Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

UNEP POPS POPRC12CO SUBM Dicofol IPEN 10 20170512.en

Загружено:

Miks SolonОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

UNEP POPS POPRC12CO SUBM Dicofol IPEN 10 20170512.en

Загружено:

Miks SolonАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

doi:10.3763/ijas.2009.

0431

Health and environmental impacts of pesticide use practices:

a case study of farmers in Ekiti State, Nigeria

Oluwafemi Oluwole1,2 and Robert A. Cheke1,*

1

Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich at Medway, Central Avenue, Chatham Maritime,

Kent ME4 4TB, UK; and 2Present address: c/o Adekunle Odola, U.I. PO Box 22203, University of Ibadan,

Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria

Commonly used pesticides and handling practices which might expose farmers and their environment to

chemical hazards were investigated in the Irepodun/Ifelodun local government area of Ekiti State,

Nigeria. Direct field observations and answers to a structured questionnaire from a random sample of

150 farming households showed that commonly used pesticides comprised herbicides (48.3 per

cent), fungicides (28.2 per cent) and insecticides (23.5 per cent). Of these, 86.7 per cent are classified

as ‘highly’ hazardous by the World Health Organization (WHO) and have been banned or restricted in

many developed countries. Nearly all of the farmers (94.7 per cent) had received no formal training in

safe pesticide use and mixed different products. Farmers suffered from discomforts ranging from eye

irritation (91.3 per cent), skin problems (87.3 per cent), nausea (86.0 per cent), headache (83.3 per

cent) and vomiting (58.0 per cent). More than half of the pesticide applicators (61.3 per cent) sprayed

pesticides near water bodies. Only a few farmers reported decreasing trends in numbers of beneficial

insects (27.3 per cent) and other animals (29.3 per cent). The results showed that the awareness of

farmers and authorities needs to be raised regarding the use of protective equipment and correct

procedures when handling pesticides and, also, that there should be stricter enforcement of existing

pesticide regulation and monitoring policies to minimize the threats that the farmers’ current practices

pose to their health and to the environment.

Keywords: agriculture, environment, health, Nigeria, pesticides, safety

Introduction people have suffered severe acute pesticide poison-

ings (WHO, 1992; Larson, 2003), few studies have

Crop damage from pest infestations often results in been conducted on the subject to assess its sustain-

serious consequences, warranting the need to use pes- ability. Misuse and abuse of pesticides lead to both

ticides. However despite their benefits, pesticides direct and indirect environmental effects. The indir-

pose potential hazards to human health and the ect effects include negative impacts on human

environment when inappropriately handled (WHO, health, degradation of the environment, loss of biodi-

1990; Kishi, 2005). Despite increasing concern versity and irreversible changes to ecosystems (Ajayi,

about overuse and misuse of pesticides in developing 2000; Gürler et al., 2006; Jänsch et al., 2006), yet

countries (Tijani, 2006a), where over 3 million pesticides have been distributed throughout the

world so that they occur everywhere (Carson,

1962; Kamrin, 1997; Balaram, 2003). In humans,

*Corresponding author. Email: r.a.cheke@greenwich.ac.uk pesticides can be absorbed through the skin and

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY 7(3) 2009, PAGES 153–163

# 2009 Earthscan. ISSN: 1473-5903 (print), 1747-762X (online). www.earthscanjournals.com

154 O. OLUWOLE AND R.A. CHEKE

lungs and ingested in drinking water with adverse practices in the Irepodun/Ifelodun Local Govern-

consequences such as headaches, dizziness, convul- ment Area of Ekiti State, Nigeria. To achieve this,

sions, epilepsy, stroke, respiratory disorders, leukae- it was necessary to do the following:

mia, stomach and intestinal upset, spasm, heart

† Assess the different types of chemical pesticides

attacks, cancer, brain and liver tumours, and death

commonly used by the farmers;

(Alavanja et al., 2004; Yousaf et al., 2004; Tijani,

2006a; Shou-zhen, 2007; Kedia & Palis, 2008). † Assess the farmers’ perceptions of pesticide safety

In Nigeria, pesticides have proven to be indispen- labels, pesticide handling and field spraying prac-

sable tools in combating damage from pests and tices which might expose them to chemical

ensuring sustainable food production with hazards;

improved yield and greater availability of food all

† Assess the impacts of pesticides on farmers’

year round. For example, without the use of pesti-

health as reported by symptoms of illness;

cides in rice and cocoa production, about 45 per

cent of total production would be lost to pests and † Assess the farmers’ perceptions of possible

diseases (Tijani, 2006b). changes in biodiversity as a result of pesticide

However, increasing intensification of agricul- application by the farmers.

tural production in Nigeria has led to increased

The study was conducted in a forest zone noted for its

health and environmental concerns and the pro-

production of rice, cocoa, fruits and vegetables so it is

ductivity-enhancing effects of pesticides have been

not necessarily representative of the country as a

overvalued, as studies rarely take into consideration

whole since different practices may pertain in

their effects on the environment and on farmers’

savanna or upland zones. Nevertheless, and in the

health (Osibanjo, 2001; Konya, 2005; Adeniran

absence of evidence confirming that pesticide use

et al., 2006). Poorly regulated and unsafe use of

practices are any better elsewhere in the country,

pesticides coupled with the absence of adequate

our results provide useful information about pesticide

education has led to increasing pesticide impact

practices of farmers and other users of pesticides and

on public health and, in particular, on the health

their resulting consequences, for consideration by the

of farm workers (Tijani, 2006a). At the same

Nigerian government and policy makers. Means to

time, the indiscriminate use of toxic substances

ameliorate the health hazards faced by farmers due

has become a matter of national concern in

to misuse and abuse of pesticides are needed. It is

Nigeria following revelations about high levels of

also important for farmers in Nigeria to learn the

DDT in the environment and human breast milk

need to practise sustainable agriculture in a way

(Osibanjo, 2002).

that does not affect them and their environment.

In Nigeria, as in many other developing

countries, the largest proportions of chemical pesti-

cides are used by resource-poor rural farmers. Materials and methods

Methods for safe storage, handling and application

of pesticides are not widely used in most developing The study was conducted in Ekiti State in southwes-

countries (Pingali & Rola, 1993; Crissman et al., tern Nigeria, which is the largest rice-producing state

1994; Sibanda et al., 2000; Tettey, 2001; Addo in the country. Ekiti State is located 78250 –88200 N,

et al., 2002; Dinham, 2003), particularly in Africa 58000 –68000 E in the rainforest belt of southwestern

(Williamson et al., 2008), and we found that this Nigeria (EKSG, 1997; Kayode, 1999, 2000) and lies

was also the case among rural farmers in Ekiti south of Kwara and Kogi States, east of Osun State

State, Nigeria, as reported below, and warrants and bounded by Ondo State in the east and south

urgent attention. It is likely that pesticide use and (EKSG, 1997). Interviews with the farmers were

pesticide-induced side effects will continue to carried out in the Yoruba-speaking agricultural com-

increase in Nigeria where environmental legislation munity of the Irepodun/Ifelodun Local Government

is either non-existent or ineffective (Osibanjo, Area because of the prominent position it occupies

2001) and such use is thus unsustainable. in the production of rice and because it is where cash

This study was an attempt to identify the health crops (cocoa, kola nut), horticultural crops (veg-

and environmental hazards posed by pesticide use etables, fruits) and cowpea are mostly cultivated

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY 7(3) 2009, PAGES 153–163

HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF PESTICIDE USE PRACTICES 155

using farm inputs, particularly pesticides. The study (3) Human and environmental impacts: this

area was selected based on crops grown and heavy section was used to obtain information about

pesticide usage. Rice is one of the crops that requires the effects of pesticide exposure, e.g. the symp-

application of pesticides, especially at the seedling toms of illness commonly encountered during

stage to control weeds for improved yields. Cocoa or after pesticide spraying operations and chan-

plants require frequent application of pesticides to ging trends in biodiversity, e.g. changes in

prevent pest infestations and fungal infections. weeds, birds and insects (whether increasing,

Farmers in Irepodun/Ifelodun grow these crops in decreasing or constant). For the human health

large quantities; thus, the introduction and increasing effects, only acute symptoms that appeared

use of pesticides in the study area is linked to the within 48 hours of pesticide sprays were

farmers’ efforts to increase crop production and yields. considered. Long-term and chronic health

The study used questionnaire interviews with impairments were not considered due to meth-

farmers who used pesticides as one of their major odological difficulties.

farm inputs. The Local Government Area consists

of 10 communities: Afao Ekiti, Are Ekiti, Awo Each community surveyed in the study area was

Ekiti, Esure Ekiti, Eyio Ekiti, Igbemo Ekiti, Igede divided into four ‘quarters’ (a quarter is an adminis-

Ekiti, Iropora Ekiti, Iworoko Ekiti and Iyin Ekiti. trative unit within each community, governed by a

However, the communities where 150 farmers chief) except Eyio Ekiti which was divided into

were selected at random for the study were Igede three quarters, because it has a lower population

Ekiti, Igbemo Ekiti, Iyin Ekiti and Eyio Ekiti. The compared to Igbemo, Igede and Iyin Ekiti. In all,

success of the survey relied on the willingness of farmers in 15 quarters were surveyed. A random

the farmers to participate in the study, facilitated sample of 10 households per quarter was taken,

by pre-survey meetings with group leaders of the providing a sample of 150 farmer households by

Farmer’s Cooperative Union in each community. identifying 50 households in each quarter whose

A structured questionnaire was designed to major occupation was predominantly agriculture

collect information on commonly used pesticides and who were known to have used pesticides con-

and practices, risk perception, attitudes to pesticide tinuously for more than a decade and who were

labels, precautions, the farmer’s source of infor- still using them. This was achieved through the

mation about pesticides, and signs and symptoms permission of the community leader in each

of illness related to pesticide exposure. Data were community and the 50 farmer households for each

collected through a field survey by face-to-face quarter were identified with the help of the leader

interviews with farmers conducted at dusk when of the Farmers’ Cooperative Union in each commu-

the farmers had finished the day’s tasks. The ques- nity. Second, the 50 identified households were

tionnaire was designed in English but the interviews numbered on 50 pieces of paper from which 10

were conducted in the local language, Yoruba. numbers were randomly drawn to represent the

The interview questionnaire was designed under 10 households to be interviewed. Similar methods

the following headings: have been used elsewhere to select villages and

households for study, e.g. by Ajayi (2005).

(1) General system and practices: this was used to To avoid bias in the type of questions that were

obtain information on farmers’ biodata such asked, the questionnaire was designed to avoid

as sex, age, household size, level of education, leading questions. For example, to find out if the

marital status and location of farm. farmers store pesticides in a safe place before and

(2) Pesticide use and practices: this section was used after application, the question, ‘Where do you store

to obtain data about the types of pesticides used, your pesticides?’ was asked. In the same way,

attitudes to pesticide labels, applicators and on-farm exposure to pesticides was identified by

sources of pesticides commonly used by the asking the farmers ‘how do you apply your

farmers, protective materials, pesticide use prac- pesticides?’ and the method(s) mentioned by the

tices (e.g. mixture and quantities, application farmers were recorded. Each interview took about

methods and disposal of empty pesticide con- 15–25 minutes to complete and all were conducted

tainers) and pesticide storage methods. during March 2008.

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY 7(3) 2009, PAGES 153–163

156 O. OLUWOLE AND R.A. CHEKE

Results and discussion pesticides have been banned, severely restricted or

deregistered in some countries because of their

Household characteristics, education known hazardous effects on humans and the

and literacy environment. Also, 131 farmer respondents used

Ridomil plus (Mancozeb). This pesticide has no

The majority (93.3 per cent) of the farmers inter- known WHO hazard classification class but it has

viewed were male. The mean and modal ages for been reported to cause cancer and disrupt the endo-

farmers were 55 and 63 years, respectively. Male- crine system by the US Environmental Protection

headed households made up 83.3 per cent of the Agency and the World Wildlife Fund respectively

total respondents. Of the 150 farmers interviewed, (PAN, 2009). Therefore, it is declared ‘not for

only 26 per cent were able to read and write and sale’ but to be distributed by agricultural agencies

were likely to understand instructions on pesticide only. However, the pesticide was freely available

containers’ labels, whereas 12.7 per cent had in the open markets for the farmers to purchase.

received no formal education (Figure 1). The This confirms that the pesticides regulation policy

majority of the farmers who were either illiterate in the state is poorly implemented, as reported for

or with only primary school education depended Nigeria as a whole by Osibanjo (2001).

on explanations from other farmers and/or pesti-

cide suppliers. Only 27.3 per cent of the farmers

claimed that they always read labels on pesticide Availability and sources of pesticides

containers while the remainder said that they

never read labels before and after buying pesticides. Farmers normally purchased pesticides in small

quantities in local shops which were within easy

reach of their homes. Of the 150 farmers inter-

Types of pesticides commonly used

viewed, only 16.7 per cent obtained instructions

by farmers

from agricultural extension agents in the area;

Of different pesticide formulation types used by 46 per cent depended on their long-term personal

farmers in the area, most were herbicides (48.3 experience and 19 per cent consulted other

per cent), especially Paraquat, commonly used farmers. However, such knowledge may be dis-

by 98.7 per cent of the farmers (Table 1), because torted if it is received from people other than experi-

weeds were the most serious threat to crop pro- enced extension agents (Tijani, 2006a). The

duction. Herbicides were followed in rank of primary sources of pesticides were local commodity

importance by fungicides (28.2 per cent) and insec- shops, followed by private farmers’ shops, with

ticides (23.5 per cent). agricultural suppliers playing a minor role

Lindane and monocrotophos, which were used (Figure 2). The reason for this was that pesticides

by 34 and 117 farmer respondents, respectively, in the local shops were cheaper, readily available

belong to a group of pesticides popularly known (as the pesticides were sold in the farming commu-

as the ‘dirty dozen’ (PAN, 1993; 2009). These nities) and with no limitations to their usage by

Figure 1 Education level of the heads of the households surveyed in the study area

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY 7(3) 2009, PAGES 153–163

HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF PESTICIDE USE PRACTICES 157

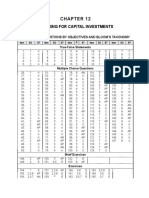

Table 1 Pesticides commonly used by the farmers; numbers and percentages (in parentheses) of farmers reporting use of

each category

Trade name Common name WHO Pesticide No. of farmers (%)

class* type

2,4-D amine 2,4-D II Herbicide 40 (26.7)

Apron star Metalaxy þ Difenoconazole þ III Insecticide 71 (47.3)

Thiamethoxam

AtraForce Atrazine III Herbicide 97 (64.7)

Copper Pentahydrate II Fungicide 136 (90.7)

sulphate

Gammalin 20 Lindane II Insecticide 34 (22.7)

Gramoxone Paraquat II Herbicide 148 (98.7)

Nuvacron Monocrotophos Ib Insecticide 117 (78.0)

Primextra Metolachlor Ib Herbicide 130 (86.7)

Ridomil plus Mancozeb þ Metalaxyl NK Fungicide 131 (87.3)

Roundup Glyphosate U Herbicide 42 (28.0)

*Ib ¼ highly hazardous; II ¼ moderately hazardous; III ¼ slightly hazardous; U ¼ unlikely to present acute hazard in

normal use; NK ¼ not known (WHO, 2004; PAN, 2009).

the farmers. All the farmers interviewed considered Pesticide handling practices: preparing

price and efficacy of the pesticides first before and applying pesticide formulations

buying them. Also, 88 per cent considered avail-

In all cases, farmers prepared pesticides in their

ability and 72.7 per cent took neighbours’

fields before application. However, 79.3 per cent

recommendations into account. Farmers’ consider-

of the farmers interviewed used their domestic

ation of prices and the efficacy of pesticides as

buckets or containers to prepare pesticides before

reported in this study was also confirmed by

pouring them into the spraying tanks for appli-

Williamson et al. (2008) as a regular practice

cation. Of the 150 households interviewed,

among farmers in developing countries.

Figure 2 Farmers’ major suppliers of pesticides in the study area

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY 7(3) 2009, PAGES 153–163

158 O. OLUWOLE AND R.A. CHEKE

90.7 per cent reported that the fathers in the house- bringing the chemical solution closer to the applica-

holds applied the pesticides, indicating that women tors and increasing their vulnerability to pesticide

were more involved in other farming duties such as exposure (Ajayi & Akinnifesi, 2007).

weeding, harvesting and planting and, as a result, It is always necessary for pesticide applicators to

could be prone to various other forms of pesticide recognize the consequence of spraying against the

exposure (Mancini et al., 2005). Children were wind (under windy conditions) and to take ade-

also involved in these activities and might also quate precautionary measures, but few of the

assist in fetching water to prepare pesticide sol- farmers (18 per cent) observed the wind direction

utions or help in purchasing pesticides from local when spraying chemical pesticides. One of the

shops. This form of division of labour could reasons reported for this was that such an instruc-

expose the whole community to pesticide hazards. tion was not on the label and was not thought

to be necessary. In an attempt to reduce quantities

of pesticides used, farmers who observed wind

Pesticide handling practices: protective direction always sprayed when the wind speed

equipment and precautions against was high because they believed that high wind

exposure speed would help to spread the chemical solution

Handling of concentrated pesticide and application to wider areas of the field. However, this

of diluted formulations require that the applicators practice has been reported to increase the risk of

use appropriate personal protection equipment. A exposure of applicators to pesticides (Ajayi &

majority (90 per cent) of the farmer respondents Akinnifesi, 2007).

admitted that they did not take any personal protec-

tive measures while handling pesticides. Farmers

Pesticide cocktails

cited economic reasons, inconveniences involved,

lack of available protective equipment and lack of Many farmers misused chemicals by making cock-

information as major reasons for not using protec- tails of different kinds of pesticides before spraying

tive equipment. A total of 135 respondents (Table 2). Pesticide instruction labels do not usually

applied pesticides themselves, of whom 120 (88.9 cover mixtures of three or more active ingredients

per cent) did not use any form of protective equip- and do not give information on their compatibility

ment except their normal clothes and only 15 (Ngowi et al., 2007). Unfortunately, nearly all of

(11.1 per cent) wore spraying boots when mixing the farmers interviewed (94.7 per cent) mixed two

or applying pesticides. Normal clothes used by the or more pesticides before application, arguing that

farmers were made of either cotton, synthetic mixtures increased the efficacy of the pesticide sol-

fabric or wool and could not always be effective ution and so ensured effective control of the target

in protecting them against pesticide exposure pest. They also believed that mixing different pesti-

during spraying. Such materials may absorb pesti- cides saved time because they could apply more

cide solutions during spraying operations, thereby than one pesticide in a single spraying operation.

Table 2 Pesticides routinely mixed by farmers in the study area; numbers and percentages (in parentheses) of farmers

reporting use of each combination

Pesticide combination Types of pesticides No. of farmers (%)

Atrazine þ Gramoxone Two herbicides 38 (25.3)

Atrazine þ Primextra Two herbicides 34 (22.7)

Copper sulphate þ Ridomil þ lime Two fungicides þ one insecticide 130 (86.7)

Gramoxone þ Primextra Two herbicides 104 (69.3)

Roundup þ Primextra Two herbicides 9 (6.0)

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY 7(3) 2009, PAGES 153–163

HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF PESTICIDE USE PRACTICES 159

However, there were no specific instructions either containers and re-used them for storing water and

on the pesticide labels or from extension agents food. The storing of foods in pesticide containers,

regarding these mixtures for this purpose. which retain traces of the pesticides even after

washing, poses serious health hazards to farmers

and their families (Dinham, 1993; Tijani, 2006a). If

Storage of pesticides

they did not use the containers for food or water

The farmers stored chemical pesticides for agricul- storage, some disposed of them by selling or burying

tural use within their homes and rooms and did them but a majority (90.7 per cent) left the containers

not have special locations for storing them. A in the field after use (Figure 3), thereby posing serious

majority (98 per cent) of the farmers kept pesticides risks to nearby streams, animal food and child health

either in their bedrooms, their sitting rooms or (Ajayi & Akinnifesi, 2007).

in stores together with food, some because they

feared that the chemicals would be stolen if they

Health impairment: farmers’ reports of

were kept elsewhere.

symptoms of pesticide poisoning

The periods of pesticide storage reported varied

from a few months to more than a year, in cases Medical examinations of a sample of farmers was

where the pesticides were not used up during a beyond the scope of this study, which relied solely

season and were kept for the following season. on self-assessed/reported health effects of pesticides

Storing pesticides in places other than stores desig- by asking the farmers if they experienced any

nated for this purpose exposes users and non-users, health weakness (discomfort) in their day-to-day

especially children, to hazards (Tijani, 2006a). handling of chemical pesticides. A majority (91.3

Stored pesticides may expire or become obsolete per cent) responded that they or someone in their

and no longer suitable for use. Of the farmers inter- family had suffered from pesticide-related health

viewed, 80 per cent indicated that they always symptoms during or after application of pesticides.

mixed expired pesticides with new ones and contin- This is usually the situation in most developing

ued to use them, stating that newer, less toxic, pes- countries where farmers sometimes report ill health

ticide chemical formulations were often more and cases of hospitalization following pesticide

expensive than older, more toxic, products. application (Wilson & Tisdell, 2001; Atreya, 2005;

Rao et al., 2005; Williamson et al., 2008). The inter-

viewed farmers reported multiple health effects such

Pesticide container disposal

as nausea, headache, vomiting, eye irritation and

The majority of the pesticides used by the farmers skin problems, with farmers reporting a minimum

were packaged in bags and plastic containers, which of two and a maximum of five symptoms of illness

should be properly disposed of after use. Regrettably, (Figure 4). Most (94.7 per cent) of the farmers experi-

most farmers washed and rinsed plastic pesticide enced these symptoms during preparation/mixing

Figure 3 Pesticide container disposal methods in the study area

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY 7(3) 2009, PAGES 153–163

160 O. OLUWOLE AND R.A. CHEKE

Figure 4 Health impairments resulting from pesticide use by farmers in the study area

and during application/spraying of the pesticides, yet used water from them to mix pesticides in the field

88.9 per cent openly admitted that they did not take and wash spraying tanks after spraying operations.

any protective measures when handling pesticides. This practice may increase the vulnerability of

The farmers considered these symptoms as the farmers to pesticide poisoning (because the

common phenomena and had attributed them to farmers sometimes depended on these waters for

fatigue and tiredness after working in the field; their drinking water supplies), as well as affecting

however, upon asking them whether they believed the quality of the water and having negative

that pesticides could be dangerous to their health impacts on aquatic organisms such as snails and

and the environment, all the respondents believed frogs. Only 19.3 per cent of the respondents

this to be true. This indicated that the farmers were reported changes in the aquatic life in the study

well aware of possible health effects of pesticides, area following pesticide application. Roundup

but their actions implied that they did not adjust (Glyphosate) is used by 28 per cent of the farmer

their practices accordingly. This is also a common respondents: at 3.7 mg a.i./l, this pesticide can

practice among farmers in Benin, Ethiopia, Ghana exterminate populations of many frog species and

and Senegal (Williamson et al., 2008). other aquatic organisms (Relyea, 2005). However,

Continuous exposure to pesticides can lead to an with 46 per cent of the respondents depending on

array of health effects, depending on the pesticide’s their long-term personal experience rather than

toxicity and the dose absorbed by the body (Adams, paying attention to the concentration rate on pesti-

1995; Coble et al., 2005; Ritter & Arbuckle, 2007). cide labels, continuous use of this pesticide in the

Thus, the farmers could have been suffering from study area in an unsafe manner is likely to pose a

chronic diseases associated with pesticide exposure greater threat to these organisms.

of which they were unaware, such as cancer, brain dis- The study further revealed that beneficial insects,

orders or depression, hormone and reproductive birds and other animals may be decreasing in the

system disruption. However, a detailed medical study area. Upon asking the farmers whether they

examination of a sample of farmers to ascertain had noticed any immediate changes in the number

such health effects was beyond the scope of this study. of insects and animals in the area over the last two

years following pesticide application, 27.3 and

29.3 per cent of the farmers reported that they had

Pesticides and biodiversity in the

noticed a decrease in the numbers of beneficial

study area

insects and of other animals, respectively (Figure 5),

Pesticides are harmful to fish, water bodies and supported by statements about unusual decreases

animals (Ajayi & Akinnifesi, 2007). Ninety-two in the number of mammals and birds around

of the farmers interviewed (61.3 per cent) sprayed their farms. These declines may be attributable to

pesticides near water bodies. Also, they always accidental contacts by the animals with pesticides

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY 7(3) 2009, PAGES 153–163

HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF PESTICIDE USE PRACTICES 161

Figure 5 Changes in biodiversity as reported by farmers in the study area

misused by the farmers (Pain et al., 2004). Also, the these pesticides due to a failure of the Nigerian pes-

farmers reported infrequent visits to their cowpea ticide regulatory authority to monitor and enforce

farms by honeybees and a scarcity of honeycombs, national legislation.

which used to be abundant in the area. This could Efforts to train farmers in the appropriate use of

have been as a result of the use of a neurotoxic insec- pesticides are needed. However, this alone cannot

ticide (Monocrotophos) and copper sulphate (Pen- guarantee proper protection of farmers from

tahydrate) on their farms which have been health hazards because bad practices that expose

documented to be highly toxic to birds and bees; farmers to inherent dangers of pesticides are

also the use of Thiamethoxam is known to alter not attributable to lack of information alone,

bees’ foraging behaviour (USNLM, 1995; Guez, but also to other factors such as costs and accessibil-

2001; PAN, 2009). ity of protective materials (Ajayi & Akinnifesi,

2007). The following mitigating measures are

recommended:

Summary and conclusions

† Farmers need regular training to encourage

The study provided information about the cat-

appropriate practices for safe use and handling

egories of pesticide used, trends in pesticide uses,

of chemicals and pesticides by educating them

health symptoms and environmental effects of

about the risks involved in the misuse and

pesticide use practised by the farming community

abuse of these poisonous materials. In addition,

of Ekiti State, Nigeria. Results from a survey of

training in integrated pest management (IPM)

150 farmers revealed much misuse and abuse of

methods, which could reduce the quantity of

pesticides, which may have contributed to their

pesticides used and hence reduce potential

health problems and contaminated their environ-

exposures, is recommended.

ment. Farmers reported suffering from discomforts

ranging from skin irritation, headache, vomiting, † Local suppliers are the major distributors of pes-

eye irritation and nausea after using pesticides. ticides to the farmers. However, they lack train-

This is attributed to the low level of education of ing on usage and storage of pesticides at the

users coupled with a lack of formal training in shop level, information on pesticide safe hand-

pesticide use and poor extension services. Some of ling practices and correct advice to farmers.

the pesticides used by the farmers are classified Regulatory and adequate monitoring policies

as ‘highly’ or ‘moderately’ hazardous by WHO that can provide adequate extension and advi-

and have been banned, severely restricted or dereg- sory services to pesticide distributors on the

istered in the European Union and in Nigeria range of pesticide products available and their

(PANN, 2007; OCA, 2008; PAN, 2009). uses and handling are recommended. This may

However, farmers in the study area are still using improve the quality of pesticide and customer

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY 7(3) 2009, PAGES 153–163

162 O. OLUWOLE AND R.A. CHEKE

services that are available to the farmers in the International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 3,

community. 154– 166.

Ajayi, O.C. and Akinnifesi, F.K. (2007) Farmers’ under-

† Government should intensify efforts aimed at standing of pesticide safety labels and field spraying

registering and controlling distribution of pesti- practices; a case study of cotton farmers in northern

Côte d’Ivoire. Scientific Research and Essays 2,

cides and banning hazardous ones. This could be

204– 210.

achieved through stricter enforcement of existing Alavanja, M.C.R., Hoppin, J.A. and Kamel, F. (2004)

regulation and monitoring policies. Also, govern- Health effects of chronic pesticide exposure: cancer

ment should make newer, less toxic chemical pes- and neurotoxicity. Annual Review of Public Health

ticides more readily available to the farmers in 25, 155 –197.

Atreya, K. (2005) Health costs of pesticide use in a veg-

ready-to-use packages. Finally, pesticide manu-

etable growing area, central mid-hills, Nepal. Himala-

facturers should be instructed and compelled to yan Journal of Sciences 3 (5), 81–84.

exhibit pesticide instructions and warning labels Balaram, P. (2003) Pesticides in the environment. Current

in the language commonly understood by the Science 85, 561 –562.

farmers and other end users, and also to package Carson, R.L. (1962) Silent Spring. Boston, MA:

Houghton Mifflin.

products in containers that are not attractive for

Coble, J., Arbuckle, T., Lee, W., Alavanja, M. and

subsequent re-use according to the International Dosemeci, M. (2005) The validation of a pesticide

Code of Conduct on the Distribution and Use of exposure algorithm using biological monitoring

Pesticides. results. Journal of Occupational and Environmental

Hygiene 2, 194–201.

Crissman, C.C., Cole, D.C. and Carpio, F. (1994) Pesti-

Acknowledgements cide use and farm workers’ health in Ecuadorian

potato production. American Journal of Agricultural

Oluwafemi Oluwole is grateful to the Association Economics 76, 593–597.

Dinham, B. (1993) Pesticide Hazard: A Global Health

of Commonwealth Universities for a shared scho- and Environmental Audit. London: Zed Books.

larship scheme grant that allowed him to conduct Dinham, B. (2003) Growing vegetables in developing

this study as part of an MSc programme at the countries for local urban populations and export

University of Greenwich. Adekunle Odola of the market: problems confronting small-scale producers.

University of Ibadan is thanked for assistance with Pest Management Science 59, 572–582.

EKSG (Ekiti State Government) (1997) First Anniversary

the questionnaire surveys and Colin D. Tingle for Celebration of Ekiti State. Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria: Govern-

advice on their design. ment Press.

Guez, D. (2001) Contrasting effects of Imidacloprid on

habituation in 7 and 8 days-old honeybees. Neurobiol-

References ogy of Learning and Memory 76, 183–191.

Gürler, A.Z., Erdal, G. and Erdal, H. (2006) The effects

Adams, R.W. (1995) Handbook for Pesticide of agricultural development on ecosystem and the

Applicators and Dispensers, 5th edn. Victoria, BC: sustainability of development. Journal of Agronomy

Environment. 5, 293– 298.

Addo, S., Birkinshaw, L.A. and Hodges, R.J. (2002) Ten Jänsch, S., Frampton, G.K., Römbke, J., Van den Brink,

years after the arrival of Larger Grain Borer (Proste- P.J. and Scott-Fordsmand, J.J. (2006) Effects of pesti-

phanus truncatus): farmers’ responses and adoption cides on soil invertebrates in model ecosystem and

of IPM strategies. International Journal of Pest Man- field studies: a review and comparison with laboratory

agement 48, 315–325. toxicity data. Environmental Toxicology and Chem-

Adeniran, O.Y., Fafunso, M.A., Adeyemi, O., Lawal, istry 25, 2490– 2501.

A.O., Ologundudu, A. and Omonkhua, A.A. (2006) Kamrin, M.A. (1997) Pesticide Profiles: Toxicity,

Biochemical effects of pesticides on serum and urinolo- Environmental Impact and Fate. Boca Raton, FL:

gical system of rats. Journal of Applied Sciences 6, CRC Press.

668– 672. Kayode, J. (1999) Phytosociological investigation of

Ajayi, O.C. (2000) Pesticide use practices, productivity Compositae weeds in abandoned farmlands in Ekiti

and farmers’ health: the case of cotton– rice systems State, Nigeria. Compositae Newsletter 34, 62–68.

in Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa. Pesticide Policy Kayode, J. (2000) Population dynamics of Euphorbia het-

Project, No. 3. Hannover. erophylla (L.) after slash and burn agriculture in South-

Ajayi, O.C. (2005) User costs, biological capital and western Nigeria. Journal of Biological and Physical

the productivity of pesticides in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sciences 1, 30–33.

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY 7(3) 2009, PAGES 153–163

HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF PESTICIDE USE PRACTICES 163

Kedia, S.K. and Palis, F.G. (2008) Health effects of pesti- Rao, C.H.S., Venkateswarlu, V., Surender, T., Eddleston,

cide exposure among Filipino rice farmers. The Applied M. and Buckley, N.A. (2005) Pesticide poisoning in

Anthropologist 28, 40–59. South India – opportunities for prevention and

Kishi, M. (2005) The health impacts of pesticides: what improved medical management. Tropical Medicine

do we know? In: Pretty, J. (ed.) The Pesticide Detox: and International Health 10, 581– 588.

Towards a More Sustainable Agriculture (pp. Relyea, R.A. (2005) The lethal impacts of Roundup and

23– 38). London: Earthscan. predatory stress on six species of North American Tad-

Konya, R.S. (2005) The effects of environmental assaults poles. Archives of Environmental Contamination and

on human physiology (1). Nigerian Journal of Physio- Toxicology 48, 351– 357.

logical Sciences 20, 2–7. Ritter, L. and Arbuckle, E. (2007) Can exposure charac-

Larson, B. (2003) Hygiene and health in developing terization explain concurrence or discordance

countries: defining priorities through cost –benefit between toxicology and epidemiology? Toxicological

assessments. International Journal of Environment Sciences 97 (2), 241– 252.

Health Research 13, 37–46. Shou-zhen, X. (2007) Health effects of pesticides: a

Mancini, F., van Bruggen, A.H.C., Jiggins, J.L.S., review of epidemiologic research from the perspective

Ambatipudi, A.C. and Murphy, H. (2005) Acute of developing nations. American Journal of Medicine

pesticide poisoning among female and male cotton 12, 269 –279.

growers in India. International Journal of Occu- Sibanda, T., Dobson, H.M., Cooper, J.F., Manyanga-

pational and Environmental Health 11, 221– 232. rirwa, W. and Chiimba, W. (2000) Pest management

Ngowi, A.V.F., Mbise, T.J., Ijani, A.S.M., London, L. challenges for smallholder vegetable farmers in

and Ajayi, O.C. (2007) Smallholder vegetable farmers Zimbabwe. Crop Protection 19, 807 –815.

in Northern Tanzania: pesticides use practices, percep- Tettey, V. (2001) Assessment of the use of pesticides by

tions, cost and health effects. Crop Protection 26, cabbage growers in the Ga District of Ghana. Unpub-

1617 –1624. lished BSc thesis. Department of Home Science, Univer-

OCA (Organic Consumers Association) (2008) Thirty sity of Ghana, Legon.

agrochemicals banned in Nigeria after deaths. Van- Tijani, A.A. (2006a) Pesticide use and safety issues: the

guard Nigeria, May 14. On WWW at http://www. case of cocoa farmers in Ondo State, Nigeria. Journal

organicconsumers.org/articles/article_12416.cfm. of Human Ecology 19, 183 –190.

Osibanjo, O. (2001) Regionally based assessment of Tijani, A.A. (2006b) Economic benefits of fungicide use

persistent toxic substances. Report of first Regional among cocoa farmers in Osun and Ondo States of

Meeting, Ibadan, Nigeria, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. Journal of Social Sciences 12, 63–70.

24– 26 July. Sponsored by United Nations Environ- USNLM (US National Library of Medicine) (1995)

ment Programme. Hazardous Substance Databank (pp. 10–19).

Osibanjo, O. (2002) Organochlorine in Nigeria and Bethesda, MD: USNLM.

Africa. In: Fieldler, H. (ed.) The Handbook of Environ- Williamson, S., Ball, A. and Pretty, J. (2008) Trends

mental Chemistry, Vol. 3. Persistent Organic Pollutants in pesticide use and drivers for safer pest manage-

(pp. 321– 354). Heidelberg, Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ment in four African countries. Crop Protection 27,

Pain, D.J., Gaigi, R., Cunningham, A.A., Jones, A. and 1327 –1334.

Prakesh, V. (2004) Mortality of globally threatened Wilson, C. and Tisdell, C. (2001) Why farmers

sarus cranes (Grus antigon) from monocrotophos poi- continue to use pesticides despite environmental,

soning in India. Science of the Total Environment health and sustainability costs. Ecological Economics

326, 55–61. 39, 449 –462.

PAN (Pesticide Action Network) (1993) Demise of the WHO (1990) Public Health Impact of Pesticides Used

Dirty Dozen. San Francisco, CA: PAN. in Agriculture. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health

PAN (Pesticide Action Network) (2009) The List of Lists. Organization.

PAN briefing paper showing a catalogue of lists of pes- WHO (1992) The WHO Classification of pesticides by

ticides identifying those associated with particularly hazard and guidelines to classification, 1992–93.

harmful or environmental impacts, 3rd edn. Unpublished report no. WHO/PCS/92.14. Geneva,

PANN (Pesticide Action Network Nigeria) (2007) Stra- Switzerland: World Health Organization.

tegic Assessment of the Status of POPs Pesticides WHO (2004) WHO Recommended Classification of

Trading in South Western Nigeria. African Stockpile Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classification

Programme, October. 2004. Corrigenda published by 12 April 2005

Pingali, P.L. and Rola, A.C. (1993) Pesticides, rice pro- incorporated. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health

ductivity and health impacts in the Philippines. In: Organization.

Fateh, P. (ed.) Agricultural Policy and Sustainability: Yousaf, R., Cheema, M.A. and Anwar, S. (2004) Effects

Case Studies from India, Chile, the Philippines and of pesticide application on health of rural women

the United States (pp. 47–62). Washington, DC: involved in cotton picking. International Journal of

World Resources Institute. Agriculture and Biology 1, 220 –221.

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL SUSTAINABILITY 7(3) 2009, PAGES 153–163

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Wiley CPA Examination Review Password DownloadslideДокумент753 страницыWiley CPA Examination Review Password DownloadslideMelodyLongakitBacatan100% (7)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Trees For TappingДокумент2 страницыTrees For TappingLengyel DánielОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Nervine and Antispasmodic HerbsДокумент4 страницыNervine and Antispasmodic Herbsqueencel100% (1)

- Medicinal and Aromatic Crops PDFДокумент194 страницыMedicinal and Aromatic Crops PDFAshutosh LandeОценок пока нет

- Entrepreneurship and Small Business ManagementДокумент192 страницыEntrepreneurship and Small Business ManagementMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- Test Bank - Chapter14 Capital BudgetingДокумент35 страницTest Bank - Chapter14 Capital BudgetingAiko E. Lara100% (8)

- Living in The IT ERA PrelimsДокумент4 страницыLiving in The IT ERA PrelimsMiks Solon43% (7)

- Responsibility Accounting and Transfer PricingДокумент7 страницResponsibility Accounting and Transfer PricingRod Lester de Guzman100% (6)

- Monster Girl Doctor (Light Novel) Vol. 5 PDFДокумент148 страницMonster Girl Doctor (Light Novel) Vol. 5 PDFDanielHincapieZapataОценок пока нет

- Capital Budgeting FM2 AnswersДокумент17 страницCapital Budgeting FM2 AnswersMaria Anne Genette Bañez89% (28)

- ch12 MGT AdvisoryДокумент41 страницаch12 MGT AdvisoryHoney Grace AbasolaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 SADДокумент62 страницыChapter 1 SADXavier DominguezОценок пока нет

- R2 For PrintДокумент17 страницR2 For PrintIvan Bautista0% (1)

- DSWD PWDДокумент5 страницDSWD PWDFar GausОценок пока нет

- Universal Robina Corporation: A Financial AnalysisДокумент41 страницаUniversal Robina Corporation: A Financial AnalysisMaria Aleni95% (19)

- ReferencesДокумент1 страницаReferencesMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- Gender Based ViolenceДокумент2 страницыGender Based ViolenceMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- IVLE Notes On Earnings Per Share and BooДокумент7 страницIVLE Notes On Earnings Per Share and BooMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- What Mathematics Is ForДокумент3 страницыWhat Mathematics Is ForMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- PUBLICATIONДокумент29 страницPUBLICATIONMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- Solutions For Homework Accounting 311 CostДокумент128 страницSolutions For Homework Accounting 311 Costblack272727Оценок пока нет

- 02 Laurel The Trials of The Rizal BillДокумент7 страниц02 Laurel The Trials of The Rizal BillCzar Jesse Caluducan85% (13)

- Financial Statement Analysis ProjectДокумент3 страницыFinancial Statement Analysis ProjectRushikesh KothapalliОценок пока нет

- PresentationДокумент7 страницPresentationMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- MGMT 2 AutosavedДокумент13 страницMGMT 2 AutosavedMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- PresentationДокумент6 страницPresentationMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- PrivinhДокумент1 страницаPrivinhMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- Tax Case DigeztsДокумент23 страницыTax Case DigeztsJose Ramir LayeseОценок пока нет

- What Mathematics Is ForДокумент7 страницWhat Mathematics Is ForMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- Financial ManagementДокумент7 страницFinancial ManagementMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- Allowable Deductions For CorporationДокумент39 страницAllowable Deductions For CorporationMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- Capital BudgetingДокумент73 страницыCapital BudgetingMiks SolonОценок пока нет

- Accounting Chapter 3Документ62 страницыAccounting Chapter 3Chandler SchleifsОценок пока нет

- Accounting 203Документ16 страницAccounting 203King QasimОценок пока нет

- The Hardest Thing To See Is What Is in Front of Your Eyes.Документ52 страницыThe Hardest Thing To See Is What Is in Front of Your Eyes.Luisa SolОценок пока нет

- Herbal Anticancer DrugsДокумент25 страницHerbal Anticancer DrugsChandrika ChoudharyОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Aroma TerapiДокумент246 страницJurnal Aroma Terapidewi100% (1)

- Discovery Vitality HealthyFood CatalogДокумент66 страницDiscovery Vitality HealthyFood Catalogmoonlight_owletОценок пока нет

- Royal India MenuДокумент14 страницRoyal India MenuOzreniusОценок пока нет

- "THE VOICE" April 2021Документ44 страницы"THE VOICE" April 2021Anonymous SKP0jiK9Оценок пока нет

- pp1 004 4 eДокумент3 страницыpp1 004 4 eAlex PaicaОценок пока нет

- Paper 1 Biology STPMДокумент11 страницPaper 1 Biology STPMmiadiОценок пока нет

- Using Growing Degree Days To Predict Plant Stages: MT200103 AG 7/2001Документ8 страницUsing Growing Degree Days To Predict Plant Stages: MT200103 AG 7/2001RA TumacayОценок пока нет

- Farming Life Cycle StepsДокумент6 страницFarming Life Cycle StepsPurushothaman KОценок пока нет

- Solanum Nigrum (The Nightshade)Документ8 страницSolanum Nigrum (The Nightshade)Bushra FathimaОценок пока нет

- Neet Biology DPP (1-80)Документ77 страницNeet Biology DPP (1-80)Sruthika AОценок пока нет

- Formulation and Evaluation of Herbal Hair DyeДокумент9 страницFormulation and Evaluation of Herbal Hair DyeioginevraОценок пока нет

- Science - Grade Four Reviewer 1st - 3rd QuarterДокумент27 страницScience - Grade Four Reviewer 1st - 3rd QuarterAnthonetteОценок пока нет

- Phytochemical Screening and Antibacterial Activity of Leaf and Callus Extracts of Centella AsiaticaДокумент7 страницPhytochemical Screening and Antibacterial Activity of Leaf and Callus Extracts of Centella Asiaticasalsabila shintaОценок пока нет

- Fruit Produce Facts English: University of CaliforniaДокумент4 страницыFruit Produce Facts English: University of CaliforniagipsОценок пока нет

- HORT 200a.manus Outline - ZafraДокумент27 страницHORT 200a.manus Outline - ZafraShadd ZafraОценок пока нет

- Low Oxygen Stress in Plants Oxygen Sensing and Adaptive Responses To HypoxiaДокумент419 страницLow Oxygen Stress in Plants Oxygen Sensing and Adaptive Responses To HypoxiakamalОценок пока нет

- 1constraints Faced by Cashew FarmerДокумент62 страницы1constraints Faced by Cashew Farmerogundoro kehindeОценок пока нет

- Efficient Shoot Regeneration From Direct Apical Meristem Tissue To Produce Virus-Free Purple Passion Fruit PlantsДокумент5 страницEfficient Shoot Regeneration From Direct Apical Meristem Tissue To Produce Virus-Free Purple Passion Fruit Plantsamin67dОценок пока нет

- Gloriosa Superba - Useful Tropical PlantsДокумент1 страницаGloriosa Superba - Useful Tropical PlantsJohn PetroshikОценок пока нет

- Studiesontraditionalmedicinalplantsin Ambagiorgisareaof WogeraДокумент8 страницStudiesontraditionalmedicinalplantsin Ambagiorgisareaof WogerawagogОценок пока нет

- Performance Evaluation of Released Common Bean (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.) Varieties at Benishangul Gumuz Region, EthiopiaДокумент5 страницPerformance Evaluation of Released Common Bean (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.) Varieties at Benishangul Gumuz Region, EthiopiaPremier PublishersОценок пока нет

- Amaranthu and Minor Leafy Vege-MergedДокумент486 страницAmaranthu and Minor Leafy Vege-MergedTyagi AnkurОценок пока нет

- BrassicaceaeДокумент18 страницBrassicaceaeTimothy JohnsonОценок пока нет