Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Inclusive - Assignment 1

Загружено:

api-408538345Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Inclusive - Assignment 1

Загружено:

api-408538345Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

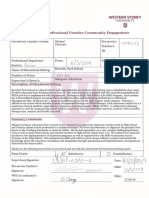

Inclusive Assignment 1

Discuss the inclusion of students with

ASD and/or disabilities in my practice.

Michael Carmona

15090573

Inclusive Education - Theory, Policy & Practice. Unit 102084

Question:

Why the inclusion of students with ASD and

disabilities in the classroom is important for all

students, teachers, school organisations and

society.

There has been a seismic shift in education over the last few decades for the inclusion of

students with various forms of learning difficulties and/or disabilities within the mainstream

Michael Carmona 15090573 Inclusive Education Assignment 1

classroom of students. The reason for this transition is due to almost 40 years of research

demonstrating the benefits of inclusive teaching practices and the failures of the segregation

of students with additional needs/disabilities (Kurth, Lyon & Shorgren, 2015). One of the

most prevalent forms of additional needs in today’s society is the Autism Spectrum Disorder

(ASD), which is estimated to be attributed to approximately 1-2% of all students today

(Cappe, Bolduc, Poirier, Popa-Roch & Boujut, 2017). With these two key findings in mind,

the importance of incorporating inclusive teaching practice in our education systems is

critical, not only for the success of my teaching practice, but for students, teachers, school

communities, and for the benefit of society as a whole. This essay will discuss why it is

important to these four key stakeholders (students, teachers, schools and society) that our

education systems incorporate inclusive teaching practices, with a specific focus on special

needs students with ASD and disabilities (more so than students with learning difficulties and

other variations of diversity from mainstream students). In doing so, it will also use examples

of some teaching tools and techniques that can help create inclusive classrooms, that I can

apply in my teaching method (HSIE), to demonstrate the effectiveness and potential of

inclusive classrooms.

Students are the primary stakeholders in our education systems, and therefore, they are the

primary stakeholders to consider when it comes to inclusive school practices (Shorgren et

al., 2015). Therefore our discussion needs to start with them. In the Australian context, the

evidence suggests that more than 3.5% of students currently have some form of disability

(Davis, 2012). Given this significant proportion, our teaching practices need to be broad

enough as to not leave any of these students behind. Legally, it is an obligation, as

according to The Disability Standards for Education 2005, all providers of education in

Australia are required to provide the same quality teaching to students with disabilities, as

the rest of the student population (Australian Government, 2005). Australian teachers need

to ensure that students with ASD and disabilities are not only present in the classroom, but

are receiving the same level of education and teaching as any other student. To do this, we

need to incorporate inclusive teaching practices. Inclusive teaching can be defined as a

class where there is “full membership in the regular classroom, and all children with

disabilities spend the vast majority of their time and participate in all class activities, even if

these need to be modified” (Loreman, 2007). The key to this definition of inclusive teaching

is in the term ‘modified’. What Tim Loreman is referring to here is the modification of our

teaching practices or activities to best accommodate the student. Inclusive is not the same

thing as assimilation or normalisation, in that, we are not trying to improve or make changes

to the students with ASD and disabilities and make them more like their non-disabled/non-

ASD classmates, but rather teachers are adjusting their approaches and techniques to

ensure every student , regardless of their skills and abilities, are given the best learning

opportunities (Kinsella, 2018). A common example of an approach to use to have inclusive

classrooms is the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) approach, which is a flexible

approach to curriculum design to accommodate the needs of students while still maintaining

high achievement expectations for all students (Rapp, 2014). At its core, UDL involves

allowing for multiple means of engagement with students (different ways to provide teaching

to students e.g. group vs individual work or structured vs unstructured etc.), multiple means

of representation (variation of presentation of classroom content) and multiple means of

expression (ways for students to demonstrate understanding) (Moore, 2007). Using UDL

gives all students, not just ones with ASD or disabilities, the best opportunities to learn, and

demonstrate their learning, because it allows them to utilize the skills they possess, and not

Michael Carmona 15090573 Inclusive Education Assignment 1

limit them to a predetermined set of standards that could exclude them. An example that I

could use in my method is with students potential to demonstrate knowledge of different

curriculum outcomes. By allowing students to demonstrate their understanding of different

HSIE syllabus content in a variety of ways, I am including all students, some of whom may

have strengths in written work, others in verbal presentations, some may prefer public

presentations while some prefer the opportunity to showcase their understanding in a one-

on-one condition with the teacher. It is therefore in the interest of teachers to use inclusive

pedagogical approaches like UDL, because the evidence has shown that these approaches

actually benefit all students in the class (Florian and Linklater, 2010), and hence allows the

teachers to teach are their optimal potential.

Teachers are the most important resources in the Australian educational networks, as they

have the ability to have the greatest educational impact on students, from within these

educational environments (the schools or classrooms) (AITSL, 2011). Because of their

position, a teachers ability (or lack thereof) will be the one of the most important determining

factors to how inclusive our classrooms can be. Studies have shown that when teachers

have positive attitudes towards the challenges of having students with ASD and disabilities

included in your classroom activities, and take responsibility for their learning, the chances of

creating effective inclusive classrooms increase (Gilor & Katz, 2018). Teachers hold the

balance of power here, and a lot of it has to do with their attitudes towards inclusive

teaching. If the teachers do not believe it is an essential part of today's education system,

the chances are inclusive teaching practices will not work in their classroom, or for their

students. It is also important to note here that what is crucial for teachers is that they know

and can utilize a variety of inclusive pedagogical teaching tools, rather than have an

extensive knowledge of the variety of learning diversity that can be found in a classroom

(e.g. know the specifics of ASD and other disabilities) (Kinsella, 2019). Teachers do not

need to know the specifics of a students diagnosis, because what teachers should be

interested in more, is what abilities the students do have and how can they as the teacher

best use these strengths to educate them. As long as they know how and when to apply

these different approaches, teachers should still be able to get the most out of every student

in their classroom. Of course, one of the major challenges to the movement towards

inclusive education is the lack of awareness from many current teachers of the potential

positive effects it can have for all students, not just those with special needs. This is because

the value of inclusive teaching has only gradually been incorporated into teacher training

since the late 90’s (Grskovic & Trzcinka, 2011), and most of the teachers who trained before

this time, would still be of the mindset of the importance of segregated classrooms.

Hopefully, as a new trained teacher entering this profession, I will be able to incorporate

inclusive practices in my teaching of HSIE, and demonstrate to other professionals the

benefits of inclusivity to other teaching professionals, because inclusive teaching is a

practice that works best when it is incorporated into the culture of the whole school.

Questions may need to be asked as to what the priorities of our schools systems in society

are, if the successful incorporation of inclusiveness are to be fully utilized. Because schools

seem to be continually battling between different priorities placed on them by society, be that

to be an agent of social change or a production line of qualified citizens etc. (Forlin, Watkins

& Meijer, 2016). As discussed previously, inclusion is not a synonym for assimilate or

normalise (Kinsella, 2019), but about having high expectations for every student (NSW

Department of Education, 2010), regardless of what that level may be. Teachers are

Michael Carmona 15090573 Inclusive Education Assignment 1

responsible for the learning of all students, with today’s social expectations being that those

with diagnoses like ASD etc. are still catered for (not just to be able to focus on mainstream

students and have them perform high academically). But what if students who are high on

the Autism spectrum or have severe disabilities, are limited to how high they can achieve

academically? Are schools supposed to focus on academic achievement only, or individual

achievement overall? It can be argued that they need to focus on both, but schools are

continually challenged with an ever increasing amount of responsibility while seemingly

dealing with a declining pool of funding (Kennedy et al., 2012). This seemingly continual

conflict of interest can severely impact a schools ability to focus on and incorporate inclusive

practices that seem to contradict the pre-existing ideals that schools should normalise

students and focus students on achieving high standards (Grskovic & Trzcinka, 2011). When

schools can choose to focus on being centres for equal learning for all students, and remove

themselves from the competitive educational environment they sometimes find themselves

in (Slee, 2013), they can focus on introducing school wide inclusive practices, that will have

the potential to build off the individual work of teachers already using inclusive practices in

their own classes (Rowe, Stewart & Patterson, 2007). Examples of this could include

educating all teachers (school wide) of instructional strategies that can be catered to

individuals and optimize opportunities to learn for students, and have this be used across

disciplines and years, as research has shown this can be highly effective teaching method

(especially for students with ASD) (Mitchel, 2014) and is a highly valued strategy by teachers

(Grskovic & Trzcinka, 2011). When schools are able to focus on being centres that aim for

the best from every student, we can fulfill some of the important goals of our wider society.

Using an international definition for inclusive education from the International Conference on

Educations 2008, we can see it as the continual process by which diversity is respected and

discrimination is eliminated, with the removal of all barriers thus allowing students to

achieve, both academically and after (as a memebr of the wider society after school life)

(Forlin, Watkins & Meijer, 2016). The goal of inclusive education here, needs to transcend

for life after school. If students are accepted and succeed only in the school world, but fail to

achieve outside of school, has the school system not failed them? Inclusive schools, indeed

all school, should always be charged with the responsibility of empowering students with the

skills and knowledge to best handle themselves in the world that is outside of school (Gilor &

Katz, 2018). In order to have the best chances to achieve this objective for all students, but

especially those with ASD and disabilities, inclusive classrooms are required. Inclusive

classrooms can ensure special needs students achieve the highest they possibly can with

good teaching, while still benefiting the needs to educate mainstream students (Florian and

Linklater, 2010). And with the success of UDL teaching principles have had in classrooms

over the past few decades, has resulted in UDL ideals starting to influence policies for the

wider education networks, to try and create larger scale applications of the strategies

(Edyburn, 2010). Here we can see that the ideals that form inclusive education principles are

not only impactful to students with special needs like ASD or other disabilities, but have

wider applications that can benefit all students in schools.

The transition that has occurred in education is a significant one. Attitudes are still moving,

but the ideals have clearly been researched and proven, that inclusive education is a

principle that works for all students in the classroom. All students can benefit from the

application of inclusive pedagogies, as all students have a variety of strengths and

weaknesses, regardless of whether they would have been categorized as mainstream or

Michael Carmona 15090573 Inclusive Education Assignment 1

special needs classrooms. Therefore, these inclusive principles have much wider

applications for teachers, and can only help them in their professional life, with or without the

presence of so-called special needs students. Schools can flourish when they are

empowered to embrace inclusive education, and society acknowledges their critical role in

the development of all students, regardless of their strengths or weaknesses, and educate

them to achieve the best they can out of life.

Reference list

AITSL, A. (2011). Australian professional standards for teaching | Australian Institute for

Teaching and School Leadership. [online] Aitsl.edu.au. Available at:

https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/national-policy-framework/australian-

professional-standards-for-teachers.pdf?sfvrsn=5800f33c_64 [Accessed 14 Aug. 2019].

Australian Government (2005). Disability Standards for Education 2005.

Cappe, Bolduc, Poirier, Popa-Roch, & Boujut. (2017). “Teaching students with Autism

Spectrum Disorder across various educational settings: The factors involved in burnout.”

Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 498-508.

Michael Carmona 15090573 Inclusive Education Assignment 1

Davies, M. (2012). Accessibility to NAPLAN Assessments for Students With Disabilities: A

'Fair Go'. The Australasian Journal of Special Education, 36(1), 62-78.

Edyburn, D. (2010). Would You Recognize Universal Design for Learning if You Saw it? Ten

Propositions for New Directions for the Second Decade of UDL. Learning Disability

Quarterly, 33(1), 33-41.

Florian, L., & Linklater, H. (2010). Preparing teachers for inclusive education: Using inclusive

pedagogy to enhance teaching and learning for all. Cambridge Journal of Education, 40(4),

369-386.

Forlin, C., Watkins, A., & Meijer, C. (2016). Implementing Inclusive Education : Issues in

Bridging the Policy-Practice Gap (Vol. 8). Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

Gilor, O., & Katz, M. (2018). From normalisation to inclusion: Effects on pre-service teachers’

willingness to teach in inclusive classes. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1-16.

Grskovic, J., & Trzcinka, S. (2011). Essential Standards for Preparing Secondary Content

Teachers to Effectively Teach Students with Mild Disabilities in Included Settings. American

Secondary Education, 39(2), 94-106.

Kennedy, M., Ely, E., Thomas, C., Pullen, P., Newton, J., Ashworth, K., . . . Lovelace, S.

(2012). Using Multimedia Tools to Support Teacher Candidates’ Learning. Teacher

Education and Special Education, 35(3), 243-257.

Kinsella, W. (2019). Organising inclusive schools. International Journal of Inclusive

Education, 1-17.

Kurth, J., Lyon, K., & Shogren, K. (2015). Supporting Students With Severe Disabilities in

Inclusive Schools: A Descriptive Account From Schools Implementing Inclusive Practices.

Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 40(4), 261-274.

Loreman, T. (2007). Seven Pillars of Support for Inclusive Education: Moving from "Why?" to

"How?". International Journal of Whole Schooling, 3(2), 22-38.

Moore, S. (2007). Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age: Universal Design for Learning.

Educational Technology, Research and Development, 55(5), 521-525.

NSW Department of Education (2010). Every Student, Every School. Available at:

https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/disability-learning-and-

support/personalised-support-for-learning/eses [Accessed 14 Aug. 2019].

Rapp, W. (2014). Universal Design for Learning in Action : 100 Ways to Teach All Learners.

Baltimore: Brookes Publishing.

Rowe, F., Stewart, D., & Patterson, C. (2007). Promoting school connectedness through

whole school approaches. Health Education, 107(6), 524-542.

Michael Carmona 15090573 Inclusive Education Assignment 1

Shogren, K., Gross, J., Forber-Pratt, A., Francis, G., Satter, A., Blue-Banning, M., & Hill, C.

(2015). The Perspectives of Students With and Without Disabilities on Inclusive Schools.

Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 40(4), 243-260.

Slee, R. 2013. “How do we Make Inclusion Happen when Exclusion is a Political

Predisposition?” International Journal of Inclusive Education 17 (8): 895–907.

Michael Carmona 15090573 Inclusive Education Assignment 1

Вам также может понравиться

- Discipline Strategies and Interventions PDFДокумент28 страницDiscipline Strategies and Interventions PDFduhneesОценок пока нет

- Inclusive 1500wДокумент6 страницInclusive 1500wapi-478725922Оценок пока нет

- Assignment 3 - Reflection of PracticeДокумент7 страницAssignment 3 - Reflection of Practiceapi-295583127Оценок пока нет

- Inclusive - Changing View of Inclusive in The ClassroomДокумент12 страницInclusive - Changing View of Inclusive in The Classroomapi-435765102Оценок пока нет

- Differentiation and Inclusion For PortfolioДокумент16 страницDifferentiation and Inclusion For Portfolioapi-445524053Оценок пока нет

- Classroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 ClassroomsОт EverandClassroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 ClassroomsОценок пока нет

- Inclusive EducationДокумент10 страницInclusive Educationapi-435783953Оценок пока нет

- PERSONAL DATA SHEETДокумент7 страницPERSONAL DATA SHEETJonna Velasquez33% (3)

- Assignment 1-InclusiveДокумент10 страницAssignment 1-Inclusiveapi-357692508Оценок пока нет

- Inclusive EssayДокумент9 страницInclusive Essayapi-321113223Оценок пока нет

- Assessment 1 and 3 - Inclusive EducationДокумент16 страницAssessment 1 and 3 - Inclusive Educationapi-554345821Оценок пока нет

- Educators' Challenges of Including Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream ClassroomsДокумент17 страницEducators' Challenges of Including Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream ClassroomsPotung Lee100% (1)

- Inclusive Education EssayДокумент8 страницInclusive Education Essayapi-403333254100% (2)

- Curriculum 1a Assessment 2 FinalДокумент15 страницCurriculum 1a Assessment 2 Finalapi-408538345Оценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan-CparДокумент2 страницыLesson Plan-CparGeriza Joy Rico33% (3)

- rtl2 - Assessment 1Документ9 страницrtl2 - Assessment 1api-320830519Оценок пока нет

- Inclusive EducationДокумент9 страницInclusive Educationapi-285170423Оценок пока нет

- Guide To Creating Inclusive SchoolsДокумент143 страницыGuide To Creating Inclusive Schoolscorey_c_mitchell100% (2)

- Week 1 Differentiates Prime From Composite Numbers. (M4Ns-Iib-66) A. Cognitive B. Psychomotor C. AffectiveДокумент5 страницWeek 1 Differentiates Prime From Composite Numbers. (M4Ns-Iib-66) A. Cognitive B. Psychomotor C. AffectiveKeith KatheОценок пока нет

- Week 36 DLLДокумент14 страницWeek 36 DLLRochelle AbbyОценок пока нет

- Inclusive Education For Students With Disabilities - Assessment 1Документ4 страницыInclusive Education For Students With Disabilities - Assessment 1api-357683310Оценок пока нет

- Inclusive Education EssayДокумент10 страницInclusive Education Essayapi-465004613Оценок пока нет

- Inclusive Education Assignment 1Документ9 страницInclusive Education Assignment 1api-332411347100% (2)

- Lesson Presentation Lesson PlanДокумент3 страницыLesson Presentation Lesson Planapi-280659226100% (1)

- Curriculum ReviewДокумент4 страницыCurriculum Reviewapi-323099162Оценок пока нет

- Annex B - Interim Policy On The Ancillary Tasks of TeachersДокумент7 страницAnnex B - Interim Policy On The Ancillary Tasks of TeachersMARY JERICA OCUPE100% (1)

- (Appendix 3D) COT-RPMS Rating Sheet For MT I-IV For SY 2021-2022 in The Time of COVID-19Документ2 страницы(Appendix 3D) COT-RPMS Rating Sheet For MT I-IV For SY 2021-2022 in The Time of COVID-19Claire Acunin Togores100% (2)

- Incomplete ResearchДокумент12 страницIncomplete ResearchHANNALEI NORIELОценок пока нет

- Assignment 1 LastДокумент6 страницAssignment 1 Lastapi-455660717Оценок пока нет

- James Mclaughlin - 2062389 Educ 4720 Assignment 3 - Diversity and Inclusion Portfolio Define DifferentiationДокумент13 страницJames Mclaughlin - 2062389 Educ 4720 Assignment 3 - Diversity and Inclusion Portfolio Define Differentiationapi-480438960Оценок пока нет

- Complete FormДокумент6 страницComplete Formapi-380584926Оценок пока нет

- Inclusive Workforce Capability IssuesДокумент3 страницыInclusive Workforce Capability Issuesapi-460570858Оценок пока нет

- Atitudinile ProfesorilorДокумент15 страницAtitudinile ProfesorilorVeronica SumanОценок пока нет

- Inclusive Practices Essay Focus Area 4 1Документ8 страницInclusive Practices Essay Focus Area 4 1api-293919801Оценок пока нет

- Assignment 1 EssayДокумент9 страницAssignment 1 Essayapi-355627407Оценок пока нет

- Inclusive Chapter 1Документ6 страницInclusive Chapter 1Mhay Pale BongtayonОценок пока нет

- Khoo 2139664 Assignment 2Документ11 страницKhoo 2139664 Assignment 2Natasha Bonybutt KhooОценок пока нет

- Inclusive 2h2018assessment1 EthansaisДокумент8 страницInclusive 2h2018assessment1 Ethansaisapi-357549157Оценок пока нет

- Alisha Rasmussen - 19059378 - Inclusive Education Assignment 1Документ13 страницAlisha Rasmussen - 19059378 - Inclusive Education Assignment 1api-466919284Оценок пока нет

- Assignment 1 Essay-AprilДокумент7 страницAssignment 1 Essay-Aprilapi-519998613Оценок пока нет

- Inclusive Education - Definition, Examples, and Classroom Strategies - Resilient EducatorДокумент5 страницInclusive Education - Definition, Examples, and Classroom Strategies - Resilient EducatorChristina NaviaОценок пока нет

- Inclusive Education EssayДокумент9 страницInclusive Education Essayapi-355128961Оценок пока нет

- Educational Organization & Management 2 (Updated)Документ15 страницEducational Organization & Management 2 (Updated)brightОценок пока нет

- Assessment Task 1: Inclusive Education EssayДокумент9 страницAssessment Task 1: Inclusive Education Essayapi-374392327Оценок пока нет

- Inclusive Education: What It Means, Proven Strategies, and A Case StudyДокумент6 страницInclusive Education: What It Means, Proven Strategies, and A Case StudyXerish DewanОценок пока нет

- Ensuring Fair and Inclusive Education for All LearnersДокумент5 страницEnsuring Fair and Inclusive Education for All LearnersRegine BarramedaОценок пока нет

- Nclusive Education Essay: Discrimination Act, 1992, and The Disability Standards For Education, 2005, andДокумент8 страницNclusive Education Essay: Discrimination Act, 1992, and The Disability Standards For Education, 2005, andapi-320308863Оценок пока нет

- Sharma 2020 - Preparing To Teach in Inclusive ClassroomsДокумент20 страницSharma 2020 - Preparing To Teach in Inclusive ClassroomsAksa Mariam PouloseОценок пока нет

- Essay: Adaptation of Lesson Plan Incorporating Universal Design For LearningДокумент9 страницEssay: Adaptation of Lesson Plan Incorporating Universal Design For Learningapi-429810354Оценок пока нет

- South African Teachers Attitudes Toward The Inclusion of Learners With Different Abilities in Mainstream ClassroomsДокумент19 страницSouth African Teachers Attitudes Toward The Inclusion of Learners With Different Abilities in Mainstream ClassroomsnabeelaellemdinОценок пока нет

- Develop Your Understanding of Inclusive EducationДокумент4 страницыDevelop Your Understanding of Inclusive EducationYing Ying TanОценок пока нет

- Assignment 1 Inclusive Education EssayДокумент6 страницAssignment 1 Inclusive Education Essayapi-369717940Оценок пока нет

- Special Teaching Approach For Inclusive Education and Inclusive ClassroomsДокумент7 страницSpecial Teaching Approach For Inclusive Education and Inclusive Classroomssimba 2020Оценок пока нет

- Inclusive Education - EssayДокумент7 страницInclusive Education - Essayapi-435769530Оценок пока нет

- Review of LiteratureДокумент19 страницReview of LiteraturePaula Mae Buenaventura LopezОценок пока нет

- Asd Inclusive Ed Essay Mulen Hayley A110751Документ10 страницAsd Inclusive Ed Essay Mulen Hayley A110751api-501465610Оценок пока нет

- Running Head: Teachers and Inclusion 1Документ12 страницRunning Head: Teachers and Inclusion 1api-294310836Оценок пока нет

- Learning Disability ReportДокумент7 страницLearning Disability Reportapi-721672259Оценок пока нет

- Assessment Task OneДокумент8 страницAssessment Task Oneapi-321028992Оценок пока нет

- Las Mejores Prácticas de Inclusión en Educación BásicaДокумент20 страницLas Mejores Prácticas de Inclusión en Educación BásicasdanobeitiaОценок пока нет

- Regine A. Mamac BEEd-2 DirectionДокумент7 страницRegine A. Mamac BEEd-2 DirectionRegine MamacОценок пока нет

- Attitudes of Teachers Towards Inclusive Education inДокумент7 страницAttitudes of Teachers Towards Inclusive Education inabuhaymОценок пока нет

- Dawis Es Action R Jayann Roldan g2Документ4 страницыDawis Es Action R Jayann Roldan g2JAY ANN ROLDANОценок пока нет

- Lehohla 2014Документ15 страницLehohla 2014Social MediaОценок пока нет

- Moving Towards Greater Inclusion in Singapores PRДокумент16 страницMoving Towards Greater Inclusion in Singapores PRFikri OthmanОценок пока нет

- Case Study Analysis On Mainstreaming CSNДокумент12 страницCase Study Analysis On Mainstreaming CSNSherwin AlarcioОценок пока нет

- Inclusive Pedagogy: A transformative approach to reducing educational inequalitiesДокумент10 страницInclusive Pedagogy: A transformative approach to reducing educational inequalitieszainabОценок пока нет

- Action Research Paper FinalДокумент88 страницAction Research Paper Finalapi-377293252Оценок пока нет

- Inclusive AssessmentДокумент5 страницInclusive Assessmentapi-408430724Оценок пока нет

- Inclusive EducationДокумент11 страницInclusive EducationSaidu NingiОценок пока нет

- Research .Proposal by Imran Ali SahajiДокумент7 страницResearch .Proposal by Imran Ali SahajiimranОценок пока нет

- Ass 1 Draft - Final DraftДокумент29 страницAss 1 Draft - Final Draftapi-408538345Оценок пока нет

- Submit 1Документ17 страницSubmit 1api-408538345Оценок пока нет

- Unit Outline 2h - Final SubmitДокумент14 страницUnit Outline 2h - Final Submitapi-408538345Оценок пока нет

- Carmona 102605 Ppce 1 H 2019 ReportfinalДокумент1 страницаCarmona 102605 Ppce 1 H 2019 Reportfinalapi-408538345Оценок пока нет

- RTL Assessment 2 FinalДокумент9 страницRTL Assessment 2 Finalapi-408538345Оценок пока нет

- DTL Assesment 2 - FinalДокумент10 страницDTL Assesment 2 - Finalapi-408538345Оценок пока нет

- Content Vs CapabilitiesДокумент20 страницContent Vs Capabilitiesapi-408538345Оценок пока нет

- Assessment 2 Final - Curriculum 2aДокумент7 страницAssessment 2 Final - Curriculum 2aapi-408538345Оценок пока нет

- Commerce Lesson PlanДокумент6 страницCommerce Lesson Planapi-408538345Оценок пока нет

- Teaching Mathematics Creatively in The Junior Secondary ClassesДокумент6 страницTeaching Mathematics Creatively in The Junior Secondary ClassesGilbert MawufemorОценок пока нет

- The Teaching ProfessionsДокумент4 страницыThe Teaching ProfessionsKimberlyEranaBlancarОценок пока нет

- Book Review JHДокумент3 страницыBook Review JHblueperlaОценок пока нет

- Enhancement of Quality EducationДокумент3 страницыEnhancement of Quality EducationMokhter AhmadОценок пока нет

- Maed ResearchДокумент8 страницMaed ResearchArjay BorjaОценок пока нет

- Wics Model and WHLPДокумент2 страницыWics Model and WHLPBithey BolivarОценок пока нет

- Field Work FormДокумент4 страницыField Work Formapi-534751415Оценок пока нет

- Mary Taylor Resume 2018-2019Документ2 страницыMary Taylor Resume 2018-2019api-400525991Оценок пока нет

- Applications of HCF and LCM To Problem Solving Loreto Abbey DalkeyДокумент35 страницApplications of HCF and LCM To Problem Solving Loreto Abbey DalkeyPrachi ShuklaОценок пока нет

- PCK 126 Unit 3 - TPACK SummaryДокумент2 страницыPCK 126 Unit 3 - TPACK Summarydel143masОценок пока нет

- Makalah Analysis TextbookДокумент27 страницMakalah Analysis TextbookAsril Al FaridziОценок пока нет

- THE TEACHER AS A PERSON IN SOCIETYДокумент26 страницTHE TEACHER AS A PERSON IN SOCIETYAlyza Cassandra MoralesОценок пока нет

- Set A: Professional EducationДокумент12 страницSet A: Professional Educationdahlia marquezОценок пока нет

- African American Vernacular English SubstantifiedДокумент43 страницыAfrican American Vernacular English Substantifiedapi-579874317Оценок пока нет

- Debreli 2016Документ15 страницDebreli 2016JessieRealistaОценок пока нет

- English Spelling Problems Among Students at The University of Dongola SudanДокумент7 страницEnglish Spelling Problems Among Students at The University of Dongola SudanZul4Оценок пока нет

- Reorientation on Blended Learning DeliveryДокумент4 страницыReorientation on Blended Learning DeliveryVisalymor CorderoОценок пока нет

- Tom Cooke CV 2022Документ4 страницыTom Cooke CV 2022Tom CookeОценок пока нет

- ReflictionДокумент7 страницReflictionapi-302422413Оценок пока нет

- Options 10 Class TBДокумент152 страницыOptions 10 Class TBandresmartillo39Оценок пока нет