Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Pasion V Locsin

Загружено:

Feeyell UyОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Pasion V Locsin

Загружено:

Feeyell UyАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Pasion v.

Locsin

Facts: Mariano G. Almeda, an agent of the Anti-Usuary Board, obtained from the

justice of the peace of Tarlac, a search warrant commanding any officer of the law

to search the person, house or store of the petitioner at Victoria, Tarlac, for “certain

books, lists, chits, receipts, documents and other papers relating to her activities as

usurer.” The search warrant was issued upon an affidavit given by the said Almeda.

On the same date, the said Mariano G. Almeda, accompanied by a captain of the

Philippine Constabulary, went to the office of the petitioner in Victoria, Tarlac and,

after showing the search warrant to the petitioner’s bookkeeper, Alfredo Salas, and,

without the presence of the petitioner who was ill and confined at the time,

proceeded with the execution thereof

The papers and documents seized were kept for a considerable length of time by

the Anti-Usury Board and thereafter were turned over by it to the respondent fiscal

who subsequently filed six separate criminal cases against the herein petitioner for

violation of the Anti-Usury Law.

The legality of the search warrant was challenged by counsel for the petitioner in

the six criminal cases and the devolution of the documents demanded. The

respondent Judge denied the petitioner’s motion for the reason that though the

search warrant was illegal, there was a waiver on the part of the petitioner.

HELD: Freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures is declared a popular

right and for a search warrant to be valid, (1) it must be issued upon probable cause;

(2) the probable cause must be determined by the judge himself and not by the

applicant or any other person; (3) in the determination of probable cause, the

judge must examine, under oath or affirmation, the complainant and such witnesses

as the latter may produce; and (4) the warrant issued must particularly describe the

place to be searched and persons or things to be seized.

In the instant case the existence of probable cause was determined not by the

judge himself but by the applicant. All that the judge did was to accept as true

the affidavit made by agent Almeda. He did not decide for himself. It does not

appear that he examined the applicant and his witnesses, if any. Even accepting the

description of the properties to be seized to be sufficient and on the assumption

that the receipt issued is sufficiently detailed within the meaning of the law, the

properties seized were not delivered to the court which issued the warrant, as

required by law.

Instead, they were turned over to the resp. provincial fiscal & used by him in building

up cases against petitioner. Considering that at the time the warrant was issued,

there was no case pending against the petitioner, the averment that the warrant

was issued primarily for exploration purposes is not without basis.

Вам также может понравиться

- Art. 3 Sec. 2 de Garcia vs. LocsinДокумент2 страницыArt. 3 Sec. 2 de Garcia vs. Locsindwight yuОценок пока нет

- Case Digest ConstiДокумент58 страницCase Digest ConstiAtlas LawOfficeОценок пока нет

- Pasion Sda. de Garcia v. LocsinДокумент7 страницPasion Sda. de Garcia v. LocsinFD BalitaОценок пока нет

- NARCISO ALVAREZ, Petitioner, The Court of First Instance of Tayabas and The Anti-Usury BoardДокумент38 страницNARCISO ALVAREZ, Petitioner, The Court of First Instance of Tayabas and The Anti-Usury BoardMelanie Christine Soriano PascuaОценок пока нет

- Narciso Alvarez vs. The Court of First Instance of Tayabas and The Anti-Usury Board (G.r. No. L-45358. January 29, 1937)Документ3 страницыNarciso Alvarez vs. The Court of First Instance of Tayabas and The Anti-Usury Board (G.r. No. L-45358. January 29, 1937)Ei BinОценок пока нет

- DigestДокумент2 страницыDigestSamantha CepedaОценок пока нет

- Case Digest ConstiДокумент62 страницыCase Digest ConstiEunice Serneo100% (1)

- Roan Vs Gonzales Full and Case DigestДокумент6 страницRoan Vs Gonzales Full and Case DigestKristanne Louise YuОценок пока нет

- Case No. 57 Narciso Alvarez, Petitioner, vs. The Court of First Instance of Tayabas and The Anti-Usury BOARD, Respondents. 64 PHIL 33 NotesДокумент3 страницыCase No. 57 Narciso Alvarez, Petitioner, vs. The Court of First Instance of Tayabas and The Anti-Usury BOARD, Respondents. 64 PHIL 33 NotesLaila Ismael SalisaОценок пока нет

- Alvarez V Cfi 64 Phil 33Документ3 страницыAlvarez V Cfi 64 Phil 33georgettesalinasОценок пока нет

- Searches and Seizures Cases1Документ205 страницSearches and Seizures Cases1Ye Seul DvngrcОценок пока нет

- Alvarez vs. CFIДокумент2 страницыAlvarez vs. CFIJeaa PantaleonОценок пока нет

- RoanvsGonzales Case DigestДокумент3 страницыRoanvsGonzales Case Digestjharik23Оценок пока нет

- 1st Reporter - SalamancaДокумент7 страниц1st Reporter - Salamancaconnie1joy1alarca1omОценок пока нет

- Search and Seizure Compiled Case DigestДокумент12 страницSearch and Seizure Compiled Case DigestShanelle Tamayo Napoles100% (1)

- Scope of The ProtectionДокумент23 страницыScope of The ProtectionjayОценок пока нет

- PP vs. RubioДокумент6 страницPP vs. RubioAldin Lucena AparecioОценок пока нет

- Alvarez vs. CFIДокумент4 страницыAlvarez vs. CFICristelle Elaine Collera0% (1)

- 1.moncada Vs PeopleДокумент4 страницы1.moncada Vs PeopleSitti Warna Ismael100% (1)

- Cased DigestsДокумент10 страницCased DigestsjayОценок пока нет

- Alvarez V CFIДокумент3 страницыAlvarez V CFIcbclemente082023Оценок пока нет

- Cases Last ConstiДокумент11 страницCases Last ConstiRonnel VivoОценок пока нет

- ALVAREZ To BurgosДокумент7 страницALVAREZ To BurgosCamille BritanicoОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 71410Документ4 страницыG.R. No. 71410runish venganzaОценок пока нет

- Cases For Exigent CircumstanceДокумент30 страницCases For Exigent CircumstanceAgustin TamangenОценок пока нет

- Alvarez v. CFIДокумент5 страницAlvarez v. CFIEnric AlcaideОценок пока нет

- Consti Law 2 Cases - Arrest, Searches and SeizuresДокумент20 страницConsti Law 2 Cases - Arrest, Searches and SeizuresAlyssa Mae BasalloОценок пока нет

- Evidence - Case DigestДокумент15 страницEvidence - Case DigestMarianne Hope VillasОценок пока нет

- Supreme Court: Miguel D. Larida For Petitioners. Montilla Law Office For Private RespondentДокумент3 страницыSupreme Court: Miguel D. Larida For Petitioners. Montilla Law Office For Private RespondentLuke Concepcion-ButayОценок пока нет

- Burgos vs. Chief of Staff G.R. No. L-64261 December 26, 1984 FactsДокумент4 страницыBurgos vs. Chief of Staff G.R. No. L-64261 December 26, 1984 FactsFrancis MoraledaОценок пока нет

- Miguel D. Larida For Petitioners. Montilla Law Office For Private RespondentДокумент6 страницMiguel D. Larida For Petitioners. Montilla Law Office For Private RespondentJusio Rae ReyesОценок пока нет

- Cased DigestsДокумент10 страницCased DigestsDjatTanОценок пока нет

- Miguel D. Larida For Petitioners. Montilla Law Office For Private RespondentДокумент21 страницаMiguel D. Larida For Petitioners. Montilla Law Office For Private RespondentememОценок пока нет

- Poli DoctrinesДокумент13 страницPoli DoctrinesNicole PTОценок пока нет

- Search and Seizure - Case DigestДокумент44 страницыSearch and Seizure - Case DigestDarby MarОценок пока нет

- Searches and SeizuresДокумент42 страницыSearches and SeizuresArnel Gaballo AwingОценок пока нет

- Alvarez v. Court (1937)Документ4 страницыAlvarez v. Court (1937)Ruth Angelica TeoxonОценок пока нет

- Miguel D. Larida For Petitioners. Montilla Law Office For Private RespondentДокумент7 страницMiguel D. Larida For Petitioners. Montilla Law Office For Private RespondentSimeon SuanОценок пока нет

- Roan VsДокумент2 страницыRoan VsGerberОценок пока нет

- Alvarez VS TayabasДокумент8 страницAlvarez VS TayabasKenneth OlivoОценок пока нет

- Succ 1st Set of CasesДокумент24 страницыSucc 1st Set of CasesJessy FrancisОценок пока нет

- 10 Formal Requirements For Holographic WillДокумент24 страницы10 Formal Requirements For Holographic WillNimpa Pichay67% (3)

- Consti 2 DigestsДокумент7 страницConsti 2 DigestsMikhail TrinidadОценок пока нет

- Page 2Документ84 страницыPage 2jayОценок пока нет

- Lopez vs. Commissioner of Customs 68 SCRA 320 (1975)Документ6 страницLopez vs. Commissioner of Customs 68 SCRA 320 (1975)Bj CaridoОценок пока нет

- CrimPro Search Seizure For Mi Love MwaДокумент76 страницCrimPro Search Seizure For Mi Love MwaAlexis Dominic San ValentinОценок пока нет

- Existence of Probable CauseДокумент4 страницыExistence of Probable CauseMaricon B. LabaoОценок пока нет

- Alvarez V CFIДокумент4 страницыAlvarez V CFIAgee Romero-ValdesОценок пока нет

- Crim Pro - Rule 126 CasesДокумент96 страницCrim Pro - Rule 126 CasesRenzОценок пока нет

- Evidence - Us Vs TorresДокумент8 страницEvidence - Us Vs TorresLudica OjaОценок пока нет

- Alvarez vs. CFI of TayabasДокумент1 страницаAlvarez vs. CFI of TayabasVince LeidoОценок пока нет

- Roan v. GonzalesДокумент11 страницRoan v. GonzalesIldefonso HernaezОценок пока нет

- Alvarez Vs CFIДокумент2 страницыAlvarez Vs CFICheza BiliranОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Law Ii Cases OshikoshДокумент40 страницConstitutional Law Ii Cases OshikoshFrancess Mae AlonzoОценок пока нет

- DigestsДокумент99 страницDigestsMatthew WilliamsОценок пока нет

- Moncado Vs PeopleДокумент4 страницыMoncado Vs PeoplecharmdelmoОценок пока нет

- Alvarez v. CFI DigestДокумент1 страницаAlvarez v. CFI DigestCfc-sfc Naic ChapterОценок пока нет

- Administrative Law in Tanzania. A Digest of CasesОт EverandAdministrative Law in Tanzania. A Digest of CasesРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (12)

- Report of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, and the Opinions of the Judges Thereof, in the Case of Dred Scott versus John F.A. Sandford December Term, 1856.От EverandReport of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, and the Opinions of the Judges Thereof, in the Case of Dred Scott versus John F.A. Sandford December Term, 1856.Оценок пока нет

- Install GuideДокумент1 страницаInstall GuideDeniz Ali KıranОценок пока нет

- Cayetano V Monsod G.R. No. 100113 September 3 1991Документ22 страницыCayetano V Monsod G.R. No. 100113 September 3 1991Feeyell UyОценок пока нет

- ACFrOgCvsHPeGPZF896 K HaqM1u0PQuhDOWPqSheIA8S SmE 4yXbZvQezx8hEa21t1OdYArgh0YYvSIeReReoULvec9Hc71mrbeAW JUz1 Deq2ykgE l0R5P8dFuRxGe BkFdxACcpvV5wPCtДокумент20 страницACFrOgCvsHPeGPZF896 K HaqM1u0PQuhDOWPqSheIA8S SmE 4yXbZvQezx8hEa21t1OdYArgh0YYvSIeReReoULvec9Hc71mrbeAW JUz1 Deq2ykgE l0R5P8dFuRxGe BkFdxACcpvV5wPCtFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- International Chamber of Commerce: Alternative Dispute Resolutions ICC Arbitration Rules ICC Mediation RulesДокумент17 страницInternational Chamber of Commerce: Alternative Dispute Resolutions ICC Arbitration Rules ICC Mediation RulesFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Timestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumbeДокумент26 страницTimestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumbeFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Hague Convention 0f 1907Документ22 страницыHague Convention 0f 1907Joie CruzОценок пока нет

- Timestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumberДокумент24 страницыTimestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumberFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Timestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumberДокумент24 страницыTimestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumberFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Oblicon64 76digestДокумент6 страницOblicon64 76digestJennifer Rabor-MacayanaОценок пока нет

- Criminal Law II Group Activity: Submitted byДокумент24 страницыCriminal Law II Group Activity: Submitted byFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Timestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumberДокумент30 страницTimestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumberFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Sample For Labor Law IДокумент1 страницаSample For Labor Law IFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Supreme Court: Custom SearchДокумент14 страницSupreme Court: Custom SearchFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Criminal Law II Group Activity: Submitted byДокумент24 страницыCriminal Law II Group Activity: Submitted byFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Name EFL 1 Tuesday 530 730 FINAL EXAMДокумент1 страницаName EFL 1 Tuesday 530 730 FINAL EXAMFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- CLEMENCIO Fiel Wilhelm-EFL-1-Tuesday-530-730-FINAL-EXAMДокумент2 страницыCLEMENCIO Fiel Wilhelm-EFL-1-Tuesday-530-730-FINAL-EXAMFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Nrel - Groupings For Research Paper, ReportДокумент1 страницаNrel - Groupings For Research Paper, ReportFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Labor Standards Law: Instruction: All Answers To The Questions Must Be Explained. IДокумент4 страницыLabor Standards Law: Instruction: All Answers To The Questions Must Be Explained. IFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- The Tragedy of The CommonsДокумент4 страницыThe Tragedy of The CommonsJake Floyd G. FabianОценок пока нет

- Timestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumberДокумент24 страницыTimestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumberFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Amado Saraum Vs PeopleДокумент1 страницаAmado Saraum Vs PeopleKling King100% (1)

- People Vs BenipayoДокумент2 страницыPeople Vs BenipayoTheodore0176Оценок пока нет

- Timestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumberДокумент24 страницыTimestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumberFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Timestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumbeДокумент26 страницTimestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumbeFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Oblicon Case Digests (Final Compilation)Документ182 страницыOblicon Case Digests (Final Compilation)marizfuster1775% (8)

- 46 People v. LaraДокумент2 страницы46 People v. LaraimXinY100% (1)

- Arithmetic Sequences and SeriesДокумент14 страницArithmetic Sequences and SeriesFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Uy Vs Javellana 680 SCRA 13Документ1 страницаUy Vs Javellana 680 SCRA 13imXinY100% (2)

- Oblicon64 76digestДокумент6 страницOblicon64 76digestJennifer Rabor-MacayanaОценок пока нет

- Timestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumberДокумент30 страницTimestamp TEAM Name CODM Name GLOBE/TM Mobile NumberFeeyell UyОценок пока нет

- Ninth Week CasesДокумент6 страницNinth Week CasesYannah HidalgoОценок пока нет

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsДокумент2 страницыCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Wanted Person of The Week-GanglДокумент1 страницаWanted Person of The Week-GanglHibbing Police DepartmentОценок пока нет

- THINK L2 Unit 1 GrammarДокумент1 страницаTHINK L2 Unit 1 GrammarGabriel Alfonso Coello MartinezОценок пока нет

- Statement by President Uhuru Kenyatta On The Terrorist Attack at Garissa University College, Garissa CountyДокумент5 страницStatement by President Uhuru Kenyatta On The Terrorist Attack at Garissa University College, Garissa CountyState House KenyaОценок пока нет

- Salaah Janazah ShafiiДокумент1 страницаSalaah Janazah ShafiiMuhammad Nabeel0% (1)

- The Spanish Colonial PeriodДокумент1 страницаThe Spanish Colonial PeriodRyan PaderaОценок пока нет

- PAT - Pardo Vs Hercules LumberДокумент1 страницаPAT - Pardo Vs Hercules LumberLorenaОценок пока нет

- Sample Pleading: Motion TO ReconsiderДокумент2 страницыSample Pleading: Motion TO ReconsiderFrank MummaОценок пока нет

- Dissertation On Cyber WarfareДокумент116 страницDissertation On Cyber WarfarePaulo DiasОценок пока нет

- By TelephoneДокумент7 страницBy TelephoneMark Ryan Visaya Mendoza100% (2)

- Strategic Options For Iran: Balancing Pressure With DiplomacyДокумент45 страницStrategic Options For Iran: Balancing Pressure With DiplomacyThe Iran Project100% (3)

- Article CrusadesДокумент27 страницArticle CrusadesPablo RodriguesОценок пока нет

- MHF Legal Coercion Fact Sheets 2016Документ40 страницMHF Legal Coercion Fact Sheets 2016Cale HollowayОценок пока нет

- Probation Law 795-813Документ7 страницProbation Law 795-813LawStudent101412Оценок пока нет

- Impo!Документ4 страницыImpo!Angelino Gutierrez JhonnyОценок пока нет

- Harassment Training and InvestigationsДокумент41 страницаHarassment Training and InvestigationsurjiblateОценок пока нет

- Characteristics of MicroorganismsДокумент11 страницCharacteristics of MicroorganismsGautam DawaОценок пока нет

- Lay Judge JanuaryДокумент331 страницаLay Judge Januaryjmanu9997Оценок пока нет

- The Holy Cross PrayerДокумент15 страницThe Holy Cross PrayerS Dsouza100% (1)

- Araullo v. AquinoДокумент3 страницыAraullo v. Aquinoavocado books100% (1)

- UNITED ARAB EMIRATES - Basic General Knowledge QuestionДокумент3 страницыUNITED ARAB EMIRATES - Basic General Knowledge QuestionSuchita Patel73% (11)

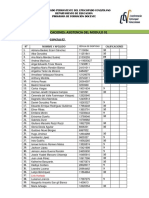

- Calificaciones: Asistencia Del Modulo 01 Docente: Profesor. Henry GonzalezДокумент2 страницыCalificaciones: Asistencia Del Modulo 01 Docente: Profesor. Henry Gonzalezadriana ecarriОценок пока нет

- PetitionДокумент183 страницыPetitionCourtneyОценок пока нет

- Remedies Goodman 2013 OutlineДокумент42 страницыRemedies Goodman 2013 OutlineCocoОценок пока нет

- 233889-2019-Unitrans - International - Forwarders - Inc. - V PDFДокумент7 страниц233889-2019-Unitrans - International - Forwarders - Inc. - V PDFVener MargalloОценок пока нет

- This Graduation SpeechДокумент2 страницыThis Graduation SpeechBry CunalОценок пока нет

- Beltran vs. Makasair (G.R. No. 82827 November 14, 1988)Документ3 страницыBeltran vs. Makasair (G.R. No. 82827 November 14, 1988)Shayne Allen GamboaОценок пока нет

- Christ King Parish, Gogrial, Wau South Sudan: Proposal On Spiritual Enhancement For ParishionersДокумент7 страницChrist King Parish, Gogrial, Wau South Sudan: Proposal On Spiritual Enhancement For Parishionersroselin sahayamОценок пока нет

- Republic VS SerenoДокумент4 страницыRepublic VS SerenoAnonymous VSMpmH1yОценок пока нет