницReducing Restrictive Practices To Control Aggressive Behaviors in Young Novel Psychoactive Substance UsersMimeroseОценок пока нет

- Professional Baby Health Record BookДокумент8 страницProfessional Baby Health Record BookMatthew CalaraОценок пока нет

- Unit Secretary ResumeДокумент6 страницUnit Secretary Resumeaflkuapdc100% (1)

- List of 2 Years AffiliationДокумент15 страницList of 2 Years AffiliationAahad AmeenОценок пока нет

- Kajang ScriptДокумент6 страницKajang ScriptK EV INОценок пока нет

- A History of Nurses Charged With Killing PatientsДокумент2 страницыA History of Nurses Charged With Killing PatientsBrayen SabapatheeОценок пока нет

- Biopsychosocial Model of HealthДокумент10 страницBiopsychosocial Model of Healthzainabnoor100% (2)

- Doug Ford Letter To Ontario Hospital CEOsДокумент5 страницDoug Ford Letter To Ontario Hospital CEOsSunny CynthiaОценок пока нет

- ��تجميعات الفارما�Документ4 страницы��تجميعات الفارما�Turky TurkyОценок пока нет

- Business Plan Assignment 2.editedДокумент5 страницBusiness Plan Assignment 2.editedclerk scooperОценок пока нет

- You Are Dangerous To Your Health CRAWFORDДокумент18 страницYou Are Dangerous To Your Health CRAWFORDGonzalo PaezОценок пока нет

- CH 1 Quiz Results CPC AAPCДокумент3 страницыCH 1 Quiz Results CPC AAPCBrenda MedinaОценок пока нет

- Public Health Nursing Population Centered Health Care in The Community 9th Edition Stanhope Test BankДокумент12 страницPublic Health Nursing Population Centered Health Care in The Community 9th Edition Stanhope Test BankMichaelTraniftmz100% (20)

- Oxford: ReferenceДокумент846 страницOxford: ReferenceNMC NEPHROLOGY100% (1)

- Nursing ProcessДокумент5 страницNursing Processanimesh pandaОценок пока нет

- Securing and Protecting Patient Data - TCS PDFДокумент15 страницSecuring and Protecting Patient Data - TCS PDFMassimo RiserboОценок пока нет

- Docs in PuneДокумент238 страницDocs in Punemenolove100% (1)

- Outline of Nursing Care Plan: 1. Hyperthermia Hyperthermia Associated With High FeverДокумент2 страницыOutline of Nursing Care Plan: 1. Hyperthermia Hyperthermia Associated With High FeverFarah FildzahОценок пока нет

- Legal Aspects of Medical RecordsДокумент14 страницLegal Aspects of Medical Recordsneeta rajesh bhide50% (4)