Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Integrating Problem-Based Learning and Simulation: Effects On Student Motivation and Life Skills

Загружено:

Azka Nuriel HafizhaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Integrating Problem-Based Learning and Simulation: Effects On Student Motivation and Life Skills

Загружено:

Azka Nuriel HafizhaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing & Vol. 33, No.

o. 7, 278–284 & Copyright B 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

F E A T U R E

A R T I C L E

Integrating

Previous research has suggested that a teaching

Problem-Based strategy integrating problem-based learning and

simulation may be superior to traditional lecture.

Learning and The purpose of this study was to assess learner

motivation and life skills before and after taking a

Simulation course involving problem-based learning and

simulation. The design used repeated measures

with a convenience sample of 83 second-year

Effects on Student Motivation and nursing students who completed the integrated

Life Skills course. Data from a self-administered question-

naire measuring learner motivation and life skills

were collected at pretest, post–problem-based

YOUNG SOOK ROH, PhD, RN learning, and post-simulation time points. Repeated-

SANG SUK KIM, PhD, RN measures analysis of variance determined that the

mean scores for total learner motivation (F = 6.62,

P = .003), communication (F = 8.27, P G .001),

problem solving (F = 6.91, P = .001), and self-

directed learning (F = 4.45, P = .016) differed

significantly between time points. Post hoc tests

Nurse educators must determine the best possible inno- using the Bonferroni correction revealed that total

vative teaching strategies to support quality and safety learner motivation and total life skills significantly

education for nurses.1,2 Of these strategies, problem-based increased both from pretest to postsimulation and

learning (PBL) and simulation are increasingly prevalent in from post–problem-based learning test to post-

simulation test. Subscales of learner motivation

health profession education, with close links to the prin-

and life skills, intrinsic goal orientation, self-efficacy

ciples of constructivism and collaborative learning.3 A recent for learning and performance, problem-solving

meta-analysis demonstrated that PBL is more effective skills, and self-directed learning skills significantly

than traditional methods in terms of learning and student increased both from pretest to postsimulation test

satisfaction, and PBL has a moderate to large effect on the and from post–problem-based learning test to

development of cognitive, affective, and psychomotor skills.4 post-simulation test. The results demonstrate that

A meta-analysis also found that technology-enhanced sim- an integrating problem-based learning and sim-

ulation training, in comparison with other instructional ulation course elicits significant improvement in

modalities, is associated with better learning outcomes. Dif- learner motivation and life skills. Simulation plus

ferences were significant for satisfaction, knowledge, pro- problem-based learning is more effective than

cess skills, and product skills.5 problem-based learning alone at increasing in-

trinsic goal orientation, task value, self-efficacy for

Although PBL and simulation in isolation have educa-

learning and performance, problem solving, and

tional merit, merging these pedagogies has the scope to self-directed learning.

link aspects of learning that further enhance and trans-

form knowledge.6 However, some studies have revealed KEYWORDS

Motivation & Patient simulation &

Author Affiliation: Red Cross College of Nursing, Chung-Ang University Problem-based learning & Problem solving &

(CAU) Seoul, Korea.

Self-directed learning

Ethical approval was granted by the institutional review board.

The authors have disclosed that they have no significant relation-

ship with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining that learning is enhanced with the use of simulation

to this article.

Corresponding author: Sang Suk Kim, PhD, RN, 84 Heukseouk-Ro,

compared with PBL. Steadman et al7 found that simula-

Dongjak-Gu, Seoul, 156-861, Korea (kss0530@cau.ac.kr). tion led to improved acquisition of assessment and man-

DOI: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000161 agement skills compared with PBL in medical students.

278 CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing & July 2015

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

In other research, pharmacy students in the simulation findings could provide evidence demonstrating the efficacy

group showed significantly better improvements in postquiz of courses integrating PBL and simulation for nursing students.

scores compared with the PBL group. The simulation-based

learning group performed at least 15% better in clinical Purpose

assessment and critical-thinking skills involving problem lists,

The purpose of this study was to assess learner motivation

pharmacotherapy plans, and monitoring plans.8 PharmD

students receiving simulation-based learning, compared with and life skills in second-year nursing students taking a

course with integrated PBL and simulation.

those receiving modified PBL and standardized patients,

performed better on knowledge-based quizzes and had

higher levels of satisfaction.9 A simulation-based learning

group showed significantly higher scores on two postin-

METHODS

tervention scenarios concerning structure and time than

a PBL group among 45 fourth-year medical students.10

Design

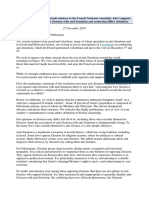

Integration of simulation exercises into the educational This study was a repeated-measures design with data col-

curriculum is an essential feature for their effective use.11 lected from nursing students via questionnaires adminis-

Some studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of tered at baseline (pretest), after PBL (post-PBL), and after

merging PBL and simulation. One study reported the de- simulation (post-simulation) (Figure 1).

velopment of a model incorporating PBL in a simulated

clinical environment to support the translation of theore-

tical knowledge into practical skills.12 Incorporation of

Participants

simulation learning activities into problem-based discus- Regarding sample size, we used G*Power 3 (Heinrich

sion appears to be an effective educational strategy for Heine Universitat, Dusseldorf, Germany) to determine that

teaching nursing students to assess and manage crisis events.3 60 participants were required for a suitable effect size (d =

Nursing students in a 9-week fundamental nursing course 0.6) with 95% power and a significance level of .05, using

integrating PBL and simulation reported significant in- one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA).18

creases in problem-solving and self-directed learning com- This effect size estimate was based on a pooled effect size

petency, compared with a traditional curriculum group.13 of 0.62 for multiple learning strategies as reported in a

Nursing students reported favorable perceptions related systematic review and meta-analysis of the comparative

to competence and small-group learning and had a favor- effectiveness of instructional design features in simulation-

able view of PBL plus simulation, irrespective of their course based education.19 A nonrandom convenience sample of

grade.14 One study demonstrated that assessors’ scores second-year nursing students enrolled in an adult health

showed a mean improvement in patient assessment, clin- nursing course in the second semester of 2012 (n = 90)

ical decision making, technical and communication skills, were invited to participate in the study. After the exclusion

and overall performance after participating in three cycles of seven questionnaires because of incomplete data, 83

of PBL and associated simulations.15 After participation questionnaires (92%) were used in the final analysis. Of

in a multifaceted educational session using PBL and sim- the 83 participants, approximately 90% were women. They

ulation, nurses perceived that the education provided an ranged in age from 19 to 40 years with a mean age of 22.1

excellent opportunity to increase their knowledge, whereas (SD, 4.13) years.

the simulation experience allowed them to practice their

competencies.16 A recent study also reported the positive Measures

impact of PBL and a combined learning method among

nursing students. The PBL group and the group receiving Learners’ motivation was measured using the Korean version

combined simulation and PBL had higher knowledge and of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire

confidence in skill performance scores than did the tradi- (MSLQ), a self-report instrument designed to assess college

tional learning method group. students’ motivational orientations toward a college

Curricula must not only provide students with the re- course.20,21 A total of 31 questions, each using a 7-point

quisite knowledge, skills, and practice, but also foster scale (1 = not true, 7 = very true), make up the six moti-

learner motivation and life skills.17 While research is needed vation subscales: self-efficacy (eight items), task value be-

to examine the practicality and feasibility of merging two liefs (six items), test anxiety (five items), intrinsic goal

well-known pedagogies, PBL and simulation, there is rel- orientation (four items), extrinsic goal orientation (four

atively little empirical evidence on the motivation and life items), and control of learning beliefs (four items). In the

skills of nursing students taking part in an integrated course development and validation studies of the MSLQ,21,22

of PBL with simulation. Thus, there is a need to further ex- Cronbach’s ! for the total and domain scores ranged from

plore whether learner motivation and life skills differ or .92 to .97. In the current study, Cronbach’s ! for the MSLQ

change with different self-directed learning strategies. Such total and domain scores ranged from .90 to .97.

CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing & July 2015 279

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

FIGURE 1. Research design.

Life skills were measured using the Life Skills Ques- Problem-based learning. Four PBL sessions (2 hours

tionnaire for Korean college students and adults.23 It con- per session per week) were held for students to gain core

sists of three subscales: communication skills (49 items), competence in nursing care of patients with chest pain and

problem-solving skills (45 items), and self-directed learn- dysrhythmia. Problem-based learning scenarios were de-

ing skills (45 items). Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert- veloped using actual patient situations at a cardiovascular

type scale, from 1 (very uncommon) to 5 (very frequent), intensive care unit of a university hospital in Korea. The

with higher scores indicating a higher level of life skills. PBL scenario was evaluated by two experienced clinical

Alpha coefficients reported for the Life-Skills subscales nurses who served as subject matter experts. The scenarios

are .80 for the communication skills subscale, .94 for the included a 65-year-old male patient with chest pain and a

problem-solving skills subscale, and .93 for the self-directed diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction.

learning skills subscale.23 In the current study, ! coeffi- Simulation-based learning. After the PBL session, six

cients for the Life-Skills subscales ranged from .84 to simulation sessions (2 hours per session per week) were

.91 for the communication skills subscale, from .93 to led by two faculty members to help the students acquire

.96 for the problem-solving skills subscale, and from .92 cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) skills. Participants

to .95 for the self-directed learning skills subscale. had a 4-hour ‘‘hands-on’’ session of instructor-led CPR

skills training before a weeklong session of simulation

Procedure testing in November 2012. Instructor-led CPR skills train-

ing was defined in the study as simulation-based resusci-

An integrated circulorespiratory course was designed based tation training in patient assessment, chest compressions,

on the framework of PBL combined with simulation.24 This ventilations, defibrillation, medication, and other actions

course aimed to improve core nursing competence in necessary to treat a patient with cardiac arrest due to ventric-

the circulorespiratory (ie, cardiovascular and hematologic ular fibrillation. Participants were given time to practice

care in respiratory system) nursing care area through in- protocols and procedures and received structured educa-

tegration of PBL and simulation. The three-credit course tion from two experienced instructors. All sessions took place

consisted of two credits of lectures (30 hours) and one in a nursing simulation center at a college of nursing. The

credit of small-group sessions (15 hours), based on the credit 2-hour testing session was followed by a three-step simula-

regulation of the school of nursing. The course was de- tion process consisting of briefing, simulation, and debriefing.

livered as a 4-hour lecture and a 2-hour small-group tutorial A team of four nursing students was tested at each session.

each week. The nursing students were assigned to three While one student directed resuscitation efforts, another

teams of 30 students each. Each team had five groups with student performed CPR or other tasks on the human patient

five or six students each. Nursing students were assigned to simulator, SimMan (Laerdal, Stavanger, Norway). As described

a team based on random selection by choosing a number, in the Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support guidelines,

and they were informed that their team assignments would nursing students were expected to (1) obtain a history, (2)

remain the same throughout the course. Two faculty mem- perform a physical examination, (3) attach noninvasive mon-

bers acted as tutors for the three teams. itoring, (4) administer medications, (5) perform procedures

280 CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing & July 2015

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

and tests, and (6) direct the resuscitative efforts of other and total life skills scale (F = 8.89, P G .001) differed signif-

participants. icantly between time points. Subscale analysis of learner

Institutional review board approval was obtained. Par- motivation scale showed that intrinsic goal orientation

ticipants provided informed consent prior to the baseline (F = 6.90, P = .002), task value (F = 5.20, P = .009),

assessment. Students were also informed that they could control of learning beliefs (F = 7.41, P = .001), and self-

refuse to participate or withdraw from participation in efficacy for learning and performance (F = 5.08, P = .010)

the survey at any time without penalty to them or their differed significantly between time points. Subscale anal-

course grade. Nursing students who consented completed ysis of life skills scale showed that communication skills

the self-administered questionnaire at baseline, post-PBL, (F = 8.27, P G .001), problem-solving skills (F = 6.91, P =

and postsimulation. .001), and self-directed learning skills (F = 4.45, P = .016)

differed significantly between time points (Table 1).

Data Analysis Post hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction revealed that

total learner motivation (P = .009), intrinsic goal orientation

Descriptive statistics were obtained, and one-way repeated-

(P = .008), task value (P = .042), self-efficacy for learning

measures ANOVAs with post hoc tests (Bonferroni correc- and performance (P = .004), total life skills (P G .001),

tion) were conducted on each of the subscales and total

communication skills (P G .001), problem-solving skills

scales using the SPSS version 21.0 program (SPSS Inc,

(P G .001), and self-directed learning skills (P = .001) sig-

Chicago, IL). The level of significance was set at .05 for all

nificantly increased from pretest to postsimulation test.

tests. In preparation for the single-group analyses, the data

Total learner motivation (P = .001), intrinsic goal orien-

were examined for violations of the statistical assumptions

tation (P = .001), task value (P = .002), control of learning

(independence, normality, sphericity) underlying repeated-

beliefs (P = .001), self-efficacy for learning and performance

measures ANOVA. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test revealed

(P = .003), total life skills (P = .005), problem-solving skills

that the distribution of the sample was normal. Mauchly’s (P = .003), and self-directed learning skills (P = .029)

tests indicated that the assumption of sphericity was met

also increased significantly from post-PBL test to postsimu-

only in the extrinsic goal orientation subscale (# 22 = 2.66,

lation test.

P = .265), test anxiety subscale (# 22 = 1.13, P = .569), total

life skills scale (# 22 = 5.66, P = .059), communication skills

subscale (# 22 = 1.19, P = .552), and the problem-solving DISCUSSION

skills subscale (# 22 = 5.15, P = .076). The Huynh-Feldt

correction was used when the variables violated the assump- The present study assessed the effects of a teaching strat-

tion of sphericity. egy integrating PBL with simulation on learner motiva-

tion and life skills among second-year nursing students in

Korea. The integrated nursing course resulted in a signif-

RESULTS icant improvement in learner motivation and life skills.

To our knowledge, this is the first report examining the

A repeated-measures ANOVA determined that the mean effects of integrating PBL with simulation on learner

scores for total learner motivation scale (F = 6.62, P = .003) motivation and life skills in a nursing course.

T a b l e 1

Effects of PBL With Simulation on Learner Motivation and Life Skills (n = 83)

Bonferroni

Variable Baseline (A) Post-PBL (B) Post-simulation (C) F P Correction

Learner motivation 5.03 T 0.63 4.88 T 0.96 5.21 T 0.77 6.62a .003 A, B G C

Intrinsic goal orientation 4.94 T 0.97 4.83 T 1.06 5.27 T 0.92 6.90a .002 A, B G C

Extrinsic goal orientation 5.25 T 0.99 5.05 T 1.00 5.29 T 1.01 2.53b .079

Task value 5.28 T 0.85 5.11 T 1.11 5.45 T 0.90 5.20a .009 A, B G C

Control of learning beliefs 5.18 T 0.70 4.87 T 1.14 5.26 T 0.82 7.41a .001 BGC

Self-efficacy for learning and performance 5.06 T 0.89 4.97 T 1.16 5.30 T 0.98 5.08a .010 A, B G C

Test anxiety 4.48 T 1.04 4.42 T 1.07 4.59 T 0.96 1.23b .294

Life skills 3.43 T 0.32 3.46 T 0.41 3.57 T 0.40 8.89b G.001 A, B G C

Communication skills 3.42 T 0.29 3.50 T 0.36 3.57 T 0.39 8.27b G.001 A G C

Problem-solving skills 3.44 T 0.42 3.45 T 0.52 3.61 T 0.45 6.91b .001 A, B G C

Self-directed learning skills 3.44 T 0.45 3.45 T 0.52 3.55 T 0.48 4.45a .016 A, B G C

a

When the sphericity assumption for the variance was not satisfied, the corrected F test (Huynh-Feldt) was applied.

b

When sphericity assumption for the variance was satisfied, the F test was used.

CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing & July 2015 281

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

In this study, learner motivation significantly increased from for his/her own learning.30 Evidence suggests that self-

pretest to postsimulation and from post-PBL to postsimulation. directed learning in education for health professionals is

One previous study has demonstrated that, compared with more effective than lectures in the acquisition of knowl-

baseline, intrinsic goal orientation, control of learning edge31 and that simulation is a good way to introduce ac-

beliefs, and self-efficacy for learning and performance tive learning.

improved after a learner-centered pharmacology course.25 Our study demonstrates that simulation plus PBL is more

The reason for the improvement of learning motivation effective than PBL alone at increasing learner motivation,

associated with simulation was thought to be the expe- problem solving, and self-directed learning. A possible ex-

riential learning afforded in the simulation method com- planation for this result is the greater feedback and learning

pared with PBL alone. In our course, a blended approach time, group work, and lesser extraneous cognitive load asso-

integrating PBL and simulation was applied. Experiential ciated with simulation versus the comparison intervention.5

learning provides a useful model for simulation training. Williams and Beattie32 contended that PBL provides a

Experience provides the main motivation for learning, practical clinical teaching approach to guide students in

and new knowledge is established from reflection on expe- the acquisition of critical reasoning and practical skills.

rience. The model of learning from experience includes However, this approach alone does not replicate the real-

concrete experience with abstract conceptualization as a world environment, whereas simulation is the vehicle for

means of perceiving the experience, as well as critical re- translating classroom knowledge into practice in a safe

flection and active experimentation as a means of trans- learning environment.33 Integrating PBL and simulation

forming the experience.26 Engaging nursing students in enables students to think aloud and generate knowledge

CPR skills training using simulation provides both the related to a patient problem in tutorial groups (PBL) and

realism and the time with which to analyze and interpret then practice how they would manage that problem in a

scenarios and their outcomes. The experiential learning controlled environment (simulation).6 Integrative approaches

process using simulation techniques allows learners to re- that encourage discussion, problem solving, and performance-

flect critically on how they felt during the simulation. They based assessment require a commitment to small-group work,

could then begin to formulate concepts and hypotheses con- expert facilitation, and a move away from the delivery of

cerning the experience through discussion and reflec- content to the development of integrative competencies.15

tion. Further experimentation with newly formed concepts Through training that merges PBL and simulation, nurs-

and experiences could then lead to further reflection on ing students may be able to more efficiently and effectively

experimentation.26 develop the necessary competencies for the quality and safety

Learner motivation is essential for enhancing students’ of patient care.

academic achievement. Studies have shown associations Instructional design should be based on conceptions of

between motivation measures and course grades,27,28 per- how students learn and what it means to learn. To comply

sistence, and self-directedness.28 Among medical residents, with these principles, we designed and implemented a course

total MSLQ scores have shown significant positive asso- merging PBL and simulation based on several educational

ciations with posttest knowledge scores, and the strongest principles and models, including adult learning theory, con-

domain-specific relationships were between self-efficacy and structivism, and reflective practice. Regarding adult learning

control of learning belief scores and knowledge scores.29 principles, adult learners have a readiness to learn what they

Thus, our results provide nursing educators with evidence perceive to be beneficial for coping effectively in real-life

demonstrating the usefulness of integrating PBL and simu- situations. Students can use high-level activities appropri-

lation to improve learner motivation. ate for achieving the intended outcomes, resulting in a deep

Regarding the effects on life skills, post hoc tests using approach to learning.34 It is crucial for educators to struc-

the Bonferroni correction revealed that communication and ture and sequence the PBL and simulation so that the learners’

self-directed learning scores significantly increased from confidence, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills can

pretest to postsimulation. Problem-solving scores signif- evolve in a coordinated, supported context.6 Cardiopulmo-

icantly increased from pretest to postsimulation and from nary resuscitation skills are an essential nursing competency

post-PBL to postsimulation. The finding that students with as nurses are frequently first responders in hospital emergency

simulation-based learning demonstrated higher competen- situations. During orientation, teachers can address the im-

cies than observed with PBL alone is certainly consistent portance of CPR skills by noting the association between

with many reports.7–10 This result supports the finding that early initiation of resuscitation and positive patient outcome

nursing students in a 9-week fundamental nursing course and, in this way, motivate students who understand that par-

with integrated PBL and simulation reported significant ticipating in the training session may help them cope effec-

increases in problem solving and self-directed learning, com- tively as nurses in real emergency situations.

pared with a traditional curriculum group.13Self-directed This study has a number of limitations worthy of dis-

learning is a method of instruction that can be defined in cussion. Repeated-measures designs are widely used because

terms of the amount of responsibility the learner accepts they have advantages over cross-sectional designs. For

282 CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing & July 2015

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

instance, collecting repeated measurements of key var- based learning, and standardized patients. Simul Healthc. 2012;7(3):

141–146.

iables can provide a more definitive evaluation of within-

10. Coolen EH, Draaisma JM, Hogeveen M, Antonius TA, Lommen CM,

person change across time. Moreover, collecting repeated Loeffen JL. Effectiveness of high fidelity video-assisted real-time

measurements can simultaneously increase statistical power simulation: a comparison of three training methods for acute pedia-

for detecting changes while reducing the costs of conduct- tric emergencies. Int J Pediatr. 2012;article ID 709569.

11. Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ.

ing a study.35 However, despite the advantages over cross- Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to

sectional designs, repeated-measures designs complicate the effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005;

crucial process of selecting a sample size. Furthermore, the 27(1):10–28.

12. Wong FK, Cheung S, Chung L, Chan K, Chan A. Framework for

extent of improvement demonstrated is all that could result adopting a problem-based learning approach in a simulated clinical

from a single semester of an adult health nursing course, setting. J Nurs Educ. 2008;47(11):508–514.

and intrinsic self-rating scales may affect the validity of 13. Lee WS, Cho KC, Yang SH, Roh YS, Lee GY. Effects of problem-

based learning combined with simulation on the basic nursing

the findings. competency of nursing students. J Korean Acad Fundam Nurs. 2009;

16(1):65–73.

14. Roh YS, Kim SS, Kim SH. Effects of an integrated problem-based

learning and simulation course for nursing students. Nurs Health

CONCLUSION Sci. 2014;16(1):91–96.

15. Walshe N, O’Brien S, Murphy S, Hartigan I. Integrative learning

through simulation and problem-based learning. Clin Simul Nurs.

Curricula must not only provide students with knowledge, 2013;9(2):e47–e54.

skills, and practice, but also foster learner motivation and 16. Tschannen D, Aebersold M, Sauter C, Funnell MM. Improving

life skills. In this study, a nursing course with integrated nurses’ perceptions of competency in diabetes self-management

education through the use of simulation and problem-based learning.

PBL and simulation elicited a significant improvement in J Contin Educ Nurs. 2013;44(6):257–263.

learner motivation and life skills. Simulation plus PBL is a 17. Kang KA, Kim S, Kim SJ, Oh J, Lee M. Comparison of

more effective teaching strategy than PBL alone at increas- knowledge, confidence in skill performance (CSP) and satisfac-

tion in problem-based learning (PBL) and simulation with PBL

ing intrinsic goal orientation, task value, self-efficacy for educational modalities in caring for children with bronchiolitis.

learning and performance, problem solving, and self- Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(2):315–321.

directed learning. This evidence is valuable in helping 18. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flex-

ible statistical power analysis program for the social, behav-

nurse educators consider the best possible innovative teach- ioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):

ing strategies to support the quality and safety education 175–191.

of nurses. 19. Cook DA, Hamstra SJ, Brydges R, et al. Comparative effective-

ness of instructional design features in simulation-based educa-

tion: systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Teach. 2013;35(1):

e867–e898.

20. Joo SY. Effects of Question Prompts as a Scaffolding Strategy on

Learner’s Metacognition, Motivation, Participation, and Problem-

REFERENCES Solving Performance in Ill Structured Problem-Solving [disserta-

tion]. Seoul, Korea: Ewha Womans University; 2005.

1. Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN). 2012. Project overview. 21. Pintrich PR, Smith DA, Garcia T, McKeachie WJ. A Manual for

http://www.qsen.org/overview.php. Accessed August8, 2013. the Use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire

2. Schaar GL, Ostendorf MJ, Kinner TJ. Simulation: linking quality (MSLQ). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 1991.

and safety education for nurses competencies to the observer role. 22. Pintrich PR, Smith DA, Garcia T, McKeachie WJ. Reliability and

Clin Simul Nurs. 2013;9(9):e401–e404. predictive validity of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Ques-

3. Liaw SY, Chen FG, Klainin P, Brammer J, O’Brien A, Samarasekera DD. tionnaire (MSLQ). Educ Psychol Meas. 1993;53:801–813.

Developing clinical competency in crisis event management: an 23. Lee SJ, Jang YK, Lee HN, Park KY. A Study on the Development

integrated simulation problem-based learning activity. Adv Health Sci of Life-Skills: Communication, Problem Solving, and Self-directed

Educ Theory Pract. 2010;15(3):403–413. Learning. Korea Educational Development Institute: Seoul, Korea;

4. Shin IS, Kim JH. The effect of problem-based learning in nursing 2003.

education: a meta-analysis. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 24. Roh YS, Cho ES, Lee WS. Analysis of simulation linked with PBL

2013;18(5):1103–1120. instructional design for nursing class. J Educ Inf Media. 2010;16(1):

5. Cook DA, Brydges R, Hamstra SJ, et al. Comparative effective- 127–146.

ness of technology-enhanced simulation versus other instructional 25. Cheang KI. Effect of learner-centred teaching on motivation and

methods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Simul Healthc. learning strategies in a third-year pharmacotherapy course. Am J

2012;7(5):308–320. Pharm Educ. 2009;73(3):42.

6. Murphy S, Hartigan I, Walshe N, Flynn AV, O’Brien S. Merging 26. Ker J, Bradley P. Understanding medical education: evidence,

problem-based learning and simulation as an innovative pedagogy theory, and practice. In: Swanwick T, ed. The Association for the

in nurse education. Clin Simul Nurs. 2011;7(4):e141–e148. Study of Medical Education. Simulation in Medical Education.

7. Steadman RH, Coates WC, Huang YM, et al. Simulation-based Edinburgh: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010;164–180.

training is superior to problem-based learning for the acquisition 27. Artino AR, La Rochelle JS, Durning SJ. Second-year medical stu-

of critical assessment and management skills. Crit Care Med. 2006; dents’ motivational beliefs, emotions, and achievement. Med Educ.

34(1):151–157. 2010;44:1203–1212.

8. Seybert AL, Smithburger PL, Kobulinsky LR, Kane-Gill SL. 28. Tanaka M, Mizuno K, Fukuda S, Tajima S, Watanabe Y. Per-

Simulation-based learning versus problem-based learning in an sonality traits associated with intrinsic academic motivation in medical

acute care pharmacotherapy course. Simul Healthc. 2012;7(3): students. Med Educ. 2009;43:384–387.

162–165. 29. Cook DA, Thompson WG, Thomas KG. The Motivated Strate-

9. Smithburger PL, Kane-Gill SL, Ruby CM, Seybert AL. Comparing gies for Learning Questionnaire: score validity among medicine

effectiveness of 3 learning strategies: simulation-based learning, problem- residents. Med Educ. 2011;45(12):1230–1240.

CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing & July 2015 283

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

30. Fisher M, King J, Tague G. The development of a self-directed 33. Leigh GT. High fidelity patient simulation and nursing students’

learning readiness scale for nursing education. Nurse Educ Today. self-efficacy: a review of the literature. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh.

2001;21:516–525. 2008;5(1):article 37.

31. Murad MH, Coto-Yglesias F, Varkey P, Prokop LJ, Murad AL. The 34. Biggs J, Tang C. Teaching for Quality Learning at University.

effectiveness of self-directed learning in health professions educa- Buckingham: SRHE; 2011.

tion: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2010;44:1057–1168. 35. Guo Y, Logan HL, Glueck DH, Muller KE. Selecting a sample

32. Williams SM, Beattie HJ. Problem-based learning in the clinical size for studies with repeated measures. BMC Med Res Methodol.

setting: a systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2008;28(2):146–154. 2013;13:100.

284 CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing & July 2015

Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Вам также может понравиться

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Type The Basic Information of The Class Here: Region Division District School Name School Id School YearДокумент16 страницType The Basic Information of The Class Here: Region Division District School Name School Id School Yearreena joyceОценок пока нет

- Vertical School Design - AdamSwinburnДокумент114 страницVertical School Design - AdamSwinburnFabian AcuñaОценок пока нет

- General Mathematics: Modules From Central OfficeДокумент29 страницGeneral Mathematics: Modules From Central OfficeJose Lim Jr.Оценок пока нет

- Electronics Engineers 04-2019 Room AssignmentДокумент8 страницElectronics Engineers 04-2019 Room AssignmentPRC BaguioОценок пока нет

- Appointment ProposalДокумент1 страницаAppointment ProposalRose Mae Bagunas PadelОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan - Trends 4Документ5 страницLesson Plan - Trends 4Jessie Ryan MielОценок пока нет

- 2006 - LIT102 - Philippine LiteratureДокумент6 страниц2006 - LIT102 - Philippine LiteratureKhail Vince ZoletaОценок пока нет

- 3rd COT DLLДокумент2 страницы3rd COT DLLConnie Reyes San Gabriel80% (5)

- Module 1 - Triangle CongruenceДокумент25 страницModule 1 - Triangle CongruenceJuan Lorenzo50% (2)

- Proposal For Support in Staging "DASTAAN-E-DILLI" - A Musical Play by Children Celebrating 20 Years of AARTH-ASTHAДокумент8 страницProposal For Support in Staging "DASTAAN-E-DILLI" - A Musical Play by Children Celebrating 20 Years of AARTH-ASTHAAARTH-ASTHAОценок пока нет

- Curriculum Vitae: Personal Profile and AttributesДокумент3 страницыCurriculum Vitae: Personal Profile and AttributesKamil KowalskiОценок пока нет

- Interpretive Report: SampleДокумент21 страницаInterpretive Report: SampleRhoda RazzoukОценок пока нет

- Culture Mapping ToolДокумент4 страницыCulture Mapping ToolDinu AlexandruОценок пока нет

- Sample Self Assessment GuideДокумент2 страницыSample Self Assessment GuideFloregie Fugie Ticong BantilingОценок пока нет

- List - of - Requirements University of The VisayasДокумент1 страницаList - of - Requirements University of The VisayasMarcial Jr. MilitanteОценок пока нет

- ScrapДокумент3 страницыScrapMadoi JoshuaОценок пока нет

- M6Ns-Iif-147: Example 1. One of The Modules JM Made Has 2Документ4 страницыM6Ns-Iif-147: Example 1. One of The Modules JM Made Has 2Maria Kyrin AcildoОценок пока нет

- PHIL 2821G OutlineДокумент10 страницPHIL 2821G Outlinebillingsleyc73Оценок пока нет

- Nurs 253 - Final EvaluationДокумент11 страницNurs 253 - Final Evaluationapi-315231385100% (2)

- Pe and Health12Документ5 страницPe and Health12Juefessa June BorlingОценок пока нет

- B.2.1.1 Contextualized LMS/TGS: Magallanes National High SchoolДокумент31 страницаB.2.1.1 Contextualized LMS/TGS: Magallanes National High SchoolChristine Joy Espanto AzarconОценок пока нет

- Curriluim Vitae: Civil StatusДокумент2 страницыCurriluim Vitae: Civil StatusFolegwe FolegweОценок пока нет

- BJIR-Vol.1 No. 1Документ457 страницBJIR-Vol.1 No. 1Kujtim BytyciОценок пока нет

- Project LAIPSE - Basis For The Enhancement of Basic Journalism CompetenceДокумент11 страницProject LAIPSE - Basis For The Enhancement of Basic Journalism CompetenceCarolyn CarolОценок пока нет

- Deductive Vs Inductive LogicsДокумент32 страницыDeductive Vs Inductive LogicsMicheal WorthОценок пока нет

- Erik Erikson Reader PDFДокумент2 страницыErik Erikson Reader PDFBonnie0% (1)

- Communicative Competence Strategies in Various Speech SituationsДокумент9 страницCommunicative Competence Strategies in Various Speech SituationsJhonnamie Senados CarbonОценок пока нет

- Scholarly Research in Marketing: Exploring The "4 Eras" of Thought DevelopmentДокумент16 страницScholarly Research in Marketing: Exploring The "4 Eras" of Thought Developmentneptune04Оценок пока нет

- Call of 129 Jewish and Israeli Scholars To French Parliament About Resolution On Anti-SemitismДокумент7 страницCall of 129 Jewish and Israeli Scholars To French Parliament About Resolution On Anti-Semitismstatement100% (2)