Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Estudio Piloto

Загружено:

Nina SalinasОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Estudio Piloto

Загружено:

Nina SalinasАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Lessons Learned: A Pilot Study on Occupational Therapy

Effectiveness for Children With Sensory Modulation Disorder

Lucy Jane Miller, Sarah A. Schoen, Katherine James, Roseann C. Schaaf

KEY WORDS OBJECTIVE. The purpose of this pilot study was to prepare for a randomized controlled study of the effec-

• effectiveness tiveness of occupational therapy using a sensory integration approach (OT-SI) with children who have sensory

• occupational therapy processing disorders (SPD).

• pediatric METHOD. A one-group pretest, posttest design with 30 children was completed with a subset of children

with SPD, those with sensory modulation disorder.

• sensory integration

• sensory modulation disorder (SMD) RESULTS. Lessons learned relate to (a) identifying a homogeneous sample with quantifiable inclusion cri-

teria, (b) developing an intervention manual for study replication and a fidelity to treatment measure, (c) deter-

• sensory processing

mining which outcomes are sensitive to change and relate to parents’ priorities, and (d) clarifying rigorous

methodologies (e.g., blinded examiners, randomization, power).

CONCLUSION. A comprehensive program of research is needed, including multiple pilot studies to develop

enough knowledge that high-quality effectiveness research in occupational therapy can be completed. Previ-

ous effectiveness studies in OT-SI have been single projects not based on a unified long-term program of

research.

Miller, L. J., Schoen, S. A., James, K., & Schaaf, R. C. (2007). Lessons learned: A pilot study on occupational therapy effec-

tiveness for children with sensory modulation disorder. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61, 161–169.

Lucy Jane Miller, PhD, OTR, FAOTA, is Associate n ongoing controversy exists regarding the effectiveness of occupational ther-

Clinical Professor, Departments of Rehabilitation Medicine

and Pediatrics, University of Colorado at Denver and

A apy using a sensory integration approach (OT-SI). In the past 35 years, more

than 80 studies have addressed the effectiveness of OT-SI, about half of which

Health Sciences Center; Director, Sensory Therapies and

Research (STAR) Center; and Director, KID Foundation, demonstrated positive effects from OT-SI. Reviews of the effectiveness of OT-SI

5655 South Yosemite Street, Suite 305, Greenwood include two meta-analyses and four research syntheses (Arendt, MacLean, &

Village, CO 80111; miller@KIDfoundation.org.

Baumeister, 1988; Hoehn & Baumeister, 1994; Polatajko, Kaplan, & Wilson,

Sarah A. Schoen, PhD, OTR, is Clinical Instructor,

1992; Schaffer, 1984). One meta-analysis concluded that the treatment had no

University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences positive effect (Vargas & Camilli, 1999); however, this study had significant

Center; Director of Occupational Therapy, STAR Center; methodological flaws. The other meta-analysis concluded that the intervention

and Senior Researcher, KID Foundation, Greenwood

had positive effects; however, only studies conducted before 1980 were included

Village, CO.

(Ottenbacher, 1982). The four review articles were critical of OT-SI but noted that

Katherine James, MSPH, MSCE, is Doctoral Candi- previous studies were not rigorous enough to make valid conclusions. Thus, no

date, Health Sciences Center, Department of Epidemiology, consensus exists within the professional community regarding the value of OT-SI.

University of Colorado at Denver.

The implementation of rigorous effectiveness studies is complex, requiring

Roseann C. Schaaf, PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA, is Associ- pilot studies to resolve problematic issues before initiating the intended study

ate Professor, Vice Chair, and Director of Graduate Studies, (Boruch, 1997). Pilot studies can test the feasibility of methods, define selection

Department of Occupational Therapy, Thomas Jefferson criteria, choose appropriate outcomes, and clarify programmatic issues, thereby

University, Philadelphia.

identifying limitations that could have an impact on the final study (Portney &

Watkins, 2000).

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 161

All previous studies regarding OT-SI effectiveness changes after occupational therapy and that group differ-

asked a naïve question, “Is OT-SI effective?” A single study ences were not significant. Because the treatments are not

cannot answer that multifaceted question. No study easily distinguished, the importance of this finding is diffi-

described a series of prior pilot studies or met all of the cri- cult to understand.

teria for a reliable and valid outcome study. Thus, the only Additionally, previous studies did not have a fidelity to

conclusion that can be drawn after 35 years of single, non- treatment process. Fidelity measures provide crucial evi-

programmatic research projects is that the evidence neither dence evaluating adherence to treatment principles

disproves nor confirms that OT-SI is effective. (Kazdin, 1994).

The “gold standard” effectiveness study is a random- Sensitive and meaningful outcomes. In general, the exist-

ized controlled trial (RCT) in which the targeted treatment ing studies evaluated outcomes that were neither sensitive

is compared to another treatment or treatments, for exam- to small increments of change nor meaningful based on

ple, an active placebo or a passive placebo (Boruch, 1997). parents’ priorities for treatment outcomes (Cohn, Miller, &

A rigorous RCT requires the following: Tickle-Degnen, 2000). The three outcomes of greatest

1. A homogeneous sample identified with replicable importance to parents of children with SPD are social par-

criteria ticipation, self-regulation, and perceived competence/self-

2. A “manualized” intervention approach (based on a esteem and self-confidence (Cohn, 1999).

manual detailing the intervention) and a fidelity to treat- No information on the sensitivity of the outcome mea-

ment measure that evaluates whether the intervention is sures was published before previous studies’ findings.

completed as intended Power, therefore, was not evaluated before the study was

3. Outcome measures that are sensitive enough to implemented. Because adequate power was rarely achieved,

detect changes during the treatment duration and mean- Type II errors abounded in studies that concluded that OT-

ingful enough to measure the changes that the treatment SI was ineffective; for example, in most cases not enough

purports to effect power was present to demonstrate significance of group dif-

4. Rigorous research design and methodology (e.g., ferences, although group differences were found.

blinded examiners, random assignment) Rigorous methodology. Rigorous methodology for

The following discussion details each of the four crite- RCTs includes (a) random assignment to two or more treat-

ria so that future occupational therapy studies can adhere to ment groups: experimental (i.e., occupational therapy),

these principles. active treatment placebo (e.g., tutoring, special education,

Homogeneous sample. A homogeneous sample must be or play time), or passive placebo (i.e., no treatment, such as

narrowly defined using replicable (quantitative) measures. a wait-list condition); (b) evaluators blinded to group

Previous OT-SI studies included heterogeneous (broad) assignments; (c) appropriate research designs; and (d) ade-

samples such as combinations of children and adults with quate power. No previous studies used this methodology.

mental retardation (Close, Carpenter, & Cibiri, 1986),

learning disabilities (Carte, Morrison, Sublett, Uemura, &

Setrakian, 1984; Werry, Scaletti, & Mills, 1990), and apha- Preparation for the Described Study

sia (DePauw, 1978) and individuals with “at-risk” diagnoses From 1995 to 2005, a series of pilot studies was conducted

(White, 1979). New nosologies suggest multiple subtypes before implementing an RCT of OT-SI (Ahn, Miller, Mil-

of SPD criteria that were unavailable for previous studies berger, & McIntosh, 2004; Cohn et al., 2000; Mangeot et

(Interdisciplinary Council, 2005; Miller et al., 2005; Zero al., 2001; McIntosh, Miller, Shyu, & Dunn, 1999; McIn-

to Three, 2005). Study inclusion criteria should specify the tosh, Miller, Shyu, & Hagerman, 1999; Miller et al., 1999;

subtype of SPD, as well as other factors (e.g., cognitive Miller, Reisman, McIntosh, & Simon, 2001; Miller, Robin-

level, age, comorbid diagnoses). son, & Moulton, 2004; Miller & Summers, 2001; Miller,

Replicable treatment. None of the studies has published Wilbarger, Stackhouse, & Trunnell, 2002; Schaaf & Miller,

manuals that can be reviewed detailing the elements of the 2005), including a wide variety of studies related to the four

treatment. One study purports to have used a manual criteria for rigorous research studies noted previously.

(Polatajko, Law, Miller, Schaffer, & Macnab, 1991), but

the manual is not available for review, so study replication

is not possible. The Polatajko et al. study clearly demon- Research Questions

strated the import of a manualized approach. A compari- This article describes a single group pretest–posttest pilot

son of sensory integration treatment to perceptual–motor outcome study designed to inform a future RCT, specifi-

treatment found that both groups demonstrated significant cally the following questions:

162 March/April 2007, Volume 61, Number 2

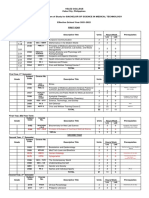

• What replicable criteria can identify a homogeneous Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Sample

group of children with SPD? for Single Group Pilot Study

Characteristics N (%)

• How can the essential components of treatment be

Gender

manualized and a fidelity to treatment measure developed? Girls 6 (20)

• What outcome measures are sensitive to changes over Boys 24 (80)

Race/ethnicity

a 20-session time period (10 weeks, twice a week)?

Caucasian 26 (86.80)

• What procedures can assure rigor in research design African American 1 (3.30)

and methodology? Hispanic 1 (3.30)

Asian 1 (3.30)

Other 1 (3.30)

Parents’ education (socioeconomic status)

Method < High school

High school

1 (3)

5 (17)

College 22 (73)

Participants: Research Question 1 Postcollege 2 (7)

The participants were children who met global criteria for

one subtype of SPD, sensory modulation disorder (SMD),

based on the impression of an occupational therapy master defined by Ayres (1972), emphasized use of a clinical rea-

clinician at The Denver Children’s Hospital after completion soning process (Mattingly, 1991), and focused on attaining

of a comprehensive occupational therapy evaluation lasting occupational goals. Therapists met bimonthly to review

from 2 to 4 hours The evaluation included a standardized treatment videotapes and engage in a reflective process of

scale, such as the Sensory Integration and Praxis Test (Ayres, understanding why the therapist made the clinical decisions

1989) for children ages 5.5–8.11 years or the Miller Assess- observed during treatment. The team elucidated the ele-

ment for Preschoolers (Miller, 1988) and FirstSTEP (Miller, ments of the therapeutic process and drafted a pilot man-

1993) for children ages 3.6–5.5 years, and clinical observa- ual, naming the process STEP–SI (Miller et al., 2002). This

tions (Blanche, 2002). Because no standardized tests for approach involved asking a series of questions to refine each

SMD exist, selection was based on evaluators’ global clinical child’s intervention.1 Based on the elements of intervention

impression. Inclusion criteria also included developmental specified in the treatment manual, a draft fidelity measure

and medical history suggesting SPD and behaviors consis- was constructed and has recently been substantially elabo-

tent with the disorder (Ayres, 1989). rated (Parham et al., 2007).

Exclusion criteria were IQ < 85 and any other develop-

mental, psychiatric, neurological, or orthopedic condition Instrumentation: Research Question 3

except attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), The study tested numerous measures to determine which

learning disorder, and mild Tourette’s syndrome. Children were most suitable for future studies. The domains and spe-

could have other SPD subtypes if SMD was present. Thirty cific outcome measures are the following:

children, ages 3.9–11 years (mean age 6.79, SD = 1.75), • Sensory Functioning. In iterative studies, content,

met inclusion or exclusion criteria for SMD based on the item, and factor analyses of the Sensory Profile (Dunn,

global impression of occupational therapists. 1999) were conducted to create the Short Sensory Profile

Quantification of inclusion criteria included develop- (McIntosh, Miller, Shyu, & Dunn, 1999). The 38 items on

ment of a parent report measure of SMD behaviors, the the Short Sensory Profile target only sensory behaviors,

Short Sensory Profile (McIntosh, Miller, Shyu, & Dunn, with a stable factor structure corresponding to sensory con-

1999), and abnormal physiologic reactivity on electroder- structs hypothesized in SMD.

mal reactivity (Miller et al., 1999) (see Instrumentation). • Attention, Impulsivity, and Activity Level. Several tools

Table 1 displays demographic characteristics of the study were used to evaluate attention, including (a) the ADD–H

participants. Comprehensive Teacher’s Rating Scale (ACTeRS) (Ull-

mann, Sleator, & Sprague, 1991), which is effective in dis-

The Experimental Treatment—OT-SI: criminating between children with and without attention

Research Question 2 disorders (Ullmann & Sleator, 1985, 1986; Ullmann,

The intervention, OT-SI (Ayres, 1972; Koomar & Bundy, Sleator, & Sprague, 1984); (b) three subtests of the Leiter

2002; Parham & Mailloux, 2001), was administered twice International Performance Scale–Revised: Parent Rating

a week for 10 weeks. Occasionally, a therapist or child Scale (Roid & Miller, 1997), which has an excellent

missed a session due to illness, but sessions were made up national standardization and impressive reliability and

within 2 weeks. The intervention was based on principles validity characteristics; (c) Barkley’s Behavior Rating for

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 163

AD/HD, widely cited in ADHD research (Barkley & Mur- Lofland (1995). Behavior codes were verbal interactions,

phy, 1998); and (d) the SNAP–IV used in the National nonverbal socialization, self-initiation, challenges encoun-

Institutes of Health (NIH) Multi-Site Trial (MTA Cooper- tered, success in resolution, and type of sensory input. Five-

ative Group, 1999). min segments were randomly selected from five 30-min

• Anxiety. Children with SMD are described as being tapes, which two investigators coded independently. The

overly anxious (Kinnealey, 1998; Kinnealey & Fuiek, 1999; total number of behaviors in each category was summed

Pfeiffer & Kinnealey, 2003). The Multi-Dimensional Anx- before and after intervention (interrater reliability = .90)

iety Scale for Children (MASC; March, 1997) was selected (Schaaf et al., 2001).

because it differentiates pathological anxiety from fears that • Individualized Measure of Parent-Perceived Priorities

are a natural part of development (March, 1995; Silverman, for Change. A contextually relevant measure of change, goal

LaGreca, & Wasserstein, 1995) and distinguishes children attainment scaling (GAS; Kiresuk, Smith, & Cardillo,

older than age 8 years with and without anxiety disorders 1994), was explored as an outcome. GAS examines indi-

(March, 1997). vidual priorities for change that are not represented by

• Activities of Daily Living. The most widely used adap- items in standardized scales because they are idiosyncratic to

tive scale, the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale (Stinnett, the child. GAS is gaining recognition as a valid outcome of

Havey, & Oehler-Stinnett, 1994; Wodrich & Barry, 1991), individualized change over time (Kiresuk et al., 1994).

was tested. The Vineland scale has been validated for accu- Researchers are discussing the advantages of evaluating out-

rate discrimination of deficits in performance of daily living comes that are patient-centered and specific for each partic-

skills (Altman & Mills, 1990; Douhitt, 1992; Rosenbaum, ipant in a study (Abikoff, 2001; Rockwood et al., 2000).

Saigal, Szatmari, & Hoult, 1995; Voelker, Shore, & Brown- Although the goals are different for each participant, the

More, 1990). score is standardized by writing goals that have responses

• Social and Emotional Behaviors. The Child Behavior that are theoretically spaced the same distance apart (e.g.,

Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) measures social and the same level of difficulty to achieve) (Forbes, 1998). Thus,

emotional behaviors based on parent and teacher reports a mathematical method can be derived of calculating the

and was piloted because numerous critiques have substanti- extent to which the goals are met (Kiresuk & Sherman,

ated its use in research (Elliott & Busse, 1992; Mooney, 1968). Table 2 displays an example of a GAS goal.

1984). The construct, content, and criterion validity of the Recent studies have demonstrated the use of GAS in

CBCL for discriminating social and behavioral issues is well outcome studies for people with a wide variety of disabili-

established (Chen, Faraone, Biederman, & Tsuang, 1994; ties: lower-extremity amputations (Rushton & Miller,

Jensen, Wantanabe, Richters, & Roper, 1996; Macmann, 2002), traumatic brain injury (Joyce, Rockwood, & Mate-

Barnett, Burd, & Jones, 1992). Kole, 1994; Malec, 2001), cognitive rehabilitation (Rock-

• Physiologic Measures. Extensive evaluation of physio- wood, Joyce, & Stolee, 1997), motor delays in infants (Pal-

logic measures of sensory reactivity was completed before isano, 1993), and geriatrics (Stolee, Rockwood, Fox, &

this study (Mangeot et al., 2001; McIntosh, Miller, Shyu, Streiner, 1992). In some studies, GAS has been found to be

& Hagerman, 1999; Miller et al., 1999, 2001) to ascertain more responsive to intervention than norm-referenced stan-

quantitative physiological markers assisting to define a dardized measures (Rushton & Miller, 2002). Interrater

homogeneous sample. The physiologic outcome measure reliability has been found to be moderate to excellent (.67,

used was electrodermal reactivity (EDR). EDR measures Joyce et al., 1994; .67, Rushton & Miller, 2002). Current

changes in the electrical conductance of the skin and is a

marker of activity in the sympathetic nervous system. The

children enter a pretend “spaceship” and watch the movie Table 2. Sample Goal Attainment Scale Items

Apollo 13 while electrodes are attached to their hands. Data Rank Level Description

are continuously collected during the Sensory Challenge –2 Child does not interact with peers.

–1 Child always plays alone during recess. Does not interact with

Protocol (Miller et al., 1999), a 15–20 min protocol in peers during recess.

which 50 sensory stimuli are administered (10 stimuli in 0 Child interacts with 1 peer with structure and/or cues and

each of five sensory systems). assistance.

+1 Child interacts with 1–2 peers independently on a consistent basis.

• Changes in Natural Settings. The children were video- +2 Child interacts with a small group of peers independently.

taped for approximately 30 min before and after interven- Note. Using Ottenbacher and Cusick’s (1993) method first, the expected per-

tion in playtime and dinnertime. Transcripts were made of formance (0) is defined. Other possible outcomes then are established: less

than expected level (–1), much less than expected level (–2), greater than

the videotaped activities, and a coding scheme was devel- expected level (+1), and much greater than expected level (+2). Parents rank

oped following the procedures outlined in Lofland and goals by priority and degree of difficulty.

164 March/April 2007, Volume 61, Number 2

studies will further refine this tool for the study of the effec- statistics were used and the findings are summarized in

tiveness of OT-SI (Mailloux et al., 2006). Table 3 for each measure that was significant or showed a

trend in the hypothesized direction.

Procedures: Research Question 4 The mean change over the 20-session period with sig-

After informed consent was obtained from parents, the par- nificance values and effect sizes are noted in Table 3. Mea-

ent report scales and Vineland interview were completed in sures that were nonsignificant or did not show changes in

a private, 1-hr, semistructured interview. A trained occupa- the hypothesized direction included Barkley’s Behavior Rat-

tional therapist viewed a videotape of the parent interview ing Scale (Barkley & Murphy, 1998), the SNAP–IV (MTA

to complete the writing of the GAS. Cooperative Group, 1999), the MASC (March, 1997), three

subtests of the Vineland (Stinnett et al., 1994), subtests of

the CBCL (Achenbach, 1991), subtests of the Leiter–R

Results (Roid & Miller, 1997) except Attention, some EDR vari-

Because this was a pilot study, the following findings high- ables, and videotaped changes in natural settings based on

light process issues relating to the four required principles of the current paradigm. Measures considered sensitive to

an RCT rather than focusing on quantitative outcome data: change had effect sizes that ranged from 0.29 to 2.16. As a

(a) inclusion criteria, (b) a manualized approach and fidelity pilot study of 30 children, outcomes with effect sizes larger

to treatment, (c) sensitive and appropriate outcome mea- than 0.53 could be detected with 80% power (Type I error

sures, and (d) procedures for rigorous methodology. rate = .05). The measures in Table 3 warrant use in future

randomized clinical pilot studies. Conclusions about relia-

Inclusion Criteria bility of which measures demonstrated reliable changes are

Inclusion was based on the master clinician’s global impres- tentative due to multiple comparisons (e.g., the probability

sion of SMD. The quantitative use of both the Short Sen- exists that some significant differences occurred by chance).

sory Profile (McIntosh, Miller, Shyu, & Dunn, 1999) and

EDR also was piloted as inclusion criteria with promising Rigorous Methodology

but not definitive results. Further study of both measures is Myriad unexpected challenges occurred; for example, the

indicated to refine cut points for subject inclusion in future long wait time for Internal Review Board approval, the num-

studies. ber of canceled appointments due to illness and vacations, the

maintenance of a complex database, and staff turnover. In

Replicable Treatment short, this study took much longer than anticipated; however,

A preliminary intervention manual was completed and it provided extensive information about methodological

published for use in future studies (Miller et al., 2002). A sources of error to control in future RCT studies.

fidelity rating scale was piloted. Additional work is indi-

cated to refine both measures.

Discussion

Outcome Measures This study highlights the need for pilot studies to inform

A large number of outcome variables were studied to deter- the process of RCTs before implementation. The design

mine which were most sensitive to change. Paired t-test and implementation of rigorous research require time,

Table 3. Results of Single Group Pilot Study

Pretest Posttest Change Effect Size

Measure N Mean SD N Mean SD N Mean SD (p value)

Leiter–R

Attention 24 5.88 1.94 22 6.32 1.94 21 0.43 1.47 0.29 (0.20)

Cognitive/Social 24 76.83 10.59 22 80.32 12.62 21 3.57 7.09 0.50 (0.03)

SSP

Total Score 30 –3.39 1.92 27 –0.39 1.09 27 3.11 1.92 1.62 (< 0.001)

Vineland

Socialization 24 79.04 12.66 19 89.47 14.41 19 11.95 14.51 0.82 (0.002)

CBCL

Externalizing 30 60.93 9.79 21 56.95 11.26 21 –4.19 7.83 0.54 (0.02)

Internalizing 30 61.57 10.51 21 57.48 12.10 21 –3.67 8.61 0.43 (0.07)

GAS 27 30.37 1.17 27 55.68 11.46 27 25.31 11.71 2.16 (< 0.001)

Note. Leiter–R = Leiter International Performance Scale–Revised: Parent Rating Scale (Roid & Miller, 1997); SSP = Short Sensory Profile (McIntosh, Miller, Shyu, &

Dunn, 1999); Vineland = Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale (Stinnett, Havey, & Oehler-Stinnett, 1994); CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991); GAS =

goal attainment scaling (Kiresuk, Smith, & Cardillo, 1994).

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 165

stamina, and patience. Outcome research is a long-term pilot study, the authors plan to conduct a pilot RCT before

process, not a single project, as is typical of previous litera- conducting a large-scale RCT study. Researchers interested

ture. The contradictory results in the previous 80 studies are in occupational therapy effectiveness research should imple-

likely due to a lack of pilot research. In summary, the fol- ment pilot studies that build on each other instead of

lowing crucial lessons were learned relative to the four attempting to do the “one perfect” study. Only by building

essential principles for conducting rigorous RCTs. programmatic research can a body of knowledge be created

to move the empirical basis of the profession forward. ▲

Defining a Homogeneous Group

Inclusion criteria identifying a homogeneous group of chil- Note

dren is crucial. A combination of a behavioral measure and 1

In a later iteration, the first author modified the name STEP–SI to “A

a physiologic measure appears useful. However, further SECRET” (Miller, 2006). Using “A SECRET,” the parent is taught the

research is needed to determine cut points for participant therapy “secrets” that regulate the specific child, increase his or her social

inclusion. participation and self-confidence or self-esteem, and then address other

specific occupational goals of the family.

Establishing a Manualized Approach to Intervention

The intervention methodology was refined and published Acknowledgments

(Miller et al., 2002). With subsequent NIH funding,

First and foremost, the authors thank the children and their

researchers from five sites around the United States con-

parents who participated in this study. Without the gifted

tinue to work on the manualized approach for OT-SI treat-

therapists at The Children’s Hospital of Denver, who imple-

ment for future effectiveness research. A study of the relia-

mented the occupational therapy, this study would not have

bility and validity of the fidelity to treatment measure is

been completed: Julie Butler, Becky Greer, Corrine Jack,

forthcoming (Parham et al., 2007).

Nicki Pine, Robin Seger, Tracy Stackhouse, Clare Summers,

Choosing Sensitive and Appropriate Outcomes Sharon Trunnel, and Julie Wilbarger. The KID Foundation

and the STAR Center staff, who worked tirelessly over 10

Many outcome measures were evaluated to determine sen-

years to obtain the preliminary information needed to com-

sitivity in detecting improvement over 10 weeks. The fol-

plete this project, made invaluable and priceless personal sac-

lowing measures showed the most potential for future

rifices and major contributions, particularly Jude McGrath.

study: the total test score of the Short Sensory Profile

In addition, we thank the graduate school faculty and stu-

(McIntosh, Miller, Shyu, & Dunn, 1999), the GAS (Kire-

dents of Thomas Jefferson University, Occupational Ther-

suk et al., 1994), the Socialization subtest of the Vineland

apy Department, for their efforts related to coding the video-

Adaptive Behavior Scale (Stinnett et al., 1994), the com-

tapes. We also thank Barbara Brett-Green, Janice Burke,

posite scales of the CBCL (Achenbach, 1991), and the

Ellen Cohn, Jane Koomar, Zoe Mailloux, Teresa May-

Attention subtests and Cognitive/Social Composite of the

Benson, Diane Parham, Susanne Smith Roley, and Clare

Leiter International Performance Scale–Revised: Parent

Summers for contributing ideas about goal attainment

Rating Scale (Roid & Miller, 1997). Identifying specific

scaling and the OT-SI treatment protocol and fidelity

outcome measures from the large array field tested decreases

measure. Primary funding for this work was provided by an

spurious findings for future studies.

NIH Mentored Research Scientist Development Award

The GAS showed the most prepost change during the

(1K01HD001183-01A1), the Wallace Research Founda-

pilot study, was well received by parents, and captured the

tion, and the American Occupational Therapy Foundation.

outcomes of most import to families (Cohn, 1999). Addi-

Additional support was provided by an R21 NIH One-Year

tional research has been undertaken to study the reliability

Planning grant (#1 R21 HD41614-01), the General Clini-

and validity of the GAS with this population (Mailloux et

cal Research Centers Program at The Children’s Hospital

al., 2007).

(#M01 RR00069), The Children’s Hospital Research Insti-

Using Rigorous Methodology tute Scholar Award, and the Coleman Institute for Cogni-

tive Disabilities research fellowship.

Procedures that can be implemented in the next study to

assure increased rigor in research design and methodology

were defined. Of utmost importance is randomization to an References

active or a passive treatment control. Abikoff, H. (2001). Tailored psychosocial treatments for ADHD:

This article shows the importance of conducting pilot The search for a good fit. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology,

effectiveness studies. Using knowledge gleaned from this 30, 122–125.

166 March/April 2007, Volume 61, Number 2

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the Child Behavior Check- Forbes, D. A. (1998). Goal attainment scaling. A responsive mea-

list/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Ver- sure of client outcomes. Journal of Gerontological Nursing,

mont, Department of Psychiatry. 24(12), 34–40.

Ahn, R. R., Miller, L. J., Milberger, S., & McIntosh, D. N. Hoehn, T. P., & Baumeister, A. A. (1994). A critique of the appli-

(2004). Prevalence of parents’ perceptions of sensory pro- cation of sensory integration therapy to children with learning

cessing disorders among kindergarten children. American disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 27(6), 338–350.

Journal of Occupational Therapy, 58, 287–302. Interdisciplinary Council on Developmental and Learning Disor-

Altman, J. S., & Mills, B. C. (1990). Caregiver behaviors and ders. (2005). Diagnostic manual for infancy and early child-

adaptive behaviors in home care and daycare. Early Child hood: Mental health, developmental, regulatory–sensory process-

Development and Care, 62, 87–96. ing and language disorders and learning challenges

Arendt, R. E., MacLean, W. E., & Baumeister, A. A. (1988). Cri- (ICDL–DMIC). Bethesda, MD: Author.

tique of sensory integration therapy and its application in Jensen, P. S., Wantanabe, H. K., Richters, J. E., & Roper, M.

mental retardation. American Journal on Mental Retardation, (1996). Scales, diagnosis, and child psychopathology: Com-

92, 401–411. paring the CBCL and the DISC against external validators.

Ayres, A. J. (1972). Sensory integration and learning disorders. Los Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24, 151–168.

Angeles: Western Psychological Services. Joyce, B. M., Rockwood, K. J., & Mate-Kole, C. C. (1994). Use

Ayres, A. J. (1989). Sensory Integration and Praxis Tests. Los Ange- of goal attainment scaling in brain injury in a rehabilitation

les: Western Psychological Services. hospital. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabil-

Barkley, R. A., & Murphy, K. (1998). Attention-deficit hyper- itation, 73(1), 10–14.

activity disorder: A clinical workbook (2nd ed.). New York: Kazdin, A. E. (1994). Methodology, design, and evaluation in

Guilford. psychotherapy research. In A. E. Bergin & S. L. Garfield

Blanche, E. I. (2002). Observations based on sensory integration (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (4th

therapy. Torrance, CA: Pediatric Therapy Network. ed., pp. 19–71). New York: Wiley.

Boruch, R. F. (1997). Randomized experiments for planning and Kinnealey, M. (1998). Princess or tyrant: A case report of a child

evaluation: A practical guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. with sensory defensiveness. Occupational Therapy Interna-

Carte, E., Morrison, D., Sublett, J., Uemura, A., & Setrakian, W. tional, 5, 293–303.

(1984). Sensory integration therapy: A trial of a specific neu- Kinnealey, M., & Fuiek, M. (1999). The relationship between

rodevelopmental therapy for the remediation of learning dis- sensory defensiveness, anxiety, depression, and perception of

abilities. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, pain in adults. Occupational Therapy International, 6,

5, 189–194. 195–206.

Chen, W. J., Faraone, S. V., Biederman, J., & Tsuang, M. T. Kiresuk, T., & Sherman, R. (1968). Goal attainment scaling: A

(1994). Diagnostic accuracy of the Child Behavior Checklist general method of evaluating comprehensive mental health

scales for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A receiver- programs. Community Mental Health Journal, 4, 443–453.

operating characteristic analysis. Journal of Counseling and Kiresuk, T. J., Smith, A., & Cardillo, J. E. (1994). Goal attain-

Clinical Psychology, 62, 1017–1025. ment scaling: Applications, theory, and measurement. Hillsdale,

Close, W., Carpenter, M., & Cibiri, S. (1986). An evaluation NJ: Erlbaum.

study of sensory motor therapy for profoundly retarded Koomar, J. A., & Bundy, A. C. (2002). Creating direct interven-

adults. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 53, tion from theory. In A. C. Bundy, S. J. Lane, & E. A. Mur-

259–264. ray (Eds.), Sensory integration: Theory and practice (2nd ed.,

Cohn, E. (1999). Parental perception of the effects of occupational pp. 261–308). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis.

therapy using sensory integration approaches for their school- Lofland, J., & Lofland, L. H. (1995). Analyzing social settings: A

aged children and families. Unpublished dissertation, Boston guide to qualitative observation and analysis. Belmont, CA:

University, Sargent College of Allied Health Professions, Wadsworth.

Boston, MA. Macmann, G. M., Barnett, D. W., Burd, S. A., & Jones, T.

Cohn, E., Miller, L. J., & Tickle-Degnen, L. (2000). Parental (1992). Construct validity of the Child Behavior Checklist:

hopes for therapy outcomes: Children with sensory modula- Effects of item overlap on second-order factor structure. Psy-

tion disorders. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 54, chological Assessment, 4(1), 113–116.

36–43. Mailloux, Z. K., May-Benson, T. A., Summers, C. A., Miller, L.

DePauw, K. P. (1978). Enhancing the sensory integration of J., Brett-Green, B., Burke, J. P., et al. (2007). A goal attain-

aphasic students. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 11(3), ment scaling as a measure of meaningful outcomes for chil-

29–33. dren with sensory integration disorders. American Journal of

Douhitt, V. L. (1992). A comparison of adaptive behavior in Occupational Therapy, 61, 254–259.

gifted and non-gifted children. Roeper Review, 14, 149–151. Malec, J. F. (2001). Impact of comprehensive day treatment on

Dunn, W. (1999). The sensory profile: Examiner’s manual. San societal participation for persons with acquired brain injury.

Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 82,

Elliott, S. N., & Busse, R. T. (1992). Review of the Child Behav- 885–895.

ior Checklist. In J. Kramer & J. C. Conoley (Eds.), Mental Mangeot, S. D., Miller, L. J., McIntosh, D. N., McGrath-

measurements yearbook (Vol. 11, pp. 166–169). Lincoln, NE: Clarke, J., Simon, J., Hagerman, R. J., et al. (2001). Sensory

Buros Institute of Mental Measurement. modulation dysfunction in children with attention deficit

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 167

hyperactivity disorder. Developmental Medicine and Child (Eds.), Sensory integration: Theory and practice (2nd ed., pp.

Neurology, 43, 399–406. 435–451). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis.

March, J. (1995). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Mooney, K. C. (1984). Review of the Child Behavior Checklist.

New York: Guilford. In D. Keyser & R. Sweetland (Eds.), Test critiques (Vol. 1, pp.

March, J. (1997). Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children. 168–184). Kansas City, MO: Westport.

New York: Multi-Health Systems. MTA Cooperative Group. (1999). A 14-month randomized clin-

Mattingly, C. (1991). The narrative nature of clinical reasoning. ical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/

American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45, 998–1005. hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56,

McIntosh, D. N., Miller, L. J., Shyu, V., & Dunn, W. (1999). 1073–1086.

Overview of the Short Sensory Profile (SSP). In W. Dunn Ottenbacher, K. (1982). Sensory integration therapy: Affect or

(Ed.), The sensory profile: Examiner’s manual (pp. 59–73). effect? American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 36,

San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. 571–578.

McIntosh, D. N., Miller, L. J., Shyu, V., & Hagerman, R. (1999). Ottenbacher, K., & Cusick, A. (1993). Discriminative versus

Sensory-modulation disruption, electrodermal responses, evaluative assessment: Some observations on goal attainment

and functional behaviors. Developmental Medicine and Child scaling. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 47,

Neurology, 41, 608–615. 349–354.

Miller, L. J. (1988). Miller Assessment for Preschoolers (MAP). San Palisano, R. J. (1993). Validity of goal attainment scaling in

Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. infants with motor delays. Physical Therapy, 73, 651–660.

Miller, L. J. (1993). FirstSTEP (Screening Test for Evaluating Pre- Parham, L. D., Cohn, E. S., Spitzer, S., Koomar, J. A., Miller, L.,

schoolers): Manual. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation. Burke, J. P., et al. (2007). Fidelity in sensory integration

Miller, L. J. (2006). Sensational kids: Help and hope for children intervention research. American Journal of Occupational

with sensory processing disorder. New York: Putnam. Therapy, 61, 216–227.

Miller, L. J., Lane, S. J., Cermak, S., Anzalone, M., Osten, E., & Parham, L. D., & Mailloux, Z. (2001). Sensory integration. In J.

Greenspan, S. (2005). Appendix III: Guide for observations Case-Smith (Ed.), Occupational therapy for children (4th ed.,

during clinical evaluation of Regulatory–Sensory Processing pp. 329–381). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Disorders: Version 1.0. In S. I. Greenspan & S. Wieder Pfeiffer, B., & Kinnealey, M. (2003). Treatment of sensory defen-

(Eds.), Diagnostic manual for infancy and early childhood: siveness in adults. Occupational Therapy International, 10,

Mental health, developmental, regulatory–sensory processing 175–184.

and language disorders and learning challenges (ICDL–DMIC) Polatajko, H. J., Kaplan, B. J., & Wilson, B. N. (1992). Sensory

(pp. 289–327). Bethesda, MD: Interdisciplinary Council on integration treatment for children with learning disabilities:

Developmental and Learning Disorders. Its status 20 years later. Occupational Therapy Journal of

Miller, L. J., McIntosh, D. N., McGrath, J., Shyu, V., Lampe, M., Research, 12, 323–341.

Taylor, A. K., et al. (1999). Electrodermal responses to sen- Polatajko, H. J., Law, M., Miller, J., Schaffer, R., & Macnab, J.

sory stimuli in individuals with Fragile X syndrome: A pre- (1991). The effect of a sensory integration program on aca-

liminary report. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 83, demic achievement, motor performance, and self-esteem in

268–279. children identified as learning disabled: Results of a clinical

Miller, L. J., Reisman, J. E., McIntosh, D. N., & Simon, J. trial. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research, 11, 155–176.

(2001). An ecological model of sensory modulation: Perfor- Portney, L. G., & Watkins, M. P. (2000). Foundations of clinical

mance of children with Fragile X syndrome, autism, atten- research: Applications to practice (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle

tion-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and sensory modulation River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

dysfunction. In S. S. Roley, E. I. Blanche, & R. C. Schaaf Rockwood, K., Joyce, B., & Stolee, P. (1997). Use of goal attain-

(Eds.), Understanding the nature of sensory integration with ment scaling in measuring clinically important change in

diverse populations (pp. 57–88). San Antonio, TX: Therapy cognitive rehabilitation patients. Journal of Clinical Epidemi-

Skill Builders. ology, 50, 581–588.

Miller, L. J., Robinson, J., & Moulton, D. (2004). Sensory mod- Rockwood, K., Stadnyk, K., Carver, D., MacPherson, K. M.,

ulation dysfunction: Identification in early childhood. In R. Beanlands, H. E., Powell, C., et al. (2000). A clinimetric

DelCarmen-Wiggins & A. Carter (Eds.), Handbook of evaluation of specialized geriatric care for rural dwelling, frail

infant, toddler, and preschool mental health assessment (pp. older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48,

247–270). New York: Oxford University Press. 1080–1085.

Miller, L. J., & Summers, C. (2001). Clinical applications in sen- Roid, G. H., & Miller, L. J. (1997). Leiter International Perfor-

sory modulation dysfunction: Assessment and intervention mance Scale–Revised. Wood Dale, IL: Stoelting.

considerations. In S. S. Roley, E. I. Blanche, & R. C. Schaaf Rosenbaum, P., Saigal, S., Szatmari, P., & Hoult, L. (1995).

(Eds.), Understanding the nature of sensory integration with Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales as a summary of func-

diverse populations (pp. 247–274). San Antonio, TX: Ther- tional outcomes of extremely low birthweight children.

apy Skill Builders. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 37, 577–586.

Miller, L. J., Wilbarger, J. L., Stackhouse, T. M., & Trunnell, S. Rushton, P. W., & Miller, W. C. (2002). Goal attainment scaling

L. (2002). Use of clinical reasoning in occupational therapy: in the rehabilitation of patients with lower-extremity ampu-

The STEP-SI Model of Treatment of Sensory Modulation tations: A pilot study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Reha-

Dysfunction. In A. C. Bundy, S. J. Lane, & E. A. Murray bilitation, 83, 771–775.

168 March/April 2007, Volume 61, Number 2

Schaaf, R. C., & Miller, L. J. (2005). Occupational therapy using attention deficit disorder: Importance of a blinded placebo

a sensory integrative approach for children with develop- evaluation. Clinical Pediatrics, 25, 594–599.

mental disabilities. Mental Retardation and Developmental Ullmann, R. K., Sleator, E. K., & Sprague, R. L. (1984). ADD

Disabilities Research Reviews, 11, 143–148. children: Who is referred from the schools? Psychopharma-

Schaaf, R. C., Miller, L. J., Martello, T., Faulkner, J., Girardi, K., cology Bulletin, 20, 308–312.

Houtras, A., et al. (2001). Changes in play behavior during Ullmann, R. K., Sleator, E. K., & Sprague, R. L. (1991). ADD-

sensory integration intervention. Poster presented at the Amer- H Comprehensive Teacher’s Rating Scale (2nd ed.). Cham-

ican Occupational Therapy Association 81st Annual Confer- paign, IL: MetriTech.

ence & Expo, Philadelphia. Vargas, S., & Camilli, G. (1999). A meta-analysis of research on

Schaffer, R. (1984). Sensory integration therapy with learning sensory integration treatment. American Journal of Occupa-

disabled children: A critical review. Canadian Journal of tional Therapy, 53, 189–198.

Occupational Therapy, 51, 73–77. Voelker, S. L., Shore, D. L., & Brown-More, C. (1990). Validity

Silverman, W. K., LaGreca, A. M., & Wasserstein, S. (1995). of self-report of adaptive behavior skills by adults with men-

What do children worry about? Worries and their relation to tal retardation. Mental Retardation, 28, 305–309.

anxiety. Child Development, 66, 671–686. Werry, J. S., Scaletti, R., & Mills, F. (1990). Sensory integration

Stinnett, T. A., Havey, J. M., & Oehler-Stinnett, J. (1994). Cur- and teacher-judged learning problems: A controlled inter-

rent test usage by practicing school psychologists: A national vention trial. Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health, 26,

survey. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 12, 331–350. 31–35.

Stolee, P., Rockwood, K., Fox, R. A., & Streiner, D. L. (1992). White, M. (1979). A first-grade intervention program for chil-

The use of goal attainment scaling in a geriatric care setting. dren at risk for reading failure. Journal of Learning Disabili-

Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 40, 574–578. ties, 12(4), 26–32.

Ullmann, R. K., & Sleator, E. K. (1985). Attention deficit disor- Wodrich, D. L., & Barry, C. T. (1991). A survey of school psy-

der children with or without hyperactivity. Clinical Pedi- chologists’ practices for identifying mentally retarded stu-

atrics, 24, 547–551. dents. Psychology in the Schools, 28, 165–171.

Ullmann, R. K., & Sleator, E. K. (1986). Responders, nonre- Zero to Three. (2005). Diagnostic classification: 0-3–Revised.

sponders, and placebo responders among children with Arlington, VA: National Center for Clinical Infant Programs.

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 169

Вам также может понравиться

- Evidence-Based Practice in Pediatric Physical Therapy by BarryДокумент14 страницEvidence-Based Practice in Pediatric Physical Therapy by BarryFe TusОценок пока нет

- ASCO-SEP Medical Oncology Self-Evaluation Program, 7e by ASCOДокумент730 страницASCO-SEP Medical Oncology Self-Evaluation Program, 7e by ASCOandrei vladОценок пока нет

- Budson - Memory Loss, Alzheimer's Disease, and Dementia - 2 Ed - 2015Документ283 страницыBudson - Memory Loss, Alzheimer's Disease, and Dementia - 2 Ed - 2015Nathaly Cantor100% (3)

- Company ProfileДокумент6 страницCompany ProfileAhmed Eljenan100% (1)

- Pre-Post OT InterventionДокумент16 страницPre-Post OT InterventionIdanerlisОценок пока нет

- ARandomized Controlled Pilot Studyofthe Effectivenessof Occupational Therapyfor Children With Sensory Modulation DisorderДокумент12 страницARandomized Controlled Pilot Studyofthe Effectivenessof Occupational Therapyfor Children With Sensory Modulation Disordertayna santosОценок пока нет

- Mailloux May BensonДокумент6 страницMailloux May BensonAnup Pednekar100% (1)

- Jurnal - Designing Research Study On Psikosos Intervention in AutismДокумент14 страницJurnal - Designing Research Study On Psikosos Intervention in AutismKlinik Psikologi RSBSОценок пока нет

- Terapia BreveДокумент18 страницTerapia BreveFanny ZumárragaОценок пока нет

- Effectiveness of Paediatric Occupational Therapy For Chidren With Disabilities A Systematic ReviewДокумент16 страницEffectiveness of Paediatric Occupational Therapy For Chidren With Disabilities A Systematic ReviewCynthia RodriguesОценок пока нет

- Occupational Therapy and Mental Health 1Документ18 страницOccupational Therapy and Mental Health 1Roman -Оценок пока нет

- Psihologia PozitivaДокумент10 страницPsihologia PozitivaClaudiaClotanОценок пока нет

- Hippotherapy ResearchДокумент7 страницHippotherapy Researchapi-282753416Оценок пока нет

- 1 Running Head: Research Methods and ApproachesДокумент6 страниц1 Running Head: Research Methods and ApproachesGeorge MainaОценок пока нет

- Research Article CritiqueДокумент8 страницResearch Article Critiqueapi-654257930Оценок пока нет

- Hsieh2015 PDFДокумент1 страницаHsieh2015 PDFDeana MonicaОценок пока нет

- Fidelity MeasureДокумент12 страницFidelity MeasureMarta FerreiraОценок пока нет

- Hoag Wood 1995Документ5 страницHoag Wood 1995Alexandru NaeОценок пока нет

- Articulo GASДокумент6 страницArticulo GASFernando JaqueОценок пока нет

- Matson 2007Документ12 страницMatson 2007Lia Lores GontijoОценок пока нет

- Geront/gnu 018Документ10 страницGeront/gnu 018Cristina MPОценок пока нет

- Child and Adolescent Psychological Assessment CurrДокумент9 страницChild and Adolescent Psychological Assessment CurrArif Erdem KöroğluОценок пока нет

- Assessing Clinical SignificanceДокумент8 страницAssessing Clinical SignificancePánico FaunoОценок пока нет

- Critical Appraisal The ApplicabilityДокумент32 страницыCritical Appraisal The ApplicabilityTalha Basharat AliОценок пока нет

- Cashel, M.L. (2002) - Child and Adolescent Psychological Assessment. Current Clinical Practices and The Impact of Managed CareДокумент8 страницCashel, M.L. (2002) - Child and Adolescent Psychological Assessment. Current Clinical Practices and The Impact of Managed CareRicardo NarváezОценок пока нет

- tAN, 2018Документ8 страницtAN, 2018Astrith Hernández MendozaОценок пока нет

- Dr. Suneeta Monga, From Research To PracticeДокумент4 страницыDr. Suneeta Monga, From Research To PracticeU of T MedicineОценок пока нет

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy For Adult Anxiety Disorders in Clinical Practice: A Meta-Analysis of Effectiveness StudiesДокумент13 страницCognitive-Behavioral Therapy For Adult Anxiety Disorders in Clinical Practice: A Meta-Analysis of Effectiveness StudiesMaria Inês de AzevedoОценок пока нет

- 20151006221010LECTURE 1 - Feb2015Документ60 страниц20151006221010LECTURE 1 - Feb2015thinagaranОценок пока нет

- Stimsonm Researchcritiquen531Документ11 страницStimsonm Researchcritiquen531api-270067627Оценок пока нет

- Ebp Final DraftДокумент14 страницEbp Final Draftapi-436039292Оценок пока нет

- Clase 1 Lambert Et Al. - 1996 - The Reliability and Validity of The Outcome QuestionnaireДокумент11 страницClase 1 Lambert Et Al. - 1996 - The Reliability and Validity of The Outcome QuestionnaireLuis GaribottiОценок пока нет

- Critically Appraised Topics 23june2014Документ33 страницыCritically Appraised Topics 23june2014filchibuffОценок пока нет

- Efficacy of Theory-Based Interventions To Promote Physical Activity. A Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled TrialsДокумент18 страницEfficacy of Theory-Based Interventions To Promote Physical Activity. A Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled TrialsLin Tzu-yuОценок пока нет

- Effects of Distraction On Children's Pain and Distress During Medical Procedures A Meta-AnalysisДокумент4 страницыEffects of Distraction On Children's Pain and Distress During Medical Procedures A Meta-AnalysisMiguel TuriniОценок пока нет

- Youngstrom 2016Документ21 страницаYoungstrom 2016gabrielaОценок пока нет

- Evidence Based Medicine Series: Part 3. Appraising The Evidence Are The Results Valid and Clinically Important?Документ6 страницEvidence Based Medicine Series: Part 3. Appraising The Evidence Are The Results Valid and Clinically Important?Ice Bear JJОценок пока нет

- Child Adoles Ment Health - 2010 - Holmes - The Diagnostic Utility of Executive Function Assessments in The Identification PDFДокумент7 страницChild Adoles Ment Health - 2010 - Holmes - The Diagnostic Utility of Executive Function Assessments in The Identification PDFJúlia JanoviczОценок пока нет

- Developing and Modifying Behavioral Coding Schemes in Pediatric Psychology: A Practical GuideДокумент11 страницDeveloping and Modifying Behavioral Coding Schemes in Pediatric Psychology: A Practical GuideSergio A. Dávila SantanaОценок пока нет

- 1 Lecture IntДокумент37 страниц1 Lecture IntAbiodunOlaiyaPaulОценок пока нет

- Attention Process TrainingДокумент22 страницыAttention Process TrainingLara Perez MurciaОценок пока нет

- Research Critique On The Effects of Baby Massage On Attachment Between Mother and Their InfantsДокумент6 страницResearch Critique On The Effects of Baby Massage On Attachment Between Mother and Their Infantsbridj09Оценок пока нет

- U03d2 Ethics, Recruitment, and Random AssignmentДокумент6 страницU03d2 Ethics, Recruitment, and Random Assignmentarhodes777Оценок пока нет

- Ireland Clough Day 2017Документ21 страницаIreland Clough Day 2017ShilpaОценок пока нет

- Slocum (2014) The EBP of Applied Behavior AnalysisДокумент16 страницSlocum (2014) The EBP of Applied Behavior Analysis6ybczp6t9bОценок пока нет

- Meyer - Psychological Testing and Psychological AssessmentДокумент38 страницMeyer - Psychological Testing and Psychological AssessmentSpikeThePenguin100% (1)

- Mental Health Services Research Methodology 2002Документ8 страницMental Health Services Research Methodology 2002Kats CoelloОценок пока нет

- Borckardt Et Al 2013Документ16 страницBorckardt Et Al 2013Marilia PachecoОценок пока нет

- DownloadДокумент18 страницDownloadying reenОценок пока нет

- Child Adoles Ment Health - 2010 - Holmes - The Diagnostic Utility of Executive Function Assessments in The IdentificationДокумент7 страницChild Adoles Ment Health - 2010 - Holmes - The Diagnostic Utility of Executive Function Assessments in The IdentificationMarily MatamorosОценок пока нет

- Stirman CPSP 2017Документ26 страницStirman CPSP 2017Link079Оценок пока нет

- Research Assessing Consumer Satisfaction With Mental Health T Atment: A Review of FindingsДокумент26 страницResearch Assessing Consumer Satisfaction With Mental Health T Atment: A Review of FindingsFanni VikorОценок пока нет

- Sargeant (2009)Документ12 страницSargeant (2009)Mathé DuistermaatОценок пока нет

- Journal Presentation: By, R.Angelin Thangam Bot Final YearДокумент50 страницJournal Presentation: By, R.Angelin Thangam Bot Final YearAarthi ArumugamОценок пока нет

- Acfrogablxota17ubsxnocf0sulcs0yxzk1ieqobaba89fhirrp9afgxsi M9trrmjbw59ygqyimsoeb8 Osuisry2soyu6xf3uboxnu6h6m-90ibt61hjz-Uiufefcefptktzfol3ccisa W VJДокумент5 страницAcfrogablxota17ubsxnocf0sulcs0yxzk1ieqobaba89fhirrp9afgxsi M9trrmjbw59ygqyimsoeb8 Osuisry2soyu6xf3uboxnu6h6m-90ibt61hjz-Uiufefcefptktzfol3ccisa W VJKarylle RiveroОценок пока нет

- CM1 PPTДокумент66 страницCM1 PPTMichaella “hideyoshi girl” DavisОценок пока нет

- My H Retal 07 Suitability PDFДокумент13 страницMy H Retal 07 Suitability PDFangiedore48Оценок пока нет

- Chorpita Et Al (2011) - Evidence-Based Treatment For ChildrenДокумент19 страницChorpita Et Al (2011) - Evidence-Based Treatment For ChildrenJaviera Luna Marcel Zapata-SalazarОценок пока нет

- Goal Attainment Scaling As A Measure of MeaningfulДокумент7 страницGoal Attainment Scaling As A Measure of MeaningfulCarlhos Waliithoo Muñoz JimenezОценок пока нет

- Barnett 2017Документ8 страницBarnett 2017Madalina StancuОценок пока нет

- NIH Public AccessДокумент31 страницаNIH Public AccessLuciana MarinОценок пока нет

- Kausalitas, Randomisasi, GeneralisasiДокумент22 страницыKausalitas, Randomisasi, GeneralisasiGiriОценок пока нет

- Concise Biostatistical Principles & Concepts: Guidelines for Clinical and Biomedical ResearchersОт EverandConcise Biostatistical Principles & Concepts: Guidelines for Clinical and Biomedical ResearchersОценок пока нет

- Teoria Feeding PDFДокумент33 страницыTeoria Feeding PDFNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- 10 Station Sensory Motor WalkДокумент18 страниц10 Station Sensory Motor WalkNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- JPGN-17-205 The Pediatric Eating Assessment Tool PDFДокумент7 страницJPGN-17-205 The Pediatric Eating Assessment Tool PDFNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- Feeding Problems in Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersДокумент15 страницFeeding Problems in Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersNina Salinas100% (1)

- Perspectiva Del JuegoДокумент12 страницPerspectiva Del JuegoNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- The Children Eating Behavior Inventory CebiДокумент15 страницThe Children Eating Behavior Inventory CebiNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- Estudio Sobre Los Problemas A La Hora de Comer de Niños Con AutismoДокумент18 страницEstudio Sobre Los Problemas A La Hora de Comer de Niños Con AutismoNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- Investigate The Support For SubtypesДокумент12 страницInvestigate The Support For SubtypesNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- Modulacion Sensorial T Desordenes Emocional en AspergerДокумент11 страницModulacion Sensorial T Desordenes Emocional en AspergerNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- Sensory Feeding InterventionДокумент59 страницSensory Feeding InterventionNina Salinas100% (1)

- The Effect of Sound-Based Intervention On Children With Sensory Processing Disorders and Visual-Motor DelaysДокумент7 страницThe Effect of Sound-Based Intervention On Children With Sensory Processing Disorders and Visual-Motor DelaysPatricia BarbosaОценок пока нет

- Development of An Assessment For Ideational Praxis: Teresa A. May-Benson, Sharon A. CermakДокумент6 страницDevelopment of An Assessment For Ideational Praxis: Teresa A. May-Benson, Sharon A. CermakNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- Como Es Afectado El Juego Por Problemas de Integracion SensorialДокумент8 страницComo Es Afectado El Juego Por Problemas de Integracion SensorialNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- TowardaConcensus Part2 PDFДокумент3 страницыTowardaConcensus Part2 PDFNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- Como Es Afectado El Juego Por Problemas de Integracion SensorialДокумент8 страницComo Es Afectado El Juego Por Problemas de Integracion SensorialNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- Fine Motor Skills Checklist PacketДокумент8 страницFine Motor Skills Checklist PacketNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- 1992 Quest ManualДокумент88 страниц1992 Quest ManualNina SalinasОценок пока нет

- MEDICA 2020 Genoray Co. Ltd. Exhibitor Medcom2020.2676603 7Px5aD3AReyrRpKpuUJSrQДокумент30 страницMEDICA 2020 Genoray Co. Ltd. Exhibitor Medcom2020.2676603 7Px5aD3AReyrRpKpuUJSrQxrayserviceОценок пока нет

- Community Health Nursing Vs Public Health NursingДокумент1 страницаCommunity Health Nursing Vs Public Health NursingAnnalisa Telles100% (2)

- WHO Technical Report Series 1013Документ60 страницWHO Technical Report Series 1013kamishahОценок пока нет

- 2022 AJOG A Laparoscopic Approach To Cesarean Scar Ectopic PregnancyДокумент3 страницы2022 AJOG A Laparoscopic Approach To Cesarean Scar Ectopic PregnancyWilliam AlvarezОценок пока нет

- Reaction Paper On The IntegumentaryДокумент2 страницыReaction Paper On The IntegumentaryCamile Elaine Borromeo NocheОценок пока нет

- Collaborative Practice Agreement 2024Документ3 страницыCollaborative Practice Agreement 2024marlontapit1115Оценок пока нет

- Anginal EquivalentДокумент20 страницAnginal Equivalentoki harisandiОценок пока нет

- HealthДокумент5 страницHealthAvtar Singh AtwalОценок пока нет

- Infant of Diabetic MotherДокумент17 страницInfant of Diabetic Motheral_humaira91Оценок пока нет

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Science in MedicineДокумент7 страницGestational Diabetes Mellitus: Science in MedicinerizqarrОценок пока нет

- GO Health Information StopДокумент2 страницыGO Health Information StopNixZ Teruel2Оценок пока нет

- DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF C-ARM MACHINE - Pptx.feem - Backup - 265248Документ11 страницDESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF C-ARM MACHINE - Pptx.feem - Backup - 265248TamilandaОценок пока нет

- Adult T-Cell Leukemia Lymphoma (Atll) A Rare Case Associated With Human T-Cell Virus (Htlv-1)Документ19 страницAdult T-Cell Leukemia Lymphoma (Atll) A Rare Case Associated With Human T-Cell Virus (Htlv-1)Priya ChandakОценок пока нет

- Lab FindingsДокумент3 страницыLab FindingsRonica GonzagaОценок пока нет

- Drug Use in Paeds and ElderlyДокумент27 страницDrug Use in Paeds and ElderlyCuthbert Tinotenda MusarurwaОценок пока нет

- Velez College Cebu City, Philippines: GEC - PC GEC - MMW Pmls 1Документ3 страницыVelez College Cebu City, Philippines: GEC - PC GEC - MMW Pmls 1Armyl Raul CanadaОценок пока нет

- AIA HealthShield Gold MaxДокумент16 страницAIA HealthShield Gold Maxmailer686Оценок пока нет

- Medication Guide Modafinil Tablets, Usp: (Moe Daf 100 MG and 200 MGДокумент2 страницыMedication Guide Modafinil Tablets, Usp: (Moe Daf 100 MG and 200 MGburger_man2Оценок пока нет

- Dexmet Vs LignocaineДокумент22 страницыDexmet Vs LignocaineDr.S.Easwaramoorthy IAGES Secretary 2020Оценок пока нет

- Bab 1Документ6 страницBab 1Yulia Putri RachmawatiОценок пока нет

- Malaria SlidesДокумент60 страницMalaria Slidescana geel 2018Оценок пока нет

- Achieving Sustainability in Reducing Unplanned Extubations in PICUДокумент7 страницAchieving Sustainability in Reducing Unplanned Extubations in PICUKevin Bazán TorrealvaОценок пока нет

- Indonesia Health SectorДокумент84 страницыIndonesia Health SectorBung RandiОценок пока нет

- Medication Safety Alerts: David UДокумент3 страницыMedication Safety Alerts: David UVina RulinaОценок пока нет

- Differential Diagnosis of Complex Liver Cysts.: Poster No.: Congress: Type: AuthorsДокумент20 страницDifferential Diagnosis of Complex Liver Cysts.: Poster No.: Congress: Type: Authorsrmo.rsusОценок пока нет

- Past Psychiatric History ExamplesДокумент11 страницPast Psychiatric History ExamplesEzra Denise Lubong RamelОценок пока нет