Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Tolstoy's Christian Non-Resistance

Загружено:

joachimjack100%(1)100% нашли этот документ полезным (1 голос)

155 просмотров3 страницыОригинальное название

Tolstoy’s Christian Non-Resistance.docx

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

100%(1)100% нашли этот документ полезным (1 голос)

155 просмотров3 страницыTolstoy's Christian Non-Resistance

Загружено:

joachimjackАвторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 3

Tolstoy’s Christian Non-Resistance

by David S. D’Amato

Tolstoy’s radical Christianity led him to a pacifistic, anarchistic political

philosophy that rejected the state as incompatible with Christ’s teachings.

Leo Tolstoy is best known as among history’s greatest novelists, authoring monuments of

literary fiction such as War and Peace and Anna Karenina; yet Tolstoy was also a thoughtful and

discerning political thinker, sensitive to the plight of the oppressed and offering deep and

essentially libertarian criticisms of government power. From his Christian beliefs, Tolstoy

arrived at an anarchist political philosophy centered on the conscience of the individual, on the

importance of independent action and moral judgment. For Tolstoy, governments were an

instantiation of human fallibility, their powers necessarily based on the human individual’s

propensity to abuse, subjugate, and enslave his fellow man. Born into aristocratic privilege,

Tolstoy saw firsthand that the landholding nobility were simply glorified freeloaders, living

dissolutely, parasites on the labor of those who tilled the soil, made things with their hands, and

fed people. Tolstoy’s many largely unremembered nonfiction works are a unique blend of

theological, political, and historical arguments. His political theory is inseparable from his

spirituality; both embrace an individualistic stance that emphasizes the rational judgment of each

person. But Tolstoy’s individualism is not egoistic. On the contrary, in his thought, reason

demands a kind of asceticism, his definition of love entailing self-abnegation and renunciation.

To force one to exert his talents in the service of others, however, is to void the virtue in service.

Each individual must decide for himself whether he will heed “rational consciousness” and

dedicate himself to higher values.

Thus is Tolstoy’s Christianity—his adherence to the teachings of Christ—decidedly not a

product of faith, but of reason; rational choice, always guided by reason (as opposed to “the

bestial personality”), is at the center of his thought. Tolstoy’s Christianity was controversial and

explicitly unorthodox. He called “nonsense” traditional Christian tenets such as the divinity of

Jesus, the Trinity, and the idea of salvation through faith. His beliefs are correspondingly anti-

clericalist, based on the idea that “the churches have always been not merely alien but downright

hostile to the teaching of Christ.” For Tolstoy, the various Christian sects as institutions are

necessarily “anti-Christian,” having “yielded to the world” and its evil essence. Also at the center

of Tolstoy’s Christianity is the individual, his spirit, and his conscience, each person enjoying

direct access to God and possessing the ability to understand God’s laws. These laws are not

foreign and arcane mysteries the proper understanding of which requires the mediation of an

exalted few with sacerdotal training. Rather than pursuing spiritual enlightenment and absolution

through ritualistic exercises and the search for the miraculous, Tolstoy believed that Christians

ought to look within—that “the kingdom of God is within you.”

The consequence of Tolstoy’s radically anti-authoritarian creed (for which he was

excommunicated from the Russian Orthodox Church) was a unique, though not entirely

unprecedented, variety of anarchism. This Christian anarchism is redolent of its American

counterpart, the nonresistance philosophy of radical abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison.

Indeed, Garrison’s son wrote to Tolstoy to remark on the similarities between Garrisonian

nonresistance and Tolstoy’s philosophy of peace, appending to his letter the “Declaration of

Non-resistance” (actually “Declaration of Sentiments”) that Garrison had written for his 1838

Peace Convention). In his 1894 tract The Kingdom of God Is Within You, Tolstoy quoted at

length from both the Declaration and from the writings of another notable Christian nonresistant,

Adin Ballou, to whom Tolstoy had written in admiration. Tolstoy followed Garrison and Ballou

in the belief that all human governments were founded on principles contrary to those taught by

Jesus, in particular, those expressed in Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount—the source of the

nonresistance doctrine. For Tolstoy, Jesus’s admonitions to love your enemies and to resist not

evil were “incompatible with violence, which forms an indispensable condition of power.”

Unlike some professed anarchists, then, Tolstoy vehemently opposed violent forms of

propaganda of the deed, denouncing political assassinations and lamenting “the mania for

murder” that dominated his native Russia.

In an article for The Advocate of Peace, Tolstoy defended his philosophy of consistent

nonviolence and argued that “the murder of kings, emperors, and rulers in general is senseless,

since the state organization cannot be altered by such murders.” Tolstoy was, therefore, no

spokesman for revolution, seeing the state itself as the enemy of humankind. He observes that

while the principle of nonresistance “is most terrible and most dangerous for every despotism,”

revolutionaries have throughout history preferred to combat evil with evil, to attempt the

overthrow of power with violence. Tolstoy was similarly skeptical of attempts at practical

political reform. As the eminent libertarian scholar Robert Higgs notes, “The Kingdom of God Is

Within Youcontains many anticipations of ideas later developed in economics and public choice.”

Tolstoy gives no sanctuary to romanticized or idealized notions of the political process. He

writes, “[W]e all know how our laws are made. We have all been behind the scenes, we know

that they are the product of covetousness, trickery, and party struggles; that there is not and

cannot be any real justice in them.” To these unjust, cruel, artificial laws Tolstoy contrasts the

laws of God, which prescribe love and compassion between all members of the human race. For

Tolstoy, there can be no obligation to observe an edict that contradicts this most fundamental

law. If a law offends one’s conscience or conflicts with Christ’s exhortations, he should simply

ignore it, confident in his ability to distinguish right from wrong.

If Tolstoy was influenced by radical thinkers such as Garrison, Ballou, and Henry George, then

his distinctive theory of nonresistance went on to inform the thought of the famed American

lawyer Clarence Darrow, Gandhi, and countless others. Darrow, for his part, credited Tolstoy as

the principal source of the ideas expressed in his remarkable book Resist Not Evil, the preface of

which praises Tolstoy for “plac[ing] the doctrine of non-resistance upon a substantial basis.”

Like Tolstoy, Darrow confronts the argument that nonresistance is simply impractical, a utopian

idea that “can only be held by dreamers and theorists.” And also like Tolstoy, Darrow concludes

that in fact it is the state, founded on false principles of war, conquest, and patriotism, that is

impractical, that has wrought misery for the many throughout history. Though a lawyer, an

officer of the court sworn to uphold the Constitution and defend the judicial system, Darrow

nevertheless insists on the impossibility of a just judgment within the existing legal and political

order. Tolstoy had likewise charged “learned jurists” and prosecutors with perpetuating a

“parody of justice,” with concocting elaborate sophistries to “justify the violence of authority.”

Both Tolstoy and Darrow believed that it was the state, the institutionalization of war and

violence, that was to blame for most of the crimes and injustices in the world. The question of

“how to be without a State” is, Tolstoy argues, directly inverse to the question that ought to drive

our thinking about politics and government. Shifting the burden of proof, we might instead

consider the practical effects of statism and its concomitants. For Tolstoy, then, the state does not

deserve the benefit of the doubt; born of violent conquest, government has remained true to its

brutal, iniquitous pedigree. “The champions of government,” Tolstoy observes, assert that

without it the wicked will oppress and outrage the good, and that the power of the government

enables the good to resist the wicked. But in this assertion the champions of the existing order of

things take for granted the very proposition they want to prove. When they say that except for the

government the bad would oppress the good, they take it for granted that the good are those who

at the present time are in possession of power, and the bad are those who in subjection to it. But

this is just what wants proving.

Nothing is beyond the reach of Tolstoy’s penetrating radicalism, and he reserves especially

scathing critiques for the subjects of war and the “savage superstition” of patriotism. In its

categorical rejection of force and violence as means of ordering and administrating human

society, Tolstoyan nonresistance must be regarded as a form of libertarianism. Outspoken in his

opposition to warfare and militarism, however rationalized, the political writings of Tolstoy’s

late life have often drawn the attention of the censors, beginning with the Russia of his own day

and later in Nazi Germany. Even where they have been freely available, they have reposed in

relative obscurity. But Tolstoy’s sagacious nonfiction has much to teach the contemporary

libertarian, offering a bold indictment of politics itself and testing the platitudes of conventional

wisdom. Tolstoy’s libertarian observations demonstrate that at least as much as it is an ideology

or a political philosophy, anarchism is a temperament: a visceral resistance to authority, a heart

for the enslaved and oppressed, a hatred of war. And this is the manner in which Tolstoy treats

social and economic theory, not as cautious scholar, but as artist, sensitive rather than detached.

Such an approach leads, perhaps, to what Higgs rightly calls a “curiously uneven command of

different aspects of his subject.” On economics, for example, Tolstoy reveals a regrettable, if

pardonable, ignorance, wrongly identifying trade and exchange with exploitation, profit motive

with greed. Like other late nineteenth century anarchists, Tolstoy believed that the problems of

political authority were fundamentally and inextricably connected to those of widespread poverty

and economic exploitation. But he repeatedly confuses coercive economic privilege, which he

rightly condemns, with honest commerce. Still, while Tolstoy could have benefitted from a

lesson in elementary economics, he nevertheless demonstrates an understanding of the fact that it

is state violence against which we must always strive. “Christianity,” he writes, “destroys the

state.” Governmental authority, for Tolstoy, compels us to live a lie or a contradiction, to place

the mere edicts of the powerful and cunning above the dictates of reason and conscience. Love

and mutual respect, once fully understood and acted upon, would replace the criminal

governments of the present with proper communities of equals. The lesson is one that has always

been important to libertarians: The remedy for the political is not this candidate or that reform,

but the simple recognition of the generally applicable moral principle to treat other people as you

would want to be treated, respecting their dignity and autonomy.

Вам также может понравиться

- Tolstoy and NonviolenceДокумент2 страницыTolstoy and NonviolencenorazieglerОценок пока нет

- The Kingdom of God Is Within You (Warbler Classics Annotated Edition)От EverandThe Kingdom of God Is Within You (Warbler Classics Annotated Edition)Оценок пока нет

- The Kingdom of God Is Within You (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading): Christianity Not as a Mystic Religion but as a New Theory of LifeОт EverandThe Kingdom of God Is Within You (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading): Christianity Not as a Mystic Religion but as a New Theory of LifeОценок пока нет

- 2005 - Alexandre J.M. Christoyannopoulos - Leo Tolstoy Ant The 'War On Terror'. A Radical Christian Responce To ViolenceДокумент19 страниц2005 - Alexandre J.M. Christoyannopoulos - Leo Tolstoy Ant The 'War On Terror'. A Radical Christian Responce To Violencebuster301168Оценок пока нет

- (BASEES - Routledge Series On Russian and East European Studies) Alexandre Christoyannopoulos - Tolstoy's Political Thought - Christian Anarcho-Pacifist Iconoclasm Then and Now-Routledge (2019)Документ283 страницы(BASEES - Routledge Series On Russian and East European Studies) Alexandre Christoyannopoulos - Tolstoy's Political Thought - Christian Anarcho-Pacifist Iconoclasm Then and Now-Routledge (2019)Nickolas Martins BittencourtОценок пока нет

- Thoreau's Civil DisobedienceДокумент11 страницThoreau's Civil DisobedienceSteve MahashabdeОценок пока нет

- Thoreau's View on the Relation Between Individual Conscience and the State in Civil DisobedienceДокумент2 страницыThoreau's View on the Relation Between Individual Conscience and the State in Civil DisobediencePollob Ahmed SagorОценок пока нет

- Civil Disobedience Under The Scpoe of Henry David ThoreauДокумент4 страницыCivil Disobedience Under The Scpoe of Henry David ThoreauSankalp RajОценок пока нет

- Realism According ToДокумент7 страницRealism According TodacutananjennobrayanОценок пока нет

- Depopulation of A Planet Thinning Out The Useless Eaters An Unspoken NWO Agenda-MartinДокумент121 страницаDepopulation of A Planet Thinning Out The Useless Eaters An Unspoken NWO Agenda-MartinALBINOCYCLOPS100% (1)

- Leo Tolstoy Government Is Violence Essays On Anarchism and Pacifism 1Документ94 страницыLeo Tolstoy Government Is Violence Essays On Anarchism and Pacifism 1ApostolisXanthos100% (1)

- Leo Tolstoy - The Kingdom Of God Is Within You: “To get rid of an enemy one must love him. ”От EverandLeo Tolstoy - The Kingdom Of God Is Within You: “To get rid of an enemy one must love him. ”Оценок пока нет

- Mccormick Authority BeyondДокумент6 страницMccormick Authority BeyondVth SkhОценок пока нет

- Famous Political ScientistsДокумент16 страницFamous Political ScientistsBainalyn BaludiОценок пока нет

- Sahlins - The Western Illusion of Human NatureДокумент40 страницSahlins - The Western Illusion of Human NatureClarisse Raposo100% (1)

- The Fundamental Similarity Between Monte PDFДокумент7 страницThe Fundamental Similarity Between Monte PDFHuria MalikОценок пока нет

- Treatise On Tolerance by VoltaireДокумент7 страницTreatise On Tolerance by VoltaireJay SaragaОценок пока нет

- Treatise On Tolerance by VoltaireДокумент7 страницTreatise On Tolerance by VoltaireJay SaragaОценок пока нет

- What Is Platos Philosophy of Peace and HДокумент20 страницWhat Is Platos Philosophy of Peace and HPablo Rodríguez AnguloОценок пока нет

- Antony Sutton On Left Versus Right and The Hegelian Dialectic in American PoliticsДокумент4 страницыAntony Sutton On Left Versus Right and The Hegelian Dialectic in American PoliticsskalpsoloОценок пока нет

- On Loyalty, Politics, and Statehood: "Why Not Eat An Eclair?"Документ3 страницыOn Loyalty, Politics, and Statehood: "Why Not Eat An Eclair?"rogernovoОценок пока нет

- Whitman - 'On Anarcho-Monarchism'Документ5 страницWhitman - 'On Anarcho-Monarchism'Kam Ho M. WongОценок пока нет

- Middle-earth and the Return of the Common Good: J. R. R. Tolkien and Political PhilosophyОт EverandMiddle-earth and the Return of the Common Good: J. R. R. Tolkien and Political PhilosophyОценок пока нет

- Socratic EliasДокумент6 страницSocratic EliasElias RoblesОценок пока нет

- Thymotic Politics: Sloterdijk, Strauss and NeoconservatismДокумент37 страницThymotic Politics: Sloterdijk, Strauss and NeoconservatismAnonymous Fwe1mgZОценок пока нет

- Political Thoughts or Beliefs of PhilosophersДокумент5 страницPolitical Thoughts or Beliefs of PhilosophersRonaldОценок пока нет

- What Transcends The Nation?: Max Planck Institute For The Study of Religious and Ethnic DiversityДокумент13 страницWhat Transcends The Nation?: Max Planck Institute For The Study of Religious and Ethnic DiversityDaniel BarbosaОценок пока нет

- 2007 Anthony Long Stoic CommunitarianismДокумент21 страница2007 Anthony Long Stoic CommunitarianismAlice SilvaОценок пока нет

- Woodrow Wilson andДокумент6 страницWoodrow Wilson andsnokcs100% (1)

- Authoritarianism QuotesДокумент5 страницAuthoritarianism QuotesmariafranciscaОценок пока нет

- The Kingdom of God Is Within You: BiographyДокумент2 страницыThe Kingdom of God Is Within You: BiographyspaceisamazingОценок пока нет

- The West and the Rest: Globalization and the Terrorist ThreatОт EverandThe West and the Rest: Globalization and the Terrorist ThreatРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (8)

- Favorite Quotes From AristotleДокумент4 страницыFavorite Quotes From AristotleArsie BryannОценок пока нет

- Islamic Idealogy - For CSSДокумент10 страницIslamic Idealogy - For CSSEngr Hafiz UmairОценок пока нет

- A State Necessity or EnemyДокумент18 страницA State Necessity or Enemyİbrahim RustamovОценок пока нет

- On The Secular State A Response To Mohamad Amer MezianeДокумент8 страницOn The Secular State A Response To Mohamad Amer MezianeaneesОценок пока нет

- Relativism - RaviДокумент4 страницыRelativism - RaviPapa Giorgio100% (2)

- Document 16 PDFДокумент13 страницDocument 16 PDFAnonymous q2cSeL1kОценок пока нет

- Fields of Blood,' by Karen Armstrong - The New York TimesДокумент2 страницыFields of Blood,' by Karen Armstrong - The New York Timesmatee ullahОценок пока нет

- Books: Revisited: Totalitarianism in Our Century Edited IrvingДокумент2 страницыBooks: Revisited: Totalitarianism in Our Century Edited IrvingElton Dias XavierОценок пока нет

- Level 4: Mrxulski 1 Point 5 Days Ago Edited 5 Days AgoДокумент2 страницыLevel 4: Mrxulski 1 Point 5 Days Ago Edited 5 Days AgoYza AlfonsoОценок пока нет

- Antony Sutton Left Versus Right and The Hegelian Dialectic in American PoliticsДокумент3 страницыAntony Sutton Left Versus Right and The Hegelian Dialectic in American PoliticsAndemanОценок пока нет

- Truth St. Thomas AquinasДокумент3 страницыTruth St. Thomas AquinasJohnLorenzdelRosarioОценок пока нет

- Was Adolf Hitler A EurasianistДокумент15 страницWas Adolf Hitler A EurasianistIf We Do NothingОценок пока нет

- A New Race Has Sprung UpДокумент25 страницA New Race Has Sprung UplalalandОценок пока нет

- Phil Final NotesДокумент2 страницыPhil Final NotesShadman JhuhayerОценок пока нет

- Civil Disobedience Key FactsДокумент77 страницCivil Disobedience Key FactsAdman AlifAdmanОценок пока нет

- From Machtpolitik To Power Politics, R. AronДокумент6 страницFrom Machtpolitik To Power Politics, R. AronDimitris PanomitrosОценок пока нет

- Compare The Tones King and Thoreau Carry When Exploring The Flaws in Beliefs And/or Government SystemsДокумент4 страницыCompare The Tones King and Thoreau Carry When Exploring The Flaws in Beliefs And/or Government SystemsElias RoblesОценок пока нет

- Name: Muhammad Yaseen Class:4 B ROLL NO: 18838Документ5 страницName: Muhammad Yaseen Class:4 B ROLL NO: 18838safder aliОценок пока нет

- M M M MMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM MMMMMM MMMM MMMMMMMMM MMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM M M ! MM MMM"MM M MMM#MMMM M MMДокумент8 страницM M M MMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM MMMMMM MMMM MMMMMMMMM MMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM M M ! MM MMM"MM M MMM#MMMM M MMcool_vjk4b9Оценок пока нет

- Gary Ulmen Carl Schmitt and Donoso CortesДокумент11 страницGary Ulmen Carl Schmitt and Donoso Cortescarlos murciaОценок пока нет

- Tolstoy and Gandhi PDFДокумент14 страницTolstoy and Gandhi PDFRaisina ReelsОценок пока нет

- Reflection Paper: AristotleДокумент3 страницыReflection Paper: AristotleJhonmark TemonioОценок пока нет

- Henry Thoreau and Civil DisobedienceДокумент2 страницыHenry Thoreau and Civil DisobedienceAakash0% (1)

- Metrobank List of RequirementsДокумент1 страницаMetrobank List of RequirementsjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- PQF LevelsДокумент2 страницыPQF LevelsjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- POs and PEOsДокумент8 страницPOs and PEOsjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- dc2007-5847 EDCДокумент1 страницаdc2007-5847 EDCjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- Restructuring & Privatization of the Philippine Electric Power SectorДокумент15 страницRestructuring & Privatization of the Philippine Electric Power SectorjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- I. Overview of The Philippine Judicial SystemДокумент6 страницI. Overview of The Philippine Judicial SystemJennie ElardeОценок пока нет

- Republic of The Philippines Legal Education BoardДокумент25 страницRepublic of The Philippines Legal Education BoardPam NolascoОценок пока нет

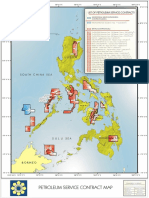

- ChevronДокумент7 страницChevronjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- 802 Phil. 636Документ22 страницы802 Phil. 636Rica Hazel RoallosОценок пока нет

- Tax credit for senior discounts allowed despite lossesДокумент21 страницаTax credit for senior discounts allowed despite lossesGwen Alistaer CanaleОценок пока нет

- Finnis-What Is A LawДокумент7 страницFinnis-What Is A LawjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- SCMAPДокумент1 страницаSCMAPjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- Promotion of Competitive NeutralityДокумент7 страницPromotion of Competitive NeutralityjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- Historical Case Against Roe v. WadeДокумент7 страницHistorical Case Against Roe v. WadejoachimjackОценок пока нет

- PECR Petroleum Area Map FДокумент1 страницаPECR Petroleum Area Map FjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- On The Code of MaragtasДокумент7 страницOn The Code of MaragtasjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- Active Petroleum Contracts RevisedДокумент2 страницыActive Petroleum Contracts RevisedjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- Why Did CJ Roberts Disagree With Overturning Roe V WadeДокумент4 страницыWhy Did CJ Roberts Disagree With Overturning Roe V WadejoachimjackОценок пока нет

- Summa Theologica On LawДокумент2 страницыSumma Theologica On LawjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- Sec Cert - Simlong Energy Increase of Capital Stock 07-13-21Документ1 страницаSec Cert - Simlong Energy Increase of Capital Stock 07-13-21joachimjackОценок пока нет

- Prayer-to-the-Holy-Spirit CMTДокумент2 страницыPrayer-to-the-Holy-Spirit CMTjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- Why Decriminalizing Abortion Is Not Possible in PHДокумент6 страницWhy Decriminalizing Abortion Is Not Possible in PHjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- The Role of History in ScienceДокумент9 страницThe Role of History in SciencejoachimjackОценок пока нет

- On The "Code of Kalantiaw"Документ15 страницOn The "Code of Kalantiaw"joachimjackОценок пока нет

- The Spanish-American War, 1898: MILESTONES: 1866-1898Документ2 страницыThe Spanish-American War, 1898: MILESTONES: 1866-1898joachimjackОценок пока нет

- Dovie Beams and Philippine Politics A PRДокумент42 страницыDovie Beams and Philippine Politics A PRjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- Lon Luvois FullerДокумент4 страницыLon Luvois FullerjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- Archbishop Niederauer On Pelosi's Abortion RemarksДокумент4 страницыArchbishop Niederauer On Pelosi's Abortion RemarksjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- Philippine Historiography and Colonial DДокумент26 страницPhilippine Historiography and Colonial DjoachimjackОценок пока нет

- Asia's Aging Population PDFДокумент14 страницAsia's Aging Population PDFdelap05Оценок пока нет

- Why Were The British Able To Replace The Mughals As The Dominant Force in The SubДокумент2 страницыWhy Were The British Able To Replace The Mughals As The Dominant Force in The SubAasherОценок пока нет

- Missionsw-Contemporary Issues and ChallengesДокумент8 страницMissionsw-Contemporary Issues and ChallengesNirmal100% (2)

- Shivaratri and VatukaДокумент63 страницыShivaratri and VatukaLesОценок пока нет

- The City of The Heart - Yunus Emre's Verses of LoveДокумент157 страницThe City of The Heart - Yunus Emre's Verses of LoveRaahem67% (3)

- Congregavit Nos in Unum Christi AmorДокумент51 страницаCongregavit Nos in Unum Christi Amorrey_sajulanОценок пока нет

- American Dream Exploits WorkersДокумент75 страницAmerican Dream Exploits WorkersrikiОценок пока нет

- 477 TimetableДокумент2 страницы477 TimetablelitchickukОценок пока нет

- Sacrifice and Subjectivity New Historicism 29Документ198 страницSacrifice and Subjectivity New Historicism 29jurbina1844Оценок пока нет

- Brown Eagle: Story About Pow Wow and What To See When You Are ThereДокумент103 страницыBrown Eagle: Story About Pow Wow and What To See When You Are TherelynnОценок пока нет

- SuperstitionДокумент4 страницыSuperstitionMehboob HassanОценок пока нет

- NIV Biblical Theology Study Bible SamplerДокумент87 страницNIV Biblical Theology Study Bible SamplerBible Gateway89% (9)

- Sejarah Peninjau JelebuДокумент11 страницSejarah Peninjau JelebuTengku Puteh Tippi100% (1)

- Johnny Wong Small Group 03 PPДокумент42 страницыJohnny Wong Small Group 03 PPJoshuell K CampbellОценок пока нет

- Norms of Morality Edited 2020 PDFДокумент19 страницNorms of Morality Edited 2020 PDFMeya SabaritaОценок пока нет

- Conze 1959 ScripturesДокумент125 страницConze 1959 Scripturesbodhi86Оценок пока нет

- Fourth Degree Study GuideДокумент7 страницFourth Degree Study GuideJames SchutlzОценок пока нет

- Spiritual Gifts TestДокумент45 страницSpiritual Gifts TestAna SchmidtОценок пока нет

- All Around The WorldДокумент1 страницаAll Around The WorldKhazeJoyDavidОценок пока нет

- 2 Authority and ObligationДокумент8 страниц2 Authority and ObligationKristy LeungОценок пока нет

- Between Contemplation and Distraction PDFДокумент23 страницыBetween Contemplation and Distraction PDFMauricio PiattiОценок пока нет

- Interior Castle Explored - St. Teresa's Teaching On The Life of Deep Union With God - Ruth BurrowsДокумент130 страницInterior Castle Explored - St. Teresa's Teaching On The Life of Deep Union With God - Ruth Burrowsleobooklover86% (7)

- Thesis of Ven PannavamsaДокумент19 страницThesis of Ven Pannavamsasu pannaОценок пока нет

- UntitledДокумент113 страницUntitledamhra ZulfadhliОценок пока нет

- Sacred Flames ReikiДокумент61 страницаSacred Flames ReikiMona Hansen100% (4)

- Sree Lalita Sahasra Namavali in EnglishДокумент27 страницSree Lalita Sahasra Namavali in Englishitell_sri100% (3)

- MAPEH Dept. Head: Mr. Crisanto E. TomasДокумент5 страницMAPEH Dept. Head: Mr. Crisanto E. TomasRosh PilapilОценок пока нет

- Dead StarsДокумент23 страницыDead StarsHannah SyОценок пока нет

- Fiqh Books ListДокумент46 страницFiqh Books ListNabeel0% (1)

- Reconciliation Half Fold EOCsteps2Документ2 страницыReconciliation Half Fold EOCsteps2bils burritoОценок пока нет

- Kosher Court of AppealsДокумент27 страницKosher Court of AppealsFergus BurnsОценок пока нет