Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

'The Appraisal Model of Coping: Assessment and Intervention Model For Occupational 'Therapy

Загружено:

AxeliaИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

'The Appraisal Model of Coping: Assessment and Intervention Model For Occupational 'Therapy

Загружено:

AxeliaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

'The Appraisal Model of

T

he ultimate goal of occupational therapy is to mini-

mize the handicapping effect of physical or psy-

Coping: An Assessment chological impairment or both. This is achieved

through restoration of the clients' functional skills, with

and Intervention Model the goal of enabling them to return to their normal life

roles. To this end, occupational therapists concentrate on

for Occupational the development or enhancement of the skills required to

perform these roles successfully (Reed & Sanderson,

'Therapy 1980). It is often assumed that skill development alone

will result in performance accomplishments. Why, then,

do patients of equal physical impairment and rehabilita-

tion potential not progress at the same pace- Why do

Marie Gage these same patients attain different levels of independent

function even when their goals are quite similar? One

possible explanation is that any two patients differ in their

Key Words: coping. intervention process, ability to cope with the effects of the disease process

occupational therapy (Mechanic, 1980). Therefore, it is important for occupa-

tional therapists to explore the influence of coping on

performance and to develop intervention models to maxi-

mize functioning.

This paper presents a new synthesis of the coping lit- Lazarus and Folkman (1984) defined coping as the

erature, the Appraisal Model of Coping. it is based

process through which a person manages the demands of

,largely on the theoretical concepts of the cognitive re-

.rational theory of coping and emotion (Lazarus & and emotions generated by the person-environment re-

Folkman, 1984, 1987) and social cognitive theory lationship. The relationship between the person anel his

(Bandura, 1977). The model provides a conceptual or her environment is drastically affected by the onset of a

template to guide occupational therapy intervention disease process as the patient struggles to adapt to the

with respect to assisting patients to cope better with the changes in his or her life. Occupational therapists assist

effects of their disease, it explains the influence of with this adjustment process by teaching the patient new

many factors that affect the person's ability to cope performance methods and by facilitating restoration of

with the disease process as well as the effect offeed- independent function. However, many other factors are

':Jack concerning the efficacy of the coping plan on fu- involved in determining whether a patient adapts well. If

ture coping efforts, occupational therapists are to improve rehabilitation out-

comes, they must fully understand these factors and de-

sign intervention strategies accordingly.

The purpose of this paper is to present the Appraisal

Model of Coping, which was developed after a review,

analysis, and synthesis of the coping literature. The mod-

el is presented as a means of guiding occupational thera-

pists as they assess and treat patients who are experienc-

ing difficulty coping with stressful Situations.

Definitions of Coping

The concepts of coping and adaptation are sometimes

used synonymously in the literature. White (1974) differ-

entiated between these terms in the follOWing way. Adap-

tation is seen as the master concept, which is superordi-

nate to three other terms: coping, mastery, and defense.

Coping is seen as "adaptation under relatively difficult

.'v1arie Gage, BSc(OT), is Director of Occupational Therapy, Vic- conditions" (p. 49). The automatic adaptations that we

:oria Hospital, London, Ontario, Canada, She is also a candi- make on a daily basis to meet the demands of a changing

date for the master's of science degree in occupational ther-

environment are thereby not included as coping

lPy from the University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario,

':::anada, (Mailing address: 42 Dundee Place, London, Ontario, strategies.

':::anada N6C 5£6) Lazarus and Folkman (1984) defined coping as the

process through which the individual manages the de-

rhis arlicle was accepted/or publication November 26, 1991, mands of and emotions generated by the person-

The American Journal 0/ Occupational Therapy 353

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930245/ on 09/16/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

environment relationship. They defined stressful situa- The cognitive relational theory of emotion and cop-

tions as particular relationships between people and their ing identifies two interacting cognitive appraisal pro-

environment that are appraised by the people as taxing or cesses that determine the reaction of an individual to the

exceeding their resources, thereby endangering their Stressor that he or she is facing (Lazarus & Folkman,

wel1-being. Such situations create a need to activate cop- 1987). Cognitive appraisal is defined as the process of

ing mechanisms to ensure a positive outcome. individual interpretation of what is happening in the envi-

Lazarus and Folkman's (1984) definition allows for ronment. Lazarus and Folkman (1984, 1987) discussed

individual variability in defining which situations will re- two kinds of cognitive appraisal. Primary appraisal de-

sult in a need to cope. It recognizes that the same situa- termines whether what is happening could be harmful,

tion wil1 be interpreted as stressful by some and non- threatening, challenging, beneficial, or of no importance

stressful by others. Their definition is the most widely to the individual. An occurrence (a person-environment

used in the coping literature. interaction) will not be a source of harm unless the peo-

ple who encounter it have motivational and cognitive

characteristics that make them vulnerable to the occur-

The Appraisal Model of Coping

rence. The quality and intensity of the emotion evoked by

Gergen (1982) stated, "Rather than viewing the search for the occurrence will vary depending on the interpretation

universals as a process of factual discovery, an objective made during primary appraisal. Lazarus and Folkman

assaying of 'what there is,' we must view it as the attempt (1987) now view this appraisal as an evaluation ofwheth-

to sustain a conceptual template while scanning immense er the person has anything at stake.

variations in human activity" (p. 55). He used as an exam- Secondary appraisal (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984,

ple the vast array of individual words that our language 1987) evaluates the physical, psychological, social, and

consists of, which can be put together in an infinite num- material resources available to cope with the event. If all

ber of ways. However, there are still rules of grammar that other factors are equal, the person who has a strong belief

provide a template to gUide the use of these words. What that he or she can handle an event is less likely to inter-

is needed to better understand coping is just such a tem- pret it as a threat.

plate: a set of rules that allows for individual variability but Primary and secondary appraisal are seen to influ-

at the same time guides the understanding of the coping ence one another but do not occur in any particular tem-

process. The Appraisal Model of Coping provides the poral order (Lazarus & Folkman, 1987). Both appraisal

required template. processes are equally important (Lazarus & Folkman,

1984). For this reason, the two appraisal processes are

represented in the Appraisal Model of Coping by two

Primary and Secondary Appraisal Processes intersecting circles.

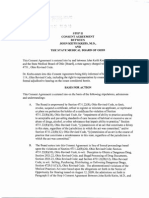

Figure 1 represents the Appraisal Model of Coping. It The "Influencing Factors" are all factors that affect

uses the cognitive relational theory of emotion and cop- the appraisal processes. These factors were identified

ing (Lazarus & Folkman, 1987) as a starting point and through a review of the literature. In many cases, a single

adds information from other authors to complete it. factor may affect both primary and secondary appraisal

processes in different ways. The following is a synopsis of

each factor and its likely effect on the primary and secon-

dary appraisal processes.

!

INFLUENCING FACTORS

Influencing Factors

PRIMARY

Temporal Factors

Temporal APPRAISAL

issues Temporal factors relevant to coping include the time of

Values and

beliefs life and the length of incubation of the threat. Lazarus and

Physiological

arousal Folkman (1984) stated that people have a sense of the

Age COPING PLAN normal life cycle (social clock theory) and that events are

Social suppon

Empowerment interpreted within this temporal context. Young widows

Efficacy are, according to these authors, typically more stressed

Novelty ( SECONDARY

Sex than older widows, and old mothers are more stressed

Mood APPRAISAL than young mothers, largely due to the absence of a sup-

Information

skills port network offriends facing similar stressors. However,

differentiation between desirable and undeSirable, as well

as controllable and uncontrollable, life events must be

made (Rook, Catalano, & Dooley, 1989). Rook et al. sur-

Figure 1. The Appraisal Model of Coping. veyed 500 randomly selected households and found little

354 April 1992, Volume 46, Number 4

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930245/ on 09/16/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

support for social clock theory. Although they found dif- punishment or as a means of strengthening one's inner

ferences in adjustment based on the age at which events resources, depending on the religious beliefs of ill per-

occurred, the differences did not follow the patterns pre- sons and their families. Park and colleagues studied a

dicted by social clock theory. For example, young widows sample of 83 undergraduates (44 Catholics and 39 Protes-

adjusted more easily than older widows. It is clear that tants). They anticipated that intrinsic religiousness would

timing of the event influences the reaction. What is not be a buffer when confronting uncontrollable life events.

yet clear is the nature of this influence. An unanticipated finding was that there were differences

The concept of incubation of threat was proposed by between the two religious categories with respect to the

Breznitz (1967) as the length of time between learning of effect of intrinsic religiousness on coping, anxiety, and

the threat and the occurrence of the threatening event. depression. Although this study must be interpreted with

Breznitz found that heart rate increased immediately after caution due to design limitations, it points out the value

learning of a threat, but then subsided with another, of exploring the effect of a person's religious background

more gradual, increase as the length of incubation period on his or her ability to cope with a stressor.

(Le., the time until the event occurred) increased. He also Maton (1989) found that bereaved parents who had

found that when given a choice of the length of incuba- reported high levels of spiritual support also reported

tion period, a significant number of subjects chose the more favorable well-being. The same effect was found in a

shortest incubation period. subsequent study for high-stress college students. The

Folkins (1970) questioned whether the incubation hypothesis that intrinsic religion acts as a buffer in stress-

period increased or decreased the stress response. Fol- ful situations was supported.

kins hypothesized that if enough time elapsed, people People who have an internal locus of control believe

would be able to activate effective coping strategies, thus that events are contingent upon their own behavior,

decreasing stress responses. In a study to test this whereas those with an external locus of control feel that

hypothesis, the length of incubation prior to receipt of a the same events are contingent upon luck, fate, chance,

shock was varied. The subjects' physiological responses or powerful others (Rotter, 1966). Persons with an inter-

were found to increase with a I-min wait, decrease with a nal locus of control are more likely to interpret ambigu-

3- to 5-min wait, and increase again with a 20-min wait. ous situations as being within their control. Therefore,

Folkins concluded that incubation time plays an impor- persons with an internal locus of control would be more

tant role in the determination of the degree of stress likely to believe that there were things they could do to

reaction and that, to a point, longer incubation periods alter the situation and decrease the threat. A sense of

were related to more effective coping. personal control is, therefore, likely to affect both the

The data regarding incubation of threat should be primary and secondary appraisal processes (Folkman,

interpreted with caution, as the studies relate to incuba- 1984). However, Folkman (1984) believed that the issue

tion of threat with respect to shocks. Whether the coping of internal versus external control is not as straightfor-

mechanisms for more personal types of life stressors cre- ward as Rotter postulated. She stated that there are situa-

ate the same reactions is not known. tions in which perceived control increases the threat felt

Both time of life and incubation of threat appear to by the person rather than causing it to decrease. For

affect the interpretation of the degree of threat, that is, example, consider a patient who is told he can control his

the primary appraisal process. However, the ability to malignancy by subjecting himself to chemotherapy. Exer-

draw on additional coping strategies is implicated by Fol- cising the control mechanism, that is, taking the chemo-

kins (1970) as a possible explanation for the decreased therapy, may control the malignancy but increase the

physiological stress reaction with longer incubation peri- stress to the patient's body.

ods. Therefore, an effect on the secondary appraisal proc- Diaz-Guerrero (1979) postulated that there is

ess is also possible. enough evidence to accept the existence of culture-based

differences in coping styles. His analysis of American and

Mexican coping styles showed that Americans cope with

Values and Beliefs

life stressors by actively modifying the physical, interper-

Personal values and beliefs affect the interpretation of sonal, and social environments. On the other hand, Mexi-

how threatening the event is (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). cans passively endure stressors with a strong bent toward

Included in this category are religious beliefs, beliefs of self-modification rather than changing the situation. He

personal control, and cultural beliefs (Lazarus & Folkman, stated that little is known about how these differences

1984). evolve but that mothers do reinforce different behaViors.

Religious beliefs are seen to influence both the pri- Regardless of the process of acquisition, the style differ-

mary and secondary appraisal processes (Park, Cohen, & ences are ingrained, according to Diaz-Guerrero, by the

Herb, 1990). The same event may take on different mean- age of 6 years.

ing for persons of different religious backgrounds. For Coping with disability has also been found to vary

example, the same serious illness may be interpreted as a according to the cultural background of the disabled per-

The American Journal 0/ Occupational Therapl' 355

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930245/ on 09/16/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

son and his or her family members (lngstad, 1988). Ing- cek, 1987). Older people were found to use more passive

stad analyzed data from studies of NOlwegian and Bots- techniques that are intended to control the emotions

wanan parents with disabled children. There were many created by the stressor (i.e., emotion-focused coping

differences in the interpretation of the meaning of the strategies), whereas younger people used more active

event to the parents. For example, in both groups, some techniques intended to alter the stressful situation (i.e.,

parents cited God's will as the reason for the birth of a problem-focused coping strategies). It is important to

disabled child. However, the connotation in which this point out that the authors also found significant differ-

explanation was used was quite different between the two ences between the old and young samples with respect to

cultures. The Norwegian parents viewed it as a punish- the sources of stressors. The younger group reported a

ment from God, whereas the Botswanan parents saw it as preponderance of stress coming from the areas of fi-

a positive expression of God's faith in their ability to nances and work. The older group's major stressors came

handle the event. under the categories of health, social issues, and home

It can be seen that cultural differences may affect maintenance. However, the differences in coping styles

both the primary and secondary appraisal processes. did not disappear when the differences in sources of

That is, culture can influence the perceived level of threat stressor were controlled. The authors hypothesized that

as well as limit or broaden the choice of coping strategies. the differences may be due to a difference in appraisal of

changeability. That is, older persons may perceive the

situation to be unchangeable and therefore react differ-

Physiological Arousal

ently than young people, who perceive that they can alter

In a study of active and passive coping techniques (i.e., a the situation. This would mean that the primary appraisal

reaction time test vs. toleration of a cold pressor cloth), process had been affected. However, because there were

Light (1981) found that active coping led to large sympa- also differences with respect to passive versus active cop-

thetically mediated heart rate and blood pressure in- ing strategies, one could also hypothesize that age affects

creases. Active coping techniques include those that al- the secondary appraisal process.

low the subjects to actively do something to reduce their

feelings of stress, whereas passive techniques only allow

Social Support

people to control their reaction to the stressor. Light

speculated that the observed increase in sympathetic ac- Exactly how the availability of social support enhances

tivity is due to inappropriate mobilization of adaptive coping ability is as yet unknown (Gore, 1978; Pearlin &

mechanisms. The purpose of these mechanisms is to Schooler, 1978; Thoits, 1986). A better understanding of

respond rapidly in order to prepare the body for fight or how social support reduces symptoms of anxiety and

flight. As mankind has evolved, the fight-or-flight re- despair must be developed to create effective interven-

sponse is no longer always appropriate in stressful situa- tion models (Thoits, 1986). Thoits defined social support

tions. In modern society, coping with a stressor tends to as the functions performed for a distressed person by

require mental rather than physical effort. significant others, such as family members, friends, co-

Obrist (1981) corroborated this finding. He reported workers, relatives, and neighbors.

a similar study that showed that passive coping leads to Gore (1978), in a classic study of social support,

activation of the parasympathetic system, which helps to looked at the effects of social support on rural and urban

relax the person, and active coping leads to activation of men who became unemployed when two plants shut

the sympathetic system, thereby increasing cardiovascu- down. She found the follOWing stages of adjustment: an-

lar output. tiCipation, termination, and readjustment. The rural

Bandura (1977) stated that the physiological arousal dwellers had, on average, more social support available to

that occurs in stressful situations has an informative value them. The results demonstrated that those who had good

concerning the person's ability to handle a stressful situa- social support systems reported fewer illness symptoms

tion. He stated that high states of arousal tend to debili- and suffered from fewer depressive symptoms than those

tate performance, whereas low states of arousal allow the with poor social support systems. Interestingly, the avail-

person to take action to handle the stressor. Physiological ability of social support had more of an effect on depres-

processes therefore affect the person's interpretation of sion than did the unemployment.

the level of threat and the selection of coping strategies. Thoits (1986), through a literature review, identified

three categories of coping: emotion-focused, problem-

focused, and perception-focused. Emotionjocused cop-

Age

ing strategies are seen to help control the emotional reac-

Folkman and Lazarus (1980) originally concluded that tion to the stressor (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

there were no age-related differences in coping style. This Problemjocused coping strategies intervene to change

finding has, however, been refuted by a subsequent, the person-environment relationship in a way that will

more in-depth study (Folkman, Lazarus, Pimley, & Nova- reduce the perceived threat (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

356 April 1992, Volume 46, Number 4

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930245/ on 09/16/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

Perceptionjocused strategies attempt to change the per- the instrumental behaviors needed to interact effectively

son's interpretation of the event. Pearlin and Schooler with others to procure resources.

(1978) identified this classification of strategies that were Persons with disabilities must often overcome feel-

later named by Thoits (1986). For example, if employees ings of dependency and powerlessness and gain, or re-

are ordered to do something that contravenes their ethi- gain, a sense of control and accomplishment. How this

cal standards, they may rationalize that the boss is really happens is not well understood or documented in the

the person who is being unethical. This effectively re- literature (Lord & Farlow, 1990). In an attempt to fill this

duces the threat and manages the situation. Void, Lord and Farlow interviewed persons who had been

Thoits (1986) conceptualized social support as cop- dependent and powerless. The kind of interventions that

ing assistance, because a comparison of social support these subjects found most helpful were personalized, in-

strategies and coping strategies revealed that there were teractive, and focused on reduction of dependency.

similar strategies in each category with similar objectives. Seemingly simple accomplishments, such as being able to

However, in the case of the social support strategies, the open a can, were symbolically empowering events in the

objective is reached with assistance of a support person. lives of many of the subjects of this study.

For example, the social support strategy of instrumental If a person does not feel empowered, then he or she

support parallels problem-focused coping in that both will not even attempt to engage in coping behavior

are aimed at changing or managing the troubled person- (Strong, 1989). He or she will instead wait for someone

environment relationship. In the case of instrumental else to intervene. Therefore, empowerment of the client

support, assistance is being given in the change or man- is predicted to affect the secondary appraisal process.

agement process, whereas with problem-focused coping, If clients are to be empowered through the treat-

the person is independently responsible for managing ment process, then the system must become client-

the stressor. The conclusion that social support is really driven, with the focus on the client's needs and abilities

coping assistance leads to the assumption that research (Strong, 1989). This concept is certainly not foreign to

into the kinds of coping strategies that are effective will occupational therapists; it represents a value that has

also be frUitful in determining what kind of social support long been held by the profession (yerxa, 1983), although

will be most effective. Conceptualization of social support it has not rypically been called empowerment.

as coping assistance leads to the prediction that social

support has a major effect on the primary appraisal pro-

cess. Having someone available to assist with the coping

E.!/lcacy

process would surely be a reassuring factor and may in Efficacy refers both to Bandura's (1977) concept of per-

fact decrease the level of perceived threat. ceived self-efficacy and to Rogers's (1983) concept of re-

If the person providing the social support is similar sponse efficacy Rogers (1983) believed that whether or

in sociocultural experience and has experience with the not a person acts to protect himself or herself from a

same stressor, the efficacy of social support is enhanced possible threat depends on the perceived magnitude of

(Thoits, 1986). This is evident in the proliferation of self- noxiousness of the event, the conditional probabiliry that

help groups, where persons who are experiencing the the event will occur provided that no adaptive activity is

same life stressors share ideas and provide moral support performed, and the perceived effectiveness of a coping

(i.e., Parents Without Partners; Stroke Recovery response that might avert the noxious event. This last

Association) . concept is referred to as response efficacy. If the person

The data regarding the positive influence of social did not believe that a specific coping strategy would be

support on coping abiliry are not conclusive. There is effective, then it is unlikely that he or she would imple-

some indication that social support may not be as benefi- ment the strategy. For example, if a smoker does not

cial as is widely assumed. Social support does not always believe that smoking negatively affects his or her health,

buffer the effect of uncontrollable factors, such as pover- then he or she will not qUit smoking.

ty, on coping ability (Singh & Pandey, 1990). We need The concept of perceived self-efficacy has its roots in

more research and analysis of the way in which social social cognitive theory that explains human behavior in

support and coping ability interact. terms of triadic reciprocality (Bandura, 1986). That is,

behaVioral, cognitive, and other personal factors and en-

vironmental events are interacting determinants of each

Empowerment

other. Professionals who develop programs within this

Rappaport (1984) defined empowerment as "the mecha- framework do not focus solely on behavior. Instead,

nism by which people, organizations, and communities changes in the environment, the person, and his or her

gain mastery over their lives" (p. 3). According to Dunst behavior are all facilitated with an expectation that a

(1988), empowerment necessitates facilitation of access change in one will produce a change in the others (Perry,

and control of needed resources, gaining of decision- Baranowski, & Parcel, 1990).

making and problem-solVing abilities, and acquisition of Self-efficacy refers to the person's judgment of

The American joumal oj' Occupational Therapy 357

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930245/ on 09/16/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

whether he or she is capable of performing a given task emotion-focused coping. Women reponed more health-

(Bandura, 1977). It is postulated that people are influ- related threats than men, and health-related threats re-

enced more by their perceptions of previous success then sulted in the use of emotion-focused coping. However,

by success itself. Bandura (1982,1986), working with peo- within the category of health threats, men and women

ple suffering from snake phobias and with cardiac pa- used emotion-focused coping equally. Had the source of

tients, found that increasing perceived efficacy led to stress not been adjusted, the authors may have errone-

higher performance accomplishments. To the extent that ously concluded that there were sex-based coping styles.

thiS is true, the concept of perceived self-efficacy is par- Therefore, it is necessary when studying sex differences

ticularly salient to the practice of occupational therapy. It to look at the differences in sources of stress before draw-

is highly possible that enhancement of perceived self- ing conclusions about coping styles.

efficacy may lead to improved occupational therapy In a subsequent study, sex differences were found to

outcomes. be minimal (Folkman et aI., 1987). Men used more self-

One must differentiate between outcome and effica- control strategies, and women used more positive

cy. Persons may believe that a specific behavior will lead reappraisal.

to a certain outcome, however, they will perform the In a study of 40 male and 37 female college students,

behavior only if they believe that they can perform the Houtman (1990) found few differences in coping style. Men

behavior (Bandura, 1977). A desirable outcome may, had higher aerobic fitness levels, and women sought more

therefore, fail to elicit performance attempts if the person support than men. When confronted with health problems,

does not feel capable of performing the required behav- women took action at an earlier stage than men.

ior. In the smoking example, if the person does not per- Sex is a significant correlate of psychological well-

ceive himself or herself to be capable of adhering to the being (Borden & Berlin, 1990). Women were found to be

program, then he or she may not even attempt the behav- more susceptible to psychological stress when confront-

ior. Thus, haVing a repertOire of coping strategies that the ed with the same stressor as men (i.e., being caregivers of

person believes he or she is able to perform contributes spouses with dementia), even though there was little

to his or her sense of self-efficacy. evidence of differences in the types of coping strategies

Efficacy, therefore, encompasses both the person's used. The question of why women are more susceptible

perception of his or her ability to carry out the activity and to psychological distress remains unanswered.

his or her belief that the recommended response will The effect of sex on the appraisal process is there-

bring the desired results. It follows that a coping response fore likely a minimal one. However, because the differ-

that persons feel unable to perform or that they believe to ence in psychological well-being is unexplained, we must

be ineffective if performed would not be considered in continue to explore the effect of sex on the outcome of

the secondary appraisal process as an available resource. coping efforts.

Novelty Mood

Experience with an event generally decreases the per- Saloveyand Birnbaum (1989) induced different moods to

ceived level of threat (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The an ill population of university students. They found that

amount of decrease in perceived threat depends a great the number of aches and pains experienced was signifi-

deal on the person's assessment of his or her historical cantly affected by negative mood states. Subjects who

success in dealing with the event, that is, with his or her were experiencing positive moods felt more able to carry

perceived self-efficacy (Bandura, 1982). out health-promoting and illness-alleviating behaviors.

The anticipatory increase in heart rate is greater However, this finding was not statistically significant. As

when the subject has had no experience with the aversive this relates to perceived self-efficacy, mood is expected to

event (Obrist, 1981). Thus, even at a physiological level, affect secondary appraisal.

novelty enhances the stress reaction.

Information

Sex

Sufficient information is necessary if people are to choose

In a study of 100 subjects, Folkman and Lazarus (1980) an effective strategy to deal with the stressor or to assess

found that women reported more health and family stres- the level of threat accurately. A person facing a financial

sors than men, whereas men reported more work stres- crisis needs to know about all the community resources

sors than women. Men also reported the use of more available to assist him or her. If he or she is, for example,

problem-focused coping strategies in situations that had unaware of available financial counseling services, then

to be accepted. Men and women varied little with respect he or she would be unable to choose financial counseling

to their interpretation of events (primary appraisal), and as an alternative; yet, it may be the alternative that would

there were no sex differences with respect to the use of be most successful.

358 April 1992, Volume 46, Number 4

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930245/ on 09/16/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

Some studies evaluated by Suls and Fletcher (1985) creased coping efforts decreased the resultant stress reac-

looked at the effect of information about the forthcoming tion. The authors hypothesized that vocational stressors

stressor versus no information. They found that subjects may be more outside of the person's control, thus coping

who received information coped significantly better than efforts were ineffective. Singh and Pandey (1990) also

subjects who received no information. found that people use multiple, complementary strate-

gies when dealing with a stressor.

Smith, Patterson, and Grant (1990) defined avoidant

Skills

coping strategies as self-blame, wishful thinking, and

If a person is to cope effectively with a situation, then he avoidance. They found that within a geriatric sample, the

or she must have the skills required to carry out the use of these avoidant strategies was associated with a

coping plan (Bandura, 1977; Kennett, Bleasdale, Pitt, & higher level of psychological stress 4 months later. How-

Blom, 1990). Identification of the most effective means of ever, the type of event being coped with was not con-

coping with a stressor is the first step in effective coping. trolled and may explain this effect. As noted earlier, when

However, the ability to plan a coping strategy is inconse- the source of the stressor is controlled, differences in

quential if the person does not possess the skills neces- coping techniques are eliminated (Folkman & Lazarus,

sary to carry out the plan successfully. In addition, coping 1980).

strategies that require skills that the person does not Bombardier, D'Amico, and Jordan (1990) studied a

possess will not be identified during the secondary ap- group of 101 admitted patients with combined medical

praisal process. This may result in an increase in the level and psychiatric conditions. An admission criterion was

of threat appraised during the primary appraisal process. that the patient's level of dysfunction must be out of

Occupational therapy is "concerned with proViding func- proportion to observable physiological or structural ab-

tional experiences which enhance self-worth in a way normalities. The subjects filled in questionnaires regard-

which assists individuals to reach their potential" (Health ing their ways of coping, their functional status, level of

and Welfare Canada, 1983, p. 8). As such, occupational depression, and symptom severity. The admitting physi-

therapists are in a position to teach effective coping skills. cian rated the physiological or structural abnormalities on

a 6-point scale. An emotion-focused style of coping, con-

sisting of wishful thinking, self-blame, and avoidance, pre-

The Coping Plan

dicted poorer adjustment to the illness. These three cop-

The intersection of the primary and secondary coping ing styles together explained 33% of the variance in

circles represents the formulation of the coping plan. psychosocial functioning. It was also found that the belief

Coping, within the framework of this model, is viewed as that one could change the condition or that one must

haVing two primary functions (Lazarus & Folkman, 1987). accept the condition both lead to more problem-focused

Coping can intervene to alter the emotional reaction coping. Patients who believe that they must avoid doing

(emotion-focused coping) or to change the situation things that they wish to do are prone to more emotion-

(problem-focused coping). Strategies that alter the mean- focused ways of coping, greater depression, and poorer

ing of the event (perception-focused coping) are not spe- psychosocial adjustment. This study is correlational in

cifically named by Lazarus and Folkman but appear to be nature, and the results must not be interpreted as a cause-

considered emotion-focused strategies. and-effect relationship. However, this information can be

Both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping used to assist in the design of remediation programs that

strategies are used in virtually every situation (Folkman & will test the effect of altering a person's coping style on his

Lazarus, 1980). Subjects used an average of 6.5 coping or her adjustment to their disease.

strategies per stressful situation (Folkman, Lazarus, The combination of actions that are believed to be

Gruen, & DeLongis, 1986). The amount of each category most appropriate to the situation form a coping plan.

of coping technique that subjects used varied with the This plan appears to be affected by both the emotional

appraisal of what was at stake and how changeable it was. reactions and the specific situation with which the person

Positive reappraisal of the situation was the most stable must cope. The Appraisal Model of Coping, therefore,

coping strategy, that is, it was the strategy that appeared views the plan as a product of the interaction of the

to be used regardless of the nature of the stressor. Pearlin primary and secondary appraisal processes, which is rep-

and Schooler (1978) found definite patterns to people's resented by the intersection of the two appraisal circles

choices of strategies in each of the four life roles. In (see Figure 1).

marriage and parenthood, self-reliance was more effec-

tive than the seeking of assistance. In vocational endeav-

Outcome Appraisal

ors, avoidant strategies were more predominant. Stress

was virtually eliminated when between five and six differ- Outcome appraisal is the process by which the person

ent strategies were used concurrently to cope with the coping with the stressor evaluates the effectiveness of the

same stressor. Except in the vocational category, in- initial coping plan. I added the outcome appraisal process

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 359

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930245/ on 09/16/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

to the Appraisal ModeJ of Coping in response to Ban- of Coping prOVides a basis for understanding other fac-

dura's (1986) theory that positS that behavior, personal tors that interfere with skill use. It also provides a concep-

factors, and environmental events are interacting deter- tual basis for the development and subsequent evaluation

minants of one another. This is referred to by Perry et al. of holistic programs that mitigate these factors. Although

(1990) as reciprocal determinism. The cognitive rela- skill development is an important focus of occupational

tional theory of coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1987) alludes therapy practice, we must concentrate not only on the

to, but does not address, the influence of the initial cop- development of the components of the skill, but also on

ing efforts on subsequent behavior. Bandura (1977) stat- removing barriers to the use of the skill once it has been

ed that a change in behavior, personal factors, or the attained.

environment will result in a change or changes in each of When an occupational therapist is treating a client

the other two factors. It follows that the implementation who is coping with a major life event, it is important for

of the initial coping plan may alter the primary or secon- him or her to understand the forces affecting the patient's

daly appraisal processes either directly or by altering one choice of coping plan. This is particularly true if the se-

of the influencing factors. lected coping strategy is negatively affecting the patient's

The concept of outcome appraisal in the Appraisal progress in occupational therapy or his or her ability to

Model of Coping generates the two performance feed- cope with daily life stressors. Coping that results in an

back [oops. As shown in Figure 1, there are two proposed inability to handle the stresses of daily life will henceforth

paths along which performance feedback travels. The be referred to as maladaptive coping.

first path directly links outcome appraisal to the primary The Appraisal Model of Coping can be used to identi-

and secondary appraisal circles. This indicates that the fy the rationale for selection of the coping plan. The client

perceived efficacy of the coping plan directly affects the could be evaluated to determine whether one of the three

perception of threat and the assessment of the coping appraisal processes or any of the influencing factors are

strategies available to deal with the altered level of per- responsible for the maladaptive coping behavior. The

ceived threat. The second path provides performance therapist could explore with the client whether he or she

feedback to all of the factors that influence the primary believes that he or she has a stake in the event (primary

and secondary appraisal processes. For example, if the appraisal) and all of the reasons for that belief. For exam-

coping plan is working well, the performance feedback ple, the therapist could question whether it is a cultural or

will increase the person's perceived level of self-efficacy existential belief that is creating the intense fear reaction.

because the person is now reassured that he or she is The therapist can then explore what the client sees as his

capable of effectively managing the stress. This in turn or her coping resources (secondary appraisal), including

affects the primary and secondary appraisal processes by how all the factors influencing the delineation of coping

decreasing the perceived threat and lessening the need to resources are influencing the decision process. Finally,

generate alternative coping strategies. This feedback loop the therapist can explore the person's experience to date

cannot, of course, alter all of the factors affecting the with the stressor and whether he or she perceives his or

appraisal process, in that the factors of age and sex are her coping plan to be effective (outcome appraisal).

biologically determined. This exploratory process should lead to a better un-

derstanding of the client's interpretation of the situation.

The therapist can then assist in the reappraisal process by

Final Outcome

targeting the affected areas. For example, if belief in the

The appraisal and reappraisal processes continue until efficacy of the prescribed treatment is a problem, then

the stressor has been effectively dealt with or the stressful the therapist can provide more credible sources of infor-

event is over. The cycle begins again whenever a stressful mation. The sources would have to be credible to the

event is anticipated or being dealt with. The same cycle client, not the therapist. If the major issue were incuba-

may be ongoing for several stressors concurrently. tion of threat, perhaps strategies for ensuring that the

event occurs sooner could be explored.

Intervention could involve facilitation of change to

Application to Occupational Therapy

anyone of the three appraisal processes or to any of the

Intervention

factors that influence the appraisal processes. Research

A review of occupational therapy literature confirms that would then revolve around identifying the best methods

there has been a long-standing interest in assessment and of assessment and alteration of the factors responsible for

treatment of patients who need to cope more effectively the patient's maladaptive coping.

(Burke, 1984; Courtney & Escobedo, 1990; Klein, 1988; There also will be a need to acknowledge and accept

Oakley, Kielhofner, & Barris, 1985; Skinner, 1987; Trom- unchangeable factors, such as dearly held beliefs and the

bly & Scott, 1977). This literature concentrates on the patient's age. The emphasis then would be on how to

development of coping skills with the expectation that work around the beliefs to facilitate adaptive coping strat-

once a skill is learned it will be used. The Appraisal Model egies. It is worthy of note that the term faCilitation is

360 April 1992, Volume 46, Number 4

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930245/ on 09/16/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

frequently used in this paper when referring to occupa- Acknowledgmen t

tional therapy intervention. This is due to the belief that I thank Elizabeth Yerxa for providing the impetus to develop

the client is ultimately responsible for the change. The and publish this coping model and for her comments regarding

therapist simply provides the additional information or the model itself.

experience needed to enhance the client's awareness of

what is possible and to support the change process.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory

Future Development of behavioral change, Psychological Review, 84, 191-215,

The Appraisal Model of Coping is a new synthesis of the Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human

agency. Amen'can Psychologist, 37, 122-147.

literature and as such requires further development with Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and

respect to its application to the assessment and treatment action' A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, N]: Pren-

of clients seen by occupational therapists. An extensive tice-Hall.

review of the literature on each of the influencing factors Blumenthal, J A. (1985), Relaxation therapy, biofeedback,

and behavioral medicine. Psychotherapy, 22, 516-530,

is recommended. The objective of this intensive review

Bombardier, C. H" D'Amico, c., & Jordan,J S (1990). The

would be to gain an understanding of each of the influ- relatiOnship of appraisal and coping to chronic illness adjust-

encing factors from a broad literature base and to identify ment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28, 297-304.

ways of intervening to change the effect they have on Borden, W" & Berlin, S, (1990), Gender, coping, and psy-

coping. For example, by researching the influencing fac- chological well-being in spouses of older adults with chronic

dementia American journal of Orthopsychiatry, 60, 603-610

tor of physiological arousal, one would find a wealth of

Breznitz, S, (1967), Incubation of threat: Duration of antici-

information about relaxation training and biofeedback pation and false alarm as determinants of the fear reaction to an

(Blumenthal, 1985). This information would assist with unavoidable frightening event. journal of Experimental Re-

the development of evaluation tools and effective inter- search in Personality, 2, 173-179.

vention processes. The influencing factors that can be Burke, J. P. (1984). Occupational therapy: A focus for roles

in practice. American journal of Occupational Therapy, 38,

changed (Le., physiological arousal, social support,

24-28,

empowerment, efficacy, information, and skills) should Courtney, c., & Escobedo, B. (1990). AStress management

be the subject of the most intensive review. To this end, program: Inpatient-to-outpatient continuity, Americanjournal

the concept of perceived self-efficacy is currently being of Occupational Therapy, 44, 306-310.

reviewed, and a measurement tool that will be used in Diaz-Guerrero, R. (1979). The development of coping style.

future occupational therapy outcome research is being Human Development, 22, 320-333.

Dunst, C. J (1988), Enabling and empowering families,

developed. Princzples and guidelines for practice, Cambridge, NIA:

Brookline,

Folkins, C. H. (1970), Temporal factors and the cognitive

Summary mediators of stress reaction. journal ofPersonality and Social

Psychology, 14, 173-184,

The Appraisal Model of Coping is a tool that shows a great Folkman, S, (1984). Personal control and stress and coping

deal of promise in the practice of occupational therapy. processes: A theoretical analysis. journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 46, 839-852

Its emphasis on person-environment interaction is a con-

Folkman, S" & Lazarus, R, (1980. September), An analysis

cept that is congruent with the values of the profession, of coping in a middJe-aged community sample. journal of

as stated by Yerxa (1983). Occupational therapists value Health and Social Behavior, 21, 219-239.

the uniqueness and strengths of the person and, there- Folkman, S" Lazarus, R" Pimley, S., & Novacek, j. (1987).

fore, the ability to look at coping as an individual appraisal Age differences in stress and coping processes, Psychology and

Aging, 2, 171-184

process has a goodness of fit to the occupational therapy

Folkman, S" Lazarus, R. S., Gruen, R. J, & DeLangis, A,

process. (1986), Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological

Bandura (1977) stated, "On the one hand, the mecha- symptoms. journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50,

nisms by which human behaviour is acquired and regu- 371-379

lated are increasingly formulated in terms of cognitive Gergen, K. J (1982) Toward transformation in social

knowledge, New York: Springer-Verlag,

processes. On the other hand, it is performance-based

Gore, S. (1978, June), The effect of social support in mod-

procedures that are proving to be most powerful for af- erating the health consequences of unemrloyment.journal of

fecting psychological changes" (p, 191). The occupational Health and Social Behauior, 19, 157-165.

therapy process, which emphasizes the use of activity as a Health and Welfare Canada. (1983), The gUidelines for the

method of treatment, is therefore likely to be very effec- client-centred practice of occupational therapy. Ottawa, ON:

Institutional and Professional Services, Division Health Services

tive in altering people's coping mechanisms. Guidance by

Directorate.

an occupational therapist to ensure that patients experi- Houtman, I. L D, (1990). Personal coping resources anel

ence success with new behavioral techniques will be in- sex differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 11,

strumental in enhancing coping success .• 53-63,

The American journal of Occupational Therapv 361

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930245/ on 09/16/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

Ingstad, B. (1988). Coping behavior of disabled persons Studies in empowerment: Steps toward understanding and

and their families: Cross-cultural perspectives from Norway and action (pp. 1-7). New York: Haworth.

Botswana. International journal of Rehabilitation Research, Reed, K., & Sanderson, S. R. (1980). Concepts ofoccupa-

11, 351-359 tional therapy. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Kennett, D., Bleasdale, F., Pitt, D., & Blom, C. (1990). Seek- Rogers, R. W. (1983) Cognitive and physiological pro-

ing and keeping work: The imparLance of self-efficacy and self- cesses in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of

regulatOry skills. National Consultation on Vocational Coun- protection motivation. In]. T Cacioppo, R. E. Petty, & D. Sha-

selling, 16, 88-98 piro (Eds.), Social psychophysiology (pp. 153-176). New York:

Klein, J. M. (1988). Abstinence-oriented inpatient treat- Guilford Press.

ment of the substance abuser. Occupational Therapy In Men- Rook, K. S., Catalano, R., & Dooley, D. (1989). The timing of

tal Health, 8(2), 47-59. major life events: Effects of departing from the social clock.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress appraisal and American journal of Community Psychology, 17, 233-257.

coping. New York: Springer. Rotter,]. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1987). Transactional theory verses external locus of control. Psychological Monographs

and research on emotions and coping. European journal of (Whole No. 609).

Personality, 1, 141-169. Salovey, P., & Birnbaum, D. (1989). Influence of mood on

Light, K. C. (1981). Cardiovascular responses to effortful health-relevant cognitions. journal of Personality and Social

active coping: Implications for the role of stress in hypertension Psychology, 57, 539-551.

development. Psychophysiology, 18, 216-225. Singh, A. K., & Pandey,]. (1990). The social support as a

Lord,]., & Farlow, D. M. (1990, Fall). A study of personal moderatOr of the relationship between poverty and coping be-

empowerment: Implications for health promotion. Health Pro- haviors. journal of Social Psychology, 130, 533-541.

motion, pp. 2-8. Skinner, S. T (1987). Multiple personality disorder: Occu-

MatOn, K. 1. (1989). The stress-buffering role of spiritual pational therapy intervention in acute care psychiatry. Occupa-

suppOrt: Cross-sectional and prospective investigations. jour- tional Therapy In Mental Health, 7, 93-108.

nalfor the SCientific Study of Religion, 28, 310-322. Smith, L. W., Patterson, T, & Grant, I. (1990). Avoidant

Mechanic, D. (1980). Mental health and social policy. En- coping predicts psychological disturbance in the elderly. jour-

glewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. nal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 178, 525-530.

Oakley, F., Kielhofner, G., & Barris, R. (1985). An occupa- Strong, c.]. C. (1989). A conceptual/ook at empowerment

tional therapy approach to assessing psychiatric patients' adap- (Project No. 206). (Available from the Vocational Rehabilitation

tive functioning. Amen·can journal of Occupational Therapy, Research Institute, Department of Research, 3304 33rd Street,

39, 147-154. NW, Calgary, AB)

Obrist, P. A. (1981). Cardiovascular psychophysiology. Suls,J., & Fletcher, B. (1985). The relative efficacy of avoid-

New York: Plenum Press. ant and nonavoidant coping strategies: A meta-analysis. Health

Park, c., Cohen, L. H., & Herb, L. (1990). Intrinsic religious- Psychology, ~ 249-288.

ness and religious coping as life stress moderatOrs for Catholics Thoits, P. A. (1986). Social suPPOrt as coping assistance.

versus Protestants. journal ofPersonality and Social Psycholo- journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 416-423.

gy, 59, 562-574 Trombly, C. A., & Scott, A. D. (1977). Occupational ther-

Pearlin, L. 1., & Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of cop- apy for physical dysfunction. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

ing. journal of Health and SOCial BehaVior, 19, 2-21. White, R. W. (1974). Strategies of adaptation: An attempt at

Perry, C. L., Baranowski, T, & Parcel, G. S. (1990). How systematic description. In S. V. Coelho, D. A. Hamburg, & J. E.

indiViduals, enVironments, and health behavior interact: Social Adams (Eds.), Coping and adaptation (pp. 47--{)8). New York:

learning theory. In K. Slanz, F. M. Lewis, & B. K. Rimer (Eds.), Basic.

Health behavior and health education. San Francisco: Jossey- Yerxa, E. (1983). Audacious values: The energy source

Bass. for occupational therapy practice. In G. Kielhofner (Ed.),

Rappaport,]. (1984). Studies in empowerment: Introduc- Health through occupation (pp. 149-162). Philadelphia: F. A.

tion to the issue. In]. Rappaport, C. SWift, & R. Hess (Eds.), Davis.

362 April 1992, Volume 46, Number 4

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930245/ on 09/16/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

Вам также может понравиться

- Reeducative TherapyДокумент2 страницыReeducative TherapyYoshita AgarwalОценок пока нет

- Bringing The Psychotherapist Back: Basic Concepts For Reading Articles Examining Therapist Effects Using Multilevel ModelingДокумент11 страницBringing The Psychotherapist Back: Basic Concepts For Reading Articles Examining Therapist Effects Using Multilevel ModelingJulio César Cristancho GarcíaОценок пока нет

- Tsai 2013 AclДокумент5 страницTsai 2013 Aclran almogОценок пока нет

- Integration of Medication Management Into Occupational Therapy PracticeДокумент7 страницIntegration of Medication Management Into Occupational Therapy PracticeManuel PérezОценок пока нет

- The Role of Occupational Therapy in Pain Management: DipcotДокумент3 страницыThe Role of Occupational Therapy in Pain Management: DipcotNicole Fernanda Soto HernándezОценок пока нет

- A Critical Analysis of Occupational Therapy Approaches For Perceptual Deficits in Adults With Brain InjuryДокумент6 страницA Critical Analysis of Occupational Therapy Approaches For Perceptual Deficits in Adults With Brain InjurysaranottenОценок пока нет

- Mindfulness Training and Problem Formulation: Key WordsДокумент4 страницыMindfulness Training and Problem Formulation: Key WordsÁngel LópezОценок пока нет

- Occupation-Centered Assessment of Children: Wendy CosterДокумент8 страницOccupation-Centered Assessment of Children: Wendy CosterAna Claudia GomesОценок пока нет

- Resolving Therapeutic Alliance Ruptures: Diversity and IntegrationДокумент11 страницResolving Therapeutic Alliance Ruptures: Diversity and IntegrationPablo GuerraОценок пока нет

- 569 PDFДокумент7 страниц569 PDFferas ahmedОценок пока нет

- Adaptación Ocupacional. InglesДокумент9 страницAdaptación Ocupacional. InglesTerapia OcupacionalОценок пока нет

- Uniform Terminology AOTA PDFДокумент8 страницUniform Terminology AOTA PDFLaura GuevaraОценок пока нет

- A Logical Framework For Functional Analytic Group TherapyДокумент9 страницA Logical Framework For Functional Analytic Group TherapyMaría Emilia Schultz100% (1)

- Chambless 1998Документ12 страницChambless 1998Stefania CioncaОценок пока нет

- Training in Experiential Therapy. (1988)Документ7 страницTraining in Experiential Therapy. (1988)Virendrasinh ChauhanОценок пока нет

- Mckenna 2013Документ4 страницыMckenna 2013zettaknОценок пока нет

- Book - OT Manager - Chap 34 Supervising Other DisciplinesДокумент9 страницBook - OT Manager - Chap 34 Supervising Other DisciplinesWhitney JosephОценок пока нет

- Nihms 564241Документ33 страницыNihms 564241Natalia BettancourtОценок пока нет

- Callaghan (2006) - The FIAT SystemДокумент42 страницыCallaghan (2006) - The FIAT SystemdanielassazОценок пока нет

- Application of Motor Learning Principles in Occupational TherapyДокумент7 страницApplication of Motor Learning Principles in Occupational TherapyMarina EОценок пока нет

- What Is Professionalism in Occupational Therapy? A Concept AnalysisДокумент14 страницWhat Is Professionalism in Occupational Therapy? A Concept AnalysisNataliaОценок пока нет

- Submitted By: Nikka CitationДокумент6 страницSubmitted By: Nikka CitationNikka Marie DalaganОценок пока нет

- The Heart and Soul of Change Getting BetДокумент2 страницыThe Heart and Soul of Change Getting BetLola Al Smith100% (1)

- Uniform Terminology For Occupationall THДокумент8 страницUniform Terminology For Occupationall THcjОценок пока нет

- Population Centered Life Skills Groups Perceptions of Satisfaction and EngagementДокумент7 страницPopulation Centered Life Skills Groups Perceptions of Satisfaction and EngagementPaula FariaОценок пока нет

- TFN Finals ReviewerДокумент3 страницыTFN Finals Reviewerediyette parduaОценок пока нет

- M Allows 2017Документ3 страницыM Allows 2017Francisco Javier Luza RamosОценок пока нет

- OT Theories (In A Nutshell)Документ8 страницOT Theories (In A Nutshell)TaraJane House100% (1)

- Fitzgerald 1991 Self Efficacy Theory Implications For The Occupational Health NurseДокумент6 страницFitzgerald 1991 Self Efficacy Theory Implications For The Occupational Health NursefatimatijjaneeОценок пока нет

- Teyber2014 - Working With The Process DimensionДокумент8 страницTeyber2014 - Working With The Process DimensionSpongeBobLongPantsОценок пока нет

- Jurnal AnggiaДокумент4 страницыJurnal AnggiaDwi Happy AnggiaОценок пока нет

- The Heart and Soul of Change: Getting Better at What We Do: June 2013Документ3 страницыThe Heart and Soul of Change: Getting Better at What We Do: June 2013CAMILA ALINE MUNOZ MARCOTTIОценок пока нет

- Differences Among Trainees in Client Outcomes Associated With The Phase Model of ChangeДокумент8 страницDifferences Among Trainees in Client Outcomes Associated With The Phase Model of ChangeJulio César Cristancho GarcíaОценок пока нет

- Interventions in Occupational Health PsychologyДокумент3 страницыInterventions in Occupational Health PsychologyCristian Steven Cabezas JoyaОценок пока нет

- Group1 - Models TheoriesДокумент5 страницGroup1 - Models TheoriesDEVORAH CARUZОценок пока нет

- Quallsa Client RT Treatment Plan 2019Документ4 страницыQuallsa Client RT Treatment Plan 2019api-437360672Оценок пока нет

- PrinciplesofSkillsAssessmentinDBT SwalesDunkleyДокумент13 страницPrinciplesofSkillsAssessmentinDBT SwalesDunkleyPaula TrindadeОценок пока нет

- Acis 3Документ9 страницAcis 3Maryam AlkanderyОценок пока нет

- Clinical Effectivieness of Occupational Therapy in Mental Health A Meta-AnalysisДокумент9 страницClinical Effectivieness of Occupational Therapy in Mental Health A Meta-AnalysisGloria Nataly Ramirez Badillo100% (1)

- Lifeskills Aftercare PosterДокумент1 страницаLifeskills Aftercare Posterapi-485106673Оценок пока нет

- Nursing FoundationДокумент11 страницNursing FoundationPriya Sharma100% (3)

- Reflective Account of Nursing1Документ33 страницыReflective Account of Nursing1Min Yem91% (11)

- Therapist Self-Disclosure As An Integrative InterventionДокумент17 страницTherapist Self-Disclosure As An Integrative InterventionVu ThuОценок пока нет

- Based Assessment Top Down and Bottom UpДокумент7 страницBased Assessment Top Down and Bottom UpjesscavalcanteОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Evaluation and InterviewingДокумент19 страницIntroduction To Evaluation and InterviewingMaria AiramОценок пока нет

- Park 2021 Comprehensive Resiliency Framework Theoretical Model TreatmentДокумент10 страницPark 2021 Comprehensive Resiliency Framework Theoretical Model TreatmentMichel MaragelОценок пока нет

- Identifying and Selecting Target Problems For Clinical InterventionsДокумент10 страницIdentifying and Selecting Target Problems For Clinical InterventionsPsic. Laura MuñozОценок пока нет

- Running Head: Improving Performance Using 1Документ10 страницRunning Head: Improving Performance Using 1Sean LoranОценок пока нет

- Clinical Case Formulation Slide (p123718)Документ36 страницClinical Case Formulation Slide (p123718)TRACY SOIDIОценок пока нет

- Met A CognitionДокумент10 страницMet A CognitionPaulina Medina RodriguezОценок пока нет

- Flanagan (2014) Unmet Needs Maladaptive ModesДокумент15 страницFlanagan (2014) Unmet Needs Maladaptive ModesCristina ColoteloОценок пока нет

- Research Article AotaДокумент9 страницResearch Article AotasarahОценок пока нет

- Impact of Therapist Emotional Intelligence On PsychotherapyДокумент11 страницImpact of Therapist Emotional Intelligence On PsychotherapyPrachi DokaniaОценок пока нет

- Professional Strategies in Work-Related Practice: An Exploration of Occupational and Physical Therapy Roles and ApproachesДокумент9 страницProfessional Strategies in Work-Related Practice: An Exploration of Occupational and Physical Therapy Roles and Approachesasr27Оценок пока нет

- Mindful Crafts As Therapy Engaging More Than Hands Print Replica Ebook PDFДокумент62 страницыMindful Crafts As Therapy Engaging More Than Hands Print Replica Ebook PDFkerri.roland216100% (41)

- Functional Analytic Psychotherapy - A Behavioral Relational Approach To TreatmentДокумент9 страницFunctional Analytic Psychotherapy - A Behavioral Relational Approach To TreatmentJuan EstebanОценок пока нет

- Interventions To Enhance Adaptation To Bereavement: Henk Schut, Ph.D. and Margaret S. Stroebe, PH.DДокумент8 страницInterventions To Enhance Adaptation To Bereavement: Henk Schut, Ph.D. and Margaret S. Stroebe, PH.DGeorgea AlexandraОценок пока нет

- Introducción - THERAPEUTIC EXERCISE - Cap 2 - 1-10Документ10 страницIntroducción - THERAPEUTIC EXERCISE - Cap 2 - 1-10Yazmin LopezОценок пока нет

- CBT+ DBT+ACT & Beyond: A Comprehensive Collection on Modern Therapies Including PTSD Healing, Vagus Nerve Insights, Polyvagal Dynamics, EMDR Techniques, and Somatic ApproachesОт EverandCBT+ DBT+ACT & Beyond: A Comprehensive Collection on Modern Therapies Including PTSD Healing, Vagus Nerve Insights, Polyvagal Dynamics, EMDR Techniques, and Somatic ApproachesОценок пока нет

- ArtemisДокумент3 страницыArtemisAxeliaОценок пока нет

- Declamation PiecesДокумент4 страницыDeclamation PiecesAxeliaОценок пока нет

- AppeconДокумент1 страницаAppeconAxeliaОценок пока нет

- AaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaДокумент3 страницыAaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaAxeliaОценок пока нет

- Abm TermsДокумент2 страницыAbm TermsAxeliaОценок пока нет

- AcrosticДокумент1 страницаAcrosticAxeliaОценок пока нет

- "Thou Shall Not: Human RightsДокумент4 страницы"Thou Shall Not: Human RightsAxeliaОценок пока нет

- Filmora CrackДокумент2 страницыFilmora CrackAxelia100% (1)

- Acrostic HistoryДокумент1 страницаAcrostic HistoryAxeliaОценок пока нет

- 10 HOT AND Cold Sanwiches Recipes: Compiled By: Giesel Anne Yebes 9-ManggaДокумент13 страниц10 HOT AND Cold Sanwiches Recipes: Compiled By: Giesel Anne Yebes 9-ManggaAxeliaОценок пока нет

- Among The Problems That Arises in The Trece Martires City Hall - City TourismДокумент18 страницAmong The Problems That Arises in The Trece Martires City Hall - City TourismAxeliaОценок пока нет

- Pattern 1Документ20 страницPattern 1AxeliaОценок пока нет

- Republic of The Philippines Region Iv-A Calabarzon Department of Education Division of Cavite Trece Martires City Senior High SchoolДокумент18 страницRepublic of The Philippines Region Iv-A Calabarzon Department of Education Division of Cavite Trece Martires City Senior High SchoolAxeliaОценок пока нет

- John David Panaligan VillaceranДокумент1 страницаJohn David Panaligan VillaceranAxeliaОценок пока нет

- Title of The Attached PDFДокумент13 страницTitle of The Attached PDFAxeliaОценок пока нет

- © 2005 Viacom International Inc. All Rights ReservedДокумент20 страниц© 2005 Viacom International Inc. All Rights ReservedAxeliaОценок пока нет

- Project Proposal OutlineДокумент4 страницыProject Proposal OutlineMyunimintОценок пока нет

- Brain Health Dramatically Improved by Intake of OmegaДокумент18 страницBrain Health Dramatically Improved by Intake of OmegaAbdul Rasheed100% (1)

- Predicting Physiological Capacity of Human Load Carriage - A ReviewДокумент10 страницPredicting Physiological Capacity of Human Load Carriage - A ReviewlnarimotoОценок пока нет

- HEPATOLITIASISДокумент49 страницHEPATOLITIASISFitriardi SejatiОценок пока нет

- 1 - Common Disorders of The Ear Nose and ThroatДокумент7 страниц1 - Common Disorders of The Ear Nose and ThroatDina DestrianaОценок пока нет

- Russian Current Shiva Sarari 1Документ25 страницRussian Current Shiva Sarari 1Sharma MukeshОценок пока нет

- Grade 9 Health Quarter 3Документ18 страницGrade 9 Health Quarter 3spine clubОценок пока нет

- Risk Assessment Template - HouseДокумент3 страницыRisk Assessment Template - HouseSean SpencerОценок пока нет

- 5 Elements of Abdominal DiagnosisДокумент14 страниц5 Elements of Abdominal Diagnosiscelliastt100% (4)

- Case Scenario/Situation Answer/Explanation: NCM 101 RLE - Health AssessmentДокумент2 страницыCase Scenario/Situation Answer/Explanation: NCM 101 RLE - Health AssessmentmaryОценок пока нет

- Role of NurseДокумент24 страницыRole of NurseJohnykutty JosephОценок пока нет

- NCP Hyperbilirubinemia Staff NursingДокумент3 страницыNCP Hyperbilirubinemia Staff NursingVerajoy DaanОценок пока нет

- Duties of A Labor and Delivery NurseДокумент3 страницыDuties of A Labor and Delivery Nursefenan sollanoОценок пока нет

- Legal MedДокумент16 страницLegal MedRYAN FONTANILLA100% (1)

- Adult Obesity ResearchДокумент19 страницAdult Obesity Researchchoraz100% (1)

- M ChatДокумент2 страницыM Chatballad3100% (2)

- Unit-Ii Role of The Nurse in Health Care: By: Farzana Nursing InstructorДокумент26 страницUnit-Ii Role of The Nurse in Health Care: By: Farzana Nursing InstructorFara ZamanОценок пока нет

- Kirtika Chopra ResumeДокумент1 страницаKirtika Chopra ResumekirtikaОценок пока нет

- John Keith Krebs 1 SubstanceAbuse UnjustifiedPrescriptions PDFДокумент30 страницJohn Keith Krebs 1 SubstanceAbuse UnjustifiedPrescriptions PDFWKYC.comОценок пока нет

- Birth Injuries in NeonatesДокумент14 страницBirth Injuries in NeonatessolecitodelmarОценок пока нет

- Focusing On Children Mental HealthДокумент2 страницыFocusing On Children Mental HealthDzatil HusniОценок пока нет

- Коспект лекційДокумент51 страницаКоспект лекційМарія МайорчакОценок пока нет

- Fathers' Experiences in Caring For A Young Child With Autism Spectrum DisorderДокумент33 страницыFathers' Experiences in Caring For A Young Child With Autism Spectrum DisorderlauraОценок пока нет

- SITHRM001 Coach Others in Job SkillsДокумент18 страницSITHRM001 Coach Others in Job SkillsAnmol PoudelОценок пока нет

- Bajaj Committee Report 1996Документ267 страницBajaj Committee Report 1996lalit823187Оценок пока нет

- Danica Hannah Mae L. Tumacder Bsed 2B MWF 4-5PM Assignment: Ge Sts APRIL 12, 2021Документ4 страницыDanica Hannah Mae L. Tumacder Bsed 2B MWF 4-5PM Assignment: Ge Sts APRIL 12, 2021Nica HannahОценок пока нет

- Diagnosis and Management of Deep Vein Thrombosis in PregnancyДокумент10 страницDiagnosis and Management of Deep Vein Thrombosis in PregnancyAita AladianseОценок пока нет

- HANDOUT 5 - HEALTH PROMOTION, HEALTH MAINTENANCE and HEALTH CONSIDERATIONSДокумент2 страницыHANDOUT 5 - HEALTH PROMOTION, HEALTH MAINTENANCE and HEALTH CONSIDERATIONSkaycelyn jimenez100% (1)

- Unit 2 - UHVДокумент65 страницUnit 2 - UHVSrihari PuttaОценок пока нет

- Eitan Armon Resume 090619Документ2 страницыEitan Armon Resume 090619JUWON AJIBOYEОценок пока нет