Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Supreme Court of India Page 1 of 5

Загружено:

vinayaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Supreme Court of India Page 1 of 5

Загружено:

vinayaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

http://JUDIS.NIC.

IN SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Page 1 of 5

CASE NO.:

Appeal (crl.) 1040 of 2004

PETITIONER:

State of U.P. and Anr.

RESPONDENT:

Sanjai Pratap Gupta @ Pappu and Ors.

DATE OF JUDGMENT: 20/09/2004

BENCH:

ARIJIT PASAYAT & C.K. THAKKER

JUDGMENT:

J U D G M E N T

(Arising out of SLP(Crl.)No. 4267/2003)

ARIJIT PASAYAT, J.

Leave granted.

Respondent No.1-Sanjai Pratap Gupta@Pappu (hereinafter referred

to as the ’detenu’) was detained pursuant to an order of detention

passed under Section 3(2) of the National Security Act, 1980 (in short

the ’Act’). The order dated 23.12.2002 was served on the detenu on that

day itself. According to the order and grounds of detention, the

activities of the detenu were considered to be prejudicial to public

order. Specific reference was made to an incident dated 13.10.2002. One

Anand Kumar Jain lost his life because of the firing done by the detenu

and his associates. Attempt to take away the life of one Ajay Kumar

Jain, son of aforesaid Anand Kumar Jain was made, but luckily he had

escaped. Case was registered for commission of offences punishable

under Sections 302 and 307 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (in short the

’IPC’). Reference was also made to several earlier incidents which

according to the detaining authority highlighted the criminal

antecedents of the detenu and as to how he was creating a sense of

terror in the minds of the general public. With a view to prevent him

from committing similar prejudicial acts and to maintain public order

the order of detention was purportedly passed.

A habeas corpus petition was filed under Article 226 of the

Constitution of India, 1950 (in short the ’Constitution’) by the detenu

questioning validity of the order of detention. By the impugned

judgment the High Court accepted the prayer and quashed the order of

detention. Before the High Court stand of the detenu was that the two

aspects highlighted in the grounds of detention were not separable and

were intimately linked with one another. As necessary documents to

substantiate the allegations relating to earlier incidents were not

supplied to the detenu that rendered the order of detention invalid.

Stand of the State on the other hand was that the two aspects

were separable. Even if for the sake of arguments one part was held to

be not supportable that really was of no consequence in view of Section

5-A of the Act. The High Court proceeded on the basis that the two

aspects highlighted were inter-dependent and there was no question of

separately considering the two aspects. Accordingly, the order of

detention was passed.

In support of the appeal, learned counsel for the appellant-State

http://JUDIS.NIC.IN SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Page 2 of 5

submitted that the scope and ambit of Section 5-A of the Act has been

completely lost sight of by the High Court. One aspect which was

highlighted related to the criminal antecedents of the detenu and as to

how there were many cases registered against him in the past for being

treated him as a history sheeter. The second aspect related to a

particular incident. The effect of the act was highlighted in the

grounds of detention which was clearly spelt out as to how even tempo

of life got disturbed by the act. Though, the detenu was in custody,

taking into account the likelihood of his release on bail the order of

detention was passed. Necessary documents like the bail application

etc. were also supplied to the detenu. Learned counsel for the Union

of India supported the stand of the State.

In response, learned counsel for the detenu submitted that the

two aspects indicated in the grounds of detention cannot be separated,

one has its effects on the other and the High Court has rightly held

them to be inseparable. In view of the factual position, Section 5-A of

the Act has no application. Additionally, the incident which formed

the foundation for the order of detention was at the most law and order

situation and not a public order situation. Finally, it was submitted

that even if it is held that the judgment of the High Court is bad yet

direction should not have been given for taking him back to detention

because of long passage of time and in the absence of any live link

between the alleged incident and the requirement for his continued

detention. A single act could not have been considered as sufficient

to affect public order warranting detention. Strong reliance is placed

on Sunil Fulchand Shah v. Union of India and Ors. (2000 (3) SCC 409)

The crucial issue is whether the activities of the detenu were

prejudicial to public order. While the expression ’law and order’ is

wider in scope inasmuch as contravention of law always affects order.

’Public order’ has a narrower ambit, and public order could be affected

by only such contravention which affects the community or the public at

large. Public order is the even tempo of life of the community taking

the country as a whole or even a specified locality. The distinction

between the areas of ’law and order’ and ’public order’ is one of the

degree and extent of the reach of the act in question on society. It is

the potentiality of the act to disturb the even tempo of life of the

community which makes it prejudicial to the maintenance of the public

order. If a contravention in its effect is confined only to a few

individuals directly involved as distinct from a wide spectrum of

public, it could raise problem of law and order only. It is the length,

magnitude and intensity of the terror wave unleashed by a particular

eruption of disorder that helps to distinguish it as an act affecting

’public order’ from that concerning ’law and order’. The question to

ask is: "Does it lead to disturbance of the current life of the

community so as to amount to a disturbance of the public order or does

it affect merely an individual leaving the tranquility of the society

undisturbed"? This question has to be faced in every case on its facts.

"Public order" is what the French call ’ordre publique’ and is

something more than ordinary maintenance of law and order. The test to

be adopted in determining whether an act affects law and order or

public order, is: Does it lead to disturbance of the current life of

the community so as to amount to disturbance of the public order or

does it affect merely an individual leaving the tranquility of the

society undisturbed? (See Kanu Biswas v. State of West Bengal (AIR 1972

SC 1656).

"Public order" is synonymous with public safety and tranquility:

"it is the absence of disorder involving breaches of local significance

in contradistinction to national upheavals, such as revolution, civil

strife, war, affecting the security of the State". Public order if

disturbed, must lead to public disorder. Every breach of the peace does

not lead to public disorder. When two drunkards quarrel and fight there

http://JUDIS.NIC.IN SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Page 3 of 5

is disorder but not public disorder. They can be dealt with under the

powers to maintain law and order but cannot be detained on the ground

that they were disturbing public order. Disorder is no doubt prevented

by the maintenance of law and order also but disorder is a broad

spectrum, which includes at one end small disturbances and at the other

the most serious and cataclysmic happenings. (See Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia

v. State of Bihar and Ors. (1966 (1) SCR 709)

’Public Order’, ’law and order’ and the ’security of the State’

fictionally draw three concentric circles, the largest representing law

and order, the next representing public order and the smallest

representing security of the State. Every infraction of law must

necessarily affect order, but an act affecting law and order may not

necessarily also affect the public order. Likewise, an act may affect

public order, but not necessarily the security of the State. The true

test is not the kind, but the potentiality of the act in question. One

act may affect only individuals while the other, though of a similar

kind, may have such an impact that it would disturb the even tempo of

the life of the community. This does not mean that there can be no

overlapping, in the sense that an act cannot fall under two concepts at

the same time. An act, for instance, affecting public order may have an

impact that it would affect both public order and the security of the

State. [See Kishori Mohan Bera v. The State of West Bengal (1972 (3)

SCC 845); Pushkar Mukherjee v. State of West Bengal (1969 (2) SCR 635);

Arun Ghosh v. State of West Bengal (1970 (3) SCR 288); Nagendra Nath

Mondal v. State of West Bengal (1972 (1) SCC 498).

The distinction between ’law and order’ and ’public order’ has

been pointed out succinctly in Arun Ghosh’s case (supra). According to

that decision the true distinction between the areas of ’law and order’

and ’public order’ is "one of degree and extent of the reach of the act

in question upon society". The Court pointed out that "the act by

itself is not determinant of its own gravity. In its quality it may not

differ but in its potentiality it may be very different". (See Babul

Mitra alias Anil Mitra v. State of West Bengal and Ors. (1973 (1) SCC

393, Milan Banik v. State of West Bengal (1974 (4) SCC 504).

The true distinction between the areas of law and order and

public order lies not merely in the nature or quality of the act, but

in the degree and extent of its reach upon society. Acts similar in

nature, but committed in different contexts and circumstances, might

cause different reactions. In one case it might affect specific

individuals only, and therefore touches the problem of law and order

only, while in another it might affect public order. The act by itself,

therefore, is not determinant of its own gravity. In its quality it may

not differ from other similar acts, but in its potentiality, that is,

in its impact on society, it may be very different.

The two concepts have well defined contours, it being well

established that stray and unorganized crimes of theft and assault are

not matters of public order since they do not tend to affect the even

flow of public life. Infractions of law are bound in some measure to

lead to disorder but every infraction of law does not necessarily

result in public disorder. Law and order represents the largest scale

within which is the next circle representing public order and the

smallest circle represents the security of State. "Law and order"

comprehends disorders of less gravity than those affecting "public

order" just as "public order" comprehends disorders of less gravity

than those affecting "security of State". [See Kuso Sah v. The State of

Bihar and Ors. (1974 (1) SCC 185), Harpreet Kaur v. State of

Maharashtra (1992 (2) SCC 177), T.K. Gopal v. State of Karnataka (2000

(6) SCC 168), State of Maharashtra v. Mohd. Yakub (1980 (2) SCR 1158)].

The stand that a single act cannot be considered sufficient for

holding that public order was affected is clearly without substance.

http://JUDIS.NIC.IN SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Page 4 of 5

It is not the number of acts that matters. What has to be seen is the

effect of the act on even tempo of life, the extent of its reach upon

society and its impact.

From the grounds of detention it is apparent that the same was

not a law and order situation but a public order situation as rightly

contended by learned counsel for the State. Relevant portion of the

grounds of detention reads as follows:

"From the letter of the Superintendent of

Police Mainpuri and the report of Incharge of the

Police Station Kotwali Mainpuri annexed with report

of the Additional Superintendent of Police, Mainpuri

and from the records annexed therewith, this is

evident that you are a person of criminal tendency

and in collaboration with your associates, and by

creating fear and terror on the force of illegal

arms, realize forcibly and illegally money from the

traders and property-dealers, you by use of criminal

force, by indulging in mar-peet (physical assault)

and by resorting to other criminal acts are habitual

to commit crime by terrorizing that person whoever

opposes these increasing criminal activities, fear

and terror psychosis has gripped the minds of the

common public. In this very backdrop you for

establishing your hegemony, while going on a scooter,

along with your other associates on 13.10.2002 at

11.00 a.m. in the busiest market of town Mainpuri,

near the Bada Chauraha (crossing) in front of the

Shafi Hotel on the road itself and in the day time,

stopped Shri Anand Kumar Jain, property dealer and by

firing bullets indiscriminately committed his heinous

murder in a planned manner. When, at the time of the

commission of this criminal act deceased’s son Ajai

Kumar Jain wanted to save his father, you fired

aiming at him who any how or other saved himself by

fleeing away.

Nobody dared, in the said busy market who could

save the deceased from you and your associates.

Consequent on the resorting by you and your

associates to the firing publicly and the show of

your criminal force, the atmosphere of fear and

terror was created in the entire market. On account

of the firing resorted to in busy market and the show

of your criminal force therein, pandemonium prevailed

among the visiting people who fled away and hid

themselves in safe places. The entire market became

empty and the public order was totally breached. The

dead body of the deceased remained lying on the road

and bleeding continued profusely. A very awful scene

was created. Nobody dared to approach the dead body

of the deceased. The deceased’s son Ajai Kumar Jain

by saving his life anyhow or other, fled away and

informed the Kotwali Mainpuri about this murder case

and the occurrence and lodged a written report with

Police Station, whereupon the first information

report was recorded at 11.45 a.m. on the basis of

which Crime No.1475/2002 was registered under Section

307/302 of the Indian Penal Code. The particulars of

this crime were recorded in brief in the General

Diary at Report No.22 at 11.45 a.m. True copies of

the FIR and report of the G.D. are annexed herewith

as Annexures 1 and 2."

http://JUDIS.NIC.IN SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Page 5 of 5

A bare perusal of the quoted portion from the grounds of

detention makes it clear that two aspects i.e. one relating to criminal

background of antecedents and other relating to a particular incident

were treated separately. This becomes apparently clear because the

detaining authority in the backdrop of the criminal antecedents

referred to the particular act. Therefore, one was the general

background, and the other was the particular incident. They are clearly

separable.

Section 5-A of the Act was introduced to take care of the

situations when one or more of the grounds can be separated from the

other grounds for justifying detention.

In Attorney General for India and Ors. v. Amratlal Prajivandas

and Ors. (1994 (5) SCC 54) it was observed that where the detention

order is based on more than one ground, by a legal fiction it would be

deemed that there are as many orders of detention as there are grounds

which means that each of such orders is an independent one. In that

case the Constitution Bench was considering scope of Section 5-A of

Conservation of Foreign Exchange and Prevention of Smuggling Activities

Act, 1974 (in short ’COFEPOSA Act’) which is in pari materia with

Section 5-A of the Act. In view of the factual position analysed, the

inevitable conclusion is that Section 5-A is applicable to the case and

the High Court was not justified in holding to the contrary. The High

Court’s judgment is therefore clearly indefensible.

The residual question to be considered is whether the detenu has

to go back to detention, after it is held that the judgment of the High

Court is not sustainable. There cannot be any straight-jacket formula

for dealing with such cases. It would depend upon circumstances of each

case. For determining the question as to whether the detenu has to go

back to detention, the factual position has to be analysed. It has to

be seen whether the effect of the previous acts was continuing or

likely to recur. When background facts of present case are considered

it is evident that the time gap is not very wide and for considerable

length of time the matter is pending in this Court and the detenu had

taken nearly three months to file his counter to the special leave

petition filed. Judged from these angles it is clear that the live link

is not snapped and the apprehension of the detaining authority about

the detenu’s prejudicial activities cannot be faulted. The impugned

judgment of the High Court is set aside. The detenu shall surrender

forthwith for serving the remainder of the period of detention. The

appeal is allowed to the aforesaid extent.

Вам также может понравиться

- Petitioner CompendiumДокумент66 страницPetitioner CompendiumKinjal KeyaОценок пока нет

- Free Speech in IndiaДокумент7 страницFree Speech in IndiaAnonymous d5TziAMОценок пока нет

- Legal Methods ProjectДокумент13 страницLegal Methods ProjectNitesh MishraОценок пока нет

- Bill of RightsДокумент44 страницыBill of RightsAnselmo Rodiel IVОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Regulation of Freedom of ExpressionДокумент20 страницConstitutional Regulation of Freedom of ExpressionJatin BakshiОценок пока нет

- Free Speech in IndiaДокумент10 страницFree Speech in IndiaAshishОценок пока нет

- Application of Natural Law in Judgments of Supreme Court of IndiaДокумент4 страницыApplication of Natural Law in Judgments of Supreme Court of IndiaSHAMBHAVI VATSAОценок пока нет

- LLB1Документ15 страницLLB1rrrmsmoreОценок пока нет

- Recognizing Customary LawДокумент14 страницRecognizing Customary LawNgcwalisa NtwalanaОценок пока нет

- Property Assignment #2Документ10 страницProperty Assignment #2Rejmali GoodОценок пока нет

- Right To Speedy TrialДокумент10 страницRight To Speedy TrialAkankshaОценок пока нет

- Whether Linking of Janaadhar With Welfare Scheme Is in Violation of Right To Privacy?Документ10 страницWhether Linking of Janaadhar With Welfare Scheme Is in Violation of Right To Privacy?Sagar KadyanОценок пока нет

- Human Rights and Adm of Criminal JusticeДокумент16 страницHuman Rights and Adm of Criminal JusticeAshok KumarОценок пока нет

- Bill of Rights by Atty. Anselmo S. Rodiel IVДокумент78 страницBill of Rights by Atty. Anselmo S. Rodiel IVAnselmo Rodiel IV100% (1)

- Article Writing - Protection of Life and Personal LibertyДокумент4 страницыArticle Writing - Protection of Life and Personal LibertyVibha Shyam SekarОценок пока нет

- 1 Introduction - Domicile & Residence1Документ7 страниц1 Introduction - Domicile & Residence1Anne VallaritОценок пока нет

- Illegal Demolitions in The Light of Domestic and International LawДокумент5 страницIllegal Demolitions in The Light of Domestic and International LawUjjwal AgrawalОценок пока нет

- Research Paper: LAND ACQUISITION: Legal & Constitutional ImplicationДокумент32 страницыResearch Paper: LAND ACQUISITION: Legal & Constitutional ImplicationAnuj AhlawatОценок пока нет

- Prisoners RightsДокумент35 страницPrisoners RightschintavineetОценок пока нет

- Eastern Book Company - Practical LawyerДокумент4 страницыEastern Book Company - Practical LawyerlegalrajivОценок пока нет

- Apoorv Gupta 212109 Section BДокумент4 страницыApoorv Gupta 212109 Section BApoorvnujsОценок пока нет

- On Free and Speedy Trial: A Critical Review of India's Judicial SystemДокумент23 страницыOn Free and Speedy Trial: A Critical Review of India's Judicial Systemnaresh mahipal100% (1)

- Judicial Activism Draft1Документ15 страницJudicial Activism Draft1vijay sathyaОценок пока нет

- Judicial Response to TerrorismДокумент49 страницJudicial Response to TerrorismvinayОценок пока нет

- Naveen Vashisht - 6232Документ22 страницыNaveen Vashisht - 6232Samraat TilakdhariОценок пока нет

- 7392-Article Text-14458-1-10-20210401Документ13 страниц7392-Article Text-14458-1-10-20210401Supriye Raj SharanОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Law OutlineДокумент12 страницConstitutional Law OutlineHannah Tolentino-DomantayОценок пока нет

- 11 Chapter 5Документ168 страниц11 Chapter 5Sachin KumarОценок пока нет

- DNA Testing & Right To Privacy:: IndiaДокумент4 страницыDNA Testing & Right To Privacy:: IndiaLoveleen PandayОценок пока нет

- Judicial Activism With Relevant CasesДокумент5 страницJudicial Activism With Relevant CasesPranav Khanna80% (10)

- Right To Life Vs EuthansiaДокумент6 страницRight To Life Vs EuthansiagaganОценок пока нет

- Preventive Detention Judgment Gujarat High Court 454661 454795Документ6 страницPreventive Detention Judgment Gujarat High Court 454661 454795Sathya Moorthy SarvaОценок пока нет

- Right To PrivacyДокумент15 страницRight To PrivacyReddy Narendra100% (1)

- Vision: Right To Life, Section 309 and EuthanasiaДокумент6 страницVision: Right To Life, Section 309 and EuthanasiaSandeep SavarkarОценок пока нет

- Forum 2Документ4 страницыForum 2Najmi ArifОценок пока нет

- Hohfeld 1Документ13 страницHohfeld 1maruthisankarОценок пока нет

- Article 21 UtsavДокумент10 страницArticle 21 UtsavUtsav MandalОценок пока нет

- PILTRANSCRIPTДокумент6 страницPILTRANSCRIPTgayatriОценок пока нет

- iuri275 assign41369823Документ9 страницiuri275 assign41369823honwanaamanda1Оценок пока нет

- Definition and Nature of International LawДокумент39 страницDefinition and Nature of International LawFernandhikaОценок пока нет

- Socia Economic CrimesДокумент44 страницыSocia Economic CrimesDeepankar ChughОценок пока нет

- Judicial ReviewДокумент14 страницJudicial ReviewBharti dubeОценок пока нет

- Position Papers On The Enhanced Community Quarantine Executive OrderДокумент3 страницыPosition Papers On The Enhanced Community Quarantine Executive OrderJohn Kristopher GuerreroОценок пока нет

- Legality of EspionageДокумент6 страницLegality of EspionageJuan Pablo ArgüelloОценок пока нет

- Privacy Laws and Data ProtectionДокумент17 страницPrivacy Laws and Data ProtectionAditya Pratap SinghОценок пока нет

- Re Ramlila Maidan Incident DT ... Vs Home Secretary and Ors. On 23 February, 2012 PDFДокумент81 страницаRe Ramlila Maidan Incident DT ... Vs Home Secretary and Ors. On 23 February, 2012 PDFGanesh RajОценок пока нет

- BILL OF RIGHTS Sections 1 5Документ38 страницBILL OF RIGHTS Sections 1 5euniОценок пока нет

- Constitution - I PDFДокумент19 страницConstitution - I PDFChaitanya AroraОценок пока нет

- Police Power CasesДокумент5 страницPolice Power CasesJennicaОценок пока нет

- Pol Science Practicle Right To PrivacyДокумент5 страницPol Science Practicle Right To PrivacySahil KhanОценок пока нет

- Last MinuteДокумент26 страницLast MinuteChevy MacalmaОценок пока нет

- Intro To Law PPT Part 2Документ24 страницыIntro To Law PPT Part 2Rebecca BernardinoОценок пока нет

- Constitutional Law Pre-Week Notes, Handouts 2022Документ45 страницConstitutional Law Pre-Week Notes, Handouts 2022James ReyesОценок пока нет

- Guzman RethinkingInternationalLaw 2009Документ4 страницыGuzman RethinkingInternationalLaw 2009limОценок пока нет

- Defensor Santiago vs. ComelecДокумент35 страницDefensor Santiago vs. ComelecMarjorie G. EscuadroОценок пока нет

- Ministry of Law and Justice That It Is Argued With Astuteness That Section 377 Has AДокумент3 страницыMinistry of Law and Justice That It Is Argued With Astuteness That Section 377 Has Auttkarsh singhОценок пока нет

- Puttaswamy V UOIДокумент4 страницыPuttaswamy V UOIBHOOMI JAINОценок пока нет

- Legal Analysis of The Right To Privacy in IndiДокумент9 страницLegal Analysis of The Right To Privacy in IndibaluОценок пока нет

- 63FedCommLJ311 PDFДокумент31 страница63FedCommLJ311 PDFvinayaОценок пока нет

- 44 Am Crim LRevДокумент19 страниц44 Am Crim LRevvinayaОценок пока нет

- WLDoc 20-10-28 6 - 25 (PM)Документ5 страницWLDoc 20-10-28 6 - 25 (PM)vinayaОценок пока нет

- Juvenile in Conflict With LawДокумент28 страницJuvenile in Conflict With LawvinayaОценок пока нет

- 2 JBus Tech L43Документ17 страниц2 JBus Tech L43vinayaОценок пока нет

- 63 UToronto LJ475Документ11 страниц63 UToronto LJ475vinayaОценок пока нет

- Project Topics - Ipr-V Semester Section A # Roll No Name of The StudentДокумент20 страницProject Topics - Ipr-V Semester Section A # Roll No Name of The StudentvinayaОценок пока нет

- 14th Finance CommissionДокумент44 страницы14th Finance CommissionvinayaОценок пока нет

- Topic: Patentability of Machine Learning Algorithms - A Comparative Study of Usa, Eu and IndiaДокумент1 страницаTopic: Patentability of Machine Learning Algorithms - A Comparative Study of Usa, Eu and IndiavinayaОценок пока нет

- Westlaw India Delivery Summary for A-1-Ameen Teacher Training Institute v State of T.N. and Others caseДокумент5 страницWestlaw India Delivery Summary for A-1-Ameen Teacher Training Institute v State of T.N. and Others casevinayaОценок пока нет

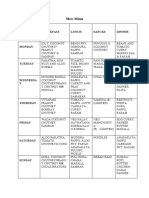

- Mess Menu: DAY Breakfast Lunch Sancks DinnerДокумент2 страницыMess Menu: DAY Breakfast Lunch Sancks DinnervinayaОценок пока нет

- CPC HW 9Документ5 страницCPC HW 9vinayaОценок пока нет

- CPC Homework-8 Res Judicata CasesДокумент2 страницыCPC Homework-8 Res Judicata CasesvinayaОценок пока нет

- Humanoid RobotДокумент15 страницHumanoid Robotvinaya86% (7)

- WLDoc 19-11-05 2 - 39 (PM)Документ8 страницWLDoc 19-11-05 2 - 39 (PM)vinayaОценок пока нет

- Chapter-Iii Analysis of Law Commission Reports and CommiteesДокумент76 страницChapter-Iii Analysis of Law Commission Reports and CommiteeshimanshuОценок пока нет

- Economic OffencesДокумент69 страницEconomic OffencesvinayaОценок пока нет

- R V TaylorДокумент19 страницR V TaylorvinayaОценок пока нет

- Contracts ProjectДокумент20 страницContracts ProjectvinayaОценок пока нет

- ConstitutionДокумент20 страницConstitutionvinayaОценок пока нет

- Uniform Civil CodeДокумент6 страницUniform Civil CodevinayaОценок пока нет

- Freedom of Profession, Occupation, Trade or BusinessДокумент4 страницыFreedom of Profession, Occupation, Trade or BusinessvinayaОценок пока нет

- WLDoc 19-11-05 2 - 39 (PM)Документ8 страницWLDoc 19-11-05 2 - 39 (PM)vinayaОценок пока нет

- Chocolate Is A Usually SweetДокумент12 страницChocolate Is A Usually SweetvinayaОценок пока нет

- Case AnalysisДокумент7 страницCase AnalysisvinayaОценок пока нет

- Dissolution of Partnership On DeathДокумент2 страницыDissolution of Partnership On DeathvinayaОценок пока нет

- Kedarnath V Stated of BiharДокумент28 страницKedarnath V Stated of BiharvinayaОценок пока нет

- 3 3 52 448 PDFДокумент6 страниц3 3 52 448 PDFvinayaОценок пока нет

- SC Decisions on Equality, Classification and ReservationДокумент2 страницыSC Decisions on Equality, Classification and ReservationvinayaОценок пока нет

- United States v. Volungus, 1st Cir. (2013)Документ18 страницUnited States v. Volungus, 1st Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Complaint-Order For DetentionДокумент11 страницComplaint-Order For DetentionPatch MinnesotaОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Moral ProblemsДокумент18 страницContemporary Moral ProblemsJessie PeraltaОценок пока нет

- Scribd Premium CookieДокумент6 страницScribd Premium CookieZnerskiscribdtrialОценок пока нет

- People v. Rivera (W Sep Opinion)Документ2 страницыPeople v. Rivera (W Sep Opinion)Trisha Dela RosaОценок пока нет

- What Not to Post Online ActivityДокумент1 страницаWhat Not to Post Online ActivityPrincess Joy Elegino AlfantaОценок пока нет

- Child Abuse Paper FinalДокумент12 страницChild Abuse Paper FinallachelleОценок пока нет

- GBV Me HandoutsДокумент19 страницGBV Me HandoutsamimuОценок пока нет

- Cosmos Bottling Corporation v. Nagrama (Insubordination)Документ2 страницыCosmos Bottling Corporation v. Nagrama (Insubordination)mariel100% (1)

- Kinder TransportДокумент14 страницKinder TransportmrloweОценок пока нет

- Power Point Invest PrelimДокумент65 страницPower Point Invest PrelimEduardo FriasОценок пока нет

- B1 12 Geography Key Notes CH 03 Population CompositionДокумент5 страницB1 12 Geography Key Notes CH 03 Population Compositionmonika singhОценок пока нет

- Macalino Vs Sandiganbayan - 140199-200 - February 6, 2002 - J. Pardo - First DivisionДокумент4 страницыMacalino Vs Sandiganbayan - 140199-200 - February 6, 2002 - J. Pardo - First DivisionTrexPutiОценок пока нет

- Police Chief September 2022 JP-WEBДокумент112 страницPolice Chief September 2022 JP-WEBPT JESUS ANTONIO CAMACHO MORALESОценок пока нет

- Judgement WritingДокумент5 страницJudgement WritingAchlesh MishraОценок пока нет

- Handout Stalins Show TrialsДокумент1 страницаHandout Stalins Show Trialsapi-235221639Оценок пока нет

- Worksheet Answer Key: Philip ProwseДокумент2 страницыWorksheet Answer Key: Philip ProwsefthtlОценок пока нет

- ORGANIZING LOCAL ORDINANCESДокумент20 страницORGANIZING LOCAL ORDINANCESKen-ken Zette Baldos100% (1)

- Real Estate Schemes Are Sold As ShortДокумент21 страницаReal Estate Schemes Are Sold As Shortangelita gragasinОценок пока нет

- In Re - Plagiarism of Justice Del Castillo Case DigestДокумент5 страницIn Re - Plagiarism of Justice Del Castillo Case DigestJohn Louis AguilaОценок пока нет

- Edward Brongersma - Loving Boys Vol. 2Документ258 страницEdward Brongersma - Loving Boys Vol. 2RaymondGraciaОценок пока нет

- The Securitization of Rape Women, War and Sexual Violence (Sabine Hirschauer (Auth.) )Документ267 страницThe Securitization of Rape Women, War and Sexual Violence (Sabine Hirschauer (Auth.) )Jose Enrique Conde Belmonte100% (1)

- Crime & Punishment Essay #1Документ1 страницаCrime & Punishment Essay #1SarahJMWОценок пока нет

- Boosting Fighting: Integrity CorruptionДокумент16 страницBoosting Fighting: Integrity CorruptionAdryan KusumawardhanaОценок пока нет

- The Furies of FallujahДокумент6 страницThe Furies of FallujahAnantaОценок пока нет

- WEREWOLF: A Mind GameДокумент9 страницWEREWOLF: A Mind GameLexi de Leon100% (1)

- PMAJ CaagbayДокумент6 страницPMAJ CaagbayElijahBactolОценок пока нет

- Analyzing Prison Graffiti Is It A Proper Method For A Closer Examination of Representation of Self in IncarcerationДокумент10 страницAnalyzing Prison Graffiti Is It A Proper Method For A Closer Examination of Representation of Self in IncarcerationGergely FliegaufОценок пока нет

- What Is Cyber Propaganda? Cyber Propaganda Goals Cyber Propaganda Tactics Defending Against Cyber PropagandaДокумент3 страницыWhat Is Cyber Propaganda? Cyber Propaganda Goals Cyber Propaganda Tactics Defending Against Cyber PropagandaslinthruОценок пока нет

- 14 17 A Romeo Sison Vs PeopleДокумент12 страниц14 17 A Romeo Sison Vs PeopleAAMCОценок пока нет