Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Short Term Implications For The Oil Market - Schroders

Загружено:

smaliasОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Short Term Implications For The Oil Market - Schroders

Загружено:

smaliasАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Marketing material for professional investors or advisors only

IMO 2020 – Short-term

implications for the oil market

Felix Odey and Mark Lacey, Schroders

Commodities team

August 2018

For Financial Intermediary, Institutional and Consultant use only.

Not for redistribution under any circumstances.

Executive summary

The IMO 2020 regulation mandate ships to emit less sulphur dioxide by only using fuel oil with less than 0.5% sulphur content (vs 3.5%

currently).

This regulation has been postponed for a number of years, but 2020 is now a set date for the regulation implementation. The main

uncertainty is around the level of compliance from shippers.

Adaptation of ships (scrubbers or LNG propulsion) is unlikely to make up more than 30% of substitution away from high sulphur fuel oil.

Even with conservative assumptions there will still be wide-reaching impacts on distillate/kerosene refining margins. Shippers will be most

impacted but so will those reliant on distillate products (diesel, kerosene, heavy and light gas oil).

The crude market is likely to see demand tailwinds from HSFO used in power generation, with medium weight low sulphur crudes as the

clear winners and sour or super light crudes potentially losing out from the new regulation.

Regionally, crude from North/West Africa, Brazil and parts of the North Sea are best suited to producing IMO 2020 compliant fuel oil, and

will consequently go to premium vs sour crudes.

Most global production growth is coming from Russia, Middle East OPEC or North America. By and large, the type of crude from these

regions is generally not low sulphur (<0.5%).

Globally, refiners have been slow to change and are taking a "wait and see" attitude. Some refiners have already invested and are

complex enough to produce the cleaner product slate.

Combined with high utilisation rates and light crude loading vs historical levels, distillate markets could tighten considerably post 2020.

Additional capital expenditure will be required to increase desulphurisation/cracking capacity.

In the long run the market wide crude differentials will soften, and distillate margins will normalise, but this could be longer than

expected and have dramatic impacts for energy markets and industrial activity in the meantime.

Background

What is IMO 2020?

The International Maritime Organisation (a branch of the UN) has stated that as of the 1 January all ships must reduce their sulphur emissions

from 3.5% thresholds to 0.5%. The regulation has already been passed and any attempt to change the regulation would potentially take

another 22 months (i.e. the regulation will go through on the stated date). The aim of this regulation is to reduce the emission of sulphur

dioxide (which results in acid rain and environmental damage).

To give a sense of how pressing this is, on an annual basis, one large container ship emits more sulphur dioxide than 50 million

diesel cars over a year (there are over 65,000 ships in operation globally).

What is the impact on maritime consumption and fuel substitution?

The bunker fuel market currently accounts for around 5.5 million barrels per day (mb/day) of global consumption, with 4mb/day accounted

for by ferries, cruise/container ships, LNG/LPG, dry bulk transport and oil tankers; amounting to around 70k ships.

These ships consume over 50% of the total global fuel oil demand. Fuel oil is a long hydrocarbon fraction obtained during petroleum

distillation, and has traditionally been the bottom of the barrel, high sulphur by-product formed along with gasoline and distillate (diesel) by

refiners.

IMO 2020 will mean ships can no longer simply burn untreated high sulphur fuel oil (HSFO). This leaves three options available to shippers:

i. Install scrubbers (exhaust gas cleaner systems that extract the sulphur as the HSFO is burned).

ii. Switch fuel intake to low sulphur fuel oil (which is equivalent to distillate).

iii. Switch to liquid natural gas (LNG) propulsion systems.

Despite being well flagged, the shippers have been relatively slow moving in adapting for three main reasons. The first is because the

industry has been in a structural downturn, and consequently capital has been constrained. The second is that players are dis-incentivised to

be early movers on installing scrubbers or converting to LNG, given the capital expenditure requirement and uncertainty around enforcement

of the regulation. Thirdly the state of the HSFO and LNG markets over the next two years is an additional uncertainty, both in terms of

availability at ports and price. Ultimately, shippers do not want to limit their trade routes and port refilling options and will therefore act as

late as possible.

The IMO has until recently been ambiguous around enforcement of the 2020 legislation and this has contributed to the slow progress of

shippers. However, they have now made it clear that ships will be regularly checked going in and out of ports and ships not installed with

scrubbers will not be allowed to carry HSFO, to stop fuel switching out at sea.

Given that scrubbers take 6-9 months to install, coupled with the limited number of ports capable of installing them, there is likely to be long

instillation lead times even if shippers start to demand them now. From an industry supply perspective, the best possible outcome is around

1200 are installed before the 2020 deadline (out of the +60,000 needed at this point in time).

Put simply, this implies that the most likely outcome of the implementation of IMO 2020 is a significant increase in demand for low sulphur

distillates and a surplus of high sulphur fuel oil.

IMO 2020 – Short-term implications for the oil market 2

To illustrate this increase in demand in simple terms the basic assumptions/numbers are highlighted below:

We conservatively assume the low end of current global bunker fuel usage (HSFO) of around 5.0mb/day (the current estimated range is

5.0-6.0mb/day).

We optimistically expect that 0.5mb/day of HSFO will be substituted through conversion to LNG propulsion.

We optimistically expect that 0.5mb/day of the existing HSFO demand will remain as some ships will install scrubbers to reduce emissions.

We also conservatively expect that 1.5mb/day of HSFO demand continues, due to less disciplined operators not complying with the new

regulation (through bribes or fuel switching out to sea).

Nevertheless, this still leaves the need for refiners to supply an additional 2.5mb/day of increased LSFO/middle distillate demand from

shippers in 2020.

The base global demand for distillate is around 30mb/day, therefore a 2.5mb/day increase in demand from IMO in 2020 amounts to around

an 8% increase in demand over a short period of time.

A bit more detail around the HSFO substitution assumptions

Liquefied natural gas conversion

Our 0.5mb/day of HSFO fuel switching could prove too optimistic. In the first few years post the 2020 implementation, we do not forecast a

significant amount of LNG switching (10%) because of the limits on the number of ports fitted with LNG refuelling (there are 800 marine

bunkers vs only 55 LNG ports).

However, LNG conversion/adoption is more bullish longer-term given: improving port availability, (the 25 biggest ports globally will have LNG

refuelling by 2021), and separate IMO regulation targeting a 50% carbon dioxide emission reduction by 2050 (vs 2008 levels). LNG could

consequently be an area of increased substitution, but this is more likely to play out on a 5-20 year horizon.

Scrubber instillation

If shippers order a scrubber now the current lead time (waiting period plus instillation) is around 6-9 months. Installation is quite quick (2-4

months, requiring incremental investment of about $3-5m). However, instillation requires a dry dock and a limited number are suitable or

available (around 428 of varying sizes)¹. Currently around 500 ships are fitted with bulk carriers and tankers accounting for over 50% of

scrubbers installed or on order. Our base case assumes 3000 ships are fitted by 2020, which implies a 0.5mb/day will continue to use HSFO in

compliance with IMO.

Non-compliance to IMO 2020 Figure 1: Percent of global bunker supply concentration

We measure compliance as a percentage of bunker fuel consumption

globally (rather than percentage of compliant ships). This is an Panama

important distinction given 25% of the total ship fleet consumes 85% 3% US

of marine fuel. We have assumed 30% non-compliance of IMO 2020. 7%

This may prove to be on the high side given: Japan/South

The high concentration of bunker fuel demand from a small Korea Singapore

7% 28%

number of ships. Russia

5%

The high concentration of bunker fuel supply from a small

number of countries. Hong Kong

5%

Country support for the regulation: North American, Eurozone

Gibralter

and China as end markets account for around 90% (by tonnage)

7%

of the world sea borne trade. None of these are likely to oppose China

the IMO 2020 regulation. Likewise there is backing from almost Rotterdam 14%

all the countries supplying bunker fuel (shown in chart I) with 10%

UAE as the only major supplier that is not a signatory of the UAE

environmental air pollution convention (MARPOL). 14%

Support from large public companies, both ship insurers and

shipping companies (Maersk, Hapag-Lloyd, J Laritzen and others

have formed the “Trident Alliance” with the aim of aiding

Source: IEA, Schroders.

enforcement of the IMO 2020 regulation).

However, it should be noted that opinions on compliance varies

considerably e.g. Bob Dudley (CEO of BP) believes compliance will be

below 50% given the difficulty of enforcing the regulation globally.

¹https://www.trusteddocks.com/catalog/region/western-europe

IMO 2020 – Short-term implications for the oil market 3

How does this impact crude oil demand and product demand?

When assessing the supply and demand dynamics of the global oil market, the implicit assumption usually made is that each barrel of crude

can be used at a 1:1 ratio to create the various oil based products demanded. However, in a period where distillate demand grows

disproportionally faster than both gasoline and fuel oil demand, this assumption is called into question.

Typically the maximum distillate cut for each barrel of medium API crude is approximately 50%. This means around two barrels of crude is

required to produce one barrel of distillate. Therefore our forecast of 8% growth in distillate demand over the next 18 months could result in

higher crude oil demand of around 5.0mb/day (i.e. 2.5Mb/day x 2 = 5.0Mb/day), and surplus fuel oil production as an inevitable by-product,

which can be used for power generation.

It is worth noting that distillate inventories are already well below the five year average levels and given current refining set up it is hard to

see how inventories do not draw further as we approach 2020.

Putting this distillate demand lift in context of the global crude demand balances, it is very clear to us that 2020 will prove to be an unusual

and potentially very strong demand year.

Below is a summary of the oil market balances for both 2019 and 2020. It is important to note that many sell side IMO research reports

estimate that oil demand could be lifted by as much as 1.8mb/day over and above normal growth rates of 1.2-1.6mb/day every year.

As noted before in the report, we have taken a more conservative approach with regard to demand, as we do not expect the shipping

industry to be 100% compliant and more importantly we expect any spike in distillate prices will slow the conversion rate (i.e. the demand lift

will be spread over a longer period).

Our underlying assumptions are simple:

2020 – Non IMO related demand growth is just 1.0mb/day – strong USD and higher oil prices having a direct impact.

2020 – IMO related (additional distillate demand) is 1.0mb/day. A relatively conservative assumption.

2020 – Non OPEC ex-NA supply grows by 0.3mb/day (which equates to 1.8mb/day of new project supply due to a 4% base decline rate).

2020 – Non OPEC North American supply grows by 1.2mb/day. This assumes no pipeline constraints (which will be a limiting growth factor

in 2019).

2020 – Call on OPEC production will be 33.0mb/day. This compares to their current production rate of 31.8mb/day and assumes that

effective spare capacity is below 1.0mb/day. This assumes no decreases in Iranian, Venezuelan, Libya or Angolan production.

A summary of the oil market balances for 2019 and 2020 estimates (mb/day)

2019 2020

Schroders IM y-o-y Δ Schroders IM y-o-y Δ

mnbd mnbd

Global demand 100.4 1.1 Global demand 102.4 2.0

OECD demand 47.4 0.0 OECD demand 48.4 1.0

Non-OECD demand 53.0 1.1 Non-OECD demand 54.0 1.0

Non-OPEC supply 60.9 0.7 Non-OPEC supply 62.3 1.5

Non-OPEC ex-NA 36.7 -0.5 Non-OPEC ex-NA 37.0 0.3

North America 24.1 1.2 North America 25.3 1.2

OPEC NGL 7.1 0.0 OPEC NGL 7.1 0.0

Non-OPEC + NGL 68.0 0.7 Non-OPEC + NGL 69.4 1.5

Est. 2019 OPEC production 32.5 0.4 Est. 2019 OPEC production 33.0 0.5

Market balance 0.0 Market balance 0.0

Source: Schroders.

Going forward we expect the excess HSFO to be an unwanted by-product, and price to weaken substantially. However, this does not mean it

will become a wasted product, as refiners have already confirmed that it will likely incentivise HSFO being used as a fuel for power generation,

competing with coal in emerging markets (HSFO emits less CO2 than coal).

It is important to highlight that HSFO contains around 50% more energy per unit than coal. With current coal prices of $50/tonne, this implies

that HSFO prices would need to decline to around $100/tonne to be competitive with coal fired power stations; this requires a significant fall

from spot and two year forward prices ($400/tonne and $250/tonne respectively).

“HSFO surplus will be taken on by either refineries capable of cracking it, or emerging market economies to burn for power generation as an

alternative to coal, the Saudis are already approaching European refiners to discuss exchanging their crude with HSFO by-products” - Greg

Garland (CEO Phillips 66)

IMO 2020 – Short-term implications for the oil market 4

How does this change the refining environment?

The impacts and market adjustments that will be required to adapt to a post IMO regulation world are threefold:

i. Divergent pricing of crudes based on their sulphur content.

ii. Divergent pricing of crudes based on distillate cut available (a function of API).

iii. Increased investment by refiners to allow more desulphurisation.

Background and definitions of oil grades:

Sulphur content

Crude type Weight (API) Crude type Weight (API)

(% wt)

Light >31.0

WTI 39.6 0.24

Medium 22.3-31.1

Heavy <22.3 Brent 38.3 0.4

Extra heavy <10

1.77 (wide variety

OPEC basket 32.7

Sour crude has sulphur content greater than 0.5%. within average)

Source: Schroders.

Crude sulphur content:

It is believed that less than 20% of crude volumes globally can, without blending, be used to create IMO compliant fuel oil (LSFO), although

Galp’s head of downstream thought this figure could be as low as 5%! Well suited areas include Brazil pre-salt, North Sea, West African crudes,

and many areas of US onshore shale (more detail is given in upstream section). This means that each refiner will need to develop a blend that

can economically produce LSFO (with resilience to widening of sweet/sour price differentials). However, most refiners will still have to produce

HSFO as a bottom of the barrel by-product. One issue is that different impurities (asphaltenes) in crudes can interact and precipitate, resulting

in sludge formation down the line, which can clog ship engines.

Another issue is that refiners are not comparing notes on blending; this means post IMO 2020 there may be increased reliance on a few hubs

(causing the price to rise beyond where it is economic). Another implication is that two compliant LSFOs from different refiners may become

uncompliant when mixed in marine bunkers. This will require fuel segregation (expensive in terms of infrastructure), or cross-compatibility

testing (takes time and money and could cause tanker delays).

Heaviness of crude and distillate yield:

There is a large disparity in what refiners are built to take in terms of American Petroleum Index (API), and what distillate/product yield can be

achieved from the same refiner slate.

Figure 2 below shows the API vs product yield relationship. Detail on this relationship is given in the next section, but what is clear is that light

gas oil (LGO), heavy gas oil (HGO) and resid yield declines rapidly from light crudes with API >40, LGO and cracked HGO or resid is required for

diesel and LSFO production.

Figure 2: Refining yield vs API relationship between crude hubs

Yields (% of vol)

100% 80

Atmospheric Resid 375+

90%

70

Heavy Gas Oil 320-375

80%

60 Light Gas Oil 240-320

70%

Kerosene 180-240

50

60%

Heavy Naptha 90-180

50% 40 Light Naptha 5-90

40% C4s

30

30% C3-

20

20% API

10

10%

0% 0

Azeri BTC

Peregrino

Alba

Norne Blend

Grane Blend

CLOV

Njord

Saxi Batuque Blend

Alvheim blend

Skarv

Åsgard Blend

Hibernia Blend

Troll Blend

Jotun

Eagle Ford Chem Grade

Algerian Cond.

Pazflor

Saturno

Terra Nova

Gullfaks

Oseberg Blend

Dalia

Mondo

Girassol

Azeri Light

Draugen

Bakken

Agbami

Eagle Ford Gen Grade

Gudrun Blend

Hungo Blend

Kissanje Blend

Goliat

Forties Blend

Ekofisk blend

Ormen Lange Cond.

Snøhvit Cond.

Heidrun

Statfjord

Source: Equinor Company Data; Schroders.

IMO 2020 – Short-term implications for the oil market 5

Regional refining

United States

Ironically the US refineries have been upgraded in the last 15 years to take heavier crude. When they made the investment decision, their

domestic light production was declining and they thought they would need a higher import requirement of medium and heavy grades. This

has changed with the US shale boom but US refiners still need to import Canadian heavy, Mayan or Venezuelan crude to blend with lighter

shale grades. These imported crudes are mainly high sulphur (sour). This will mean the distillate produced using them will not be IMO

compliant without additional desulphurisation capacity.

“We are already fairly maxed out in the amount of light crude we are taking into our refineries, we could flex it a few percent maximum. We

have secured imports from Canada as a source of heavy crude to replace Venezuelan sources; we have not received a shipment from PDVSA

since October 2017” - Greg Garland (CEO Phillips 66)

The theoretical options available to US refiners are simple: to invest in desulphurisation equipment, adapt refineries to take lighter crudes, or

increase utilisation further to boost overall distillate (and other product) output.

In reality utilisation rates in the US area already at around 95%; which is the maximum a refinery can practically operate at to account for

maintenance periods and outages. In addition, US refiners are maxed out on US onshore light crude. Any increase in throughput would also

likely erode gasoline margins as the market becomes oversupplied.

Europe

The European refiners are in a slightly better position than their American peers. Due to consumer trends in diesel demand, which were well

defined until 2015, refineries are already more geared towards producing distillate. However, this distillate output has high sulphur content,

and is not suitable for IMO 2020 regulations. This is because a large portion of the heavy crude slate comes from Russia (Urals). Coastal

refiners are advantaged because they can source more of their crude from North/West Africa, which tends to be less sour. Alternatively, they

can take US light and sweet crude to blend with the heavier sour crudes from Russia. Galp, Repsol and Saras all have European refineries that

are well placed and set to benefit from IMO 2020.

European refiners also have more scope to increase utilisation, because current utilisation rates are lower at around 83%.

However, storage and transportation constraints could limit utilisation rates in Europe. The refining process inherently produces HSFO, and

ships currently account for over 50% of HSFO use. With IMO 2020 resulting in ships switching to low sulphur distillate, demand could fall

sharply resulting in rapid builds in inventories. This could quickly fill the storage available.

“We have invested in our refineries, but many European refiners will not have sufficient desulphurisation or cracking capacity, and are

dependent on sour crudes from Russia and the Middle East. We expect our refining margin to improve as a result of IMO 2020, given our

expectation of sour crude discounts.” – Dario Scaffardi (CEO Saras)

Coal/petcoke prices should act as a price floor for fuel oil prices, as HSFO can be burnt for power generation, and this will likely be taken up by

emerging markets in need of cheap energy. HSFO also emits less CO2 than coal and the sulphur can be captured by scrubbers installed at the

power plant level. This is economically more efficient than fitting individual ships with scrubbers.

However, considering tanker ships without scrubbers will not be allowed to transport HSFO there could be transportation bottlenecks and it is

conceivable that the glut of HSFO from European refiners could end up limiting output if it cannot be removed and transport costs become

very high (offsetting benefit from distillate margins). Avoiding this scenario will require refiner adaptation to break down the HSFO into lighter

products.

Asia/Middle East

Refining utilisation rates in Asia are similar to those in Europe. However, the majority are located in the Middle East, where significant new

desulphurisation capacity is required to be IMO compliant post 2020. Likewise, Chinese tea-pot refineries do not have the complexity to

increase production of IMO compliant distillate.

Refinery adaptation/investment

There are four main types of technology that can be used to try to supply the market in a post IMO 2020 world, and stop hub differentials

from blowing out, or diesel prices rising too aggressively. These are bottom of the barrel conversion, adaptation to lighter crudes,

desulphurisation and resid hydrocrackers (which allow more distillate cut by adding heavier elements).

Broadly speaking these either involve altering the API crude slate refiners are capable of taking, therefore allowing a higher middle distillate

yield from light (e.g. shale) crudes, or alternatively processing crudes to remove the sulphur.

Refiners with desulphurisation capacity will use the best yielding (middle/heavy weight) and cheapest crudes, regardless of sulphur content.

Consequently we expect differential between sweet and sour hubs to go to a significant discount, but think it is unlikely to go beyond an $8

differential, because medium/heavy grades will be demanded for its high product yield by refiners able to remove the sulphur.

Only a small percentage of the global refining complex has desulphurisation equipment installed, and to do so is expensive. For an average

refiner (of around 0.2 Mb/day capacity) instillation of desulphurisation equipment (resid hydrocracker) would cost around $1bn. Investing in

additional cracking units (to allow a greater distillate yield, is also fairly expensive, a Coker costs $600-$800m.

IMO 2020 – Short-term implications for the oil market 6

The refining process and potential areas of adaptation:

Figure 3: Simplified refining process diagram

Hydrocracking / Diesel, Kerosene and

treating Gasoline

Atmospheric

Crude

crude

De-salter

fractionator

Vacuum Coker Asphalt

Source: Schroders.

Figure 4: Detailed refining process diagram

Source: Google image.

Methods of refining adaptation Fractions and associated temperatures

Breaking down longer hydrocarbons to boost diesel output:

Light straight-run (LSR) naphtha 90-190°F

Hydrocracking: this reformulates heavier ends of barrel into shorter Heavy straight run (HSR) naphtha 190-330°F

chain products (mainly kerosene (jet fuel) and diesel). Kerosene i.e. jet fuel 330-480°F

Older hydrocracking units in the US were designed to favour Light atmospheric gas oil (LAGO) 480-610°F

gasoline and jet fuel production. Heavy atmospheric gas oil (HAGO) 610-800°F

Vacuum gas oil (VGO) 800-1,050°F

Newer units are focused on low sulphur diesel and jet fuel.

Vacuum reduced crude (VRC) above 1,050°F

Fluidised catalytic cracker: breaks down longer hydrocarbon chains using a

Fluidised catalyst. 5% of catalyst turns into coke, requires regeneration with addition of air.

Resid hydrocracker: this takes the vacuum resid (e.g. HSFO) and cracks it into shorter chain products (e.g. coker distillate), producing pet

coke as a by-product (this can be sold to power/cement plants).

The coker distillate then undergoes hydro treating to remove sulphur.

Desulphurisation:

Hydro treating: this process reduces sulphur, nitrogen and aromatics and enhances density and smoke point of products.

Hydrodesulphurisation: sulphur is removed from diesel by reacting it with hydrogen with catalysts, temperature and pressure.²

How well adapted or adaptable are refiners for this shift in consumption, and who is set to benefit from it?

Lack of refiner investment:

Unlike previous investment cycles, the prospect of growing electric vehicle demand reducing future gasoline and diesel demand, coupled with

shareholder demands for return of capital, has prompted greater capital discipline amongst refiners. Consequently fewer large new refineries

(designed to take more light crude) have been sanctioned over the last three years (apart from the Middle East). Instead a greater amount of

capital is being returned to shareholders by refiners (for example 60% of FCF generated by Phillips 66 and Marathon this year will be returned

through buybacks or dividends). Likewise, the downstream segment has been a significant FCF generator for integrated energy companies,

and is subject to the same capital discipline applied to the upstream business.

IMO 2020 – Short-term implications for the oil market 7

Global crude slate:

Venezuelan production (previously a source of heavier crude) has fallen around 0.8mb/day since 2016 and US onshore light shale crude has

increased its share of the global market. PDVSA’s cash flow issues has resulted in many US refiners being unwilling to transact with them.

This means that there will be less heavy and medium grade crude, just when more is required. Most refiners are already taking the maximum

light crude they can whilst maintaining their product split. Refiners in the US are now focused on increasing their imported volumes of heavy

crude from Canada and Maya (Mexico).

Discussions with refining managers suggest that at current utilisation rates European refiners are maxed out in terms of distillate production.

They therefore cannot bring much production online in reaction to any change in demand and price, without changing their crude slate or

upgrading their facilities.

The first thing refiners will do in reaction to higher distillate demand is increase utilisation in Asia and Europe (where there is spare capacity).

However, incremental distillate production beyond that will require investment in refineries to increase cracking capacity, or greater

desulphurisation capacity. The more complex refiners with more hydrotreating/coker/hydrocracking capacity are in a better position for a

post IMO 2020 market, because they have flexibility on what crudes they take, and can even take in HSFO and crack this into distillate

(through cokers) and hydrotreat to remove sulphur (below the 0.5% threshold).

How does this impact upstream energy markets?

There is mixed opinion on whether IMO 2020 implications will be greater for crude producers or refiners in the global oil markets.

Because most refiners do not have the right refining infrastructure to produce more LSFO/distillate; many will need to change what goes into

the refineries. This will create more demand for low sulphur (sweet) middle weight crudes, and proportionally less demand for high sulphur

(sour) crudes.

With regards to producers, management we have spoken with think pricing differentials between sweet and sour, all other things being

equal, could be between $2-8/bl after IMO implementation, but in reality it is impossible to accurately predict, as $25 differentials are not

heard of in the short term (1-2 years). The table below highlights some of the best placed crudes globally, and the upstream companies

associated.

“IMO 2020 will be more of an upstream story, given the mixed impact it will have on different product margins. We are well placed as our

refineries are already capable of producing 0% HSFO, and our crude production is medium API and sweet, and should therefore trade at a

premium to sour grades. I think that premium could reach $8-10 in some cases.” – Head of Downstream Galp.

Global crude hubs positively exposed to IMO 2020

Country/Basin API Sulphur content Companies associated Potential impact on

(average) prem. to Brent

UK North Sea 19-37 0.5% PMO, ENQ, STL

Norway (ex. Condensate) 18-40 0.3% STL, AKERBP +$1-$2

Libya 37-43 0.2% (ex two hubs) COP, MRO, FP

Ghana/Ivory Coast 23-39 0.3% TLW +$2-$3

Angola 19-32 0.4% GALP +$2-$3

Nigeria 26-47 0.1% +$2-$3

Brazil (pre-salt Campos) 13-30 0.3%-0.67% GALP +$2-$5

Argentina 24-34 0.3%

Colombia 24-44 0.5% GTN, OXY +$1-$2

Suriname/Guyana Est. 30-40 0.3% HES, XOM +$2-$3

US (WTI) 40 0.2% US Permian E&Ps

Canadian Syncrude Sweet 32 0.1% SU, MEG, CVE +$4-$6

Western Canadian Select 34 0.5% SU, MEG, CVE +$2-$3

Indonesia 20-47 0.1% XOM

Russia (Urals) 31 1.4% BP -$4-$8

Source: Schroders.

Figure 5 on the next page shows global crude markers sulphur content (% of mass) plotted against the weight (API). Three things are

apparent from the chart below:

i. Less than half of international hubs have sulphur content of <0.5% (i.e. can be used without blending to produce IMO compliant

products).

ii. Generally heavier crudes have higher sulphur contents and vice versa.

iii. Distillate (diesel) take is higher with heavier (lower API) crudes, this means medium/heavy, low sulphur hubs will be the winners.

²www.praxair.com/-/media/documents/reports-papers-case-studies-and-presentations/our-company/sustainability/the-role-of-hydrogen-in-removing-sulfur-from-liquid-fuels.pdf?la=en

IMO 2020 – Short-term implications for the oil market 8

Figure 5: Global crude hubs by API and sulphur content

API

50

45 Algeria – Sahara blend

Malaysia – Tapis

40

US - WTI

North Sea - Brent

US - LLS

35 Libya – Es sider

Oman Iran - Light

Nigeria – Bonny Light

Saudi Arabia – Arab Light

FSU - Urals

30 UAE - Dubai Kuwait

Iran - Heavy

US - Mars

Saudi Arabia – Arab Heavy

25

Ecuador - Oriente

Sulphur content (% wt) Mexico - Maya

20

0.0% 0.5% 1.0% 1.5% 2.0% 2.5% 3.0% 3.5%

Source: Schroders; Company reports (BP & Equinor).

The Figure above mirrors what we have heard from company management, namely that the North Sea, areas of South America, West Africa

and North Africa offer the best crude grades for refiners to adapt to IMO 2020. However, there is a wide range of crude markers in the Middle

East and South America with Brazil - Pre Salt and Colombian crude having medium API and low sulphur compared with Venezuela. Likewise

Iranian crude markers tend to be higher sulphur than those of Saudi Arabia. North America also has a wide range in API of crudes, with

Canadian and offshore GoM being typically heavier, and US onshore shales on the lighter end of the spectrum. East Asian crude also screens

well, and tends to be light with low sulphur content (reflected by the Tapis hub). However, given this accounts for a small portion of global

production it will not move the crude markets.

Impact on US onshore shale oil production Figure 6: US crude grades by region

Crude sulphur content varies considerably across the 50 2.0%

US, as shown in Figure 6. However, except for the Mars

45 1.8%

hub, all are light crude (API >40). The recent growth in

North American shale oil production has resulted in US 40 1.6%

refineries already using lighter refining slates compare 35 1.4%

to five years ago. This gives US refiners less scope to

30 1.2%

produce more distillate without taking heavier crudes.

25 1.0%

In contrast European and Asian refineries will need to

increase light and sweet crude intake. This will likely 20 0.8%

increase exports from the US, which have already 15 0.6%

grown substantially over the last three years. 10 0.4%

However, we highlight that similarly to the incremental 5 0.2%

production growth from the Middle East, most of the

0 0.0%

US onshore production is light crude.

Mars LLS WTI Eagle Ford Bakken

Globally refiners will still need more medium and

heavy crude barrels, as production growth of heavier API Sulphur (% wt)

crudes is limited. Source: Schroders; Equinor.

How does this impact the refiners?

Refiners with high distillate and low sulphur fuel oil yields will benefit most from the expected margin growth in these products, driven by

shippers switching fuel intake to comply with the new IMO 2020 regulation. Inversely, those with high gasoline and HSFO yields will be

negatively impacted by lower margins in these products as HSFO demand falls, and gasoline supply (as a by-product) increases with higher

refinery utilisation. Figure 7 on the next page shows the current distillate and fuel oil yields of different refiners. There is a clear divergence in

yields between European and North American refiners, with Europe set up to produce more distillate (averaging 49% of crude throughput),

and the US to produce more gasoline and less distillate (averaging 39% distillate yields). At a company level the stand out beneficiaries are

Repsol, ENI, Galp, Saras and Neste. Asian refineries are also well set up to produce distillate, (average of 48% distillate yields), contrasting with

companies like Gazprom and Petrobras with low distillate yields (33% and 37% respectively).

It should be noted that some refiners (e.g. Galp) have some flexibility over how much HSFO/LSFO they produce, so the yield numbers below

may change to reflect product margins. However distillate yield numbers are unlikely to change meaningfully without a change in each

company’s refining complex.

IMO 2020 – Short-term implications for the oil market 9

Figure 7: Europe and North America distillate and fuel oil yields (as % of crude throughput) by refiner

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

BP ENI TOT RDS REP EQNR GALP OMV SRS NESTE Europe CVX XOM ANDV VLO MPC PSX HFC SU CVE NA Av.

Av.

Distillate yield LSFO HSFO

Source: Wood Mackenzie.

What is the likely time horizon of market reaction?

The crude markets are not yet moving on IMO fears, refiners like to maintain flexibility rather than lock in contracts. Therefore they will

take advantage of short-term price differentials until Feb-June 2019, when refiner slates will start to shift to produce more LSFO.

Refiners are already experimenting with different blends to ensure they can produce IMO 2020 compliant fuel oil.

Marine bunkers need to be drained and washed prior to 1 Jan 2020; therefore refiners will need to be ready and producing by middle

2019.

For the first time ever shippers are contacting refiners about specific fuel requirements. This may shorten the time over which the

regulation may start to impact physical markets.

The general view from refiners is that the market will start reacting in terms of crude differentials/product margins from March-August

2019.

Conclusions and macro impacts:

The main conclusions from this report are:

Crude oil demand will be artificially high in 2020, before reverting back to normalised growth rates in 2021/22.

Low sulphur fuel oil and diesel prices will increase as a result of higher demand from ships.

Refiners supply of distillate is inelastic given crude availability is skewed to light crude; they are already operating near maximum

utilisation rates, and a lack of adaptive capex in recent years.

Sweet medium grade crude prices (e.g. from Brazil pre-salt) are likely to increase in the next two years, which will benefit the price per

barrel realised by producers with the right crude.

Producers supplying the wrong crude (i.e. extra light and sour crude) will be negatively impacted in terms of their realisations.

US shale oil producers should benefit somewhat, as European and Asian refiners demand more of their crude.

Higher diesel (and distillate prices) will negatively impact shipping costs and be inflationary globally.

Given the global nature of the regulation, costs are likely to be largely passed on to the consumer. Fuel costs also make up approximately

70-80% of total transport costs.³

Therefore higher fuel costs will greatly impact total shipping costs, and have knock on effects for globally traded goods.

Estimates for the cost vary (Wood Mackenzie suggests a 50% increase, EnSys estimate between 11-23%⁴).

Perishable goods (like agricultural produce) will negatively impact more than other commodities, as shippers can moderate the speed to

economise on fuel use in the latter case.

Likewise geographical proximity will become more of a competitive advantage.

³S&P Global Platts

⁴www.ensysenergy.com/downloads/supplemental-marine-fuels-availability-study-2/

IMO 2020 – Short-term implications for the oil market 10

Schroder Investment Management North America Inc.

7 Bryant Park, New York, NY 10018-3706

schroders.com/us

schroders.com/ca

@SchrodersUS

Important Information: The views and opinions contained herein are those of the Schroders Commodities Team, and do not necessarily represent

Schroder Investment Management North America Inc.’s (SIMNA Inc.) house view. Issued August 2018. These views and opinions are subject to change.

Companies/issuers/sectors mentioned are for illustrative purposes only and should not be viewed as a recommendation to buy/sell. This report is intended to be

for information purposes only and it is not intended as promotional material in any respect. The material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the

purchase or sale of any financial instrument. The material is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment

recommendations. Information herein has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable but SIMNA Inc. does not warrant its completeness or accuracy.

No responsibility can be accepted for errors of facts obtained from third parties. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in the document

when making individual investment and / or strategic decisions. The opinions stated in this document include some forecasted views. We believe that we are

basing our expectations and beliefs on reasonable assumptions within the bounds of what we currently know. However, there is no guarantee that any forecasts

or opinions will be realized. No responsibility can be accepted for errors of fact obtained from third parties. While every effort has been made to produce a fair

representation of performance, no representations or warranties are made as to the accuracy of the information or ratings presented, and no responsibility or

liability can be accepted for damage caused by use of or reliance on the information contained within this report. Past performance is no guarantee of future

results.

SIMNA Inc.is registered as an investment adviser with the US Securities and Exchange Commission and as a Portfolio Manager with the securities regulatory

authorities in Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec and Saskatchewan. It provides asset management products and services to

clients in the United States and Canada. Schroder Fund Advisors, LLC (“SFA”) is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Schroder Investment Management North America Inc.

and is registered as a limited purpose broker-dealer with the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority and as an Exempt Market Dealer with the securities

regulatory authorities of Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Newfoundland and Labrador. SFA

markets certain investment vehicles for which SIMNA Inc. is an investment adviser. SIMNA Inc. and SFA are indirect, wholly-owned subsidiaries of Schroders plc, a

UK public company with shares listed on the London Stock Exchange. Further information about Schroders can be found at www.schroders.com/us or

www.schroders.com/ca. Schroder Investment Management North America Inc. (212) 641-3800.

WP-IMO2020-US

IMO 2020 – Short-term implications for the oil market 11

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Sadhak Sanjeevini English BookmarkedДокумент2 166 страницSadhak Sanjeevini English BookmarkedsmaliasОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- (Chapman & Hall - CRC Financial Mathematics Series) Gueant, Olivier-The Financial Mathematics of Market Liquidity - From Optimal Execution To Market Making-CRC Press (2016)Документ302 страницы(Chapman & Hall - CRC Financial Mathematics Series) Gueant, Olivier-The Financial Mathematics of Market Liquidity - From Optimal Execution To Market Making-CRC Press (2016)smalias100% (2)

- Nissan Note E-Power 2022 Quick Guide ENДокумент57 страницNissan Note E-Power 2022 Quick Guide ENSarita EmmanuelОценок пока нет

- OPENING & CLOSING PROGRAM NARRATIVE REPORT (Grade 7)Документ4 страницыOPENING & CLOSING PROGRAM NARRATIVE REPORT (Grade 7)Leo Jun G. Alcala100% (1)

- CSC v1 c9 - Equity Securities - Equity TransactionsДокумент17 страницCSC v1 c9 - Equity Securities - Equity TransactionssmaliasОценок пока нет

- CSC v1 c10 - DerivativesДокумент48 страницCSC v1 c10 - DerivativessmaliasОценок пока нет

- 1617812881step Wise Process For OCI Application NewДокумент10 страниц1617812881step Wise Process For OCI Application NewsmaliasОценок пока нет

- Java Methods For Financial Engineering: Printed BookДокумент1 страницаJava Methods For Financial Engineering: Printed BooksmaliasОценок пока нет

- Devi Shakuntala - Puzzles To Puzzle You-Orient Paperbacks (2005)Документ136 страницDevi Shakuntala - Puzzles To Puzzle You-Orient Paperbacks (2005)smaliasОценок пока нет

- Juhuhuahua's ListДокумент16 страницJuhuhuahua's ListsmaliasОценок пока нет

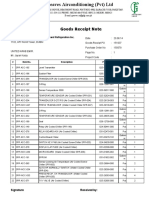

- Goods Receipt Note: Johnson Controls Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Inc. (YORK) DateДокумент4 страницыGoods Receipt Note: Johnson Controls Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Inc. (YORK) DateSaad PathanОценок пока нет

- Moc3040 MotorolaДокумент3 страницыMoc3040 MotorolaBryanTipánОценок пока нет

- Reviewer in PE&H 1st Quarter 18-19Документ7 страницReviewer in PE&H 1st Quarter 18-19rhex minasОценок пока нет

- TransistorДокумент3 страницыTransistorAndres Vejar Cerda0% (1)

- Romano Uts Paragraph Writing (Sorry For The Late)Документ7 страницRomano Uts Paragraph Writing (Sorry For The Late)ទី ទីОценок пока нет

- TinkerPlots Help PDFДокумент104 страницыTinkerPlots Help PDFJames 23fОценок пока нет

- Gates Crimp Data and Dies Manual BandasДокумент138 страницGates Crimp Data and Dies Manual BandasTOQUES00Оценок пока нет

- Namagunga Primary Boarding School: Primary Six Holiday Work 2021 EnglishДокумент10 страницNamagunga Primary Boarding School: Primary Six Holiday Work 2021 EnglishMonydit santinoОценок пока нет

- Causal Emergence - HoelДокумент18 страницCausal Emergence - HoelFelipe LopesОценок пока нет

- 1.2 The Basic Features of Employee's Welfare Measures Are As FollowsДокумент51 страница1.2 The Basic Features of Employee's Welfare Measures Are As FollowsUddipta Bharali100% (1)

- 19 Uco 578Документ20 страниц19 Uco 578roshan jainОценок пока нет

- Modular Heavy Duty Truck TransmissionДокумент6 страницModular Heavy Duty Truck Transmissionphucdc095041Оценок пока нет

- (14062020 0548) HF Uniform Logo GuidelinesДокумент4 страницы(14062020 0548) HF Uniform Logo GuidelinesBhargaviОценок пока нет

- The 5 Pivotal Paragraphs in A PaperДокумент1 страницаThe 5 Pivotal Paragraphs in A PaperFer Rivas NietoОценок пока нет

- SDOF SystemsДокумент87 страницSDOF SystemsAhmet TükenОценок пока нет

- Waste Foundry Sand and Its Leachate CharДокумент10 страницWaste Foundry Sand and Its Leachate CharJanak RaazzОценок пока нет

- Brp-Rotax Chassis Approval FormДокумент3 страницыBrp-Rotax Chassis Approval Formdelta compОценок пока нет

- QSMT Chapter 1Документ5 страницQSMT Chapter 1Rachelle Mae SalvadorОценок пока нет

- Antenna Systems - Standard Format For Digitized Antenna PatternsДокумент32 страницыAntenna Systems - Standard Format For Digitized Antenna PatternsyokomaОценок пока нет

- Human Development and Performance Throughout The Lifespan 2nd Edition Cronin Mandich Test BankДокумент4 страницыHuman Development and Performance Throughout The Lifespan 2nd Edition Cronin Mandich Test Bankanne100% (28)

- Drilling Jigs Italiana FerramentaДокумент34 страницыDrilling Jigs Italiana FerramentaOliver Augusto Fuentes LópezОценок пока нет

- Kowalkowskietal 2023 Digital Service Innovationin B2 BДокумент48 страницKowalkowskietal 2023 Digital Service Innovationin B2 BAdolf DasslerОценок пока нет

- SemДокумент583 страницыSemMaria SantosОценок пока нет

- JCPS School Safety PlanДокумент14 страницJCPS School Safety PlanDebbie HarbsmeierОценок пока нет

- تأثير العناصر الثقافية والبراغماتية الأسلوبية في ترجمة سورة الناس من القرآن الكريم إلى اللغة الإ PDFДокумент36 страницتأثير العناصر الثقافية والبراغماتية الأسلوبية في ترجمة سورة الناس من القرآن الكريم إلى اللغة الإ PDFSofiane DouifiОценок пока нет

- 3DD5036 Horizontal.2Документ6 страниц3DD5036 Horizontal.2routerya50% (2)

- Solar-range-brochure-all-in-one-Gen 2Документ8 страницSolar-range-brochure-all-in-one-Gen 2sibasish patelОценок пока нет

- AMiT Products Solutions 2022 1 En-SmallДокумент60 страницAMiT Products Solutions 2022 1 En-SmallMikhailОценок пока нет