Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Philosophy of The Human Person JEAN-PAUL SARTRE

Загружено:

Kahlil MatthewОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Philosophy of The Human Person JEAN-PAUL SARTRE

Загружено:

Kahlil MatthewАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

JEAN-PAUL SARTRE’s Philosophy of the

Human Person

How does Sartre picture the seeming meaninglessness of worldly existence? In his novel

Nausea, the protagonist Antoine Roquentin experiences the sheer contingency of a tree root

that captures his attention, its gratuituous existence, and his own. It’s like it makes no

difference whether I exist or not in this world because I have no definite role to play. Sartre

writes that every existing thing is born without reason, prolongs itself out of weakness and dies

by chance. The very fact that none of us really knows for sure what exactly the reason is why

we are here, that is for Sartre tantamount to no reason at all. Besides Sartre asserts that human

beings, unlike things, have no essence which determines his reason or purpose of existence.

Simply put, if human beings have no essence, then they have no predetermined purpose or

reason for existence. A paper scissor is made for cuttings papers – that is its essence; it exists

specifically for the purpose of cutting papers. Human beings on the contrary are not made for

something specifically; we do not know exactly what we are here for. No one can really tell even

you yourself.

Sartre differentiates two fundamental modes of being or existence. 1) Being-in-itself, the

being of things and 2) Being-for-itself, the being of human beings. BEING-IN-ITSELF [l’être-en-

soi] refers to the transphenomenal being of the object of consciousness. It is thing-like in

solidity and is self-identical with itself. Things with essences, e.g. trees, animals, stones, the

past, givens of present experience (actuality), facticity which includes reputations,

achievements, social institutions, culture, and history.

BEING-FOR-ITSELF [l’être-pour-soi] is a term he refers to man’s consciousness, the locus

of possibility, negativity, and lack. Consciousness is always a consciousness of something other

than itself. Consciousness is absolutely inscrutable. It can never view itself as consciousness like

a camera lens which cannot view itself. There is that inner distance, internal hollowness, which

separates consciousness from itself, as deep feeling of nothingness. It is through our

consciousness that we experience a sense of incompleteness and lack (nothingness) precisely

because of the capacity for awareness of our possibilities, states of being which we lack or do

not yet exist in us or we have not yet become one with it. If we are not aware that we can be

something which we are not yet now, that we can be better or worse, then we would not also

feel a sense of lack and negativities like absence, distance, regret, desire, longing, aspiration.

Being-for-itself is a transphenomenal dimension of non-being characterized by internal

negation and the nihilation of the in-itself (mere thingly existence). This is the being of man, a

conscious being, who is non-identical-with itself. Although we struggle to become something,

that is, we equate ourselves with things like being a doctor, teacher, citizen, manager, or being

good, responsible, sociable, etc. but deep inside we are also aware that we are not merely

doctors or teachers, we are more than them. We are neither really good, nor responsible, etc.,

we are less than these characters. We can never fully equate ourselves with them. We are

nothing compared to them and we know we can never fully identify ourselves with them but

we desire to be identified with them, to be like them. Once at some point we may be able to

identify ourselves with them, we refuse ourselves to be absolutely identified with them. We

have this inner feeling that we are more or less than these things we have identified ourselves

with. Like a student who struggled to be a nurse. When she became a nurse, she was so happy

© K!W!™ 24 January 2012. Last edited on 6 June 2020. Sartre 1 | P a g e

until one day a doctor remarked to her: “You’re nothing but just a nurse. Just follow everything

I’m telling you.” I’m sure that nurse would protest, even if only internally, that she not just as

she appears to the doctor; that she is more than just a nurse. She refuses to be identified merely

as a nurse because she personally and inwardly knows and feels she is MORE THAN just that.

Sartre points out three major characteristics of human reality. 1) ecstatic temporality, 2)

freedom, and 3) paradox. First, human beings stands out [Greek ek=out, stasis=stand] from

others and from its very self within the three ecstasis of time. Man has a past that determined

his present and partly determines his future called by Sartre as facticity. Man has a future which

to the largest extent his existence is determined; this Sartre calls as project. Man has a present;

he is constantly present-to things and others which also constantly influence his existence. This

is termed by Sartre as actuality. Second, human being is free because he is not a self, that is,

predetermined self-essence, but a presence-to-self. He is a consciousness who is conscious of

itself as consciousness, as nothingness, as undetermined self which awaits determination by

one’s own self. Human being is free because he is a self-determining and self-negating

consciousness, not even a self-determined self.

Third, it is precisely this freedom that makes human existence as a paradox, the non-

self-coincidence of human reality. The human self and what it wants of itself will never

absolutely coincide. Every consciousness desires to be self-identical, a being-for-itself trying to

be a being-in-itself which is an ontological impossibility. They are two different and

irreconcilable existences. We can never be anything we wanted to be because we can always

desire to transcend that thingness. It’s so ironic because we know we can never really be that

thing we want yet can’t help desiring to be that thing. This is the reason why Sartre declares

that HUMAN EXISTENCE IS A FUTILE PASSION. Human reality is what it is not (its possibilities)

and is not what it is (its facticity and actuality). I am what I will be and choose to become. I am

not my previous choices, and the labels people, history and culture have affixed on me because I

can change my stance to them. I am free to deny the situation its existence and change it. I can

always make something different out of what I’ve been made into by my past and present

situations and choices. This is the burden of our responsibility and the source of our hope. To

be human is to be conscious, to be free to imagine, to be free to choose and be responsible for

one’s lot in life. This is even very true to the lot of the third man in the Jesus’ Parable of the

Talents who was just given two talents. We are defined less by what is gratuitously given to us

but we are defined more by what we have chosen to do with what is given to us – that is our

inevitable burden of responsibility. WE ARE WHAT WE MAKE OF OURSELVES.

Although Sartre recognizes that there is a third mode of existence which he calls being-

for-others, he does not consider it fundamental but only derivative of the two fundamental

modes of consciousness. BEING-FOR-OTHERS [l’être-pour-autrui] is the intersubjective

/interpersonal dimension where consciousness meets another consciousness. This existence

cannot be deduced but encountered. One proof used by Sartre to characterize this dimension is

the experience of SHAME. The example used by Sartre is a man peeping in the keyhole and is

caught by someone else. In here, one experiences the vulnerability of one’s embodiedness to

the look/gaze of the other. This is an experience of BEING OBJECTIFIED by the gaze of another

subject. This experience of being objectified and the feeling of shame are simultaneously an

experience of another as subject/consciousness.

LOOK/GAZE is considered by Sartre as a basic form of interpersonal relation. Living with

the other is like a game of mutual staredown – each trying to objectify the other. If a person

© K!W!™ 24 January 2012. Last edited on 6 June 2020. Sartre 2 | P a g e

judges so rashly another, objectifying him to be like this or that kind of thing, the other would

remark that the former is judgmental not being aware that the latter himself who passes the

judgment to the former of being so judgmental is also judgmental. The latter who protests to an

attempt at objectifying him by the judgments of the former unknowingly also objectifies the

former by his remark. When you are conscious that a lot of people are staring or looking at you

and you are not used to it, you feel uncomfortable and petrified which does not happen when

you are not conscious of the look or stare.

For Sartre, the presence of others is a constant threat to subjectivity. This is the reason

why Sartre made a very famous remark “HELL IS OTHER PEOPLE.” When one catches us doing

something humiliating, we find ourselves defining ourselves in terms of how others think of us

(but also resisting that definition). We also tend to catch others in the judgments we make of

ourselves and define one another in terms of each other’s definition of himself. But then

judgments are essential and inevitable ingredients in the sense of ourselves. We can never get

rid of making judgments of each other; all we can do is minimize and make them just, prudent,

and appropriate. It’s so nauseating to always define ourselves and live our lives based on the

expectations of others. Sometimes we need to leave people alone to give them space and break

from our gaze/look so that they can experience the freedom of being themselves inasmuch as

we also desire the same thing to ourselves and from others. Sometimes HEAVEN IS I ALONE BY

MYSELF.

Guide Questions for Study and Discussions

1. Why does Jean-Paul Sartre think that there is a seeming meaninglessness to worldly

existence?

2. What does Sartre mean by human being as a being-for itself?

3. Why is human existence a useless passion? Do you agree with Sartre? Why?

4. Can you agree with Sartre’s characterization of the interpersonal dimension of human

existence? Why?

5. Are we absolutely “what we make of ourselves”? Discuss in Sartre’s perspective.

6. Is there a grain of truth to Sartre’s claim that “Hell is other people”? Why? Cite an

example.

Guide Questions for Study and Discussions

1. contingent existence

2. being-in-itself

3. being-for-itself

4. being-for-others

5. look/gaze

© K!W!™ 24 January 2012. Last edited on 6 June 2020. Sartre 3 | P a g e

Вам также может понравиться

- Self Development: IntroductionДокумент40 страницSelf Development: IntroductionMark Antony LevineОценок пока нет

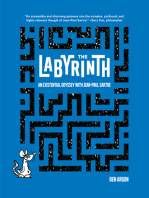

- The Labyrinth: An Existential Odyssey with Jean-Paul SartreОт EverandThe Labyrinth: An Existential Odyssey with Jean-Paul SartreРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (8)

- An Existentialist Ethics PDFДокумент5 страницAn Existentialist Ethics PDFPaula BautistaОценок пока нет

- Force and Motion Inquiry UnitДокумент6 страницForce and Motion Inquiry Unitapi-289263562100% (2)

- Reflection ExistentialismДокумент2 страницыReflection Existentialismcorrianjunjun100% (1)

- Blessed MadnessДокумент51 страницаBlessed MadnessvictoriafannОценок пока нет

- Campbell M., Bruus M. - Glossika. Swedish Fluency 1 PDFДокумент368 страницCampbell M., Bruus M. - Glossika. Swedish Fluency 1 PDFAnonymous IC3j0ZS100% (2)

- The Notion of Freedom in Krishnamurti and SartreДокумент10 страницThe Notion of Freedom in Krishnamurti and SartreMaheshUrsekarОценок пока нет

- Age of Existentialism and Phenmenology TextДокумент4 страницыAge of Existentialism and Phenmenology TextLee JessОценок пока нет

- Sartre, Transcendence of The Ego, 1Документ3 страницыSartre, Transcendence of The Ego, 1joseph_greenber4885100% (1)

- Sartre's Existentialism ExplainedДокумент12 страницSartre's Existentialism Explainedandreacirla100% (3)

- Existentialism and Humanism by Jean-Paul Sartre (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideОт EverandExistentialism and Humanism by Jean-Paul Sartre (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideОценок пока нет

- Notes in Existentialism in HumanismДокумент5 страницNotes in Existentialism in HumanismcorrianjunjunОценок пока нет

- R D Laing The Politics of ExperienceДокумент23 страницыR D Laing The Politics of Experiencel33l00Оценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan CeltaДокумент5 страницLesson Plan CeltaAdela Marian100% (2)

- The Effects of Sleep Deprivation To The Interpersonal Interactions of The Grade 9-10 Students of Liceo de CabuyaoДокумент78 страницThe Effects of Sleep Deprivation To The Interpersonal Interactions of The Grade 9-10 Students of Liceo de CabuyaoKC FuentecillaОценок пока нет

- Richard H Jones - Philosophy of Mysticism - Raids On The Ineffable-SUNY Press (2016) PDFДокумент440 страницRichard H Jones - Philosophy of Mysticism - Raids On The Ineffable-SUNY Press (2016) PDFANDERSON SANTOSОценок пока нет

- A PHENOMENOLOGY of LOVE (Booklet Form)Документ10 страницA PHENOMENOLOGY of LOVE (Booklet Form)Kahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- Sartre's Concept of Freedom and Existential ResponsibilityДокумент5 страницSartre's Concept of Freedom and Existential Responsibilityaury abellana100% (1)

- The Politics of ExperienceДокумент21 страницаThe Politics of ExperienceIslam OsmanОценок пока нет

- Sartre, Existentialism and Human Emotions5Документ2 страницыSartre, Existentialism and Human Emotions5Nitin Kumar0% (1)

- Sartre's View of Freedom as Existential BeingДокумент8 страницSartre's View of Freedom as Existential BeingMiguel Alejandro Híjar-ChiapaОценок пока нет

- Sartres Concept of Bad Faith and the Paradox of DeceptionДокумент4 страницыSartres Concept of Bad Faith and the Paradox of Deceptionbroomer142Оценок пока нет

- Sartres Theory of Sexuality 1979Документ11 страницSartres Theory of Sexuality 1979Antonios NaderОценок пока нет

- Inauthentically Self-Deception RessentimentДокумент5 страницInauthentically Self-Deception RessentimentLu XieОценок пока нет

- Jean-Paul Sartre On Bad Faith in Search of Authenticity, Individuality, and Self-RealizationДокумент6 страницJean-Paul Sartre On Bad Faith in Search of Authenticity, Individuality, and Self-RealizationButch CabayloОценок пока нет

- Sartre's Existential Philosophy of 'Existence Precedes EssenceДокумент3 страницыSartre's Existential Philosophy of 'Existence Precedes EssenceSarthak AroraОценок пока нет

- Sartre's Philosophical Project Key Questions: 1) What Are The Major Themes of Existentialism?Документ4 страницыSartre's Philosophical Project Key Questions: 1) What Are The Major Themes of Existentialism?Саша СамусеваОценок пока нет

- SartreДокумент2 страницыSartrevitormeirinhoОценок пока нет

- 79375-Article Text-186301-1-10-20120723Документ5 страниц79375-Article Text-186301-1-10-20120723陈与奇Оценок пока нет

- Human ConditionДокумент3 страницыHuman ConditionXhanynne CocoyОценок пока нет

- 1554548551SRC 6 1 122-129Документ8 страниц1554548551SRC 6 1 122-129NATASHA GULZARОценок пока нет

- Explain Sartre's Distinct+Документ4 страницыExplain Sartre's Distinct+Levi KachinkāОценок пока нет

- Module 9Документ8 страницModule 9Guin leeОценок пока нет

- Hell and Other PeopleДокумент13 страницHell and Other PeopleLiziОценок пока нет

- I Am Going To Talk About Care and My Thesis To Conceptualize The OtherДокумент139 страницI Am Going To Talk About Care and My Thesis To Conceptualize The Otherkhushi.rajputОценок пока нет

- Human Experience Philosophy1Документ7 страницHuman Experience Philosophy1ماجد ورديОценок пока нет

- Jean-Paul Sartre P Grosse Process and Themes FALL 2002Документ2 страницыJean-Paul Sartre P Grosse Process and Themes FALL 2002Cris Carry-on100% (1)

- Sartre's Existence Precedes EssenceДокумент1 страницаSartre's Existence Precedes EssenceNicolas GutierrezОценок пока нет

- ph313 - DiscussionДокумент3 страницыph313 - DiscussionzeerowОценок пока нет

- Marcel's View of Authentic Freedom as Being Beyond HavingДокумент9 страницMarcel's View of Authentic Freedom as Being Beyond HavingJoshua Conlu MoisesОценок пока нет

- Humanism in Sartre's Philosophy: Banashree BhardwajДокумент3 страницыHumanism in Sartre's Philosophy: Banashree BhardwajinventionjournalsОценок пока нет

- Existentialism Jean Paul SarteДокумент2 страницыExistentialism Jean Paul SarteMillicent MarcoОценок пока нет

- We Are Our Possibilities From Sartre ToДокумент18 страницWe Are Our Possibilities From Sartre ToLuis Filipe MacielОценок пока нет

- Academy of St. Joseph: The Human ConditionДокумент2 страницыAcademy of St. Joseph: The Human ConditionMaverick Jann EstebanОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Philosophy Presentation: Please Focus On The Following Aspects of Being and NothingnessДокумент6 страницContemporary Philosophy Presentation: Please Focus On The Following Aspects of Being and Nothingnessmichael jhon amisolaОценок пока нет

- SartreДокумент1 страницаSartreAngelica Marie M. EncilaОценок пока нет

- Spirit of RevengeДокумент15 страницSpirit of Revengeanti ramirezОценок пока нет

- Philosophy, Ma'am MuycoДокумент9 страницPhilosophy, Ma'am MuycoJose Erwin BorbonОценок пока нет

- Sartre's Account of the Look in Being and NothingnessДокумент20 страницSartre's Account of the Look in Being and NothingnessCarlosPerezОценок пока нет

- Jean Paul SartreДокумент3 страницыJean Paul SartreKristelОценок пока нет

- The Case of Julia A Sartrean Existential PDFДокумент7 страницThe Case of Julia A Sartrean Existential PDFFaten SalahОценок пока нет

- NAS 2011 Proceedings McMahonДокумент8 страницNAS 2011 Proceedings McMahonInayatul ChusnaОценок пока нет

- 04 The Transcendence of The EgoДокумент2 страницы04 The Transcendence of The EgoMatt IskraОценок пока нет

- Existentialism (MR I)Документ43 страницыExistentialism (MR I)witzdabitzОценок пока нет

- Sartres and ExistentialismДокумент12 страницSartres and Existentialismraschid1Оценок пока нет

- HUMAN EXISTENCE AND "TRANSCENDENCE" in The Philosophy of Karl JaspersДокумент8 страницHUMAN EXISTENCE AND "TRANSCENDENCE" in The Philosophy of Karl Jaspersjoelsagut100% (3)

- Being and Nothingness The Look SartreДокумент3 страницыBeing and Nothingness The Look Sartremaximomore50% (4)

- Exist Sartre No ExitДокумент5 страницExist Sartre No ExitKhadidjaОценок пока нет

- Abdul Aziz - No Exit - DramaДокумент5 страницAbdul Aziz - No Exit - Dramaabdul azizОценок пока нет

- Module 6 - Human FreedomДокумент4 страницыModule 6 - Human FreedomEnzo MendozaОценок пока нет

- PhilosophyДокумент11 страницPhilosophyKelly Cedeles PalomarОценок пока нет

- Sartre's Existential Phenomenology OutlineДокумент3 страницыSartre's Existential Phenomenology OutlineVANCHRISTIAN TORRALBAОценок пока нет

- You Noticed That?: Who you were, what you were, and all the things you’ve caused... Have you ever noticed that?От EverandYou Noticed That?: Who you were, what you were, and all the things you’ve caused... Have you ever noticed that?Оценок пока нет

- 04 Argument 1 Arindam CHAKRABARTIДокумент13 страниц04 Argument 1 Arindam CHAKRABARTIdemczogОценок пока нет

- The Look: Solipsism Phenomenological Proof" Ontological ProofДокумент2 страницыThe Look: Solipsism Phenomenological Proof" Ontological ProofVinayak PaliwalОценок пока нет

- ResponsibilityДокумент4 страницыResponsibilityMoises Macaranas JrОценок пока нет

- WORKBOOK 01 Supplement p.307b (Unit IV Mediate Inference Lesson 3)Документ1 страницаWORKBOOK 01 Supplement p.307b (Unit IV Mediate Inference Lesson 3)Kahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- WORKBOOK 01 Supplement p.307b (Unit IV Mediate Inference Lesson 3)Документ1 страницаWORKBOOK 01 Supplement p.307b (Unit IV Mediate Inference Lesson 3)Kahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- WORKBOOK 01 Supplement p.307b (Unit IV Mediate Inference Lesson 3)Документ1 страницаWORKBOOK 01 Supplement p.307b (Unit IV Mediate Inference Lesson 3)Kahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- WORKBOOK 01 Supplement p.307b (Unit IV Mediate Inference Lesson 3)Документ1 страницаWORKBOOK 01 Supplement p.307b (Unit IV Mediate Inference Lesson 3)Kahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- WORKBOOK 01 Supplement p.300b (Unit II Propositions Lesson 3)Документ1 страницаWORKBOOK 01 Supplement p.300b (Unit II Propositions Lesson 3)Kahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- RIZAL - CHAP 02 - Historical Background of Jose Rizal - For PRINTINGДокумент13 страницRIZAL - CHAP 02 - Historical Background of Jose Rizal - For PRINTINGKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- RIZAL - CHAP 03 - Development of Filipino National Consciousness - FOR PRINTING 01Документ3 страницыRIZAL - CHAP 03 - Development of Filipino National Consciousness - FOR PRINTING 01Kahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- RIZAL - CHAP 02 - Historical Background of Jose Rizal - For PRINTING PDFДокумент13 страницRIZAL - CHAP 02 - Historical Background of Jose Rizal - For PRINTING PDFKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- RIZAL - CHAP 01 - Significance of The Rizal Course - 201 - For HandoutsДокумент7 страницRIZAL - CHAP 01 - Significance of The Rizal Course - 201 - For HandoutsKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- WORKBOOK 01 Supplement p.307b (Unit IV Mediate Inference Lesson 3)Документ1 страницаWORKBOOK 01 Supplement p.307b (Unit IV Mediate Inference Lesson 3)Kahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- RIZAL - CHAP 01 - Significance of The Rizal Course PDFДокумент9 страницRIZAL - CHAP 01 - Significance of The Rizal Course PDFKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- RIZAL - CHAP 03 - Development of Filipino National ConsciousnessДокумент3 страницыRIZAL - CHAP 03 - Development of Filipino National ConsciousnessKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- (INTERNET) Søren KierkegaardДокумент79 страниц(INTERNET) Søren KierkegaardKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- (INTERNET) Karl JaspersДокумент24 страницы(INTERNET) Karl JaspersKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- (INTERNET) Martin HeideggerДокумент52 страницы(INTERNET) Martin HeideggerKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- (INTERNET) Martin HeideggerДокумент52 страницы(INTERNET) Martin HeideggerKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- Philosophy of The Human Person ALBERT CAMUSДокумент3 страницыPhilosophy of The Human Person ALBERT CAMUSKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- (INTERNET) Jean-Paul SartreДокумент47 страниц(INTERNET) Jean-Paul SartreKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- ADVANCED PHILO 5 Marxists' TerminologyДокумент1 страницаADVANCED PHILO 5 Marxists' TerminologyKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- (INTERNET) Friedrich NietzscheДокумент90 страниц(INTERNET) Friedrich NietzscheKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- (INTERNET) Gabriel MarcelДокумент40 страниц(INTERNET) Gabriel MarcelKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- Philosophy of The Human Person JEAN-PAUL SARTREДокумент3 страницыPhilosophy of The Human Person JEAN-PAUL SARTREKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- (INTERNET) Albert CamusДокумент41 страница(INTERNET) Albert CamusKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- (INTERNET) Albert CamusДокумент41 страница(INTERNET) Albert CamusKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- Philosophy of The Human Person ALBERT CAMUSДокумент3 страницыPhilosophy of The Human Person ALBERT CAMUSKahlil MatthewОценок пока нет

- Compar Ative Ad Jec Tives: Slow Slower Heavy Heavier Dangerous More DangerousДокумент1 страницаCompar Ative Ad Jec Tives: Slow Slower Heavy Heavier Dangerous More DangerousJudith Rodriguez LopezОценок пока нет

- Infinitive Vs GerundДокумент4 страницыInfinitive Vs GerundShamsiddin EgamberganovОценок пока нет

- School Transition and School Readiness: An Outcome of Early Childhood DevelopmentДокумент7 страницSchool Transition and School Readiness: An Outcome of Early Childhood DevelopmentAlex Ortega AlbornozОценок пока нет

- Human Resource Management: Recruitment and Selecting Employees (STAFFING)Документ26 страницHuman Resource Management: Recruitment and Selecting Employees (STAFFING)Thùy TrangОценок пока нет

- Here Is A Possible Sample of Science and Technology Writing About An EarthquakeДокумент2 страницыHere Is A Possible Sample of Science and Technology Writing About An EarthquakeAnalyn Ewican JalipaОценок пока нет

- WEEKLY ENGLISH LESSON SUMMARYДокумент6 страницWEEKLY ENGLISH LESSON SUMMARYstar sawalОценок пока нет

- Chapter 13 Personality PsychologyДокумент46 страницChapter 13 Personality Psychologyapi-291179388100% (1)

- Maximizing Technology - BogorДокумент77 страницMaximizing Technology - BogorKurnia WanОценок пока нет

- Mpu 3233Документ22 страницыMpu 3233herueuxОценок пока нет

- Aby Ocaoi PHED 10022 Reflective Essay 1 PDFДокумент1 страницаAby Ocaoi PHED 10022 Reflective Essay 1 PDFCrizlen FloresОценок пока нет

- Milestones Studyguide gr04 3-20-2017Документ128 страницMilestones Studyguide gr04 3-20-2017api-3255368190% (1)

- Transitive and Intransitive Verbs Linking Verbs Auxiliary Verbs The Finite Verb and The Infinitive Action Verb/State Verb Regular and Irregular VerbsДокумент7 страницTransitive and Intransitive Verbs Linking Verbs Auxiliary Verbs The Finite Verb and The Infinitive Action Verb/State Verb Regular and Irregular VerbsArun SomanОценок пока нет

- Work Place Spirituality ScaleДокумент1 страницаWork Place Spirituality ScaleGowtham RaajОценок пока нет

- Module 2 RG Classroom Environment 530Документ3 страницыModule 2 RG Classroom Environment 530api-508727340Оценок пока нет

- Annotating & OutliningДокумент15 страницAnnotating & OutliningJenni ArdiferraОценок пока нет

- Traffic Flow Optimization using Reinforcement LearningДокумент2 страницыTraffic Flow Optimization using Reinforcement LearningJohn GreenОценок пока нет

- GED102 Week 2 WGNДокумент5 страницGED102 Week 2 WGNHungry Versatile GamerОценок пока нет

- Done - Portfolio Activity Unit-2 OBДокумент4 страницыDone - Portfolio Activity Unit-2 OBDjahan RanaОценок пока нет

- A Descriptive Study To Assess The Level of Stress and Coping Strategies Adopted by 1st Year B.SC (N) StudentsДокумент6 страницA Descriptive Study To Assess The Level of Stress and Coping Strategies Adopted by 1st Year B.SC (N) StudentsAnonymous izrFWiQОценок пока нет

- Rubrik Penilaian SpeakingДокумент2 страницыRubrik Penilaian SpeakingBertho MollyОценок пока нет

- Module Johntha (Autosaved)Документ7 страницModule Johntha (Autosaved)Tadyooss BalagulanОценок пока нет

- PMPG 5000 W17 Principles Proj MGMTДокумент10 страницPMPG 5000 W17 Principles Proj MGMTTanzim RupomОценок пока нет

- Ent MGT Lect 1 - IntroductionДокумент25 страницEnt MGT Lect 1 - Introductioncome2pratikОценок пока нет

- Influence of Technology On PoliticsДокумент4 страницыInfluence of Technology On Politicschurchil owinoОценок пока нет