Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Big Food, Food Systems, and Global Health: Essay

Загружено:

John CitizenОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Big Food, Food Systems, and Global Health: Essay

Загружено:

John CitizenАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Essay

Big Food, Food Systems, and Global Health

David Stuckler1,2*, Marion Nestle3,4

1 Department of Sociology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2 Department of Public Health & Policy, London School of Hygiene & Tropical

Medicine, London, United Kingdom, 3 Department of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health, New York University, New York, New York, United States of America,

4 Department of Nutritional Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, United States of America

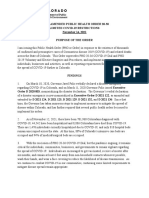

This article was commissioned for the place of small producers but an oligopoly. trition—to local partners [24]. The extent

PLoS Medicine series on Big Food that What people eat is increasingly driven by a of these benefits is debatable, however, in

examines the activities and influence of the few multinational food companies [12]. view of negative effects on farmers and on

food and beverage industry in the health Virtually all growth in Big Food’s sales domestic producers and food prices [25].

arena. occurs in developing countries [13] (see

Figure 1). The saturation of markets in Public Health Response to Big

As the PLoS Medicine series on Big Food developed countries [14], along with the Food: A Failure to Act

(www.ploscollections.org/bigfood) kicks lure of the 20% of income people spend on

off, let’s begin this Essay with a blunt average on food globally, has stimulated Public health professionals have been

conclusion: Global food systems are not Big Food to seek global expansion. Its rapid slow to respond to such nutritional threats

entry into markets in low- and middle- in developed countries and even slower

meeting the world’s dietary needs [1].

income countries (LMICs) is a result of still in developing countries. Thanks to

About one billion people are hungry, while

mass-marketing campaigns and foreign insights from tobacco company docu-

two billion people are overweight [2].

investment, principally through takeovers ments, we have learned a great deal about

India, for example, is experiencing rises in

of domestic food companies [15]. Trade how this industry sought to avoid or flout

both: since 1995 an additional 65 million

plays a minimal role and accounts for only public health interventions that might

people are malnourished, and one in five

about 6% of global processed food sales threaten their profits. We now have

adults is now overweight [3,4]. This

[15]. Global producers are the main reason considerable evidence that food and bev-

coexistence of food insecurity and obesity

why the ‘‘nutrition transition’’ from tradi- erage companies use similar tactics to

may seem like a paradox [5], but over-

tional, simple diets to highly processed undermine public health responses such

and undernutrition reflect two facets of

foods is accelerating [16,17]. as taxation and regulation [26,27,28,29],

malnutrition [6]. Underlying both is a

Big Food is a driving force behind the an unsurprising observation given the

common factor: food systems are not

global rise in consumption of sugar- flows of people, funds, and activities

driven to deliver optimal human diets

sweetened beverages (SSBs) and processed between Big Tobacco and Big Food. Yet

but to maximize profits. For people living

foods enriched in salt, sugar, and fat [13]. the public health response to Big Food has

in poverty, this means either exclusion

Increasing consumption of Big Food’s been minimal.

from development (and consequent food

products tracks closely with rising levels We can think of multiple reasons for the

insecurity) or eating low-cost, highly pro-

of obesity and diabetes [18]. Evidence failure to act [30]. One is the belated

cessed foods lacking in nutrition and rich

shows that SSBs are major contributors to recognition of the importance of obesity to

in sugar, salt, and saturated fats (and

childhood obesity [19,20], as well as to the burden of disease in LMICs [13]. The

consequent overweight and obesity).

long-term weight-gain, type 2 diabetes, 2011 Political Declaration of the United

To understand who is responsible for

and cardiovascular disease [21,22]. Stud- Nations High-Level Meeting on Prevention

these nutritional failures, it is first necessary

ies also link frequent consumption of and Control of Non-communicable Diseas-

to ask: Who rules global food systems? By and

highly processed foods with weight gain es (NCDs) recognized the urgent case for

large it’s ‘‘Big Food,’’ by which we refer to

and associated diseases [23]. addressing the major avoidable causes of

multinational food and beverage companies

Of course, Big Food may also bring death and disability [31], but did not even

with huge and concentrated market power

benefits—improved economic perfor- mention the roles of agribusiness and

[7,8]. In the United States, the ten largest

mance through increased technology and processed foods in obesity. Despite evi-

food companies control over half of all food

know-how and reduced risks of undernu- dence to the contrary, some development

sales [9] and worldwide this proportion is

about 15% and rising. More than half of

global soft drinks are produced by large Citation: Stuckler D, Nestle M (2012) Big Food, Food Systems, and Global Health. PLoS Med 9(6): e1001242.

doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001242

multinational companies, mainly Coca-

Cola and PepsiCo [10]. Three-fourths of Published June 19, 2012

world food sales involve processed foods, for Copyright: ß 2012 Stuckler, Nestle. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

which the largest manufacturers hold over a provided the original author and source are credited.

third of the global market [11]. The world’s

Funding: No specific funding was received for writing this article.

food system is not a competitive market-

Competing Interests: MN and DS are the guest editors of the PLoS Medicine series on Big Food.

Abbreviations: LMIC, low- and middle-income country; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverage

The Essay section contains opinion pieces on topics

of broad interest to a general medical audience. * E-mail: ds450@cam.ac.uk

Provenance: Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.

PLoS Medicine | www.plosmedicine.org 1 June 2012 | Volume 9 | Issue 6 | e1001242

Engaging with Big Food—Three has a legal mandate to maximize wealth

Views for shareholders. We also see no obvious,

established, or legitimate mechanism

We see three possible ways to view this through which public health professionals

debate. The first favors voluntary self- might increase Big Food’s profits.

regulation, and requires no further engage- Big Food attains profit by expanding

ment by the public health community. markets to reach more people, increasing

Those who share this view argue that people’s sense of hunger so that they buy

market forces will self-correct the negative more food, and increasing profit margins

externalities resulting from higher intake of through encouraging consumption of

risky commodities. Informed individuals, products with higher price/cost surpluses

they say, will choose whether to eat [28–31,37]. Industry achieves these goals

unhealthy foods and need not be subjected through food processing and marketing,

to public health paternalism. On this basis, and we are aware of no evidence for

UN secretary-general Ban Ki Moon urged health gains through partnerships in either

industry to be more responsible: ‘‘I espe- domain. Although in theory minimal

cially call on corporations that profit from processing of foods can improve nutrition-

selling processed foods to children to act al content, in practice most processing is

with the utmost integrity. I refer not only to done so to increase palatability, shelf-life,

food manufacturers, but also the media, and transportability, processes that reduce

marketing and advertising companies that nutritional quality. Processed foods are not

play central roles in these enterprises’’ [35]. necessary for survival, and few individuals

Similarly, the UK Health Minister recently are sufficiently well-informed or even

said: ‘‘the food and drinks industry should capable of overcoming marketing and cost

be seen, not just as part of the problem, but hurdles [38]. Big Food companies have

part of the solution…An emphasis on the resources to recruit leading nutritional

prevention, physical activity and personal scientists and experts to guide product

and corporate responsibility could, along- development and reformulation, leaving

side unified Government action, make a big the role of public health advisors uncer-

Figure 1. Growth of Big Food and Big difference’’ [36]. tain.

Tobacco sales in developing countries: The second view favors partnerships with

An example. Shaded blue line is developed

To promote health, industry would

countries, dashed grey line is developing industry. Public health advocates who hold need to make and market healthier foods

countries. Source: Passport Global Market this view may take jobs with industry in so as to shift consumption away from

Information Database: EuroMonitor Interna- order to make positive changes from within, highly processed, unhealthy foods. Yet,

tional, 2011 [12]. or actively seek partnerships and alliances such healthier foods are inherently less

doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001242.g001 with food companies. Food, they say, is not profitable. The only ways the industry

tobacco. Whereas tobacco is demonstrably could preserve profit is either to under-

harmful in all forms and levels of consump- mine public health attempts to tax and

agencies continue to view obesity as a tion, food is not. We can live without regulate or to get people to eat more

‘‘disease of affluence’’ and a sign of progress tobacco, but we all must eat. Therefore, this healthy food while continuing to eat

in combating undernutrition [32]. view holds that we must work with Big Food profitable unhealthy foods [33,39]. Nei-

A more uncomfortable reason is that to make healthier products and market ther is desirable from a nutritional

action requires tackling vested interests, them more responsibly. standpoint. Whereas industry support

especially the powerful Big Food compa- The third approach is critical of both. It for research might be seen as one place

nies with strong ties to and influence over recognizes the inherent conflicts of interest to align interests, studies funded by

national governments. This is difficult between corporations that profit from industry are 4- to 8-fold more likely to

terrain for many public health scientists. unhealthy food and public health collab- support conclusions favorable to the

It took five decades after the initial studies orations. Because growth in profit is the industry [40].

linking tobacco and cancer for effective primary goal of corporations, self-regula- Our second reason to support the

public health policies to be put in place, tion and working from within are doomed critical view has to do with the ‘‘precau-

with enormous cost to human health. to fail. Most proponents of this viewpoint tionary principle’’ [41]. Because it is

Must we wait five decades to respond to support public regulation as the only unclear whether inherent conflicts of

the similar effects of Big Food? meaningful approach, although some pro- interest can be reconciled, we favor

If we are going to get serious about such pose having public health expert commit- proceeding on the basis of evidence. As

nutritional issues, we must make choices tees set standards and monitor industry George Orwell put it, ‘‘saints should always

about how to engage with Big Food. performance in improving the nutritional be judged guilty until they are proved

Whether, and under what circumstances, quality of food products and in marketing innocent.’’ We believe the onus of proof is

we should view food companies as ‘‘part- the products to children. on the food industry. If food companies

ners’’ or as part of the solution to rising We support the critical view, for several can rigorously and independently establish

rates of obesity and associated chronic reasons. First, we find no evidence for an self-regulation or private–public partner-

diseases is a matter of much current alignment of public health interest in ships as improving both health and profit,

debate, as indicated by the diverse views curbing obesity with that of the food these methods should be extended and

of officials of PepsiCo and nutrition and beverage industry. Any partnership replicated. But to date self-regulation has

scientists [24,27,28,33,34]. must create profit for the industry, which largely failed to meet stated objectives

PLoS Medicine | www.plosmedicine.org 2 June 2012 | Volume 9 | Issue 6 | e1001242

[42,43,44,45,46,47], and instead has re- Public health professionals must recog- SSBs. The central aim of public health must

sulted in significant pressure for public nize that Big Food’s influence on global be to bring into alignment Big Food’s profit

regulation. Kraft’s decision to ban trans food systems is a problem, and do what is motives with public health goals. Without

fats, for example, occurred under pressure needed to reach a consensus about how to taking direct and concerted action to expose

of lawsuits [48]. If industry believed that engage critically. The Conflicts of Interest and regulate the vested interests of Big

self-regulation would increase profit, it Coalition, which emerged from concerns Food, epidemics of poverty, hunger, and

would already be regulating itself. about Big Food’s influence on the U.N. obesity are likely to become more acute.

We believe the critical view has much to High-Level Meeting on NCDs, is a good

offer. It is a model of dynamic and place to start [29,49]. Public health profes- Author Contributions

dialectic engagement. It will increase sionals must place as high a priority on

pressures on industry to improve health nutrition as they do on HIV, infectious Analyzed the data: DS. Wrote the first draft of

the manuscript: DS. Contributed to the writing

performance, and it will encourage those diseases, and other disease threats. They

of the manuscript: DS MN. ICMJE criteria for

who are sympathetic to the first or second should support initiatives such as restrictions authorship read and met: DS MN. Agree with

views to effect change from within large on marketing to children, better nutrition manuscript results and conclusions: DS MN.

food and beverage companies. standards for school meals, and taxes on

References

1. De Schutter O (2011) Report submitted by the 15. Regmi A, Gehlhar M (2005) Processed food trade 29. Stuckler D, Basu S, McKee M (2011) UN high

Special Rapporteur on the right to food. Geneva: pressured by evolving global supply chains. Am- level meeting on non-communicable diseases: An

United Nations. Available: http://www2.ohchr. berwaves: US Department of Agriculture. Avail- opportunity for whom? BMJ 343: d5336. doi:

org/english/issues/food/docs/A-HRC-16-49. able: http://www.ers.usda.gov/amberwaves/ 10.1136/bmj.d5336.

pdf february05/features/processedfood.htm 30. Stuckler D (2008) Population causes and conse-

2. Patel R (2008) Stuffed and starved: The hidden 16. Popkin B (2002) Part II: What is unique about the quences of leading chronic diseases: A compara-

battle for the world food system: Melville House. experience in lower- and middle-income less- tive analysis of prevailing explanations. Milbank

448 p. industrialised countries compared with the very- Quarterly 86: 273–326.

3. Doak C, Adair LS, Bentley M (2005) The dual high income countries? The shift in the stages 31. UN General Assembly (2011) Political declaration

burden household and nutrition transition para- of the nutrition transition differ from past of the High-level Meeting of the General

dox. Int J Obesity 29: 129–136. experiences! Public Health Nutr 5: 205–214. Assembly on the Prevention and Control of

4. Stein AD, Thompson AM, Waters A (2005) doi:10.1079/PHN2001295. Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs). New York:

Childhood growth and chronic disease: evidence 17. Hawkes C (2005) The role of foreign direct UN. Available: http://www.un.org/en/ga/

from countries undergoing the nutrition transi- investment in the nutrition transition. Public ncdmeeting2011/

tion. Matern Child Nutr 1: 177–184. Available: Health Nutri 8: 357–365. 32. Mitchell A (2011) Letter to National Heart Forum

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi? 18. Basu S, Stuckler, D McKee M, Galea G (2012) about ‘Priority actions for the NCD crisis’. In:

cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_ Nutritional drivers of worldwide diabetes: An Lincoln P, editor. London: UK DFID.

uids=16881898 econometric study of food markets and diabetes 33. Monteiro C, Gomes FS, Cannon G (2009) The

5. Caballero B (2005) A nutrition paradox – prevalence in 173 countries. Public Health snack attack. Am J Public Health 100: 975–

underweight and obesity in developing countries. Nutrition. In press. 981.

N Engl J Med 352: 1514–1516. 19. Maliv V, Schulze MB, Hu FB (2006) Intake of 34. Acharya T, Fuller AC, Mensah GA, Yahc D

6. Eckholm E, Record F (1976) The two faces of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: A (2011) The current and future role of the food

malnutrition. Worldwatch. Available: http:// systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 84: 274– industry in the prevention and control of chronic

www.worldwatch.org/bookstore/publication/ 288. diseases: The case of PepsiCo. In: Stuckler D,

worldwatch-paper-9-two-faces-malnutrition 20. Moreno L, Rodriguez G (2007) Dietary risk Siegel, K, . Sick Societies: Responding to the

7. Pollan M (2003) The (agri)cultural contradictions global challenge of chronic disease. Oxford:

factors for development of childhood obesity.

of obesity. New York Times. Available: http:// Oxford University Press.

Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 10: 336–341.

www.nytimes.com/2003/10/12/magazine/ 35. Ki-Moon B (2011) Remarks to the General

21. Hu F, Malik VS (2010) Sugar-sweetened bever-

12WWLN.html Assembly meeting on the prevention and control

ages and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

8. Brownell K, Warner KE (2009) The perils of of non-communicable disease. Geneva: UN. Avail-

Physiol Behav 100: 47–54.

ignoring history: Big Tobacco played dirty and able: http://www.un.org/apps/news/infocus/

22. Malik V, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Hu F

millions died. How similar is Big Food? Milbank sgspeeches/statments_full.asp?statID=1299

(2010) Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2

Quarterly 87: 259–294. 36. Lansley A (2011) 4th plenary meeting. Geneva: UN.

diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Available: http://www.ncdalliance.org/sites/

9. Lyson T, Raymer AL (2000) Stalking the wily

Circulation 121: 1356–1364. default/files/rfiles/Monday%20Sep%2019%203pm.

multinational: power and control in the US food

system. Agric Human Values 17: 199–208. 23. Pereira M, Kartashov AI, Ebbeling CB, Van pdf

10. Alexander E, Yach D, Mensah GA (2011) Major Horn L, Slattery ML, et al (2005) Fast food 37. Koplan J, Brownell KD (2010) Response of the

multinational food and beverage companies and habits, weight gain and insulin resistance in a 15- food and beverage industry to the obesity threat.

informal sector contributions to global food year prospective analysis of the CARDIA study. JAMA 304: 1487–1488.

consumption: Implications for nutrition policy. Lancet 365: 36–42. 38. Wansink B (2007) Mindless eating: Why we eat

Global Health 7: 26. 24. Yach D, Feldman ZA, Bradley DG, Khan M more than we think. Bantam Books.

11. Alfranca O, Rama R, Tunzelmann N (2003) (2010) Can the food industry help tackle the 39. Wilde P (2009) Self-regulation and the response to

Technological fields and concentration of inno- growing burden of undernutrition? Am J Public concerns about food and beverage marketing to

vation among food and beverage multinationals. Health 100: 974–980. children in the United States. Nutr Rev 67: 155–

International Food and Agribusiness Manage- 25. Evenett S, Jenny F (2011) Trade, competition, and 166.

ment Review 5. the pricing of commodities. Washington D.C.: 40. Lesser L, Ebbeling CB, Goozner M, Wypij D,

12. EuroMonitor International (2011) Passport Glob- Center for Economic Policy Research. Available: Ludwig DS (2008) Relationship between funding

al Market Information Database: EuroMonitor http://www.voxeu.org/reports/CEPR-CUTS_ source and conclusion among nutrition-related

International. report.pdf scientific articles. PLoS Med 4: e5. doi:10.1371/

13. Stuckler D, McKee M, Ebrahim S, Basu S (2012) 26. Chopra M, Darnton-Hill I (2004) Tobacco and journal.pmed.0040005.

Manufacturing Epidemics: The Role of Global obesity epidemics: Not so different after all? BMJ 41. Raffensperger C, Tickner J (1999) Protecting

Producers in Increased Consumption of Un- 328: 1558–1560. public health and the environment: implementing

healthy Commodities Including Processed Foods, 27. Ludwig D, Nestle M (2008) Can the food industry the precautionary principle. Washington D.C.:

Alcohol, and Tobacco. PLoS Med 6: e 1001235. play a constructive role in the obesity epidemic? Island Press.

doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001235. JAMA 300: 1808–1811. 42. Lewin A, Lindstrom L, Nestle M (2006) Food

14. Hawkes C (2002) Marketing activities of global 28. Wiist W (2011) The corporate playbook, health, industry promises to address childhood obesity:

soft drink and fast food companies in emer- and democracy: The snack food and beverage Preliminary evaluation. J Public Health Policy 27:

ging markets: A review. Geneva: World Health industry’s tactics in context. In: Stuckler D, 327–348.

Organization. Available: http://www.who.int/ Siegel, K, editor. Sick Societies: responding to 43. Lang T (2006) The food industry, diet, physical

hpr/NPH/docs/globalization.diet.and.ncds. the global challenge of chronic disease. Oxford: activity and health: A review of reported com-

pdf Oxford University Press. mitments and prctice of 25 of the world’s largest

PLoS Medicine | www.plosmedicine.org 3 June 2012 | Volume 9 | Issue 6 | e1001242

food companies. London: Oxford Health Alli- 46. Campbell D (2012) High street outlets ignoring York. Available: http://www.nytimes.com/

ance. guidelines on providing calorie information. The 2004/04/09/us/lawyers-shift-focus-from-big-

44. Sharma L, Teret SP, Brownell KD (2010) The Guardian. London. Available: http://www. tobacco-to-big-food.html

food industry and self-regulation: Standards to guardian.co.uk/business/2012/mar/15/high- 49. Conflicts of Interest Coalition (2011) Statement of

promote success and to avoid public health street-guidelines-calorie-information Concern.

failures. Am J Public Health 100: 240–246. 47. Hawkes C, Harris JL (2011) An analysis of the

45. Bonell C, McKee M, Fletcher A, Haines A, content of food industry pledges and marketing to

Wilkinson P (2011) The nudge smudge: misrepre- children. Public Health Nutr 14: 1403–1414.

sentation of the ‘‘nudge’’ concept in England’s 48. Zernike K (2004) Lawyers shift focus from Big

public health White Paper. Lancet 377: 2158–2159. Tobacco to Big Food. New York Times. New

PLoS Medicine | www.plosmedicine.org 4 June 2012 | Volume 9 | Issue 6 | e1001242

Вам также может понравиться

- Combat StressДокумент94 страницыCombat StressClaudia Maria Ivan100% (1)

- Fractures NoteДокумент31 страницаFractures NoteNoor AlblushiОценок пока нет

- Bleeding During Pregnancy and Nursing Care PlanДокумент17 страницBleeding During Pregnancy and Nursing Care PlanLizcelle Bihasa86% (7)

- 12 Week ProgramДокумент45 страниц12 Week ProgramCow SapiОценок пока нет

- Global Health Issues PPДокумент91 страницаGlobal Health Issues PPRitaОценок пока нет

- XA6 - Emergency Provision Workbook 2020 v0 - 5 - CKДокумент35 страницXA6 - Emergency Provision Workbook 2020 v0 - 5 - CKguyОценок пока нет

- An Atlas of Radiology of The Traumatized Dog and CatДокумент566 страницAn Atlas of Radiology of The Traumatized Dog and CatDenise Gomes de MeloОценок пока нет

- Anti ParasiteДокумент4 страницыAnti ParasiteVörös Bálint100% (1)

- Intentional InjuriesДокумент30 страницIntentional InjuriesZyryx BartolomeОценок пока нет

- Drugs and DosagesДокумент40 страницDrugs and DosagesGeraldine Marie Salvo100% (1)

- Food and Nutrition Biotechnology: UNU-IAS ReportДокумент36 страницFood and Nutrition Biotechnology: UNU-IAS Reportthanh_hai2014Оценок пока нет

- Milk TexturingДокумент2 страницыMilk TexturingJohn CitizenОценок пока нет

- Guidelines For Contemporary Air-Rotor StrippingДокумент6 страницGuidelines For Contemporary Air-Rotor StrippingGerman Cabrera DiazОценок пока нет

- Big Food, Food Systems, and Global HealthДокумент4 страницыBig Food, Food Systems, and Global HealthSandra MianОценок пока нет

- Mialon PLoSGPH Decolonisation Healthy Diets 2023Документ3 страницыMialon PLoSGPH Decolonisation Healthy Diets 2023Cesar PerillaОценок пока нет

- 1.1 Primary Health Care and NutritionДокумент5 страниц1.1 Primary Health Care and NutritionEmilyBaqueОценок пока нет

- JENKINS 2021 - Impacts of The 2008 Great Recession On Dietary IntakeДокумент20 страницJENKINS 2021 - Impacts of The 2008 Great Recession On Dietary IntakeNadyr Escovar NetoОценок пока нет

- Introduction Large-Scale Fortification, An ImportantДокумент5 страницIntroduction Large-Scale Fortification, An ImportantMuhitAbirОценок пока нет

- Zobel EH. Global Changes in Food Supply and Obesity Epidemic. 2016Документ7 страницZobel EH. Global Changes in Food Supply and Obesity Epidemic. 2016Nathalia MoraОценок пока нет

- GE 3 Chapter 6 Lesson 2 Global Food SecurityДокумент20 страницGE 3 Chapter 6 Lesson 2 Global Food Securityjuliet maeОценок пока нет

- Silver Linings: Silver Linings: Silver Linings: Silver Linings: Silver LiningsДокумент4 страницыSilver Linings: Silver Linings: Silver Linings: Silver Linings: Silver Liningscklcat1437Оценок пока нет

- GE 3 Chapter VIIДокумент12 страницGE 3 Chapter VIIRyan SalipsipОценок пока нет

- Obesity As Collateral Damage: A Call For Papers On The Obesity EpidemicДокумент3 страницыObesity As Collateral Damage: A Call For Papers On The Obesity EpidemicSandeep KumarОценок пока нет

- GA - Right To FoodДокумент24 страницыGA - Right To FoodFbarrsОценок пока нет

- Policy Narratives On Food and Nutrition SecurityДокумент13 страницPolicy Narratives On Food and Nutrition SecurityInstitute of Policy StudiesОценок пока нет

- The Nutrition: ChallengeДокумент12 страницThe Nutrition: ChallengeFrancis Joseph C. ArongОценок пока нет

- Ints Obesity RevistaДокумент30 страницInts Obesity Revistaitza andradeОценок пока нет

- Food and Nutrition: Matters of Public Health: Imedpub JournalsДокумент3 страницыFood and Nutrition: Matters of Public Health: Imedpub JournalsAhmad IsmadiОценок пока нет

- Assignment 3 - Effectiveness of SGDs in Reducing NCDsДокумент10 страницAssignment 3 - Effectiveness of SGDs in Reducing NCDs6889mj8my9Оценок пока нет

- Double Burden of Malnutrition 3: SeriesДокумент14 страницDouble Burden of Malnutrition 3: SeriesFanantenana RAHOLIARIMANANAОценок пока нет

- General Assembly: Report Submitted by The Special Rapporteur On The Right To Food, Olivier de SchutterДокумент22 страницыGeneral Assembly: Report Submitted by The Special Rapporteur On The Right To Food, Olivier de SchutterN D Senthil RamОценок пока нет

- Pediatric Obesity Prevention Is Better ThanДокумент7 страницPediatric Obesity Prevention Is Better ThanyasminОценок пока нет

- Global Food SecurityДокумент6 страницGlobal Food Securitybugaspearl0Оценок пока нет

- Ijerph 14 01174Документ12 страницIjerph 14 01174Herdi PulungОценок пока нет

- 2020 Global Nutrition Report 2hrsskoДокумент168 страниц2020 Global Nutrition Report 2hrsskoAndi RahmadОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S2213434422000019 MainДокумент6 страниц1 s2.0 S2213434422000019 MainjvracuyaОценок пока нет

- Food Security and Nutrition - OECDДокумент4 страницыFood Security and Nutrition - OECDLouie BangugОценок пока нет

- MANDRILLA - BSCE 2D - Global-Food-SecurityДокумент5 страницMANDRILLA - BSCE 2D - Global-Food-SecurityJhomer MandrillaОценок пока нет

- The Food Industry Is Ripe For ScrutinyДокумент2 страницыThe Food Industry Is Ripe For ScrutinyMARIA CLAUDIA GARCES ELIASОценок пока нет

- HPI Emerging Health Issues 2006Документ10 страницHPI Emerging Health Issues 2006Terence FusireОценок пока нет

- 1.ESCIAdvHumBiol000-8472152 022112Документ4 страницы1.ESCIAdvHumBiol000-8472152 022112Mufidatul HelmiyahОценок пока нет

- 2020 Global Nutrition ReportДокумент168 страниц2020 Global Nutrition ReportPilar QuintanillaОценок пока нет

- Policy BriefДокумент3 страницыPolicy BriefIik PandaranggaОценок пока нет

- GN KeyMessages FoodCrises Covid19Документ2 страницыGN KeyMessages FoodCrises Covid19aleskuhОценок пока нет

- Foods 11 00227Документ22 страницыFoods 11 00227Ryan ArmolОценок пока нет

- Ijerph 16 01804 v2Документ13 страницIjerph 16 01804 v2Faith Ann Miguel TanОценок пока нет

- WEF New Frontiers of Nutrition 2023Документ44 страницыWEF New Frontiers of Nutrition 2023Lorena BelloОценок пока нет

- Nutrition Promotion: Tony WorsleyДокумент22 страницыNutrition Promotion: Tony WorsleyFitri AfriОценок пока нет

- Clinical Nutrition Education of Doctors and MedicalДокумент6 страницClinical Nutrition Education of Doctors and Medicalpure 97jkОценок пока нет

- Big FoodДокумент41 страницаBig FoodaptypoОценок пока нет

- Globalization and HealthДокумент18 страницGlobalization and HealthHala SoufiОценок пока нет

- Priority Nutrition Indicators For The Post-2015 Sustainable Development FrameworkДокумент1 страницаPriority Nutrition Indicators For The Post-2015 Sustainable Development FrameworkthousanddaysОценок пока нет

- Evolution Not Revolution: Nutrition and ObesityДокумент8 страницEvolution Not Revolution: Nutrition and ObesityahulОценок пока нет

- SUN Yemen - Issue 10 - Oct 2021Документ7 страницSUN Yemen - Issue 10 - Oct 2021Mohammed AlmagbashiОценок пока нет

- Global Challenges - 2017 - Gillespie - Agriculture Food Systems and Nutrition Meeting The ChallengeДокумент12 страницGlobal Challenges - 2017 - Gillespie - Agriculture Food Systems and Nutrition Meeting The ChallengeSabrina MartaОценок пока нет

- Foods: Food Security-A Commentary: What Is It and Why Is It So Complicated?Документ10 страницFoods: Food Security-A Commentary: What Is It and Why Is It So Complicated?Nia HumairaОценок пока нет

- The Global Obesity PandemicДокумент11 страницThe Global Obesity Pandemicmaddy.nestebyОценок пока нет

- Food Ingredients and Suplements - Is This The FutureДокумент2 страницыFood Ingredients and Suplements - Is This The FutureDonato CignoliОценок пока нет

- Salud Pública y NutriciónДокумент2 страницыSalud Pública y NutriciónANGELA AGUIRREОценок пока нет

- Anti-Obesity Effects of Polyphenol IntakeДокумент24 страницыAnti-Obesity Effects of Polyphenol IntakeHuman ResourcesОценок пока нет

- Ultra-Processed Foods and Food System Sustainability: What Are The Links?Документ29 страницUltra-Processed Foods and Food System Sustainability: What Are The Links?AngelaОценок пока нет

- Food Safety W07Документ7 страницFood Safety W07MelanieОценок пока нет

- TFG Alba Redon LagoДокумент42 страницыTFG Alba Redon LagoIswarya RajkumarОценок пока нет

- Children: Childhood Malnutrition: Time For ActionДокумент3 страницыChildren: Childhood Malnutrition: Time For ActionFauziah GiziОценок пока нет

- Nutrition, Agriculture and The Global Food System in Low and Middle Income CountriesДокумент4 страницыNutrition, Agriculture and The Global Food System in Low and Middle Income CountriesPattola OlaОценок пока нет

- Perspective: Mexico's Experience in Building A Toolkit For Obesity and Noncommunicable Diseases PreventionДокумент9 страницPerspective: Mexico's Experience in Building A Toolkit For Obesity and Noncommunicable Diseases PreventionSUSANA PEREZ CUTIÑOОценок пока нет

- Actions and Accountability: To Advance Nutrition & Sustainable DevelopmentДокумент201 страницаActions and Accountability: To Advance Nutrition & Sustainable DevelopmentLeandro SalazarОценок пока нет

- Samenvatting Cumulatief 1 Samenwerken LerenДокумент33 страницыSamenvatting Cumulatief 1 Samenwerken LerenJ. Raja (Diëtist in opleiding)Оценок пока нет

- ForesightReport PDFДокумент134 страницыForesightReport PDFTsiotas KostasОценок пока нет

- Phenolic Compounds Impact On Rheumatoid Arthritis, Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Microbiota ModulationДокумент39 страницPhenolic Compounds Impact On Rheumatoid Arthritis, Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Microbiota ModulationRobert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2013От EverandThe State of Food Insecurity in the World 2013Оценок пока нет

- UMich Decolonizing Public Health SyllabusДокумент15 страницUMich Decolonizing Public Health SyllabusJohn CitizenОценок пока нет

- UNSCN Nutrition 45Документ148 страницUNSCN Nutrition 45John CitizenОценок пока нет

- Search List of Contents:: Overview of The Health SystemДокумент10 страницSearch List of Contents:: Overview of The Health SystemJohn CitizenОценок пока нет

- Steps To Build Global Health CVДокумент7 страницSteps To Build Global Health CVJohn CitizenОценок пока нет

- Stop 1 Os Help LoanДокумент1 страницаStop 1 Os Help LoanJohn CitizenОценок пока нет

- Johann Vexo MUSOC 5 May 2017Документ2 страницыJohann Vexo MUSOC 5 May 2017John CitizenОценок пока нет

- The Lamentation PDFДокумент7 страницThe Lamentation PDFJohn CitizenОценок пока нет

- The Lord Is My Strength PDFДокумент8 страницThe Lord Is My Strength PDFJohn CitizenОценок пока нет

- Countryside in Figures 2019 Parañaque City PDFДокумент282 страницыCountryside in Figures 2019 Parañaque City PDFJaimee Ruth LiganОценок пока нет

- Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment: November 14 Public-Health Order UpdateДокумент9 страницColorado Department of Public Health and Environment: November 14 Public-Health Order UpdateMichael_Roberts2019Оценок пока нет

- Mustafa CV PDFДокумент22 страницыMustafa CV PDFMUSTAFA TEMEMIОценок пока нет

- 2005 Proverbs TOM SchizophreniaДокумент7 страниц2005 Proverbs TOM SchizophreniaKatsiaryna HurbikОценок пока нет

- SR.# Weight (KG) Height (FT) Age (Yrz) Others RecommendationsДокумент2 страницыSR.# Weight (KG) Height (FT) Age (Yrz) Others RecommendationsshaniОценок пока нет

- Building Occupational Safety and Health k3 Analysis of The Work Environment and Work DisciplineДокумент10 страницBuilding Occupational Safety and Health k3 Analysis of The Work Environment and Work Disciplineipraul167Оценок пока нет

- Discursive StudiesДокумент11 страницDiscursive StudiesSohag LTCОценок пока нет

- Body Image: Marika Tiggemann, Kristy HageДокумент7 страницBody Image: Marika Tiggemann, Kristy HageRachel VictorianaОценок пока нет

- Enhancing Communication To Improve Patient Safety.5Документ6 страницEnhancing Communication To Improve Patient Safety.5Ang Timotius Raymond AngkajayaОценок пока нет

- Assisting Delivery Name: - Grade: - Year and Section: - DateДокумент5 страницAssisting Delivery Name: - Grade: - Year and Section: - DateCrisia Jane LotaОценок пока нет

- Written Assignment Unit 2 - HS 2212Документ5 страницWritten Assignment Unit 2 - HS 2212bnvjОценок пока нет

- NURS FPX 6030 Assessment 6 Final Project SubmissionДокумент11 страницNURS FPX 6030 Assessment 6 Final Project Submissionzadem5266Оценок пока нет

- TNF-dental PulpДокумент3 страницыTNF-dental PulpNicolas PintoОценок пока нет

- Chapter One The History of BreathingДокумент5 страницChapter One The History of Breathingoiliver2011Оценок пока нет

- HeartДокумент12 страницHeartRebar photographyОценок пока нет

- Nupa BrochureДокумент1 страницаNupa BrochureLaboule KimozackОценок пока нет

- National Health Policy in India: Dr. Kanupriya ChaturvediДокумент38 страницNational Health Policy in India: Dr. Kanupriya ChaturvediRadhakrishnan TherivilaОценок пока нет

- Block-D FinalДокумент47 страницBlock-D FinalAnonymous 7IKdlmОценок пока нет

- Food Systems For ChildrenДокумент12 страницFood Systems For ChildrenPaulin koffiОценок пока нет

- Intermittent Positive Pressure BreathingДокумент12 страницIntermittent Positive Pressure BreathingHitesh RohitОценок пока нет