Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Autistics

Загружено:

keniakmbАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Autistics

Загружено:

keniakmbАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

AAP Contest Winner

Acoustics

Veronica Hackethal, MSc.

C ecilia stared into her morning coffee. The steam rose

in a lazy spiral from the murky liquid. Cafeteria cof-

fee, she sighed, gazing languidly from her balcony seat to

That was as much as Cecilia could remember. But it

didn’t seem to matter to Mona, who continued to rock

back and forth. “You have a nice voice, Mona,” Cecilia

the hospital entrance below. She sat in early spring sunlight said, trying to sound upbeat. “I bet you could carry a mean

filtered through half-washed windows and ruminated on tune.” But the girl still took no notice, and finally Cecilia

the past year, her third of medical school. It hadn’t been ran out of things to say. For ten minutes, Cecilia didn’t

easy. She had a sensitive soul, and it seemed that the fac- speak. She listened to Mona’s humming and stared mo-

ulty had tried to pound it out of her. “You’re too quiet,” rosely out the hospital window at the golden sunlight shim-

her attendings had scolded, “too gentle. You need to be mering off the waves in the Hudson below.

more aggressive, faster-talking.” More like us is what they What a beautiful child, Cecilia thought. Mona had raven

meant to say. It left her feeling like her character had been hair and velvety black eyes that looked off into the distance

attacked, and she’d grown monumentally discouraged. (but never into anyone else’s) from beneath long curling

Usually Cecilia censored herself from these thoughts— lashes. Her skin, smooth and olive toned, was sallow from

they made her throat knot in anger. She took another sip lack of sunlight, devoid of the rosy cheeks of childhood.

of coffee, tried to ignore its acidic bite, and allowed her Mona did not look unhappy. She simply didn’t care

mind to wander onto the story of a patient she’d just met. about the outside world. But when that noisy world broke

The girl’s name was Mona, a 10-year-old with autism. into her isolation, she exploded in torrents of sound. A

Cecilia, exhausted this morning, had reluctantly walked thunderclap could make her shriek and roll with pain, a

into Mona’s world. “Hi, my name’s Cecilia,” she’d begun, car alarm could precipitate a temper tantrum. She would

“what’s your name?” It was a half-hearted gesture to get clap her hands over her ears trying in vain to expel the

the girl to respond. Mona seemed oblivious. She sat in the intruder. Her parents, defeated by her outbursts, had come

center of her bed, curled into a ball, rocking slowly back to the hospital desperately searching for solutions. “Please

and forth and humming a jumble of barely audible notes. help us,” they’d pleaded, their faces branded with the guilt

There was no melody, only a random assortment of varying of parents stretched beyond endurance, “we can’t live like

pitches sung in a child’s uncertain treble. this any longer.” So Mona had been admitted for “obser-

“I see you like to sing,” Cecilia continued. No response, vation.” All day she sat in bed, rocking back and forth to

only humming and rocking. “I like to sing, too. Do you her own melody.

know that my name’s a song?” Still no response. “Want to As Cecilia sat thinking, Mona’s humming began to in-

hear it?” Cecilia continued, feeling like she was talking to vade her thoughts. Gradually, she realized that the little

herself. Mona continued rocking, wrapped up in her own girl’s melody was not completely random. It was a scale of

musical hodgepodge. “It goes like this,” Cecilia continued. half-steps: three steps forward, two back, four forward,

Bashfully she ventured a few lines: “Ceceeeeelia, you’re three back, in perfect tune. Mona had suffered from au-

breakin’ my heart. You’re shakin’ my confidence, Lately- tism since infancy, Cecilia thought. She’d begun talking

y-y. Oh, Ceceeeelia, I’m down on my knees. I’m beggin

around age two—had learned a rudimentary vocabulary.

you please to come home!”

Then she’d quickly regressed, had lost all verbal ability,

and shut out everyone. Mona hadn’t spoken a word since

Received September 14, 2005; accepted September 20, 2005. Veron- age three. All she did, day in and day out, was hum inces-

ica Hackethal is a fourth-year medical student at Columbia College santly. She’d never been capable of taking music lessons,

of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, New York. Address corre-

spondence to Veronica Hackethal, vh2008@columbia.edu (E-mail). so how could she hum scales?

Copyright 䊚 2006 Academic Psychiatry. Mona’s peculiarities were not entirely foreign to Cecilia,

80 http://ap.psychiatryonline.org Academic Psychiatry, 30:1, January-February 2006

VERONICA HACKETHAL, MSC.

herself highly musical. Her father had said, in the German to Mona. As she sat daydreaming over her coffee, the

accent he found impossible to lose, “You haf ze privilege harsh sounds of the hospital—the rushed, urgent voices

of being named after Saint Sheesheelia, so of course you bouncing off stark linoleum—swirled around Cecilia’s

vill haf ze geeft of music.” But Cecilia had never liked her head. She tried to shut out the sensory stimulation, con-

name. She thought it sounded old-fashioned. “Be proud centrating instead on the sugary coffee in her mouth, the

of your name,” her father had continued unconvincingly, changing cloud patterns outside the window. Cecilia felt

his nasal Rs stuck in the bridge of his nose, “Saint Shee- afraid of Mona. If she identified with Mona’s sound sen-

sheelia was one of ze greatest vomen in heestory.” That sitivities, what did that say about herself? Cecilia could

was another thing. Cecilia never liked the way her father sympathize with Mona’s rejection of the world. There were

pronounced her name. He tried to imitate an Italian ac- times in the last year when she’d wanted to do the same.

cent, out of deference to his Italian wife who’d always Cecilia was tired of feeling. She had turned off her emo-

seemed to him the height of style. Even after she’d gained tions and now wondered whether she dared turn them on

thirty permanent pounds of pregnancy and her feet had again. It was unconscious, a gradual slide into not caring.

widened so that she could no longer wear heels, he still She had started the year feeling for her patients, but this

adored her. identification had subsided into trying to survive the angry

Cecilia’s father had escaped from behind the Iron Cur- frustrations of the residents. She remembered one resident

tain—had “vaulted” (his term) the Berlin Wall in the who, when she could not remember the answer to a ques-

1960s. “Eez not a vall,” he insisted, “eez a goddamn fuckin’ tion, had hissed full of venom, “Do you even want to do

preeson.” He’d sought refuge in Italy, where he’d met Ce- patient care?” Another who’d called her a deer in head-

cilia’s mother. The two had worked their way to America, lights. Another who’d clapped her hands at Cecilia and

where her father promptly fell in love with all things Amer- called to her as to a puppy dog. She’d been ignored, de-

ican, especially the little known (and rarely eaten) Uncle meaned, her hands slapped by an imperious surgeon. It

Sam cereal. He’d stocked their kitchen with hundreds of made Cecilia wonder, “How can I treat patients with dig-

boxes of the stuff: patriotic insurance against “it” happen- nity and respect when I’m not treated that way myself?”

ing again. At bedtime, Cecilia’s father taught her to end That evening, Cecilia took a walk in Central Park. The

her prayers with “and please don’t let the communists take evening was sunny, the kind that makes a person yearn to

over America. Haymen.” linger outside until the last ray of light has faded from the

Aside from his accent, his love of music was the only west, and Cecilia completely forgot about Mona. She re-

other vestige remaining from the Old Country, “Your joiced in the gentle spring breeze, the soft splash of water

grandfather played veeolin. I played veeolin. Now you, in the Bethesda Fountain. She sat on a cement bench

dear sweet Sheesheelia, vill also play veeolin,” he’d said, warmed by the early evening sun and gazed up at the angel

absentmindedly tapping his lame left arm. The triceps had crowning the top of the fountain. The angel stood with

been shot off in his youth, leaving him unable to play his mighty wings outstretched, as if alighting from flight. She

beloved violin. Cecilia rarely asked about these matters. extended her right hand gracefully downward, offering sol-

Occasionally glimpses of the past emerged when her father ace to those below. Two sisters, their faces framed by halos

fell into a rare fit of sadness, but mostly the past stayed of long curls, played in the fountain. They splashed and

just there, bubbling under the surface. Cecilia would have squealed with delight, their laughter bouncing off the stone

liked to have known more about her heritage, but her fa- pavement. Cecilia absorbed their joy felt relief to be in the

ther’s melancholy moods scared her. presence of children blooming with health.

So Cecilia had learned the violin, and her playing res- Back at her apartment that evening, Cecilia’s eyes fell

onated with exuberance and love of life. Her teachers on her dusty violin case lying unused in a corner. She

boasted that she had an uncanny ear, an other-worldly tone picked up the case—unlatched it. She let her fingers slide

and a soulful vibrato. She performed through high school over the smooth, shining beauty of the violin’s varnish. She

and college, but upon reaching medical school, she laid caressed its curves longingly, her fingers curling around it.

down her violin for a “break” that had grown into three She lifted the instrument and let it come to rest against

long years of arduous study. She longed to play the violin her left shoulder, then hesitantly picked up the bow and

again, but she feared that her passion for music would con- played a few shaky notes. An electricity spread through

trol her life. her body, coming to rest in her fingertips. She shuffled

Yet it was this very adoration of sound that drew Cecilia through the old scores in her violin case and drew out Bee-

Academic Psychiatry, 30:1, January-February 2006 http://ap.psychiatryonline.org 81

ACOUSTICS

thoven’s Ninth Symphony, long her favorite. She loved the so gradually, Cecilia made a song out of their mutual notes.

galloping exuberance of the orchestra and chorus singing Without thinking, Cecilia fell into the Ode to Joy and

as one in the final movement. That night, Cecilia played Mona fell along with her. And then, a miracle. Mona

until her fingers were too tender to continue. The calluses stopped rocking and instead swung both hands back and

she’d had all her life, hardened through hours of express- forth in time to the music, a smile of pure ecstasy lighting

ing herself in music, had disappeared from lack of use, up her face. They sang the melody over and over, until

leaving her vulnerable. Cecilia realized that she was nearly late for class. “I’d like

The next day, Cecilia felt less reluctant to visit Mona. to sing with you longer, Mona, but I have to go to a lecture

The little girl still sat rocking to and fro, still humming the now.” No response from Mona, who remained singing,

same scales. “Good morning, Mona,” Cecilia said. “Do arms moving to the rhythm.

you remember me?” No response, only rocking and hum- As Cecilia turned to go, she heard, intermingled with

ming. “I remember you. You’re the girl with the golden Beethoven, “Ceceeeelia, you’re breakin’ my heart. Oh Ce-

voice,” Cecilia continued. No reaction. And then Cecilia ceeelia!” Cecilia, electrified, turned to look at Mona. The

had an idea: if Mona won’t answer me, I will answer her. words had sounded eerily normal, like those of any ordi-

Softly, Cecilia began to hum along with Mona. Still the girl nary 10-year-old. But the little girl still sat staring into

took no notice. Once in a while, Cecilia threw in a note of space, still flapping her hands to the music. Cecilia stood

her own, and after a few dissonant clashes, Mona started transfixed. She waited for more of Mona’s words until, with

mimicking Cecilia. It began hesitantly and with many mis- sinking heart, she realized that the little girl had begun to

takes, but gradually they started to sing together. And ever rock to and fro.

82 http://ap.psychiatryonline.org Academic Psychiatry, 30:1, January-February 2006

Вам также может понравиться

- I Love My Family by Elizabeth AbrahamДокумент65 страницI Love My Family by Elizabeth Abrahamelizabeth abrahamОценок пока нет

- MotherДокумент5 страницMotherLars Delos SantosОценок пока нет

- Crimson Boarding SchoolДокумент63 страницыCrimson Boarding SchoolLacie CrockerОценок пока нет

- Gillian Mears - The Mint Lawn (Extract)Документ33 страницыGillian Mears - The Mint Lawn (Extract)Allen & UnwinОценок пока нет

- Special ProjectДокумент11 страницSpecial ProjectNikko Capistrano Del RosarioОценок пока нет

- By Francisco Arcellana: The MatsДокумент2 страницыBy Francisco Arcellana: The MatsFei Genuino Cruz100% (1)

- DissociationДокумент4 страницыDissociationGeorge ChanОценок пока нет

- The Night Visitor ExtractДокумент8 страницThe Night Visitor ExtractQuercus BooksОценок пока нет

- The MatДокумент16 страницThe MatAdelisa NiñalОценок пока нет

- The MatsДокумент5 страницThe MatsElysee CalasagОценок пока нет

- Banjo Epiphany - Azimuth PDFДокумент4 страницыBanjo Epiphany - Azimuth PDFFish Barrel ReviewОценок пока нет

- A Curse, A Key, & A Corkscrew: Rhymes with Witch, #1От EverandA Curse, A Key, & A Corkscrew: Rhymes with Witch, #1Рейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Tillie Olsen - I Stand Here IroningДокумент6 страницTillie Olsen - I Stand Here IroningMaikel AshmallaОценок пока нет

- The Religious Affiliation of Charlie ChaplinДокумент15 страницThe Religious Affiliation of Charlie Chaplinmarcelagyn100% (1)

- The MatsДокумент8 страницThe MatsYannesa S. Bantilan - Balbin50% (2)

- Play Sa Phil Lit.Документ9 страницPlay Sa Phil Lit.Paula FontelaraОценок пока нет

- ST6Документ7 страницST6Daniel ColladoОценок пока нет

- The Mats (1 9 3 8)Документ7 страницThe Mats (1 9 3 8)raniele30Оценок пока нет

- Dirtbag, Massachusetts ExcerptДокумент5 страницDirtbag, Massachusetts ExcerptOnPointRadioОценок пока нет

- On Wings of Song by DischДокумент195 страницOn Wings of Song by DischAkiva SaundersОценок пока нет

- Hixnws 2021 March NewsletterДокумент59 страницHixnws 2021 March NewsletterRoger WhitakerОценок пока нет

- Tagalog Medley 1Документ4 страницыTagalog Medley 1Bon.AlastoyОценок пока нет

- Unit23 SolutionsДокумент7 страницUnit23 SolutionsAbcОценок пока нет

- English Case: Davis Contractors LTD V Fareham UDCДокумент7 страницEnglish Case: Davis Contractors LTD V Fareham UDCAin AnuwarОценок пока нет

- Troubleshooting DHCP and NAT Configurations PDFДокумент2 страницыTroubleshooting DHCP and NAT Configurations PDF94akuОценок пока нет

- The Amber Photograph: Newly Repackaged EditionОт EverandThe Amber Photograph: Newly Repackaged EditionРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (12)

- Benatar David - The Optimism DelusionДокумент5 страницBenatar David - The Optimism DelusionDuarte Harris CruzОценок пока нет

- Corporation Law Cases Set 1Документ32 страницыCorporation Law Cases Set 1Rodney AtibulaОценок пока нет

- Is Understanding Factive - Catherine Z. Elgin PDFДокумент16 страницIs Understanding Factive - Catherine Z. Elgin PDFonlineyykОценок пока нет

- Generation We - Eric Greenberg With Karl WeberДокумент257 страницGeneration We - Eric Greenberg With Karl WeberScarlettNyxОценок пока нет

- The Basics of Systems Geology: British Geological Survey, 2012. HTTP://WWW - Bgs.ac - Uk/systemsgeology/basics PDFДокумент0 страницThe Basics of Systems Geology: British Geological Survey, 2012. HTTP://WWW - Bgs.ac - Uk/systemsgeology/basics PDFivica_918613161Оценок пока нет

- 7th MEXICAN CULTUREДокумент3 страницы7th MEXICAN CULTUREJosé Carlos Villatoro AlvaradoОценок пока нет

- Billionaire’s Nanny: A Single Dad Second Chance Romance: Hot Billionaires, #4От EverandBillionaire’s Nanny: A Single Dad Second Chance Romance: Hot Billionaires, #4Оценок пока нет

- Creative Works - Main Report - ABCDДокумент65 страницCreative Works - Main Report - ABCDvenkatesh subbaiyaОценок пока нет

- The Urantia Book (Public Domain)Документ1 806 страницThe Urantia Book (Public Domain)Lenny100% (13)

- Front EndДокумент23 страницыFront EndMadridista RaeeОценок пока нет

- Moy Ya Lim Yao vs. Commissioner of ImmigrationG.R. No. L-21289 SCRA 292 DigestДокумент2 страницыMoy Ya Lim Yao vs. Commissioner of ImmigrationG.R. No. L-21289 SCRA 292 DigestKhen Tamdang100% (1)

- Aperin TOS Entrepreneurship Grade12Документ2 страницыAperin TOS Entrepreneurship Grade12Arvin Austria AperinОценок пока нет

- Harry Potter Past TenseДокумент1 страницаHarry Potter Past TenseAdonis1985Оценок пока нет

- Sat VocabДокумент35 страницSat VocabMinh DoОценок пока нет

- Esl CVДокумент1 страницаEsl CVSimon RattrayОценок пока нет

- Lesson 1 1 ICT Competency StdsДокумент24 страницыLesson 1 1 ICT Competency StdsKayla Marie CagoОценок пока нет

- Electrical Electronic Devices ShabbatДокумент79 страницElectrical Electronic Devices Shabbatמאירה הדרОценок пока нет

- In Mutation TestingДокумент6 страницIn Mutation TestingGaurav SharmaОценок пока нет

- 4B-Velocity Profiles (2021)Документ18 страниц4B-Velocity Profiles (2021)ArinaAdilaОценок пока нет

- Reported Speech CPS First Week of November PDFДокумент2 страницыReported Speech CPS First Week of November PDFMile GomezОценок пока нет

- Holding Together Federalism Coming Together Federalism: SSPM'SДокумент6 страницHolding Together Federalism Coming Together Federalism: SSPM'SVivek NairОценок пока нет

- MATH 2170: Differential Equations IДокумент3 страницыMATH 2170: Differential Equations IDhruv DharamshiОценок пока нет

- AlqamahДокумент20 страницAlqamahNadia AlfirdausiОценок пока нет

- Pancha Pakshi SastraДокумент2 страницыPancha Pakshi SastraRamesh Menon100% (1)

- Transac SQLДокумент1 663 страницыTransac SQLodlarhgОценок пока нет

- 323 1251 090Документ40 страниц323 1251 090primaryrateОценок пока нет

- Katapayadi SystemДокумент5 страницKatapayadi Systemnieotyagi100% (2)

- Summary: Trading in the Zone: Trading in the Zone: Master the Market with Confidence, Discipline, and a Winning Attitude by Mark Douglas: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandSummary: Trading in the Zone: Trading in the Zone: Master the Market with Confidence, Discipline, and a Winning Attitude by Mark Douglas: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (15)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (30)

- How to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipОт EverandHow to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (1135)

- Follow your interests: This will make you feel better about yourself and what you can do.: inspiration and wisdom for achieving a fulfilling life.От EverandFollow your interests: This will make you feel better about yourself and what you can do.: inspiration and wisdom for achieving a fulfilling life.Оценок пока нет

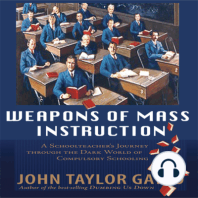

- Weapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory SchoolingОт EverandWeapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory SchoolingРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (149)