Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Paper Metodos Ergonomicos

Загружено:

salud laboral tocancipaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Paper Metodos Ergonomicos

Загружено:

salud laboral tocancipaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Finnish Institute of Occupational Health

Danish National Research Centre for the Working Environment

Norwegian National Institute of Occupational Health

Systematic evaluation of observational methods assessing biomechanical exposures at work

Author(s): Esa-Pekka Takala, Irmeli Pehkonen, Mikael Forsman, Gert-Åke Hansson, Svend Erik

Mathiassen, W Patrick Neumann, Gisela Sjøgaard, Kaj Bo Veiersted, Rolf H Westgaard and

Jørgen Winkel

Source: Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, Vol. 36, No. 1 (January 2010),

pp. 3-24

Published by: the Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, the Finnish Institute of

Occupational Health, the Danish National Research Centre for the Working Environment, and the

Norwegian National Institute of Occupational Health

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40967825 .

Accessed: 12/06/2014 15:38

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Danish

National Research Centre for the Working Environment, Norwegian National Institute of Occupational Health

are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Scandinavian Journal of Work,

Environment &Health.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Review

Scand J WorkEnvironHealth201 0,36(1):3-24

evaluation

Systematic methods

ofobservational assessingbiomechanical

atwork

exposures

Takala,

byEsa-Pekka PhD,1Irmeli MSc,1Mikael

Pehkonen, Forsman,

PhD,2Gert-Âke

Hansson,

PhD,3

SvendErik

Mathlassen, W

PhD,4 Patrick

Neumann,

PhD,5Gisela PhD,6

Sjßgaard, KajBoVeiersted,

PhD,7

RolfH Westgaard,

PhD,8 PhD9

Winkel,

Jörgen

TakalaE-P,Pehkonen

I, Forsman

M,Hansson G-Â,Mathiassen

SE, Neumann G,Veiersted

WP,Sjogaard KB,

WestgaardRH,Winkel

J.Systematic

evaluation

ofobservational

methods biomechanical

assessing at

exposures

work.

ScandJWork Environ

Health.

2010;36(1):3-24.

Objectives Thissystematic reviewaimedtoidentify publishedobservational

methodsassessingbiomechanical

inoccupational

exposures andevaluatethemwithreference

settings totheneedsofdifferent users.

Methods Wesearched scientific

databasesandtheinternetformaterialfrom1965toSeptember 2008.Methods

wereincludediftheywereprimarily basedon thesystematic observationofwork,theobservation was

target

thehumanbody,andthemethod intheliterature.

was clearlydescribed A systematic

evaluation procedurewas

developedto assessconcurrentandpredictive validity, andaspectsrelatedto utility.

repeatability, Atleasttwo

evaluators

independently carriedoutthisevaluation.

Results We identified 30 eligibleobservationalmethods.Of these,19 hadbeencompared withsomeother

method(s),varyingfromexpert evaluation todataobtained

from videorecordingsorthrough theuseoftechnical

instruments. theobservations

Generally, showedmoderate-to-goodagreement withthecorresponding assessments

madefrom videorecordings;agreement wasthebestforlarge-scalebodypostures andworkactions.Posturesof

wristandhandas wellas trunk rotation

seemedtobe moredifficulttoobservecorrectly.Intra-andinter-observer

werereported

repeatability for7 and17methods, andwerejudgedmostly

respectively, tobe moderate orgood.

Conclusions Withtraining, observers can reachconsistent

results

on clearlyvisiblebodypostures andwork

activities.

Manyobservational toolsexist,butnoneevaluated

inthisstudyappearedtobegenerally When

superior.

a method,

selecting usersshoulddefine theirneedsandassesshowresults willinfluencedecision-making.

Keyterms posture;

review;riskassessment;

workload.

Observational methods are probably the most often methodsand diversityin user needs, the selectionof an

used approach to evaluate physical workload in order appropriatetool can be challenging.

to identifyhazardsat work,monitortheeffectsof ergo- The selectionof a methodshould be based on (i) the

nomie changes, and conduct researchon these issues. objectives of its use, (ii) the characteristicsof thework

The numberof available methodsis large,butno single to be assessed, (iii) the individual(s) who will use the

one is suitable forall purposes - different

approaches method,and (iv) the resourcesavailable forcollecting

are needed for differentgoals. Due to differencesin and analyzing data. In epidemiological research, the

* FinnishInstitute

ofOccupational Finland.

Health,Helsinki,

2 KarolinskaInstitutet,

Stockholm,Sweden.

3 andEnvironmental Medicine,LundUniversity,

Occupational Lund,Sweden.

4 CentreforMusculoskeletalResearch, ofGavie,Sweden.

University

5 Canada.

Toronto,

Ryerson University,

6 ofSouthern

University Denmark,Odense,Denmark.

7 NationalInstitute

ofOccupational Health,Oslo,Norway.

° ofScienceandTechnology,

Norwegian University Trondheim, Norway.

UniversityofGothenburg,Gothenburg,SwedenandtheNationalResearchCentrefortheWorking

Environment, Denmark.

Copenhagen,

Correspondenceto: Dr E-P Takala,FinnishInstitute

of OccupationalHealth,Topeliuksenkatu

41, FI-00250 Helsinki,Finland.[E-mail:

esa-pekka.takala@ttl.fi]

Scand J WorkEnvironHealth 2010, vol 36, no 1 3

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Systematicevaluationofobservationalmethods

appropriate methods forstudying healthhazardsusually to identify sourcesvia theinternet. The searcheswere

differfrom thosemoresuitablefortheassessment ofthe conductedcoveringmaterialfrom1965 to September

needsforchangeat a singleworkplace, theevaluation 2008.

of theeffects of specificergonomie improvements, or Thesearchesweremadeusingseveralcombinations

thestudyoftheusability ofhandtools.Officialregula- of thefollowingsearchtermsrelatedto observational

tionsmaymakeexplicitdemandson theassessment, methods(using"OR"): observation, workload,lining,

forinstancein safetyinspections, or whenevaluating manualmaterial handling, riskassessment, taskanalysis,

theworkload inordertomakecompensability decisions posture,ergonomie, and occupational exposure.These

forinjuredworkers. terms werecombined (using"AND") with terms related

Potentialusersrarelyknowaboutmorethana very to themusculoskeletal system(using"OR"): musculo-

limitedselectionofmethods. Thereareseveralreasons skeletal,back,neck,extremities (eg, [observation OR

forthisknowledge gap. The reports describing methods workload] AND [back OR neck]). A search strategy

maybe in a languagethatis unfamiliar to theuser,or using only thesetermswas ineffective in identify-

theymayhavebeenpublished inunknown media.Meth- ing severalknownmethodsand,therefore, additional

ods mayhavebeendevelopedforspecificoccupations searcheswereperformed withthenamesoftheidenti-

onlyand,consequently, notbe suitableforthesetting fiedmethodsandusingtheoptionof "relatedarticles"

thattheuser needs to address. ofthekeyreferences. The reference listsofkeypapers

In orderforobservational data to provide a sound were also scanned to identify additional references.

basisfordecision-making, theassessment should be valid We screened the articles by titleand abstractfirst.

forthetargetedpurpose andtheresult should be reproduc- About 580 potential references were identified, includ-

ible.Anidealwaytoassessvalidity is tocompare results ing original scientific reports,reviews, and internet

witha "goldstandard". Thereis, however, no general sources.Full textsof thesereferences werecollatedin

"goldstandard" forassessingbiomechanical exposures, electronic format for further evaluation. The inclusion

eventhoughpostures can be accurately measuredwith criteria were as follows: (i) systematicobservation

directtechnicalmeasurements. Another aspectofvalid- of workshould be the principalexposureassessment

-

ity theabilityofthemethod to predict -

risks can be tool; (ii) themethod should be describedin a manner

studied byanalyzing theassociations between exposures allowingtheprocedure to be reproduced; and (iii) the

obtainedby themethodand theoutcomesof interest, observationtargetshould be the human locomotor

suchas musculoskeletal disorders(MSD). Assessment of system(eg, back/trunk, or

neck, extremities). Many

shouldcoverbothintra-

reproducibility andinter-observer originalarticlesdescribing a methodused onlyin one

(1,2) and,inthecaseofoff-line

repeatability observation specificstudywerediscardedbecausethetoolwas too

usingvideorecordings, thepossibleerrors andvariances inadequately described tobe reproduced andevaluated.

associatedwiththefilming procedure itself. Onlymethods thatwerepublically availableinscientific

Severalaspectsofobservational methods forassess- or otherreportsor commontextbooks wereincluded;

ingphysical workload havebeenreviewed earlier(3-8). thisexcludedcommercial productslackinga detailed

However, wecouldnotfindanup-to-date systematic and publicdescription. Wealso excludedmethods thatwere

criticalcomparison ofmethods devotedtoguiding users notdevelopedforvisualobservations in occupational

inselecting appropriate toolsfordifferent purposes. fieldsettings, suchas thosebasedentirely on themea-

Thus,theaimsofthisprojectweresystematically to surements ofposturalanglesfromvideorecordings.

identify published observational methodsforassessing

physicalworkload(biomechanicalexposures)and to Developing theframework forevaluation

evaluatecriticallythesemethods from theperspective of

differentusers,suchas researchers, occupational health Thereis no generallyacceptedprocedureto evaluate

andsafety personnel, safetyinspectors, ergonomists, and methodsfortheassessmentof workloadeventhough

work-system designers. severalpreviousreviewshave addressedthis issue

(3-9). In meetings to discussourreview,we developed

thestructure and contents of theevaluationprocedure

in an iterative manner.The procedureincludeditems

Methods describing thebasic featuresof themethods,as well

as assessmentsof theirvalidityand repeatability and

Searchandselection ofreference literature practicalissuesfor the users.

Validity assessment includedconcurrent validity (ie,

Literature searcheswereconductedin the following how well does the method correspond withmorevalid

electronic databases:PubMed,Embase,CISDOC, and methods?)and predictive validity(ie, how well have

ScienceDirect.We used Google and Google Scholar riskestimates generated bythemethodbeenshownto

4 Scand J WorkEnvironHealth2010, vol 36, no 1

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Takala et al

be associatedwithMSD?) (1,2). In addition, we evalu- Results

atedtheintra- andinter-observer repeatability.We also

assessedfacevalidity(ie, does themethodappearto A totalof30 eligibleobservational methods wereiden-

measurewhatitis intended tomeasure?)tohelppoten- tified.These 30 methodswere,altogether, described

tialusers,especiallyin cases whereno formalstudies and referenced in 285 documents, rangingfrom1-50

on validity havebeenperformed. references fora particularmethod. Additionalmethods

Foreachindividual reportdescribing thevalidity ofa referred to in 70 paperswereexcluded,mainlydue to

method, we evaluated thefollowing questions relatedto insufficient information on theparticular method.In

concurrent validity: (i) "Is thereference method validfor the followingdescription, methodsare classifiedin

comparison?" (ii) "Whatisthequality ofthecomparison?" threegroupsaccordingto whether themainfocuswas

and(iii)"Areresults generated bythemethod valid?"The toassess(i) generalworkload, (ii) upper-limbactivities,

ratingwas done on a 4-step scale from

(ranging "perfect/ or(iii) manualmaterial handling.

almostperfect" to"majorerror/mistake") withcomments The methodsare presented in chronological order

our

justifying rating. We evaluatedthe predictive of

validity of appearancein the literature, since newermethods

a method incross-sectional andlongitudinal trials,ifavail- generallysharesome featureswitholderones. Table

able,withfouroptions ("yes";"no";"conflicting results"; 1 summarizes thebasic characteristicsof themethods,

"cannot be estimated from documents"). table2 showstheevaluationofvalidityandrepeatabil-

In assessingtherepeatability of each method,we ity,andtable3 describesouropinionsrelatedto practi-

considered theresultsandtheirinterpretation - as given cal issuesfortheuser(s)of themethod.A descriptive

by the authors of the report- and rated the methods overviewof findings foreach tool is providedbelow.

on thefollowing scale: "probablyreliable";"potential Detailedinformation oftheevaluatedmethods withfull

error";"obviouserror";"cannotbe estimated". references canbe foundina websiteassociatedwiththe

Finally,on thebasis of all available information present project(10).

on concurrent validityandrepeatability, we ratedeach

method overallas "good","moderate", or"low"relative

totheseperformance

Methods

toassessgeneral

workload

aspects.

Weevaluated yâcevalidity withthefollowing Ovakoworking

ques- postureassessment system (OWAS). OWAS

tions:(i) "Is thecontent of themethodsuchthata rel-

was developedin a steelindustry companyto describe

evantassessment can be expected?"(ii) "Do theitems

workloads during theoverhauling ofironsmelting ovens

tobe observedhavea soundbasis?"(iii) "Is theopera- (11). Aspects to be observed includetheweightof the

tionalizationoftheitemstobe observed sound?"(iv) "Is

loadhandled(threecategories) andpostures oftheback

theprocessofdatacollectionandanalysissound?"(v) (fourpostures),arms(threepostures), andlowerextremi-

"Can theoutputhelpin decision-making?" In addition,

ties(sevenpostures), resulting in252 possiblecombina-

we evaluated thetool'sstrengths andlimitations, andthe

tions,whichhavebeenclassified tofouractioncategories

user

potential groups thereof. indicatinga needforergonomie change.Theobservations

weremadeas "snapshots" andsampling hasusuallybeen

carriedoutusingfixed-time intervals. OWAS ratings of

Evaluation

postureshavebeenwellassociated withperceived loading

Tworesearchers fromourgroupreadtheselectedpubli- anddiscomfort (12, 13).Fortimespentinbentpostures,

cationsandindependently completed thebasicdescrip- agreement between OWASanddirecttechnical measure-

tionanddocumentation ofall themethods intheevalua- mentshas beenratherlow (14), whichmaypartlybe

tionform. Afterthat,theydiscussedanydifferences and explainedbydifferences in sampling strategiesbetween

reacheda consensuson thewritten documentation. themethods. Inanevaluation oflifting situations,OWAS

Based on thisdocumentation and theoriginalarti- resultswereclearlydifferent fromthoseobtained bythe

cles, each methodwas evaluatedin termsof validity, NIOSH lifting equation(see pi 3- 14), probablydue to

and practicalissuesindependently

repeatability, by at thedifferentbasicapproaches ofthesetwomethods (15).

leasttwoevaluators blindedto eachother.The original Associations betweenOWASratings andtheoccurrence

tworesearchers evaluatedall identifiedmethods;a third of backdisorders havebeenreported in cross-sectional

member ofourgroupevaluated14 additional methods. studies(16). Themethod has showngoodintra- (17, 18)

Discrepancies wereresolvedbydiscussionamongst the andinter-observer repeatability (11, 17, 19,20).

evaluatorsinordertoestablish consensus.Ifno consen-

sus was reached,an additionalevaluatorwas prepared Arbeitswissenschaftliches erhebungsverfahren zur tätig-

to participate

in thediscussion, in accordancewiththe keitsanalyse[(AET) ergonomiejob analysis procedure].

predetermined protocol.Thisoptionwas notneededin AET is a job and stress analysis procedure offeringa

any case. broad-spectrumdescription of work characteristics.

Scand J WorkEnvironHealth 2010, vol 36, no 1 5

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Systematicevaluationofobservationalmethods

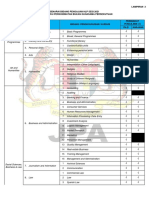

Table 1. Description

ofobservationalmethods.Exposuresincludedinthe method:posture(P), force(F), duration(D), frequencyofac-

(Vib). (RPE=ratingof perceivedexertion;NIOSH=NationalInstitute

tions(Fr),movements(M), and vibration of OccupationalSafetyand

Health;VAS=visualanalogscale; TLV=thresholdlimitvalue; MMH=manualmaterialhandling)

Method and Target

exposures Metrics Observation Modeofrecording

yearoffirst

publication anddimensions strategy

Generalmethods

Ovakoworking posture P,F ofitems

Frequency Timesampling Pen& paper,

assessment system (OWAS),1973 computerized

erhebungsyerfahrenP,F,Fr,Vib

Arbeitswissenschaftliches Profile

ofitems Nodetailed

rules Pen& paper

zurtätigkeitsanalyse

[(AET)ergonomiejob

analysis

procedure], 1979

Posture 1979

targeting, P Frequencyofpostures Nodetailedrules Pen& paper

Ergonomie analysis

(ERGAN), 1982 - BorgRPEscale Nodetailedrules Video,computerized

Taskrecordingandanalysis oncomputer P,F,D,Fr, Timesampling/

Distribution/duration Computerized

(TRAC),1992 ofobserveditems continuousobservations

Portable

ergonomie observation (PEO),1994 P,F,D,Fr,M Start/end

ofpostures Continuous observations video

Computerized,

Handsrelativetothebody(HARBO), 1995 P ofpostures Continuous

Start/end observations video

Computerized,

av belastningsfaktorer P,F,Fr,M

Planforidentifiering Yes/noanswers; Selection

bygeneral Pen& paper

[(PLIBEL)a method assignedfortheidentification ofitems

profile knowledgeofwork

ofergonomics hazards], 1995 andobservations

Posture, toolsandhandling

activity, 1996 P,F,workactivity

(PATH), Timespentinpostures Timesampling Pen& paper,

(video)

computerized

check(QEC),1999

Quickexposure P,F,D,Fr,M Sumscoreof "Worstcase" Pen& paper

weighteditems ofthetask

bodyassessment

Rapidentire 2000

(REBA), P,F Sumscoreof Mostcommon/ Pen& paper

weighteditems prolonged/loaded/postures

Stateergonomie

Washington checklists,

2000, P,F,D,Fr,M,Vib Yes/noanswers fortasks

Screening Pen& paper

thatareregularinwork

Video-ochdatorbaseradarbetsanalys

[(VIDAR) P,F,D,Fr,M Borg RPE scale Byworker's

needs video

Computerized,

a video-andcomputer-basedmethodfor

ergonomie 2000

assessments],

Posturalloadingontheupper-body P Posture

discomfort

scoreMostcommon/loaded Pen& paper,

video

assessment (LUBA),2001 postures

Chung's workload

postural 2002

evaluation, P Posture scoreNodetailed

discomfort rules video

Computerized,

Methodsassessingworkload onupperlimbs

HealthandSafety Executive risk

(HSE)upper-limb P,F,D,Fr,Vib Yes/no

answers Tasksinvolving

high Pen& paper

assessment method,1990 variety

repetition/low

Stetson's 1991

checklist, P,F,D,Fr Frequency ofitems Nodetailed

rules Pen& paper

bytheirduration

assessment

Rapidupper-limb 1993

(RULA), P,F,staticaction Sumscoreofweighted Nodetailed rules Pen& paper,

video

items

cumulative

Keyserling's trauma 1993

checklist, P,F,D,Fr,Vib Sumscoreofpositive Screening ofjobwith Pen& paper

findings questionsputtotheworker

Strain 1995

index, P,F,D,Fr score;

Multiplied Nodetailed rules Pen& paper

riskindex

(OCRA),1996

Actions

Repetitive

Occupational P,F,D,Fr,Vib Sumscoreofweighted Assessment ofrepetitive Pen& paper

items;riskindex actionincl.inprofile

ofwork

Conference

American ofGovernmentalIndustrial M,F, Handactivity& force "Typical activity" Pen& paper,

(video)

handactivity

Hygienists level(ACGIHHAL),1997 requirementonVAS

Stateergonomie

Washington 2000

checklists, P,F,D,Fr,Vib Yes/notoquestions Itemsselectedby Pen& paper

combining riskfactors cautionzonechecklist

Ketola's

upper-limb tool,2001

expert P,F,D,Fr,Vib Yes/noanswers; Nodetailed rules Pen& paper

ofitems

profile

Methods

assessingmainlymanualmaterial

handling

NIOSHlifting 1981(revised

equation, 1991) P,F,D,Fr Multipliedscore; Nodetailed rules Pen& paper,

riskindex computerized

1997

Arbouw, P,F,D,Fr 3 levelsofrisktables Nodetailed rules Pen& paper

NewZealandcodeformaterial 2001

handling, P,F,D,Fr Sumscoreofweighted Flowchart; tasksincluding Pen& paper

itemsindicating risk hazardous MMH

charts(MAC),2002 P,F,Fr

assessment

Manualhandling Itemprofile; sumscore Selectionbygeneral Pen& paper,

(video)

indicatingrisk knowledge ofwork

Stateergonomie

Washington 2000

checklists, P,F,D, Fr limit

Lifting computed Worst & most Pen& paper

as multiplied score common lifts

tasksriskassessment

Manual 2004

(ManTRA), P,F,D, Fr,Vib Sumscoreofrisk RulesstatedinQueensland Pen& paper

manual tasksadvisorystandard

ACGIH TLV,

lifting 2004 P,F,D, Fr Hazardous TLV Nodetailed

lifting rules Pen& paper

Sampling

Back-Exposure 2008

Tool(BackEst), P,F,Vib Frequency ofitems Timesampling Pen& paper

6 Scand J WorkEnvironHealth2010, vol 36, no 1

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Takala et al

Table 2. Validity

and repeatability methods[- insufficientinformation;

ofobservational NIOSH=l'lational

Institute

ofOccupationalSafety

and Health;MMH=manualmaterialhandling]

Method Correspondencewith Associationwith Intra-observer Inter-observer

a

'valid'reference musculoskeletal repeatability repeatability

disorders(MSD) b

Generalmethods

Ovakoworkingposture Moderate(discomfort, X Good Good

assessmentsystem(OWAS) technicalmeasures)

Arbeitswissenschaftliches - -

erhebungsverfahren

zurtätigkeitsanalyse

[(AET) ergonomiejob

analysisprocedure]

Posturetargeting - -

- -

Ergonomieanalysis(ERGAN)

Taskrecordingand analysison computer(TRAC) Moderate(technicalmeasures) X -

Moderate-good

Portableergonomieobservation(PEO) Moderate(video,technicalmeasures) X Good Moderate-good

Hands relativeto the body(HARBO) Moderate(technicalmeasures) - - Good

Planforidentifiering

av belastningsfaktorer Moderate(AET) - - Moderate

[(PLIBEL) a methodassignedforthe identification

ofergonomicshazards]

tools and handling(PATH)

Posture,activity, Moderate-good -

Moderate-good Moderate-good

(video,technicalmeasures)

Quickexposurecheck(QEC) Good (video,technicalmeasures) X Moderate Moderate

Rapidentirebodyassessment (REBA) Moderate(OWAS) - - Low-moderate

WashingtonStateergonomiechecklists Moderate X - Moderate

Video-och datorbaseradarbetsanalys[(VIDAR) - -

a video-and computer-basedmethodfor

ergonomieassessments]

Posturalloadingon the upper-body

assessment (LUBA) - -

Chung'sposturalworkloadevaluationsystem - -

Methodsto assess workloadon upperlimbs

Healthand SafetyExecutive(HSE) upper-limb - -

riskassessment method

Stetson'schecklist - - Moderate

assessment (RULA)

Rapidupper-limb Low-moderate(technicalmeasures,

ACGIHHAL,OCRA,strainindex) X -

Moderate-good

cumulativetraumachecklist

Keyserling's Moderate(video,workplacedata) - - Low-moderate

Strainindex(SI) Moderate(RULA,ACGIHHAL) L, X Moderate-good Moderate-good

Actions(OCRA)

OccupationalRepetitive Moderate(SI, RULA,ACGIHHAL) X -

AmericanConferenceofGovernmentalIndustrial Moderate(video,SI) L, X Good Moderate

handactivity

Hygienists level(ACGIHHAL)

WashingtonStateergonomiechecklists - X - Moderate

Ketola'supper-limb

experttool Low-moderate(technicalmeasures) - - Moderate

Methodsto assess mainlymanual materialhandling

NIOSH lifting

equation ■ X

Arbouw Moderate(NIOSH lifting

equation) - -

NewZealandcode formaterialhandling - -

Manualhandlingassessmentcharts(MAC) - -

Moderate-good Moderate-good

WashingtonStateergonomiechecklists Moderate(NIOSH lifting

equation) X - Moderate

Manualtasks riskassessment (ManTRA) - -

ACGIHlifting

thresholdlimitvalue Moderate(NIOSH lifting

equation) -

Back-exposuresamplingtool (BackEst) Low-moderate(technicalmeasures) - - Moderate

a withvalidreference/repeatability:

Correspondence Good, Moderate,Low,

bAssociationwithmusculoskeletaldisorders:X = associationin cross-sectionalstudies;L = predictionin longitudinal

studies,

Scand J WorkEnvironHealth 2010, vol 36, no 1 7

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Systematicevaluationofobservationalmethods

to observationalmethods.(R=Researchers;(^Occupational safety/health

Table 3. Practicalissues relating practitioners/ergonomists;

W=Workers/supervisors; - insufficientinformation;

?=notclear;l'IIOSH=National

Institute

ofOccupationalSafetyand Health)

Method Strengths Limitations Decisionrules Potential

users

Generalmethods

Ovakoworking as-

posture usedanddocumented

Widely Doesnotseparate

rightandleft Decisionrules R

sessment

system(OWAS) upperextremities.

Assessments basedonfrequency

ofneckandelbows/wrists

are distribution

are

Posture

missing. coding crudefor arbitrary

shoulders. Does

Time-consuming.

notconsider orduration

repetition

ofthesequential

postures

Arbeitswissenschaftliches Givesa broaddescriptionofworkcharacteris- Only17 itemsof216 aretargetedTentative:"high" R

zurtätig- tics.Largeexperience

erhebungsverfahren anddatabank ofresults toassess musculoskeletal load scoresindicate

poten-

keitsanalyse

[(AET)ergonomie from variousfieldsofoccupations

tobe usedas harmful

tially jobs

jobanalysis

procedure] reference.

Posture

targeting Illustrative

output:The ofthepos-

presentation Suitable

onlyforstaticpos- - O,R

turesinpolarcoordinatesprovidesquantitative tures.Does notconsider dura-

measures onordinal arepossibleto tionandfrequency.

scales,which Itis hardto

validate

using,forexample, technical

measures, observemanybodysegments

simultaneously.

Ergonomie (ERGAN) Computerized

analysis illustrative

registration; output Time-consuming. of -

Availability ?

thesoftwareunknown.

Taskrecording on Computerized

andanalysis thesoftware

registration; counts Mainlyfocussedonassessing - O,R

computer(TRAC) distribution andduration

offrequency ofthe exposure can

levels;frequencies

events. toselecttheitemstobe

Flexibility onlyinthereal-time

be retrieved

observed tothepurpose.

according set-upofthemethod.

Portable observa- Themethod

ergonomie ofposture

enablesregistration ofsoftware

Availability unknown.- R

tion(PEO) Thedataallowsfurther

duration. for

analysis Time-consuming ifdetailed

data

different

purposes is needed.Ifworkpaceis rapid,

theassessment ofseveralexpo-

surecategoriesis notpossible

tothebody

Handsrelative simpleto use.Registers

Easyto learn, the only5 postures

Registers tobe - R

(HARBO) durationoftheposturesoncomputer. usedas proxy forbodypostures.

ofsoftware

Availability unknown

av be-

Planforidentifiering General tool.

andsimplescreening Does notquantify therisk. Taskswitha higher 0

lastningsfaktorer

[(PLIBEL) Relative

lowrepeatabilitydue numberof"Yes"ticks

a method assignedforthe tothesubjectivedecisionsof mayrequire more

ofergonomics

identification "noVyes". immediateaction

hazards]

Posture, toolsand Thoroughly foreasyuseatworksite, Themethod

developed onlyaddresses - R

activity,

handling(PATH) including formaking

a procedure job-specific exposure levels,andonlyin

forobservation.

templates Thesamplingapproachrelative

durations.Requires

is systematic Dataarepro- considerable

andwell-designed. training

cessedinanautomatizedprocedureoncomputer.

check(QEC)

Quickexposure Easyto use.Applicable fora widerangeoftasks. Notsuitable, whentasksare Tentativelimits 0, W,

Takesaccountinteraction ofriskfactors. highly varied.

Concentrateson indicatinglevelofrisk R(?)

worktasks;theusermustdecide,

which tasksaremostloaded

bodyassessmentRapidtouse.Computerized

Rapidentire available Right

registration andlefthandhavetobe Tentativelimits 0, R(?)

(REBA) inpublicdomain. assessedseparately andthereis indicating levelofrisk

nomethod tocombine thisdata;

theuserhastodecidewhatto

observe.Duration andfrequency

ofitemsnotincluded

WashingtonStateergonomie Simple, quick,andtakesintoaccountmostrisk Limited toscreeningofrisks forward

Straight 0, W(?)

rulechecklists factorswithduration andfrequency. decisionrules.

Video-ochdatorbaserad Easytouse.Encourages ofworkers.Subjective

participation evaluationofloading BasedonQECand 0, W

arbetsanalys

[(VIDAR)a video-Illustrative

outputcanhelpworkers to understand is basedondiscomfort, which Swedishregulations

andcomputer-based method ergonomie problems intheirwork. mayhamper thedecisiononthe

forergonomie assessments] numerical in

valueespecially

groupassessment. General

ofvideo-recordings.

limitations

Postural

loading onthe Simple, easyto use.Scoring basedonphysio- Doesnotconsider force,durationFouractioncategories0(?), R(?)

upper-body logicaldata.Numeric output canmakethe andrepetition proposed bythe

assessment(LUBA) decisions easierthana qualitative

description. posturalindex

workload Computerized output. Does notconsider

Illustrative external - R,0(?)

Chung'spostural registration;

evaluation

system Combines video andratingof postures. forces.

(continued)

8 Scand J WorkEnvironHealth2010, vol 36, no 1

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Takala et al

Table 3. Continued.

Method Strengths Limitations Decision rules Potential

users

toassess workload

Methods onupperlimbs

Healthand SafetyExecutive Easyto use. Straightforwardquestions.Advice Does notconsiderinteraction of Tasks witha "Yes" 0, W(?)

(HSE) upper-limbrisk forpotentialsolutions. the riskfactors.Subjectiverating: ticksrequire

assessment method definitionofobserveditemsnot moredetailedrisk

alwaysclear.No metricmeasure assessment.

to quantifythe risk.

Stetson'schecklist Selectionof mostitemsbased on research Too manyitemsto be observed - R

literature. simultaneously. Does notconsid-

er the interaction

of riskfactors.

Evaluationofdurationofcycle

lengthsis probablyimpossible

withouta chronometer.

assessment Easyto use. Computerized

Rapidupper-limb available

registration Rightand lefthands haveto be Tentativelimits 0, R

(RULA) in publicdomain. assessed separatelybutthereis indicatinglevelof risk.

no methodavailableto combine

these scores. Does notconsider

durationofexposures.

cumulative

Keyserling's Quickand easy to use. Ratingsystemis qualitative.Does Itemswith"yes"ticks 0, R

traumachecklist notconsiderthe interaction

of should be considered

riskfactors. potentialforactions.

Strainindex(SI) The methodincludesmainriskfactorsfordistal Limitedto distalupperlimbexpo- Sensitivity and specifi- 0, R

upper-limbdisorders.Takes intoaccountthe sure/risk assessmentinmonotask cityof indexdescribed

interaction

ofobservedvariables.One figuregives jobs. Multipliervaluesare hypo- inthe literature,

comparisonofjobs. thetical.Subjectiveassessment;

definitions ofthecriteria

are not

veryclear.Does notconsider

vibration and contactstress.

OccupationalRepetitive Takes intoaccountrecoveryperiods.Estimates The use is timeconsuming.Well Cut-off

limitsindicai- 0, R

Actions(OCRA) theworkersrisklevelbyconsideringall the trainedobserversneeded. ingneeds foractions.

tasks ina complexjob. The checklistis

repetitive

easy and quickto use.

AmericanConferenceof Rapidand simpleto use. Intheassessment Subjectiveassessment. Coversa Clearthreshold 0, R

Governmental Industrial individual

capacityis considered. limitednumberof riskfactors. values foractionsfor

Hygienistshandactivity

level monotaskworkwith

(ACGIHHAL) duration>4 hours.

WashingtonStateergonomie Simple,quick,takes intoaccountmostrisk Limitedto screeningof risks. Straightforward 0, W(?)

checklists factorswithdurationand frequency. decisionrules.

Ketola'supper-limb

experttool Quick,easy to use. Ratingsystemis qualitative.Does Itemswith"yes"ticks 0

notcombinethedurationand should be considered

otherriskfactors. potentialforactions.

Methodsto assess mainlymanual materialhandling

NIOSH lifting

equation Welldocumentedand testedinseverallaboratory Plentyof practicallimitationsfor Clearthresholdvalues 0, R

studies.Sound backgroundbased on scientific use. Requirement ofseveraltech- indicating

actions,

studies.Outcomerelatedto the riskofthe health nicalmeasuresand calculations

ofback. Calculatorsavailablein internet means increasedrequirements

forskillsand timeto makethe

estimation.

Arbouw Coverslifting, pushing,and pulling.

carrying, Relativetime-consuming,but Clearthresholdvalues 0

does notgiveverydetailed actions,

indicating

information.

NewZealandcode formaterial Includesinformation on riskfactorsand solution The user has to makemany Clearthresholdvalues 0

handling ideas; takesaccountmanyimportant factorssuch decisionswithvague rules. actions,

indicating

as size and shape ofthe load and slipperyfloor.

Manualhandlingassessment Relativesimpleand easy to use. Welldescribed Assesses onlymonotonous Fourlevelgradingfor 0, W(?)

charts(MAC) process forassessment. tasks,notjobs or com- actionlimits.

lift/carry

poundtasks. Includesfrequency

butnotdurationofthe lifting.

WashingtonStateergonomie Simple,quick,takes intoaccountmostrisk Limitedto screeningof risks. Straightforward 0, W(?)

checklists factorswithdurationand frequency. decisionrules.

Manualtasks riskassessment Quickand easy to use. Takes intoaccountforthe Definitionofthe criterianotvery Proposed limitsfor 0, R(?),

(ManTRA) generalriskof manualmaterialhandling(also clear;subjectiveassessment. Not actioncategories. W(?)

durationand repetition). clear howto combinemultiple

tasks to geta job levelexposure.

ACGIHlifting

thresholdlimit Quick,easy to use Limitedto two-handedmono- Clearthresholdvalues 0

value tasks.

lifting foractions.

Back-exposuresamplingtool Quitesimple.A thoroughvalidationdata against Time-consuming due to the - R

(BackEst) technicalmeasuresgivesa possibility to samplingstrategy.

transformtheobservedresultsaccordingly

Scand J WorkEnvironHealth 2010, vol 36, no 1 9

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Systematicevaluationofobservationalmethods

Thejob itselfis evaluated- nottheindividualdoing correspondencewithtechnicalmeasurements (30).

thejob. Of216 items,143 concerntheperson-at-work Inter-observer has

repeatability been to

moderate good

system,31 deal withthe analysisof tasks,and 42 (29-31).

relateto an analysisofjob demands.Of theselast42

items,17 are directlyrelatedto muscularwork(ie, Portableergonomieobservation(PEO). PEO is a method

analysisof demands/activity). In codingthe items, forthecontinuous computer-based observation ofwork-

theusershouldcombineobservations at theworksite ersattheworkplace. Every time the worker adoptsa new

withinterviews. The datacan be used to characterize predefined posture, performs an action, or movesfrom

thejob ortaskprofile.A databasewithover7000jobs oneposture toanother, theobserver hitsthecorrespond-

servesas a referenceforcomparisons(21-23). We ingkeysand thesoftware recordsthestarttimeof the

foundno studiescomparing AET observations related event.Whentheposturechanges,or whentheactivity

to musculoskeletal load withmorevalid measures. is terminated,theobserver hitsthesamekeyagain.This

Inter-observer has been studied,butthe

repeatability triggersthe software to calculate andstoretheduration

reportsonlygivefigures thewholemethodandno

for ofthisparticular event.Fromthisinformation, anchored

separateresultsforthepartrelatedto musculoskeletal in realtime,thesoftware calculatesthefrequency and

workload(21, 23-25). durationof each itemforthe observationperiod.If

thefrequency and/or totaltimeof theobservedtaskis

Ergonomieanalysis (ERGAN,formerly ARBAN). In the known, the software calculates thecumulative frequency

ERGAN method, the work situationis filmed and the and duration of postures or actions fora longerperiod

workload ondifferent bodypartsis assessedfromsingle (day/week). Theinformation ondailyfrequency oftasks

framesof the video using Borg's scale. Events are needed for the calculation of cumulative exposuresis

in

countedand registered timefrom video recordings. obtained by interviews or production output(32). The

Theseobservations have beenused as input for com- method has shown moderate-to-good correspondence

putersoftware thatgivestheworkloadprofilein time withdata obtainedby video (32) and directtechni-

sequences(26). No studiestesting thevalidity orrepeat- cal measures(33, 34). An associationbetweenPEO

abilityofthemethod werefound. observations and musculoskeletal discomfort has been

seen in cross-sectional studies(35, 36). Intra-observer

Posture Theposture

targeting. targetingmethod involves repeatability has beengood(32, 37) andinter-observer

theobservation of staticpostureswithrespectto the repeatability beenmoderate

has to good(32).

"standard"anatomicalposition,whichis selectedas

thecentreof the"target"of each bodypart.A target Handsrelativeto thebody(HARBO).The HARBO method

comprisesfourconcentriccircles- similarto polar was developedto assess exposuresin epidemiological

-

coordinatesrepresenting anglesof45°,90°,and 135° studiesor ergonomie prevention and intervention pro-

deviations fromtheneutral, centerposition.Deviations gramsinall typesofjobs. Five postures, defined through

are markedby a cross on targets,whichshows the thepositionof thehands,can be measuredforseveral

frequency ofpostures duringtheobservedperiod(27). hours:(i) standing/walking withhandsabove shoulder

Fieldobservations havebeencomparedwithobserva- level;(ii) standing/walking withhandsbetween shoulder

tionsmadefromsimultaneous photographs (27). How- andknuckle level,notfixedwithload;(iii)standing/walk-

ever,thetrialwas so inadequately describedthatwe ingwithhandsbetween shoulder andknuckle level,fixed

couldnotevaluatevalidity orrepeatability. withload;(iv) standing/walking withhands fixed below

knucklelevel;and(v) sitting. Thepositionofthehands

Taskrecording and analysison computer(TRAC).TRAC is regardedas a proxyforpostural demandsontheneck,

is a genericmethod torecordtasks,actions,orpostures shoulders, and lowerback.Observations are madeand

in realtimeor withcomputerized timesampling.The registeredin realtimewith a hand-held computer using

eventsto be observed(eg, posturesin a particular cat- thesoftware originally developedforthePEO method

egory)mustbe defined a priori.Real-time observations (38). Observations havebeenmoderately correlated with

allowusersto analyzeboththeduration andsequence direct technical measurements of arm and trunk postures.

oftheselectedeventsandcontextual factorsofinterest The inter-observer repeatabilityhas beengood(38). No

during theseevents(28). In themulti-moment applica- reports on associations withMSD werefound.

tion,theobserver mustmonitor thesituationrepeatedly

atpreviously selectedtimeintervals, givenas auditory Plan foridentifiering av belastningsfaktorer [(PLIBEL) a

signalsfromthecomputer. Posturecategories inTRAC methodassigned forthe identificationof ergonomicshaz-

are user-configurable and a numberof applications ards]. PLIBEL is a simplechecklist, intended as a rapid

have adoptedtheOWAS categorization scheme(29). screening tool of majorergonomie riskswhich mayhave

TRAC observations ofpostureshaveshownmoderate injurious effects on the musculoskeletal system.Time

10 Scand J WorkEnvironHealth2010, vol 36, no 1

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Takala et al

aspectsand environmental and organizationalfactors scales using "fuzzylogic" (ie, using non-technical

are also includedas hazardmodifiers(39, 40). Some languagewithoutexactbordersbetweentheclasses).

of theitemsforclassifyingtheworkplacehaveshown In addition,theobservedworkeris requiredto (self)

moderatecorrespondence withsimilaritemsin AET, ratetheweightshandled,thedailytimespentdoingthe

andtheinter-observer has beenmoderate

repeatability observedtask,thelevelof handforceinvolved,visual

to good (39). No reportson associationswithMSD demands, driving ofvehicles,theuse ofvibrating tools,

werefound. anddifficultiesto keepup withtheworkas wellas the

stressfulness

ofthework.Theratings areweighted into

Posture, tools,andhandling

activity, (PATH). The basis of scores and added to

up summary scores for different

thePATHmethod is worksampling (ie,observing "snap- bodypartsand otheritems(driving,vibration, work

from

shots"), which a frequencydistributionof observed pace,and stress).Based on thesescores,priority levels

itemsis obtained.Beforethedatacollection, a template forintervention are proposedto providea basis for

mustbe customized forrelevantworkactivities, tools, decision-making and communication withinorganiza-

andhandling. Theclassificationofpostures is basedon tions(47-49). Back and shoulderpostureresultswere

OWAS (41, 42). PATHobservations haveshowngood foundto be well correlated withtechnicalmeasuresin

correspondence with observationsmade usinganother, simulatedtasks. (47, 49). QEC practioners' evaluations

less-welldescribedtool forthepostureassessmentof corresponded well to those ofexperts, and the intra- and

video recordings (41) and technical measurements in inter-observerrepeatability was moderate (48, 49). No

simulatedtasks(42). Intra-observer repeatabilitywas studieson associations with MSD were found.

good forarmand leg posturesbutless so forthoseof

theneckandtrunk. Inter-observer

repeatability hasbeen Washington Stateergonomie checklists.Thesechecklists

moderate to good(41). No reportson associations with weredevelopedas partofa regulatory effort to control

MSD werefound. exposureto musculoskeletal hazardsin workplacesin

the stateof Washington, USA. Epidemiologicaland

Rapid entire body assessment (REBA). REBA was otherscientific studieswerethebasis fortheselection

designedas a quick and easy observational postural of itemsto be observed.The evaluationof workplaces

analysis tool forwhole-body activitiesin healthcare coveringthemainhazardsformusculoskeletal disor-

and otherserviceindustries. The basic idea of REBA dersis doneby twochecklists:(i) the"cautionzone"

is similarto thatof therapidupper-limb assessment checklistis used as a screening tool; (ii) a morecom-

(RULA) method of

(see pl2): positions individual prehensive"hazardzone" checklistis used forthose

body segmentsare observed and postural scores jobs screenedto represent potentialhazards(50). Only

increasewhenposturesdeviatefromtheneutralposi- themanualmaterialhandlingaspectofthemethodhas

tion.GroupA includestrunk,neck,and legs, while beencomparedwithothermethods(51). Jobsobserved

groupB includesupperand lowerarmsand wrists. tohaveexcessiveexposures havehadhigher occurrence

These groupsare combinedintoone of 144 possible of MSD (52). The assessment has beenshownto have

posturecombinations thataretransformed to a general goodrepeatability amongobservers (53). (See pi 3 and

postural score ("grandscore").Additionalitemsare 14 fordetailson thosepartsofthechecklist concerning

observedandscoredincluding: theload handled,cou- ofupperlimbsandmanualmaterial handling.)

plingswiththeload,andphysicalactivity. Thesescores

aresummedup togiveone scoreforeachobservation, Video-och datorbaserad arbetsanalys [(VIDAR)a video-

whichcan thenbe comparedto tablesstatingriskat andcomputer-based method forergonomie assessments].

fivelevels,leadingtothenecessity ofactions(ranging VIDAR's approachdiffers fromthoseof thepreviously

from"none"to "necessarynow") (43-45). mentioned methods, all ofwhicharebasedon theobser-

REBA observations havecorresponded moderately vationof predefined posturesand otheritemsby an

to thoseof theOWAS method,althoughthe former externalobserver.VIDAR is a participative method,

classifiedmoreposturesto have a higherlevel of mainlybased on worker'sassessment (54, 55). It was

risk(18). No reportson associationswithMSD were developed tosupport participativeinterventions andergo-

found.Inter-observer repeatabilitywas moderateto nomicstraining atworkplaces. anemployee

First, is video

good forleg and trunkposturesbut low forupper recorded whenperforming his/herdailywork.He/she then

limbs(46). makesan assessment of physicallyandpsychologically

demanding situations.Forphysicalsituations, theworker

Quick exposure check(QEC).QEC is intended fortherapid marksaffected bodyregionsandratesperceived exertion

assessment oftasksafterminimal training ofobservers. usingBorg'scategory ratio(CR-10)scale.Twochecklist

The observerwatchesand ratesposturesof theback, moduleshavebeenaddedto theprogram: one is based

shoulder-arm, wrist-hand, and neck on 2- or 3-step ontheQEC andtheotheronofficial Swedishergonomie

Scand J WorkEnvironHealth 2010, vol 36, no 1 11

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Systematicevaluationofobservationalmethods

Thechecklists

regulations. wereimplementedto clearly scoresarethencomparedto tablesstating riskon four

pointto theneedsforintervention

and theabil-

increase levelsandtheactionsneeded(ranging from "acceptable"

ityofVID AR tomeasurethe of

effects No

interventions. to "immediate investigation and changeneeded")(60,

thevalidity

studiestesting ofthemethod

orrepeatability 61). RULA's posture scores have beenshownto have

werefound. low correspondence to thehand-useintensity scoresof

thestrainindex(see pi 3) (62). Still,in anotherstudy,

Posturalloading ontheupper-body assessment (LUBA).In it showedsaw-filers workto be riskyin linewiththe

LUBA analysis,postures areratedon scalesdeveloped evaluationsmadeusingREBA, theAmericanConfer-

frompsychophysical experiments recording discomfort ence of Governmental Industrial Hygienists threshold

incomparable postures. All scores aresummed up toone limit value for hand activity level (ACGIH HAL), the

scoredescribing theurgency ofintervention actions.The strain and

index, occupational repetitive actions(OCRA)

summary score of is to

postures compared experimental methods (see following pages)(63). Observations made

maximalholdingtimesin different postures, and this using RULA have also been compared with those using

analysisis usedtoformulate decisionrulesforthepriority theOWAS and REBA methods(18). The correspon-

ofactionsneeded(56). No studiestesting thevalidity or dencewithall thesemethods hasbeenmoderate atbest,

repeatabilityof the method were found. but it remains unknown which method better reflects

theunderlying MSD risksforvarying tasks(18). Higher

Chung's postural workloadevaluation system. In thisobser- RULA scores have shown an association withincreased

vationalmethod,posturesare ratedaccordingto a discomfort in laboratory studies(60, 64) andwithper-

"discomfort score"associatedwitheachjointposture ceptionsof MSD in two cross-sectional fieldstudies

of

orcombination postures. The more thejointposition (65, 66). The inter-observer repeatability RULA has

of

the

deviatesfromneutral, higher the score. The scores been found to be good, althoughthemethodological

havebeendetermined in a seriesof laboratory experi- information on therepeatability studiesis so scantthat

ments.Observations can be done in the workplace or the quality thereof cannot be evaluated (60, 66).

fromphotographs or videos. Computersoftwarehas

beendevelopedto helpcode andanalyzeobservations. Stetson'schecklistfortheanalysisof handand wrist.

The ratingofposturesis partlythesameas forLUBA Thismethodwas developedas a quantitative measure

(57, 58). No studiestesting thevalidityorrepeatability of repetitive hand exertions for studies of cumula-

ofthemethod werefound. tivetraumadisorders.Observedobjectsincludehand

exertionswhile usingpowertools,pinchgrip,high

force,palmas a striking tool,and "involuntary" wrist

Methods toassessworkload onupperlimbs deviation. The number of these exertions is recorded for

"standard" workcycles and classified by the duration of

HealthandSafety Executive (HSE)upper-limb riskassess- exertions. Thisinformation, multiplied by the number of

mentmethod. The HSE riskfilterand riskassessment workcyclespershift, a

produces quantifiable measure

worksheets providea two-stage assessment processto ofrepetitiveness (67). No studiestesting thevalidity of

helpreducework-related upper-limb disorders. As a first themethodwerefound.Inter-observer repeatability for

step,theriskfilter(includingquestionson symptoms thecountsof observedcycleshas beenreported to be

and generalriskfactorsforMSD) is used to identify moderate forpinchandexertion (67, 68).

situations wherea moredetailedassessment is neces-

sary.Riskassessment worksheets arethenusedto con- Keyserl ing'scumulative trauma checklist. The aim of the

ducta moredetailedriskassessment fortheseselected checklistis to determine thepresenceof ergonomie

tasks(59). No studiestesting thevalidityorrepeatability riskfactorsassociatedwiththedevelopment of upper-

ofthemethod werefound. extremity cumulative trauma disorders. Repetitiveness,

local contactstresses,forceful manualexertions, awk-

Rapidupper-limb assessment(RULA).In the RULA wardupper-extremity posture, and hand-tool usageare

method,positionsof individualbody segmentsare evaluated; each detected risk factor is recommended

observed andscored,withscoresincreasing inlinewith to be further evaluated(69). The methodhas shown

growingdeviationfromtheneutralposture.Summary moderate correspondence withobservations fromvideo

scoresare firstcalculatedseparatelyforbothupper recordings postures, of contact forces, and tooluse,as

and lowerarmsand wrists(groupA) and trunk, neck well as with productoutput data describing repetitive-

and legs (groupB), andthentransformed to a general ness (69). No studieson associationswithMSD were

postural "grandscore".Additional weightsaregivento found.The inter-observer repeatability has beenfairto

thepostures according to forces/loads handledandthe moderate for pinchgrip and shoulder elevation above

occurrence of static/repetitivemuscularactivity. These but

45°, poor for wrist deviations (68).

12 Scand J WorkEnvironHealth2010, vol 36, no 1

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Takala et al

Ketola'supper-limb expert tool.Thisis a semi-quantitative (normalized ona scaleof0-10) orestimated bya trained

time-based methodforassessingthepresence("yes"or observer using a modified Borg CR- 10 perceivedeffort

"no") of riskfactors for upper-limb disorders. The limits scale. Peak force is judged relativeto thepopulation

for"yes"versus"no"aredefined by the time proportion characteristics at the evaluated worksite, so depends

and

ofthecycle,during whichtheexposureoccursas inthe on factors likeage andgender. Thecombination ofHAL

Keyserling's checklist. A higher total number of "yes" and peak hand force is evaluated against two limits:one

answersleadsto a greater predicted risk of the

upper-limb indicating necessity ofthe action and the other show-

disorders (70). Whenexpertobservation was used as a ingan absolutemaximum allowanceforhand-intensive

reference standard, has

validity ranged from moderate to work (81).The method was originally validatedagainst

for

good repetitive use of the hand, hand force,pinchgrip, detailed information from video recordings(number

andnon-neutral wristposture. Correspondence was low ofexertions persecond,recovery timepercycle,cycle

whentheobservations werevalidated against wrist gonio- time)withwhichit showedmoderatecorrespondence

metrie dataandforceestimations byelectromyography.(82). Theactionthreshold levelshavebeencompared to

No studiesontheassociation withMSD werefound. The thosegenerated by the strain index. The correspondence

inter-observer repeatabilityhasbeenmoderate (70). hasbeenmoderate, eventhoughthestrainindexidenti-

fiedmorehazardousjobs thantheHAL method(74,

Strainindex.The strainindexis a semi-quantitative job 75). An associationwithupper-limb disorders hasbeen

analysis method yielding a numerical score, which is seen in several cross-sectional studies(75, 78,83,84) as

intended to correlatewiththeriskof developingdis- wellas inprospective longitudinal studies (85-90). The

tal upper-extremity disorders. Accordingto theindex intra- andinter-observer repeatability hasbeenmoderate

six taskvariablesdescribinghandexertionsmustbe to good(82, 91).

observedand scoredon fivelevels.The six variables

include:(i) intensity of exertion, (ii) duration of exer- Occupational repetitive actions(OCRA).OCRA is a syn-

tion,(iii) exertions perminute, (iv) hand-wrist posture, theticindexdescribing riskfactors relatedto repetitive

(v) speedof work,and (vi) duration of workperday. actionsat work.The indexis thetotalnumber oftech-

Each score is thenweightedbased on physiological nicalactionsperformed duringtheshiftdividedbythe

(endurance, fatigue,recovery), biomechanical (internal totalnumberof recommended technicalactions.The

forces, nonlinear relationship betweenstrainandinten- latteris countedfromobservedactionsmultiplied by

sityofeffort), andepidemiological principles. Multiply- weightsgivenforthefollowingfactors:muscleforce,

ingtheweighted scoresgivesa singlefigure: thestrain postureofthepartsoftheupperlimb,lackofrecovery

index(71, 72). Comparisonof theindexwithRULA periods,thedailyduration of therepetitive work,and

has showna limitedcorrespondence withrespectto the "additionalfactors".A simplifiedOCRA checklistis

identification of risks(62, 73). The correspondence of intendedforuse as a preliminary screeningtool (92-

thestrain indexwithACGIHHAL (see below)wasmod- 95). OCRA has shownmoderatecorrespondence with

erate,buttheformer gavegenerally higher riskestimates ACGIH HAL andthestrainindex(63, 96). Prevalence

thanthelatter(74, 75). It is notknownwhichof these ofupper-limb disorders has beengreaterinjobs witha

methodsis morevalidto assess risk.In a prospective higher, as opposedto lowerOCRA index(97, 98). No

study,thesensitivity was 0.91 andthespecificity 0.83 to studieson therepeatability ofthemethodwerefound.

predict upper-limb disorders, whenusinga cut-off point

ofstrainindex=5.0(76). Clearassociations withupper- Washington Stateergonomie checklists.

The Washington

limbdisorders havealso beendemonstrated in several Stateergonomie checklists includesthefollowing items

retrospective studies(71, 75, 77, 78). Intra-observer toevaluatetherisksforupper-limb disorders: (i) working

and inter-observer repeatability have beenreported to withelevatedarms,(ii) highhandforce, (iii)highly repet-

be moderate to good(79, 80). itivemotions, and(iv) highimpactonthehand.Thesen-

sitivityandspecificity ofthetoolto identify upper-limb

TheAmerican Conference ofGovernmental Industrial Hygien- disorders hasbeenfoundtobe low(52). Thechecklist has

iststhreshold limitvalueforhandactivity level(ACGIHHAL). shownmoderate inter-observer repeatability (53).

TheACGIHHAL evaluatestheriskofdeveloping disor-

dersinthehand,wrist,orforearm on thebasisofHAL

andpeakhandforces.It is aimedat theassessment Methods toassess manual material handling

of

single-task jobs with at least four hoursperdayofrepet- US NationalInstituteof OccupationalSafetyand Health

itivehandwork. HAL is ratedona visual-analogue scale (NIOSH)lifting equation.The NIOSH liftingequation

(VAS) of0-10 andaddressesexertion frequency, recov- methodwas developedto assess theriskof low-back

erytime,and thespeedof motion.Peak forcecan be disordersin jobs withrepeatedlifting.Six factors

measured usinga straingaugeorotherinstrumentation I relatedto the liftingconditionsshouldbe observed

Scan d J WorkEnvironHealth 2010, vol 36, no 1 13

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Systematicevaluationofobservationalmethods

andentered intoan equation,yieldinga recommended thereby generatesolutionsforcontrollingrisksassoci-

weight limit forthe task. Multipliersare based on atedwitheach factor. Fromthis,theimportance ofthe

biomechanical, physiological,psycho-physiological, riskis assessed and an actionplan is establishedfor

andepidemiological data.The liftingindex(LI) is the controlthereof(114,115).No studiestesting

thevalidity

ratiooftheactualweighthandledtotherecommended orrepeatabilityofthemethodwerefound.

weightlimit.LI values below 1.0 are regardedto be

safe fortheaveragepopulation,and the greaterthe Manualtasksriskassessment(ManTRA). ManTRAwas

indexthegreater theriskoflow-backinjury(99-101). developed toassistsafetyinspectorsauditing workplaces

The LI is restrictedtojobs consisting of one or a few acrossall industriesforcompliance withtheQueensland

similarliftingtasks.Forjobs withmultipletasks,pro- (Australia)manualtasksadvisory standard(116).Foreach

cedureshavebeenproposedto calculatea composite taskina job,theobserver ratesona 5-stepscale:(i) total

LI (100, 101) or a sequentialLI (102) fortheoverall timespentonthetaskduring a typicalday,(ii) repetition

job. The resultsof usingtheNIOSH liftingequation (combination of duration and cycletime),(iii) exertion

havebeencomparedwiththoseof severalothermeth- (combination of forcerequirements andspeedofmove-

ods (15, 51, 103-106),butit is notpossibleto state ments),(iv) awkwardness (deviationfrom themidrange

whether anyofthesemethodsaremorevalidthanthe of movements), and (v) vibration.The scale relatesto

liftingequation.Due to itscomplexstructure ofmulti- fourbodyregions(ie, lowerlimbs,back,neck-shoulder,

in

pliers defining the recommended weightlimit,there arm-wrist-hand). Highscoresof individual itemsor a

areno technical measures that can be used as a "gold highsummary scoreareassumed toindicate an increased

standard" forthe NIOSH evaluation. riskforMSD (117, 118).No studiestesting thevalidity

A sensitivity analysisof laboratorysimulations orrepeatability ofthemethod werefound.

has shownthatfrequency and horizontallocationare

themostdecisiveparameters in theNIOSH equation, Manualhandling assessmentcharts(MAC).MAC is a

butthattheseparameters also tendedto havethehigh- designedtohelphealthandsafety

checklist inspectorsto

est measurement errors(107). Several studieshave assessthemostcommonriskfactors inlifting,

carrying,

foundtheoccurrenceof low-backpain to be higher and teamhandlingoperations. The methodsetsout 11

in jobs witha higherLI (108-111). Inter-observer itemsof manualhandling to be evaluatedaccordingto

variabilityof measureshad littleinfluenceon the a four-grade light";a summary

"traffic scoreis counted

totalLI exceptin situations wherelargeweightswere those

to prioritize tasks that requireurgentattention

handled(112). and check the effectiveness of those improvements

(119-121). The properties the methodhave been

of

Arbouw guidelineson physicalworkload.The Arbouw benchmarked againstseveralothermethods ina qualita-

methodwas developed forthe assessmentof five tivemanner (120),but no formal comparison onvalidity

areasofmanualmaterial pushingand

lifting,

handling: was found.Theassessment has shown moderate-to-good

pulling,carrying,staticload,andrepetitivework.The intra-and inter-observerrepeatabilityon observations

guidelinesare based on theNIOSH liftingequation fromvideorecordings (122, 123).

and standardsformanualmaterialhandling.A traffic

light(green,yellow,red)approachis appliedto guide formanualhandling.

Stateergonomiechecklist

Washington

recommended actions(113). TheArbouwlifting guide- The liftinganalysisincludedin thischecklist is a sim-

linescan be consideredas a simplifiedversionof the plifiedversionof theNIOSH lifting equation,butthe

NIOSH lifting equation(15). TheArbouwmethodhas Washington checklistallowshigher acceptableweights of

showna moderatecorrespondence withresultsfrom thehandledload(124). In a comparative the

trial, method

theNIOSH method(15). No studieswere foundon indicateda substantiallylowerrisklevelin a particular

eitheritsassociationwithMSD or itsrepeatability. job thantheNIOSH lifting equation,buttheresults were

similarto thoseobtained using a biomechanical model

NewZealandcode ofpracticeformanualhandling.In the (51). Whenusedto detect jobs withan increased riskof

New Zealandcode,manualmaterial handling risksare backdisorders,thechecklist showed moderate sensitivity

firstevaluatedby meansof a checklist.If thisinitial (52). Theassessment

andspecificity hasshownmoderate

screening hazard,a detailedobser-

suggestsa potential inter-observer

repeatability (53).

vationalcheckis performed to calculatea riskscore,

whichservesas a guideon theurgencyand typeof thresholdlimitvalue forlow-backrisk.The

ACGIHlifting

controlmeasurerequiredto reducetherisk.If therisk ACGIH lifting limitvalue is estimated

threshold from

score is >10, a "factorsassessment"can be used to thelocationofthehandledmaterialrelativetothebody,

determine thesignificanceof contributingfactors(ie, and dailyduration

as well as thefrequency of lifting.

load,environment, people,task,andmanagement) and ACGIH providestablessettingoutthethreshold limit

14 Scand J WorkEnvironHealth2010, vol 36, no 1

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Takala et al

valueforweights, belowwhichnohealthriskis assumed presentevaluation we includedonlythosemethods with

to occur.The method was developedto ensurea lifting observations as theprincipal component.

guidelinethatwas accurate,basedonthelatestscientific Theaimofourevaluation wastopresent information

information,and easyto use (125). TheACGIH lifting thatmayhelppotential usersselectthemostappropri-

threshold limitvalue methodhas shownmoderate-to- ate method(s)fortheirparticular purpose.In situations

highcorrespondence withresultsobtained

bytheNIOSH wherepracticalergonomie problems haveto be solved,

equationandSnook'spsychophysical

lifting methodfor simplicity, and

utility, face of

validity themethodare

setting

liftinglimits

(51). No studies

werefoundoneither moreimportant thanexpressing resultsinexactnumeric

associationswithMSD orrepeatability. figures 8, and

(6, 128).Validity repeatability ofdataare

particularly important in research and when comparing

Back-exposure samplingtool(BackEST).In connectionwith exposuresto safetylimits.Thus the selectionof the

a large-scaleepidemiological study,BackEST aimedto mostappropriate toolmustinvolveconsideration ofthe

evaluatephysicalbackinjury riskfactorsindemanding analysis'objectivesandhowtheresultswillbe used- a

workconditions. In thedevelopment phase,a literature tooltohelpidentify improvement opportunitiesmaynot

reviewsuggested 53 relevant exposure variables; these have the same precision requirements as one beingused

werereducedto 20 itemsconcerning posture, manual to the

judge safety job ofa in a pass-fail determination

materialhandling, andwhole-body vibration.Theitems process.

wereobservedonceevery60 secondsovera full-shift

to producedatathatcan be analyzedaccordingto the

and

research(126). The propor- Validity repeatability

ofobservational methods

purposesof theindividual

tionoftimeindemanding backpostures was compared The conceptofvalidityincludesseveralaspects(1,2).

withtechnical measuresandthematchwas foundtobe Since thereis no "gold standard" to measurephysical

moderate at best,although thefinding may have been workload, criterion in

validitywas, thisstudy, assessed

affected by the different samplingprocedures of the interms of concurrent validity(ie, theagreement ofthe

comparedtools(126). Inter-observer repeatability has observationalmethodwithsome othermeasurement

beenmoderate (126). methodconsidered to be morevalid).Of the30 meth-

ods includedinourreview,19 hadbeencomparedwith

someothermethod(s), varying fromexpertevaluations

to observations madefromvideorecordings, anddirect

Discussion measurements withtechnical instruments. the

Generally,

worksite observation methods showedmoderate-to-good

Observation-based assessments ofbiomechanical expo- agreement withmeasuresbased on visualrecordings,

sures(physicalloads) on themusculoskeletal system and thecorrespondence was bestformacro-postures and

havemostly beentargeted atpostures ofthewholebody workactions.Micro-postures [likethoseofthewristand

or individual bodyregions,as well as exertedmanual hand(67, 70, 129),neck(34) andtrunk rotation(126)]

forcesor weightshandledmanually. Still,thereare no seemto be moredifficult to observewithsatisfactory

commonmetricswhichenablea directcomparison of accuracy.

thedifferent methods, although previous reviews have Whentechnical measurements haveservedas refer-

applied several approaches toovercome this problem. In ence, correspondence has generallybeen lowerthan

hisreviewof12methods, Genaidy(3) classified postures whenusingvideo-basedobservations as thereference

intomacro-or micro-postural or postural-work activi- (14, 30, 33, 34, 70, 126). In thesecomparisons, the

ties.In otherreviews,anglesusedfortheclassification variablesof interesthave been mainlyfrequency or

of posturesand scales of otheritemsof methodshave durationof posturesclassifiedaccordingto category

beentabulated (4, 5, 7). A generalconclusionof these limitsset by theobservational method.This kindof

reviewsis thattheobservational variablesgenerated by comparison maybe sensitiveto the"borderlines"of

differentmethodsare notdirectly comparable, mainly thecategories(32, 34, 67, 129-132). In otherwords,

duetotheuse ofdifferent bodyanglesoranglesectors. iftheobserver'sperception is systematically biasedin

Somereviewshavemainlybeendevotedto describing comparison to thelimitused by theaccuratetechnical

existingmethods published intheliterature(6, 8). Valid- method, theprobability ofhavinga highcorrespondence

and

ity repeatability ofthe methods has been addressed will decreaseifthetruepostureis close to a category

intwoprevious reviews(4, 7), inwhichsomestatistical borderline("boundary zone problem").Thissourceof

figuresof intra- andinter-observer repeatabilityas well disagreement was seen in some reports,forinstance

as descriptions oftestson internal andexternal validity whencategorizing severeand moderatetrunkflexion

havebeentabulated.Severalworkloadstandards also postures inPATH(41). Unfortunately, noneofthestud-

containitemsmeantto be observed(127), butin the ies had conducteda sensitivity analysisto see if the

Scand J WorkEnvironHealth 2010, vol 36, no 1 15

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Systematicevaluationofobservationalmethods

shiftof thetechnicalmeasurelimitmightchangethe and specificity, whichcan supportconclusionson the

correspondence withobservations. In theQEC method, predictivevalidityof the method(75, 85-90, 138,

exactlimits between theobserved categories haveinten- 139). Outcomesused in theseriskstudieshavevaried

tionallybeen omitted in order to tool

improve usability fromdiscomfort and fatiguein laboratory settingsto

(47). Another possibleexplanation fordivergent results well-defined clinicaldiseases in prospective cohorts;

may be thatthe technical reference measures were col- thisvarietyin outcomealso hindersthecomparisons

lectedona continuous time-line, while the observations ofresultsfromdifferent studies,andthusobstructs the

weredoneusinglimited sampling atfixed-time intervals drawing of conclusions on the validity of risk limits

(14,30,41, 126). givenbyanyparticular method.

Differentmethods usedsimultaneously on thesame Intra-andinter-observer repeatabilitywerereported

object have given different results in several studies.If only for 7 and 17 methods,respectively. Theywere

oneofthemethods is knownorsuspected to givemore mostlyreported to be good or moderate. Generally the

accurateinformation thananother, itcanbe regarded as repeatability is better within observers than between

a validationreference, provided the two methods are them, as suggested forthosemethods wherebothsources

measuring thesamevariable.Still,manyofthesestudies of variancehad been studied.However,it shouldbe

havechosento comparemethods rather thanvalidating notedthatin mostcases inter-observer reliabilitywas

one using the other as a reference since noneof the assessedwithoutconsideration of theeffectsof intra-

methods has been shown to be systematically more observer variability.If thiseffectis notacknowledged,

accuratethantheothers(eg, comparisons between the estimatesof inter-observer variabilitywill be system-

strainindex,ACGIH HAL andOCRA). If the outputof aticallyinflated. The inter-observer reliabilityofmany

theassessment methodis a compound risk index (as in methods may,therefore, be betterthan what is reported

QEC, REBA,RULA,strain index,OCRA,NIOSH equa- inthestudies.

tion),itsconcurrentvalidity can,intheory, be estimated Repeatability is highlyrelatedto theuser skills,

on thebasis of technicalmeasurements of each indi- whichcan be enhancedwithappropriate training (4).

vidualitem.However, compound indicesandsumscores In sometrials,theobservers hadto improve theirskills

are sensitiveto theweightsgivento individualitems untila presetagreement was reached(ie,TRAC,PATH)

in thecalculationof theindexor score.For example, thisresultedin a good reliability ratingin ourevalua-

a laboratory simulation of lifting tasksshowedthatthe tion.For mostmethods, theliteraturedid notmention

valueof theNIOSH lifting indexwas highlysensitive thedurationof training neededto reacha satisfying

tothefrequency oflifting andthehorizontal locationof proficiency inusingthetool.

theload(107).

observational

Historically, methods havedeveloped

ofreferences

andselection

Identification

from thecommonexperience thatsomevisuallydetect-

able posturesand actionsare relatedto discomfort or Guidelines onhowtoconductsystematic reviews(140-

disorders inthemusculoskeletal system; a notionwhich 142) havestressed theimportance ofsystematic search

has laterbeendemonstrated in numerous experimental strategiesin electronicdatabases.Using thevarious

and epidemiologicalstudies.Theoreticalconstructs, combinationsof searchtermsset out earlierand a

combining thephysiological, epidemiological, andbio- manageablenumberof references, we wereunableto

mechanicalknowledge,have shownthatmechanical identifyall of therelevantmethodsin ourpreliminary

forcesactingonthetissuesis probably themostimpor- searches.Therefore, we continued searchingusingthe

tantfactorin explaininghow MSD can develop.In namesof theidentified methodsand theoptionof an

addition tothemagnitude oftheexposures, timeaspects automaticsearchfor"relatedstudies",followedby a

relatedto physiologicalresponsesare of importance visualscreening oftheresulting listsofpublications.We

(133-137). Therefore an observationmethodwitha werealso awarethatpractitioners mayuse methods that

good content validity(1,2) formechanicalexposures havenotnecessarily beensubjectedto scientific testing

shouldincludethe frequency and durationof items and,therefore, willnotbe foundindatabasescompiling

quantifying exposures - likeexternal forcesorpostures scientificreports.Consequently, we supplemented our

- inaddition totheirmagnitude. searcheswithinternet searching once we had identified

In our evaluation,we addressedwhetherfindings thenamesofthemethods. In addition topapersinEng-

usinga particular observation methodhadbeenassoci- in

lish,we acceptedreports German, Italian,and

French,

ated withMSD (the so-called"predictivevalidity"). Scandinavian languages.Through thisextensivesearch,

Even thoughassessmentsof several methodshave we haveprobably identifiedmostobservational methods

correlated withtheoccurrence of MSD in cross-sec- usedfortheassessment ofbiomechanical exposures.We

tionalsettings,onlya fewcohortstudieshaveanalyzed acknowledge the existenceof additional methods that

possibleassociationsusingtermssuch as sensitivity werenotaccessibletous duetotheirlimited availability

16 Scand J WorkEnvironHealth2010, vol 36, no 1

This content downloaded from 87.7.162.2 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 15:38:13 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Takala et al

(eg,commercial methods oradditional academicstudies didnotmakea formalassessment on thequalityofthe

notlistedin theinternet Previous

databases). reviews assessments ofagreement, butconsidered thequalityas

havealsomentioned inconference

references booksthat sufficient ifno obvioussourceoferror was detected. We