Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Funnel Cities and Towns On Feet? How To Live With The Visionary Architecture of Walter Jonas and Archigram

Загружено:

Andrea FacchettiОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Funnel Cities and Towns On Feet? How To Live With The Visionary Architecture of Walter Jonas and Archigram

Загружено:

Andrea FacchettiАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Jonathon Keats, Contributor

I comment on art exhibitions around the world.

11/27/2012 @ 9:46AM | 1,776 views

Funnel Cities And Towns On

Feet? How To Live With The

Visionary Architecture Of Walter

Jonas And Archigram

In the early 1970s,

West Germany

planned to build cities

shaped like funnels.

Designed by a Swiss-

German painter named

Walter Jonas, they

looked rational enough

in plans and models.

Seven hundred

housing units were

stacked in concentric

circles. Beneath them

were rings of shops,

with supporting infrastructure embedded in the center. Jonas believed that the

inward orientation of his Intrapolis would make people more community-

focused, and he argued that his cities’ minimal contact with the ground would

save valuable soil. The West German Ministry of Construction agreed, and was

held back only by lack of funding. Thus was Jonas’ spectacular vision saved

from the ignominious fate of actually getting built.

Though certainly unique, the Intrapolis project is far from alone in the class of

architecture better left on paper. The best of these unbuilt buildings and

undeveloped developments – some of which can currently be seen at Berlin’s

Hamburger Bahnhof – can have as much impact on society as concrete

skyscrapers and cities, but by opposite means. Whereas ordinary architecture

literally shapes the way in which we live, unrealized plans and models provide

infrastructure for our collective imagination. They are meeting places for

conversation.

If built architecture must be judged by practical criteria – such as whether it

leaks or drives people crazy – speculative architecture should be valued for its

outrageous impracticality. Jonas’s Intrapolis is fascinating for what it reveals

about our conventional way of making cities, where skyscrapers are erected

higher and higher to hold more and more people in bunkered units, and to give

the most privileged tenants a view unobstructed by overdevelopment. (The

others have TV for their viewing pleasure.) Jonas’s funnels question the

assumption that urban residences ought to be refuges from the cities in which

we live, and encourage us to consider more holistic options. The Intrapolis

captivates us precisely because it’s so bizarrely different from anything in our

experience. It belongs to an alternate reality that we can visit to escape the

built-in assumptions of our everyday environment.

The British art collective Archigram explored even more extreme alternatives.

Uninhibited by the urge to build what they designed, they proposed dozens of

outlandish ideas between 1961 and 1974. One of the most famous was the

Plug-In City, schemed by group member Peter Cook in 1964. The Plug-In City

rejected the assumption that buildings be fixed in place, instead envisioning a

permanent scaffolding supporting moveable living units. No longer were you

doomed to endure your neighbors. You could pick up your pod – using one of

several communal cranes – and plug into the common infrastructure

anywhere you wanted. The Plug-In City had the vibrant social dynamic of a

cocktail party.

The Walking City envisioned by Archigram’s Ron Herron in the same year

addressed a different issue: What happens when a city is no longer situated in

a region where the populace wants to live? Unlike ordinary towns, Herron’s

metropolis didn’t have to be abandoned since it had its own set of legs. The

physical impossibility was beside the point. Herron’s plan rejected the

standard notion that a city is a location, instead construing it as a

superorganism.

In a sense, speculative architecture is akin to science fiction. A story by Philip

K. Dick or a movie by Ridley Scott sets out a parallel universe that exposes our

narrow-mindedness by either mirroring our prejudices or revealing alternate

worldviews. Yet there are also crucial differences between sci-fi and the paper

architecture of Archigram (or masters such as the Italian Futurist Antonio

Sant’Elia and the American visionary Lebbeus Woods). Whereas science

fiction is a narrative, with a single track from start to finish, architectural plans

and models are open-ended. They can be explored every which way. They have

unlimited capacity for collective fantasy, and the looming potential – or threat

– of actually being implemented. Hypothetical architecture is perilous.

Archigram was fortunate never to have their dreams brought down to earth.

(Their only brick-and-mortar legacy is a playground in Buckinghamshire and a

swimming pool made for Rod Stewart.) Walter Jonas’s dream was too costly.

Other visionaries were not so lucky.

In the same years that the Intrapolis was taken up by

the Ministry of Construction, a German architect

named Georg Heinrichs had another brilliant idea:

Since highways were the future, why not build linear

cities above the traffic? The Berlin Senate approved the

provocative concept in 1971, and for the following

decade workers labored to build a third-of-a-mile-long

apartment complex straddling the Autobahn. As might

be expected, the philosophical dimensions of the

project – such as the idea that cities might flow like rivers – were steamrolled

and buried in concrete. By the time the megastructure reached completion in

1980, Berlin mayor Richard von Weizsäcker was comparing it to a curse by the

Devil himself.

The Autobahnüberbauung Schlangenbader Straße is still intact, and it has

come to have a sort of philosophical function in urban planning. It’s now a

textbook example of what to avoid at all cost.

Update: Read an insightful response to this article by ArtInfo architecture and

design writer Kelly Chan.

Follow Jonathon Keats on Twitter… and hear about some of his own

speculative architecture, and see one of the blueprints here.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Boetzkes - TECHNIQUES OF SURVIVAL - THE HARRISONS AND THE ENVIRONMENTAL COUNTERCULTUREДокумент19 страницBoetzkes - TECHNIQUES OF SURVIVAL - THE HARRISONS AND THE ENVIRONMENTAL COUNTERCULTUREAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Flusser Vilem 1995 Three Essays and An IntroductionДокумент12 страницFlusser Vilem 1995 Three Essays and An IntroductionAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Superstudio and The Architecture of Mass CultureДокумент18 страницSuperstudio and The Architecture of Mass CultureJulietteОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Azzarito - LIBRE, COLORADO, AND THE HAND-BUILT HOMEДокумент17 страницAzzarito - LIBRE, COLORADO, AND THE HAND-BUILT HOMEAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Kindynis, T. 2014. Ripping Up The MapДокумент26 страницKindynis, T. 2014. Ripping Up The MapAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- Marina Vishmidt - Speculation As A Mode of Production - Forms of Value Subjectivity in Art and Capital (2019)Документ267 страницMarina Vishmidt - Speculation As A Mode of Production - Forms of Value Subjectivity in Art and Capital (2019)Andrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Reinventing The Art SchoolДокумент112 страницReinventing The Art SchoolAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Andrea Facchetti - Towards A Political Dimension of Speculative DesignДокумент16 страницAndrea Facchetti - Towards A Political Dimension of Speculative DesignAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

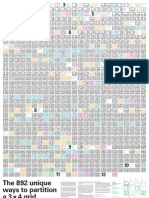

- 3x4variations PosterДокумент1 страница3x4variations PosterpelicantropusОценок пока нет

- Anne Balsamo Design PDFДокумент10 страницAnne Balsamo Design PDFAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Anne Balsamo - DesignДокумент10 страницAnne Balsamo - DesignAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- Garamond Premier Pro ReadmeДокумент4 страницыGaramond Premier Pro Readmetarambaina7901Оценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- How To Build A Universe That Doesn T Fall Apart Two Days LaterДокумент14 страницHow To Build A Universe That Doesn T Fall Apart Two Days LaterMilica AmidzicОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Eye Magazine - What Is This Thing Called Graphic Design CriticismДокумент5 страницEye Magazine - What Is This Thing Called Graphic Design CriticismAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Antonelli e Hunt - Design and Violence-PreviewДокумент27 страницAntonelli e Hunt - Design and Violence-PreviewAndrea Facchetti100% (1)

- Ur CollageДокумент2 страницыUr CollageAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Design CultureДокумент13 страницDesign CultureJuliana GarcíaОценок пока нет

- The Archivist and The ExplorerДокумент8 страницThe Archivist and The ExplorerAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- All Problems of Notation Will Be Solved by The Masses - MuteДокумент8 страницAll Problems of Notation Will Be Solved by The Masses - MuteAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- All Problems of Notation Will Be Solved by The Masses - MuteДокумент8 страницAll Problems of Notation Will Be Solved by The Masses - MuteAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- Boyle and Haggarty, Spectacular SecurityДокумент18 страницBoyle and Haggarty, Spectacular SecurityAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Archivist and The ExplorerДокумент8 страницThe Archivist and The ExplorerAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- Walter Benjamin - Haussmann or The BarricadesДокумент2 страницыWalter Benjamin - Haussmann or The BarricadesAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- Walter Benjamin - Haussmann or The BarricadesДокумент2 страницыWalter Benjamin - Haussmann or The BarricadesAndrea FacchettiОценок пока нет

- COMMONWEALTH ACT No 473Документ5 страницCOMMONWEALTH ACT No 473Ramon GarciaОценок пока нет

- Effects of Globalization On Education in Africa 1983-2008: Faculty of Education University of Port Harcourt, NigeriaДокумент8 страницEffects of Globalization On Education in Africa 1983-2008: Faculty of Education University of Port Harcourt, NigeriaBurak SabunОценок пока нет

- Fentimans Plan To Launch Brewed Soft Drinks Into The Japanese Market.Документ12 страницFentimans Plan To Launch Brewed Soft Drinks Into The Japanese Market.PhanhОценок пока нет

- Consumer Reaction Towards E-Marketing - A Case Study in Guwahati City, AssamДокумент19 страницConsumer Reaction Towards E-Marketing - A Case Study in Guwahati City, Assamquỳnh nhưОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- The Practice of Investor RelationsДокумент14 страницThe Practice of Investor RelationsLang Mensilang100% (1)

- Toyota Mark StandartsДокумент42 страницыToyota Mark StandartsArcОценок пока нет

- Revolutionary Nationalist MovementsДокумент2 страницыRevolutionary Nationalist Movementsmuralli_201095Оценок пока нет

- Management 595 - Fall 2019 Exam 1 Study Guide: A. Essay QuestionsДокумент8 страницManagement 595 - Fall 2019 Exam 1 Study Guide: A. Essay QuestionsmeghanОценок пока нет

- Retail Management Word Search PuzzleДокумент1 страницаRetail Management Word Search PuzzleSitiSuharijanSaidОценок пока нет

- Reducing Rice Postharvest LossesДокумент2 страницыReducing Rice Postharvest LossesTrina Leah MendozaОценок пока нет

- Gaia Education - Ecovillage Design CurriculumДокумент116 страницGaia Education - Ecovillage Design CurriculumDaisyОценок пока нет

- Equity Semester 2 2018: Doctrinal AnalysisДокумент4 страницыEquity Semester 2 2018: Doctrinal AnalysisLeoОценок пока нет

- Soal 1Документ7 страницSoal 1GABRIELAW ANGELIKAОценок пока нет

- Sanders & Sanders. (2004) - Spatial Urban Dynamics PDFДокумент33 страницыSanders & Sanders. (2004) - Spatial Urban Dynamics PDFJuan EscobarОценок пока нет

- Business Law Complete Handout - 2017-1Документ226 страницBusiness Law Complete Handout - 2017-1Ronald MulleyОценок пока нет

- Confessions of A ModeratorДокумент16 страницConfessions of A ModeratorTom EwingОценок пока нет

- Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad: (Department of Mass Communication)Документ2 страницыAllama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad: (Department of Mass Communication)Muhammad ArshmidusОценок пока нет

- Principle For Teaching SpeakingДокумент1 страницаPrinciple For Teaching SpeakingismaaОценок пока нет

- Final Datesheet Final YearДокумент16 страницFinal Datesheet Final YearHarsh TyagiОценок пока нет

- Jean Bodin - Report 061914Документ8 страницJean Bodin - Report 061914Christian Ian LimОценок пока нет

- Flight Management Computer System FMC Update 13.0 Reference GuideДокумент558 страницFlight Management Computer System FMC Update 13.0 Reference GuideSHIJKОценок пока нет

- LIMUN Masterclass: How Mun WorksДокумент27 страницLIMUN Masterclass: How Mun Worksahmad wajeehОценок пока нет

- Network For Social Computing ResearchДокумент30 страницNetwork For Social Computing ResearchUNITED NATIONS PAYMENT APPROVALS.Оценок пока нет

- 705817730177th Vienna International Music CompetitionДокумент4 страницы705817730177th Vienna International Music CompetitionRocco CataniaОценок пока нет

- DLP ScienceДокумент2 страницыDLP ScienceCarlo Yambao100% (1)

- Answer Sheet q1 Week 4Документ4 страницыAnswer Sheet q1 Week 4Ma Corazon Sagun CaberОценок пока нет

- BlackBerry Workspaces DatasheetДокумент6 страницBlackBerry Workspaces DatasheetPrasad KshirsagarОценок пока нет

- Skill Development Programme: Presented byДокумент12 страницSkill Development Programme: Presented byamit chavariaОценок пока нет

- SAR100 GSAR Manual Del Usuario PDFДокумент302 страницыSAR100 GSAR Manual Del Usuario PDFJohn Fernando Bueno CorredorОценок пока нет

- Letters, Memo, and E-MailsДокумент4 страницыLetters, Memo, and E-MailsMarielle PanolleraОценок пока нет

- The Compound Effect by Darren Hardy - Book Summary: Jumpstart Your Income, Your Life, Your SuccessОт EverandThe Compound Effect by Darren Hardy - Book Summary: Jumpstart Your Income, Your Life, Your SuccessРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (456)

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesОт EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1635)

- Can't Hurt Me by David Goggins - Book Summary: Master Your Mind and Defy the OddsОт EverandCan't Hurt Me by David Goggins - Book Summary: Master Your Mind and Defy the OddsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (383)

- Summary of 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to ChaosОт EverandSummary of 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to ChaosРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (294)

- Summary of The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental IllnessОт EverandSummary of The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental IllnessОценок пока нет