Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Jhamb Capstone

Загружено:

api-358887160Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Jhamb Capstone

Загружено:

api-358887160Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Are you the lucky one?

How placement in the Advanced Learning Program(ALP) is reliant on the mechanics of an

arbitrary system

By Maya Jhamb

System-wide failure to identify superbly bright students:

My brother Jai Jhamb is currently a fourth grade student at North Street Elementary

School. Last year in March, my parents received a recommendation from his homeroom teacher,

nominating him to take the Math Advanced Learning Program(ALP) identification test.

Although my parents were enthusiastic about the possibility of Jai being placed in an gifted

education classroom, my preceding experience with the system left them under the impression

that the program was poorly constructed. Nevertheless, they registered my brother for the series

of exams, hopeful that he may be able to overcome the obstacles that I couldn’t.

Throughout all my elementary school years, I was never accepted into ALP. Feeling

stuck in a general education classroom was ultimately an unpleasant experience, as I was

unchallenged and bored, breezing through on-level curriculum with minimal effort. Through my

elementary school years, all my teachers easily identified my instant proficiency on taught

concepts, but their insufficient power over student placement only got me so far. The testing was

my prime struggle, in which I performed highly on cognitive aptitude tests, but failed to score

adequately on the same performance assessments for four successive years. In 5th grade, the

middle school placement testing finally landed me into all honors and ALP classes.

Incidentally, two months after Jai took the series of assessments, the results arrived in the

mail. I know that my brother is an incredibly gifted, high aptitude child, but it was no surprise

when he didn’t get accepted into the program. A brief analysis of his scores is as follows: on the

Starz and CogAT, which are two nationally acclaimed aptitude tests, he placed in the 99th

percentile. The only prohibiting factor was his appallingly low score of 12% on an

uncorroborated performance achievement assessment(created by the Board of Education). It was

most definitely not a coincidence that this test was identical to the exam I struggled with years

ago. Additionally, a child who consistently performs in the top 1 percentile of their age group IS

GIFTED. I am dumbfounded to think otherwise.

When I overcame the system at the end of elementary school, I really didn’t think much

of it. My inability to be accepted into ALP throughout elementary schools wasn’t a mystery, and

I primarily blamed it on myself. Perhaps I wasn’t smart enough, or perhaps other students

outperformed me in previous years. But now that I know my brother is going to be bored and

unchallenged for his remaining elementary school years, I realize the system is at fault, not me.

Jai and I aren’t the outliers, in fact, it's quite the opposite. We represent the majority of gifted

students who aren’t in ALP. Needless to say, it's time for change.

Gifted education: Obscure and Unstructured

Educational programs oftentimes attempt to nurture students of varying cognitive

aptitudes. Because intelligent and capable students are extremely common, the offering of a

gifted program is an excellent addition to all school systems. The custom curriculum challenges

these students in a way that simply cannot be achieved in a general education classroom.

Nevertheless, giftedness is extremely dynamic and manifests in several varying domains, such as

intellectually, creatively or artistically. Additionally, under certain circumstances, it can develop

in a specific academic field such as language arts, mathematics or science. While the prevalence

of flairs and talents in distinct areas is naturally inevitable, it increases the difficulty of creating

an identification test that will successfully recognize all these students. Nationally, there is not

one testing procedure that is consistently used nor effective. A correct method is solely

dependent on the prime objective of each unique program. Despite this complication, proper

placement is school administrations responsibility, and it is an incredible disservice to deprive

students from reaching their full potential. Incidentally, the Greenwich Public School Advanced

Learning Program is a profoundly flawed and poorly constructed system. Their implementation

of imperfect testing methods in combination with an uncorroborated approach ensures the failure

of the system. Because the parameters of gifted education are loosely defined, the inability to

design an exam that identifies all of these students is usually the fundamental flaw of any

advanced learning system, especially in the Greenwich Public School Advanced Learning

Program.

A Bright vs Gifted Child: An unnecessary distinction

According to the National Association of Gifted Children, a student “is gifted when their

ability is significantly above the norm for their age(NAGC, 2015).” This denotation is quite

simple. A high aptitude child whose performance is superior to that of their peers is considered

gifted. Yet, from this single, articulate definition, a contentious debate has emerged: Bright vs

Gifted children.

The proposition side candidly argues that students who are considered gifted will exhibit

signs that are disparate from that of a bright child. According to Education Psychologist

Christopher Taibbi, “a bright child knows the answer, while the gifted learner asks the

questions(Taibbi, 2017). This quotation implies that bright learners comprehend at a high level,

and demonstrate expedient mastery with taught concepts. Conversely, gifted students have

outstanding memory for certain details and make keen observations with the taught content. In

other words, while the bright student accepts and retains the content, the gifted learner will

manipulate the material to draw unique inferences. Taibbi continues by highlighting that “a

bright child enjoys school, while the gifted learner enjoys self-directed learning(Taibbi, 2015)”.

This quotation reveals that a bright child is attentive and immersed in school, while the gifted

learner is slightly engaged but not eagerly participating. Simply, the bright learner will enjoy the

curriculum, while the gifted student will tolerate it.

Although the following discrepancies may seem significant, the opposing side will argue

that these two types of learners share two consequential commonalities that capture the objective

of any program designed for high aptitude children. Any students who excel in school,

outperform their peers, and are under challenged in a general education classroom belong in a

gifted program. The assigned label of gifted or bright is irrelevant, and oftentimes fuels the

misplacement of students in Advanced Learning Programs. According to The National

Association for Gifted Children, “many times, educators are dealing with students who are

drastically under challenged in school but because they are not considered gifted (they’re “just”

bright), they are ignored by the very system that should be their champion(NAGC, 2014).”

An unvanquishable burden: The underrepresentation of minority students in gifted

education

Although placement into a gifted program should solely be based off of high aptitude and

qualifying test results, factors including socioeconomic status and race have unrightfully

deprived belonging children from learning an advanced curriculum. In the past, racism and

discrimination concerning social class prevailed, oftentimes preventing certain groups of people

from leading an equally successful and fulfilled life. Institutionalized racism is a specific form of

discrimination that is widespread in social and political institutions. The term denotes the

inability of an organization to provide objective, appropriate, and professional services based on

unwitting prejudice towards ethnic origin, culture, and race. While this inequity has greatly

reduced, race still becomes a burden in unfortunate circumstances, especially in youth education.

According to an article published in January of 2016 by U.S. News & World Report,

“when high-achieving black children were taught by a black teacher, they were just as likely as

similar high-achieving white children to be assigned to a gifted program” (2018). By revealing

that an African American teacher guarantees black students an equal chance at participating in a

gifted program, it implies that teachers of other races would impede these students from rightful

inclusion. Furthermore, a study by Vanderbilt University published earlier this year found a stark

difference among white and black students with similar test scores: When scholars surveyed

10,000 U.S. elementary children with the same math and reading scores, they found that a

high-scoring white student was twice likely as a high-scoring black student to get assigned to a

gifted and talented program. This study effectively illustrates the unadulterated racism that

unrightfully and unreasonably excludes high aptitude black students from gifted programs.

Contrary to popular belief, minorities aren’t underrepresented because they are less intelligent,

less developed, or less capable, but because authorities who make a joke out of the entire system

are feeble-minded and unable to vanquish their prejudices.

Bernie Froese-Germain, an esteemed researcher at the Canadian Teachers' Federation

suggests that “rather than incurring the expense of developing, administering, grading, and

ranking test scores to determine which schools score the highest, a socio-economic analysis of

census data of the communities where the schools are located would provide the same

information(Froese, 2018)”. Germain mentions an interesting point when referring to the

correlation between socioeconomic status and relative performance on achievement assessments.

Because standardized tests measure acquired knowledge, low-income students who can’t afford

tutoring or inside teaching simply will not perform highly when compared to those who can.

Ultimately, minorities are underrepresented in gifted programs because of uncontrollable

differences that become disadvantages and impeding factors in the pursuit of their own

education.

The lack of minority students in the Greenwich Public Schools Advanced Learning

Program is a perennial issue that has easily excluded several worthy students. As of 2015, 86%

of the program was occupied by caucasians, in both language arts and mathematics. The

remaining percentage was merely scattered amongst other races, of that including Hispanics,

Asians, African Americans, and ESL students(Greenwich District Profile). Furthermore, while

minorities account for 36.8% of the student population, they only occupy 15% of ALP

program(Greenwich District Profile). This statistic is extremely disheartening, as Greenwich is

an affluent and developed town where racial disparity shouldn’t be a burden or struggle. The

demographics are not to blame.

Achievement vs Aptitude tests: An impossible conflict

Because gifted students exhibit a high aptitude and cognitive threshold in dissimilar

ways, the use of either achievement or IQ tests can easily be a misguided decision. Giftedness is

an extremely dynamic attribute that manifests in several disparate domains. For instance, it can

be intellectual or creative, and is occasionally expressed through a specific academic field

included mathematics, language arts, or science. According to Tonya R. Moon, an associate

professor in the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia, intelligent children can

be categorized into 6 types of giftedness – “the successful, the challenging, the underground, the

dropouts, the double labeled, and the autonomous learners”(Moon 2017). While these several

groups undoubtedly contain profoundly gifted students, they are all unassociated, thus creating

an incredible challenge for administration; What kind of test will accurately recognize 90+% of

gifted learners? Ultimately, there are two types of tests popularly used for gifted student

identification: intelligence and achievement tests.

Achievement tests are used to measure acquired knowledge or skill development over

time. Standardized tests are the rawest form of achievement tests, as they measure a student's

proficiency and mastery of various concepts that have precedingly been taught. Achievements

tests are usually sensible exams that are incredibly helpful in providing a representation of what

a student has learned up to date, but when used for gifted identification testing, the prime

objective is easily warped. According to the National Association of Gifted Children, “children

are gifted when their ability is significantly above the norm for their age”(NAGC, 2019). Based

on this definition, using an achievement test for discernment is fallacious. This test can easily

exclude a gifted child, and misidentify the skills of another average student. Equal exposure is a

REQUIREMENT if these arbitrary tests are ever going to provide relevant, valid and accurate

data on a child’s intellect. How can one tell if a child is exceeding the standard for there age if

they are given an assessment that doesn’t measure potential, but simply the mastery of random

concepts?

Intelligence or cognitive aptitude measure a students potential and ability to think

critically, analyze new information, problem-solve, and reason. According to the United States

Department of Education, cognitive aptitude tests are able to provide unique and significant

information about a youth students intellectual development that can’t be recognized through

superficial analysis. The tests also provide a score that denotes how the child is performing in

several different cognitive processes. However, alike to achievement assessments, cognitive

aptitudes are FAR from perfect. These tests are structured identical to that of the Intelligence

Quotients tests(IQ), and recent studies have revealed that perhaps this optimal assessment of

human intelligence is imperfect.. According to a Canadian study published online in the journal

Neuron, the IQ test is “fundamentally flawed,” seeing that its questions “grossly oversimplify the

abilities of the human brain(2019).” This quotation suggests that perhaps the ultimate test of

human intellect is providing an inaccurate representation of aptitude.

Within the ALP system, there are currently three testing procedures used to identify

students for their math program: The Star test, a performance task, and the Cognitive Abilities

Test(CogAT).

Star t esting is a nationally qualified computer-adaptive test that is implemented as an

identification method for the ALP program. An adaptive assessment entails that the answers

given by the test-taker are analyzed, and based on accuracy, the questions increase in difficulty

and grade level. Because the increase in difficulty raises scaled score and percentile ranking, this

assessment favors students who have been exposed to higher level concepts. Therefore,

potentially gifted students who haven’t already been placed in ALP are disadvantaged compared

to current ALP students, who are learning an enriched curriculum in Mathematics or Language

Arts. Unfortunately, this unfavorable circumstance further escalates when teacher

recommendations are virtually 100% dependent on the child's scaled score. Higher learning

aptitude does not necessarily mean that a student can figure out concepts that have not been

taught to them.

The second exam used in the identification process for ALP is entitled the CogAT. This

“multiple-choice K-12 assessment measures reasoning skills with different types of verbal,

quantitative, and nonverbal questions”(Lohman,2013).” The cogAT is fundamentally an aptitude

test, as it measures a students ability to think both critically and logically under a significantly

pressing time limit. Scores are usually an accurate representation of a students cognitive

threshold/potential, and this exam is used nationwide for entry into gifted and talented programs.

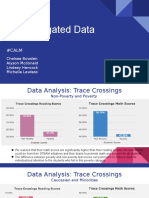

The third and final assessment used for ALP identification is a homemade performance

task. Unlike the Star and CogAT exams, which are both used nationwide, this test is completely

uncorroborated, as there is absolutely no evidence that proves it has done an effective job in

recognizing higher aptitude students. After administering an exam with three exact questions

that appeared on a fourth grade ALP performance task, I found that the average score was 6.5%,

which is a stunningly low score, especially when the assessment is designed for students that

are learning 6 grade levels below us. Fundamentally, this means that 1 in every 7 students

answered one question correctly. Furthermore, 37% of all students in Geometry were not

former Math ALP students. This means that 37% of students who were deemed average by the

system, were eventually able to take an honors math course. Of the bottom 20% of the class, in

which said individuals received a grade of 85 or below, 5 of out 6 were previously in ALP. We

have done the most research on behalf of this system, and our findings are unacceptable.

Student struggle with misplacement: Unnecessary and unacceptable

Although gifted education programs nurture students of varying cognitive aptitudes, the

misplacement of certain belonging students ultimately plays a harmful role in one’s mental

health and development. When imperfect testing methods are implemented, the chances of

misidentification increase, which increases the likelihood that students will be wrongfully

excluded or included in these programs. When less capable students are mistakenly placed into a

gifted education program, unnecessary stress is placed on the youth students, “on a scale of 1-10

and 10 being the highest stress level, around a 9 ( Dellinger, 2018)”. Experiencing extreme

anxiety is harmful, and will eventually lead to a great, rapid decline of mental health. This quote

truly illustrates the hardships for students who have been failed by the mechanics of an arbitrary

system.

On the contrary, extremely intellectual and competent students may not be given the

opportunity to excel. Gifted students who are under challenged in a general education classroom

are “usually bored and unengaged in school, and tend to be highly critical of their teachers, who

they feel know less than they do(Dweck, 2018)”. Additionally, according to Becky Bracken, the

mischief and constant disruption caused by certain students is a potential indicator of giftedness.

Unfortunately, flawed testing methods will always fail certain children, which will inflict

unnecessary burdens on these students.

Incidentally, the offering of gifted education programs for youth students will frequently

undermine the values of tenacity and motivation. According to Tonya R. Moon, children need to

learn that hard work is more important than being born with a high IQ. Placing them into a gifted

program sends the opposite message”(Moon,2017). When the ALP system misidentifies the

ability of certain students, the emotional stress on these students automatically impedes them

from reaching their full potential. Overall, it is an incredible disservice to perpetually leave a

child misplaced and helpless in the incorrect classroom.

The journey to ending this defective, dramatically flawed program

It is of my concern that the current testing procedures for the Greenwich Public Schools

Advanced Learning Program(ALP) may be poorly constructed and therefore causing less than

optimal results. This substandard approach could potentially result in a system level failure to

identify higher aptitude students and cause inefficiency/underperformance and suffering as

students are not necessarily being placed according to their abilities. The ideal goal is to

convince Bonnie O’Regan, the ALP Facilitator, to alter the current identification methods in

order to reduce the chance of misplacement for potentially high aptitude children.

Because the structure of ALP is wrongfully designed to exclude high aptitude students,

confronting the initiator is the prime objective. The program facilitator and Board of Education

are ultimately responsible for the fundamental flaws of the system. The incorrect testing methods

and unproved effectiveness of their approach increases the chances of misplacement of their

student body. A reasonable way to prompt change for ALP is to collect data that will accurately

expose its defects. It is my intention to track the performance of former ALP students at

Greenwich High School/Central Middle School, and compare it to that of Non-ALP students in

these same settings. I am nearly certain that a significant number of students who were not

placed in ALP as elementary school students will be academically exceeding their peers who

were. In June of 2019, after this vast collection of data, I would present the newfounded

information at a Board of Education Meeting, while simultaneously proposing a revised version

of the system. The Board of Education is unaware that the system is unsuccessful because they

have neglected to thoroughly test it. The current system is actually a rough draft of what a

successful gifted education program should be. The statistics and data will indicate that the

current system is not optimal. I am hopeful they will attempt to alter the procedures currently

put in place. It is of incredible importance to change these identification methods. Not only did

my my experience with the program leave me feeling helpless and under-challenged in a general

education classroom, but in later years, jumping from 5th to 8th grade math left me with large

knowledge gaps. I am determined to prevent this possibility for posterity. When an alteration in

current testing methods is identified, my supreme goal will be achieved.

Accomplishing such change certainly won’t be easy, and it is quite possible that I will

encounter several obstacles during my pursuit of system-level change in ALP. My plan is heavily

reliant on data and statistics, which may not be as revealing as I presume. While this is the

worse-case scenario, a solution would be to conduct different investigations that will identify and

improve different aspects of the program. If my primary goal can’t be achieved, at the very least,

my action plan would prompt the Board of Education to reevaluate the primary objective of the

system; proper placement for every child.

During the Capstone Research Process, I achieved several components of the Vision of

the Graduate. When creating numerous research questions to guide my note-taking and analysis,

I posed and pursued substantive questions. Additionally, I was able to critically interpret,

evaluate, and synthesize information when I was able to associate statistics about nationwide

gifted programs to that of the ALP program. Furthermore, I have created an innovative idea

through my proposed action plan that will ideally eradicate the ALP systems defects. Besides

this, I have unequivocally mastered a core body of knowledge through my extensive research

about the successful attributes of gifted education programs. Because my topic is uniform to two

other of my classmates, we have shared our discoveries, and resolved each others confusions,

thus achieving collaboration with others in order to produce unified work and/or heightened

understanding. Throughout the entire process thus far, I have chosen a topic that I am extremely

passionate about, and that has a large-scale effect on members of my community.

ALP: A cry for help and demand for change

While the unstructured parameters of gifted education is supposed to enable

personalization for varying programs, the end result is usually a fundamentally flawed system

that misidentifies the abilities of certain students, especially in the Greenwich Public School

Advanced Learning Program. Underrepresentation of minority students is a widespread issue that

is present in all gifted education classrooms nationwide. In the Greenwich Public Schools

Advanced Learning Program, 86% of the students are caucasian, while the remaining percentage

is unevenly distributed amongst other races which include Hispanics, Asians, African

Americans, and ESL students. While minority students occupy 36.8% of the Greenwich

population, only 15% are included in the program. Socio-economic status, race, and ethnic origin

should not be depriving students of an apt education, yet the defects of identification testing

methods suggests otherwise. Scores on cognitive aptitude tests and achievement tests are

commonly used to assess a child's chances of acceptance into a gifted program, but the

credibility of these tests have lately been questioned. Achievement tests measure acquired

knowledge rather than a students potential, which isn’t suggestive of high aptitude, but

proficiency of arbitrary concepts. Additionally, cognitive aptitude tests may not provide an

accurate representation of a students overall intelligence, which can easily prohibit a gifted child

from entering this program. The Greenwich Public School ALP system is designed imperfectly,

which leads to the unrightful exclusion of a majority of gifted students. The significance of Stars

scores is extremely unfair as the assessment is structured to favor children who have been

exposed to high level concepts. Additionally, the performance tasks are designed to identify high

aptitude students, yet missing out on even one child is an incredible disservice and unfortunately,

Jai and I aren’t the only ones. ALP is defective, and the fact that the system has gravely

misidentified the abilities of certain students is a cry for help, and demand for change.

Work cited :

Fields, Matthew Mugo. "Gifted and Talented Programs Dumb down Our Students." Time,

6 Feb. 2025, time.com/3698686/gifted-and-talented/. Accessed 14 Mar. 2019.

Greenwich Public Schools. 2 Feb. 2017,

www.boarddocs.com/ct/greenwich/Board.nsf/files/AJKMGL5B3200/$file/E-001%20

Advanced%20Learning%20Program%20MR%20with%20Addendum%20and%20CS

%20022317.pdf. Accessed 6 Mar. 2019.

Howell, Anna. "The Stress of AP Classes." Wildcat Scratch Post, 24 Apr. 2017,

wjstudentmedia.com/stress-ap-classes/. Accessed 15 Mar. 2019.

Morin, Amanda. “What are Achievement Tests.” Thought.co, 18 Feb. 2019,

https://www.thoughtco.com/achievement-tests-620810. Accessed 8 Mar. 2019.

New York Times Room for Debate. New York Times Company, 4 July 2010,

roomfordebate.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/04/the-pitfalls-in-identifying-a-gifted-chil

d/. Accessed 5 Mar. 2019.

The Washington Post. Washington Post, 20 Mar. 2013,

www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2013/03/20/do-schools-for-the-gift

ed-promote-segregation/?utm_term=.daf55331b771. Accessed 8 Mar. 2019.

Вам также может понравиться

- Busting Myths About Gifted LearnersДокумент4 страницыBusting Myths About Gifted LearnersAdrianОценок пока нет

- Research Proposal TallmanДокумент8 страницResearch Proposal Tallmanapi-263365115Оценок пока нет

- Identifying Gifted and Talented StudentsДокумент9 страницIdentifying Gifted and Talented StudentsSAMUEL GIERОценок пока нет

- Final Project-Reflective PaperДокумент6 страницFinal Project-Reflective Paperapi-293220147Оценок пока нет

- Title Research: The Impact of Mass Promotion On Student Literacy in Elementary SchoolДокумент15 страницTitle Research: The Impact of Mass Promotion On Student Literacy in Elementary SchoolBan ViolaОценок пока нет

- Standardized TestingДокумент9 страницStandardized TestingLinisversОценок пока нет

- Poverty Essay FinalДокумент6 страницPoverty Essay Finalapi-301252007Оценок пока нет

- GCP TilleyДокумент71 страницаGCP Tilleyapi-608529636Оценок пока нет

- Week 2 - Are Selective Schools Better For Children - 1Документ3 страницыWeek 2 - Are Selective Schools Better For Children - 1Thuy LinhОценок пока нет

- Proposal MasteralДокумент32 страницыProposal MasteralSherly Ibon SabadoОценок пока нет

- Research PaperДокумент12 страницResearch PaperZoren FajaritoОценок пока нет

- Gifted Education FinalДокумент7 страницGifted Education FinalStee MbulaОценок пока нет

- Eng13 VinceJethroRamel Essay1 DraftДокумент5 страницEng13 VinceJethroRamel Essay1 DraftJethro RamelОценок пока нет

- Practical Research 1 ObienДокумент8 страницPractical Research 1 ObienHadasah DaraydoОценок пока нет

- Arenalr Ka FinalДокумент35 страницArenalr Ka Finalapi-266873840Оценок пока нет

- Statement of The ProblemДокумент24 страницыStatement of The Problemjury custodioОценок пока нет

- Paradigm Shift EssayДокумент9 страницParadigm Shift Essayapi-317039892Оценок пока нет

- Case StudyДокумент33 страницыCase StudyDaniel RobertsОценок пока нет

- IMRADДокумент9 страницIMRADMonica MagoОценок пока нет

- Precondition For Pupils (Recovered)Документ14 страницPrecondition For Pupils (Recovered)Leany AurelioОценок пока нет

- Lack of Interest Research 1Документ14 страницLack of Interest Research 1keychain shopОценок пока нет

- Action Research On: Factors Affecting Absenteeism Among Select Grade 7 Students of Maigo National High SchoolДокумент9 страницAction Research On: Factors Affecting Absenteeism Among Select Grade 7 Students of Maigo National High SchoolAlleli Faith LeyritanaОценок пока нет

- Unintended Consequences of No Child Left Behind Mandates On Gifted StudentsДокумент13 страницUnintended Consequences of No Child Left Behind Mandates On Gifted StudentsZZОценок пока нет

- Psy. EditedДокумент11 страницPsy. EditedDISHONОценок пока нет

- PEROY, CATHERINE A. Group 6Документ3 страницыPEROY, CATHERINE A. Group 6Cathy APОценок пока нет

- Position PaperДокумент9 страницPosition Paperapi-362165549Оценок пока нет

- Primary Education Dropout Rates Among Tihar InmatesДокумент5 страницPrimary Education Dropout Rates Among Tihar Inmatesshruti100% (1)

- Inclusion, Acceleration, or Abandonment: A Look Into Gifted and Talented Programs Emma Foerster Bridgewater CollegeДокумент8 страницInclusion, Acceleration, or Abandonment: A Look Into Gifted and Talented Programs Emma Foerster Bridgewater Collegeapi-350851724Оценок пока нет

- Nagc - Identifying Gifted Poor NaespДокумент5 страницNagc - Identifying Gifted Poor Naespapi-206139354Оценок пока нет

- Eip First DraftДокумент10 страницEip First Draftapi-397985706Оценок пока нет

- Starting Kindergarten Early: by Maddie KampfДокумент10 страницStarting Kindergarten Early: by Maddie KampfMaddie AdamsОценок пока нет

- How inequality impacts education standardsДокумент3 страницыHow inequality impacts education standardsThien Kim DoОценок пока нет

- The Real Cost of The No Child Left Behind Act Annie GbafordДокумент6 страницThe Real Cost of The No Child Left Behind Act Annie Gbafordapi-579566262Оценок пока нет

- Naren Duggirala - SP Essay Final DraftДокумент10 страницNaren Duggirala - SP Essay Final Draftapi-551346711Оценок пока нет

- Teaching Between the Lines: How Youth Development Organizations Reveal the Hidden CurriculumОт EverandTeaching Between the Lines: How Youth Development Organizations Reveal the Hidden CurriculumОценок пока нет

- Researchpaperenglish 12Документ9 страницResearchpaperenglish 12api-356503082Оценок пока нет

- Are We NATs? by Engr. Herman Lagon Published July 28, 2009 in The News TodayДокумент3 страницыAre We NATs? by Engr. Herman Lagon Published July 28, 2009 in The News TodayHerman LagonОценок пока нет

- Edu 401Документ9 страницEdu 401Miralkhan003 Miralkhan003Оценок пока нет

- Critical Thinking PaperДокумент11 страницCritical Thinking PaperoliviaОценок пока нет

- How To Pass a Test: Is this the direction of Australian education today?От EverandHow To Pass a Test: Is this the direction of Australian education today?Оценок пока нет

- Hiatt, AngelaДокумент20 страницHiatt, AngelaJessica Emaden PapaОценок пока нет

- Position Proposal PaperДокумент7 страницPosition Proposal Paperapi-242368813Оценок пока нет

- Research Paper Group 2 Out of School Youth-1Документ10 страницResearch Paper Group 2 Out of School Youth-1Sherryl Ann SalmorinОценок пока нет

- The Problem and Its Background Introduction and RationaleДокумент21 страницаThe Problem and Its Background Introduction and RationaleRocel RoxasОценок пока нет

- Data Review: Edina Public Schools Case StudyДокумент8 страницData Review: Edina Public Schools Case Studyapi-284114354Оценок пока нет

- Research PaperДокумент7 страницResearch Paperapi-559332391Оценок пока нет

- Edu 401Документ9 страницEdu 401Miralkhan003 Miralkhan003Оценок пока нет

- Mod 2 annotated-EL5703 - Mod2 - ADherit - 6 - 31 - 21pdfДокумент13 страницMod 2 annotated-EL5703 - Mod2 - ADherit - 6 - 31 - 21pdfAmy DheritОценок пока нет

- Disaggregated DataДокумент13 страницDisaggregated Dataapi-299178329Оценок пока нет

- Evaluation Final Draft - Miah Leonard 1Документ7 страницEvaluation Final Draft - Miah Leonard 1api-611724200Оценок пока нет

- Talented and GiftedДокумент11 страницTalented and GiftedMegan KalinaОценок пока нет

- Problems faced by ALS learners in remote learningДокумент140 страницProblems faced by ALS learners in remote learningGrace AbaoОценок пока нет

- The Cause of Drop Out Students Among The Junior Students of Pacita Complex National High School For The School Year 2008Документ21 страницаThe Cause of Drop Out Students Among The Junior Students of Pacita Complex National High School For The School Year 2008stephanie45694% (47)

- Mitchell Goldstein - Capstone Essay FlashdraftДокумент9 страницMitchell Goldstein - Capstone Essay Flashdraftapi-358887160Оценок пока нет

- Homeschool Vs Public School Research PaperДокумент4 страницыHomeschool Vs Public School Research Papergw1qjeww100% (1)

- Google Form Analysis For The 8th GradeДокумент2 страницыGoogle Form Analysis For The 8th Gradeapi-358887160Оценок пока нет

- Math Alp Responses - Form Responses 1Документ3 страницыMath Alp Responses - Form Responses 1api-358887160Оценок пока нет

- Sample TestДокумент2 страницыSample Testapi-358887160Оценок пока нет

- Math Scores - Sheet1Документ2 страницыMath Scores - Sheet1api-358887160Оценок пока нет

- Board of Education SpeechДокумент2 страницыBoard of Education Speechapi-358887160Оценок пока нет

- Capstone PaperДокумент12 страницCapstone Paperapi-358887160Оценок пока нет

- Mitchell Goldstein - Capstone Essay FlashdraftДокумент9 страницMitchell Goldstein - Capstone Essay Flashdraftapi-358887160Оценок пока нет

- Behavioral Core Competencies TeachersДокумент2 страницыBehavioral Core Competencies Teachersjoan dalilisОценок пока нет

- SarcasmДокумент6 страницSarcasmMarto FeОценок пока нет

- 1 - Course Info TAC501dasДокумент4 страницы1 - Course Info TAC501dasFathiAziz0% (1)

- Bequest of Love: Hope of My LifeДокумент8 страницBequest of Love: Hope of My LifeMea NurulОценок пока нет

- EDUCATION IN THAILAND: REFORMS AND ACHIEVEMENTSДокумент37 страницEDUCATION IN THAILAND: REFORMS AND ACHIEVEMENTSManilyn Precillas BantasanОценок пока нет

- BSP Phase1 Manual David Grand 2Документ117 страницBSP Phase1 Manual David Grand 2Muhamad LuthfillahОценок пока нет

- STRATEGIES TO AVOID COMMUNICATION BREAKDOWN (Oral ComM3Q1)Документ4 страницыSTRATEGIES TO AVOID COMMUNICATION BREAKDOWN (Oral ComM3Q1)Joshua Lander Soquita CadayonaОценок пока нет

- (Learn Persian With Chai & Conversation) Learn Persian With Chai & Conversation - Learn Persian With Chai & Conversation-Speak (L01-L90) (2021)Документ383 страницы(Learn Persian With Chai & Conversation) Learn Persian With Chai & Conversation - Learn Persian With Chai & Conversation-Speak (L01-L90) (2021)Ranjan SharmaОценок пока нет

- Annotated Bibliography 1Документ7 страницAnnotated Bibliography 1api-355663066Оценок пока нет

- Hospital Mission Vision Values ExamplesДокумент4 страницыHospital Mission Vision Values ExamplesNesyraAngelaMedalladaVenesa100% (1)

- Stem Lesson PlanДокумент4 страницыStem Lesson Planapi-337029119Оценок пока нет

- Culture Shock: DefinitionДокумент10 страницCulture Shock: DefinitionPrecious Ivy FernandezОценок пока нет

- Mr. Andy MennickДокумент2 страницыMr. Andy Mennick2thay2Оценок пока нет

- Secondary school classes in DrariaДокумент2 страницыSecondary school classes in DrariaMrm ZwlyОценок пока нет

- W Astin Implement The Strategies and Rubric - Module 4Документ6 страницW Astin Implement The Strategies and Rubric - Module 4api-325932544Оценок пока нет

- Holding Police AccountableДокумент38 страницHolding Police AccountableMelindaОценок пока нет

- A Study On Effectiveness of Conflict Management in Apollo TyresДокумент27 страницA Study On Effectiveness of Conflict Management in Apollo TyresRanjusha AntonyОценок пока нет

- Computers in Human Behavior: A B A B A B A B A B A BДокумент8 страницComputers in Human Behavior: A B A B A B A B A B A BRemaОценок пока нет

- Minto Pyramid Principle for writing reportsДокумент38 страницMinto Pyramid Principle for writing reportsardi100% (1)

- Importance of Flower ArrangementДокумент2 страницыImportance of Flower Arrangementnitz_drОценок пока нет

- Quotes Tagged As "Love"Документ9 страницQuotes Tagged As "Love"Stephany NagreОценок пока нет

- Hospice Care PaperДокумент12 страницHospice Care Paperapi-247160803100% (2)

- AdverbДокумент30 страницAdverbcamkinozОценок пока нет

- Ti Cycles Final PDFДокумент20 страницTi Cycles Final PDFVivek Yadav0% (1)

- Annotated BibliographyДокумент4 страницыAnnotated Bibliographyapi-282290047Оценок пока нет

- Admin Assistant Receptionist Job DescriptionДокумент4 страницыAdmin Assistant Receptionist Job DescriptionMitTuyetОценок пока нет

- Project ProposalДокумент4 страницыProject ProposalRicha SomvanshiОценок пока нет

- Because of Winn Dixiech1and2Документ22 страницыBecause of Winn Dixiech1and2MONICA LUM100% (1)

- Adjudication Considerations For British Parliamentary Debate PDFДокумент20 страницAdjudication Considerations For British Parliamentary Debate PDFAcbel Rnuco100% (1)

- Music Lesson PlanДокумент15 страницMusic Lesson PlanSharmaine Scarlet FranciscoОценок пока нет