Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Editorial: Twentieth Century Communism - Issue 9

Загружено:

RolandoОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Editorial: Twentieth Century Communism - Issue 9

Загружено:

RolandoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Editorial

he term ‘cultural turn’ is generally associated with a shift in leftist,

T socialist and communist politics after 1956. The upheavals of that

year – primarily Soviet intervention in Hungary and Nikita

Khrushchev’s revelation of the atrocities committed by Stalin – triggered

realignments on the left, both within and without of the communist

movement. At the very least, the Soviet Union’s claim to a scientifically

rigorous interpretation of marxism was damaged. More accurately, the

Soviets’ position as a revolutionary exemplar – a workers’ state building

towards a progressive, democratic socialism on the foundations of

marxist theory – was effectively undermined. As is well-known, there

followed a period of rancour and division across the communist

movement. Splits and soul-searching competed with blinkered intransi-

gence and engrained loyalties too deep-rooted to expunge. New guides

and approaches were sought: marxist thinkers from the past were dusted

off and re-assessed; new theories were forged that ostensibly grew from

Marx but often strayed so far as to break away into -isms of varying hue

and relevance. The ‘new’ became ‘post’ as certainties dissolved into a

vista of subjectivities.

This issue of Twentieth Century Communism was inspired by two

things. First, the ‘cultural’ dimension of post-56 leftist politics may be

read in a number of ways. In reductionist terms, it points to a refocusing

of marxist praxis away from class and economics and towards the

broader processes by which the ruling class asserts and maintains its

power. Most famously, of course, Antonio Gramsci’s notion of hegemony

began to inform leftist thinking, inspiring activists to engage in struggles

beyond the workplace and in life itself. But what did this mean in

practice? Theories of ‘hegemony’ and ‘cultural materialism’ remain

pertinent today – the ideas of Gramsci, Raymond Williams and others

continue to provide insight. But they also generated fierce discussion

Twentieth Century Communism – Issue 9

20th Century Communism 9.indd 5 06/08/2015 11:05:47

6 Editorial

within the left that fed into and informed the trajectories of individuals

and movements ostensibly committed to the same revolutionary

objective. The fragmentation of the left post-56 was both a product of

its vibrancy and the increasingly contested nature of its point and

purpose. Attention, therefore, may be fruitfully given to both the ideas

generated by the new left and across the ‘new social movements’ that

evolved into the later twentieth century and to the ramifications of such

developments on the composition of the left, its priorities, and the

spaces in which it functioned.

Second, culture – as in the arts, sports and so on – always claimed a

place in the communist schema. Debates over the revolutionary role of

the artist and of culture more generally have long been filtered through

a marxist lens to locate its value as a ‘weapon in the struggle’ or as a

component part of a developing socialism. From Russian futurism to

rock‘n’roll, surrealism to folk music, political meanings were read into or

projected through cultural forms as diverse as they were conflicting. In

Britain, 1930 saw debate within the British party as to coverage of ‘capi-

talist’ sport (especially football and horse racing) in the Daily Worker; in

the early 1970s, youth culture came under the party microscope. In both

cases, tensions emerged between those concerned with the mode of

(cultural) production and those interested in the ways by which the

working class adopted and participated in cultural activity. Neither

debate brought definitive answers (dare we say it, but taste and personal

proclivities often seemed to rub against – or were tenuously justified by

– ‘scientific’ analysis). As a result, the contested nature of culture was

revealed in ways that informed class relations and political priorities.

The articles compiled here thereby serve two purposes. First, to explore

instances where culture informed political debate within the communist

movement; second, to examine how the wider ‘cultural turn’ fed into

communism’s development over the twentieth century. No claim is made

to a comprehensive analysis. Rather, we conceived this issue as a kind of

historical prospecting … drilling into times and places to uncover

moments of cultural contestation, experimentation and politicisation.

Several of the articles stemmed from papers given at a symposium

sponsored by the Political Studies Association in Durham in January

2014. Others were commissioned to fit the requisite theme. The first

Twentieth Century Communism – Issue 9

20th Century Communism 9.indd 6 06/08/2015 11:05:47

Editorial 7

two, by Mattie Fitch and Fiona Haig, take us up to 1956. Fitch investi-

gates the politics of the French Communist Party during the popular

front, considering the extent to which this may be read as a precursor to

the post-war ‘turn’. Haig, meanwhile, concentrates on the Italian party,

specifically the Gorizia federation’s attempts to realign its politics in

response to the shock of the Soviet’s intervention in Hungary.

Key to the post-56 ‘cultural turn’ was the emergence of youth-cultural

and counter-cultural movements that challenged Communist Party

claims to provide the revolutionary vanguard. Just what was the revolu-

tionary potential of a youth-centric politics and culture? Was rock‘n’roll

the soundtrack to rebellion; or simply a distraction to detour a rebellious

spirit into ‘safe’ and profitable channels? Tim Brown tackles the issue

head-on, focusing on Germany, to consider how communist and

counter-cultural politics interacted around the conjuncture of 1968.

Back in the UK, Paul Stott looks at how the emergence of ‘identity poli-

tics’ over the 1960s and 1970s led to fissures that cut across the

unravelling left and continue today.

Two shorter pieces conclude. Mike Waite assesses the political trajec-

tory of Cornelius Cardew, whose adoption of maoism in the early 1970s

led him to rethink his cultural politics and eschew his earlier avant

gardism. Gavin Bowd follows Nicolae Ceaușescu’s own peculiar cultural

revolution, revealing how it helped prepare the way to his overthrow in

1989.

Taken all together, we hope the issue intrigues and kindles interest in

communist culture and cultural politics more generally. That culture

provided a contested space for communists to engage in the struggle

should, in itself, inspire further research. But the ramifications of the

‘cultural turn’, with regard to the class basis of marxism and the evolution

of the left, deserves far closer attention than has been given hitherto.

Twentieth Century Communism – Issue 9

20th Century Communism 9.indd 7 06/08/2015 11:05:47

Вам также может понравиться

- The FRANKFURT SCHOOL - Cultural RevolutionДокумент17 страницThe FRANKFURT SCHOOL - Cultural RevolutionzepolkОценок пока нет

- The Nature of Fascism RevisitedДокумент26 страницThe Nature of Fascism RevisitedFrancisco Cobo RomeroОценок пока нет

- Cultural Revolution and Revolutionary Culture by Alejandro RussoДокумент349 страницCultural Revolution and Revolutionary Culture by Alejandro RussoJoãoОценок пока нет

- Beck - Theory Culture SocietyДокумент5 страницBeck - Theory Culture SocietyPedro A. CaribéОценок пока нет

- The History ManДокумент8 страницThe History ManSachin KetkarОценок пока нет

- Stuart Hall: LIFE AND TIMES OF THE FIRST NEW LEFTДокумент20 страницStuart Hall: LIFE AND TIMES OF THE FIRST NEW LEFTTigersEye99Оценок пока нет

- 10 Essential Money Management Rules in Forex TradingДокумент10 страниц10 Essential Money Management Rules in Forex TradingAbo Abdullah100% (1)

- What Is Folksocialism A Critical AnalysisДокумент55 страницWhat Is Folksocialism A Critical AnalysisAcaDuma100% (1)

- Universities and Left ReviewДокумент5 страницUniversities and Left ReviewkilimandzsaroОценок пока нет

- Social Theory: Ideas in Profile: Ideas in ProfileОт EverandSocial Theory: Ideas in Profile: Ideas in ProfileРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (2)

- E. Batalov-The Philosophy of Revolt (Criticism of Left Radical Ideology)Документ123 страницыE. Batalov-The Philosophy of Revolt (Criticism of Left Radical Ideology)mickeyvinca100% (1)

- Gavin Smith 2004 HegemonyДокумент22 страницыGavin Smith 2004 HegemonyShaggall100% (1)

- SocialismДокумент10 страницSocialismHarshita SachanОценок пока нет

- A Cost-Effective Rig MoveДокумент4 страницыA Cost-Effective Rig MoveNA NAОценок пока нет

- The French Revolution in Cultural HistoriesДокумент11 страницThe French Revolution in Cultural HistoriesNitin VermaОценок пока нет

- CILAДокумент8 страницCILAbobyОценок пока нет

- Fascism and Philosophy: The Case of Actualism: Fogu, Claudio, 1963Документ20 страницFascism and Philosophy: The Case of Actualism: Fogu, Claudio, 1963Seed Rock ZooОценок пока нет

- Lukács and FascismДокумент13 страницLukács and FascismVincent SungОценок пока нет

- The Left in History: Revolution and Reform in Twentieth-Century PoliticsОт EverandThe Left in History: Revolution and Reform in Twentieth-Century PoliticsОценок пока нет

- Ngos in PakistanДокумент13 страницNgos in Pakistanapi-339753830100% (1)

- Company Profile PT. Nikkatsu Electric WorksДокумент17 страницCompany Profile PT. Nikkatsu Electric WorksDenny Ilyas Attamimi100% (1)

- The Dead End of The Left?Документ8 страницThe Dead End of The Left?Randall HittОценок пока нет

- Structural,: PDF Compression, Ocr, Web-Optimization With Cvision'S PdfcompressorДокумент174 страницыStructural,: PDF Compression, Ocr, Web-Optimization With Cvision'S PdfcompressorZuhal ZaeemОценок пока нет

- Enduring Socialism: Explorations of Revolution and Transformation, Restoration and ContinuationОт EverandEnduring Socialism: Explorations of Revolution and Transformation, Restoration and ContinuationОценок пока нет

- Socialism StampedДокумент8 страницSocialism StampedbegajardoОценок пока нет

- Andrew - Heywood - End of IdeologyДокумент12 страницAndrew - Heywood - End of Ideologya86092067Оценок пока нет

- Culture, Class, and Communism: The Politics of Rock in The West German 1968Документ28 страницCulture, Class, and Communism: The Politics of Rock in The West German 1968RolandoОценок пока нет

- Ellen Meiksins Wood - A Chronology of The New Left & Its SuccessorsДокумент28 страницEllen Meiksins Wood - A Chronology of The New Left & Its SuccessorsDorrrianОценок пока нет

- Marxism in The Post-Globalization EraДокумент13 страницMarxism in The Post-Globalization EraValdai Discussion ClubОценок пока нет

- Tips The Sociology of Modernization and Development ExportДокумент60 страницTips The Sociology of Modernization and Development ExportTanya SinghОценок пока нет

- Koves Lukacs FascismДокумент13 страницKoves Lukacs FascismTijana OkićОценок пока нет

- Hall, Peter-Dilemmas Social Scence (Draft)Документ27 страницHall, Peter-Dilemmas Social Scence (Draft)rebenaqueОценок пока нет

- The Future of Class in HistoryДокумент9 страницThe Future of Class in HistoryAntonio JairОценок пока нет

- Expressionism Futurism and The Dream of Mass DemocracyДокумент23 страницыExpressionism Futurism and The Dream of Mass DemocracyPapuna ChivadzeОценок пока нет

- Discuss How Socio-Political Tensions in The 19th Century Europe Gave Rise To The Development of SociologyДокумент10 страницDiscuss How Socio-Political Tensions in The 19th Century Europe Gave Rise To The Development of Sociologysanya awanaОценок пока нет

- Cubaand Civil SocietyДокумент16 страницCubaand Civil SocietyIgor MarquezineОценок пока нет

- The Sixties in Hungary Some Historical A PDFДокумент20 страницThe Sixties in Hungary Some Historical A PDFZsolt FehérváriОценок пока нет

- Intro To SI BookletДокумент4 страницыIntro To SI BookletEmil SabotОценок пока нет

- Chapter 21 Michael Harrington From Socialism Past and PresentДокумент4 страницыChapter 21 Michael Harrington From Socialism Past and Presentekateryna249Оценок пока нет

- The Diversion of CultureДокумент10 страницThe Diversion of CultureJulio FerreiraОценок пока нет

- L'Internationale Situationniste, Socialisme Ou Barbarie, and The Crisis of The Marxist ImaginaryДокумент30 страницL'Internationale Situationniste, Socialisme Ou Barbarie, and The Crisis of The Marxist ImaginaryjohnsgreenОценок пока нет

- Gorizian Heretics of 1956: Euro-Communism Starts Here?: Fiona HaigДокумент32 страницыGorizian Heretics of 1956: Euro-Communism Starts Here?: Fiona HaigRolandoОценок пока нет

- Bourgeois RevolutionДокумент16 страницBourgeois Revolutionbptseren1Оценок пока нет

- Casals - 2019 - Anticommunism in 20th-Century Chile From The "SocДокумент30 страницCasals - 2019 - Anticommunism in 20th-Century Chile From The "SocMarcelo Casals ArayaОценок пока нет

- Davis Et Al, Cultural Studies NowДокумент20 страницDavis Et Al, Cultural Studies NowMark TrentonОценок пока нет

- No Socialism in The United States? He Answered, "On The Reefs of Roast Beefand Apple PieДокумент1 страницаNo Socialism in The United States? He Answered, "On The Reefs of Roast Beefand Apple PieKAMULALIОценок пока нет

- On The Rise and Decline of Totalitarian Liberalism: Schlesinger, Bell, Larouche Larry PortisДокумент17 страницOn The Rise and Decline of Totalitarian Liberalism: Schlesinger, Bell, Larouche Larry PortisIfix AnythingОценок пока нет

- Marxism, Film and Theory: From Barricades To PostmodernismДокумент23 страницыMarxism, Film and Theory: From Barricades To PostmodernismNagarajuNoolaОценок пока нет

- Socialism Heywood ChapterДокумент42 страницыSocialism Heywood ChapterKarthick Padmanaban100% (1)

- YQiao - Power and Constraints - Ideas As A Social Force in China's Early Modern HistoryДокумент38 страницYQiao - Power and Constraints - Ideas As A Social Force in China's Early Modern HistoryFlying StardustОценок пока нет

- French Revolution Political HistoriographyДокумент11 страницFrench Revolution Political HistoriographyRishali Chauhan 84Оценок пока нет

- Massimo T.The New Left A Documentary History PDFДокумент483 страницыMassimo T.The New Left A Documentary History PDFLatur1100% (3)

- Althusser's Marxism - PlatypusДокумент14 страницAlthusser's Marxism - PlatypusNegative--Оценок пока нет

- EDER. A New Social MovementДокумент16 страницEDER. A New Social MovementMarco Antonio GavérioОценок пока нет

- Red Polemique - Marxism and The Question of IdentityДокумент20 страницRed Polemique - Marxism and The Question of IdentityShishir GuptaОценок пока нет

- Global Fascism Geography Timing Support and StrategyДокумент22 страницыGlobal Fascism Geography Timing Support and Strategyfb101406Оценок пока нет

- Faizan Yousuf ShanДокумент14 страницFaizan Yousuf ShanFaizan Yousuf ShanОценок пока нет

- Uribe Vs SantosДокумент7 страницUribe Vs SantosprralunaОценок пока нет

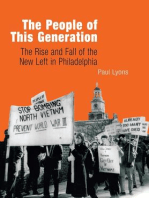

- The People of This Generation: The Rise and Fall of the New Left in PhiladelphiaОт EverandThe People of This Generation: The Rise and Fall of the New Left in PhiladelphiaОценок пока нет

- The Sixties and The Advent of PostmodernismДокумент19 страницThe Sixties and The Advent of PostmodernismNawresОценок пока нет

- Speech at The GPCR and Lessons of The Working Class MovementДокумент13 страницSpeech at The GPCR and Lessons of The Working Class MovementKalovski Itim100% (1)

- Eduard Bernstein On Socialism Past and Present Essays and Lectures On Ideology 1St Edition Marius S Ostrowski Full ChapterДокумент68 страницEduard Bernstein On Socialism Past and Present Essays and Lectures On Ideology 1St Edition Marius S Ostrowski Full Chapterrhea.dixon130100% (8)

- Johann P. Arnason (1982) Perspectives and Problems of Critical Marxism in Eastern Europe (Part Two)Документ31 страницаJohann P. Arnason (1982) Perspectives and Problems of Critical Marxism in Eastern Europe (Part Two)maxfrischfaberОценок пока нет

- 20th Congress of CPSU Moni GuhaДокумент7 страниц20th Congress of CPSU Moni GuhaDamodar LokpakshОценок пока нет

- Skcopol PDFДокумент22 страницыSkcopol PDFRolando100% (1)

- 4 The Aspirations of Russian SocietyДокумент41 страница4 The Aspirations of Russian SocietyRolandoОценок пока нет

- Comunismo LocalДокумент14 страницComunismo LocalRolandoОценок пока нет

- 11 Explaining Revolutions in The Contemporary Third WorldДокумент20 страниц11 Explaining Revolutions in The Contemporary Third WorldRolando100% (1)

- 1 - Rex WADEДокумент27 страниц1 - Rex WADERolandoОценок пока нет

- Sckopol 14 PDFДокумент44 страницыSckopol 14 PDFRolandoОценок пока нет

- 5 The Peasants and The Purposes of RevolutionДокумент17 страниц5 The Peasants and The Purposes of RevolutionRolandoОценок пока нет

- Sckopol 14 PDFДокумент44 страницыSckopol 14 PDFRolandoОценок пока нет

- Wallerstein's World Capitalist System: A Theoretical and Historical CritiqueДокумент17 страницWallerstein's World Capitalist System: A Theoretical and Historical CritiqueRolandoОценок пока нет

- 11 Conclusion: Phoebe in Arcadia: Arcadian Tales Are Hard-Luck Stories TooДокумент14 страниц11 Conclusion: Phoebe in Arcadia: Arcadian Tales Are Hard-Luck Stories TooRolandoОценок пока нет

- Sckopol 4 PDFДокумент25 страницSckopol 4 PDFRolandoОценок пока нет

- 11 Conclusion: Phoebe in Arcadia: Arcadian Tales Are Hard-Luck Stories TooДокумент14 страниц11 Conclusion: Phoebe in Arcadia: Arcadian Tales Are Hard-Luck Stories TooRolandoОценок пока нет

- Bibliography: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010Документ26 страницBibliography: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010RolandoОценок пока нет

- 9 Love: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010Документ17 страниц9 Love: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010RolandoОценок пока нет

- 3 Lives and Writing: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010Документ19 страниц3 Lives and Writing: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010RolandoОценок пока нет

- Steedman 11Документ24 страницыSteedman 11RolandoОценок пока нет

- 8 The Gods: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010Документ24 страницы8 The Gods: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010RolandoОценок пока нет

- 7 Relations: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010Документ21 страница7 Relations: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010RolandoОценок пока нет

- 2 Wool, Worsted and The Working Class: Myths of OriginДокумент18 страниц2 Wool, Worsted and The Working Class: Myths of OriginRolandoОценок пока нет

- 8 The Gods: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010Документ24 страницы8 The Gods: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010RolandoОценок пока нет

- 6 Teaching: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010Документ21 страница6 Teaching: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010RolandoОценок пока нет

- 2 Wool, Worsted and The Working Class: Myths of OriginДокумент18 страниц2 Wool, Worsted and The Working Class: Myths of OriginRolandoОценок пока нет

- 4 Labour: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010Документ21 страница4 Labour: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010RolandoОценок пока нет

- 1 Introduction: On Service and Silences: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010Документ16 страниц1 Introduction: On Service and Silences: Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2010RolandoОценок пока нет

- 7 From Blitzkrieg To Total War: Controversial Links Between Image and RealityДокумент27 страниц7 From Blitzkrieg To Total War: Controversial Links Between Image and RealityRolandoОценок пока нет

- Andrew BarnardДокумент29 страницAndrew BarnardRolandoОценок пока нет

- 13 Work, Gender and Everyday Life: Reflections On Continuity, Normality and Agency in Twentieth-Century GermanyДокумент32 страницы13 Work, Gender and Everyday Life: Reflections On Continuity, Normality and Agency in Twentieth-Century GermanyRolandoОценок пока нет

- The Contradictions of Continuous Revolution: Michael MannДокумент23 страницыThe Contradictions of Continuous Revolution: Michael MannRolandoОценок пока нет

- The Contradictions of Continuous Revolution: Michael MannДокумент23 страницыThe Contradictions of Continuous Revolution: Michael MannRolandoОценок пока нет

- 13 Work, Gender and Everyday Life: Reflections On Continuity, Normality and Agency in Twentieth-Century GermanyДокумент32 страницы13 Work, Gender and Everyday Life: Reflections On Continuity, Normality and Agency in Twentieth-Century GermanyRolandoОценок пока нет

- Types of SlabsДокумент5 страницTypes of SlabsOlga KosuoweiОценок пока нет

- FOE: Session 5: Economic Systems Capitalism Socialism Communism Mixed EconomyДокумент4 страницыFOE: Session 5: Economic Systems Capitalism Socialism Communism Mixed EconomylulughoshОценок пока нет

- Executive SummaryДокумент21 страницаExecutive SummaryAbhijeet TaliОценок пока нет

- How Are Wages Determined by The Marginal Productivity of LaborДокумент4 страницыHow Are Wages Determined by The Marginal Productivity of LaborsukandeОценок пока нет

- López Quispe Alejandro MagnoДокумент91 страницаLópez Quispe Alejandro MagnoAssasin WildОценок пока нет

- Unit 1.1 India's Stalled RiseДокумент3 страницыUnit 1.1 India's Stalled RiseKushagra AroraОценок пока нет

- Sınav 1Документ27 страницSınav 1denememdirbuОценок пока нет

- Dry Coal ProcessingДокумент16 страницDry Coal ProcessingmosesmattekkОценок пока нет

- 2nd Annual Balik Scientist Program Convention 2Документ3 страницы2nd Annual Balik Scientist Program Convention 2kaiaceegeesОценок пока нет

- Azulcocha 43-101 Tailing ReportДокумент80 страницAzulcocha 43-101 Tailing Reportwalter sanchez vargasОценок пока нет

- BFAR JournalizingДокумент3 страницыBFAR Journalizingangelica joyce caballesОценок пока нет

- Horasis Global India Business Meeting 2010 - Programme BrochureДокумент32 страницыHorasis Global India Business Meeting 2010 - Programme BrochuresaranshcОценок пока нет

- 1.1 Introduction To Financial CrisisДокумент13 страниц1.1 Introduction To Financial CrisisvarshikaОценок пока нет

- BillДокумент1 страницаBillAskari NaqviОценок пока нет

- Survey Questionnaire On Microfinance Loan Impact Before and AfterДокумент4 страницыSurvey Questionnaire On Microfinance Loan Impact Before and AfterAli ManXoorОценок пока нет

- Tourism in Jammu & Kashmir: Submitted By: Rajat Singh Submitted To: Prof.M Y KhanДокумент8 страницTourism in Jammu & Kashmir: Submitted By: Rajat Singh Submitted To: Prof.M Y KhanRAJAT SINGH MBA-2017Оценок пока нет

- Power Sector Market Report EthiopiaДокумент11 страницPower Sector Market Report EthiopiaephremОценок пока нет

- MR Mohan LalДокумент5 страницMR Mohan LalRajkumarОценок пока нет

- RAtex PresentationsДокумент10 страницRAtex PresentationsDian Ayunita Nugraheni Nurmala Dewi100% (1)

- سياسات بنك السودان المركزي للعام 2022مДокумент12 страницسياسات بنك السودان المركزي للعام 2022مAhmed IbrahimОценок пока нет

- 5037asd8876 HKDAДокумент4 страницы5037asd8876 HKDAdaedric13100% (1)

- Study Id95787 Wealth Management in IndiaДокумент40 страницStudy Id95787 Wealth Management in IndiaAbhinandhNairОценок пока нет

- Case StudyДокумент1 страницаCase StudyJaya MishraОценок пока нет

- Policy On Intellectual Property in KenyaДокумент50 страницPolicy On Intellectual Property in KenyaE Kay Mutemi100% (1)