Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Christ S Side-Wound and Francis Stigmati PDF

Загружено:

yahya333Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Christ S Side-Wound and Francis Stigmati PDF

Загружено:

yahya333Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Yamit Rachman-Schrire

Christ’s Side-Wound and Francis’ Stigmatization

at La-Verna

Reflections on the Rock of Golgotha

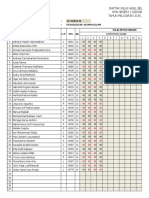

The Rock of Golgotha, the traditional site of Christ’s Crucifixion, is a tall vertical column

of limestone, integrated into the altar of the Chapel of the Crucifixion in the Church of

the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (fig. 1). While mostly hidden within the floor and the

walls of the Church, certain parts of the rock are accessible to a pilgrim’s touch or sight.

In the centre of the altar, the hole where the true cross is believed to have once stood is

framed by a metal disc. The pit itself is not visible, but pilgrims can reach its bottom as

they stretch their hands through the metal disc. To the right and left sides of the altar the

Rock of Golgotha projects above the floor level. Glass windows offer glimpses into the

cleft, believed to have been torn in the rock at the time of the Crucifixion, as narrated in

Matthew 27:51, “And behold the veil of the temple was rent in two from the top even to

the bottom: and the earth quaked and the rocks were rent.”1

The glass windows, which frame the clefts of the rock, are modern, and prevent pil-

grims and believers from touching the rock. However, late medieval accounts testify that

both the cleft and the hole were accessible to pilgrims who used to touch them, lie on

them, and even enter them with their hands, heads, and bodies. This chapter charts the

reception and visuality of the Rock of Golgotha in the late Middle Ages, when the ‘open-

ings’ of the rock – the cleft and the hole – became the focus of pilgrims’ devotional ven-

eration. Following art-historians and historians of visual culture, by ‘visuality’ I refer to a

culturally conditioned and constructed sight.2 Reconstructing the visuality of the rock in

the late Middle Ages allows us to understand the role of the rock in the pilgrims’ experi-

ence of the site of the crucifixion. By drawing the strings between the setting of the rock

in the crusaders’ church and emerging devotional trends in the pilgrims’ homelands, I will

show that pilgrims’ devotional focus on the clefts of the Rock of Golgotha was another

1 “Et ecce velum templi scissum est in duas partes a summo usque deorsum et terra mota est et petrae

scissae sunt.”

2 Hal Foster (ed.): Vision and Visuality, Seattle 1988. For the history of the term ‘visuality’ and further

bibliography, see: Alexa Sand: Visuality, in: Studies in Iconography 33, Special Issue Medieval Art

History Today – Critical Terms (2012), p. 89–95.

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

46 Yamit Rachman-Schrire

1 Chapel of the Crucifixion with the Rock of Golgotha seen through the glass-windows on both

sides of the altar, Jerusalem, Church of the Holy Sepulchre

facet of late medieval devotion to the wounds and blood of Christ. I stress that far from

being ‘merely’ a geographical relic, the Rock of Golgotha constitutes both an object and an

agent of cultural transformations, functioning as a performative object whose meanings

were constantly reformulated in accordance with contemporary views and “ways of seeing”.

The Rock of Golgotha: the clefts as substitutes for the whole

As early as the fourth century, the Rock of Golgotha has been enclosed within the inner

court of the Constantinian complex of the Holy Sepulchre, where it stood in its full height,

naked, under the open skies. Though constituting a prominent topographical form in the

sacred geography of the city, pilgrims’ accounts barely mention the rock and its special

characteristics of colour and texture; instead, they emphasize the cross (either a replica of

the True Cross or a relic of it) which was fixed on top of it.3 In the course of the sixth and

3 For further discussion and references: Yamit Rachman-Schrire: The Rock of Golgotha in Jerusalem

and Western Imagination, in: Hans Aurenhammer and Daniela Bohde (ed.): Spaces of the Passion:

Visions of Space, Places of Remembrance and Topographies of Christ’s Suffering in the Middle

Ages and the Early Modern Period, Hamburg 2015, p. 29–48.

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

Christ’s Side-Wound and Francis’ Stigmatization at La-Verna 47

the seventh centuries, the complex of the Holy Sepulchre underwent various architectonic

alterations. The Rock of Golgotha has been gradually detached from its surroundings, and

a staircase was built beside it leading pilgrims to its top. The spatial and architectonical

transformations visited upon the rock went hand in hand with a shift in the point of view

of the devotees, who could now gaze closely at the rock, towards its surface, acquiring knowl-

edge on its specific morphological features. The Pseudo-Antoninus, whose account is

dated ca. 570, mentions the bloodstain of Christ that was visible on the rock, and the crack

shown next to the altar, into which one could throw an apple or anything else that will

float, and then pick it up in Siloam.4 Narratives that were formerly associated with the

Jewish Temple, including the burial place of Adam and Isaac’s sacrifice, were trans-located

to the Rock of Golgotha and to the compound of the Holy Sepulchre, perceived now as the

New Christian Temple of the City.5 A close reading of pilgrims’ accounts from this period

suggests that the more the rock was framed and detached from its surroundings, the more

important it became for the pilgrims’ visible and tactile experience.

This process culminated in the mid-twelfth century, when the Rock of Golgotha was

entirely enclosed within the Crusaders’ Church of the Holy Sepulchre.6 The shape of the

rock was concealed and fragmented between the upper Chapel of the Crucifixion and the

lower Chapel of Adam. In its new setting the rock was almost entirely hidden, except for

its most important parts, which were intentionally left exposed to the pilgrims’ sight and

touch: the hole where the true cross was said to have once stood, and the cleft believed to

have been torn in the rock at the time of the Crucifixion (fig. 2). A chapel underneath the

Chapel of the Crucifixion marked the site of Adam’s tomb.7 Stains of Christ’s blood were

shown to pilgrims in the hole and the clefts of the rock.8 In the course of the following

centuries, the ‘openings’ of the Rock of Golgotha became the focus of intense devotional

practices. Though we lack visual evidence of the altar of the Crucifixion at the Crusaders’

Chapel, pilgrims’ texts provide us with knowledge concerning the setting and appearance

4 Itinerarium Antonini Placentini, in: Peter Geyer et al. (ed.): Itineraria et alia geographica, CCSL

175 (1965) p. 129–153 (capital 19). English translation: John Wilkinson: Jerusalem Pilgrims before

the crusades, Jerusalem 1977, p. 79–89, here p. 83.

5 For the transfer of biblical traditions to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in general, and to the

Rock of Golgotha in particular, see: Bianca Kühnel: Jewish Symbolism of the Temple and the Tab-

ernacle and Christian Symbolism of the Holy Sepulchre and the Heavenly Tabernacle, in: Jewish

Art 19/20 (1993/1994), p. 147–168, here p. 150; Robert Ousterhout: The Temple, the Sepulchre, and

the Martyrion of the Savior, in: Gesta 29.1 (1990), p. 44–53.

6 Bernard Hamilton: The Impact of Crusader Jerusalem on Western Christendom, in: The Catholic

Historical Review 80.4 (1994), p. 699.

7 While the glass windows that frame the exposures of the rock are modern, its general setting and

concealment within the architecture is a crusaders’ innovation, which determined the setting and

appearance of the rock up to the present day.

8 For example, Denys Pringle (ed.): Pilgrimage to Jerusalem and the Holy Land, 1187–1291, Crusade

Texts in Translation, Burlington 2011, p. 230.

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

48 Yamit Rachman-Schrire

2 A closer view of the cleft of the Rock of Golgotha, Jerusalem, Church of the Holy

Sepulchre

of the rock. The German pilgrim Theoderic, arriving in Jerusalem sometime between

1169 and 1174, after the crusaders’ reconstruction of the Chapel of Golgotha, reports:

“The place where the Cross itself stood […] is mounted on a big step […] and the hole

shown is deep and almost wide enough to put one’s head into […] in it the pilgrims

press their head and forehead to show love and reverence for the crucified one. But on

the right Mount Calvary goes down steeply, and in the floor has a long, wide, and very

deep crack. It was cracked at the death of Christ.”9

Theoderic’s testimony suggests that the openings of the rock were accessible to the pil-

grims’ sight and touch. Later pilgrims’ accounts follow this line, and elaborate on the

devotees’ custom to insert their heads, hands and entire bodies into the clefts of the rock.

An anonymous English pilgrim whose account is dated to 1344–1345, notes: “The place

where stood erect the cross of Jesus is visible, into which people put their heads to the

shoulders.”10 This pilgrim further elaborates on the blood that Christ – whom he com-

9 John Wilkinson, Joyce Hill, and William F. Ryan (ed.): Jerusalem Pilgrimage, 1099–1185, London

1988, p. 274–314, here p. 285f. Theoderic: Libellus de locis sanctis, in: Robert B.C. Huygens (ed.):

Peregrinationes tres. CCCM 139 (1994), p. 142–197, here p. 155f.

10 Eugene Hoade (ed.): Western Pilgrims, Jerusalem 1952, p. 66. “Montem Calvarie, que rupis est

magna […] locus ubi crux Jhesu extitit erecta patens est, in quo ponunt homines usque ad humeros

capita sua […].” Anonymous Englishman: Itinerarium, in: Girolamo Golubovich (ed.): Biblioteca

Bio-Bibliografica della Terra Santa e dell’Oriente 4 (1923), p. 427–460, here p. 452.

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

Christ’s Side-Wound and Francis’ Stigmatization at La-Verna 49

pares to a pelican – shed on Adam’s skull.11 In medieval piety the pelican was perceived as

a symbol of Christ’s sacrifice and resurrection. For this reason a pelican was sometimes

integrated into visual images of the crucifixion, usually depicted on top of the cross, nour-

ishing her young.12 The pilgrim’s utilization of the figure of the pelican in the face of the

rock’s aperture is telling, for it provides a glimpse into the visual and textual allegories

stored in his mind before arriving in Jerusalem, and to the manner in which these were

projected upon the sacred place itself.

An exceptional testimony for the pilgrims’ devotional practices of the clefts of the

Rock of Golgotha appears in the account of Felix Fabri (~1441–1502), the Dominican

preacher from Ulm and a two-time pilgrim to the Holy Land.13 Facing the Rock of Gol-

gotha at the Chapel of the Crucifixion, Fabri reports of the somatic practices he and his

fellow-pilgrims applied at the rock:

“[E]ach one as best as he could crawled to the socket-hole of the cross, kissed the place

with exceeding great devotion, and placed his face, eyes, and mouth over the socket-

hole, from whence in very truth there breathes forth an exceeding sweet scent,

whereby men are visibly refreshed.” 14

He then continues to describe how they crawled into the cleft of the rock: “We went up to

this rent one after another, and kissed it, putting our heads into it and as much of our

bodies as we could.”15 Fabri’s description of the pilgrims’ veneration of the rock of Gol-

gotha, including their actual penetration deep into it, is remarkably elaborated; yet, other

pilgrims also relate to the somatic practices applied at the cleft of the rock. The German

pilgrim Heinrich von Zedlitz, visiting the Holy Land in 1493, explains that pilgrims could

enter their hands up to their elbows into the hole in the rock, and could fully lay their

11 Ibid.

12 According to medieval tradition, the pelican pierces its breast to feed its children with its own

blood. For this reason, a pelican sometimes accompanies artistic descriptions of the crucifixion as

a symbol for Christ’s sacrificial blood. See for example in the famous fresco of the Crucifixion in

the Oratorio of San Giovanni Battista in Urbino.

13 For Fabri’s Evagatorium and other pilgrimage writings: Kathryne Beebe: Pilgrim and preacher. The

audiences and observant spirituality of Friar Felix Fabri (1437/8–1502), Oxford 2014.

14 Aubrey Stewart (ed.): The Book of the Wanderings of Brother Felix Fabri (Circa 1480–1483 A. D.),

PPTS 8 (1897), p. 365. “Finita autem oratione unus post alium ad petram sanctam, quae promine-

bat supra fundamentum, accessit, et ad foramen crucis se quilibet juxta loci dispositionem traxit,

et locum ipsum eximia cum devotione deosculabatur et faciem, oculos, os quilibet super cruces

foramen posuit, de quo nimirum foramine dulcis admodum spirat odor sensibilis, qui perceptibi-

liter hominem recreat. Brachium, etiam manus in ipsum foramen misimus usque ad suum fun-

dum. Et cum his indulgentias pleneriae remissionis accepimus.” Konrad D. Hassler (ed.): Fratris

Felicis Fabri Evagatorium in Terrae Sanctae, Arabiae et Aegypti Peregrinationem, Stuttgart 1843,

vol. 2, p. 299.

15 Ibid.

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

50 Yamit Rachman-Schrire

bodies in the cleft.16 An anonymous French pilgrim arriving in Jerusalem in 1518, describes

how pilgrims touched the hole of the cross with their hands and arms “par dévotion”.17

While art historians and historians attempted to reconstruct the architecture and decora-

tive plan of the crusaders’ Chapel of Golgotha, only little attention has been given in these

studies to the role that the Rock of Golgotha had played in the formation of the sacred site

and in the pilgrims’ experience of the place. 18 In order to reconstruct what notions and

ideas shaped the pilgrims’ viewing of the Rock of Golgotha, we should turn our gaze back

to Europe, to the places from which the pilgrims journeyed to the Holy Land. Western

piety had been undergoing tremendous alterations in the twelfth century, with the emer-

gence of affective piety to Christ’s humanity and sufferings, and the desire to imitate

Christ literally.19 These trends should be the immediate context to analyze and interpret

pilgrims’ devotion to the cleft and the hole of the Rock of Golgotha. In what follows I map

the spatial and visual associations between the wounds of Christ and the Rock of Golgotha

as these are reconstructed in late medieval texts and visual images. I suggest that pilgrims

arriving in Jerusalem viewed the clefts of the Rock of Golgotha as an extension of the

wounded body of Christ. My interpretation is based on texts which encourage the devo-

tees to enter the body of ‘Christ-the-rock’ via his clefts, as well as on visual imagery relating

to the gaping wound of Christ in images of the arma Christi, and to St Francis’ stigmatiza-

tion on the clefts of the site of La-Verna which is characterized as the New Golgotha.

Into the clefts of Christ-the-rock

A firm association between the body of Christ and the Rock of Golgotha is to be found in

late medieval exegesis, via allegorical or metaphorical interpretations, which offer a paral-

lel between the wounds of Christ and the clefts of the rock. Such an association appears in

the interpretation of Bernard of Clairvaux (d. 1153) to the Song of Songs 2:14, where he

16 Die Jerusalemfahrt des Heinrich von Zedlitz (1493), in: Reinhold Röhricht (ed.): Zeitschrift des

deutschen Palästina-Vereines (1894), p. 99–114, p. 185–200, p. 277–301, here p. 278.

17 Voyage de Venise au Saint-Sépulcre, in: Jean-Luc Nardone (ed.): La représentation de Jérusalem et

de la Terre Sainte dans les récits des pèlerins européens au XVIe siècle, Paris 2007, p. 75.

18 Dorothea French suggested a cosmological interpretation of Golgotha as the centre of the earth

where sensus allegoricus and sensus literalis are fused. French is right in indicating the fusion of

these senses at the holy place. Yet, her cosmological explanation for the pilgrims’ aspiration of

entering the clefts of the rock is problematic: she merges different locations within the church (i.e.

Christ’s sepulchre, Golgotha) and does not take into account the existence of an actual site, at the

choir of the church, where the ‘centre of the earth’ was shown to pilgrims. Dorothea R. French:

Journeys to the Center of the Earth. Medieval and Renaissance Pilgrimages to Mount Calvary, in:

Barbara N. Sargent-Baur (ed.): Journeys toward God. Pilgrimage and Crusade, Kalamazoo 1992,

p. 45–81.

19 Richard Kieckhefer: Major Currents in Late Medieval Devotion, in: Jill Raitt, Bernard McGinn and

John Meyendorff (ed.): Christian Spirituality. High Middle Ages and Reformation, New York 1987,

p. 75–108.

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

Christ’s Side-Wound and Francis’ Stigmatization at La-Verna 51

encourages the devotees to enter into Christ-the-rock via the clefts of his body (“per

foramina corporis”).20 Bernard’s notion of the wounds of Christ as the clefts of the rock is

an elaboration of a well-established scriptural and patristic tradition that offered alle-

gorical connections between Christ and biblical stones and rocks, often formulated as

lapis est christus.21 The mystical aspiration of entering Christ’s body via his wounds / clefts

gained popularity in the late Middle Ages, as it is manifested in various literary genres,

including devotional manuals and works. For example, in the Orationes et meditationes de

vita Christi, attributed to the Cistercian Thomas a Kempis (1380–1471) and among the

most influential devotional compositions in late medieval Europe, the author advices his

readers:

“Enter then, enter boldly, O my soul, through the bowels of the mercy of Thy God as

He hangs upon the Cross; enter into the deep clefts of His Wounds, and take refuge

there from the serpent who everywhere, both openly and secretly, is laying snares for

thee. There lie still in safety, as a turtle-dove cooing in the wilderness, as a cushat lying

hid in the cleft of a mighty rock; spurn all earthly joys; meditate on the sacred Wounds

of Christ; and hope, relying on Them, to win those heavenly rewards which He Him-

self has in store for thee.”22

By evoking the body of Christ as he is hung on the cross, the author of the Orationes et

meditationes suggests a link between the notion of the dove that nests in the wounds of

Christ-the-rock, and the Rock of Golgotha. The same notion is also to be found in the

Ancrene Wisse, written in the mid fourteenth century, originally for three anchorite young

sisters, but later distributed to much wider audiences:23 “Name Jesus often, and invoke the

aid of his passion […]. Fly into his wounds; creep into them with thy thought, they are all

20 Bernard of Clairvaux: Supra Cantica, Sermo LXI.3, LXI.4. Song of Songs 2:14: “columba mea in

foraminibus petrae in caverna maceriae ostende mihi faciem tuam sonet vox tua” (English transla-

tion: Ann Matter: The Voice of My Beloved: The Song of Songs in Western Medieval Christianity,

Philadelphia 1990, p. 137–138: “O my dove, that art in the clefts of the rock, in the secret places of

the stairs, let me see thy countenance, let me hear thy voice.”).

21 Gerhard Ladner: The Symbolism of the Biblical Cornerstone in the Medieval West, in: Medieval

Studies 4 (1942), p. 43–60; Yamit Rachman-Schrire: Evagatorium in Terrae Sanctae. Stones Telling

the Story of Jerusalem, in: Annette Hoffmann and Gerhard Wolf (ed.): Jerusalem as Narrative

Space. Erzählraum Jerusalem, Leiden 2012, p. 353–366.

22 Michael Iosephus Pohl (ed.): Thomae Hemerken a Kempis. Opera Omnia. Orationes et Medita-

tiones de Vita Christi, vol. 4, Freiburg i. Br. 1895, p. 303f. English translation: William Duthoit

(ed.): Thomas a Kempis, Prayers and Meditations on the Life of Christ, London 1908, p. 182. In

another passage the author specifically relates to Christ as the Rock whom Longinus’ sword stroke:

“But the brawny soldier Longinus, when he opened Christ’s right side, struck the Rock with his

lance so fierce a blow, that thereout blood and water have never ceased to pour”, ibid., p. 181. Com-

pare p. 115 and p. 278.

23 For the popularity of the Text, which has been survived in 14 manuscripts in French, Latin and

English, see: Janet Grayson: Structure and Imagery in Ancrene Wisse, Hanover et al. 1974, p. 3–8.

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

52 Yamit Rachman-Schrire

open. He loved us much who permitted such cavities to be made in him, that we might

hide ourselves in them.”24

While the analogy between Christ’s wounds and the clefts of the rock is a conven-

tional rhetoric in devotional literature in this period, the author of the Ancrene Wisse

further elaborates this idea:

“‘Ingredere in petram, et abscondere in fossa humo;’ ‘Go into the rock,’ saith the

prophet, ‘and hide thee in the pit which is dug in the earth;’ that is, in the wounds of

our Lord’s flesh, which was as if dug into with the blunt nails, as he said long before

in the Psalter, ‘Foderunt manus meas et pedes meos;’ that is, they dug my feet and my

hands. He did not say, they pierced my feet and my hands, but dug. For, according to

this Latin, as our teachers say, the nails were so blunt that they digged his flesh, and

broke the bones rather than pierced them, to torment him the sorer.”25

Insisting that Christ’s wounds were dug in his body, in the same way that cavities are

formed in the rock, the author of the Ancrene Wisse intensifies the idea of Christ’s wounds

as the cavities of the rock. As Cate Gunn argues, this is “an example of how the spiritual-

ity of the Ancrene Wisse occupies a position on the cusp between traditional monastic

ideas and images, and their adaptation for late medieval popular devotion”.26

Christ’s wounds as a place for contemplation

The aspiration of entering Christ’s body via his wounds is closely connected to late medi-

eval visual iconography of the arma Christi with the isolated side-wound of Christ. In this

iconography, the side-wound is detached from the body of Christ, or replaces it, and

becomes in itself a devotional object.27 For example in a late fifteenth century German

woodcut, the isolated side-wound in the shape of a mandorla replaces the body of Christ

(fig. 3). The image of Veronica serves as the head of Christ, and the wounded hands and

feet attached to the left and to the right side of the body / wound serve to reconfigure the

whole body of Christ. The wound / body of Christ is painted in red and contains what

Caroline Walker Bynum calls “an abbreviated version of the arma Christi”, that is, a little

24 James Morton, (ed.): The Ancren Riwle: A Treatise on the Rules and Duties of Monastic Life, Lon-

don 1853, p. 293.

25 Ibid.

26 Cate Gunn: Ancrene Wisse. From Pastoral Literature to Vernacular Spirituality, Cardiff 2008,

p. 56.

27 David S. Areford: The Passion Measured: A Late-Medieval Diagram of the Body of Christ, in:

Alasdair A. MacDonald et al. (ed.): The Broken Body: Passion Devotion in Late-Medieval Culture,

Groningen 1998, p. 211–238.

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

Christ’s Side-Wound and Francis’ Stigmatization at La-Verna 53

3 Arma Christi with the wounds of Christ,

c. 1490, woodcut, 12 × 8.1 cm, Washington/

DC, National Gallery of Art

yellow cross, mocking titulus, and the heart with three nails.28 Two scrolls to the left and

to the right sides of the wound grant the believers with indulgences, and claim to specify

the real measurements of Christ’s side wound and height.29 Gerhard Wolf stresses the

interplay between fragmentation and reconfiguration in this image, pointing out that the

scrolls on both sides of the wound / body are like the skin removed to the side in order to

expose the wound; the wound invites the beholder to look into the body of Christ, where

the cross was fixed as a spinal bone crowned by the heart and the nails.30 The substitution

of the body of Christ for his wound is comparable to the substitution of the Rock of Gol-

gotha for its openings. David Areford highlighted the spatial dimension of the side-wound

in this image that offers an “effective devotional tool which allowed a highly corporeal and

spatial access to the body of Christ”.31 Here, the pictorial arrangement suggests a reversal

28 Caroline Walker Bynum: Violent Imagery in Late Medieval Piety, in: Bulletin of the German His-

torical Institute 30 (2001), p. 3–36, here p. 20.

29 The scroll to the right claims that the image is a life-size representation of the side wound, and the

scroll to the left claims that the little cross within the side wound measured forty times equals the

height of Christ in his humanity. Cf. Bynum 2001 (see n. 28).

30 Gerhard Wolf: Schleier und Spiegel. Traditionen des Christusbildes und die Bildkonzepte der

Renaissance, Munich 2002, p. 179–181.

31 Areford 1998 (see n. 27), p. 211. For interpretations of the space-like gapped wound as the vagina

and the womb, see: Caroline Walker Bynum: Fragmentation and Redemption. Essays on Gender

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

54 Yamit Rachman-Schrire

4 Arma Christi with the

wound of Christ,

Heures de Maréchal de

Boucicaut, early

fifteenth century,

Paris, MJAP –

MS 1311, fol. 242

relationship between ‘body’ and ‘site’ as the wound contains the cross. In another image,

a fifteenth century arma Christi from the Hours of the Maréchal de Boucicaut (fig. 4), the

side-wound of Christ is positioned beneath the cross. Its intense red colour, horizontal

and the Human Body in Medieval Religion, New York 1991, p. 182; Karma Lochrie: Mystical Acts,

Queer Tendencies, in: Karma Lochrie, Peggy McCracken, and James Alfred Schultz (ed.): Con-

structing Medieval Sexuality, Minneapolis 1997, p. 180–200, here p. 189f.; Sarah Alison Miller:

Virgins, Mothers, Monsters: Late-Medieval Readings of the Female Body Out of Bounds, unpub-

lished PhD diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2008, p. 238. For the visualization of

Christ’s side wound as a performative space, see: Vibeke Olson: Penetrating the Void. Picturing the

Wound in Christ’s Side as a Performative Space, in: Larissa Tracy and Kelly DeVries (ed.): Wounds

and Wound Repair in Medieval Culture, Leiden 2015, p. 314–339, here p. 316f.

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

Christ’s Side-Wound and Francis’ Stigmatization at La-Verna 55

position and relatively large size make this form at the foot of the cross especially promi-

nent in the whole composition. In this setting the wound seems projected upon the rocky

ground, while its location beneath the cross, seems to allude to the Rock of Golgotha – the

exact site of the crucifixion where the actual wounds of Christ were torn in his flesh.32

Christ’s wounds, Francis’ Stigmatization and La-Verna

as the “New Jerusalem”

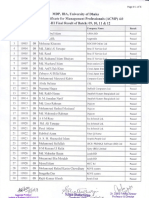

Spatial and visual associations between the wounds of Christ and the cracked Rock of

Golgotha are also found in fourteenth and fifteenth century visual images of the stigmata

of St Francis. According to Francis’ hagiographers, in 1224, two years before his death,

while Francis was in deep prayer on Mount La-Verna near Arezzo, he had a vision of a

seraph who descended from heaven. The apparition miraculously impressed the five

wounds of Christ into Francis’ flesh.33 By receiving the wounds of the Stigmata, Francis

was re-assured as the alter christus who has performed in his life the closest model of

Christ himself. In visual iconography of the stigmatization of St Francis, the clefts of

Mount La-Verna (also Alverna, della Vernia), the place where Francis is said to have

received the stigmata, are visually and formally associated with the clefts of the Rock of

Golgotha.34 This is evident, for example, in an enameled morse dated to the first quarter

of the fourteenth century (pl. 8): St Francis is situated in a rocky landscape across from a

small chapel, receiving the stigmata wounds on his hands, feet, and side. Gilded rays

descend from the limbs of the seraph, searing the flesh of Saint Francis, whose body, like

that of the heavenly seraph, is surrounded by an aura of light. The rocky setting of the

stigmatization is very prominent in this image: the rocks are cracked and show their

depths which are filled with red colour. Intensive red and brownish hues dominate the

whole image, the trees to the right of Francis, the seraph, Francis’ coat and the altar set in

front of him with its leg fixed in the rock’s caverns. The vivid red colour in the clefts of the

rocks portrays the whole mountain as a ‘bleeding’ landscape, openly exposing its ‘wounds’

full of blood. Such a description echoes narratives of the stigmata of St Francis that paral-

lel Mount La-Verna and the Rock of Golgotha, in the fourteenth century text Fioretti di

San Francesco, based on earlier oral and literary traditions. In the ‘second consideration

on the wounds of Francis’, the author writes:

32 Compare with Elina Gertsman who has recently discussed the translocation of Christ’s wounds

from his body, onto other spaces in a fifteenth century German woodcut printed in Ulm: Wander-

ing Wounds. The Urban Body in Imitatio Christi, in: Traey / De Vies 2015 (see n. 31), p. 340–366.

33 Francis’ Hagiography was written by Thomas of Celano before 1230 as the Vita prima and Vita

secunda. Between 1263 and 1266 St Bonaventure rewrote the works of Celano, and composed the

Legenda maior and the Legenda minor which became the official biography of Francis.

34 Bonaventure emphasized the mountain-like appearance of La-Verna, and that the seraph in the

Stigmatization was Christ attached to the cross, with six wings.

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

56 Yamit Rachman-Schrire

“[A]s St Francis was considering the formation of the mountain, and marvelling at the

great fissures and openings in the solid rock, it was revealed to him by God in prayer

that these strange caverns had been made miraculously at the hour of the Passion of

Christ, when, according to the Evangelist’s words, the rocks were rent; and this was by

the will of God, who manifested himself thus wonderfully upon Mount Alvernia,

because there the Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ was to be renewed in the soul of his

servant by love and compassion, and in his body by the impression of the sacred, holy

stigmata.”35

This text emphasizes the topographical and morphological similarities between the Rock

of Golgotha and the cleft rocks of La-Verna, the latter, was created in the rock at the time

of the Passion of Christ. Both text and image confirm the theme of Franciscus alter Chris-

tus, and by extension La-Verna alter Golgotha.36

To conclude, pilgrims’ arriving at the holy land carried in their minds an ensemble of

literal and visual images, which they have projected upon the sacred site itself. It is possible

to see how the cleft of the Rock of Golgotha, which has been emphasized in the architec-

ture of the Chapel of the Crucifixion, could have evoked in the believers the image of the

gaping wound of Christ or the clefts of La-Verna, where St Francis, the ultimate follower

of Christ, received the wounds of the Stigmata. As the pilgrims’ testimonies suggest, the

clefts of the rock turn into performative space which received its meaning from the

encounter with the devotees. From a formal point of view, the hole and the cleft stood for

the entire rock, constituting synecdochel relations with it. By entering the clefts of the

35 The Little Flowers of St Francis is an Italian adaptation of the early fourteenth century Latin

account, the actus Beati Francisci et sociorum Eius. “Ivi a pochi di, istandosi Santo Francesco allato

alla detta cella, e considerando la disposizione del Monte, e maraviglian dosi delle grandissime

fessure ed aperture di sassi grandissimi, si puose in orazione; e allora gli fu rivelato da Dio, che

quelle fessure cosi maravigliose erano istate fatte miracolosamente, nell’ora della Passione di

Cristo, quando, secondo che dice il Vangelista, le pietre si spezzarono. E questo volle Iddio, che

singularmente apparesse in su quell Monte della Vernia, perchè quivi si dovea rinnovare La Pas-

sione del nostro Signore Gesù Cristo nell’anima sua, per amore e compassione, e nel corpo suo per

impression delle sacre sante Istimate.” Adolfo Padovan, (ed.): I fioretti di san francesco e il cantico

del sole, Milan 1907, p. 179f. English translation: Of the Second Consideration of the Holy Stigmata,

in: The Little Flowers of St. Francis of Assisi (CCEL, public domain), http://www.ewtn.com/

library/MARY/flowers1.htm, (30.05.2018). For a discussion of the parallels between Golgotha and

another holy mountain, Montserrat, relating to the distinct features of cracked landscape, and in

the context of the development of the imitatio Christi, see Lily Arad: An Absent Presence: Jerusa-

lem in Montserrat, in: Miscellania Liturgica Catalana 20 (2012), p. 71–107.

36 Yamit Rachman-Schrire: The Stones of the Christian Holy Places of Jerusalem and Western Imag-

ination: Image, Place, Text (1099–1517), unpublished PhD diss., The Hebrew University of Jerusa-

lem, 2015, p. 66–68. Michele Bacci: Il Golgotha come Simulacro, in: Annette Hoffmann, Manuela

de Giorgi and Nicola Suthor (ed.): Bildkulturen im Dialog. Festschrift für Gerhard Wolf, Munich

2013, p. 111–122.

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

Christ’s Side-Wound and Francis’ Stigmatization at La-Verna 57

Rock of Golgotha, pilgrims could fulfill their aspiration of entering the body of Christ-

the-rock at the actual site in Jerusalem, where Christ’s wounds were torn in his flesh.

Whereas not all accounts suggest an explicit reference to the images pilgrims held in their

minds, Margery Kempe in her testimony explicitly refers to the image of the dove in the

clefts of the Rock while reflecting on the body of Christ: “his precious tender body, all rent

and torn with scourges, more full of wounds than a dove-cote ever was of holes”.37 The

sweet scent, which emanates from the hole in the rock, as Fabri recalls, is an attribution of

Christ’s body, and specifically of his wounds.38 The clefts of the Rock of Golgotha offered

the devotees the opportunity to unify with Christ in its historical and Eucharistic senses,

both incarnated in the blood stains within the clefts of the rock. Notably, pilgrims’ imag-

ination of the clefts of the rock as a place of refuge is also related to the biblical models of

Moses, who saw God in the cleft of the rock (Exod 33:22), and Thomas who entered his

fingers into the wounds of Christ, in order to recognize the Resurrection (John 20:27).39

Reconstructing the visuality and the history of reception of the Rock of Golgotha shows

that it functioned as a performative object, whose meaning was shaped and re-shaped via

the encounter with contemporaries and the devotional imagery they held in their minds

prior to their arrival in the Holy Land. Such an inquiry allows us a glimpse into the nature

of mediation and the agency of stones in late medieval cultures, and demonstrates the

central role the rock played in the pilgrims’ imagination and experience of the site of the

Crucifixion.

37 The Book of Margery Kempe, ed. Barry Windeatt, Harmondsworth 1985, p. 104f.

38 The sweet scent of Christ is already mentioned by Paulus, who said that the sacrifice of Christ was

a “fragrant aroma to God” (Eph. 5:2). For medieval “olfactory theology”, see Constance Classen,

The Colour of Angels: Cosmology, Gender and the Aesthetic Imagination (London: Routledge,

2002), p. 53–55; Graziano, Wounds of Love, p. 80–84. For Christ’s foreskin exuding the odour of

sanctity, see David L. Gollaher, Circumcision: A History of the World’s Most Controversial Sur-

gery, New York 2000, p. 37.

39 Both figurations appear in Bernard’s sermon in comparison to the clefts of Christ body and were

wide spread in visual iconography.

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

Authenticated | yamit.rs@gmail.com author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 7:07 AM

Farbtafeln 101

7 Buonamico Buffalmacco: Thebaid, 1336–1342, fresco, Pisa, Camposanto

8 Saint Francis of Assisi receiving

the Stigmata, morse, Tuscany,

1300–1325, copper gilt, with

champlevé enamel, diam.

10.8 cm, New York, The

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Authenticated | davik@sas.upenn.edu author's copy

Download Date | 12/21/18 4:47 AM

Вам также может понравиться

- Ghost-haunted land: Contemporary art and post-Troubles Northern IrelandОт EverandGhost-haunted land: Contemporary art and post-Troubles Northern IrelandОценок пока нет

- Judas Repents?Документ4 страницыJudas Repents?Grace Church ModestoОценок пока нет

- Carnal Knowledge of God: Embodied Love and the Movement for JusticeОт EverandCarnal Knowledge of God: Embodied Love and the Movement for JusticeОценок пока нет

- Key Findings: Supporting LGBT LivesДокумент8 страницKey Findings: Supporting LGBT LivesBrian BreathnachОценок пока нет

- Mary Magdalene and the Drama of Saints: Theater, Gender, and Religion in Late Medieval EnglandОт EverandMary Magdalene and the Drama of Saints: Theater, Gender, and Religion in Late Medieval EnglandОценок пока нет

- Elements of The Story/Fiction: Death NoteДокумент21 страницаElements of The Story/Fiction: Death NoteIsmael TarrasОценок пока нет

- Forgiving Our FathersДокумент1 страницаForgiving Our FathersVirginia Warfield100% (2)

- Piers Plowman and the Poetics of Enigma: Riddles, Rhetoric, and TheologyОт EverandPiers Plowman and the Poetics of Enigma: Riddles, Rhetoric, and TheologyОценок пока нет

- Blood and Body Women's Religious Practices in Late Medieval EuropeДокумент110 страницBlood and Body Women's Religious Practices in Late Medieval EuropeKriKee100% (1)

- Affections of the Mind: The Politics of Sacramental Marriage in Late Medieval English LiteratureОт EverandAffections of the Mind: The Politics of Sacramental Marriage in Late Medieval English LiteratureОценок пока нет

- Indonesia Hiduism Batara GuruДокумент5 страницIndonesia Hiduism Batara GuruDarcyTyrionОценок пока нет

- Gipsy Life: Being an account of our Gipsies and their children, with suggestions for their improvementОт EverandGipsy Life: Being an account of our Gipsies and their children, with suggestions for their improvementОценок пока нет

- Considering Female Agency Hildegard of Bingen and Francesca WoodmanДокумент10 страницConsidering Female Agency Hildegard of Bingen and Francesca WoodmanMaksim PlebejacОценок пока нет

- DancingДокумент22 страницыDancingRafael MediavillaОценок пока нет

- Adolph Von Menzel - Historical and Literary Studies Pagan Jewish and Christian Cd6 Id471145024 Size80Документ19 страницAdolph Von Menzel - Historical and Literary Studies Pagan Jewish and Christian Cd6 Id471145024 Size80HotSpireОценок пока нет

- Lucrezia Marinelli and Woman's Identity in Late Italian RenaissanceДокумент35 страницLucrezia Marinelli and Woman's Identity in Late Italian RenaissanceVictoria MarinelliОценок пока нет

- Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle AgesОт EverandJesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle AgesРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (8)

- Papua New Guinean LiteratureДокумент25 страницPapua New Guinean LiteratureAtom D'Arcangelo100% (1)

- The Garb of Being: Embodiment and the Pursuit of Holiness in Late Ancient ChristianityОт EverandThe Garb of Being: Embodiment and the Pursuit of Holiness in Late Ancient ChristianityОценок пока нет

- Blood of ChrtistДокумент317 страницBlood of ChrtistAndrijana Bogdanovic100% (1)

- Hildegard of Bingen: Commentary On The Johannine PrologueДокумент18 страницHildegard of Bingen: Commentary On The Johannine ProloguePedro100% (1)

- dr-thesis-2017-Synnøve-Midtbø-Myking - Uib - NoДокумент364 страницыdr-thesis-2017-Synnøve-Midtbø-Myking - Uib - NoQuentinОценок пока нет

- B-Mandeville's Medieval AudiencesДокумент4 страницыB-Mandeville's Medieval AudiencesjlurbinaОценок пока нет

- TURNER VICTOR (1974) Dramas, Fields, and MetaphorsДокумент1 страницаTURNER VICTOR (1974) Dramas, Fields, and MetaphorsMartin De Mauro RucovskyОценок пока нет

- Martin Buber Christian Implications PDFДокумент26 страницMartin Buber Christian Implications PDFjohnОценок пока нет

- 9781909646728Документ384 страницы9781909646728Šime DemoОценок пока нет

- Hybrid Monsters in The Classical World PDFДокумент130 страницHybrid Monsters in The Classical World PDFJeffrey RobbinsОценок пока нет

- Rudolf Otto and The Concept of The NuminousДокумент24 страницыRudolf Otto and The Concept of The NuminousRanjitDevGoswamiОценок пока нет

- The Hellweg To HollandДокумент41 страницаThe Hellweg To HollandRichter, Joannes100% (1)

- Michael Crichton, Ibn Fadlan, Fantasy Cinema: Beowulf at The Movies - Hugh MagennisДокумент5 страницMichael Crichton, Ibn Fadlan, Fantasy Cinema: Beowulf at The Movies - Hugh MagennisSamir Al-HamedОценок пока нет

- The Sweetness of Nothingness - Poverty PDFДокумент10 страницThe Sweetness of Nothingness - Poverty PDFKevin HughesОценок пока нет

- Contemporary DisaffectionДокумент27 страницContemporary DisaffectionAbdiel Arturo Vera0% (1)

- Sacred Psychiatry in Ancient GreeceДокумент9 страницSacred Psychiatry in Ancient GreeceRade GrbicОценок пока нет

- Sansi, Art and Anthropology After Relations PDFДокумент15 страницSansi, Art and Anthropology After Relations PDFLorenzo BartalesiОценок пока нет

- Face To Face - Portraits of The Divine in Early ChristianityДокумент254 страницыFace To Face - Portraits of The Divine in Early Christianityrrol2Оценок пока нет

- Representations of Femininity in Seventeenth Century Conduct Manuals For GentlemenДокумент12 страницRepresentations of Femininity in Seventeenth Century Conduct Manuals For GentlemenNoelia MirindaperonОценок пока нет

- CA - 215 Silbury HillДокумент9 страницCA - 215 Silbury HillLisa W WestcottОценок пока нет

- Why Homer Matters,' by Adam Nicholson - The Washington Post PDFДокумент5 страницWhy Homer Matters,' by Adam Nicholson - The Washington Post PDFΠΑΝΑΓΙΩΤΗΣ ΛΕΜΠΕΣΗΣОценок пока нет

- McCutcheon - The Category of 'Religion' in Recent PublicationsДокумент27 страницMcCutcheon - The Category of 'Religion' in Recent Publicationscsy7aaОценок пока нет

- Madness in Renaissance Art RGДокумент14 страницMadness in Renaissance Art RGMirjana Monet JugovicОценок пока нет

- Malinowski RevisitedДокумент28 страницMalinowski RevisitedMel G. MerazОценок пока нет

- Botkin Pome PDFДокумент17 страницBotkin Pome PDFDmitry GaltsinОценок пока нет

- Frame, Flow and ReflectionДокумент35 страницFrame, Flow and ReflectionLorenzo VigevaniОценок пока нет

- Advaita & GnosticismДокумент36 страницAdvaita & Gnosticismsreejithg1979Оценок пока нет

- A Satirical Elegy On The Death of A Late Famous GeneralДокумент1 страницаA Satirical Elegy On The Death of A Late Famous Generalokaly0Оценок пока нет

- The Books of William EversonДокумент18 страницThe Books of William EversonFallingIcarusОценок пока нет

- Agamben Philosophical ArchaeologyДокумент21 страницаAgamben Philosophical ArchaeologyAlexei PenzinОценок пока нет

- Between Love and Revelation Rumi and TheДокумент9 страницBetween Love and Revelation Rumi and TheBehroozОценок пока нет

- The Seventh ST Andrew's Patristic SymposiumДокумент20 страницThe Seventh ST Andrew's Patristic SymposiumDoru Costache100% (2)

- Review SEAFORD Reciprocity & RitualДокумент7 страницReview SEAFORD Reciprocity & Ritualmegasthenis1Оценок пока нет

- Notes From A Conversation With Michael TaussigДокумент8 страницNotes From A Conversation With Michael TaussigMule RomunescuОценок пока нет

- Reflections On Abjection, Anorexia, and Medieval Women MysticsДокумент22 страницыReflections On Abjection, Anorexia, and Medieval Women MysticsKayra ÖzОценок пока нет

- Stephen Greenblatt - How St. Augustine Invented SexДокумент16 страницStephen Greenblatt - How St. Augustine Invented SexFabián BarbaОценок пока нет

- TarantismДокумент22 страницыTarantismAhmed FayezОценок пока нет

- City DionysiaДокумент8 страницCity DionysiaShona171991Оценок пока нет

- The Ommegang of Brussels Monument of HisДокумент11 страницThe Ommegang of Brussels Monument of Hisyahya333Оценок пока нет

- L HABLOT The Van Limburg Brothers HeraldДокумент27 страницL HABLOT The Van Limburg Brothers Heraldyahya333Оценок пока нет

- Osiris, Isis, Horus Christianity and Islam WilkinstanleyДокумент16 страницOsiris, Isis, Horus Christianity and Islam Wilkinstanleyyahya333Оценок пока нет

- Internal Liturgy: The Transmission of The Jesus Prayer in The ANDДокумент35 страницInternal Liturgy: The Transmission of The Jesus Prayer in The ANDyahya333Оценок пока нет

- Escaping The Jaws of Death Some VisualДокумент21 страницаEscaping The Jaws of Death Some Visualyahya333Оценок пока нет

- Performing Salvation in Dante's CommediaДокумент34 страницыPerforming Salvation in Dante's Commediayahya333Оценок пока нет

- Hieronymus Bosch: The Oeuvre ofДокумент19 страницHieronymus Bosch: The Oeuvre ofyahya333Оценок пока нет

- On The Matter of Language The Creation oДокумент15 страницOn The Matter of Language The Creation oyahya333Оценок пока нет

- Astronomy and Mythology:: Reconstructing What 2012 Meant To The Ancient MayaДокумент21 страницаAstronomy and Mythology:: Reconstructing What 2012 Meant To The Ancient Mayayahya333Оценок пока нет

- Liber Divinorum OperumДокумент242 страницыLiber Divinorum Operumyahya333Оценок пока нет

- Departed Souls? Tripartition at The Close of Plato's RepublicДокумент33 страницыDeparted Souls? Tripartition at The Close of Plato's Republicyahya333Оценок пока нет

- Ars Devotionis Reinventing The Icon in EДокумент25 страницArs Devotionis Reinventing The Icon in Eyahya333Оценок пока нет

- Becoming All Light All Face All Eye CentДокумент85 страницBecoming All Light All Face All Eye CentLaimis MotuzaОценок пока нет

- A Sound Theology The Vital Position of SДокумент171 страницаA Sound Theology The Vital Position of Syahya333Оценок пока нет

- Between Utopia and Dystopia Erasmus ThomДокумент265 страницBetween Utopia and Dystopia Erasmus Thomyahya333Оценок пока нет

- Hildegard of Bingen An Explanation of THДокумент16 страницHildegard of Bingen An Explanation of THyahya333Оценок пока нет

- John Lydgate and The Dance of DeatДокумент38 страницJohn Lydgate and The Dance of Deatyahya333Оценок пока нет

- Skips of Fool TraditionДокумент10 страницSkips of Fool TraditionnaokiyokoОценок пока нет

- In The Age of Giorgione Exhibition Catal PDFДокумент84 страницыIn The Age of Giorgione Exhibition Catal PDFraulОценок пока нет

- Mirrors of Fools TextДокумент10 страницMirrors of Fools Textyahya333Оценок пока нет

- Physics and Optics in Dante's Divine ComedyДокумент8 страницPhysics and Optics in Dante's Divine Comedyyahya333Оценок пока нет

- A. Dürer or H. SchaufeleinДокумент13 страницA. Dürer or H. SchaufeleinZsófia AlbrechtОценок пока нет

- Written in The Stars: Dante's Language of The DivineДокумент7 страницWritten in The Stars: Dante's Language of The Divineyahya333Оценок пока нет

- The Birth of Ruins in Quattrocento AdoraДокумент31 страницаThe Birth of Ruins in Quattrocento Adorayahya333Оценок пока нет

- (E) Leonardo's Last Supper and The Three LayersДокумент8 страниц(E) Leonardo's Last Supper and The Three Layerspmo_researchОценок пока нет

- Sufism and Christian Mysticism in SpainДокумент14 страницSufism and Christian Mysticism in Spainyahya3330% (2)

- Chivalry and Knighthood: A OverviewДокумент13 страницChivalry and Knighthood: A Overviewyahya333Оценок пока нет

- Eng The Dynamic Concept of Sandro BottiДокумент4 страницыEng The Dynamic Concept of Sandro Bottiyahya333Оценок пока нет

- (E) Leonardo's Last Supper and The Three LayersДокумент8 страниц(E) Leonardo's Last Supper and The Three Layerspmo_researchОценок пока нет

- Piero Della Francescas Montefeltro AltarДокумент7 страницPiero Della Francescas Montefeltro Altaryahya333Оценок пока нет

- LM and CatastropheДокумент19 страницLM and CatastropheCharlie KeelingОценок пока нет

- Anna Riva - Devotion To The SaintsДокумент111 страницAnna Riva - Devotion To The SaintsAradialevanah86% (7)

- Minimalist Korean Aesthetic Pitch Deck by SlidesgoДокумент20 страницMinimalist Korean Aesthetic Pitch Deck by SlidesgoShreeya SharmaОценок пока нет

- Little JohnnyДокумент7 страницLittle JohnnysumitcooltoadОценок пока нет

- Script Drama NativityДокумент4 страницыScript Drama NativityAnnabelle BuyucanОценок пока нет

- Bruce Russell - The Problem of Evil: Too Much SufferingДокумент7 страницBruce Russell - The Problem of Evil: Too Much SufferingFОценок пока нет

- Four QuartetsДокумент5 страницFour QuartetsOnosa IulianaОценок пока нет

- Ahmed 2011 Review - Objects of TranslationДокумент5 страницAhmed 2011 Review - Objects of Translationav2422Оценок пока нет

- LiturgyДокумент4 страницыLiturgyEvan JordanОценок пока нет

- Jisscor Union v. TorresДокумент2 страницыJisscor Union v. TorresAngelo TiglaoОценок пока нет

- 30.3 Sabbasava S m2 Piya TanДокумент26 страниц30.3 Sabbasava S m2 Piya TanpancakhandaОценок пока нет

- Islamic Way of LifeДокумент36 страницIslamic Way of Lifeobl97100% (2)

- Origins and Development: Tamil Nadu Agamudayar Kallar Maravar South IndianДокумент4 страницыOrigins and Development: Tamil Nadu Agamudayar Kallar Maravar South IndianBell BottleОценок пока нет

- God in Dvaita VedantaДокумент16 страницGod in Dvaita VedantaSrikanth Shenoy100% (1)

- Penjasorkes 11 A8Документ70 страницPenjasorkes 11 A8MAK NYONG SENG channelОценок пока нет

- Apush Reform Theme PowerpointДокумент10 страницApush Reform Theme PowerpointTeja GuttiОценок пока нет

- History of Medicine DaysДокумент407 страницHistory of Medicine Dayssujithsnair100% (10)

- Alan Wolfelt Class SummaryДокумент2 страницыAlan Wolfelt Class SummaryaawulffОценок пока нет

- Issue of Kissing ThumbsДокумент25 страницIssue of Kissing ThumbsThe OKARVI'SОценок пока нет

- Beware of Ignorance It Is Not Excuse in Big Shirk and Clear KufrДокумент443 страницыBeware of Ignorance It Is Not Excuse in Big Shirk and Clear KufrNasirulTawhid100% (3)

- Loving Rasoolullah - QADI IYADДокумент50 страницLoving Rasoolullah - QADI IYADarsewruttan7365Оценок пока нет

- Daftar Anggota Komunitas MGMP SMK Teknik Otomotif Teknik Kendaraan Ringan TKRДокумент18 страницDaftar Anggota Komunitas MGMP SMK Teknik Otomotif Teknik Kendaraan Ringan TKRWahyono YonoОценок пока нет

- Troma NotesДокумент17 страницTroma NotesJirka Luboš Převorovský88% (8)

- Riordan, Rick - The Kane Chronicles Survival Guide (Disney Book Group)Документ145 страницRiordan, Rick - The Kane Chronicles Survival Guide (Disney Book Group)HalJ33% (3)

- Singha Rashi MantraДокумент1 страницаSingha Rashi MantraVishnu TamrakarОценок пока нет

- No. Module Learning Outcomes Essential Topics Essential Skills Essential Attitudes Online Strategies Online Assessment E-Learning MaterialДокумент10 страницNo. Module Learning Outcomes Essential Topics Essential Skills Essential Attitudes Online Strategies Online Assessment E-Learning MaterialAlaissa Jazzy C. TimosanОценок пока нет

- GROUP 1 Philosophy and EthicsДокумент7 страницGROUP 1 Philosophy and EthicsBin BaduaОценок пока нет

- Hyde QuotesДокумент1 страницаHyde QuotesSuleman WarsiОценок пока нет

- ACMP4.0 Phase-III ResultДокумент6 страницACMP4.0 Phase-III ResultasmreazОценок пока нет

- Short Story 8Документ57 страницShort Story 8tgun25Оценок пока нет