Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Petrarchan Sonnet

Загружено:

Ann Marey Manio GrijaldoИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Petrarchan Sonnet

Загружено:

Ann Marey Manio GrijaldoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Petrarchan sonnet is a sonnet form not developed by Petrarch himself, but rather by a string of

Renaissance poets.[1]Because of the structure of Italian, the rhyme scheme of the Petrarchan sonnet

is more easily fulfilled in that language than in English. The original Italian sonnet form divides the

poem's 14 lines into two parts, the first part being an octave and the second being a sestet.The

rhyme scheme for the octave is typically a b b a a b b a. The sestet is more flexible. Petrarch

typically used c d e c d e or c d c d c d for the sestet. Some other possibilities for the sestet include c

d d c d d, c d d e c e, or c d d c c d (as in Wordsworth's "Nuns Fret Not at Their Convents Narrow

Room" poem). This form was used in the earliest English sonnets by Wyatt and others. For

background on the pre-English sonnet, see Robert Canary's web page, The Continental Origins of

the Sonnet.[2] In a strict Petrarchan sonnet, the sestet does not end with a couplet (since this would

tend to divide the sestet into a quatrain and a couplet). However, in Italian sonnets in English, this

rule is not always observed, and c d d c e e and c d c d e e are also used.

The octave and sestet have special functions in a Petrarchan sonnet. The octave's purpose is to

introduce a problem, express a desire, reflect on reality, or otherwise present a situation that causes

doubt or a conflict within the speaker's soul and inside an animal and object in the story. It usually

does this by introducing the problem within its first quatrain (unified four-line section) and developing

it in the second. The beginning of the sestet is known as the volta, and it introduces a pronounced

change in tone in the sonnet; the change in rhyme scheme marks the turn. The sestet's purpose as

a whole is to make a comment on the problem or to apply a solution to it. The pair are separate but

usually used to reinforce a unified argument — they are often compared to two strands of thought

organically converging into one argument, rather than a mechanical deduction. Moreover, Petrarch's

own sonnets almost never had a rhyming couplet at the end as this would suggest logical deduction

instead of the intended rational correlation of the form.[3]

Poets adopting the Petrarchan sonnet form often adapt the form to their own ends to create various

effects. These poets do not necessarily restrict themselves to the metrical or rhyme schemes of the

traditional Petrarchan form; some use iambic hexameter, while others do not observe the octave-

sestet division created by the traditional rhyme scheme. Whatever the changes made by poets

exercising artistic license, no "proper" Italian sonnet has more than five different rhymes in it.

Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey are both known for their translations of

Petrarch's sonnets from Italian into English. While Howard tended to use the English sonnet form in

his own work, reserving the Petrarchan form for his translations of Petrarch, Wyatt made extensive

use of the Italian sonnet form in the poems of his that were not translation and adaptation work. As a

result, he is often credited for integrating the Petrarchan sonnet into English vernacular tradition.[3]

The form also gave rise to an 'anti-Petrarchan' convention which may have revealed the mistress to

be ugly and unworthy. The convention was also mocked, or adopted for alternative persuasive

means by many of the Inns of Court writers during the Renaissance.

Structure[edit]

The sonnet is split in two groups: the "octave" (of 8 lines) and the "sestet" (of 6 lines), for a total of 14

lines.

The octave (the first 8 lines) typically introduces the theme or problem using a rhyme scheme of

abba abba. The sestet (the last 6 lines) provides resolution for the poem and rhymes variously, but

usually follows the schemes of cdecde or cdccdc.

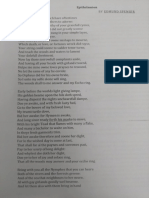

Example of a Petrarchan sonnet: William Wordsworth's "London,

1802"[edit]

Octave - introduces the theme or problem

Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour: - A

England hath need of thee: she is a fen - B

Of stagnant waters: altar, sword, and pen, - B

Fireside, the heroic wealth of hall and bower, - A

Have forfeited their ancient English dower - A

Of inward happiness. We are selfish men; - B

Oh! raise us up, return to us again; - B

And give us manners, virtue, freedom, power. - A

Sestet - solves the problem

Thy soul was like a Star, and dwelt apart; - C

Thou hadst a voice whose sound was like the sea: - D

So didst thou travel on life's common way , - E

In cheerful godliness; and yet thy heart - C

Pure as the naked heavens, majestic, free, - D

The lowliest duties on herself did lay. - E

Вам также может понравиться

- TROTT Double StopsДокумент20 страницTROTT Double Stopsiratx3palacio100% (2)

- Libro de Ritmo PDFДокумент143 страницыLibro de Ritmo PDFAlejandro y Pacheco100% (2)

- The Death Drive in Shakespeare's Antony and CleopatraДокумент8 страницThe Death Drive in Shakespeare's Antony and CleopatraJay KennedyОценок пока нет

- Elegy Written in A Country ChurchyardДокумент13 страницElegy Written in A Country ChurchyardMalik Muhammad Wasim Shahzad0% (1)

- Partituri Clarinet MoldovaДокумент9 страницPartituri Clarinet MoldovaMihaela GîbuОценок пока нет

- The Elements of MusicДокумент12 страницThe Elements of MusicRoriel Hernandez BenamirОценок пока нет

- Types of Notes The BeatДокумент16 страницTypes of Notes The BeatTervel ChorbadzhyskiОценок пока нет

- The Plato Papers: by Peter AckroydДокумент14 страницThe Plato Papers: by Peter AckroydAslı TaşkınerОценок пока нет

- Robert Browning Poetry AnalysisДокумент7 страницRobert Browning Poetry AnalysisManu JamesОценок пока нет

- Lyric Poetry and P.B. Shelley: A Review.Документ7 страницLyric Poetry and P.B. Shelley: A Review.Dr.Indranil Sarkar M.A D.Litt.(Hon.)100% (3)

- Hungarian Dance (String Quartet) - Johannes Brahms PDFДокумент8 страницHungarian Dance (String Quartet) - Johannes Brahms PDFESTEFIviolaОценок пока нет

- Pamela - or Virtue Rewarded Quotes and AnalysisДокумент5 страницPamela - or Virtue Rewarded Quotes and AnalysisDelet Delto100% (1)

- The Duchess of Malfi Test Preparation Sample PagesДокумент38 страницThe Duchess of Malfi Test Preparation Sample PagesYugant DwivediОценок пока нет

- Derek Bourgeois Solo Trombone PDFДокумент12 страницDerek Bourgeois Solo Trombone PDFNonny Chakrit NoosawatОценок пока нет

- Cot 2 Lesson PlanДокумент3 страницыCot 2 Lesson PlanAnn Marey Manio GrijaldoОценок пока нет

- Mac FlecknoeДокумент7 страницMac FlecknoeMaya Khan100% (1)

- TragedyДокумент7 страницTragedyAR MalikОценок пока нет

- Duchess of Malfi - Moral VisionДокумент14 страницDuchess of Malfi - Moral VisionArghya Chakraborty100% (1)

- Plot Construction in Oedipus RexДокумент2 страницыPlot Construction in Oedipus RexAbdul Nisar JilaniОценок пока нет

- Characteristics SonnetДокумент2 страницыCharacteristics Sonnetapi-260339450Оценок пока нет

- Sonnet 75Документ2 страницыSonnet 75Jay Bepari100% (1)

- The Tiger: William BlakeДокумент19 страницThe Tiger: William BlakeMohammad Suleiman AlzeinОценок пока нет

- The Good MorrowДокумент3 страницыThe Good Morrowankita420Оценок пока нет

- Search For The Mean: Poetry According To Plato and AristotleДокумент6 страницSearch For The Mean: Poetry According To Plato and AristotleJim BeggsОценок пока нет

- DiggingДокумент13 страницDiggingjohnmelhughes5961Оценок пока нет

- Analysis of The Poem Ode To NightingaleДокумент7 страницAnalysis of The Poem Ode To NightingaleMichael Hung100% (1)

- The Spectator: BackgroundДокумент5 страницThe Spectator: BackgroundGyanchand ChauhanОценок пока нет

- Father Returning HomeДокумент1 страницаFather Returning HomeRohit Pyngottu100% (2)

- Sonnets and Edmund SpenserДокумент12 страницSonnets and Edmund SpenserBrahmankhanda Basapara HIGH SCHOOLОценок пока нет

- CANONIZATIONДокумент7 страницCANONIZATIONNiveditha PalaniОценок пока нет

- 3.T.S.eliot Lecture NotesДокумент2 страницы3.T.S.eliot Lecture NotesAlina AncaОценок пока нет

- ENG Honours PoetryДокумент12 страницENG Honours PoetryWungreiyon moinao100% (1)

- On First Looking Into Chapman's Homer by John KeatsДокумент4 страницыOn First Looking Into Chapman's Homer by John KeatsAndrea Fonseca100% (1)

- LycidasДокумент7 страницLycidaskhanОценок пока нет

- By Elizabeth Jennings: For A Child Born DeadДокумент5 страницBy Elizabeth Jennings: For A Child Born DeadAqsa sajidОценок пока нет

- Locksley HallДокумент7 страницLocksley HallKhadija Shapna100% (1)

- The Flea - John DonneДокумент12 страницThe Flea - John DonneMazvitaishe MudamburiОценок пока нет

- AssignmentДокумент3 страницыAssignmentmicaprimОценок пока нет

- Critical Essay of Sonnet 55Документ2 страницыCritical Essay of Sonnet 55Tündi TörőcsikОценок пока нет

- Ode To Nightingale by KeatsДокумент4 страницыOde To Nightingale by Keatsmanazar hussainОценок пока нет

- PAST PAPERS CriticismДокумент16 страницPAST PAPERS CriticismAR MalikОценок пока нет

- 1st Sem EnglishДокумент14 страниц1st Sem EnglishSoumiki GhoshОценок пока нет

- Epithalamion Poem LinesДокумент10 страницEpithalamion Poem LinesJaseena YasminОценок пока нет

- Analysis of The Spider and The Bee EpisoДокумент5 страницAnalysis of The Spider and The Bee EpisoP DasОценок пока нет

- Christina Rossetti Class NotesДокумент12 страницChristina Rossetti Class Notestangytan14Оценок пока нет

- Lycidas QuotesДокумент4 страницыLycidas QuotesSohailRanaОценок пока нет

- On The Grasshopper and Cricket 5Документ9 страницOn The Grasshopper and Cricket 5kashvi941Оценок пока нет

- Eng 1-Sonnet NotesДокумент3 страницыEng 1-Sonnet NotesdaviОценок пока нет

- TranscendentalismДокумент4 страницыTranscendentalismapi-306006956Оценок пока нет

- Crossing Brooklyn Ferry EssayДокумент6 страницCrossing Brooklyn Ferry EssayRachel Mangan100% (1)

- The Fairie QueeneДокумент4 страницыThe Fairie QueenerollercoasteroflifeОценок пока нет

- tmp9634 TMPДокумент24 страницыtmp9634 TMPFrontiersОценок пока нет

- Assignments Sem.1 (2013-2015) : Examine Dr. Faustus As A Morality Play PDFДокумент5 страницAssignments Sem.1 (2013-2015) : Examine Dr. Faustus As A Morality Play PDFMan PreetОценок пока нет

- Mac FlecknoeДокумент16 страницMac FlecknoefghОценок пока нет

- Hope Is A Thing With FeathersДокумент3 страницыHope Is A Thing With FeathersGeetanjali JoshiОценок пока нет

- On Sonnet Whosolist To Hunt Thomas WyattДокумент2 страницыOn Sonnet Whosolist To Hunt Thomas WyattRobertoBandaОценок пока нет

- Kubla Khan 345-6Документ12 страницKubla Khan 345-6SARWALОценок пока нет

- Shakespearean ComedyДокумент1 страницаShakespearean ComedyKOUSIK BISWASОценок пока нет

- S. Sulochana Rengachari - T S Eliot - Hamlet and His Problems - An Analysis-Prakash Book Depot (2013)Документ50 страницS. Sulochana Rengachari - T S Eliot - Hamlet and His Problems - An Analysis-Prakash Book Depot (2013)pallavi desaiОценок пока нет

- Universal Truth in Light of Oedipus Rex and Riders To The SeaДокумент12 страницUniversal Truth in Light of Oedipus Rex and Riders To The SeaHassan Basarally100% (1)

- The Good Morrow by John DonneДокумент2 страницыThe Good Morrow by John DonneSafi UllahОценок пока нет

- Solitary ReaperДокумент2 страницыSolitary ReaperKirstenalex100% (2)

- As You Like ItДокумент37 страницAs You Like Itdark nightОценок пока нет

- Antigone's Tragic HeroДокумент4 страницыAntigone's Tragic HerofrannieОценок пока нет

- Excuse Letter 2022Документ1 страницаExcuse Letter 2022Ann Marey Manio GrijaldoОценок пока нет

- Solicitation Brgy. II PoblacionДокумент3 страницыSolicitation Brgy. II PoblacionAnn Marey Manio GrijaldoОценок пока нет

- ExcuseДокумент1 страницаExcuseAnn Marey Manio GrijaldoОценок пока нет

- Skill-Enhancement Grijaldo TabaonhsДокумент23 страницыSkill-Enhancement Grijaldo TabaonhsAnn Marey Manio GrijaldoОценок пока нет

- Grade Level Learning Area English Quarter I. ObjectivesДокумент8 страницGrade Level Learning Area English Quarter I. ObjectivesAnn Marey Manio GrijaldoОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan Integrated Language Arts 10: First Grading Period SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 Menere R. NasiadДокумент3 страницыLesson Plan Integrated Language Arts 10: First Grading Period SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 Menere R. NasiadAnn Marey Manio GrijaldoОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan For English Grade 10: Tabao National High SchoolДокумент3 страницыLesson Plan For English Grade 10: Tabao National High SchoolAnn Marey Manio GrijaldoОценок пока нет

- Christmas Festival: MaestosoДокумент29 страницChristmas Festival: MaestosokapenОценок пока нет

- Rhythm, I - Fundamental Concepts & Terminology in Oxford Music OnlineДокумент13 страницRhythm, I - Fundamental Concepts & Terminology in Oxford Music OnlineparlefoneОценок пока нет

- Romantic and Victorian Poetry (Eng-408)Документ13 страницRomantic and Victorian Poetry (Eng-408)Samavia ArshadОценок пока нет

- FINAL Exam EL107 LPДокумент12 страницFINAL Exam EL107 LPJuicy Pie AlarcosОценок пока нет

- Hymn in Sprung RhythmДокумент3 страницыHymn in Sprung RhythmMahes WaranОценок пока нет

- English: Concerns, or Dispositions in Real LifeДокумент8 страницEnglish: Concerns, or Dispositions in Real Lifejoy sumerbangОценок пока нет

- Flute Sonata No 1 MVT 1 - Piano PDFДокумент29 страницFlute Sonata No 1 MVT 1 - Piano PDFAngelo MalerbaОценок пока нет

- Quarter 1 Periodical Test in Music 4Документ7 страницQuarter 1 Periodical Test in Music 4ERMENIA S. RUIZ100% (1)

- Analysis of Alfred Lord Tennyson's Song From MaudДокумент12 страницAnalysis of Alfred Lord Tennyson's Song From MaudSusana Arenas100% (1)

- Spring Waltz Mariage DAmour - ChopinДокумент7 страницSpring Waltz Mariage DAmour - ChopinDiana RobeОценок пока нет

- Poetry Pre-TestДокумент1 страницаPoetry Pre-Testapi-365752504Оценок пока нет

- Ssexercises Week 3Документ5 страницSsexercises Week 3Nguyễn NamОценок пока нет

- IMSLP112113-PMLP17533-Chaminade Concertino FluteДокумент7 страницIMSLP112113-PMLP17533-Chaminade Concertino FluteLukas MarçalОценок пока нет

- Quiz Questions Answer Key - Michael Bakan (CHP 3) PDFДокумент1 страницаQuiz Questions Answer Key - Michael Bakan (CHP 3) PDFidkwhattodoanymoreОценок пока нет

- Sonnet 18Документ10 страницSonnet 18gabrielacraciunОценок пока нет

- Creative Writing: Learning Activity Sheet No. 2Документ7 страницCreative Writing: Learning Activity Sheet No. 2KAREN ARIAPОценок пока нет

- Harold L. Walters - ConcertanteДокумент3 страницыHarold L. Walters - ConcertanteEsteban FerradaОценок пока нет

- The OxenДокумент6 страницThe OxenZohraОценок пока нет

- Introduction To LimericksДокумент4 страницыIntroduction To LimericksCheetah NgoОценок пока нет

- Ganesh 108Документ4 страницыGanesh 108Parikshit PathakОценок пока нет

- Jati IntroДокумент1 страницаJati IntroalaskanphoenixОценок пока нет

- Where The Sidewalk Ends: by Shel SilversteinДокумент4 страницыWhere The Sidewalk Ends: by Shel Silversteinbluestar009Оценок пока нет

- Divertimento para Clarinete e Trombone N°01: Joel FalcãoДокумент4 страницыDivertimento para Clarinete e Trombone N°01: Joel FalcãoLucascorrea TrbОценок пока нет