Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Clinical: Nerve Injuries After Dental Injection: A Review of The Literature

Загружено:

Alex DaniciОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Clinical: Nerve Injuries After Dental Injection: A Review of The Literature

Загружено:

Alex DaniciАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Clinical PRACTICE

Nerve Injuries after Dental Injection:

A Review of the Literature

Contact Author

Miller H. Smith, BMedSc, DDS; Kevin E. Lung, BSc, DDS, MSc, FRCD(C)

Dr. Lung

Email:

k.lung@kingswayos.com

ABSTRACT

Prolonged and possibly permanent change in sensation due to nerve damage can occur

after dental injections. Although the condition is rare, many practitioners will see this

form of nerve injury during their careers. The exact mechanism of the injury has yet to be

determined, and little can be done to prevent its occurrence. This type of injury carries

with it many functional and psychological implications, and referral to both dental and

medical specialists may be necessary for continued follow-up and possible treatment.

© J Can Dent Assoc 2006; 72(6):559–64

MeSH Key Words: anesthesia, dental/adverse effects; mandibular nerve/injuries; nerve block/adverse This article has been peer reviewed.

effects; sensation disorders/etiology

temporary reduction in sensations, (Fig. 1). The nerve fibres are grouped into fas-

A notably nociception (pain), during

dental procedures can drastically reduce

anxiety in the dental workplace and decrease

cicles surrounded by a connective tissue layer

called the perineurium. This perineurial layer

helps to support, protect and sustain the indi-

patients’ negative experiences.1 Yet regardless vidual nerve fibres.12–15 The outer layer, the

of how beneficial a health care procedure may epineurium, protects the underlying fascicles

be, there are always associated disadvantages by resisting tensile and compressive forces.

and risks.2 Incomplete anesthesia, hematoma This layer is composed of connective tissue,

formation, broken needles, trismus, infection, lymphatic vessels and nutrient vessels (the vasa

toxic reactions and allergic responses, nervorum).16 A loose areolar connective tissue

including anaphylaxis, are all potential prob- layer, the mesoneurium, surrounds the

lems with dental injections.3,4 Another docu- epineurium and provides the nerve with a seg-

mented complication after injection of local mental blood supply.12–15 If any of these extra-

anesthetic in the dental setting is prolonged neural tissues are disrupted, a sensory

and possibly permanent alteration of sensation disturbance may result because of interrupted

over the areas supplied by the involved neural transmission.15

nerve(s).3–11 Local anesthetics for use in dentistry are

designed to prevent sensory impulses from

Neural Anatomy being transmitted from specific intraoral and

Each peripheral nerve fibre is surrounded extraoral areas to the central nervous system,

by a basal lamina, collagen fibres and with minimal effect on muscular tone.1

endoneurial capillaries, which together form Nerve injuries after either supraperiosteal

the endoneurial connective tissue layer12–15 or proximal block injections can affect

JCDA • www.cda-adc.ca/jcda • July/August 2006, Vol. 72, No. 6 • 559

––– Lung –––

Sunderland12 classification systems categorize this type of

injury as axonotmesis or second- or third-degree nerve

injury, respectively.

Given the number of neurons and the thickness of

the connective tissue layers, the lingual nerve averages

1.86 mm in diameter and the inferior alveolar nerve

between 2 and 3 mm in diameter,8,11 but the diameter of

the largest needle (25-gauge) used in dentistry is a mere

0.45 mm. Although any number of fascicles may be

injured by direct needle trauma, causing transient paresis,

it is believed to be impossible for the needle to shear all

nerve fibres and connective tissue layers as in neurotmesis

(Seddon classification) or fifth-degree injury (Sunderland

classification).8,10,11

Figure 1: Diagram of peripheral nerve anatomy and

individual connective tissue components. Hematoma Formation

Several researchers have hypothesized that the needle

may traumatize the intraneural blood vessels, creating an

intraneural hematoma.5,8,11,19,20 Hemorrhage from the

mechanoreception (touch, pressure and position), ther- epineurial blood vessels would give rise to constrictive

moreception (hot and cold) and nociception (pain).8,15,17 epineuritis, compressing the nerve fibres within the rigid

In some instances taste sensation may be altered as well.8 tissue confines and causing localized neurotoxicity.5,19 The

damage could be extensive a mere 30 minutes after the

Mechanisms

injection.11 The release of blood and blood products from

The exact mechanism of injury is still a subject of

the epineurial blood vessels into the epineurium during

debate but a number of theories have been proposed.5

hematoma formation would lead to reactive fibrosis and

Direct Trauma from the Injection Needle scar formation, applying pressure to and inhibiting the

One of the oldest theories is that the needle contacts natural healing of the nerve.5,8–10

the nerve directly, thereby traumatizing the nerve and pro- Depending on the amount of pressure elicited by the

ducing a prolonged change in sensation. This could hematoma, the injury could be classified as neurapraxia

explain why the lingual nerve, which is only 3 to 5 mm (Seddon classification) or first-degree injury (Sunderland)

from the mucosa and the intraoral landmark for or as axonotmesis (Seddon) or second-degree injury

mandibular nerve block, the pterygomandibular raphe, is (Sunderland). The former is characterized by focal block

most commonly involved (more than 70% of cases).1–3,5 of neural impulses with maintenance of axonal and con-

When the mouth is open, the lingual nerve is held taut nective tissue continuity.10,12–14,19 Recovery occurs over

within the interpterygoid fascia, and because of its fixa- several weeks with the release of pressure and subsequent

tion, it cannot be deflected away by the needle.3,5,10,11 remyelinization.14 The latter is more severe, with variable

However, this nerve may be penetrated initially and fur- amounts of axonal and endoneurial discontinuity and

ther damaged upon localization of the lingula by needle ensuing wallerian degeneration.10,12,14,15 The proximal seg-

orientation.18 ment attempts neurotization, and nerve sprouts can grow

In correct execution of the mandibular block tech- as much as 1 to 2 mm per day to span the gap created by

nique, the practitioner contacts bone to ensure proper the injury.12,14,15 The surviving Schwann cells and the

deposition of the local anesthetic.1 A long bevelled needle empty endoneurial tubes attempt to guide the nerve

is often used to create less severe tissue and nerve damage regeneration and to provide the axon with metabolites for

on insertion, but the tip of these needles is much more growth.15

prone to becoming barbed when contacting the bone or

when used for multiple injections.5 In one study, 78% of Neurotoxicity of Local Anesthetic

the long bevelled needles used for conventional More recent speculation suggests that the anesthetic

mandibular block appeared to be barbed at their tips after itself causes localized chemical damage to the nerve, if it is

the procedure, regardless of bevel placement.19 More than injected intrafascicularly or becomes deposited within the

two-thirds of these needles displayed the more dangerous nerve as the needle is withdrawn.5,21,22 It has been hypoth-

outward facing barb.19 These barbs can rupture the per- esized that aromatic alcohols are produced in the area sur-

ineurium, herniate the endoneurium and cause transec- rounding the nerves as a result of altered local metabolism

tion of multiple nerve fibres and even entire fascicles, of the anesthetic.8,11 The presence in the anesthetic or on

especially on withdrawal. 8,19,20 The Seddon 13 and the needle of alcohols and sterilizing solutions, which were

560 JCDA • www.cda-adc.ca/jcda • July/August 2006, Vol. 72, No. 6 •

––– Nerve Injuries–––

used in the past, has previously been blamed for nerve sensation,10,11 though this estimate may be high. Only 57%

injuries.3,8,20,22 Chemical trauma has been shown to cause of the patients who experience prolonged altered sensa-

demyelination, axonal degeneration and inflammation of tion also experienced an electric shock sensation

the surrounding nerve fibres within the fascicles.23 As a or painful injection at the time of anesthetic delivery.5

result, the nerve–blood barrier breaks down, and When estimating the incidence of nerve injury after

endoneurial edema follows. One group of authors hypoth- dental injection, only noninvasive dental procedures

esized that this edema causes ischemia, which is followed should be included; in the case of a surgical procedure, it

by an attempt by the nerve to heal. During this period of must be assumed that the surgery is the cause of any nerve

reperfusion, reactive free radicals can cause cytotoxic injury.5 The most commonly involved nerve is the lingual

injury to the nerve.23 nerve (tongue) and it accounts for more than two-thirds

In some studies, the anesthetics prilocaine and of the cases in the literature; the inferior alveolar nerve

articaine have caused more injuries per use than (lip and chin), including the mental nerve, accounts

lidocaine.5,7,8 Both of these anesthetics are supplied at for less then one-third of the injuries, with the chorda

higher concentrations,8 which will (after metabolism) tympani (taste) being involved minimally.5,8 Although

produce greater levels of toxic metabolites.23,24 At higher extremely rare, altered sensation in the maxilla can also

concentrations, lidocaine has also been shown to cause result from anesthetic injections. 8 Early estimates

neurotoxic damage following both perineural and predicted the likelihood of such a complication as 1 in

intrafascicular injection.11,24 785,000 injections.8 More recently, another author approx-

Incidence of Injury imated this number at between 1 in 160,571 and 1 in

It has become apparent that the injection of local anes- 26,762 mandibular blocks;5 this increase in incidence was

thetic can produce prolonged or permanent alteration of attributed to increased awareness through recent publica-

sensation along part or all of the distribution of either the tions and greater use of potentially neurotoxic anes-

maxillary (V2) or mandibular (V3) branches of the trigem- thetics. 5,26 Using this most recent estimate, we can

inal nerve.5,11 These altered sensations can be categorized extrapolate that the average full-time dentist should

as anesthesias, paresthesias or dysesthesias.14,21 Anesthesias expect to have 1 or 2 nonsurgical patients affected by this

represent the total absence of sensation, including pain. postinjection complication.5

Paresthesias encompass a broader category of abnormal Two-thirds of patients with permanent nerve involve-

sensations, such as “pins and needles,” which may not be ment experience anesthesia or paresthesia, whereas one-

unpleasant. Dysesthesias represent a form of spontaneous third experience dysesthesias, which have much greater

or mechanically evoked painful neuropathy. This category social and psychological impacts. 5,8,27 For reasons

can encompass hyperalgesia (a rapid and exaggerated unknown, dysesthesias occur at higher frequency after

painful response to nonpainful stimuli), hyperpathia dental injections (34%) than after surgery (8%).5,7 In com-

(a delayed and prolonged pain response), sympathetic parison to those who underwent surgical procedures,

mediated pain (pain that is worsened by increasing patients who experienced nerve damage after minor dental

sympathetic tone) and anesthesia dolorosa (pain in procedures felt more disabled.7 Perhaps patients under-

an area of anesthesia).14,21 going surgical treatment are better informed of the risks

It is well known that an electric shock sensation, with beforehand.

subsequent immediate anesthesia, can occur when a

patient undergoes inferior alveolar, lingual or mental Sensory Testing

nerve block. This unwelcome shock sensation is believed In most sensory testing, the entire distribution of the

to occur when the needle contacts part of the nerve affected nerve seems to be involved, rather than a small

trunk.21 The incidence of this sensation has been esti- number of fascicles.5,11 It has been estimated that the infe-

mated at between 1.3% to 8% of all mandibular block rior alveolar and lingual nerves contain between 7,000 and

injections, depending on the sample size. 4–6,10,11,25 12,000 axons in various fascicular arrangements.15 In one

Numerous studies have demonstrated that an electric recent study, the lingual nerve of 33% of patients con-

shock sensation is not indicative of permanent nerve tained a single fascicle at the level of the lingula.28 More

injury, even though damage to the nerve may occur distally, in the third molar region, the lingual nerve may

because of needle contact.11 This form of direct trauma contain between 7 and 39 fascicles. The lower number of

heals within 2 weeks in 81% of patients, with no residual proximal fascicles may be the reason for permanent sen-

damage to the nerve.11 Upward of 15% of the patients sory disturbances along the entire distribution of the lin-

who experience electric shock sensations may go on to gual nerve. The inferior alveolar nerve, however, has a

experience further prolonged or even permanent altered minimum of 3 fascicles, which could account for the

JCDA • www.cda-adc.ca/jcda • July/August 2006, Vol. 72, No. 6 • 561

––– Lung –––

a b c

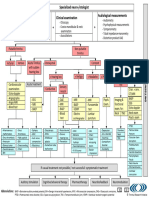

Figure 2: Diagrams for neurosensory assessment. (a) The mental region of V3 can be tested for inferior alveolar and mental nerve injuries.

Note its division into 4 quadrants of approximately equal size. The premaxillary region of V2 can be tested for superior alveolar nerve

injuries. (b) The tongue is divided into sextants on either side of the midline to represent the anterior, middle and posterior thirds of both the

medial and lateral halves. (c) The ventral surface of the tongue and floor of the mouth can be documented in a similar fashion.

ability to regain sensation (through compensatory inner- Prognosis

vation from the uninjured fascicles).28 Patients with nerve injury after dental injection,

Following diagnosis of prolonged altered sensation regardless of the presence or absence of electric shock sen-

caused by dental injection, continued follow-up is sation, have a good prognosis. Spontaneous complete

necessary.9,29 If there is no improvement within 2 weeks, recovery from the altered sensation occurs within 8 weeks

then referral to an oral surgeon or an oral pain specialist is in 85% to 94% of cases.4,5,7,14 The inferior alveolar nerve

advised for a baseline sensory exam.9 It is essential to doc- often carries a more favourable prospect of recovery

ument the mechanism and the date of the initial injury, because of the confines of the bony canal and the lack of

the symptom history, prior treatment and its effect, func- mobility relative to the lingual nerve.7 Patients with pares-

tional deficits (speech and mastication difficulties, tongue thesia lasting beyond 8 weeks after the initial injury have

and cheek biting, taste dysfunction8,27,29) and the presence less chance of full recovery.11,21,29

of any underlying medical disorder (e.g., psychological

problems).9 Altered sensations of either the tongue or the Treatment

mental area can be documented using the diagram shown Few studies have specifically addressed treatment for

in Fig. 2. this type of nerve injury. Both surgical and pharmaceutical

Numerous tests are used to define the extent of the management have been used, with varying suc-

injury; however, these tests are qualitative and highly cess.11,14–16,29,32–39 Patients who experience troublesome

dependent on both the patient’s subjective assessment and prolonged alteration in sensation may be candidates for

the practitioner’s expertise.30 Pinprick testing, which rep- treatment based loosely on the inclusion criteria for nerve

resents pain, is used to map out the area of altered sensa- injuries sustained by surgical procedures. The selection

tion. Von Frey’s hairs are then used to evaluate touch and criteria of some authors include anesthesia for 2 to

pressure sensation. Directional sense is determined using a 3 months with no improvement, paresthesia for 4 to

fine paintbrush, and positional sense using a blunt point. 6 months with no improvement for 2 months or dysesthe-

Static and moving 2-point discrimination can be useful, as sias of minimum duration 2 to 3 months.7 Dysesthesias

can testing of temperature sensation using Minnesota relieved by diagnostic injections of local anesthetic show

thermal disks. The taste sensations of sweet, salt, sour and the most potential to benefit from surgical treatment;

bitter can also be subjectively analyzed.5,9,14,21,30,31 If dyses- however, symptoms may not completely resolve and in

thetic pain is present, then a diagnostic nerve block can be some cases may worsen with invasive surgical investigation

used to determine if the neuropathy is of peripheral or treatment.5,9,14

origin.9,14 Central problems such as anesthesia dolorosa In the rare instance when the microneurosurgeon and

and sympathetic mediated pain will not resolve with local the patient agree on exploratory surgery, variable results

anesthetic.9,21 Some people even advocate electroen- can be achieved with decompression involving external

cephalography, although its usefulness has yet to be deter- and internal neurolysis, excision with direct anastomosis

mined.21 It has been proposed that evaluations should or excision with placement of a nerve graft (including

continue every 2 weeks for 2 months, then every 6 weeks autogenous sural, greater auricular and medial

for 6 months, every 6 months for 2 years and yearly indef- antebrachial nerve grafts,9,14 saphenous vein grafts,35 and

initely if a full recovery has not occurred.21 alloplastic Gore-Tex, collagen and polyglycolic acid

562 JCDA • www.cda-adc.ca/jcda • July/August 2006, Vol. 72, No. 6 •

––– Nerve Injuries –––

tubes9,32). However, most results in the literature reflect 4. Krafft TC, Hickel R. Clinical investigation into the incidence of direct damage

to the lingual nerve caused by local anaesthesia. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1994;

treatment for nerve injuries related to surgical 22(5):294–6.

trauma.11,14–16,29,32–39 Only one study has published results 5. Pogrel MA, Thamby S. Permanent nerve involvement resulting from inferior

alveolar nerve blocks. J Am Dent Assoc 2000; 131(7):901–7.

directly related to a microneurosurgical approach to nerve

6. Lustig JP, Zusman SP. Immediate complications of local anaesthetic adminis-

injuries caused by dental injection; in that study, the tered to 1,007 consecutive patients. J Am Dent Assoc 1999; 130(4):496–9.

overall treatment outcome with exploration and neurol- 7. Pogrel MA, Thamby S. The etiology of altered sensation in the inferior

ysis was poor.5 alveolar, lingual, and mental nerves as a result of dental treatment. J Calif Dent

Assoc 1999; 27(7):531, 534–8.

Long-term nonsurgical pharmacologic therapy has 8. Haas DA, Lennon D. A 21 year retrospective study of reports of paresthesia

also been used for some patients. Medications such as following local anesthetic administration. J Can Dent Assoc 1995; 61(4):319–20,

323–6, 329–30.

anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, phenytoin, gabapentin,

9. Ruggiero SL. Trigeminal nerve injury and repair. N Y State Dent J 1996;

topiramate), benzodiazepines, tricyclic antidepressants, 62(8):36–40.

antispasmodics (e.g., baclofen) and anesthetics (e.g., 10. Harn SD, Durham TM. Incidence of lingual nerve trauma and postinjection

lidocaine)9,11,40 have been shown to benefit patients complications in conventional mandibular block anesthesia. J Am Dent Assoc

1990; 121(4):519–23.

suffering from dysesthesias, especially those that are 11. Pogrel MA, Bryan J, Regezi J. Nerve damage associated with inferior alveolar

sympathetically mediated.9 dental blocks. J Am Dent Assoc 1995; 126(8):1150–5.

12. Sunderland SS. Nerve injuries and their repair. London: Churchill Livingstone;

Conclusions 1991.

13. Seddon SH. Surgical disorders of the peripheral nerves. 2nd ed. London:

Nerve injuries after dental injection are of concern Churchill Livingstone; 1975.

to dentists, as injection of local anesthetic is one of the 14. Colin W, Donoff RB. Restoring sensation after trigeminal nerve injury: a

procedures that dentists perform most frequently. review of current management. J Am Dent Assoc 1992; 123(12):80–5.

Although this form of injury is rare, more patients are 15. Day RH. Diagnosis and treatment of trigeminal nerve injuries. J Calif Dent

Assoc 1994; 22(6):48–51, 53–4.

being referred to dental or medical specialists, who have 16. Assael LA. The nerve under the microscope. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002;

experience in nerve assessment and repair, for follow-up 60(5):483–4.

and possible treatment. Overall, the prognosis is excellent, 17. Campbell RL, Shamaskin RG, Harkins SW. Assessment of recovery from

injury to inferior alveolar and mental nerves. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol

and the vast majority of patients recover during the first 1987; 64(5):519–26.

few weeks. However, the longer the symptoms persist, 18. Hutchings ML. Nerve damage and nerve blocks. J Am Dent Assoc 1996;

the less promising the outcome. Increased awareness 127(1):25.

19. Stacy GC, Hajjar G. Barbed needle and inexplicable paresthesias and trimus

of this form of complication will allow the general practi- after dental regional anaesthesia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994;

tioner to effectively communicate the implications 77(6):585–8.

and prognosis of the altered sensation to affected patients. 20. Crean SJ, Powis A. Neurological complications of local anaesthetics in den-

tistry. Dent Update 1999; 26(8):344–9.

Because anesthetic solutions with elevated concentrations

21. Pogrel MA, Kaban LB. Injuries to the inferior alveolar and lingual nerves.

are implicated in many such injuries, their widespread J Am Dent Assoc 1993; 21(1):50–4.

use may need to be reconsidered by dentists and dental 22. Nickel AA Jr. A retrospective study of paresthesia of the dental alveolar

specialists alike. C nerves. Anesth Prog 1990; 37(1):42–5.

23. Saray A, Apan A, Kisa U. Free radical-induced damage in experimental

peripheral nerve injection injury. J Reconstr Microsurg 2003; 19(6):401–6.

THE AUTHORS 24. Kirihara Y, Saito Y, Sakura S, Hashimoto K, Kishimoto T, Yasui Y. Comparative

neurotoxicity of intrathecal and epidural lidocaine in rats. Anesthesiology 2003;

99(4):961–8.

Dr. Smith is a third-year resident in the department of oral and 25. Takasugi Y, Furuya H, Moriya K, Okamoto Y. Clinical evaluation of inferior

maxillofacial surgery, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, alveolar nerve block by injection into the pterygomandibular space anterior to

Michigan. the mandibular foramen. Anesth Prog 2000; 47(4):125–9.

26. Haas DA, Lennon D. Local anesthetic use by dentists in Ontario. J Am Dent

Assoc 1995; 61(4):297–304.

27. Sandstedt P, Sorensen S. Neurosensory disturbances of the trigeminal nerve:

Dr. Lung is clinical associate professor in the department of a long-term follow-up of traumatic injuries. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1995;

medicine and dentistry, University of Alberta, Edmonton, 53(5):498–505.

Alberta. He is also in private practice at Kingsway Oral Surgery 28. Pogrel MA, Schmidt BL, Sambajon V, Jordan RC. Lingual nerve damage due

in Edmonton. to inferior alveolar nerve blocks: a possible explanation. J Am Dent Assoc 2003;

134(2):195–9.

Correspondence to: Dr. Kevin Lung, Suite 107E, 14310-111 Ave., Main 29. Zuniga JR, Labanc JP. Advances in microsurgical nerve repair. J Oral

Floor, Coronation Plaza, Edmonton, AB T5M 3Z7. Maxillofac Surg 1993; 51(1 Suppl 1):62–8.

30. Gratt BM, Shetty V, Saiar M, Sickles EA. Electronic thermography for the

The authors have no declared financial interests. assessment of inferior alveolar nerve deficit. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral

Radiol Endod 1995; 80(2):153–60.

31. Robinson PP. Observations on the recovery of sensation following inferior

References alveolar nerve injuries. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1988; 26(3):177–89.

1. Malamed SF. Handbook of local anesthesia. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997. 32. Pogrel MA. The results of microneurosurgery of the inferior alveolar and lin-

2. Blanton PL, Roda RS. The anatomy of local anaesthesia. J Calif Dent Assoc gual nerve. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2002; 60(5):485–9.

1995; 23(4):55–58, 60–2, 64–5. 33. Robinson PP, Loescher AR, Smith KG. A prospective, quantitative study on

3. Kramer HS Jr, Mitton VA. Complication of local anaesthesia. Dent Clin the clinical outcome of lingual nerve repair. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000;

North Amer 1973; 17(3):443–60. 38(4):255–63.

JCDA • www.cda-adc.ca/jcda • July/August 2006, Vol. 72, No. 6 • 563

––– Lung –––

34. Joshi A, Rood JP. External neurolysis of the lingual nerve. Int J Oral Maxillofac

Surg 2002; 31(1):40–3.

35. Pogrel MA, Maghen A. The use of autogenous vein grafts for inferior alve-

olar and lingual nerve reconstruction.discussion 988–93. J Oral Maxillofac Surg

2001; 59(9):985–8;

36. Pogrel MA, McDonald AR, Kaban LB. Gore-Tex tubing as a conduit for repair

of lingual and inferior alveolar nerve continuity defects: a preliminary report.

J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998; 56(3):319–21.

37. Robinson PP, Smith KG. A study on the efficacy of late lingual nerve repair.

Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996; 34(1):96–103.

38. Scrivani SJ, Moses M, Donoff RB, Kaban LB. Taste perception after lingual

nerve repair. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000; 58(1):3–5.

39. Zuniga JR, Meyer RA, Gregg JM, Miloro M, Davis LF. The accuracy of clinical

neurosensory testing for nerve injury diagnosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998;

56(1):2–8.

40. Graff-Radford SB, Evans RW.Lingual nerve injury. Headache 2003;

43(9):975–83.

DioGuardi

p/u June 2006 p.425

Eng only 4/C

JOURNAL OF THE CANADIAN DENTAL ASSOCIATION

JCDA www.cda-adc.ca/jcda

Policy on Advertising

It is important for readers to remember that the Canadian

Dental Association (CDA) does not endorse any product or ser-

vice advertised in the publication or in its delivery bag.

Furthermore, CDA is in no position to make legitimizing judg-

ments about the contents of any advertised course. The primary

criterion used in determining acceptability is whether the

providers have been given the ADA CERP or AGD PACE stamp

of approval.

John O’Keefe

1-800-267-6354 ext. 2297

jokeefe@cda-adc.ca

564 JCDA • www.cda-adc.ca/jcda • July/August 2006, Vol. 72, No. 6 •

Вам также может понравиться

- Intralipid infusion for Myelin Sheath Repair in Multiple Sclerosis and Trigeminal Neuralgia?От EverandIntralipid infusion for Myelin Sheath Repair in Multiple Sclerosis and Trigeminal Neuralgia?Оценок пока нет

- Trauma: Radial Nerve PalsyДокумент9 страницTrauma: Radial Nerve PalsyKristina DewiОценок пока нет

- Microsurgical Repir of IANДокумент9 страницMicrosurgical Repir of IANbabukanchaОценок пока нет

- Brain-Computer Interface Technologies: Accelerating Neuro-Technology for Human BenefitОт EverandBrain-Computer Interface Technologies: Accelerating Neuro-Technology for Human BenefitОценок пока нет

- Radial Nerve PalsyДокумент10 страницRadial Nerve Palsycemm_11Оценок пока нет

- Nihms 679297Документ21 страницаNihms 679297Irina HreniucОценок пока нет

- Pain Management After Nerve InjuryДокумент10 страницPain Management After Nerve Injurydr.priteshkumarjainОценок пока нет

- Median, Ulnar and Radial Nerve Injuries: University of Baghdad Al-Kindy College of Medicine Fifth Stage / Group AДокумент13 страницMedian, Ulnar and Radial Nerve Injuries: University of Baghdad Al-Kindy College of Medicine Fifth Stage / Group ANoor Al Zahraa AliОценок пока нет

- Peripheral Nerve Injury and Repair: Adam Osbourne, 5th Year MedicineДокумент5 страницPeripheral Nerve Injury and Repair: Adam Osbourne, 5th Year Medicineayrahma29Оценок пока нет

- Peripheral Nerve Injury, Scarring, and Recovery: Connective Tissue ResearchДокумент8 страницPeripheral Nerve Injury, Scarring, and Recovery: Connective Tissue ResearchJhon Fredy Castañeda LopezОценок пока нет

- Focal Peripheral NeuropathiesДокумент6 страницFocal Peripheral NeuropathiesSeptia P. Mayasari100% (1)

- Axillary Nerve PalsyДокумент11 страницAxillary Nerve Palsyksaurabh027Оценок пока нет

- Peripheral Nerve Entrapment Hydrodissection and Neural Regenerative Strategies Andrea Trescot 2015 PDFДокумент9 страницPeripheral Nerve Entrapment Hydrodissection and Neural Regenerative Strategies Andrea Trescot 2015 PDFAngela PagliusoОценок пока нет

- Peripheral Nerve Injury and Myelination: Potential Therapeutic StrategiesДокумент16 страницPeripheral Nerve Injury and Myelination: Potential Therapeutic StrategiesJhon Fredy Castañeda LopezОценок пока нет

- NeuroradiologyCurrent and Future Imaging of The Peripheral NervoussystemДокумент10 страницNeuroradiologyCurrent and Future Imaging of The Peripheral NervoussystemRyanОценок пока нет

- Peripheral Nerve Injury 2Документ24 страницыPeripheral Nerve Injury 2Gargi MPОценок пока нет

- Nerve Regeneration: Basic and Applied AspectsДокумент7 страницNerve Regeneration: Basic and Applied Aspectsbalab2311Оценок пока нет

- Robinson 2000Документ11 страницRobinson 2000DurgareddyОценок пока нет

- Peripheral Nerve Repair and RegenerationДокумент15 страницPeripheral Nerve Repair and RegenerationjaimeaquilesrinconОценок пока нет

- MB PniДокумент34 страницыMB PniZgama AbdulrahmanОценок пока нет

- Surgery of PeripheralДокумент31 страницаSurgery of PeripheralMircea JunbeiОценок пока нет

- Current Concept in Adult Peripheral Nerve and Brachial Plexus SurgeryДокумент8 страницCurrent Concept in Adult Peripheral Nerve and Brachial Plexus SurgeryJhon Fredy Castañeda LopezОценок пока нет

- Scarano 2017Документ9 страницScarano 2017Lila karla leon villarОценок пока нет

- Peroneal Nerve Palsy PDFДокумент10 страницPeroneal Nerve Palsy PDFChristian Reza WibowoОценок пока нет

- Basic Principles of Peripheral Nerve DisordersДокумент288 страницBasic Principles of Peripheral Nerve DisordersJosé Ramírez100% (1)

- 2016 Nerve Compression Syndromes at The ElbowДокумент8 страниц2016 Nerve Compression Syndromes at The ElbowAbraham Antonio Diaz TorresОценок пока нет

- Nerve InjuryДокумент7 страницNerve Injuryzwecker4458Оценок пока нет

- PATH - Cellular Injury of Nervous SystemДокумент9 страницPATH - Cellular Injury of Nervous SystemebizchatgptОценок пока нет

- Inferior Alveolar Nerve Injury in Implant Dentistry: Diagnosis, Causes, Prevention, and ManagementДокумент7 страницInferior Alveolar Nerve Injury in Implant Dentistry: Diagnosis, Causes, Prevention, and ManagementmaxОценок пока нет

- Complications 1Документ16 страницComplications 1kl;kzОценок пока нет

- IPS ASM 2014 David Andrew PresentationДокумент26 страницIPS ASM 2014 David Andrew PresentationSUMANA ADHIKARYОценок пока нет

- Cranial Nerve InjuryДокумент12 страницCranial Nerve Injurytislm1Оценок пока нет

- Neck Level Algorithmic Approach To TraumaДокумент6 страницNeck Level Algorithmic Approach To TraumaSandra Milena Sepùlveda BastillaОценок пока нет

- Atkins2011 PDFДокумент26 страницAtkins2011 PDFScoalaAuto AutoSorОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Reading Ortho 1Документ6 страницJurnal Reading Ortho 1midellialintinОценок пока нет

- 00002.pdf JsessionidДокумент8 страниц00002.pdf JsessionidSeti Aji HОценок пока нет

- Thopaedic Science: JournalДокумент16 страницThopaedic Science: JournalCiro Madrid FloresОценок пока нет

- Chappell 2020Документ9 страницChappell 2020Deborah SalinasОценок пока нет

- Referat English FixДокумент21 страницаReferat English FixaldybebikaОценок пока нет

- Pathophysiology of Peripheral Nerve InjuryДокумент18 страницPathophysiology of Peripheral Nerve InjuryshreyasОценок пока нет

- Epineurium. If The Nerve Contains More Than One Fascicle, The Epineurium May Be Divided IntoДокумент18 страницEpineurium. If The Nerve Contains More Than One Fascicle, The Epineurium May Be Divided Intoayaanshariq99Оценок пока нет

- UpikДокумент21 страницаUpikaldybebikaОценок пока нет

- Pathophysiology of Peripheral Nerve Injury A Brief ReviewДокумент7 страницPathophysiology of Peripheral Nerve Injury A Brief ReviewChristopher Alexander ToroОценок пока нет

- Peripheral Nerve InjuriesДокумент12 страницPeripheral Nerve InjuriesJiggs LimОценок пока нет

- Tendon Transfers in Foot Drop: Sridhar Krishnamurthy Mohamed IbrahimДокумент9 страницTendon Transfers in Foot Drop: Sridhar Krishnamurthy Mohamed IbrahimHuseyinSahinОценок пока нет

- King's Research Portal: Publisher's PDF, Also Known As Version of RecordДокумент16 страницKing's Research Portal: Publisher's PDF, Also Known As Version of RecordLuis PerezОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S0007091217460132 MainДокумент2 страницы1 s2.0 S0007091217460132 MainHasnaniaОценок пока нет

- Surgery in The DREZ For Refractory Neuropathic Pain After Spinal Cord/Cauda Equina InjuryДокумент2 страницыSurgery in The DREZ For Refractory Neuropathic Pain After Spinal Cord/Cauda Equina InjurystancaОценок пока нет

- Management of Peripheral Nerve Injuries: Basic Principles of Microneurosurgical RepairДокумент11 страницManagement of Peripheral Nerve Injuries: Basic Principles of Microneurosurgical RepairPrasad AilamОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Neuralgia TrigerminalДокумент13 страницJurnal Neuralgia TrigerminallarasatiОценок пока нет

- Spinal Cord Trauma: Pathophysiology, Classi Fication of Spinal Cord Injury Syndromes, Treatment Principles and ControversiesДокумент10 страницSpinal Cord Trauma: Pathophysiology, Classi Fication of Spinal Cord Injury Syndromes, Treatment Principles and ControversiespujiОценок пока нет

- NeuralRegenRes12122106-7412845 020332 PDFДокумент7 страницNeuralRegenRes12122106-7412845 020332 PDFAlvin GfОценок пока нет

- 2021 Anaesth Pain MedДокумент8 страниц2021 Anaesth Pain MedAirwayОценок пока нет

- Peripheral Nerve Trauma: Mechanisms of Injury and RecoveryДокумент44 страницыPeripheral Nerve Trauma: Mechanisms of Injury and RecoveryJa NetОценок пока нет

- Biomaterials and Cells For Neural Tissue EngineeringДокумент60 страницBiomaterials and Cells For Neural Tissue EngineeringYusser olguínОценок пока нет

- 3 2 42 985 PDFДокумент12 страниц3 2 42 985 PDFfebbyОценок пока нет

- PIIS0976566217304800Документ6 страницPIIS0976566217304800Tania salais obregonОценок пока нет

- Neurotoxicity of Local Anesthetics in DentistryДокумент7 страницNeurotoxicity of Local Anesthetics in DentistryVinicíus PavaniОценок пока нет

- An Update On Treatment Modalities For Ulnar NerveДокумент7 страницAn Update On Treatment Modalities For Ulnar Nervekusumaningrum072Оценок пока нет

- Drilling GuidesДокумент1 страницаDrilling GuidesAlex DaniciОценок пока нет

- Biotène Overview Haleon Oral HealthPartnerДокумент1 страницаBiotène Overview Haleon Oral HealthPartnerAlex DaniciОценок пока нет

- Angle's Classification of Malocclusion DentodonticsДокумент1 страницаAngle's Classification of Malocclusion DentodonticsAlex DaniciОценок пока нет

- A Systematic Approach To Full-Mouth Reconstruction of The Severely Worn DentitionДокумент8 страницA Systematic Approach To Full-Mouth Reconstruction of The Severely Worn DentitionAlex DaniciОценок пока нет

- Case #6 Registered Dental Hygienist (RDH) Magazine PDFДокумент1 страницаCase #6 Registered Dental Hygienist (RDH) Magazine PDFAlex DaniciОценок пока нет

- Allergic Manifestation in Oral Cavity. Exudative Polymorphic Erythema. Chronic Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis.Документ38 страницAllergic Manifestation in Oral Cavity. Exudative Polymorphic Erythema. Chronic Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis.Alex DaniciОценок пока нет

- Psychology: (9th Edition) David G. MyersДокумент83 страницыPsychology: (9th Edition) David G. MyersAmber Tuttle DowdyОценок пока нет

- Management of Vertigo - DR - Attiya Rahma SpsДокумент59 страницManagement of Vertigo - DR - Attiya Rahma SpsHenni Pus Vera100% (1)

- 25 PDFДокумент6 страниц25 PDFNirza I. de GonzaloОценок пока нет

- Kinesthetic and Organic SensationДокумент16 страницKinesthetic and Organic SensationNicole Jenne TanОценок пока нет

- Teaching Music To Autistic ChildrenДокумент4 страницыTeaching Music To Autistic ChildrenBárbara de SouzaОценок пока нет

- Straight Leg Raise (SLR) With Sensitizing MovementsДокумент3 страницыStraight Leg Raise (SLR) With Sensitizing Movementssriram gopalОценок пока нет

- Anxiety DisorderДокумент44 страницыAnxiety DisorderKemal AmanoОценок пока нет

- Kelainan Pada Sistem Saraf PeriferДокумент144 страницыKelainan Pada Sistem Saraf PeriferArtika MayandaОценок пока нет

- Human TissueДокумент47 страницHuman TissueAngelo Cadenas75% (4)

- Emotion Perception 2Документ14 страницEmotion Perception 2Juan Camilo Sánchez AriasОценок пока нет

- The Role of Diet and Nutrition On Mental Health and WellbeingДокумент3 страницыThe Role of Diet and Nutrition On Mental Health and WellbeingMeha RajОценок пока нет

- Chemical Sense - TasteДокумент21 страницаChemical Sense - TasteJoe WeahОценок пока нет

- PNF 22 The Effects of PNF and Trunk Stabilization Robot Training On Trunk Stability and Balance in Patients With Chronic StrokeДокумент11 страницPNF 22 The Effects of PNF and Trunk Stabilization Robot Training On Trunk Stability and Balance in Patients With Chronic StrokeAnonymous j0xAgHs3Оценок пока нет

- TRI Tinnitus FlowchartДокумент1 страницаTRI Tinnitus FlowchartAdvocacia VitóriaОценок пока нет

- Homoeopathy (Degree Course) Regulations, 1983Документ72 страницыHomoeopathy (Degree Course) Regulations, 1983Latest Laws TeamОценок пока нет

- Pattern RecognitionДокумент8 страницPattern RecognitionJamie GraceОценок пока нет

- SSILD - By.cosmic - Iron - Cosmic IronДокумент35 страницSSILD - By.cosmic - Iron - Cosmic IronbarnaneОценок пока нет

- Daily Exercises To Strengthen The Vagus Nerve For AnxietyДокумент4 страницыDaily Exercises To Strengthen The Vagus Nerve For AnxietyRoxana MoldovanОценок пока нет

- Chapter 6 AP Psych OutlineДокумент8 страницChapter 6 AP Psych OutlineJenny Gan100% (1)

- Robert Gagne's Instruction Design ModelДокумент3 страницыRobert Gagne's Instruction Design ModelChristopher Pappas100% (3)

- Chorea Continuum 2019Документ35 страницChorea Continuum 2019nicolasОценок пока нет

- Neurotransmitters 2023Документ41 страницаNeurotransmitters 2023Nuhu SibaОценок пока нет

- Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)Документ23 страницыEye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)Monica Istrate100% (1)

- Neuropsychological Assessment of DementiaДокумент44 страницыNeuropsychological Assessment of DementiaAdam Mochtar100% (1)

- 8 Sensation & PerceptionДокумент15 страниц8 Sensation & PerceptiondeudeuvieОценок пока нет

- Neuropathic Pain AssignmentДокумент3 страницыNeuropathic Pain Assignmentbattal eduОценок пока нет

- Clinical Studies:: The Purpose of The ResearchДокумент3 страницыClinical Studies:: The Purpose of The ResearchSpac CatalinaОценок пока нет

- PSY LAB REPORT (Muhaimanul Hoque Fahad)Документ8 страницPSY LAB REPORT (Muhaimanul Hoque Fahad)Muhaimanul Hoque FähädОценок пока нет

- Diazepam (Valium) Drug StudyДокумент1 страницаDiazepam (Valium) Drug StudyEmika Dizon100% (7)

- Physiology of VisionДокумент12 страницPhysiology of VisionAlexis Bondad100% (1)