Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Cases

Загружено:

pgdl20110 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

342 просмотров4 страницыАвторское право

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

XLS, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате XLS, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

342 просмотров4 страницыCases

Загружено:

pgdl2011Авторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате XLS, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 4

Sane automatism requires total destruction of voluntary

AG's ref #2 (1992) control

The grounds for self defence need to be honestly believed,

Beckford v R (1988) but not reasonably believed

Prosecution may raise insanity in response to a plea of

automatism; any mental disorder manifesting in violence is

Bratty v AG for Northern Ireland (1963) `insanity', not automatism

Jury should be given an opportunity to consider whether

defendant's refusal to answer questions has reasonable

Condron v UK (2001) grounds

s.16 deception requires that dishonesty coincides with the

intention to deprive; the dishonesty must be cause of the

Davies v Flackett (1972) deprivation

DPP v Lynch (1975) Duress may be a defence to accomplice to murder

Voluntary intoxication not a defence to crime requiring no

DPP v Majewski (1977) specific intent

A mistaken, genuine belief in consent excuses, even if not

DPP v Morgan (1975) based on any reasonable grounds

Edwards v Ddin (1976) Making off without payment is not theft

Elliot v C (1983) Caldwell test for recklessness is entirely objective

For an indecent assault, the action need not be hostile or

Faulkner v Talbot (1981) agressive

Hyam v DPP (1974) `Intention' found in foresight of probable harm

Low self control not a characteristc of the ordinary person in

Luc Theit Than v R (1996) provocation (but see R v Smith(2000))

Murray v UK (1996) Right to silence not an absolute right under Art. 6

Insanity is a `defect of reason arising out of a disease of the

mind' such that the accused did not know the `nature and

M'Naghten's case (1843) quality' of the act, or did not know that it was wrong

For gross negligence manslaughter, it is for the jury to

decide whether the defendant's acts were bad enough to be

R v Adomako (1995) criminal

`Rough horseplay' is defence to charge of assault, even if

R v Aitken (1992) very dangerous

Conviction for conspiracy possible even if the conspired

R v Anderson (1986) outcome is not desired, or even possible

Constructive manslaughter requires a demonstrable unlawful

R v Arobieke (1988) act

R v Becerra and Cooper (1975) Withdrawal from joint enterprise requires timely notice

Provocation should not take into account physical

R v Bedder (1954) pecularities of the defendant (but see R v Camplin (1978))

Unwillingness to fight is not essential for defence of self

R v Bird (1985) defence, but should be taken into account by jury

R v Blaue (1975) Defendant takes his victim as he finds him

Whether consent negates assault depends on the harm

R v Boyea (1992) (objectively) likely to be caused

R v Brown (1993) Consent no defence to sadomasochistic injuries

For diminished responsibility, `abnormality of mind' winder

R v Byrne (1960) than M'Naghten insanity

Provocation can take into account age and gender as

R v Camplin (1978) characteristics of the `reasonable man'

Heroin is a `noxious thing'; injection of heroin can give rise to

R v Cato (1975) constructive manslaughter, even with consent

R v Chan-Fook (1994) Psychiatric illness can amount to bodily harm

Constructive manslaughter requires mens rea as to the

R v Church (1965) dangerous act

R v Clarence (1889) Mistake as to circumstances of act do not vitiate consent

For a trespassory entry, some part of the defendant's body

R v Collins (1972) must enter the building

R v Burstow and Ireland (1997) Psychiatric illness can amount to bodily harm

`Recklessness' is assessed objectively in criminal damage

R v Caldwell (1982) (now overruled by R v G)

Negligent medical treatment does not break the chain of

R v Cheshire (1991) causation; defendant's acts must a significant contribution.

`menaces' in blackmail must be sufficient to sway a person

of reasonable firmness, even if the victim himself was not

R v Clear (1967) swayed

Assault is indecent if defendant believes it indecent, or it is

R v Court (1989) obviously indecent

R v Cunninghman (1957) `Recklessness' is a state of mind of the defendant

Self-neglect does not break chain of causation; suicide does,

R v Dear (1996) but not if caused by the defendant

Obtaining by deception: deception must operate on the mind

R v Doukas (1977) of the victim

R v Dudley and Stevens (1884) Necessity no defence to murder

Self defence no defence when defendant not attacked, but

R v Duffy (1965) prevention of crime might be

It is an offence to aid and abet an attempt, but not to attempt

R v Dunnington (1983) to aid and abet

R v Eason (1971) Attempted theft not made out if indictment too narrow

R v Fagan (1969) Actus reus may extend beyond original act

Self-induced intoxication does not justify mistake as to

R v Fotheringham (1988) consent in rape

`menaces' in blackmail must be sufficient to sway a person

of reasonable firmness, or a particular timid victim if the

R v Garwood (1987) defendant new of his timidity

For attempt, evidence must be adduced to show that

R v Geddes (1996) defendant had started to implement the offence

Caldwell test for recklessness affirmed (now overruled by R

R v Gemmell (2003) v G)

`Dishonesty' is based on the defendant's understanding of

R v Ghosh (1982) the standards of ordinary people

`Administration' of a `noxious thing' does not require physical

R v Gillard (1988) contact

R v Gomez (1993) `Appropriation' can occur even if the victim consents

Duress requires a `sober person of reasonable firmness' to

R v Graham (1981) fear death or serious injury

For an attempt, the defendant must have `embarked on the

R v Gullefer (1986) crime'

Whether force was used `at the time of the theft' is a

R v Hale (1978) question for the jury

Using a false coin in a machine is not a deception, but it is a

R v Hands (1887) larceny

Stress and anxiety are not `external factors' that can give

R v Hennessey (1989) rise to a defence of automatism

R v Hinks (2000) Absolute title in civil law does not defeat `appropriation'

The standard for duress as a defence does not depend on

R v Horne (1994) the characteristics of the defendant

R v Howe (1977) Duress is not a defence to murder or accomplice to murder

Ommission my be culpable where the defendant has

R v Instan (1893) assumed a duty of care

Entry to premises is `as a trespasser' if it is for the purposes

R v Jones and Smith (1976) of theft

Negligent medical treatment might break the chain of

R v Jordan (1956) causation if it exceptionally bad

`Intention' is evidenced by, but not determined by, foresight

R v Hancock and Shankland (1986) of harm

Obtaining work by deception is an offence if the deception is

R v King (1986) the operative case

R v Kingston (1994) Involuntary intoxication not a defence if intent still present

Constructive manslaughter requires an unlawful act; the

R v Lamb (1967) mens rea for the unlawful act must be present

Presenting a credit card without authority to use

misrepresents that defendant is authorised; unauthorised

R v Lambie (1967) credit cards are the same as unauthorised cheques

R v Lawrence (1972) `Appropriation' can occur even if victim consents

Whether a substance is `noxious' is a question of fact and

R v Marcus (1981) degree

Duress of circumstances may apply when the threat is not

R v Martin (1989) against the defendant

Woollin direction for intention does not compel jury to accept

that foresight of virtually certain harm is determinative, it only

R v Matthews (2003) entitles the jury to do so

Ommission to act may be culpable if duty to act results from

R v Miller (1982) defendant's own actions

`Intention' found in foresight that harm is a `natural

R v Moloney (1985) consequence'

`Maliciously' in assault offences means only `intentionly or

R v Mowatt (1967) recklessly'

Appropriation in theft does not require assumption of all the

R v Morris (1983) rights of an owner, only some

R v Neddrick (1986) `Intention' is as defined in Hancock and Shankland

`Consent' is different to `acquiescence', but ordinarily this is

R v Olugboja (1981) not important to the jury

For self defence, the defendant must (subjectively) believe

R v Owino (1995) the force was (objectively) reasonable

R v Pittwood (1902) Liability for ommission may arise out of contractual obligation

Obtaining a cheque by deception is not `obtaining propery

by deception' because the thing-in-action represented by the

R v Preddy (1996) cheque always belongs to the payee

Caldwell test for recklessness is entirely objective, but a

reasonable person may overlook an obvious risk by being

R v Reid (1992) distracted

For purposes of consent, mistake as to qualifications not

R v Richardson (Diane) (1998) mistake as to identity

Voluntary intoxication no defence to assault, but may be

R v Richardson (Nigel) (1998) defence where there is a drunken belief in consent

Causation in assault found if events were reasonably

R v Roberts (1971) forseeable

Obtaining by deception: if the person deceived knows of the

R v Rozeik (1995) fraud, then obtaining is not by deception

A mistaken, genuine belief in consent excuses, even if not

R v Satnam v Kewal (1983) based on any reasonable grounds

R v Savage and Parmenter (1991) s.47 OAPA requires mens rea of assault

Duress no defence if defendant puts himself into a criminal

R v Shepherd (1987) conspiracy where threats are likely

No defence to a charge of attempt that the substantive

R v Shivpuri (1986) offence is actually impossible to commit

Whether consent negates assault depends on the harm

R v Slingsby (1992) (anticipated) likely to be caused

Jury should consider all aspects of the defendant when

assessing whether his response to provocation was

R v Smith (2000) reasonable

`Dangerous damage' under s.1(2) CDA requires intention or

recklessness towards danger caused by the damage, not by

R v Steer (1987) the way it is caused

Ommission my be culpable where the defendant has

R v Stone and Dobinson (1976) assumed a duty of care

Victims' mistake as to circumstances of act may vitiate

R v Tabassum (1889) consent

Jury should consider all aspects of the defendant when

assessing whether his response to provocation was

R v Weller (2003) reasonable, including irrational jealousy

There is a defence of duress of circumstances, if D is placed

R v Willer (1986) in immediate danger

Action in prevention of crime justified on the basis of

R v Williams (Gladstone) (1983) defendent's honestly held belief

Consent a defence to s.20 offence if it is classed as

R v Wilson (1996) `adornment'

R v Woolin (1998) `Intention' found in forsight that harm is virtually certain

Вам также может понравиться

- Anti-SLAPP Law Modernized: The Uniform Public Expression Protection ActОт EverandAnti-SLAPP Law Modernized: The Uniform Public Expression Protection ActОценок пока нет

- Civ Pro 1Документ42 страницыCiv Pro 1Rein DrewОценок пока нет

- Divorce: Why Fighting in Court Will Only Make You Both PoorerОт EverandDivorce: Why Fighting in Court Will Only Make You Both PoorerОценок пока нет

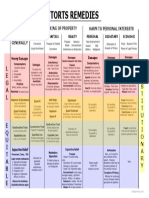

- Intentional Torts (Transferable) : Intent Is A Desire or Knowledge of Substantial Certainty That A Result Will Occur ElementsДокумент4 страницыIntentional Torts (Transferable) : Intent Is A Desire or Knowledge of Substantial Certainty That A Result Will Occur ElementsJohnny EmmОценок пока нет

- MBE & MEE Essentials: Governing Law for UBE Bar Exam ReviewОт EverandMBE & MEE Essentials: Governing Law for UBE Bar Exam ReviewОценок пока нет

- CONTRACTS OUTLINE - JamesДокумент65 страницCONTRACTS OUTLINE - JamesRebekahОценок пока нет

- Torts Case BriefsДокумент19 страницTorts Case BriefsWes HillОценок пока нет

- Unit 3 Introduction To Criminal LawДокумент31 страницаUnit 3 Introduction To Criminal Lawapi-334810559Оценок пока нет

- Torts Outline 2012Документ17 страницTorts Outline 2012cmm1221Оценок пока нет

- The Elements of Common Law Murder AreДокумент4 страницыThe Elements of Common Law Murder ArekrithikaОценок пока нет

- Articles On DamagesДокумент4 страницыArticles On DamagesAltaf Ur RahmanОценок пока нет

- Punishment and Criminal Intent ExplainedДокумент39 страницPunishment and Criminal Intent ExplainedsedditОценок пока нет

- Criminal Law Life SaverДокумент14 страницCriminal Law Life SaverHadi Onimisi TijaniОценок пока нет

- First Year Criminal Law OutlineДокумент21 страницаFirst Year Criminal Law OutlinebnovreskeОценок пока нет

- Contracts Big Picture OverviewДокумент1 страницаContracts Big Picture Overviewmelovebeingme100% (1)

- Criminal Homicide Chart!Документ1 страницаCriminal Homicide Chart!Paul UlitskyОценок пока нет

- Contracts I OutlineДокумент118 страницContracts I Outlinemjwyatt01Оценок пока нет

- Torts Bible FullДокумент150 страницTorts Bible FullLaura100% (1)

- Criminal Law OutlineДокумент76 страницCriminal Law OutlineYin Huang / 黄寅100% (6)

- Topic 6 Psychiatric Injury: Question and Answer Zone B 2019Документ2 страницыTopic 6 Psychiatric Injury: Question and Answer Zone B 2019Ancellina Chin100% (1)

- LSE Key Concepts: Criminal Law W I C B ? M R - I: Martin v. State VariationsДокумент7 страницLSE Key Concepts: Criminal Law W I C B ? M R - I: Martin v. State VariationsLeisa R RockeleinОценок пока нет

- Substantive Protection of Economic InterestsДокумент16 страницSubstantive Protection of Economic InterestsPaulPits100% (1)

- Tort Lecture Notes AllДокумент31 страницаTort Lecture Notes AllRossz FiúОценок пока нет

- Service of Process ChartДокумент1 страницаService of Process ChartRonnie Barcena Jr.100% (1)

- Montana Constitutional Pledge SignatoriesДокумент9 страницMontana Constitutional Pledge SignatoriesMTDemocratsОценок пока нет

- Torts OutlineДокумент43 страницыTorts OutlineCaitlin ForsythОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Law CasesДокумент147 страницConstitutional Law Casesvanessa. velascoОценок пока нет

- Acts and OmissionsДокумент5 страницActs and OmissionsIvan LeeОценок пока нет

- Crim Fall 2011 ChecklistДокумент2 страницыCrim Fall 2011 ChecklistAlex LuriaОценок пока нет

- EVIDENCE OF CHARACTERДокумент21 страницаEVIDENCE OF CHARACTEReve tichaОценок пока нет

- Family Law NotesДокумент3 страницыFamily Law NotesAndre AndersonОценок пока нет

- Civ Pro OutlineДокумент48 страницCiv Pro OutlineTR1912Оценок пока нет

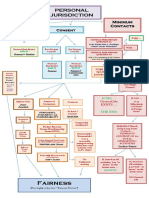

- PJ Flow ChartДокумент1 страницаPJ Flow ChartMalik DeanОценок пока нет

- Arrest and Detention FlowchartДокумент1 страницаArrest and Detention FlowchartAliОценок пока нет

- Historical Development of International LawДокумент175 страницHistorical Development of International LawAmitabh AbhijitОценок пока нет

- Admissible:Inadmissible Character EvidenceДокумент7 страницAdmissible:Inadmissible Character Evidencemdean10Оценок пока нет

- Property Attack OutlineДокумент9 страницProperty Attack OutlineAshley MeredithОценок пока нет

- Business Associations I - Preliminary VersionДокумент10 страницBusiness Associations I - Preliminary Versionlogan doopОценок пока нет

- Case Summary of Marbury V MadisonДокумент2 страницыCase Summary of Marbury V MadisonGilly Mae Gallego RPhОценок пока нет

- IRAC EditedДокумент5 страницIRAC EditedMORRIS ANUNDAОценок пока нет

- Contracts Law School Answer GuideДокумент10 страницContracts Law School Answer GuideRonald Alexander100% (1)

- Constitutional Law OutlineДокумент19 страницConstitutional Law OutlineThomas Jefferson100% (1)

- Domestic Relations OutlineДокумент13 страницDomestic Relations Outlinedcwashin100% (1)

- CONTRACTS EXAM WRITING FORMULAДокумент6 страницCONTRACTS EXAM WRITING FORMULAsratzkinОценок пока нет

- Principles of criminal liability explainedДокумент19 страницPrinciples of criminal liability explainedWAWOTOBIОценок пока нет

- Contracts Outline. Bender. Spring 2013Документ158 страницContracts Outline. Bender. Spring 2013Laura CОценок пока нет

- Pawnbroker Waives Right to Demand by Claiming TitleДокумент153 страницыPawnbroker Waives Right to Demand by Claiming TitleAaron WarnerОценок пока нет

- Crim OutlineДокумент4 страницыCrim OutlineAaron FlemingОценок пока нет

- Intentional Tort Law OutlineДокумент52 страницыIntentional Tort Law OutlinemitchturbОценок пока нет

- Property II OutlineДокумент15 страницProperty II OutlineAshley DanielleОценок пока нет

- 2023-08-10 COM Motion For Permission To Seek Interlocutory Appeal and Stay of Proceedings - 4859-6556-9142 - 4Документ9 страниц2023-08-10 COM Motion For Permission To Seek Interlocutory Appeal and Stay of Proceedings - 4859-6556-9142 - 4Jacob GallantОценок пока нет

- Outline Laura Civil Procedure.Документ97 страницOutline Laura Civil Procedure.Mike Binka KusiОценок пока нет

- Criminal Law: Chapter 4 in Your TextbookДокумент22 страницыCriminal Law: Chapter 4 in Your TextbookPunam ChauhanОценок пока нет

- Contract Law Answer GuideДокумент5 страницContract Law Answer GuideAdrienne Ho100% (1)

- Criminal LawДокумент7 страницCriminal Lawterracotta2014Оценок пока нет

- Criminal Law - Fairfax - Common Law Attack Sheet - 3Документ10 страницCriminal Law - Fairfax - Common Law Attack Sheet - 3champion_egy325Оценок пока нет

- Civil Procedure OutlineДокумент10 страницCivil Procedure OutlineMeenaОценок пока нет

- 05 Miranda WarningДокумент12 страниц05 Miranda WarningEden Escalo100% (1)

- # 13 Criminal Damage PDFДокумент8 страниц# 13 Criminal Damage PDFDinesh Kannen KandiahОценок пока нет

- LAW 531 Week 2 Team B-IRAC Brief-Tort CaseДокумент6 страницLAW 531 Week 2 Team B-IRAC Brief-Tort Casebrian100% (1)

- Francisco M. Lecaroz and Lenlie Lecaroz, Petitioners, vs. Sandiganbayan and PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, RespondentsДокумент7 страницFrancisco M. Lecaroz and Lenlie Lecaroz, Petitioners, vs. Sandiganbayan and PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, RespondentsEisley SarzadillaОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 151258Документ82 страницыG.R. No. 151258Jai MendozaОценок пока нет

- Criminal Law, Jurisprudence and ProcedureДокумент25 страницCriminal Law, Jurisprudence and ProcedureBappyОценок пока нет

- Criminal Liability FactorsДокумент13 страницCriminal Liability FactorsJayzyl PongautanОценок пока нет

- Ambush Leaves Two Dead, One InjuredДокумент3 страницыAmbush Leaves Two Dead, One InjuredVida MarieОценок пока нет

- U.S. v. YunisДокумент11 страницU.S. v. YunisBaekhyun To ChanyeolОценок пока нет

- Understanding Torts: Legal Text SeriesДокумент34 страницыUnderstanding Torts: Legal Text SeriesRamVasiОценок пока нет

- Chapter - 2: Bishop, Criminal Law, 9 Edition, 1923, P. 287Документ51 страницаChapter - 2: Bishop, Criminal Law, 9 Edition, 1923, P. 287akira menonОценок пока нет

- Criminal Law Chart MosesДокумент27 страницCriminal Law Chart Mosespromogoat50% (4)

- Penalties for Frustrated and Attempted Parricide, Murder or HomicideДокумент12 страницPenalties for Frustrated and Attempted Parricide, Murder or HomicidekdescallarОценок пока нет

- 2016 Pre-Week Notes On CRIMINAL LAW 1Документ23 страницы2016 Pre-Week Notes On CRIMINAL LAW 1John Dx LapidОценок пока нет

- Supreme Court upholds child abuse convictionДокумент11 страницSupreme Court upholds child abuse convictionGendale Am-isОценок пока нет

- Clu3m - Elements of A CrimeДокумент2 страницыClu3m - Elements of A Crimeapi-334810559Оценок пока нет

- General Conditions of Tortious LiabilityДокумент15 страницGeneral Conditions of Tortious Liability2230003Оценок пока нет

- Jugement Pravind JugnauthДокумент21 страницаJugement Pravind JugnauthL'express MauriceОценок пока нет

- Charles Shateek SMITH v. Benjamin L. KELLY (SPD Officer) - Opinion and OrderДокумент33 страницыCharles Shateek SMITH v. Benjamin L. KELLY (SPD Officer) - Opinion and OrdermovingtocanadaОценок пока нет

- Week 4 - Legal EnglishДокумент4 страницыWeek 4 - Legal EnglishIrina StoicaОценок пока нет

- Application of PenaltiesДокумент9 страницApplication of Penaltiesrascille laranasОценок пока нет

- 02 Daracan V Natividad (341 Scra 161)Документ7 страниц02 Daracan V Natividad (341 Scra 161)earl0917Оценок пока нет

- United States v. David Manley and Fluer Williams, 632 F.2d 978, 2d Cir. (1980)Документ16 страницUnited States v. David Manley and Fluer Williams, 632 F.2d 978, 2d Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- 06 JGPS Bar Notes - Criminal LawДокумент37 страниц06 JGPS Bar Notes - Criminal LawJoseph SantosОценок пока нет

- People vs. Oanis and GalantaДокумент15 страницPeople vs. Oanis and GalantaDon MaximoОценок пока нет

- People vs. Bernardino GaffudДокумент4 страницыPeople vs. Bernardino GaffudmonjekatreenaОценок пока нет

- Double Jeopardy Case DigestДокумент61 страницаDouble Jeopardy Case DigestMark Ebenezer BernardoОценок пока нет

- United States v. Baycon Industries, Inc. and William R. Chittenden, JR., 744 F.2d 1505, 11th Cir. (1984)Документ6 страницUnited States v. Baycon Industries, Inc. and William R. Chittenden, JR., 744 F.2d 1505, 11th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- 2015 Bar Reviewer on Criminal Law PrinciplesДокумент89 страниц2015 Bar Reviewer on Criminal Law PrinciplesKarrenMaeObeso100% (6)

- 2014 Criminal Law Review PDFДокумент80 страниц2014 Criminal Law Review PDFcathy1808100% (3)

- Accounts Scott LymanДокумент18 страницAccounts Scott LymanNadya BobovaОценок пока нет

- Unit IVДокумент22 страницыUnit IVchinmay behareОценок пока нет

- Case No. 3 JOHN PHILIP GUEVARRA vs. HONORABLE IGNACIO ALMODOVARДокумент2 страницыCase No. 3 JOHN PHILIP GUEVARRA vs. HONORABLE IGNACIO ALMODOVARCarmel Grace Kiwas100% (1)

- Perversion of Justice: The Jeffrey Epstein StoryОт EverandPerversion of Justice: The Jeffrey Epstein StoryРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (10)

- The Trigger: Narratives of the American ShooterОт EverandThe Trigger: Narratives of the American ShooterРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (70)

- Reasonable Doubts: The O.J. Simpson Case and the Criminal Justice SystemОт EverandReasonable Doubts: The O.J. Simpson Case and the Criminal Justice SystemРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (25)

- Enough: The Violence Against Women and How to End ItОт EverandEnough: The Violence Against Women and How to End ItРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5)

- What's Prison For?: Punishment and Rehabilitation in the Age of Mass IncarcerationОт EverandWhat's Prison For?: Punishment and Rehabilitation in the Age of Mass IncarcerationОценок пока нет

- O.J. Is Innocent and I Can Prove It: The Shocking Truth about the Murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron GoldmanОт EverandO.J. Is Innocent and I Can Prove It: The Shocking Truth about the Murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron GoldmanРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (2)

- For the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder That Shocked Jazz Age ChicagoОт EverandFor the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder That Shocked Jazz Age ChicagoРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (97)

- Hunting Whitey: The Inside Story of the Capture & Killing of America's Most Wanted Crime BossОт EverandHunting Whitey: The Inside Story of the Capture & Killing of America's Most Wanted Crime BossРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (6)

- Prison by Any Other Name: The Harmful Consequences of Popular ReformsОт EverandPrison by Any Other Name: The Harmful Consequences of Popular ReformsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (11)

- The Killer Across the Table: Unlocking the Secrets of Serial Killers and Predators with the FBI's Original MindhunterОт EverandThe Killer Across the Table: Unlocking the Secrets of Serial Killers and Predators with the FBI's Original MindhunterРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (456)

- Conviction: The Untold Story of Putting Jodi Arias Behind BarsОт EverandConviction: The Untold Story of Putting Jodi Arias Behind BarsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (16)

- The Edge of Innocence: The Trial of Casper BennettОт EverandThe Edge of Innocence: The Trial of Casper BennettРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (3)

- You Might Go to Prison, Even Though You're InnocentОт EverandYou Might Go to Prison, Even Though You're InnocentРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Who Really Killed Nicole?: O. J. Simpson's Closest Confidant Tells AllОт EverandWho Really Killed Nicole?: O. J. Simpson's Closest Confidant Tells AllРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (1)

- Just Mercy: a story of justice and redemptionОт EverandJust Mercy: a story of justice and redemptionРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (175)

- The Court of Last Resort: The True Story of a Team of Crime Experts Who Fought to Save the Wrongfully ConvictedОт EverandThe Court of Last Resort: The True Story of a Team of Crime Experts Who Fought to Save the Wrongfully ConvictedРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (8)

- Sex Trafficking: Inside the Business of Modern SlaveryОт EverandSex Trafficking: Inside the Business of Modern SlaveryРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (16)

- No Matter How Loud I Shout: A Year in the Life of Juvenile CourtОт EverandNo Matter How Loud I Shout: A Year in the Life of Juvenile CourtРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Family Secrets: The Case That Crippled the Chicago MobОт EverandFamily Secrets: The Case That Crippled the Chicago MobРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (19)

- The Killer Across the Table: Unlocking the Secrets of Serial Killers and Predators with the FBI's Original MindhunterОт EverandThe Killer Across the Table: Unlocking the Secrets of Serial Killers and Predators with the FBI's Original MindhunterРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (112)

- The Death of Punishment: Searching for Justice among the Worst of the WorstОт EverandThe Death of Punishment: Searching for Justice among the Worst of the WorstОценок пока нет

- American Injustice: Inside Stories from the Underbelly of the Criminal Justice SystemОт EverandAmerican Injustice: Inside Stories from the Underbelly of the Criminal Justice SystemРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (5)

- Three Felonies A Day: How the Feds Target the InnocentОт EverandThree Felonies A Day: How the Feds Target the InnocentРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (25)