Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Research and Practice: Partners in Care Series - Delirium Opportunity for Comfort in Palliative Care

Загружено:

rizkymutiaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Research and Practice: Partners in Care Series - Delirium Opportunity for Comfort in Palliative Care

Загружено:

rizkymutiaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Research and Practice: Partners in Care Series

Delirium

Opportunity for Comfort in Palliative Care

Downloaded from https://journals.lww.com/jhpn by 02HIoefc+5B5HjTOk3H7y0nfP7VNp0qw3V1ZyYmrD2s8Z/Xqx2JEzbWIpf71zt1fDgRD+dUHFw6q6qV2Vsjau8X0kx82wOMacCmdCtLfsWRqADwLzEUajsuwZIct027TcQyRc3WNPiWPMF1o+NtyKIsmBgu36awfWGpG37nJIkg= on 03/18/2019

Jacqueline F. Close, PhD, RN, GCNS-BC, FNGNA ƒ Carol O. Long, PhD, RN, FPCN

Delirium is a very common neuropsychiatric disorder The purpose of this article is to provide an overview

seen in the very ill and at the end of life and is of delirium, the prevalence, key features, risk factors, sub-

distressing to patients, families, and caregivers. types, pathophysiology, assessment, and evidence-based

Although common, delirium is frequently misdiagnosed nursing interventions, both pharmacologic and nonphar-

and poorly managed. Too often, patients are merely macologic. A case study illustrates the challenges and op-

labeled as confused or agitated. This lack of portunities in caring for hospitalized patients with delirium

recognition, assessment, and treatment can lead to

who may require palliative care. While this article pro-

poor outcomes, including functional decline, new

nursing home placement, and even death. Prompt vides a general overview of delirium in the acute care set-

assessment, prevention, and both pharmacologic and ting, delirium can occur anywhere in the continuum of care,

nonpharmacologic intervention by nurses and the including the home, skilled nursing, outpatient settings, or

interdisciplinary team can significantly reduce distress, hospice settings.

assure comfort, and maximize safety in all care settings.

CASE STUDY: PART 1

KEY WORDS

delirium, interventions, older adult, risk factors

You are the nurse assigned to Mrs Smith and have taken

elirium, or acute confusion, is a very common, care of her for the 3 days. Mrs Smith is an 88-year-old

D serious, and potentially preventable neuropsy-

chiatric disorder that may occur in the very ill

and at the end of life as part of the dying process. Pa-

woman with end-stage heart failure and has a history of

type II diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, numerous urinary

tract infections, and uncontrolled hypertension. She had

been hospitalized four times over the past year for

tients are often labeled as confused or agitated, and no

further assessment or evaluation is done. Delirium fright- exacerbations of heart failure. She recently fell at home,

ens patients and families and also robs patients of valu- fracturing her right hip, and underwent surgery torepair

able time to spend with loved ones. Patients remember her hip. Two days postoperation, she became disoriented

their episode(s) of delirium as very distressing, and delir- and frightened and would not follow nursing instructions.

ium is a negative experience for family members, care- She periodically lashed out at her caregivers and did not

givers, and professional nurses alike.1 Delirium is associated recognize her husband of 65 years. She knew what year it

with emotional distress, as patients with delirium are often was but could not tell where she was or how she got

there. She needed constant reminders to stay in bed

anxious, angry, or depressed. Pain is much more difficult

while she insisted on going to the bathroom (she still had

to treat in patients with delirium, and those with hyperac-

an indwelling bladder catheter). Mrs Smith was awake

tive delirium are at risk for falls and other types of inju-

most of the day and half of the night, vacillating between

ries.2 Delirium also interferes with the patient’s ability to

agitation and lethargy and not quite understanding why

make choices about their care.3 Delirium is one of the ma-

everyone was making her do things that hurt. She

jor contributors to poor health outcomes and often results

received pain medication around-the-clock and was able

in the institutionalization of older adult patients.2

to report her pain levels when asked about them. She

could not hear (her husband took her bilateral hearing

Jacqueline F. Close, PhD, RN, GCNS-BC, FNGNA, is District Clinical aids home because he did not want her to lose them), and

Nurse Specialist for Geriatrics, Palomar Pomerado Health, San Diego, CA. her eyeglasses were lost in the emergency department.

Carol O. Long, PhD, RN, FPCN, is Geriatric Consultant and Codirector, She was unable to report her inability to hear or see well

Palliative Care for Advanced Dementia, Beatitudes Campus, Phoenix, AZ.

without her hearing aids and glasses.

Address correspondence to Jacqueline F. Close, PhD, RN, GCNS-BC,

FNGNA, Palomar Health, 15255 Innovation Dr, San Diego, CA 92129

(Jacqueline.close@pph.org). On day 3 postoperation, Mrs Smith was exhausted and

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose. could not assist with her personal care. Her husband

DOI: 10.1097/NJH.0b013e31825d2b0a came to visit and tried to wake her, but she just opened

386 www.jhpn.com Volume 14 & Number 6 & August 2012

Research and Practice: Partners in Care Series

her eyes and stared blankly at him. She had not used her 70% to 87% of patients were diagnosed with delirium.9

incentive spirometer since early postoperation because Delirium also has been found in 51% to 85% of postYacute

it was on the floor under her bed, where it fell when care admissions.10 Patients with dementia or any cogni-

she was looking for her glasses. Her husband was tive impairment have a very high incidence of delirium

upset that his wife was not ‘‘herself’’ and he could not superimposed on dementia, ranging from 22% to 89%.11

understand what was happening. Nurses complained Delirium is the most common complication experienced

that Mrs Smith was too hard to care for and that she by patients with advanced illness, occurring in up to 85% of

must have ‘‘dementia.’’ patients in the last weeks of life.12 Delirium is also very

common in hospitalized patients, occurring in 26% to

Mrs Smith did not want aggressive treatment while 44% of patients with late-stage cancer and up to 88% of

hospitalized other than surgery for her hip fracture. She patients with terminal illness.13 Fang et al14 speculate that

had gone through many hospitalizations and she told the prevalence of delirium in cancer patients is from 11%

the nurses repeatedly that she ‘‘was tired of going to the to 35%, and in terminal cancer patients, the prevalence

hospital and being so sick,’’ stating that she just wanted may be as high as 85%. In palliative care units, the prob-

to go back home, surrounded by family and friends. ability of developing delirium can be as high as 88%.15

‘‘Terminal restlessness,’’ ‘‘nearing or near death aware-

You suggest that she may have delirium because of

ness,’’ and ‘‘terminal anguish’’ characterize delirium as ‘‘a

her age, surgery, many comorbidities, and hearing and

clinical spectrum of unsettled behaviors in the final days

vision problems. The geriatrics educator trained in

of life.’’16(p345) Despite the fact that delirium is common in

gerontology is contacted to hold an in-service on delirium.

older, very ill patients and as part of the dying process,

nurses can provide significant interventions to reduce dis-

During the impromptu staff in-service, the educator

tress and provide comfort to the patient and family. Delir-

explains that the identification of delirium remains a clin-

ium in people who are terminally ill includes the detection

ical diagnosis, based on bedside observation of the pa-

and elimination of the underlying cause (when possible)

tient and information from families and caregivers.

and nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments.

According to Inouye et al,4 the diagnosis of delirium

Patient and family education and reassurance are para-

should be based on careful bedside monitoring of the

mount to easing anxiety and providing for a therapeutic

four key features of delirium, which include (1) acute

environment.

onset and fluctuating course, (2) inattention, (3) disorga-

nized thinking, and (4) altered level of consciousness.5

Risk Factors

In practice, primary care providers often fail to detect

There are numerous risk factors for developing delirium.

symptoms of delirium, with studies reporting that symptoms

These include predisposing risk factors and precipitating

are documented in only 30% to 50% of affected patients.6

risk factors.

The fluctuating symptoms that characterize delirium make

Predisposing risk factors for delirium are risk factors

it hard to detect, especially when primary care providers

present before the patient becomes ill that may affect a

spend only brief intervals of time with patients. Nurses,

patient’s vulnerability for developing delirium. Some of

on the other hand, spend more time at the bedside and

these predisposing risk factors include advancing age,

therefore have the opportunity to anticipate, assess, and

preexisting cognitive impairment, severity of illness, de-

treat symptoms of delirium across all healthcare settings.

pression, vision or hearing impairment, and functional

impairment.17 Other literature describes all of the same

BACKGROUND predisposing risk factors but also includes male sex, de-

pression, alcohol abuse, abnormal serum sodium level,

Prevalence and Incidence and vision and hearing impairment.17-19 Inouye7 lists the

The risk of developing delirium is positively associated top predisposing factors for developing delirium as (1)

with age, frailty, and the number of chronic and acute baseline cognitive impairment or dementia, (2) severe un-

medical problems. In studies on delirium in hospital set- derlying illness and comorbidity, (3) functional impair-

tings, the prevalence and incidence rates of delirium dif- ment, and (4) advanced age.

fer in the published literature. Delirium has been reported Precipitating risk factors precede the development of

to be present in 14% to 24% of new admissions to the hos- delirium and are any noxious insults or events that hap-

pital. The incidence of new cases of delirium has been pen during an illness regardless of the setting. These risk

shown to be from 6% to 56% in hospitalized patients.7 factors may include medication errors, immobilization,

In a 2003 study by Agnostini and Inouye,8 15% to 53% dehydration, malnutrition, iatrogenic events, medical ill-

of older postoperative adults were diagnosed with delir- nesses, infections, metabolic abnormalities, alcohol or

ium. In another study of patients in an intensive care unit, drug withdrawal, environmental or psychosocial factors,

Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing www.jhpn.com 387

Research and Practice: Partners in Care Series

and the use of indwelling bladder catheters or physical re- behaviors. Mixed delirium is very difficult to diagnose

straints.7 Sleep deprivation, fecal impaction, and urinary re- because of the changing presentation of the patient,

tention are frequent causes for delirium at the end of life. who alternates between a hyperalert and a hypoalert

Delirium is very common in patients with advanced state. An astute assessment and evaluation will capture

cancer and may involve multiple physiological causes the mixed type of delirium, but this may go unnoticed

such as infection, end-stage organ failure, and adverse because of the fluctuations between the two states.

medication events, and in some cases, it is caused by Regardless of the type of delirium the patient is experi-

paraneoplastic syndromes.20 In patients with cancer, de- encing, it is imperative that delirium is prevented, if pos-

lirium may develop from structural or metabolic problems sible, recognized, assessed, documented, and treated to

and complicates the assessment and management of pain, lessen the negative outcomes resulting from this syn-

dyspnea, nausea, anxiety, and other symptoms.20,21 drome. The associated poor outcomes of delirium are

The onset of delirium is acute in most cases, and the very distressing to the patient and family members as well

cardinal clinical symptoms include difficulty sustaining as healthcare professionals, and nursing support is vital to

attention, a fluctuating course, cognitive changes, and al- both the patient and family to lessen fears and anxiety.

tered level of consciousness.22 The patient is unable to

maintain attention for any period of time, and he/she Challenges

may be disoriented to time and place. Perception disor- Delirium has a negative impact on patient outcomes. It is

ders, hallucinations, identification mistakes, and distortion associated with emotional distress, as people with delir-

in the size of objects are frequently noted. ium are often anxious, angry, or depressed. Pain is much

more difficult to treat in patients with delirium, and pa-

Subtypes of Delirium tients with hyperactive delirium are at risk for falls and

Delirium can manifest itself in three different subtypes: other types of injuries.2 In addition, outcomes of patients

hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed delirium. Mixed de- diagnosed with delirium during hospitalization include

lirium includes elements of hyperactive delirium and hy- an increased incidence of functional decline, new nurs-

poactive delirium. ing home placement, and even death.26 Studies indicate

Hyperactive delirium is characterized by agitation, hy- that delirium was associated with increased mortality at

pervigilance, restlessness, emotional instability, halluci- hospital discharge and at 12 months postdischarge.27 De-

nations, and delusions. Patients with hyperactive delirium lirium was also associated with poor functional status

exhibit behaviors most commonly recognized as delirium, among patients with and without dementia.28 Healthcare

and these behaviors include psychomotor hyperactivity costs of patients with delirium are more than 22 times

and excitability. These patients are easily identified by sev- the costs of patients without delirium, and the added finan-

eral associated behaviors, such as fast or loud speech, irri- cial burden can run from $16,303 to $64,421 per person.29

tability, combativeness, impatience, swearing, singing,

laughing, uncooperativeness, euphoria, anger, wandering, Clinical Assessment

distractibility, and nightmares.23 The identification of delirium remains a clinical diagnosis,

Hypoactive delirium is characterized by withdrawal, based on bedside observation of the patient and infor-

flat affect, apathy, lethargy, reduced alertness, and de- mation from families and caregivers. According to Inouye

creased responsiveness. The patient may be somnolent et al,4 the diagnosis of delirium should be based on care-

and exhibit reduced psychomotor activity such as un- ful bedside monitoring of the four key features of delir-

awareness, decreased alertness, sparse or slow speech, ium, which include (1) acute onset and fluctuating course,

slowed movements, staring, and apathy. This is the ‘‘quiet’’ (2) inattention, (3) disorganized thinking, and (4) altered

patient for whom the diagnosis is often missed.23 Patients level of consciousness. Many healthcare providers con-

with hypoactive delirium are often misdiagnosed as de- sider delirium a common and serious problem, yet few

mented or depressed, and at the end of life, hypoactive monitor for this condition, and most admit that it is under-

delirium not only can be mistaken for depression but is diagnosed.30 Fluctuating symptoms make delirium hard to

also difficult to differentiate from opioid sedation.24 detect, especially when primary care providers spend

In palliative care settings, hypoactive delirium can be only brief intervals of time with patients. Nurses, on the

misdiagnosed as depression or fatigue, particularly if a for- other hand, spend more time at the bedside and could

mal assessment is not completed. Using valid and reliable therefore assess for and treat symptoms of delirium across

screening tools for palliative care patients can assist in di- healthcare settings.

agnosing and differentiating delirium, especially when hy-

poactive delirium might otherwise go unrecognized.25 Pathophysiology

The third type of delirium is mixed delirium and in- The pathophysiology of delirium is not completely un-

volves fluctuations between hyperactive and hypoactive derstood, and the proposed causes for delirium are

388 www.jhpn.com Volume 14 & Number 6 & August 2012

Research and Practice: Partners in Care Series

numerous (Table 1). It has been suggested in the litera- The Predictive Model of Delirium explains delirium as

ture that delirium may be a disturbance in cerebral oxygen- the relationship between the vulnerability (predisposing

ation, a disturbance in neurotransmission, a disturbance in risk factors) of the hospitalized older adult and noxious

cytokine production, or a disturbance in plasma esterase insults during (precipitating factors) hospitalization. This

activity.31,32 Patients receiving palliative and end-of-life care relationship can contribute to the development of delir-

are particularly vulnerable for developing delirium. ium.7 This model considers the development of delirium

Delirium can be caused by many different metabolic or related to baseline patient vulnerability and precipitating

ischemic insults to the brain, such as hypoxemia, hyper- factors or noxious insults occurring during hospitaliza-

capnia, hypoglycemia, or any major organ dysfunction. tion. Noxious insults are untoward negative incidents oc-

Trauma, infection, surgery, or any other physical insult curring to a patient while the patient is hospitalized, such

to the body can lead to increased production of proin- as a urinary tract infection directly related to the pres-

flammatory cytokines that, in susceptible patients, induces ence of an indwelling urinary catheter or a patient fall

delirium.32 Peripherally secreted cytokines can intensify sustained during an episode of hyperactive delirium.

responses in the microglia (phagocytes that clean up Highly vulnerable patients (those who have several risk

waste products from the nervous system) that in turn factors) may experience an episode of delirium with few

cause severe inflammation of the brain.32 Proinflamma- noxious insults. On the other hand, patients with low

tory cytokine levels have been shown to be elevated in vulnerability (few risk factors) may need to experience

patients with delirium.33 several noxious insults to trigger an episode of delirium.7

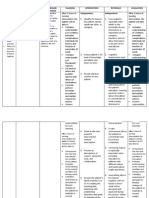

TABLE 1 Differential Diagnosis of Delirium, With Interventions

Causes Differential Diagnosis Intervention

Infection HIV, sepsis, pneumonia Treat infections, use antibiotics as

needed, supportive care

Withdrawal Alcohol, barbiturate, sedative-hypnotic Discontinue or decrease medications,

monitor and treat withdrawal symptoms

Acute metabolic disorders Acidosis, alkalosis, electrolyte Treat metabolic/nutritional/fluid

disturbance, hepatic failure, renal failure disturbances, hepatic and renal failure

Trauma Closed head injury, heat stroke, Close monitoring, cool slowly for heat

postoperative state, severe burns stroke, supportive care

Central nervous system pathology Abscess, hemorrhage, hydrocephalus, Antibiotics, surgery, antiseizure

subdural hematoma, infection, seizures, medications, treat the cause

stroke, tumors, metastases, vasculitis,

encephalitis, meningitis, syphilis

Hypoxia Anemia, carbon monoxide poisoning, Provide oxygen, supportive care, blood

hypotension, pulmonary or product replacement

cardiac failure

Deficiencies Vitamin B12, folate, niacin, thiamine Treat /correct deficiencies

Endocrinopathies Hyperadrenocorticism/ Treat the cause, correct imbalances

hypoadrenocorticism, hyperglycemia/

hypoglycemia, myxedema,

hyperparathyroidism

Acute vascular conditions Hypertensive encephalopathy, stroke, Treat the cause

cardiac arrhythmia, shock

Toxins or drugs Prescription drugs, illicit drugs, pesticides, Discontinue or decrease medications

chemical solvents

Heavy metals Lead, manganese, mercury Clear from system

Adapted with permission from Delirium and Cognitive Impairment Study Group, Vanderbilt University Medical Center (January 15, 2012;

http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/icudelirium).

Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing www.jhpn.com 389

Research and Practice: Partners in Care Series

Assessment and Measurement Tools the detailed reference list at the end of this article). Table 2

describes the assessment tools used in screening, diagnos-

Screening Instruments ing, and determining the severity of delirium.

Screening instruments identify the presence of cognitive Delirium is very common at the end of life, but if as-

impairment but do not diagnose delirium.34 The Mini- sessed and identified early, interventions may be put in

Mental State Examination is used to evaluate cognitive place to lessen the symptoms and ensure the patient’s

changes and assesses orientation, instantaneous recall, comfort along with patient and family well-being. The

short-term memory, attention, constructional capacities, most important approach to treatment of delirium is to

and use of language.35 The NEECHAM Confusion Scale reverse underlying causes if possible, and in palliative

is used for a rapid assessment as well as monitoring of care, the goals of treatment for delirium are balanced

acute confusion in hospitalized older individuals.36 The with a caring approach, providing a safe environment,

Delirium Observation Screening Scale is an assessment and avoiding uncomfortable interventions. Addressing

tool designed to assist nurses in the early recognition of only one of the factors contributing to the delirium is

delirium during regular care and is based on the Diag- not likely to help improve the delirium. However, a mul-

nostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth tifactorial intervention strategy that addresses as many

Edition (DSM-IV), criteria for delirium.37 The Nursing De- predisposing and precipitating factors as possible sup-

lirium Screening Scale is an observational five-item instru- ports positive nursing care.

ment designed to be completed in 1 minute and is a

simple, yet accurate, continuous, ‘‘around-the-clock symp-

tom monitoring.’’38(p373) The tool of choice should be the CASE STUDY: PART 2

one best suited for the patient population being screened.

Diagnostic Instruments On day 4, Nancy, Mrs Smith’s daughter, came to visit

Diagnostic instruments are an adjunct to clinical and cog- after her father had called her to express his deep

nitive evaluation and help in diagnosing delirium.39 The concern and worry about his wife’s condition. The

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) is a diagnostic tool nursing staff was very adept at using the CAM to assess

designed for use by a nonpsychiatrically trained inter- for delirium, and Mrs Smith was positive on the first

viewer to identify and recognize delirium quickly and ac- assessment and continued to score positively for the next

curately both at the bedside and in research settings.5 three assessments, done 8 hours apart. Nancy works

The CAM is used as the primary tool to screen residents with the older adult population in a hospital and

in nursing homes.40 The Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 immediately suspected that her mother was experiencing

is used both as a diagnostic and severity-based instrument delirium. The primary care nurse talked at length with

based on the DSM-IV and common symptoms found in Nancy about the numerous predisposing risk factors that

delirious patients. This is used to rate the severity of delir- made her mother vulnerable to delirium, including

ium over time and differentiates patients with delirium from advanced age, severity of illness, and comorbidities such

patients with dementia, schizophrenia, and depression.41,42 as heart failure, diabetes, osteoarthritis, a history of

urinary tract infections, hypertension, and diminished

Severity of Symptom Instruments vision and hearing. Since her admission, Mrs Smith

These scales are used to rate the severity of the symp- also had several precipitating risk factors for delirium,

toms of delirium. The Memorial Delirium Assessment including numerous medications, immobilization,

Scale (MDAS) is a brief, reliable tool for assessing delir- dehydration, malnutrition, an indwelling bladder catheter

ium severity among medically ill, adult patients and can (risk for urinary tract infection), and sleep deprivation.

be accurately scored by multiple raters. The MDAS is

highly correlated with existing measures of delirium The nurse and Nancy discussed the numerous risk

and cognitive impairment.42 The Bedside Confusion factors, and together, they developed a comprehensive

Scale (BCS) is used for continuous observation of an al- plan of care. The care plan included safety measures to

teration in attention, with or without a change in level of minimize the risk of falling, the discontinuation of the

consciousness. The BCS is designed for the palliative indwelling bladder catheter after a sample was sent for

medicine population, requires minimal training, and takes urinalysis, the continuous evaluation of the effectiveness

approximately 2 minutes to complete.43 The Delirium In- and side effects of her pain medications, and respiratory

dex measures the severity of symptoms of delirium and treatments, including assistance in using the incentive

is based on observation of the patient, without additional spirometer. A chest x-ray was ordered, which revealed

information from informants.44 (For additional details on atelectasis in both lower lobes and consolidation on the

the psychometric properties of each instrument, consult left. Antibiotics were started because she had developed

390 www.jhpn.com Volume 14 & Number 6 & August 2012

Research and Practice: Partners in Care Series

TABLE 2 Tools Used to Assess Delirium4,35,37,38,41/45

Description

Screening tool

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)35 The MMSE was initially created to differentiate organic from functional

psychiatric patients. Used to quantify the severity of cognitive impairment and

to document changes over time. The MMSE can be administered in 5-10 min.

It has seven different categories: orientation to time, orientation to place,

registration of three words, attention and calculation, recall of three words,

language and visual construction.

NEECHAM Confusion Scale (NCS)44 The NCS consists of nine scaled items divided into three subscales: level

of responsiveness, behavior, and vital functions (screening, not diagnostic).

The NCS involves bedside observation and interaction with the patient and

incorporates data from a nurse’s assessment of patient responses.

Delirium Observation Screening Scale (DOS)37 The DOS is designed to assist nurses in the early recognition of delirium

during regular care.

Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (NuDESC)38 The NuDESC is an observational five-item scale that can be completed quickly

and was developed for use in busy inpatient units.

Diagnostic instruments

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) The CAM and CAM-ICU are diagnostic, observational instruments based on

and CAM-ICU4 the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

Intended to provide a standardized method to enable nonpsychiatrically

trained clinicians to identify delirium quickly and accurately in both clinical and

research settings. The CAM-ICU was designed to be used in an environment

when the patient is nonverbal/mechanically ventilated.

Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 The DRS-R-98 is the most widely used instrument for rating the severity

(DRS-R-98)41 of delirium over time and consists of 16 items: three are diagnostic of

delirium and 13 are severity-based symptoms found in people with delirium.

The total score is diagnostic of delirium and a severity score indicates

increased delirium symptoms.

Severity of symptom instruments

Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS)42 The MDAS is a 10-item scale used to quantify severity of delirium and detect

changes in symptoms. The MDAS assesses arousal, level of consciousness,

cognitive functioning (memory, attention, orientation, disturbances in

thinking), and psychomotor activity.

Bedside Confusion Scale (BCS)43 The BCS incorporates a 2-min screening test to observe the level of

consciousness at the time of clinical interaction, followed by a timed

task of attention using recitation of the months of the year backward.

Delirium Index45 The Delirium Index measures the severity of symptoms of delirium based

on observation of the patient, without additional information from family,

nursing, or the medical chart. It is designed to be used with the MMSE.

a urinary tract infection in addition to pneumonia. Nancy were provided continuously, facilitating her mother’s

decided to stay with her mother in her hospital room to recovery. Mrs Smith’s husband brought in her hearing

provide a familiar presence because that would help aids and glasses as well as familiar objects from home.

keep her mother calm and oriented. Nancy also helped A calendar and clock were placed where she could see

physical therapy mobilize her mother to prevent them, and pictures of her grandchildren were put on the

functional decline. Nancy also assisted with and insisted bedside table.

that her mother use the incentive spirometer to expand

her lungs and facilitate optimal oxygen exchange. Mrs Smith had a written advance directive for healthcare

With Nancy at her mother’s bedside, food and fluids and named her husband as durable power of attorney.

Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing www.jhpn.com 391

Research and Practice: Partners in Care Series

Over the last couple of years, both Mr and Mrs Smith ing some distress.46 Aromatherapy may be useful in

had many conversations about treatment options should reducing anxiety in palliative care patients. For example,

they not be able to make their own decisions. Nancy sandalwood oil may be effective in reducing anxiety

and Mr Smith also made it clear to the medical and when used as massage oil. 47 Gentle massage to the

nursing staff that Mrs Smiths’ wishes were not aggressive hands and/or feet may help relieve anxiety and quiet

treatment, but palliative care. Advance directives were agitation.

reviewed and orders were clarified to ensure that Nurses intuitively know how to provide the best,

Mrs Smith’s wishes were respected and supported. evidence-based care for their patients and are therefore

The palliative care team was consulted and became at the forefront of delirium prevention. Nurses are also

involved in Mrs Smith’s care. The family, primary vital to the well-being of their patients and derive great

care provider, nurses, and palliative care team worked satisfaction when those same patients have improved

collaboratively with Mrs Smith and her family to and shown progress after an episode of delirium.

ensure comfort and symptom control without

aggressive treatment. Pharmacological Treatment of Delirium

Treatment of delirium is aimed at removing or treating

Nursing Interventions the underlying cause. The decision to treat with medica-

Delirium is a medical emergency, and the goals of care tion will depend on the patient’s distress or the risk that

are to (1) provide safety for the patient (2) identify the the behaviors pose to self or others.48 When using med-

cause, and (3) treat the cause when possible or appropri- ications in the older adult population, it is imperative to

ate. Treatment focuses on the use of nonpharmacologic start low and go slow and the medications are titrated to

(nursing interventions) and pharmacologic therapy as effect.48 Haloperidol is most often recommended be-

needed, and the foundational principle is to treat the un- cause it has fewer anticholinergic side effects, is less se-

derlying cause. In palliative care, treatment of the cause dating, has fewer active metabolites, and rarely causes

or causes may not be feasible or possible related to the orthostatic hypotension or cardiovascular side effects.46

disease process, and the goals of care will change as the Second-line atypical agents for treatment of delirium

disease progresses. However; patient safety, patient are olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine.49 Benzodi-

well-being, and patient comfort are the cornerstone of azepines are not recommended for delirium in older

excellent palliative nursing care. adults because of the risk of rebound confusion, agita-

The first priority for nursing is to maintain a safe, fa- tion, and risk for falls. These drugs can cause oversedation

miliar environment for the patient, whether the setting is and exacerbate confusion.

the hospital, hospice, long-term care, or home. Low non- In addition, haloperidol is contraindicated for patients

glare lighting will prevent visual distortions. Surrounding with Parkinson disease or Lewy body dementia.

the patient with familiar objects, such as family photos or

favorite possessions, will provide comfort. Having a

clock and calendar within sight will help the patient stay CASE STUDY: PART 3

in the present. Any object of comfort should be placed

within reach for reassurance. Reorientation to time, place,

and person when and if appropriate is often helpful. Soft, On her fifth postoperative day, Mrs Smith was walking

soothing music may promote a healing environment. with the aid of a front-wheeled walker; she was alert

Gentle reorientation and reassurances that you will keep to her baseline, was eating and drinking without

them safe may help. Glasses and hearing aids must be in encouragement, and seemed ready for discharge to

working order and properly placed to maximize commu- her home with home healthcare. Prior to discharge, a

nication. Family members should be allowed to stay with medical social worker held a family conference to ensure

the patient, especially if the surroundings are unfamiliar, that the plan of care was clear for Mrs Smith. The

such as in a hospital, hospice, or palliative care unit. Phys- palliative care team collaborated with Mrs Smith and

ical restraints should never be used because they are a spent time with her and her family to make certain all

precipitating risk factor for delirium and can escalate the understood the goals of care. Mrs Smith was adamant

behaviors rather than alleviate them. Education and sup- that she would not undergo any further diagnostic tests

port are imperative in assisting families through this diffi- or aggressive treatments for her heart failure. She wanted

cult time, as they may not understand their loved one’s to spend what time she had at home with family and

behaviors. The bedside nurse is in the ideal situation to friends. This was vitally important to her. The palliative

provide much needed comfort and assurance. care team assured Mrs Smith and her family that her

Familiar sights, sounds, smells, and touches may per- wishes would be followed and they were there to

haps provide a sense of security and also assist in reliev- support her. Mrs Smith’s husband and daughter agreed

392 www.jhpn.com Volume 14 & Number 6 & August 2012

Research and Practice: Partners in Care Series

with her wishes as they realized she would not want to 9. Pisani MA, McNicoll L, Inouye SK. Cognitive impairment in the

live if she had no quality of life to do the things that intensive care unit. Clin Chest Med. 2003;24(4):727-737.

10. Kiely DK, Bergmann MA, Jones RN, Murphy KM, Orav EJ,

brought her joy. Mercantonio ER. Characteristics associated with delirium per-

sistence among newly admitted post-acute facility patients.

J Geront A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(4):344-349.

Summary 11. Fick DM, Agnostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed

Delirium is stressful for both the patient and family on dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:

across all settings. The prevalence is highest in vulner- 1723-1732.

12. Breitbart W, Alici Y. Agitation and delirium at the end of life;

able populations and particularly for older individuals,

‘‘We couldn’t manage him’’. JAMA. 2008;300(24):2898-2910.

in intensive care units, those who are postoperative, 13. Keeley P. Delirium at the end of life. Am Fam Physician. 2010;

and those with advanced illness.44 The predisposing risk 81(10):1260-1261.

factors of advanced age, severity of illness, multiple co- 14. Fang CK, Chen HW, Liu SI, Lin CJ, Tsai LY, Lai YL. Prevalence,

detection and treatment of delirium in terminal cancer inpatients:

morbidities, and vision and hearing impairments, as well a prospective survey. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38(1):56-63.

as her fall and subsequent surgery to repair her fractured 15. Michaud L, Burnand B, Stiefel F. Taking care of the terminally ill

hip, left Mrs Smith very vulnerable to delirium. The pre- cancer patient: delirium as a symptom of terminal disease. Ann

cipitating risk factors, or the events happening after hos- Oncol. 2004;15(4):199-203.

16. White C, McCann MA, Jackson N. First do no harmIterminal

pitalization, contributed to Mrs Smith’s delirium, which restlessness or drug-induced delirium. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(2):

included immobilization, dehydration, malnutrition, uri- 345-351.

nary tract infection, pneumonia, and sleep deprivation. 17. Sendelbach S, Guthrie PF. Evidence-based guideline: acute

These predisposing and precipitating risk factors alert confusion/delirium, identification, assessment, treatment, and

prevention. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(11):11-18.

nursing staff that delirium is an acute onset that requires 18. Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health. National Guidelines

immediate intervention. Nurses play a key role in the for Seniors’ Mental Health: The Assessment and Treatment of

prevention and recognition of delirium, thus contributing Delirium. Toronto, ON: Canadian Coalition for Seniors Mental

to optimal outcomes for hospitalized patients. An array Health; 2006.

19. Capezuti E, Zwicker D, Mezey M, Fulmer T. eds. Evidence-

of interventions that range from safety to comfort must Based Geriatric Nursing Protocols for Best Practice. 3rd ed.

be considered for the patient experiencing delirium, re- New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2008.

gardless of setting. Palliative care teams can provide sup- 20. Friedlander MM, Brayman Y, Breitbart WS. Delirium in palliative

care. Oncology. 2004;18(2):1-15. http://www.psychiatrictimes

port and assistance in symptom control, pain management, .com/display/article/10165/104938. Accessed October, 2011.

and family support. The patient and family goals for pallia- 21. Cobb JL, Glantz MJ, Nicholar PK, et al. Delirium in patients with

tive care are a difficult balancing act for all involved but, cancer at the end of life. Cancer Pract. 2008;(4):172-177.

when done well, bring comfort to those for whom we care. 22. Alvarel-Fernandez B, Formiga F, Gomez R. Delirium in hospita-

lized older persons: review. J Nutr. 2007;12(4):246-251.

23. Milisen K, Braes T, Fick DM, Foremann MD. Cognitive assessment

and differentiating the 3 Ds (dementia, depression, delirium). Nurs

References Clin North Am. 2006;41(1):1-22.

1. Breitbart W, Gibson C, Tremblay A. The delirium experience: 24. Inouye SK, Foreman MD, Mion LC, Katz KH, Cooney LM.

delirium recall and delirium-related distress in hospitalized Nurses’ recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison

patients with cancer, their spouses/caregivers, and their of nurse and researcher ratings. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:

nurses. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(3):183-194. 2467-2473.

2. Tullman DF, Mion LC, Fletcher K, Foreman MD. Delirium: 25. Spiller JA, Keen JC. Hypoactive delirium: assessing the extent of

prevention, early recognition, and treatment. In: Capezuti E, the problem for inpatient specialist palliative care. Palliat Med.

Zwicker D, Mezey M, Fulmer T. Evidence-Based Geriatric 2006;20(1):17-23.

Nursing Protocols for Best Practice, 3rd ed. New York: Springer 26. Inouye SK, Rushing JT, Foreman MD, Palmer RM, Pompei P. Does

Publishing; 2008:111-125. delirium contribute to poor hospital outcomes? J Gen Intern Med.

3. Paolini CA. Symptom management at the end of life. J Osteopath 1998;13:234-242.

Assoc. 2001;101(10):609-615. 27. Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD. Occurrence and outcomes of

4. Inouye SK, vanDyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz, RI. delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review.

Clarifying confusion: the Confusion Assessment Method; a new Age Aging. 2006;35:350-364.

method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12): 28. McCusker J, Cole M, Dendukuri N, Belzile E, Primeau F. Delirium

941-948. in older medical inpatients and subsequent cognitive and

5. Inouye SK. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM): Training functional status: a prospective study. Can Med Assoc J. 2001;

Manual and Coding Guide. New Haven, CT: Yale University 165(5):573-583.

School of Medicine; 2003. 29. Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, Leo-Summers L, Inouye SK.

6. Francis J. Delirium in older patients. J Am Gerontol Soc. 1992; One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly.

40(8):829-838. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:27-32.

7. Inouye SK. Delirium in hospitalized older patients. Clin Geriatr 30. Ely EW, Stephens RK, Jackson JC, et al. Current opinions

Med. 1998;14(4):745-764. regarding the importance, diagnosis, and management of

8. Agnostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium. In: Hazzard WR, Blass JP, delirium in the intensive care unit: a survey of 912 health care

Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, eds. Principles of Geriatric professionals. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:106-112.

Medicine and Gerontology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 31. Gunther M, Morandi A, Ely W. Pathophysiology of delirium in

2003:1503-1515. the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;24:45-65.

Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing www.jhpn.com 393

Research and Practice: Partners in Care Series

32. Maldonado JR. Pathoetiological model of delirium: a com- Heidrich DE, Esper P, eds. Palliative & End-of-Life Care:

prehensive understanding of the neurobiology of delirium and Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2nd ed. St Louis: Saunders

an evidence-based approach to prevention and treatment. Crit Elsevier; 2007:327-348.

Care Clin. 2008;24:789-856. 42. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Roth A, Smith MJ, Cohen K, Passik S.

33. Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom

diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5: Manage. 1997;13(3):128-137.

210-220. 43. Stillman MJ, Rybicki MS. The Bedside Confusion Scale:

34. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘‘Mini-mental state’’: a development of a portable bedside test for confusion and its

practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients application to the palliative medicine population. J Palliat Med.

for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198. 2000;3(4):449-456.

35. Neelon VJ, Champagne MT, Carlson JR, Funk SG. The NEECHAM 44. Heidrich DE, English N. Delirium, confusion, agitation, and

confusion scale: construction, validation, and clinical testing. Nurs restlessness. In: Ferrell BR, Cole N, eds. Oxford Textbook of

Res. 1996;45(6):324-330. Palliative Nursing. 3rd ed. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press;

36. Schuurmans MJ, Shortidge-Baggett LM, Duursma SA. The 2010:449-467.

Delirium Observation Screening Scale: a screening instrument 45. McCusker J, Cole MG, Dendukuri N, Belzile E. The Delirium

for delirium. Res Theor Nurs Pract. 2003;17(1):31-50. Index, a measure of the severity of delirium: new findings on

37. Gaudreau JD, Gagnon P, Harel F, Tremblay A, Roy MA. Fast, reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;

systematic, and continuous delirium assessment in hospitalized 32:1744-1749.

patients: the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale. J Pain Symptom 46. Kyle G. Evaluating the effectiveness of aromatherapy in reducing

Manage. 2005;29(4):368-375. levels of anxiety in palliative care patients. Complement Ther Clin

38. RAND MDS 3.0 Final Study Report and Appendices. https:// Pract. 2006;12(2);148-155.

www.cms.gov/NursingHomeQualityInits/25_NHQIMDS30asp# 47. Segatore M, Adams D. Managing delirium and agitation in elderly

TopOfPage. Accessed October, 2011. hospitalized orthopaedic patients: part 2Vinterventions. Orthop

39. Kuebler KK, Heidrich DE, Esper P. Palliative & End-of-Life Care: Nurs. 2001;20(2):61-73.

Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2nd ed. St Louis, MO: Saunders 48. Schwartz TL, Masand PS. The role of atypical antipsychotics in

Elsevier; 2007. the treatment of delirium. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(3):171-174.

40. Tzepacz PT. The Delirium Rating Scale: its use in consultation- 49. Vanderbilt Medical Center. ICU Delirium and Cognitive Impairment

liaison research. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(3):193-204. Study Group. www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/icudelirium. Accessed

41. Vena C. Delirium and acute confusion. In: Kuebler KK, December 13, 2011.

For more than 80 additional continuing education articles related to geriatrics, go to NursingCenter.com\CE.

394 www.jhpn.com Volume 14 & Number 6 & August 2012

Вам также может понравиться

- NCP Knowledge Deficit (FINAL)Документ8 страницNCP Knowledge Deficit (FINAL)Nikki Ricafrente89% (9)

- The List of Health Conditions or Problems Ranked According To Priorities: Problem Score 4Документ25 страницThe List of Health Conditions or Problems Ranked According To Priorities: Problem Score 4Sytrose Morales100% (2)

- An Analysis of Ethical Issues in Pharmaceutical IndustryДокумент19 страницAn Analysis of Ethical Issues in Pharmaceutical IndustrySuresh KodithuwakkuОценок пока нет

- 3 Behavioral Neurology and Psychiatry (045-075)Документ31 страница3 Behavioral Neurology and Psychiatry (045-075)Eliana NataliaОценок пока нет

- Nursing Fundamentals Exam ReviewДокумент10 страницNursing Fundamentals Exam ReviewAlain CheryОценок пока нет

- Mod 3 Guidelines in Giving Emergency CAreДокумент5 страницMod 3 Guidelines in Giving Emergency CArerez1987100% (2)

- ShawHenry RadiographicPositioning TVTechMarApr2017Документ13 страницShawHenry RadiographicPositioning TVTechMarApr2017Leahjen MaeОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Ca CerviksДокумент11 страницJurnal Ca CerviksSilvia Ibnu HibanОценок пока нет

- Frailty For Neurologists - A Practical GuideДокумент8 страницFrailty For Neurologists - A Practical GuideAlphaОценок пока нет

- The Medicalization of Nursing The Loss of A Discipline's Unique IdentityДокумент8 страницThe Medicalization of Nursing The Loss of A Discipline's Unique IdentityМарго КоваленкоОценок пока нет

- Patient-Reported Outcomes, Functional Assessment, of GalucomaДокумент8 страницPatient-Reported Outcomes, Functional Assessment, of GalucomaLidya OctaliaОценок пока нет

- Care, Compassion, and Communication in Professional Nursing: Art, Science, or BothДокумент1 страницаCare, Compassion, and Communication in Professional Nursing: Art, Science, or Bothtatsuya kikuchiОценок пока нет

- Quality Improvement Proposal WorksheetДокумент8 страницQuality Improvement Proposal Worksheetapi-465165917Оценок пока нет

- BCMJ Vol59 No3 DeliriumДокумент6 страницBCMJ Vol59 No3 Deliriummohamad safiiОценок пока нет

- NCP CholetiasisДокумент4 страницыNCP CholetiasisAngela AyalaОценок пока нет

- AJGP 12 2019 Focus Patel Palliative Sedation WEB PDFДокумент8 страницAJGP 12 2019 Focus Patel Palliative Sedation WEB PDFFrancisco Rodriguez de NarvaezОценок пока нет

- Department of Geriatric Medicine: Faculty of Medical and Health SciencesДокумент48 страницDepartment of Geriatric Medicine: Faculty of Medical and Health SciencesJosephОценок пока нет

- How Can Students Diagnostic Competence Benefit.32Документ7 страницHow Can Students Diagnostic Competence Benefit.32Carlos Roberto Pires de Oliveira LimaОценок пока нет

- Perspective A Culture of Respect, Part 1 The.10Документ8 страницPerspective A Culture of Respect, Part 1 The.10alejandromfunes1749Оценок пока нет

- Addressing Pediatric Intoeing in Primary CareДокумент5 страницAddressing Pediatric Intoeing in Primary CareAbraham SaldañaОценок пока нет

- HS - Agianto - Health CornerДокумент10 страницHS - Agianto - Health CornerIndo Barca BanjarbaruОценок пока нет

- Hypoactive Delirium: Christian Hosker, David WardДокумент5 страницHypoactive Delirium: Christian Hosker, David Wardjohnny chawОценок пока нет

- How To Approach Ethical Dilemmas in A PandemicДокумент3 страницыHow To Approach Ethical Dilemmas in A PandemicAlexandra DeniseОценок пока нет

- Permj18 2p0077Документ9 страницPermj18 2p0077Vaishnavi AgrawalОценок пока нет

- Communicating With PatientsДокумент18 страницCommunicating With PatientsFranco Fabricio CarpioОценок пока нет

- Pemphigus VulgarisДокумент2 страницыPemphigus Vulgariszendah123Оценок пока нет

- Clinical Assessment and Management of Delirium in The Palliative Care SettingДокумент21 страницаClinical Assessment and Management of Delirium in The Palliative Care SettingrizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- PATIENT EDUCATION PLANДокумент4 страницыPATIENT EDUCATION PLANGina PrancelisoОценок пока нет

- Caring FundamentalДокумент10 страницCaring FundamentalDivaviyaОценок пока нет

- Malnutritie Adulti DefinitiДокумент6 страницMalnutritie Adulti DefinitiNarcisa CovataruОценок пока нет

- Independent: IndependentДокумент6 страницIndependent: IndependentGina PrancelisoОценок пока нет

- Ethical and Professional Conduct of Medical Students: Review of Current Assessment Measures and ControversiesДокумент6 страницEthical and Professional Conduct of Medical Students: Review of Current Assessment Measures and ControversieslamyaaОценок пока нет

- Dementia NCPДокумент3 страницыDementia NCPDonnalyn MillaresОценок пока нет

- Dexmedetomidina Sedación UCIДокумент12 страницDexmedetomidina Sedación UCIVlady78Оценок пока нет

- Palliative Care in Hospital, Hospice, at Home Results From AДокумент8 страницPalliative Care in Hospital, Hospice, at Home Results From AFemma ElizabethОценок пока нет

- Practice Modification For Pandemics: A Model For Surge Planning in ObstetricsДокумент15 страницPractice Modification For Pandemics: A Model For Surge Planning in ObstetricsJhuliana CabreraОценок пока нет

- Cataract Medical/Nursing MGMTДокумент4 страницыCataract Medical/Nursing MGMTNicosia Mae FerrerОценок пока нет

- Recognizingmalnutritioninadults JPEN2013Документ7 страницRecognizingmalnutritioninadults JPEN2013Joon HyungОценок пока нет

- Nursing Care Plan - D & CДокумент2 страницыNursing Care Plan - D & Cderic89% (18)

- Horticultural Therapy in ClassroomДокумент6 страницHorticultural Therapy in ClassroomEzlin ZamriОценок пока нет

- Subjective:: Assessment Nursing Diagnosis Planning Interventi ONS Rationale EvaluationДокумент2 страницыSubjective:: Assessment Nursing Diagnosis Planning Interventi ONS Rationale EvaluationCuttie Anne GalangОценок пока нет

- Generic Care PlanДокумент30 страницGeneric Care PlanMaria Belen Rivera PaspuelОценок пока нет

- The Patient-as-Partner Approach in Health Care: A Conceptual Framework For A Necessary TransitionДокумент5 страницThe Patient-as-Partner Approach in Health Care: A Conceptual Framework For A Necessary TransitionmilananandОценок пока нет

- A Medical Director's PerspectiveДокумент2 страницыA Medical Director's Perspectiveacma2010Оценок пока нет

- presentation12Документ1 страницаpresentation12api-286232866Оценок пока нет

- Commentary: Challenges in Managing Sleep Problems in Young ChildrenДокумент1 страницаCommentary: Challenges in Managing Sleep Problems in Young ChildrenCT TANОценок пока нет

- Blinding: Linking Evidence To PracticeДокумент2 страницыBlinding: Linking Evidence To PracticeTomáš KrajíčekОценок пока нет

- Preeclampsia Pathophysiology and Implications For.9Документ8 страницPreeclampsia Pathophysiology and Implications For.9BiBiana PinToОценок пока нет

- Think Before You Administer: Is Routine Benzodiazepine Premedication Before Endoscopy in Adults Necessary?Документ3 страницыThink Before You Administer: Is Routine Benzodiazepine Premedication Before Endoscopy in Adults Necessary?Irak TorresОценок пока нет

- Ha JournalДокумент1 страницаHa JournalDianne UlandayОценок пока нет

- Nursing Theory AnalysisДокумент2 страницыNursing Theory AnalysisMarielle Ann RumbaoaОценок пока нет

- Patient AdvocacyДокумент2 страницыPatient AdvocacyM_LXОценок пока нет

- Critical Care Nursing Assessment PrioritiesДокумент3 страницыCritical Care Nursing Assessment PrioritiesBunnie AlphaОценок пока нет

- Bipolar 1 Disorder NCPДокумент3 страницыBipolar 1 Disorder NCPJoy-Rena Sabinay OchondraОценок пока нет

- Caring For Elderly Patients With Dementia Nursing PDFДокумент11 страницCaring For Elderly Patients With Dementia Nursing PDFElla OrtizОценок пока нет

- Caring For Elderly Patients With Dementia Nursing PDFДокумент11 страницCaring For Elderly Patients With Dementia Nursing PDFAhmed MasoudОценок пока нет

- Communication skills critical to ICU careДокумент4 страницыCommunication skills critical to ICU careWahyu HidayatiОценок пока нет

- Rehabilitation in Transverse MyelitisДокумент16 страницRehabilitation in Transverse MyelitisDaurian GarrandesОценок пока нет

- Dienizs Labini BSN-3E Brain Cancer Activities: B. Glioblastoma MultiformeДокумент11 страницDienizs Labini BSN-3E Brain Cancer Activities: B. Glioblastoma MultiformeDienizs Labini TadenaОценок пока нет

- Physician Decision Making and Cardiac RiskДокумент17 страницPhysician Decision Making and Cardiac RiskRenato Ferreira Leitão AzevedoОценок пока нет

- Treatment of Bacterial Vaginosis What WeДокумент13 страницTreatment of Bacterial Vaginosis What WeMohammed shamiul ShahidОценок пока нет

- EC MultiRadience Nov20 DPS HRДокумент2 страницыEC MultiRadience Nov20 DPS HRventasОценок пока нет

- Download ebook Feline Behavioral Health And Welfare Prevention And Treatment Pdf full chapter pdfДокумент67 страницDownload ebook Feline Behavioral Health And Welfare Prevention And Treatment Pdf full chapter pdfjohn.nelsen65896% (23)

- Restraints in Dementia Care: A Nurse’s Guide to Minimizing Their UseОт EverandRestraints in Dementia Care: A Nurse’s Guide to Minimizing Their UseОценок пока нет

- Pain Management Guidelines 15-11-2012Документ62 страницыPain Management Guidelines 15-11-2012Galuh NurfadillahОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S000293941200325X Main PDFДокумент10 страниц1 s2.0 S000293941200325X Main PDFrizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- SOP Aromaterapi PDFДокумент1 страницаSOP Aromaterapi PDFrizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- Effectiveness of Silexan Oral Lavender Essential.13Документ10 страницEffectiveness of Silexan Oral Lavender Essential.13rizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- Intraocular Pressure Lowering Effect Of.98364Документ16 страницIntraocular Pressure Lowering Effect Of.98364rizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- Initial Management of APACДокумент8 страницInitial Management of APACrizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- Clinical Assessment and Management of Delirium in The Palliative Care SettingДокумент21 страницаClinical Assessment and Management of Delirium in The Palliative Care SettingrizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- Research and Practice: Partners in Care Series - Delirium Opportunity for Comfort in Palliative CareДокумент9 страницResearch and Practice: Partners in Care Series - Delirium Opportunity for Comfort in Palliative CarerizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- Management of Delirium in Palliative Care: A Review: Current Psychiatry Reports March 2015Документ10 страницManagement of Delirium in Palliative Care: A Review: Current Psychiatry Reports March 2015rizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- INTRAOCULAR Retinal Thickness in Poag and NTGДокумент10 страницINTRAOCULAR Retinal Thickness in Poag and NTGrizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- General, Medical and Health Information: Lifestyle & Diabetes QuestionnaireДокумент10 страницGeneral, Medical and Health Information: Lifestyle & Diabetes QuestionnairerizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- Surgical Management GlaucomaДокумент13 страницSurgical Management Glaucomanisa_kartikaОценок пока нет

- Effect of Antiplatelet Anticoagulant Use On.98326 PDFДокумент30 страницEffect of Antiplatelet Anticoagulant Use On.98326 PDFrizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- 2018 Article 135Документ15 страниц2018 Article 135rizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- W Morgan Glaucoma Surgery Review CEO 2012Документ4 страницыW Morgan Glaucoma Surgery Review CEO 2012rizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- Surgical Management GlaucomaДокумент13 страницSurgical Management Glaucomanisa_kartikaОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S000293941200325X Main PDFДокумент10 страниц1 s2.0 S000293941200325X Main PDFrizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- Pex Syndrome and Pexg-LiteraturesДокумент9 страницPex Syndrome and Pexg-LiteraturesrizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- Jurnal NaloxoneДокумент16 страницJurnal NaloxonerizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- Jurnal 6Документ6 страницJurnal 6rizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S000293941200325X MainДокумент11 страниц1 s2.0 S000293941200325X MainrizkymutiaОценок пока нет

- Single-payer health care reduces inequality gapsДокумент52 страницыSingle-payer health care reduces inequality gapsMetelitswagОценок пока нет

- Pancreatic Cancer Therapeutics in Major Developed Markets To 2021Документ7 страницPancreatic Cancer Therapeutics in Major Developed Markets To 2021Kanchan JagtaniОценок пока нет

- Standard Surgical Attire Surgical ScrubДокумент20 страницStandard Surgical Attire Surgical ScrubzekkipianoОценок пока нет

- Implementing Evidence-Based Decisions in Clinical Practice: Elliot AbtДокумент7 страницImplementing Evidence-Based Decisions in Clinical Practice: Elliot AbtSri Hari100% (1)

- Herepes PDFДокумент8 страницHerepes PDFsuruthiОценок пока нет

- Ear MedicationДокумент15 страницEar MedicationPascalina Monts'onyaneОценок пока нет

- Jurnal InsomniaДокумент9 страницJurnal InsomniaMarie Obrien100% (1)

- Skenario C Blok 22Документ40 страницSkenario C Blok 22Ambhi GanaОценок пока нет

- What Is African Trypanosomiasis?Документ3 страницыWhat Is African Trypanosomiasis?dean016026Оценок пока нет

- Empagliflozin Metformin HCL: Jardiance Duo®Документ2 страницыEmpagliflozin Metformin HCL: Jardiance Duo®Lord Carlo CabangalОценок пока нет

- Reading Sample Test 1 Question Paper Part A PDFДокумент4 страницыReading Sample Test 1 Question Paper Part A PDFnavroop bajwaОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Ebn Managemen 1Документ7 страницJurnal Ebn Managemen 1KohakuОценок пока нет

- Nirali Final Synopsis PDFДокумент31 страницаNirali Final Synopsis PDFNIRALI MISTRYОценок пока нет

- Anaesthetic Considerations for Day Care SurgeryДокумент8 страницAnaesthetic Considerations for Day Care SurgerySirisha Ckv100% (1)

- Evmlu Uganda.2020Документ124 страницыEvmlu Uganda.2020ALINOMUGASHA EMMANUELОценок пока нет

- Heart Failure: Definition, Classification, Epidemiology & PathophysiologyДокумент10 страницHeart Failure: Definition, Classification, Epidemiology & PathophysiologyAlbert ShantoОценок пока нет

- Piis1470204520302722 PDFДокумент2 страницыPiis1470204520302722 PDFkayegi8666Оценок пока нет

- Gummin2018 PDFДокумент204 страницыGummin2018 PDFAelton AraujoОценок пока нет

- Nurs Fpx 4050 Assessment 1 Preliminary Care Coordination PlanДокумент4 страницыNurs Fpx 4050 Assessment 1 Preliminary Care Coordination Planfarwaamjad771Оценок пока нет

- HIV Drug ChartДокумент5 страницHIV Drug Chartalejandroo_26Оценок пока нет

- CONCEPT EpidemilologyДокумент13 страницCONCEPT EpidemilologyKrishnaveni MurugeshОценок пока нет

- Diabetes in Pregnancy: Management ofДокумент8 страницDiabetes in Pregnancy: Management ofdiana rossОценок пока нет

- Nursing Care Plan: Assessment Nursing Diagnosis Scientific Rationale Objectives Interventions Expected OutcomesДокумент2 страницыNursing Care Plan: Assessment Nursing Diagnosis Scientific Rationale Objectives Interventions Expected OutcomesAsdfghjlОценок пока нет

- BPHS - 2010 - Final - Master Signed - PDF LatestДокумент90 страницBPHS - 2010 - Final - Master Signed - PDF LatestZakia RafiqОценок пока нет

- Olimpiada Engleza 2017 CL A 8A PDFДокумент4 страницыOlimpiada Engleza 2017 CL A 8A PDFAnthony AdamsОценок пока нет