Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

DG Rinosinus

Загружено:

pisucamiОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

DG Rinosinus

Загружено:

pisucamiАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CHEST Original Research

ASTHMA

Criteria To Screen for Chronic

Sinonasal Disease

Anne E. Dixon, MD, FCCP; Elizabeth A. Sugar, PhD; S. James Zinreich, MD;

Raymond G. Slavin, MD; Jonathan Corren, MD; Robert M. Naclerio, MD;

Masaru Ishii, MD, PhD; Rubin I. Cohen, MD, FCCP; Ellen D. Brown, MS;

Robert A. Wise, MD, FCCP; and Charles G. Irvin, PhD; for the American Lung

Association-Asthma Clinical Research Centers*

Background: Sinusitis and rhinitis are associated with uncontrolled asthma. There are no simple,

validated tools to screen for these diseases. The objective of this study was to assess instruments

to assist in the diagnosis of chronic sinonasal disease.

Methods: Participants without acute sinonasal symptoms underwent an extensive evaluation. The

results were submitted to an expert panel that used the Delphi method to achieve consensus.

Using the consensus diagnosis of the panel, we determined the sensitivity and specificity of test

procedures to diagnose chronic sinonasal disease. We determined the reproducibility of the most

sensitive and specific instrument in a separate cohort.

Results: Fifty-nine participants were evaluated, and the expert panel reached consensus for all (42

participants with chronic sinonasal disease, 17 participants without chronic sinonasal disease). A

six-item questionnaire based on the frequency of nasal symptoms was the most sensitive tool used to

diagnose sinonasal disease (minimum specificity, 0.90). Reproducibility testing in a separate cohort of

63 participants (41 chronic sinonasal disease with asthma, 22 chronic sinonasal disease without

asthma) showed a concordance correlation coefficient of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.85 to 0.94) when this

questionnaire was limited to five items (ie, excluding a question on smell). This five-item question-

naire had a sensitivity of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.77 to 0.97), a specificity of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.71 to 1.00), and

an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.97 (95% CI, 0.93 to 1.0). Sinus CT scans

and nasal endoscopy lacked sensitivity for use in the diagnosis of chronic sinonasal disease.

Conclusions: We have developed a sensitive, specific, and reproducible instrument to screen for

chronic sinonasal disease. Validation studies of this five-item questionnaire are needed, including in

patients with asthma. (CHEST 2009; 136:1324 –1332)

Abbreviations: AUC ⫽ area under the curve; ROC ⫽ receiver operating characteristic; SNQ ⫽ sinonasal questionnaire

R with

hinitis and sinusitis are very common in patients

asthma. Sinonasal disease may lead to

1,2

in the diagnosis of chronic sinonasal disease. Given the

overlap between rhinitis and sinusitis, we did not

poorly controlled asthma, so guidelines3 have recom- attempt to distinguish between the two disease entities.

mended screening for rhinitis and sinusitis, but there is We evaluated a cohort of participants with a standard-

no consensus on how this should be done. Although ized set of clinical, laboratory, and imaging procedures.

some investigators have suggested using sophisticated We excluded acute disease. The data from this evalu-

testing such as CT imaging or endoscopy, these tests ation were submitted to an expert panel that deter-

are expensive and inconvenient. In practice, physicians mined whether the participants had chronic rhinitis or

often make diagnoses and treat patients on the basis of sinusitis. Using the diagnoses of the panel, we deter-

vague clinical criteria, and only when patients do not mined the sensitivity and specificity of individual clin-

respond to therapy or have symptoms suggesting com- ical instruments to distinguish patients with chronic

plicated disease are CT scans or endoscopy used. rhinitis or sinusitis from those without. We determined

The purpose of this study was to determine the most the repeatability of the most sensitive and specific

sensitive, specific, and reproducible instrument for use instrument, a questionnaire, in a separate cohort.

1324 Original Research

Materials and Methods Phase 2: Reproducibility Testing

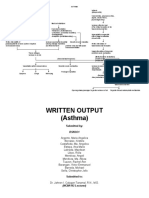

An overview of both phases of the study method is presented Based on previous reports in the literature,6,7 we identified 6

in Figure 1 and discussed herein. questions from the original total of 13 questions that were related

to the frequency of specific symptoms, and that we hypothesized

would be both sensitive and specific for identifying patients with

Phase 1 sinonasal disease. We tested the performance characteristics of

these items and compared them with other standard question-

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all six naires and specific testing procedures.

participating American Lung Association-Asthma Clinical Research Results from phase 1 of the study showed that this six-item

Centers, and informed consent was obtained from all phase 1 questionnaire was the tool with the highest sensitivity and

participants. From the centers, we enrolled participants with and specificity for use in diagnosing chronic sinonasal disease. To

without asthma who were ⱖ 18 years of age. Participants were determine the reproducibility of these items, participants in

recruited from local clinics and through advertising. We recruited phase 2 of the study completed the questionnaire on two

persons without asthma to ensure the inclusion of participants occasions at least 1 week apart.

without chronic rhinitis and sinusitis for sensitivity and specificity The second cohort of participants was recruited outside of allergy

calculations. Details of the eligibility criteria are included in the season in Vermont from a pulmonary clinic and local college

online supplement. Recruitment took place out of allergy season campuses. We included participants ⱖ 18 years of age with and

between November 2006 and March 2007 at each individual center. without a self-report of asthma. We excluded participants who had

Spirometry and methacholine challenge testing were performed reported upper airway symptoms only in the past 6 weeks, had a

according to American Thoracic Society4,5 guidelines. Participants ⬎ 10 pack-year smoking history, or had smoked in the past 6

answered questionnaires6 –13 and underwent nasal endoscopy and months.

sinus CT scanning14 (details in the online supplement).

We submitted a standardized data set on each participant to an

expert panel who had determined its contents at the beginning of Statistical Analysis

the study. The data set included multiple questions pertaining to

specific sinonasal symptoms (13 total, shown in the online supple- For phase 1, descriptive statistics (mean, SD, count, and propor-

ment) that have been reported in the literature,6,7 were believed to tion) were used to summarize baseline demographics. The popula-

be relevant by the expert panel, and would be useful and relevant in tion was divided into the following two groups: participants with

a clinical setting. In addition to the answers to these questions, the asthma; and participants without asthma. The number of partici-

data set included the results of a previously published sinus symp- pants identified as either having or not having chronic sinonasal

tom scale score,10 and the endoscopy and CT scanning. disease was tabulated for each group. The agreement between the

The expert panel determined whether each participant had first and last diagnosis rounds was calculated for each panel member

sinusitis, rhinitis, unknown disease, or no disease. We used the using a statistic with a 95% CI. We compared continuous

Delphi method15 to reach consensus among panelists, who had no measurements of lung function (eg, symptom scores and pulmonary

direct contact with one another. When disagreement existed be- function) among participants with and without a condition using the

tween panelists, the data coordinating center returned the data set Wilcoxon rank sum test because not all of the measurements

(with the anonymous results of the first round) to the panel for a followed a Gaussian distribution. Sinonasal symptom scoring mea-

second and third round, and the panelists were again asked to surements with p ⬍ 0.05 in the association analysis were considered

classify the participant until they reached consensus on a diagnosis. in the classification analysis described later in this article. Classifica-

The panel consisted of two otolaryngologists and one allergy- tion techniques (receiver operating characteristic [ROC], area under

immunologist, all of whom were experts in the field of sinonasal the curve [AUC], sensitivity, and specificity) were used to identify

disease. clinical tools with potential use in reliably diagnosing chronic

sinonasal disease in the overall population. For each of the measure-

ments of upper airways disease, a ROC curve was constructed. The

Manuscript received August 13, 2008; revision accepted May 5,

2009. empirical AUC was calculated with a 95% bootstrap CI.16 The goal

Affiliations: From the Department of Medicine (Drs. Dixon and was to obtain a high level of specificity while maintaining an

Irvin), University of Vermont, Burlington, VT; Johns Hopkins acceptable level of sensitivity. Therefore, for each measurement, the

University (Drs. Sugar, Zinreich, Ishii, and Wise, and Ms. cutoff point was selected in order to maximize sensitivity while

Brown), Baltimore, MD; Saint Louis University (Dr. Slavin), St. requiring that the specificity be ⱖ 0.90. The sensitivity and specific-

Louis, MO; University of California Los Angeles (Dr. Corren), ity with 95% CIs were calculated for each measurement based on

Los Angeles, CA; the Department of Surgery (Dr. Naclerio), these cutoff points.

University of Chicago, Chicago, IL; and the Department of For phase 2, the reproducibility of the questionnaire, both with

Pulmonary and Sleep Medicine (Dr. Cohen), North Shore-Long (six items) and without a question pertaining to smell (five items),

Island Jewish Medical Center, New Hyde Park, NY.

*A complete list of participants is located in the Appendix. was evaluated in a separate cohort made up of both participants

The preliminary results of phase 1 of this study were presented at with asthma and participants without asthma. Summary statistics

the meeting of the American Thoracic Society in San Francisco, (mean [SD]) were used to describe each visit as well as the

May 20, 2007. change between visits. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the American determine whether a significant difference existed in the scores

Lung Association, National Institutes of Health grant RR019965, between the two visits. Pearson correlation coefficients and the

and an unrestricted grant from Schering-Plough. concordance correlation coefficients17 were calculated in order to

Correspondence to: Anne E. Dixon, MD, FCCP, University of assess the amount of variability between time points relative to

Vermont, Medicine, Patrick 204, 111 Colchester Ave, Burlington, the overall variability. The percentage of the times that the

VT 05401; e-mail: anne.dixon@uvm.edu

© 2009 American College of Chest Physicians. Reproduction classification changed based on the optimal cutpoints was calcu-

of this article is prohibited without written permission from the lated, and comparisons between the two versions of the ques-

American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestjournal.org/site/ tionnaire were made using the McNemar test. We repeated the

misc/reprints.xhtml). classification analysis for the five-item questionnaire. All analyses

DOI: 10.1378/chest.08-1983 were performed using a commercial statistical software package

www.chestjournal.org CHEST / 136 / 5 / NOVEMBER, 2009 1325

61 participants without symptoms of acute rhinitis/sinusitis

o 42 asthmatics

o 19 non-asthmatics

Evaluation of sinonasal disease

• Symptom questionnaires

• Nasal Endoscopic Examination

• Sinus CT (submitted to central reader)

One participant excluded, history of sinus surgery

Phase 1 Data submitted to Expert Panel (n = 60)

Instrument

Development Delphi Method to achieve consensus diagnosis

One participant excluded, panel agreed they were unable to

assign diagnosis

Predictive modeling to determine sensitivity and

specificity of clinical instruments to diagnose

chronic rhinitis and sinusitis

(n = 59)

Repeatability determination in separate cohort

• 41 asthmatics

Phase 2 • 22 non-asthmatics

Reproducibility

Testing

Predictive modeling to determine sensitivity and

specificity of questionnaire

Figure 1. Overview of study protocol.

(STATA 9; StataCorp; College Station, TX) and open-source could not make a definitive diagnosis from the

software (environment R; www.r-project.org). analysis. The final cohort comprised 41 participants

with asthma and 18 participants without asthma in

the final analysis (Table 1).

Results

We submitted a standardized set of data to the expert

Phase 1 panel three times. Table 2 summarizes the level of

Sixty-one participants were enrolled in phase 1 of agreement from each round. The statistics for each

the study. We excluded one participant who had reviewer between the first and the final diagnosis for all

previously undergone sinus surgery, and another three reviewers were 0.85 (95% CI, 0.73 to 0.96), 0.61

participant for whom the consensus panel believed it (95% CI, 0.46 to 0.76), and 0.61 (95% CI, 0.46 to 0.76).

1326 Original Research

Table 1—Baseline Characteristics of Phase 1 Study have chronic sinonasal disease compared with 6 of

Participants the 18 participants without asthma (33%; 95% CI,

With Asthma Without Asthma 13% to 59%). Participants with chronic sinonasal

Characteristics (n ⫽ 41) (n ⫽ 18) disease had significantly higher scores on all mea-

Age at enrollment, yr* 38.3 (15.9) 32.2 (13.0) sures of symptoms and imaging and more impaired

Male gender† 12 (29.3) 4 (22.2) quality of life (Table 3).

Race or ethnic group† We analyzed the sensitivity, specificity, and ROC

White 29 (70.7) 16 (88.9) curve for measures of sinonasal disease in partici-

Black 8 (19.5) 2 (11.1)

pants with and without asthma (Table 4, Fig 2).

Hispanic 3 (7.3) 0

Other 1 (2.4) 0 Initially, we found that the combination of the six

Lung function questions we had identified based on the frequency

Pre-bronchodilator 79.2 (19.9) 100.2 (10.3) of nasal symptoms was a sensitive and specific

therapy FEV1, % measure for use in diagnosing upper airways disease.

predicted

Furthermore, we tested the impact of adding

FEV1/FVC ratio 0.7 (0.1) 0.8 (0.1)

Baseline Juniper 2.04 (0.49) NA additional frequency questions on sensitivity,

asthma control specificity, and ROC for diagnosing sinonasal dis-

score ease and found no significant difference with the

Other conditions (self- addition of any further questions to the six-item

reported)†‡

(or five-item) questionnaire.

Eczema 7 (17.1) 1 (5.6)

Allergic rhinitis 29 (70.7) 0 Nasal endoscopy and CT scanning lacked sensitiv-

Food allergies 7 (17.1) 0 ity, given the specificity constraint. For diagnosing

Gastroesophageal 14 (34.1) 0 sinusitis alone (present in 13 participants), sinus CT

reflux disease scanning, using a score of 4.0, had the highest

NA ⫽ not applicable. sensitivity (83.3; 95% CI, 51.6 to 97.8) and specificity

*Values are given as the mean (SD). (93.5; 95% CI, 82.1 to 98.6).

†Values are given as No. (%).

‡Participants were asked whether they had these conditions “now or

within the past year.” Phase 2

We administered the six questions to a different

cohort of 64 participants to determine reproducibil-

If sinusitis and rhinitis are considered as a single ity. One participant was excluded because informa-

category (sinonasal disease), the statistics were 1 tion on the sense of smell was missing. Of the

(95% CI, 1 to 1), 0.84 (95% CI, 0.69 to 0.99), and 0.70 remaining 63 participants, 41 self-reported having

(95% CI, 0.49 to 0.91), which correspond to 0 (0%), 4 asthma, and 22 did not. Table 5 summarizes the

(7%), and 7 (11%) changes in diagnosis, respectively. behavior of the six-item and five-item questionnaires

Of the participants with asthma, 36 of 42 partici- at two time points. For both questionnaires, the

pants (87%; 95% CI, 71% to 95%) were deemed to score differed significantly (p ⫽ 0.0002 vs p ⫽

0.0018, respectively); however, there were only three

changes (4.76%) in the diagnosis of sinonasal disease

Table 2—A Summary of the Delphi Process for for the five-item questionnaire, but 13 changes

Phase 1 (20.63%) for the six-item questionnaire. The five-

item questionnaire had a significantly lower number

Agreement* Round 1 Round 2 Round 3

of changes in diagnosis (p ⫽ 0.0094). The concor-

3/3 36 14 3 dance correlation coefficient improved from 0.71 to

2/3 20 7 5 0.91 when the question pertaining to smell was

No agreement 3 1 1†

eliminated. We termed this five-item questionnaire

Missing‡ 0 1 0

the sinonasal questionnaire (SNQ) [Fig 3].

The table shows agreement of the panel through three rounds of data

The optimal cutpoint for the SNQ based on the

submission on 59 participants. The panelists agreed that their final

diagnosis on one participant was “unsure,” and this participant is not frequency of symptoms of nasal obstruction was 1,

included in this table and excluded from further analysis. which is equivalent to symptoms occurring, on aver-

*Number of panelists who agreed. age, one to four times per month. Participants with

†One panelist voted for rhinitis, one for sinusitis, and one for unsure. symptoms one or more times per month are classi-

The individual participant was classified for analysis as having

fied as abnormal. As the SNQ score increases, the

“sinusitis/rhinitis” because a majority of the panel agreed that

sinonasal disease was present. sensitivity decreases and specificity increases. Using

‡Missing refers to the fact that one of the expert panel diagnoses was a cutpoint of 1, the SNQ was highly sensitive (0.90;

missing for one participant during the second round. 95% CI, 0.77 to 0.97) [Table 4] and specific (0.94;

www.chestjournal.org CHEST / 136 / 5 / NOVEMBER, 2009 1327

Table 3—Nasal Symptoms and Findings in Participants With and Without Asthma With and Without Upper Airways

Disease

No Sinusitis or Rhinitis Sinusitis or Rhinitis

Mean Median (Range) Median (Range)

Measurements (SD) 关n ⫽ 17兴 Mean (SD) 关n ⫽ 42兴 p Value*

SSS† 5.18 (6.67) 1.00 (0.00–24.00 19.19 (13.42) 19.00 (0.00–57.00) 0.0001

RQLQ‡ 0.31 (0.52) 0.63 (0.00–1.60) 1.68 (0.94) 1.69 (0.00–3.68) ⬍ 0.0001

SNOT-20§ 0.36 (0.58) 0.10 (0.00–2.00) 1.48 (0.89) 1.55 (0.00–3.70) ⬍ 0.0001

Six-item questionnaire㛳 0.30 (0.30) 0.17 (0.00–0.83) 1.37 (0.54) 1.33 (0.33–2.67) ⬍ 0.0001

SNQ¶ 0.35 (0.34) 0.20 (0.00–1.00) 1.54 (0.54) 1.60 (0.40–2.60) ⬍ 0.0001

Sum of endoscopy scores# 1.29 (1.36) 1.00 (0.00–4.00) 2.98 (2.37) 3.00 (0.00–8.00) ⬍ 0.0001

Sinus CT score** 0.73 (1.16) 0.00 (0.00–4.00) 2.93 (3.38) 2.50 (0.00–19.00) 0.0023

RQLQ ⫽ Rhinitis Quality of Life Questionnaire; SNOT-20 ⫽ 20-item Sino-Nasal Outcomes Test; SSS ⫽ sinus symptom score.

*Calculated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

†The SSS scale is 0 to 60, where a higher score indicates more severe symptoms.10,11

‡The RQLQ scale is 0 to 6, where a higher score indicates more severe impairment.12 The value shown for RQLQ is without activities (n ⫽ 56).

§The SNOT-20 scale is 0 to 5, where a higher score indicates more severe impairment.13 One participant with asthma was missing data for this

instrument (n ⫽ 58).

㛳The six-item questionnaire scale is 0 to 3, where a higher score indicates more frequent symptoms.

¶The SNQ scale is 0 to 3, where a higher score indicates more frequent symptoms.

#The endoscopy scale is 0 to 20, where a higher score indicates more extensive disease.

**The sinus CT scale is 0 to 30, where a higher score indicates more severe disease. Fifty-eight participants had sinus CT scores, and one

participant without disease was missing a sphenoid reading; thus, the total sinus CT score is generated by calculating the sum of the area scores.

95% CI, 0.71 to 1.00) [Table 4] for distinguishing Chronic rhinitis and sinusitis are part of a disease

between the presence and absence of upper airways spectrum in which chronic inflammation leads to leu-

disease, with the ROC (Fig 2) having an AUC of kocyte infiltration, edema, and remodeling in the con-

0.97. Among participants with asthma only, the tiguous nasal and sinus mucosa. Therefore, we included

sensitivity and specificity were 0.94 (95% CI, 0.81 to both chronic rhinitis and sinusitis together because the

1.00) and 1.00 (95% CI, 0.47 to 1.00), respectively. two disease processes represent a continuum. This

continuum may explain why the expert panel members

disagreed on the specific diagnosis of rhinitis and

Discussion sinusitis in some participants. We refer to the disease

We have identified a sensitive, specific question- continuum as sinonasal disease because the related

naire to screen for chronic rhinitis and sinusitis. We term rhinosinusitis usually is reserved for patients who

focused on chronic sinonasal disease because pa- have sinusitis accompanied by rhinitis.18,19

tients typically seek treatment for acute symptoms Rhinitis is reported in up to 25% of the general

but may ignore more chronic symptoms. We have population, but afflicts up to 90% of patients with

shown that the diagnostic information from this asthma.2,20,21 Sinusitis is reported in 30% to 40% of

questionnaire is highly reproducible. The initial di- patients with asthma.2,22,23 The prevalence reported

agnosis of chronic sinonasal disease can be made varies across studies1 because validated methods rarely

without resorting to more expensive, inconvenient are used to make the diagnosis, particularly in cases of

testing. rhinitis.

Table 4 —Sample Size, Optimal Cutpoints, Sensitivity, and Specificity for the Seven Measurements

Measurements Participants, No. Optimal Cutpoint* Sensitivity, % (Range) Specificity, % (Range)

SSS 59 14.00 69.05 (52.91–82.38) 94.12 (71.31–99.85)

RQLQ 56 1.56 64.29 (48.02–78.45) 94.12 (71.31–99.85)

SNOT-20 58 1.55 52.38 (36.41–68.00) 94.12 (71.31–99.85)

Six-item questionnaire 59 1.00 80.95 (65.88–91.40) 100.00 (80.49–100.00)

SNQ 59 1.00 90.48 (77.37–97.34) 94.12 (71.31–99.85)

Sum of endoscopy scores 59 5.00 26.19 (13.86–42.04) 100.00 (80.49–100.00)

Sinus CT score 56 3.00 50.00 (34.19–65.81) 93.75 (69.76–99.84)

See Table 3 for abbreviations not used in the text.

*The optimal cutpoint is the value that maximizes the sensitivity of the measurement while achieving at least 90% specificity.

1328 Original Research

Figure 2. ROC, including the AUC, with a bootstrap estimate of the 95% CI. Value shown for RQLQ

is without activities, n ⫽ 56. Fifty-eight participants had sinus CT scores, and 1 participant without

asthma was missing a sphenoid reading. The total sinus CT score is generated by calculating the sum

of the area scores. See Table 3 for other abbreviations.

The “gold standard” in this study was the diagnosis we chose to incorporate symptoms, and CT scan and

rendered by an expert panel. Previous practice endoscopic findings into our evaluation, and to sub-

guidelines24 have recommended a symptom-based mit these findings to an expert panel. The clinical

diagnosis for rhinitis, though questions have not “gold standard” for diagnosing many disease pro-

been prospectively validated. Guidelines14 on the cesses often is contentious; so, for many disease

diagnosis of chronic sinusitis have recommended processes, the best “gold standard” available27,28

using symptom-based criteria, though many25 now represents a consensus opinion among experts.

recommend imaging. Imaging, either by CT scan- We used the Delphi method to achieve consensus

ning or endoscopy, are frequently used as “gold among panel members rather than a method involv-

standards,” though they give complementary infor- ing face-to-face meetings.29,30 With the Delphi

mation and are not always in agreement.6,26 Our method, information is submitted separately to each

questionnaire is unique in that we have chosen to panelist; there is no contact among members of the

diagnose chronic sinonasal disease rather than to panel. The panelists submit an opinion without any

focus specifically on rhinitis and sinusitis, as these discussion. In this study, each panelist communi-

diseases represent a continuum, particularly in pa- cated only with the data-coordinating center. The

tients with asthma. Because there is no “gold stan- advantage of the Delphi method is that one panelist

dard” for the diagnosis of chronic sinonasal disease, cannot exert undue influence on the group process,

www.chestjournal.org CHEST / 136 / 5 / NOVEMBER, 2009 1329

Table 5—Correlation of Questionnaires in nificantly improved by eliminating a question per-

Reproducibility Cohort (Phase 2) taining to smell, resulting in the SNQ. A cutpoint of

Six-Item 1 (experiencing each symptom an average of one to

Summary Statistics Questionnaire SNQ four times per month) was highly sensitive and

Visit 1 specific for diagnosing chronic sinonasal disease. In

Mean (SD) 1.33 (0.50) 1.18 (0.59) these circumstances, the SNQ was superior to en-

Median (range) 1.33 (0.16–2.33) 1.20 (0.00–2.40) doscopy and CT scan assessment using standard

Visit 2

scoring systems. Endoscopy and CT scans provide

Mean (SD) 1.16 (0.59) 1.28 (0.59)

Median (range) 1.17 (0.00–2.17) 1.40 (0.00–2.20) important anatomic data in patients with compli-

Difference cated sinus disease, especially those who require

Mean (SD) 0.16 (0.39) ⫺0.10 (0.24) surgery or a similar intervention, but are not neces-

Median (range) 0.17 (⫺0.83–1.17) 0.00 (⫺1.00–0.60) sary to make the initial diagnosis of chronic rhinitis

p Value* 0.0002 0.0018

and sinusitis in patients with asthma.

Concordance correlation 0.71 (0.56–0.81) 0.91 (0.84–0.94)

coefficient This tool was not developed to assess the response

(95% CI) to treatment, so it should not be used for that

Change in diagnosis, 13 (20.63) 3 (4.76) purpose. We did not collect information on educa-

No. (%)† tion status when we administered this questionnaire,

Total, n ⫽ 63. which may have implications for its use in certain

*Calculated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. populations. The SNQ was developed in a post hoc

†The SNQ has a significantly lower number of diagnosis changes

analysis and needs to be validated in a separate

based on the McNemar test (p ⫽ 0.0094).

cohort.

The SNQ represents an important new tool that

could be useful in the care of patients with asthma

but opinions may be altered based on the anonymous and for future research studies. It suggests that the

feedback from previous rounds of panel review. initial diagnosis of sinonasal disease can be made by

Thus, this method is effective in achieving a bal- a simple questionnaire rather than by sophisticated

anced consensus among all panelists. imaging studies. Further studies are required to

Our results show that the most sensitive method to validate this instrument in different populations, to

diagnose chronic rhinitis and sinusitis was a brief examine the individual components of the instru-

questionnaire using questions adapted from previ- ment, and to determine whether the treatment of

ously published studies.7–10 Separate reproducibility disease diagnosed through the use of this question-

testing showed that the questionnaire could be sig- naire is warranted.

Over the last 3 months how often, on average, did you have the following symptoms?

Never 1 - 4 times 2 - 6 times Daily

per month per week

Runny Nose

Post nasal drip

Need to blow your nose

Facial pain/pressure

Nasal obstruction

Scoring: Never (0), 1-4 times per month (1), 2- 6 times per week (2), and daily (3).

Score reported as average of 5 items: range of possible scores 0 - 3.

Figure 3. The SNQ.

1330 Original Research

Appendix: American Lung Association- speakers bureau for Schering-Plough, GSK, and AstraZeneca.

Asthma Clinical Research Centers Dr. Naclerio reports consultancy arrangements with GSK, Schering-

Plough, Merck, and Allux and grant support from GSK, Schering-

Plough, Merck, Novartis, and Capnia. Dr. Wise reports consul-

Clinical Research Sites tancies (including data safety monitoring boards) with GSK,

Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Lilly, Mann-

Nemours Children’s Clinic-University of Florida Consortium, kind, Medimmune, Intermune, Genentech, Emphasys, Spiration,

Jacksonville, FL; North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health Sys- Schering-Plough, and Otsuka and grant support from GSK,

tem, New Hyde Park, NY; University of Vermont, Colchester, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Forest, Schering-Plough, and Methap-

VT; University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL; harm. Dr. Irvin reports consultancy arrangements with Genetech

University of South Florida, Tampa, FL; and Washington Uni- and Methapharm; honoraria from Merck, Sepracor, and Medical

versity/St. Louis University, St. Louis, MO. Graphics; and grant support from Sepracor and GSK. Drs. Sugar,

Zinreich, and Ishii, and Ms. Brown have reported to the ACCP

Members of the Research Group that no significant conflicts of interest exist with any companies/

organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this

Nemours Children’s Clinic-University of Florida Consortium article.

(J. Lima [principal investigator], G. Josephson and D. Schaeffer Other contributions: The study group acknowledges the sup-

[coinvestigators], A. Santos [principal clinic coordinator], and L. port and wisdom of the late Dominic Iezzoni, MD.

Duckworth [coordinator]), Jacksonville, FL; North Shore-Long

Island Jewish Health System (R. Cohen [co-principal investiga-

tor], J. Karpel [co-principal investigator], and R. Ramdeo [prin-

cipal clinic coordinator]), New Hyde Park, NY; Vermont Lung References

Center at the University of Vermont (C. G. Irvin [principal 1 Togias A. Rhinitis and asthma: evidence for respiratory

investigator]; A. E. Dixon and D. A. Kaminsky [co-principal system integration. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 111:1171–

investigators]; S. M. Burns [principal clinic coordinator]; and 1183

L. M. Bourassa, S. E. Lang, and L. V. Griffes [coordinators]), 2 Dixon AE, Kaminsky DA, Holbrook JT, et al. Allergic rhinitis

Colchester, VT; University of Alabama at Birmingham (L. B. and sinusitis in asthma: differential effects on symptoms and

Gerald [principal investigator]; R. Grad [coinvestigator]; and S. pulmonary function. Chest 2006; 130:429 – 435

Erwin, D. Laken, and A. Lewis [coordinators]), Birmingham, AL; 3 Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention.

University of South Florida (R. Lockey [co-principal investiga- GINA report: 2008 update. Available at: www.ginasthma.org.

tor], S. Mohapatra [co-principal investigator], M. Grandstaff Accessed October 14, 2009

[principal clinic coordinator], and S. McCullough and B. Fimbel 4 American Thoracic Society. Standardization of spirometry:

[coordinators]), Tampa, FL; Washington University/St. Louis 1994 update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 152:1107–

University (M. Castro [co-principal investigator]; R. Slavin [co- 1136

principal investigator]; and M. E. Scheipeter, J. Tarsi, and D. 5 Crapo RO, Casaburi R, Coates AL, et al. Guidelines for

Keaney [coordinators]), St. Louis, MO; and the Data Coordinat- methacholine and exercise challenge testing-1999: official

ing Center (R. Wise [center director]; J. Holbrook [deputy statement of the American Thoracic Society adopted by the

director]; E. Brown [principal coordinator]; and C. Levine, ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care

J. Jones, R. Masih, S. Modak, D. Nowakowski, N. Prusakowski, Med 2000; 161:309 –329

D. Shade, and E. Sugar), Johns Hopkins University Center for 6 Raherison C, Montaudon M, Stoll D, et al. How should nasal

Clinical Trials, Baltimore, MD. symptoms be investigated in asthma? A comparison of radio-

logic and endoscopic findings. Allergy 2004; 59:821– 826

7 Bhattacharyya N. Clinical and symptom criteria for the

Acknowledgments accurate diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope

2006; 116:1–22

Author contributions: Drs. Dixon, Wise, and Irvin contributed 8 Bonfils P, Halimi P, Le Bihan C, et al. Correlation between

substantially to the conception, design, and acquisition of data; nasosinusal symptoms and topographic diagnosis in chronic

the analysis and interpretation of data; and the drafting of the rhinosinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2005; 114:74 – 83

submitted article. Dr. Dixon also vouches for the integrity of the 9 Bousquet J, Lund VJ, van Cauwenberge P, et al. Implemen-

data and accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Sugar contributed tation of guidelines for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a randomized

substantially to the analysis and interpretation of data. Dr. controlled trial. Allergy 2003; 58:733–741

Zinreich made important contributions to the analysis of the 10 Walker FD, White PS. Sinus symptom scores: what is the

radiologic studies. Dr. Slavin contributed substantially to the range in healthy individuals? Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci

conception, design, and acquisition of data. Dr. Corren contrib- 2000; 25:482– 484

uted substantially to the study design and served on the expert 11 Lund VJ, Holmstrom M, Scadding GK. Functional endo-

review panel. Drs. Naclerio and Ishii served on the expert review scopic sinus surgery in the management of chronic rhinosi-

panel. Dr. Cohen and Ms. Brown made substantial contributions nusitis: an objective assessment. J Laryngol Otol 1991; 105:

to the design and acquisition of data, and helped to draft the 832– 835

submitted article. All authors critically revised the article for 12 Juniper EF. Quality of life in adults and children with asthma

important intellectual content. and rhinitis. Allergy 1997; 52:971–977

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: Dr. Dixon reports a con- 13 Piccirillo JF, Merritt MG Jr, Richards ML. Psychometric and

sultancy arrangement with Merck and grant support from Schering- clinimetric validity of the 20-item Sino-Nasal Outcome Test

Plough. Dr. Slavin reports a consultancy arrangement with (SNOT-20). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002; 126:41– 47

Schering-Plough and grant support from Accentia and Schering- 14 Lund VJ, Kennedy DW. Quantification for staging sinusitis:

Plough. Dr. Corren reports consultancy arrangements with the Staging and Therapy Group. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol

Schering-Plough and GSK; receives grant support from Schering- 1995; 167(suppl):17–21

Plough, GSK, Amgen, Sepracor, and AstraZeneca; and is on the 15 Graham B, Regehr G, Wright JG. Delphi as a method to

www.chestjournal.org CHEST / 136 / 5 / NOVEMBER, 2009 1331

establish consensus for diagnostic criteria. J Clin Epidemiol 24 Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS, Bernstein DI, et al. The diagnosis

2003; 56:1150 –1156 and management of rhinitis: an updated practice parameter.

16 Efron B, Tibshirani R. An introduction to the bootstrap. New J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 122:S1–S84

York, NY: Chapman & Hall, 1993 25 Slavin RG, Spector SL, Bernstein IL, et al. The diagnosis

17 Lin LI. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate and management of sinusitis: a practice parameter update.

reproducibility. Biometrics 1989; 45:255–268 J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005; 116:S13–S47

18 Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL, Hadley JA, et al. Rhinosinusitis: 26 Stankiewicz JA, Chow JM. A diagnostic dilemma for chronic

establishing definitions for clinical research and patient care. rhinosinusitis: definition accuracy and validity. Am J Rhinol

J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 114:155–212 2002; 16:199 –202

19 Aukema AA, Fokkens WJ. Chronic rhinosinusitis: manage-

27 Nassef M, Shapiro G, Casale TB. Identifying and managing

ment for optimal outcomes. Treat Respir Med 2004; 3:97–105

rhinitis and its subtypes: allergic and nonallergic components:

20 Plaschke PP, Janson C, Norrman E, et al. Onset and remis-

a consensus report and materials from the Respiratory and

sion of allergic rhinitis and asthma and the relationship with

atopic sensitization and smoking. Am J Respir Crit Care Med Allergic Disease Foundation. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;

2000; 162:920 –924 22:2541–2548

21 Settipane RJ, Hagy GW, Settipane GA. Long-term risk 28 Flaherty KR, King TE Jr, Raghu G, et al. Idiopathic intersti-

factors for developing asthma and allergic rhinitis: a 23-year tial pneumonia: what is the effect of a multidisciplinary

follow-up study of college students. Allergy Proc 1994; 15: approach to diagnosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;

21–25 170:904 –910

22 Ferrante ME, Quatela MM, Corbo GM, et al. Prevalence of 29 Rosengart MR, Nathens AB, Schiff MA. The identification of

sinusitis in young asthmatics and its relation to bronchial criteria to evaluate prehospital trauma care using the Delphi

asthma. Mil Med 1998; 163:180 –183 technique. J Trauma 2007; 62:708 –713

23 ten Brinke A, Sterk PJ, Masclee AA, et al. Risk factors of 30 Fretheim A, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD. Improving the use

frequent exacerbations in difficult-to-treat asthma. Eur Re- of research evidence in guideline development: 5. Group

spir J 2005; 26:812– 818 processes. Health Res Policy Syst 2006; 4:17

1332 Original Research

Вам также может понравиться

- Clinical Guideline Diagnosing Syncope Part 1: Value of History, Physical Examination, and ElectrocardiographyДокумент8 страницClinical Guideline Diagnosing Syncope Part 1: Value of History, Physical Examination, and ElectrocardiographyPriya JainОценок пока нет

- Nihms 437493Документ15 страницNihms 437493dydy_7193Оценок пока нет

- QOLRes 2005 Sinusitis HRQLmeasureДокумент12 страницQOLRes 2005 Sinusitis HRQLmeasureArza WonkaОценок пока нет

- Sfar ScoreДокумент8 страницSfar ScoreprabuОценок пока нет

- Validation Study of The Sniffin' Sticks'' Olfactory Test in A British Population: A Preliminary CommunicationДокумент5 страницValidation Study of The Sniffin' Sticks'' Olfactory Test in A British Population: A Preliminary CommunicationCoryza Gabrie tanОценок пока нет

- Scoring System CopdДокумент9 страницScoring System CopdAnty FftОценок пока нет

- Trials With Combined/overall Symptom ScoresДокумент7 страницTrials With Combined/overall Symptom ScoresAr RoshyiidОценок пока нет

- Ajukan 2Документ12 страницAjukan 2Rifky TaniyoОценок пока нет

- Tos CronicaДокумент12 страницTos CronicasaloОценок пока нет

- (2009) Radiographic Improvement and Its Predictors in Patients With Pulmonary TuberculosisДокумент6 страниц(2009) Radiographic Improvement and Its Predictors in Patients With Pulmonary TuberculosisMohd RahimiОценок пока нет

- Summary of DNB ThesisДокумент3 страницыSummary of DNB Thesismugesh mc mugesh mcОценок пока нет

- Revista de PediatríaДокумент10 страницRevista de PediatríaAlinitha RobledoОценок пока нет

- JurnalДокумент7 страницJurnalDaniel BudiОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S0954611123003153 MainДокумент8 страниц1 s2.0 S0954611123003153 MainEducation serviceОценок пока нет

- The Clinical Spectrum of Henoch - Schönlein Purpura in Children: A Single-Center StudyДокумент8 страницThe Clinical Spectrum of Henoch - Schönlein Purpura in Children: A Single-Center StudyDaniela PetricanОценок пока нет

- Meta-Analysis: Psoriatic Arthritis Screening: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisДокумент16 страницMeta-Analysis: Psoriatic Arthritis Screening: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisireneardianiОценок пока нет

- RamachandranДокумент9 страницRamachandranjojobaggins100% (1)

- JurnalДокумент6 страницJurnalIzzyОценок пока нет

- Mortality in Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisДокумент9 страницMortality in Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysisesya putrri oktareginaОценок пока нет

- Karakteristik Pengetahuan Dan Persepsi Penderita Akne Vulgaris Di Kota MataramДокумент7 страницKarakteristik Pengetahuan Dan Persepsi Penderita Akne Vulgaris Di Kota MataramriniОценок пока нет

- Saltagi Et Al 2021 Diagnosis of Anosmia and Hyposmia A Systematic ReviewДокумент17 страницSaltagi Et Al 2021 Diagnosis of Anosmia and Hyposmia A Systematic ReviewmeiliafincyapОценок пока нет

- PAVM em Terapia IntensivaДокумент10 страницPAVM em Terapia IntensivaVictor Hugo SilveiraОценок пока нет

- As 2Документ11 страницAs 2Patrick SteinbergОценок пока нет

- Personality Traits AsthmaДокумент10 страницPersonality Traits AsthmaAnna DiaconuОценок пока нет

- NPE Lupus Early 2009Документ8 страницNPE Lupus Early 2009Maria GarabajiuОценок пока нет

- Cuff-Leak Test For Predicting Postextubation Airway Complications: A Systematic ReviewДокумент13 страницCuff-Leak Test For Predicting Postextubation Airway Complications: A Systematic ReviewMau MillanОценок пока нет

- Are The Acoustic Measurements Reliable in The Assessment ofДокумент13 страницAre The Acoustic Measurements Reliable in The Assessment ofIsabel Monteiro GomesОценок пока нет

- Pico P1Документ3 страницыPico P1Siti Ayu Nur'afifahОценок пока нет

- PSY53 PATIENT PREFERENCES IN THE TREATMENT OF HEMOPHILIA A - 2019 - Value in HДокумент1 страницаPSY53 PATIENT PREFERENCES IN THE TREATMENT OF HEMOPHILIA A - 2019 - Value in HMichael John AguilarОценок пока нет

- Diagnosis and Testing in Bronchiolitis: A Systematic ReviewДокумент8 страницDiagnosis and Testing in Bronchiolitis: A Systematic ReviewDaniel IrrazabalОценок пока нет

- Husein2019 - The 22-Item Sinonasal Outcome Test As A Tool For The Assessment of Quality of Life and Symptom Control in Allergic RhinitisДокумент8 страницHusein2019 - The 22-Item Sinonasal Outcome Test As A Tool For The Assessment of Quality of Life and Symptom Control in Allergic RhinitisDinОценок пока нет

- Nasolaryngoscopy in A Family Medicine Clinic: Indications, Findings, and EconomicsДокумент7 страницNasolaryngoscopy in A Family Medicine Clinic: Indications, Findings, and Economicsriski novitaОценок пока нет

- Noutati Din Diagnosticarea AstmuluiДокумент1 страницаNoutati Din Diagnosticarea AstmuluiPetrescu MihaiОценок пока нет

- Asthma Guidelines: An Assessment of Physician Understanding and PracticeДокумент7 страницAsthma Guidelines: An Assessment of Physician Understanding and PracticeFilip ThorntonОценок пока нет

- Validation of The Standardized Version of RQLQ Juniper1999Документ6 страницValidation of The Standardized Version of RQLQ Juniper1999IchsanОценок пока нет

- Impact of Self-Reported Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Subjects From Copdgene CohortДокумент9 страницImpact of Self-Reported Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Subjects From Copdgene CohortkasabeОценок пока нет

- The Accuracy Rate of Alvarado Score, Ultrasonography, and Computerized Tomography Scan in The Diagnosis of Acute Appendicitis in Our CenterДокумент7 страницThe Accuracy Rate of Alvarado Score, Ultrasonography, and Computerized Tomography Scan in The Diagnosis of Acute Appendicitis in Our CenterAlya FanoОценок пока нет

- Fan Therapy For The Treatment of Dyspnea in Adult, Sistematic ReviewДокумент6 страницFan Therapy For The Treatment of Dyspnea in Adult, Sistematic ReviewSaputra IanОценок пока нет

- Chest CT For Detecting COVID-19 A Systematic RevieДокумент14 страницChest CT For Detecting COVID-19 A Systematic RevieWiseup StudioОценок пока нет

- Pneumonia in The Immunocompetent Child ETДокумент32 страницыPneumonia in The Immunocompetent Child ETVianney OlveraОценок пока нет

- Borderline Personality DisorderДокумент6 страницBorderline Personality DisorderPersephona13Оценок пока нет

- Lateral Flow Devices Paper Version For CLIN MED - 03.07.22 BLДокумент31 страницаLateral Flow Devices Paper Version For CLIN MED - 03.07.22 BLAshwin KumaranОценок пока нет

- Autonomic Neuropathy in Patients With HIV: Course, Impact of Disease Stage, and MedicationДокумент6 страницAutonomic Neuropathy in Patients With HIV: Course, Impact of Disease Stage, and MedicationkarinarakhmaОценок пока нет

- Laboratory Tests For Pneumonia in General Practice The Diagnostic Values Depend On The Duration of IllnessДокумент8 страницLaboratory Tests For Pneumonia in General Practice The Diagnostic Values Depend On The Duration of IllnesskaeranОценок пока нет

- Validation of The Serbian Version of The Asthma Control TestДокумент8 страницValidation of The Serbian Version of The Asthma Control TestDragana KrsticОценок пока нет

- Document 2Документ10 страницDocument 2felitaОценок пока нет

- Lary 26606Документ6 страницLary 26606raghad.bassalОценок пока нет

- 6 PDFДокумент8 страниц6 PDFnigoОценок пока нет

- JamaДокумент11 страницJamaISABEL SOFIA CABARCAS COGOLLOОценок пока нет

- Attention, Arousal and Other Rapid BedsideДокумент10 страницAttention, Arousal and Other Rapid Bedsideanuraag lohmrorОценок пока нет

- Do Not Copy: Dementia Is Associated With Chronic Rhinosinusitis: A Population-Based Case-Controlled StudyДокумент5 страницDo Not Copy: Dementia Is Associated With Chronic Rhinosinusitis: A Population-Based Case-Controlled StudyDominique MendozaОценок пока нет

- Heart & Lung: Ying Guo, MD, Wei Gao, MD, Hongxia Yang, MD, Cheng 'En Ma, MD, Shujian Sui, MDДокумент6 страницHeart & Lung: Ying Guo, MD, Wei Gao, MD, Hongxia Yang, MD, Cheng 'En Ma, MD, Shujian Sui, MDnoviОценок пока нет

- Quality of Life After Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Patients With Chronic RhinosinusitisДокумент15 страницQuality of Life After Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Patients With Chronic RhinosinusitisNarendraОценок пока нет

- Contoh Systematic Review Dan Meta AnalysisДокумент13 страницContoh Systematic Review Dan Meta AnalysisAYOG1112Оценок пока нет

- Diagnosing Pneumonia in Patients With Acute Cough: Clinical Judgment Compared To Chest RadiographyДокумент7 страницDiagnosing Pneumonia in Patients With Acute Cough: Clinical Judgment Compared To Chest RadiographyCaptain NarongОценок пока нет

- Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) As A Monitoring Tool For Daily Changes in Asthma Symptoms in Adolescents: A Prospective StudyДокумент8 страницVisual Analogue Scale (VAS) As A Monitoring Tool For Daily Changes in Asthma Symptoms in Adolescents: A Prospective StudyyohanaОценок пока нет

- Cohort StudyДокумент19 страницCohort StudyRoro RageyОценок пока нет

- Significance of Nasal Polyps in Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Symptoms and Surgical OutcomesДокумент5 страницSignificance of Nasal Polyps in Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Symptoms and Surgical OutcomesbagasОценок пока нет

- Sr. Director: 226 DE Tripoloni. Carta Al Editor. Rev Argent Cirug 2020 112 (3) :225-226Документ2 страницыSr. Director: 226 DE Tripoloni. Carta Al Editor. Rev Argent Cirug 2020 112 (3) :225-226Dayanna DiazОценок пока нет

- Diagnostic Tests in Pediatric Pulmonology: Applications and InterpretationОт EverandDiagnostic Tests in Pediatric Pulmonology: Applications and InterpretationStephanie D. DavisОценок пока нет

- A B C D E F G: Stadsplan Plano de La Ciudad Plan de Ville Stadtplan City MapДокумент2 страницыA B C D E F G: Stadsplan Plano de La Ciudad Plan de Ville Stadtplan City MappisucamiОценок пока нет

- SM SB : 3Fhjtufszpvsofx#PtdiopxДокумент48 страницSM SB : 3Fhjtufszpvsofx#PtdiopxpisucamiОценок пока нет

- Synology NAS User's Guide: Based On DSM 6.1Документ73 страницыSynology NAS User's Guide: Based On DSM 6.1pisucamiОценок пока нет

- Vacuum Cleaner S270i Blue Sapphire s270 CaribicДокумент24 страницыVacuum Cleaner S270i Blue Sapphire s270 CaribicpisucamiОценок пока нет

- Pneumovax PiДокумент9 страницPneumovax PipisucamiОценок пока нет

- 100most InflДокумент496 страниц100most InflpisucamiОценок пока нет

- Goya in The Metropolitan Museum of ArtДокумент82 страницыGoya in The Metropolitan Museum of ArtNemanja NikolićОценок пока нет

- Idea PadДокумент1 страницаIdea PadpisucamiОценок пока нет

- Anaesthesia For The Obese Patient: A. Wynn-Hebden and D.C. BouchДокумент8 страницAnaesthesia For The Obese Patient: A. Wynn-Hebden and D.C. BouchdullzineaaОценок пока нет

- Pediatric Asthma Situation in Chengdu, China, During The COVID-19 Pandemic: An Observational StudyДокумент10 страницPediatric Asthma Situation in Chengdu, China, During The COVID-19 Pandemic: An Observational StudyzainabОценок пока нет

- Profesional AnamnesisДокумент2 страницыProfesional AnamnesisAna MariaОценок пока нет

- ThesisДокумент30 страницThesisSimran JosanОценок пока нет

- The Amazing Science of AuriculotherapyДокумент26 страницThe Amazing Science of AuriculotherapyNatura888100% (13)

- Chronic Conditions QДокумент47 страницChronic Conditions QahmadranauiОценок пока нет

- Ati Med SurgДокумент36 страницAti Med SurgVanessaMUeller94% (17)

- BHS InggrisДокумент5 страницBHS InggrisDeajeng Febby AyuОценок пока нет

- Ahmed Copd Case StudyДокумент6 страницAhmed Copd Case StudyAhmad BaolayyanОценок пока нет

- Acute Asthma ExacerbationДокумент3 страницыAcute Asthma ExacerbationRoa Al-SajjanОценок пока нет

- Children's Hospital Association of Texas Asthma Management Pathway (ED and IP) Asthma ScoresДокумент4 страницыChildren's Hospital Association of Texas Asthma Management Pathway (ED and IP) Asthma ScoresMumunni MoretzОценок пока нет

- 2002, Vol.86, Issues 5, AsthmaДокумент229 страниц2002, Vol.86, Issues 5, AsthmaFaisal H RanaОценок пока нет

- Medical EbooksДокумент60 страницMedical EbooksKharis Mustofa100% (2)

- 2006 129 1344-1348 Christopher E. Brightling: Clinical Applications of Induced SputumДокумент7 страниц2006 129 1344-1348 Christopher E. Brightling: Clinical Applications of Induced Sputumjoal510Оценок пока нет

- Drug ListДокумент18 страницDrug ListMinh PhungОценок пока нет

- Pathophysiology of AsthmaДокумент2 страницыPathophysiology of AsthmaAhyz100% (3)

- Asthma Action Plan For Children PDF DownloadДокумент2 страницыAsthma Action Plan For Children PDF DownloadAlejandro MalagáОценок пока нет

- How To Write Summary EssayДокумент7 страницHow To Write Summary EssayxtnzpacafОценок пока нет

- AsthmaДокумент45 страницAsthmaRaquel M. MendozaОценок пока нет

- A3 Literacy Booklet Revised Spring 2013Документ157 страницA3 Literacy Booklet Revised Spring 2013yavuzsultan34Оценок пока нет

- SABA Reliance Questionnaire (SRQ) FulltextДокумент34 страницыSABA Reliance Questionnaire (SRQ) FulltextPhụng KimОценок пока нет

- Pre - Assessment: Directions: Complete Each Statement by Writing The Missing Word On Your HealthДокумент3 страницыPre - Assessment: Directions: Complete Each Statement by Writing The Missing Word On Your HealthMary Rose QuimanjanОценок пока нет

- COPD 2 Management and Nursing CareДокумент4 страницыCOPD 2 Management and Nursing CareAyman Nabil100% (1)

- Medical Disorder Considerations in Orthodontic Patients NДокумент115 страницMedical Disorder Considerations in Orthodontic Patients Nshubhangi_jain_10Оценок пока нет

- Nclex 4Документ76 страницNclex 4Clariz MercadoОценок пока нет

- Asthma: Rochelle M. Nolte, MD CDR Usphs Family MedicineДокумент56 страницAsthma: Rochelle M. Nolte, MD CDR Usphs Family MedicineJoan Marie Lechado InoviaОценок пока нет

- Thesis Topics For MD Respiratory MedicineДокумент7 страницThesis Topics For MD Respiratory Medicinelindseyriverakansascity100% (2)

- Foreign Body Aspiration in Children-A Diagnostic ChallengeДокумент3 страницыForeign Body Aspiration in Children-A Diagnostic ChallengeViany RehansyahОценок пока нет

- CMO 09 s2007Документ55 страницCMO 09 s2007XtiaRОценок пока нет

- Test Unit 2 Urbanisation L P 12Документ9 страницTest Unit 2 Urbanisation L P 12Xuân NguyenОценок пока нет