Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

York ST On Strand Kennedy 1996

Загружено:

Aracely Valentina ÖОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

York ST On Strand Kennedy 1996

Загружено:

Aracely Valentina ÖАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/275159357

Comprehensibility of Dysarthric Speech

Article in American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology · February 1996

DOI: 10.1044/1058-0360.0501.55

CITATIONS READS

30 2,791

3 authors, including:

Edythe Strand Mary Kennedy

Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN Chapman University

118 PUBLICATIONS 2,039 CITATIONS 58 PUBLICATIONS 1,371 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Childhood Apraxia of Speech View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Mary Kennedy on 29 November 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Tutorial

Comprehensibility of Dysarthric Speech:

Implications for Assessment and Treatment

Planning

Kathryn M. Yorkston

Edythe A. Strand

Mary R.T. Kennedy

University of Washington, Seattle

This paper describes the concept of model of chronic disease as a factor in disability

comprehensibility and how it is an important affecting speech performance in physical and/or

construct in the assessment and treatment of social contexts. The literature related to

dysarthric speech. Intelligibility and comprehen- comprehensibility of dysarthric speech is

sibility are differentiated in terms of their reviewed. Clinical approaches to improving

definition, measurement, and approaches to comprehensibility, including issues of candi-

treatment. Specifically, comprehensibility is dacy, intervention planning, and treatment

defined within the World Health Organization approaches, are discussed.

T

he term comprehensibility has been applied to words or sentences. Second, the transmission system will

measurement of the adequacy of communication in impact intelligibility of the utterance. For example, live

a number of populations, including speakers of voice will often yield higher intelligibility scores than

English as a second language and individuals with hearing transcriptions of tape-recorded utterances. Finally, the

impairment. Barefoot and colleagues (Barefoot, Bochner, listener’s task will influence intelligibility scores. For

Johnson, & vom Eigen, 1993) suggest that comprehensibil- example, forced-choice word selection and sentence

ity can be defined as “the extent to which a listener completion will yield higher scores than orthographic

understands utterances produced by a speaker in a commu- transcription.

nication context” (p. 32). The notion of communicative The concepts of comprehensibility and intelligibility

context is not new. Miller and Selfridge (1950) suggest that may be distinguished by the fact that comprehensibility

total context includes the sum of all conditions surrounding incorporates signal-independent information such as

a communication event. It is the knowledge shared by the syntax, semantics, and physical context. Figures 1 and 2

communication partners about the time, place, topic, illustrate the distinction between speech intelligibility and

purpose, or any other feature of the setting in which the comprehensibility as applied to the area of dysarthria. A

utterance occurs. review of Figure 1 suggests that speech intelligibility is a

Those who conduct clinical research in dysarthria have measure of the adequacy of the acoustic signal. It is the

focused more on intelligibility than on comprehensibility. product of at least two components. The first component is

The term intelligibility refers to the degree to which the the impairment or the disordered speech production

acoustic signal (the utterance produced by the dysarthric mechanism. The second component represents compensa-

speaker) is understood by a listener. Intelligibility is tory strategies the speaker employs in response to the

typically measured by having listeners orthographically impairment. When intelligibility is measured in the clinical

transcribe words or sentences that the speaker reads. An setting, all other signal-independent information is held

intelligibility score is then computed by dividing the constant. For example, information such as semantic

number of words understood by the total number of words context provided in the natural communication environ-

spoken. Because many factors influence intelligibility, a ment is removed by using standard or randomly selected

number of aspects of measurement are typically controlled words and sentences. Measures of speech intelligibility

(Yorkston, Beukelman, & Traynor, 1984). First, the have been employed as a gauge of each of its compo-

speaker’s task is held constant because intelligibility scores nents—the impairment and the compensatory strategies

may differ depending on whether the speaker is producing employed by the speaker to improve speech production.

American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology • Vol. 5 • 1058-0360/96/0501-0055 © American Speech-Language-Hearing

Yorkston • Strand Association

• Kennedy 55

Downloaded from ajslp.asha.org on April 30, 2010

FIGURE 1. A model of factors that contribute to the adequacy repairs and explicit instructions. Intelligibility changes

of the acoustic signal and therefore to the speech intelligibility have been one of the measures used to document other

of dysarthric individuals.

treatment effects, including increased respiratory/

phonatory effort in Parkinson’s disease (Ramig, 1992;

Ramig, Bonitati, Lemke, & Horii, 1994), palatal lift fitting

(Aten, McDonald, Simpson, & Gutierrez, 1984; Yorkston,

Honsinger, Beukelman, & Taylor, 1989) and increased

physiologic support (Workinger & Netsell, 1992).

Figure 2 illustrates the additional factors that come into

play when considering the concept of comprehensibility.

Note that contextual or signal-independent information is

available to the listener as the acoustic signal is being

heard and processed. This information may take the form

of semantic or syntactic context, cues from the physical

environment, gestures or illustrators, and orthographic cues

such as the initial letters of words. The addition of contex-

tual information provides the listener with additional cues

to supplement the information conveyed by the acoustic

signal. Therefore, the concept of comprehensibility

provides an estimate of the adequacy of performance in

natural communication settings. As rehabilitation special-

ists are being required to document treatment efficacy,

an increased emphasis has been placed on factors that

contribute to enhancement of the overall communicative

For example, it has been used as an overall indicator of effectiveness.

severity of dysarthria or functional limitation imposed by The purpose of this paper is to (a) define comprehensi-

the speech impairment (Yorkston, Beukelman, & Bell, bility within the World Health Organization model of

1988). In a recent survey of 10 years of dysarthria research, chronic disease, (b) review the growing literature related to

speech intelligibility was used as an index of severity in comprehensibility of dysarthric speech, and (c) discuss

69% of those manuscripts that reported severity of clinical approaches to improving comprehensibility,

dysarthria as a subject descriptor (Strand & Yorkston, including issues of candidacy, intervention planning, and

1994). Speech intelligibility has also been used as a treatment approaches.

measure of treatment effects. Yorkston, Hammen,

Beukelman, and Traynor (1990) reported changes in

speech intelligibility resulting from reduction in the

Comprehensibility Within the Model

speaking rates of individuals with ataxic and hypokinetic of Chronic Disease

dysarthria. Kennedy, Strand, and Yorkston (1994) used Because dysarthria is a chronic disorder, the World

intelligibility measures as an indicator of changes made by Health Organization (WHO) model of chronic disease has

dysarthric speakers in response to requests for verbal been used as a framework for describing approaches to

assessment and treatment (Yorkston et al., 1988). Recently,

a revised framework was suggested to provide a more

FIGURE 2. A model of factors that contribute to comprehensi- functional perspective (Institute of Medicine, 1991). This

bility of dysarthric individuals.

model contains five parameters: (a) pathophysiology

(changes in basic cell or functional physiology); (b)

impairment (loss or change in physiologic function); (c)

functional limitation (restriction or lack of ability to

perform an action or function because of the impairment);

(d) disability (limitations in performance of specific

functions within a natural context); and (e) societal

limitation (changes in performance that limit fulfillment of

social roles or deny access to services).

To illustrate the use of this model for dysarthria, Table 1

contains examples of the levels of deficits, assessment

targets, and approaches to intervention for each of the

parameters of the model. The examples used are taken

from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a progressive

neurologic disease frequently resulting in dysarthria. The

pathophysiologic deficit is degeneration of upper and lower

motor neurons. Assessment targets to determine whether

there is motor neuron degeneration consist of EMG and

56 American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology • Vol. 5 • No. 1 February 1996

Downloaded from ajslp.asha.org on April 30, 2010

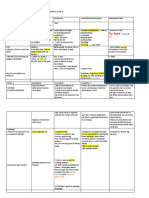

TABLE 1. A conceptual framework for assessment and intervention in ALS dysarthria. (Adapted from work initially developed by

the Institute of Medicine and published in Disability in America, 1991).

Pathophysiology Impairment Functional Limitation Disability Societal Limitation

Definition Interruption or inter- Loss and/or abnorm- Restriction or lack of Inability or limitation in Restriction, attributable to

ference of normal ality of mental, emo- ability to perform an performing socially social policy or barriers

physiological and tional, physiological, action or activity in defined activities and (structural or attitudinal),

developmental pro- or anatomical struc- the manner or range roles within a social which limits fulfillment of

cesses or structures ture or function, inclu- considered normal and physical environ- roles or denies access to

ding secondary that results from ment as a result of services or opportunities

losses and pain impairment internal or external

factors and their

interplay

Level of deficit Cells and tissues Components of the Speech performance Speech performance Performance of roles by

speech production with full range, speed, in a physical and speakers in social context

process, including strength, & coordi- social context

respiration, phonation, nation

velopharyngeal func-

tion, and oral articula-

tory structures

Examples of Degeneration of upper Changes in respira- Speech intelligibility Comprehensibility Premature retirement

assessment & lower motor tory support

targets neurons through EMG

& clinical observation

Examples of No physiologic inter- Energy conservation Proper phrasing of • Reduction in noise Scaffolding to support work-

approaches vention is currently techniques to com- utterances to high- in the environment related activities

to intervention available for ALS pensate for poor light stress patterning • Partner signals

respiratory support when messages are

not understood so

that repair strategies

can be initiated

clinical observation of spasticity, fasciculations, and the environment during communicative exchanges.

atrophy. Currently, there is not intervention at this physi- Another example of intervention at the level of disability

ologic level. The impairment associated with dysarthria in might be teaching the communication partner to signal

ALS results from deficits in respiration, phonation, when messages have not been understood so that strategies

velopharyngeal function, and/or oral articulation. Ap- for repair can be initiated. The final level in this framework

proaches to the assessment and treatment of the impair- is societal limitation. This implies the restriction of a

ment have been described elsewhere (Rosenbek & speaker’s ability to perform societal roles because of the

LaPointe, 1985; Yorkston et al., 1988). Using the example dysarthria. With some recent exceptions (King, Ramig,

of dysarthria associated with ALS, the assessment target Stein, & Dereshiwsky, 1994), there are no structured

for understanding the contribution of reduced respiratory approaches for measurement of such limitations in

support to the speech impairment may include measure- dysarthria. Until better measures are available, we must

ment of vital capacity, sustained phonation time, and rely on activities such as interviews regarding recreation,

phrase length. Intervention at the level of the impairment home maintenance, or vocational roles. Intervention at the

might include training the use of energy conservation level of societal limitation may take the form of develop-

techniques to compensate for poor respiratory support. For ment of scaffolding to support work-related activities or

the parameter of functional limitation, the level of deficit educating employers about the removal of barriers to

refers to how well the dysarthric speaker can perform communication.

movements to produce the intended acoustic output. At this

point, measures such as speech intelligibility are targets of

assessment. An example of intervention at this level might

Studies of Comprehensibility

be encouraging the speaker to use proper phrasing in order in Dysarthria

to highlight stress patterning, thus improving speech There are many reports in the field of dysarthria that

intelligibility. focus on speech intelligibility. Studies of children (Kent,

If functional limitation is defined as performance of an Miolo, & Bloedel, 1994) and of adults (Yorkston, Dowden,

activity, the disability is the performance of that activity in & Beukelman, 1992) have been reviewed elsewhere. The

a natural setting or context. We are recommending that the focus of the following section will be on those studies that

term comprehensibility be used to indicate the adequacy of measure speech intelligibility in the context of some type

speech performance in a social context. An example of of signal-independent information. The term that we are

intervention at this level might be the reduction of noise in applying to this topic is comprehensibility.

Yorkston • Strand • Kennedy 57

Downloaded from ajslp.asha.org on April 30, 2010

Semantic Context FIGURE 3. Single word intelligibility scores for the No Context

and Context condition when subjects were grouped according

The contribution of semantic context to intelligibility to dysarthria severity. (Reprinted with permission, Hammen et

has perhaps received the most substantial research atten- al., 1991.)

tion. Hammen and colleagues (Hammen, Yorkston, &

Dowden, 1991) studied the impact of semantic categories

on judges’ ability to understand single words produced by

21 individuals with moderate to profound dysarthria. The

semantic categories were developed by asking responders

to provide prototypical examples of words or phrases in 60

common semantic categories. Table 2 contains examples of

six semantic categories and the set of 12 words or phrases

most commonly provided for that category. Dysarthric

speakers produced a list of 50 words randomly selected

from semantic categories such as these. Three judges

orthographically transcribed the word lists, first without

semantic context and then with the context provided.

Results displayed in Figure 3 suggest that word intelligibil-

ity increased with semantic context for all severity groups:

speakers with profound, severe, and moderate dysarthria.

The largest difference was noted for the severe group,

where scores improved by 40.2%.

In extending the study of the effects of semantic context

on speech intelligibility, Dongilli (1994) examined single

words and target words embedded in sentences produced

severity from mild to profound. Results indicated that

by eight individuals with flaccid dysarthria ranging in

severely dysarthric speakers benefited the most from

TABLE 2. Examples of semantic contexts and words or

semantic cues, whereas mildly dysarthric speakers ben-

phrases provided most frequently. Lists are presented in efited the least. Overall, listeners’ knowledge of the

alphabetical order. (Adapted from Hammen et al., 1991.) semantic context improved speech intelligibility; however,

the effect was greater for single words than for words

Something embedded in sentences. The author suggests that perhaps

Men Wear Kind of Ice Cream Holidays the benefit of knowing the syntax of the sentence overshad-

owed any benefit that the semantic cue provided, particu-

Coat Banana Christmas

larly for mildly involved speakers. The implication of this

Hat Cherry Easter

finding is that listeners not only use semantic context but

Jacket Chocolate Father’s Day

also sentence structure to determine the content of the

Pants Coffee Halloween

message.

Shirt Mint Independence Day

Shoes Mocha Labor Day

Shorts Neopolitan Memorial Day Syntactic Context

Socks Peach Mother’s Day

Carter and colleagues (Carter, Yorkston, Strand, &

Sweater Pecan New year’s Day

Hammen, 1996) argue for the importance of syntactic as

Tie Raspberry Thanksgiving

well as semantic cues for improving the intelligibility of

Undershirt Strawberry Valentine’s Day

dysarthric speech. Sentence production samples were

Vest Vanilla Veterans’ Day

obtained from three speakers with moderate dysarthria

(sentence intelligibility scores 70–82%) and from three

Type of Bird Colors Household Appliances

speakers with severe dysarthria (sentence intelligibility

Bluejay Black Blender scores 30–40%). Judges listened and orthographically

Cardinal Blue Dishwasher transcribed the sentences under three conditions: no

Crow Brown Dryer context, semantic context, and syntactic context. For

Eagle Green Freezer example, for the sentence “The police said the collision

Hawk Grey Microwave was not my fault,” the semantic cue was “accident,” and

Heron Orange Mixer the syntactic cue was “ The _____ _____ the _____ was

Owl Pink Oven not my _____.” Results indicated that both semantic and

Parakeet Purple Refrigerator syntactic cues improved the sentence intelligibility of

Parrot Red Stove severely but not moderately involved dysarthric speakers.

Robin Tan Television One possible explanation for the lack of effect for the

Seagull White Toaster moderate group is that the sentences were fairly under-

Sparrow Yellow Washer standable (70–82% intelligibility) based on the acoustic

signal alone. The addition of semantic and syntactic cues

58 American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology • Vol. 5 • No. 1 February 1996

Downloaded from ajslp.asha.org on April 30, 2010

did not enhance the comprehensibility of the message improved. In the other experiment, judges viewed video-

further. For the severely impaired group, a number of tapes as they made their judgments. Results are displayed

possible mechanisms might be responsible for the im- in Figure 4 for low predictive and high predictive sen-

provement. Semantic context may increase the predictabil- tences. Note the marked differences in speech intelligibility

ity of stimuli and decrease the need to rely on the acoustic between the conditions. When the listener’s knowledge

signal. The mechanism for the benefits of syntactic was maximized through the speaker’s use of gestures and

context may be somewhat different. Syntactic context may high message predictiveness, there was a 70% gain in

help the listener identify the boundaries of linguistically intelligibility. These differences are especially impressive

meaningful units, thus improving speech intelligibility. In since the speech acoustic signal apparently had not

other words, syntactic context may assist the listener in improved.

parsing the distorted acoustic signal into the appropriate

units.

Orthographic Cues

The role of orthographic cues in enhancing the intelligi-

Gestures bility of severely dysarthric speakers was reported by

In addition to studying the influence of predictiveness Beukelman and Yorkston (1977). Two speakers with

and knowledge of the contextual situation, Garcia and acquired dysarthria, one as the result of a brain stem stroke

Cannito (1996) investigated benefits of naturally occurring and the other a traumatic brain injury, were recorded as

gestures called illustrators. Illustrators are defined by they read sentences, once as they did habitually (unaided

Ekman and Friesen (1969) as movements that are directly condition) and once as they pointed to the first letter of

tied to speech by serving to visually illustrate what is each word on an alphabet board (aided condition). Judges

spoken verbally. For example, for the sentence “Stop and orthographically transcribed the sentences produced in the

turn around where you are,” the illustrators were palm unaided and the aided conditions. In addition, judges

extended in a halting motion and then circular motion of transcribed the samples in a third condition (board con-

the index finger. The authors speculated that such illustra- cealed). In this condition, the speech samples recorded for

tors have the potential of enhancing intelligibility either by the aided condition were presented to the judges with the

supplying additional semantic information or by reorganiz- portion of the video monitor showing the spelling board

ing and modifying the speech production, as was suggested concealed. The third condition was added in an effort to

by Rosenbek (1984). Garcia and Cannito conducted two understand the influence of the rate reduction that occurred

experiments. In one, the extent to which speech production as speakers used the alphabet board to identify initial

was improved by having the speaker produce simple letters of words. Results are displayed in Figure 5. Note

gestures as he spoke was studied. In this experiment, all that a marked improvement in sentence intelligibility was

visual cues were removed, and judges listened to audio- noted when speakers pointed to the alphabet board and

tapes of habitual speech and speech produced with illus- judges were able to see the additional orthographic

trating gestures. No difference between the two production

conditions was noted. Thus, speech production had not FIGURE 5. Sentence intelligibility for speakers N and H under

three experimental conditions: Unaided (habitually produced),

FIGURE 4. Sentence intelligibility scores of a 62-year-old man Aided (pointing to the first letter of each word on an alphabet

with flaccid dysarthria. Low and high predictive sentences board) and Board Concealed (same as Aided except that the

were produced with and without gestures. (Adapted from judge could not see the alphabet board). (Adapted from

Garcia & Cannito, 1996.) Beukelman & Yorkston, 1977.)

Yorkston • Strand • Kennedy 59

Downloaded from ajslp.asha.org on April 30, 2010

information (aided condition). Because there was no comes from theoretical models, data-based research, and

difference between the unaided and board concealed clinical impressions.

condition for speaker N, the increase in intelligibility From a theoretical perspective, the model of mutuality

appears to be due to the additional information provided by proposed by Lindblom (1990) provides some insight into

the board rather than by improved production at slowed the relationship between severity of dysarthria and the

speaking rates. For speaker H, both rate reduction and importance of contextual information. Figure 6 illustrates

orthographic supplementation appear to contribute to the relationship between the information from the acoustic

improved intelligibility. In 1989, Crow and Enderby also signal, speech intelligibility, signal-independent informa-

reported consistent changes in word and sentence intelligi- tion, and contextual information. If the signal information

bility using alphabet supplementation. is rich and speech intelligibility is high, then comprehensi-

bility is high even in the face of restricted contextual

information. However, as the richness of the information

The Physical Environment from the acoustic signal is degraded, as in severe

For many years, clinicians have appreciated the impor- dysarthria, the signal-independent information becomes

tance of the environments in which speakers with more critical for maintenance of comprehensibility.

dysarthria are attempting to communicate. Berry and Results from the research literature cited above also

Sanders (1983) reviewed principles of “environmental suggest that severity of the dysarthria plays an important

education” in which factors such as predictability of the role in predicting the benefits of contextual information.

situation, noise, lighting, distance, and posture are exam- Relying exclusively on this literature, one would predict

ined in order to develop an appropriate intervention plan. greatest benefits for individuals with moderate to severe

Recent surveys of individuals with dysarthria have dysarthria. In other words, the speech of individuals with

confirmed the importance of environmental factors. When mild dysarthria may not be sufficiently distorted to cause

asked for their perspective on what factors make communi- listeners to have difficulty accurately understanding the

cation situations difficult (Yorkston, Bombardier, & message. The literature would suggest that speech intelligi-

Hammen, 1994), dysarthric individuals indicate greatest bility of mildly dysarthric speakers does not improve with

difficulty on items characterized by “environmental contextual information, perhaps because their speech is

adversity.” These items include situations such as “Chat- already nearly completely intelligible. On the other end of

ting with someone while riding in a car,” and “Having a the severity continuum, profoundly dysarthric speakers

conversation at a social gathering while others are nearby tend not to benefit greatly from contextual information,

and the room is dimly light.” Many of the environmental perhaps because their speech is so distorted that listeners

conditions described by Berry and Sanders are represented become confused by receiving additional information to

in these items. process in light of the severely degraded acoustic signal.

Although the literature regarding the comprehensibility Caution is warranted in interpreting this literature. The

of dysarthric speech is not extensive, there is growing literature does not address the important issue of listener

evidence to suggest that many signal-independent factors burden. Contextual information may reduce the burden of

have potential for influencing the understandability of communication placed on the listener and thus make

speakers with dysarthria. Information may take the form of overall communication exchanges easier. Likewise, for

semantic, syntactic, orthographic, or gestural context. How

these factors can be incorporated into a treatment program FIGURE 6. The contribution of information from the acoustic

will be discussed in the following section. signal and the signal-independent information to the compre-

hensibility of the dysarthric speaker. (Adapted from Lindblom,

1990.)

Clinical Implications

Perhaps the most fundamental clinical implication of the

notion of comprehensibility is the fact that it provides the

functional perspective so important in today’s health care

environment. It is likely that failure to assess and treat at

the level of disability such as comprehensibility will affect

reimbursement for clinical services. Further, bringing

about functional changes is at the heart of our clinical

practice. In this section, issues of candidacy and specific

strategies and their implementation into an overall treat-

ment plan will be discussed.

Candidacy

What are the characteristics of speakers with dysarthria

who would likely benefit from an intervention focusing on

improved comprehensibility? Support for the importance

of severity of dysarthria as a factor in candidacy decisions

60 American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology • Vol. 5 • No. 1 February 1996

Downloaded from ajslp.asha.org on April 30, 2010

individuals with profound dysarthria, the small changes in different terms have been applied when discussing the

speech intelligibility brought about by context may prove communication recipient. When discussing speech intelli-

functionally important. gibility, the term listener has usually been employed,

Other factors, such as level of cognitive functioning, implying that the individual is attending to the acoustic

may also make certain individuals with dysarthria better signal in an effort to understand it. When discussing

candidates than others for intervention focusing on comprehensibility, on the other hand, the term communica-

maximizing comprehensibility. Providing communication tion partner will be employed. The important role of the

partners with the appropriate semantic, syntactic, gestural, communication partner in establishment of psychosocial

or other contextual information is a complex activity. It has well-being has been highlighted in treatment approaches

been our clinical experience that these skills develop for individuals with aphasia (Lyon, 1989, 1991). The term

spontaneously in only the most cognitively-intact individu- communication partner implies an active alliance between

als. Another factor to consider is the speaker’s level of the communicators with shared communicative responsi-

experience with the dysarthria. Individuals who acquire bility. The following section will highlight the role of

dysarthria as an adult must learn to manage communication communication partners in intervention. In our experience,

situations differently than prior to the disorder. Skills for treatment aimed at improving comprehensibility is best

managing conversation when one must rely on a highly accomplished within communication dyads. Consistently

distorted speech signal are different from the skills needed bringing the major communication partners(s) into the

in normal interaction. Again, it is our clinical experience treatment process is essential to achieving improved ability

that the most successful users of signal-independent infor- to convey communicative intent in natural environments.

mation are those with the most practice. Vogel and Miller Several factors are important to emphasize with

(1991) also suggest that speakers’ ability to use this type of communication partners of dysarthric speakers: (a) their

information may be compromised as a result of aging, role in improving comprehensibility, (b) procedures for

dementia, aphasia, and right hemisphere dysfunction. manipulating the environment, (c) techniques involved in

In summary, we have used a theoretical model, research maximizing hearing acuity, and (d) strategies to be adapted

findings, and clinical impressions to develop a profile for dealing with communication breakdown. Initially, it is

characterizing the ideal candidate for use of signal- important to make the point that it is not the dysarthric

independent information to improve comprehensibility. client who comes for treatment to improve comprehensibil-

This candidate would have long-standing, moderate to ity, but the communicating “pair.” In other words, treat-

severe dysarthria and would have the cognitive skills ment is focused on a process that involves both partners, as

necessary to develop strategies to compensate for a highly speakers and listeners. The nondysarthric partner has an

distorted speech signal. important role in maximizing communication efficiency.

Examples of areas of responsibility include: making sure to

be in the same room when initiating conversation; making

Strategies to Enhance Comprehensibility of sure to watch the face of the dysarthric speaker as he or she

Dysarthric Speech talks; and not initiating conversation while the dysarthric

Before we present some specific techniques for enhanc- speaker is eating or drinking. Manipulation of the environ-

ing comprehensibility, it is useful to discuss a general ment, although seemingly simple, can greatly enhance

approach to treatment planning in this area. Recall that the comprehensibility. Turning down the radio or television,

goal of this type of intervention is to improve performance making sure the lighting is adequate, and avoiding noisy

in natural communication environments. In other words, environments (e.g., a room full of people talking) during

we are seeking to enhance performance in many situations, conversation are examples of ways to make the environ-

including home, work, or public accommodations, talking ment facilitate communication. It is also important for the

with one person or with many, talking to family, friends, or communication partner of a dysarthric speaker to make

strangers, talking in noisy situations or quiet ones, in face- sure their hearing acuity is maximized. Even mild hearing

to-face situations or in situations where communication loss can impede the listener’s ability to make maximum

partners cannot see one another. Because the number of use of the acoustic signal.

potential communication situations is large, clinicians Strategies for dealing with communication breakdown

cannot hope to develop precise plans for each situation. should be determined and agreed on by both the dysarthric

Rather, treatment planning should be considered a partner- speaker and the communication partner. Examples of such

ship between clinicians, clients, and their families. The strategies include: (a) having the listener signal in some

clinician’s role in this partnership is to provide the client predetermined way that the message was not understood;

with a framework for evaluating each communication (b) agreeing to repeat the message one time (using learned

setting and to develop strategies that are appropriate for strategies that maximize the acoustic signal); (c) if the

that situation (Francis Tucker, personal communication, message is still not understood, adopt an agreed on back up

1994). When given a suitable background, clients and their method, such as rephrasing the message using different

families will often find solutions that extend well beyond syntax, or perhaps substituting a synonym, or spelling

those that the clinician would have developed indepen- problematic words. Appendix A contains a checklist for

dently. Further, they will readily adapt principles they learn communication partners of dysarthric speakers. These

to new or different situations. items can be used in treatment and given to the client to

The Communication Partner. Readers will note that take home. In our experience, strategies for improving

Yorkston • Strand • Kennedy 61

Downloaded from ajslp.asha.org on April 30, 2010

comprehensibility are often based on common sense. It is nation of this checklist will reveal that not all of the

not difficult for dysarthric speakers and their communica- suggestions are appropriate for every individual with

tion partners to understand the techniques and how and dysarthria. Rather, the clinical discussion may focus on

when to use them. It does require changing old patterns of which of these may be useful and which would not. We

habitual communication styles, which can be very difficult have provided this information in a checklist format

to change. For example, one couple did most of their because clients and their families tell us that having written

communicating during the evening meal. Although it was information to review at their leisure is helpful to them.

obvious that this was becoming more and more difficult

due to the increasing dysarthria of a degenerative disease,

both partners found it uncomfortable to set aside another

The Role of Comprehensibility in the Overall

time, in a quiet room, to communicate the events of their

Treatment Plan

day. As a result, patients often report that although they Many approaches to treatment are available to individu-

know what to do, they haven’t really used the strategies at als with dysarthria. Some of these approaches are illus-

home. Treatment, therefore, should also include discussion trated in Figure 7, which depicts the dysarthria on one side

regarding ways to implement these changes in a manner of a scale as a heavy weight tipping the balance against the

that will work for each person’s lifestyle. speaker. The weight is heavier with severe dysarthria.

The Speaker With Dysarthria. Because adults with None of the clinical interventions currently available are

acquired dysarthria already have a tremendous fund of sufficient, by themselves, to tip the balance in favor of the

knowledge related to language and the communication speaker. Therefore, treatment planning in dysarthria can be

process, they can use this knowledge to their advantage. conceptualized as a process of finding and placing a

An excellent framework for developing a plan to improve number of small weights on the other side of the scale to

the comprehensibility of dysarthric speech is presented by counterbalance the weight of the disorder.

Vogel and Miller (1991). They describe a knowledge- Some of the most effective of these treatment tech-

driven or “top-down” approach to treatment. The term top- niques have as their goal improved speech intelligibility or

down is used to refer to “the cognitive process of using increasing the adequacy of the acoustic signal. Speech

available information to construct a gestalt, or whole” (p. intelligibility may be improved by reducing the level of

89). Using their model, a “bottom-up” approach would impairment, for example, strengthening the weak oral

involve the listener’s attempt to understand the acoustic muscles of an individual with a brainstem stroke. Intelligi-

signal, whereas a “top-down” approach would involve bility may also be improved by developing compensatory

using whatever contextual information is available. strategies such as increasing vocal loudness by increasing

Appendix B contains a checklist of techniques that we the level of effort of a speaker with Parkinson’s disease.

use as a starting point for our discussions with clients. Most of the individuals with dysarthria questioned about

Many of these techniques follow from knowledge of what compensatory strategies they found most useful

semantics, syntax, phonology, and pragmatics of language suggested that “improved production” was more effective

processing described by Vogel and Miller (1991). Exami- for them than strategies such as those that relate to environ-

FIGURE 7. A schematic representation of approaches to intervention for individuals with severe dysarthria.

62 American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology • Vol. 5 • No. 1 February 1996

Downloaded from ajslp.asha.org on April 30, 2010

ment modification, partner instruction, or other factors FIGURE 8. (top) Word intelligibility as judged by familiar and

(Yorkston et al., 1994). unfamiliar listeners with and without semantic context for ND.

(bottom) Word intelligibility for CM with and without semantic

Other interventions for dysarthria, such as those context. CM produced the words either with a palatal lift or

discussed in the previous section, have as their goal without it (Adapted from Yorkston et al., 1992).

improved comprehensibility of communication. These

strategies include reduction of environmental adversity,

providing semantic or syntactic cues, or using gestures to

illustrate utterances. When used singly, each of the

strategies depicted in Figure 7 may have only a small

effect; however, when used in combination, they may bring

about important changes. Although this is often the case,

note that effects of multiple treatment approaches may not

always be more powerful than single approaches. For

example, those dysarthric speakers who have concomitant

cognitive impairment may benefit from single strategies.

Use of multiple approaches can be illustrated by

considering two cases (Yorkston et al., 1992). The first

case, ND, was a 57-year-old women with cerebral palsy

and severe dysarthria who used an augmentative communi-

cation device while communicating with acquaintances but

relied on natural speech most of the time with her family.

Figure 8 (top) illustrates word intelligibility scores with

and without semantic context for unfamiliar and familiar

listeners. Note that intelligibility scores were near zero for

both listening groups without context. Although the

addition of context improved intelligibility scores for both

groups of listeners, familiar listeners benefited more than

did unfamiliar ones. In another case, CM, a woman many

years postonset of traumatic brain injury, was fitted with a

palatal lift to compensate for poor velopharyngeal function.

Word intelligibility scores are illustrated in Figure 8 (bottom)

with and without semantic context. Note that neither inter-

vention applied singly had a marked effect. The difference

between the No lift and Lift condition (without context) was

only 3%, whereas the difference between the Without

Context and With Context condition was 15%. However,

combining the two conditions, Lift and Context, results in

55% improvement over the habitual condition.

In summary, attention to improving comprehensibility

has a role in intervention planning for many dysarthric

speakers. It becomes critically important for some catego-

ries of speakers with dysarthria. The first category includes

speakers whose dysarthria is so severe that all possible

interventions to counterbalance the heavy weight of the compehensibility are not yet available. However, instru-

impairment must be brought into play. The second and ments such as the Communicative Effectiveness Index

perhaps related category includes speakers for whom (Lomas et al., 1989) and the ASHA Functional Assessment

improving the adequacy of the speech signal is not a of Communications Skills for Adults (FACS; Thompson,

realistic goal. As an example, individuals in this category Frattali, & Holland, 1995) could be implemented as part of

might be speakers with moderate to severe dysarthria a battery of assessment tools. It is clear, however, that

associated with ALS. For these individuals, reducing their more work needs to be done to refine measurement

impairment is not an intervention goal because of the techniques for assessing overall comprehensibility as well

relentlessly progressive nature of their disorder. Because of as the effectiveness of treatment of comprehensibility.

their intact cognition and gradual onset of the dysarthria, Although speech intelligibility is one measure that contrib-

these individuals may also have already spontaneously utes information to the overall comprehensibility of a

developed whatever compensatory strategies are available communication message, it should not be the only means

to them for improving speech production. Intervention for of determining the success of the interaction. Analysis of

them may involve planning approaches to improve the comprehensibility should focus on the success of the

comprehensibility of communication. communication exchange and include such indicators as

A number of future research and clinical directions are the behaviors of the communication partner in response to

apparent. For example, standardized measures of the message. Measures of the perceived burden of the

Yorkston • Strand • Kennedy 63

Downloaded from ajslp.asha.org on April 30, 2010

communication task for both the speaker with dysarthria Selected acoustic changes in the verbal repairs of dysarthric

and the communication partner are also needed. Does this speakers. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology,

burden change as the severity of the dysarthria changes? 2(4), 263–279.

What is the relationship between this burden and overall Kent, R. D., Miolo, G., & Bloedel, S. (1994). The intelligibility

of children’s speech: A review of evaluation procedures.

quality of the communication, for the speaker with

American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 3, 81–95.

dysarthria and the communication partner? Answers to King, J. B., Ramig, L. O., Stein, H., & Dereshiwsky, M.

these and other questions will assist in the development of (1994). Young Parkinson’s disease: The impact of speech

speech intervention with goals to improve communication disability on employment. A presentation at the American

effectiveness and ultimately quality of life. Speech-Language-Hearing Association Annual Convention,

New Orleans.

Lindblom, B. (1990). On the communication process: Speaker-

Acknowledgment listener interaction and the development of speech. Augmenta-

Preparation of this work was supported in part by NIDCD tive and Alternative Communication, 6(4), 220–230.

grant 1K08 DC00043-01A1. Lomas, J., Pickard, L., Bester, S., Elbard, H., Finlayson, A., &

Zoghaib, C. (1989). The communicative effectiveness index:

Development and psychometric evaluation of functional

References communication measures for adults. Journal of Speech and

Aten, J., McDonald, A., Simpson, M., & Gutierrez, R. (1984). Hearing Disorders, 54, 113–124.

Efficacy of modified palatal lifts for improved resonance. In Lyon, J. G. (1989). Communicative partners: Their value in

M. McNeil, J. Rosenbek, & A. Aronson (Eds.), The reestablishing communication with aphasic adults. In T.

dysarthria: Physiology, acoustics, perception, management Prescott (Ed.), Clinical aphasiology (Vol. 18, pp. 11–18).

(pp. 231–242). Boston: College-Hill. Boston: College-Hill.

Barefoot, S. M., Bochner, J. H., Johnson, B. A., & vom Eigen, Lyon, J. G. (1991). Communication use and participation in life

B. A. (1993). Rating deaf speakers’ comprehensibility: An for adults with aphasia in natural settings: The scope of the

exploratory investigation. American Journal of Speech- problem. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology,

Language Pathology, 2(3), 31–35. 1(3), 7–14.

Berry, W., & Sanders, S. (1983). Environmental education: The Miller, G. A., & Selfridge, J. A. (1950). Verbal context and the

universal management approach for adults with dysarthria. In recall of meaningful material. American Journal of Psychol-

W. Berry (Ed.), Clinical dysarthria. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. ogy, 63, 176–185.

Beukelman, D. R., & Yorkston, K. M. (1977). A communica- Ramig, L. (1992). The role of phonation in speech intelligibility:

tion system for the severely dysarthric speaker with an intact A review and preliminary data from patients with Parkinson’s

language system. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, disease. In R. D. Kent (Ed.), Intelligibility in speech disorders

42, 265–270. (pp. 119–156). Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Carter, C. R., Yorkston, K. M., Strand, E. A., & Hammen, V. Ramig, L. O., Bonitati, C. M., Lemke, J. H., & Horii, Y.

(1996). The effects of semantic and syntactic content on the (1994). Voice treatment for patients with Parkinson disease:

actual and estimated sentence intelligibility of dysarthric Development of an approach and preliminary efficacy data.

speakers. In D. Robin, K. M. Yorkston, & D. R. Beukelman Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology, 2(3), 191–

(Eds.), Disorders of motor speech. Baltimore: Paul H. 210.

Brookes. Rosenbek, J. (1984). Treating the dysarthric talker. Seminars in

Crow, E., & Enderby, P. (1989). The effects of an alphabet Speech and Language, 5, 359–384.

chart on the speaking rate and intelligibility of speakers with Rosenbek, J. C., & LaPointe, L. L. (1985). The dysarthrias:

dysarthria. In K. M. Yorkston & D. R. Beukelman (Eds.), Description, diagnosis, and treatment. In D. Johns (Ed.),

Recent advances in clinical dysarthria. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. Clinical management of neurogenic communication disorders.

Dongilli, P. (1994). Semantic context and speech intelligibility. Boston: Little Brown.

In J. Till, K. Yorkston, & D. Beukelman (Eds.), Motor speech Strand, E. A., & Yorkston, K. M. (1994). Description and

disorders: Advances in assessment and treatment. Baltimore, classification of individuals with dysarthria: A 10-year review.

MD: Paul H. Brookes. In J. A. Till, K. M. Yorkston, & D. R. Beukelman (Eds.),

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1969). The repertoire of nonver- Motor speech disorders: Advances in assessment and

bal behavior: Categories, origins, usage, and coding. treatment (pp. 37–56). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Semiotica, 1, 49–98. Thompson, C. K., Frattali, C., & Holland, A. (1995). The

Garcia, J. M., & Cannito, M. P. (1996). Top down influences American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Functional

on the intelligibility of a dysarthric speaker: Addition of Assessment of Communication Skills (ASHA FACS): Test

natural gestures and situational context. In D. Robin, K. description and pilot data. A paper presented at the Clinical

Yorkston, & D. Beukelman (Eds.), Disorders of motor speech. Aphasiology Conference, Sunriver, OR.

Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. Vogel, D., & Miller, L. (1991). A top-down approach to

Hammen, V. L., Yorkston, K. M., & Dowden, P. A. (1991). treatment of dysathric speech. In D. Vogel & M. Cannito

Index of contextual intelligibility I: Impact of semantic (Ed.), Treating disordered speech motor control (pp. 87–109).

context in dysarthria. In C. Moore, K. M. Yorkston, & D. R. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Beukelman (Eds.), Dysarthria and apraxia of speech: Workinger, M. S., & Netsell, R. (1992). Restoration of

Perspectives on intervention. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. intelligible speech 13 years post-head injury. Brain Injury,

Brookes. 6(2), 183–187.

Institute of Medicine. (1991). Disability in America: Toward a Yorkston, K. M., Beukelman, D. R., & Bell, K. R. (1988).

national agenda for prevention. . Washington, DC: National Clinical management of dysarthric speakers. Austin, TX:

Academy Press. Pro-Ed.

Kennedy, M. R. T., Strand, E. A., & Yorkston, K. M. (1994). Yorkston, K. M., Beukelman, D. R., & Traynor, C. (1984).

64 American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology • Vol. 5 • No. 1 February 1996

Downloaded from ajslp.asha.org on April 30, 2010

Computerized assessment of intelligibility of dysarthric Taylor, T. (1989). The effects of palatal lift fitting on the

speech. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. perceived articulatory adequacy of dysarthric speakers. In K.

Yorkston, K. M., Bombardier, C., & Hammen, V. L. (1994). M. Yorkston & D. R. Beukelman (Eds.), Recent advances in

Dysarthria from the viewpoint of individuals with dysarthria. clinical dysarthria (pp. 85–98). Boston: College-Hill.

In J. A. Till, K. M. Yorkston, & D. R. Beukelman (Eds.), Yorkston, K. M., Miller, R. M., & Strand, E. A. (1995).

Motor speech disorders: Advances in assessment and Management of speech and swallowing disorders in degenera-

treatment (pp. 19–36). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. tive disease. Tucson, AZ: Communication Skill Builders.

Yorkston, K. M., Dowden, P. A., & Beukelman, D. R. (1992).

Intelligibility as a tool in the clinical management of Received April 21, 1995

dysarthric speakers. In R. D. Kent (Ed.), Intelligibility in Accepted October 10, 1995

speech disorders: Theory, measurement and management

(pp. 265–286). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Contact author: Kathryn Yorkston, PhD, Rehabilitation Medicine,

Yorkston, K. M., Hammen, V. L., Beukelman, D. R., & RJ-30, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195. E-mail:

Traynor, C. D. (1990). The effect of rate control on the yorkston@u.washington.edu

intelligibility and naturalness of dysarthric speech. Journal of

Speech and Hearing Disorders, 55(3), 550–561.

Yorkston, K. M., Honsinger, M. J., Beukelman, D. R., & Key Words: comprehensibility, intelligibility, dysarthria

Appendix A

Techniques for Improving Comprehensibility: For the Communication Partners of the Dysarthric Speaker

Communication is a partnership. The following techniques may ❏ Avoid communication over long distances. Make sure to

make the communication process easier. The items that are always be in the same room when you initiate conversation. It is

checked may be the most appropriate for you. difficult for many speakers with dysarthria to speak loudly

enough to be heard in another room.

❏ Make sure you know the general topic of the conversation.

Knowing the topic of conversation makes a big difference in ❏ Make sure your hearing is as good as possible. It is

understanding speech that is distorted. Encourage speakers important that you hear well. If you suspect you have even a

with dysarthria to introduce topics. mild hearing loss, have your hearing tested. Properly fitted

hearing aids may make the speech of individuals with dysarthria

❏ Watch for turn-taking signals. Some speakers with dysarthria more understandable.

for whom speech is slow have difficulty getting a turn in a

conversation. Watch carefully for your partner’s signals or ❏ Decide on and incorporate strategies for resolving

decide in advance on some turn-taking signals. communication breakdowns. There may be times when you

will not be able to understand some or all of a message. It is

❏ Give your undivided attention. Speech is usually so easy to important to develop a plan of action to take if this happens.

understand that listeners can do other things and still under- Some people find the following steps helpful in preventing

stand what is being said. Speech that is slow and distorted is frustration:

more difficult to understand and therefore, requires our

• Signal as soon as you don’t understand. (Most people find

undivided attention. that a nonverbal signal is best because it does not disrupt

the flow of conversation).

❏ Picking the time and place for communication. Most of us

can talk all day without getting tired. Most of us can do many • Let the speaker know the parts of the message that you did

things while we talk. We can walk and talk, chew gum and talk, understand. (In this way, the speaker will not have to repeat

or eat and talk. Talking may be a very difficult task for a speaker the entire message.)

with dysarthria. Avoid important conversations when the • Let the speaker repeat the misunderstood words one time.

speaker is tired. Mealtimes may no longer be the best time for

conversation. • If you still don’t understand, ask the dysarthric speaker to go

to a predetermined “back up” plan that involves perhaps

❏ Watch the speaker. All of us get a considerable amount of rephrasing, verbal spelling, or writing.

information by watching a speaker. When speech is slow or

distorted, it is even more important to look at the speaker’s

❏ Establish some rules of the game. Speakers with dysarthria

may have some very definite preferences about what they

face. would like you to do and what they wish you would not do.

Knowing these preferences may reduce frustration. For

❏ Piecing together the cues. Some people describe the task of example, does the speaker with dysarthria want you to guess or

understanding slow and distorted speech as a process of not? want you to finish sentences or not?

piecing together a series of cues. Some of the cues, of course,

come from speech. Other cues may come from the gestures

that the speaker may use or from the physical surroundings.

❏ Facilitating communication with others. Communicating with

people who are unfamiliar to them is difficult for many dysarthric

Take advantage of whatever cues are available to you. speakers. You may be of assistance as a translator in some

situations. Again, it is useful to have some predetermined

❏ Make the environment work for you. Maximize your ability to guidelines. Does the dysarthric speaker want you to translate

understand the speaker with dysarthria by making sure you misunderstood parts of the message? to provide long or

have enough light; that the light is on the speaker’s face; and elaborate responses to questions when you know what the

that all extraneous noise is eliminated or reduced. answers are? to order food in a restaurant?

Yorkston • Strand • Kennedy 65

Downloaded from ajslp.asha.org on April 30, 2010

Appendix B

Techniques for Improving Comprehensibility: For the Dysarthric Speaker

(Adapted from Vogel and Miller, 1991; and Yorkston, Strand, and difficulty expressing subtle changes in meaning with your

Miller, in press). intonation, you’ll need to express sarcasm or humor in other

ways.

The following techniques may be useful for individuals whose

natural speech may at times be difficult to understand. The items ❏ Rephrase your message. If listeners have not understood you

that are checked may be the most appropriate for you. These even after you’ve repeated the message, try communicating the

techniques enhance the understandability of your speech by thought using different words. But use a signal to let them

providing your communication partner some extra cues: know.

❏ Provide your communication partner context for what you ❏ Accompany speech with simple gestures when appropri-

are saying. Knowing the topic of conversation makes a big ate. At times, speech may be supplemented by simple

difference in understanding speech that is distorted. If your gestures. For example the palm extended in a halting motion,

speech is difficult to understand, provide the context by writing then a circular motion with index finger may accompany the

or spelling the topic of your message. message, “Stop and turn around where you are.”

❏ Don’t shift topics abruptly. If your speech is difficult to ❏ Take advantage of situational cues. Your surroundings may

understand, your partners may get lost if you change from one help you give a listener extra cues. For example, you might

topic to another without a transition. Let people know that you point to objects in the room in order to introduce a topic.

are changing topic and what the new topic is.

❏ Make the environment as “friendly” as possible. Some

❏ Turn-taking signals. Conversations tend to go very quickly. If communication environments are more difficult than others.

your speech is slow, you may need to use clear signals that you Avoid carrying out important conversations in noisy places or in

want a turn. These signals may take the form of an eye gaze, a places where your communication partner cannot watch you as

breathing pattern, a body movement, a gesture, or verbal you speak, for example, in dimly lit rooms or in situations where

interjection. Choose one or two that work for you and make your listener is a long distance from you.

sure listeners are aware of them.

❏ Avoid communication over long distances. Trying to speak

❏ Get your listener’s attention. It is impossible for any listener with someone who is across the room or in another room is

to understand unless he or she is paying attention. If your difficult. If you need to call attention to yourself, a buzzer,

speech is difficult to understand, it is even more important that beeper, or baby monitor may be useful.

listeners are paying attention. Before you begin a message,

alert your communication partner by saying his or her name. ❏ Alphabet board supplementation. If your speech is very

difficult to understand, you may want to point to the first letter of

❏ Use complete sentences. Grammatically complete sentences each word as you say it. This reduces your speaking rate,

are usually easier for listeners to understand. Avoid telegraphic allowing weakened muscles more time to formulate the precise

sentences or those in which the “little” grammatical words are movements of the speech sounds. It also provides the listener

deleted. with information about the word being spoken. If a word is not

understood even when the first letter of the word has been

❏ Use predictable types of sentences. Simple, grammatically identified, you can resolve the misunderstanding by spelling out

predictable sentences are generally easier to understand than the word in its entirety.

longer grammatically complicated sentences.

❏ Communicating emotional messages. Take care to commu-

❏ Use predictable wording. There are many ways to communi- nicate “emotionally loaded” messages when you are not tired

cate a single idea. If your speech is difficult to understand, and when there is plenty of time.

avoid unusual idioms or slang expressions. Be direct. For

example, “Close the window, please,” may be easier to ❏ Have a handy backup system. Have a highly understandable

understand than, “I wouldn’t mind if you would close the communication system handy in case of difficulty. This may be

window.” as simple as a pad of paper and pencil to write cue words.

Generally, we advise speakers with dysarthria not to let their

❏ Watch the tone of your voice. We communicate much listener get absolutely lost. Understanding little or nothing of a

information by changing the tone of voice. For example, the message can be very frustrating to a listener. If you see that

phrase “You really look terrific” may mean two completely someone is not understanding you, stop and make sure that he

different things depending on how you say it. If you have or she understands before you continue.

66 American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology • Vol. 5 • No. 1 February 1996

Downloaded from ajslp.asha.org on April 30, 2010

Comprehensibility of Dysarthric Speech: Implications for Assessment and Treatment

Planning

Kathryn M. Yorkston, Edythe A. Strand, and Mary R.T. Kennedy

Am J Speech Lang Pathol 1996;5;55-66

This article has been cited by 5 article(s) which you can access for free at:

http://ajslp.asha.org/cgi/content/abstract/5/1/55#otherarticles

This information is current as of April 30, 2010

This article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

http://ajslp.asha.org/cgi/content/abstract/5/1/55

Downloaded from ajslp.asha.org on April 30, 2010

View publication stats

Вам также может понравиться

- Palavras EssenciaisДокумент15 страницPalavras EssenciaisMaria Simone AlvesОценок пока нет

- Chapter 16Документ12 страницChapter 16Kholif Mawadda DpОценок пока нет

- 10 1 1 16 5972 PDFДокумент4 страницы10 1 1 16 5972 PDFMINAОценок пока нет

- Perceptual Learning of Multiple Talkers - Determinants, Characteristics, and LimitationsДокумент25 страницPerceptual Learning of Multiple Talkers - Determinants, Characteristics, and Limitationskai.uconnОценок пока нет

- Bodily Communication Dimensions of Expression andДокумент16 страницBodily Communication Dimensions of Expression andDavid GuОценок пока нет

- Appendix - 2Документ5 страницAppendix - 2Aditya KelkarОценок пока нет

- Listening by WolvinДокумент15 страницListening by WolvinShakul TewariОценок пока нет

- Effect of Complexity On Speech Sound Development Evidence From Meta-Analysis Review of Treatment-Based StudiesДокумент9 страницEffect of Complexity On Speech Sound Development Evidence From Meta-Analysis Review of Treatment-Based StudiesLetícia BitencourtОценок пока нет

- Key Conceptsin Teaching MacroskillsДокумент6 страницKey Conceptsin Teaching MacroskillsEricka InaldoОценок пока нет

- Consumer Psychology Review - 2020 - Schwarz - Metacognitive Experiences As Information Processing Fluency in ConsumerДокумент22 страницыConsumer Psychology Review - 2020 - Schwarz - Metacognitive Experiences As Information Processing Fluency in ConsumerXmai LeeОценок пока нет

- Elements of Phonological Interventions For Children With Speech Sound Disorders: The Development of A TaxonomyДокумент30 страницElements of Phonological Interventions For Children With Speech Sound Disorders: The Development of A TaxonomyYolanda GómezОценок пока нет

- Bakeretal2018 TaxonomyДокумент30 страницBakeretal2018 TaxonomydmgarciagaОценок пока нет

- Pupillometry CochlearДокумент22 страницыPupillometry CochlearFuninganaОценок пока нет

- Application of The ICF in Reduced Speech Intelligibility in DysarthriaДокумент11 страницApplication of The ICF in Reduced Speech Intelligibility in DysarthriaLuz Angiie M RОценок пока нет

- Adulta 1Документ14 страницAdulta 1Pao Jiménez AjiacoОценок пока нет

- The Semantics of Prosody - Nygaard Et Al - 2009Документ20 страницThe Semantics of Prosody - Nygaard Et Al - 2009Kyra WangОценок пока нет

- Key Concepts in Teaching Macroskills: February 2016Документ6 страницKey Concepts in Teaching Macroskills: February 2016力王勇Оценок пока нет

- Sounding Chinese and Listening Chinese Awareness and Knowledge in The LaboratoryДокумент37 страницSounding Chinese and Listening Chinese Awareness and Knowledge in The LaboratoryqyzzhutgОценок пока нет

- The Communicative Effectiveness Index: Development and Psychometric Evaluation of A Functional Communication Measure For Adult AphasiaДокумент13 страницThe Communicative Effectiveness Index: Development and Psychometric Evaluation of A Functional Communication Measure For Adult AphasiaFabiolaОценок пока нет

- 10 1016@j Jesp 2020 103978Документ8 страниц10 1016@j Jesp 2020 103978Tudor PopescuОценок пока нет

- The Scope of Clinical LinguisticsДокумент228 страницThe Scope of Clinical LinguisticsMeet UlixisОценок пока нет

- Psycholinguistic Models of Speech Production in Bilingualism and MultilingualismДокумент22 страницыPsycholinguistic Models of Speech Production in Bilingualism and Multilingualismkhadidja BOUTOUILОценок пока нет

- On The Design of Automatic Voice Condition Analysis Systems. Part IДокумент19 страницOn The Design of Automatic Voice Condition Analysis Systems. Part IGabriel Almeida AzevedoОценок пока нет

- Week 6Документ10 страницWeek 6jeo nalugonОценок пока нет

- Deconstructing Markedness - A Predictability-Based ApproachДокумент17 страницDeconstructing Markedness - A Predictability-Based ApproachSamah HassanОценок пока нет

- JCR A Sound Idea 2004Документ10 страницJCR A Sound Idea 2004javierОценок пока нет

- 21 Intrapersonal Communication and Imagined InteractionsДокумент13 страниц21 Intrapersonal Communication and Imagined InteractionsAlvin SimonОценок пока нет

- Basic Listening SkillsДокумент21 страницаBasic Listening SkillsAmjad PathanОценок пока нет

- Individual ProjectДокумент9 страницIndividual Projectpyeongjang468Оценок пока нет

- Jezikoslovlje 1 08 1 045 Dzanic 5BДокумент15 страницJezikoslovlje 1 08 1 045 Dzanic 5BBiljana MitrovicОценок пока нет

- Guia .What Is Listening and Why Is Important in The Acquisition of A Second Language.Документ4 страницыGuia .What Is Listening and Why Is Important in The Acquisition of A Second Language.mbetza83Оценок пока нет

- 13-The Opening Phase of Telemedicine ConsultationsДокумент9 страниц13-The Opening Phase of Telemedicine ConsultationsHuzi SidОценок пока нет

- A Pragmatic Perspective 2009Документ9 страницA Pragmatic Perspective 2009Maurício Fernandes Neves BenfattiОценок пока нет

- Treatment Dysarthria EfficacyДокумент12 страницTreatment Dysarthria EfficacySwathi GeethaОценок пока нет

- Critchfield 2017Документ10 страницCritchfield 2017Fernanda PellegriniОценок пока нет

- Written Report On Sentence ProcessingДокумент5 страницWritten Report On Sentence ProcessingAlfeo OriginalОценок пока нет

- Yellow Green Pastel Blue Yellow Playful Scrapbook Pet Conspiracy Theory Presentation PartyДокумент16 страницYellow Green Pastel Blue Yellow Playful Scrapbook Pet Conspiracy Theory Presentation PartyJonah Jatte Muñez100% (1)

- TESOL Quarterly - 2012 - FIELD - Intelligibility and The Listener The Role of Lexical StressДокумент25 страницTESOL Quarterly - 2012 - FIELD - Intelligibility and The Listener The Role of Lexical Stresslimili1996Оценок пока нет

- Application of Speech Processing For Pathological Voice Detection and AnalysisДокумент9 страницApplication of Speech Processing For Pathological Voice Detection and AnalysisInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyОценок пока нет

- Learning Materials EAPPДокумент11 страницLearning Materials EAPPLiezl Tuazon Lanoy PrimitivaОценок пока нет

- Part 2 - Topic 1 Teaching Strategies - ListeningДокумент3 страницыPart 2 - Topic 1 Teaching Strategies - ListeningApenton MimiОценок пока нет

- How Lexical Is The LexiconДокумент30 страницHow Lexical Is The Lexiconblitzwang7965Оценок пока нет

- Module 2 Communication: Definition and Elements: PresentationДокумент3 страницыModule 2 Communication: Definition and Elements: Presentationjudelyn ycotОценок пока нет

- English Information StructureДокумент33 страницыEnglish Information Structurethuto1010Оценок пока нет

- Ahelect LectureДокумент25 страницAhelect LecturepandabananaОценок пока нет

- An Overview of Listenig Skills TheoriesДокумент10 страницAn Overview of Listenig Skills TheoriesLeo AngieОценок пока нет

- Treatment Efficacy Summary: Dysarthria (Neurological Motor Speech Impairment)Документ1 страницаTreatment Efficacy Summary: Dysarthria (Neurological Motor Speech Impairment)Mara CadinoiuОценок пока нет

- Listening Comprehension Approach Design and ProcedureДокумент22 страницыListening Comprehension Approach Design and Proceduremychief100% (2)

- ListeningДокумент5 страницListeningGugah NugrahaОценок пока нет

- Multitask and Transfer Learning Approach For Joint Classification and Severity Estimation of DysphoniaДокумент12 страницMultitask and Transfer Learning Approach For Joint Classification and Severity Estimation of DysphoniaJeevanОценок пока нет

- Medidas de Participacioìn en ComunicacioìnДокумент22 страницыMedidas de Participacioìn en ComunicacioìnCarlos esteban Arriagada MirandaОценок пока нет

- Pharmacological Dosage Concepts: How Useful Are They For Educators and Speech-Language Pathologists?Документ5 страницPharmacological Dosage Concepts: How Useful Are They For Educators and Speech-Language Pathologists?Jose Alonso Aguilar ValeraОценок пока нет

- A Voice Inside My Head - The Psychological and Behavioral Consequences of Auditory TechnologiesДокумент15 страницA Voice Inside My Head - The Psychological and Behavioral Consequences of Auditory Technologiesxx2228Оценок пока нет

- Habla ClaraДокумент14 страницHabla ClaraCristóbal Landeros TorresОценок пока нет

- Article 18Документ31 страницаArticle 18vnhuynhОценок пока нет

- The Communicative Effectiveness Index CetiДокумент12 страницThe Communicative Effectiveness Index CetiGonzaloSebastianRojasFaúndezОценок пока нет

- Domain General Auditory Processing As A Conceptual and Measurement Framework For Second Language Speech Learning Aptitude A Test Retest Reliability StudyДокумент25 страницDomain General Auditory Processing As A Conceptual and Measurement Framework For Second Language Speech Learning Aptitude A Test Retest Reliability Studyjiying xuОценок пока нет

- Kent - Et - Al Acoustic in SSDДокумент22 страницыKent - Et - Al Acoustic in SSDBetül Özsoy TanrıkuluОценок пока нет

- Egbert Deppermann Introduction To Conversation Analysis 2012Документ8 страницEgbert Deppermann Introduction To Conversation Analysis 2012nihel rouiniОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan: Curriculum ConnectionsДокумент7 страницLesson Plan: Curriculum Connectionsapi-391714949Оценок пока нет

- An Analysis of Figurative Language in Ariana Grande'S Album "Thank U, Next"Документ11 страницAn Analysis of Figurative Language in Ariana Grande'S Album "Thank U, Next"Rosejen MangubatОценок пока нет

- ESP SULAM ReportsДокумент15 страницESP SULAM ReportsDaphne Khoo Xin EeОценок пока нет

- Pacing Guide 4 Sessions 11THДокумент39 страницPacing Guide 4 Sessions 11THDiego RodriguezОценок пока нет

- Learning and Activiating Vocabulary PDFДокумент5 страницLearning and Activiating Vocabulary PDFKamal Kaum Deep SinghОценок пока нет

- Connected Speech HWДокумент12 страницConnected Speech HWThuy AnhОценок пока нет

- Placement Test - Arabic - 1Документ9 страницPlacement Test - Arabic - 1Yomna HelmyОценок пока нет

- Academy Stars 5 Unit 1 It's An EmergencyДокумент7 страницAcademy Stars 5 Unit 1 It's An EmergencyGiselle SuarezОценок пока нет

- Difficult Debriefing Situations A Toolbox For Simulation EducatorsДокумент11 страницDifficult Debriefing Situations A Toolbox For Simulation Educatorsdanfer_99100% (1)

- Recognition Confidence Scoring For Use in Speech Understanding SystemsДокумент8 страницRecognition Confidence Scoring For Use in Speech Understanding Systemsaishwarya mekalaОценок пока нет

- Stemming and LemmatizationДокумент17 страницStemming and LemmatizationRoberto Valdez JassoОценок пока нет

- High German LanguagesДокумент3 страницыHigh German LanguagesAldoRodrigoChaniniОценок пока нет

- DLP Grade 7 The American Dust BowlДокумент6 страницDLP Grade 7 The American Dust BowlJolina VelascoОценок пока нет

- Multinational CompaniesДокумент27 страницMultinational CompaniesmixxОценок пока нет

- 0510 English As A Second Language: MARK SCHEME For The May/June 2011 Question Paper For The Guidance of TeachersДокумент10 страниц0510 English As A Second Language: MARK SCHEME For The May/June 2011 Question Paper For The Guidance of TeachersGabriel EcheverriaОценок пока нет

- English GCSE Leaflet or Guide WritingДокумент15 страницEnglish GCSE Leaflet or Guide WritingBen EaglesОценок пока нет

- Purposive Communication: Module 1: Communication Process, Principles and EthicsДокумент11 страницPurposive Communication: Module 1: Communication Process, Principles and EthicsJan Jerwin PobleteОценок пока нет

- Animal World Map ActivitiesДокумент4 страницыAnimal World Map Activitiescarolyn_vooОценок пока нет

- Aarsleff - Study and Use of Etymology in LeibnizДокумент9 страницAarsleff - Study and Use of Etymology in LeibnizSean Dowdy0% (1)

- WAA01 01 Pef 20220113Документ8 страницWAA01 01 Pef 20220113grengtaОценок пока нет

- Welcome To Our ICT Class, Students!Документ105 страницWelcome To Our ICT Class, Students!Fatima Norean G. NavaltaОценок пока нет

- The First Term English Test 1 AsДокумент2 страницыThe First Term English Test 1 AsdidiaОценок пока нет

- MSchlick The Turning Point in Philosophy 1931 PDFДокумент4 страницыMSchlick The Turning Point in Philosophy 1931 PDFMuhammad HammadОценок пока нет

- Historical EventДокумент5 страницHistorical EventNila RiantiОценок пока нет

- Distinguish Text-Types According To Purpose and Features: Enumeration and Time OrderДокумент2 страницыDistinguish Text-Types According To Purpose and Features: Enumeration and Time Ordersafasfsedru sgerynfgj93% (14)

- Plan de LectieДокумент3 страницыPlan de LectieConstantin CojoacaОценок пока нет

- Grade 7 Grammar ExcerciseДокумент3 страницыGrade 7 Grammar ExcercisenmtaifurОценок пока нет

- WHLP English 9-q1Документ5 страницWHLP English 9-q1Krizza Gales Demecillo100% (3)

- Every Child A Reader ProgramДокумент7 страницEvery Child A Reader ProgramShania Mae SaysonОценок пока нет

- Passive CausativeДокумент7 страницPassive CausativeKimberley Yapp KY100% (2)