Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

A Madness For Identity - Psychiatrische Labels Als Deel Van Identiteit

Загружено:

AndaluzОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

A Madness For Identity - Psychiatrische Labels Als Deel Van Identiteit

Загружено:

AndaluzАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CHARLAND / A MADNESS FOR IDENTITY ■ 335

A Madness for

Identity:

Psychiatric Labels,

Consumer Autonomy,

and the Perils of the

Internet

Louis C. Charland

ABSTRACT: Psychiatric labeling has been the subject of KEYWORDS: autonomy, bioethics, identity, Internet, men-

considerable ethical debate. Much of it has centered tal illness, psychiatry

on issues associated with the application of psychiat-

ric labels. In comparison, far less attention has been

paid to issues associated with the removal of psychiat-

T

ric labels. Ethical problems of this last sort tend to here appears to be a new psychiatric phe-

revolve around identity. Many sufferers are reticent to nomenon emerging in the private chat

relinquish their iatrogenic identity in the face of offi- rooms of the Internet, a novel syndrome

cial label change; some actively resist it. New forms of that revolves around identity. At the same time,

this resistance are taking place in the private chat there are important ethical obstacles that prevent

rooms and virtual communities of the Internet, a do-

psychiatrists and bioethicists from studying that

main where consumer autonomy reigns supreme. Med-

ical sociology, psychiatry, and bioethics have paid phenomenon. The two themes are inextricably

little attention to these developments. Yet these new linked. Psychiatry needs to study the phenome-

consumer-driven initiatives actually pose considerable non, but studying it poses complex ethical prob-

risks to consumers. They also present complex ethical lems. The purpose of the present discussion is to

challenges for researchers. Clinically, there is even describe the putative new syndrome and the eth-

sufficient evidence to wonder whether the Internet ical challenges involved in studying it.

may be the nesting ground for a new kind of identity

The syndrome seems to be a sort of “madness

disturbance. The purpose of the present discussion is

to survey these developments and identify potential for identity.” Its defining feature is a refusal by

issues and problems for future research. Taken as a some psychiatric patients to relinquish the iatro-

whole, the entire episode suggests that we may have genic identity provided by their medical diagnos-

reached a turning point in the history of psychiatry tic labels. In one way, there is nothing new about

where consumer autonomy and the Internet are now the existence of refusals of this type; they proba-

powerful new forces in the manufacture of madness bly go back to the dawn of psychiatry. But there

© 2005 by The Johns Hopkins University Press

11.4charland_01. 335 4/11/05, 12:12 PM

336 ■ PPP / VOL. 11, NO. 4 / DECEMBER 2004

is another way in which the refusals we are because it stereotypes and demeans women. This

concerned with are novel. This is the medium in at least is one way of looking at the ethics of the

which they take place, namely, the Internet. That application of this psychiatric label (Showalter

influences the form they take, which in turn 1986).

determines the kind of phenomenon we are deal- Homosexuality is another ethically controver-

ing with. sial psychiatric label. The label itself is not al-

The phenomenon we are concerned with is ways considered bad, because many homosexu-

largely, perhaps entirely, a product of the partic- als are proud to be called homosexual. Ethical

ular type of communities and social opportuni- problems occur when it is proposed as a psychi-

ties that Internet culture has made possible. In atric label that denotes a disease category. This is

this mostly ungovernable social universe, the forc- what happened when homosexuality was includ-

es of consumer autonomy are running amok. ed as a mental disorder in the second edition of

Many psychiatric patients have decided to retain the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

their psychiatric diagnostic labels no matter what. Disorders of the American Psychiatric Associa-

They are now “autonomous” consumers in a tion (American Psychiatric Association 1952).

very real social and economic sense. Three exam- Its identification as a psychiatric disorder caused

ples illustrate this hypothesis. The labels in ques- a vehement uproar and the label was eventually

tion are multiple personality disorder, borderline removed from the manual (American Psychiatric

personality disorder, and anorexia. In each case, Association 1973, 44). There exist poignant tes-

consumers have mobilized their forces on the timonies of how the disease conception of homo-

Internet to defend their right to wear and live by sexuality caused harm to homosexual patients

their labels. On its side, establishment psychiatry (Duberman 2002). The victims in this case were

seems powerless to stop or control this powerful homosexuals and the problem was the inappro-

new force in the social manufacture of madness. priate medical use of the label homosexual.

The topic is urgent, because there are serious Other ethical problems with psychiatric label-

potential harms to consumers. What can be done ing occur when a legitimate label is imposed

about these new developments depends on what inappropriately and unjustly (Chodoff 1999).

we can find out about them. This discussion is Such abuses are said to have occurred in the

intended as a first step in that direction. To start, former Soviet Union and elsewhere. In these cas-

let us see how these developments fit in the con- es, the label schizophrenia was apparently inap-

text of psychiatric labeling and its associated propriately applied to people who did not medi-

ethical issues. cally warrant the diagnosis. Generally, these were

political dissidents of some sort. The diagnosis of

Applying and Removing sluggish schizophrenia played a part in these

Psychiatric Labels abuses (Merskey and Shafran 1986). Although it

was originally a legitimate medical diagnosis, it

Ethical issues associated with the application was eventually used for inappropriate political

of psychiatric labels tend to focus on cases where ends. These cases of abuse are examples where a

someone is assigned a label they do not want and medical label is inappropriately and unjustly ap-

are helpless to remove it. Sometimes the label plied.

itself is said to be bad because of what it sug- These three examples illustrate one general

gests. At other times, those who do the labeling kind of ethical problem with psychiatric label-

are also held to be bad because they impose the ing. The examples are all different but they share

label without the subject’s consent. One famous a common theme. In each case, the ethical prob-

example that arguably touches on all these ele- lems arise from the fact that a psychiatric label is

ments is hysteria. The victims in this case are the applied. The identity of those who are labeled is

women who are labeled, the guilty are the male negatively compromised because a label is ap-

doctors who do the labeling, and the label is bad plied. Iatrogenic identity here is bad. There is

11.4charland_01. 336 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

CHARLAND / A MADNESS FOR IDENTITY ■ 337

another general kind of ethical problem associat- questions of identity are at stake (DeGrazia 2000;

ed with psychiatric labeling. It occurs when a Edwards 2000; Elliott 2000a; Kramer 2000; Rad-

psychiatric label is removed. This can happen den 1996). They illustrate a disturbing new mad-

when a label is simply abolished. But it can also ness for identity.

happen when a label is significantly changed and Speaking of a new “madness for identity”

important aspects of its original meaning are rings of hyperbole and rhetoric. Is this really a

lost. In this case, the identity of those who are new phenomenon? The current edition of the

labeled can be negatively compromised because Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the Ameri-

a label is removed. These two dimensions of the can Psychiatric Association does have a diagnos-

ethics of psychiatric labels both implicate identi- tic category that seems tailor made for our case,

ty. But there is an important difference. In the namely, Factitious Disorder, which involves the

first case, there is an unwillingness to accept a “intentional production or feigning of physical

label. In the second, there is an unwillingness to or psychological signs or symptoms” (American

relinquish it. When this unwillingness is extreme, Psychiatric Association 1994, 474. It is also im-

it can lead to its own type of madness—a mad- portant that “the motivation for the behavior is

ness for identity. This in any case is the initial to assume the sick role” (American Psychiatric

hypothesis adopted here. Association 1994, 474; emphasis added). As we

Ethical problems that spring from the removal shall see, this is not what seems to be happening

of psychiatric labels have not been discussed as in the individuals we are concerned with. Typi-

much as those that spring from their application. cally, they genuinely are sick and already have a

Consequently, in this discussion we focus on sick role, with all its associated signs and symp-

ethical problems with label removal. The first toms. The problem is that they do not want to

two examples of label removal we consider are give it up. The Internet does provide interesting

multiple personality disorder and borderline per- and novel opportunities for factitious disorder

sonality disorder. The first case is real; it has (Chambers 2004; Feldman 2000). These might

already happened. The second is hypothetical; it even coexist with our putative identity syndrome.

may happen. Part of what makes these examples However, on a first analysis, the two conditions

interesting is the role that identity plays in how do not appear to be the same.

the relevant ethical issues are framed. In each

case, there is an unwillingness to relinquish the Problems With Evidence

iatrogenic identity that a psychiatric label pro-

vides. Often, this appears to be because individu- The Internet plays a major role in our discus-

als with a diagnosis react to a change in labeling sion, especially its private chat rooms. Yet there

as if it somehow invalidates their experience un- is a surprising absence of data on how these

der the label. This, incidentally, may offer one consumer-driven forces affect the application and

therapeutic strategy for addressing the problems removal of psychiatric labels. There does exist

we are considering. It is an area where the phi- interesting work on the influence of the Internet

losophy of psychiatry can make an important on our sense of community and the search for

contribution to the clinical practice of psychia- identity (Putnam 2000; Turkle 1995). But none

try. of it deals with our topic explicitly. Psychiatry

Our third example is an extreme and very has also taken note of the Internet. However,

ethically disturbing case where the unwillingness these discussions tend to focus on issues of ser-

to relinquish a label turns into a desire to indulge vice delivery and education (Yellowlees 2000).

in it. It is not a clear case of label removal, but Finally, in bioethics the Internet is just starting to

exhibits many of the same dynamics, notably, the receive ethical scrutiny. In a fascinating discus-

unwillingness to abandon a label. Together these sion, Tod Chambers describes how easy it is to

examples provide a novel perspective on current pretend you are someone else on the Internet;

debates in bioethics and psychiatric ethics where how one can deceptively play and experiment

11.4charland_01. 337 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

338 ■ PPP / VOL. 11, NO. 4 / DECEMBER 2004

with various virtual roles and identities including topic, the provisional strategy adopted here has

the sick role (Chambers 2004). This scenario been to err on the side of caution and strictly

raises disconcerting possibilities for the subjects follow the injunction to do no harm. As a result,

of this discussion. These are psychiatric patients no direct evidence in the form of testimonies or

and “survivors” who claim they are “no longer Internet citations are provided. Hopefully, the

alone” now that they think they have found indirect evidence referred to will be deemed suf-

kindred spirits on the net. ficient to demonstrate that the problems identi-

Chambers identifies one serious ethical prob- fied require immediate attention.

lem associated with the use of the Internet. There Second, there are also practical problems in-

are other fascinating aspects of the role the Inter- volved in researching our topic. Many Internet

net plays in our discussion. One is the fact that sites come and go and chat rooms can be espe-

psychiatric labels may no longer be solely under cially transitory. Even seasoned insiders can some-

the control of psychiatry. Label change is subject times have problems finding the sites they want

to powerful consumer influences mediated to. It can also be hard to keep up with changing

through the Internet. At the origin of these chang- security technology and shifting addresses. In-

es lies the ethical principle of autonomy, which deed, virtually all of the sites initially consulted

guarantees the right to self-determination to men- in the research leading to this paper have gone

tally competent individuals (Beauchamp and Chil- into the cyber underground. This is particularly

dress 2001, 57–103). The problem is that driven true of the pro-anorexia sites, which are now

by the principle of autonomy and its self-deter- forbidden by leading Internet providers (Reaves

mining individual, the pursuit of identity on the 2001; Udovitch 2002). Note that accessing some

Internet can lead to very serious harms. Howev- of these web sites may even be illegal and expose

er, proving this gives rise to additional ethical researchers to sanctions that range from legal

problems. These concern the acquisition and use prosecution to having one’s Internet service cut

of evidence derived from the Internet. off.

First, there are ethical problems. How is con- All of these problems surrounding the acquisi-

sent to be sought if individuals want to remain tion and use of evidence derived from the Inter-

anonymous or be known only through pseud- net pose great difficulties. Nevertheless, it is still

onyms? And what if some subjects are of dubi- possible to make some headway and that is our

ous competence to consent? How could one de- purpose here. At the very least, it should become

termine competence in such a case? Note also evident that the developments identified here re-

that it might be possible to gain better evidence quire urgent attention.

of what transpires in these chat rooms through

impersonation than by joining as a declared re- Identity and the Harms of

searcher. But then that involves deception, which Label Removal

raises difficult ethical issues of its own, and usually

requires special approval by ethics committees. It is important to recognize that not all cases

Finally, there is the question of harm. It is possi- of label application and removal involve harms.

ble that conducting research in these domains Label application can lead to positive benefits

might cause harms that are not immediately ob- because it leads to successful treatment. Success-

vious to researchers or even subjects. How are ful treatment, in turn, can lead to label removal

we to tell? What might they be? Without this because an individual has been cured, another

information, it is hard to assess the relative harms positive benefit. The examples discussed here are

and benefits of research for participants, which different. In each case, we are concerned with

is an important consideration in gaining approv- how label removal can lead to harms. Resistance

al for research on human subjects. to label removal is one of the main harms dis-

All of this is new territory for bioethics. In the cussed. It is noteworthy that even label removal

absence of any specific enough guidelines on the in the context of successful therapy can lead to

11.4charland_01. 338 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

CHARLAND / A MADNESS FOR IDENTITY ■ 339

harms. The pivotal factor in all these cases is the tion and dissemination. It is now a powerful

fact that individuals sometimes identify very reinforcing factor in the manufacture of iatro-

strongly with their labels. A good example of the genic identity and the ethics of labeling. In part,

harm that can ensue when a psychiatric label is this is because the Internet provides a medium

removed is provided in the autobiography of where iatrogenic labels can be kept alive by con-

New Zealand author Janet Frame. sumers even though they have been psychiatri-

Frame vividly recounts her distress at finding cally abolished by the medical establishment. But

out that, after years of being diagnosed as a first let us look more closely at how identity

schizophrenic, the diagnosis was incorrect. She figures in the ethical issues we are concerned

writes that, “the loss was great . . . the truth with.

seemed to me more terrifying than the lie” (Frame Many psychiatric patients suffer from disor-

1985, 103). Her diagnosis was gone, “officially ders that directly implicate questions of identity.

banished by the experts” (p. 103). In the course Some psychiatric conditions are actually called

of her testimony, Frame describes being “stripped disorders of identity. In these cases, the disorder

of a garment I had worn for twelve or thirteen a person is said to have can shape their concep-

years” (p. 103). She also explains what her diag- tion of who they think they are. Initially, many

nosis came to mean for her: “how in the midst of patients resist the application of psychiatric la-

the agony and terror of the acceptance, I found bels. This certainly appears to be the case with

the unexpected warmth, comfort, and protec- borderline personality disorder, a label associat-

tion: how I had longed to be rid of the opinion, ed with the most “difficult” psychiatric patients

but was unwilling to part with it, and even when (Antai-Otong 2003; Gross et al. 2002; Loughrey

I did not wear it openly I always had it for Jackson, and Wobbleton 1997). However, as we

emergency, to put on quickly, for shelter from the shall see, in some cases even a diagnosis of bor-

cruel world” (p. 103). derline personality disorder can eventually pro-

Although she resisted it at first, Frame eventu- vide a welcome sense of identity: iatrogenic iden-

ally “surrendered” and accepted her label. When tity. You are, at least, a person with that disorder.

she was invited to relinquish it, she suffered an So the borderline diagnosis can provide a min-

identity crisis of a serious sort: “the official plun- imal sense of identity for some people; it pro-

der of my self-esteem (p. 103). Happily, she final- vides them with an iatrogenic identity. The fact

ly managed to come to terms with giving up her that this can happen with borderline diagnosis is

label. Frame’s experience is a good example of especially interesting, because the label is so of-

how closely people can identify with their psy- ten actively resented by those who are labeled

chiatric labels and how they can suffer when that way. Other psychiatric diagnoses can also

those labels are removed. It is a fitting opening provide a welcome sense of identity for psychiat-

for the more sinister problems with identity ex- ric patients. In general, the initial sense of identi-

amined here. ty provided by iatrogenic identity often gets am-

plified when sufferers discover self-help

The Manufacture of organizations and Internet sites devoted to their

Iatrogenic Identity condition. Not surprisingly, people identify with

the topics and other participants of these sites.

Psychiatric diagnostic labels can provide an Once they actively get involved and enter the

iatrogenic identity for the persons they label. It is private chat rooms, they are finally no longer

important to understand how this iatrogenic iden- alone. Iatrogenic identity is the key to this need

tity is socially manufactured and sustained to to identify. The simple fact of stigma is probably

appreciate how identity figures in the ethical a powerful motivating factor. This is because

problems associated with the removal of such stigma is often tied to an increased need for

labels. The role of the Internet has become in- acceptance (Goffman 1963, 8). When you join

creasingly prominent in psychiatric label forma- these sites, your label is no longer a stigma; it is a

11.4charland_01. 339 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

340 ■ PPP / VOL. 11, NO. 4 / DECEMBER 2004

shared and accepted feature of who you are. You dissociative fugues of the nineteenth century were

have found people of your own kind and can made possible by the development of tourism

bask in the solace that there are others like you (Hacking 1998). Of course, they were not creat-

(Goffman 1963, 21–22). In this way, the Internet ed by tourism alone. But the social, institutional,

has come to play an increasingly important role and industrial circumstances that accompanied

in the social manufacture of psychiatric labels. the emergence of tourism opened a new ecologi-

No doubt, this is an important new addition to cal niche in which travel became a lot easier.

what some cynics have called the “manufacture Individuals suffering from amnesia or dissocia-

of madness” (Szasz 1970). The expanding role of tive episodes could travel relatively easily if they

the Internet in the manufacture and promotion found the means. It was now possible to suffer

of psychiatric disease has not been adequately from “fugue.”

addressed in contemporary psychiatric histories. In another related study, Hacking shows how

In most the word does not even figure in the the epidemic of multiple personality in recent

index (Healy 2002; Shorter 1997). Recently, how- times emerged out of a new understanding of

ever, it has attracted the attention of bioethicist trauma and child abuse and a peculiar American

Carl Elliott. obsession with the family (Hacking 1995). His

In his book, Better Than Well: American Med- hypothesis is that a certain set of social circum-

icine Meets the American Dream, Carl Elliott stances—a particular ecological niche—was re-

examines how the notions of personal fulfill- quired before the multiple personality epidemic

ment, self-realization, and enhancement have could take its hold on popular consciousness.

shaped and influenced American medicine and Likewise, Carl Elliott’s research capitalizes on

what Americans expect from it (Elliott 2003). the fact that most psychiatric disorders now have

Much of his research is drawn from Internet web supporting organizations and web sites for suf-

sites sponsored by self-help organizations. One ferers. Each disorder has its own “virtual com-

notorious example is a group of individuals who munity” on the Internet. Some of these web sites

advocate for the right to have their limbs ampu- are partially or entirely created and supported by

tated (Elliott 2003, 208–238; see also Elliott industry. Others are entirely consumer driven. In

2000b). Some members of this group are lobby- both cases the Internet is the common denomina-

ing for the medical recognition of their disorder. tor. Because of its accessibility and limitless geo-

Variously referred to as Apotemnophilia and graphical range of action, the Internet has played

Amputee Disorder, this condition is sometimes a pivotal role in the creation of these virtual

confused with Gender Identity Disorder and Body communities. In the words of Robert Putnam,

Dysmorphic Disorder. Evidently, it is a condition “computer mediated communication can sup-

still in search of a label. Many sufferers hope this port large, dense, yet fluid groups that cut across

will be a psychiatric medical label, largely be- existing organizational boundaries, increasing the

cause of what this implies for treatment: medi- involvement of otherwise peripheral participants”

cally sanctioned and supervised amputations. El- (2000, 172). This is an excellent example of

liott’s analysis strongly suggests that this social what Hacking refers to as a “vector” in an eco-

mobilization of amputee seekers—“Wanna- logical niche.

bees”—would probably not exist without the Apparently, then, the Internet is a new addi-

Internet. He notes that, “by all accounts, the tion to the ecological niche in which mental dis-

Internet has been revolutionary for Wannabees” orders rise and fall. It permits new forms of

(Elliott 2003, 217). This could be the first psy- community association; a sort of “cyberbalki-

chiatric disease “manufactured” in cyberspace. naization” where like-minded individuals can join

The Internet appears to be a new addition to and share in a special inner circle (Putnam 2000,

the ecological niche philosopher Ian Hacking 178). These are not typical self-help groups like

says is required for the social birth and growth of those where members sit in a circle talking. Pri-

some psychiatric illnesses. He shows how the vate chat rooms, in particular, provide a particu-

11.4charland_01. 340 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

CHARLAND / A MADNESS FOR IDENTITY ■ 341

larly paradoxical form of “community” involve- cation or removal of labels for psychiatric disor-

ment. They are solipsistic communities. Unlike ders. There is now a web site advocating for the

traditional sit-down self-help groups, participants psychiatric baptism of the label Body Integrity

in chat rooms are strangely isolated in their own Identity Disorder, the latest proto-psychiatric la-

personal protective cyber bubbles. At the same bel for amputation seekers.

time, they are sometimes immensely open and Participation in these psychiatric virtual com-

vulnerable. Normal rituals and procedures of munities probably strongly reinforces the iatro-

social interaction are different or inapplicable in genic identity of their members. Validation is

these chat rooms. Many participants never actu- both sought and found. As Elliott notes, “on the

ally meet in person and some probably would Internet you can find a community to which you

never want to. Intimacy is both heightened, but can listen and reveal yourself, and instant valida-

also more artificial, because it is often artificially tion for your condition, whatever it may be”

restricted to a few key topics. It is also more (Elliott 2003, 217). For many sufferers, shared

fragile, because people can come and go, are Internet chat rooms are the only route to the

accepted or banished, with little accountability relief of knowing that they are no longer alone, a

or recourse. Indeed, cyber friends seem to be mantra that resonates across this virtual world.

more interchangeable and replaceable than “real” For many of these geographically isolated and

ones. Finally, there is no proverbial coffee and socially alienated identity seekers, “all they have

everyday chit chat after the meeting, because is the Internet, their own troubled lives, and the

“meetings” usually never really start or end; they place where those two things intersect” (Elliott

are eternally ongoing, always there, at the click 2000b, 84). The solidarity made possible by the

of a mouse. Internet thus provides solace through shared ex-

Some of these virtual disease communities are perience and companionship. Because these are

openly funded by the medical and pharmaceuti- all positive benefits, they reinforce the sense of

cal establishment. Indeed, the suggestion has been identity provided by the original diagnosis. As a

made that pharmaceutical companies sometimes result, people probably become more attached to

engage in the creation of such virtual communi- their diagnosis and iatrogenic identity. In effect,

ties to market the existence of a new disease their identity becomes increasingly defined by,

concept to prepare the way for the medication, and inextricably intertwined with, their diagno-

which is still in development (Moynihan 2003). sis. Philosopher Ian Hacking calls this process

However, other virtual disease communities are the “looping effect of kinds”.

genuinely self-help projects run by real psychiat- The looping effect of kinds occurs when “peo-

ric “survivors.” Most of these web sites provide ple classified in a certain way tend to conform to

information about the disorder in question, as or grow into the ways they are described” (Hack-

well as links and referrals for consultation about ing 1995, 21; see also Elliott 2003, 227–234).

the disorder. Especially significant is the fact that Classification of this sort is an interactive phe-

they almost always provide chat rooms where nomenon. This is because the classifications that

sufferers can share their experiences of what it is do the classifying “interact with the people clas-

like to live and cope with their disorder. These sified by them” (Hacking 1999, 123). This gives

chat rooms offer solace and solidarity for the rise to the looping effect that connects what is

pain and alienation sufferers usually experience classified with what does the classifying (Hack-

as the result of the stigma associated with their ing 1999, 105, 121). In this spiraling dialectical

disorder (Elliott 2003, 218; see also Goffman process, each element—the classification and the

1963, 22). Finally, many sites engage in advoca- classified—mutually reinforce and sustain each

cy of some sort. Typical advocacy themes include other as they evolve jointly. There is considerable

fighting the stigma associated with a particular evidence that the Hacking looping effect is a

disorder, challenging or promoting various treat- genuine sociological phenomenon. In his work

ments, and even sometimes arguing for the appli- on psychiatric labeling, Thomas Scheff refers to

11.4charland_01. 341 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

342 ■ PPP / VOL. 11, NO. 4 / DECEMBER 2004

something very similar, which he calls “feedback fession (Goldstein 2001; Scull 1993). Neither

in deviance amplifying systems” (1966, 97–101). patients nor patient groups were consulted when

Edwin Lemert describes a related phenomenon psychiatric labels were applied and removed. To-

called “secondary deviance” (1972, 63). In all of day, psychiatric labeling is a much more complex

these cases, the focus is on how labels become process, subject to numerous social, political,

integral organizing factors in the lives of the and economic interests (Healy 2002, 129–178).

individuals who are labeled, as they search for The examples below also testify to this. They are

validation and acceptance by bonding with oth- meant to illustrate the thesis that the removal of

ers of their own kind. psychiatric labels can lead to difficult ethical

Elliott and Hacking fail to mention one cen- problems that are different from those normally

tral aspect of the manufacture of iatrogenic iden- associated with the application of labels.

tity, namely the role of autonomy. Compared to

previous ages where paternalism was the domi- Multiple Personality

nant ethical and political ideology, we now live Disorder

in an age of autonomy where the right to self-

determination of the individual is paramount. Multiple Personality Disorder has “gone out

Autonomy is enshrined in both law and ethics in of existence” (Hacking 1995, 17). The official

the doctrine of informed consent (Beauchamp name for what used to be called “Multiple Per-

and Childress 2001, 57–103). It is also manifest sonality Disorder” is now “Dissociative Iden-

in the openness to pluralism and diversity so tity Disorder” (American Psychiatric Association

prevalent today. Autonomy also has economic 1994). The old label is now only mentioned as a

dimensions and is reflected in the important place reminder of the new label’s origins. In the rele-

of customer choice and satisfaction in our con- vant DSM section, it is stated in brackets: “(for-

sumer culture. These combined social manifesta- merly Multiple Personality Disorder).”

tions of autonomy have had dramatic conse- This change in the psychiatric labeling might

quences for the practice of psychiatry and the look like a simple case of exchange but it is not.

“manufacture” of psychiatric labels. It involves the replacement of a label that de-

At no time in the history of psychiatry have notes one thing by a new label that denotes

members of the public exercised so much power another. The change is therefore not merely cos-

over the psychiatric establishment that serves metic; it is materially significant. According to

them. Things were not always so. Before psychi- the scientific authorities responsible for initiat-

atry, there were quite simply no “psychiatric” ing and implementing the change, the reason for

labels. For example, speaking of the historical the amendment was to focus on the real patholo-

situation in England prior to the development of gy involved in the original Multiple Personality

psychiatry as a profession, historian Roy Porter label. The point is that integral multiple person-

states that “particular specifications of madness alities are not the focus of the pathology in ques-

were, of course, ‘socially constructed’” (1987, tion. Rather, the fundamental problem is a disin-

33). However, he points out that “they were tegration of identity in one personality. The real

constructed out of grassroots experiences and problem then is one of integration. It affects

community tensions rather being essentially med- identity, consciousness, and memory. In the words

ical codifications serving the interests of a ‘psy of Robert Spitzer, the architect of the change,

profession’ or a ‘therapeutic state’, as arguably “the problem is not having too many personali-

they eventually became” (Porter 1987, 33). Things ties, it is having less than one personality” (Hack-

changed with the development of psychiatry as a ing 1995, 18). In effect, a theoretical commit-

distinct clinical profession. Labeling then entered ment to the existence of multiple personalities

an age of psychiatric paternalism and the defini- thought to be real has been replaced by a com-

tion and deployment of psychiatric labels was mitment to the presence of “two or more identi-

the exclusive prerogative of the psychiatric pro- ties or personalities or personality states.” Pres-

11.4charland_01. 342 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

CHARLAND / A MADNESS FOR IDENTITY ■ 343

ence in this case means present to consciousness. delusional figments of your disorder. Your prob-

So although “two or more identities or personal- lem is not that you have too many personalities,

ities or personality states” may be said to be but rather that you do not even have one. It is

present by subjects, and although they may be hard not to think that this would result in serious

experienced as “real,” like delusions, they are iatrogenic trauma. This is especially true given

not real. Multiple personalities during the reign that the patients in question already suffer from

of DSM-III were real, but after DSM-IV they severe problems with identity. The sudden change

were not. That surely is a big difference; from in diagnosis simply compounds these original

real entity to delusional figment. problems. From a clinical perspective, then, there

The change did not go unchallenged. Support are good reasons to believe that as a matter of

groups and other interested parties protested principle the proposed change constitutes a plau-

(Hacking 1995, 269 nt. 8, 270 nt. 20, 271 nt. sible potential harm to patients; quite likely, a

31). Still, the change went ahead. Physicians could very serious harm. Without access to actual clin-

no longer write “MPD” as a diagnosis. The In- ical records or personal testimony, it is hard to

ternational Society for the Study of Multiple Per- validate this claim empirically. But as an argu-

sonality and Dissociation had to change its name, ment based on principle, the worry is still worth

and did. It became The International Society for taking seriously.

the Study of Dissociation. The case of Multiple There is some indirect evidence that the change

Personality Disorder is therefore a clear example in diagnosis from Multiple Personality to Disso-

of label removal. What were the ethical issues ciative Disorder may have caused actual harm to

involved? patients. It can be found on the numerous web

Any analysis of the ethical issues involved in sites sponsored by interested individuals and sup-

the change from Multiple Personality to Disso- porting organizations. But the evidence is not

ciative Disorders will probably vary depending uniform. One reaction is denial that any signifi-

on whose interests are involved. Because of the cant change has occurred. The two diagnoses are

many interests involved, the situation is compli- treated as equivalent or the change is regarded as

cated. In his famous study on the topic, philoso- irrelevant. In one case, the sponsoring organiza-

pher Ian Hacking traces the political, social, med- tion officially states that they simply disagree

ical, and moral factors in the rise and fall of with the change. Indeed, in a large number of

Multiple Personality Disorder (Hacking 1995). cases, individuals and organizations have simply

One of the lessons of his account is that none of retained the old language of multiples and its

these factors can really be studied in isolation. association with real alternate personalities.

Nonetheless, it should be possible to say a few Evidently, the medical death of a psychiatric

things about the clinical circumstances of pa- label is not always final; there can be consumer

tients during these developments. Consider, for label survival and immortality after death. This

example, the possible harm to patients implied is a consequence of the power shifts that have

by the sort of diagnostic change in question. occurred in this new age of autonomy. Patient

There are important considerations here. autonomy now includes the ability of patients to

Suppose you are a patient diagnosed with contest and defy the nosological edicts of medi-

Multiple Personality Disorder during the DSM- cal authority. You can remain a multiple if you

III era. Imagine that after being encouraged to want to. One way to interpret these reactions is

first accept the existence of your multiples, you denial in the face of real harm. Giving up the

have spent the following two years talking and multiple label is simply too confusing and dis-

negotiating with them under the guidance of tressing, and so many patients have organized

your therapist. One day your therapist informs themselves to keep it. Together with the plausible

you of a decision by the American Psychiatric imaginary clinical scenario painted, these obser-

Association that your multiples are no longer vations should constitute sufficient evidence that

thought to be real personalities. They are merely in some cases, the removal of a psychiatric label

11.4charland_01. 343 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

344 ■ PPP / VOL. 11, NO. 4 / DECEMBER 2004

is likely to lead to harm. This is an issue in disorders of personality, namely the dimensional

psychiatric ethics that deserves careful attention approach. On a dimensional view, “personality

as psychiatric labels continue to appear and dis- disorders represent maladaptive variants of per-

appear. sonality traits that merge imperceptibly into nor-

mality and into one another” (American Psychi-

Borderline Personality atric Association 2000, 689). This is in stark

Disorder contrast to the categorical model, where person-

ality disorders represent “qualitatively different

The example of Multiple Personality Disorder clinical syndromes” (American Psychiatric Asso-

we have just discussed has actually taken place. ciation 2000, 689). There are good reasons to

There is some evidence for believing that it repre- believe that the current categorical scheme for

sents a case where label change can lead to seri- personality disorders may be replaced by a di-

ous harm for patients. Another more speculative mensional one in the next edition of the DSM,

but timely example is Borderline Personality Dis- namely, DSM-V (Charland 2004). The arguments

order. In this case, there are good grounds to are complex. The main reason cited in defense of

believe that label change may happen. This could the change is that the current categories for per-

cause serious harm to patients currently diag- sonality disorders have not been sufficiently em-

nosed with that disorder who have finally found pirically validated. To put it bluntly, there is not

an identity—an iatrogenic identity—through their enough evidence to believe that the existing DSM

disorder. Again, these are patients who already classifications actually capture real pathologies

have problems with identity. This compounds of personality. In effect, the “current classifica-

the possible harms of label removal. tions are arbitrary collections of diagnoses drawn

Borderline Personality Disorder is currently from diverse sources without a clear rationale or

defined as “a pervasive pattern of instability of explicit structure supported by empirical re-

interpersonal relationships, self-image, and af- search” (Livesely and Lang 2000, 34; see also

fects, . . . marked by impulsivity beginning by Livesely 2003).

early adulthood and present in a variety of con- There is therefore a very good chance that the

texts” (American Psychiatric Association 2000, current DSM personality disorders may be radi-

710). Typical manifestations include emotionally cally revised in the next edition of the DSM. The

unstable behavior, suicidal threats, manipulation, adoption of a dimensional model would repre-

inappropriate and intense anger, a chronic sense sent a drastic change, a significant paradigm shift

of emptiness, as well as other signs and symp- (Kuhn 1962). It is not clear whether or how

toms. A central feature of the disorder is a “per- much of the original classifications and their

sistently unstable self-image and sense of self” labels would be retained. In some dimensional

(American Psychiatric Association 2000, 710). proposals, probably most current terms for these

In the current DSM, Borderline Personality Dis- disorders would be abandoned. What if this hap-

order is grouped with three other personality pened?

disorders in a cluster. It is part of the Cluster B There are now many consumer web sites de-

disorders, the “dramatic” ones. The Cluster B voted entirely to Borderline Personality Disor-

disorders are the Antisocial, Borderline, Histri- der. Many of these are for persons who care for

onic, and Narcissistic Personality Disorders persons with the diagnosis. In these sites, care-

(American Psychiatric Association 2000, 685). givers can find information about the disorder

The remaining six personality disorders are and current treatment alternatives. Other sites

grouped in Clusters A and C. are more exclusively targeted to borderline indi-

At present, all the DSM personality disorders viduals themselves. These usually offer chat rooms

are classified categorically. This is in keeping to share experiences with fellow borderlines. Be-

with the DSM general categorical orientation. cause borderline individuals tend to generate and

However, there is an alternative way of viewing experience a lot of friction in their dealings with

11.4charland_01. 344 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

CHARLAND / A MADNESS FOR IDENTITY ■ 345

professional and family caregivers, these chat and chat rooms on the Internet. In these virtual

rooms offer a sort of “sanctuary” away from the communities sufferers laud each others’ efforts

normal reprimands borderlines encounter in their to starve and cut themselves. Some of these sites

dealings with the “outside” world. The chat post pictures that may put researchers at risk of

rooms evidently provide welcome relief for the being charged with pedophilia and other por-

exasperated borderline individual. However, at nography-related offences. In this case, ethical

the same time, they also reinforce and validate problems in research are compounded by legal

the borderline diagnosis. They are a strand in Ian ones.

Hacking’s “looping effect of kinds,” as men- Because these ethically questionable practices

tioned. so obviously cause harm to vulnerable psychiat-

Many of the borderline individuals who use ric patients, is it not imperative that psychiatrists

and visit the borderline chat rooms are “survi- and bioethicists figure out how to study them?

vors” trying to learn to live with their diagnosis. Yet this is a domain where exact references and

Apparently many do not question the diagnosis. citations might be very harmful. In effect, they

They assume it is valid. In this context of solidar- could function as advertisement for these dan-

ity and sharing, the borderline diagnosis proba- gerous sites and very likely put vulnerable and

bly provides a sense of identity—iatrogenic iden- lonely identity seekers at risk. Some “survivors”

tity—for persons who are clearly plagued by speak of the risk of being “triggered” by acciden-

serious identity problems and disturbances. It tal visits to these “pro” disease sites.

therefore seems plausible that the abolition of Psychiatrist David Healy traces the origins of

that diagnostic label could cause serious harm the modern syndrome of anorexia nervosa to the

and confusion to affected individuals. This con- 1870s. He describes successive theories and de-

clusion, however, is only tentative and somewhat scriptions of the condition, starting with the work

speculative. The evidence alluded to here is based of Charles Laségue and William Gull, through

on what can be gathered from borderline chat Paul Janet, to more recent accounts like the one

rooms from the outside by an outsider. Evidence provided by David Garner and Paul Garfinkel

from borderline insiders has also been consulted, (Healy 2002, 359). On the whole, Healy appears

but those persons have chosen to remain anony- to consider anorexia a “transient mental illness”

mous. of the sort Ian Hacking describes in his book,

Mad Travelers (Hacking 1998). That is, he views

Pro-Anorexia it as a kind of mental illness that is inextricably

tied to specific social and historical circumstanc-

The search for identity can also take a dark es, including, notably, the development of the

turn in the unregulated virtual communities of weighting scale (Healy 2002, 361). Note that for

the Internet. Some identity seekers attempt to Healy, calling an illness transient in this sense

reinforce their sense of iatrogenic identity by does not exclude chronic, life-long, mental ill-

indulging in their disease. This is a telling illus- nesses of great severity. In this, perhaps, his use

tration of Lemert’s “self-defeating deviance” of the term departs slightly from Hacking, for

(Lemert 1972, 85). Certainly, these individuals whom transient illnesses are perhaps slightly less

would surely resist label removal of the official severe. However, what seems sure enough is that

sort. But they even appear to resist label removal for both of them anorexia and its pro-anorexia

of a therapeutic kind. They do no want to get manifestations constitute severe mental illnesses

well and instead indulge in how to be sick— that at the same time can be called transient in an

more effectively. In this third example, the search important sense. In Hacking’s terms, the pro-

for identity has degenerated into a full-fledged anorexia syndrome we have just described sug-

madness for identity. gests that the “ecological niche” of anorexia now

Consider the fact that there are “pro-anorex- includes a new “vector” (Hacking 1998, 51–81),

ia,” “pro-bulimia,” and even “pro-cutting” sites namely the Internet. Slang and colloquial terms

11.4charland_01. 345 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

346 ■ PPP / VOL. 11, NO. 4 / DECEMBER 2004

mark the arrival of this new form of anorexia. striving for medical recognition of their condi-

We now live in an age where there are “weborex- tion as a genuine medical disorder; they seek

ics” (Schmitt 2004). iatrogenic identity. This is very different from the

cases we have considered, where the concern is

How Novel This Madness? to retain an iatrogenic identity that already ex-

ists. Note that Elliott’s wannabees do not appear

We have considered three examples of what to be cases of Factitious Disorder either. The

appears to be a disturbing new madness for iden- main reason is that their signs and symptoms

tity taking place on the Internet. Based on the appear to be mostly genuine. They do not inten-

evidence consulted for the present article, it is tionally produce or feign their signs and symp-

impossible to say conclusively whether the three toms in the manner required for a diagnosis of

examples of label retention discussed here form a Factitious Disorder.

unified syndrome. They do appear to form a fam- One other possible diagnosis for our three

ily, with shared resemblances and overlapping cases comes to mind. This is hysteria. As a medi-

themes. Further research is required before any- cal diagnostic label or category, the term hysteria

thing more concrete can be said. Nevertheless, has fallen out of favor in modern psychiatric

despite the poverty of the available evidence, it is circles. At the same time, the term keeps on

helpful to try to distinguish the phenomenon we resurfacing outside psychiatry. In the words of

have been discussing from other related psychi- one commentator, “no term so vilified is yet so

atric conditions with which it might be confused. popular; none so near extinction appears in bet-

At the start of our discussion, we dismissed ter health” (Slavney 1990, 3).

the possibility that the syndrome we are con- Despite the fact that the label hysteria has

cerned with is simply Factitious Disorder. The fallen into medical disfavor, some clinicians in-

reason for this claim should now be clear. In each sist it is still useful (Healy 1993; Slavney 1990).

of our three examples, the individuals in ques- But generally it is outside medical circles that

tion already are sick and have a sick role. They hysteria is popular. One immensely fashionable

are not healthy individuals who feign signs and account has recently been articulated by histori-

symptoms in order to assume a sick role. The an and cultural critic Elaine Showalter. The syn-

problem is that they do not want to relinquish drome she describes bears some resemblance to

the sick role they have. As we saw, in some cases, the problems of identity described here. It is

they even want to retain and reinforce their “sick therefore worth asking whether our putative new

role” with a vengeance, by indulging in it. None- syndrome may be a form of hysteria of the sort

theless, the suggestion that our syndrome may described by Elaine Showalter. So, could the ex-

ultimately be a new variant of Factitious Disor- amples we have considered simply be manifesta-

der is worth keeping in mind. Settling that ques- tions of the hysterical epidemics discussed in

tion would require clinical data, which as we Showalter’s provocative book, Hystories (Show-

have seen, is practically and ethically hard to alter 1997)? She does list anorexia and multiple

acquire. For the time being, the wisest course personality among the “hysterical epidemics” she

seems to be to consider the syndrome described describes. Is this maybe the correct interpreta-

here to be a distinct from Factitious Disorder. tion of our putative new syndrome? Again, to

Our discussion is obviously heavily indebted really answer this question conclusively we need

to Carl Elliott’s fascinating account of amputee better clinical evidence. But even on a very gener-

“wannabees” and his description of their special al level the diagnosis of hysteria seems off the

Internet culture; the “ecological niche” in which mark, at least as it is formulated by Showalter.

their disorder thrives. However, it is important In her book, Showalter “redefines” hysteria

to appreciate that the phenomenon described as “a universal human response to emotional

here is quite different. Elliott’s “wannabees” do conflict” (Showalter 1997, 17). She claims it is a

have problems with identity. In part, they are “mimetic disorder; it mimics culturally permissi-

11.4charland_01. 346 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

CHARLAND / A MADNESS FOR IDENTITY ■ 347

ble expressions of distress” (Showalter 1997, virtual communities can be kept alive online

15). The key to hysteria is the “interdependence through the technologies of the Internet. These

between mind and body” (Showalter 1997, 12). both validate and reinforce psychiatric diagnoses

Initially, hysteria was thought to be an illness of that may no longer be considered scientifically

the body that affected the mind. Later it became valid. Thus psychiatric labels may survive among

an illness of the mind that affected the body consumers although they have been abolished by

(Showalter 1997, 14). As indicated, it is a cul- professionals.

ture-bound syndrome. And so, signs and symp- The relative independence and persistence of

toms of distress are taken from a local pool of psychiatric diagnostic labels despite their abol-

socially accepted manifestations of distress. Vari- ishment by institutional psychiatry raises several

ous types of hysteria thrive and succeed each novel ethical problems. First, because persons

other as one culturally accepted set of signs and often identify with their label, to remove a label

symptoms is replaced by another. According to is to threaten a person’s identity. Saying the label

Showalter, the most recent manifestations of hys- is no longer legitimate, or was a mistake in the

teria in the West are chronic fatigue syndrome, first place, can therefore cause serious harm,

Gulf war syndrome, recovered memory, multiple particularly to persons already suffering from

personality disorder, satanic ritual abuse, and disorders that implicate identity. Second, the re-

alien abduction. tention of psychiatric labels by consumer forces

Showalter’s expanded concept of hysteria is that operate independently of the psychiatric es-

interesting and suggestive in many ways, espe- tablishment can possibly cause further harm to

cially her attention to the role of modern media patients if the labels are truly empirically invalid.

in the rise and fall of the various epidemics she New, more scientifically appropriate labels may

describes. But her account of hysteria can also be not be adopted and more effective treatments

criticized for being too wide and encompassing. may not be sought.

A more conservative analysis would retain what Some of the ethical issues identified in this

is special about hysteria and at the same demar- discussion arguably existed before the Internet.

cate it from the putative identity syndrome I But undoubtedly they have acquired a new scope

have described (Merskey 1992, 1995). On the and dynamic as a result of it. This is new territo-

question of the media, it is notable that Show- ry for both psychiatry and bioethics. Despite

alter never seems to single out the Internet. This their good intentions, web sites that offer con-

makes her account and the syndromes she dis- sumer label survival after official label death

cusses heavily dependent on public media. This may prevent sufferers from getting better help

is quite different from the more private, intimate, and treatment. There is also the worrisome pos-

personal, and social nature of the identity syn- sibility that sufferers in search of solidarity and a

drome described here. In sum, although Show- validated identity may be lured by “pro” disease

alter’s account of modern “hystories” is relevant sites quite contrary to the ideals of health and

to our topic, the two subjects seem initially quite recovery. In both cases, the potential harms are

different and should be kept separate until there considerable. Not to be forgotten is the possibil-

is evidence to show otherwise. ity that in a context like this the Internet may

itself constitute a harm. Some critics have lik-

Psychiatry, Autonomy, and ened life on the Internet to a “Hobbesian state of

Identity nature” (Putnam 2000, 173). Doubts have also

been raised about whether the Internet might

The evidence reviewed here suggests that psy- hinder rather than enhance communication be-

chiatric labels can survive and even flourish with- cause of its intellectual and verbal orientation

out psychiatry. The examples we have examined (Putnam 2000, 176).

show that where there exists sufficient consumer The hypothesis advanced here is that partici-

interest and solidarity, psychiatric labels and their pation in these Internet activities is driven by a

11.4charland_01. 347 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

348 ■ PPP / VOL. 11, NO. 4 / DECEMBER 2004

normal need for identity that has turned into an Beauchamp, T., and J. F. Childress. 2001. Principles

obsessional craving for identity. Bioethicists and of biomedical ethics, 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford Uni-

the relevant health professions need to start pay- versity Press.

Chambers, T. 2004. Virtual disability: Nobody knows

ing more attention to these disturbing develop-

you’re not a sick puppy on the Internet. In Cultural

ments. However, there are important obstacles. sutures: Medicine, morals and media, ed. L. Fried-

One is securing evidence and doing so according man, 386-398. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

to acceptable ethical standards of research. The Charland, L. C. 2004. Moral treatment and the per-

other problem is autonomy. Unleashed by the sonality disorders. In The philosophy of psychia-

Internet, the prospects for autonomy continue to try: A companion, ed. J. Radden, 64–77. Oxford:

expand as the boundaries of self-determination Oxford University Press.

Chodoff, P. 1999. Misuse and abuse of psychiatry: An

expand. The examples I have discussed show

overview. In Psychiatric ethics, ed. S. Bloch, P.

that in such a context the search for identity may Chodoff, and S. Green, 3rd ed., 49–67. Oxford:

slip into a dangerous madness of its own. Most Oxford University Press.

disturbing is that we may be ethically powerless DeGrazia, D. 2000. Prozac, enhancement, and self-

to stop this, because it is under the banner of creation. Hastings Center Report 30:34–40.

autonomy that identity is sought. Ironically, and Duberman, M. 2002. Cures: A gay man’s odyssey,

tragically, autonomy may now be poised to de- 10th ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Edwards, J. C. 2000. Passion, activity, and “The Care

vour its young; a new generation of vulnerable,

of the Self.” Hastings Center Report 30:31–34.

self-determining, psychiatric “survivors” mad for

Elliot, C. 2000a. Pursued by happiness and beaten

identity, sometimes at any price. senseless. Hastings Center Report 30:7–12.

———. 2000b. A new way to be mad? The Atlantic

Acknowledgments Monthly December:72–84.

I thank the Institute for Advanced Study in ———. 2003. Better than well: American medicine

meets the American dream. New York: Norton.

Princeton, New Jersey, for providing me with the

Frame, J. 1985. An autobiography. The envoy from

financial means and an ideal location to write

mirror city. New York: George Braziller.

this paper. Special thanks to all my colleagues in Feldman, M. D. 2000. Munchausen by Internet: De-

the “Bioethics Group” in the School of Social tecting factitious illness and crisis on the Internet.

Science, who provided comments and encour- Southern Medical Journal 93, no. 7:93–97.

agement during the preparation of the manu- Goffman, I. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the management

script. The paper is dedicated to B, who first led of a spoiled identity. New York: Simon & Shuster.

me into this maze. Goldstein, J. 2001. Console and classify: The French

psychiatric profession in the nineteenth century.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

References Gross, R., M. Olfson, M. Gameroff, S. Shea, A. Feder,

Antai-Otong, D. 2003. Treatments considerations for M. Fuentes, R. Lantigua, and M. M. Weisman.

the patient with borderline personality disorder. Nurs- 2002. Borderline personality disorder in primary

ing Clinics of North America 38, no. 1:101–109. care. Archives of Internal Medicine 162:53–60.

American Psychiatric Association. 1952. Diagnostic Hacking, I. 1995. Rewriting the soul: Multiple per-

and statistical manual of mental disorders, 2nd ed. sonality and the sciences of memory. Cambridge,

Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Associa- MA: Harvard University Press.

tion. ———. 1998. Mad travelers: Reflections on the reali-

———. 1973. Homosexuality and sexual orientation ty of transient mental illness. Charlottesville: Uni-

disturbance: Proposed change in DSM-II, 6th print- versity of Virginia Press.

ing. Position statement. Washington, D.C.: Ameri- ———. 1999. The social construction of what? Cam-

can Psychiatric Association. bridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

———. 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual of Healy, D. 1993. Images of trauma: From hysteria to

mental disorders, 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: Amer- post traumatic stress disorder. London: Faber &

ican Psychiatric Association. Faber.

———. 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of ———. 2002. The creation of psychopharmacology.

mental disorders, 4th ed—Text Revision. Washing- Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

ton, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

11.4charland_01. 348 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

CHARLAND / A MADNESS FOR IDENTITY ■ 349

Keamer, P.D. 2000. The valorization of sadness: Alien- Radden, J. 1996. Divided minds and successive selves:

ation and the melancholic temperament. Hastings Ethical issues in disorders of identity and personal-

Center Report 30:13–18. ity. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Kuhn, T. 1962. The structure of scientific revolutions. Reaves, J. 2001. Anorexia goes high-tech. Time on-

Chicago: University of Chicago Press. line edition. Special Feature: Science and Health.

Lemert, E. 1972. Human deviance, social problems, July 31, 2001. Available: http://time.com/time/

and social control, 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: health/article/0,8559,169660.html.

Prentice-Hall. Scheff, T. J. 1966. Being mentally ill: A sociological

Livesley, J. 2003. Practical management of personali- theory. Chicago: Aldine.

ty disorder. New York: Guilford Press. Schmitt, K. 2004. Sound off: The poison of “Pro-

Livesley, J. W., and K. L. Lang. 2000. Toward an Ana” web sites. Sex, ETC: A Web Site by Teens for

empirically based classification of personality dis- Teens. Posted 02-24-2004 at Sexetc.org.

order. Journal of Personality Disorders 14, no. Scull, A. 1993. The most solitary of afflictions: Mad-

2:137–151. ness and society in Britain, 1700–1900. New Ha-

Loughrey, L., J. P. Jackson, and J. Wobbleton. 1997. ven, CT: Yale University Press.

Patient self-mutilation: When nursing becomes a Shorter, E. 1997. A short history of psychiatry: From

nightmare. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & the era of the asylum to the age of Prozac. New

Mental Health Services, 35, no. 4:30–34. York: Wiley.

Merskey, H. 1992. The manufacture of personalities: Showalter, E. 1986. The female malady. New York:

The production of multiple personality disorder. Pantheon.

British Journal of Psychiatry 160:327–340. ———. 1997. Hystories hysterical epidemics and mod-

———. 1995. The analysis of hysteria: Understand- ern media. New York: Columbia University Press.

ing conversion and dissociation, 2nd ed. London: Slavney, P. R. 1990. Perspectives on hysteria. Balti-

Gaskell. more, Md: The John Hopkins University Press.

Merskey, H., and B. Shafran. 1986. Political hazards Szasz, T. 1970. The manufacture of madness. New

in the diagnosis of “sluggish schizophrenia.” Brit- York: Harper & Row.

ish Journal of Psychiatry 148:247–256. Turkle, S. 1995. Life on the screen: Identity in the age

Moynihan, R. 2003. The making of a disease: Female of the Internet. New York: Simon & Shuster.

sexual dysfunction. British Medical Journal 326:45– Udovitch, M. 2002, September 8. A secret society of

47. the starving. The New York Times, late edition,

Porter, R. 1987. Mind-forg’d manacles: A history of final. Sec. 6, p. 18.

madness in England from the restoration to the Yellowlees, P. M. 2000. The future of Australian psy-

regency. London: Athalone Press. chiatrists: Online or out of touch? Australian and

Putnam, R. D. 2000. Bowling alone: The collapse and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 34:553–559.

revival of the American community. New York:

Simon & Shuster.

11.4charland_01. 349 4/7/05, 12:29 PM

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Manual For Artist Training in Arts and AgingДокумент242 страницыManual For Artist Training in Arts and AgingbezdumniiОценок пока нет

- Videbeck - Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing - NewДокумент27 страницVidebeck - Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing - NewJohnrey Tesoro0% (1)

- Mindfulness Based Cognitive TherapyДокумент2 страницыMindfulness Based Cognitive TherapyDhia Aini FatimahОценок пока нет

- A Tale of One City - Piotrków TrybunalskiДокумент386 страницA Tale of One City - Piotrków TrybunalskiAndaluzОценок пока нет

- On Bion's Couch..Документ16 страницOn Bion's Couch..AndaluzОценок пока нет

- Heidegger's NarcissismДокумент10 страницHeidegger's NarcissismAndaluzОценок пока нет

- 10EurJHealthL239 (1) NysДокумент18 страниц10EurJHealthL239 (1) NysAndaluzОценок пока нет

- Descartes BabyДокумент5 страницDescartes BabyAndaluzОценок пока нет

- A Sumerian Reader (Studia Pohl) - 2nd EditionДокумент65 страницA Sumerian Reader (Studia Pohl) - 2nd EditionAndaluzОценок пока нет

- What It Means Being Goth - A PHD On Dark Matter and Even Darker EnergyДокумент230 страницWhat It Means Being Goth - A PHD On Dark Matter and Even Darker EnergyAndaluzОценок пока нет

- Is Path WarmДокумент2 страницыIs Path WarmDANIELОценок пока нет

- Bordwell Jenna Design Thesis 2020Документ106 страницBordwell Jenna Design Thesis 2020Ashish MakhijaОценок пока нет

- Understandind The Links Between Social Media and DepressionДокумент7 страницUnderstandind The Links Between Social Media and DepressionSydney Frances AntiojoОценок пока нет

- Text-A-Tip Launch Deerfield Highland ParkДокумент2 страницыText-A-Tip Launch Deerfield Highland Parkapi-214331805Оценок пока нет

- EMDR Training For Therapists, Counsellors, Psychologists - EMDR WorksДокумент10 страницEMDR Training For Therapists, Counsellors, Psychologists - EMDR WorksEMDR WorksОценок пока нет

- Psychopathology of DepressionДокумент3 страницыPsychopathology of DepressionAnanyaОценок пока нет

- Counselling Psychology 08Документ20 страницCounselling Psychology 08Saif RahmanОценок пока нет

- Eip Final DraftДокумент10 страницEip Final Draftapi-490105612Оценок пока нет

- A Study On Mental Health and Quality of Work Life Among Teachers Working in Corporate SchoolsДокумент6 страницA Study On Mental Health and Quality of Work Life Among Teachers Working in Corporate SchoolsKannamma ValliОценок пока нет

- Joseph 2000Документ13 страницJoseph 2000Daniel SojuelОценок пока нет

- Forensic PsychiatryДокумент24 страницыForensic PsychiatryDeny Lais100% (1)

- DSM-5 List of Educational and Occupational ProblemsДокумент3 страницыDSM-5 List of Educational and Occupational ProblemsMattОценок пока нет

- Ron Villano Speaking EngagementsДокумент1 страницаRon Villano Speaking EngagementsRonVillanoОценок пока нет

- Concept Mapping The Client's Perspective On Counseling Alliance FormationДокумент10 страницConcept Mapping The Client's Perspective On Counseling Alliance FormationJose Antonio Jibaja CuadrosОценок пока нет

- (Use " " To Indicate Your Answer": Been Bothered by The Following Problems?Документ3 страницы(Use " " To Indicate Your Answer": Been Bothered by The Following Problems?Sakshi PokhriyalОценок пока нет

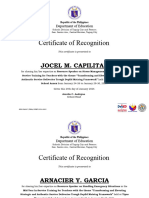

- Certificate of Recognition TemplateДокумент4 страницыCertificate of Recognition TemplateXC Mae VeranoОценок пока нет

- What Is ADHDДокумент6 страницWhat Is ADHDIbnul MubarokОценок пока нет

- The Unaware Therapist Is Considered Unhelpful To Himself and ClientsДокумент7 страницThe Unaware Therapist Is Considered Unhelpful To Himself and ClientsBella Livi100% (1)

- KuesionerДокумент121 страницаKuesionerAlpascaFirdaus100% (1)

- The Effects of Volunteering On The VolunteerДокумент23 страницыThe Effects of Volunteering On The VolunteerInactiveAccountОценок пока нет

- 05 N044 6967Документ16 страниц05 N044 6967Evangelin MelvinОценок пока нет

- 86ba PDFДокумент298 страниц86ba PDFKanesti KamajayaОценок пока нет

- Treatment of Anxiety DisordersДокумент16 страницTreatment of Anxiety DisordersNabilaa MaidinОценок пока нет

- Psychiatric HistoryДокумент6 страницPsychiatric HistoryAlfonso PlantillaОценок пока нет

- Traumatic War Neuorosis: Egyptian ExperienceДокумент5 страницTraumatic War Neuorosis: Egyptian ExperiencemoftasaОценок пока нет

- Issues Surrounding Reliability and Validity-1Документ38 страницIssues Surrounding Reliability and Validity-1kylieverОценок пока нет

- Coping With Stress in Middle and Late AdolescenceДокумент2 страницыCoping With Stress in Middle and Late Adolescencejian.ryccОценок пока нет