Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

High Prevalence of Potential Drug-Drug Interactions For Psoriasis Patients Prescribed Methotrexate or Cyclosporine For Psoriasis: Associated Clinical and Economic Outcomes in Real-World Practice

Загружено:

shaniОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

High Prevalence of Potential Drug-Drug Interactions For Psoriasis Patients Prescribed Methotrexate or Cyclosporine For Psoriasis: Associated Clinical and Economic Outcomes in Real-World Practice

Загружено:

shaniАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Original Paper

Dermatology 2010;220:128–137 Received: October 4, 2009

DOI: 10.1159/000275198 Accepted after revision: January 5, 2010

Published online: February 3, 2010

High Prevalence of Potential Drug-Drug

Interactions for Psoriasis Patients

Prescribed Methotrexate or Cyclosporine

for Psoriasis: Associated Clinical and

Economic Outcomes in Real-World Practice

a b b

Jean-Hilaire Saurat Annie Guérin Andrew P. Yu

b b

Dominick Latremouille-Viau Eric Q. Wu Shiraz R.

c c c

Gupta Yanjun Bao Parvez M. Mulani

b

aHôpital Cantonal Universitaire de Genève, Geneva, Switzerland; Analysis Group, Inc., Boston, Mass., and

c

Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Ill., USA

Key Words 0.0197) and pulmonary events (OR: 1.20; p = 0.0470), and

Methotrexate Cyclosporine Psoriasis Tumor sig-nificantly greater health care resource utilization (e.g. OR

necrosis factor Health care costs Drug interactions for inpatient and emergency department visits: 1.47; p !

0.0001) and costs (adjusted incremental cost: USD 1,722; p !

0.0001). Conclusions: MTX/CYC polypharmacy is prevalent

Abstract in pa-tients with psoriasis and associated with significant risks.

Background: Methotrexate (MTX) and cyclosporine (CYC) Copyright © 2010 S. Karger AG, Basel

may adversely interact with common medications in pa-tients

with psoriasis. Objective: Our purpose was to investi-gate the

prevalence and outcomes of MTX/CYC polyphar-macy. Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease

Methods: We evaluated rates of events that may be influ-enced by genetic and environmental characteristics

associated with drug-related toxicity, health care resource and worsened by factors such as stress, drugs, tobacco

utilization and costs for patients with psoriasis in the Inge-nix and alcohol abuse [1–3]. Psoriasis can impair physical

Impact National Managed Care Database (1999–2007) who and psychological well-being and decrease work

were exposed or not exposed to potential drug-drug productiv-ity [4].

interactions. Results: Among 4,583 (57.6%) exposed and Conventional oral systemic therapies, including meth-

3,372 (42.4%) nonexposed patients, nonsteroidal anti-in- otrexate (MTX), cyclosporine (CYC) and oral retinoids,

flammatory drugs and antibiotics were the most common are often used to treat patients with moderate to severe

drugs with potential interactions. The exposed patients had psoriasis who are not responsive to topical therapies alone.

significantly greater risks of developing renal [adjusted odds These systemic immunosuppressant medications have

ratio (OR): 2.58; p = 0.0145], gastrointestinal (OR: 1.36; p = risks for serious toxicities and adverse effects, in-

© 2010 S. Karger AG, Basel Jean-Hilaire Saurat, MD

Fax +41 61 306 12 34 1018–8665/10/2202–0128$26.00/0 Hôpital Cantonal Universitaire

Rue Micheli-du-Crest 24

E-Mail karger@karger.ch Accessible online at: CH–1211 Geneva (Switzerland)

www.karger.com www.karger.com/drm Tel. +41 22 372 94 22, Fax +41 22 372 94 60, E-Mail jean.saurat @ medecine.unige.ch

cluding renal toxicity, hepatotoxicity, hematotoxicity Study Population and Study Period

and gastrointestinal toxicity [5]. Thus, patients treated Patients were included in the study if they met the following

criteria: (1) at least 1 diagnosis of psoriasis [based on Internation-al

with oral systemic therapies need to be monitored

Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

regularly with laboratory tests of blood cell counts and (ICD-9-CM) 696.1x codes] [13], (2) continuous insurance for at

liver and renal function. Despite these toxicities, these least 6 months before and after the first prescription fill of an oral

inexpensive therapies, namely MTX and CYC, have conventional systemic therapy, including MTX or CYC (i.e. the

been the main-stay for treating moderate to severe index date and also the index medication), and (3) at least 18 years

of age 6 months prior to the index date. Patients with both MTX and

psoriasis for de-cades. CYC on the index date and no other interactions were ex-cluded

MTX and CYC may interact with a number of com- because MTX and CYC are known to interact with each other and

mon medications and this is of particular concern for this analysis focuses on drug-drug interactions associ-ated with

pa-tients with psoriasis because psoriasis is associated comorbidity-related drugs instead of relationships be-tween

with increased prevalence of several comorbidities [6– combinations of psoriasis therapies. However, the patients may have

initiated treatment on only MTX or CYC and later on used

10]. Concomitant use of these drugs to control chronic combination therapy sometime during the study period. The baseline

condi-tions or comorbidities could alter or prolong the period included 6 months prior to the index date, and the patients

blood concentrations of MTX/CYC and enhance their were followed for 6 months after the index date (i.e. the study

toxici-ties, which can cause adverse effects and period) for the outcomes evaluation.

compromise the treatment efficacy. Study Cohorts

Little is known about the clinical and economic rami- The study population was separated into 2 mutually exclusive

fications of these potential drug-drug interactions in the groups. A list of drugs that could potentially interact with MTX or

real-world setting [11, 12]. Other researchers have inves- CYC was first created using their respective product labels [6, 7].

tigated the topic of comedication due to comorbidities in All drugs that could potentially interact with MTX or CYC and lead

psoriasis patients and its interference with psoriasis treat- to an adverse event were included. However, drugs known to

decrease MTX or CYC concentration were not included. Patients

ments. However, to our knowledge, no studies on this who were taking any drug that could interact with MTX or CYC 30

topic have been conducted in a US psoriasis population of days before or 30 days after starting MTX or CYC were includ-ed in

all severities, and none have investigated the clinical and the exposed cohort. The nonexposed cohort included pa-tients

economic ramifications of comedication. Given the without any potential drug-drug interaction 30 days prior to the

seriousness of toxicities associated with systemic thera- index date and 6 months following the index date.

pies and potential intensification of these toxicities by Sensitivity Analysis

drug-drug interactions, this study used a large claims da- In a sensitivity analysis, the exposed cohort was restricted to

tabase to investigate the prevalence of real-world poly- a subgroup of patients with potential drug-drug interactions

pharmacy of oral conventional systemic therapies, in within 30 days before and after the index date. This subgroup

particular MTX and CYC, and drugs that may interact was intended to define potential drug-drug interactions with a

more stringent criterion by selecting patients who were taking a

with them. In addition, the rates of potential adverse poten-tially interactive drug and refilled their drug prescription

events were estimated, as well as the implications for even after the initiation of MTX or CYC.

health care resource utilization and costs associated with

potential drug-drug interactions among psoriasis pa-tients Statistical Analyses

with conventional systemic therapies, MTX or CYC, as a Patient Characteristics. Patient characteristics were reported

2

group. for both the exposed and the nonexposed cohorts. x tests were

performed for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum tests

were performed for continuous variables to test differences be-

tween the exposed and the nonexposed cohorts.

Methods Potential Adverse Events. The prevalence of relevant events that

may be associated with drug-related toxicities, including pul-

Data Source monary, renal, hematologic, gastrointestinal and hepatic events, were

The study used the Ingenix Impact National Managed Care identified using diagnosis codes from all medical claims (e.g.

Database from 1999 to 2007. This database includes the medical inpatient admissions, outpatient visits and emergency room visits)

and pharmacy history of 160 million patients from 46 health (online suppl. table 1, for all supplementary materials see

plans from all census regions of the USA and contains informa- www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000275198). Psoriasis patients with

tion on member eligibility, inpatient confinement, medical ser- any of these events at baseline were excluded. The study period was

vices utilization and pharmacy claims. truncated at the first occurrence of a relevant event. Odds ratios

(ORs) from logistic regressions were reported.

Health Care Resource Utilization. The utilization measures in-

cluded inpatient admissions, emergency department (ED) visits,

Drug-Drug Interactions in Patients with Dermatology 2010;220:128–137 129

Psoriasis

emergency care (inpatient and ED), outpatient visits and other

medical services (e.g. laboratory, radiology or other ancillary

ser-vices).

Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and ORs were estimated between Patients with psoriasis

cohorts using generalized linear model (GLM) regression n = 532,047

models with a log link function and negative binomial

distribution for IRRs and logistic regression models for ORs.

Health Care Costs. Health care costs were adjusted for inflation

Methotrexate or cyclosporine users

and expressed in USD 2007. The cost components included phar- n = 22,176

macy, inpatient, ED, outpatient and other medical service costs.

Incremental costs between the cohorts were reported using

GLM models with a log link and a g-distribution or 2-part mod-

els, where the first part is a logistic model with a binomial distri- Continuously eligible for at least 180 days prior to the index

bution and the second part is a GLM model with a log link and a date and 180 days after the index date n = 9,379

g-distribution, for cost components with a portion of 0 values

15%. The p values were estimated using a nonparametric boot-

strap resampling technique of 500 iterations.

Study events, health care resource utilization and cost were Age < 18 years 6 months prior to the index date

compared between the exposed and nonexposed cohorts during n = 9,226

the 6-month study period. In addition, appropriate multivariate

regression models controlled for age, sex, comorbidities with a

prevalence 12%, health care resource utilization and psoriasis a

treatment during the baseline period. Furthermore, ORs of po- Studied patients

n = 7,955

tential adverse events were also adjusted for the number of other

concomitant medications used during the 30 days before or 30

days after starting MTX or CYC. b, c c, d

Nonexposed cohort Exposed cohort

n = 3,372 n = 4,583

Results

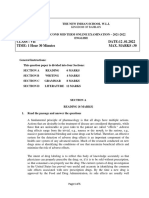

Sample Selection a

Fig. 1. Sample selection process and study population. Patients

Figure 1 shows the sample selection process. The study with drug-drug interactions between 30 days after the index date and

included 7,955 psoriasis patients who were taking either the end of the study period were included. The index date was

b

CYC or MTX; 3,372 patients (42.4%) comprised the non- defined as the first prescription fill of MTX or CYC. The non-

exposed cohort and 4,583 (57.6%) comprised the exposed exposed cohort included patients without drug-drug interactions 30

days prior to the index date or 6 months after the index date.

cohort. Among the exposed cohort, 3,629 patients (79.2%) cDrug-drug interactions were defined as a combination of MTX

initiated on MTX and 954 patients (20.8%) on CYC. or CYC with any of the following drugs: for MTX, nonsteroidal

The 2 study cohorts exhibited different anti-inflammatory drugs, trimethoprim, salicylates, phenylbuta-

zone, sulfonamides, penicillins, azathioprine, retinol, tretinoin,

characteristics at baseline (table 1). The patients in the isotretinoin, alitretinoin, etretinate, acitretin, tazarotene, bexaro-

exposed cohort were older (51.0 vs. 47.6 years; p ! tene, adapalene, theophylline, chloramphenicol, phenytoin, tet-

0.0001) and a greater percentage were women (56 vs. racycline or cyclosporine; for CYC, nonsteroidal anti-inflamma-

52%; p ! 0.0001). The prevalence of comorbidities was tory drugs, gentamicin, tobramycin, vancomycin, trimethoprim,

clarithromycin, erythromycin, quinupristin, melphalan, ampho-

generally greater in the exposed cohort and the 4 most tericin, ketoconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, diclofenac,

prevalent comorbidities were hypertension (30 vs. 16%; naproxen, sulindac, colchicine, cimetidine, ranitidine, tacrolim-

p ! 0.0001), psoriatic ar-thritis (35 vs. 14%; p ! 0.0001), us, diltiazem, nicardipine, verapamil, methylprednisolone, allo-

hyperlipidemia (26 vs.19%, p ! 0.0001) and rheumatoid purinol, bromocriptine, danazol, metoclopramide, amiodarone,

digoxin, lovastatin, methotrexate, HIV medications, potassium-

arthritis (24 vs.10%; p ! 0.0001). The patients in both d

sparing diuretics, prednisolone or rifabutin. The exposed cohort

cohorts had similar histo-ries of topical therapy use included patients with potential drug-drug interactions 30 days

during the baseline period, but more patients in the prior to the index date or 30 days after the index date.

exposed cohort used retinoids (15 vs. 7%; p ! 0.0001).

Among the drugs with potential interactions with MTX

or CYC, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

and antibiotics were the 2 most common drug classes pre-

scribed to patients who were taking MTX or CYC. The

130 Dermatology 2010;220:128–137 Saurat /Guérin /Yu /Latremouille-Viau /

Wu /Gupta /Bao /Mulani

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics for all studied patients prevalence for each of the studied potential drug-drug

(n = 7,955) in-teractions is shown in supplementary table 2.

Characteristics Exposed Nonexposed p valuea

Adverse Event Rates

Patients 4,583(57.6) 3,372(42.4) The rate of occurrence of relevant adverse events dur-

b

Mean age 8 SD, years 51.0812.1 47.6813.0 <0.0001 ing the study period was greater in the exposed than in the

Female sex 2,587(56.4) 1,749(51.9) <0.0001 nonexposed cohort (tables 2 and 3). Compared with the

c

Comorbidity nonexposed cohort, the exposed cohort initiating on CYC

AIDS 3(0.1) 3(0.1) 0.7059 had significantly greater rates of gastrointestinal events

Anemia 266 (5.8) 128 (3.8) <0.0001 (OR: 2.83; p ! 0.0001) and pulmonary events (OR: 1.62; p

Cerebrovascular 86(1.9) 52(1.5) 0.2590

Congestive heart failure 81(1.8) 21(0.6) <0.0001 = 0.0017). The renal event rates were also greater in the

Chronic pulmonary disease 421 (9.2) 195 (5.8) <0.0001 exposed cohort initiating on CYC than in the non-exposed

Coagulopathy 46(1.0) 26(0.8) 0.2789 cohort (OR: 2.39; p = 0.1186). Similarly, the ex-posed

Cardiovascular disease 314 (6.9) 146 (4.3) <0.0001 cohort initiating on MTX had significantly greater rates of

Depression 333 (7.3) 203 (6.0) 0.0285 renal events (OR: 4.33; p = 0.0061), hematologic events

Diabetes 540 (11.8) 225 (6.7) <0.0001

Fluid electrolyte disease 117 (2.6) 52(1.5) 0.0020 (OR: 1.56; p = 0.0014) and pulmonary events (OR: 1.43; p

Hyperlipidemia 1,171(25.6) 646 (19.2) <0.0001 = 0.0005) compared with the nonexposed cohort.

Hypertension 1,382(30.2) 528 (15.7) <0.0001 When looking at all the study patients together, the

Hypothyroidism 362 (7.9) 172 (5.1) <0.0001 most frequent events in the exposed and nonexposed co-

Liver disease 69(1.5) 27(0.8) 0.0044 horts were pulmonary (11 vs. 8%), hematologic (5 vs. 4%)

Lymphoma 30(0.7) 22(0.7) 0.9906

Metastatic cancer 14(0.3) 11 (0.3) 0.8703 and gastrointestinal events (5 vs. 3%). After adjusting for

Obesity 159 (3.5) 54(1.6) <0.0001 covariates at baseline, 3 types of adverse event remained

Other neurological disease 82(1.8) 35(1.0) 0.0059 significant. Renal events were more than twice as likely to

Paralysis 10(0.2) 4(0.1) 0.2951 occur in the exposed than in the nonexposed cohort (OR:

Peptic ulcer 22(0.5) 9(0.3) 0.1316 2.58; p = 0.0145). The likelihood of developing a gas-

Peripheral vascular disease 96(2.1) 40(1.2) 0.0020

Psoriatic arthritis 1,620(35.3) 460 (13.6) <0.0001

trointestinal event was 36% greater in the exposed cohort

Psychoses 181 (3.9) 94(2.8) 0.0051 than in the nonexposed cohort (OR: 1.36; p = 0.0197), and

Rheumatoid arthritis 1,105(24.1) 344 (10.2) <0.0001 the likelihood of developing a pulmonary event was 20%

Renal failure 56(1.2) 18(0.5) 0.0016 greater (OR: 1.20; p = 0.0470). The differences between

Solid tumor 197 (4.3) 128 (3.8) 0.2632 the cohorts for rates of hepatic and hematologic events

Valvular disease 149 (3.3) 57(1.7) <0.0001

were not statistically significant (table 3).

Weight loss 12(0.3) 2(0.1) 0.0332

d

History of psoriasis treatment Health Care Resource Utilization

Topical therapy 2,550(55.6) 1,890(56.0) 0.7163

Phototherapy 242 (5.3) 237 (7.0) 0.0012 Utilization of health care resources was significantly

e

Systemic nonbiologic therapy 705 (15.4) 237 (7.0) <0.0001 greater among the exposed than the nonexposed patients

Biologic therapy 312 (6.8) 287 (8.5) 0.0044 (table 4). After controlling for confounding factors, the

Prior use of potential inter- rates of inpatient and ED visits were 61 and 31%

f

action drugs , n (%) 3,724(81.3) 793 (23.5) <0.0001 greater, respectively, for the exposed cohort compared

with the nonexposed one (inpatient IRR: 1.61, p !

a

Figures in parentheses are percentages. p values were calculated

2

0.0001; ED IRR: 1.31, p ! 0.0022). The adjusted odds of

using x tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon tests for con- having an urgent care event during the study period

b

tinuous variables. Age was calculated 180 days prior to the index were also significant-ly greater among the exposed

c

date. Comorbidities were identified by International Classification

of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes defined by the US Agency for

patients (OR: 1.47; p ! 0.0001).

Healthcare Research and Quality [14] and were calculated during

the 6-month baseline period. Only comorbidities with a prevalence Health Care Costs

of at least 2% will be considered as covariates in the multivariate

d

regres-sion models. During the 6-month baseline period. The exposed cohort experienced significantly greater

e f

Excluding meth-otrexate and cyclosporine. Defined as any health care costs for all categories of medical service con-

prescription filled for the potential drugs that interact with the index sidered (table 5). During the 6-month study period, the

drug during the first 5 months of baseline period.

average total cost for pharmacy and medical services per

patient was 59% greater for the exposed cohort compared

Drug-Drug Interactions in Patients with Dermatology 2010;220:128–137 131

Psoriasis

Table 2. Potential adverse event rates stratified by CYC and MTX users

Exposed Nonexposed b

Unadjusted odds ratios

study patients with study patients with crude ratios p value

a adverse events a adverse events

sample sample

CYC users

Pulmonary event 791 98(12.4) 1,123 90 (8.0) 1.62 [1.20, 2.20] 0.0017

Renal event 920 9(1.0) 1,217 5 (0.4) 2.39 [0.80, 7.17] 0.1186

Hematologic event 843 40(4.7) 1,154 46 (4.0) 1.20 [0.78, 1.85] 0.4099

Gastrointestinal event 859 58(6.8) 1,164 29 (2.5) 2.83 [1.80, 4.47] <0.0001

Hepatic event 910 23(2.5) 1,196 21 (1.8) 1.45 [0.80, 2.64] 0.2225

MTX users

Pulmonary event 3,183 335 (10.5) 1,981 151 (7.6) 1.43 [1.17, 1.74] 0.0005

Renal event 3,599 29(0.8) 2,135 4 (0.2) 4.33 [1.52, 12.33] 0.0061

Hematologic event 3,385 188 (5.6) 2,041 74 (3.6) 1.56 [1.19, 2.06] 0.0014

Gastrointestinal event 3,435 148 (4.3) 2,081 71 (3.4) 1.27 [0.96, 1.70] 0.0990

Hepatic event 3,555 73(2.1) 2,121 41 (1.9) 1.06 [0.72, 1.57] 0.7545

Figures in parentheses are percentages and values in square brackets represent 95% confidence limits.

b

a All patients with the studied disease during the baseline period were excluded. Estimated using logistic regression without con-

trolling for baseline characteristics.

Table 3. Potential adverse event rates

Toxicity Exposed Nonexposed b c

Unadjusted ORs Adjusted ORs

study patients with study patients with crude ratios p value adjusted ratios p value

a adverse events a adverse events

sample sample

Pulmonary event 3,974 433 (10.9) 3,104 241 (7.8) 1.45 [1.23, 1.71] <0.0001 1.20 [1.00, 1.43] 0.0470

Renal event 4,519 38(0.8) 3,352 9 (0.3) 3.15 [1.52, 6.52] 0.0020 2.58 [1.21, 5.52] 0.0145

Hematologic event 4,228 228 (5.4) 3,195 120 (3.8) 1.46 [1.17, 1.83] 0.0010 1.15 [0.90, 1.46] 0.2656

Gastrointestinal event 4,294 206 (4.8) 3,245 100 (3.1) 1.58 [1.24, 2.02] 0.0002 1.36 [1.05, 1.77] 0.0197

Hepatic event 4,465 96(2.2) 3,317 62 (1.9) 1.15 [0.84, 1.59] 0.3853 1.09 [0.77, 1.55] 0.6239

Figures in parentheses are percentages and values in square medications, baseline comorbidities and baseline psoriasis treat-

brackets represent 95% confidence limits. ments. Psoriasis treatments included topical therapy, biologic

a

All patients with the studied adverse event during the base- therapy, systemic nonbiologic therapy and phototherapy.

line period were excluded. Baseline comorbidities were: cardiovascular disease,

b

Estimated using logistic regression without controlling for hypothyroidism, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, valvular

baseline characteristics. disease, depres-sion, fluid electrolyte disorders, hyperlipidemia,

c

Adjusted ratios were estimated using multivariate regression obesity, psycho-ses and solid tumor.

models controlling for age, gender, number of other concomitant

with the nonexposed cohort (USD 7,960 vs. 5,021, p ! Sensitivity Analysis

0.0001). The adjusted incremental total costs for the ex- The sensitivity analysis included a subgroup of 2,704

posed cohort were USD 1,722, 28% greater compared patients in the exposed cohort who refilled their prescrip-

with the nonexposed cohort’s total costs (p ! 0.0001). The tions for potentially interactive drugs after the initiation of

adjusted incremental pharmacy (USD 711, p ! 0.0001) and MTX or CYC. Compared with the nonexposed cohort, this

outpatient costs (USD 539, p ! 0.0001) comprised a subgroup had an almost 3-fold greater risk of devel-oping

substantial portion of the total cost differential. a renal event (OR: 2.82; p = 0.0138) and a 38% great-

132 Dermatology 2010;220:128–137 Saurat /Guérin /Yu /Latremouille-Viau /

Wu /Gupta /Bao /Mulani

Table 4. Health care resource utilization

Medical outcome a Unadjusted b

Outcomes Adjusted

exposed nonexposed crude rate ratios p value adjusted rate p value

(n = 4,593) (n = 3,362) ratios

Inpatient

c

IRR 574 184 2.30 (1.86, 2.84) <0.0001 1.61 (1.30, 1.99) <0.0001

d

OR 375 144 2.00 (1.64, 2.43) <0.0001 1.55 (1.25, 1.93) <0.0001

ED

c

IRR 1,094 512 1.57 (1.32, 1.87) <0.0001 1.31 (1.10, 1.56) 0.0022

d

OR 574 288 1.53 (1.32, 1.78) <0.0001 1.39 (1.18, 1.64) <0.0001

Emergency care (inpatient and ED)

c

IRR 1,668 696 1.76 (1.53, 2.04) <0.0001 1.40 (1.21, 1.62) <0.0001

d

OR 825 385 1.70 (1.50, 1.94) <0.0001 1.47 (1.28, 1.70) <0.0001

Outpatient

c

IRR 52,860 29,296 1.41 (1.32, 1.52) <0.0001 1.22 (1.13, 1.32) <0.0001

e

Other medical services

c 10,780 5,613 1.33 (1.28, 1.37) <0.0001 1.16 (1.13, 1.20) <0.0001

IRR

Figures in parentheses are 95% confidence limits. pothyroidism, psoriatic arthritis, anemia, rheumatoid arthritis,

a

Total number of patients for OR and total number of visits valvular disease, depression, fluid electrolyte disorders, hyperlip-

for IRR. idemia, obesity, psychoses and solid tumor.

b c

Adjusted ratios were estimated using multivariate regression IRR refers the number of visits/hospitalizations during the

models controlling for age, gender, baseline comorbidities, base-line study period.

d

health care utilization and baseline psoriasis treatments, in-cluding OR refers to the probability of having at least 1 visit/hospi-

topical therapy, biologic therapy, systemic nonbiologic therapy and talization during the study period.

e

phototherapy. Baseline comorbidities were cardio-vascular disease, Including laboratory, radiology or other ancillary services.

chronic pulmonary disease, hypertension, hy-

Table 5. Health care costs

a Unadjusted cost difference b

Costs Adjusted cost difference

exposed nonexposed incremental p value incremental p value

costs costs

Pharmacy 2,89683,274 2,15383,028 743 <0.0001 711 <0.0001

Medical services

Emergency care (inpatient and ED) 1,661812,108 70584,962 956 <0.0001 105 0.5030

Outpatient 2,95486,156 1,92084,262 1,034 <0.0001 539 <0.0001

Other medical services 44882,092 24381,145 205 <0.0001 103 0.0040

Total (pharmacy + medical services) 7,960816,038 5,02187,820 2,938 <0.0001 1,722 <0.0001

aValues are means 8 standard deviation in 2007 USD. ism, psoriatic arthritis, anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, valvular

b Adjusted costs were estimated using multivariate regression disease, depression, fluid electrolyte disorders, hyperlipidemia,

models controlling for age, sex, baseline comorbidities, baseline

health care utilization and baseline psoriasis treatments, includ- obesity, psychoses and solid tumor. Cost differences were esti-

ing topical therapy, biologic therapy, systemic nonbiologic thera- mates using 2-part models for cost components with >5% of pa-

py and phototherapy. Baseline comorbidities were cardiovascular tients having 0 costs (e.g. inpatient, ED), and GLM regression

disease, chronic pulmonary disease, hypertension, hypothyroid- models with a log-link and a g-distribution were used for the

oth-er cost components (e.g. outpatient, total).

Drug-Drug Interactions in Patients with Dermatology 2010;220:128–137 133

Psoriasis

Table 6. Sensitivity analysis of adverse event rates

Toxicity Exposed Nonexposed b c

Unadjusted ORs Adjusted ORs

study patients with study patients with crude ratios p value adjusted ratios p value

a adverse event a

sample sample adverse event

Pulmonary event 2,340 269 (11.5) 3,104 241 (7.8) 1.54 [1.29, 1.85] <0.0001 1.16 [0.94, 1.43] 0.1557

Renal event 2,653 26(1.0) 3,352 9 (0.3) 3.68 [1.72, 7.86] 0.0008 2.82 [1.24, 6.44] 0.0138

Hematologic event 2,467 137 (5.6) 3,195 120 (3.8) 1.51 [1.17, 1.94] 0.0014 1.12 [0.84, 1.48] 0.4346

Gastrointestinal event 2,522 124 (4.9) 3,245 100 (3.1) 1.63 [1.24, 2.13] 0.0004 1.38 [1.02, 1.86] 0.0377

Hepatic event 2,629 59(2.2) 3,317 62 (1.9) 1.21 [0.84, 1.73] 0.3097 1.11 [0.74, 1.68] 0.6135

Figures in parentheses are percentages and values in square medications, baseline comorbidities and baseline psoriasis treat-

brackets represent 95% confidence limits. ments. Psoriasis treatments included topical therapy, biologic

a

All patients with the studied adverse event during the base- therapy, systemic nonbiologic therapy and phototherapy.

line period were excluded. Baseline comorbidities were: cardiovascular disease,

b

Estimated using logistic regression without controlling for hypothyroidism, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, valvular

baseline characteristics. disease, depres-sion, fluid electrolyte disorders, hyperlipidemia,

c

Adjusted ratios were estimated using multivariate regression obesity, psycho-ses and solid tumor.

models controlling for age, sex, number of other concomitant

er likelihood of developing a gastrointestinal event (OR: The results demonstrated that more than half of the

1.38; p = 0.0377; table 6). patients treated with MTX or CYC also received prescrip-

The sensitivity analysis also demonstrated greater to- tions for interacting drugs at the time of MTX/CYC ini-

tal incremental health care costs for the exposed cohort tiation. Compared with the patients who were not taking

compared with the nonexposed cohort (table 7). The ad- interacting drugs, these patients experienced significant-ly

justed incremental total costs were USD 1,905 greater greater risks of pulmonary, renal and gastrointestinal

per person over a 6-month period in the exposed than in events and incurred substantially greater costs for re-

the nonexposed cohort (p ! 0.0001). This value source utilization and treatment. A sensitivity analysis that

represents USD 400 more per year than the original used more stringent inclusion criteria for selecting exposed

analysis, in which the total incremental costs for the patients was confirmatory, with results that were robust

exposed cohort were USD 1,722 (p ! 0.0001). and more pronounced than for the initial exposed cohort,

especially for renal events.

Even at recommended dosages of MTX or CYC, there

Discussion is a risk of renal or gastrointestinal toxicity when MTX or

CYC are coadministered with compounds that increase

This study investigated the prevalence of potential their blood concentration and/or decrease their clearance

drug-drug interactions between the conventional system-ic [15, 16]. In this study, the exposed patients experienced

therapies, MTX and CYC, and various drugs typically greater risks of these particular adverse events, consistent

taken by patients with psoriasis. In addition, we evaluated with the known clinical consequences of those drug-drug

the outcomes of potential drug-drug interactions, such as interactions. Furthermore, coadministration of drugs that

adverse events, healthcare resource utilization and costs, may interact with MTX or CYC and that could be deemed

by comparing the patients exposed to drug-drug interac- high-risk interactions, based on information available in

tions with those who were not exposed. The study did not the product labels [6, 7], was relatively frequent.

aim to determine which immunosuppressant was better in The most commonly used drugs with potential to in-

terms of safety or tolerability. The study looked at all teract with both MTX and CYC in the exposed cohort

events that may be caused by toxicities related to these 2 were NSAIDs and sulfonamides. NSAIDs are often used

oral conventional systemic therapies. These analyses were to treat acute or chronic pain and inflammatory condi-

performed using a large, US managed-care database that tions, such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis.

included, but was not limited to, patients with psoriasis. The interaction of NSAIDs with MTX elevates and the

134 Dermatology 2010;220:128–137 Saurat /Guérin /Yu /Latremouille-Viau /

Wu /Gupta /Bao /Mulani

Table 7. Sensitivity analysis of health care costs

a Unadjusted cost difference b

Costs Adjusted cost difference

exposed nonexposed incremental p value incremental p value

costs costs

Pharmacy 3,20283,309 2,15383,028 1,048 <0.0001 1,087 <0.0001

Medical services

Emergency care (inpatient and ED) 1,63988,379 70584,962 933 <0.0001 18 0.9022

Outpatient 3,01085,279 1,92084,262 1,090 <0.0001 430 <0.0001

Other medical services 44182,051 24381,145 197 <0.0001 105 <0.0001

Total (pharmacy + medical services) 8,291812,454 5,02187,820 3,269 <0.0001 1,905 <0.0001

aValues are means 8 standard deviation in 2007 USD. ism, psoriatic arthritis, anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, valvular

b Adjusted costs were estimated using multivariate regression disease, depression, fluid electrolyte disorders, hyperlipidemia,

models controlling for age, sex, baseline comorbidities, baseline

health care utilization, and baseline psoriasis treatments, includ- obesity, psychoses and solid tumor. Cost differences were esti-

ing topical therapy, biologic therapy, systemic nonbiologic thera- mates using 2-part models for cost components with >5% of the

py and phototherapy. Baseline comorbidities were cardiovascular patients having 0 costs (e.g. inpatient, ED), and GLM regression

disease, chronic pulmonary disease, hypertension, hypothyroid- models with a log-link and a g-distribution were used for the

oth-er cost components (e.g. outpatient, total).

prolongs serum concentrations of MTX and increases the more extensive comorbidity profiles compared with the

risk of aplastic anemia, bone marrow suppression and nonexposed cohort. To control for selection bias, we

gastrointestinal toxicity [6, 17]. Concomitant administra- also controlled for baseline healthcare resource

tion of CYC and NSAIDs can be associated with a more utilization (inpatient, ED, outpatient), a comprehensive

pronounced decrease in renal function than that seen with list of co-morbidities and history of psoriasis treatments

either agent alone and is linked to renal toxicity [7, 18]. prior to initiation of MTX/CYC systemic therapy.

When taken alone, NSAIDs may lead to renal or gas- Because of the risk of toxicities with conventional

trointestinal effects, particularly in patients with pre-ex- sys-temic therapies, their use requires comprehensive

isting chronic renal disease or with decreased effective and regular laboratory monitoring, which can increase

circulating fluid volume [19–21]. Most guidelines for pso- the total costs [29, 30]. A lack of efficacy with these

riasis treatment do not recommend nonbiologic systemic immuno-suppressant agents may lead to dose titration

therapies, especially high doses of MTX, for patients who or use of combination therapies [31, 32]. Poor response

are already at risk of renal and gastrointestinal toxicity and issues related to drug safety and tolerability may

events or who have uncontrolled hypertension [6, 8, 22]. result in either worsening of the disease or an adverse

Sulfonamides are also frequently used to treat patients effect and poten-tial hospitalization.

with psoriasis and can potentially interact with MTX or Although claims data are a rich source for examining

CYC. Sulfonamides are synthetic antimicrobial agents and health care utilization and costs, there are some inherent

are also applied in the treatment of inflammatory bowel limitations in any study conducted with claims data. This

disease. Sulfonamides can diminish renal tubular transport investigation is based on administrative claims data in

of MTX, thus increasing MTX concentrations and the risk which patients’ psoriasis severity, adverse event severity

of toxicities, including renal toxicity, hepato-toxicity and and comorbidities could not be directly observed. There-

bone marrow suppression [23–25]. Penicillin is often used fore, despite the comprehensive list of covariates used in

as treatment for guttate psoriasis, which is usually a the study, selection bias may still remain. In addition,

streptococcal (bacterial) infection that may be responsible pharmacy claims data do not provide information on

for chronic plaque psoriasis [26–28]. whether drugs dispensed were actually taken according to

The patients in the exposed cohort experienced sig- prescribed instructions. Thus, the study determined

nificantly greater health care costs than those in the non- potential drug-drug interactions under the assumption that

exposed cohort. The baseline characteristics showed that patients took their medicine as prescribed. This lim-itation

the exposed patients had greater prior resource use and was overcome to a certain extent in the sensitivity

Drug-Drug Interactions in Patients with Dermatology 2010;220:128–137 135

Psoriasis

analysis, in which stricter criteria were used. Another Previous studies have shown that patients with psoria-

drawback is that the study was limited to prescribed sis have an increased prevalence of multiple comorbidi-

med-ication and did not considerer over-the-counter ties [9, 10]. This study found that, overall, 50% of the pa-

products that could also be associated with drug-drug tients treated with conventional oral systemic therapies

interac-tions; thus, the findings may have (MTX or CYC) may experience potential drug-drug in-

underestimated the impact of drug-drug interactions. teractions due to comedication with interacting drugs. The

In addition, with claims data, it is not possible to be total impact of these interactions (increased toxicity risk,

certain that an adverse event is related to a drug-drug in- healthcare resource use and overall costs) is substan-tial.

teraction. The adverse event rates reported in this study Caution should be exercised when prescribing con-

were based on the emergence of specific ICD-9 diagnosis ventional systemic therapies to patients with psoriasis be-

codes in patients’ medical claims that were used in the cause of the likelihood and potential effects of interac-

definition of potential drug-related toxicities. These rates tions with concurrent medication use. Both the drug and

represent all patients who experienced the studied toxic-ity the patient’s unique characteristics need to be considered

during the follow-up period in the case and control when making treatment decisions to promote optimal

cohorts. Patients with the studied conditions at baseline outcomes, even if that means selecting more costly thera-

were excluded from the analysis. Based on the temporal pies. As has been previously demonstrated, certain agents

relationship between concomitant drug use and the emer- may have safer treatment profiles and promote better ad-

gence of these ICD-9 codes, one could infer that at least herence that ultimately offset a psoriasis patient’s total cost

some of the diagnoses were due to drug interactions. of care [33].

However, the conditions identified by the ICD-9 diagno-

sis codes may not have solely resulted from drug use. For

example, conditions may have developed irrespective of a Acknowledgment

drug interaction with MTX or CYC because of patients’

The authors thank Arbor Communications, Inc., Ann Arbor,

lifestyle factors (e.g. tobacco use), environmental factors Mich., USA, for editorial assistance on behalf of Abbott Labora-

or family histories; information about such factors was not tories. This analysis was supported by Abbott Laboratories.

available in the claims data.

To minimize the impact of factors that could not be

controlled for in our analysis of claims data, the same Disclosures

definition of toxicity was applied to both cohorts. The

results, therefore, show that in a relative sense, exposed J.-H.S. has served as a consultant for Abbott Laboratories and

has participated in continuing medical education events support-

patients were more likely to experience a studied ed by unrestricted educational grants from Abbott Laboratories.

toxicity than nonexposed patients. The study findings The work reported here was performed under contract for Ab-

are based on relative risks. Events that were not directly bott Laboratories by Analysis Group. A.P.Y. and E.Q.W., A.G.

related to drug toxicities should have been as frequent and D.L.-V. are employees of Analysis Group. S.R.G., Y.B. and

in both co-horts and, therefore, would not have had an P.M.M. are employees of Abbott Laboratories.

impact on the relative risk.

References

1 Morse RM, Perry HO, Hurt RD: psoriasis: results from an Italian case-control tion. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/Scripts/

Alcoholism and psoriasis. Alcohol Clin study. J Invest Dermatol 2005; 125: 61–67. cder/DrugsatFDA/index.cfm (accessed March

Exp Res 1985; 9: 396–399. 4 Schmitt JM, Ford DE: Work limitations and 27, 2009).

2 Swanbeck G, Inerot A, Martinsson T, Wahl- productivity loss are associated with 7 US Food and Drug Administration: Cyclo-sporine

ström J: A population genetic study of pso- health-related quality of life but not with oral solution and soft capsules.

riasis. Br J Dermatol 1994; 131: 32–39. clinical se-verity in patients with psoriasis. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/Scripts/cder/

Dermatol-ogy 2006; 213: 102–110. DrugsatFDA/index.cfm (accessed March 27,

3 Naldi L, Chatenoud L, Linder D, Belloni

5 McClure SL, Valentine J, Gordon KB: 2009).

Forti-na A, Peserico A, Virgili AR, Bruni

Com-parative tolerability of systemic 8 Mrowietz U, Elder JT, Barker J: The impor-

PL, Ingordo V, Lo Scocco G, Solaroli C,

treatments for plaque-type psoriasis. Drug tance of disease associations and concomi-

Schena D, Barba A, Di Landro A,

Saf 2002; 25: 913–927. tant therapy for the long-term management

Pezzarossa E, Arcangeli F, Gianni C, Betti

6 US Food and Drug Administration: Metho- of psoriasis patients. Arch Dermatol Res

R, Carli P, Farris A, Barabino GF, La

trexate sodium tablet and solution for injec- 2006; 298: 309–319.

Vecchia C: Cigarette smoking, body mass

in-dex, and stressful life events as risk

factors for

136 Dermatology 2010;220:128–137 Saurat /Guérin /Yu /Latremouille-Viau /

Wu /Gupta /Bao /Mulani

9 Cohen AD, Sherf M, Vidavsky L, Vardy DA, 17 Casserly CM, Stange KC, Chren MM: Severe 26 Caca-Biljanovska NG, V’lckova-Laskoska

Shapiro J, Meyerovitch J: Association be-tween megaloblastic anemia in a patient receiving low- MT: Management of guttate and

psoriasis and the metabolic syndrome: dose methotrexate for psoriasis. J Am Acad generalized psoriasis vulgaris: prospective

a cross-sectional study. Dermatology 2008; Dermatol 1993; 29: 477–480. randomized study. Croat Med J 2002; 43:

216: 152–155. 18 National Psoriasis Foundation: Cyclospo- 707–712.

10 Gottlieb AB, Chao C, Dann F: Psoriasis co- rine. http://www.psoriasis.org/treatment/ 27 Dogan B, Karabudak O, Harmanyeri Y: An-

morbidities. J Dermatol Treat 2008; 19: 5–21. psoriasis/systemics/cyclosporine.php (ac- tistreptococcal treatment of guttate psoria-

11 Gerdes S, Zahl VA, Knopf H, Weichenthal cessed March 27, 2009). sis: a controlled study. Int J Dermatol 2008;

M, Mrowietz U: Comedication related to 19 Aronoff GR: Nonsteroidal anti-inflamma- 47: 950–952.

co-morbidities: a study in 1203 tory drug induced renal syndromes. J Ky 28 Saxena VN, Dogra J: Long-term use of

hospitalized pa-tients with severe psoriasis. Med Assoc 1992; 90: 336–339. peni-cillin for the treatment of chronic

Br J Dermatol 2008; 159: 1116–1123. 20 Laine L: Approaches to nonsteroidal anti- plaque psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol 2005; 15:

12 Yosipovitch G, Tang MB: Practical in-flammatory drug use in the high-risk pa- 359–362.

manage-ment of psoriasis in the elderly: tient. Gastroenterology 2001; 120: 594– 29 Sander HM, Morris LF, Phillips CM, Harri-

epidemiolo-gy, clinical aspects, quality of 606. son PE, Menter A: The annual cost of

life, patient education and treatment 21 Gooch K, Culleton BF, Manns BJ, Zhang J, psoria-sis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 28:

options. Drugs Ag-ing 2002; 19: 847–863. Alfonso H, Tonelli M, et al: NSAID use 422–425.

13 US Department of Health and Human Ser- and progression of chronic kidney disease. 30 Crown WH, Bresnahan BW, Orsini LS,

vices: International Classification of Am J Med 2007; 120: 280.e1–280.e7. Ken-nedy S, Leonardi C: The burden of

Diseas-es, Ninth Revision, Clinical 22 Recommendations for the medical manage-ment illness as-sociated with psoriasis: cost of

Modification, ed 4. Washington, US of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 treatment with systemic therapy and

Government Printing Office, 1991. update. American College of Rheuma-tology phototherapy in the US. Curr Med Res

14 Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Kruzikas D: Co- Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines. Opin 2004; 20: 1929– 1936.

morbidity software. HCUP Methods Series Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43: 1905–

Report No 2004-1. US Agency for Healthcare 31 Khachemoune A, Phillips TJ: Current treat-

1915.

Research and Quality. 2004. http://www. hcup- ment options in psoriasis. Hosp Pract (Min-

23 Thomas DR, Dover JS, Camp RD:

us.ahrq.gov/reports/Comorbidi- neap) 2000; 35: 93–96, 101–104, 107.

Pancyto-penia induced by the interaction

tySoftwareDocumentationFinal.pdf (ac-cessed 32 Jeffes EW 3rd, Weinstein GD:

between methotrexate and trimethoprim-

March 27, 2009). Methotrexate and other chemotherapeutic

sulfa-methoxazole. J Am Acad Dermatol

15 Daly HM, Scott GL, Boyle J, Roberts CJ: agents used to treat psoriasis. Dermatol

1987; 17: 1055–1056.

Methotrexate toxicity precipitated by aza- Clin 1995; 13: 875– 890.

24 Abel EA, Farber EM: Pancytopenia follow-

propazone. Br J Dermatol 1986; 114: 733– 33 Bhosle MJ, Feldman SR, Camacho FT,

ing low-dose methotrexate therapy. JAMA

735. Timo-thy Whitmire J, Nahata MC,

1988; 259: 3612.

16 Larsen FG, Nielsen-Kudsk F, Jakobsen P, Balkrishnan R: Medication adherence and

25 Elkayam O, Yaron M, Zhukovsky G, Segal

Schrøder H, Kragballe K: Interaction of health care costs associated with biologics

R, Caspi D: Toxicity profile of dual

etretinate with methotrexate pharmacoki- in Medicaid-en-rolled patients with

methotrex-ate combinations with gold,

netics in psoriatic patients. J Clin psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat 2006; 17: 294–

hydroxychloro-quine, sulphasalazine and

Pharmacol 1990; 30: 802–807. 301.

minocycline in rheumatoid arthritis

patients. Rheumatol Int 1997; 17: 49–53.

Drug-Drug Interactions in Patients with Dermatology 2010;220:128–137 137

Psoriasis

Вам также может понравиться

- 1 KolomДокумент27 страниц1 KolomShania Astanti SimanjuntakОценок пока нет

- Treatment and Referral Patterns For Psoriasis in United Kingdom Primary Care: A Retrospective Cohort StudyДокумент7 страницTreatment and Referral Patterns For Psoriasis in United Kingdom Primary Care: A Retrospective Cohort StudyYaumul RobbiОценок пока нет

- 16859604Документ8 страниц16859604Brent DoolanОценок пока нет

- Serious Infections in ANCA-associated Vasculitides in The Biologic Era Real Life Data From A Multicenter Cohort of 162 PatientsДокумент9 страницSerious Infections in ANCA-associated Vasculitides in The Biologic Era Real Life Data From A Multicenter Cohort of 162 PatientsManuel ArenasОценок пока нет

- Lefamulin SSTIДокумент11 страницLefamulin SSTIashikОценок пока нет

- Effect of Procalcitonin-Guided AntibioticДокумент11 страницEffect of Procalcitonin-Guided AntibioticRaul ContrerasОценок пока нет

- Cer 2021 0311Документ8 страницCer 2021 0311marcotkОценок пока нет

- Procalcitonin and AB DecisionsДокумент10 страницProcalcitonin and AB DecisionsDennysson CorreiaОценок пока нет

- Diacerein For The Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis in Patients With Inadequate Response To Methotrexate A Pilot Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Add-On Trial - TEM HTMLДокумент11 страницDiacerein For The Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis in Patients With Inadequate Response To Methotrexate A Pilot Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Add-On Trial - TEM HTMLAline Leal CortesОценок пока нет

- s13054 023 04626 ZДокумент8 страницs13054 023 04626 ZDipendra PoudelОценок пока нет

- Data Science Enabling Personalized MedicineДокумент15 страницData Science Enabling Personalized MedicineAditya DebnathОценок пока нет

- Drug Utilisation Study of UTIДокумент4 страницыDrug Utilisation Study of UTIviva.anu24Оценок пока нет

- Vandergarde Thorax2006Документ5 страницVandergarde Thorax2006Oneng IfayaniОценок пока нет

- Childhood Psoriasis Methotrexate TreatmentДокумент5 страницChildhood Psoriasis Methotrexate TreatmentNana AdistyОценок пока нет

- Stroids Meta 2023Документ14 страницStroids Meta 2023Sachin KumarОценок пока нет

- Guidelines For Prevention of NSAID-Related Ulcer ComplicationsДокумент11 страницGuidelines For Prevention of NSAID-Related Ulcer ComplicationsPeet UpОценок пока нет

- Safety and Efficacy of CorticosteroidsДокумент9 страницSafety and Efficacy of CorticosteroidsMatt CoghlanОценок пока нет

- Antidepresive - Reactii Adverse (20-64 Ani)Документ24 страницыAntidepresive - Reactii Adverse (20-64 Ani)Robert MovileanuОценок пока нет

- Clinical Decision Support Systems Great Promises For Better Management of Patients Drug TherapyДокумент4 страницыClinical Decision Support Systems Great Promises For Better Management of Patients Drug TherapyTrang Hoàng ThịОценок пока нет

- Pediatric Blood Cancer - 2017 - Balk - Drug Drug Interactions in Pediatric Oncology Patients PDFДокумент7 страницPediatric Blood Cancer - 2017 - Balk - Drug Drug Interactions in Pediatric Oncology Patients PDFCatalina Del CantoОценок пока нет

- Increased Risk of Microscopic Colitis With Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors and Non-Steroidal Anti-In Ammatory DrugsДокумент11 страницIncreased Risk of Microscopic Colitis With Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors and Non-Steroidal Anti-In Ammatory DrugsFabrizzio BardalesОценок пока нет

- Articulo NeumoniaДокумент7 страницArticulo NeumoniaEd BarajasОценок пока нет

- Ar 3453Документ14 страницAr 3453Pulmonologi Dan Kedokteran Respirasi FK UNRIОценок пока нет

- Adverse Drug Reactions and Outcome Analysis of MDR TB Patients On Dots Plus RegimenДокумент5 страницAdverse Drug Reactions and Outcome Analysis of MDR TB Patients On Dots Plus RegimenkopaljsОценок пока нет

- 2014 Lee (TOFA Vs MTX)Документ10 страниц2014 Lee (TOFA Vs MTX)Marcel JinihОценок пока нет

- Strokeaha 109 576413Документ13 страницStrokeaha 109 576413ichaОценок пока нет

- Methotrexate Reduces The Occurrence of Cerebrovascular Events Among Taiwanese Psoriatic Patients: A Nationwide Population-Based StudyДокумент4 страницыMethotrexate Reduces The Occurrence of Cerebrovascular Events Among Taiwanese Psoriatic Patients: A Nationwide Population-Based StudyHermayudiОценок пока нет

- Improving Medication Safety: Development and Impact of A Multivariate Model-Based Strategy To Target High-Risk PatientsДокумент13 страницImproving Medication Safety: Development and Impact of A Multivariate Model-Based Strategy To Target High-Risk PatientstotoksaptantoОценок пока нет

- The Limitations of Observation StudiesДокумент5 страницThe Limitations of Observation StudiesalbgomezОценок пока нет

- Clinical Characterization Cohort Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. PLoS One-2023Документ14 страницClinical Characterization Cohort Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. PLoS One-2023Jorge Ricardo Parra CamachoОценок пока нет

- Eraker 1984Документ11 страницEraker 1984Lorena PăduraruОценок пока нет

- Chemotherapy and Biotherapeutic Agents For Autoimmune DiseasesДокумент17 страницChemotherapy and Biotherapeutic Agents For Autoimmune DiseasesIriani Dewi SetiawanОценок пока нет

- Alok A. Khorana - Incidence and Predictors of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) Among Ambulatory High-RiskДокумент8 страницAlok A. Khorana - Incidence and Predictors of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) Among Ambulatory High-RiskFarid RakhmanОценок пока нет

- Steroids in Chronic Subdural Hematomas SUCRE TrialДокумент8 страницSteroids in Chronic Subdural Hematomas SUCRE TrialEdward Arthur IskandarОценок пока нет

- Antibiotico en SepsisДокумент15 страницAntibiotico en SepsisJuan RodriguezОценок пока нет

- ProkalsitoninДокумент11 страницProkalsitoninFarmasi RSUD Kramat JatiОценок пока нет

- Topical Antibiotics To Prevent Surgical Site Infection After Minor Surgery in Primary CareДокумент5 страницTopical Antibiotics To Prevent Surgical Site Infection After Minor Surgery in Primary CarePitchya WangmeesriОценок пока нет

- Efek Samping Obat TBДокумент12 страницEfek Samping Obat TBLeonita L. ArdiatiОценок пока нет

- Cancer ResistenДокумент38 страницCancer ResistenArief RafsanjaniОценок пока нет

- Yiu Et Al 2016 Risk of Serious Infections in Patients With Psoriasis On Biologic Therapis Metas-AnalysisДокумент8 страницYiu Et Al 2016 Risk of Serious Infections in Patients With Psoriasis On Biologic Therapis Metas-AnalysisMarcel JinihОценок пока нет

- WSC Abstracts - 2011Документ667 страницWSC Abstracts - 2011cyber_zac52Оценок пока нет

- B2a04034Документ7 страницB2a04034kaira musahariОценок пока нет

- ASHP Technical Assistance Bulletin On Handling Cytotoxic and Hazardous DrugsДокумент16 страницASHP Technical Assistance Bulletin On Handling Cytotoxic and Hazardous DrugsAmy YuenОценок пока нет

- Nihms 1510131Документ59 страницNihms 1510131ikokalariОценок пока нет

- Fvalin,+06 CBR 42.4 OA 120920Документ8 страницFvalin,+06 CBR 42.4 OA 120920Dani PurgananОценок пока нет

- Precision Medicine For RheumatologistsДокумент9 страницPrecision Medicine For Rheumatologistsmihaelaatanasova123Оценок пока нет

- Arthritis Care Research - 2022 - Dalbeth - Predictors of Patient and Physician Assessments of Gout ControlДокумент5 страницArthritis Care Research - 2022 - Dalbeth - Predictors of Patient and Physician Assessments of Gout ControlawaloeiacidОценок пока нет

- IVUДокумент6 страницIVUPaullette SanjuanОценок пока нет

- Treatment of Hospital-Acquired, Ventilator-Associated, and Healthcare-Associated Pneumonia in AdultsДокумент19 страницTreatment of Hospital-Acquired, Ventilator-Associated, and Healthcare-Associated Pneumonia in Adultsmd.dascalescu2486Оценок пока нет

- Cp-Acpj210021 737..747Документ11 страницCp-Acpj210021 737..747Luis Genaro Garcia AyalaОценок пока нет

- Adherence To Oral Hypoglycemic MedicatioДокумент20 страницAdherence To Oral Hypoglycemic Medicatioashenafi woldesenbetОценок пока нет

- Ciz 1197Документ8 страницCiz 1197Lindia PrabhaswariОценок пока нет

- Lam 2018Документ7 страницLam 2018adrifen adriОценок пока нет

- Traa 144Документ9 страницTraa 144RashifОценок пока нет

- PMC7127809Документ19 страницPMC7127809Vishesh GoyalОценок пока нет

- Effect of Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy On Hba1C Values in Chronic Periodontitis Patient With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic ReviewДокумент6 страницEffect of Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy On Hba1C Values in Chronic Periodontitis Patient With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic ReviewsutrisnoОценок пока нет

- Alqenae 2020 - Prevalencia de Los Errores de MedicacionДокумент21 страницаAlqenae 2020 - Prevalencia de Los Errores de MedicacionJuan camiloОценок пока нет

- The British Journal of DermatologyДокумент7 страницThe British Journal of DermatologyhanumzniiОценок пока нет

- Corticosteroids in The Treatment of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock in AdultsДокумент14 страницCorticosteroids in The Treatment of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock in AdultsTatiana Salvatierra RiosОценок пока нет

- Sample Templates - Comprehensive Bundle 2.0Документ11 страницSample Templates - Comprehensive Bundle 2.0shaniОценок пока нет

- 417 FullДокумент7 страниц417 FullshaniОценок пока нет

- Han, N. Et Al. 2016. Research Progress On Natural Benzophenanthridine Alkaloids and Their Pharmacological Functions A ReviweДокумент9 страницHan, N. Et Al. 2016. Research Progress On Natural Benzophenanthridine Alkaloids and Their Pharmacological Functions A ReviweshaniОценок пока нет

- Laporan Magang SherlyДокумент79 страницLaporan Magang SherlyshaniОценок пока нет

- 13CNMRfor322 PDFДокумент45 страниц13CNMRfor322 PDFshaniОценок пока нет

- Nguyen. 2016. Anti-Inflammatory Terpenylated Coumarins From The Leaves of Zanthoxylum Schinifolium With A-Glucosidase Inhibitory ActivityДокумент6 страницNguyen. 2016. Anti-Inflammatory Terpenylated Coumarins From The Leaves of Zanthoxylum Schinifolium With A-Glucosidase Inhibitory ActivityshaniОценок пока нет

- Guetchueng 2018 - Zanthoamides G-I (Three New Alkamides From Zanthoxylum Zanthoxyloides)Документ5 страницGuetchueng 2018 - Zanthoamides G-I (Three New Alkamides From Zanthoxylum Zanthoxyloides)shaniОценок пока нет

- Soal - Home Office Vs Branch (40%) : Total Informasi TambahanДокумент2 страницыSoal - Home Office Vs Branch (40%) : Total Informasi Tambahanshani100% (1)

- Chen. 2005. New Indolopyridoquinazoline, Benzo (C) Phenanthridines and Cytotoxic Constituents From Zanthoxylum Integrifoliolum-DikonversiДокумент7 страницChen. 2005. New Indolopyridoquinazoline, Benzo (C) Phenanthridines and Cytotoxic Constituents From Zanthoxylum Integrifoliolum-DikonversishaniОценок пока нет

- Kepel Fruit Has Been Known To Have Efficacy As An Oral Deodorant in Java IslandДокумент2 страницыKepel Fruit Has Been Known To Have Efficacy As An Oral Deodorant in Java IslandshaniОценок пока нет

- Development of Prediction Model and Experimental Validation in Predicting The Curcumin Content of Turmeric (Curcuma Longa L.)Документ17 страницDevelopment of Prediction Model and Experimental Validation in Predicting The Curcumin Content of Turmeric (Curcuma Longa L.)shaniОценок пока нет

- Penilaian Farmakokinetik ObatДокумент12 страницPenilaian Farmakokinetik ObatshaniОценок пока нет

- Pharmacokinetic Interaction Between HighДокумент7 страницPharmacokinetic Interaction Between HighshaniОценок пока нет

- The Clinical Use of Drugs. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Pennsylvania, United StatesДокумент4 страницыThe Clinical Use of Drugs. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Pennsylvania, United StatesshaniОценок пока нет

- Kimia Medisinal: October 1995Документ2 страницыKimia Medisinal: October 1995shaniОценок пока нет

- 477-540-4-PB 1 KolomДокумент7 страниц477-540-4-PB 1 KolomshaniОценок пока нет

- Kromatografi Kolom AdsorbsiДокумент13 страницKromatografi Kolom AdsorbsishaniОценок пока нет

- Shiroky 2 KolomДокумент10 страницShiroky 2 KolomShania Astanti SimanjuntakОценок пока нет

- 477-540-4-PB 1 KolomДокумент7 страниц477-540-4-PB 1 KolomshaniОценок пока нет

- Pharmacokinetic Interaction Between HighДокумент1 страницаPharmacokinetic Interaction Between HighshaniОценок пока нет

- Modul P.farmasetik IIДокумент9 страницModul P.farmasetik IIshaniОценок пока нет

- Vii Eng Second Mid Term Online Exam QuestionДокумент5 страницVii Eng Second Mid Term Online Exam QuestionAsghar AliОценок пока нет

- Zest Pharma, MarketingДокумент6 страницZest Pharma, Marketingbhawsar_indore100% (1)

- Top 10 medication safety tips and reducing high-risk medication errorsДокумент1 страницаTop 10 medication safety tips and reducing high-risk medication errorsGabee MoralesОценок пока нет

- OTC Medicines ListДокумент32 страницыOTC Medicines ListKebron DanielОценок пока нет

- Wisconsin - Claims Paid - FPW - 2007-2010Документ114 страницWisconsin - Claims Paid - FPW - 2007-2010Matt J KorgerОценок пока нет

- Monitoring of Patients On Long-Term Glucocorticoid TherapyДокумент10 страницMonitoring of Patients On Long-Term Glucocorticoid TherapyFitriyana WinarnoОценок пока нет

- Law and EthicsДокумент11 страницLaw and EthicslkvhqjsgdОценок пока нет

- 150Документ68 страниц150Andrei Miguel RoqueОценок пока нет

- MP Pakistan Q1 2016Документ102 страницыMP Pakistan Q1 2016Ahmed AshrafОценок пока нет

- Infected Blanket Policies:: Joan Jack, B.Ed, LLB, #OjibwaywarriormomДокумент17 страницInfected Blanket Policies:: Joan Jack, B.Ed, LLB, #OjibwaywarriormomJoan JackОценок пока нет

- Access To Quality Medicines: Rajasthan Model: "Reaching The Unreached"Документ7 страницAccess To Quality Medicines: Rajasthan Model: "Reaching The Unreached"v_ratОценок пока нет

- PionneringДокумент20 страницPionneringlaa7dОценок пока нет

- Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs 18 EdДокумент1 154 страницыHandbook of Nonprescription Drugs 18 EdLaila M. Elmougy100% (1)

- 3B - Clinical PharmacyДокумент35 страниц3B - Clinical PharmacyekramОценок пока нет

- Project Scope StatementДокумент4 страницыProject Scope StatementAndreosPapadopoloCruz50% (2)

- Wilmont's Pharmacy Project Scope StatementДокумент4 страницыWilmont's Pharmacy Project Scope StatementAngshuman Buragohain100% (1)

- Patient Satisfaction With Healthcare Services: A Bangladesh ScenarioДокумент8 страницPatient Satisfaction With Healthcare Services: A Bangladesh ScenarioA. K. MohiuddinОценок пока нет

- Sourav Das, Roll No 23, Hospital PharmacyДокумент17 страницSourav Das, Roll No 23, Hospital PharmacySourav DasОценок пока нет

- Ask Assess Advise ExplainedДокумент1 страницаAsk Assess Advise Explainedlanamalay12100% (1)

- Introduction Clinical Pharmacology 9th Visovsky Test BankДокумент6 страницIntroduction Clinical Pharmacology 9th Visovsky Test BanksonyaaaqОценок пока нет

- Hospital Information Management System - Cover PageДокумент15 страницHospital Information Management System - Cover Pageapi-1946401583% (6)

- Notice: Applications, Hearings, Determinations, Etc.: Millette, Michael J., M.D.Документ4 страницыNotice: Applications, Hearings, Determinations, Etc.: Millette, Michael J., M.D.Justia.comОценок пока нет

- Module 2Документ30 страницModule 2mannanОценок пока нет

- SH Conversation ExampleДокумент2 страницыSH Conversation ExampleHannah WilkerОценок пока нет

- National Open University of Nigeria: Prepared byДокумент17 страницNational Open University of Nigeria: Prepared byMAVERICK MONROEОценок пока нет

- Unit I Lecture II PharmacologyДокумент38 страницUnit I Lecture II PharmacologyImad khanОценок пока нет

- Gilead FCA LawsuitДокумент68 страницGilead FCA LawsuitAlex Kacik100% (5)

- TgaДокумент33 страницыTgavarun rajОценок пока нет

- Research ProjectДокумент13 страницResearch Projectapi-358146672Оценок пока нет

- The BAR - Philippine Digested Cases - Landmark Case - RH BILL CASE - Imbong Vs Ochoa Et - Al. G.R. No. 204819 April 8, 2014 (Digested Case)Документ8 страницThe BAR - Philippine Digested Cases - Landmark Case - RH BILL CASE - Imbong Vs Ochoa Et - Al. G.R. No. 204819 April 8, 2014 (Digested Case)Patronus GoldenОценок пока нет