Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Story Teling Story Making1

Загружено:

Janice bordenОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Story Teling Story Making1

Загружено:

Janice bordenАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

1 of 9 The National Strategies Primary

‘Storytelling’ by Pie Corbett

Storytelling and story-making

The idea of story-making was initially developed with my colleague, Mary Rose, through a

teacher research project based at the International Learning and Research Centre in South

Gloucestershire, funded by what was known as the DFES Innovations unit. We explored the use

of storytelling as a tool for helping children build up a bank of narrative patterns that they could

then call upon when they wish to create their own stories.

Over time, local authorities (LAs) and clusters of schools have found that story-making is a

powerful strategy for both improving boys’ writing and helping children who struggle with literacy

to gain success. It is also a powerful strategy for children for whom English is an additional

language because it enables them to build on their knowledge of storytelling in their first

language and supports the development of the additional language. The new narrative

progression attached to the Primary Framework for literacy identifies the progression in narrative

writing alongside storytelling.

The idea is quite simple. The first stage is for children each year to learn to tell orally a bank of

stories, for example, The Gingerbread Man in Reception and then another ten in Year 1. This

means that they enter Year 2, knowing up to 20 stories. Thereafter they might work with one

story every half-term, therefore acquiring a bank of about 50 stories across the primary years.

These stories would come from the wide range of cultures in our diverse society.

Children internalise:

‘big’ patterns that are revisited, such as ‘quest’ or ‘journey’ stories – in this way basic plots

can act as blueprints for the imagination. As Samuel Johnson said: ‘The same images, with

very little variation, have served all the authors who have ever written.’

the building blocks of narrative – common characters, settings, events, the rise and fall of

narrative patterning

the flow of sentences, the syntactical patterns

the vocabulary – especially, connectives that link and structure narrative such as: once upon

a time, one day, so, next, but, finally

Most importantly, they develop an imaginative world of images that can be drawn upon and day-

dreamed about to invent new stories.

The stories are taught in a multi-sensory manner. Actions are used to make the tales, especially

the key connectives, memorable. Each story has a story map or board as a visual reminder.

Activities such as puppets, role-play, hot-seating and acting out are used to bring the tale alive

and make it memorable. At the start of this work, most of the children in Reception classes were

unable to tell a story. In our sample group, only two per cent of Reception children were able to

retell a whole story. By the end of the year, 76 per cent of the children were able to retell a whole

story with 100 per cent able to retell a good chunk.

00467-2008PDF-EN-04 © Pie Corbett

Story Making and 3 Stage Methodology ©

International Learning and Research Centre.

Used with kind permission.

2 of 9 The National Strategies Primary

‘Storytelling’ by Pie Corbett

The story-making process

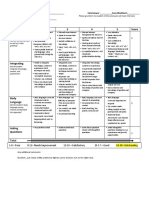

IMITATION – familiarisation

Retelling a story until it can be told fluently

Multi-sensory approach, made memorable

INNOVATION – adapting a well-known tale

Substitution, addition, alteration, change of viewpoint and reusing the basic story

pattern

INVENTION – creating your own new story

Building up a story – drawing, drama, images, video, first-hand experience, location,

quality reading, etc.

Imitation – familiarisation

Listen – join in – retell.

Communal retelling involves everyone saying the same words in the same way we might learn a

song together. Through constant repetition, the children end up knowing the story by heart. This

is crucial for young children, those new to the English language as well as older pupils who have

missed out on internalising narrative patterns. It is great fun, provides a genuine sense of

accomplishment and is inclusive. It also helps children make progress.

Initially, retelling happens as a whole class, followed by story circles and then with partners. The

teacher gradually withdraws so that in the end the children can retell the tale on their own. Move

to group retellings only when the class can chant it without the teacher dominating the retelling.

It is a movement from dependence to independence. If stories can be taped or taught to parents

by the children then families may become involved.

As children develop competency in story-making and internalise narrative patterns, stories do

not have to be learned word for word. Competent storymakers can launch straight into

independent retelling with their own innovations. They can listen to a story several times, draw a

map and work in pairs, taking turns, to develop a retelling. They will need to retell the story a

number of times to refine the tale and gain fluency.

Making a story memorable.

Comprehension – you may wish to carry out a range of comprehension activities such as

‘book-talk’, response, close reading and DARTs activities.

When the children know the story well, it may be appropriate to show them a written version of

the story. One boy surprised himself by being able to reread a story that previously he had not

been able to tackle at all!

00467-2008PDF-EN-04 © Pie Corbett

Story Making and 3 Stage Methodology ©

International Learning and Research Centre.

Used with kind permission.

3 of 9 The National Strategies Primary

‘Storytelling’ by Pie Corbett

Drama helps children get to know the text really well – often having to listen again to and reuse

parts of the text. With older children, drama activities are especially useful for encouraging a

return to the original text to internalise the patterns and interpretation. Also, drama can help

children begin to generate new ideas for their own writing.

Writing in role – if you want the children to write in role, or create something new, then it may

be worth combining drama or storytelling with drawing, plus an opportunity to retell so that ideas

and language can be refined/revised.

Making the story memorable – if you are retelling The Magic Porridge Pot – then bring in a

magic pot, cook porridge…. If you are retelling Red Riding Hood then bring in a red cloak. If you

are retelling Handa’s surprise, bring in the fruits and have animal masks. The more a story is

recreated and represented in different forms, the more likely it is to live as a memorable

metaphor in children’s minds. A flimsy relationship with a story will leave only the vaguest of

traces in their imaginations. Bring stories alive. As educationalists we are interested in how

storytelling might help children cumulatively acquire language and influence writing – but we

must not lose sight of the idea that stories are experiences – not just vehicles for learning

language or the passing on of information.

Read as a writer – through problem-solving the text. ‘I suspect many writers read books the way

mechanics look at cars, with an eye to what is going on under the bonnet.’ (Paul Muldoon)

Looking at stories with a writerly eye can help children to become more aware of structures and

strategies that writers use to create different effects.

Using the writing journal – identify the overall pattern or structure, the language features and

other writerly tips and hints. These can be logged on wall charts or examples collected in a

writing journal which acts as a storehouse of all the useful things that they have been taught that

might be referred to when writing – a sort of writing thesaurus. This drives shared writing, the

children’s own writing and self-evaluation, as well as the teacher’s marking. This provides clarity

and direction. It also means that the word and sentence level work purposefully becomes about

language usage to create different effects and impact.

Practise word and sentence features – orally, or on mini-whiteboards, rehearse writerly

techniques, sentence features and spellings, ultimately to be used in the children’s own writing.

Innovation – developing from known stories on known stories

The next step is to take a well-known story and adapt it to make it your own. There are various

different changes that can be made. A simple ‘substitution’ might involve changing names,

places or objects. Children will be familiar with many simple substitutions that build on cultural

familiarity – The runaway pancake and The runaway chapatti. Adding in new scenes or extra

detail is often a quite natural development. This might be simply a matter of adding in a few

adjectives or embellishing the tale considerably. Alterations might be made to settings, character

and key events. The story could be retold from a different viewpoint or recast as a diary, letter or

news item. For instance, I once saw The three bears performed as a rap – and have also seen it

rewritten as a ‘break and entry’ thriller in which the main character enters a house, steals

something and is then caught by the owner!

00467-2008PDF-EN-04 © Pie Corbett

Story Making and 3 Stage Methodology ©

International Learning and Research Centre.

Used with kind permission.

4 of 9 The National Strategies Primary

‘Storytelling’ by Pie Corbett

Only move on to innovation when the story is in the long-term working memory – otherwise, the

children will struggle to innovate. Each stage needs to be modelled by the teacher so that there

is a whole-class innovation. This then sets the scene for the children gradually to create their

own innovation.

Substitutions

This seems to be the simplest form of innovation. Many children find it simple enough to alter

basic names of characters, places and objects.

Additions

This may make a second simple enough stage. The child keeps the same basic pattern and

sentences. However, extra sentences are added in, embellishing the original. These might

include:

simple additions, for example, one day = one sunny day

adding in more description

adding in more dialogue

adding in new characters or events

adding in extra detail to bring scenes alive.

Alterations

An ‘alteration’ is a significant change that has consequences, usually altering the story in some

fashion:

altering characters, for example, so that a good character becomes greedy

altering settings, for example, so that a character journeys through a housing estate rather

than a forest

altering events but sticking to the basic plot

altering the plot structure, for example, the way the story opens or ends.

Change of viewpoint

The story plot is used as a basis for a retelling from a new viewpoint:

retelling in a different form (text-type) – for example, as a letter, diary entry

retelling from a different character’s view

retelling in a totally new setting, for example, Little Charlie in a city

retelling in a different time, for example, The three bears in modern times

retelling in a different genre or text-type, for example, as a letter.

Reuse the basic plot

This involves unpicking the basic plot and recycling it in a new setting with new characters and

events.

00467-2008PDF-EN-04 © Pie Corbett

Story Making and 3 Stage Methodology ©

International Learning and Research Centre.

Used with kind permission.

5 of 9 The National Strategies Primary

‘Storytelling’ by Pie Corbett

Moving from telling into writing

It is worth noting that the quality of children’s innovations is in direct relation to the quality of

class innovation and shared writing. When turning the class innovation into writing, retell the

story as you write. With younger children, write the story as it has been learned. More

experienced writers may use the known version as a skeleton so that as you write the story

down you can show the children how to embellish, drawing on reading and ensuring that the

shared writing demonstrates progress. Use shared writing to teach:

thinking about audience and purpose

using key strategies, for example, gathering ideas, organising ideas, transforming plans into

writing, polishing and presenting

drawing on the told story and the reading of mentor texts – for the overall structure, sentence

and word features as well as characterisation, dialogue, action, suspense, using hooks to

intrigue the reader

using the writing journal as a reference.

For younger children and weaker writers this means that when they settle down to write, they

already know what they are going to say. This releases cognitive space. The children are not

trying to cope with the demands of transcription at the same time as composition. Because they

already know their story well, they are more motivated and will put in more effort to transcribe

their story. The act of writing has been made easier because they know what they are going to

say. This frees the brain so that it can concentrate on getting the story down onto the page. This

is why some children make dramatic progress. Teachers need to use shared writing to

encourage progress.

Writing in front of the children may be a blend of demonstration (I’ll show you) and teacher

scribing (You have a go and I’ll write it down). In teacher scribing, the teacher challenges weak

suggestions and challenges the children to draw on features and examples that will ensure

progress. The aim is to keep on showing them and talking through aspects of writing so that if

they then do the same sort of thing it will help them make progress. Assessment of the children’s

writing informs shared writing.

Older children – probably from Year 2 onwards – develop the story at the point of composition. It

is important to set different story challenges within a class so some may be simply substituting

while others are embellishing and altering to level 5.

00467-2008PDF-EN-04 © Pie Corbett

Story Making and 3 Stage Methodology ©

International Learning and Research Centre.

Used with kind permission.

6 of 9 The National Strategies Primary

‘Storytelling’ by Pie Corbett

The story innovation process

Tell the new story with actions.

Draw a new story map or story board.

Retell the story daily – with the children increasingly joining in while the teacher gradually

withdraws.

Move on to story circles and pairs.

Once the children have internalised the story into their long-term working memory, begin

innovation.

Teacher models an innovation and creates a new story map or story board.

The teacher demonstrates how to use this to retell the new version.

Class and teacher retell new version.

Teacher leads the children through creating their innovation.

Children draw their new map and retell their innovation.

Shared writing of class innovation.

Pupils write or record their own innovations.

Polishing and publishing of stories.

00467-2008PDF-EN-04 © Pie Corbett

Story Making and 3 Stage Methodology ©

International Learning and Research Centre.

Used with kind permission.

7 of 9 The National Strategies Primary

‘Storytelling’ by Pie Corbett

Developing a story

When the children know the basic story and can retell it fluently they are able to develop the

actual wording. Be careful that they do not embellish a story so much that it becomes too wordy

and the narrative is lost.

A simple ‘story grid’ or flow chart can be drawn to provide a visual overview of each ‘scene’ or

main event. Use this to focus on:

description – people, places, objects, creatures

characterisation and dialogue

suspense and action

crafting the opening and ending.

Don’t work on everything at once – just select a focus. Model ideas, to influence the class

version of a story. Then ask children to work in pairs or individually. Some key points of ‘writing

knowledge’ might include:

Characterisation

Choose a name.

Give a few descriptive details.

How is the character feeling and why, for example, angry – or what type are they, perhaps

bossy or shy.

Show this through what they say or do.

What is their desire, for example, she wants a pet.

Develop and change character across the story.

Dialogue

Think about how they feel.

Use powerful speech verbs.

Use said + adverb.

Insert stage direction to show what a character is doing when speaking, for example, ‘No,’ he

hissed, shaking his head in disgust.

Use only a few exchanges.

Description – people, places, objects

Use well-chosen adjectives.

Use similes and metaphors.

Use senses and concrete detail.

Show things through the character’s eyes, for example, She stared at….

Describe key objects.

Describe settings to create atmosphere.

Describe the weather and time of day.

00467-2008PDF-EN-04 © Pie Corbett

Story Making and 3 Stage Methodology ©

International Learning and Research Centre.

Used with kind permission.

8 of 9 The National Strategies Primary

‘Storytelling’ by Pie Corbett

Openings

Character – Bill stared at the burger in disgust.

Setting – A fly crawled up the window pane.

Action – Jo ran.

Talk – ‘Put that down!’

Use a hook – Usually, Jasbir enjoyed walking to school but…

Endings

Show character’s feelings – Marika grinned.

Comment on what has been learned – They knew it had been stupid….

Action and suspense

Balance short and long sentences.

Use questions to draw reader in.

Use exclamations for impact.

Place character in a lonely, dark place.

Introduce an ominous sound effect, for example, something hissed.

Show a glimpse of something, for example, a hand appeared at the door.

Use dramatic connectives, for example, at that moment….

Use empty words, for example, something, somebody, it.

Use powerful verbs, for example, run, jump, grip, grab, struggle.

Invention – orally creating a new story

In story-making schools, children are constantly in the process of either learning a story or

innovating. This is a daily ongoing process especially at Key Stage 1. But they also need to get

used to making stories up from themselves, drawing on their bank of told stories as well as their

lives. To do this, hold regular weekly story-inventing sessions.

These should be:

oral

guided by the teacher

reusing familiar characters, settings and patterns

reusing story language

an opportunity for new ideas, drawing on a range of stories and life.

It is worth bearing in mind the following advice.

Keep the stories simple – build the end in early to avoid rambling!

Capturing the story

Of course, you may wish to just make the story up and leave it at that. It might be captured in

writing, with a Dictaphone or video. Or, just by drawing:

story map – Story Mountain – story flow chart or story board.

00467-2008PDF-EN-04 © Pie Corbett

Story Making and 3 Stage Methodology ©

International Learning and Research Centre.

Used with kind permission.

9 of 9 The National Strategies Primary

‘Storytelling’ by Pie Corbett

Start from the basic story ingredients.

Begin by discussing the key questions.

Who – build up a character.

Where – does the story take place?

What – will happen? Bear in mind that you will need something to go wrong – a dilemma or

problem or mystery or exciting event.

If you get stuck, use a story trigger; have something happen such as a phone ringing, a new

character entering, someone screaming.

Using a basic plot

Many schools have identified key plots that the children meet every year – one per half-term. In

this way the children become familiar with a basic pattern that may be reused in endless

permutations.

Problems and resolutions

Warning.

Quest – a to b, there and back again.

Wishing.

Lost/found.

Defeating the monster, for example, Gary had never believed in trolls – or – Gary had always

been afraid of being trapped in dark places.

Cinderella.

Character flaw (tragedy).

Cumulative, for example, The very hungry caterpillar.

Traditional (myths, fables, etc.).

If children are building up to writing it is worth following this pattern.

Draw your story – making decisions about what will happen.

Use the drawing to tell the story to a partner, by word of mouth.

Discuss the story with your partner, taking suggestions for improvement.

Retell the story with refinements.

The more you retell aloud or in your head, the better you get to know the story, the more it can

be improved.

Once the plot has developed, use story grids to work on characterisation, description, etc.

As you write the story, retell it again in your head, tweaking it where necessary.

Pie Corbett, April 2008

00467-2008PDF-EN-04 © Pie Corbett

Story Making and 3 Stage Methodology ©

International Learning and Research Centre.

Used with kind permission.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Jones (2005) Gatekeepers, Midwives, and Fellow TravellersДокумент14 страницJones (2005) Gatekeepers, Midwives, and Fellow TravellersTanja CvijanovicОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Model Paper - I: Market ResearchДокумент4 страницыModel Paper - I: Market Researchazam49Оценок пока нет

- Multimodal Research ProjectДокумент12 страницMultimodal Research Projectapi-273392563Оценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Pedagogical Grammar On Adverbials and AuxiliariesДокумент32 страницыPedagogical Grammar On Adverbials and Auxiliarieselijahrosejune .ferreraОценок пока нет

- Scope and Sequence 2014 Journeys gr4Документ15 страницScope and Sequence 2014 Journeys gr4api-347346936Оценок пока нет

- Linguistics and Language TeachersДокумент2 страницыLinguistics and Language Teachersleomargiu32Оценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Event Valence and Spatial Metaphor of TimeДокумент16 страницEvent Valence and Spatial Metaphor of TimeestelaОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Basic Needs Checklist For DepressionДокумент2 страницыBasic Needs Checklist For DepressionFernandoSuarez100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Chapter 8Документ49 страницChapter 8RosmarinusОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Humms Discipline Grade 11 Exam Legit Basta PCДокумент22 страницыHumms Discipline Grade 11 Exam Legit Basta PCJersty Golpeo91% (11)

- GrammarДокумент34 страницыGrammarChoi DongYiОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Other Affective Measures and AssessmentGroup3Документ2 страницыOther Affective Measures and AssessmentGroup3astro haОценок пока нет

- Assignment On Motivation and Intelligence PDFДокумент1 страницаAssignment On Motivation and Intelligence PDFTasfiq WahedОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Coordinating Conjunction RulesДокумент4 страницыCoordinating Conjunction RulesHanie Balmedina-RazoОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- ToleranceДокумент2 страницыTolerancePopa GeorgianaОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Bischoff ThesisДокумент86 страницBischoff ThesisLeeTeng TeeОценок пока нет

- Real Time Object Detection Using Deep LearningДокумент6 страницReal Time Object Detection Using Deep LearningIJRASETPublicationsОценок пока нет

- Rubric For SymposiumДокумент3 страницыRubric For SymposiumShane Nones100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Mock Interview Rubric 002 1Документ1 страницаMock Interview Rubric 002 1api-532105563Оценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- MBA Project MarketingДокумент22 страницыMBA Project MarketingSaurabh0% (1)

- 446-01 Introduction (N)Документ12 страниц446-01 Introduction (N)Irfan MahyunisОценок пока нет

- The Evolving Landscape of EducationДокумент2 страницыThe Evolving Landscape of EducationStone HeartОценок пока нет

- Installation Art - MarkДокумент2 страницыInstallation Art - Markapi-608905236Оценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Difficult Emotions Self Help Booklet Indigo DayaДокумент12 страницDifficult Emotions Self Help Booklet Indigo Dayaapi-360754295100% (3)

- Expressing Your Views Assess RubricДокумент3 страницыExpressing Your Views Assess RubricJocelle BautistaОценок пока нет

- Market Mirror Global CATI CapabilityДокумент9 страницMarket Mirror Global CATI CapabilityTushar SharmaОценок пока нет

- 24th Annual Computational Neuroscience Meeting: CNS 2015Документ200 страниц24th Annual Computational Neuroscience Meeting: CNS 2015Oleg NikitinОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Sse 223Документ153 страницыSse 223Alaje Balogun KehindeОценок пока нет

- Job Performance ResearchДокумент47 страницJob Performance ResearchLantretz LaoОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan TemplateДокумент3 страницыLesson Plan TemplateАбденнур Абденнур ДжемаОценок пока нет