Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Instrumen Habits of Mind

Загружено:

Anisa SafitriОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Instrumen Habits of Mind

Загружено:

Anisa SafitriАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Gazette 54#1_final_layout 15-08-29 1:00 PM Page 28

but none were competitive” (p. 219). However, the co-

operative element is couched in a competitive

environment, such as a team relay competition. Similarly:

THINKING ABOUT

“I’m not interested in how many people I beat, or what TEACHING, LEARNING, AND

place I finish. It is me versus the clock” (p. 74). However, MATHEMATICAL MINDSETS

this vision is not consistent when an episode of playing LEADS ME TO LEARNING

the rules is explained. In the account, the protagonist

constrains the possible solutions and repeatedly hands

SKILLS

in answers (allowed by the rules) until she reaches the

correct one.

JAMIE PYPER

E-MAIL: pyperj@queensu.ca

As a teacher, I have always wrestled with the

WEBSITE:

dominance of contest-oriented enrichment. This book, in

HTTP://EDUC.QUEENSU.CA/MSTE

spite of its strength of providing a valuable resource in Jamie is an Assistant Professor of

math education, does not address non-competitive Mathematics Education, and the

enrichment. Given the Canadian math landscape, I was Coordinator of a research and curriculum

not surprised by this. However, teachers should be development team, the Mathematics, Science, Technology

aware that the book provides an in-depth view of a very Education Group (MSTE), at the Faculty of Education,

specific form of enrichment. Queen’s University. He spent 20 years teaching high school

Overall, Richard Hoshino has provided an important mathematics in two school boards in Ontario and

contribution to math educators and should be applauded mathematics education at Western University. He has been

a member of OAME since 1995 and is often a workshop

for this book. The spirit it brings makes it an excellent

presenter at OAME and local chapter conferences.

enrichment prospect for high school students. It is well

suited to school libraries, a classroom bookshelf, and as

a potential motivational gift for students who deserve “All learning begins when our comfortable ideas

special treatment. turn out to be inadequate.” ~ John Dewey

The Ontario math curriculum states that assessment

and instruction should be seamless (OME, 2010); others

say that classroom management and instruction should

be seamless (e.g., Jones, Jones, & Jones, 2000); and

some state that curriculum and assessment should be

seamless (e.g., Drake, Reid, & Kolohon, 2014). Each of

these statements comes from a particular perspective

that is theoretical, practical, or a combination of both. I

would like to focus these perspectives into a mathematics

classroom context—the space teachers live and work in

for hours a day with hundreds of students. It is what has

happened in my mathematics classroom that has helped

me realize, over time, when my comfortable ideas of

teaching mathematics became inadequate, when student

learning was as uninspired as the routine of my teaching,

and like a badly designed spiral curriculum, I was going

around in circles and never really feeling like everything

came together at the same time. Don’t get me wrong, I

saw regular successes in my students’ achievement, and

felt I had many good teaching moments, but a growing

sense of inadequacy prodded me to broaden my

knowledge base and then my professional practice.

I began to conceptualize my professional practice with

the metaphor of the centre of gravity, or centroid, of a

28 SEPT 2015 OAME/AOEM GAZETTE

Gazette 54#1_final_layout 15-08-29 1:00 PM Page 29

triangle. Imagine a piece of cardboard, cut into the shape becoming increasingly visible in the policies, documents,

of a triangle, balanced on the end of a pencil placed at its and curriculum for mathematics courses and schools in

centroid. Consider the vertices to represent classroom which I teach. The current vehicle to achieve something

management, instruction, and assessment (see Figure 1), like facility in twenty-first-century skills is our schools and

and this balanced triangle represents a teacher ’s our classrooms. I wonder how a student can learn these

professional practice. Knowing a single metaphor may twenty-first-century skills, as well as the mathematics of

not be able to capture everything, and for the sake of the curriculum, without the skills of learning, or Learning

argument and simplification, I imagine that these three Skills. When I ask my students, they agree that it is hard

vertices represent the sum of all the wisdom and to learn something without Learning Skills.

understanding of what teaching is all about—everything As teachers, we also develop twenty-first-century

we know about teaching can be captured within the skills, such as our own multiple literacies, or professional

metaphor of this triangle. The challenge for the classroom literacies (Pyper, Chin, & Reeve, 2015). Current thinking

teacher is to maintain that balance in professional about learning is giving us some new language about

practice—do not let the triangle get too heavy on any one teaching and learning. Professional literacies of learning

side or vertex and slip off the pencil. However, this can be and teaching are expanding with ideas like “fixed” and

difficult because we continue to learn so much about the “growth mindsets” (see Dweck, 2006). These ideas in

teaching and learning of mathematics as we develop particular represent concepts of learning and thinking that

knowledge and skills in these areas of professional are providing insight into learners’ motivations, efforts,

practice, and we risk upsetting the balance if we focus too and identities. These ideas and issues are important to

much on any one aspect. So, as I learn, I continuously teachers and students. We wrestle with them daily in our

reflect on how classroom management, assessment, and lessons, tasks, and classrooms.

instruction are being affected, and how their interaction

Growth mindsets are important, and they develop

(rather than just the sum of their parts) must be

habits of mind. “A habit of mind is a pattern of intellectual

considered when I implement any new learning in my

behaviours that leads to productive actions” (Costa &

classroom teaching. This is my perspective on the lived

Kallick, 2008, p. 16). To explain the basic nature of this

experience of the classroom teacher—that context

pattern of intellectual behaviours, Costa and Kallick

matters, and this balance is achievable, and desirable.

describe six dimensions: i. value – choosing to employ

one pattern of intellectual behaviours over others; ii.

inclination – feeling a tendency to employ this pattern; iii.

sensitivity – perceiving opportunities to employ this

pattern; iv. capability – possessing the skills and

capacities to carry through with this pattern; v.

commitment – constantly reflecting on and improving

performance; and vi. policy – making it a personal policy

to embed this pattern into one’s thinking and actions.

Figure 1. A centroid metaphor for classroom practice Some of these dimensions sound strikingly similar to the

When I think of the students in my classes, I Ontario curriculum Learning Skills; for example,

appreciate that they are more than just students of a inclination is like initiative, sensitivity points to

classroom mathematics course. They are also citizens of organization, and commitment appears under self-

our current society, and twenty-first-century skills are regulation as persistence.

becoming an important outcome from schooling and But what are the specific habits of mind? Costa and

formal education. An overview of these twenty-first- Kallick (2008) list 16 habits of mind (see Table 1). Of the

century skills identifies them as critical thinking, problem 16 they identify, a number of them feel like they align with

solving, reasoning, creativity, imagination, innovation, other constructs and ideas about learning, which lends

perseverance, self-direction, self-discipline, initiative, support to the premise that these habits of mind are

collaboration, leadership, and active multiple literacies. authentic to our experiences of learning. Table 1 contains

These skills are appearing to be valuable to my students’ a partial list of some of these other constructs I can see

expressions of achievement and mathematical fitting in. As you read the list, what ideas and constructs

performance, but more importantly, these skills are of learning are you thinking about? (For further details

OAME/AOEM GAZETTE SEPT 2015 29

Gazette 54#1_final_layout 15-08-29 1:00 PM Page 30

about these habits of mind, see Costa and Kallick’s Goldenberg, & Mark, 1996 for details on these two

book.) approaches). In the process of exploring and explicating

the assessment of mathematics, the Harvard School of

Education (1995) described mathematical inquiry (or

® Resilience, self-efficacy

Habits of Mind Connections

thinking) as five phases using eight verbs: hypothesising,

® Self-regulation

Persisting

modelling and formulating, transforming and

Managing impulsivity

Listening with understanding manipulating, inferring and concluding, and

communicating. These may look familiar to many who

® Mathematical processes,

and empathy

taught or experienced the 1999 version of the Grades 9

Thinking flexibly

and 10 mathematics curriculum—these verbs formed a

Thinking about thinking problem solving

foundation to the pedagogical approach to that

(metacognition)

curriculum. Mason and Spence (1999) described two

® Assessment as learning

Striving for accuracy

Questioning and posing ways of knowing mathematics, knowing-about and

knowing-to. In essence, knowing-about consists of

® “Thinking” Achievement

problems

Applying past knowledge to knowing-that (the facts), knowing-how (the procedures),

and knowing-why (the reasons). Knowing-to, though, is

® “Communication”

new situations Category

Thinking and communicating the ultimate goal, and this kind of knowing is all about

knowing to act when presented with a problem, a

with clarity and precision Achievement Category

Gathering data through all situation, or question. (See Figure 2 for a visual graphic

of “knowing.”)

senses

“Once the moment of knowing-to takes place,

Creating, imagining, innovating

knowing-how takes over to exploit the fresh idea;

Responding with wonderment

knowing-that forms the ground, the base energy upon

® Learning Skill

and awe

which all else depends and on which actions depend;

Taking responsible risks

knowing-why provides an overview and sense of direction

Finding humour

that supports connection and modification if difficulties

Thinking interdependently

Remaining open to continuous arise en route” (p. 146).

As they described these two ways of knowing, Mason

learning

Table 1. The 16 Habits of Mind (Costa & Kallick, 2008) and & Spence linked them to assessment. The easy kind of

some associated connections to other teaching and learning assessment uses indicators of knowing-about, and the

constructs more challenging kind of assessment uses indicators of

knowing-to. Their contention is that it is the more

It will be beneficial for one’s learning to make these

challenging kind of assessment and mathematical

habits of mind automatic or natural states of thinking

performance (knowing-to) that we, as teachers, need to

because “habituation (Mason & Davis, 1989) is a

emphasise for the benefit of our students’ learning.

fundamental process through which people come to

know” (Mason & Spence, 1999, p. 152). Knowing, now, is

likely the crux of the issue. What do we know, and how do

we know it? It may be nice and wonderful to develop and

have habits of mind at our disposal, but what is the

epistemological sense of the knowledge that occurs

because of these habits? What is the nature of knowing

that we are habitually acting upon?

Here are three ways of “knowing” from a mathematics

perspective. Cuoco, Goldenberg, and Mark (2010) list

eight mathematical habits of mind: pattern sniffing,

Figure 2. Figure 1 from Mason & Spence (1999), page 145,

experimenting, describing, tinkering, inventing,

illustrating the relationship between knowing-about and

visualizing, conjecturing, and guessing. These habits of

knowing-to

mind are described through a geometrical approach and

an algebraic approach to thinking (see Cuoco,

30 SEPT 2015 OAME/AOEM GAZETTE

Gazette 54#1_final_layout 15-08-29 1:00 PM Page 31

LEVEL 1 LEVEL 2 LEVEL 3 LEVEL 4

Responsibility Coursework Completes ½ the Completes ¾ of the Completes all Completes all the

(at home and work, submits work, submits work, submits on work, submits on

consistently late. occasionally late. time every time. time and sometimes

in class) earlier.

Choices Avoids, ignores, Accepts Takes ownership Takes ownership

resists ownership responsibility for and responsibility and proactively

for choices. choices after it is for choices. makes necessary

brought to one’s choices.

attention.

Independent Work Accomplishing Does not start work Starts work after a Starts when told Starts right away

tasks until the teacher couple of requests and uses the class and uses the full

makes a personal by the teacher, uses period to complete class period to

request, does not about half the class task. complete the task.

complete task. period effectively.

Following Misses most Misses some of the Listens to Listens to all

instructions instructions from the instructions from the instructions and instructions and

teacher, follows teacher. can get to work. provides leadership

others’ lead, copies to others.

work.

Initiative Academic risk Not willing to take Hesitant, needs Willing, interested, Willing, curious,

taking risks, needs many prompts from needs few innovative, does not

continuous others to try prompts from need prompts from

prompting from something new. others to try anyone.

others to try something new.

something new.

Attitude Focuses on own Focuses on own Works for own and Works and

wants and needs. interests and others’ rights and advocates for own

Consistently “rights.” responsibilities. and others’ rights

negative outlook on Often pessimistic Positive outlook and responsibilities.

the course. outlook on the on the course. Optimistic and

course. upbeat.

Organization Prioritizing Makes no plans. Makes a plan. Establishes a plan Establishes,

Does not prioritize. Does things in the and prioritizes. prioritizes, and

order they are periodically updates

written. the plan.

Managing Comes to class with Brings some things, Before coming to Proactively

resources nothing. remembers once class, identifies, identifies, gathers,

he/she gets to the gathers, then uses uses, and evaluates

classroom. all resources. the use of all

resources.

Collaboration Peer relations/ Dependent. Independent. Interdependent. Effective, positive,

Working together Doesn’t participate, Doesn’t share with Shares ideas, interdependence.

just sits there. group. encourages Encourages critical

others’ thinking, elaborates

participation. on anyone’s ideas.

Everyone feels

valued.

Self-Regulation Goals Has no individual Sets unrealistic or Sets specific and Sets, monitors, and

goals. vague goals. achievable goals. re-evaluates

measurable goals.

Persistence First, and often the First attempt is Sticks to it and Will improve work,

only, reaction is to considered doesn’t give up. even after it has

give up. acceptable, works been assessed.

for a “pass.”

Figure 3. Learning Skills & Work Habits (2010)

OAME/AOEM GAZETTE SEPT 2015 31

Gazette 54#1_final_layout 15-08-29 1:00 PM Page 32

To consider the growth and development of knowing- Over the years, this was used by members of the math

to, what might we need to attend, to help our students department and the summer school math teachers. When

develop these habits of mind? Costa and Kallick (2008) I moved to a new school in 2009, three other teachers in

suggest we explore meanings, expand capacities, extend the new school (teaching English, History, and Science)

values, build commitment, and increase alertness. Again, started using this Learning Skills rubric and tracking

I notice an alignment of these four goals with the Ontario sheet. When the new Growing Success document was

curricular Learning Skills and mathematics processes. I published with six Learning Skills and included

feel embedding Learning Skills into our daily classroom modifications to the descriptions, the four of us tweaked

learning will meet each of these goals, which leads me to the Learning Skills rubric for the 2010 school year. This is

the questions, how would one teach for the habits of the rubric you see in Figure 3.

mind, how would one teach of the habits of mind, and

how would one teach with the habits of mind?

The centroid and triangle metaphor is my framework

for teaching—thinking of the seamlessness of

teaching/instruction, assessment for and of learning, and

classroom management of students’ learning, and

considering mathematical mindsets in the context of a

math classroom. So that teaching turns into students’

learning, the potential lynchpin to all of this is Learning

Skills. Learning Skills are described in Growing Success,

initially in the 1999 version, and now in the revised 2010

document. As a Grade 9 math teacher back in 1999, I

appreciated the value of Learning Skills, but found it

difficult to imagine how to incorporate them into my

classroom practice. During a staff meeting before report

card time in 2000, some colleagues presented a way to

capture Learning Skills in a one-off opportunity just in

time to gather some evidence and be able to add

something to the report card under Learning Skills. I

remember listening to their presentation and thinking that

Figure 4. Learning Skills rubric on a classroom wall

this is much too small a sample of Learning Skills

evidence for me to accurately describe and evaluate my There are a number of features to the design and

students’ Learning Skill levels for a report card. Walking implementation of this Learning Skills rubric. Size is

away from that presentation, I thought of the tracking important—it needs to be large and wall mounted for

sheet I was using for monitoring aspects of student everyone to see easily. I use regular 8.5x11 sheets of

classroom learning (see Pyper, 2005 for details about the paper in plastic page protectors for each cell of the rubric.

tracking sheet). This was a somewhat teacher-centric and Colour is important—the Level 3 column is the “standard,”

teacher-managed process, but wondering if I could add as defined by the Ontario curriculum, so I wanted a colour

Learning Skills to the tracking sheet inspired me to that students’ eyes would be drawn to first. Level 4 is a

imagine a more student-centric and student-managed goal, not a standard, and so I wanted students to feel

process. I developed a Learning Skills rubric from the purposeful if they were trying to achieve a Level 4, hence

then four Learning Skills of the curriculum. I used the the darker colour red. This is also a colour that requires

official document’s titles and descriptions and one to sometimes go up to the wall itself to read the

transformed the rubric criteria into language students words—in a small sense, the physical demand of going to

would accept and understand. I then wrote the four levels the wall increases the motivation to know what it says

of quality of the criteria, again in language students would and then act accordingly. The rubric’s Levels 1 and 2

understand. I implemented and tested in my classrooms, columns are the colour of the wall, designed to blend in

and responding to students questions and input over the and not look appealing—I don’t want students to select

next two semesters, improved the wording in the rubric. Level 1 or 2 as their goal, so I want these pages to either

be missed or ignored. The criteria for each Learning Skill

32 SEPT 2015 OAME/AOEM GAZETTE

Gazette 54#1_final_layout 15-08-29 1:00 PM Page 33

is chosen to reflect the behaviour or learning skill I have The implementation of this Learning Skills rubric is

seen most often in need and which might benefit successful for me in my math classroom because it aligns

students’ learning most. The descriptors in each level are with and supports so many aspects of instruction,

purposefully worded to make Levels 1 and 2 unappealing assessment, and classroom management (think of my

to students, so they strive for Level 3 as a standard level triangle metaphor.) This Learning Skills rubric is also

of achievement and behaviour. There is a tension successful for students in my math classroom because of

between an official pass being 50% or Level 1, and the its alignment with, and support for developing twenty-first-

standard level of achievement being 75% or Level 3. I century skills, growth mindsets, habits of mind, and

have chosen to emphasise the standard level of mathematical mindsets. Students feel successful in their

achievement as a beneficial focus for students’ success. learning because of the continuous application, its

See Figure 4 for an example of what this rubric could look authentic and natural integration into mathematics

like on a classroom wall. lessons, and the ease with which students find that their

For the first six weeks of class, I emphasize a improvement of the skills of learning invariably improve

Learning Skill each week. Starting from the top of the their achievement. They see this improvement in

rubric, and each week, moving down to the bottom, we increased attendance, greater content learning and

discuss the Learning Skill and focus on Level 3, self- retention, and improved course marks. Student

assess with it, and learn what it means to embed ownership over their learning becomes natural, and this is

Learning Skills in a metacognitive way while learning a most wonderful feeling as a teacher.

math. For the next two months, I select a different

Learning Skill each week to align with what I have

References

Costa, A.L., & Kallick, B. (Eds.). (2008). Learning and leading

planned pedagogically. Soon students are selecting the with habits of mind; 16 essential characteristics for

Learning Skill for the week, and then by the last third of success. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

the course, we pick Learning Skills as necessary for Cuoco, A., Goldenberg, E.P., & Mark, J. (1996). Habits of

mind: An organizing principle for mathematics curricula.

individual days or periods of time. For the first six weeks,

Journal of Mathematical Behaviour, 15, 375–402.

we are assessing Learning Skills together frequently, but Cuoco, A., Goldenberg, E.P., & Mark, J. (2010). Organizing a

by the middle of the course, we are assessing Learning curriculum around mathematical habits of mind.

Skills about three times a week. Mathematics Teacher, 103(9), 682–689.

Drake, S.M., Reid, J.L., & Kolohon, W. (2014). Interweaving

I have seen students experience great success with curriculum and classroom assessment. Toronto, ON:

this Learning Skills rubric. Students start to use the Oxford Press.

language of the Learning Skills (think learning skills Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success.

New York, NY: Random House.

literacy) and apply it to themselves and their peers (think

Harvard. (1995). Balanced Assessment in Mathematics

assessment for and as learning). For example, at the end Project. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Graduate School of

of one class and during the time needed for the class to Education.

self-assess and write on their tracking sheets, one Jones, F.H., Jones, P., & Jones, J.L. (2000). Tools for

student spoke out loud in class to say that another Teaching. Santa Cruz, CA: Frederick H. Jones &

Associates.

student (and named the student) should get a Level 4 for Mason, J., & Spence, M. (1999). Beyond mere knowledge of

initiative because that student had been going around mathematics: The importance of knowing-to act in the

and helping people. The value of this story is that both moment. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 38,

135–161.

were at-risk students, one much older in age, and both

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2010). Growing Success:

had not expressed much value for school in their previous Assessment, evaluation, and reporting in Ontario schools.

years as a student. (The speaker, unfortunately, dropped Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Retrieved from

out a month later, but the recipient of the praise stayed, www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/policyfunding/success.html

Pyper, J.S. (2005). Making effective use of our time: A tracking

finished this second attempt at the Essentials 10 course,

sheet for daily classroom assessment of student learning.

and then completed the Applied 9 and 10 courses the OAME Gazette, 43(4), 23–30.

next school year. In a personal communication at the end Pyper, J.S., Chin, J., & Reeve, R. (2015). Professional

of the Grade 10 Applied course exam, the student literacies with mathematics, English language arts, and

science teacher candidates. Paper presented at the

attributed this to the use of Learning Skills in his

Canadian Society for the Study of Education (CSSE -

classes—as soon as he started to figure out how to learn, CATE), May 31 – June 3, University of Ottawa, Ottawa,

the math got easier and easier.) ON.

OAME/AOEM GAZETTE SEPT 2015 33

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without

permission.

Вам также может понравиться

- Classroom Vibe: Practical Strategies for a Better Classroom CultureОт EverandClassroom Vibe: Practical Strategies for a Better Classroom CultureРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Teachingphilosophy 3Документ1 страницаTeachingphilosophy 3api-341897530Оценок пока нет

- EDUC 101: Philosophy of Education Final Exam Submitted By: Charis M. Alejo Submitted To: Aida M. Ricarze, PH.DДокумент6 страницEDUC 101: Philosophy of Education Final Exam Submitted By: Charis M. Alejo Submitted To: Aida M. Ricarze, PH.Dcharis m. alejoОценок пока нет

- Elu346 Core AssignmentДокумент15 страницElu346 Core Assignmentapi-737132759Оценок пока нет

- Ued 495-496 Smalley Kelly Classroom and Behavioral Management ArtifactДокумент11 страницUed 495-496 Smalley Kelly Classroom and Behavioral Management Artifactapi-299847728Оценок пока нет

- Module 1 - Angelou BacolodДокумент12 страницModule 1 - Angelou BacolodAngelou BacolodОценок пока нет

- Classroom Management-Session 1Документ18 страницClassroom Management-Session 1Nabaegha NajamОценок пока нет

- Culturally Speaking, October 2016Документ2 страницыCulturally Speaking, October 2016Wilmington University - College of Arts and SciencesОценок пока нет

- What Every Teacher Should KnowДокумент8 страницWhat Every Teacher Should KnowAKОценок пока нет

- Personal Philosophy of TeachingДокумент3 страницыPersonal Philosophy of Teachingapi-297285200Оценок пока нет

- Philosophy of EducationДокумент2 страницыPhilosophy of EducationMARIA MICHELLE A. HELARОценок пока нет

- Assignment in Educ 202 MaedДокумент4 страницыAssignment in Educ 202 MaedEmlyne Nicole Pineda ColotОценок пока нет

- M3L2 PintalДокумент2 страницыM3L2 PintalMaris daveneОценок пока нет

- Gonzales J.C. Educ-8 Week-1Документ5 страницGonzales J.C. Educ-8 Week-1Jomarc Cedrick Gonzales100% (1)

- 3.4 A Constructivist View of TeachingДокумент29 страниц3.4 A Constructivist View of Teachingjmobando1Оценок пока нет

- Prof. Ed 2 Module 6-10Документ8 страницProf. Ed 2 Module 6-10Mhea Kiesherie Alexis BanuagОценок пока нет

- Teaching PhilosophyДокумент2 страницыTeaching Philosophyapi-404627089Оценок пока нет

- A Theoretical Framework 26tdxosДокумент12 страницA Theoretical Framework 26tdxosThis is ScribeОценок пока нет

- Pck105 Prelim ModuleДокумент4 страницыPck105 Prelim ModuleJoy CeОценок пока нет

- CurriculumДокумент19 страницCurriculumIlene Rose BuencochilloОценок пока нет

- Episode 1 What Lies Ahead - Field StudyДокумент8 страницEpisode 1 What Lies Ahead - Field Studygerald declito100% (1)

- Reflection 2 1Документ3 страницыReflection 2 1api-351478197Оценок пока нет

- IVY C.D. Learning LogДокумент6 страницIVY C.D. Learning LogIvy DeoquinoОценок пока нет

- Ball, DДокумент8 страницBall, DMauricio SalazarОценок пока нет

- Conklin 2012 MakingcasecoteachingДокумент5 страницConklin 2012 Makingcasecoteachingapi-436864100Оценок пока нет

- This Study Resource Was: My Own Philosophy of EducationДокумент1 страницаThis Study Resource Was: My Own Philosophy of EducationJulie ParicaОценок пока нет

- Numerasi 2Документ6 страницNumerasi 2Fatikh Inayahtur RahmaОценок пока нет

- Plete PL Playbook Revised060615Документ46 страницPlete PL Playbook Revised060615Rustam KoshelevОценок пока нет

- Read To Lead Resources That Help TeacherДокумент6 страницRead To Lead Resources That Help TeacherMouyad Al-EkhwanОценок пока нет

- Core Assignment - JДокумент12 страницCore Assignment - Japi-608828138Оценок пока нет

- PROF ED 9 UNIT 1 StudentsДокумент12 страницPROF ED 9 UNIT 1 Studentsmelvin procianosОценок пока нет

- Assignment 2-Module 2Документ10 страницAssignment 2-Module 2Juleit AlanОценок пока нет

- Ued496 Bond Ashia Developmentally-Appropriate InstuctionsДокумент5 страницUed496 Bond Ashia Developmentally-Appropriate Instuctionsapi-382327019Оценок пока нет

- The Teacher As A PersonДокумент18 страницThe Teacher As A PersonJean May Pajila CabagayОценок пока нет

- CONSTRUTIVISMДокумент4 страницыCONSTRUTIVISMAlama,Shenna Mea OroscoОценок пока нет

- UntitledДокумент342 страницыUntitledCruz Díez67% (3)

- End-of-Course Reflection Paper/Questionnaire: Adolf O. Odani Flexible LearnerДокумент3 страницыEnd-of-Course Reflection Paper/Questionnaire: Adolf O. Odani Flexible LearnerAdolf OdaniОценок пока нет

- I Am A Holistic Educator, Not A Dancing Monkey: Andrew P. JohnsonДокумент5 страницI Am A Holistic Educator, Not A Dancing Monkey: Andrew P. JohnsonKris Anne Delos SantosОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Issues in Social Studies Ed PDFДокумент12 страницContemporary Issues in Social Studies Ed PDFangiecrazie wellerОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan - Observation 1 - MathДокумент12 страницLesson Plan - Observation 1 - Mathapi-633388485Оценок пока нет

- Ed698framingstatement4planninginstruction VonnnahmeДокумент9 страницEd698framingstatement4planninginstruction Vonnnahmeapi-742989488Оценок пока нет

- Learning Episode 3 - Field Study 2Документ3 страницыLearning Episode 3 - Field Study 2Mary Joy FloresОценок пока нет

- Tales of The UnexpectedДокумент4 страницыTales of The UnexpectedvalerieehartmanОценок пока нет

- On Becoming A Teacher: North Davao CollegesДокумент23 страницыOn Becoming A Teacher: North Davao CollegesJanlenn GepayaОценок пока нет

- Ed 123 EditingДокумент7 страницEd 123 EditingjunainaОценок пока нет

- Rongohia Te HauДокумент3 страницыRongohia Te Hauapi-399088937Оценок пока нет

- Bramley BP 7Документ4 страницыBramley BP 7api-328474438Оценок пока нет

- Joe Tong - 5 Lessons Learned About Teaching Home Economics While NOT Teaching Home EconomicsДокумент3 страницыJoe Tong - 5 Lessons Learned About Teaching Home Economics While NOT Teaching Home Economicstong_j100% (1)

- Episode 9 FS 2Документ2 страницыEpisode 9 FS 2christenfabella21Оценок пока нет

- Educ 904 Jan 14 Class NotesДокумент8 страницEduc 904 Jan 14 Class Notesapi-42688552Оценок пока нет

- The Teacher As A PersonДокумент15 страницThe Teacher As A PersonjjjjjemОценок пока нет

- Philosophy PaperДокумент11 страницPhilosophy Paperapi-363092081Оценок пока нет

- Research Digest 1 - QUIZANO, Christine JaelДокумент3 страницыResearch Digest 1 - QUIZANO, Christine JaelChristine Jael QuizanoОценок пока нет

- What Works?: Research Into PracticeДокумент4 страницыWhat Works?: Research Into PracticeRefrizal AmirОценок пока нет

- J Hemphill WhatДокумент18 страницJ Hemphill Whatapi-445922230Оценок пока нет

- Printable 1Документ11 страницPrintable 1Juan Pablo Aidom NemidОценок пока нет

- Final Reflection SynthesisДокумент7 страницFinal Reflection SynthesisJ DОценок пока нет

- FS1 EP.16-okДокумент11 страницFS1 EP.16-okOKARUОценок пока нет

- Module 2Документ9 страницModule 2Sabrina VeraОценок пока нет

- Assignment 2-Policios, Eden LoveДокумент12 страницAssignment 2-Policios, Eden LoveEden Love Masing PoliciosОценок пока нет

- Slang History LessonДокумент2 страницыSlang History Lessonapi-379080572Оценок пока нет

- Shinu Sam Resume-3Документ1 страницаShinu Sam Resume-3Junaid Mundoden PannipparaОценок пока нет

- Course Outline CHN Lec AdpcnДокумент6 страницCourse Outline CHN Lec AdpcnLinnea May Demoni100% (1)

- SPCH 1321: Business and Professional Communication - Lecture - #14262Документ14 страницSPCH 1321: Business and Professional Communication - Lecture - #14262Derin BusariОценок пока нет

- Manual For Interviewers 2012/13: Admissions Undergraduate Medical Program Michael G. Degroote School of MedicineДокумент14 страницManual For Interviewers 2012/13: Admissions Undergraduate Medical Program Michael G. Degroote School of MedicineAlisonОценок пока нет

- Lesson ExemplarДокумент25 страницLesson ExemplarMelanie Baylon BenitezОценок пока нет

- 4 Handed DentistryДокумент14 страниц4 Handed DentistrySeptifa Dite SadonoОценок пока нет

- Kumpulan Soal-SoalДокумент4 страницыKumpulan Soal-SoalAulia AyuОценок пока нет

- Business ResearchДокумент55 страницBusiness Researchangelufc99Оценок пока нет

- LESSONSTUDY5158 ArticleText 9563 1 10 20210505Документ13 страницLESSONSTUDY5158 ArticleText 9563 1 10 20210505Ike LeeОценок пока нет

- Financial Capability of Public School Teachers in The PhilippinesДокумент40 страницFinancial Capability of Public School Teachers in The PhilippinesVictor SabanganОценок пока нет

- Technology in Teaching and LearningДокумент8 страницTechnology in Teaching and LearningCharm Angel LopezОценок пока нет

- Exam FeeДокумент3 страницыExam FeeMian BialОценок пока нет

- Communication Plan ABRAДокумент4 страницыCommunication Plan ABRAMisha Madeleine GacadОценок пока нет

- Meaning and Growth of Guidance in Nigeria Meaning of GuidanceДокумент100 страницMeaning and Growth of Guidance in Nigeria Meaning of GuidanceMeshach SamuelОценок пока нет

- Orientation: Pre-Immersion - Grade 12Документ3 страницыOrientation: Pre-Immersion - Grade 12Alex Abonales Dumandan100% (3)

- ALADI's Resume PDFДокумент1 страницаALADI's Resume PDFEmmaОценок пока нет

- Flex On Fleek!: Office of Student Affairs & Student ServicesДокумент11 страницFlex On Fleek!: Office of Student Affairs & Student ServicesQuenie CzarinaОценок пока нет

- 084 Marylene N. Tizon PDFДокумент11 страниц084 Marylene N. Tizon PDFKersey BadocdocОценок пока нет

- FlagdaytemplateДокумент3 страницыFlagdaytemplateapi-249069612Оценок пока нет

- RRL & RRS in Importance of OJTДокумент3 страницыRRL & RRS in Importance of OJTMaTheresa HabanaОценок пока нет

- Results Nu BDДокумент1 страницаResults Nu BDRahatОценок пока нет

- An Unforgettable DreamДокумент10 страницAn Unforgettable DreamMeho Ersana Leon Selmanoski90% (10)

- PROF Ed 105: Assessment in Learning 1Документ15 страницPROF Ed 105: Assessment in Learning 1scarsofthemooonnnnОценок пока нет

- Professional EducationДокумент5 страницProfessional EducationJhon Furio100% (2)

- Universities in ChinaДокумент12 страницUniversities in ChinaHussein Ibrahim GebiОценок пока нет

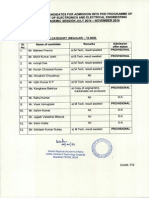

- PHD Eee 2014Документ5 страницPHD Eee 2014sudhirgupta123Оценок пока нет

- 20 Amazing Tips To Pass NEBOSH IGC ExaminationДокумент3 страницы20 Amazing Tips To Pass NEBOSH IGC ExaminationgeologistlakhanОценок пока нет

- HUM1002-Emotional IntelligenceДокумент2 страницыHUM1002-Emotional IntelligenceaccsmarketchannelsОценок пока нет

- Learn To Speak Mandarin Chinese Language BeijingДокумент2 страницыLearn To Speak Mandarin Chinese Language BeijingpetersentxpyjlfbjgОценок пока нет

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionОт EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (2475)

- The Millionaire Fastlane: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeОт EverandThe Millionaire Fastlane: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (2)

- Summary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearОт EverandSummary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (560)

- The Compound Effect by Darren Hardy - Book Summary: Jumpstart Your Income, Your Life, Your SuccessОт EverandThe Compound Effect by Darren Hardy - Book Summary: Jumpstart Your Income, Your Life, Your SuccessРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (456)

- Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeОт EverandIndistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (5)

- No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelОт EverandNo Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (4)

- The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverОт EverandThe Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (186)

- Eat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeОт EverandEat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (3226)

- The One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsОт EverandThe One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (709)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeОт EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeРейтинг: 2 из 5 звезд2/5 (1)

- The 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageОт EverandThe 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (9)

- Summary: The 5AM Club: Own Your Morning. Elevate Your Life. by Robin Sharma: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandSummary: The 5AM Club: Own Your Morning. Elevate Your Life. by Robin Sharma: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (22)

- Growth Mindset: 7 Secrets to Destroy Your Fixed Mindset and Tap into Your Psychology of Success with Self Discipline, Emotional Intelligence and Self ConfidenceОт EverandGrowth Mindset: 7 Secrets to Destroy Your Fixed Mindset and Tap into Your Psychology of Success with Self Discipline, Emotional Intelligence and Self ConfidenceРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (561)

- Napoleon Hill's Keys to Positive Thinking: 10 Steps to Health, Wealth, and SuccessОт EverandNapoleon Hill's Keys to Positive Thinking: 10 Steps to Health, Wealth, and SuccessРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (306)

- Uptime: A Practical Guide to Personal Productivity and WellbeingОт EverandUptime: A Practical Guide to Personal Productivity and WellbeingОценок пока нет

- Own Your Past Change Your Future: A Not-So-Complicated Approach to Relationships, Mental Health & WellnessОт EverandOwn Your Past Change Your Future: A Not-So-Complicated Approach to Relationships, Mental Health & WellnessРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (85)

- Quantum Success: 7 Essential Laws for a Thriving, Joyful, and Prosperous Relationship with Work and MoneyОт EverandQuantum Success: 7 Essential Laws for a Thriving, Joyful, and Prosperous Relationship with Work and MoneyРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (38)

- What's Best Next: How the Gospel Transforms the Way You Get Things DoneОт EverandWhat's Best Next: How the Gospel Transforms the Way You Get Things DoneРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (33)

- Mastering Productivity: Everything You Need to Know About Habit FormationОт EverandMastering Productivity: Everything You Need to Know About Habit FormationРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (23)

- Fascinate: How to Make Your Brand Impossible to ResistОт EverandFascinate: How to Make Your Brand Impossible to ResistРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Leadership and Self-Deception: Getting out of the BoxОт EverandLeadership and Self-Deception: Getting out of the BoxРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (156)

- Think Faster, Talk Smarter: How to Speak Successfully When You're Put on the SpotОт EverandThink Faster, Talk Smarter: How to Speak Successfully When You're Put on the SpotРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Summary: The Gap and the Gain: The High Achievers' Guide to Happiness, Confidence, and Success by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandSummary: The Gap and the Gain: The High Achievers' Guide to Happiness, Confidence, and Success by Dan Sullivan and Dr. Benjamin Hardy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (4)

- Summary of The 48 Laws of Power by Robert GreeneОт EverandSummary of The 48 Laws of Power by Robert GreeneРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (36)

- Summary of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change by Stephen R. CoveyОт EverandSummary of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change by Stephen R. CoveyРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (41)