Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Acog Practice Bulletin Summary: Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia

Загружено:

Kevin CasavilcaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Acog Practice Bulletin Summary: Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia

Загружено:

Kevin CasavilcaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

ACOG PRACTICE BULLETIN SUMMARY

Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician–Gynecologists

NUMBER 202

For a comprehensive overview of these recommendations, the full-text Scan this QR code

version of this Practice Bulletin is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ with your smartphone

AOG.0000000000003018. to view the full-text

version of this

Practice Bulletin.

Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal by BhDMf5ePHKbH4TTImqenVKt+hMvjzYvLCwpe45khJN24y7Ea9snRnHZhXnsvOC47 on 01/03/2019

Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. This Practice Bulletin was developed by the American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics in collaboration with Jimmy Espinoza, MD, MSc; Alex Vidaeff, MD,

MPH; Christian M. Pettker, MD; and Hyagriv Simhan, MD.

Gestational Hypertension and

Preeclampsia

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy constitute one of the leading causes of maternal and perinatal mortality worldwide. It

has been estimated that preeclampsia complicates 2–8% of pregnancies globally (1). In Latin America and the Caribbean,

hypertensive disorders are responsible for almost 26% of maternal deaths, whereas in Africa and Asia they contribute to 9%

of deaths. Although maternal mortality is much lower in high-income countries than in developing countries, 16% of

maternal deaths can be attributed to hypertensive disorders (1, 2). In the United States, the rate of preeclampsia increased

by 25% between 1987 and 2004 (3). Moreover, in comparison with women giving birth in 1980, those giving birth in 2003

were at 6.7-fold increased risk of severe preeclampsia (4). This complication is costly: one study reported that in 2012 in the

United States, the estimated cost of preeclampsia within the first 12 months of delivery was $2.18 billion ($1.03 billion for

women and $1.15 billion for infants), which was disproportionately borne by premature births (5). This Practice Bulletin

will provide guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.

Clinical Management Questions

< Are there screening methods that are useful to identify women at risk of developing hypertensive dis-

orders of pregnancy?

< Are there prevention strategies for reducing the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy?

< What is the optimal treatment for women with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia?

< What is the optimal treatment for eclampsia?

< What is the management of acute complications for preeclampsia with HELLP?

< What are the risks of subsequent cardiovascular disease among women with hypertensive disorders of

pregnancy and are there prevention strategies that modify this risk?

VOL. 133, NO. 1, JANUARY 2019 OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY 211

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Clinical Considerations survival is not anticipated. During expectant man-

agement, delivery is recommended at any time in the

and Recommendations case of deterioration of maternal or fetal condition.

< Antihypertensive treatment should be initiated expedi-

The following recommendations are based on good and tiously for acute-onset severe hypertension (systolic

consistent scientific evidence (Level A): blood pressure of 160 mm Hg or more or diastolic

< Women with any of the high-risk factors for pre- blood pressure of 110 mm Hg or more, or both) that is

eclampsia (previous pregnancy with preeclampsia, confirmed as persistent (15 minutes or more). The

multifetal gestation, renal disease, autoimmune dis- available literature suggests that antihypertensive agents

ease, type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic should be administered within 30–60 minutes. How-

hypertension) and those with more than one of the ever, it is recommended to administer antihypertensive

moderate-risk factors (first pregnancy, maternal age therapy as soon as reasonably possible after the criteria

for acute-onset severe hypertension are met.

of 35 years or older, a body mass index of more than

30, family history of preeclampsia, sociodemographic The following recommendations are based primarily on

characteristics, and personal history factors) should consensus and expert opinion (Level C):

receive low-dose (81 mg/day) aspirin for pre-

eclampsia prophylaxis, initiated between 12 weeks < It is recommended that women with gestational

hypertension in the absence of proteinuria are diag-

and 28 weeks of gestation (optimally before 16 weeks

nosed with preeclampsia if they present with any of

of gestation) and continuing until delivery.

the following severe features: thrombocytopenia

< In women with gestational hypertension or pre- (platelet count less than 100,000 3 109/L); impaired

eclampsia without severe features at or beyond 37 0/7 liver function as indicated by abnormally elevated

weeks of gestation, delivery rather than expectant blood concentrations of liver enzymes (to twice the

management upon diagnosis is recommended. upper limit of normal concentration); severe persis-

< Magnesium sulfate should be used for the prevention tent right upper quadrant or epigastric pain and not

and treatment of seizures in women with gestational accounted for by alternative diagnoses; renal insuf-

hypertension and preeclampsia with severe features ficiency (serum creatinine concentration more than

or eclampsia. 1.1 mg/dL or a doubling of the serum creatinine

< Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications should

continue to be used preferentially over opioid an-

algesics. Postpartum patients on magnesium for sei-

zure prophylaxis for preeclampsia did not show [Box 3] Severe Features

differences in blood pressure, antihypertensive re-

quirements, or other adverse events for patients c Systolic blood pressure of 160 mm Hg or more, or

managed with NSAIDs in the postpartum period. diastolic blood pressure of 110 mm Hg or more on

two occasions at least 4 hours apart (unless anti-

The following recommendations are based on limited or hypertensive therapy is initiated before this time)

inconsistent scientific evidence (Level B): c Thrombocytopenia (platelet count less than

100,000 3 109/L)

< Delivery is recommended when gestational hyperten- c Impaired liver function as indicated by abnormally

sion or preeclampsia with severe features is diagnosed elevated blood concentrations of liver enzymes

at or beyond 34 0/7 weeks of gestation, after maternal (to twice the upper limit normal concentration),

stabilization or with labor or prelabor rupture of and severe persistent right upper quadrant or

membranes. Delivery should not be delayed for the epigastric pain unresponsive to medication and

administration of steroids in the late preterm period. not accounted for by alternative diagnoses

Renal insufficiency (serum creatinine concentra-

< The expectant management of preeclampsia with c

tion more than 1.1 mg/dL or a doubling of the

severe features before 34 0/7 weeks of gestation is serum creatinine concentration in the absence of

based on strict selection criteria of those appropriate other renal disease)

candidates and is best accomplished in a setting with c Pulmonary edema

resources appropriate for maternal and neonatal care. c New-onset headache unresponsive to medication

Because expectant management is intended to pro- and not accounted for by alternative diagnoses

vide neonatal benefit at the expense of maternal risk, c Visual disturbances

expectant management is not advised when neonatal

212 Practice Bulletin No. 202 Summary OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

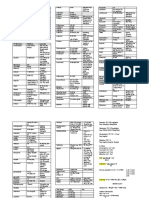

[Table 2] Serum Magnesium Concentration and Toxicities

Serum Magnesium Concentration

mmol/L mEq/L mg/dL Effect

2–3.5 4–7 5–9 Therapeutic range

.3.5 .7 .9 Loss of patellar reflexes

.5 .10 .12 Respiratory paralysis

.12.5 .25 .30 Cardiac arrest

Data from Duley L. Magnesium sulphate regimens for women with eclampsia: messages from the Collaborative Eclampsia Trial. Br

J Obstet Gynaecol 1996;103:103–5 and Lu JF, Nightingale CH. Magnesium sulfate in eclampsia and pre-eclampsia: pharmacokinetic

principles. Clin Pharmacokinet 2000;38:305–14.

concentration in the absence of other renal disease); 4. Ananth CV, Keyes KM, Wapner RJ. Pre-eclampsia rates

pulmonary edema, or new-onset headache unre- in the United States, 1980-2010: age-period-cohort analy-

sis. BMJ 2013;347:f6564.

sponsive to acetaminophen and not accounted for by

alternative diagnoses, or visual disturbances. 5. Stevens W, Shih T, Incerti D, Ton TGN, Lee HC, Peneva

D, et al. Short-term costs of pre-eclampsia to the United

< Women with gestational hypertension who present States health care system. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:

with severe-range blood pressures should be man- 237–48.e16.

aged with the same approach as for women with

severe preeclampsia.

< Among women with gestational hypertension or

preeclampsia without severe features, expectant

Studies were reviewed and evaluated for quality

management up to 37 0/7 weeks of gestation is rec- according to the method outlined by the U.S.

ommended, during which frequent fetal and maternal Preventive Services Task Force. Based on the highest

evaluation is recommended. Fetal monitoring con- level of evidence found in the data, recommendations are

sists of ultrasonography to determine fetal growth provided and graded according to the following

every 3–4 weeks of gestation, and amniotic fluid categories:

volume assessment at least once weekly. In addition, Level A—Recommendations are based on good and

consistent scientific evidence.

an antenatal test one-to-two times per week for pa-

tients with gestational hypertension or preeclampsia Level B—Recommendations are based on limited or

inconsistent scientific evidence.

without severe features is recommended.

Level C—Recommendations are based primarily on

< Epidural or spinal anesthesia is considered acceptable, consensus and expert opinion.

and the risk of epidural hematoma is exceptionally low,

in patients with platelet counts 70 3 109/L or more Full-text document published online on December 20, 2018.

provided that the platelet level is stable, there is no

other acquired or congenital coagulopathy, the platelet Copyright 2018 by the American College of Obstetricians and

function is normal, and the patient is not on any anti- Gynecologists. All rights reserved. No part of this publication

platelet or anticoagulant therapy. may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on the

Internet, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, elec-

tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without prior written permission from the publisher.

References

1. Steegers EA, von Dadelszen P, Duvekot JJ, Pijnenborg R. Requests for authorization to make photocopies should be

Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2010;376:631–44. directed to Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive,

Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400.

2. Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM, Van Look

PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

review. Lancet 2006;367:1066–74. 409 12th Street, SW, PO Box 96920, Washington, DC 20090-6920

3. Wallis AB, Saftlas AF, Hsia J, Atrash HK. Secular trends Official Citation

in the rates of pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. ACOG Practice

hypertension, United States, 1987-2004. Am J Hypertens Bulletin No. 202. American College of Obstetricians and Gy-

2008;21:521–6. necologists. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:e1–25.

VOL. 133, NO. 1, JANUARY 2019 Practice Bulletin No. 202 Summary 213

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

This information is designed as an educational resource to aid clinicians in providing obstetric and gynecologic care, and use

of this information is voluntary. This information should not be considered as inclusive of all proper treatments or methods of

care or as a statement of the standard of care. It is not intended to substitute for the independent professional judgment of the

treating clinician. Variations in practice may be warranted when, in the reasonable judgment of the treating clinician, such

course of action is indicated by the condition of the patient, limitations of available resources, or advances in knowledge or

technology. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reviews its publications regularly; however, its

publications may not reflect the most recent evidence. Any updates to this document can be found on www.acog.org or by

calling the ACOG Resource Center.

While ACOG makes every effort to present accurate and reliable information, this publication is provided “as is” without any

warranty of accuracy, reliability, or otherwise, either express or implied. ACOG does not guarantee, warrant, or endorse the

products or services of any firm, organization, or person. Neither ACOG nor its officers, directors, members, employees, or agents

will be liable for any loss, damage, or claim with respect to any liabilities, including direct, special, indirect, or consequential

damages, incurred in connection with this publication or reliance on the information presented.

All ACOG committee members and authors have submitted a conflict of interest disclosure statement related to this published

product. Any potential conflicts have been considered and managed in accordance with ACOG’s Conflict of Interest Disclosure

Policy. The ACOG policies can be found on acog.org. For products jointly developed with other organizations, conflict of interest

disclosures by representatives of the other organizations are addressed by those organizations. The American College of Ob-

stetricians and Gynecologists has neither solicited nor accepted any commercial involvement in the development of the content of

this published product.

214 Practice Bulletin No. 202 Summary OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Copyright ª by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Вам также может понравиться

- ACOG 2009 Induction of LaborДокумент12 страницACOG 2009 Induction of LaborRiantiara PutrizaОценок пока нет

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No163Документ15 страницACOG Practice Bulletin No163Marco DiestraОценок пока нет

- Multiple Pregnancy: Dr. A. Farid Abdullah, SP - OG, M.KesДокумент33 страницыMultiple Pregnancy: Dr. A. Farid Abdullah, SP - OG, M.KesAndi Farid AОценок пока нет

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202 - Hipertensión Gestacional y ... - Obstetricia y Ginecología PDFДокумент36 страницACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202 - Hipertensión Gestacional y ... - Obstetricia y Ginecología PDFAnghelino Jesus Meza CentenoОценок пока нет

- 190 - Gestational Diabetes Mellitus AgogДокумент16 страниц190 - Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Agogjorge vergara100% (2)

- ACOG PRACTICE BULLETIN 203chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy2019Документ25 страницACOG PRACTICE BULLETIN 203chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy2019ange100% (1)

- Acog 194Документ15 страницAcog 194Marco DiestraОценок пока нет

- Practice Bulletin: Management of Preterm LaborДокумент10 страницPractice Bulletin: Management of Preterm LaborXimena OrtegaОценок пока нет

- GYNE 4.02 - Lower and Upper Genital InfectionДокумент12 страницGYNE 4.02 - Lower and Upper Genital InfectionGray Snell100% (1)

- Acog Gestacion Multiple 2016 PDFДокумент16 страницAcog Gestacion Multiple 2016 PDFRicardo QuintanaОценок пока нет

- Pedia NotesДокумент3 страницыPedia NotesNikki DiocampoОценок пока нет

- Acog PromДокумент14 страницAcog PromjjlazarteОценок пока нет

- gtg60 Cervicalcerclage PDFДокумент21 страницаgtg60 Cervicalcerclage PDFLijoeliyas100% (1)

- Treatment of GoutДокумент21 страницаTreatment of GoutAlbertoBeltránRojasОценок пока нет

- Med TemplateДокумент1 страницаMed TemplateAnbar100% (1)

- Review Adnexal Masses Pregnancy Rcog PDFДокумент6 страницReview Adnexal Masses Pregnancy Rcog PDFRosália Coutada100% (1)

- 2019 - Bowel and Bladder Injury Repair and Follow-Up After Gynecologic Surgery - 00006250-201902000-00012Документ10 страниц2019 - Bowel and Bladder Injury Repair and Follow-Up After Gynecologic Surgery - 00006250-201902000-00012Polyana FloresОценок пока нет

- Module 6 - Benign Gynecologic TumorsДокумент9 страницModule 6 - Benign Gynecologic TumorsRenz Francis SasaОценок пока нет

- (SLE) and PregnancyДокумент60 страниц(SLE) and PregnancyNurfikhaHandayaniОценок пока нет

- Fetal Physiological Measurements: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Fetal and Neonatal Physiological MeasurementsОт EverandFetal Physiological Measurements: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Fetal and Neonatal Physiological MeasurementsPeter RolfeОценок пока нет

- MumpsДокумент16 страницMumpsRahul DhakerОценок пока нет

- Placenta Praevia, Placenta Accreta and Vasa Praevia Managment and Diagnosis Royal College of ObgДокумент26 страницPlacenta Praevia, Placenta Accreta and Vasa Praevia Managment and Diagnosis Royal College of ObgDiana PanaitОценок пока нет

- Breast Abcess PDFДокумент4 страницыBreast Abcess PDFponekОценок пока нет

- ACOG SMFM Joint Practice Bulletin Multiple Gestation 2004Документ15 страницACOG SMFM Joint Practice Bulletin Multiple Gestation 2004Reza ZulkarnainОценок пока нет

- Ovarian TorsionДокумент48 страницOvarian Torsionmaria ilyasОценок пока нет

- RCOG Guidelines - Gestational Trophoblastic DiseaseДокумент12 страницRCOG Guidelines - Gestational Trophoblastic Diseasemob3100% (1)

- 02 Gestational Trophoblastic DiseaseДокумент8 страниц02 Gestational Trophoblastic Diseasemisakichan FrandoОценок пока нет

- Infant of Diabetic MotherДокумент17 страницInfant of Diabetic Motheral_humaira91Оценок пока нет

- Antepartum Hemorrhage PDFДокумент23 страницыAntepartum Hemorrhage PDFfrizkapfОценок пока нет

- Multiple PregnancyДокумент71 страницаMultiple PregnancyAndre PutraОценок пока нет

- Preterm Prelabour Rupture of MembranesДокумент12 страницPreterm Prelabour Rupture of MembranesSeptiany Indahsari DjanОценок пока нет

- 1 GYNE 7 - EndometriosisДокумент6 страниц1 GYNE 7 - EndometriosisIrene FranzОценок пока нет

- Management of Preterm LaborДокумент2 страницыManagement of Preterm LaborpolygoneОценок пока нет

- MebendazoleДокумент1 страницаMebendazolegiselle chloeОценок пока нет

- Breech DeliveryДокумент73 страницыBreech DeliveryFebriendo Vanni Dwi JayantiОценок пока нет

- Shoulder DystociaДокумент8 страницShoulder DystociaMajo MelchiadeОценок пока нет

- Seminar On Obstructed LabourДокумент98 страницSeminar On Obstructed Labourtesfahuntekletilahun80% (5)

- PROLOG: Obstetrics, Eighth Edition (Assessment & Critique)От EverandPROLOG: Obstetrics, Eighth Edition (Assessment & Critique)Рейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (2)

- ACOG Practice Bulletin Prevencion PPДокумент10 страницACOG Practice Bulletin Prevencion PPFelipe LlanosОценок пока нет

- CefepimeДокумент2 страницыCefepimeshendae cosmianoОценок пока нет

- Acog 19Документ25 страницAcog 19Janet GoldameirОценок пока нет

- Diabetes Acog 2017Документ15 страницDiabetes Acog 2017Holger Vicente Guerrero Guerrero100% (1)

- Hemorragia Posparto-AcogДокумент19 страницHemorragia Posparto-AcogCristian LaraОценок пока нет

- Cardiac Disease and Pregnancy RCOG GuidelineДокумент18 страницCardiac Disease and Pregnancy RCOG GuidelinedanielsusenoОценок пока нет

- Poly Hi DR AmnionДокумент7 страницPoly Hi DR Amnionwanwan_adongОценок пока нет

- Repair of Obstetric Perineal LacerationsДокумент7 страницRepair of Obstetric Perineal LacerationsadriantiariОценок пока нет

- OSCE Revision OBG DocumentДокумент60 страницOSCE Revision OBG DocumentshreyaОценок пока нет

- Threatened AbortionДокумент1 страницаThreatened AbortionKEn PilapilОценок пока нет

- Practice Bulletin: Antiphospholipid SyndromeДокумент8 страницPractice Bulletin: Antiphospholipid SyndromeSus ArОценок пока нет

- Obs&Gyn MDC Q and AДокумент36 страницObs&Gyn MDC Q and ARufai Abdul WahabОценок пока нет

- Obstetric Summm 1Документ46 страницObstetric Summm 1ملك عيسىОценок пока нет

- Acog Committee Opinion: Medically Indicated Late-Preterm and Early-Term DeliveriesДокумент5 страницAcog Committee Opinion: Medically Indicated Late-Preterm and Early-Term DeliveriesBianca CaterinalisendraОценок пока нет

- Shoulder DystociaДокумент9 страницShoulder DystociaRorschach VargasОценок пока нет

- Intrauterine Growth RestrictionДокумент3 страницыIntrauterine Growth RestrictionShofiKhaqulIlmyОценок пока нет

- Acute Uterine InversionДокумент6 страницAcute Uterine InversionBima GhovaroliyОценок пока нет

- Tog Thrombocytopenia in PregnancyДокумент7 страницTog Thrombocytopenia in PregnancyAmin Ismail100% (1)

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome in PregnancyДокумент7 страницAntiphospholipid Syndrome in PregnancyDara Dasawulansari SyamsuriОценок пока нет

- StillbirthДокумент4 страницыStillbirthTubagus Siswadi WijaksanaОценок пока нет

- Multiple PregnancyДокумент26 страницMultiple PregnancyOmar mohamedОценок пока нет

- FInal Anemia in PregnancyДокумент57 страницFInal Anemia in PregnancyAiszel Angeli Pepito LigoОценок пока нет

- Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy and Hyperemesis GravidarumДокумент27 страницNausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy and Hyperemesis GravidarumxxdrivexxОценок пока нет

- Abnormal Uterine BleedingДокумент12 страницAbnormal Uterine BleedingGilang DermawanОценок пока нет

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease: (Hydatidiform Mole)Документ12 страницGestational Trophoblastic Disease: (Hydatidiform Mole)Gylle Marie PlazaОценок пока нет

- GBS Acog 979 2020Документ22 страницыGBS Acog 979 2020Tran Thi Ngoc AnhОценок пока нет

- Acute Abdomen in PregnancyДокумент14 страницAcute Abdomen in PregnancyNaila WardhanaОценок пока нет

- Red EyeДокумент6 страницRed EyeRodha Bint HamadОценок пока нет

- Antibiotic Zone Interpretation Guide PDFДокумент2 страницыAntibiotic Zone Interpretation Guide PDFFarandy Insan Sejati100% (2)

- Hubungan Kadar Gula Darah Dengan Hipertensi Pada Pasien Diabetes Mellitus Tipe 2 Di RSUP SanglahДокумент4 страницыHubungan Kadar Gula Darah Dengan Hipertensi Pada Pasien Diabetes Mellitus Tipe 2 Di RSUP SanglahFauzan MuttaqinОценок пока нет

- OmeprazoleДокумент13 страницOmeprazoleKarl Angelo MontanoОценок пока нет

- 100 MCQsДокумент35 страниц100 MCQsBader AlMajedОценок пока нет

- Nuhra Region3 AgendaДокумент69 страницNuhra Region3 AgendaAnonymous jq1TnKbОценок пока нет

- Batuk - Pilek Harga Jumlah Barang: Satuan Masuk Terjual SisaДокумент7 страницBatuk - Pilek Harga Jumlah Barang: Satuan Masuk Terjual Sisadoni januarindraОценок пока нет

- Medical Surgical NursingДокумент6 страницMedical Surgical NursingMariel Febreo MerlanОценок пока нет

- Sukarmin - 2 PDFДокумент7 страницSukarmin - 2 PDFCitra PriyoОценок пока нет

- Herpes ZosterДокумент16 страницHerpes ZosterColleen De la RosaОценок пока нет

- Azithromycin Drug Monograph 18may2020Документ141 страницаAzithromycin Drug Monograph 18may2020OKE channelОценок пока нет

- List of AntibioticsДокумент8 страницList of AntibioticsMiguel Angel Ortega100% (1)

- Formularium Farmasi Cendana 2020Документ42 страницыFormularium Farmasi Cendana 2020Vidyanti Permata DewiОценок пока нет

- Difference Between GERD and PUDДокумент7 страницDifference Between GERD and PUDOla Adel ShabeebОценок пока нет

- No Nama Obat Ven Sediaan Harga SatuanjumlahДокумент2 страницыNo Nama Obat Ven Sediaan Harga SatuanjumlahCINDYAH ANASTASIA CLARITAОценок пока нет

- Master Obat UpdateДокумент55 страницMaster Obat UpdateNurlindaОценок пока нет

- Kehamilan Dengan Bekas Sectio Cecar: Disusun Oleh: Heru Maranata Nababan Pembimbing: Dr. Dr. Donel S, Spog (K)Документ36 страницKehamilan Dengan Bekas Sectio Cecar: Disusun Oleh: Heru Maranata Nababan Pembimbing: Dr. Dr. Donel S, Spog (K)Heru Maranata Nababan100% (1)

- Bahan Laporan Generik Desember 2019Документ176 страницBahan Laporan Generik Desember 2019frizalОценок пока нет

- Latihan Soal UKMPPD Kedokteran VignetteДокумент152 страницыLatihan Soal UKMPPD Kedokteran Vignetteelizabeth tanОценок пока нет

- Prelim List of DrugsДокумент20 страницPrelim List of DrugsJayson Izon SantosОценок пока нет

- Hepatitis Assignment BioДокумент2 страницыHepatitis Assignment BioAthira NairОценок пока нет

- GEFITINIBДокумент3 страницыGEFITINIBErza GenatrikaОценок пока нет

- Neonatal Sepsis: Prof DR Saima BatoolДокумент31 страницаNeonatal Sepsis: Prof DR Saima BatoolSAIMA BATOOLОценок пока нет

- Antibiotic Sensitivity ChartДокумент1 страницаAntibiotic Sensitivity ChartFerdinand von HebraОценок пока нет