Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Enemy at The Gates

Загружено:

Deimantė AniūkštytėОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Enemy at The Gates

Загружено:

Deimantė AniūkštytėАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Foreign Policy Analysis (2017) 0, 1–19

Enemy at the Gates: A Neoclassical Realist

Explanation of Russia’s Baltic Policy

ELIAS GÖTZ

Uppsala Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Uppsala University

What drives Russia’s Baltic policy? To answer this question, I develop a neo-

classical realist framework that explains how local great powers act toward

neighboring small states. In brief, the framework argues that local great

powers face strong systemic incentives to establish a sphere of influence

around their borders. Toward that end, they can employ positive and neg-

ative incentives. The general rule is that the higher the level of external

pressure, the more assertive the policies pursued by the local great power.

However, this simple relationship between external pressure and regional

assertiveness is moderated by two variables: (1) the ability of small states to

obtain security guarantees from extra regional powers; and (2) the level of

state capacity of the local great power. The article develops this theoretical

argument and shows that it goes a long way to explain the overall pattern

and evolution of Russia’s Baltic policy over the last two decades.

In the wake of the Ukraine crisis, the question of security in the Baltics has received

increased attention from policymakers, think-tankers, and academics. In particular,

a lively debate has ensued among Western observers on whether Russia will launch a

Crimea-style operation or perhaps even a conventional military strike in the region

(see, e.g., Carpenter 2014; Chivvis 2015; Lucas 2015). This paper puts the issue

into a larger theoretical and temporal perspective and examines the evolution of

Moscow’s policies toward the Baltic states from 1995—after the last Soviet/Russian

troops had been withdrawn from the area—to the present.

During this two-decade-long period, Russia’s Baltic policy has been marked by

many zigs and zags. Nonetheless, two major phases can be distinguished. In the

first, from 1995 to 2003, Russia’s policy was characterized by rhetorical opposition

to the pro-Western orientation of the three Baltic states. Moscow launched a bar-

rage of threats of what would happen if they established close ties to the West in the

military and security fields. Beyond the realm of rhetoric, however, relatively little

happened—quite the opposite. Russia’s Baltic policy became increasingly incoher-

ent, self-contradictory, and less assertive. In the second phase, which runs from 2004

to the present, Russia has adopted a more coherent and tough-minded approach.

Moscow has exerted pressure on the Baltic states through cyberattacks, shows of

force, attempts at internal subversion, and economic sanctions. But, at the same

time, it has abstained from the direct use of force.

Author Bio: Elias Götz is a postdoctoral researcher at the Uppsala Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Uppsala

University. His main areas of expertise are security studies, international relations theory, and Russian foreign policy.

Author’s Note: I would like to thank Matthew Kott and Elena Korosteleva; the participants at the January 2017

UPTAKE training school at the University of Kent; and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and

suggestions.

Götz, Elias (2017) Enemy at the Gates: A Neoclassical Realist Explanation of Russia’s Baltic Policy. Foreign Policy Analysis,

doi: 10.1093/fpa/orx011

© The Author (2017). Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the International Studies Association.

All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

2 Enemy at the Gates

The evolution of Russia’s Baltic policy raises three questions. First, how can one

explain the discrepancy between words and deeds in the latter half of the 1990s?

Second, what accounts for the shift in Russia’s approach toward the Baltics in the

middle of the 2000s? And third, what are the underlying drivers and ambitions that

guide Russia’s policies in the region?

The existing literature provides some potential answers, highlighting factors

such as the Kremlin’s turn toward authoritarianism and the resurgence of eth-

nonationalist sentiments in Russia (for an overview, see Sleivyte 2010, 120–22).

Perhaps the most prominent explanation is provided by scholars working in the

status perspective. They suggest that Russia pursued a Western-oriented policy

throughout large stretches of the 1990s and early 2000s to gain recognition from the

United States as an equal partner. Accordingly, Moscow’s policy toward the Baltics

was marked by moderation and restraint. By the mid-2000s, however, it became in-

creasingly clear that Washington was unwilling to treat Moscow as a coequal in diplo-

matic and military affairs. In response, Moscow adopted a more anti-Western stance.

Concomitantly, Moscow began to pursue a tough-minded policy vis-à-vis neighbor-

ing countries, including the Baltic states, to reassert Russia’s great-power status (see,

e.g., Larson and Shevchenko 2014; Tsygankov 2013).

In this article, I present an alternative answer to the questions raised above. More

specifically, I develop a neoclassical realist framework that explains how local great

powers deal with neighboring small states. My framework shows that local great pow-

ers face strong systemic incentives to establish a sphere of influence around their

borders. Toward that end, they can apply a wide range of diplomatic, economic, and

military instruments. The basic argument is that if the level of external pressure in-

creases (that is, if smaller neighbors make attempts to join forces with extraregional

powers), the local great power will tighten the screws on its neighbors and adopt

more coercive policies—including the threat and use of force, if needed—to pre-

vent them from teaming up with outsiders.

However, this simple, quasi-linear relationship between external pressure and re-

gional assertiveness must be qualified in two ways. First, once a neighboring small

state has entered into a security partnership with a major extraregional power, the

local great power will avoid the direct use of force. After all, it may lead to a costly

military confrontation with a more powerful adversary. Instead, the local power will

seek to destabilize the foreign-aligned small state through various forms of political

and economic subversion. Second, the link between external pressure and regional

assertiveness presupposes that the local great power can be treated as a unitary and

strategic actor. This is not always the case, however. As neoclassical realists have

shown, countries that lack state capacity are unable to act upon systemic incentives

in a strategic fashion (Schweller 2004; Taliaferro 2006; Zakaria 1998). Accordingly,

shifts in the level of state capacity also affect the neighborhood policies of the lo-

cal great power. Overall, I find that this framework—which combines international,

regional, and domestic factors—goes a long way toward explaining the course of

Russia’s Baltic policy from the mid-1990s to the present.

The contribution of this article is threefold. First, it provides a theoretically

informed account of Russia’s Baltic policy. Second, it advances neoclassical re-

alist scholarship, which has been criticized for its focus on Western great pow-

ers and historical cases (Ripsman, Taliaferro, and Lobell 2016, 182–83). Third,

the article develops a theoretical framework of a phenomenon that has remained

undertheorized—namely how local great powers act toward smaller neighbors that

are aligned with a major extraregional power (for a partial exception, see Knudsen

1988). This topic is likely to gain in importance in the years ahead. After all, the

United States has established strong politico-military ties with a number of smaller

countries in Central Eurasia and East Asia over the last decades (Selden 2013). At

present, however, regional great powers such as Russia and China are re-emerging

in these parts of the world. The question thus becomes how these powers will

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

ELIAS GÖTZ 3

deal with neighboring small states that have entered into security partnerships with

Washington. The framework developed in this paper makes a step toward answering

this broader question.

In short, I provide a theory of foreign policy that explains state choices and

strategies—a Type II neoclassical realist theory (Ripsman, Taliaferro, and Lobell

2016, 29–31)—and apply it to the case of Russia’s Baltic policy. Moreover, my theo-

retical argument contributes to our understanding of regional security dynamics in

the Baltic area and, potentially at least, in other parts of the world.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. The first section lays out the

theoretical argument and derives some expectations about Russia’s Baltic policy.

The second and third sections examine to what extent these expectations hold up

against the track record of Russia’s Baltic policy from the mid-1990s to the present.

The concluding section compares my neoclassical account of Russia’s Baltic pol-

icy to the arguments of the status perspective, briefly outlined above, and suggests

directions for future scholarship.

Neoclassical Realism and the Pursuit of Regional Primacy

Neoclassical realism’s central argument is that a country’s foreign policy is shaped

by the interplay of international and domestic conditions (Rose 1998). Thus, any

neoclassical realist theory worth its salt must accomplish two tasks: explicate how sys-

temic factors incentivize and constrain the formation of foreign policy, and specify

the unit-level factors that moderate the link between systemic influences and actual

state behavior (Rathbun 2008).

International Conditions: Systemic Incentives and Constraints

How do systemic influences shape the neighborhood policies of major powers? Ac-

cording to offensive realism, the structure of the international system—marked by

anarchy and the ever-present uncertainty over others’ intentions—pushes major

powers to pursue regional hegemony (Mearsheimer 2001). Defensive realists, on

the other hand, hold that the international system only provides incentives for bal-

ancing behavior—not for power maximization. But, notwithstanding this point of

contention, many defensive realists agree that there are good reasons for major pow-

ers to surround themselves with a zone of influence. As Robert Jervis (1978, 169)

notes, “In order to protect themselves, states seek to control, or at least to neutral-

ize, areas on their borders.” In short, when it comes to the neighborhood policies

of major powers, there appears to be room for combining elements from offensive

and defensive realism.1

If one fuses insights from the two theoretical strands, three important reasons

can be identified as to why major powers want to carve out spheres of influence

near their home territories. First of all, major powers seek to prevent neighboring

states from entering into alliances or security partnerships with great-power rivals

from other parts of the world. Nobody, after all, wants to have client states of po-

tential adversaries on their doorstep (Mearsheimer 2001, 142–43). The underlying

reason is simple. The projection of power, especially military power, increases with

proximity (Walt 1987, 23–24). It is therefore important to prevent extraregional

powers from establishing forward-operating sites like airfields and army bases next

to one’s home territory. This, in turn, provides a strong incentive for major powers

to have some degree of control over the external relations and defense policies of

smaller neighboring states.

Second, and relatedly, major powers have an incentive to maintain access to

transport infrastructure and military installations on the territory of neighboring

1

Parts of this section build on Götz (2016, 302-6).

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

4 Enemy at the Gates

countries. After all, access to such installations—for example, early warning radar

sites and intelligence-gathering facilities—can be vital for protecting the land, air,

and sea approaches to one’s home territory. What is more, airfields and seaports

in neighboring states can serve as stepping stones for the local power to project

influence into regions further afield (Harkavy 2007).

Third, major powers want to maintain some form of control over lines of com-

munication and transport routes in their geographical vicinity. There are several

reasons for this. For one thing, it reduces the risk of being cut off from important

resources and export markets during times of international crisis. For another, it

enables the local power to constrict the freedom of maneuver of potential adver-

saries in one’s home region. Additionally, control over trade and transport arteries

can be used to exert pressure on smaller neighboring states, if deemed necessary.

In essence, the combination of international anarchy and uncertainty, coupled

with the effects of geographic proximity (a “structural modifier” in the terminology

of neoclassical realism), incentivizes powerful states to pursue regional primacy. To

achieve this aim, they can employ a range of diplomatic, economic, and military

instruments.

Elsewhere, I have shown that diplomatic, economic, and military instruments can

take the form of positive incentives (carrots) or negative incentives (sticks). In brief,

positive incentives refer to forms of statecraft such as diplomatic blandishments, the

provision of economic assistance, and weapons transfers. Negative incentives refer

to forms of statecraft such as the cut-off of diplomatic relations, the imposition of

economic sanctions, and the threat and use of force (for more on this, see Götz

2016, 304–6). The question that remains is: what determines the choice of policy

tools through which states pursue regional primacy?

My theory suggests that the choice of policy tools is largely driven by the intensity,

or level, of external pressure. For the purposes of this article, the level of external

pressure on the local great power is defined as a function of the relationship be-

tween great-power rivals (actual or potential) from other parts of the world and

small states in the immediate vicinity of the local power. Simply put, the closer

the politico-military ties between extraregional powers and small states in the lo-

cal power’s vicinity, the higher the level of external pressure (for similar arguments,

see Knudsen 1988, 15–19; MacFarlane 2003, 126–27).

Accordingly, the local power is exposed to a high level of external pressure if small

states in its vicinity make attempts to forge close security ties with extraregional pow-

ers and extraregional powers indicate a willingness to engage in substantial military

cooperation with them (e.g., through troop deployments or defense agreements).

In such situations, the local power will rely on negative incentives to constrict the

foreign-policy autonomy of smaller neighboring states. The aim is to coerce their

governments to cut off ties with outsiders. Conversely, the level of external pressure

is low if smaller neighboring states have aligned their military and defense policies

with the local power. In such situations, the local power will use positive incentives

to keep smaller neighbors in its orbit of influence.

This is, of course, a stylized picture. In reality, the level of external pressure is not

always high or low but often hovers somewhere between the two. It may be useful,

therefore, to think of external pressure as a continuum. As the level of external

pressure increases and smaller neighboring states deepen their security ties with

extraregional powers, the local power will gradually move from the application of

positive incentives to the use of negative incentives. In other words, there exists a

quasi-linear relationship between the severity of external pressure and the assertive-

ness of the local power vis-à-vis neighboring small states.

That said, one important qualification must be added. If a neighboring small

state manages to establish a close politico-military relationship with a major extrare-

gional power—which means that the level of external pressure is very high—the

local power will refrain from any direct application of military force against this

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

ELIAS GÖTZ 5

small state. The reason is simple. The local power fears that the employment of

highly assertive policies—an armed intervention, for example—might lead to a ma-

jor confrontation with the extraregional power that serves as the small state’s secu-

rity patron. Thus, the local power will accept a degree of restraint (Knudsen 1988,

17; also see Huth 1988).

This does not mean, however, that the local power will stand idly by and do noth-

ing. Instead, the local power will resort to means short of the application of force.

This may include economic pressure, intelligence operations, and interference in

the internal affairs of the foreign-aligned small state. In the best-case scenario, the

local power will be able to reverse the strategic direction of the foreign-aligned small

state through such activities. At minimum, such activities contribute to keeping the

neighboring small state off-balance and destabilize it from within. In short, in situa-

tions in which the level of external pressure is high but the use of force is considered

too risky and dangerous, the local power will seek to subvert foreign-aligned small

states through coercive measures that stop short of military force.

One example of these dynamics is the US approach toward Cuba during the Cold

War. In the late 1940s and 1950s, the United States used positive incentives such as

economic and military assistance to maintain a pro-American regime in Havana.

However, as a result of the 1959 revolution, the level of external pressure increased.

The new government in Cuba made clear that it wanted to establish close ties with

the Soviet Union. In response, Washington began using negative incentives and pur-

sued an increasingly assertive policy toward Cuba. Think, for instance, of the failed

Bay of Pigs invasion. US policy changed again after the Cuban missile crisis. A ma-

jor reason for this was that Moscow had indicated its readiness to protect the Castro

regime in a future conflict with the United States. Thus, in subsequent years and

decades, Washington refrained from the direct application of military force vis-à-vis

Havana. Instead, Washington resorted to softer forms of hard power—such as inter-

nal subversion and economic pressure—to destabilize Cuba and, if possible, effect

a regime change (for an overview of US-Cuba relations, see Perez 2003, 238–62).

This case nicely illustrates that a close security partnership between a small state

(Cuba) and a major extraregional power (Soviet Union) can induce some restraint

in the local great power (United States).

Of course, the local power will give up its self-effacement if there is a clear and

present danger that an extraregional power plans to use the small state’s territory

as launching pad for an attack on the local power’s homeland. In such situations,

the local power will resort to military means—even accepting the possibility that it

may lead to a major military conflict with the extraregional power. After all, if an

attack is imminent, there is nothing that holds back the local power from striking

against the foreign-aligned small state. For instance, if Washington had received

information that the Soviets planned to use Cuba as a bridgehead to launch an

attack on the United States, it seems not far-fetched to assume that Washington had

carried out a preemptive strike on the island.

In sum, the level of external pressure is a moderating variable that affects the se-

lection of tools and tactics employed by powerful states in the pursuit of regional

primacy. That said, it is worth reiterating that the incentive to pursue regional pri-

macy in the first place derives from the mix of international anarchy, uncertainty,

and geography. In other words, the structure of the international system pushes

states to make bids for regional primacy (goals), whereas the level of external pres-

sure affects the way in which states seek to achieve this aim (means).

Before proceeding, one should note that neoclassical realism is a broad

school of thought that identifies a number of international-level variables, in-

cluding the clarity of signals about threats and opportunities, the relative per-

missiveness/restrictiveness of states’ environments, and time horizons (Ripsman,

Taliaferro, and Lobell 2016, 46–56). In this study, I consciously limit myself to basic

features of the international system (anarchy, uncertainty, and geography), along

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

6 Enemy at the Gates

with the level of external pressure, in order to isolate their effect on the neigh-

borhood policies of major powers. Moreover, doing so enables me to theorize how

systemic incentives interact with variations in state capacity in the formation of for-

eign policy.

Domestic Conditions: The Importance of State Capacity

Thus far, my theory suggests that external factors determine the strategic behavior

of major powers vis-à-vis neighboring small states. This line of reasoning rests upon

the assumption that major powers can be treated as rational and unitary actors—

an assumption that guides many structural realist analyses of world politics. How-

ever, its usefulness has been called into question, not least by Innenpolitik theorists

who emphasize the role of domestic political actors and societal forces (see, e.g.,

Moravcsik 1997).

Building upon the work of neoclassical realist scholars, I strike a middle-ground

and argue that major powers act as if they were unitary actors—if they have a suffi-

cient level of state capacity. This line of reasoning is based on the observation that

well-functioning states (regardless of regime type) tend to act in a unitary fashion

when it comes to major economic and military matters that affect the country’s se-

curity (see, e.g., Dueck 2009; Krasner 1978). To be sure, the timing and style of

individual policies may be affected by intragovernmental disputes and bureaucratic

maneuvering. The broader pattern of behavior, however, is determined to a large

extent by external factors and strategic considerations (for a defense of the unitary-

actor assumption, see Grieco 1997, 168–69).

If, on the other hand, countries lack state capacity, they are best understood as

composite rather than unitary actors. That is to say, their behavior is shaped by the

self-serving agendas and interests of subnational actors. It follows that government

authorities in countries with weak state capacity are unable to respond effectively

to system-level impulses (Schweller 2004; Zakaria 1998). In short, state capacity is

a moderating variable that conditions the impact of system-level impulses on actual

foreign policy behavior.

This proposition raises an important conceptual issue: what exactly is meant by

state capacity here? State capacity, after all, has become a term with many mean-

ings (for overviews, see Cingolani 2013; Hendrix 2010). For the purposes of this

article, I conceptualize state capacity in a relatively narrow sense. I focus on the

so-called “foreign policy executive”—which comprises the leadership, foreign and

defense ministries, and other government officials responsible for formulating and

conducting foreign security policy—rather than on the state machinery as a whole

(Blanchard and Ripsman 2013, 7–8). Moreover, with regard to “capacity,” I do not

look at factors such as administrative and bureaucratic quality. Instead, I concen-

trate on two dimensions that appear most relevant to our discussion: extraction

capacity and autonomy.

Extraction capacity refers to the ability of government authorities to mobilize

resources and collect taxes from society. Its importance is hard to overstate: if gov-

ernment authorities cannot levy taxes, they lack the ability to convert the country’s

raw power resources into actual economic and military capabilities (Taliaferro 2006,

487–91; for background, see Thies, Chyzh, and Nieman 2016). Moreover, if govern-

ment authorities lack extractive capacity, they are unable to finance major foreign

policy programs such as the pursuit of regional primacy. After all, no matter if re-

gional primacy is pursued through positive incentives (e.g., provision of aid, arms

transfers) or negative incentives (e.g., imposition of sanctions, threat of force), it

is costly in economic terms. Hence, extraction capacity is a precondition for major

powers to exert influence over neighboring countries.

Autonomy, on the other hand, refers to the ability of state officials to formu-

late and implement decisions against the wishes of powerful societal actors such as

NGOs, financial-industrial groups, and ethnic communities (Ripsman 2002, 43–58;

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

ELIAS GÖTZ 7

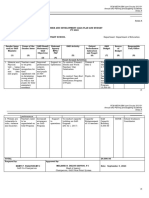

Figure 1: A Neoclassical Realist Theory of the Pursuit of Regional Primacy

for background, see Mann 1984). Naturally, these actors lobby the government to

advance their own goals and objectives; in itself, that is not a problem. It can be-

come a problem, however, if government authorities are so weak that they cannot

withstand the prodding and cajoling of societal actors. If this is the case, the state as

an institution is effectively captured by interest groups. As a result, government au-

thorities will pursue policies that suit the narrower objectives of societal actors with

little regard for the country as a whole (Ripsman 2009). This in turn makes it ex-

tremely difficult, if not impossible, for the foreign policy executive to develop and

implement a concerted approach vis-à-vis smaller neighbors. In essence, the pur-

suit of regional primacy presupposes that the local power possesses both extraction

capacity and some degree of state autonomy vis-à-vis societal actors.

As depicted in Figure 1, the gist of the argument is that major powers have a

system-induced incentive to pursue regional primacy (A). Toward that end, major

powers will engage in soft-line or hard-line policies, depending on the level of exter-

nal pressure (B). Lastly, the argument suggests that the pursuit of regional primacy

is moderated by the level of state capacity (C).

Neoclassical Realism and Russia’s Baltic Policy: Theoretical Expectations

What does the neoclassical realist theory just described imply for Russia’s Baltic pol-

icy? First of all, it becomes clear that the Baltic states, despite their small size, are

of strategic importance to Russia. A peek at the map shows why. Estonia and Latvia

have common land borders with Russia and are situated close to the political heart-

land of the Russian Federation. Estonia, for example, is less than 160 km from St.

Petersburg and no more than 850 km from Moscow. In addition, several important

trade arteries and transport corridors run through the Baltic region. Of particu-

lar importance here is Lithuania, which serves as a land bridge connecting Russia

(via Belarus) with the Kaliningrad exclave. Thus, the baseline expectation is that,

for geopolitical reasons alone, Russia wants to have some form of control over the

foreign-policy orientation of the Baltic states.

Second, my neoclassical realist theory suggests that the level of external pressure

shapes Russia’s strategic behavior toward the Baltic states. Accordingly, as the Baltics

moved toward membership in NATO in the late 1990s, one would expect that Russia

would have used all means available, including the threat and use of force, to de-

rail this process. Furthermore, one would expect that Russia would have abstained

from the direct use of force vis-à-vis the Baltics after they joined NATO, for fear of

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

8 Enemy at the Gates

provoking a major military conflict with the alliance. Finally, one would expect that

Moscow would consider launching strikes on the Baltic states, if there were a clear

danger that NATO would use their territory for military operations against Russia.

Third, my neoclassical realist theory suggests that the link between external pres-

sure and Russia’s Baltic policy is moderated by variations in state capacity. This

means that government authorities in Moscow will be unable to act upon system-

level incentives and constraints, if the Russian state lacks extraction capacity and

autonomy. Under such circumstances, the level of external pressure has little effect

on Moscow’s policies in the Baltic region. Instead, Russia’s actions are guided by the

narrower interests of societal actors.

The following two sections examine to what extent these expectations measure

up to Russia’s Baltic policy. Toward that end, I analyze the development of Moscow’s

behavior vis-à-vis the Baltics over the last two decades. To be clear, the purpose of my

analysis is not to provide an exhaustive explanation of the case. This would require

a thorough engagement with alternative explanations, the investigation of causal

mechanisms, and access to internal government documents that are not available

at present. My aim, therefore, is more modest: to illustrate the workings of my neo-

classical theory, test its plausibility against the existing empirical evidence, and in

the process of doing so, provide a theoretically informed interpretation of Russia’s

Baltic policy.

Phase I: Russia’s Baltic Policy, 1995–2003

In the mid-1990s, Western states and organizations began establishing closer ties

with the Baltic countries in the political, economic, and military spheres. Russian

government officials protested vehemently against these moves. On the ground,

however, relatively little happened. As the scholar Raimo Väyrynen (1999, 221)

noted, “Russia has continued to express its opposition to NATO membership for

the Baltic states, but otherwise it has been rather passive in relation to them.” There

is, in other words, a twin puzzle: why did Russia not respond more strongly to the

budding partnership between the Baltic countries and the West, and how can one

explain the discrepancy between Moscow’s assertive rhetoric and less assertive ac-

tions? As I show in this section, the interplay of growing external pressure and de-

clining state capacity can account for Moscow’s contradictory approach.

External Pressure

All three Baltic states had joined NATO’s Partnership for Peace (PfP) program in

1994. In the following years, they participated in a number of NATO-led training ex-

ercises, expressed their intent to become full members of the alliance, and engaged

in several so-called BALT-projects. These projects aimed at promoting inter-Baltic

cooperation but also at creating economic, technological, and military structures

in the Baltic states that were interoperable with those of the West (Grissom 2003,

20–23; Huang 2003, 37–41; Kramer 2002, 744–45). The United States, for example,

helped to set up a Baltic airspace surveillance system, known as BALTNET, which

was “designed to be fully compatible with NATO systems” (Huang 2003, 39). In

1998, moreover, Washington signed a Charter of Partnership with the Baltic states,

which included a commitment for closer cooperation in the security realm and a

promise to support Baltic membership in NATO (Black 1999, 260; Kramer 2002,

741). Although the Baltic states were not included in the first round of NATO en-

largement, they received Membership Action Plans in 1999. Three years later, in

November 2002, they were invited to join the alliance.

Moscow strongly opposed the increasingly close ties between the Baltic states and

NATO. Already in 1996, President Yeltsin warned Washington that “the Baltic states’

admission to NATO is absolutely unacceptable. Any steps in that direction would

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

ELIAS GÖTZ 9

directly challenge Russia’s national security interests and undermine European sta-

bility and security” (quoted in “Yeltsin Denounces Balts to Clinton 1996”). The op-

position to NATO expansion became official state policy in February 1997, when

Moscow issued a document entitled “Russian Policy Guidelines towards the Baltic

States.” The document listed an array of political and economic objectives, but

it also made clear that the highest priority was to prevent Baltic membership in

NATO (Herd 1999a, 200–1; Oldberg 2003, 10; Ziugzda 1999, 7–8). Moreover, both

the 1997 and 2000 National Security Concepts explicitly identified the “eastward

expansion” of NATO as a threat to Russian security (RF 1997, 2 and 8; RF 2000a, 5).

Particularly noteworthy in this context is that opposition to NATO expansion

was widely shared across the political spectrum, including communists, national-

ists, and liberals (Black 1999). Some observers have suggested that this can be

explained by deep-seated historical animosities toward the alliance and “linger-

ing Cold War attitudes” (Gorenburg et al. 2002, 32 and 33–35). There may be

something to it. Above all, however, Moscow’s opposition to NATO expansion was

driven by geopolitical factors and military-strategic concerns. In the words of then–

foreign minister Yevgeny Primakov, “Russia cannot remain indifferent to the fac-

tor of distance—the Baltic countries’ proximity to our vital centers. Should NATO

advance to new staging grounds, the Russian Federation’s major cities would be

within striking range of not only strategic missiles, but also tactical aircraft” (quoted

in Donaldson and Nogee 2009, 216). Likewise, the Russian scholar Nikolai Sokov

(1999, 18), hardly known to be a hardliner, wrote in a commentary for the Atlantic

Council, “The Baltic states’ membership in NATO would mean U.S. troops in the

immediate vicinity of key Russian political and economic centers, making it par-

ticularly vulnerable to air strikes.” Even some Western analysts acknowledged that

“tactical aircraft operating from Baltic airfields would be within easy un-refuelled

striking distance [of nuclear submarine bases on the Kola Peninsula]. Aircraft

based in the Baltic countries would also be within an hour’s flying time to politi-

cal and military command centres in the Moscow and St. Petersburg metro areas”

(Grissom 2003, 24).

Western policymakers, for their part, tried to allay Russian fears by asserting that

the alliance had no aggressive intentions. In May 1997, moreover, the NATO-Russia

Founding Act was signed, which stated that NATO did not intend to deploy sig-

nificant numbers of troops or nuclear weapons on the territory of new members.

Notwithstanding these assurances, policymakers in Moscow remained deeply suspi-

cious. After all, intentions could change and, in the event of a conflict, NATO could

rapidly establish forward-operating sites and military infrastructure on the territory

of the Baltic states (Sokov 1999, 13–15). To quote, once again, then–foreign minis-

ter Primakov, “If NATO . . . comes to engulf the territory of the Warsaw Pact, from

our point of view, the geopolitical situation will deteriorate. Why? Because inten-

tions change. . . . Obviously I do not believe that NATO will attack us. However, on

a hypothetical level a situation might emerge in which we will be forced to act in a

way which is not in our best interest” (quoted in Wolczuk 2003, 120).

In short, the cooperation of the Baltic states with the US-led NATO alliance in-

creased the level of external pressure on Russia. Thus, going by a purely structural

perspective, one would expect that Moscow resorted to coercive tools and tactics vis-

à-vis the Baltics to prevent them from joining the alliance and, if possible, to gain

greater influence over their foreign-policy orientation.

State Capacity

On the domestic level, the Russian state was marred by a number of problems

throughout the 1990s. One of the most serious problems was the inability to raise

revenues and collect taxes. As one scholar pointed out, “In 1996 only 16 percent

of companies and organizations were without serious tax trespasses and 34 percent

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

10 Enemy at the Gates

did not pay taxes at all” (Puheloinen 1999, 31). Moreover, and partly as a result

of this, the ratio of tax revenues-to-GDP declined from 20.3 percent in 1992 to 9.2

percent in 1998, even though Russia’s economy substantially contracted over the

same period (Orban 2008, 26). Meanwhile, the work of tax inspectors had become

an increasingly dangerous occupation in Russia. “In 1996 alone,” one report noted,

“26 tax collectors were killed, 74 wounded, 6 kidnapped, and 41 burned out of their

homes” (Chang 1999, 80). In short, the tax-collection system was in tatters. On top

of that, there was widespread capital flight. As a result, government authorities in

Moscow lacked resources to finance major policy programs (Oliker and Charlick-

Paley 2002, 27–33; Treisman 1998).

Equally detrimental was the lack of state autonomy. In the mid-1990s, Russian

business tycoons—known as “oligarchs”—acquired control of many of the country’s

most lucrative assets. In parallel, they began expanding their influence into the

political sphere. Of course, lobbying activities are common to most countries in

the world. In Russia, however, the problem was that some oligarchs had become so

powerful that they were able to capture parts of the state machinery. For instance,

Vladimir Potanin was appointed to serve as Russia’s first deputy prime minister in

1997. Another case in point is Boris Berezovsky, who became deputy secretary of

the Russian Security Council. In effect, business tycoons played an important role

in the formation of Russian state policy (McFaul 1998, 318–19; Schroder 1999).

In addition, Russia fragmented along regional lines. The Chechnya problem was

merely the most obvious example. A number of regional entities within Russia sat

up their own border posts and began establishing state-like structures. Some regions

even created “ministries” for external relations and began conducting their own,

semi-independent foreign policies. Tatarstan, for instance, refused to send its con-

scripts outside the republic and supported NATO’s military intervention in Kosovo

(Oliker and Charlick-Paley 2002, 11–16; Perovic 2000). In short, regional entities

undermined the authority and autonomy of the foreign policy executive in Moscow.

Russia’s Baltic Policy in Action

Defense planners in Moscow stressed that the Baltic region was of utmost geopo-

litical importance to Russia, both because of military installations in the area and

because of lines of communication and trade routes (Puheloinen 1999, 55–66 and

74–80). Accordingly, they wanted to maintain some influence over the foreign-

policy orientation of the Baltic states. Members of the Russian foreign policy ex-

ecutive proposed a number of steps to achieve this aim.

In 1997, for instance, President Yeltsin laid out a plan according to which Russia

would provide security guarantees to the Baltic states. In return, they should pledge

to abstain from joining any military bloc or organization, effectively leading to a

Finlandization of the area (Black 1999, 256–58; Herd 1999a, 201–2; Sleivyte 2010,

129–30). In parallel, Moscow issued thinly-veiled threats. For example, Russian

Deputy Foreign Minister Nikolai Afanasievski warned that a Baltic bid for NATO

membership “would not serve the interests of their security, and on the contrary

would create immense tensions” (quoted in Ziugzda 1999, 9). Members of the Rus-

sian foreign policy executive also threatened to station nuclear weapons in Kalin-

ingrad and beef up the Baltic Sea Fleet. According to documents leaked to the

press, there were even contingency plans to invade the Baltics if they joined NATO

(Clemens 2001, 188–89; Lieven 1996, 175; Sergounin 1997, 333–34; Sleivyte 2010,

132–33).

The assertive rhetoric of Russian officials corresponds well with the growing level

of external pressure. Words, however, were not matched by deeds. To be sure, Russia

brought to bear some economic pressure on the Baltics. Moreover, Moscow stalled

border treaties with Latvia and Estonia and missed no opportunity to complain

about the mistreatment of Russian-speaking communities there. This had partly to

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

ELIAS GÖTZ 11

do with genuine concern for its compatriots and partly with instrumental reasons.

After all, Russian strategists knew fairly well that countries with unresolved border

disputes or ethnic conflicts were unlikely to be included into NATO (Oldberg 2003,

21–23 and 33–34; Sokov 1999, 12; Väyrynen 1999, 221). For the most part, however,

relatively little happened. Indeed, as the level of external pressure increased and

the Baltics established ever-closer ties with NATO in the late 1990s, Russia’s behavior

became more inchoate and less assertive. This can be explained by the lack of state

capacity, which impaired Russia’s ability to pursue an assertive policy vis-à-vis the

Baltics in three major ways.

First of all, the fall in tax income amplified the need for military cutbacks and

downsizing. In 1998, for example, Moscow reduced its troops in the St. Petersburg

Military District and the country’s northwestern region, which abuts the Baltic area,

by more than 40 percent. Moscow also considerably reduced the size of Russian

forces stationed in Kaliningrad (Freudenstein 2015, 121; Oldberg 2003, 30; Sleivyte

2010, 130; Ziugzda 1999, 12–13). Of course, the sorry state of Russia’s economy

must be taken into account as well. However, in terms of material capabilities and

power resources—such as money and manpower—Russia hovered like a giant over

the Baltic states. The main problem was that the Russian state lacked the capacity

to extract these resources from society. This led to a “hollowing out” of the mili-

tary. As one observer reported, “In 1997 the military received only 56 percent of its

budgeted appropriation. It was given only 43 percent of its budget allocation for

medical services, 41 percent of monies earmarked for clothing and equipment, and

only 50 percent of what was promised to feed its soldiers” (Herspring 1998, 325).

As a result, Russia’s fighting power and its ability to conduct military operations was

limited. Indeed, in November 1998, the Duma Defense Committee concluded that

“the armed forces are in the deepest imaginable crisis, which is effectively full-scale

disintegration, and unable . . . to carry out strategic operations” (quoted in Herd

1999b, 265). In short, weak extraction capacity hampered Russia’s ability to exert

military pressure on the Baltic states.

Second, oligarchs and their financial-industrial groups affected and, at times,

counteracted the Kremlin’s policy toward the Baltics. In the summer of 1998, for

example, Moscow decided to impose sanctions on Latvia. Many Russian companies,

however, continued to trade with Latvia and thus undermined official state policy

(Sokov 1999, 28–30). Another example occurred in late 1998, when the Lithua-

nian government decided to sell a major stake in the Mazeikiai refinery complex,

the largest in the Baltics, to the US company Williams International and not to

Russia’s state-affiliated company Lukoil. The Kremlin responded by cutting off oil

supplies to Lithuania. Yet, at the same time, Russia’s largest private energy company,

Yukos, began cooperating with Williams International and expanded its operations

in Lithuania (Krickus 2006, 23–25; Oldberg 2003, 56–59). The details of the case

are complex, but the larger point is simple: oligarch-owned energy companies acted

sometimes at cross-purposes with Russia’s state-affiliated companies in neighboring

countries. This undermined Moscow’s ability to exert economic pressure on the

Baltics (Herd 1999a, 202–3).

Third, Russia’s Baltic policy was impaired by the decentralization of power. Re-

gional entities in northwestern Russia (Pskov, Novgorod, Leningrad, and Karelia)

began to develop their own foreign policies. Some regions even “signed their own

agreements with the Baltic states” (Olberg 2003, 58). Needless to say, this made it

very difficult for government authorities in Moscow to pursue a cohesive and as-

sertive policy in the Baltic area.

The domestic constraints that affected Moscow’s Baltic policy were reflected in

Russia’s 1997 Security Concept. While the expansion of extraregional powers to-

ward Russian borders figured prominently in the document, as mentioned above,

the concept stressed that the most pressing and immediate threats facing Russia

“are of predominantly internal nature” (RF 1997, 9). Accordingly, the incoming

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

12 Enemy at the Gates

Putin administration committed itself to solve the country’s internal problems and

placed a high priority on strengthening the Russian state apparatus. At least un-

til 2003, however, Russia remained weak in terms of extraction capacity and state

autonomy. Moreover, the efforts to rebuild the state diverted attention and re-

sources from foreign-policy issues. The perhaps most graphic example is the second

Chechen war, which tied up not only many of Russia’s most capable fighting units

but also money and political capital. Thus, when NATO announced the admission

of the three Baltic states in November 2002, many Kremlin officials kept a relatively

low profile (Gorenburg et al. 2002, 35–36; Kramer 2002, 747–749; Oldberg 2003,

26–27).

Summing up: Lack of state capacity hobbled Moscow’s attempts to pursue a co-

herent and combative policy toward the Baltics in the face of growing external pres-

sure. Instead, drift and self-contradictions characterized Russian behavior through-

out the latter half of the 1990s and early 2000s. This, however, would soon change.

Phase II: Russia’s Baltic Policy, 2004–Present

From 2004 onward, Russia began to systematically apply a number of policy tools—

including military provocations, economic sanctions, propaganda campaigns, cyber-

attacks, and domestic political interferences—to destabilize the Baltic states. Yet, at

the same time, Russia has abstained from direct military actions. How can one ex-

plain this pattern of behavior? The answer, I argue, is found in the interplay of

external pressure and the strengthening of Russian state capacity.

External Pressure

In 2004, the Baltic states officially joined NATO, much to Moscow’s dismay. Rus-

sian defense officials were particularly concerned about the possibility that NATO

would construct military facilities in the region. This concern was expressed repeat-

edly in security planning and defense documents. For example, the 2000 National

Security Concept identified as a main threat “the possible emergence of foreign

military bases and major military presences in the immediate proximity of Russian

borders” (RF 2000a, 5). Likewise, the 2000 Military Doctrine warned of the “cre-

ation (buildup) of groups of troops . . . close to the Russian Federation’s state bor-

der” (RF 2000b, 3). Similar threat assessments can be found in subsequent Military

Doctrines and National Security Concepts. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that

Moscow emphasized in the run-up to NATO’s 2004 enlargement that it would “not

tolerate the US-led military alliance stationing troops or equipment in the Baltic

states” (Dempsey 2004).

In accordance with the Founding Act, NATO refrained from deploying substan-

tial combat forces in the Baltic states. This helped to allay some of the worst Russian

fears. Nonetheless, after the Baltic states had joined the alliance, NATO immedi-

ately launched the Baltic Air Policing mission and stationed a handful of fighter jets

at the Siauliai airbase in northern Lithuania. Furthermore, NATO installed in all

three Baltic states modern air surveillance and radar systems that “can look deep

into Russia” (Sleivyte 2010, 150). Russian policymakers protested vocally against

these moves. To be clear, government officials in Moscow did not expect that NATO

would attack their country “tomorrow.” The concern was that the alliance, in the

event of a crisis, could use the Baltic region as a staging area for military operations

against Russia (Sleivyte 2010, 133–34).

From a military-strategic perspective, the Baltics’ entry into NATO undoubtedly

increased Russia’s vulnerabilities and limited its possibilities to project power into

the Baltic Sea region. To put it into the terms of my neoclassical realist theory, the

level of external pressure was high. But, at the same time, Baltic membership in

NATO meant that Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were now covered by the alliance’s

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

ELIAS GÖTZ 13

Article V collective defense provision, according to which an attack on one mem-

ber is considered an attack on all. In other words, the Baltics had obtained a de

facto security guarantee from a major extraregional power: the United States. This

provided a strong disincentive for Russia to apply direct military force against the

Baltics—more on which below.

State Capacity

As noted in the previous section, the rebuilding of the Russian state became the

top priority during the first term of Putin’s presidency. Toward this end, the Putin

administration adopted a three-part strategy.

First, the Putin administration worked hard to strengthen the state’s extraction

capacity. Among other things, it introduced a new tax code; it removed tax con-

cessions that had been granted to regional entities during the Yeltsin years; and it

restructured the Federal Tax Service. As a result, the ability of the state to collect

taxes improved greatly (Oliker and Charlick-Paley 2002, 19; Tsygankov 2014, 118–

19; Yakovlev 2006, 1042–43). According to one statistic, the ratio of tax revenues-

to-GDP increased from 9.2 percent in 1998 to 24.5 percent in 2006 (Orban 2008,

26).

Second, the Putin administration took several steps to increase the Kremlin’s

control over regional entities. For example, it divided the country’s 89 regions

into seven super-districts headed by presidential envoys; it reformed the Federation

Council (the upper house of the Russian parliament); and it introduced a contro-

versial law that allowed the Russian president to appoint governors. Some of these

measures were more successful than others. Overall, however, there is no question

that Putin’s reforms contributed to strengthen the federal center vis-à-vis the re-

gions (Oliker and Charlick-Paley 2002, 16–20; Ross 2005; Tsygankov 2014, 109–11).

Third, the Putin administration reined in the oligarchs, at least those not loyal

to the Kremlin. The best example is the prosecution of Mikhail Khodorkovsky and

the dismemberment of his energy empire Yukos (Tompson 2005; Tsygankov 2014,

106 and 120–25). Relatedly, Putin and his team sought to reassert state control over

strategic branches of the economy—including energy production, arms manufac-

turing, aerospace, and mining. To that end, the Kremlin placed representatives on

the boards of the country’s largest companies and corporations. This prompted one

observer to quip that “state capture gave way to business capture” (Sakwa 2008, 189;

also see Hanson and Teague 2005; Yakovlev 2006).

By introducing these measures, many of which had an authoritarian ring, the

Putin administration managed to strengthen the Russian state in a relatively short

period of time. There is no denying that Putin’s state-building project was driven

in part by the effort to consolidate his personal power. As the late Charles Tilly

(2007, 137) put it, “Putin’s regime was aggressively expanding state capacity as it

squeezed out democracy.” Indeed, some scholars have suggested that Putin’s turn

toward authoritarianism is the root cause of Moscow’s increasingly assertive policies

in the post-Soviet space (see, e.g., Ambrosio 2009). The argument advanced here

is different. Putin’s authoritarian tendencies are not the root cause but rather a

facilitating factor, in the sense that they have allowed the Russian government to

rebuild state capacity within a short time span. This, in turn, has enabled Moscow

to act upon external pressures and opportunities in a more systematic fashion.

Russia’s Baltic Policy in Action

The Putin administration needed the first years in office to strengthen the Russian

state. As described above, the Kremlin’s policies in the Baltics remained incoherent

during this time. By around 2004, however, the state had become a more unified ac-

tor and was able to curtail the international activities of Russia’s regions. Especially

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

14 Enemy at the Gates

interesting for the purposes of this paper, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov explicitly

“warned the leaders of Russian regions not to pursue any relations with the Baltic

States that would not be at first endorsed by Moscow” (Sleivyte 2010, 161). Fur-

thermore, the Russian state curtailed the influence of oligarchs. This enabled the

Kremlin to better coordinate the activities between private and state-run businesses

in the Baltic area. Finally, the increase in extraction capacity meant that the cen-

tral government had more financial resources at its disposal to fund major policy

programs. Among other things, it led to a substantial increase in defense spend-

ing, which laid the foundation for the rebuilding and modernization of the Russian

military.

There can be no doubt that Russia had the capacity to conduct military opera-

tions against the Baltics in the latter half of the 2000s. The problem was that the

Baltics had used the window of opportunity provided by Russia’s internal weak-

ness in the previous years to join NATO. Of course, many Balts have questioned

the political will of Washington and other Western governments to honor their

treaty obligations and defend the Baltic states in the event of a Russian attack. From

Moscow’s perspective, however, the calculus is different. There is a nontrivial chance

(or perhaps better, risk) that military operations against the Baltics—either direct

or Crimea-style—will lead to a major confrontation with NATO. Needless to say, this

would be extremely costly and dangerous for Russia. After all, NATO is far superior

to Russia in terms of economic and military capabilities.

In short, the Baltic membership in NATO made the application of military means

very risky. Hence, although there was a high level of external pressure, Moscow

refrained from the use of force. Instead, it began pursuing a four-pronged approach

toward the Baltics to regain some influence.

First of all, Moscow expanded its support for pro-Russian parties in the area. In

Estonia, it cultivated close ties with the Center Party, which represents large sec-

tions of the country’s Russian-speaking community. For instance, state-connected

companies like Russian Railways are believed to have provided campaign funds

to Edgar Savisaar, who until recently was the Center Party’s leader and mayor of

Tallinn (Grigas 2012, 12). Moreover, already in 2004, the Kremlin’s United Russia

party signed a cooperation agreement with the Center Party (Bulakh et al. 2014,

49–52). In Latvia, United Russia signed a cooperation agreement with the center-

left Harmony party. Moscow is also believed to support the pro-Russian fringe party

“Latvian Russian Union” (McDonald-Gibson 2014; Kudors 2014, 76 and 82–84). In

Lithuania, which has no sizeable Russian community, Moscow has extended logisti-

cal and financial support to the country’s Polish minority party. This indicates that

not only ethnonationalist sentiments but also larger politico-strategic interests are

behind Russia’s meddling in the domestic-political affairs of the Baltic countries

(Maliukevicius 2014, 115–23).

Second, and relatedly, Moscow has provided logistical and financial support to

various Russia-friendly groups and societal organizations in the region. For exam-

ple, the state-sponsored Russkiy Mir Foundation has established several centers in

the Baltics and backs pro-Russian NGOs there, such as the Latvian Human Rights

Committee and the Legal Information for Human Rights in Estonia. Likewise, Rus-

sia’s Rossotrudnichestvo agency, which was founded in 2008, has established branches

in all three Baltic states. In parallel, Moscow has stepped up its support for Russian

language schools and Russian-speaking media outlets in the region (Braw 2015;

Bulakh et al. 2014, 40–49; Grigas 2012, 9–10; Persson 2014, 25–27). Of course, not

all Russia-sponsored cultural and social activities in the Baltics are guided by Machi-

avellian calculations of power and influence. Nor can the Russian communities in

the Baltics be simply regarded as a “fifth column” of the Kremlin. Large swathes of

the Baltic Russians have developed their own, distinct identity and interests (Laitin

1998). That said, there can be no doubt that Moscow has tried to use economic and

social grievances of the Baltic Russians for instrumental purposes.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

ELIAS GÖTZ 15

Third, Russia has stepped up its efforts to destabilize the Baltic countries. Per-

haps the best example here is the April 2007 statue crisis, which erupted when Es-

tonian authorities relocated a Red Army memorial from the center of Tallinn to

the outskirts. This decision sparked violent street riots that were reportedly stoked

by members of Night Watch, a right-wing group with ties to Russian authorities,

and the pro-Kremlin youth organization Nashi. What is more, Estonian government

and banking sites became subject to a major cyberattack, which is widely believed

to have originated in Russia (Freudenstein 2015, 121–22; Grigas 2012, 5). Similar

cyberattacks were launched against all three Baltic states in November 2013, dur-

ing a large-scale NATO exercise in Poland (Coffey and Kochis 2015, 9). On several

occasions, moreover, Russia has disrupted trade with the Baltic states. For example,

in the run-up to the EU’s Vilnius summit in November 2013, Russia imposed an

embargo on Lithuanian dairy products (Socor 2013).

Fourth, in lockstep with the rebuilding of Russia’s armed forces, Moscow has in-

creased its military activities in the Baltic area. No doubt, the number of Russian

air incursions has shot up in recent years. But it is nothing entirely new. Over the

course of the last decade, Russian planes have repeatedly violated Baltic airspace.

In one particularly spectacular incident, which occurred in October 2005, a Russian

SU-27 fighter jet crashed near Kaunas in Lithuania (Ehin and Berg 2009, 4–5). Rus-

sia also started to boost its military presence in the Kaliningrad exclave, effectively

transforming it into a force-projection platform that can serve both offensive and

defensive purposes (Oldberg 2015). Concurrently, Russia began conducting a num-

ber of large-scale training exercises (e.g., the Zapad 2009, Zapad 2013, and Zapad

2017 military exercises) close to the Baltics (Sleivyte 2010, 146–48). The purpose

of these exercises has been manifold—to test new weapon systems, to practice for

worst-case scenarios, to send a signal to the West—but also to intimidate the Baltic

countries and induce their governments to redirect resources and attention from

domestic challenges. In other words, these maneuvers can be understood, at least

in part, in terms of Russia’s attempts to undermine the internal stability of the Baltic

states.

Summing up: Compared to the previous period, Moscow’s Baltic policy has be-

come more cohesive and assertive since the middle of the 2000s. My analysis sug-

gests that this can be explained by the rebuilding of Russian state capacity, which

enables Moscow to respond more effectively to external pushes and pulls. Still,

Russia has so far abstained from the direct use of force in the Baltic area. This can

be explained by the membership of the Baltic states in NATO, which deters Russia

from carrying out a military intervention in the region.

Conclusion

This article has developed a neoclassical realist theory that explains how the com-

bined impact of systemic imperatives and variations in state capacity shapes the

neighborhood policies of major powers. The previous two sections have shown that

this approach provides a useful prism through which the evolution of Russia’s Baltic

policy can be understood.

How does my neoclassical account of Russia’s Baltic policy compare to the status

perspective outlined in the article’s introduction? As noted, the status perspective

holds that Russia adopted a policy of restraint vis-à-vis the Baltics in the 1990s and

early 2000s as part of its quest for recognition as a coequal partner of the West. By

contrast, my neoclassical account suggests that Russia was unable to pursue a more

assertive policy vis-à-vis the Baltics in these years, although it faced strong systemic

incentives to do so, due to lack of state capacity. In this regard, the two accounts

stand in opposition to one another. Given the limited access to internal policy doc-

uments, transcripts of high-level meetings, and the like, it is difficult to adjudicate

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

16 Enemy at the Gates

between these competing interpretations at present. I leave this important task for

future research.

In other regards, my neoclassical account and the status perspective seem to com-

plement rather than contradict each other. For example, a number of scholars have

documented that in Russian identity discourses the notion of “great power status” is

closely associated with regional spheres of influence and the right to exert control

over neighboring small states (see, e.g., Hopf 2002; Matz 2001). Others have shown

that higher status tends to enhance a state’s ability to influence others and pursue

its strategic interests more effectively in the international arena. As Thomas Volgy

and his coauthors put it, “Attribution of major power status by the community of

states to a handful of others provides members of the club with a form of soft power

with which to complement material capabilities (Volgy et al. 2014, 60–61).” If this is

so, it is not far-fetched to suggest that status concerns and systemic imperatives form

a mutually reinforcing incentive structure that pushes Russia to pursue regional pri-

macy. Future research should investigate and theorize how status and power politics

interact with each other in shaping Moscow’s neighborhood policy.

Moreover, work remains to be done to evaluate the generalizability of the neo-

classical model developed in this article. On the face of it, the fact that Russia has

pursued a more assertive policy since around 2004, not only toward the Baltic states

but in the post-Soviet space more generally, fits well with my neoclassical model.

My model would suggest, for example, that Russia’s military interventions in Geor-

gia (2008) and Ukraine (2014) can be largely explained by the interplay of three

factors: (1) systemic incentives to exert geopolitical control over neighboring coun-

tries, (2) improvements in Russian state capacity under the Putin regime, and (3)

high levels of external pressure emanating from the pro-Western policies adopted

by governments in Tbilisi and Kiev. Of course, additional research is needed to de-

velop this argument in greater detail and test it against the available evidence.

Finally, one could test the portability of my theoretical argument more generally.

That is to say, one could examine how well the theoretical model travels to other

cases—say, the neighborhood policies of the United States or China. In doing so,

one could establish the theory’s scope conditions and, at the same time, learn more

about the commonalities and differences in the neighborhood policies of major

powers.

References

AMBROSIO, THOMAS. (2009) Authoritarian Backlash: Russian Resistance to Democratization in the Former Soviet

Union. Farnham: Ashgate.

BLACK, J. L. (1999) “Russia and NATO Expansion Eastward: Red-Lining the Baltic States.” International

Journal 54, no. 2: 249–66.

BLANCHARD, JEAN-MARC F., AND NORRIN M. RIPSMAN. (2013) Economic Statecraft and Foreign Policy: Sanctions,

Incentives, and Target State Calculations. New York: Routledge.

BRAW, ELISABETH. (2015) “The Kremlin’s Influence Game.” World Affairs (blog), March 10, 2015. Available

at http://www.worldaffairsjournal.org/blog/elisabeth-braw/kremlin%E2%80%99s-influence-game.

(Accessed November 29, 2016.)

BULAKH, ANNA, JULIAN TUPAY, KAREL KAAS, EMMET TUOHY, KRISTIINA VISNAPUU, AND JUHAN KIVIRÄHK. (2014)

“Russian Soft Power and Non-military Influence: The View from Estonia.” In Tools of Destabilization:

Russian Soft Power and Non-military Influence in the Baltic States, edited by Mike Winnerstig. Stockholm:

Swedish Defence Research Agency.

CARPENTER, TED GALEN. (2014) “Are the Baltic States Next?” National Interest (online), March 24, 2014.

Available at http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/are-the-baltic-states-next-10103. (Accessed

December 1, 2016.)

CHANG, FELIX K. (1999) “The Russian Far East’s Endless Winter.” Orbis 43, no. 1: 77–110.

CHIVVIS, CHRISTOPHER S. (2015) “The Baltic Balance: How to Reduce the Chances of War in Europe.” For-

eign Affairs, Snapshot, July 1, 2015. Available at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/baltics/2015-

07-01/baltic-balance. (Accessed December 1, 2016.)

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

ELIAS GÖTZ 17

CINGOLANI, LUCIANA. (2013) “The State of State Capacity: A Review of Concepts, Evidence, and Measures,” Work-

ing Paper Series on Institutions and Economic Growth. Maastricht: Maastricht Graduate School of

Governance.

CLEMENS, WALTER C. JR. (2001) The Baltic Transformed: Complexity Theory and European Security. Lanham:

Rowman & Littlefield.

COFFEY, LUKE, AND DANIEL KOCHIS. (2015) The Baltic States: The United States Must Be Prepared to Fulfill Its

NATO Treaty Obligations, Backgrounder 3039. Washington, DC: Heritage Foundation.

DEMPSEY, JUDE. (2004) “Moscow Warns NATO away from the Baltics.” Financial Times, March 1, 2004.

Available at http://209.157.64.201/focus/f-news/1088568/posts. (Accessed November 28, 2016.)

DONALDSON, ROBERT, AND JOSEPH L. NOGEE. (2009) The Foreign Policy of Russia: Changing Systems, Enduring

Interests (4th ed.). Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

DUECK, COLIN. (2009) “Neoclassical Realism and the National Interest: Presidents, Domestic Politics, and

Major Military Interventions.” In Neoclassical Realism, the State, and Foreign Policy, edited by Steven E.

Lobell, Norrin M. Ripsman and Jeffrey W. Taliaferro. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

EHIN, PIRET, AND EIKI BERG. (2009) “Incompatible Identities? Baltic-Russian Relations and the EU as an

Arena for Identity Conflict.” In Identity and Foreign Policy: Baltic-Russian Relations and European Integra-

tion, edited by Ehin Piret. Farnham: Ashgate.

FREUDENSTEIN, ROLAND. (2015) “Russia and the Baltics.” In The Baltic Security Puzzle: Regional Patterns of De-

mocratization, Integration, and Authoritarianism, edited by Mary N. Hampton and M. Donald Hancock.

Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

GORENBURG, DMITRY, MELISSA HENTON, DEBRA ROEPKE, AND DANIEL WHITENECK. (2002) The Expansion of

NATO into the Baltic Sea Region: Prague 2002 and Beyond. Alexandria: Center for Strategic Studies.

Available at http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/∼gorenbur/cna%20baltic%202002.pdf. (Accessed

November 29, 2016.)

GÖTZ, ELIAS. (2016) “Neorealism and Russia’s Ukraine Policy, 1991–Present.” Contemporary Politics 22,

no. 3: 301–23.

GRIECO, JOSEPH M. (1997) “Realist International Theory and the Study of World Politics.” In New Thinking

in International Relations Theory, edited by Michael W. Doyle and G. John Ikenberry. Boulder: Westview

Press.

GRIGAS, AGNIA. (2012) “Legacies, Coercion and Soft Power: Russian Influence in the Baltic States,” Brief-

ing paper 2012/4. London: Chatham House.

GRISSOM, ADAM. (2003) “The Post-Prague Strategic Orientation of the Baltic States.” In Security Dynamics

in the former Soviet Bloc, edited by Graeme P. Herd and Jennifer D.P. Moroney. London: Routledge.

HANSON, PHILIP, AND ELIZABETH TEAGUE. (2005) “Big Business and the State in Russia.” Europe-Asia Studies,

57, no. 5: 657–80.

HARKAVY, ROBERT E. (2007) Strategic Basing and the Great Powers, 1200–2000. New York: Routledge.

HENDRIX, CULLEN S. (2010) “Measuring State Capacity: Theoretical and Empirical Implications for the

Study of Civil Conflict.” Journal of Peace Research, 47, no. 3: 273–85.

HERD, GRAEME P. (1999a) “Russia’s Baltic Policy after the Meltdown.” Security Dialogue 30, no. 2: 197–212.

——— (1999b) “Russia: Systemic Transformation or Federal Collapse?” Journal of Peace Research 36, no.

3: 259–69.

HERSPRING, DALE R. (1998) “Russia’s Crumbling Military.” Current History 97, October 1998: 325–28.

HOPF, TED. (2002) Social Construction of International Politics: Identities and Foreign Policies, Moscow, 1955 and

1999. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

HUANG, MEL. (2003) “Security: Lynchpin of Baltic Cooperation.” In Security Dynamics in the former Soviet

Bloc, edited by Graeme P. Herd and Jennifer D.P. Moroney. London: Routledge.

HUTH, PAUL. (1988) “Extended Deterrence and the Outbreak of War.” American Political Science Review 82,

no. 2: 423–43.

JERVIS, ROBERT. (1978) “Cooperation under the Security Dilemma.” World Politics 30, no. 2: 167–214.

KNUDSEN, OLAV F. (1988) “Of Lambs and Lions: Relations between Great Powers and Their Smaller Neigh-

bors.” Cooperation and Conflict 23, no. 2: 111–22.

KRAMER, MARK. (2002) “NATO, the Baltic States and Russia: A Framework for Sustainable Enlargement.”

International Affairs 78, no. 4: 731–56.

KRASNER, STEPHEN D. (1978) Defending the National Interest: Raw Materials Investments and U.S. Foreign Policy.

Princeton: Princeton University Press.

KRICKUS, RICHARD J. (2006) Iron Troikas: The New Threat from the East. Carlisle: Strategic Studies Institute.

KUDORS, ANDIS. (2014) “Russian Soft Power and Non-Military Influence: The View from Latvia.” In Tools

of Destabilization: Russian Soft Power and Non-Military Influence in the Baltic States, edited by Mike Win-

nerstig. Stockholm: Swedish Defence Research Agency.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/fpa/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/fpa/orx011/4601762

by University of New England user

on 09 January 2018

18 Enemy at the Gates

LAITIN, DAVID D. (1998) Identity in Formation: The Russian-Speaking Populations in the Near Abroad. Ithaca:

Cornell University Press.

LARSON, DEBORAH WELCH, AND ALEXEI SHEVCHENKO. (2014) “Russia Says No: Power, Status, and Emotions in

Foreign Policy.” Communist and Post-communist Studies 47, no. 3–4: 269–79.

LIEVEN, ANATOL. (1996) “Baltic Iceberg Dead Ahead: NATO Beware.” The World Today 52, no. 7: 175–9.

LUCAS, EDWARD. (2015) The Coming Storm, Baltic Sea Security Report. Washington, DC: Center for European

Policy Analysis.

MACFARLANE, NEIL. (2003) “Russian Policy in the CIS under Putin.” In Russia Between East and West: Russian

Foreign Policy on the Threshold of the Twenty-First Century, edited by Gabriel Gorodetsky. London: Frank

Cass.

MALIUKEVICIUS, NERIJUS. (2014) “Russian Soft Power and Non-military Influence: The View from Lithua-

nia.” In Tools of Destabilization: Russian Soft Power and Non-military Influence in the Baltic States, edited by

Mike Winnerstig. Stockholm: Swedish Defence Research Agency.

MANN, MICHAEL. (1984) “The Autonomous Power of the State: Its Origins, Mechanisms and Results.”

European Journal of Sociology 25, no. 2: 185–213.

MATZ, JOHAN. (2001) Constructing a Post-Soviet International Political Reality: Russian Foreign Policy towards the

Newly Independent States, 1990–95. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

MCDONALD-GIBSON, CHARLOTTE. (2014) “Latvia Wary of its Ethnic Russians as Tensions with Moscow Rise.”

Time, October 3, 2014. Available at http://time.com/3456722/latvia-election-russia-ukraine/. (Ac-