Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Fefu and Her Friends by Maria Irene Fornes

Загружено:

Madalina Gorgan0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

73 просмотров5 страницОригинальное название

Fefu and her friends by Maria Irene Fornes.docx

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

73 просмотров5 страницFefu and Her Friends by Maria Irene Fornes

Загружено:

Madalina GorganАвторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате DOCX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 5

Fefu and her friends

- The men possess the outside world;

- Fefu’s husband Phillip, her brother John, the gardener Tom walk the grounds ‘in the fresh

air and the sun”, while the women gather in the house, ‘in the dark’

- Three characters that cross over into the men’s world (outside): Fefu, Emma and Julia.

- Fornes genders the interior, with its depth, penetrability, and comfort – its domestic spaces

figured as body parts and inners organs – female.

- House/ grounds;

- The stone is a metaphor for the crucial, characterological difference between men and

women.

- The house is the locus of human warmth and social affirmation, but also the site of human

and animal functions that should remain unseen, such as the broken upstairs toilet, or the

black cat’s explosion of diarrhea in the kitchen.

- Julia, paralyzed, she suffers from hallucinations, more real than life, or being beaten,

tortured, and condemned to humiliating recitations about the ‘stinking’ and ‘revolting’

parts of the female body.

- Fefu enjoys ‘being like a man’, fixes toilets, and shoots a gun, but is hypnotically pulled

toward Julia’s female abyss.

- “Women are inferior beings. Their inferiority is constitutionaland resides in their sex…

which is a wound that never heals.” Octavio Paz

- In part I, which takes places in the living room, the public portion of Fefu’s house, the

references to female bodies emerge for the most part in veiled allusion and literary device.

- The married woman “a bonded slave, who takes her master’s name, her master’s bread, her

master’s commands, and serves her master’s passion.” Voltairine de Cleyre .

- The culminating event of Part I is the description of Julia’s accident

- Cindy and Christina- the conventional women;

- Julia is ‘petit mal’, she can not walk, she was not struck by the hunter’s shot that left her

with a bleeding forehead -> the fearless host Fefu will fear herself “host” to Julia’s

mysterious female contamination.

- The iconography of the “deer” as a purifier of venom, poison, and sin – of the ‘loathsome’

in short – would seem to operate in Fornes’s play as well. -> the antidotal creature. – the

deer as an emblem of rebirth.

- With the announcement of the spectators that they will be devided into four groups,

circulating through four locations in Fefu’s house to witness the scenes of Part II, the

alternate, compentatins pattern of the play begins to emerge.

- The dramatic model in Fefu will not be linear and progessive, but circulatory and cyclical.

- The house has a depth and scale matched to our offstage bodies. Its rooms are tied to the

needs of the body – the kitchen, the stomach; the bedroom, sleep and sex;

- Part II: spectators are invited at the beginning to cross the mainstage living room set and

walk through an upstage door. = > the spectators were no longer separated by the actors;

even more interesting is that fact that this repositioning makes aware of spectators’s own

bodies, in the theatre was the acquiring of new seating companions for each segment.

- Part II reveals the often literally organic concern with bodies and embodiment that is part

of Fefu’s design. – all follow the trajectory from dis- to re- memberment. Part II makes the

stage of dismemberment in this process, a centrifugal motion that fragments the audience,

cast, and setting, while stories of the individual characters’ shatterings are being revealed.

It is in this part of the play that Fornes breaks her group of eight women into twos and ones.

In the scenes that follow, the talk turns again and again to the dismembered female body.

- The eight women of the play fall into three groups, the more conventional heterosexuals,

the lesbians, and the three androgynous women, whom Fornes develops as figures with

mythic imaginations.

- Conventional women: Christina, Cindy and Sue; Sue, the treasurer of the group effort

rehearsed in Part III, stitches the world together with soup and tea, good cheer and

practicality. Of these three, she alone is apparently not uncomfortable in her body, and

makes no reference to its needs, longings, or vulnerability.

The women in the study

- Christina, a confessed ‘conventional’ is timid and imaginative.

- She concerns about Fefu’s outrageous shooting ‘game’ with Phillip, and about Fefu’s

keeping lethal weapons in the house. Fefu, she observes, may not be ‘careful with life’.

- Christina an Cindy now share a scene in the study; whish is the safest in the sense of the

least gender- or sex-encoded-of the four intimate spaces that provide the settings.

- Cindy reports a disturbing dream populated by male authority figures. At first

paternalistically Friendly, and then apparently indifferent, these figures become menacing

in a way that mixes seduction and physical threat. A policeman, Cindy relates, “grabbed

me and felt my throat from behind with his thumbs while he rubbed my nipples with his

pinkies. Then, he pushed me out the door. Then, the young doctor started cursing me”.

Cindy is unable to say what she wants to say, unable to react. The dream ends in unresolved

panic.

- Stacy Wolf suggests that the dominant force in the play is male violence – either fear of it,

enactment of it in the background story, or performance of it by Fefu and Cecilia in their

masculine aspects.

- Julia suffers hallucinations as real as life and actual physical symptoms, Fefu is visited by

daytime terrors of death and alarming portents of infirmity, but Cindy’s more complacent

imagination only dreams of malevolent doctor treating her for an indistinct health problem.

The women in kitchen

- The two lesbians seem not to share the fear and dependency that is particular to

heterosexuals in the play, but they also differ from each other.

- The frosty Cecilia and Paula who has shrunken emotional life and speaks in intellectual

abstractions;

- Paula identifies herself as a woman with a career.

- Cecilia makes aggressive, even cruel, sexual advances to the still wounded- Paula

- Paula is the strongest, and most fully alive woman in the play; she is the only character

from a working-class background, and the only one capable of class analysis, glimpsing

her upper-class friends in political and economic dimenstions of which they themselves are

unaware; she expresses no fear of male;

- Paula echoes the structure of the play that sets up a correspondence between body and

domicile.

- Sue – the most emotionally complete of the women, competent and caring, who is also

briefly in this scene – is staged in Fefu’s kitchen, the sustaining core, or stomach, as it

were, of Fefu’s house.

The women on the lawn

- Involves Fefu, Emma and Julia; Fefu and Emma play croquet on the lawn – this is the only

represented scene that abandons the house for the sunlight and air Fefu associates with

men.

- They are doing somehow mannish things for 1930’s women: they are talking openly about

sex while swinging at croquet balls. (discussion about genitals)

- Emma describes the beginning of a kind of breakdown, evidencing itself – she speaks in

quasi-erotic terms;

- Fefu then tells the story of the mangled and diseased black cat;

- The relationship with the cat sounds suspiciously like Fefu’s relationship with Phillip, but

with the roles reversed. Fefu becomes the black cat, in effect her own familiar, haunting

herself and Phillip from hell.

- Emma is left alone on the lawn, reciting Shakespeare’s fourteenth sonnet -> it is the second

of three important moments in the play in which Fornes draws attention to the revelatory

force of the human gaze.

- The aspiration, which is really the aspiration to the highest form of human love, is stated

in two ways, in the ideal of equal, conscious sexual union, and in the ideal of the silent,

profound, speech of the eyes. Emma, in her riff on the ‘devine registry of sexual

performance’, and in her own performance of Shakespeare, is thus far the bearer of both

messages.

- The scene hints at a culture of feminine freedom, of women able to leave the house-world

that demands, entrapment as the price of protection.

- Emma, who is too charmingly blind; Paula, who hurts too much.

The women in the Bedroom

- Julia’s world if the hell to Emma’s heaven.

- Julia is as deep portrait of the feminine subterranean ‘where the cockroaches aare’ as exists

in modern dramatic literature.

- The spectators are not given seats, but stand surrounding the ‘patient’ who lies on her

mattress on the floor, wearing a medical gown.

- The experience of Julia’s hallucination melts and slips across boundaries, those between

spectator and actor, between character and invisible persecutors, and even between

character and spectator. Can we be certain that it is not we, the surrounding audience, to

whom Julia is describing her journey througu hell?

- The bedroom scene is the only one that is not in the form of a dialogue between women.

- Putting Julia’s hallucination in the form of soliloquy without an authorized observer or

receiver is Fornes’s chief means of creating its surreal effect.

- This scene is also the only one to depart from realism in its setting;

- The dead leaveson the floor (in the bedroom) symbolizes contrast between the bright lawn

of the Emma-Fefu scene. The incursion of the woods into the space of the house ironically

recalls Julia’s last moment of idependence, when, in or near the forest, she was felled by

the hunter’s shot that killed the deer. Fefu and Emma are capable, whitin limits, of

appropriating the masculine preserves of fresh air and sunshine. Julia, once the most

independent of women, who moved as if unimpeded in the male world, is now captive in

the house-world of women, her former freedom reduced to a handful of dead leaves. These

leaves expressionistically portend her losing battle with death.

- The overlay of Fornes’s personal experience in the women’s movement on something akin

to a comic-strip playwriting experiment evolved unto the complexity of Julia, whose

mutilation is both socially imposed and regulated, but also strangely self-generated. Julia

both exemplifies and grasps this ambivalent condition of woman better than any other

character in the play that Fornes once identified her as ‘the mind of the play-the seer, the

visionary’.

- Though all four scenes develop the motif of female dismemberment, Julia’s goes far

beyond the others to an imaginative limit that approaches the literature of apocalypse.

- The narrative is not entirely clear. In her hallucinations Julia is speaking, and mostly

responding, to one or more male interrogators who have trained her in the recitation of a

prayer. She is explaining to them, once more in the language of dismemberment, what

another set of inquisitors did to her body. These were the implacable judges, who claimed

to love her, but threatened to cut her throat if she resisted.

- Part I is about gathering, part II abou dismemberment, part III about reintegration;

- The spectators are beginning to experience in their bodies the motions of dis- and re-

memberment that move the play and its characters.

- PIII – the musical movement is almost more appropriate a term – contains two group scenes

with all characters present that formalize in circular tableaux the circular shape of the play.

- These scenes represent yet one more vision of Fefu’s parable of the stone;

- The several scene fragments that comprise the joyous rondo of the water fight, as well as

the confrontation between Fefu and Julia that precedes the play’s mysterious, surreal end.

- Two sides of Fefu: playfully, even swaggeringly, performed the man, shooting Phillip,

fixing the toilet, and making macho pronouncements about women to scare the ‘girls’, or

she can collapse into fear and anxiety.

- Like the gun in the first act that goes off in the last, every vagrant reference in Fornes’s

seemingly nondirectional text assumes a precise place in a dense poetic structure.

- As Orpheus, Fefu seeks to break the law of the underworld and the grip of death.

- The ending of the play is a riddle.

- The game with the gun: Fefu takes the gun outside to clean it, fires and shots Julia in the

forehead. The play ends in a circular tableau.

- The rabbit dead, Julia ‘dead’;

- A rabbit; the rabbit has a homely association with reproduction. It may be a mark of Julia’s

decline and weakness that while she earlier fell as a deer, she has now succumbed as a

rabbit. The mystery of the rabbit is intensified by the formality and seeming solemnity of

the context in which it appears.

- ‘mourning women’

- We do not finnaly know what happens at the end of this play, not even whether Julia has

actually died, though many critics declare this as a certainty.

Вам также может понравиться

- Loa To The Divine NarcissusДокумент17 страницLoa To The Divine NarcissusVictoria ElswickОценок пока нет

- With Glowing Hearts: How Ordinary Women Worked Together to Change the World (And Did)От EverandWith Glowing Hearts: How Ordinary Women Worked Together to Change the World (And Did)Оценок пока нет

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Maria Irene Fornés and Multispatial TheaterОт EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Maria Irene Fornés and Multispatial TheaterОценок пока нет

- JADT Vol19 n1 Winter2007 Lee Having Favorini BarriosДокумент100 страницJADT Vol19 n1 Winter2007 Lee Having Favorini BarriossegalcenterОценок пока нет

- Three Plays by Granville-Barker: The Marrying of Ann Leete; The Voysey Inheritance; WasteОт EverandThree Plays by Granville-Barker: The Marrying of Ann Leete; The Voysey Inheritance; WasteОценок пока нет

- Shakespearean Insult GeneratorДокумент1 страницаShakespearean Insult GeneratorJennyОценок пока нет

- Antigone Background Pack-2Документ18 страницAntigone Background Pack-2Bethany KellyОценок пока нет

- The Greek Trilogy by Luis AlfaroДокумент5 страницThe Greek Trilogy by Luis AlfaroKidany R Camilo Nieves0% (2)

- The Purpose and Effects of Metatheatre in ShakespeareДокумент4 страницыThe Purpose and Effects of Metatheatre in ShakespeareMichael HaaseОценок пока нет

- Dear Brutus J M Barrie PDFДокумент71 страницаDear Brutus J M Barrie PDFkPodОценок пока нет

- Mystery and Morality Plays - The Delphi Edition (Illustrated)От EverandMystery and Morality Plays - The Delphi Edition (Illustrated)Оценок пока нет

- Real Thing ProgramДокумент6 страницReal Thing ProgramRay RenatiОценок пока нет

- It at Least-I: As SHEДокумент4 страницыIt at Least-I: As SHEjoseph YattaОценок пока нет

- Antigone PDFДокумент68 страницAntigone PDFabhijeet nafri100% (1)

- Edward Albee - Life and CareerДокумент9 страницEdward Albee - Life and CareerCalin SoptereanОценок пока нет

- ARISTOTLE - Poetics (English)Документ3 страницыARISTOTLE - Poetics (English)Miruna Anamaria Lupăștean50% (2)

- Plays: The Dream Play - The Link - The Dance of Death Part I and IIОт EverandPlays: The Dream Play - The Link - The Dance of Death Part I and IIОценок пока нет

- The Lesson by Eugene IonescoДокумент34 страницыThe Lesson by Eugene IonescoSadia ShahОценок пока нет

- LineStorm Playwrights Present Go Play Outside: Twenty-Five Short Plays Written for the Great OutdoorsОт EverandLineStorm Playwrights Present Go Play Outside: Twenty-Five Short Plays Written for the Great OutdoorsLolly WardОценок пока нет

- Deadly TheatreДокумент2 страницыDeadly TheatreGautam Sarkar100% (1)

- Tennessee Williams Minorities and MarginalityДокумент299 страницTennessee Williams Minorities and MarginalityMaria Silvia Betti100% (1)

- Fefu and Her Friends by Maria Irene FornesДокумент5 страницFefu and Her Friends by Maria Irene FornesMadalina GorganОценок пока нет

- Action by Sam ShepardДокумент3 страницыAction by Sam ShepardMadalina Gorgan33% (3)

- Test Clasa A 5aДокумент2 страницыTest Clasa A 5aMadalina GorganОценок пока нет

- Test Clasa A 5aДокумент2 страницыTest Clasa A 5aMadalina GorganОценок пока нет

- Checkpoint - Revision Units 9 - 10: 1. Look and Read. Write Yes or NoДокумент3 страницыCheckpoint - Revision Units 9 - 10: 1. Look and Read. Write Yes or NoMadalina GorganОценок пока нет

- Objective KETДокумент58 страницObjective KETMadalina GorganОценок пока нет

- SAILOR 900 VSAT High Power Product SheetДокумент2 страницыSAILOR 900 VSAT High Power Product Sheetkarim hadidОценок пока нет

- Absract For Reverse Parking Sensor CircuitДокумент4 страницыAbsract For Reverse Parking Sensor CircuitKïshörë100% (1)

- Hotel California (8 3 20) - Acoustic Guitar (Rhythm)Документ1 страницаHotel California (8 3 20) - Acoustic Guitar (Rhythm)Ross JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Contoh Spesifikasi Material CCTVДокумент6 страницContoh Spesifikasi Material CCTVardi yogaОценок пока нет

- All WavesДокумент155 страницAll WavesTenisha CastilloОценок пока нет

- Sining Tanghalan GuidelinesДокумент22 страницыSining Tanghalan GuidelinesKairuz Demson Aquilam100% (1)

- Paradox Esprit E55 E65 User ManualДокумент28 страницParadox Esprit E55 E65 User ManualAndrei PantaОценок пока нет

- Physics (Specification A) Phap Practical (Units 5-9)Документ12 страницPhysics (Specification A) Phap Practical (Units 5-9)Avinash BoodhooОценок пока нет

- Keh P5015,4015,4010Документ48 страницKeh P5015,4015,4010Nachiket KshirsagarОценок пока нет

- Angelica Bonus - Resume 2011Документ1 страницаAngelica Bonus - Resume 2011imabonusОценок пока нет

- Alcatel Performance Data MeasurementДокумент128 страницAlcatel Performance Data MeasurementVijay VermaОценок пока нет

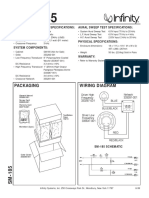

- Infinity sm-185Документ2 страницыInfinity sm-185Bmwmotorsport GabriОценок пока нет

- The DirtДокумент2 страницыThe DirtPoppy FeildОценок пока нет

- LG 32lg3000 Chassis Ld84a LCD TV SMДокумент26 страницLG 32lg3000 Chassis Ld84a LCD TV SMEmma FrostОценок пока нет

- VCE Music Prescribed List Group Works Units 3-4 2018Документ59 страницVCE Music Prescribed List Group Works Units 3-4 2018Jerry LauОценок пока нет

- Intro To Event Management - Final PresoДокумент28 страницIntro To Event Management - Final PresoyogeshwarnОценок пока нет

- MuusikaДокумент4 страницыMuusikaNicolaas JanssenОценок пока нет

- TVS Jupiter Standard Price QuoteДокумент2 страницыTVS Jupiter Standard Price Quotehiren_mistry55Оценок пока нет

- Decoding Alright by Kendrick LamarДокумент4 страницыDecoding Alright by Kendrick Lamargovind shankarОценок пока нет

- The "Heavenly Length" of Schubert's Music by Scott Burnham - Ideas, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1999Документ5 страницThe "Heavenly Length" of Schubert's Music by Scott Burnham - Ideas, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1999Aaron GrantОценок пока нет

- A Love To Last A Lifetime - Juris Fernandez Version (Jose Marie Chan)Документ6 страницA Love To Last A Lifetime - Juris Fernandez Version (Jose Marie Chan)Wadap DawgОценок пока нет

- Electromagnetic Field Detector AlarmДокумент2 страницыElectromagnetic Field Detector AlarmrodeoaОценок пока нет

- The First Noel SATB Coro ScoreДокумент10 страницThe First Noel SATB Coro ScoreJosé Andrés100% (1)

- Coax Catalog - Times Microwave SystemДокумент80 страницCoax Catalog - Times Microwave SystemweirdjОценок пока нет

- Xii English Poem6 The Solitary Reaper QaДокумент3 страницыXii English Poem6 The Solitary Reaper QaNiketa LakhwaniОценок пока нет

- AVIC-F940BT: Installation Manual Руководство по установкеДокумент0 страницAVIC-F940BT: Installation Manual Руководство по установкеSandu ButnaruОценок пока нет

- DLL - Mapeh 6 - Q3 - W9Документ6 страницDLL - Mapeh 6 - Q3 - W9CristinaTalloGondongОценок пока нет

- Asian American Plays For A New Generation: Josephine Lee, Donald Eitel, Rick ShiomiДокумент4 страницыAsian American Plays For A New Generation: Josephine Lee, Donald Eitel, Rick ShiomiKaitlin MirandaОценок пока нет

- Notes On Hype DEVON POWERSДокумент7 страницNotes On Hype DEVON POWERSSantiago GómezОценок пока нет

- Sound - Class 8 - Notes - PANTOMATHДокумент7 страницSound - Class 8 - Notes - PANTOMATHsourav9823Оценок пока нет