Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Are " Consumer Social Responsibility " and " Consumer Ethics " Concepts Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions

Загружено:

Peerzada BasimОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Are " Consumer Social Responsibility " and " Consumer Ethics " Concepts Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions

Загружено:

Peerzada BasimАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/319205537

Are " Consumer Social Responsibility " and " Consumer Ethics " Concepts

Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions

Article · June 2017

CITATIONS READS

0 321

3 authors, including:

Niray Tuncel

Hacettepe University

5 PUBLICATIONS 1 CITATION

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

consumer ethics View project

Multi-Criteria Decision Making View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Niray Tuncel on 21 August 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Are “Consumer Social Responsibility” and “Consumer Ethics” Concepts

Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions 35

Are “Consumer Social Responsibility” and

“Consumer Ethics” Concepts Interchangeable?

The Effect of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions1

Niray TUNÇEL2

Bahtışen KAVAK3

Aslı ÇİLLİOĞLU KARADEMİR4

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to measure whether Hofstede’s cultural di-

mensions influence the interchangeability of consumer social responsi-

bility (CSR) and consumer ethics (CE). The current study consists of two

steps; (1) A questionnaire, which comprises of socially responsible con-

sumer behavior scale (Roberts, 1996) and consumer ethics scale (Vitell

and Muncy, 1992) is conducted on 111 undergraduate students. Accord-

ing to the results of aforementioned data revealed the items with higher

factor loadings (cut-off value = .45). (2) A second questionnaire, which

comprises of these items and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (Yoo et al.,

2004) is conducted on 165 undergraduate students. The frequency analy-

sis showed that a majority of the respondents classified CE items as a CE

issue, CSR items as a CSR issue correctly; however, three CSR items are

misclassified as a CE issue. The logistic regression results demonstrated

1 This study was presented in 8th Annual London Business Research Conference.

2 Dr., Hacettepe University Department of Business Administration,

niraytuncel@gmail.com

3 Prof. Dr., Hacettepe University Department of Business Administration,

bahtisenkavak@gmail.com

4 Hacettepe University Department of Business Administration,

aslicoglu@hotmail.com

Geliş Tarihi / Received: 31.12.2016 Kabul Tarihi / Accepted: 03.04.2017

Tüketici ve Tüketim Araştırmaları Dergisi, Cilt 9 Sayı 1, Haziran 2017, 35-56.

36 Niray TUNÇEL / Bahtışen KAVAK / Aslı ÇİLLİOĞLU KARADEMİR

that power distance and individualism/collectivism are the predictors of

congruence between CSR and CE scale items.

Keywords: Consumer Social Responsibility, Consumer Ethics, Hofst-

ede’s Cultural Dimension

“Tüketici Sosyal Sorumluluğu” ve “Tüketici Etiği” Birbirlerine

İkame Eden Kavramlar mıdır? Hofstede’in Kültürel Boyutlarının

Etkisi

Öz

Çalışmanın amacı tüketici sosyal sorumluluğu (TSS) ve tüketici etiği

(TE) kavramlarının birbirlerinin yerine kullanılabilmesinde Hofstede’in

kültürel boyutlarının etkisinin olup olmadığını test etmektir. Bu çalışma

2 aşamadan oluşmaktadır: (1) 111 lisans öğrencisine sosyal sorumlu tü-

ketici davranışı ölçeği (Roberts, 1996) ve tüketici etiği ölçeğinin (Vitell

ve Muncy, 1992) yer aldığı bir anket uygulamıştır. Söz konusu veriye

göre daha yüksek faktör yüküne sahip ifadeler (eşik değer = .45) ortaya

çıkarılmıştır. (2) 165 lisans öğrencisine bu ifadelerin ve Hofstede’nin

kültürel boyutlarının (Yoo et al., 2004) yer aldığı ikinci bir anket uygu-

lanmıştır. Frekans analizi sonuçları katılımcıların çoğunluğunun TSS

ifadelerini doğru bir şekilde sosyal sorumluluk meselesi olarak ve TE

ifadelerini de doğru bir şekilde tüketici etiği meselesi olarak sınıflan-

dırdıklarını göstermektedir. Ancak, katılımcıların çoğu üç TSS ifadesini

tüketici etiği konusu olarak yanlış bir şekilde sınıflandırmıştır. Lojistik

regresyon sonuçları güç mesafesi ve bireycilik/toplulukçuluk boyutla-

rının, TSS ölçeği ifadelerinin yanlış bir şekilde tüketici etiği meselesi

olarak sınıflandırılmasında önemli etkileyenler olduğunu göstermekte-

dir.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Tüketici Sosyal Sorumluluğu, Tüketici Etiği, Hofs-

tede’in Kültürel Boyutları

Tüketici ve Tüketim Araştırmaları Dergisi

Are “Consumer Social Responsibility” and “Consumer Ethics” Concepts

Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions 37

Introduction

Social responsibility is known as an ‘obligation’ to act for society. It

is a kind of duty of every individual to take economy, ecosystems, etc.

into consideration. Ethics, on the other hand, is not an obligation. Bunge

(2012) explained ethics such as about the good (that is, what values and

virtues we should cultivate) and about the right (that is, what our moral

duties may be). Consumers’ ‘obligations’ and ‘right and wrongs’ are the

basics values for all societies. Consumer shapes consumerism which is

full of some obligations coming from laws and right and wrong coming

from the ethical values of that society consumption itself. So it should be

understood what is an obligation (social responsibility), and what is right

& wrong (ethics) or how much they are replaceable from the consumer

point of view within a specific culture.

Researchers have tried to determine the socially responsible and ethi-

cal behaviors of the consumers. However, it is still a point at issue that

which behaviors are related to social responsibility and which are related

to ethics due to a lack of explicit difference between these concepts. Ac-

cording to Fisher (2004), there are inconsistencies in the way these two

terms are used and defined. A behavior considered responsible might be

ethically neutral or unsound as well as an ethically dictated action might

be socially unacceptable in a given society (Robin and Reidenbach,

1987). Therefore, these inconsistencies make it difficult for consumers

to evaluate their behaviors or behavioral intentions ethically or responsi-

bly. Besides, culture is a significant factor influencing consumers’ ethical

decision making and behavior (Singhapakdi et al., 1994; Tavakoli et al.,

2003) and also socially responsible decision making and behavior; as

ethics is considered to be one of the dimensions of social responsibility

(Carroll, 1979; Devinney et al., 2006).

A well-known typology, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions: power distance,

uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, and masculinity/fem-

ininity, cover the main components of culture (Nakata and Sivakumar,

1996). Also, these dimensions are accepted to influence the ethical per-

spectives of the individuals (e.g. Armstrong, 1996; Lu et al., 1999; Vitell

Cilt 9 Sayı 1, Haziran 2017

38 Niray TUNÇEL / Bahtışen KAVAK / Aslı ÇİLLİOĞLU KARADEMİR

et al.,1993) so the social responsibility perspectives of them as ethics is

considered to be one of the dimensions of social responsibility.

As it is mentioned above, it is hard for consumers to recognize which

behaviors are associated with ethics and which are associated with social

responsibility. However, in consumer social responsibility and consumer

ethics scales, it is assumed that consumers are able to perceive the given

behaviors correctly as a consumer social responsibility issue or correctly

as a consumer ethics issue. At this point, a question comes to mind “Are

consumers able to correctly recognize the socially responsible and ethi-

cal behaviors?”, which has been an unnoticed issue in current literature.

From this point of view, the purpose of this study is to determine to what

extent behaviors are considered within the scope of social responsibility

and ethics and if any of them is evaluated interchangeable. Additionally,

how much of this interchangeability is explained by which of Hofstede’s

cultural dimensions is tested. For this purpose, a two-step research de-

sign is adopted. In the first step, a questionnaire consisting of socially re-

sponsible consumer behavior scale (Roberts, 1996) and consumer ethics

scale (Vitell and Muncy, 1992) is conducted on 111 undergraduate stu-

dents. With an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), higher factor loaded

items are revealed. In the second step, a second questionnaire with these

items and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (Yoo et al., 2004) is conducted

on 165 undergraduate students. The results indicated that power distance

and individualism/collectivism dimensions are the predictors of the per-

ceived interchangeability of the CSR and CE scales items.

In the light of the explanations made above, in this study firstly social

responsibility and ethics concepts are introduced and evaluated from the

consumer side. Then, the effect of culture on these concepts is discussed.

In research design section, two-step survey conducted to answer the re-

search questions in current study is explained in detail. Lastly, in line

with the results of the analysis, interchangeability of ethics and social

responsibility concepts are discussed along with Hofstede’s cultural di-

mensions and some recommendations for further researches are exhib-

ited.

Tüketici ve Tüketim Araştırmaları Dergisi

Are “Consumer Social Responsibility” and “Consumer Ethics” Concepts

Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions 39

Social Responsibility and Ethics

There is a debate in the literature on ethics and social responsibility (e.g.

Robin and Reidenbach, 1987; Fisher, 2004). On the one stream, ethics

and social responsibility are sometimes mutually inclusive so that ethi-

cal behavior may be considered as socially responsible behavior. Carroll

(1979; 1991) and Devinney et al. (2006) claim that ethics is one of the

dimensions of social responsibility besides economic, legal, and philan-

thropic dimensions. On the other stream, in a given society actions that

can be defined as social responsible may be ethically neutral or unsound.

Similarly, actions that would be dictated by moral philosophy could be

seen as socially unacceptable (Robin and Reidenbach, 1987) since so-

cial responsibility includes ‘obligation’, but ethics includes relativity as

‘right-wrong’ values. According to Fisher (2004), there are inconsisten-

cies in the way ethics and social responsibility are defined and used. A

behavior considered responsible might be ethically neutral or unsound

as well as an ethically dictated action might be socially unacceptable in

a given society (Robin and Reidenbach, 1987).

Besides, there is a lack of explicit difference between these concepts.

Therefore, it is not clarified that which behaviors are related to social

responsibility and which are related to ethics. Also, these inconsistencies

make it difficult for consumers to evaluate their behaviors or behavioral

intentions ethically or responsibly.

The number of discussion on social responsibility and ethics in market-

ing has increased and most of them have been descriptive (Robin and

Reidenbach, 1987) and mostly focus on the seller side of the exchange

relationship. Murphy and Laczniak (1981), after reviewing the research

in marketing ethics, state that vast majority of studies had examined eth-

ics relating to business or marketing situations, while only five percent

of the studies examined ethics in consumer situations. As the consumers

are the key participants in the business process and excluding them from

ethics issue can lead to an imperfect understanding or that process (Vitell

et al., 2001).

Cilt 9 Sayı 1, Haziran 2017

40 Niray TUNÇEL / Bahtışen KAVAK / Aslı ÇİLLİOĞLU KARADEMİR

Many marketers have considered social responsibility and ethics to be

significant issues within marketing field but the question is “how do the

actual consumers view these matters?” (Carrigan and Attalla, 2001).

Consumer Social Responsibility and Consumer Ethics

There are few different definitions for social responsibility of consum-

er with different concerns. Webster Jr. (1975: 188) defines the socially

conscious consumer “as a consumer who takes into account the public

consequences of his or her private consumption or who attempts to use

his or her purchasing power to bring about social change.” This defi-

nition is weakly focused on environmental context. The other studies,

(eg: Constantini and Hanf, 1972; Tognacci et al., 1972; Anderson et al.,

1974; Buttel and Flinn, 1978; Murphy, 1978) however, have clearly un-

derlined environmental concerns. For instance, in Buttel and Flinn’s

(1978) study, environmental awareness of households is measured; air

and water pollution issues are focused.

Besides, Roberts (1993: 140) added a social dimension to the social re-

sponsibility with the definition as “one who purchases products and ser-

vices perceived to have a positive (or less negative) influence on the

environment or who patronizes businesses that attempt to effect related

positive social change”. Similarly, Mohr et al. (2001: 47) defines the

socially responsible consumer behavior as “a person basing his or her

acquisition, usage, and disposition of products on a desire to minimize

or eliminate any harmful effects and maximize the long-run beneficial

impact on society”. As seen from the above definitions, consumer social

responsibility is environmental and society based.

As come to the measurement, many scales have been developed to meas-

ure the socially responsible consumer behavior. Firstly, a scale developed

by Berkowitz and Daniels (1964) and further tested by Berkowitz and

Lutterman (1968) adopting the scale of Gough et al. (1952) and Harris

(1957) measure individual’s traditional social responsibility. Therefore,

it can be expected that socially conscious individuals, whose orientations

are reflected in a variety of socially responsible behaviors, would expose

Tüketici ve Tüketim Araştırmaları Dergisi

Are “Consumer Social Responsibility” and “Consumer Ethics” Concepts

Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions 41

social consciousness in consumption decisions. The most comprehen-

sive work on socially responsible consumer behavior has been done by

Roberts (1993), who develops a 40-item scale using two dimensions:

societal and ecological concerns. In his further studies of Roberts (1995;

1996) shorter version of this scale (18-item) is used.

Consumer ethics is on the other hand; focus on “right” or “wrong” be-

liefs, attitudes and behaviors etc. in the purchasing process. According to

Hunt and Vitell (1986) the process starts when the individual perceives

a situation as having ethical content then; the next step is the perception

of various alternatives that can be followed to resolve the ethical prob-

lem. Once having the evoked set of alternatives, two kinds of evaluation

will take place: Deontological and teleological. In deontological evalua-

tion, the individual evaluates the intrinsic rightness or wrongness of the

behaviors implied by each alternative comparing the behaviors within

a group of deontological norms consisting of personal values, general

beliefs (honesty, stealing, cheating and etc.), issue specific beliefs, de-

ceptive advertising, and rules of behavior. The teleological evaluation

consists of the perceived consequences of each alternative for different

stakeholder groups, the probability that each consequence will arise to

each stakeholder group, the desirability or undesirability of each conse-

quence and the importance of each group.

Researchers have different approaches to measure consumer ethics.

Vitell and Muncy (1992) creates consumer ethics scale that consists of

some ethical judgements and has four dimensions named as actively

benefiting (at the expense of seller), passively benefiting (at the expense

of others), deceptive legal practices and no harm/indirect harm. These

dimensions have direct or indirect harm to the society can be considered

either as unethical or socially irresponsible. There are very specific be-

haviors that have ethical implications and one of them is ecologically

related consumption as in socially responsible behavior. Antil (1984),

for example, stated that the relationship between perceived consumer

effectiveness and ecological concern indicates the consumer’s lack of

belief that he can be effective in the reduction of pollution is indeed an

Cilt 9 Sayı 1, Haziran 2017

42 Niray TUNÇEL / Bahtışen KAVAK / Aslı ÇİLLİOĞLU KARADEMİR

effective deterrent to his becoming personally concerned about ecolog-

ical issues in consumption. And, this ecologically related consumer is

the socially conscious consumer who feels strongly that he/she can do

something about pollution and tries to consider the social impact of his/

her purchases (Webster Jr., 1975).

From the above discussion, both socially responsible consumer and con-

sumer ethics have social concerns that have some negative or positive

consequences for others. Therefore, it can be stated that again there is a

connection and differentiation between these two concepts.

Effect of Culture on the Discrimination of Consumer Ethics

and Consumer Social Responsibility

A group of individuals who share distinctive values, norms and concepts

form a specific culture. Culture is recognized as one of the most critical

variables influencing ethical decision-making process (Hunt and Vitell,

1986; Ralston et al., 1994; Singhapakdi et al., 1994). Differences in con-

sumer ethics may be due to cultural distinction (England, 1975; Hunt and

Vitell, 1986). That is to say, differences in the structure of the mind may

differ from one culture to another (Hofstede, 1991). Therefore, ethical

values are an important component of culture (Rawwas et al., 2005).

They determinate what is right and wrong within a society (Hofstede,

1980). Culture determines individuals’ values, and in accordance with

these values, their behaviors are formed (Rawwas, 2001).

In a similar manner cultural factors have an important effect on social

responsibility as well (Singhapakdi et al., 2001). In addition, culture af-

fects social responsibility through ethics which is considered to be a di-

mension of social responsibility (Carroll, 1979; Devinney et al., 2006).

So the present study investigates empirically the cultural effect on con-

sumer social responsibility and consumer ethics with the point of con-

sumer view.

The above explanations show that consumer social responsibility and

consumer ethics are used interchangeably. But the existing literature pro-

Tüketici ve Tüketim Araştırmaları Dergisi

Are “Consumer Social Responsibility” and “Consumer Ethics” Concepts

Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions 43

vides some evidence that they are different from the point of salesperson

or company views. This study promises to give some from the consumer

side which has a big gap should be filled out. Besides, how the cultural

differentiation influences the consumers’ classification of a behavior as

socially responsible or ethical dilemma will have tried to be explored.

Research Design

The purpose of the study is to find answer to the following research

question:

“How much of consumer social responsibility behavior and ethical be-

havior inter-changeability are explained by which of Hofstede’s cultural

dimensions?”

The sample of the first step is of 111; in the second step, the sample con-

sists of 165 business administration students aged between 18-24.

The research has been conducted in the following two steps:

Step 1:

In this step, it is attempted to determine the scale items that will be used

in the second step. To this end, participants responded a questionnaire,

which consists of consumers’ ethics scale (Vitell and Muncy, 1992) and

socially responsible consumer behavior scale (Roberts, 1996). Besides,

the items are converted into an active form from the passive form. That

is, instead of a statement that says “changing price-tags on merchandise

in a retail store”, it is stated as “I can change price-tags on merchandise

in a retail store” because in Roberts’ (1996) scale the statements give an

active role to the respondents. Therefore, compatibility between these

two scales is obtained in terms of the way the statements are expressed.

Five Point Likert Type scale is used to measure consumer ethics and

consumer social responsibility concepts.

Then, the item reduction by Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) is con-

ducted in order to pick the items, which have higher factor loadings.

Firstly, the appropriateness of the data for EFA is tested with KMO and

Cilt 9 Sayı 1, Haziran 2017

44 Niray TUNÇEL / Bahtışen KAVAK / Aslı ÇİLLİOĞLU KARADEMİR

Bartlett’s Test. For the social responsibility scale, it is found that KMO

Measure of Sampling Adequacy is .841 and Bartlett’s Test of Spheric-

ity is significant at .05 level (p = .000). For the consumer ethics scale,

it is confirmed that KMO Measure of Sampling Adequacy is .884 and

Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity is significant at .05 level (p = .000). With

these results, appropriateness of the data for EFA is verified. Then, with

Principal Component Analysis (PCA), each item’s factor loadings are

extracted in both social responsibility and ethics scales.

For the social responsibility scale, higher factor loading items related to

environment, recycling and company issues are taken; for the consumer

ethics scale, higher factor loading items related to each dimension that

is actively benefiting, passively benefiting, deceptive “legal” practicing

and no harm/indirect harm, are taken. The underlying reason of it is to

see if the consumers are able to perceive the items that refer to the differ-

ent situations, correctly as an ethical or a social responsibility issue. For

instance, in consumer ethics scale, only if the actively benefiting ethical

items were selected, the results would be limited for the classification of

actively benefiting ethical items correctly as an ethical issue or incorrect-

ly as a social responsibility issue. Thus, the perception of the consumers

for the other ethical issues would be underestimated.

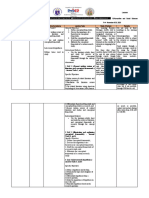

The items will be used in next step are given in Table 1 and Table 2 with

their factor loadings and descriptive statistics. The cut-off point for fac-

tor loadings is determined as .45 so the items that have factor loadings

more than .45 are selected.

Tüketici ve Tüketim Araştırmaları Dergisi

Are “Consumer Social Responsibility” and “Consumer Ethics” Concepts

Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions 45

Table 1. Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior Items (SRCBI)

Selected Items Factor Mean Std.

Loadings Dev.

1. Buying the products that cause the least environment

.757 4.50 .76

pollution

2. Always buying the products that cause the least harm to

.680 4.30 .90

other people

3. If possible, buying the product that has recycling package .679 4.25 .85

4. Giving effort to buy only the recycling products .546 3.09 .93

5. Using recycling box or in some way recycling some of the

.514 3.61 1.20

household trash

6. Not buying the products from the companies’ workers of

.512 3.88 1.09

which work under bad working conditions

7. Not buying the products from companies that discriminate

.459 4.11 .94

against any minority groups

KMO Measure of Adequacy: .841, χ²: 745.67, df: 136, p: .000, % of explained σ²: 61.41

Table 2. Consumer Ethics Items (CEI)

Factor Std.

Selected Items Mean

Loadings Dev.

1. Reporting a lost item as “stolen” to an insurance company

.674 4.38 .92

in order to collect the money

2. Downloading an album from internet instead of buying it .660 2.21 1.04

3. Returning an item after finding out that the same item is

.564 3.71 1.18

now on sale.

4. Observing someone shoplifting and ignoring it .522 4.14 1.05

5. Drinking a can of soda in a supermarket without paying

.505 4.08 1.21

for it

6. Using a long distance access code that does not belong to

.467 2.90 1.26

you

KMO Measure of Adequacy: .884, χ²: 1243.43, df: 253, p: .000, % of explained σ²: 62.54

Step 2:

The purpose of this step is to specify:

-If the consumer social responsibility and consumer ethics items spec-

ified in the first step are evaluated as interchangeable or discriminated

correctly.

Cilt 9 Sayı 1, Haziran 2017

46 Niray TUNÇEL / Bahtışen KAVAK / Aslı ÇİLLİOĞLU KARADEMİR

-If Hofstede’s cultural dimensions are the predictors of the interchange-

ability of the consumer social responsibility and consumer ethics items.

The questionnaire consists of two parts. In the first part, Hofstede’s

Cultural Dimensions are measured with CVSCALE (Yoo et al., 2004),

Turkish version of which is taken from Turhan’s (2009) master thesis.

The reason for selecting CVSCALE is that the dimensions of this scale

are accepted to be equivalent to Hofstede’s (1980) cultural dimensions.

Moreover, CVSCALE has Confucian Dynamism dimension that is not

included in this study. The items are placed with a Five Point Likert Type

scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. In the second part, the re-

spondents are asked if the items selected in the first step, are accepted as

consumer social responsibility or consumer ethics. Cronbach Alpha for

CVSCALE’s each cultural dimension is: .840 for uncertainty avoidance,

.861 for individualism/collectivism, .775 for masculinity/femininity,

.836 for power distance. Crobach Alpha for the scale as a whole is .827.

Data Analysis and Findings

First of all, a frequency analysis is conducted to see the number of par-

ticipants who are/are not able to discriminate the social responsibility

and ethics items revealed in the first step (given in Table 1 and Table 2)

correctly. If more than fifty percent of the participants classify a/an social

responsibility/ethics item incorrectly as an/a ethics/social responsibility

item, that item is admitted as interchangeable. As a result, it is found

that most of the social responsibility and ethics scale items are classified

correctly except three items, which are “Always buying the products that

cause the least harm to other people”, “Not buying the products from

companies that discriminate against minorities” and “Not buying the

products from the companies, workers of which work under bad working

conditions”. These items are considered to be ethical issues by a majority

of the respondents even if they are considered to be social responsibili-

ty issues in the literature. Therefore, it can be said that respondents are

more likely to misclassify the social responsibility items as consumer

ethics items.

Tüketici ve Tüketim Araştırmaları Dergisi

Are “Consumer Social Responsibility” and “Consumer Ethics” Concepts

Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions 47

The relevant table (Table 3) that exhibits frequencies is given below. The

bold items with their frequencies represent misclassified items by the

respondents.

Table 3. Frequencies of Social Responsibility and Consumer Ethics

Items Classification

Social

ITEMS Consumer Ethics

Responsibility

Buying the products that cause the least

137 28

environment pollution (SR)

Always buying the products that cause the least

81 84

harm to other people (SR)

If possible, buying the product that has recycling

143 22

package (SR)

Using recycling box or in some way recycling

142 23

some of the household trash (SR)

Giving effort to buy only the recycling products

142 23

(SR)

Not buying the products from companies that

39 126

discriminate against any minority groups (SR)

Not buying the products from the companies

workers of which work under bad working 48 117

conditions (SR)

Drinking a can of soda in a supermarket without

paying for it (CE)

11 154

Drinking a can of soda in a supermarket without

paying for it

Using a long distance access code that does not

22 143

belong to you (CE)

Reporting a lost item as “stolen” to an insurance

14 151

company in order to collect the money (CE)

Observing someone shoplifting and ignoring it

18 147

(CE)

Downloading an album from internet instead of

27 138

buying it (CE)

Returning an item after finding out that the same

26 139

item is now on sale (CE)

SR: Social responsibility

CE: Consumer Ethics

Cilt 9 Sayı 1, Haziran 2017

48 Niray TUNÇEL / Bahtışen KAVAK / Aslı ÇİLLİOĞLU KARADEMİR

After this step, a logistic regression was conducted for each misclassified

items to see whether this misclassification is explained by Hofstede’s

cultural dimensions, which are individualism/collectivism, masculinity/

femininity, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance. To examine if

there is multicollinearity between independent variables, VIF (≈1) and

tolerance (≈0.9) values are checked. It is revealed that there is not mul-

ticollinearity between independent variables. The results of the analysis

are shown in Table 4 below.

Table 4. Logistic Regression Analysis Results

Dependent binary Omnibus Test

Uncertainty Collectivism/ Masculinity/ Power

variables: of Model

avoidance İndividualism Femininity Distance

0: SR Coefficient

(B)/Sig. (B)/Sig. (B)/Sig. (B)/Sig.

1: CE Sig.

Always buying the

products that cause

.032** -.565/.040 .170/.451 .162/.336 .409/.033

the least harm to

other people (SR)

Not buying the

products from

companies that

discriminate .065*** .092/.764 .629/.017 -.227/262 -.188/.385

against any

minority groups

(SR)

Not buying the

products from the

companies workers

.403* 292/.325 -.333/.191 -.261/.153 .107/.596

of which work

under bad working

conditions (SR)

* Model is not significant at .10 level

**Model is significant at .05 level

***Model is significant at .10 level

First of all, as it is shown in Table X, misclassification of the item “Not

buying the products from the companies’ workers of which work under

bad working conditions” as a consumer ethics item, is not explained by

Tüketici ve Tüketim Araştırmaları Dergisi

Are “Consumer Social Responsibility” and “Consumer Ethics” Concepts

Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions 49

cultural dimensions. Besides, misclassification of the item “Always buy-

ing the products that cause the least harm to other people” is explained

by power distance dimension. Moreover, misclassification of the item

“Not buying the products from companies that discriminate against any

minority groups” is explained by collectivism/individualism dimension.

Discussion

The results of this study show that people are able to discriminate con-

sumer social responsibility and consumer ethics issues from each other.

However, There are three items that respondents are confused are “Not

buying the products from the companies’ workers of which work under

bad working conditions”, “Always buying the products that cause the

least harm to other people” “Not buying the products from companies

that discriminate against any minority groups”, which are social respon-

sibility issues but are considered as ethical issues by a majority of re-

spondents.

Besides, it is revealed that Hofstede’s cultural dimensions are effective

on explaining concept confusion between consumer social responsibility

and consumer ethics. “Always buying the products that cause the least

harm to other people” item’s misclassification is affected by power dis-

tance dimension and “Not buying the products from companies that dis-

criminate against any minority groups” item’s misclassification is affect-

ed by individualism/collectivism dimension.

In the frame of the abovementioned results, this study provides evidence

from the consumer side that social responsibility and ethics are perceived

as different issues. Although there is already a theoretical separation of

these concepts in literature, there is still an ongoing debate that social

responsibility and ethics concepts are mutually inclusive (Carroll, 1979,

1991; Devinney et al., 2006). On the other hand, actions that are regard-

ed as socially responsible may be ethically neutral or unsound and ac-

tions that are dictated ethically may be socially unacceptable (Robin and

Reidenbach, 1987). However, these inferences are based on the theoret-

ical approaches in which the consumer side is missing. Thus, the current

Cilt 9 Sayı 1, Haziran 2017

50 Niray TUNÇEL / Bahtışen KAVAK / Aslı ÇİLLİOĞLU KARADEMİR

study brings the perspective of the consumers and empirically verifies

the theoretical separation of these concepts from the consumer side.

Moreover, culture, as a determinative factor on individuals’ behav-

iors (Rawwas, 2001), structure of mind (Hofstede, 1991), ethical deci-

sion-making process (Hunt and Vitell, 1986; Ralston et al., 1994), social

responsibility attitude (Singhapakdi et al., 2001), is found to be effective

on the consumers’ misclassification of a behavior as a social responsi-

bility or an ethical issue. In this respect, the current study is the first to

highlight empirically that the consumer perception of what is a social

responsibility or an ethical issue is related to the cultural factors. There-

fore, a revision of the items considering the cultural differences may be

necessary not only for consumer social responsibility and consumer eth-

ics scales selected in this study but also for others, which would benefit

reliability and validity of the studies.

As it is mentioned above, power distance dimension is a predictor of the

misclassification of social responsibility items as an ethical issue. Power

distance at individual level refers to what extent an individual accepts

the unequal distribution of power in a society (Clugston et al., 2000).

Therefore, individuals with high-power distance scores are more likely

to be contented with the unequal distribution of power which is contra-

dicting for the long-term concerns of the society. For the corporate side,

in their study, Waldman et al. (2006) found that managers, who devalue

power distance, tend to express managerial skills related to social re-

sponsibility. Accordingly, for the consumer side, it may be suggested that

a high-power distance scored individual may be less likely to take the

issues in the scope of social responsibility. That might be the reason that

the social responsibility item “Always buying the products that cause the

least harm to other people” is misclassified as a consumer ethics item by

high-power distance scored consumers.

Moreover, it is found that the social responsibility item “Not buying the

products from companies that discriminate against any minority groups”

is misclassified as an ethical item, which is explained by individualism/

collectivism dimension, where collectivists are more likely to classify

Tüketici ve Tüketim Araştırmaları Dergisi

Are “Consumer Social Responsibility” and “Consumer Ethics” Concepts

Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions 51

the item as an ethical issue. As it is stated before, social responsibility is

identified as an obligation to act for society whereas ethics is more about

what is good or bad. Collectivism suggests cooperation, helpfulness and

consideration of group benefit. Also, collectivists have a motivation to

sacrifice individual interests if it is “good” for the group (Laroche et al.,

2001). It may be stated that collectivists are more likely to act for the

group benefit not because it is an obligation but because they believe it is

good for the group. Thus, collectivists tend to classify the item “Not buy-

ing the products from companies that discriminate against any minority

groups” as a consumer ethics issue.

Limitations of the Study

The sample of this study consist of Hacettepe University business ad-

ministrations students who are selected conveniently. Thus, the results

may differ for the students from other universities/departments and for

other populations.

Another issue is that in this study, consumer ethics is measured by Vitell

and Muncy’s (1992) scale and consumer social responsibility is meas-

ured Roberts’ (1996) socially responsible consumer behavior scale. The

results are limited to the consumer ethics and social responsibility clas-

sification of the respondents related to the items of these scales. Thus,

the respondents’ classification may change for different measurement

instruments.

Besides, the current study confirms that power distance and individual-

ism/collectivism dimensions are effective on the misclassification of the

social responsibility items as an ethical issue. However, these pioneering

results should be validated by future studies with broader and diversified

samples. Furthermore, Hoftsede’s cultural dimensions are measured by

the scale of Yoo et al. (2004) so the use of different ones may give dif-

ferent results.

Cilt 9 Sayı 1, Haziran 2017

52 Niray TUNÇEL / Bahtışen KAVAK / Aslı ÇİLLİOĞLU KARADEMİR

Recommendations for Further Research

This study selects the students of business administration departments

as the main population. These students are familiar with the consumer

ethics and consumer social responsibility concepts and to what behaviors

they are related to, from their courses. Therefore, they are able to dis-

criminate these two concepts. If a similar study is conducted to a differ-

ent main population, results would differ and maybe these two concepts

would not be discriminated.

Additionally, the effect of cultural dimensions on consumer social re-

sponsibility and consumer ethics vary for different countries. Therefore,

a similar study in a different country may give different results.

References

Anderson Jr, W. Thomas, Karl E. Henion, and Eli P. Cox III. (1974), “So-

cially vs. Ecologically Responsible Consumers”, AMA Combined

Conference Proceedings, Vol. 36, Spring and Fall, 304-311.

Antil, John H. (1984), “Socially Responsible Consumers: Profile and

Implications for Public Policy”, Journal of Macromarketing, 4(2),

18-39.

Armstrong, Robert W. (1996), “The Relationship Between Culture and

Perception of Ethical Problems in International Marketing” Jour-

nal of Business Ethics, 15(11), 1199-1208.

Berkowitz, Leonard and Louise R. Daniels. (1964), “Affecting the Sa-

lience of the Social Responsibility Norm: Effects of Past Help on

the Response to Dependency Relationships”, The Journal of Ab-

normal and Social Psychology, 68(3), 275-281.

Berkowitz, Leonard and Kenneth G. Lutterman. (1968), “The Traditio-

nal Socially Responsible Personality”, Public Opinion Quarterly,

32(2), 169-185.

Bunge, Mario (2012), Treatise on Basic Philosophy: Ethics: The Good

and The Right (Vol. 8), Springer Science & Business Media.

Tüketici ve Tüketim Araştırmaları Dergisi

Are “Consumer Social Responsibility” and “Consumer Ethics” Concepts

Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions 53

Buttel, Frederick M. and William L. Flinn (1978), “The Politics of En-

vironmental Concern the Impacts of Party Identification and Po-

litical Ideology on Environmental Attitudes”, Environment and

Behavior, 10(1), 17-36.

Carrigan, Marylyn and Ahmad Attalla (2001), “The Myth of the Ethical

Consumer-Do Ethics Matter in Purchase Behaviour?”, Journal of

Consumer Marketing, 18(7), 560-578.

Carroll, Archie B. (1979), “A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of

Corporate Performance”, Academy of Management Review, 4(4),

497-505.

Carroll, Archie B. (1991), “The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsi-

bility: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakehol-

ders”, Business Horizons, 34(4), 39-48.

Clugston, Michael, Jon P. Howell and Peter W. Dorfman (2000), “Does

Cultural Socialization Predict Multiple Bases and Foci of Commit-

ment?”, Journal of Management, 26(1), 5-30.

Costantini, Edmond and Kenneth Hanf (1972), “Environmental Concern

and Lake Tahoe:” A Study of Elite Perceptions, Backgrounds, and

Attitudes”, Environment and Behavior, 4(2), 209-242.

Devinney, Timothy M., Pat Auger, Giana Eckhardt and Thomas Birtch-

nell (2006), “The Other CSR: Consumer Social Responsibility”,

Leeds University Business School Working Paper, No. 15-04, 1-12.

Fischer, Josie (2004), “Social Responsibility and Ethics: Clarifying the

Concepts”, Journal of Business Ethics, 52(4), 381-390.

Friedman, Milton (1962), Capitalism and Freedom, Chicago: University

of Chicago Press.

Gough, Harrison G., Herbert McClosky and Paul E. Meehl (1952), “A

Personality Scale for Social Responsibility”, Journal of Abnormal

and Social Psychology, 47(1), 73-80.

Harris, Dale B. (1957), “A Scale for Measuring Attitudes of Social

Cilt 9 Sayı 1, Haziran 2017

54 Niray TUNÇEL / Bahtışen KAVAK / Aslı ÇİLLİOĞLU KARADEMİR

Responsibility in Children”, The Journal of Abnormal and Social

Psychology, 55(3), 322-326.

Hofstede, Geert (1980), Culture’s Consequences: International Differen-

ces in Work-Related Values. London: Sage

Hofstede, Geert, Gert Jan Hofstede and Michael Minkov (1991), Cul-

tures and Organizations: Software of The Mind, Vol. 2, London:

McGraw-Hill.

Hunt, Shelby D. and Scott Vitell (1986), “A General Theory of Marke-

ting Ethics”, Journal of Macromarketing, 6(1), 5-16.

Lu, Long-Chuan, Gregory M. Rose, and Jeffrey G. Blodgett (1999),

“The Effects of Cultural Dimensions on Ethical Decision Making

in Marketing: An Exploratory Study” Journal of Business Ethi-

cs, 18(1), 91-105.

Mohr, Lois A., Deborah J. Webb and Katherine E. Harris (2001), “Do

Consumers Expect Companies to Be Socially Responsible? The

Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Buying Behavi-

or”, Journal of Consumer Affairs, 35(1), 45-72.

Murphy, Patrick E. (1978), “Environmentally Concerned Consumers:

Demographic Dimensions”, Research Frontiers in Marketing: Di-

alogues and Directions, 316-320.

Murphy, P. and G. Laczniak (1981), “Marketing Ethics: A Review with

Implications for Managers, Educators and Researchers”, Ed. B.

M. Enis ve K. J. Roering, Inside Review of Marketing, Chicago:

AMA, 251–266.

Roberts, James A. (1995), “Sex Differences in Socially Responsible

Consumers’ Behavior”, Psychological Reports, 73(1), 139-148.

Roberts, James A. (1995), “Profiling Levels of Socially Responsible

Consumer Behavior: A Cluster Analytic Approach and Its Impli-

cations for Marketing”, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice,

3(4), 97-117.

Tüketici ve Tüketim Araştırmaları Dergisi

Are “Consumer Social Responsibility” and “Consumer Ethics” Concepts

Interchangeable? The Effect of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions 55

Roberts, James A. (1996), “Will the Real Socially Responsible Consu-

mer Please Step Forward?”, Business Horizons, 39(1), 79-83.

Rawwas, Mohammed YA. (2001), “Culture, Personality and Morality: A

Typology of International Consumers’ Ethical Beliefs”, Internatio-

nal Marketing Review, 18(2), 188-211.

Rawwas, Mohammed YA, Ziad Swaidan and Mine Oyman (2005),

“Consumer Ethics: A Cross-Cultural Study of the Ethical Beliefs

of Turkish and American Consumers”, Journal of Business Ethi-

cs, 57(2), 183-195.

Robin, Donald P. and R. Eric Reidenbach (1987), “Social Responsibility,

Ethics, and Marketing Strategy: Closing the Gap Between Concept

and Application”, The Journal of Marketing, 51(1), 44-58.

Singhapakdi, Anusorn, Kiran Karande, C. P. Rao and Scott J. Vitell

(2001), “How Important Are Ethics and Social Responsibility? - A

Multinational Study of Marketing Professionals”, European Jour-

nal of Marketing, 35(1/2), 133-153.

Singhapakdi, Anusorn, Scott J. Vitell and Orose Leelakulthanit (1994),

“A Cross-Cultural Study of Moral Philosophies, Ethical Percepti-

ons and Judgements: A Comparison of American and Thai Marke-

ters”, International Marketing Review, 11(6), 65-78.

Tavakoli, A. Assad, John P. Keenan and B. Cranjak-Karanovic (1003),

“Culture and Whistleblowing an Empirical Study of Croatian and

United States Managers Utilizing Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensi-

ons”, Journal of Business Ethics, 43(1-2), 49-64.

Tognacci, Louis N., Russell H. Weigel, Marvin F. Wideen and David TA

Vernon (1972), “Environmental Quality: “How Universal Is Public

Concern?”, Environment and Behavior, 4(1): 73-86.

Turhan, Ayça (2009), “Kültürün Tüketici Yenilikçiliği Üzerindeki Etkisi

Üzerine Bir Uygulama”, Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Ankara, Hacettepe

Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

Vitell, Scott J., Saviour L. Nwachukwu, and James H. Barnes (1993),

Cilt 9 Sayı 1, Haziran 2017

56 Niray TUNÇEL / Bahtışen KAVAK / Aslı ÇİLLİOĞLU KARADEMİR

“The Effects of Culture On Ethical Decision-Making: An Applica-

tion of Hofstede’s Typology.” Journal of Business Ethics, 12(10),

753-760.

Vitell, Scott J. and James Muncy (1992), “Consumer Ethics: An Empiri-

cal Investigation of Factors Influencing Ethical Judgments of the

Final Consumer”, Journal of Business Ethics, 11(8), 585-597.

Vitell, Scott J., Anusorn Singhapakdi and James Thomas (2001), “Consu-

mer Ethics: An Application and Empirical Testing of the Hunt-Vi-

tell Theory of Ethics”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(2),

153-178.

Waldman, David A., Mary Sully de Luque, Nathan Washburn, Robert

J. House, Bolanle Adetoun, Angel Barrasa, Mariya Bobina et al.

(2006), “Cultural and Leadership Predictors of Corporate Social

Responsibility Values of Top Management: A GLOBE Study of 15

Countries”, Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 823-

837.

Webster, Frederick E. (1975), “Determining the Characteristics of The

Socially Conscious Consumer”, Journal of Consumer Research,

2(3), 188-196.

Yoo, B., N. Donthu, and T. Lenartowicz (2004), “CVSCALE: The Fi-

ve-Dimensional Measure of Personal Cultural Values”, Working

Paper.

Tüketici ve Tüketim Araştırmaları Dergisi

View publication stats

Вам также может понравиться

- The Odyssey Unit PlanДокумент11 страницThe Odyssey Unit PlanAmanda Berry100% (1)

- An Ecological Approach For Social Work PracticeДокумент11 страницAn Ecological Approach For Social Work PracticeNeeraj DwivediОценок пока нет

- John Hopkins NursingДокумент10 страницJohn Hopkins NursingDaniel Avedon100% (1)

- Doehne, E. y Price, C. Stone Conservation. Getty. 2010Документ175 страницDoehne, E. y Price, C. Stone Conservation. Getty. 2010Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónОценок пока нет

- Writing A Research Report: Various FieldsДокумент7 страницWriting A Research Report: Various FieldsAyen DivineОценок пока нет

- Project Report On The Topic of Training and Development ProgramsДокумент80 страницProject Report On The Topic of Training and Development Programssatvinder100% (5)

- Viewing Responsible Consumption As A Personal ProjectДокумент12 страницViewing Responsible Consumption As A Personal ProjectSubhrajit PaulОценок пока нет

- Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J.Документ23 страницыKollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J.Ikhmatul Rizkya FitrianiОценок пока нет

- Ethical Consumer BehaviorДокумент19 страницEthical Consumer BehaviorRatish KakkadОценок пока нет

- 7 - Imr2018-Individual-LevelculturalcestylesДокумент39 страниц7 - Imr2018-Individual-LevelculturalcestylesFajrillah FajrillahОценок пока нет

- Hofstede Organization SudiesДокумент18 страницHofstede Organization SudiesErtunc YesilozОценок пока нет

- Mind The Gap Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are The Barriers To Pro Environmental Behavior PDFДокумент23 страницыMind The Gap Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are The Barriers To Pro Environmental Behavior PDFIdáliaePaulo LisboaОценок пока нет

- HAN & STOEL (2016) - Meta-Analytic Review of TPB - Consumo Socialmente ResponsávelДокумент14 страницHAN & STOEL (2016) - Meta-Analytic Review of TPB - Consumo Socialmente ResponsávelGabriel Horn IwayaОценок пока нет

- Zou2018 (If Needed About Prevention and Promotion Focus)Документ15 страницZou2018 (If Needed About Prevention and Promotion Focus)alaamohsenОценок пока нет

- Core ValuesДокумент9 страницCore ValuesTanyaОценок пока нет

- Consumer Identity Work As Moral Protagonism: How Myth and Ideology Animate A Brand-Mediated Moral ConflictДокумент17 страницConsumer Identity Work As Moral Protagonism: How Myth and Ideology Animate A Brand-Mediated Moral Conflictmgiesler5229Оценок пока нет

- Exploring The Potential (LSERO) PDFДокумент28 страницExploring The Potential (LSERO) PDFClaudio PidotoОценок пока нет

- SSRN Id3501759Документ36 страницSSRN Id3501759My TranОценок пока нет

- Lectura Complementaria 1 PDFДокумент12 страницLectura Complementaria 1 PDFjuansОценок пока нет

- Consumption, Lifestyle and Social Movements: Stefan Wahlen and Mikko LaamanenДокумент7 страницConsumption, Lifestyle and Social Movements: Stefan Wahlen and Mikko LaamanenponciОценок пока нет

- Welch, Warde 2015 - Theories of Practice and SustainableДокумент16 страницWelch, Warde 2015 - Theories of Practice and SustainableLuis Vargas FernandezОценок пока нет

- Economics, Ethics and Green Consumerism: December 2001Документ28 страницEconomics, Ethics and Green Consumerism: December 2001Jahred MulingbayanОценок пока нет

- Shove2010 Beyond The ABCДокумент14 страницShove2010 Beyond The ABCCamilo Andrés FajardoОценок пока нет

- Rediscovering The Individual: Potential Applications of Consumer Behavior Research To Public RelationsДокумент10 страницRediscovering The Individual: Potential Applications of Consumer Behavior Research To Public Relationslallan123Оценок пока нет

- An Ecological Approach For Social Work PracticeДокумент11 страницAn Ecological Approach For Social Work PracticeJona MempinОценок пока нет

- Culture Influence On Educational Public Relations Officers' Ethical Judgments: A Cross-National StudyДокумент14 страницCulture Influence On Educational Public Relations Officers' Ethical Judgments: A Cross-National StudyPapa ÁfricaОценок пока нет

- BRM Paper Findings 2Документ4 страницыBRM Paper Findings 2aakash.sachan.23mbОценок пока нет

- Hu Edoc DissertationДокумент7 страницHu Edoc DissertationHelpWithYourPaperCanada100% (1)

- Cambio SocialДокумент15 страницCambio SocialJesseniaОценок пока нет

- Margolin&Margolin Social Design Practice&Research 2006Документ8 страницMargolin&Margolin Social Design Practice&Research 2006Annie PedretОценок пока нет

- Understanding The Socialized Body-Libre PDFДокумент16 страницUnderstanding The Socialized Body-Libre PDFWishUpikОценок пока нет

- Green Social Work and SustainabilityДокумент12 страницGreen Social Work and SustainabilityRicardo TabladaОценок пока нет

- Dispelling The Myths About Consumption Behaviour: Kapow@etc - Mim.dkДокумент24 страницыDispelling The Myths About Consumption Behaviour: Kapow@etc - Mim.dkPedro SaadОценок пока нет

- Ethics in Qualitative ResearchДокумент18 страницEthics in Qualitative ResearchZul FiqryОценок пока нет

- J Occupat Organ Psyc - 2010 - Silvester - Organizational Culture Change An Inter Group Attributional AnalysisДокумент23 страницыJ Occupat Organ Psyc - 2010 - Silvester - Organizational Culture Change An Inter Group Attributional AnalysisAna Maria DumitrescuОценок пока нет

- Escholarship UC Item 08h9j3f4Документ30 страницEscholarship UC Item 08h9j3f4vecheverrycaОценок пока нет

- Environmental Education Research: To Cite This Article: Anja Kollmuss & Julian Agyeman (2002) : Mind The Gap: Why DoДокумент23 страницыEnvironmental Education Research: To Cite This Article: Anja Kollmuss & Julian Agyeman (2002) : Mind The Gap: Why DomamymeuОценок пока нет

- Consumer Involvement in Product Choice - A Demographic AnalysisДокумент18 страницConsumer Involvement in Product Choice - A Demographic AnalysisdsgoudОценок пока нет

- 10 17755-Esosder 827924-1404008Документ22 страницы10 17755-Esosder 827924-1404008smthОценок пока нет

- Cislaghi & Heise 2020 - Gender As A TermДокумент16 страницCislaghi & Heise 2020 - Gender As A TermRia AnggrainiОценок пока нет

- Applied and Professional EthicsДокумент18 страницApplied and Professional EthicsMarkmarilynОценок пока нет

- Reflexivity LitreviewДокумент19 страницReflexivity LitreviewSarithОценок пока нет

- Materialism and Its Associated ConceptsДокумент26 страницMaterialism and Its Associated ConceptsGAYATHIRI MUNIANDYОценок пока нет

- Bedford Et Al 2011Документ24 страницыBedford Et Al 2011ktiiti60Оценок пока нет

- On The Engagement With Social Theory in Food Studies: Cultural Symbols and Social PracticesДокумент19 страницOn The Engagement With Social Theory in Food Studies: Cultural Symbols and Social PracticesMehrun Nisa KhatoonОценок пока нет

- Full Paper THE CULTURAL DIMENSIONS OF HOFSTEDE IN THE MEXICANДокумент14 страницFull Paper THE CULTURAL DIMENSIONS OF HOFSTEDE IN THE MEXICANHarshraj ChavanОценок пока нет

- A "Social Model" of Design: Issues of Practice and Research: Victor Margolin and Sylvia MargolinДокумент7 страницA "Social Model" of Design: Issues of Practice and Research: Victor Margolin and Sylvia MargolinCarol HoffmannОценок пока нет

- Social Work ResearchДокумент4 страницыSocial Work ResearchMzee KodiaОценок пока нет

- UC Berkeley Previously Published WorksДокумент21 страницаUC Berkeley Previously Published WorksNorbaОценок пока нет

- Sex Personality and Sustainable Consumer BehaviourДокумент19 страницSex Personality and Sustainable Consumer BehaviourNgọc TrầnОценок пока нет

- Methods of Sustainability Research in The Social Sciences: January 2013Документ25 страницMethods of Sustainability Research in The Social Sciences: January 2013Annie KörmendiОценок пока нет

- Social Innovation For Social Cohesion. Findings On Communalities of Innovation From A New Transnational Study.Документ13 страницSocial Innovation For Social Cohesion. Findings On Communalities of Innovation From A New Transnational Study.Nesta100% (1)

- Sustainability 12 01349 v2Документ20 страницSustainability 12 01349 v2Ash LayОценок пока нет

- CSR & Hofstede's Cultural ValueДокумент17 страницCSR & Hofstede's Cultural ValueUzzal HaqueОценок пока нет

- ConsumerRights AnAssessmentofJusticeДокумент42 страницыConsumerRights AnAssessmentofJusticeLong TrầnОценок пока нет

- Dimensions of Social Rehabilitation A QualitativeДокумент21 страницаDimensions of Social Rehabilitation A Qualitativenjwmzq8nnmОценок пока нет

- The German Permaculture Community From A Community of Practice PerspectiveДокумент21 страницаThe German Permaculture Community From A Community of Practice PerspectivekarikambingОценок пока нет

- Do Paco Et Al., 2018Документ26 страницDo Paco Et Al., 2018Cristina NicolaeОценок пока нет

- Cross Cultural DifferencesДокумент32 страницыCross Cultural DifferencesKwan KaaОценок пока нет

- Leadership and Change ManagementДокумент6 страницLeadership and Change ManagementSai DОценок пока нет

- Consumers' Willingness To Buy Products With Environmental and Ethical Claims - The Roles of Social Representations and Social Identity PDFДокумент8 страницConsumers' Willingness To Buy Products With Environmental and Ethical Claims - The Roles of Social Representations and Social Identity PDF顏子傑Оценок пока нет

- 10 1016-j Annals 2006 01 006Документ20 страниц10 1016-j Annals 2006 01 006weal_h_nОценок пока нет

- Assessment1 Assignment M3 25%Документ3 страницыAssessment1 Assignment M3 25%John Benjamin DulayОценок пока нет

- Management: Functions of SalesДокумент45 страницManagement: Functions of SalesPeerzada BasimОценок пока нет

- Public Administration IMBAДокумент111 страницPublic Administration IMBAPeerzada BasimОценок пока нет

- Assignment IhrmДокумент4 страницыAssignment IhrmPeerzada BasimОценок пока нет

- Collective Bargaining V/s Workers Participation in Management (Industrial Relations)Документ3 страницыCollective Bargaining V/s Workers Participation in Management (Industrial Relations)Peerzada BasimОценок пока нет

- E-Commerce Model B2B: Name: Peerzada Mohammad Basim Roll No: 36Документ8 страницE-Commerce Model B2B: Name: Peerzada Mohammad Basim Roll No: 36Peerzada BasimОценок пока нет

- Bba Mba PDFДокумент10 страницBba Mba PDFPeerzada BasimОценок пока нет

- Mishra Mishra 20Документ18 страницMishra Mishra 20Peerzada BasimОценок пока нет

- University of Kashmir: Office of The Controller of ExaminationsДокумент1 страницаUniversity of Kashmir: Office of The Controller of ExaminationsPeerzada BasimОценок пока нет

- Semester IV: Unit I: Physiology IДокумент2 страницыSemester IV: Unit I: Physiology IPeerzada BasimОценок пока нет

- Export MarketingДокумент21 страницаExport MarketingPeerzada BasimОценок пока нет

- 4571Документ2 страницы4571Peerzada BasimОценок пока нет

- Oth 01Документ5 страницOth 01Malli ReddyОценок пока нет

- Food Studies A Level CourseworkДокумент8 страницFood Studies A Level Courseworkf5dvx95v100% (2)

- Research PaperДокумент33 страницыResearch PaperKaiОценок пока нет

- School Year: 2020-2021: Practical Research 2Документ4 страницыSchool Year: 2020-2021: Practical Research 2Laurence Plurad Arizabal67% (3)

- Why Should We Hire You?Документ12 страницWhy Should We Hire You?Andrew SmithОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan 2 Edss428 Unit PlanДокумент6 страницLesson Plan 2 Edss428 Unit Planapi-281291423Оценок пока нет

- Mental Toughness Footballer PDFДокумент20 страницMental Toughness Footballer PDFKamilah Che RamliОценок пока нет

- Concept Paper Guidelines PDFДокумент4 страницыConcept Paper Guidelines PDFCaine de LeonОценок пока нет

- On The Invisible in Architecture An Environment Behaviour Studies Perspective PDFДокумент8 страницOn The Invisible in Architecture An Environment Behaviour Studies Perspective PDFprovisori2650Оценок пока нет

- Research Methods - STA630 Power Point Slides Lecture 11Документ14 страницResearch Methods - STA630 Power Point Slides Lecture 11Sohail MerchantОценок пока нет

- SITHCCC018 Assessment Instruction v1.0Документ15 страницSITHCCC018 Assessment Instruction v1.0Muhammad ImranОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Collectivism Organisational CultureДокумент10 страницThe Effect of Collectivism Organisational CultureEdward ZiyachechaОценок пока нет

- Project Report On TQMДокумент81 страницаProject Report On TQMBharat Ahuja100% (1)

- Ch9 Using Experimental Control To Reduce Extraneous Variability PDFДокумент24 страницыCh9 Using Experimental Control To Reduce Extraneous Variability PDFjogradОценок пока нет

- Summer Internship ReportДокумент90 страницSummer Internship ReportVishwaMohanОценок пока нет

- Electronic Supply Chain Management - Some Latest Issues and PracticesДокумент5 страницElectronic Supply Chain Management - Some Latest Issues and PracticessanjeevОценок пока нет

- Animal Rights 2Документ7 страницAnimal Rights 2Kate20Оценок пока нет

- Philippine Qualifications FrameworkДокумент24 страницыPhilippine Qualifications FrameworkpusakalyeОценок пока нет

- 1.introduction To Science Technology and Society.Документ47 страниц1.introduction To Science Technology and Society.Snow BellОценок пока нет

- Decision MakingДокумент9 страницDecision MakingTalhaFarrukhОценок пока нет

- Eye Tracking VR ImotionsДокумент3 страницыEye Tracking VR ImotionsÁngrlОценок пока нет

- Chapter One: 1.1 Background To The StudyДокумент20 страницChapter One: 1.1 Background To The StudyChe DivineОценок пока нет

- Changed PGHRJCTДокумент71 страницаChanged PGHRJCTNishant SharmaОценок пока нет

- Commercial BankДокумент7 страницCommercial Bankchandrashekhar.verma4025Оценок пока нет

- Problem StatementДокумент4 страницыProblem StatementGaurav Pote50% (6)