Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

2002 Strategic Market Segments and Prospects of Short Sea Shipping in The Eastern M

Загружено:

ElisendaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

2002 Strategic Market Segments and Prospects of Short Sea Shipping in The Eastern M

Загружено:

ElisendaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

STRATEGIC MARKET SEGMENTS AND PROSPECTS OF SHORT SEA

SHIPPING IN THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN AND THE BLACK SEA

Dr Kapros Seraphim

Lecturer, University of the Aegean

Dr Panou Konstantinos

Researcher, National Technical University of Athens

1. INTRODUCTION

Short Sea Shipping (SSS) is maritime transport, which does not involve an

ocean crossing. The notion includes maritime transport along coastlines and

between ports of the continental European Union and its island possessions.

It covers the transport of goods both within an individual Member State and

between Member States. For a major part, concerning sea transport between

continental ports, SSS is considered as an alternative to land transport,

including a maritime leg in an integrated door-to-door chain. Thus, SSS meets

the wider concept of intermodality (COM 243/97), that figures among the main

policy targets of the European Union. The alleviation of external cost of road

transport is the driving force behind the policy objective for the promotion of

intermodal transport.

It is indisputable that SSS is an environmentally friendly, low cost and safe

means of transport compared with the land based alternatives, particularly

congested road transport. However, within Europe the SSS activity does not

seem to achieve an appropriate level of recognition or market share in the

overall transport network. As an industry it has grown considerably during the

1990s as available data indicates, with an estimated increase of 23% in tonne

kilometres between 1990 and 1997. This growth was somewhat lower than

that of road transport in the same period at 26% in tonne kilometres. It is not

surprising, therefore, that the Commission has taken up this problem,

adopting on 5 July 1997 a ‘Communication on Short Sea Shipping –

challenges for the future’ which examines how best to promote this means of

transport as a viable alternative to overland freight. A modal shift from road to

intermodal transport significantly influences the SSS opportunities and

practices.

The importance of SSS and seaport activities in the Eastern Mediterranean

and the Black Sea is gradually increasing. Geopolitics in the last decade

favour a multi-dimensional development in the region. New market prospects

arise since several of the adjacent countries are in the process of transition

from a planned economy to a market economy. In parallel, the on going

restructuring of the SSS market is accelerated by policy developments in both

the EU and the third countries.

The analysis of current situation of SSS market in the Eastern Mediterranean

and the Black Sea region faces a number of constraints:

© Association for European Transport 2002

• The Mediterranean SSS market consists of a number of heterogeneous

geographical areas, with different characteristics concerning the

various changes in process.

• It is not yet very well known which cargoes have the greatest potential

to be shifted from land to sea, either geographically or commodity-wise.

• It is too early to conclude on the market potential of fast ships in SSS.

• As far as actual traffic data is concerned, there are a large variety of

types of available information. The sources are diverse, some data is

not in the form needed, other data is not reliable, existing databases

are heterogeneous and a lot of other type of data simply does not exist.

• Among the problems in the available data, the lack of Origin-

Destination data for most of SSS traffic flows must be underlined. This

also concerns the "final" destination of goods in the hinterland. The

available data is limited to the form of "input-output" traffic of the

Mediterranean ports. Thus, a lot of problems arise in any scenario

elaboration, as far as the interface between SSS services and inland

transport flow patterns is concerned.

At the same time, the eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea region is a rapidly

changing environment, due to a number of important reasons:

• Recent research results demonstrated that a number of transport

quality variables influence (more or less, according to the market

segment to be analysed) the strategies of actors from supply side1, as

well as the modal choice of final customers2.

• Structural changes in the socio-economic and political situation of

Mediterranean countries, particularly in the eastern part of the region,

influence the configuration of traditional flow patterns.

• New logistical concepts are also changing the network organisation of

SSS actors.

• Technological developments, such as the new generation of fast

ferries, modifies the transport time values and creates a new

competition framework.

• European Transport Policy aspects (e.g. cabotage) are expected to

influence the traditional market structure.

Considering the aforementioned parameters, this paper presents two

objectives: a) it attempts to identify and analyse the structural changes and

major developments in the SSS market in the Eastern Mediterranean and the

Black Sea region and b) it tries to identify the relative weight of various criteria

in the decision-making process, that lead decision makers to use SSS instead

of a land based transport mode, and to provide decision patterns. Therefore, it

is obvious that the paper focuses on short sea transport between continental

ports. Transport between continent and islands is considered as a distinct

market segment called “captive” short sea.

To achieve the objectives of the paper, two parallel approaches are adopted:

1 IQ project, Deliverable 2, 4th Framework Programme, European Commission-Directorate General 7, 1998.

2 LOGIQ project, Deliverable 2, 4th Framework Programme, European Commission-Directorate General 7, 1999.

© Association for European Transport 2002

The analysis of SSS in the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea region is

based on available statistical sources and literature review. The analysis of

the decision-making process follows a disaggregate demand approach, on the

basis of a field survey. Detailed methodological aspects are presented in the

relevant section of the paper.

2. THE STRUCTURE OF THE MEDITERRANEAN SHORT SEA SHIPPING

MARKET

2.1. An overview of Mediterranean trade by sea

Two of the most appreciable market developments are the remarkable

expansion and the structural modification of European trade by sea. During

the second half of the 1980s, Western Europe presented a quite long

economic growth3. The economic expansion of the EU member states was

accompanied by a 4.8% annual trade growth. In addition, trade between

member states has grown remarkably faster than economic output. The result

of this process should be easily reflected on trade and traffic flows.

Proportionally, intra-EU trade represented 53% of the total EU trade at the

end of the 1970s, reached 55% in 1985 and topped 60% in 1990. In 1992, it

accounted for 62% of the total and for 13% of the EU GDP4.

This augmentation accelerated both in absolute and proportional terms, since

the relaunch of European integration. The interest in the completion of the

Single European Market (SEM) was followed by a progressive elimination of

non-tariff barriers advancing the unrestricted circulation of goods inside the

EU. Notable examples are the lessening of border controls and the mutual

recognition of technical regulations and standards. The exact magnitude of

the static and dynamic integration effects is not possible to determine, since

the rapid growth of the intra-EU trade is bound to be influenced by many

factors. Nonetheless, the stimulation of the cross-frontier flows previously

discouraged by non-tariff barriers and a national market attitude drove to a

sharp intra-EU trade expansion.

The intra-EU market growth has evident impact on the traffic growth in the

Mediterranean region. This uninterrupted traffic growth has been

accompanied by a steady increase (at around 5% per annum) of general

cargo and containerised commodities5. Overall, 15.2% of the total intra-EU

maritime flows represent intra-Mediterranean movements.

3

From 1985 to 1990 the economies of the 12 EU member states grew annually by a rate of 3:1 comparing to

averages of 2.5 and 1.4 for the periods 1974-79 and 1980-84 respectively (average annual percentage change of

real GDP at constant prices; based on 1985 price levels and exchange rates; Source: OECD, Basic Indicators,

Annual publication).

4

Sources: Eurostat, Basic Indicators; CEU, Panorama of EU Industry, annual publications.

5

While total traffic levels have risen, there has been little change in the basic trade patterns which sees

manufactured and consumer goods go southbound, and agricultural products and seafood northbound.

© Association for European Transport 2002

2.2. Network configuration and Short Sea Shipping market segmentation

The Mediterranean region presents great complexity and heterogeneity. There

are enormous differences in scale, development and trading relationships and

for most of the region development and cohesion are important issues. In

order to have a better understanding of this diversity, the short sea framework

should be systematically analysed. A rough division of the SSS market into

two quite distinct sub-segments is as follows6:

• Feeder operators inter-connect seaports on behalf of deepsea shipping

lines which need to re-position their containers. The feeder business

has grown during the last decades and have taken over the task to

serve Mediterranean ports. In general, they are not involved in

hinterland activities.

• Regional operators also labelled door-to-door operators serve

genuinely regional transport demand, e.g. between Northern Europe

and the Mediterranean. They are in direct competition to overland

transport modes such as road and rail and often organise the complete

transport chain including the land transport legs. It should be noted that

these intra-European shortsea voyages may be direct calls or may be

routed via transshipment hubs resulting in rather complex trip

schedules.

As deep-sea lines move steadily to larger vessels, deep-sea calls are limited

to one port in each trading area, hence, a strong intra-Mediterranean feeder

trade to and from these "hub" ports is being developed7.

The increase of the feeder activity contributed to a remarkable growth of

containers handled in Mediterranean ports. Unitised intra-Mediterranean traffic

in 1996 was twice as much as in 1990. Throughout the period between 1990

and 1995 container trade from Northern and outside Europe countries

increased by 4.4%, a substantial part of which arrived at a major

Mediterranean port (Algeciras, Gioia Tauro, Genoa, Barcelona, Piraeus,

Marsaxlokk, Damietta or Limassol) and then was transshipped to another port.

In general, the region’s ports have been lagging behind their northern

competitors in terms of investment, pricing efficient management, and

physical accessibility to large markets.

Feeder and Ro/Ro traffic being the most expanded market niches, the current

split between them is well in advance of feeder services for relatively long

distance voyages, and of Ro/Ro mainly for short distance coastal shipping.

Whilst it is recognised that volume growth in the trades is at a steady rate, it

remains impossible to gauge the amount of respective capacity. This is

because the hub and spoke operators, who account for around 33% of the

services on offer, have flexible allocations for these markets.

6

IQ project, Deliverable 2, "Short-Sea Shipping" - Report number 2.2.13, 4th Framework Programme, European

Commission-Directorate General 7, 1998.

7

The feeder market carries cargoes to the requirement of their customers, and also undertakes the carriage of

empty containers for deepsea lines where the trade is imbalanced and container repositioning necessary.

© Association for European Transport 2002

The Mediterranean Ro/Ro services market presents shares of about 50 % for

each of the western and eastern part of the Sea. Because of the long coastal

lines of the countries in the Western Mediterranean, there exists a substantial

share of domestic trades. Moreover, there are several operators offering Ro/Ro

services on a mixed liner/tramp basis, which can hardly be attributed to

individual countries (total capacity of 127 vessels with 715,000 gross tons8). In

the Mediterranean, the majority of Ro/Ro services are observed in either

domestic traffic to Spain and Italy (33 %) or South Europe/North Africa (40 %)

and other intra-Mediterranean trades (26 %). The remainder consists of services

either between Baltic Sea and the Mediterranean or between Belgium/France-

Northern Africa.

As far as the spatial hierarchy of the network organisation is concerned, the

ports of Algeciras, Marsaxlokk and Gioia Tauro constitute the main "hubs" in

the western Mediterranean region. The port of Algeciras is ideally located for

meeting "hub and spokes" strategies in the region, since any deviation of

deep-sea vessels is avoided and significant routing optimisations can be

achieved. The port of Marsaxlokk is mainly oriented to direct transshipment

activities between mother vessels and feeder ships. Gioia Tauro, located near

the "gravity center" of Mediterranean flow patterns, has also a strategic

advantage for attracting an important share of transshipment business in the

region. Moreover, the ports of Barcelona, Marseilles-Fos, Genoa and La

Spezia develop hub strategies and constitute important alternatives for

transshipment business.

In the eastern Mediterranean region, no clear spatial hierarchy arise. The

ports of Piraeus, Damietta, Limassol, Larnaca, Alexandria have increased

their respective traffic volumes in the transhipment market. However, the

traffic evolution and distribution among these ports were not regular in the

recent past.

Based upon data published by Ocean Shipping Consultants9, feeder traffic for

eastern Mediterranean trade amount to about 723,000 GRT. About 13 % of total

capacities are related to trade between the East Mediterranean and North

Europe and 23 % to those between East Mediterranean and Black and Red

Sea, respectively10.

As far as a commodity-based segmentation is concerned, it should be pointed

out that a high proportion of the trade growth in the Mediterranean has been

in low value products, once shipped in bulk, but now treated as

containerisable. Such products are sugar and chemicals. It is the low value of

these products that has been instrumental in making freight rates, at best,

stable. It is this reduction in prices that has lessened the competition of trailer

operators, whose transit times are marginally better, but whose rates are very

significantly higher than shipping lines. Over the past two years, rates to Israel

for example, have declined by up to 30%, while to Turkey by up to 50%. Rates

are also being depressed by new network configurations substituting direct

8

G.P. WILD (International) Ltd.: The Ro-Ro Market, London 1994, p. 40.

9Ocean Shipping Consultants: Market Prospects for European Continerisation, Chertsey 1995, p. 12

10

M. Zachcial, “Land/Sea Transport flows in Europe”

© Association for European Transport 2002

calls through hub & spoke systems using for example Gioia Tauro as a hub

and spokes are as far along the eastern Mediterranean as Israel.

2.3. Trends of structural changes in the Mediterranean Short Sea

Shipping: organisational and technological aspects

The changes to be identified derive from intrinsic market developments. They

are mainly related to changing behaviors of the market actors either on the

supply or the demand side. Others are attributable to external factors, largely

beyond the control of short sea transport market forces. In conjunction, they

have created a new economic environment within which Mediterranean SSS

operates.

The most important structural changes derive from the strong trends to

reorganisation of production systems and distribution channels. The

increasing development of logistics is an element affecting the characteristics

of the demand for SSS, but also transforming the organization of the maritime

process per se. Production practices move steadily from the conventional

mass production and economies of scale towards a process dominated by

focused manufacturing of specific parts with earlier steps being conducted by

outside suppliers. Thus, new operational concepts are driving factors for

changes in industrial enterprises’ operations. They imply a just-in-time

manufacturing and procurement strategy, which is the supply of the exactly

required items at exactly the required quality, in exactly the required quantities

at exactly the required time. Those involved in this chain, from early suppliers

to final customers, favour the synchronisation of the whole transport operation

to serve an unbroken management of physical lows11.

The intensification of competition between transport modes for the same

consignment is another feature that characterizes the Mediterranean

environment. The expanding general cargo figures, particularly their most

profitable unitised part, represent commodities exposed to sharp modal

competition. Road and air are two modes already involved in business

logistics. Rail also competes strongly for around-Mediterranean traffic.

Excluding the cases where geographical characteristics impose short sea as

the unique viable choice (the case of islands), the competition has been

sharpened by developments to other transport modes. The construction and

operation of high-speed distribution networks within and between areas in the

Mediterranean and the Black Sea, once mainly served by sea shipping,

introduce prospects of growth in highly flexible low-cost inland transport

modes.

As port authority reformation evolved during the last decades, several different

models of port constitution have emerged, in particular privatisation and

commercialisation. Privatisation, which is in some ways the most transparent

of the above, has become the most fashionable trend and after the dramatic

11

US-based companies, in particular, have been among the first to take this view with many of them selecting a

single Mediterranean port of entry, to serve a wider geographical market through a just-in-time process. According

to a World Bank (1995) survey, by 1990 some 28% of all shipments in the US and EC were carried on a just-in-

time basis and the portion projected for 1995 was over one-third.

© Association for European Transport 2002

and controversial restructuring of the UK port industry in the early 1980s,

many Mediterranean countries have pledged to increase the role of the private

sector in their ports (e.g. Italy). Some others have already completed the

actual implementation of the deregulation policies (e.g. Spain), while others

are still pondering the best way forward (e.g. Greece). The growing number of

Mediterranean and Black Sea countries that have indicated the intention to

introduce some degree of private sector involvement in their national ports

industry, support the view that most governments (even those with centrally

planned economies) have now come to recognize the fundamental difference

between port administration and management.

A growing interdependence also marks the relationship between shippers and

shipowners. In a privatised environment, shipowners and the port industry will

become more interdependent than ever. To ports, the means to win traffic and

secure the continuity of costly adjustments presupposes closer cooperation

with the shipping lines. Such modernisation is of equal importance to

shipowners. It influences the variation of the costs associated with the port

interface12 and improves the speed of SSS. Due to the latter, the range of the

potential freights expands, and operators who invest in modern and larger

short sea vessels can increase their competitiveness and profitability.

Besides, the recent introduction of a new generation of fast ferries might be

the most important innovation in the market. Usually, the term "fast ferry"

refers to ferries with capacity for cars, trailers and busses, with or without

passengers, which can achieve a speed above 25 knots13. Three main types

of fast ferries can be distinguished:

• The small fast ferries with length between 50m and 90m, passenger

capacity between 250 and 500 and car capacity between 10 and 120.

They are enlarged fast boats with some car carrying capacity for pure

transportation routes only. Enlarged and wavepiercing catamarans and

monohulls are included.

• The medium fast ferries with length between 75m and 105m,

passenger capacity between 500 and 900 and car capacity between

140 and 210. They are equipped with onboard space for various

activities.

• The large fast ferries with length between 120m and 130m, passenger

capacity between 900 and 1500 and car capacity between 240 and

375. They are equipped with onboard activities similar to large

conventional ferries.

Fast ferries have less capacity than conventional alternatives, but a given

volume can be satisfied by a higher frequency. They have advantageous

conditions in calm waters but most of small and medium fast ferries are not

operational in high waves.

12

Which according to shipowners, currently stand on average above the total shortsea transport costs.

13

T. Wergeland and A. Osmundsvaag, "Fast ferries in the European Shortsea network: the potential and the

implications", Second European Research Roundtable Conference on Shortsea Shipping, Athens, 1994.

© Association for European Transport 2002

2.4. The current stage of Eastern Mediterranean Short Sea Shipping

evolution

The structural changes might create significant pressure for adjustments on

the Mediterranean SSS sector. The considerable quantitative and qualitative

changes come with the acquisition or loss of market shares, the break-up of

previous market balances, and fresh inter-industry relations. On the one hand,

they trigger intra-modal competition. On the other hand, they are forces

transforming the commercial relationships between the market players by

creating, for a variety of reasons, a growing interdependence of the market

actors. None of the players in the Mediterranean can stimulate its competitive

position if the others do not show the same level of adaptability. It is the entire

short sea sector that needs to improve the internal structure to remain

competitive within the new reality.

Nowadays, the essential adjustments are only partially in place. SSS is well

established in various Mediterranean corridors but a large part of its market

share results from compelling geographical circumstances, or mechanical

economic reasons (i.e. low value bulk commodities which benefit from scale

economies). The mode has yet to compete effectively in all intra-

Mediterranean markets. For instance, no-bulk trade between countries with

major container ports such as France and Spain is seldom carried in

containers by sea.

The size of the vessels has increased14 but kept up with technological

achievements only in limited routes. Obsolete ships are still in operation and

several market sections lack the services of available technologies. The

structure of the Mediterranean short sea fleet reveals that short sea operators

continue to use multipurpose general cargo or all-round Ro/Ro vessels, but

cellular containerships, characterised by a high flexibility in their operational

possibilities, represent only a minor part. The significant higher average age of

short sea vessels than that of deep-sea fleet confirms a slow replacement

cycle.

In addition, it is somewhat problematic to position fast ferries as a distinct

market within the Mediterranean SSS. This, because it is difficult to define the

"optimal" length of routes to operate. On the one hand, the distance must not

be too short, as the ratio of time spent in ports vs time saved at sea becomes

too high. On the other hand, the route must not be too long (for fast ferries for

both passengers and freight), since there is significant difference in comfort,

compared to conventional ferries.

Although ports specialisation implies substantial investments in infrastructure,

the level of these investments in the Mediterranean has followed a negative

trend, whether it is expressed as a share of the total of the investments in

transport infrastructure, or as a percentage of the GDP. The aggregate

14

The 1988 average size over 3000 dwt per vessel was more than twise the size of ten years before. That said,

there is not a clear cut of vessels operating in the Mediterranean shortsea market.

© Association for European Transport 2002

European OECD15 investments in transport infrastructure declined from 1,5%

of the GDP in 1975 to the relatively low 1% throughout the 1980s with the

share of ports decreasing from 5% to 3.5% of the total (ECMT16, 1991). True,

the absence of conventional capacity infrastructure is not a generalised

problem and, largely due to the vigorous competition that takes place even

between ports within the same country, most of the Mediterranean ports have

covered such needs. But at the end of the 1980s even the most successful

Mediterranean ports needed further modernisation to integrate into the

logistical systems. Moreover, in some Mediterranean regions and in the Black

Sea, ports have not kept pace, but they need to do so to overcome their less

efficient and less specialised facilities.

The adjustment process has not been facilitated by the national policy

frameworks that have either neglected or been ineffective at building up the

external environmental parameters that would improve the competitiveness of

the sector. In some cases, the national administration has followed a "road-

addicted" investment policy in transport infrastructure failing to modernise port

facilities. There is also an issue of adequate monitoring effects of policies, and

assessment of external costs in markets, implicating even the maintenance of

information regarding the current modal accommodation of demand. Recent

reviews of all Mediterranean national transport policies concluded that

comprehensive statutory requirements for environmental assessment seldom

exist, and practical experience is limited.

2.5. Special characteristics of Short Sea Shipping in the Black Sea

Black Sea occupies an area of about 411,540 km2 and together with the Azov

Sea, it exceeds 461,000 km2. The maximum distance between coasts is 1,125

km on the East-West, and 600 km on the North-South direction. Navigation is

possible throughout the year, exempt for the northern part of the Azov Sea,

where, during heavy winters, icebreakers are needed for no more than two

months. Three major navigable rivers flow into the Black Sea, the Danube, the

Niper and the Don, extending considerably what can be called “the Black Sea

maritime hinterland”. Together with the Rhine, the Danube forms a navigable

corridor, which crosses Central and Western Europe to the North Sea. The

Volga - Don Canal allows for ship navigation up to the Caspian Sea and then,

through Russian inland waterways, to the White Sea, passing from the

Moscow and the St. Petersburg area. The Black Sea is connected to the

Mediterranean through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles and then, to the

Atlantic Ocean through Gibraltar and to the Asia/Pacific region through the

Suez Canal. Major continental corridors (Pan-European corridors IV, VIII, IX)

are also connecting the Black Sea to the European hinterland. Corridor IV’s

section towards Sofia has an outstanding importance as it provides (with

corridor VIII and via-Egnatia) an East-West link to the Adriatic Sea.

The Black Sea forms a natural border of 6 countries: Romania, Ukraine,

Russia, Georgia, Turkey and Bulgaria. These six countries, together with

15

Organization for the Economic Cooperation and Development

16

European Conference of Ministers of Transport

© Association for European Transport 2002

Greece and Albania have created a zone of Economic Co-operation in the

Black Sea (BSEC), having as their main focus the development of transport in

the region.

There are more than 35 ports on the Black and the Azov Sea. About one third of

these ports are accessible to middle and large capacity ships. Such ports are:

Constantza, Odessa, Novorosiisk, Poti, Samsun, Istanbul etc., as well as the

ports situated on the Danube, namely Sulina, Tulcea, Galatzi, Braila in Romania

and Reni, Ismail in Ukraine. The planned port of Giurgiulesti in the Republic of

Moldavia, will soon be part of these ports.

The frequency of SSS services in the East-European and Black Sea ports is

weekly. Most of "hub and spokes" SSS actors serve the region using either the

port of Gioia Tauro or this of Marsaxlokk as transshipment basis17. The ports of

Black Sea are essentialy organised for handling bulk cargo. Few ports offer

facilities for serving unitised cargo. Considering that the total European non-bulk

trade does not exceeds 6%-7% of the total intra-European maritime traffic, the

corresponding containerised part of traffic volumes between Black Sea and the

rest of Europe must be smaller than 5%18.

3. ANALYSIS OF THE DECISION PROCESS OF INTERMODAL AND

SHORT SEA SHIPPING USERS

3.1. The framework of a specific research

The previous sections presented the main characteristics of the SSS market

in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea region, on the basis of

statistical data and aggregate research results. In this section, the paper tries

to complete the topic by understanding actors’ decisions for the use of SSS,

through a “behavioral” approach.

A better understanding of decision-making processes in transportation

necessitated a specific field survey. This survey covered all possible forms of

intermodal transport, SSS being one of the possible alternative forms. More

concretely, the objectives of the survey were:

• Identification of the key variables for the most common situations in

deciding whether to favor the use of intermodal transportation

• Identification of actor groups having common attitudes towards

intermodal transportation

• Identification of decision patterns, on the basis of which the choice of

intermodal transportation is made

Furthermore, the paper particularly focuses on decision patterns related to the

SSS cases.

17

The characteristics of SSS services and ports of Black Sea ports have been analysed in IQ project, Deliverable 2,

"Short-Sea Shipping" - Report number 2.2.13, 4th Framework Programme, European Commission-Directorate

General 7, 1998.

18

P. Sutcliffe and M. Garrat, "Container traffics in Europe-Changing patterns and policy options", Second

European Research Roundtable Conference on Shortsea Shipping, Athens, 1994.

© Association for European Transport 2002

3.2. Methodology

The methodology is developed for decision making at the firm/company level.

Three types of actors-decision-makers have been examined: forwarders/road

hauliers, shippers and shipping lines. The methodology does not follow a

specific “Origin-Destination” approach, but considers the overall firm’ behavior

and deployment of its operations at the European intermodal infrastructure

network.

The methodology follows two stages. At the first stage, fourteen qualitative

variables possibly affecting the decision-making process are examined

separately from each other. The actor types, in relation to the specific

individual shares of intermodal transportation related to their total

transportation volumes, have been recorded and the corresponding

frequencies are produced. Furthermore, possible correlations between the

importance of each decision criterion (and corresponding variable) and the

respective intermodal share of respondents are assessed. This stage is based

on descriptive statistics.

The second stage identifies common decision patterns, on the basis of

correlation between the criteria affecting the decision-making process. This

stage is based on a behavioral analysis assessing the importance that the

actors attribute to fourteen criteria. Based on this elaboration, the respective

generic groups of actors are identified. The method used at this stage is

Factor Analysis.

3.3. Data collection

The data required were gathered from a field survey at the European level. A

sample has been designed, consisting of 92 large companies with European

range of activities and distributed within 12 EU member states. The

companies were chosen almost proportionally to the economic status and

population of the countries. The companies surveyed are among the large

industries, producers of goods, Pan-European forwarders and carriers, as well

as international shipping lines, operating significant traffic volumes. Most of

these actors use intermodal transportation for some portion of the volumes

they handle. They could increase or reduce their share of intermodal

transportation, according to eventual changes in the characteristics of

services supply.

Three questionnaires have been drafted, respectively for forwarders or road

hauliers, shippers and shipping lines.

Firstly, basic information concerning the traffic volumes of respondents and

the respective individual intermodal transportation shares has been collected.

For the identification of common decision patterns and respective generic

groups of actors, qualitative data were collected. Questions related to the

perception the transportation actors have on the importance of various

variables affecting the decision-making process were included. The answers

record the importance of each variable in an artificial technical scale from 1 to

5 (1: being less important and 5: being highly important). Furthermore,

© Association for European Transport 2002

questions related to fourteen criteria, corresponding to the factors affecting the

decision-making process, are examined, which are.

- Cost factor: transportation Cost

- Internal to company factors: size of transportation order; commodity

types; regularity of shipment; warehouse location; historical tradition of

the company (how long they keep the same contract).

- Quality factors: reliability, flexibility and safety.

- External factors (from supply side): supply of suitable operating

systems (mostly rail), supply of adequate frequency of services,

additional logistics services supply, availability of information systems.

- Policy factors: EU transportation policy measures, regional/local policy

measures.

3.4. Results

3.4.1. Variables affecting the intermodal transportation use

Possible correlations between the importance of the fourteen criteria in the

decision-making process and the respective shares of intermodal

transportation by the groups of decision-makers are elaborated. However,

high average values of importance might not be determinant of users’

decisions. As an example, if safety is highly important but both road and

intermodal transportation offer similar performance in safety, the criterion of

safety would not influence the decision-making process. Consequently, two

aspects are examined:

• the mean qualitative values of importance accorded to each variable by

the respondents in the survey (in a scale from 1 to 5);

• the variation of the importance of each variable as it is related to its

impact on intermodal shares.

The mean qualitative values are presented in Table 1, as well as the intervals

for 95% confidence level.

TABLE 1. Mean values of importance of criteria per actor type and

intervals-95% confidence level

Mean values

Criteria Forwarders Shippers Shipping Lines Total

Transportation Cost 4,3 (± 0,3) 4,1 (± 0,5) 5,0 (± 0,0) 4,3

Size of Shipment 2,6 (± 0,4) 3,1 (± 0,5) 2,4 (± 0,7) 2,8

Regularity of Shipment 3,8 (± 0,4) 3,2 (± 0,5) 3,0 (± 0,8) 3,5

Warehouse Location 2,8 (± 0,4) 2,7 (± 0,5) 2,1 (± 0,7) 2,7

Historical Tradition 1,9 (± 0,4) 1,6 (± 0,3) 1,1 (± 0,1) 1,7

Reliability 4,3 (± 0,3) 4,0 (± 0,5) 3,1 (± 1,0) 4,0

Flexibility 3,5 (± 0,4) 3,5 (± 0,5) 2,8 (± 1,0) 3,4

Safety 3,6 (± 0,5) 3,7 (± 0,5) 2,4 (± 1,0) 3,4

Operating systems 3,5 (± 0,4) 3,1 (± 0,5) 2,7 (± 0,9) 3,2

Frequency of services 4,0 (± 0,3) 3,5 (± 0,4) 2,8 (± 1,0) 3,6

Additional logistics services 2,1 (± 0,4) 2,6 (± 0,4) 2,4 (± 0,8) 2,3

Information systems 2,9 (± 0,4) 2,8 (± 0,5) 2,4 (± 0,8) 2,8

EU transportation policy 1,9 (± 0,4) 2,2 (± 0,4) 2,1 (± 0,7) 2,1

Regional/local policy 2,4 (± 0,5) 2,5 (± 0,5) 2,2 (± 0,9) 2,4

Other 1,7 (± 0,4) 1,4 (± 0,4) 1,3 (± 0,6) 1,6

© Association for European Transport 2002

The variations in the intermodal shares corresponding to the decision-makers,

associated with the variations in the importance that they attribute to each

variable are analysed. Using the Fisher test, the analysis proved that the

variation of importance of variables do not present a statistically accepted

correlation with the shares of intermodal transportation. Consequently, the

statistical analysis can lead to the following general conclusions:

• The three actor types (forwarders, shippers, shipping lines) do not

demonstrate significant differentiation, as far as their perception of the

variables affecting the decision-making process is concerned.

• Cost and reliability are the most important criteria for their decisions.

• Similarly, frequency of services offered and operating systems are the

most important criteria considered from the supply side (in order to

meet their requirements).

• Regularity of shipments is almost a prerequisite for using intermodal

transportation.

• For shipping lines, the cost factor is much more important than quality

variables.

Among the variables examined, the variation in the importance attributed to

the cost factor does not significantly differentiate the individual shares of

intermodal transportation. However, the “absolute” importance of the cost

factor had been confirmed.

3.4.2. Decision patterns and actor groups

The identification of decision patterns are based on the correlation between

the criteria used for identifying the decision making by the actors. Factor

analysis was applied to find such correlations, which are presented in a Factor

Loadings Matrix. Table 2 specifies the factors and answers the question

“which criteria are strongly correlated in the decision-making process”.

TABLE 2. Factors Loadings Matrix

Variables Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3

Frequency of services 0,81

Reliability 0,79

Regularity of Shipment 0,74

Safety 0,66

Operating Systems 0,63

Information systems 0,61 0,43

Warehouse Location 0,50 -0,40

Flexibility 0,49 0,37 -0,28

EU transportation policy 0,86

Regional/local transportation 0,80

policy

Additional logistics services 0,68

Historical tradition 0,35

Transportation cost 0,74

Size of Shipment 0,26 -0,36

© Association for European Transport 2002

The analysis suggests the consideration of three factors, which cluster the

criteria. The coefficients of correlation measure the strength of association

between variables. The value of this measure ranges between –1 (a perfect

negative relationship in which all points fall on a line with negative slope) and

+1 (a perfect positive relationship in which all points fall on a line with positive

slope). A value of 0 indicates no linear relationship.

The three factors identified indicate three different attitudes in the decision-

making process for using intermodal transportation or not. Factor 1 represents

a decision pattern mainly based on both quality and cost criteria concerning

transportation. The decision-makers falling into this decision pattern value

greatly the quality criteria of reliability, safety and flexibility. Moreover,

decision-makers relate the demand side criteria to the respective criteria from

supply side: frequency of services, operating systems, and information

systems offered.

Factor 2 represents a decision pattern based on criteria of a “specific” context

or a specific market area, with particular socio-economic and infrastructure

characteristics. Issues of transportation policy at European, regional and/or

local level determines the final modal choice by the users. In addition, in this

“specific” decision pattern, the supply of additional logistics services plays a

major role, and it is influenced by historical and traditional factors is also taken

into account.

Factor 3 represents a decision pattern almost exclusively based on the

criterion of transportation cost. This represents the most traditional decision

pattern in transportation. The negative signs in the column of Factor 3 mean a

negative correlation. As an example, when the importance of variable

Warehouse Location is rising, the weight of this variable decreases in Factor

3.

Based on the extracted factors, the most distinct generic groups of actors are

identified, according to the importance they place on the decision criteria

during the decision-making process. The application of a Hierarchical Cluster

Analysis within the sample identifies three relatively homogeneous groups of

actors, which correspond to three distinct decision patterns. The group

composed of actors falling in the decision pattern based on quality criteria

(Factor 1) is labeled “Quality-cost oriented” group. The group consisted of

actors falling in the decision pattern derived from a specific environment of

operations (Factor 2) is labeled “Specific” group. The group composed of

actors falling in the decision pattern based on the criterion of cost (Factor 3) is

labeled “Cost oriented” group. The composition of the sample of interviewed

companies, according to the three actor groups is presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3. Decision patterns and actor groups

Factor Actors group % of the sample (respondents)

1 "Quality-cost oriented" 45,1

2 "Specific" 19,8

3 “Cost oriented” 35,1

© Association for European Transport 2002

The “specific” group represents approximately 1/5 of the total sample. Taking

into account the selected criteria, on which this group proceeds to the

decision-making, the size of this group is relatively important. In addition it

assesses that 1/5 of users of intermodal transportation makes decisions on

the basis of specific logistical needs (e.g., demand for third party end-haul

operations, refrigerated storage areas etc), and the particularities of the

respective geographical areas from supply side. The criteria governing their

decision-making process can be neither generalized nor valid everywhere. It

appears that in these cases, the characteristics of intermodal transportation

supply differentiate from the general characteristics of intermodal

transportation supply in Europe. Consequently, in one case out of five, the

decision pattern of intermodal transportation users cannot be generalized.

3.4.3. Decision patterns and shares of intermodal transportation

Almost all actors included in the sample are non-exclusive users of intermodal

transportation. The volumes of continental traffic are also transported with

door-to-door road modes. However, three groups of actors with distinct

attitudes towards intermodal transportation have been identified. On the other

hand, all actors are faced with a given context of intermodal services supply.

Consequently, the three distinct attitudes might lead to differentiation of the

“intensity” of intermodal transportation use per actor group.

The analysis examined the “individual” shares of intermodal transportation of

actors for each group. It revealed distinct ranges of individual intermodal

transportation shares per actor group, which are ranked accordingly in Figure

1.

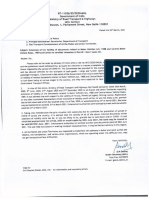

FIGURE 1. Ranked diagram of individual intermodal transportation

shares

100

90

Intermodal transport share (%)

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Observations

"Specific" "Quality oriented" "Cost oriented"

All companies are graphically represented. The result is a ranked disposition

of individual shares of intermodal transportation. According to the diagram, the

intermodal transportation shares of the “cost oriented” group range from 50%

© Association for European Transport 2002

to 100% of total individual traffic volumes. The shares of the “quality-cost

oriented” group range from 10% to 50% of total individual traffic volumes.

Finally, the shares of the “specific” group range from 0% to 10%.

3.5. Identification of decision patterns of Short Sea Shipping in the

Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea

Given the previous research results, an additional elaboration allows

identifying the SSS cases in the three major decision patterns. The main

results are presented hereafter:

• The SSS cases represent approximately 30% of the sample

• All actor types (shippers, forwarders, shipping lines) are represented in

cases of short sea choice

• The SSS cases in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea

represent less than 20% of the sample

• Decision patterns of SSS in their largest part refer to the “cost oriented”

group.

• The small number of cases belonging to the “quality-cost” oriented

group concerns the Adriatic-Ionian corridor.

Considering these results, the SSS market share in the Eastern

Mediterranean region is far from meeting high quality requirements.

Inadequate and outdated port installations are largely responsible for the

slowness of maritime transport. Very often, ships are forced to spend too

much time in port due to equipment poorly adapted to current conditions. Ship

owners estimate their vessels spend on average 60% of total transport time in

ports and only 40% at sea. Similarly, over-inflated and highly variable port

fees sharply increase the cost of maritime transport. They represent up to 70-

80% of the cost of SSS, especially in ports where vessels are charged for

services they neither want nor need.

4. CONCLUSION

In the recent years, the SSS in Eastern Mediterranean is characterised by a

remarkable expansion and structural modifications as well. However, within

Europe the SSS activity does not seem to achieve an appropriate level of

recognition or market share in the overall transport network. As an industry it

has grown considerably during the 1990s as available data indicates, but this

growth was somewhat lower than that of road transport in the same period.

The traffic increase is mainly related to the feeder activity, that contributed to a

remarkable growth of containers handled in Mediterranean ports. However,

the containerization rate remains significantly low in the Eastern part,

compared to the ports of western Mediterranean and northern Europe. The

region’s ports have been lagging behind their northern competitors in terms of

investment, pricing efficient management, and physical accessibility to large

markets. Feeder and Ro/Ro traffic being the most expanded market niches,

the current split between them is well in advance of feeder services for

relatively long distance voyages, and of Ro/Ro mainly for short distance

coastal shipping. The Mediterranean Ro/Ro services market presents shares of

© Association for European Transport 2002

about 50 % for each of the western and eastern part of the Sea. As far as a

commodity-based segmentation is concerned, a high proportion of the trade

growth in the Mediterranean has been in low value products, once shipped in

bulk, but now treated as unitized cargo. Particularly in the Black sea, the

containerization rate must be smaller than 5%, considering that the total

European non-bulk trade does not exceeds 6%-7% of the total intra-European

maritime traffic.

A number of structural trends create significant pressure for adjustments on

the Mediterranean SSS sector. Among them, the increasing development of

logistics is an element affecting the characteristics of the demand for SSS, but

also transforming the organization of the maritime process per se. A growing

interdependence between shippers and shipowners is changing the actors’

relationships. The intensification of competition between transport modes is

affecting the quality aspects of transport services. The privatisation and

commercialization procedures are changing the management concepts of port

authorities. Finally, the recent introduction of a new generation of fast ferries

might significantly affect the modal choice of users.

The decision-making in choosing SSS as an alternative transport mode is a

quite complicated process. More generally, the attitude of actors towards

intermodal transportation results from both “objective” characteristics and

individual perceptions. Taking into account the multiplicity of variables and

contexts, there is no standard approach. Each company proceeds to

decisions in an individual way. Without neglecting this fact, the paper

investigated common patterns (and not detailed attitudes) in the decision-

making process followed by transportation users.

Three distinct groups of decision-makers and respectively three decision

patterns have been identified. The first group, so-called “cost oriented” group,

structures its decision pattern almost exclusively on the criterion of

transportation cost. The second group, also labeled “quality-cost oriented”

group, develops a decision pattern on the basis of quality criteria of

transportation. The third group, labeled “specific” group, refers to “specific”

contexts or specific environments of operations. Each actor group includes

forwarders and road companies, shippers and shipping lines, which can

consider either internal or external to companies factors in an identical way.

Almost all the actors included in the three groups of decision-makers split their

total volumes of continental traffic between intermodal and door-to-door road

transportation. The elaboration of the findings refer to a given context of

intermodal services supply, which is the same for all.

The cases of SSS users in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea

mainly belong to the “cost oriented” group. It concern commodities that do not

require high quality performance in transportation operations. The absence of

good intermodal transportation performance in reliability and flexibility,

compared to road transportation, does not considerably affect the choice of

these users, even for small differences between intermodal and road

transportation cost. However, the regularity of shipments, safety and duration

© Association for European Transport 2002

aspects of intermodal transportation use are variables that affect the modal

choice for intermodal transportation. This represents the most traditional

decision pattern in transportation. In any case, the “cost oriented” group is the

most “intensive” user of intermodal transportation.

A minor part of SSS traffic in the region, almost exclusively concerning the

Adriatic-Ionian corridor, refers to the decision pattern of “quality-cost oriented”.

This group considers the criteria of reliability, safety and flexibility in an

integrated way. These criteria, which derive from their own requirements, are

associated with the respective criteria from supply side: frequency of services,

operating systems, and information systems offered. The intermodal share

changes are also correlated to commodity types and influenced by the

ownership of intermodal assets. The “quality-cost oriented” group also

presents a relatively important potential demand for the intermodal

transportation market.

The integration of SSS into more sophisticated just-in-time systems remains a

permanent problem in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Transit times may be

inaccurate and delivery times from port to importer premises are subject to

lengthy delays in customs clearance. Customs clearance is still a big problem

in Trade between Member-States of the European Union and third countries

and it is reckoned that, in some cases, delivery from port to importers

premises can take as long as the whole sea voyage. The necessary policy

actions in order to take advantage of this potential must focus on

improvements of quality performance.

The exploration of the SSS potential in the region is related to a process-

oriented treatment of goods and information, for logistics and for new types of

cargo. This inaugurates a new role for the Mediterranean ports. The traditional

conception of a "gate" simply providing the facility of transferring cargoes

between ship and quayside becomes no longer adequate. Along with

conventional operations, ports need to work as intermodal nodal centres

providing a range of complementary storage and distribution services. The

cargo generating capacity remains a powerful element but other qualitative

factors - i.e. inland connections or provision of electronic data information -

come into play. In their absence, ports cannot meet the demand for

commodities to be delivered (or transshipped) quickly and predictably, and the

user considers the employment of the mode as a disadvantage of the

production function. In order to compete in this changing environment,

Mediterranean ports have to adjust quickly, become bigger in terms of

infrastructure, and increase their handling capacity by introducing new and

sophisticated equipment. A more flexible constitutional, fiscal and operational

framework should accompany all these.

© Association for European Transport 2002

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beuthe M., Jourqouin B., Charlier J., 15th International Symposium on Theory

and Practice in Transport Economics, Topic 2b: Intermodality. Thessaloniki, 7-

9 June 2000.

Bronzini, M.S. Evolution of a Multimodal Freight Transportation Network

Model. Proceedings of the Transportation Research Forum 21(1), 1980. pp.

475-485

Communication from the Commission. “Intermodality of goods transportation”,

COM (1997) 243, Brussels, 1997.

Communication from the Commission: ‘The development of Short Sea

Shipping in Europe: A dynamic alternative in a sustainable transport chain’

Second two-yearly Progress Report, COM (1999) 317 Final.

Communication from the Commission: ‘Seaports, Inland ports and intermodal

terminals in the trans-European transport network’ COM (97) 681 Final.

Communication from the Commission: ‘The Common Transport Policy Action

Programme 1995 – 2000’, COM (95) 302 Final.

Communication from the Commission: ‘The future development of the

common transport policy: A global approach to the construction of a

community framework for sustainable mobility’, COM (92) 494 Final.

Consultrans S.A. ‘Study of the Mediterranean region (port systems and

maritime transport) for the EU’s DGVII’, October 1995.

European Commission: DG VII, DG XIII ‘Joint Call on Transport Intermodality’,

September 1997.

Daly, A.J.. Applicability of disaggregate models of behavior: a question of

methodology. Transportation Research, 16A. 1982.

European Community Shipowners’ Association, Annual Report 1997 – 1998.

‘Green Paper on Sea Ports and Maritime Infrastructure’, COM (97) 678 Final.

Harker, P.T. The state of the art in the predictive analysis of freight

transportation systems. VNU Science Press. 1985.

Gray, R.. A socio-organisational approach to surveying the demand. 2nd

International Conference on New Survey Methods in transportation Research.

Australia. 1983.

INRETS, Quality Label, Study of the European Commission-Directorate

General TREN. Brussels, 1996.

IQ – “Intermodal Quality” project, 4th Framework Programme, European

Commission-Directorate General VII, 1998.

© Association for European Transport 2002

LOGIQ-The decision-making process in intermodal transportation. 4th

Framework Programme on RTD. European Commission-Directorate General

TREN. Brussels, 1999.

Nutt, P. C.. Some guides to the selection of a decision-making strategy.

Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 19(2). 1981.

Kim, D and Barnhart C. Multimodal Express Shipment Service Design: models

and algorithms, Computers Ind. Engineering Journal. Vol.33 (no.3-4).

1997.685-688

Ocean Shipping Consultants: Market Prospects for European Continerisation,

Chertsey 1995.

H. Psaraftis, O. Schinas, ‘Research in Shortsea Shipping: The state of the art’.

Matas et. al ‘The economic aspect of charging for TEN seaport infrastructure in

the European Union’, June 1998.

P. Sutcliffe and M. Garrat, "Container traffics in Europe-Changing patterns

and policy options", Second European Research Roundtable Conference on

Shortsea Shipping, Athens, 1994.

Tavasszy A. L., Smeenk B. and Ruijgrok J.C. A DSS for modeling Logistic

Chains in Freight Transport Policy Analysis, presented at the 7th International

Special Conference of IFORS: Information Systems in Logistics and

Transportation. Gothenburg, 1997

T. Wergeland and A. Osmundsvaag, "Fast ferries in the European Shortsea

network: the potential and the implications", Second European Research

Roundtable Conference on Shortsea Shipping, Athens, 1994.

G.P. WILD (International) Ltd.: The Ro-Ro Market, London 1994.

© Association for European Transport 2002

Вам также может понравиться

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- B22X-7 Sb1240e05 PDFДокумент1 093 страницыB22X-7 Sb1240e05 PDFGORDОценок пока нет

- Does A Chevrolet Spark Have A Timing Belt or Timing ChainДокумент11 страницDoes A Chevrolet Spark Have A Timing Belt or Timing ChainUltraJohn95Оценок пока нет

- RyanairДокумент2 страницыRyanairSouhila BenzinaОценок пока нет

- VW Atlas - Brake SystemДокумент101 страницаVW Atlas - Brake SystemPaweł PaczuskiОценок пока нет

- Appendix A - Illustrated Parts CatalogДокумент100 страницAppendix A - Illustrated Parts CatalogKrasakKrusuk Si MaulОценок пока нет

- Delta Airlines ReservationsДокумент2 страницыDelta Airlines ReservationsAirlines MapОценок пока нет

- DHL Tracking InternationalДокумент1 страницаDHL Tracking InternationalLawrance Viaga MichaelОценок пока нет

- A Technical Seminar REPORTДокумент8 страницA Technical Seminar REPORTVijay VinniОценок пока нет

- Z - 80/60 Specifications: Self-Propelled Articulating BoomsДокумент2 страницыZ - 80/60 Specifications: Self-Propelled Articulating BoomsThang VoОценок пока нет

- EMPL Recovery Vehicle Operating ManualДокумент160 страницEMPL Recovery Vehicle Operating ManualSayel MokhaimerОценок пока нет

- Fusilera Cavalier 94Документ4 страницыFusilera Cavalier 94anzony francoОценок пока нет

- Ogilvy Creative Briefchevy - Brief PDFДокумент4 страницыOgilvy Creative Briefchevy - Brief PDFRahul TatooskarОценок пока нет

- Air New ZealandДокумент2 страницыAir New ZealandGolnaz TavakoliОценок пока нет

- 3mandy ChongДокумент3 страницы3mandy ChongzzaentzОценок пока нет

- 1269767GTДокумент278 страниц1269767GTJosé MonsiváisОценок пока нет

- Dost Steel Container PDFДокумент2 страницыDost Steel Container PDFSyambabuОценок пока нет

- Karach Metro Bus ProjectДокумент4 страницыKarach Metro Bus ProjectAdeelОценок пока нет

- UNSPSC CodesДокумент1 352 страницыUNSPSC CodesRohit Arora0% (1)

- Lines CodesДокумент30 страницLines CodesMuhammad SiddiuqiОценок пока нет

- 1999 & 2000 Model Year Dealer Reference ManualДокумент27 страниц1999 & 2000 Model Year Dealer Reference ManualCarlos FernandesОценок пока нет

- Marketing Strategy & Implementation TATA Nexon EVДокумент11 страницMarketing Strategy & Implementation TATA Nexon EVPakshal Shah80% (5)

- Loading InstructionsДокумент27 страницLoading InstructionsGuilherme LopesОценок пока нет

- What's Ahead For Car Sharing?: The New Mobility and Its Impact On Vehicle SalesДокумент17 страницWhat's Ahead For Car Sharing?: The New Mobility and Its Impact On Vehicle Saleswoodlandsoup7Оценок пока нет

- XGC55操作手册(英文) 7 用户验收项目Документ3 страницыXGC55操作手册(英文) 7 用户验收项目alatberat sparepartОценок пока нет

- B11R Jonckheere JHV2 SpecДокумент1 страницаB11R Jonckheere JHV2 SpecVishwanath SeetaramОценок пока нет

- TCCA TP 12295e - Flight Attendant Manual Standard PDFДокумент68 страницTCCA TP 12295e - Flight Attendant Manual Standard PDFPavithran DОценок пока нет

- AI331Документ124 страницыAI331danny.zhaoОценок пока нет

- Extension of ValidityДокумент1 страницаExtension of ValidityChampaka Prasad RanaОценок пока нет

- PCR CatalogДокумент24 страницыPCR CatalogIrdayante AzlanIrdaОценок пока нет

- KA18C3733 InvoiceДокумент3 страницыKA18C3733 InvoiceMahesh U GОценок пока нет