Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Mental Health Problems and Social Media Exposure During COVID-19 Outbreak

Загружено:

ieykatalibОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Mental Health Problems and Social Media Exposure During COVID-19 Outbreak

Загружено:

ieykatalibАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

PLOS ONE

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Mental health problems and social media

exposure during COVID-19 outbreak

Junling Gao ID, Pinpin Zheng, Yingnan Jia, Hao Chen, Yimeng Mao, Suhong Chen,

Yi Wang, Hua Fu, Junming Dai*

School of Public Health, Fudan University, Fudan Institute of Health communication, Shanghai, China

* jmdai@fudan.edu.cn

a1111111111

a1111111111

a1111111111

Abstract

a1111111111 Huge citizens expose to social media during a novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) out-

a1111111111

broke in Wuhan, China. We assess the prevalence of mental health problems and examine

their association with social media exposure. A cross-sectional study among Chinese citi-

zens aged�18 years old was conducted during Jan 31 to Feb 2, 2020. Online survey was

used to do rapid assessment. Total of 4872 participants from 31 provinces and autonomous

OPEN ACCESS

regions were involved in the current study. Besides demographics and social media expo-

Citation: Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, Chen H, Mao Y, sure (SME), depression was assessed by The Chinese version of WHO-Five Well-Being

Chen S, et al. (2020) Mental health problems and

Index (WHO-5) and anxiety was assessed by Chinese version of generalized anxiety disor-

social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak.

PLoS ONE 15(4): e0231924. https://doi.org/ der scale (GAD-7). multivariable logistic regressions were used to identify associations

10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 between social media exposure with mental health problems after controlling for covariates.

Editor: Kenji Hashimoto, Chiba Daigaku, JAPAN The prevalence of depression, anxiety and combination of depression and anxiety (CDA)

was 48.3% (95%CI: 46.9%-49.7%), 22.6% (95%CI: 21.4%-23.8%) and 19.4% (95%CI:

Received: March 4, 2020

18.3%-20.6%) during COVID-19 outbroke in Wuhan, China. More than 80% (95%CI:80.9%-

Accepted: April 4, 2020

83.1%) of participants reported frequently exposed to social media. After controlling for

Published: April 16, 2020 covariates, frequently SME was positively associated with high odds of anxiety (OR = 1.72,

Peer Review History: PLOS recognizes the 95%CI: 1.31–2.26) and CDA (OR = 1.91, 95%CI: 1.52–2.41) compared with less SME. Our

benefits of transparency in the peer review findings show there are high prevalence of mental health problems, which positively associ-

process; therefore, we enable the publication of

ated with frequently SME during the COVID-19 outbreak. These findings implicated the gov-

all of the content of peer review and author

responses alongside final, published articles. The ernment need pay more attention to mental health problems, especially depression and

editorial history of this article is available here: anxiety among general population and combating with “infodemic” while combating during

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 public health emergency.

Copyright: © 2020 Gao et al. This is an open

access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original

author and source are credited.

Introduction

Data Availability Statement: All relevant data are

within the manuscript and its Supporting A public health emergency of international concern-novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

Information files. outbroke[1] in Wuhan, China on 31 December 2019, which has been spread to 24 countries

Funding: Junling Gao was funded by National key

outside of China and infected 37,558 patients globally (37,251 in China) by 9 February 2020[2].

R&D Program of China (grant no. The outbreak of COVID-19 in China has caused mental health problems among the public in

2018YFC2002000 & 2018YFC2002001) and China[3] and Japan[4] and medical workers in Wuhan[5]. The National Health Commission

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 April 16, 2020 1 / 10

PLOS ONE Mental health problems during COVID-19 outbreak

National Natural Science Foundation of China has released guideline for local authorities to promote psychological crisis intervention for

(grant no. 71573048). The funders had no role in patients, medical personnel, people under medical observation and civilians during the

study design, data collection and analysis, decision

COVID-19 outbreak[6]. However, what type of mental disorders are prevalent and how they

to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

distribute among population are not know. So, a rapid assessment of outbreak-associated men-

Competing interests: The authors have declared tal disorders for both civilians and health care workers, is needed[7].

that no competing interests exist.

The official departments strive to improve the public’s awareness of prevention and interven-

tion strategies by providing daily updates about surveillance and active cases on websites and

social media[3]. Besides, many self-media and netizens also release and transfer related infor-

mation on social media, such as WeChat and Weibo. Social media may lead to (mis)informa-

tion overload[8,9], which in turn may cause mental health problems. WHO pointed out that

identifying the underlying drivers of fear, anxiety and stigma that fuel misinformation and

rumour, particularly through social media[10]. Previous studies indicated that indirect exposure

to mass trauma through the media can increase the initial rates of post-traumatic stress disorder

(PTSD) symptoms[11]. A previous study also shown social media exposure may positively

related to forming risk perceptions during the MERS outbreak in South Korea[12]. But there

was no study to examine the association between social media exposure and mental health

problems. So, the current study aims to describes the prevalence and distribution of two major

mental disorders-anxiety and depression among Chinese population [13], and examine their

associations with social media exposure by rapid assessment during COVID-19 outbreak.

Materials and methods

Design and participants

This cross-sectional study was online conducted during Jan 31 to Feb 2, 2020. Chinese citizens

aged�18 years old were invited to participate online survey though Wenjuanxing platform

(https://www.wjx.cn/app/survey.aspx). In total, 5,851 participants took part in the survey.

After removing the participants without completed questionnaires, 4872 participants from 31

provinces and autonomous regions were involved in the current study. A written consent in

the first section of online survey was given to all participants before filling the questionnaire.

This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fudan University, School

of Public Health(IRB#2020-01-0800).

Measurements

Mental health problems. According to a previous study two major mental disorders-

depression and anxiety [13] were assessed in the current study. Depression was assessed by

The Chinese version of WHO-Five Well-Being Index (WHO-5)[14], which consists of five

positively worded items that reflect the presence or absence of well-being rather than depres-

sive symptomatology. Participants are asked to report the presence of these positive feelings in

the last 2 weeks on a 6-point scale ranging from all of the time (5 points) to at no time (0

points). A summed score below 13 indicates depression[14]. Anxiety was assessed by Chinese

version of generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7)[15,16], which consists 7 symptoms. Par-

ticipants were asked how often they were bothered by each symptom during the last 2 weeks.

Response options were “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every

day,” scored as 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. A score of 10 or greater represents a reasonable cut

point for identifying cases of anxiety[15,16](S1 Table).

Social media exposure (SME). Social media exposure was measured by asking how often

respondents during the past week were exposed to news and information about COVID-19 on

social media, such as Sina weibo, Zhihu, Douban, WeChat and etc (S1 Table). Response

options were “never”, “once in a while”, “sometimes”, “often” and “very often”. Because of less

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 April 16, 2020 2 / 10

PLOS ONE Mental health problems during COVID-19 outbreak

proportion of “never”, so we recoded social media exposure into “less” (“never” and “once in a

while”), “sometimes” and “frequently” (“often” and “very often”).

Covariates. The following covariates were included in this study: gender, age (10-year cate-

gories), educational level (junior high school, senior high school, college and master and higher),

marital status (recoded into married and other [including unmarried, divorced, and widowed]),

self-rated health (categorized as excellent, very good and good or low), occupation(students/

retired, health care worker and others), cities(Wuhan and others), area(urban and rural).

Statistical analyses

The χ2 /trend tests were used to determine the prevalence of depression, anxiety and combina-

tion of depression and anxiety by categorical variables including social media exposure and

covariates. Logistic regression analyses were used to explain the association between the preva-

lence of depression, anxiety and combination of depression and anxiety and SME after con-

trolling for covariates. We estimated the adjusted ORs and their 95% confidence intervals

(CIs) of independent variables for frailty. The STATA version 13.0 program (StataCorp LP.,

College Station, TX, USA) was used to carry out all analyses.

Results

Social media exposure

Of all 4827 participants, the mean age of was 32.3±10.0 years (ranged 18–85), the proportion

of “less”, “sometimes”, and “frequently” of SME was 8.8%(95%CI:8.0%-9.6%), 9.2%(95%

CI:8.4%-10.0%) and 82.0%(95%CI:80.9%-83.1%). As shown in Table 1, more than 60% of

them (67.7%) were women, and most (47.9%) were aged 21–30 years. Many participants

(62.2%) had achieved a college education, more than half of them were married. Only 5.2% of

them were health care workers and 2.7% were from Hubei province, and 81.2% were from

urban area. Most of them reported “excellent” (43.9%) or “very good” (45.6%) health.

Univariate analyses found that the proportion of frequently SME among men (78.4%, 95%

CI: 76.3%-80.3%) was lower than among women (83.8%, 95%CI: 82.4%-85.0%), the propor-

tion of frequently SME among youngers (aged -30 years) was higher than among elders (aged

41- years). Participants with low education (middle school and high school) had lower propor-

tion of frequently SME than who with high education (college and master). Participants who

are students or retired had higher proportion of frequently SME. The proportion of SME was

not different between participants from Hubei province and others, however, participants

from rural area reported higher proportion of frequently SME than who from urban area. Par-

ticipants who were excellent health had higher proportion of frequently SME than others.

Depression and SME

The prevalence of depression was 48.3% (95%CI: 46.9%-49.7%). As shown Fig 1, Multivariate

analyses found that the adjusted odds of depression were greater among who age 21–30 years

(OR = 1.49, 95%CI: 1.12–1.99) and 31–40 years (OR = 1.54, 95%CI: 1.11–2.14) compared with

who aged �20 years, and lower among those with college (OR = 0.69, 95%CI: 0.53–0.91) and mas-

ter (OR = 0.46, 95%CI: 0.63–0.85) education than those with middle school. Participants from

Hubei province had no higher adjusted odds than those from other province (OR = 1.06, 95%CI:

0.75–1.52), but those from rural area had lower adjusted odds (OR = 0.74, 95%CI: 0.64–0.87) than

those from urban area. The decrease of self-rated health significantly accompanied the increased

odds of depression. About the focus of this study, higher frequency of SME was insignificantly

positively associated with the adjusted odds of depression after controlling for all covariates.

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 April 16, 2020 3 / 10

PLOS ONE Mental health problems during COVID-19 outbreak

Table 1. Participants characteristic and social media exposure.

N(%) Social media exposure P value

Less Sometimes Frequently

Overall 4827(100) 424(8.8:8.0–9.6) 444(9.2:8.4–10.0) 3959(82.0:80.9–83.1)

Gender

Male 1560(32.3) 161(10.3:8.9–11.9) 176(11.3:9.8–13.0) 1223(78.4:76.3–80.3) <0.001

Female 3267(67.7) 263(8.1:7.2–9.0) 268(8.2:7.3–9.2) 2736(83.8:82.4–85.0)

Age(years)

-20 256(5.3) 11(4.3:2.2–7.6) 14(5.5:3.0–9.0) 231(90.2:85.9–93.6) <0.001

21–30 2312(47.9) 120(5.2:4.3–6.2) 150(6.5:5.5–7.6) 2042(88.3:86.9–89.6)

31–40 1288(26.9) 124(9.6:8.1–11.4) 144(11.2:9.5–13.0) 1020(79.2:76.9–81.4)

41–50 749(15.5) 120(16.0:13.5–18.8) 109(14.6:12.1–17.3) 520(69.4:66.0–72.7)

51- 222(4.6) 49(22.1:16.8–28.1) 27(12.2:8.2–17.2) 146(65.8:59.1–72.0)

Education

Middle school 257(5.3) 45(17.5:13.1–22.7) 30(11.7:8.0–16.2) 182(70.8:64.8–76.3) <0.001

High School 782(16.2) 85(10.9:8.8–13.3) 96(12.3:10.1–14.8) 601(76.9:73.7–79.8)

College 3002(62.2) 224(7.5:6.5–8.5) 256(8.5:7.6–9.6) 2522(84.0:82.6–85.3)

Master 786(16.3) 70(8.9:7.0–11.1) 62(7.9:6.1–10.0) 654(83.2:80.4–85.8)

Marriage

Married 2607(54.0) 314(12.0:10.8–13.5) 306(11.7:10.5–13.0) 1987(76.2:74.5–77.8) <0.001

No married 2220(46.0) 110(5.0:4.1–5.9) 138(6.2:5.2–7.3) 1972(88.8:87.4–90.1)

Occupation

Students/retired 1189(24.6) 84(7.1:5.7–8.7) 70(5.9:4.7–7.4) 1035(87.1:85.0–88.9) <0.001

Health care workers 251(5.2) 25(10.0:6.5–14.4) 23(9.2:5.9–13.4) 203(80.9:75.5–85.6)

others 3387(70.2) 315(9.3:8.3–10.3) 351(10.4:9.4–11.4) 2721(80.3:79.0–81.7)

Cities

Hubei 130(2.7) 7(5.4:2.2–10.8) 13(10.0:5.4–16.5) 110(84.6:77.2–90.3) 0.375

Others 4697(97.3) 417(8.9:8.1–9.7) 431(9.2:8.4–10.0) 3849(82.0:80.8–83.0)

Area

Urban 3920(81.2) 363(9.3:8.4–10.2) 371(9.5:8.6–10.4) 3186(81.3:80.0–82.5) 0.015

Rural 907(18.8) 61(6.7:5.2–8.6) 73(8.1:6.4–10.0) 773(85.2:82.7–87.5)

Self-rate health

Excellent 2118(43.9) 173(8.2:7.0–9.4) 179(8.5:7.3–9.7) 1766(83.4:81.7–84.9) 0.020

Very good 2202(45.6) 191(8.7:7.5–9.9) 209(9.5:8.3–10.8) 1802(81.8:80.2–83.4)

Good/general/poor 507(10.5) 60(11.8:9.1–15.0) 56(11.1:8.5–14.1) 391(77.2:73.2–80.7)

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924.t001

Anxiety and SME

The prevalence of anxiety was 22.6% (95%CI: 21.4%-23.8%). As shown Fig 2, Multivariate

analyses found that that the adjusted odds of depression were greater among those aged 31–40

years (OR = 1.63, 95%CI: 1.06–2.51) compared with those aged -20 years, and lower among

those with college (OR = 0.40, 95%CI: 0.30–0.53) and master (OR = 0.31, 95%CI: 0.22–0.44)

education than those with middle school. The adjusted odds of depression among unmarried

participants (OR = 0.80, 95%CI: 0.66–0.96) was lower than among married ones. Participants

from other provinces had no higher adjusted odds (OR = 0.49, 95%CI: 0.33–0.71) than those

from Hubei province. The adjusted odds of depression were greater among those with good/

general/poor SRH (OR = 1.77, 95%CI: 1.41–2.21) compared with those with excellent SRH.

About the focus of this study, frequently SME can increase the adjusted odds (OR = 1.72, 95%

CI: 1.31–2.26) of anxiety compared with less SME after controlling for all covariates.

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 April 16, 2020 4 / 10

PLOS ONE Mental health problems during COVID-19 outbreak

Fig 1. Prevalence of depression and relevant factors.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924.g001

Combination of depression and anxiety and SME

The prevalence of combination of depression and anxiety (CDA) was 19.4% (95%CI: 18.3%-

20.6%). As shown Fig 3, Multivariate analyses found that that the adjusted odds of depression

were greater among those aged 31–40 years (OR = 1.69, 95%CI: 1.07–2.68) compared with

those aged -20 years, and lower among those with college (OR = 0.50, 95%CI: 0.37–0.68) and

master (OR = 0.40, 95%CI: 0.28–0.57) education than those with middle school. The adjusted

odds of depression among unmarried participants (OR = 0.79, 95%CI: 0.64–0.97) was lower

than among married ones. The adjusted odds of depression were greater among those with

good/general/poor SRH (OR = 1.77, 95%CI: 1.41–2.21) compared with those with excellent

SRH. About the focus of this study, frequently SME can increase the adjusted odds (OR = 1.91,

95%CI: 1.52–2.41) of CDA compared with less SEM after controlling for all covariates.

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 April 16, 2020 5 / 10

PLOS ONE Mental health problems during COVID-19 outbreak

Fig 2. Prevalence of anxiety and relevant factors.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924.g002

Discussion

The latest national sample indicated the prevalence of any disorder (excluding dementia), anx-

iety disorders and depressive disorders was 16.6% (95%CI: 13.0–20.2), 7.6% (95%CI: 6.3–8.8)

and 6.9% (95%CI: 6.6–7.2) in China[13]. Comparing with this national data, the current cross-

sectional study found that much higher prevalence of depression (48.3%, 95%CI: 46.9%-

49.7%), anxiety (22.6%, 95%CI: 21.4%-23.8%) and CDA (19.4%, 95%CI: 18.3%-20.6%) during

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 April 16, 2020 6 / 10

PLOS ONE Mental health problems during COVID-19 outbreak

Fig 3. Prevalence of combination of depression and anxiety and relevant factors.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924.g003

COVID-19 outbroke in Wuhan, China. These findings are consistent with the previous stud-

ies’ that exposing public health emergency can cause public mental health problems, such as

Wenchuan and Lushan earthquakes[17], 2014 Ebola Outbreak[7,18], and SARS[19].

Social media is one of main channels updating the COVID-19 information[3]. This study

also found that 82.0% of participants frequently expose them to social media, and frequently

SME associated high odds of anxiety and CDA, which is consistent with previous studies [11].

there may be two reasons explaining the association between frequently SME and mental health.

During COVID-19 outbreak, disinformation and false reports about the COVID-19 have bom-

barded social media and stoked unfounded fears among many netizens[20], which may confuse

people and harm people’s mental health[9]. Besides, many citizens expressed their negative feel-

ings, such as fear, worry, nervous, anxiety et al. on social media, which are contagious social net-

work[21,22]. So, WHO’s ‘infodemics’ team is working hand in glove with countries’

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 April 16, 2020 7 / 10

PLOS ONE Mental health problems during COVID-19 outbreak

communications department to deliver information to a broader public audience[23]. Finally,

we also found that SME was not different between participants from Hubei province and others,

but the formers faced higher odds of anxiety. It indicated that participants from Hubei prov-

ince- the infectious focus directly expose to public health emergency, and may suffer more men-

tal health problemes[17,19]. Compared with the control measures taken by other cities, Wuhan

have sealed off the city from all outside contact to stop the spread of the COVID-19. As the pre-

vention and control measures called new standard by WHO[24], the lockdown of Wuhan is a

very effective way to interrupt the transmission of the virus, however, the strictest measures in

Wuhan might lead to more serious mental health problems of local people.

Some potential limitations should be noted in this study. First, this is a cross-sectional

study, so it is difficult to accurately elucidate causal relationships between SME and mental

health. Additional longitudinal studies, such as cohort studies or nested case-control studies,

are essential in the future. Although large sample, the survey was conducted online, which is

suitable for rapid assessment, so some respondent bias, such as few elder citizens’ participa-

tion, may have affected the results. Finally, although we did control for many covariates, we

cannot exclude the possibility of some residual confounding caused by unmeasured factors.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings show there are high prevalence of mental health problems, which

positively associated with frequently SME during the COVID-19 outbreak. These findings

implicated the government need pay more attention to mental health among general popula-

tion while combating with COVID-19. Fortunately, The China government have provided

mental health services by varied channel including hotline, online consultation, online course

and outpatient consultation[6], but more attention should be paid to depression and anxiety.

The next implication is to combat with “infodemic” by monitoring and filtering out false infor-

mation and promoting accurate information though cross-section collaborations.

Supporting information

S1 Table.

(DOCX)

S1 Data.

(XLS)

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Junling Gao, Hua Fu, Junming Dai.

Data curation: Pinpin Zheng, Yingnan Jia, Hao Chen, Yimeng Mao, Suhong Chen, Yi Wang.

Formal analysis: Junling Gao.

Funding acquisition: Junling Gao.

Investigation: Pinpin Zheng, Yingnan Jia, Hao Chen, Yimeng Mao, Suhong Chen, Yi Wang.

Methodology: Junling Gao, Yingnan Jia, Junming Dai.

Supervision: Hua Fu.

Writing – original draft: Junling Gao.

Writing – review & editing: Pinpin Zheng, Yingnan Jia, Hua Fu, Junming Dai.

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 April 16, 2020 8 / 10

PLOS ONE Mental health problems during COVID-19 outbreak

References

1. WHO. WHO Director-General’s statement on IHR Emergency Committee on Novel Coronavirus (2019-

nCoV). https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-statement-on-ihr-emergency-

committee-on-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov). (accessed Feb 9, 2020)

2. WHO. Novel Coronavirus(2019-nCoV) Situation Report–20. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/

coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200209-sitrep-20-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=6f80d1b9_4. (accessed Feb 9,

2020)

3. Bao Y, Sun Y, Meng S, Shi J, Lu L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: address mental health care to empower soci-

ety. The Lancet. Feb 07,2020. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30309-3.

4. Shigemura J, Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, Kurosawa M, Benedek DM. Public responses to the novel

2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: mental health consequences and target populations. Psychia-

try Clin Neurosci. Feb 08, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12988 PMID: 32034840

5. Kang L, Li Y, Hu S, et al. The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019

novel coronavirus. The Lancet Psychiatry. Feb 05, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)

30047-X. (accessed Feb 11, 2020)

6. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Guideline for psychological crisis inter-

vention during 2019-nCoV. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-01/27/content_5472433.htm.

(accessed Feb 10, 2020)

7. Shultz JM, Baingana F, Neria Y. The 2014 Ebola Outbreak and Mental Health: Current Status and Rec-

ommended Response. JAMA 2015; 313(6): 567–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.17934 PMID:

25532102

8. Bontcheva K, Gorrell G, Wessels B. Social Media and Information Overload: Survey Results. arXiv e-

prints, 2013. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2013arXiv1306.0813B (accessed June 01, 2013).

9. Florian Roth, Brönnimann G. Focal Report 8: Risk Analysis Using the Internet for Public Risk Communi-

cation. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256126259. (accessed Feb 12, 2020)

10. WHO. COVID 2019 PHEIC Global research and innovation forum: towards a research roadmap.

https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/12-02-2020-world-experts-and-funders-set-priorities-for-covid-

19-research. (accessed Feb 14, 2020)

11. Neria Y, Sullivan GM. Understanding the mental health effects of indirect exposure to mass trauma

through the media. JAMA 2011; 306(12): 1374–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1358 PMID:

21903818

12. Choi D-H, Yoo W, Noh G-Y, Park K. The impact of social media on risk perceptions during the MERS

outbreak in South Korea. Computers in Human Behavior 2017; 72: 422–31.

13. Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemio-

logical study. Lancet Psychiatry 2019; 6(3): 211–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30511-X

PMID: 30792114

14. WHO Collaborating Centre in Mental Health. Chinese version of the WHO-Five Well-Being Index. http://

www.who-5.org. (accessed Feb 10, 2020)

15. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disor-

der: the GAD-7. Archives of internal medicine 2006; 166(10): 1092–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.

166.10.1092 PMID: 16717171

16. Xu WF PY, Chen BQ. Assessment of Anxiety and Depression by Self-rating Scales of GAD-7 and

PHQ-9 in Cardiovascular Outpatients. World Latest Medicine Information (Electronic Version), 2018,

18(16):12–14. (in Chinese)

17. Xie Z, Xu J, Wu Z. Mental health problems among survivors in hard-hit areas of the 5.12 Wenchuan and

4.20 Lushan earthquakes. J Ment Health 2017; 26(1): 43–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2016.

1276525 PMID: 28084103

18. Ji D, Ji YJ, Duan XZ, et al. Prevalence of psychological symptoms among Ebola survivors and health-

care workers during the 2014–2015 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone: a cross-sectional study. Oncotar-

get 2017; 8(8): 12784–91. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.14498 PMID: 28061463

19. Mak IW, Chu CM, Pan PC, Yiu MG, Chan VL. Long-term psychiatric morbidities among SARS survi-

vors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2009; 31(4): 318–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.03.001

PMID: 19555791

20. Xinhua. Bat soup, biolab, crazy numbers . . . Misinformation "infodemic" on novel coronavirus exposed.

http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-02/04/c_138755586.htm. (accessed Feb 15, 2020)

21. Kramer AD, Guillory JE, Hancock JT. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion

through social networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111(24): 8788–90. https://doi.org/10.1073/

pnas.1320040111 PMID: 24889601

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 April 16, 2020 9 / 10

PLOS ONE Mental health problems during COVID-19 outbreak

22. Niederkrotenthaler T, Stack S, Till B, et al. Association of Increased Youth Suicides in the United States

With the Release of 13 Reasons Why. JAMA Psychiatry 2019; 76(9): 933–40.

23. WHO. Director-General’s remarks at the media briefing on 2019 novel coronavirus on 8 February 2020.

https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-

novel-coronavirus—8-february-2020. (accessed Feb 15, 2020)

24. WHO. Emergencies Coronavirus EC Meeting. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-

general-s-statement-on-the-advice-of-the-ihr-emergency-committee-on-novel-coronavirus. (accessed

Feb 15, 2020)

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 April 16, 2020 10 / 10

Вам также может понравиться

- MRCP 1 NeurologyДокумент16 страницMRCP 1 NeurologyKarrar A. AlShammaryОценок пока нет

- The Heart Meridian - Ruler of EmotionsДокумент4 страницыThe Heart Meridian - Ruler of Emotionsmanket59Оценок пока нет

- Single DentureДокумент37 страницSingle DentureDentist Dina SamyОценок пока нет

- Impact of Covid 19 On Mental HealthДокумент18 страницImpact of Covid 19 On Mental HealthNada ImranОценок пока нет

- Nursing Case Study Acute GastroДокумент8 страницNursing Case Study Acute GastroEdilyn BalicaoОценок пока нет

- Bicol Medical Center Department of Surgery: AppendicitisДокумент60 страницBicol Medical Center Department of Surgery: AppendicitisHenry Bona100% (1)

- A Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress Among Indonesian Residents During The COVID-19 PandemicДокумент8 страницA Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress Among Indonesian Residents During The COVID-19 PandemicIJPHSОценок пока нет

- Association of Social Media Use With Mental Health Conditions of Nonpatients During The COVID-19 Outbreak-Insights From A National Survey StudyДокумент15 страницAssociation of Social Media Use With Mental Health Conditions of Nonpatients During The COVID-19 Outbreak-Insights From A National Survey StudycorrietheinfodesignerОценок пока нет

- The Lancet: Mental Health Problems and Social Media Exposure During COVID-19 OutbreakДокумент21 страницаThe Lancet: Mental Health Problems and Social Media Exposure During COVID-19 OutbreakJhuul ContrerasОценок пока нет

- English Abstract PDFДокумент2 страницыEnglish Abstract PDFDeyb ErmacОценок пока нет

- A Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress AmonДокумент3 страницыA Nationwide Survey of Psychological Distress AmonTesis LabОценок пока нет

- Prevalence and Socio Demographic Correlates of Psychological Health Problems in Chinese Adolescents During The Outbreak of COVID 19Документ10 страницPrevalence and Socio Demographic Correlates of Psychological Health Problems in Chinese Adolescents During The Outbreak of COVID 19Vitória AlvesОценок пока нет

- Psychological Status and Behavior Changes of The Public During The COVID-19 Epidemic in ChinaДокумент11 страницPsychological Status and Behavior Changes of The Public During The COVID-19 Epidemic in ChinaSwastik MahapatraОценок пока нет

- Zhou2020 - Article - PrevalenceAndSocio-demographic TESISДокумент10 страницZhou2020 - Article - PrevalenceAndSocio-demographic TESISroger alcantaraОценок пока нет

- A Longitudinal Study On The Mental Health of General Population During The COVID-19 Epidemic in ChinaДокумент35 страницA Longitudinal Study On The Mental Health of General Population During The COVID-19 Epidemic in ChinaArgenis SalinasОценок пока нет

- Journal Pone 0233410Документ10 страницJournal Pone 0233410JuanCamiloОценок пока нет

- Social y Mental WuhanДокумент10 страницSocial y Mental WuhanMilton MurilloОценок пока нет

- Mental Health Problems and Correlates Among 746 217 College Students During The Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak in ChinaДокумент10 страницMental Health Problems and Correlates Among 746 217 College Students During The Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak in ChinaReyes Ivan García CuevasОценок пока нет

- Mental Health Burden For The Public Affected by The COVID 19 Outbreak in China Who Will Be The High Risk GroupДокумент13 страницMental Health Burden For The Public Affected by The COVID 19 Outbreak in China Who Will Be The High Risk GroupMaria Guadalupe DiazОценок пока нет

- Advpub JE20200148Документ9 страницAdvpub JE20200148STIKes Santa Elisabeth MedanОценок пока нет

- Ahmed Et Al 2020 Epidemic of COVID-19Документ7 страницAhmed Et Al 2020 Epidemic of COVID-19Lauro Miranda DemenechОценок пока нет

- Brain, Behavior, and ImmunityДокумент9 страницBrain, Behavior, and ImmunityIndah NurlathifahОценок пока нет

- Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms Among People Under Quarantine 1 During The COVID-19 Epidemic in China: A Cross-Sectional StudyДокумент30 страницDepressive and Anxiety Symptoms Among People Under Quarantine 1 During The COVID-19 Epidemic in China: A Cross-Sectional StudyHaziq QureshiОценок пока нет

- Impact of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Mental Health and Quality of Life Among Local Residents in Liaoning Province, China: A Cross-Sectional StudyДокумент12 страницImpact of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Mental Health and Quality of Life Among Local Residents in Liaoning Province, China: A Cross-Sectional StudyieykatalibОценок пока нет

- Study Ref 1Документ32 страницыStudy Ref 1Trixia AlmendralОценок пока нет

- COVID-19 Infodemic and Indonesian Emotional and Mental Health StateДокумент7 страницCOVID-19 Infodemic and Indonesian Emotional and Mental Health StateIJPHSОценок пока нет

- Ijerph 17 03165 v2Документ14 страницIjerph 17 03165 v2أحمد خيرالدين عليОценок пока нет

- Aphw 12 1019Документ20 страницAphw 12 1019Dini Pratiwi NasruddinОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Social Support On Mental Health in Chinese Adolescents During The Outbreak of COVID-19Документ5 страницThe Effect of Social Support On Mental Health in Chinese Adolescents During The Outbreak of COVID-19Nurul HayatiОценок пока нет

- Neill2021 Article MediaConsumptionAndMentalHealtДокумент9 страницNeill2021 Article MediaConsumptionAndMentalHealtKhadijaОценок пока нет

- COVID-19 Stress and Mental Health of Students in Locked-Down CollegesДокумент12 страницCOVID-19 Stress and Mental Health of Students in Locked-Down CollegesManoj MaggotОценок пока нет

- Social Network Analysis of COVID-19 Sentiments: Application of Artificial IntelligenceДокумент13 страницSocial Network Analysis of COVID-19 Sentiments: Application of Artificial Intelligenceapi-294607099Оценок пока нет

- Knowledge Attitudes and Mental Health of University 2020 Children and YoutДокумент4 страницыKnowledge Attitudes and Mental Health of University 2020 Children and YoutlucianoОценок пока нет

- Sun Et Al., 2021Документ14 страницSun Et Al., 2021Edgardo ToroОценок пока нет

- COVID-19 Infection Outbreak Increases Anxiety Level of General Public in ChinaДокумент7 страницCOVID-19 Infection Outbreak Increases Anxiety Level of General Public in ChinaDostin JasserОценок пока нет

- 2020 - Dong - Early Release - Public Mental Health Crisis During COVID-19 Pandemic, China - Volume 26, Number 7-JuДокумент4 страницы2020 - Dong - Early Release - Public Mental Health Crisis During COVID-19 Pandemic, China - Volume 26, Number 7-Juleafar78Оценок пока нет

- A. Bendau Et Al. 2021 Associations Between COVID 19 Related Media Consumption and Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression and COVID 19 Related Fear in The General Population in GermanyДокумент9 страницA. Bendau Et Al. 2021 Associations Between COVID 19 Related Media Consumption and Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression and COVID 19 Related Fear in The General Population in GermanyRafiqua Sifat JahanОценок пока нет

- Experiences, Impacts and Mental Health Functioning During A COVID-19 Outbreak and Lockdown Data From A Diverse New York City Sample of College StudentsДокумент17 страницExperiences, Impacts and Mental Health Functioning During A COVID-19 Outbreak and Lockdown Data From A Diverse New York City Sample of College StudentsAdrian LopezОценок пока нет

- Ijerph 18 09880 v2Документ19 страницIjerph 18 09880 v2Anne Caitlene PamintuanОценок пока нет

- Psychiatry Research: A B A BДокумент6 страницPsychiatry Research: A B A BMaria Paola ValladaresОценок пока нет

- Fpsyg 12 755347Документ11 страницFpsyg 12 755347thinh_41Оценок пока нет

- Acute Mental Health Responses During The Covid-19 Pandemic in AustraliaДокумент22 страницыAcute Mental Health Responses During The Covid-19 Pandemic in AustraliaIzen Rizki SilviaОценок пока нет

- PDFДокумент10 страницPDFluis renzoОценок пока нет

- COVID-19 and Mental Health A Study of Its Impact oДокумент8 страницCOVID-19 and Mental Health A Study of Its Impact oTinОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S0165178120306077 MainextДокумент8 страниц1 s2.0 S0165178120306077 MainextMaria DrinaОценок пока нет

- The Sampling Method Using The Snowball Technique Was Used To Invite Research SubjectsДокумент18 страницThe Sampling Method Using The Snowball Technique Was Used To Invite Research SubjectsSinta Dewi PapОценок пока нет

- The Impact of COVID-19 On Mental Health The Role oДокумент15 страницThe Impact of COVID-19 On Mental Health The Role oDaniel EidОценок пока нет

- Effect of Lockdown During COVID 19 An inДокумент7 страницEffect of Lockdown During COVID 19 An inMuhammad bilalОценок пока нет

- Covid Health in India ReportДокумент9 страницCovid Health in India ReportRobert PillaiОценок пока нет

- Hassan AbdullahДокумент11 страницHassan AbdullahHassan AbdalfttahОценок пока нет

- Covid 19Документ7 страницCovid 19Saurav KumarОценок пока нет

- Correspondence: Mental Health Services For Older Adults in China During The COVID-19 OutbreakДокумент1 страницаCorrespondence: Mental Health Services For Older Adults in China During The COVID-19 OutbreakArgonne Robert AblanqueОценок пока нет

- Journal of Affective DisordersДокумент8 страницJournal of Affective DisordersArgonne Robert AblanqueОценок пока нет

- Research Methods ProjectДокумент19 страницResearch Methods ProjectMona HamedОценок пока нет

- Coping Style, Social Support and Psychological Distress in The General Chinese Population in The Early Stages of The COVID-19 EpidemicДокумент11 страницCoping Style, Social Support and Psychological Distress in The General Chinese Population in The Early Stages of The COVID-19 EpidemicLau DíazОценок пока нет

- Association Between Knowledge and Depression at Rising Time of COVID-19 in BangladeshДокумент7 страницAssociation Between Knowledge and Depression at Rising Time of COVID-19 in BangladeshIJPHSОценок пока нет

- Lai 2020 Mental Health Impacts of The CovidДокумент13 страницLai 2020 Mental Health Impacts of The CovidManoj MaggotОценок пока нет

- COVID-19-related Stigma and Its' in Uencing Factors: A Rapid Nationwide Study in ChinaДокумент23 страницыCOVID-19-related Stigma and Its' in Uencing Factors: A Rapid Nationwide Study in ChinaAzzalfaAftaniОценок пока нет

- A Cross-Sectional Study of Psychological Status in Different Epidemic Areas in China After The COVID-19 OutbreakДокумент8 страницA Cross-Sectional Study of Psychological Status in Different Epidemic Areas in China After The COVID-19 OutbreakAnjali PandeyОценок пока нет

- Psychological Impact of COVID-19 On University Students at Karachi PakistanДокумент14 страницPsychological Impact of COVID-19 On University Students at Karachi PakistanMuhammad RahiesОценок пока нет

- Coronatracker: World-Wide Covid-19 Outbreak Data Analysis and PredictionДокумент32 страницыCoronatracker: World-Wide Covid-19 Outbreak Data Analysis and PredictionNishant UdavantОценок пока нет

- How Compulsive WeChat Use & Information Overload Affect Social Media FatigueДокумент11 страницHow Compulsive WeChat Use & Information Overload Affect Social Media FatigueMariam AlraeesiОценок пока нет

- 2020-Improving Mental Health PRI 41385-113065-2-PBДокумент8 страниц2020-Improving Mental Health PRI 41385-113065-2-PBTria WidyastutiОценок пока нет

- The Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019: a psychological perspectiveОт EverandThe Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019: a psychological perspectiveОценок пока нет

- From Crisis to Catastrophe: Care, COVID, and Pathways to ChangeОт EverandFrom Crisis to Catastrophe: Care, COVID, and Pathways to ChangeОценок пока нет

- Role of Federal Planning Authority in TH PDFДокумент16 страницRole of Federal Planning Authority in TH PDFieykatalibОценок пока нет

- Empowerment in Action Case Studies of Local Authority Community DevelopmentДокумент36 страницEmpowerment in Action Case Studies of Local Authority Community DevelopmentieykatalibОценок пока нет

- Impact of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Mental Health and Quality of Life Among Local Residents in Liaoning Province, China: A Cross-Sectional StudyДокумент12 страницImpact of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Mental Health and Quality of Life Among Local Residents in Liaoning Province, China: A Cross-Sectional StudyieykatalibОценок пока нет

- Form 7D (Section 124A) - Application For Variation of Conditions, Restrictions and Categories in Respect of Proposed Sub-Divisional Portions of LandДокумент2 страницыForm 7D (Section 124A) - Application For Variation of Conditions, Restrictions and Categories in Respect of Proposed Sub-Divisional Portions of LandieykatalibОценок пока нет

- Wylde Feasibility PDFДокумент70 страницWylde Feasibility PDFieykatalibОценок пока нет

- 4-Adat Land PDFДокумент17 страниц4-Adat Land PDFieykatalibОценок пока нет

- Sydney Opera HouseДокумент4 страницыSydney Opera HouseieykatalibОценок пока нет

- Elizabeth FallsДокумент30 страницElizabeth FallsieykatalibОценок пока нет

- Benefits of Sneakers - Fashion EyeДокумент2 страницыBenefits of Sneakers - Fashion EyeieykatalibОценок пока нет

- Narmatha Priya NДокумент34 страницыNarmatha Priya NLiyaskar LiyaskarОценок пока нет

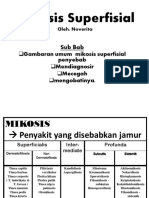

- Mikosis SuperfisialДокумент46 страницMikosis SuperfisialAdipuraAtmadjaEgokОценок пока нет

- Pain - FДокумент22 страницыPain - FmadvincyОценок пока нет

- Caitlyn Fink Research EssayДокумент12 страницCaitlyn Fink Research Essayapi-609502041Оценок пока нет

- Clarize Avedano-BEED-1A-GMRCДокумент7 страницClarize Avedano-BEED-1A-GMRCpatrick batallaОценок пока нет

- 0610 s14 QP 13Документ16 страниц0610 s14 QP 13hosni_syr50% (2)

- Sensory Evaluation of Bitter Gourd Momordica Charantia DoughnutДокумент66 страницSensory Evaluation of Bitter Gourd Momordica Charantia DoughnutMary Angelie BaguinОценок пока нет

- Study On The Evaluation of Oral Rehabilitation Using Dental Implant by Qantifying Osteoprotegerin and InterleukinДокумент7 страницStudy On The Evaluation of Oral Rehabilitation Using Dental Implant by Qantifying Osteoprotegerin and InterleukinNordsci ConferenceОценок пока нет

- Mixed Exercises 27Документ13 страницMixed Exercises 27Trần LộcОценок пока нет

- Nakamura IIДокумент10 страницNakamura IIMairaMaraviChavezОценок пока нет

- National Nutrition Surveys in Asian CountriesДокумент11 страницNational Nutrition Surveys in Asian CountriesValentino Krismonico100% (1)

- BLS 1Документ1 страницаBLS 1Moxie MacadoОценок пока нет

- 2020-Infodemiological Study On COVID-19 Epidemic and COVID-19 InfodemicДокумент10 страниц2020-Infodemiological Study On COVID-19 Epidemic and COVID-19 Infodemicvivitri.dewiОценок пока нет

- Novi Dwi Amelia Putri 17018143 Analytical Exposition The Importance of ExerciseДокумент3 страницыNovi Dwi Amelia Putri 17018143 Analytical Exposition The Importance of ExerciseRezki HermansyahОценок пока нет

- Yakult Profile PDFДокумент30 страницYakult Profile PDFBodhiОценок пока нет

- Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity: David M. Dickerson, MD and Jeffrey L. Apfelbaum, MDДокумент9 страницLocal Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity: David M. Dickerson, MD and Jeffrey L. Apfelbaum, MDManish VijayОценок пока нет

- HTTPS:WWW Ncbi NLM Nih gov:pmc:articles:PMC9867007:pdf:viruses-15-00225Документ17 страницHTTPS:WWW Ncbi NLM Nih gov:pmc:articles:PMC9867007:pdf:viruses-15-00225Don SarОценок пока нет

- A Study of Prevalence of Insomnia Among University Tunku Abdul Rahman Students PDFДокумент76 страницA Study of Prevalence of Insomnia Among University Tunku Abdul Rahman Students PDFMaria Gracia FellytaОценок пока нет

- Vitamin C 250 MG TabletДокумент5 страницVitamin C 250 MG TabletdidarОценок пока нет

- Garcia - Assignment1 - Ipe 402aДокумент2 страницыGarcia - Assignment1 - Ipe 402aAron GarciaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 4: Modifiable Risk Factors of Lifestyle DiseasesДокумент64 страницыChapter 4: Modifiable Risk Factors of Lifestyle DiseasesJemah AnnОценок пока нет

- Tribal Health: Dr. Minitta Regy Post Graduate Student Dept. of Community Medicine, ST John's Medical College BangaloreДокумент23 страницыTribal Health: Dr. Minitta Regy Post Graduate Student Dept. of Community Medicine, ST John's Medical College BangaloreMini RegyОценок пока нет

- ELC550 ANS KEY - 22january2019-VettedДокумент3 страницыELC550 ANS KEY - 22january2019-VettedCtОценок пока нет

- Hemostasis Specimen Collection and HandlingДокумент5 страницHemostasis Specimen Collection and HandlingDENILLE AIRA NOGOYОценок пока нет

- SARS-CoV-2 Brain Change StudyДокумент32 страницыSARS-CoV-2 Brain Change StudyNational Content DeskОценок пока нет