Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

7550 16865 1 PB PDF

Загружено:

Adam JohnsonОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

7550 16865 1 PB PDF

Загружено:

Adam JohnsonАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Makara J. Health Res.

, 2017, 21(3): 93-98

doi: 10.7454/msk.v21i3.7550

Socio-Economics of Childhood Pulmonary Tuberculosis with Adult Tuberculosis

Household Contacts in Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta Province

Al Asyary1*, Purnawan Junadi2, Purwantyastuti3, Tris Eryando 4

1. Postgraduated School of Public Health Sciences, Universitas Muhammadiyah Prof Dr Hamka, Jakarta 12790, Indonesia

2. Departement of Health Administartion and Policy, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia,

Depok 16424, Indonesia

3. Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta 10430, Indonesia

4. Departement of Biostatistics and Population Studies, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia,

Depok 16424, Indonesia

*E-mail: al_asyary@uhamka.ac.id

Abstract

Background: Since the tuberculosis (TB) disease in children constitutes a global health problem that has long been

neglected, this study sought to predict socioeconomic factors as public-health determinants that could protect children

who were exposed to TB in their household. Method: A case-control study of 132 children (under 14 years old) who

shared their household with adults suffering from pulmonary TB was conducted in the Province of Daerah Istimewa

Yogyakarta. This study consisted of an interview and anthropometry measurement for the controls screening test, while

the cases were monitored by pediatricians with a scoring system childhood TB diagnosis from the secondary hospital

database. A multiple logistic regression was used to analyze the results. Results: A healthy housing condition, predicted

by a naturally illuminated luminary bedroom prevented the incidence of the childhood TB disease (p = 0.043) even if

exposed to adult TB in their environment (p = 0.775). Conclusions: Healthy housing factors with good sunlight

protected children especially at the early stage, when there were active pulmonary TB adult household contacts.

Ventilation and morning sunlight facilitated air circulation, vitality and the body’s immune system towards TB

protection.

Keywords: socio-economic, children, tuberculosis, household contact

Introduction children who have contact with a pulmonary TB adult

in the same house develop TB.4 Several factors were

Pulmonary TB transmission in children is impacted by expected to influence this risk or to prevent children

contact with adult pulmonary TB. Children are not the from developing pulmonary TB when in contact with

causal subjects who transmit the disease to the population. an adult pulmonary TB patient who lives in the same

Contact was the main source of the transmission of house. This study aimed to assess the socio-economic

adult pulmonary TB to childhood pulmonary TB. 1 factors that may reduce the risk of childhood pulmonary

Adults who had positive acid-resistant Mycobacterium TB incidence in children who share a house with adult

TB bacille (Basil Tahan Asam – BTA) were vulnerable pulmonary TB patients.

to transmitting the disease to children, especially if

contact occurred intensively in the same house. 2 In Methods

global prevention efforts, chemopropylaxis has been

performed for children with a family history of TB to Data collection differed between the case group and the

prevent TB infection, particularly in children who were control group. However, this difference was necessary

already infected in order to reverse the development of to prevent selection bias. A case was defined as a clear

pulmonary TB illness.3 diagnosis of positive childhood TB status impacted by

an adult pulmonary TB patient in a shared house. The

Childhood pulmonary TB is often ignored and is also cases were collected from eight referred hospital

difficult to diagnose well.4 It often occurrs because databases of patients who sought treatment (passive

there was contact with an adult pulmonary TB patient. case finding). The comparison sample of those without

This transmission risk increases when the children live childhood TB living in the same house as an adult

in same house as a TB patient.1 However, not all pulmonary TB was collected in the same settings as the

93 December 2017 | Vol. 21 | No. 3

94 Al-Asyary, et al.

Collected data from medical records of pediatric

poly in eight referral hospitals for childhood

pulmonary tuberculosis in DIY province

Examined the medical records for children with pulmonary tuberculosis

diagnoses who had contact with adult pulmonary tuberculosis patients*

Present

Visited the address to identify adult tuberculosis

patients that lived in the same house

Present

Identified illness episodes related to the contacts under

investigation/tracing**1

Obtained case group

*Point 1 The parameter of childhood pulmonary tuberculosis scoring system

**Obtained information on pulmonary tuberculosis illness episodes (inclusion: ever

had/have positive BTA recorded/diagnosed in a health facility)

Figure 1. Tracing of Case Group

found cases (active case finding). Figure 1 shows that into meeting health conditions and not meeting health

childhood TB status in a hospital setting was traced to conditions. The bedrooms, kitchens, and living rooms

adult pulmonary TB patients who lived in shared were assessed by separate utilization, cleanliness,

houses. Adult TB sufferers were identified by a clearly existence and use of window, ventilation, and natural

diagnosed history by health professionals and a period illumination by sunlight.

of possible TB transmission.5 Adult TB patients in this

study had been recorded and treated (for children Economic status was derived from Principal

under five) or already recovered (for children 5-14 Component Analysis (PCA) which was generated by

years old); these patients were traced as possible index of household goods belonging.7 This study

causes of childhood TB status. This is because identified and calculated twelve household goods

children above 5-years old could suffer pulmonary TB whether exist or not in every household. PCA analysis

after a year of primary infection from an adult have formed four indexes that range from the poorest

pulmonary TB patient, while children under five only to highest level of economic status. Meanwhile,

need a shorter time of several weeks.3,5,6 education level was calculated by higher school to

university degree for high education category, while

Since children without TB are not reported, a control below of it have identified as low education level.

from adult TB household contacts was created by Density was measured by WHO definition for children

screening results on adult pulmonary TB patients in density. Previous studies have specifically estimated

health center medical records (Puskesmas) in the same the best housing density for children (0-14 years old),

population settings in which cases were found (Figure that was adopted by the WHO (1993), as 3 m 2/room.8

2). In this study, housing condition was calculated We measured the housing density in the past before

(scored) from an aggregate index of house conditions the adult developed by TB. It evaluated 12 months to

according to Act of the Ministry of Health, Republic 6 months before the adult have confirmed TB by

of Indonesia Num. 829/Menkes/SK/VII/1999 that was health professionals (regarded to TB mechanisme

renewed by Ditjen PPM (2002). The housing of adult where in children, it happens faster or less than 6

pulmonary TB sufferers with children was categorized months after infection).9,10

Makara J. Health Res. December 2017 | Vol. 21 | No. 3

Socio-Economics of Childhood Pulmonary Tuberculosis 95

Collected medical record data in pulmonary poly in

Puskesmas for cases found in DIY province

Visited an address to identify the presence of

children <14 years old

Present*

Identified the status of childhood pulmonary tuberculosis by screening of

contact investigation/tracing** 1, 3

Non-suspect (health) Suspect

Obtained control Referred to health

group Suffers TB** facility***

*If there was more than one child, then all children were screened to see the results

**Screening results were suspect if there were one or more of 3 children meeting

pulmonary tuberculosis criterion: (cough, fever, and growth failure)

***The suspected children were referred to the Public Health Center to establish a

diagnose, but this was not involved in the study

Figure 2. Tracing of Control Group

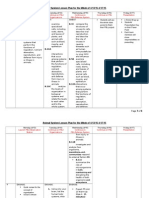

Table 1. Socio-economic Status of Childhood TB with Adult TB Household Contacts

Cases (n=66) Controls (n=66) Total (n=132)

N % N % n %

Economic status

Poor 15 22.7 11 16.7 26 19.7

Middle 23 34.8 30 45.5 53 40.2

Middle upper 16 24.2 10 15.2 26 19.7

High 12 18.2 15 22.7 27 20.5

Education level of adult TB

Low 37 56.1 39 59.1 76 57.6

High 29 43.9 27 40.9 56 42.4

Occupation type of adult TB

motherhood/un-worker 9 13.6 14 21.2 23 17.4

Unemployed worker 44 66.7 44 66.7 88 66.7

Employee 13 19.7 8 12.1 21 15.9

Housing condition

Unmet condition 33 50 28 46.4 61 46.2

Met condition 33 50 38 57.6 71 53.8

Natural illumination of bedroom (sunlight)

Poor 33 50 18 27.3 51 38.6

Sufficient 33 50 48 72.7 81 61.4

Housing density

Crowded 7 10.6 19 28.8 26 19.7

Un-crowded 59 89.4 47 71.2 106 80.3

Makara J. Health Res. December 2017 | Vol. 21 | No. 3

96 Al-Asyary, et al.

Table 2. Multivariate Analysis of Childhood TB with Adult TB Household Contacts

Bivariable analysis Multivariable analysis

Category

Crude OR 95% CI p Adjusted OR 95% CI p

Socioeconomic status

Low Referral Referral 0.568 Referral Referral 0.267

Mid 1.648 0.639-4.250 0.302 0.618 0.113-3.360 0.577

High 1.000 0.333-3.005 1.000 0.349 0.050-2.433 0.288

Highest 1.705 0.575-5.055 0.336 2.545 0.359-18.024 0.350

Bed room illumination

Not sufficient Referral Referral 0.008 Referral Referral 0.043*

Sufficient 2.667 1.291-5.508 5.530 1.057-28.921

Housing density

Dense Referral Referral 0.011 Referral Referral 0.775

Not dense 0.293 0.114-0.757 0.754 0.109-5.226

The enter method of multiple logistic regression was Discussion

used to predict the protective factors of childhood TB

status for children living in the same house as an adult Socio-economic reasons have been explored to eva-

TB sufferer. This method involved entering all variables luate the impact of TB in developing countries4,15-17,

that passed a screening test (p < 0.25 and substantial). especially in Indonesia.18,19 This study confirmed that

Variables were excluded one by one starting from the the economic status and housing density are the indirect

greatest p value to the smallest p value until reaching variables which can predict childhood TB, when the

the desired significance (p < 0.05). Changes in the Odd children live in adult TB-inflicted households (Table 2).

Ratio (OR) that were not allowed (higher than 10% in However, this research revealed that a well-illuminated

each predictor variables) were also considered.11 bedroom status can significantly reduce the transmission

risk of childhood TB, as a predictor variable.

Possible confounders were identified in order to

maintain comparability between the case and control Housing condition. Persistent correlations between poor

group. Confounding was treated as an independent housing conditions and poor health levels have already

variable, as it influenced related factors. Information been reported by cross-sectional studies which recom-

bias, such as non-differential misclassification, was mended the betterment of housing conditions as well as

controlled by using a valid and reliable data collecting improved health conditions.20 However, the complex

tool that was modified from a previous study correlations removed the condition that confounding

questionnaire.5,10,12-14 Informed consent from the variables, such as economic status, could be considered

respondent was obtained in written form. Ethic approval strong enough to be justified. In other words, the

of the study was obtained from the Expert Commission increase in healthy housing conditions was also not a

on Research and Research Ethics, Faculty of Public certain cause of increasing the degree of health. The

Health, Universitas Indonesia (87/H2.F10/ correlation patterns that were obtained by controlling

PPM.00.02/2014). the other variables answer the question that housing

condition consists of three components: physical,

Results sanitation, and behavioral components. Good housing

condition is a protective factor to prevent active

Table 1 shows that socioeconomic status distribution, pulmonary TB transmission. Housing health protects

while Table 2 presents multivariate analysis of this children from not only communicable diseases, such as

study.In this study, Nearest Neighbor Analysis was pulmonary TB, but also from injury. It also aids their

performed with CrimeStat III with 132 coordinate development, nutrition status, and mental health. 21,22

points. The results show that the cases’ patterns were

clustered, with statistic test values of Z = -12.4961 and In general, this study found that housing conditions are

p = 0.0001. Urban setting in developing countries are unable to protect children who live in the same house

more likely to be composed of insufficient land for a with an infected adult, from pulmonary TB

huge population, which gives rise to unresolvable transmission. However, it may be possible to describe

problems related to communicable diseases, particularly it by the available composite variable. Bed room

Tuberculosis (TB). The NNI showed a concentrated illumination explained that housing condition of

cluttering pattern (0.43147). The location of the childhood TB status who live in same house with adult

concentrated groups was the Yogyakarta City area. pulmonary TB suffer (OR = 2.667 Oradj = 5.530)

This study concluded that TB transmission is not (Table 2). Bedroom is always main room that existed in

always related only to housing density, but also to the each house. It had longest proportion for activities both

local environment and the transmission of TB. when take a rest (sleep) (about 8 hours per day) and

Makara J. Health Res. December 2017 | Vol. 21 | No. 3

Socio-Economics of Childhood Pulmonary Tuberculosis 97

sedentary activities. Average 90% of people spend their As natural of TB disease in children, it have been

time indoor, wherein 50-70% in house and 30% in bed confirmed from previous studies that childhood TB can

room. At least 1/3 of time was spend in this room.22 In not transmitted their TB infection to another either for

children especially infant, underfive and preschool the other child (siblings, etc) or adult. 4,9 This is because

children, spend more time (>12 hours per day) for children with TB can not cough, so they are not

activities; such as playing, having creation, and take transmitted the MTB bacil by air-borne, and its

rest23 whether was alone or accompanied by adult. diagnosis should be confirmed by scoring system. 28,29

In this study, childhood TB should not the response but

Bedrooms, especially those for children, did not only it is the effect of housing density in particularly to let

influence the transmission of pulmonary TB but also them exposed by the adult TB patients. However, this

the physical and even psychological state of the study can not present the exposure level or length of

children.23 Moreover, the usage of the bedroom based stay between adult TB patients with their household

on age showed that this was different for children children. This factors is essential for further research to

under five compared to 5-year-olds and older children. recommend

Infants between 0 and 18 months were still depending

on their parents, especially on their mother, in the post However, further analysis was performed in order to

delivery period. Whereas 2-5-year-olds engaged in assess housing density probability. The population

very active activities but still remained close to their environment cannot be ignored in housing factors as

parents. The provision of the room starting with used social determinants of health. These characteristics had

furniture, scale and measure, color and style, and already been implemented in investigations of public

illumination, impacts the health of the child/infant. health epidemiology, especially for correlations with

Natural illumination for the infant was very important communicable diseases.6 This factor was grouped into

had to be provided with consideration to the eye and three sub-sections: area characteristic, internal

skin sensitivity of the infant. Illumination should avoid condition, and type of housing. Area characteristics

direct exposure to sunlight and should reduce the influenced the health in many ways30, such as spatial

intensity thereof.24 However, this study was not analysis.

conducted in order to look at subgroups of different

age. Thus, further research is necessary in this direction. Group clustering in the study population aimed to

reveal whether adult pulmonary TB sufferers who

Sunlight contains ultraviolet (UV) radiations capable of shared a house with child TB patients had clustered or

stimulating vitamin D. Vitamin D works in the body by random distribution patterns. This was revealed using

increasing the immunity to pulmonary TB, accelerating the nearest neighbor index (NNI). This index showed

primary anti-TB drug (first line anti-TB drug – OAT) the degree of spatial distribution based on the distance

treatment and slowing the reactivation of the between minimum coordinates or minimum distances

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) in the secondary between coordinates of the closest cases. Smaller or

infection. In fact, sunlight can reduce the transmission near null NNIs indicated either small distances between

of TB in a household environment.25 Indirectly sunlight point coordinates or a clustered distribution pattern.

exposure also eliminated MTB. NNI = 1 indicated a random distribution pattern and an

NNI greater than 1 indicated a uniform distribution

Historically, before anti-TB drugs were introduced, the pattern.6

treatment of pulmonary TB was performed by sunlight

therapy named heliotherapy. Pulmonary TB sufferers Conclusions

were placed in sanatoriums after considering their

nutrition status. The results of therapy after more than 6 Socioeconomic status, especially high economic status,

months were obtained for up to 50% of pulmonary TB indirectly promoted children’s health. However, it was

sufferer who did not show clinical symptoms before not only population density in the house that needed to

their first TB stage.26,27 be considered, as the residences’ environments also

played important roles in protecting children from

Housing density. The results of statistical analysis on pulmonary TB disease when they lived in the same

population density showed a p < 0.005 with OR < 1. house as an adult pulmonary TB patient. Housing

This means that a low density level helped prevent condition, especially bedroom illumination, was a

childhood TB in children with adult TB household protective factor that could be influenced by

contacts. Conversely, children who lived in crowded intervention. Sunlight and ventilation prevented children

houses were more vulnerable to infection by commu- from developing pulmonary TB, as these promote

nicable diseases such as pulmonary TB. This can also children’s immune systems and vitality. Other reversible

cause psychological stress among children who are or easily-intervented factors for certain population

influenced by aggressivity that results in the physical settings need to be understood. Also, continuity in active

abuse of weaker children.5 case finding (e.g., contact tracing) is very important,

Makara J. Health Res. December 2017 | Vol. 21 | No. 3

98 Al-Asyary, et al.

particularly with respect to TB resistance, which is a income countries. Geneva: World Health Organizations;

danger not only for adults but also for children, who 2012.

are not only vulnerable but also in greater danger of 14. WHO. Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes

mortality. on the management of tuberculosis in children. 2006. p.

1205-11.

15. Asyary A, Purwantyastuti, Eryando T, Junadi P.

Conflict of Interest Statement Perceived of healthcare utilization by adult pulmonary

tuberculosis patients for their children in Yogyakarta.

None declared. Asian J Epidemiol. 2017;10:70-5.

16. Paramasivan CN, Lee E, Kao K, Mareka M, Kubendiran

Acknowledgements G, Kumar T a, et al. Experience establishing tuberculosis

laboratory capacity in a developing country setting. Int J

The study was performed by the aid from various Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:59-64.

parties: All staff and personel of Health Office of the 17. Harling G, Ehrlich R, Myer L. The social epidemiology

of tuberculosis in South Africa: A multilevel analysis.

Province/Regency – Municipality in DIY province. We Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:492-505.

also thanks to contributors: Prof Sudijanto Kamso, Prof 18. Pisani E, Olivier Kok M, Nugroho K. Indonesia’s road to

Bambang Supriyatno, Dr Artha Budi Susila Duarsa, universal health coverage: a political journey. Health

and Yodi Mahendradhata, MD, MSc, PhD. Policy Plan. 2016:1-10.

19. Lestari T, Probandari A, Hurtig AK, Utarini A. High

References caseload of childhood tuberculosis in hospitals on Java

Island, Indonesia: a cross sectional study. BMC Public

1. Esposito S, Tagliabue C, Bosis S. Tuberculosis in Health. 2011;11:784.

children. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2013;5: 20. Yogo M. Portfolio choice in retirement: Health risk and

e2013064. the demand for annuities, housing, and risky assets. J

2. Zelner JL, Murray MB, Becerra MC, Galea J, Lecca L, Monet Econ. 2016;80:17-34.

Calderon R, et al. Bacillus calmette-guerin and isoniazid 21. Allen J, Balfour R, Bell R, Marmot M. Social

preventive therapy protect contacts of tuberculosis determinants of mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry.

patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:853-9. 2014;26:392-407.

3. Marais BJ, Pai M. New approaches and emerging 22. Novoa AM, Ward J, Malmusi D, Díaz F, Darnell M,

technologies in the diagnosis of childhood tuberculosis. Trilla C, et al. How substandard dwellings and housing

Paediatr Respir Rev. 2007;8:124-33. affordability problems are associated with poor health in

4. Asyary A. Childhood tuberculosis: a neglected paradigm a vulnerable population during the economic recession of

in developing countries. Public Heal Indones. 2017;3:7-10. the late 2000s. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14:120.

5. Muruka C, Muruka A. Guidelines for environmental 23. Newman SJ, Holupka CS. Housing affordability and

health management in children’s homes in sub-Sahara investments in children. J Hous Econ. 2014;24:89-100.

Africa. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2007;4:319-31. 24. Sandjaya I. Kamar Anak dan Remaja. Jakarta: Gramedia;

6. Lai P-C, So F-M, Chan K-W. Spatial epidemiological 1997. [In Indonesian]

approaches in disease mapping and analysis. New York: 25. Wingfield T, Schumacher SG, Sandhu G, Tovar MA,

CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group; 2009. Zevallos K, Baldwin MR, et al. The seasonality of

7. Jackson EF, Siddiqui A, Gutierrez H, Kanté AM, Austin tuberculosis, sunlight, vitamin D, and household

J, Phillips JF. Estimation of indices of health service crowding. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:774-83.

readiness with a principal component analysis of the 26. de Castro Fernandes FM, de Souza Martins E, Pedrosa

Tanzania Service Provision Assessment Survey. BMC DMAS, Evangelista M do SN. Relationship between

Health Serv Res. 2015;15:536. climatic factors and air quality with tuberculosis in the

8. Helwa MA, Birch B. The demography and housing Federal District, Brazil, 2003-2012. Brazilian J Infect

conditions of Palestinian refugees in and around the Dis. 2017; 21:162-70

camps in Amman, Jordan. J Refug Stud. 1993;6:403-13. 27. Kibler CS, Watson SH. The place of the sun in treating

9. Jaganath D, Mupere E. Childhood tuberculosis and tuberculosis. Chest. 1935;1:18-20.

malnutrition. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1809-15. 28. Ditjen-P2PL. Petunjuk teknis manajemen tuberkulosis

10. WHO. Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes anak. Jakarta: Direktorat Jenderal Pengendalian Penyakit

on the management of tuberculosis in children. Geneva: dan Penyehatan Lingkungan Kementerian Kesehatan

World Health Organization; 2014. Republik Indonesia; 2013. [In Indonesian]

11. Kleinbaum D, Kupper L, Nizam A, Rosenberg E. Applied 29. Marquez C, Davis JL, Katamba A, Haguma P, Ochom E,

regression analysis and other multivariable methods. Ayakaka I, et al. Assessing the quality of tuberculosis

Nelson Education; 2013. evaluation for children with prolonged cough presenting

12. National Institute of Health Research and Development. to routine community health care settings in rural

Basic Health Research in 2013. Jakarta: National Institute Uganda. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105935.

of Health Research and Development, Ministry of Health 30. Gibson M, Petticrew M, Bambra C, Sowden AJ, Wright

Indonesia; 2013. KE, Whitehead M. Housing and health inequalities: A

13. WHO. Recommendations for investigation contacts of synthesis of systematic reviews of interventions aimed at

person with infection tuberculosis in low-and middle- different pathways linking housing and health. Health

Place. 2011;17:175-84.

Makara J. Health Res. December 2017 | Vol. 21 | No. 3

Вам также может понравиться

- Level of Exposure To Childhood Tuberculosis in Household Contacts With Adult Pulmonary TuberculosisДокумент6 страницLevel of Exposure To Childhood Tuberculosis in Household Contacts With Adult Pulmonary Tuberculosisdapajiangu asniОценок пока нет

- Mendeley 03Документ5 страницMendeley 03faraОценок пока нет

- 43-Article Text-117-1-10-20200210Документ11 страниц43-Article Text-117-1-10-20200210ChacongsОценок пока нет

- Youth Perspective On Pulmonary Tuberculosis Parent's CareДокумент7 страницYouth Perspective On Pulmonary Tuberculosis Parent's CareIJPHSОценок пока нет

- Wurzel 2016Документ8 страницWurzel 2016prolanis pkmmulyoharjoОценок пока нет

- Risk Factor TuberculinДокумент7 страницRisk Factor TuberculinAnonymous oUg5v1p4zОценок пока нет

- Ajol File Journals - 494 - Articles - 112516 - Submission - Proof - 112516 5833 312396 1 10 20150204Документ6 страницAjol File Journals - 494 - Articles - 112516 - Submission - Proof - 112516 5833 312396 1 10 20150204ASK De OliveiraОценок пока нет

- 259-Article Text-998-1-10-20191127 PDFДокумент12 страниц259-Article Text-998-1-10-20191127 PDFyayahОценок пока нет

- Pencabutan Ventilator Journal ReadingДокумент19 страницPencabutan Ventilator Journal ReadingzainОценок пока нет

- BMJ c4978 FullДокумент6 страницBMJ c4978 Fulljesusm_115Оценок пока нет

- Infants Hospitalized For Bordetella Pertussis Infection Commonly Have Respiratory Viral CoinfectionsДокумент6 страницInfants Hospitalized For Bordetella Pertussis Infection Commonly Have Respiratory Viral CoinfectionsYuscha AnindyaОценок пока нет

- Tuberculosis in Children Exposed at Home To MultidrugДокумент12 страницTuberculosis in Children Exposed at Home To MultidrugElsa HasibuanОценок пока нет

- Paediatrica Indonesiana: Clarissa Cita Magdalena, Budi Utomo, Retno Asih SetyoningrumДокумент7 страницPaediatrica Indonesiana: Clarissa Cita Magdalena, Budi Utomo, Retno Asih SetyoningrumputerinmОценок пока нет

- As Ma Pediatric AДокумент6 страницAs Ma Pediatric APatricia GuíoОценок пока нет

- Cep 2020 00339Документ23 страницыCep 2020 00339Elison J PanggaloОценок пока нет

- TB AnakДокумент6 страницTB AnakHerlin Ajeng NurrahmaОценок пока нет

- Hubungan Riwayat Kontak Penderita Tuberkulosis Paru (TB) Dengan Kejadian TB Paru Anak Di Balai Pengobatan Penyakit Paru-Paru (Bp4) PurwokertoДокумент6 страницHubungan Riwayat Kontak Penderita Tuberkulosis Paru (TB) Dengan Kejadian TB Paru Anak Di Balai Pengobatan Penyakit Paru-Paru (Bp4) PurwokertoIra TryОценок пока нет

- Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Children: Myths and FactsДокумент4 страницыCommunity-Acquired Pneumonia in Children: Myths and FactsFranciscoDelgadoОценок пока нет

- Literature ToddlerДокумент4 страницыLiterature ToddlerValarmathiОценок пока нет

- 7 Mira 64 - 79Документ16 страниц7 Mira 64 - 79Faizal Rezza FahlefiОценок пока нет

- Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Children With HumanДокумент12 страницExtensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Children With Humanromeoenny4154Оценок пока нет

- Neumonia Por InfluenzaДокумент19 страницNeumonia Por InfluenzaEdgar GavilanesОценок пока нет

- ZNJ - Volume 17 - Issue 2 - Pages 1-13Документ13 страницZNJ - Volume 17 - Issue 2 - Pages 1-13Ljc JaslinОценок пока нет

- 12701-50629-1-PB-1 AnakДокумент4 страницы12701-50629-1-PB-1 AnakAni RoseОценок пока нет

- Risk Factors for Childhood TuberculosisДокумент5 страницRisk Factors for Childhood TuberculosisAnthony Huaman MedinaОценок пока нет

- Adiutarini 2Документ7 страницAdiutarini 2Eva Tirtabayu HasriОценок пока нет

- Factors Linked to Childhood Pulmonary TB CasesДокумент16 страницFactors Linked to Childhood Pulmonary TB CasesNafik MunaОценок пока нет

- Nama:Rohaninda Nim.:18.030 Tugas Resume:Bahasa Inggris Medical JournalДокумент15 страницNama:Rohaninda Nim.:18.030 Tugas Resume:Bahasa Inggris Medical JournalNhynda ParaniОценок пока нет

- Probiotics and Carriage of Streptococcus PneumoniaeДокумент9 страницProbiotics and Carriage of Streptococcus Pneumoniaeanita awОценок пока нет

- Articulo 1Документ6 страницArticulo 1Esteban Jose Hernandez ZotoОценок пока нет

- 335 Full PDFДокумент7 страниц335 Full PDFcrsscribdОценок пока нет

- Community Acquired Pneumonia in ChildrenДокумент62 страницыCommunity Acquired Pneumonia in ChildrenThea DinoОценок пока нет

- E20161309 FullДокумент12 страницE20161309 Fullwajarsi pratamiОценок пока нет

- Tdap Vaccine Effectiveness in Adolescents (Acosta 2017)Документ11 страницTdap Vaccine Effectiveness in Adolescents (Acosta 2017)gd_hbarОценок пока нет

- Jean Retrospective Analysis of Candida-Related Conditions in Childhood Cari SyO9CZhДокумент5 страницJean Retrospective Analysis of Candida-Related Conditions in Childhood Cari SyO9CZhIrsalina SalmaОценок пока нет

- 4000 11827 1 SMДокумент11 страниц4000 11827 1 SMJulia Gustina sariОценок пока нет

- Association Between Nutritional Status and Severity of Pneumonia Among Children Under Five Years Attending Wangaya District HospitalДокумент7 страницAssociation Between Nutritional Status and Severity of Pneumonia Among Children Under Five Years Attending Wangaya District HospitalchairulОценок пока нет

- Clinical and Demographic Profile of Pediatric Patients With Dengue Fever Admitted in Three Hospitals in Tagbilaran City 2161 0665 1000332Документ6 страницClinical and Demographic Profile of Pediatric Patients With Dengue Fever Admitted in Three Hospitals in Tagbilaran City 2161 0665 1000332nailaОценок пока нет

- 08 0119 PDFДокумент8 страниц08 0119 PDFAnailil MoralesОценок пока нет

- First Line FluДокумент6 страницFirst Line Flu419022 MELA ANANDA PUTRIANAОценок пока нет

- Idr 7 153 PDFДокумент13 страницIdr 7 153 PDFwubet birhanОценок пока нет

- Astma1 Jurnal ReadingДокумент10 страницAstma1 Jurnal ReadingRizki NabilaОценок пока нет

- Diagnosis of Pneumonia in Children With Dehydrating DiarrhoeaДокумент6 страницDiagnosis of Pneumonia in Children With Dehydrating DiarrhoeaEmaa AmooraОценок пока нет

- Ni Kadek Ethi Yudiastuti, Anak Agung Sagung Sawitri, Dewa Nyoman WirawanДокумент7 страницNi Kadek Ethi Yudiastuti, Anak Agung Sagung Sawitri, Dewa Nyoman WirawanRabiatulAОценок пока нет

- Pneumonia Clinical Case Study BSN 2 2 Group 4Документ43 страницыPneumonia Clinical Case Study BSN 2 2 Group 4Precious Jenichris TamayoОценок пока нет

- Probiotics and Child Care Absence Due To Infections: A Randomized Controlled TrialДокумент11 страницProbiotics and Child Care Absence Due To Infections: A Randomized Controlled TrialMuhammad FebrianОценок пока нет

- Usia TBДокумент9 страницUsia TBViviОценок пока нет

- A Community-Based Isoniazid Preventive Therapy For PDFДокумент8 страницA Community-Based Isoniazid Preventive Therapy For PDFbekele badeОценок пока нет

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptДокумент17 страницNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptAndika ZuldiansyahОценок пока нет

- Journal Reading VH 1Документ4 страницыJournal Reading VH 1richard 102017193Оценок пока нет

- Jurnal TB (Anak)Документ6 страницJurnal TB (Anak)Hakim Abdul PakayaОценок пока нет

- Childhood Asthma Is Associated With Development of Type 1 Diabetes and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Danish Nationwide Registry StudyДокумент9 страницChildhood Asthma Is Associated With Development of Type 1 Diabetes and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Danish Nationwide Registry Studykholoud mohamedОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S0929664616302480 MainДокумент9 страниц1 s2.0 S0929664616302480 MainEniola JayeolaОценок пока нет

- Fped 09 599500Документ8 страницFped 09 599500Safira SalsabilaОценок пока нет

- Trend and Outcome of Sepsis in ChildrenДокумент8 страницTrend and Outcome of Sepsis in ChildrenGunduz AgaОценок пока нет

- Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Children: Maryam Keshtkar Jahromi Batool Sharifi-MoodДокумент4 страницыPulmonary Tuberculosis in Children: Maryam Keshtkar Jahromi Batool Sharifi-MoodRositaadlОценок пока нет

- The Definition of Pneumonia, The Assessment of Severity, and Clinical Standardization in The Pneumonia Etiology Research For Child Health StudyДокумент8 страницThe Definition of Pneumonia, The Assessment of Severity, and Clinical Standardization in The Pneumonia Etiology Research For Child Health StudyHusseini ElghamryОценок пока нет

- JCDR 10 LC08Документ6 страницJCDR 10 LC08kurniawan martОценок пока нет

- Treating The Wheezing Infant: Ronina A. Covar, MD, Joseph D. Spahn, MDДокумент24 страницыTreating The Wheezing Infant: Ronina A. Covar, MD, Joseph D. Spahn, MDSophia RoseОценок пока нет

- In the Shadow of Illness: Parents and Siblings of the Chronically Ill ChildОт EverandIn the Shadow of Illness: Parents and Siblings of the Chronically Ill ChildОценок пока нет

- Anthropometry of The Scapula - Clinical and Surgical ConsiderationsДокумент8 страницAnthropometry of The Scapula - Clinical and Surgical ConsiderationsAdam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Anthropometric Study of The Proximal Radius - Does Radial Head Implant Fit in All CasesДокумент9 страницAnthropometric Study of The Proximal Radius - Does Radial Head Implant Fit in All CasesAdam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Rrtherhic Chethrthtynjhyttt I 2011Документ11 страницRrtherhic Chethrthtynjhyttt I 2011Adam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Bahan 1Документ40 страницBahan 1Adam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Bahan 2Документ25 страницBahan 2Adam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Osteogenesis Imperfecta: New Perspectives From Clinical and Translational ResearchДокумент10 страницOsteogenesis Imperfecta: New Perspectives From Clinical and Translational ResearchAdam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Good PDFДокумент6 страницGood PDFAdam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Bahan 3Документ11 страницBahan 3Adam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Current Concepts in Osteogenesis Imperfecta - Bone Structure, Biomechanics and Medical ManagementДокумент11 страницCurrent Concepts in Osteogenesis Imperfecta - Bone Structure, Biomechanics and Medical ManagementDennisFrankKondoОценок пока нет

- Nitric Oxide: SciencedirectДокумент9 страницNitric Oxide: SciencedirectAdam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Best Practice & Research Clinical AnaesthesiologyДокумент10 страницBest Practice & Research Clinical AnaesthesiologyAdam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S1043661816306697 MainДокумент13 страниц1 s2.0 S1043661816306697 MainAdam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- 09-Chandran Et AlДокумент6 страниц09-Chandran Et AlAdam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Review Article: Mouse Fracture Models: A PrimerДокумент12 страницReview Article: Mouse Fracture Models: A PrimerAdam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- 5481 21722 1 PB PDFДокумент5 страниц5481 21722 1 PB PDFAdam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Non Union of Fracture Neck of Femur For Intertrochanteric OsteotomyДокумент4 страницыNon Union of Fracture Neck of Femur For Intertrochanteric OsteotomyAdam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Influence of Age On Mechanical Properties of Healing Fractures and Intact Bones in RatsДокумент9 страницInfluence of Age On Mechanical Properties of Healing Fractures and Intact Bones in RatsAdam JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Cirugia Periodontal Manejo Recesiones Gingivales en 1 o Mas DiengtesДокумент21 страницаCirugia Periodontal Manejo Recesiones Gingivales en 1 o Mas DiengtesAlejandro MorenoОценок пока нет

- Animal System Lesson PlanДокумент6 страницAnimal System Lesson Planapi-266567690Оценок пока нет

- Request for Medical or Religious Exemption from Flu VaccineДокумент1 страницаRequest for Medical or Religious Exemption from Flu Vaccineplayboi501Оценок пока нет

- Burton's Microbiology Ch1Документ38 страницBurton's Microbiology Ch1Carl Elexer Cuyugan Ano91% (11)

- Family Nursing Care PlanДокумент3 страницыFamily Nursing Care PlanColleen De la Rosa100% (1)

- Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis TypesДокумент1 страницаJuvenile Idiopathic Arthritis TypesDinesh ReddyОценок пока нет

- CHN Ii 1-100Документ12 страницCHN Ii 1-100Yanna JaucianОценок пока нет

- SMC CompiledДокумент2 страницыSMC CompiledLovely De CastroОценок пока нет

- Chapter 20 HomeworkДокумент9 страницChapter 20 HomeworkKvn4N6Оценок пока нет

- Trifold BrochureДокумент2 страницыTrifold BrochureRendanLumbertОценок пока нет

- Mycoses: Mallare - Morales - QuibalДокумент67 страницMycoses: Mallare - Morales - QuibalBianca MoralesОценок пока нет

- Soal Uts Bahasa Inggris JBДокумент6 страницSoal Uts Bahasa Inggris JB21081010302 Moh. Ayyuhan FawwazansaОценок пока нет

- General Santos City Hospitals and Healthcare FacilitiesДокумент25 страницGeneral Santos City Hospitals and Healthcare FacilitiesVeronica HendrickОценок пока нет

- Behcet S DiseaseДокумент34 страницыBehcet S DiseaseRendyОценок пока нет

- PiodermaДокумент43 страницыPiodermashlprtОценок пока нет

- Thacker - The Shadows of Atheology - Epidemics, Power and Life After FoucaultДокумент19 страницThacker - The Shadows of Atheology - Epidemics, Power and Life After FoucaultAmbaejo96Оценок пока нет

- Elektro Fisika Dan Sumber Fisis 1 Pertemuan 2Документ21 страницаElektro Fisika Dan Sumber Fisis 1 Pertemuan 2estherОценок пока нет

- Thyroid StormДокумент23 страницыThyroid Stormtogi_siahaanОценок пока нет

- Colibacillinum in Recurrent Cystitis: Case TwoДокумент1 страницаColibacillinum in Recurrent Cystitis: Case Twommalam1969Оценок пока нет

- Nailfold Capillaroscopy in Behçet's Disease, AnalysisДокумент3 страницыNailfold Capillaroscopy in Behçet's Disease, AnalysisAlinaBОценок пока нет

- Throat PowerpointДокумент29 страницThroat Powerpointminci sensei100% (8)

- DAFTAR PUSTAKAДокумент5 страницDAFTAR PUSTAKAWina BudiartiОценок пока нет

- ABDOMINAL PARACENTESIS PROCEDUREДокумент5 страницABDOMINAL PARACENTESIS PROCEDUREVijith.V.kumar100% (1)

- AMOEBIASISДокумент18 страницAMOEBIASISRosalie RosalesОценок пока нет

- Giardia lamblia in the Small IntestineДокумент16 страницGiardia lamblia in the Small IntestineRahul ChaudharyОценок пока нет

- Parasitology Guide Questions 1Документ2 страницыParasitology Guide Questions 1Cess LacatangoОценок пока нет

- CV Natalia SergeenkoДокумент4 страницыCV Natalia SergeenkoRobert BonomoОценок пока нет

- Reviewer in Grade 8 Mapeh Quarter 3Документ1 страницаReviewer in Grade 8 Mapeh Quarter 3Ruth Aramburo0% (1)

- A Novel Exercise For Improving Lower-Extremity Functional Fitness in The ElderlyДокумент7 страницA Novel Exercise For Improving Lower-Extremity Functional Fitness in The ElderlyJulia Dewi Eka GunawatiОценок пока нет

- @MedicalBooksStore 2012 (ERS Monograph) TuberculosisДокумент271 страница@MedicalBooksStore 2012 (ERS Monograph) TuberculosisHeri GunawanОценок пока нет