Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Tobacco, Nicotine and E-Cigarettes: Protecting Children in South Africa

Загружено:

yutefupИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Tobacco, Nicotine and E-Cigarettes: Protecting Children in South Africa

Загружено:

yutefupАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

This open-access article is distributed under

EDITORIAL Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0.

Tobacco, nicotine and e-cigarettes:

Protecting children in South Africa

A piece of health legislation that is pivotal for the health of children increasing use of nicotine in the form of e-cigarettes, in SA demand

in South Africa (SA) is currently before parliament: the draft Control a more forceful and focused response than current laws and their

of Tobacco Products and Electronic Delivery Systems Bill 2018.[1] We enforcement have achieved. As a signatory to the World Health

outline why further control of tobacco and nicotine is important for Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control,[20] SA is

the health of children in SA, and why the legislation deserves the obliged to reduce tobacco harms in the country.

strong support of all those who seek to promote the best interests of The draft Control of Tobacco Products and Electronic Delivery

children in this country. Systems Bill 2018 promises significant progress on tobacco and

Tobacco and nicotine have multiple negative effects on children. nicotine control in SA. Specifically, the legislation will benefit

These are mediated not only through primary, secondary and children through strengthened controls on:

tertiary smoking, but children are also affected by tobacco and • the display and sale of tobacco and nicotine products. Specifically,

nicotine as a result of: tobacco and nicotine products cannot be displayed in commercial

• the morbidity and premature mortality of about half of their premises. Plain packaging will be introduced.

parents and close relatives who smoke[2,3] • environmental tobacco exposure. Much wider powers are given to

• the diverting of scarce household resources away from children limit smoking in public spaces. Smoking in public indoor spaces

• environmental degradation brought on by tobacco-related such as restaurants and bars is prohibited. No-one travelling in

agriculture, cigarette manufacture[4] and waste from tobacco and a vehicle in which a child (up to 18 years of age) is present may

nicotine products[5] smoke.

• their susceptibility to experimentation during childhood and • access to information about and regulation of the contents of

adolescence. tobacco and nicotine products.

• all forms of tobacco and nicotine produced by the tobacco industry.

Environmental tobacco from cigarettes is the main means by which

harm is done to children by tobacco and nicotine. Secondary Importantly, the Bill provides controls over e-cigarettes and other

smoking is mediated by environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) being electronic nicotine products for the first time in SA. Evidence

inhaled by children and pregnant women, but tertiary smoking, suggests that these products can provide a conduit to smoking

through tobacco smoke residues on clothes, furniture and other of tobacco products and threaten to increase levels of nicotine

objects, also detrimentally affects children’s respiratory tracts.[6] The addiction.[21] Given the highly addictive properties of nicotine, its

relative risk of respiratory tract infection is 1.5 in children exposed ability to alter the function of young brains permanently and the

to ETS;[7] the relative risk of acute otitis media is 1.7.[8] Pneumonia, propensity of adolescents to experiment, these controls are needed.

the most common post-neonatal cause of death and reason for The toxicity of the fumes to children from these products is not yet

admission to hospital in children aged 5 years and below in SA, is clear. However, increasing evidence points to both nicotine and the

twice as likely in children exposed to ETS.[9] aerosols from these products resulting in significant harm, including

Asthma, the most common long-term condition in children, pulmonary inflammation, impaired immunity and reduced lung

can be unmasked by ETS exposure.[10] Through epigenetic factors, function.[22] Ingestion of the fluids used in e-cigarettes is harmful,

smoking in previous generations increases the likelihood of a even fatal, to children.[23]

genetic propensity to asthma manifesting as the disease in a child.[11] One aspect of the bill requires strengthening, we believe. The bill

Children living with adult smokers have asthma that is more difficult provides an opportunity to introduce the tobacco-free generation

to control than those living in tobacco-free households.[12] (TFG) concept[24] into SA legislation and social mores. TFG takes as

Women who smoke or inhale ETS during pregnancy run the its starting points that:

risk of stillbirth or delivering a low birth-weight baby.[13] Infants of • most people who take up nicotine and/or tobacco do so at a young

mothers who smoked during pregnancy have lower lung function at age, largely through peer pressure, before they understand the

birth and impaired lung growth in early life,[14] potentially increasing implications for their health and the health of those around them;

their susceptibility to respiratory tract illnesses.[15] Evidence suggests and

that these exposures also reduce cognitive abilities in children[16] and • there is no age after which it is acceptable to start smoking or using

increase their cancer risk.[17] tobacco.

Tobacco and nicotine are thus the cause of significant health costs

during childhood, costs which are not sufficiently recognised in the The addictive properties of nicotine make it difficult to quit the habit

face of the epidemic of adult tobacco-related diseases, but which have once started. TFG proposes that anyone born after a date specified

lifelong consquences for children. Tackling ETS exposure antenatally in regulations associated with tobacco control legislation may never

and through childhood is a child health priority. This should focus be sold tobacco- and nicotine-containing products by any vendor.[24]

not only on the enormous challenge of reducing the burden of adult Providing a future date for this proscription allows time for the idea

smoking, but also on preventing another generation of tobacco and to be taken on board by society and to become normative.[24] The

nicotine addicts. TFG approach has entered statute books in Singapore and Tasmania,

In SA, 37% of men and 7% of women smoke regularly, with and is being considered in other jurisdictions.

higher percentages in the Western and Northern Cape provinces, The constitutional rights of children and adolescents to life, clean

particularly among women (25% and 18% respectively).[18 environments and health are continuously violated by the broad

While SA has made strides in recent years in reducing tobacco negative effects of tobacco and nicotine in SA. Their best interests

harms in the country,[19] the harmful effects of tobacco and nicotine demand that this legislation be passed undiluted, and strengthened

on children and the continuing widespread use of tobacco, and by the inclusion of TFG clauses.

4 SAJCH APRIL 2019 Vol. 13 No. 1

EDITORIAL

A T R Westwood, A Vanker, D Gray 12. Wang Z, May SM, Charoenlap S, et al. Effects of secondhand smoke exposure

Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health on asthma morbidity and health care utilisation in children: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015;115(5):396-401

Sciences, University of Cape Town, and Red Cross War Memorial e392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2015.08.005

Children’s Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa 13. Leonardi-Bee J, Britton J, Venn A. Secondhand smoke and adverse fetal

anthony.westwood@uct.ac.za outcomes in nonsmoking pregnant women: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics

2011;127(4):734-741. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3041

14. Gray D, Willemse L, Visagie A, et al. Determinants of early-life lung function

1. South Africa. Draft Control of Tobacco Products and Electronic Delivery in African infants. Thorax 2017;72(5):445-450. https://doi.org/10.1136/

Systems Bill, No. B475, 2018. thoraxjnl-2015-207401

2. Wipfli HL, Samet JM. Second-hand smoke’s worldwide disease toll. Lancet 15. Gray DM, Turkovic L, Willemse L, et al. Lung function in African infants in

2011;377(9760):101-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61922-8 the Drakenstein Child Health Study. Impact of lower respiratory tract illness.

3. Öberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, Peruga A, Prüss-Ustün A. Worldwide Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195(2):212-220. https://doi.org/10.1164/

burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: A retrospective rccm.201601-0188OC

analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet 2011;377(9760):139-146. https:// 16. Yolton K, Khoury J, Xu Y, et al. Low-level prenatal exposure to nicotine and

doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61388-8

4. Novotny TE, Bialous SA, Burt L, et al. The environmental and health impacts infant neurobehavior. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2009;31(6):356-363. https//

of tobacco agriculture, cigarette manufacture and consumption. Bull World doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2009.07.004

Health Organ 2015;93(12):877-880. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.15.152744 17. John EM, Savitz DA, Sandler DP. Prenatal exposure to parent’s smoking

5. Healton CG, Cummings MK, O’Connor RJ, Novotny TE. Butt really? The and childhood cancer. Am J Epidemiol 1991;133(2):123-132. https://doi.

environmental impact of cigarettes. Tobacco Control 2011;20(Suppl 1). https:// org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115851

doi.org/10.1136/tc.2011.043729 18. National Department of Health, Statistics South Africa, South African Medical

6. Acuff L, Fristoe K, Hamblen J, Smith M, Chen J. Third-hand smoke: Old Research Council, ICF. South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016:

smoke, new concerns. J Community Health 2016;41(3):680-687. https://doi. Key indicators. Pretoria: NDoH, Stats SA, SAMRC, ICF, 2017.

org/10.1007/s10900-015-0114-1 19. Reddy P, James S, Sewpaul R, et al. A decade of tobacco control: The South

7. Jones LL, Hashim A, McKeever T, Cook DG, Britton J, Leonardi-Bee J. Parental African case of politics, health policy, health promotion and behaviour change.

and household smoking and the increased risk of bronchitis, bronchiolitis and S Afr Med J 2013;103(11):835-840. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.6910

other lower respiratory infections in infancy: Systematic review and meta- 20. World Health Organization. Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on

analysis. Respiratory Res 2011;12:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-12-5 Tobacco Control. http://www.who.int/fctc/signatories_parties/en (accessed 10

8. Jones LL, Hassanien A, Cook DG, Britton J, Leonardi-Bee J. Parental smoking

and the risk of middle ear disease in children: A systematic review and meta- August 2018).

analysis. Arch Pediatrics Adolescent Med 2012;166(1):18-27. https://doi. 21. Schraufnagel DE. Electronic cigarettes: Vulnerability of youth. Pediatr Allergy

org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.158 Immunol Pulmonol 2015;28(1):2-6. https://doi.org/10.1089/ped.2015.0490

9. Le Roux DM, Myer L, Nicol MP, Zar HJ. Incidence and severity of childhood 22. Ferkol TW, Farber HJ, La Grutta S, et al. Electronic cigarette use in youths:

pneumonia in the first year of life in a South African birth cohort: The A position statement of the Forum of International Respiratory Societies. Eur

Drakenstein Child Health Study. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3(2):e95-e103. Respir J 2018:51(5):1800278. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00278-2018

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70360-2 23. Miller A. Nicotine poisoning increase due to e-cigs. CMAJ 2014;186(10):e367.

10. Mitchell EA, Beasley R, Keil U, Montefort S, Odhiambo J, Group IPTS. The https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-4818

association between tobacco and the risk of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis 24. Berrick AJ. The tobacco-free generation proposal. Tob Control 2013;22(Suppl 1):S22-S26.

and eczema in children and adolescents: Analyses from Phase Three https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050865

of the ISAAC programme. Thorax 2012;67(11):941-949. https://doi.

org/10.1023/A:1015500508261

11. Magnus MC, Haberg SE, Karlstad O, Nafstad P, London SJ, Nystad W.

Grandmother’s smoking when pregnant with the mother and asthma in

the grandchild: The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Thorax

2015;70(3):237-243. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206438 S Afr J Child Health 2019;13(1):4-5. DOI:10.7196/SAJCH.2019.v13i1.1639

5 SAJCH APRIL 2019 Vol. 13 No. 1

Вам также может понравиться

- Tracer Methodology: Frontline Strategies To Prepare For JCI SurveyДокумент23 страницыTracer Methodology: Frontline Strategies To Prepare For JCI SurveyTettanya Iyu Sama Ariqah50% (2)

- Integrating ReflexesДокумент2 страницыIntegrating ReflexesAbigail Tan100% (2)

- Tobacco Use and Smoke Exposure in ChildrenДокумент15 страницTobacco Use and Smoke Exposure in ChildrenAndreea TanaseОценок пока нет

- Spindel2016 PDFДокумент9 страницSpindel2016 PDFlylasherliaОценок пока нет

- The Effects of Cigarette Smoking To The Health of Automotive Grade 11 and Grade 12 Students in Computer Reseacrh Network, INC Background of The StudyДокумент9 страницThe Effects of Cigarette Smoking To The Health of Automotive Grade 11 and Grade 12 Students in Computer Reseacrh Network, INC Background of The StudyRuel OrculloОценок пока нет

- RRL 2Документ5 страницRRL 2K-sey MasanqueОценок пока нет

- Adolescent SmokingДокумент9 страницAdolescent SmokingSarah Ong SiuОценок пока нет

- A3 Cigarette SmokingДокумент3 страницыA3 Cigarette Smokinggeraldandrin719Оценок пока нет

- Ecigarete Use Among Youth and Young AdultsДокумент298 страницEcigarete Use Among Youth and Young AdultsAsd EfgОценок пока нет

- 2016 SGR Full Report Non-508 PDFДокумент298 страниц2016 SGR Full Report Non-508 PDFkamalkumar15Оценок пока нет

- Policy On Tobacco Use: Latest RevisionДокумент5 страницPolicy On Tobacco Use: Latest Revisionnona aryanОценок пока нет

- Journal Pone 0252817Документ16 страницJournal Pone 0252817ptriw nigsihОценок пока нет

- Argumentative Essay ElcДокумент4 страницыArgumentative Essay ElcSITI RASHIDAH BAHAMANОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1Документ27 страницChapter 1Conavil TamponОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S2211335522002716 MainДокумент8 страниц1 s2.0 S2211335522002716 MainMuhamad risalОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 5Документ36 страницChapter 1 5LucyОценок пока нет

- Predictors of Cigarette Smoking Among AdolescentsДокумент10 страницPredictors of Cigarette Smoking Among AdolescentsPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalОценок пока нет

- Knowledge and Attitude Related To Use of Electronic Cigarettes Among Undergraduate Nursing StudentsДокумент6 страницKnowledge and Attitude Related To Use of Electronic Cigarettes Among Undergraduate Nursing StudentsRobby RanidoОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 5Документ43 страницыChapter 1 5Mayie Sinilong100% (2)

- 2023 - Vaping Among Young People-Our Best Defence Is Self-Defence - 4pДокумент4 страницы2023 - Vaping Among Young People-Our Best Defence Is Self-Defence - 4pAna BorgesОценок пока нет

- Surgeon Generals Advisory On e Cigarette Use Among Youth 2018Документ4 страницыSurgeon Generals Advisory On e Cigarette Use Among Youth 2018Lawrence EmersonОценок пока нет

- Harmful EffectsДокумент2 страницыHarmful EffectsCeoDanielОценок пока нет

- Indian Tobacco Control ActДокумент27 страницIndian Tobacco Control ActIndonesia TobaccoОценок пока нет

- Term Paper On TobaccoДокумент6 страницTerm Paper On Tobaccoc5ng67v1100% (1)

- Presentacion MetodologíaДокумент26 страницPresentacion MetodologíaCamila GuevaraОценок пока нет

- SmokingДокумент8 страницSmokingMonda Bw'OnchwatiОценок пока нет

- ManuscriptДокумент39 страницManuscriptJasmine AgustinОценок пока нет

- A Proposed Policy Agenda For Electronic Cigarettes in The US: Product, Price, Place, and PromotionДокумент8 страницA Proposed Policy Agenda For Electronic Cigarettes in The US: Product, Price, Place, and PromotionBrent StaffordОценок пока нет

- Addressing Common Myths About Vaping ASH UK Aug 2023 BriefДокумент14 страницAddressing Common Myths About Vaping ASH UK Aug 2023 BriefakinpuddyОценок пока нет

- Price Elasticity of Demand For Cigarettes Among Youths in High-Income Countries A Systematic Review8Документ9 страницPrice Elasticity of Demand For Cigarettes Among Youths in High-Income Countries A Systematic Review8BoОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 5Документ36 страницChapter 1 5Dino Dizon100% (1)

- Health Effects of Secondhand Smoke - CDCДокумент4 страницыHealth Effects of Secondhand Smoke - CDCLois SullivanОценок пока нет

- Literature ReviewДокумент9 страницLiterature Reviewcurielrobert54Оценок пока нет

- Elec Cig RRLДокумент4 страницыElec Cig RRLAmelite MeriñoОценок пока нет

- Thesis About Cigarette Smoking in The PhilippinesДокумент6 страницThesis About Cigarette Smoking in The PhilippinesCarrie Tran100% (2)

- English For Academic Purposes (LE 4000) : Dr. Wan Narmi Aziana BT Wan AbdullahДокумент10 страницEnglish For Academic Purposes (LE 4000) : Dr. Wan Narmi Aziana BT Wan AbdullahCG MuhammadОценок пока нет

- What Is Secondhand SmokeДокумент14 страницWhat Is Secondhand SmokeHershey NessОценок пока нет

- Ko Witt 2019Документ16 страницKo Witt 2019Essay NationОценок пока нет

- Research Article: Smoking Habits Among Italian Adolescents: What Has Changed in The Last Decade?Документ9 страницResearch Article: Smoking Habits Among Italian Adolescents: What Has Changed in The Last Decade?novita indahОценок пока нет

- Text 2 - Part 1Документ3 страницыText 2 - Part 1Laura SilvaОценок пока нет

- Term Paper in English IV - BДокумент18 страницTerm Paper in English IV - BJai-JaiAdalidОценок пока нет

- T E T B P S: HE Ffects of Axes and Ans On Assive MokingДокумент38 страницT E T B P S: HE Ffects of Axes and Ans On Assive MokingBill HanneganОценок пока нет

- Position PaperДокумент5 страницPosition Paperjulianne tanОценок пока нет

- Argumentative Essay TemplateДокумент7 страницArgumentative Essay Templategwapogi0320Оценок пока нет

- ASH Temp Bed8Документ11 страницASH Temp Bed8AchmadMuzakkyDityanaОценок пока нет

- Teenage Smoking Addiction in The PhilippinesДокумент4 страницыTeenage Smoking Addiction in The PhilippinesHerford Rei GuibangguibangОценок пока нет

- A Qualitative Study of Smoking Behaviors Among Teenager in PhilippinesДокумент24 страницыA Qualitative Study of Smoking Behaviors Among Teenager in PhilippinesJohn Felix LontokОценок пока нет

- Research Paper About Cigarette Smoking in The PhilippinesДокумент7 страницResearch Paper About Cigarette Smoking in The PhilippinesyvunfevgfОценок пока нет

- Teenage Smoking: Trends and SolutionsДокумент12 страницTeenage Smoking: Trends and SolutionsAbu BakarОценок пока нет

- Dadivas, Fely Elaine 11-Humility (Stem)Документ2 страницыDadivas, Fely Elaine 11-Humility (Stem)Fely Elaine DadivasОценок пока нет

- Module in Health - 2ND GradingДокумент15 страницModule in Health - 2ND GradingKenn AlmazanОценок пока нет

- Smoke-Free Policies in The Global South: Nicotine & Tobacco Research October 2020Документ3 страницыSmoke-Free Policies in The Global South: Nicotine & Tobacco Research October 2020Ankita RanaОценок пока нет

- LifestyleДокумент55 страницLifestyleiyangtejanoОценок пока нет

- The Opinions of Adults About The Ban On Cigarette Sales To MinorsДокумент10 страницThe Opinions of Adults About The Ban On Cigarette Sales To MinorsTanveer SultanОценок пока нет

- Research Proposal Final DraftДокумент5 страницResearch Proposal Final Draftapi-742693616Оценок пока нет

- Chapter 1-5Документ36 страницChapter 1-5Glenn Midel Delos Santos90% (42)

- Disposable Vapes To Be Banned Over Concerns of SHДокумент1 страницаDisposable Vapes To Be Banned Over Concerns of SHdubОценок пока нет

- Tobacco Use ThesisДокумент7 страницTobacco Use Thesisericawrightalbuquerque100% (2)

- Dangers of Vaping 03.15.2019Документ23 страницыDangers of Vaping 03.15.2019Emily EresumaОценок пока нет

- Literature Review On Smoking During PregnancyДокумент6 страницLiterature Review On Smoking During Pregnancyaflsqrbnq100% (1)

- Factors Associated With A Shorter Duration of Breastfeeding: Key Words Breastfeeding, Epidemiology, ChildДокумент10 страницFactors Associated With A Shorter Duration of Breastfeeding: Key Words Breastfeeding, Epidemiology, ChildyutefupОценок пока нет

- Studies Assessing Food Consumption by The Scores Method: A Systematic ReviewДокумент16 страницStudies Assessing Food Consumption by The Scores Method: A Systematic ReviewyutefupОценок пока нет

- Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction Syndrome and Police Work Stress: An Integrative ReviewДокумент14 страницTemporomandibular Joint Dysfunction Syndrome and Police Work Stress: An Integrative ReviewyutefupОценок пока нет

- Challenges Facing HIV Treatment As Prevention in Brazil: An Analysis Drawing On Literature On TestingДокумент16 страницChallenges Facing HIV Treatment As Prevention in Brazil: An Analysis Drawing On Literature On TestingyutefupОценок пока нет

- Association of Severe Stunting in Indigenous Yanomami Children With Maternal Short Stature: Clues About The Intergerational TransmissionДокумент10 страницAssociation of Severe Stunting in Indigenous Yanomami Children With Maternal Short Stature: Clues About The Intergerational TransmissionyutefupОценок пока нет

- Public Prosecutor's Office and Social Control in The National Unified Health System: A Systematic ReviewДокумент10 страницPublic Prosecutor's Office and Social Control in The National Unified Health System: A Systematic ReviewyutefupОценок пока нет

- Physiotherapy For New Actors: Disputes and Innovations in Care For Chronically Ill ChildrenДокумент10 страницPhysiotherapy For New Actors: Disputes and Innovations in Care For Chronically Ill ChildrenyutefupОценок пока нет

- Inequality, Difference, Articulation: Sergio CostaДокумент14 страницInequality, Difference, Articulation: Sergio CostayutefupОценок пока нет

- The Implementation of Senior Health Care in The Family Health Strategy: The View of Professionals and ManagersДокумент10 страницThe Implementation of Senior Health Care in The Family Health Strategy: The View of Professionals and ManagersyutefupОценок пока нет

- Engaging People With Chronic Kidney Disease in Their Own Care An Integrative ReviewДокумент10 страницEngaging People With Chronic Kidney Disease in Their Own Care An Integrative ReviewyutefupОценок пока нет

- Microscale Direct Transesterification of Microbial Biomass With Ethanol For Screening of Microorganisms by Its Fatty Acid ContentДокумент11 страницMicroscale Direct Transesterification of Microbial Biomass With Ethanol For Screening of Microorganisms by Its Fatty Acid ContentyutefupОценок пока нет

- Health Technology Assessment in Brazil - An International PerspectiveДокумент14 страницHealth Technology Assessment in Brazil - An International PerspectiveyutefupОценок пока нет

- Ways of Seeing and Doing: Health, Disease and Care in Marketers' Family UnitsДокумент10 страницWays of Seeing and Doing: Health, Disease and Care in Marketers' Family UnitsyutefupОценок пока нет

- THE RACIAL STATE OF THE UNION: Understanding Race and Racial Inequality in The United States of AmericaДокумент16 страницTHE RACIAL STATE OF THE UNION: Understanding Race and Racial Inequality in The United States of AmericayutefupОценок пока нет

- Coping With Problems That Impact On The Health of A Socially Vulnerable Community From The Residents' PerspectiveДокумент10 страницCoping With Problems That Impact On The Health of A Socially Vulnerable Community From The Residents' PerspectiveyutefupОценок пока нет

- Walker-256 Tumor: Experimental Model, Implantation Sites and Number of Cells For Ascitic and Solid Tumor DevelopmentДокумент13 страницWalker-256 Tumor: Experimental Model, Implantation Sites and Number of Cells For Ascitic and Solid Tumor DevelopmentyutefupОценок пока нет

- Microalgae: Cultivation Aspects and Bioactive Compounds: Review - Biological and Applied SciencesДокумент13 страницMicroalgae: Cultivation Aspects and Bioactive Compounds: Review - Biological and Applied SciencesyutefupОценок пока нет

- Development and Psychometric Properties of TQWL-42 To Measure The Quality of Work LifeДокумент9 страницDevelopment and Psychometric Properties of TQWL-42 To Measure The Quality of Work LifeyutefupОценок пока нет

- Gut: Key Element On Immune System Regulation: Review - Human and Animal HealthДокумент14 страницGut: Key Element On Immune System Regulation: Review - Human and Animal HealthyutefupОценок пока нет

- Population Changes of Eubacteria, Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria and Methanogenic Archaea in An Anaerobic Reactor Processing Ethanol Distillery VinasseДокумент13 страницPopulation Changes of Eubacteria, Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria and Methanogenic Archaea in An Anaerobic Reactor Processing Ethanol Distillery VinasseyutefupОценок пока нет

- Effects of PH, Temperature and Agitation On The Decolourisation of Dyes by Laccase-Containing Enzyme Preparation From Pleurotus Sajor-CajuДокумент21 страницаEffects of PH, Temperature and Agitation On The Decolourisation of Dyes by Laccase-Containing Enzyme Preparation From Pleurotus Sajor-CajuyutefupОценок пока нет

- Pseudomonas Aeruginosa: Virulence Factors: and Antibiotic Resistance GenesДокумент15 страницPseudomonas Aeruginosa: Virulence Factors: and Antibiotic Resistance GenesyutefupОценок пока нет

- Biosurfactant Production by Bacillus Strains Isolated From Sugar Cane Mill WastewatersДокумент12 страницBiosurfactant Production by Bacillus Strains Isolated From Sugar Cane Mill WastewatersyutefupОценок пока нет

- In Silico Characterization of Meloidogyne Genus: Nematode Cellulose Binding ProteinsДокумент13 страницIn Silico Characterization of Meloidogyne Genus: Nematode Cellulose Binding ProteinsyutefupОценок пока нет

- Use of Inert Gases For The Preservation of Nuclear Blood CellsДокумент7 страницUse of Inert Gases For The Preservation of Nuclear Blood CellsyutefupОценок пока нет

- Area Triangulation Method For Automatic Detection of Venous Emptying ManeuversДокумент11 страницArea Triangulation Method For Automatic Detection of Venous Emptying ManeuversyutefupОценок пока нет

- 1516 8913 Babt 62 E19170562Документ11 страниц1516 8913 Babt 62 E19170562yutefupОценок пока нет

- Enhanced Production of Streptokinase by Chemical Mutagenesis of Streptococcus Agalactiae EBL-20Документ17 страницEnhanced Production of Streptokinase by Chemical Mutagenesis of Streptococcus Agalactiae EBL-20yutefupОценок пока нет

- Protective Effect of Rosa Canina Extract Against Doxorubicin-Induced Testicular Toxicity in MiceДокумент17 страницProtective Effect of Rosa Canina Extract Against Doxorubicin-Induced Testicular Toxicity in MiceyutefupОценок пока нет

- Consortium of Microalgae For Tannery Effluent Treatment: Article - Environmental SciencesДокумент10 страницConsortium of Microalgae For Tannery Effluent Treatment: Article - Environmental SciencesyutefupОценок пока нет

- Gap Analysis of Out Patient Department: Taniya BhattacharjeeДокумент39 страницGap Analysis of Out Patient Department: Taniya BhattacharjeeTaniya BhattacharjeeОценок пока нет

- Bone Anchored Maxillary Protraction 2012 American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial OrthopedicsДокумент2 страницыBone Anchored Maxillary Protraction 2012 American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial OrthopedicsjosemtzzОценок пока нет

- Laws Affecting Community Health Nursing PracticeДокумент2 страницыLaws Affecting Community Health Nursing PracticeFlylessSkylarkОценок пока нет

- Formula Selection OPNPGДокумент2 страницыFormula Selection OPNPGRina PratiwiОценок пока нет

- Acog Practice Bulletin: Early Pregnancy LossДокумент11 страницAcog Practice Bulletin: Early Pregnancy LossAlberto Kenyo Riofrio PalaciosОценок пока нет

- International Journal of Paleopathology: S. MaysДокумент8 страницInternational Journal of Paleopathology: S. MaysErna MiraniОценок пока нет

- 2005 AFA InglesДокумент5 страниц2005 AFA InglesAgatha Nascimento Dos SantosОценок пока нет

- Strolling Match PDFДокумент100 страницStrolling Match PDFHK15100% (1)

- Case Report: Aesthetic Depigmentation of Gingival Smoker's Melanosis Using Carbon Dioxide LasersДокумент6 страницCase Report: Aesthetic Depigmentation of Gingival Smoker's Melanosis Using Carbon Dioxide LasersAsy-syifa Brillian AvicennaОценок пока нет

- Cirrus How To Read en OUS en 31 011 0002II Final3Документ28 страницCirrus How To Read en OUS en 31 011 0002II Final3Alondra Verdugo GómezОценок пока нет

- DysmenorrheaДокумент35 страницDysmenorrheaAs-sifa KharismaОценок пока нет

- Pediatrics: A Resource GuideДокумент35 страницPediatrics: A Resource GuideKarl Martin PinedaОценок пока нет

- LeptospirosisДокумент2 страницыLeptospirosisGurungSurajОценок пока нет

- RadiologyДокумент11 страницRadiologyCatalina CirnatuОценок пока нет

- FP561 Suryakanta JayasinghДокумент3 страницыFP561 Suryakanta Jayasinghsuryakanta jayasinghОценок пока нет

- Powder PharmaceuticsДокумент58 страницPowder PharmaceuticskishnapraveenОценок пока нет

- Radiologist ResumeДокумент6 страницRadiologist Resumevyp0wosyb1m3100% (2)

- Guidelines For Contemporary Air-Rotor StrippingДокумент6 страницGuidelines For Contemporary Air-Rotor StrippingGerman Cabrera DiazОценок пока нет

- Abc 2Документ5 страницAbc 2Eyana RomanОценок пока нет

- 2012 West Central Ohio Medical Directory - Fall and WinterДокумент64 страницы2012 West Central Ohio Medical Directory - Fall and WinterThe Lima NewsОценок пока нет

- India Festival Book3Документ25 страницIndia Festival Book3Rangothri Sreenivasa SubramanyamОценок пока нет

- Critical Care/Intensive Care Unit Experience Internal Medicine INM.M INM.S CourseДокумент11 страницCritical Care/Intensive Care Unit Experience Internal Medicine INM.M INM.S CourseAmer Moh SarayrahОценок пока нет

- Nebulization (Final Output)Документ5 страницNebulization (Final Output)Tamil Villardo100% (2)

- The POWER of WHEY & MCT For Critically Ill PatientsДокумент46 страницThe POWER of WHEY & MCT For Critically Ill PatientsBayu Residewanto PutroОценок пока нет

- Nipple Piercing Information - What To Know FAQsДокумент24 страницыNipple Piercing Information - What To Know FAQssiete100% (1)

- Bonviva Is A HERO 2015Документ36 страницBonviva Is A HERO 2015drgayuhОценок пока нет

- Retired Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) Indicators: No. 280 January 2015Документ17 страницRetired Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) Indicators: No. 280 January 2015Cornwall and Isles of Scilly LMCОценок пока нет

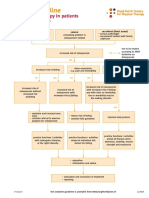

- Dutch Osteoporosis Physiotherapy FlowchartДокумент1 страницаDutch Osteoporosis Physiotherapy FlowchartyohanОценок пока нет