Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Franko Subrayado

Загружено:

dedanza128Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Franko Subrayado

Загружено:

dedanza128Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

See

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254933819

Writing for the Body: Notation,

Reconstruction, and Reinvention in

Dance

Article in Common Knowledge · April 2011

DOI: 10.1215/0961754X-1188004

CITATIONS READS

17 298

1 author:

Mark Franko

Temple University

71 PUBLICATIONS 196 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Baroque Modernities: Rethinking French Dance of the Twentieth Century View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Mark Franko on 13 June 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

1 S y m p o s i u m : B e t w e e n Te x t a n d P e r f o r m a n c e

2

3

4

5

6

7

WRITING FOR THE BODY

8

Notation, Reconstruction, and Reinvention in Dance

9

10

11

12

13

Mark Franko

14

15

16

17

18 Choreography, from the etymological perspective and by virtue of current usage,

19 seems to be a portmanteau word referring to two kinds of action: writing ( gra-

20 phie) and dancing (choros). As such, the word choreography seems to encode a theory

21 of the relation of dance to scripturality — of writing as movement and dance as

22 text.1 The theory seems to be that movement originates in the text through which

23 it is initially thought and recorded. But an implication of the theory is that some-

24 thing called choreography remains in the wake of its performance. In other terms,

25 choreography denotes both the score of a dance and the dance itself as perceived

26 in real time and space — which raises the question: When we observe a dance,

27 do we also observe (its) writing?2 That question could be rephrased to ask: What

28 does it mean to “see” choreography? The writing I refer to as being “seen” is not

29 necessarily synonymous with notation. But notation generally also conjures up

30 the image of a dance in preparation or a dance remembered. The history of nota-

31

32 1. For an introduction to the range of issues that are 2. See Nelson Goodman, Languages of Art (Indianapo-

33 emerging in contemporary theory from the dance-writing lis, IN: Hackett, 1976) for a philosophical investigation

34 conjuncture, see Carrie Noland and Sally Ann Ness, eds., of score and notation in the context of representation:

Migrations of Gesture (Minneapolis: University of Minne- “a score is commonly regarded as a mere tool, no more

35 sota Press, 2008). intrinsic to the finished work than is the sculptor’s ham-

36 mer or the painter’s easel” (127).

37

38 Common Knowledge 17:2

39 DOI 10.1215/0961754X-1188004

40 © 2011 by Mark Franko

41 321

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd 321 1/12/11 12:55:06 PM

tion is thus related to that of publishing.3 But, possibly thanks to the modernist 1

322

intertwining of dance and poetry, contemporary thought on dance is frequently 2

split between a concept of dance-as-writing and a concept of dance as beyond 3

COMMON KNOWLEDGE

the grasp of all language, especially written language.4 The trope of dance-as- 4

writing assumes that one does not go to the theater only to see dancing but also 5

to “read” something called choreography, which is “written” in time and space. 6

There is an argument to be made that choreography exists as a visual component 7

of the dance as it is being performed: the dance itself, independently of its actual 8

performance, has an identity. The history of dance notation always reflects this 9

complex relationship among dance, language, and writing, though the role of 10

notation changes dynamically from the Renaissance through the twenty-first 11

century and thus exerts a powerful influence on what we believe dance to be, and 12

on how we experience it. 13

The Renaissance tablature in which letters represent named steps — the let- 14

ters run along the edge of the musical staff to indicate how a step correlated with 15

the music written for it — constituted the first attempt in the West at notation for 16

courtly social dance. Early examples of tabulation are found in the Spanish Cer- 17

vera manuscript (second half of the fifteenth century), which uses both letters and 18

symbols, and the Burgundian Manuscrit dit des basses danses (c. 1523). The earliest 19

published notation is in Michel de Toulouse’s dance manual, L’art et instruction 20

de bien dancer, which appeared toward the end of the fifteenth century. In 1588 21

Thoinot Arbeau used the letter system along with verbal description in his dance 22

treatise Orchesographie. Early modern notation of courtly social dance set a prec- 23

edent for the representation of danced steps with linguistically based signs, which 24

were frequently letters of the alphabet.5 The alphabetical sign was derived from 25

the abbreviation of the step’s name: r for révérence, b for branle, and so forth. The 26

sign also indicates that at least symbolic relations existed among choreography, 27

natural language, and writing (printing) — relations reinforced by the appear- 28

ance of notated dances in book form (the dance treatise or manual) toward the 29

end of the sixteenth century. Like writing itself, notation was divorced from the 30

expressive realities of what linguists call enunciation; that is, the act of producing 31

sounds or movements in real time and space are separated from their essentially 32

“oral” character. Treatises in which notation occurred are notorious for provid- 33

34

3. See Marie Glon, “The Materiality of Theory: Print 4. Hence phenomenology has contributed significantly to 35

Practices and the Construction of Meaning through Kel- dance theory throughout the twentieth century. A forth- 36

lom Tomlinson’s The Art of Dancing explain’d (1735),” in coming special issue of Dance Research Journal on “Dance

Society of Dance History Scholars Proceedings (Thirteenth and Phenomenality: Critical Reappraisals” will explore 37

Annual Conference Co-Sponsored with CORD Centre this relationship in depth. 38

national de la danse, Paris, France, June 2007), 190 – 95.

5. These can be classed as “word and word abbreviation 39

systems.” See Linda J. Tomko, “Dance Notation and Cul- 40

tural Agency: A Meditation Spurred,” Dance Research Jour-

nal 31.1 (Spring 1999): 1.

41

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd 322 1/12/11 12:55:07 PM

1 ing no insight into the physical dynamics and stylistic detail of movement. One

323

2 important term for historical dance, fantasmata, is a notable exception.6 Found in

3 Domenico da Piacenza’s early-fifteenth-century treatise, fantasmata as a stylistic

B e t w e e n Te x t a n d P e r f o r m a n c e

4 term is central to the performance of historical dance from the fifteenth to the

5 seventeenth century. As a kinesthetically based term, however, fantasmata eludes

6 notation.

7 More or less contemporaneously with the emergence of notation in the late

8 Renaissance, geometrical or letter dances staged bodies as letters of the alphabet

9 and other visual symbols. Geometrical dance, as a choreographic rather than a

10 notational phenomenon, inverted the relationship between dance and text, mak-

11 ing dance appear textual in its very performance. Choreography emulated the

12 spatial presentation of written characters.7 The geometrical patterns had sig-

s

13 nificance as letters forming words or as allegorical signs. Libretti for some court

Franko

14 ballets with geometrical dances show the successive patterns of the dances, but

15 without any indication of the movement that configures and evolves the patterns.

16 The figures are noted on the page as configurations of dots marking the place-

17 ment of each dancer. Hence aspects of early notation suggest that reading was

18 intrinsic both to decoding a social dance and to watching theater dance. Dance

19 history presents us with a complex weave of oral and choreographic culture.

20 Baroque dance (also known as la belle danse), which developed chiefly in

21 France during the seventeenth century, had a far more extended and intricate

22 vocabulary than Renaissance dance. A new form of notation was invented for it by

23 Raoul-Auger Feuillet, based on the work of choreographer Pierre Beauchamps,

24 which appeared in print by 1700.8 As Sally Ness has observed: “Wherever codi-

25 fied gestural techniques have evolved, wherever habits of movement practice have

26 stabilized enough to produce a continuity of movement style, general principles

27 of conduct are operative in a performance discipline.”9 With the baroque, dance

28 reached the status of a discipline in the Western tradition. Feuillet notation,

29 which codified the step, the path of choreography through space, and its rela-

30 tionship to music, was much more comprehensive, and much more challenging

31 to decode, than Renaissance tabulation (Figure 1). Although Feuillet notation is

32 a track system rather than a word-based system, it shares grammatical aspects of

33 language-based symbolization. Its very possibility suggests that baroque dance

34 alphabetizes the body from the hip down into tropological relationships. Other

35 aspects of writing infiltrate its denser grid: notably, the concept of floor pattern

36

37 6. See Mark Franko, “The Notion of Fantasmata in Fif- 8. Raoul Auger Feuillet, Chorégraphie ou l’art de décrire la

38 teenth-Century Italian Dance Treatises,” Dance Research danse (1701; Bologna: Forni, 1970).

Annual 17 (1987): 68 – 86.

39 9. Sally Ann Ness, “The Inscription of Gesture: Inward

7. For an analysis of geometrical dance, see Mark Franko, Migrations in Dance,” in Migrations of Gesture, ed. Carrie

40

Dance as Text: Ideologies of the Baroque Body (Cambridge: Noland and Ness (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

41 Cambridge University Press, 1993). Press, 2008), 10.

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd 323 1/12/11 12:55:07 PM

as the page and the concept of the body as a cipher on the page.10 The page itself 1

324

becomes the floor one traverses in dancing, obliging the decoder to read not only 2

in a linear but also in a diagrammatic manner. The sense of the floor as square 3

COMMON KNOWLEDGE

and the typical symmetry of the patterns is easily encompassed by the page or 4

the open book.11 These spatial relationships — the relations of the dance floor and 5

the danced patterns upon it to notational script and the page — underlie the sense 6

that baroque dance existed largely in relation to the conditions of possibility of 7

its own notation. 8

In the case of baroque dance, we are confronted with the situation that 9

Michel Foucault called the classical episteme, in which the representation of real- 10

ity corresponds point for point with reality itself.12 11

The end of the classical episteme of representation (in the eighteenth cen- 12

tury, which corresponds in dance to the ballet d’action) introduces a disparity 13

between action and the ways of representing action — a decline in what is know- 14

able by humankind about its own activities. The reform of ballet d’action aims at a 15

reduction of conventions surrounding dance vocabulary and a new emphasis on 16

expression. Baroque dance, particularly in France, deployed a formal courtly and 17

highly technical vocabulary that underwent significant transformations in the 18

hands of ballet masters such as Gaspero Angiolini, Jean-Georges Noverre, and 19

Jean Dauberval, becoming, over the course of the eighteenth century, “theater 20

dance,” with an emphasis on emotional expression and narrative.13 Pierre Rameau 21

and others proposed variants of Feuillet notation throughout the eighteenth cen- 22

tury, also using images of the body; but this was the period of the gradual decline 23

of court ballet as theater dance. The form of dance that was in decline was of 24

the same formal nature as the notation designed to preserve it. Ballet d’action, 25

like glotto-genetic language theories of the eighteenth century, was interested in 26

emotion as the genealogy of speech. No new system of notation arose to record 27

the pantomimic innovations of ballet d’action, possibly because it subscribed to 28

a concept of gesture as the primitive origin of language. Condillac, Rousseau, 29

and Vico began the discussion in the eighteenth century of original language, in 30

which gesture was thought to be at the basis of natural language and hence also of 31

theatrical speech. The model for dance at this time was the voice rather than the 32

text. One could say that the presence of the written sign in dance history up until 33

this time was symbolic of a desire to reject the role of the voice in the production 34

35

10. Yet Feuillet notation still leaves substantial space for 12. Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of 36

the dancer’s individual agency. See Tomko, “Dance Nota- the Human Sciences (New York: Vintage, 1970), 106.

tion and Cultural Agency,” 3.

37

13. See Edmund Fairfax, The Styles of Eighteenth-Century

38

11. A visual rendering of this relation between dance and Ballet (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2003).

writing was developed by me and the visual artists Anne 39

and Patrick Poirier in “Curiositas Cabinet,” installation 40

on permanent exhibit, Getty Center for Research in the

41

History of Art and the Humanities, 1996.

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd 324 1/12/11 12:55:07 PM

1

325

2

3

B e t w e e n Te x t a n d P e r f o r m a n c e

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

s

13

Franko

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27 Figure 1. A page from Raoul Auger Feuillet’s Choreographie (1701).

28

29 of movement.14 It would be a contradiction in terms to have prelinguistic gesture

30 recorded in a sign system, when it is precisely the conventional theatrical and

31 linguistic sign that this form of choreography puts into question. Feuillet nota-

32 tion did not keep pace with the aesthetic and ideological advances of ballet in the

33 Enlightenment and was destined to become obsolete.

34 In the nineteenth century, technical writing on dance becomes more

35 engaged with the dancer’s technique. Carlo Blasis (1795 – 1878) did not preserve

36 his choreography in notation but used images and text to perfect the technique

37

14. For background on “original language,” see Hans languages for choreographic performance practice, see

38 Aarsleff, “The Tradition of Condillac: The Problem of the Mark Franko, “Relaying the Arts in Seventeenth-Century

39 Origin of Language and the Debate in the Berlin Academy Italian Performance and Eighteenth- Century French

40 before Herder,” in Studies in the History of Linguistics, ed. Theory,” in Wissenskultur Tanz. Historische und zeitgenös-

Dell H. Hymes (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, sische Vermittlungsakte: Praktiken und Diskurse, ed. Sabine

41 1974), 93 – 156. For more on the ramifications of original Hushka (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2009): 55 – 69.

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd 325 1/12/11 12:55:07 PM

1

326

2

3

COMMON KNOWLEDGE

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Figure 2. An Illustration from Carlo Blasis, Theory and Practice of the 25

Art of Dancing

26

27

of the Romantic dancer, thereby ushering in modern ballet technique. An image

28

from his An Elementary Treatise upon the Theory and Practice of the Art of Dancing

29

(1820) shows that the host material of dance was no longer the figure understood

30

as the path through space, but the figure as the dancer’s body itself.15 While the

31

treatise might be considered a technical manual, in it, for the first time, writing

32

addresses not only the what but the how of dance (Figure 2). This focus on the

33

body as instrument (to the detriment of any focus on the path through space and

34

on spatial relationships between dancers) corresponds to the Romantic ballerina’s

35

goals, in the early nineteenth century, of weightlessness and ethereality.

36

Notational systems began to emerge again in the nineteenth century —

37

among them, those found in E. A. Theleur’s Letters on Dancing (1831), Michel

38

Saint-Leon’s Sténochoregraphie (1852) which uses stick figures, August Bournon-

39

ville’s notebooks (1855), Bernhard Klemm’s Katechismus der Tanzkunst (1855), Albert

40

15. See Ness, “Inscription of Gesture,” 6. 41

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd 326 1/12/11 12:55:07 PM

1 Zorn’s Grammatik der Tanzkunt (1887) which like

327

2 Saint-Leon’s system incorporates stick figures, and

3 V. I. Stepanov’s L’alphabet des mouvements du corps

B e t w e e n Te x t a n d P e r f o r m a n c e

4 humain (1882). Aleksandr Shirayev’s flipbooks and

5 puppet theaters, and Nijinsky’s manuscript score

6 of L’Après- midi d’un faune, are representative of

7 notational systems developed between the fin de

8 siècle and 1978. All these attempted to give a fuller

9 picture of the body’s actions in its sphere of activ-

10 ity, but none was adopted for common use. The

11 most influential, that of Rudolf van Laban, was not

12 in the ballet but the modern dance field. Kinetog-

s

13 raphy Laban or Labanotation was first formulated

Franko

14 in Schrifttanz (1928) and, though based in part on

15 Feuillet, Laban’s system analyzed and described

16 movement analysis in body-centered terms: weight,

17 space, time, flow (Figure 3). However influential it

18 became, though, not even Labanotation became

19 as broadly disseminated among dancers as musical

20 notation is among professional musicians. Dance

21 notation has been specialized and not the subject

22 of a universal professional literacy.

23 Modern dancers have entertained a mystique

24 of presentness that has made them mistrust visual

25 archiving. In the twentieth century, film was thus

26 not a significant medium of dance preservation.

27 Figure 3. “The notation of weight There is virtually no film of Isadora Duncan, and

28 level and the directions of none at all of Vaslav Nijinsky. Commercial film

movement” from Rudolf Laban’s

29 captured famous dancers rather haphazardly, and

Principles of Dance and Movement

30 Notation.

avant-garde film became an arena of experimenta-

31 tion that led to dance works made specifically for

32 film. Nonetheless, cinematography opened up the possibility of a nonscriptural

33 notation that came into its own, by the early 1970s, with video. Today, video

34 documentation of dance performance is practiced almost universally.

35 Despite the existence of numerous dance notational systems from the fif-

36 teenth to the twentieth century — one scholar has calculated that at least fifty-

37 three such systems exist — the transmission of dance has remained predominantly

38 a matter of oral tradition.16 Dance notation has therefore had significantly less

39

40 16. Ann Hutchinson Guest, “A Brief Survey of 53 Systems graphics: A Comparison of Dance Notation Systems from the

of Dance Notation,” National Centre for the Performing Fifteenth Century to the Present (New York: Gordon and

41 Arts Quarterly Journal 14.1 (March 1985): 1 – 14; Choreo- Breach, 1989).

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd 327 1/12/11 12:55:07 PM

impact on the modern artistic discipline of dance, and hence also on its academic 1

328

study, than musical notation has exerted on the discipline of musicology or than 2

dramatic texts have exerted on theater studies. Contemporary dance culture, by 3

COMMON KNOWLEDGE

which I mean essentially the living culture shared by dance practitioners, still 4

tends to conceive itself primarily in terms of oral culture; that is, as a culture 5

“with no knowledge whatsoever of writing or even of the possibility of writing.”17 6

Nevertheless, symbolic and visual forms of literacy permeate this oral tradition. 7

From Feuillet notation in the baroque era to Labanotation in the twentieth cen- 8

tury to movement capture in the digital age, the project of documenting dance 9

for future performance is clearly not a “dead letter.” 10

Even though the historical evolution of notation increasingly highlights 11

corporeality, an antinotational prejudice remains noticeable in much contem- 12

porary thinking about dance. As Laurence Louppe, for instance, has written: 13

“Dance is lived and traversed as a living presence; it has, in appearance, no need 14

for a symbolizing system that would be incompatible with experiential givens and 15

would reduce the sensible fabric of movement to an all-resuming graph, universal, 16

transferable from one place to another, from one textuality to another.”18 Accord- 17

ing to this view, no form of recording can be adequate for dance. By emphasizing 18

dance’s lived dimension and transient ethereal qualities, Louppe runs the risk of 19

making its preservation, in and by notation, impossible. Dance, it would seem, is 20

considered more alive (and more a live form) than other time-based arts. It is well 21

known that great modern figures of dance early in the twentieth century, such as 22

Duncan and Martha Graham, cultivated photography but rejected film. While 23

the still image was a medium with acceptable analogies for live performance, the 24

moving image was not. Has any other time-based art been so identified with its 25

own impermanence? 26

Given this state of affairs, it has been difficult if not impossible to think of 27

notation in relation to composition: notation has become associated with recon- 28

struction as a phenomenon of historical interest.19 But at the same time, the sense 29

of the score — and hence some notion of notation — seems to remain within the 30

body and the mind of the dancer as a danced possibility. That is to say, some form 31

of cognitive mapping takes the place of the idea of notation and takes root in the 32

dancer’s mind and body (if not on paper). Literal notation is not just secondary 33

but tertiary with respect to this sense of scoring that preexists notation in the 34

mind and the body, making of dance a form that places particular demands on 35

36

17. Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy (1982; London: 18. Laurence Louppe, “Imperfections in the Paper,” in 37

Routledge, 2002), 31. This tendency is backed up by Traces of Dance: Drawings and Notations of Choreographers, 38

eighteenth-century language-origin theories where the ed. Louppe, trans. Brian Holmes (Paris: Editions Dis

39

preliterate gesture is understood to be the repository of Voir, 1994), 9 – 33, at 9.

authentic physical expression. 40

19. We need a historical account of dance reconstruction

that parallels, but is not identical to, that of notation.

41

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd 328 1/12/11 12:55:07 PM

1 the performer. The desire to claim this exceptionalism for dance as a thoroughly

329

2 nontextual, preliterate and, in many cases, precritical event corresponds to the

3 will to claim that being organic is this art’s ultimate distinction. In this scenario,

B e t w e e n Te x t a n d P e r f o r m a n c e

4 the written sign is construed as the dancing body’s tomb.

5 Had dance notation become a universally legible form of textual record,

6 would the dancer not have used it as the musician uses a score? Do not the same

7 issues of style, technique, interpretation, and score-versus-performance practice

8 apply? Surely the answer is yes. So why must dance notation inevitably entail a

9 destructive confusion between itself and the living phenomenon it preserves and

10 denotes? Since we know that there are many varieties of notation — from let-

11 ters to words, to images, to abstract symbols — why should any and all forms of

12 inscription be inadequate media? Although choreography may have come about

s

13 by analogy with writing and notation (choreography being the writing of dance),

Franko

14 issues more deeply involving the body, its states, its therapies, and its “reasons”

15 that reason “does not know” may be primordially more basic to dance as an art

16 than is the idea of the finished work.20

17 The human body as instrument and/or medium raises issues that have

18 been ignored by classical aesthetics. How do we separate the body from the

19 dancing subject? To pose the question in this way is to suggest that, when Wil-

20 liam Butler Yeats asked how we can tell the dancer from the dance, his second

21 term — dance — signified not choreography but movement. The notion of cho-

22 reography — whether understood as writing or as a formulated plan — perturbs

23 this already fraught relation between body and subject, which haunts the notion

24 of medium in dance. What would it mean for the dancer to be her own medium?

25 When Stéphane Mallarmé says, “The dancer is not a woman who dances” but “a

26 poem disengaged from the whole writing apparatus,” he places the dancing body

27 in a postnotational era. Her dancing does not derive from writing or leave writ-

28 ing in its wake as a record. Instead her dancing acquires the generative power of

29 writing to produce images: “She is not a woman but a metaphor summarizing some

30 elementary aspect of our form, sword, cup, flower, etc.”21 The dancer becomes

31 a model for modernist poetics but is also derealized as a physical body before us

32 on stage.

33 Louppe interprets Mallarmé’s description of the dancer as “an unwritten

34 body writing” in order to explore the anomalous position of dance as an aesthetic

35 sign.22 In modernity, she explains,

36

37 20. For a recent study of the notion of the “work” in dance, land and Marshall Cohen (Oxford: Oxford University

38 See Frédéric Pouillaude, Le désoeuvrement chorégraphique. Press, 1983), 112.

Etude sur la notion d’oeuvre en danse (Paris: Vrin, 2009).

39 22. The phrase “unwritten body writing” is used by Mary

40 21. Stéphane Mallarmé, “Ballets” of “Crayonné au Lewis Shaw in her Performance in the Texts of Mallarmé:

Théâtre” in Oeuvres Complètes (Paris: Editions de la Plé- The Passage from Art to Ritual (University Park: Pennsyl-

41 iade, 1974), 304; also in What is Dance?, ed. Roger Cope- vania State University Press, 1993), 53.

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd 329 1/12/11 12:55:07 PM

a new stage emerges for dance, where it is less the sign than the very 1

330

process of signification that dissolves. This is not the formulation of 2

another language. It is a transformation of re-presentation itself. It is a

3

COMMON KNOWLEDGE

trajectory between the real and the sign. This trajectory is perturbed by

4

the presence of a living body, intervening as such. Representation sup-

poses the absence of the object, the absence of being. Here, life inhabits 5

what will never be its icon or index. Dance de-represents.23 6

7

In Louppe’s discussion of the impossibility of the danced sign to deposit itself on 8

record as such, we come across an unqualified rejection of dance as writing — 9

which suggests that what needs to be recovered is not choreography per se but 10

états de corps (as they are called in French dance theory) and the reception of these 11

states of the body by the eyes, ears, and mind.24 Claudia Jeshcke calls such recov- 12

ery performative knowledge: “Performative knowledge is considered to function as 13

nonverbal communication focusing on physical experience. In dance, it delivers 14

itself as pure body activities. (The term body activity, as I use it, designates the 15

way movements might have been conducted and how they might have been per- 16

ceived . . .).”25 This project tends to deauthorize notation to make way for “what 17

might have happened.” It is less a question of holding onto or recovering a par- 18

ticular choreographic work than of rediscovering states of the body that lay at the 19

core of the work and its reception. Without the recovery of those states, choreog- 20

raphy itself cannot be adequately recaptured and rearticulated.26 21

Since the 1970s, video has become the archival tool of choice, placing pos- 22

terity within reach of many choreographers who could not previously afford to 23

record their own work. More recently still, it has become a rehearsal method- 24

ology. Dancers have become adept at reversing the video image to reproduce 25

movement in their own bodies. This ability can obviate the oral tradition, in that 26

the dancer often does this work without the choreographer or director. Video 27

has introduced a regime of mimicry — removing from that term any necessarily 28

derogatory connotation — in the transmission and reproduction of dances. While 29

30

31

23. Louppe, “Imperfections in the Paper,” 10 – 11. See Mark Franko, “Repeatability, Reconstruction, and

Beyond,” in Dance as Text: Ideologies of the Baroque Body 32

24. The theory of états de corps gives impetus to the entire

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 133 – 52. 33

phenomenologically-based methodology of dance think-

Martin Puchner would probably maintain that Louppe

ing that evolved in the twentieth century.

is misreading Mallarmé: “Mallarmé does not look at the

34

25. Claudia Jeschke, “Notation Systems as Texts of Per- ballet in terms of either dancer or dance but pursues a 35

formative Knowledge,” Dance Research Journal 31.1 (Spring radically different interest that has nothing to do with 36

1999): 4. the dancer herself nor even with the dance, but takes the

dancing agent as a metaphor that operates by suggesting 37

26. I call that project construction rather than recon-

abstract forms and entities.” See Puchner, Stage Fright: 38

struction. Although I am more historicist than Louppe

Modernism, Anti- theatricality, and Drama (Baltimore:

and question the ideologies of modernism, the positions 39

Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 79. The recon-

I have articulated in Dance as Text on the inadequacies of 40

ciliation of these two competing discourses of modernism

historical dance reconstruction are aligned with the pri-

ority she gives to states of the body over choreography.

exceeds the limits of this essay. 41

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd 330 1/12/11 12:55:08 PM

1 this must be thought of as a reading skill, the medium through which it passes

331

2 is televisual. The body on display in this medium is not a sign, and the presence

3 of writing is obscured if it is present at all. With television, medium replaces

B e t w e e n Te x t a n d P e r f o r m a n c e

4 sign as a notational system. The televisual intervenes between the subject and

5 movement, and between the subject-to-subject relation presupposed by the oral

6 tradition.

7 As a critical concept in art history, medium replaces genre when technol-

8 ogy enters the realm of art (in photography, film, and later, video). Medium and

9 technology thus seem to presuppose one another in visual culture, in that the

10 technological instruments of visual representation transform the discourse of

11 genres (painting and sculpture) with respect to the new media. Nowhere is this

12 more the case than with the advent of television in the early 1950s in the United

s

13 States.27

Franko

14 Returning to Louppe’s reflections, we realize that her vision of dance is

15 determined by the relationship or nonrelationship of dance to language. She

16 begins from Mallarmé’s vision of the dancer as “an unwritten body writing”: “A

17 counter-writing,” as Louppe calls it, “the reverse of any grapheme, dance would

18 lead to the abolition of the Letter, opening up the supreme space of the poem. . . .”

19 And she concludes: “Only the organic can approach the threshold of this space

20 swept clear of signs.”28 If this contention is valid, and it surely remains valid for

21 modernists, then the recapture of the past would occur through the body and

22 bodily movement alone. Yet Mallarmé says that the body writes, which implies

23 that dissolving the sign into an organic corporeality is not quite what modernism

24 would require. If there is a poem in dance, then presumably meanings are at least

25 suggested by movements.

26 In postmodern dance, notation has tended toward personalized note tak-

27 ing. Compositional strategies, such as those of Merce Cunningham, that entail

28 chance procedures or structured improvisation (indeterminacy) dictate a form of

29 notation that is particular to his own strategy of dancemaking. Cunningham’s

30 Solo Suite in Space and Time (1953) was developed from notation that itself was

31 based on chance: “the spatial plan for the dance, which was the beginning proce-

32 dure, was found by numbering the imperfections on a piece of paper (one for each

33 of the dances) and by random action the order of the numbers.”29 In this case, a

34 dance was constructed through chance procedures that originated in the state of

35 the paper on which they were encoded. The importance of the paper’s imperfec-

36 tion brings chance in sync with the necessity of notating its structure. Some of

37 the work of Trisha Brown and William Forsythe involves the dancers themselves

38

27. See David Morley, “Television: Not So Much a Visual 29. Merce Cunningham, Changes: Notes on Choreogra-

39

Medium, More a Visual Object,” in Visual Culture, ed. phy, ed. Frances Starr (New York: Something Else Press,

40 Chris Jenks (London: Routledge, 1995), 170 – 89. 1968), n.p.

41 28. Louppe, “Imperfections in the Paper,” 10.

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd 331 1/12/11 12:55:08 PM

inscribing notation in the course of dancing.30 In Forsythe’s Human Writes, danc- 1

332

ers attempt to rewrite the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights with 2

writing implements held between their toes or in their mouths.31 Here, notation 3

COMMON KNOWLEDGE

occupies an intermediate position between writing and movement, suggesting a 4

form of graphic in its own right. Much dance notation of earlier periods already 5

has the quality of graphic presentation that is foregrounded in contemporary 6

choreographic experimentation. In these and related works, the concept of the 7

precedence of notation over movement is open to question, even as the idea of 8

dance as productive of notation is developed as an artistic reality. Notation as the 9

dance’s outcome rather than as its conception blurs the distinctions among move- 10

ment, writing, and visual signs that underwrite the traditional understanding of 11

dance notation.32 Notation is transformed into the indexical trace of movement, 12

blurring the distinction between dancing and drawing that is already implicit 13

in the idea of choreography as a form of writing. The result is a separate work 14

of graphic art that bears the traces of the dance, because it was produced by the 15

dancer’s movement. 16

The latest stage in this evolution of media relevant to dance is motion- 17

capture recording as a digital technology. Motion capture exists entirely within a 18

visual rather than a scriptural technology — within a digital rather than an ana- 19

logical code — which suggests an inorganic model closer to representation than 20

to derepresentation: the body itself is absent (a requirement of representation) 21

and is itself signified and analyzed by digital rendering.33 This rendering begins 22

with the dancer’s body, upon which optical sensors are placed to record the body’s 23

motion. The files used to translate this movement into images are derived from 24

biped geometry transformed into hand-drawn lines that render the movement 25

as that of a bodily form.34 Such is the case with Bill T. Jones’s Ghostcatching, a 26

motion-capture exercise in which we see the body itself as a scriptural trace-work 27

in motion. As Paul Kaiser has remarked of this process: 28

29

It’s true that motion capture is a process of subtraction, of taking away. 30

The infrared cameras have only eyes for the reflective markers worn by

31

the performing bodies, and not for the bodies themselves. Right away

we lose all vision of muscle and flesh, and with that all sense of effort as

32

33

30. See André Lepecki’s discussion of Trisha Brown’s “It’s 32. This problematic is explored in Noland and Ness, 34

a Draw/Live Feed,” in Exhausting Dance: Performance and Migrations of Gesture.

35

the Politics of Movement (New York: Routledge, 2006).

33. An excerpt is available on the DVD accompanying the 36

31. See Sabine Hushka, “Media-Bodies: Choreography as volume Envisioning Dance on Film and Video (New York:

Intermedial Thinking Through in the Work of William Routledge, 2002), part 32, track 17. 37

Forsythe,” in Dance Research Journal 42.1 (Summer 2010): 38

34. Paul Kaiser describes the six steps required for the

61 – 75; and Kendall Thomas, Thomas Keenan and Mark

transformation of Bill T. Jones’s dancing into the virtual 39

Franko, “Genesis and Concept of Human Writes,” Dance

performance of “Ghostcatching” in the catalog Ghost- 40

Research Journal 42.2 (Winter 2010): 3 – 12.

catching: A Virtual Dance Installation (New York: Cooper

Union School of Art, 1999).

41

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd 332 1/12/11 12:55:08 PM

1

333

2

3

B e t w e e n Te x t a n d P e r f o r m a n c e

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

s

13

Franko

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

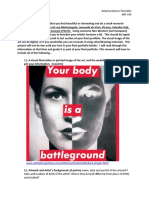

26 Figure 4. Bill T. Jones in Ghostcatching (1999). Courtesy of Paul Kaiser and

27 Shelley Eshkar.

28

29 well, since we can no longer make out the actual struggle and sweat of

the performing body. The face also vanishes and with it the expressions

30

that signal intention and feeling.35

31

32

Does not this thumbnail description of motion capture suggest in turn the sense

33

of medium as defined by Raymond Williams (“an intervening or intermediate

34

agency or substance”)?

35

Be that as it may, it seems that the peculiar integrity of the modernist body

36

is being left behind us. “Capture,” “reproduction,” and analysis are all terms that

37

are in the process of mediatizing the dancing body itself. The body derealizes

38

39

40 35. Paul Kaiser, “Frequently Pondered Questions,” in

Envisioning Dance on Film and Video (New York: Rout-

41 ledge, 2002), 108.

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd 333 1/12/11 12:55:08 PM

itself in embodying its own notation. For the body to be its own medium (in the 1

334

rigorous sense of the term), the body must itself become an image mediating 2

between subject and movement. Because the distinction in digital dance between 3

COMMON KNOWLEDGE

notation and performance is abolished, dance becomes synonymous with its own 4

visual analysis — a modernist trope applied to the “posthuman” body.36 5

Paul Kaiser and Shelley Eshkar of Riverbed multimedia explain further 6

that “Ghostcatching finds its place in the unexpected intersection of dance, draw- 7

ing, and computer composition. The work is made possible by advances in motion 8

capture. . . . The resulting data files reflect the position and rotation of the body 9

in motion, without preserving the performer’s mass or musculature. Thus, 10

movement is extracted from the performer’s body.” Most provocatively, they ask: 11

“What is the human movement in the absence of the body? Can the drawn line 12

carry the rhythm, weight, and intent of physical movement? What kind of dance 13

do we conceive in this ghostly place, where enclosures, entanglements, and reflec- 14

tions vie with the will to break free?”37 It is possible that dance notation, and cho- 15

reography itself as a project, have always resided on the indistinct border between 16

writing and drawing (Figure 4). If we think of choreography as writing, it may 17

be because the very concept of dance depends in some measure on the notion of 18

a trace in which the body, language as sign, and the gesture of drawing coincide 19

as the very definition of what dancing means. 20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

36. I borrow this phrase from Kent de Spain, “Dance and 37. “Choreo-graphics: Riverbed’s Virtual Dances,” After- 40

Technology: A Pas de Deux for Post-Humans,” Dance images 6.2 (Summer 1999): 4.

Research Journal 32.1 (Summer 2000): 2 – 17. 41

CK172_09_Franko_1pp.indd

View publication stats 334 1/12/11 12:55:08 PM

Вам также может понравиться

- Before Your Eyes, Lisa NelsonДокумент11 страницBefore Your Eyes, Lisa NelsonAnaRita TeodoroОценок пока нет

- La instalación como dispositivo comunicacional: el caso Misión/Misiones de Cildo Meireles en la I Bienal del MercosurДокумент8 страницLa instalación como dispositivo comunicacional: el caso Misión/Misiones de Cildo Meireles en la I Bienal del MercosurPedroDalvaradoОценок пока нет

- Synchronousobjects For One Flat Thing, Reproduced by William ForsytheДокумент4 страницыSynchronousobjects For One Flat Thing, Reproduced by William Forsythegoo99Оценок пока нет

- We Can't Promise To Do More Than Experiment.': Ana JanevskiДокумент10 страницWe Can't Promise To Do More Than Experiment.': Ana Janevskidedanza128Оценок пока нет

- Regseeker - Quick Reference Guide: Changing The Language InterfaceДокумент7 страницRegseeker - Quick Reference Guide: Changing The Language Interfacededanza128Оценок пока нет

- Synchronousobjects For One Flat Thing, Reproduced by William ForsytheДокумент4 страницыSynchronousobjects For One Flat Thing, Reproduced by William Forsythegoo99Оценок пока нет

- Loudness Log File AnalysisДокумент11 364 страницыLoudness Log File Analysisdedanza128Оценок пока нет

- HistoryДокумент1 страницаHistorydedanza128Оценок пока нет

- HistoryДокумент1 страницаHistorydedanza128Оценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Music of AustraliaДокумент29 страницMusic of AustraliaHeaven2012Оценок пока нет

- Artwork CritiqueДокумент1 страницаArtwork CritiqueJohn Gabriel Guillarte CoronadoОценок пока нет

- Grade 10 Literature and Indigenous Story-TellingДокумент5 страницGrade 10 Literature and Indigenous Story-Tellingapi-644699996Оценок пока нет

- The Globe and Mail 4otober 19 - 21 Key Raaces AcrossДокумент52 страницыThe Globe and Mail 4otober 19 - 21 Key Raaces AcrossNelsonynelsonОценок пока нет

- My Most Memorable Experience During This Covid-19 PandemicДокумент2 страницыMy Most Memorable Experience During This Covid-19 PandemicMarwin Odita0% (1)

- Moonlight Densetsu TUSOДокумент20 страницMoonlight Densetsu TUSOKhang QuachОценок пока нет

- An Easy Guide to Literary CriticismДокумент43 страницыAn Easy Guide to Literary Criticismcity cyber67% (3)

- Analytical EssaysДокумент2 страницыAnalytical Essaysafabkgddu100% (2)

- GMA Channel 7 Network CETV Programs Paved The Way For Children Who Want To Learn and Enjoy at The Same TimeДокумент7 страницGMA Channel 7 Network CETV Programs Paved The Way For Children Who Want To Learn and Enjoy at The Same TimeJohn Vincent DelacruzОценок пока нет

- Slump Test: Lab ReportДокумент5 страницSlump Test: Lab ReportRaymart Calano RubenОценок пока нет

- Multimedia Module 1 PDFДокумент13 страницMultimedia Module 1 PDFVarun MohandasОценок пока нет

- Publishers Weekly - April 10, 2023Документ86 страницPublishers Weekly - April 10, 2023Lody BambinoОценок пока нет

- Modern Poetry: Compact Performer - Culture & LiteratureДокумент8 страницModern Poetry: Compact Performer - Culture & Literatureclara ostanoОценок пока нет

- Arts 7 - Q3 - Module 4 - PreciousTreasuresoftheSouthДокумент30 страницArts 7 - Q3 - Module 4 - PreciousTreasuresoftheSouthDIANE BORROMEO,Оценок пока нет

- Cute Summer CraftsДокумент4 страницыCute Summer CraftsDebbieОценок пока нет

- Cinema À La Carte (Catálogo)Документ237 страницCinema À La Carte (Catálogo)Silvania Espíndola100% (1)

- Mp3 CollectionДокумент274 страницыMp3 CollectionOliver QueenОценок пока нет

- Vary Sentence StructureДокумент7 страницVary Sentence StructureAlka MarwahОценок пока нет

- Comic Medievalism - Laughing at The Middle Ages-D. S. Brewer (2014)Документ222 страницыComic Medievalism - Laughing at The Middle Ages-D. S. Brewer (2014)William Blanc100% (1)

- HG Target AudienceДокумент2 страницыHG Target Audienceapi-2562232220% (1)

- Art History Assignment 39596Документ3 страницыArt History Assignment 39596api-548174707Оценок пока нет

- 21 STДокумент11 страниц21 STLiezel Desaporado VendorОценок пока нет

- Bach - Partita in e Major N 3 (Violin)Документ9 страницBach - Partita in e Major N 3 (Violin)Arturo Licantropical ValdezОценок пока нет

- Week One Electronic Music Lesson PlansДокумент20 страницWeek One Electronic Music Lesson Plansapi-476747299Оценок пока нет

- 12th Rajasthani Miniature Painting-2Документ33 страницы12th Rajasthani Miniature Painting-2sandy BoiОценок пока нет

- Rayhan Ahmad Haslan B.Inggris LMДокумент2 страницыRayhan Ahmad Haslan B.Inggris LMrayhan haslan0% (1)

- Sok ModulesДокумент100 страницSok ModulesKrista SpiteriОценок пока нет

- The Impossibility of Representation: A Semiotic Museological Reading of Aboriginal Cultural DiversityДокумент16 страницThe Impossibility of Representation: A Semiotic Museological Reading of Aboriginal Cultural DiversityDavid SantosОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions: Quarter 2 - Module 9 Different Contemporary Art Techniques and PerformanceДокумент25 страницContemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions: Quarter 2 - Module 9 Different Contemporary Art Techniques and PerformanceGrace06 Labin100% (7)

- 21st Century Literature Module 7Документ4 страницы21st Century Literature Module 7Fionah HistorilloОценок пока нет